Abstract

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) has been implicated in neurodegeneration and in central nervous system (CNS)-mediated host defence responses to inflammation. All actions of IL-1 identified to date appear to be mediated through its only known functional type I receptor (IL-1RI). However, our recent evidence suggests that some actions of IL-1 in the brain may be IL-1RI independent, suggesting the involvement of a new, hitherto unknown functional receptor for IL-1.

The objective of the present study was to determine if primary mixed glial cells express additional functional IL-1 receptors by studying the signalling mechanisms responsible for the pro-inflammatory actions of IL-1β in cultures derived from IL-1RI−/− and wildtype mice, and to characterize the functional importance of IL-1 signalling pathways in glia.

IL-1β induced marked release of IL-6 and prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) in the culture medium, and activated nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) and the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK1/2) in cells from wildtype mice. These responses were dependent on IL-1RI, since cells isolated from IL-1R1−/− mice did not demonstrate any of these responses.

In wildtype mice, inhibition of p38 or ERK1/2 MAPKs significantly reduced IL-1β induced IL-6 release, whilst the NFκB inhibitor caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) modulated IL-1 induced IL-6 release by action on NFκB and MAPKs pathways.

These data demonstrate that IL-1RI is essential for IL-1β signalling in cultured mixed glial cells. Thus IL-1 actions observed in IL-1RI−/− mice in vivo may occur via an alternative pathway and/or via different CNS cells.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, IL-1 receptors, IL-1 signalling, glial cells, MAP kinase, NFκB, IL-6, CAPE

Introduction

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine which plays an important role in neuroinflammation and host defence responses to peripheral disease and injury (Rothwell & Luheshi, 2000), and also acts as a mediator of neurodegeneration (Allan & Rothwell, 2001; Rothwell, 1998; Rothwell & Luheshi, 2000). The IL-1 family includes the two agonists, IL-1α and IL-1β, which are believed to share identical biological functions although IL-1β is the main form released from cells. A third member of the IL-1 family is the naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), which acts by inhibiting the actions of IL-1α and β on its receptor (Dinarello, 1996). In peripheral cells, IL-1α and β exert their actions by binding to an 80 kDa cell surface receptor (IL-1RI), which requires association with an accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) for signal transduction (Wesche et al., 1997). A second, 68 kDa receptor (IL-1RII) for IL-1 has a short intracellular domain and does not initiate signal transduction (Sims et al., 1993), acting instead as a soluble protein. IL-1 triggers distinct cellular signalling pathways, the most well characterized of which leads to activation of the transcription factor NFκB. IL-1 also activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades involving p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the classical MAPK extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK1/2), also known as p42/44 MAPK (reviewed in O'neill & Greene, 1998).

Glial cells are major contributors to the brain's inflammatory response (Mcgeer & Mcgeer, 1995; Perry et al., 1995). In particular astrocytes respond to IL-1β by triggering the NFκB and MAPK signalling pathways (Molina-Holgado et al., 2000; Moynagh et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 1996), resulting in the release of other inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2).

Although these mechanisms of IL-1 actions are well established in brain cells, some significant questions have recently been raised about the presence of additional functional IL-1 receptor(s) in the CNS. Previous studies showed that intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of IL-1 dramatically exacerbates ischaemic brain damage whilst i.c.v. injection of IL-1ra significantly reduces ischaemic injury (Loddick & Rothwell, 1998; Relton & Rothwell, 1992). Deletion of IL-1α and β in mice reduces ischaemic brain damage by about 80% (Boutin et al., 2001). In contrast mice lacking IL-1RI exhibit similar brain damage to their wildtype counterparts and i.c.v. injection of IL-1 exacerbates ischaemic brain damage to the same extent in wildtype and IL-1RI−/− mice (Touzani et al., 2002), suggesting that IL-1 can modify ischaemic brain damage independently of IL-1RI. This is an intriguing result since all previous work using IL-1RI−/− mice have shown that these animals fail to exhibit a normal inflammatory and host defence response to IL-1 (Glaccum et al., 1997; Labow et al., 1997). The recent discovery of new members of the IL-1 receptor family points to the existence of alternative IL-1 pathways. These receptors include T1/ST2, IL-1Rrp2, TIGIRR-1, and the IL-1 receptor accessory protein-like (IL1RAPL) molecule (reviewed in Bowie & O'neill, 2000). However none of these receptors have been shown to bind IL-1.

The objectives of the present study were to characterize the signalling mechanisms responsible for the pro-inflammatory actions of IL-1β during brain ischaemia in IL-1RI−/− mice and to determine if any of the primary immune target cells in the brain, glial cells, can respond to IL-1β by initiating signal transduction cascades or the release of inflammatory mediators in the absence of IL-1RI. To do this we compared the release of IL-6 and PGE2 and the activation of NFκB and the MAPKs (p38, JNK and ERK1/2) in response to IL-1β, in wildtype and IL-1RI−/− primary mixed glial cells. We subsequently characterized the role of the different signalling cascades in the release of IL-6 from wildtype cells using specific MAPKs and NFκB inhibitors.

Methods

Materials

Drugs used were: caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE; Sigma U.K.), SB202190 (Calbiochem, U.K.), UO126 (Promega, U.K.).

Mixed glial culture preparation

Primary mixed glial cultures were prepared (Weibel et al., 1984) from the brains of 0–2-day-old IL-1RI deficient (IL-1R1−/−) mice (Immunex, Seattle, U.S.A.) and their wildtype counterparts (C57BL6 X 129sv, Charles River, Kent, U.K.). Briefly, cells from whole brains were dissociated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; GibcoBRL, U.K.), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (GibcoBRL, U.K.), 100 IU ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (GibcoBRL, U.K.). Cells were seeded at 5×105 cells ml−1 onto poly-D-lysine (Sigma, U.K.) coated 12-well plates. The medium was changed after 5 days in vitro (DIV) and then every 3 days until confluency (12–13 DIV).

To confirm gene deletion, PCR was performed on tail genomic DNA from wildtype and IL-1RI knockout mice using the following three primers: IL-1RI specific 5′GAGTTACCCGAGGTCCAG and 5′GAAGAAGCTCACGTTGTC and Neo specific 5′GCGAATGGGCTGACCGCT. The wildtype IL-1RI product is 1150 bp and the mutant IL-1RI product 860 bp (data not shown).

Mixed glial cell treatment

To investigate IL-6 and PGE2 release, cells from wildtype and IL-1R1−/− mice were stimulated for 24 h with vehicle (saline/0.1% BSA), IL-1β (0.05, 0.1, 1, 10 or 100 ng ml−1), IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1), LPS (0.1, 1, 10 μg ml−1) or co-treatment with IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1). IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) was also denatured by heat treatment (95°C for 30 min) to confirm the response was not due to contaminants. To investigate activation of NFκB and the MAPKs, cells were stimulated for 5, 15, 30 or 60 min with vehicle, IL-1β (10 ng ml−1), IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1), LPS (1 μg ml−1) or co-treatment with IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1). Inhibitors were used to determine the role of MAPKs in IL-1β induced IL-6 release. Cells were pre-treated with the ERK1/2 inhibitor UO126 (10 μM), the p38 inhibitor SB202190 (10 μM) or vehicle for 40 min at 37°C and then stimulated with vehicle or IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) for 24 h. To determine the role of NFκB in IL-6 release, cells were pre-treated for 2 h with CAPE (5 mg ml−1 in 50% ethanol; Sigma, U.K.), diluted from a range of 2–100 μg ml−1 in culture medium) or vehicle at 37°C, then stimulated with vehicle or IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) for 30 min or 24 h.

IL-6 detection by ELISA

Release of IL-6 into the culture medium was assayed as described previously (Rees et al., 1999), using a mouse specific sandwich ELISA, generously provided by Dr Steve Poole of the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC, U.K.). IL-6 standards were assayed in triplicate and samples (100 μl) in duplicate. The assay was specific for IL-6 with no cross-reactivity with other cytokines. The sensitivity of this assay was 9 pg ml−1 and internal quality controls were included in each assay.

PGE2 detection by RIA

Release of PGE2 into the culture medium was measured by a mouse specific radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Haworth & Carey, 1986). Briefly, PGE2 standards were assayed in triplicate and samples in duplicate (100 μl) with a 1 : 10,000 dilution of anti-PGE2 antibody (Sigma, U.K.). Dextran-coated charcoal was used to separate bound radiolabelled PGE2 (0.005 μCi per tube [3H]-PGE2, specific activity 200 Ci mmol−1, Pharmacia Amersham Biotech, U.K.) to the supernatant. The RIA was sensitive to 50 pg ml−1.

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA)

To prepare the nuclear extract, 2×106 cells were resuspended in buffer (mM): DTT 0.5, HEPES (pH 7.9) 10, KCl 10, MgCl2 1.5, PMSF 0.5 and centrifuged at 60,000×g for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in the same buffer containing 0.1% Nonidet P40 (NP40) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The homogenate was centrifuged (60,000×g for 10 min) and the nuclear pellet resuspended in nuclear extraction buffer (mM): EDTA 0.2, NaCl 420, HEPES (pH 7.9) 20, MgCl2 1.5, glycerol 25%, PMSF 0.5. After centrifugation, nuclear extracts were resuspended in (mM): EDTA 0.2, DTT 0.5, HEPES (pH 7.9) 20, KCl 50, glycerol 20%, PMSF 0.5 and stored at −70°C. The protein content was measured by BioRad protein assay (BioRad Laboratories, U.K.).

EMSAs were performed by incubating 4 μg of nuclear extract with 35 fmol of 32P-end-labelled 21-mer double-stranded NFκB oligonucleotide (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGG-3′) (Promega, U.S.A.) in binding buffer (mM): EDTA 0.2, DTT 0.5, NaCl 30, HEPES (pH 7.9) 10, KCl 70, MgCl2 5, Tris (pH 7.9) 3, glycerol 10% containing 1 μg poly(dI·dC) (Roche, U.K.) and 75 μg BSA (Promega, U.S.A.) for 30 min at room temperature. The complex formed was separated from the excess of labelled probe on a 4% native polyacrylamide gel. The gel was then dried and exposed to Hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, U.K.) overnight at −70°C.

MAPK detection by Western blot analysis

Whole cells were washed twice with isotonic solution then lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.1% NP40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM sodium-orthovanadate) for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentration in the cell lysates was determined by the Bradford method (BioRad Laboratories, U.K.) and equal amounts of protein (15 μg) resolved by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, U.K.). Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the membranes for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (5% fat-free dry milk in PBS/0.1% Tween-20). The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer with antibodies which recognise all forms or the activated forms of the MAPKs: anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (1 : 5000; New England BioLabs, U.S.A.), anti-phospho-JNK (1 : 5000; Promega, U.K.), anti-phospho-p38 (1 : 1000; Promega, U.K.), anti-total ERK1/2 (1 : 60,000; Santa Cruz, U.S.A.), anti-total JNK (1 : 30,000; Santa Cruz, U.S.A.) and anti-total p38 (1 : 1000; New England BioLabs, U.S.A.). The antibody-antigen complexes were detected using a horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1 : 2000; Santa Cruz, U.S.A.) diluted in blocking buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody was subsequently detected by enhanced chemilluminescense (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, U.K.). Films were analysed densitometrically using Molecular Analyst™ (version 1.5) (BioRad Laboratories, U.K.).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean±s.e.mean of at least three independent experiments on separate cultures, which were analysed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Immunocytochemical characterization of the mixed glial cultures, using specific markers for different cell types (GFAP, GSA, A2B5), revealed a similar percentage of astrocytes (78%), microglia (10%) and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (12%) in cultures from wildtype and IL-1RI−/− mice (data not shown). Thus, any differences between wildtype and IL-1RI−/− cells were not due to differences in cellular composition of the cultures.

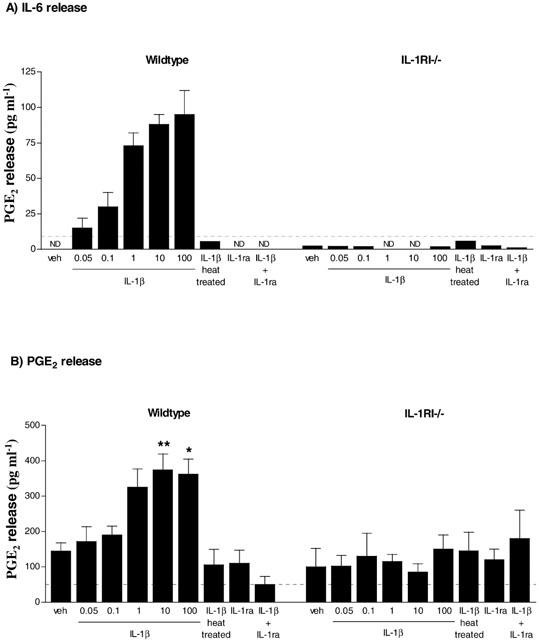

IL-1β induced release of the inflammatory mediators IL-6 and PGE2 in primary mixed glial cultures is IL-1RI mediated

IL-6 was undetectable in the media of vehicle treated cells, but increased in response to exposure to IL-1β (0.05–100 ng ml−1) when compared to vehicle (Figure 1A). PGE2 was detectable in vehicle treated cultures, and was increased (2.5 fold) by exposure to 10 ng ml−1 (P<0.01) or 100 ng ml−1 (P<0.05) IL-1β (Figure 1B). The IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) induced release of IL-6 and PGE2 was completely abolished by co-incubation with IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1) or heat-treating (denaturing) the IL-1β, confirming the specificity of the response (Figure 1A,B). No IL-6 or PGE2 release was detected in cultures of glia from IL-1RI−/− mice in response to vehicle or IL-1β (Figure 1A,B), although LPS dose-dependently increased both inflammatory mediators (Table 1).

Figure 1.

IL-1β induced IL-6 and PGE2 release from primary mixed glial cells from wildtype or IL-1RI−/− mice. Cell supernatants were removed 24 h after treatment with IL-1β (0.05–100 ng ml−1) and/or IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1) and assayed for (A) IL-6 release using ELISA or (B) PGE2 release using RIA. Data are expressed as pg ml−1 and are the mean±s.e.mean of three independent experiments carried out in duplicate. ND indicates that the concentration was below the detection limit (dotted line) of the assay. Statistical analysis could therefore not be carried out for IL-6, as there was no detectable release after treatment with vehicle. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs vehicle for PGE2 release.

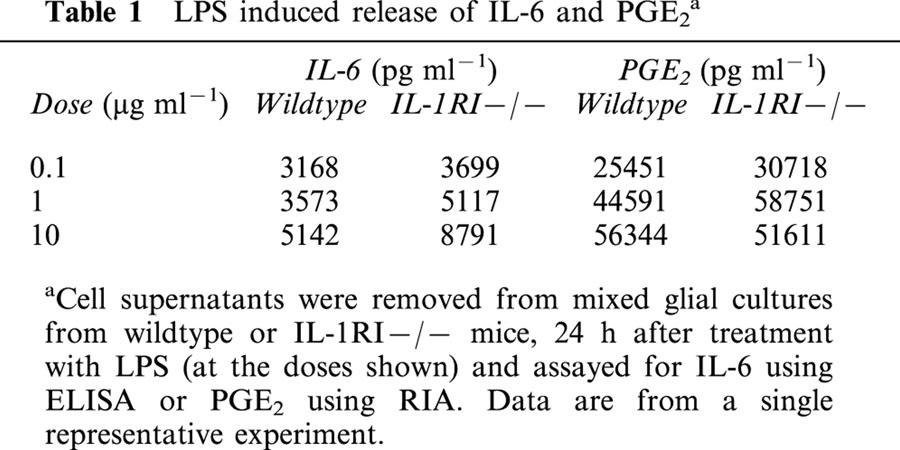

Table 1.

LPS induced release of IL-6 and PGE2a

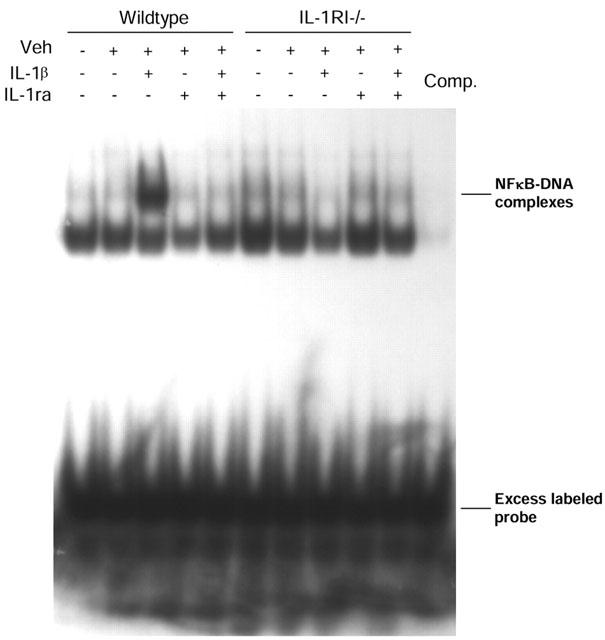

IL-1β induced activation of signal transduction pathways in primary mixed glial cultures are dependent on IL-1RI

The concentration of IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) that stimulated IL-6 and PGE2 release from wildtype cultures was used to investigate IL-1β signal transduction pathways. IL-1β induced NFκB activity was detectable in nuclear extracts by 30 min (Figure 2). The DNA-protein interaction was inhibited by addition of excess unlabelled probe (containing the NFκB binding site) to nuclear extracts before incubation with the labelled probe. NFκB activation by IL-1β was also prevented by co-incubation of cells with IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1), while IL-1ra alone had no effect. IL-1β failed to activate NFκB in nuclear extracts obtained from IL-1RI−/− cells, confirming that IL-1RI is required for IL-1β induced NFκB activation.

Figure 2.

IL-1β induced NFκB activation in primary mixed glial cells from wildtype or IL-1RI−/− mice. Primary mixed glial cell cultures from wildtype or IL-1RI−/− mice were incubated with vehicle (saline/BSA), and in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and/or IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1) for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared and analysed for NFκB activity. Excess free unlabelled probe (Comp) containing the NFκB binding site inhibited the DNA complexes. Results are representative of three independent experiments on separate cultures.

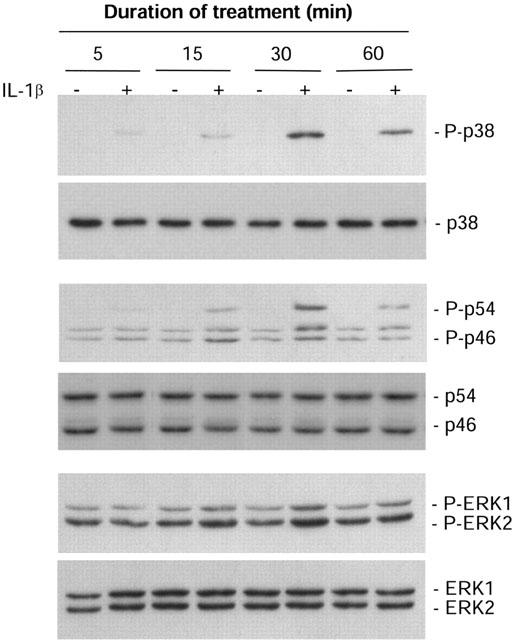

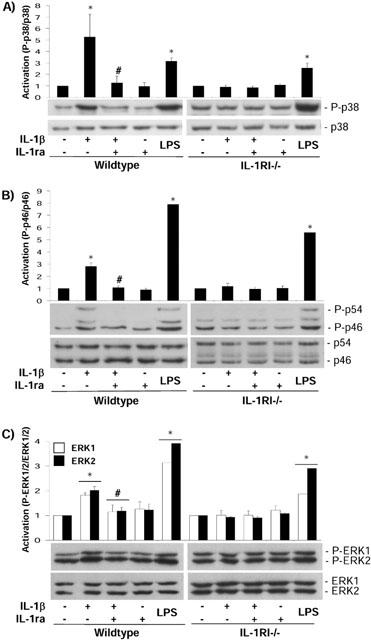

MAPK phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot analysis. A time-course study showed increased activation of p38, JNK and ERK1/2 in wildtype cells treated with IL-1β from 5 to 30 min in a time-dependent manner, whilst at 60 min activation of the MAPKs decreased (Figure 3). Therefore 30 min is the point where maximal activation of the three MAPKs was obtained. IL-1β induced maximal (5 fold) p38 activation in wildtype cells, which was inhibited (94%) by co-incubation with IL-1ra, whilst IL-1ra alone had no effect (Figure 4A). In IL-1RI−/− cells, IL-1β had no effect on p38 activity although p38 phosphorylation was observed in response to LPS (1 μg ml−1) (Figure 4A). The predominant phosphorylated isoform of JNK expressed in mixed glial cultures is p46. In wildtype cells, maximal (3 fold) p46 JNK activity induced by IL-1β was inhibited (96%) by co-incubation with IL-1ra, while IL-1ra alone had no effect (Figure 4B). The phosphorylated p54 isoform of JNK was not detected in vehicle-treated wildtype cells, but strong activation was detected in response to IL-1β, which was completely inhibited by co-incubation with IL-1ra. IL-1β had no effect on p46/p54 JNK activity in IL-1RI−/− cells, although activation was again observed in response to treatment with LPS (Figure 4B). In wildtype cells, IL-1β elicited a 2 fold increase in ERK1/2 activity, which was inhibited (85%) by co-incubation with IL-1ra; IL-1ra alone had no effect (Figure 4C). In IL-1RI−/− cells, IL-1β had no effect on ERK1/2, although activation was observed in response to treatment with LPS (Figure 4C). These results confirmed that in response to IL-1β the activation of NFκB and the three MAPKs, p38, JNK and ERK1/2, was dependent on IL-1RI.

Figure 3.

Time course activation of MAPK in primary mixed glial cells from wildtype mice. Mixed glial cultures from wildtype mice were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) for 5, 15, 30 or 60 min. Whole cell lysates were analysed by immunoblot using antibodies specific for the total and phosphorylated forms of p38, JNK or ERK1/2. The Western blots shown are representative of three independent experiments on separate cultures.

Figure 4.

MAPK activation in primary mixed glial cells from wildtype or IL-1RI−/− mice. Mixed glial cultures from wildtype and IL-1RI−/− mice were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and/or IL-1ra (1 μg ml−1) for 30 min. LPS (1 μg ml−1) was used as a positive control. Whole cell lysates were analysed by immunoblot using antibodies specific for the total and phosphorylated forms of p38 (A), JNK (B) or ERK1/2 (C). Quantification of three independent experiments is presented as mean activation±s.e.mean as compared to the control. *P<0.05 vs vehicle; #P<0.05 vs IL-1β.

Inhibition of the MAPK signalling pathway reduces, whilst the NFκB inhibitor CAPE dose-dependently modulates IL-6 release from wildtype mixed glial cultures by action on both NFκB and MAPK pathways

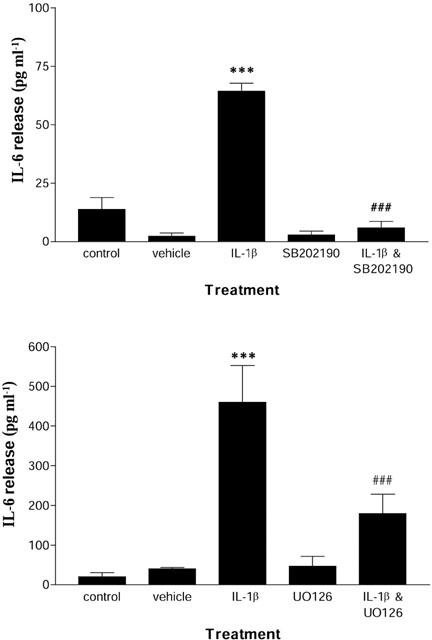

Pre-treatment of glia with the p38 inhibitor SB202190 significantly reduced (91%; P<0.001) IL-1β induced IL-6 release from wildtype primary mixed glial cells, while SB202190 alone had no effect (Figure 5). Pre-treatment with the ERK1/2 inhibitor UO126 also significantly reduced (61%; P<0.05) IL-1β induced IL-6 release from wildtype primary mixed glia, but had no effect in the absence of IL-1β (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of the p38 inhibitor SB202190 and the ERK1/2 inhibitor UO126 on IL-1β induced IL-6 release. Cell supernatants from wildtype mixed glial cultures were removed 24 h after treatment with vehicle (saline/BSA), IL-1β (10 ng ml−1), SB202190 (10 μM), UO126 (10 μM), IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and SB202190 (10 μM), IL-1β (10 ng/ml) and UO126 (10 μM), and assayed for IL-6 by ELISA. Data are the mean±s.e.mean of three independent experiments on separate cultures carried out in duplicate. ***P<0.05 vs naïve or vehicle; ###P<0.05 vs IL-1β.

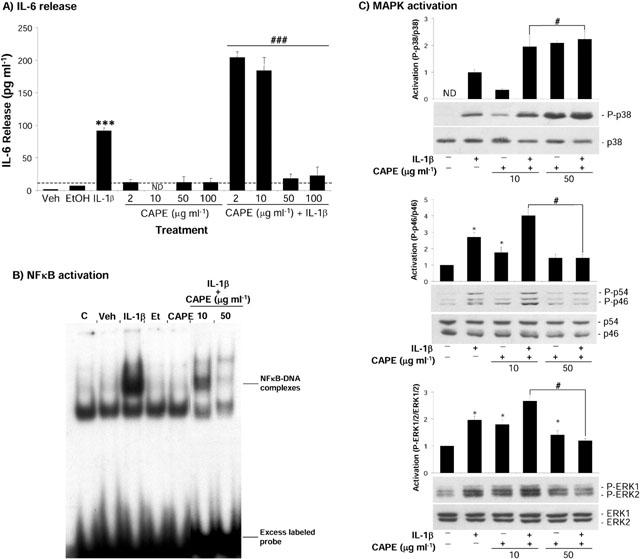

Co-incubation of IL-1β with the NFκB inhibitor CAPE, used at 2 and 10 μg ml−1, significantly enhanced (2.2 and 2 fold respectively; P<0.05) the release of IL-6 from wildtype mixed glial cells (Figure 6A), whilst higher concentrations (50 and 100 μg ml−1) significantly reduced (76 and 66% respectively; P<0.05) IL-1β induced IL-6 release. CAPE alone did not induce significant release of IL-6 at any of the doses tested. CAPE inhibited NFκB activity when used at a dose of 50 μg ml−1 (Figure 6B). The effect of CAPE on IL-1β-induced MAPK phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 6C). CAPE alone (10 and 50 μg ml−1) activated ERK1/2 (1.8 and 1.4 fold respectively) and JNK (1.7 and 1.4 fold respectively). CAPE induced weak activation of p38 at 10 μg ml−1 but strong activation at 50 μg ml−1. Co-incubation of cells with IL-1β and CAPE (10 μg ml−1) significantly enhanced IL-1β induced ERK1/2 (1.4 fold), p38 (1.9 fold) and JNK (1.5 fold) activation (Figure 6C). However 50 μg ml−1 CAPE significantly reduced IL-1β induced activation of ERK1/2 (73%; P<0.05) and JNK (75%; P<0.05) but enhanced IL-1β induced p38 activation (2.2 fold).

Figure 6.

Effect of the NFκB inhibitor CAPE on IL-1β induced IL-6 release, NFκB and MAPK activation. Wildtype mixed glial cells were either untreated, or incubated with vehicle (saline/BSA), IL-1β (10 ng ml−1), ethanol, CAPE (2–100 μg ml−1), or IL-1β (10 ng ml−1) and CAPE (2–100 μg ml−1). For (A) cell supernatants were removed after 24 h and assayed for IL-6 by ELISA. Data are the mean±s.e.mean of four independent experiments carried out in duplicate. ***P<0.05 vs naïve or vehicle; ###P<0.05 vs IL-1β. ND indicates that the concentration was below the detection limit (dotted line) of the assay. For (B) nuclear extracts were prepared and NFκB activity analysed. Results are representative of three independent experiments on separate cultures. For (C) whole cell lysates were analysed by immunoblot using antibodies specific for the total and phosphorylated forms of p38, JNK or ERK1/2. Quantification of three independent experiments is presented as mean activation mean±s.e.mean as compared to the control. *P<0.05 vs vehicle; #P<0.05 vs IL-1β.

Discussion

Mixed glial cultures were chosen for this study in order to examine IL-1RI-independent responses to IL-1 of all glial cell types present in the brain and therefore to determine if any of these cells express additional functional IL-1 receptors. Mixed glial cultures also mimic the situation in vivo more closely than cultures of individual glia, since responses to cytokines such as IL-1 may depend on interactions between microglia and astrocytes. Furthermore, their preparation requires less manipulation than individual glial cultures, reducing inadvertent priming of the cells or activation of stress responses that involve many of the same pathways as IL-1β, and may therefore influence the results.

The synthesis and release of IL-6 and PGE2 by glial cells are important in the CNS inflammatory response to infection and injury. In the present study, IL-1β dose-dependently induced the release of IL-6 and PGE2 from wildtype mouse glial cells, but failed to induce release in glial cells from mice lacking IL-1RI. These cells did however release IL-6 and PGE2 in response to LPS. The transcription factor NFκB is a pivotal regulator of the inflammatory response in the brain (O'neill & Kaltschmidt, 1997), while the MAPKs are a family of serine/threonine kinases which also activate the transcription of inflammatory genes (for reviews see Herlaar & Brown, 1999; Tibbles & Woodgett, 1999). The results show that in wildtype mixed glial cultures, NFκB and the MAPKs, p38, JNK and ERK1/2, are activated within 30 min of IL-1β treatment. IL-1R1 is essential for the activation of these signalling pathways in primary glial cells, since IL-1β failed to activate NFκB and MAPKs in IL-1RI−/− cells, although LPS was capable of activating these pathways.

Similar activation of MAPKs and NFκB and subsequent release of IL-6 and PGE2 in response to IL-1β has been described previously in astrocytes (Aloisi et al., 1992; Molina-Holgado et al., 2000; Moynagh et al., 1993; van wagoner et al., 1999, Zhang et al., 1996), but not microglial cells (Bauer et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1993; Minghetti & Levi, 1995). In addition the contribution of oligo dendro cytes progenitor cells in responses triggered by IL-1β in mixed glia is unclear. This suggests that the responses to IL-1β observed in wildtype mixed glial cultures were mainly via activation of astrocytes, but does not rule out the possibility that the responses were influenced indirectly by microglia.

IL-1β failed to induce release of IL-6 and PGE2 or activate MAPKs and NFκB in glial cells from mice lacking IL-1RI, although these cells did release IL-6 and PGE2 and activate MAPKs and NFκB in response to LPS. This confirmed that loss of IL-1RI was responsible for resistance to IL-1β, rather than a defect in the pathways themselves, since LPS activates an identical intracellular signalling cascade to IL-1RI, via Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4; Bowie & O'neill, 2000). These results suggest that activation of MAPKs and NFκB and the release of IL-6 and PGE2 in glial cells are not involved in IL-1 actions that occur in the ischaemic brain of IL-1RI−/− mice (Touzani et al., 2002). However IL-1 may induce other signalling pathways in the brains of these mice via binding of a new receptor, expressed either on glial cells or other brain cells types including neurones or endothelial cells. Alternatively IL-1 actions in IL-1RI−/− mice could occur via induction of expression of a new receptor induced by brain damage.

To characterize the specific contribution of these signal transduction mechanisms in IL-1β induced IL-6 release, the effects of specific inhibitors of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2 MAPK and NFκB activity were studied in glia from wildtype mice. The specific p38 inhibitor SB202190 significantly reduced (91%) IL-1β induced IL-6 release. The ERK1/2 inhibitor UO126, which acts by inhibiting the upstream kinase MKK1 (Favata et al., 1998), also significantly reduced (61%) IL-1β induced IL-6 release. This suggests that activation of p38 and ERK1/2 MAPKs is required for IL-1β induced IL-6 release.

NFκB activation was investigated using the inhibitor CAPE, which prevents the translocation of the p65 subunit of NFκB to the nucleus (Natarajan et al., 1996). Previous work has shown that IL-1β induces IL-6 gene expression in astrocytes via activation of NFκB (Benveniste et al., 1990; Sparacio et al., 1992; van wagoner et al., 1999). In the present study, CAPE inhibited IL-1β induced IL-6 release from primary mixed glial cells at a dose that prevented the translocation of NFκB to the nucleus and the formation of DNA-protein complexes. However, at lower doses, CAPE significantly enhanced IL-1β induced IL-6 release suggesting that CAPE may act on other elements of the signalling pathway involved in the release of IL-6. In an attempt to clarify this hypothesis, the effect of CAPE on activation of p38, JNK and ERK1/2 was analysed. CAPE alone induced activation of these MAPKs with no activation of NFκB, and hence no release of IL-6 from the cells. However, co-incubation of CAPE with IL-1β significantly enhanced activation of the three MAPKs at a dose (10 μg ml−1) where NFκB was not inhibited. These results suggest that low doses of CAPE enhance IL-1β induced activation of MAPKs and hence increase the IL-1β induced IL-6 release pathway without blocking NFκB pathway. In contrast CAPE reduced IL-1β induced IL-6 release at higher doses, which prevented activation of NFκB. At these higher doses, CAPE significantly reduced IL-1β induced ERK1/2 and JNK, but not p38 activation. We therefore conclude that CAPE reduced IL-1β induced IL-6 release by inhibition of ERK1/2 and JNK MAPKs, and NFκB pathways, rather than solely via NFκB as reported previously (Natarajan et al., 1996). The effect of CAPE on MAPKs activities has not been reported previously and its mechanism of action is unclear. Activation of MAPKs by CAPE alone could be the result of a stress response of the cells to the drug. Inhibition of IL-1β induced MAPK activation by CAPE could occur via its recently described antioxidant properties (Chen et al., 2001).

In conclusion, IL-1RI is essential for IL-1β induced release of IL-6 and PGE2 release from primary mixed glial cells and IL-1 induces these responses via activation of NFκB and MAPKs (p38, JNK and ERK1/2). Thus IL-1 actions in IL-1RI deficient mice exposed to cerebral ischaemia in vivo might occur via alternative pathways and/or through a new receptor on glial or other brain cells, which may be induced specifically during brain inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EU TMR grant (No ERBFMRXC1970149), Medical Research Council, U.K. and Syngenta. The IL-1β and IL-1ra were kindly provided by the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC, U.K.). The authors would like to thank Dr Rosemary Gibson for critically reviewing this manuscript and Laura Heenan for technical support.

Abbreviations

- CAPE

caffeic acid phenethyl ester

- CNS

central nervous system

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- IL-1

interleukin-1

- IL-1RI

interleukin-1 type I receptor

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NFκB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- PGE2

prostaglandin-E2

References

- ALLAN S.M., ROTHWELL N.J. Cytokine and acute neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:734–744. doi: 10.1038/35094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALOISI F., CARE A., BORSELLINO G., GALLO P., ROSA S., BASSANI A., CABIBBO A., TESTA U., LEVI G., PESCHLE C. Production of hemolymphopoietic cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, colony- stimulating factors) by normal human astrocytes in response to IL-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2358–2366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUER M.K., LIEB K., SCHULZE-OSTHOFF K., BERGER M., GEBICKE-HAERTER P.J., BAUER J., FIEBICH B.L. Expression and regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in rat microglia. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;243:726–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENVENISTE E.N., SPARACIO S.M., NORRIS J.G., GRENETT H.E., FULLER G.M. Induction and regulation of interleukin-6 gene expression in rat astrocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 1990;30:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90104-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWIE A., O'NEILL L.A.J. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal generators for pro-inflammatory interleukins and microbial products. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000;67:508–514. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUTIN H., LEFEUVRE R.A., HORAI R., ASANO M., IWAKURA Y., ROTHWELL N.J. Role of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in ischaemic brain damage. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5528–5534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05528.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y.J., SHIAO M.S., WANG S.Y. The antioxidant caffeic acid phenethyl ester induces apoptosis associated with selective scavenging of hydrogen peroxide in human leukemic HL-60 cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12:143–149. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINARELLO C.A. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAVATA M.F., HORIUCHI K.Y., MANOS E.J., DAULERIO A.J., STRADLEY D.A., FEESER W.S., VAN DYK D.E., PITTS W.J., EARL R.A., HOBBS F., COPELAND R.A., MAGOLDA R.L., SCHERLE P.A., TRZASKOS J.M. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLACCUM M.B., STOCKING K.L., CHARRIER K., SMITH J.L., WILLIS C.R., MALISZEWSKI C., LIVINGSTON D.J., PESCHON J.J., MORRISSEY P.J. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mice that lack the type I receptor for IL-1. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3364–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAWORTH D., CAREY F. Thromboxane synthase inhibition: implications for prostaglandin endoperoxide metabolism. I. Characterisation of an acute intravenous challenge model to measure prostaglandin endoperoxide metabolism. Prostaglandins. 1986;31:33–45. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(86)90223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERLAAR E., BROWN Z. p38 MAPK signalling cascades in inflammatory disease. Mol. Med. Today. 1999;5:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LABOW M., SHUSTER D., ZETTERSTROM M., NUNES P., TERRY R., CULLINAN E.B., BARTFAI T., SOLORZANO C., MOLDAWER L.L., CHIZZONITE R., MCINTYRE K.W. Absence of IL-1 signaling and reduced inflammatory response in IL-1 type I receptor-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 1997;159:2452–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE S.C., LIU W., DICKSON D.W., BROSNAN C.F., BERMAN J.W. Cytokine production by human fetal microglia and astrocytes. Differential induction by lipopolysaccharide and IL-1 beta. J. Immunol. 1993;150:2659–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LODDICK S.A., ROTHWELL N.J. Neuroprotective effect of human recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998;16:932–940. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGEER P.L., MCGEER E.G. The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1995;21:195–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINGHETTI L., LEVI G. Induction of prostanoid biosynthesis by bacterial lipopolysaccharide and isoproterenol in rat microglial cultures. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2690–2698. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLINA-HOLGADO E., ORTIZ S., MOLINA-HOLGADO F., GUAZA C. Induction of COX-2 and PGE(2) biosynthesis by IL-1beta is mediated by PKC and mitogen-activated protein kinases in murine astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:152–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOYNAGH P.N., WILLIAMS D.C., O'NEILL L.A. Interleukin-1 activates transcription factor NF kappa B in glial cells. Biochem. J. 1993;294:343–347. doi: 10.1042/bj2940343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATARAJAN K., SINGH S., BURKE T.R.., , JR, GRUNBERGER D., AGGARWAL B.B. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester is a potent and specific inhibitor of activation of nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'NEILL L.A., GREENE C. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor family: ancient signaling machinery in mammals, insects, and plants. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;63:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'NEILL L.A., KALTSCHMIDT C. NF-kappa B: a crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends. Neurosci. 1997;20:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERRY V.H., BELL M.D., BROWN H.C., MATYSZAK M.K. Inflammation in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1995;5:636–641. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES G.S., BALL C., WARD H.L., GEE C.K., TARRANT G., MISTRY Y., POOLE S., BRISTOW A.F. Rat interleukin 6: expression in recombinant Escherichia coli, purification and development of a novel ELISA. Cytokine. 1999;11:95–103. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RELTON J.K., ROTHWELL N.J. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist inhibits ischaemic and excitotoxic neuronal damage in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 1992;29:243–246. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90033-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHWELL N.J. Interleukin-1 and neurodegeneration. Neuroscientist. 1998;4:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- ROTHWELL N.J., LUHESHI G.N. Interleukin 1 in the brain: biology, pathology and therapeutic target. Trends. Neurosci. 2000;23:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMS J.E., GAYLE M.A., SLACK J.L., ALDERSON M.R., BIRD T.A., GIRI J.G., COLOTTA F., RE F., MANTOVANI A., SHANEBECK K., GRABSTEIN K.H., DOWER S.K. Interleukin 1 signalling occurs exclusively via the type 1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:6155–6159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPARACIO S.M., ZHANG Y., VILCEK J., BENVENISTE E.N. Cytokine regulation of interleukin-6 gene expression in astrocytes involves activation of an NF-kappa B-like nuclear protein. J. Neuroimmunol. 1992;39:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90257-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIBBLES L.A., WOODGETT J.R. The stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 1999;55:1230–1254. doi: 10.1007/s000180050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOUZANI O., BOUTIN H., LE FEUVRE R.A., PARKER L.C., MILLER A., LUHESHI G.N., ROTHWELL N.J. Interleukin-1 influences ischemic brain damage in the mouse independently of the interleukin-1 type I receptor. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:38–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00038.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN WAGONER N.J., OH J.W., REPOVIC P., BENVENISTE E.N. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) production by astrocytes: autocrine regulation by IL-6 and the soluble IL-6 receptor. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5236–5244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05236.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIBEL M., PETTMANN B., DUANE G., LABOURDETTE G., SENSENBRENNER M. Chemically defined medium for rat astroglial cells in primary cultures. Devl. Neurosci. 1984;2:355–366. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(84)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESCHE H., KORHERR C., KRACHT M., FALK W., RESCH K., MARTIN M.U. The interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) is essential for IL-1-induced activation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) and stress-activated protein kinases (SAP kinases) J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7727–7731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG P., MILLER B.S., ROSENZWEIG S.A., BHAT N.R. Activation of C-jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase in primary glial cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;46:114–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961001)46:1<114::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]