Abstract

YC-1, an activator of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), has been shown to increase the intracellular cGMP concentration. This study was designed to investigate the signaling pathway involved in the YC-1-induced COX-2 expression in A549 cells.

YC-1 caused a concentration- and time-dependent increase in COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. Pretreatment of the cells with the sGC inhibitor (ODQ), the protein kinase G (PKG) inhibitor (KT-5823), and the PKC inhibitors (Go 6976 and GF10923X), attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity and COX-2 expression.

Exposure of A549 cells to YC-1 caused an increase in PKC activity; this effect was inhibited by ODQ, KT-5823 or Go 6976. Western blot analyses showed that PKC-α, -ι, -λ, -ζ and -μ isoforms were detected in A549 cells. Treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 or PMA caused a translocation of PKC-α, but not other isoforms, from the cytosol to the membrane fraction. Long-term (24 h) treatment of A549 cells with PMA down-regulated the PKC-α.

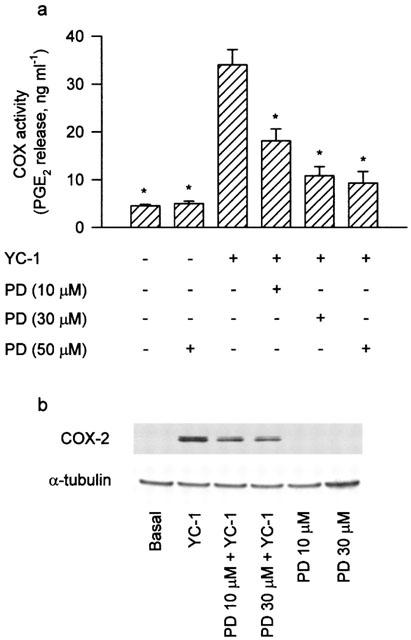

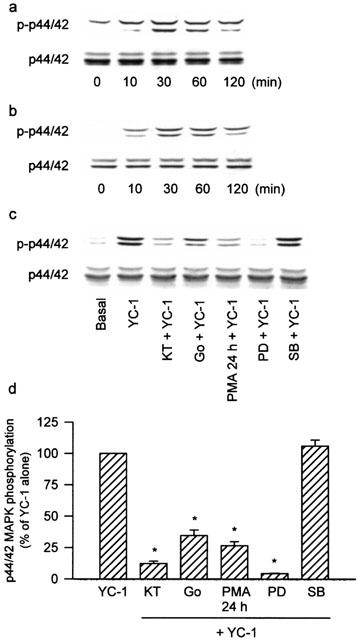

The MEK inhibitor, PD 98059 (10–50 μM), concentration-dependently attenuated the YC-1-induced increases in COX activity and COX-2 expression. Treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 caused an activation of p44/42 MAPK; this effect was inhibited by KT-5823, Go 6976, long-term (24 h) PMA treatment or PD98059, but not the p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB 203580.

These results indicate that in human pulmonary epithelial cells, YC-1 might activate PKG through an upstream sGC/cGMP pathway to elicit PKC-α activation, which in turn, initiates p44/42 MAPK activation, and finally induces COX-2 expression.

Keywords: YC-1, guanylate cyclase, cyclo-oxygenase-2, protein kinase C, p44/42 MAPK, A549 cells

Introduction

Prostaglandins (PGs), lipid mediators derived from membrane phospholipids, are important regulators for smooth muscle contractility, inflammation and platelet functions (Vane et al., 1998). Cyclo-oxygenase (COX) converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2, which is then further metabolized to various PGs, such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostacyclin, and thromboxane A2 (Vane et al., 1998). It is now known that there are at least two distinct COX isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2 (Xie et al., 1991; Mitchell et al., 1995). COX-1 is a housekeeping gene and appears to be responsible for the production of PGs that mediate normal physiological functions, such as maintenance of the integrity of the gastric mucosa and regulation of renal blood flow (Vane, 1994). In contrast, COX-2 is thought to mediate inflammatory events and shows low basal expression, but is rapidly induced by pro-inflammatory stimuli, including cytokines (Maier et al., 1990) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (Mitchell et al., 1993), in cells in vitro and in inflamed sites in vivo (Vane et al., 1994).

Protein kinase C (PKC) represents a family of closely related serine/threonine kinases (Nishizuka, 1992; Hug & Sarre, 1993) that play a key role in different cellular signal transduction pathways (Nishizuka, 1988). Using a molecular cloning technique, it has been shown that PKC consists of at least 12 isoforms expressed in different tissues. These differential tissue distributions have been suggested to be related to specialized cell functions (Nishizuka, 1992; Hug & Sarre, 1993). They have been subdivided into conventional PKC isoforms (α, βI, βII and γ), novel PKC isoforms (δ, ε, η and θ), atypical PKC isoforms (ι, λ and ζ), and yet another subgroup (PKC μ) (Nishikawa et al., 1997). The conventional PKC members can be activated by calcium, phospholipids, diacylglycerol and phorbol ester; the novel PKC members can be activated by the same compounds except calcium. The differential localization and activation properties of the PKC isoforms have led us to study the roles of individual PKC isoforms in the regulation of cellular functions.

Recently, several mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signalling pathways have been demonstrated to play a central role in mediating intracellular signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus. In mammalian cells, at least three different subfamilies of MAPKs have been identified. They include the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs), p44 MAPK (ERK1) and p42 MAPK (ERK2), stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs), also called c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNKs), and the p38 MAPK (Robinson & Cobb, 1997). These kinases are activated by distinct upstream MAPK/ERK kinases (MEKs), which recognize and phosphorylate both threonine and tyrosine residues within a tripeptide motif (Thr-X-Tyr) required for MAPK activation. Once phosphorylated, these MAPKs then phosphorylate and activate downstream targets such as transcriptional factors (Karin, 1994) and regulators of cell function, growth and differentiation (Johnson et al., 1996). Recent reports have demonstrated that p44/42 MAPK are activated by NO-generating compounds in endothelial cells and Jurkat T cells (Lander et al., 1996; Parenti et al., 1998).

Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenous short-lived free radical gas mediator involved in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone, inflammation, cell mediated immunity and coagulation (Nussler & Billiar, 1993). NO exerts its effects on cell functions through a variety of interactions, including binding to haem-containing moieties of enzymes such as soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) (Moncada & Higgs, 1993). The activation of guanylate cyclase and the resultant formation of 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) is responsible for the activity of NO as a relaxant of vascular smooth muscle (Palmer et al., 1987). NO may also be an important mediator in the context of airway inflammation (Gaston et al., 1994). Exhaled NO concentrations in man are significantly increased in diseases such as asthma and bronchiectasis (Barnes & Kharitonov, 1996). Co-induction of the iNOS and COX-2 pathways has been demonstrated in animal and cellular models of inflammation (Vane et al., 1994; Swierkosz et al., 1995). It has been shown that NO increases COX-2 expression and activity in human pulmonary epithelial cell line (A549) and rat mesangial cells through a sGC/cGMP-dependent pathway (Tetsuka et al., 1996; Watkins et al., 1997). However, the intracellular signal transduction pathways involved in the sGC/cGMP-mediated COX-2 expression are still not clear. Recently, the new substance YC-1 (3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole) has been identified as an activator of sGC, and shown to increase the intracellular cGMP concentration in platelets (Ko et al., 1994). The cGMP-increasing effect of YC-1 has been reported to result in inhibition of platelet aggregation (Ko et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1995) as well as to mediate vasorelaxation (Mulsch et al., 1997; Wegener & Nawrath, 1997). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that YC-1 not only stimulated sGC but also inhibited cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase in human platelets (Friebe et al., 1998). In the present study, YC-1 was used to act as an activator of sGC/cGMP pathway and the intracellular signalling pathway by which YC-1-induced COX-2 expression in human pulmonary epithelial cells (A549) was studied.

Methods

Materials

YC-1 (3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole) was provided by Yung-Shin Pharma Ind. Co. (Taichung, Taiwan). Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), actinomycin D, cycloheximide, dithiothreitol (DTT), 4-(2-hydroxy-ethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid (HEPES), ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′, N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), ethylenediaminetetraaectic acid (EDTA), glycerol, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), pepstatin A, leupeptin, sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and Nonident P-40 (NP-40) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Dibutyryl cGMP, 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinozalin-1-one (ODQ), KT-5823, Go 6976, GF10923X and PD98059 were purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F-12, foetal calf serum (FCS), and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.). PGE2 enzyme immunoassay kit was obtained from Cayman Chem. (Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.). PKC [32P] enzyme assay system was purchased from Amersham International plc (Buckinghamshire, U.K.). Antibodies specific for COX-2 and PKC isoforms (α, β, θ, ι, λ ζ and μ) were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, U.S.A.). Antibodies specific for p44/42 MAPK, phospho-p44/42 MAPK, and PKC isoforms (γ, ε and δ) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biochemicals (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). An antibody specific for α-tubulin was purchased from Oncogene Science (Cambridge, U.K.). Anti-mouse IgG conjugated alkaline phosphatase was purchased from Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories (West Grove, PA, U.S.A.). 4-Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP) were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). Protein assay reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, U.S.A.).

Cell culture

A549 cells, a human pulmonary epithelial carcinoma cell line with type II alveolar epithelial cell differentiation, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and grown in DMEM/Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture containing 10% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin (50 U ml−1) in a humidified 37°C incubator. After the cells had grown to confluence, they were disaggregated in Trypsin solution, washed in DMEM/Ham's F-12 supplemented with 10% FCS, centrifuged at 125×g for 5 min, resuspended and then subcultured according to standard protocols.

Measurements of PGE2 release and COX activity

A549 cells were cultured in 12-well culture plates. For experiments designed to measure the release of PGE2 due to endogenous arachidonic acid, the cells were treated with YC-1 (5–50 μM) for 12 h or YC-1 (50 μM) for the indicated time intervals. After treatment, the media were then removed and stored at −80°C until assay. PGE2 was assayed by using the PGE2 enzyme immunoassay kit according to the procedure described by the manufacturer. In the experiments designed to measure the COX activity, the cells were treated with YC-1 (5–50 μM) for 12 h or YC-1 (50 μM) for indicated time intervals, washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and then treated with fresh medium containing arachidonic acid (30 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. The media were then removed for PGE2 enzyme immunoassay. In some experiments, the cells were pretreated with specific inhibitors as indicated followed by YC-1 (50 μM) and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 12 h. After incubation, the cells were washed, and then treated with fresh medium containing arachidonic acid (30 μM) for 30 min at 37°C; the medium was then removed for PGE2 enzyme immunoassay.

Measurement of NO concentration

NO production was assayed by measuring nitrite (a stable degradation product of NO) in culture supernatant using the Griess reagent. Briefly, A549 cells were cultured in 24-well culture plates. After reaching confluence, the culture medium was changed to phenol red-free DMEM/F-12. The cells were treated with YC-1 (50 μM) for 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 or 24 h, and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. After treatment, the supernatant was removed, centrifuged, mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (1% sulphanilamide, 0.1% naphthylene diamine dihydrochloride, 2% phosphoric acid), and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm in a microplate reader. Sodium nitrite (NaNO2) was used for measurement of the standard curve of nitrite concentrations.

Protein preparation and Western blotting

To determine the expression levels of COX-2, α-tubulin, phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated p44/42 MAPK in A549 cells, the total proteins were extracted and Western blot analyses were performed as previously described (Mitchell et al., 1993). Briefly, A549 cells were cultured in 10 cm petri dishes. After reaching confluence, the cells were treated with various concentrations of YC-1 for 12 h (for COX-2 detection) or 10 min (for p44/42MAPK detection), or 50 μM YC-1 for indicated time intervals, and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with specific inhibitors as indicated followed by YC-1 (50 μM) and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4), incubated with extraction buffer (Tris 10 mM, pH 7.0; NaCl 140 mM, PMSF 2 mM, DTT 5 mM, NP-40 0.5%, pepstatin A 0.05 mM and leupeptin 0.2 mM) with gentle shaking, and then centrifuged at 12 500×g for 30 min. The cell extract was then boiled in a ratio of 1 : 1 with sample buffer (Tris 100 mM, pH 6.8; glycerol 20%, SDS 4% and bromophenol blue 0.2%). Electrophoresis was performed using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (2 h, 110 V, 40 mA, 30 μg protein per lane). Separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (2 h, 40 V), treated with 5% fat-free milk powder to block the nonspecific IgGs, and incubated for 2 h with specific antibody for COX-2, α-tubulin, phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK or nonphosphorylated p44/42 MAPK. The blot was then incubated with anti-mouse or -rabbit IgG linked to alkaline phosphatase (1 : 1000) for 2 h. Subsequently, the membrane was developed with NBT/BCIP as a substrate. The quantitative data were obtained by using a computing densitometer with Image-Pro plus software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., MD, U.S.A.).

Analyses of PKC activity and PKC isoform translocation

For the detection of PKC activity and PKC isoform translocation, cytosolic and membrane fractions were separated as described previously (Li et al., 1998). Briefly, A549 cells were incubated with vehicle, YC-1 (50 μM), or PMA (1 μM) for indicated time intervals, or pretreated with specific inhibitors as indicated followed by YC-1, and then incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were scraped, collected, homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer (Tris 20 mM, EDTA 2 mM, EGTA 5 mM, glycerol 20% (v v−1), PMSF 2 mM, aprotinin 1% (v v−1), DTT 5 mM) for 20 min, sonicated for 10 s and then centrifuged at 800×g for 10 min. The supernatant (cytosolic and membrane fraction) was removed and centrifuged at 25 000×g for 15 min to obtain the cytosolic fraction (supernatant). The pellets (membrane fraction) were solubilized in homogenization buffer containing 0.1% NP-40. The PKC activity was assayed using the PKC enzyme assay system (Amersham International plc) according to the procedure described by the manufacturer. In studies of PKC isoform translocation, the protein levels of PKC isoforms in cytosolic and membrane fractions were determined by Western blotting analysis performed as previously described (Li et al., 1998).

Statistical analysis

Results shown are means±s.e.mean from duplicate determinations (wells) of 3–4 separate experiments. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by, when appropriate, Bonferroni multiple range test was used to determine the statistical significance in the difference between means. A P-value of less than 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

YC-1 induces COX-2 expression in A549 cells

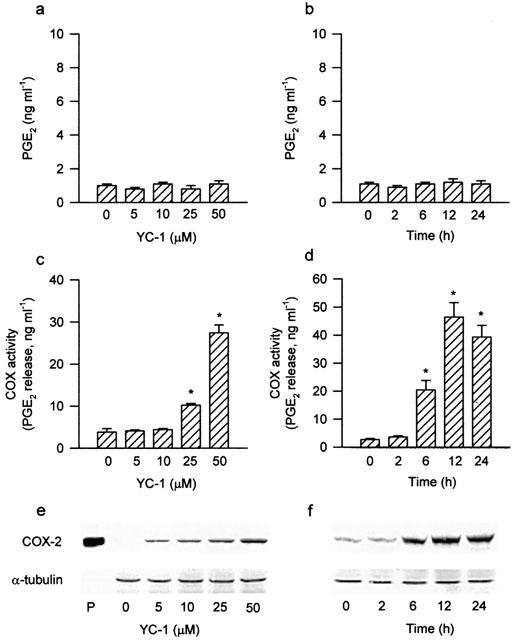

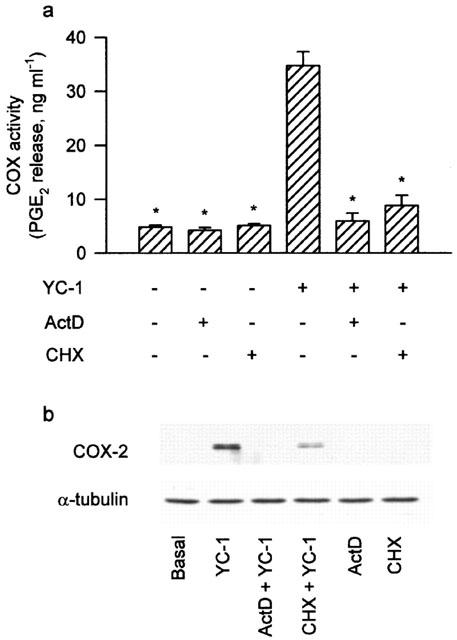

In the absence of exogenous arachidonic acid, treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 at a range of concentrations (5–50 μM) for 12 h or 50 μM YC-1 for various time intervals did not cause any change in the release of PGE2 (Figure 1a,b). However, the COX activity (measured as described in the Method section) was concentration-dependently elevated at 12 h after addition of YC-1 (5–50 μM) (Figure 1c). Treatment of YC-1 (5–50 μM; for 12 h) also induced expression of a 70 kDa COX-2 protein in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1e). Exposure of the cells to YC-1 (50 μM) resulted in a time-dependent increase in COX activity (Figure 1d) and expression of COX-2 protein, with a maximal effect at 12 h (Figure 1f). In the following experiments, the cells were treated with 50 μM YC-1 for 12 h. Pretreatment of the cells with actinomycin D (0.1 μM) or cycloheximide (3 μM) for 30 min markedly attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity by 97.3 or 88.9%, respectively. The YC-1-induced COX-2 expression was also attenuated (Figure 2). The basal level of nitrite release from A549 cells was 1.2±0.2 μM (n=4). Treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 (50 μM) for up to 24 h did not cause any significant change in nitrite production (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effects of YC-1 on PGE2 release, COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. Treatment of the cells with various concentrations of YC-1 for 12 h (a) or YC-1 (50 μM) for the indicated time intervals (b) did not change the PGE2 release. YC-1 induced a concentration-dependent increase in COX activity (c) and COX-2 expression (e), and a time-dependent increase in COX activity (d) and COX-2 expression (f). The COX activity was measured by examining the PGE2 formation in the presence of 30 μM exogenous arachidonic acid for 30 min. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with the basal level. In (e) and (f), cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of YC-1 for 12 h (e) or YC-1 (50 μM) for various time intervals (f), and the extracted proteins were then immunodetected with COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of α-tubulin. Whole cell lysate of mouse macrophages (RAW 264.7) stimulated by LPS (1 μg ml−1) and INFγ (10 ng ml−1) for 12 h was used as a positive control (P).

Figure 2.

Effects of actinomycin D and cycloheximide on the YC-1-induced increase of COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. In (a), the cells were pretreated with 0.1 μM ActD or 3 μM CHX for 30 min followed by a 12 h YC-1 (50 μM) incubation. The media were then removed, and the COX activity was measured by examining the PGE2 formation in the presence of 30 μM exogenous arachidonic acid for 30 min. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with treatment with YC-1 alone. In (b), the cells were pretreated with 0.1 μM ActD or 3 μM CHX for 30 min before incubation with YC-1 (50 μM) for 12 h. Immunodetection with COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody was performed as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of α-tubulin. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. ActD, actinomycin D; CHX, cycloheximide.

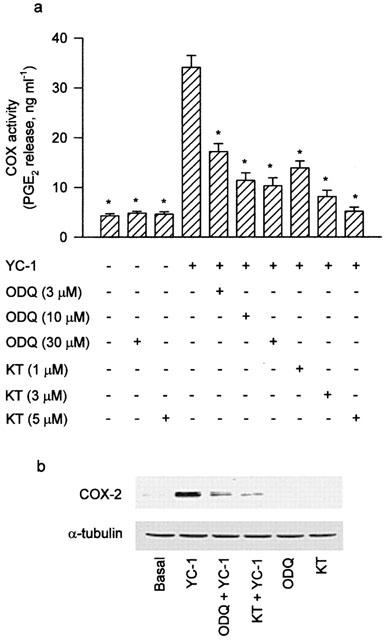

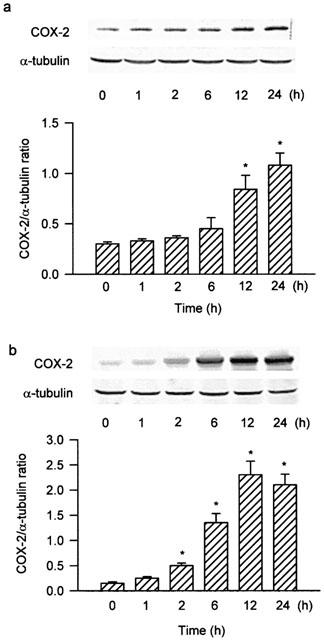

To determine whether sGC/cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG) pathways were involved in the signal transduction pathway leading to COX-2 expression caused by YC-1, the cells were treated with the sGC inhibitor (ODQ) and the PKG inhibitor (KT-5823) followed by YC-1 treatment. Pretreatment of the cells with ODQ (3–30 μM) or KT-5823 (1–5 μM) for 30 min concentration-dependently attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity (Figure 3a). The YC-1-induced COX-2 expression was markedly inhibited by 30 μM of ODQ, and almost completely inhibited by 5 μM of KT-5823 (Figure 3b). Furthermore, treatment of the cells with dibutyryl cGMP (0.3 μM), a cell permeable cGMP analogue, caused a time-dependent increase in COX-2 expression, with a marked induction of COX-2 protein at 12 h after treatment (Figure 4a).

Figure 3.

Involvement of sGC/cGMP pathway in the YC-1-induced increase of COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. In (a), the cells were pretreated with various concentrations of ODQ (sGC inhibitor) or KT (PKG inhibitor) for 30 min followed by a 12 h YC-1 (50 μM) incubation. The media were then removed, and the COX activity was measured by examining the PGE2 formation in the presence of 30 μM exogenous arachidonic acid for 30 min. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with treatment with YC-1 alone. In (b), the cells were pretreated with 30 μM ODQ or 5 μM KT for 30 min before incubation with YC-1 (50 μM) for 12 h. Immunodetection with COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody was performed as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of α-tubulin. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. KT, KT-5823.

Figure 4.

Dibutyryl cGMP and PMA induce a time-dependent increase in COX-2 expression in A549 cells. The cells were incubated with 0.3 μM dibutyryl cGMP (a) or 10 nM PMA (b) for various time intervals, and the extracted proteins were then immunodetected with COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody as described in Methods. The extents of COX-2 and α-tubulin protein expression were quantitated using a densitometer with Image-Pro plus software. The relative level was calculated as the ratio of COX-2 to α-tubulin protein level. Results were expressed as mean±s.e.mean (n=3). *P<0.05 as compared with the basal level.

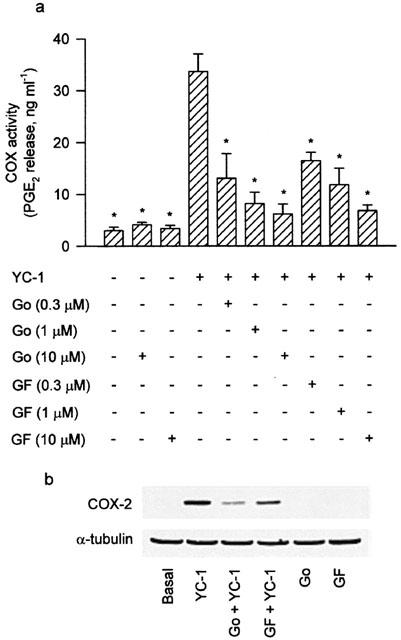

The role of PKC isoforms on the YC-1-induced COX-2 expression

To determine whether PKC activation was involved in the signal transduction pathway leading to COX-2 expression caused by YC-1, the PKC inhibitors, Go 6976 and GF10923X, were used. Pretreatment of the cells for 30 min with Go 6976 (0.3–10 μM) or GF10923X (0.3–10 μM) significantly attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5a). The YC-1-induced COX-2 expression was also inhibited by Go 6976 (1 μM) or GF10923X (10 μM) (Figure 5b). On the other hand, stimulation of the cells with the PKC activator, PMA (10 nM), caused an increase in COX-2 expression in a time-dependent manner, with a significant induction of COX-2 protein occurring at 2 h and peaking at 12 h (Figure 4b).

Figure 5.

Involvement of PKC in the YC-1-induced increase of COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. In (a), the cells were pretreated with various concentrations of PKC inhibitor (Go or GF) for 30 min followed by a 12 h YC-1 (50 μM) incubation. The media were then removed, and the COX activity was measured by examining the PGE2 formation in the presence of 30 μM exogenous arachidonic acid for 30 min. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with treatment with YC-1 alone. In (b), the cells were pretreated with 1 μM Go or 10 μM GF for 30 min before incubation with YC-1 (50 μM) for 12 h. Immunodetection with COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody was performed as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of α-tubulin. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. Go, Go 6976; GF, GF10923X.

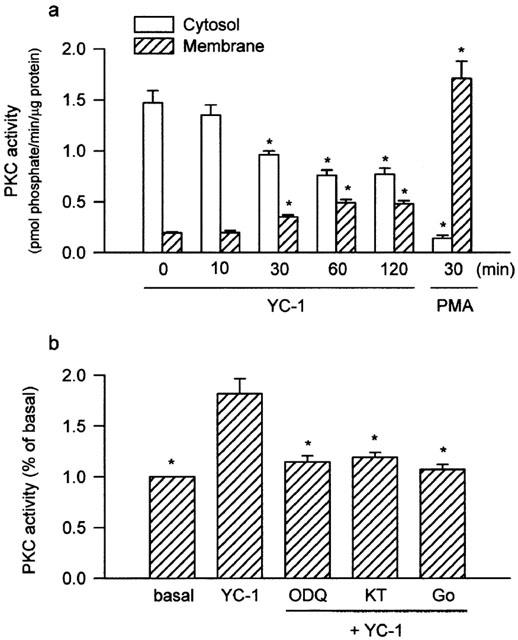

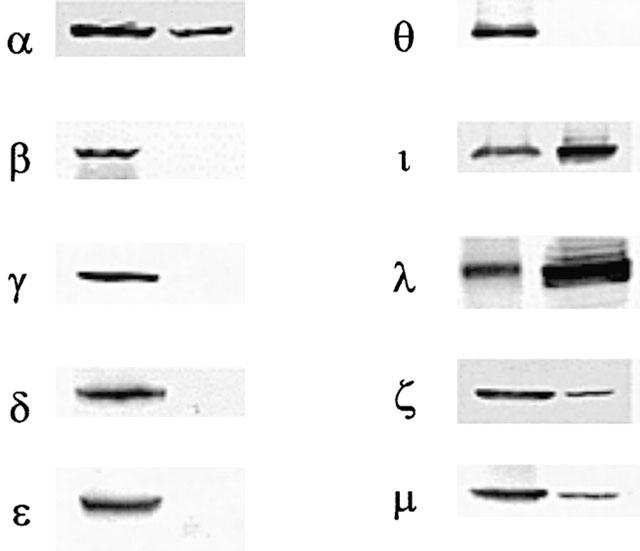

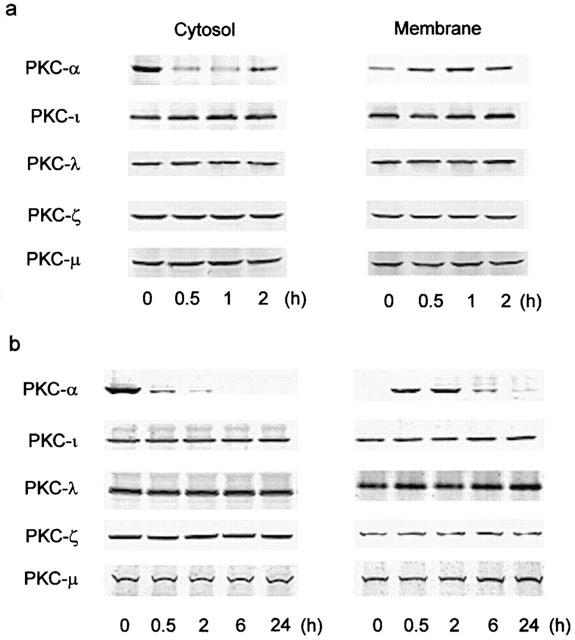

Treatment of the cells with YC-1 (50 μM) for various time intervals resulted in a decrease in PKC activity in the cytosol and an increase in PKC activity in the membrane, with a maximal effect at 60–120 min (Figure 6a). When the cells were pretreated for 30 min with ODQ (10 μM), KT-5823 (3 μM) or Go 6976 (10 μM), the YC-1-induced increase in PKC activity in the membrane was inhibited (Figure 6b). Using anti-PKC isoform (α, β, γ, δ, ε, θ, ι, λ, ζ and μ)-specific antibodies, we detected the presence of PKC-α, -ι, -λ, -ζ and-μ isoforms, but not -β, -γ, -δ, -ε and -θ isoforms, in A549 cells (Figure 7). To further determine which PKC isoforms was involved in the YC-1-mediated increase in PKC activity, the translocation of PKC isoform from cytosolic to the membrane fraction was examined by Western blotting analysis. Stimulation of the cells with 50 μM YC-1 for 0.5, 1 and 2 h or 1 μM PMA for 0.5 or 2 h resulted in translocation of PKC-α, but not PKC-ι, -λ, -ζ and -μ, from the cytosol to the membrane fraction (Figure 8a,b). However, the PKC-α levels in both membrane and cytosol fractions were decreased after 6 h PMA treatment and became undetectable at 24 h PMA treatment (Figure 8b).

Figure 6.

The PKC activity caused by YC-1 in the cytosol and membrane and effects of ODQ, KT-5823, and Go 6976 on the YC-1-induced increase in PKC activity in membrane fraction of A549 cells. Cells were treated with 50 μM YC-1 for various time intervals, or 10 nM PMA for 30 min (a), or pretreated with 10 μM ODQ, 3 μM KT, or 10 μM Go for 30 min before incubation with YC-1 (50 μM) for 60 min (b), then subcellular (cytosol and membrane) fractions were isolated. The PKC activity in the cytosol and membrane was measured as described in Methods. Results are expressed as means±s.e. mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with basal level (a) or YC-1 alone (b). KT, KT-5823; Go, Go 6976.

Figure 7.

Expression of PKC isoforms in the rat brain and A549 cells. Western blot analysis was conducted to examine the expression of PKC isoforms in A549 cells (right lane) and in the rat brain as a positive control (left lane).

Figure 8.

YC-1 and PMA induce translocation of PKC isoforms from cytosol to membrane in A549 cells. The cells were treated with 50 μM YC-1 (a), or 1 μM PMA (b) for various time intervals. The subcellular (cytosol and membrane) fractions were then isolated, the protein levels of PKC isoforms in cytosolic and membrane fractions were determined by Western blotting analysis performed as described in Methods. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results.

The role of p44/42 MAPK on the YC-1-induced COX-2 expression

To further study whether the pathway of p44/42 MAPK activation was also involved in the signal transduction pathway leading to COX-2 expression caused by YC-1, the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, was used. Pretreatment of the cells for 30 min with PD 98059 (10–50 μM) concentration-dependently attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity (Figure 9a). The YC-1-induced COX-2 expression was also markedly inhibited by PD98059 (10 and 30 μM) (Figure 9b). Since threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation of residues 202 and 204 in p44/42 MAPK caused enzymatic activation, we used anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK specific antibodies to examine the p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation of these sites as an index of kinase activation (Newton et al., 2000). Treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 (50 μM) for various time intervals resulted in p44/42 MAPK activation with a maximal response at 30 min after treatment (Figure 10a). When the cells were stimulated with PMA (10 nM) for 10, 30, 60 or 120 min, the maximal activation of p44/42 MAPK was observed at 30 min after treatment; the effect was decreased gradually after 120 min of treatment (Figure 10b). The protein level of p44/42 MAPK was not affected by YC-1 or PMA treatment (Figure 10a,b). The YC-1-induced activation of p44/42 MAPK was markedly inhibited by pretreatment of the cells for 30 min with KT-5823 (3 μM), Go 6976 (10 μM), or PD98059 (50 μM), but not with the p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580 (10 μM) (Figure 10c,d). Long-term (24 h) treatment of A549 cells with PMA (1 μM) also markedly inhibited the YC-1-mediated activation of p44/42 MAPK (Figure 10c,d). None of these treatments had any effect on the p44/42 MAPK expression (Figure 10c).

Figure 9.

Involvement of MEK in the YC-1-induced increase of COX activity and COX-2 expression in A549 cells. In (a), cells were pretreated with various concentrations of PD (MEK inhibitor) for 30 min, and then incubated with YC-1 (50 μM) for 12 h. The media were then removed, and the COX activity was measured by examining the PGE2 formation in the presence of 30 μM exogenous arachidonic acid for 30 min. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 as compared with treatment with YC-1 alone. In (b), the cells were pretreated with PD (10 and 30 μM) for 30 min and then incubated with YC-1 (50 μM) for 12 h. Immunodetection using anti-COX-2 or α-tubulin specific antibody was performed as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of α-tubulin. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. PD, PD98059.

Figure 10.

The activation of p44/42 MAPK induced by YC-1 and PMA and effects of KT-5823, Go 6976, long-term PMA treatment, PD98059 and SB203580 on the YC-1-induced p44/42 MAPK activation in A549 cells. The cells were treated with 50 μM YC-1 (a) or 10 nM PMA (b) for the indicated time intervals. In (c), the cells were pretreated with 3 μM KT, 10 μM Go, 50 μM PD or 10 μM SB for 30 min, or 1 μM PMA for 24 h before incubation with YC-1 (50 μM) for 30 min. The extracted proteins were immunodetected with antibodies specific for phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK (p-p44/42) and nonphosphorylated p44/42 MAPK (p44/42) as described in Methods. The equal loading in each lane was demonstrated by the similar intensities of p44/42. In (d), the extent of p44/42 MAPK activation were quantitated using a densitometer with Image-Pro plus software. Results were expressed as mean±s.e.mean (n=3). *P<0.05 as compared with treatment with YC-1 alone. KT, KT-5823; Go, Go 6976; PD, PD98059; SB, SB203580.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that treatment of A549 cells with YC-1, an activator of sGC, induced a 70 kDa COX-2 protein expression. Our results suggest that the activation of PKC-α and p44/42 MAPK might be involved in the signal transduction leading to the expression of COX-2 caused by YC-1 in these cells.

PGs are formed by a combined action of phospholipase A2, which liberates arachidonic acid from the sn-2 position of cellular membrane phospholipids, and COX, which converts arachidonic acid to the endoperoxide intermediate PGH2. PGH2 is subsequently converted to various PGs, such as PGE2, prostacyclin, and thromboxanes, by the action of cell-specific synthases (Vane et al., 1998). In the absence of exogenous arachidonic acid, YC-1 did not cause any change in PGE2 release. In contrast, in the presence of exogenous arachidonic acid, YC-1 markedly increased the PGE2 release. Furthermore, YC-1 caused a concentration- and time-dependent increase in COX-2 expression in A549 cells. These findings suggest that YC-1 caused the COX-2, but not phospholipase A2, expression in human pulmonary epithelial cells. Actinomycin D and cycloheximide prevented the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity and COX-2 expression, suggesting that the YC-1-induced COX-2 expression is dependent on de novo transcription and translation. Previous studies in various cell types have shown that YC-1 induced elevation of intracellular cGMP levels (Ko et al., 1994; Mulsch et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 2001). A primary downstream signalling effector of cGMP is PKG. cGMP binds to four sites on the regulatory subunit of PKG, thereby activating the catalytic subunit of the enzyme (Smolenski et al., 1998). In the present study, we showed that the sGC inhibitor, ODQ, and the inhibitor of catalytic subunit of PKG, KT-5823, significantly attenuated the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity and COX-2 expression, indicating that YC-1 activates PKG through an upstream sGC/cGMP pathway to induce COX-2 expression in A549 cells. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that the cGMP analogue, dibutyryl cGMP, increased COX-2 expression in A549 cells in a time-dependent manner. However, ODQ, at a concentration up to 30 μM did not completely suppress the YC-1-induced increases in COX activity and COX-2 expression. This result may be due to the multiple mechanisms of the YC-1 effect on cGMP accumulation. It has been demonstrated that YC-1 not only stimulates soluble guanylate cyclase but also inhibites cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase in human platelets (Friebe et al., 1998). Therefore, it is not unreasonable to observe that ODQ did not completely inhibit the YC-1-induced effects.

The activation of PKC has been demonstrated to be involved in the tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-induced COX-2 expression in human lung epithelial cells (Chen et al., 2000). In the present study, we demonstrated that the YC-1-induced increases in COX activity and COX-2 expression were reduced by the PKC inhibitors, Go 6976 and GF10923X, indicating that PKC activation is involved in the signal transduction leading to the expression of COX-2 protein by YC-1. The PKC activator, PMA, also time-dependently increased COX-2 expression (Figure 4b). In resting cells, PKCs are located predominately in the cytosol (Hecker et al., 1993). After activation, the PKCs translocate from the cytosol to the membrane fraction (Mochly-Rosen, 1995). We found that treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 caused an increase in PKC activity in the membrane. Moreover, the YC-1-mediated increase in PKC activity in the membrane was inhibited by ODQ, KT-5823 or Go 6976. These findings suggest that YC-1 may activate PKG through an upstream sGC/cGMP pathway to elicit PKC activation in A549 cells. In the present study, we also demonstrated that YC-1 caused the translocation of PKC-α only, but not other PKC isoforms, from cytosol to the membrane fraction. In a previous report, Go 6976 has been described as a preferential inhibitor of the conventional PKCs (α, β and γ) (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993; Gschwendt et al., 1996). It has been also demonstrated that GF10923X inhibits PKC-α, PKC-β, PKC-δ and PKC-ε, with a preference for the PKC-α isoform (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993). Taken together, these results indicated that the activation of PKC-α may be involved in the YC-1-mediated COX-2 expression. Previous studies have also shown that PKC-α was involved in the PMA-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and reduction of the bradykinin-evoked calcium mobilization in A549 cells (Dean et al., 1994; Levesque et al., 1997). After long-term (24 h) treatment of A549 cells with PMA, a down regulation of PKC-α was observed (Figure 8). However, this treatment caused an increase instead of a decrease of the YC-1-induced increases in COX activity and COX-2 expression (unpublished observation). One possible explanation is that PMA (1 μM) itself causes an increase in COX-2 expression and it took longer time for PMA to induce the downregulation of PKC-α than the increase of COX-2 expression.

The activation of MEK has been demonstrated to be involved in the IL-1β-induced COX-2 expression and PGE2 release in A549 cells (Newton et al., 2000). Since the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, concentration-dependently inhibited the YC-1-induced increase in COX activity and COX-2 expression, it is most likely that activation of MEK might also be involved in the induction of COX-2 caused by YC-1. Previous reports have indicated that the activation of PKG may be involved in the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine-induced p44/42 MAPK activation in rat adventitial fibroblasts (Gu et al., 2000). Furthermore, dibutyryl cGMP has been also shown to increase the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK; this effect was abolished by the PKG inhibitor, KT-5823 in rat pinealocytes (Ho et al., 1999). Moreover, in human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B), the activation of PKC-mediated p44/42 MAPK pathway was required for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) production induced by TNF-α (Reibman et al., 2000). In this study, we found that treatment of A549 cells with YC-1 or PMA also resulted in a marked activation of p44/42 MAPK (Figure 10). Furthermore, the YC-1-induced p44/42 MAPK activation was inhibited by the PKG inhibitor KT-5823, the PKC inhibitor Go 6976, or the MEK inhibitor PD98059, suggesting the activations of PKG, PKC and MEK were the upstream signals of the YC-1-induced p44/42 MAPK activation in A549 cells. Furthermore, the YC-1-mediated p44/42 MAPK activation was also inhibited by long-term (24 h) PMA treatment, suggesting the activation of PKC-α was involved in YC-1-induced p44/42 MAPK activation. We do not rule out other signal pathways which might also be involved in the YC-1-mediated COX-2 expression. In fact, we have recently found that activation of p38 MAPK is also involved in the YC-1-mediated COX-2 expression (unpublished observations).

In conclusion, YC-1 may activate PKG through an upstream sGC/cGMP pathway to elicit PKC activation, which in turn initiates p44/42 MAPK activation, and finally induces COX-2 expression. Of the PKC isoforms, only PKC-α is involved in regulating YC-1-induced COX-2 expression in A549 cells. This is the first study showing these signal transduction mechanisms involved in the sGC/cGMP-mediated COX-2 expression in such cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC89-2314-B-038-048 and NSC89-2314-B-038-045 to Dr Lin and NSC89-2320-B-038-055 to Dr Lee). We also thank Yung-Shin Pharma Ind. Co. for the kind gift of YC-1.

Abbreviations

- BCIP

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate

- cGMP

3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- COX

cyclo-oxygenase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxy-ethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

MAPK/ERK kinase

- NBT

4-nitro blue tetrazolium

- NO

nitric oxide

- NP-40

nonident P-40

- ODQ

1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinozalin-1-one

- YC-1

3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PGs

prostaglandins

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKG

protein kinase G

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulphate

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

References

- BARNES P.J., KHARITONOV S.A. Exhaled nitric oxide: a new lung function test. Thorax. 1996;51:233–237. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.C., SUN Y.T., CHEN J.J., CHIU K.T. TNF-α-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human lung epithelial cells: involvement of the phospholipase C-γ2, protein kinase C-α, tyrosine kinase, NF-κB-inducing kinase, and I-κB kinase 1/2 pathway. J. Immunol. 2000;165:2719–2728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEAN N.M., MCKAY R., CONDON T.P., BENNETT C.F. Inhibition of protein kinase C-α expression in human A549 cells by antisense oligonucleotides inhibits induction of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) mRNA by phorbol ester. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:16416–16424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEBE A., MULLERSHAUSEN F., SMOLENSKI A., WALTER U., SCHULTZ G., KOESLING D. YC-1 potentiates nitric oxide- and carbon monoxide-induced cyclic GMP effects in human platelets. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54:962–967. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASTON B., DRAZEN J.M., LOSCACALZO J., ATAMLER J.S. The biology of nitrigen oxides in the airways. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1994;149:538–551. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.7508323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GSCHWENDT M., DIETERICH S., RENNECKE J., KITTSTEIN W., MUELLER H.J., JOHANNES F.-J. Inhibition of protein kinase C mu by various inhibitors: differentiation from protein kinase C isoenzymes. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GU M., LYNCH J., BRECHER P. Nitric oxide increases p21Waf1/Cip1 expression by a cGMP-dependent pathway that includes activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p70S6K. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11389–11396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECKER M., LUCKHOFF A., BUSSE R. Modulation of endothelial autacoid release by protein kinase C: feedback inhibition or non-specific attenuation of receptor-dependent cell activation. J. Cell Physiol. 1993;156:571–578. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041560317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HO A.K., HASHIMOTO K., CHIK C.L. 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in rat pinealocytes. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:598–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUG H., SARRE T.F. Protein kinase C isoenzymes: divergence in signal transduction. Biochem. J. 1993;291:329–343. doi: 10.1042/bj2910329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON N.L., GARDNER A.M., DIENER K.M., LANGE-CARTER C.A., GLEAVY J., JARPE M.B., MINDEN A., KARIN M., ZON L.I., JOHNON G.L. Signal transduction pathways regulated by mitogen-activated/extracellular response kinase kinase kinase induce cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3229–3237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M. Signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus through the phosphorylation of transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1994;6:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KO F.N., WU C.C., KUO S.C., LEE F.Y., TENG C.M. YC-1, a novel activator of platelet guanylate cyclase. Blood. 1994;84:4226–4233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDER H.M., JACOVINA A.T., DAVIS R.J., TAURAS J.M. Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by nitric oxide-related species. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19705–19706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVESQUE L., DEAN N.M., SASMOR H., CROOKE S.T. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting human protein kinase C-α inhibit phorbol ester-induced reduction of bradykinin-evoked calcium mobilization in A549 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:209–216. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI H., OEHRLEIN S.A., WALLERATH T., IHRIG-BIEDERT I., WOHLFART P., ULSHOFER T., JESSEN T., HERGET T., FORSTERMANN U., KLEINERT H. Activation of protein kinase C α and/or ε enhances transcription of the human endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:630–637. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAIER J.A., HLA T., MACIAG T. Cyclo-oxygenase is an immediate early gene induced by interleukin-1 in human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:10805–10808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINY-BARON G., KAZANIETZ M.G., MISCHAK H., BLUMBERG P.M., KOCHS G., HUG H., MARME D., SCHACHTELE C. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isoenzymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL J.A., AKARASEREENONT P., THIEMERMANN C., FLOWER R.J., VANE J.R. Selectivity of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs as inhibitors of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:11693–11697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL J.A., LARKIN S., WILLIAMS T.J. Cyclooxygenase-2: regulation and relevance in inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;50:1535–1542. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOCHLY-ROSEN D. Location of protein kinases by anchoring proteins: a theme in signal transduction. Science (Washington DC) 1995;268:247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.7716516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCADA S., HIGGS A. The l-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N. Eng. J. Med. 1993;329:2002–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULSCH A., BAUERSACHS J., SCHAFER A., STASCH J.P., KAST R., BUSSE R. Effect of YC-1, an NO-independent, superoxide-sensitive stimulator of soluble guanylyl cyclase, on smooth muscle responsiveness to nitrovasodilators. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:681–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON R., CAMBRIDGE L., HART L.A., STEVENS D.A., LINDSA M.A., BARNES P.J. The MAP kinase inhibitors, PD098059, UO126 and SB203580, inhibit IL-1β-dependent PGE2 release via mechanistically distinct processes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1353–1361. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIKAWA K., TOKER A., JOHANNES F.J., ZHOU S.Y., CANTLEY L.C. Determination of the specific substrate sequence motifs of protein kinase c isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:952–960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature (Lond) 1988;334:661–665. doi: 10.1038/334661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science (Washington DC) 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUSSLER A.K., BILLIAR T.R. Inflammation, immunoregulation and inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Leukocyte Biol. 1993;54:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALMER R.M.J., FERRIGE A.G., MONCADA S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARENTI A., MORBIDELLI L., CUI X.-L., DOUGLAS J.G., HOOD J.D., GRANGER H.J., LEDDA F., ZICHE M. Nitric oxide is an upstream signal of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 activation in postcapillary endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:4220–4226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REIBMAN J., TALBOT A.T., HSU Y., OU G., JOVER J., NILSEN D., PILLINGER M.H. Regulation of expression of granulocyte-macrophages colony-stimulating factor in human bronchial epithelial cells: roles of protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1618–1625. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON M.J., COBB M.H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT K., SCHRAMMEL A., KOESLING D., MAYER B. Molecular mechanisms involved in the synergistic activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase by YC-1 and nitric oxide in endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:220–224. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMOLENSKI A., BURKHARDT A.M., EIGENTHALER M., BUTT E., GAMBARYAN S., LOHMANN S.M., WALTER U. Functional analysis of cGMP-dependent protein kinases I and II as mediators of NO/cGMP effects. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;358:134–139. doi: 10.1007/pl00005234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWIERKOSZ T.A., MITCHELL J.A., WARNER T.D., BOTTING R.M., VANE J.R. Co-induction of nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase: interactions between nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1335–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TETSUKA T., DAPHNA-IKEN D., MILLER B.W., GUAN Z., BAIER L.D., MORRISON A.R. Nitric oxide amplifies interleukin-1 induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in rat mesangial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2051–2056. doi: 10.1172/JCI118641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANE J.R. Pharmacology: towards a better aspirin. Nature (Lond) 1994;367:215. doi: 10.1038/367215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANE J.R., BAKHLE Y.S., BOTTING R.M. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;38:97–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANE J.R., MITCHELL J.A., APPLETON I., TOMLINSON A., BISHOP-BAILEY D.A., CROXTALL J., WILLOUGHBY D. Inducible isoforms of cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase in inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:2046–2050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATKINS D.N., GARLEPP M.J., THOMPSON P.J. Regulation of the inducible cyclo-oxygenase pathway in human cultured airway epithelial (A549) cells by nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1482–1488. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEGENER J.W., NAWRATH H. Activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by YC-1 in aortic smooth muscle but not in ventricular myocardium from rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1523–1529. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU C.C., KO F.N., KUO S.C., LEE F.Y., TENG C.M. YC-1 inhibited human platelet aggregation through NO-independent activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:1973–1978. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE W.L., CHIPMAN J.G., ROBERTSON D.L., ERIKSON R.L., SIMMONS D.L. Expression of a mitogen-responsive gene encoding prostaglandin synthase is regulated by mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:2692–2696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]