Abstract

Mechanisms underlying K+-induced hyperpolarizations in the presence and absence of phenylephrine were investigated in endothelium-denuded rat mesenteric arteries (for all mean values, n=4).

Myocyte resting membrane potential (m.p.) was −58.8±0.8 mV. Application of 5 mM KCl produced similar hyperpolarizations in the absence (17.6±0.7 mV) or presence (15.8±1.0 mV) of 500 nM ouabain. In the presence of ouabain +30 μM barium, hyperpolarization to 5 mM KCl was essentially abolished.

In the presence of 10 μM phenylephrine (m.p. −33.7±3 mV), repolarization to 5 mM KCl did not occur in the presence or absence of 4-aminopyridine but was restored (−26.9±1.8 mV) on addition of iberiotoxin (100 nM). Under these conditions the K+-induced repolarization was insensitive to barium (30 μM) but abolished by 500 nM ouabain alone.

In the presence of phenylephrine + iberiotoxin the hyperpolarization to 5 mM K+ was inhibited in the additional presence of 300 nM levcromakalim, an action which was reversed by 10 μM glibenclamide.

RT–PCR, Western blotting and immunohistochemical techniques collectively showed the presence of α1-, α2- and α3-subunits of Na+/K+-ATPase in the myocytes.

In K+-free solution, re-introduction of K+ (to 4.6 mM) hyperpolarized myocytes by 20.9±0.5 mV, an effect unchanged by 500 nM ouabain but abolished by 500 μM ouabain.

We conclude that under basal conditions, Na+/K+-ATPases containing α2- and/or α3-subunits are partially responsible for the observed K+-induced effects. The opening of myocyte K+ channels (by levcromakalim or phenylephrine) creates a ‘K+ cloud' around the cells which fully activates Na+/K+-ATPase and thereby abolishes further responses to [K+]o elevation.

Keywords: EDHF, Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms, ouabain, potassium, hyperpolarization, immuno-histochemistry, phenylephrine, iberiotoxin, 4-aminopyridine

Introduction

Small increases in extracellular potassium concentration ([K]o) can generate a vasodilation which results in an increase in local blood flow of physiological significance. Thus, the loss of K+ from contracting skeletal muscle cells is believed to increase blood flow to active muscle bundles (Skinner & Powell, 1967; Juel et al., 2000). Similarly, the efflux of K+ from neurones in active regions of the CNS produces a local vasodilatation which helps to ensure an increased supply of oxygen and nutrients to ‘busy' regions (Kuschinsky & Wahl, 1978). More recently, Edwards et al. (1998) proposed that the activation of vascular endothelial K+ channels and the resulting outflow of K+ could hyperpolarize and relax the underlying vascular smooth muscle in some rat arteries. Therefore in these vascular beds, K+ acts as the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF), the identity of which has been the subject of much speculation (see reviews by Taylor & Weston, 1988; Garland et al., 1995; Edwards & Weston, 1998; Félétou & Vanhoutte, 2000).

The direct smooth muscle vasodilator action of K+ in rat mesenteric arteries and the proposed identity of EDHF in this vessel as ionised K+ have both been questioned following myograph studies in phenylephrine-contracted rat vessels (Andersson et al., 2000; Doughty et al., 2000; Lacy et al., 2000). Subsequently, however, detailed microelectrode experiments have shown that the opening of smooth muscle K+ channels by phenylephrine produces a ‘K+ cloud' around the muscle and that this phenomenon prevents the vasodilator action of exogenously-applied K+ (Richards et al., 2001). This leaves open the possibility that under physiological conditions of moderate to low vascular tone, endothelium-derived K+ can indeed function as a local intravascular vasodilator (Richards et al., 2001).

A key component in K+-induced vasodilation is the smooth muscle Na+/K+-ATPase (McCarron & Halpern, 1990; Prior et al., 1998), a family of proteins consisting of ion-transporting α- and modulatory β- and γ-subunits. The different isoforms of the Na+/K+-ATPase display different affinities for [K+]o. The α1-containing isoforms (which in the rat are relatively insensitive to ouabain) may be considered as ubiquitous, ‘housekeeping' forms which are fully activated by physiological concentrations of [K+]o (∼5.9 mM). In contrast, the α2-and α3-containing isoforms are further activated by small increases in [K+]o and may act as ‘reserves' (Blanco & Mercer, 1998; Crambert et al., 2000).

The purpose of this study was to confirm the involvement of Na+/K+-ATPase in K+-induced hyperpolarization of the rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle and to identify the α-subunit isoforms present in this preparation. A preliminary account of some of these observations has been presented (Burnham et al., 2000).

Methods

Tissue dissection

Male Sprague–Dawley rats were killed by stunning and cervical dislocation. Whole mesenteric beds were placed in ice-cold Krebs solution (mM) NaCl 118, KCl 3.4, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3, 25, glucose 11, gassed with 5% CO2 in O2, and arteries were dissected free of surrounding tissue. Endothelium-intact vessels were used to provide samples for RT–PCR and Western blots.

Microelectrode studies

Small mesenteric arteries were pinned to the Sylgard base of a heated bath (10 ml) and superfused with Krebs solution containing 10 μM indomethacin and 300 μM NG-nitro-L-arginine (10 ml min−1, 37°C). Smooth muscle cells were impaled from the adventitial side using microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl (tip resistance 50–80 MΩ). Recordings were made using a conventional high-impedance amplifier (Intra 767; WPI Instruments) and microelectrode recordings were digitized and analysed using a MacLab system (AD Instruments). Endothelial cells were removed by perfusing vessels with distilled water, and the lack of a functional endothelium was confirmed by an absence of response to acetylcholine. Levcromakalim, added directly to the bath to produce a transient, calculated concentration of 10 μM, was used to indicate the ability of the smooth muscle cells to hyperpolarize following endothelium removal and drug treatments. Phenylephrine (10 μM), 4-aminopyridine (5 mM), iberiotoxin (100 nM), levcromakalim (300 nM) and ouabain (500 nM or 500 μM) were added to the Krebs superfusing the bath. KCl (16.6 μl of 3 M stock) was added as a bolus directly into the 10 ml bath, close to the Krebs inflow, to produce (assuming rapid mixing) a calculated transient 5 mM elevation in extracellular K+ concentration. In some experiments, tissues were incubated in K+-free Krebs solution to inhibit all isoforms of Na+/K+-ATPase and the hyperpolarization induced by re-introduction of K+ (ie. superfusion with normal Krebs solution) was monitored in the absence or presence of ouabain. For these experiments, KCl and KH2PO4 were replaced by appropriate, equimolar concentrations of NaCl or NaH2PO4, respectively, in the Krebs solution. Endothelium-denuded segments of artery were incubated for at least 30 min in K+-free Krebs solution before the start of the experiment and, where appropriate, were exposed to ouabain for at least 10 min before the re-introduction of K+.

Gene-specific RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from rat mesenteric arteries and brain using QIAGEN RNEasy Mini kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following DNAse treatment, cDNA synthesis was performed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase. RT–PCR primers, designed to amplify bases 3252-3410 of rat α1 (NCBI accession number NM_012504), 4797-5040 of rat α2 (NM_012505) and 3324-3529 of rat α3 (NM_012506), comprised: α1-forward: 5′ GAAGCTCATCATCAGGCGACG3′, α1-reverse: 5′ CCAGGGTAGAGTTCCGAGCTC3′, α2-forward: 5′ GGGCCTGACTAATTTGAGATCACTG3′, α2-reverse: 5′ GTCTCACAGAAGGTCACCAGTAAGG3′, α3-forward: 5′ CCACACCTCGGTTACCTCTCAC3′, α3-reverse: 5′ CAGATTTAGAACCGGAGATGGC3′.

Hot-start RT–PCR was performed for 35 cycles with an annealing temperature of 60°C and 1.5 mM MgCl2. RT–PCR products were visualized using 1.5% agarose-ethidium bromide gels. To confirm identity, PCR products were cloned using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and sequenced using a Big Dye Terminator Kit (PE Applied Biosystems). Reaction products for sequencing were submitted to the central sequencing facility in the School of Biological Sciences, University of Manchester for analysis.

Western blotting

Rat kidney, heart, brain and mesenteric arteries were homogenized on ice in homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.25 M sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, Sigma protease inhibitor cocktail Sigma P2714) using ground-glass homogenizers. Homogenates were cleared by centrifugation for 10 s at 12,000×g. Mesenteric artery samples were prepared as particulate fractions by centrifuging post-nuclear supernatants at 100,000×g for 30 min at 4°C before resuspending pellets in homogenization buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (1976) using Bio-Rad reagent. Western blot samples were prepared in 5 fold concentrated Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) and heated to 100°C for 5 min.

Sodium dodecylsulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), on 6% (w v−1) acrylamide separating gels, and electrophoretic transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes were performed as previously described (Laemmli, 1970; Towbin et al., 1979). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 50 mg ml−1 non-fat dried milk in Tween-Tris buffered saline (1 μl ml−1 Tween-20, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0 (pH 6.8 for α2), 150 mM NaCl). Blots were probed with monoclonal antibodies M8P1A3 (anti-α1, dilution 1 : 1000), McB2 (anti-α2, dilution 1 : 250) and XVIF9-G10 (anti-α3, dilution 1 : 4000) for 1 h at room temperature, except α2 which was incubated overnight at 4°C. Detection was achieved using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL reagents.

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

Arteries were immersed in periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde fixative (McClean & Nakane, 1974) for 20 min and cryoprotected overnight in 0.3 g ml−1 sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After embedding in OCT compound, 4 μm cryostat sections were collected on silanated microscope slides. Sections were treated with 1 mg ml−1 SDS in PBS for 30 min, washed in PBS and blocked for 1 h with blocking buffer (50 μl ml−1 normal goat serum, 10 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin in PBS). Primary antibodies (dilutions: anti-α1, 1 : 50, anti-α2, 1 : 5 and anti-α3, 1 : 50; anti-von Willebrand's factor and anti-muscle actin, each 1 : 100) were applied for 1 h and secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red (α1) or Cy3 (α2 and α3) were applied for 30 min together with 5 μg ml−1 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) as a blue-fluorescent nuclear stain. Sections were viewed with a Zeiss epifluorescence Axioplan 2 microscope. Image capture and pseudocolouring were performed using Zeiss KS300 software. Identical microscope, camera and software settings were used when imaging labelled sections and negative controls.

Materials

For the microelectrode studies the following substances were used: synthetic iberiotoxin (Latoxan, France) and levcromakalim (SmithKline Beecham). All other reagents were supplied by Sigma U.K.

RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen), Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), DNase (Life Technologies, amplification grade) Ex-Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Biomedicals) and custom oligonucleotides (Sigma-Genosys) were used in cDNA production and PCR. Original TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and Big Dye Terminator sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer) were used for PCR product cloning and sequencing. Primary antibodies anti-α1 and anti-α3 were obtained from Affinity Bioreagents. Anti-α2 was kindly provided by K.J. Sweadner. Anti-von Willebrand's factor was from Novocastra and anti-muscle actin (mouse monoclonal; clone HHF35) was purchased from Dako). Secondary antibody conjugates were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch (Stratech Scientific Ltd, U.K). OCT® compound was obtained from R.A. Lamb Ltd (East Sussex, U.K.). All other reagents were supplied by Sigma U.K.

Data analysis

All values are given as mean±s.e.mean; n indicates the number of arteries from which membrane potential recordings were made. Student's t-test (paired observations) was used to assess the probability that differences between mean values had arisen by chance. P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Microelectrode studies

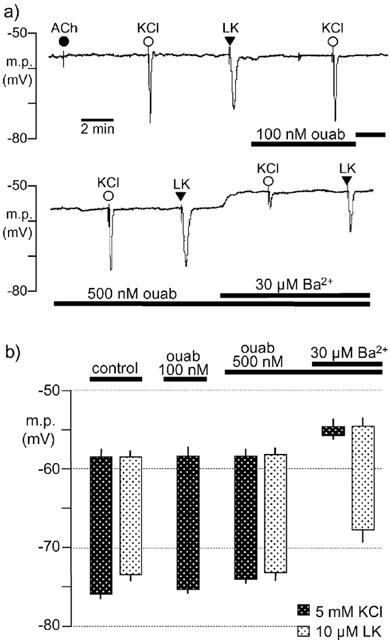

The basal resting membrane potential of smooth muscle cells in endothelium-denuded vessels was −58.8±0.8 mV (n=4). A transient increase in extracellular K+ by 5 mM produced a smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization of 19.4±1.4 mV (n=4). The hyperpolarization to 5 mM KCl in four arteries was similar in the absence (17.6±0.7 mV) or presence of 500 nM ouabain (15.8±1.0 mV) (Figure 1). However, in the additional presence of 30 μM barium (which itself depolarized the membrane by 3.4±0.6 mV) the hyperpolarization to 5 mM KCl was almost abolished (1.1±0.9 mV, n=4) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of ouabain and barium on hyperpolarizations induced by 5 mM KCl and levcromakalim in rat endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries. (a) Typical trace showing the initial smooth muscle hyperpolarization induced by transient application of 5 mM KCl and 10 μM levcromakalim (LK) in the absence (control) and presence of ouabain (ouab) and barium (Ba2+) as indicated by the horizontal bars. In all experiments, removal of the endothelium was confirmed by a lack of response to 10 μM acetylcholine (ACh). (b) Graphical representation of data from four separate experiments of the type shown in (a). Each column represents the mean membrane potential (m.p.) before (+s.e.mean) and after (−s.e.mean) addition of 5 mM KCl or 10 μM levcromakalim, in the absence (control) and sequential presence of ouabain (ouab) and barium (Ba2+).

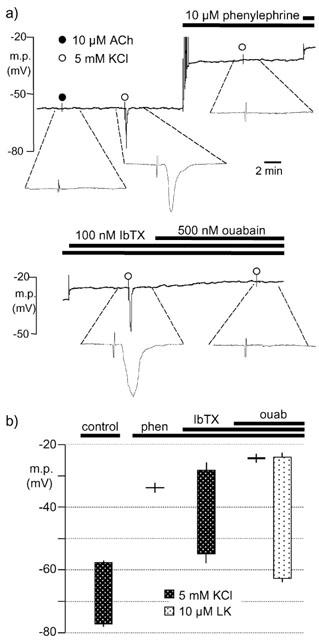

In the presence of 10 μM phenylephrine, the smooth muscle cell membrane depolarised to −33.7±2.8 mV (n=4) and a subsequent transient increase in extracellular K+ by 5 mM was without effect (see Figure 2a). In the continued presence of phenylephrine, the inclusion of 100 nM iberiotoxin in the bathing solution produced a further depolarization (5.6±1.1 mV, n=4). This was, however, larger than the small, but significant, depolarization produced by iberiotoxin in the absence of phenylephrine (1.6±0.4 mV, n=8). In the presence of phenylephrine and iberiotoxin, a transient increase in extracellular K+ by 5 mM partially repolarized the muscle cells (by 26.9±1.8 mV, n=4). Subsequent exposure to 500 nM ouabain produced a further small depolarization of smooth muscle cell membranes (3.9±1.7 mV, n=4) and abolished the response to a transient increase (5 mM) in extracellular K+ (see Figure 2b), whereas 10 μM levcromakalim produced a hyperpolarization of 39.1±0.4 mV (n=4). The extent to which ouabain depolarized the smooth muscle in the presence of phenylephrine and iberiotoxin was dependent on the membrane potential prior to its addition. Thus, in the presence of phenylephrine, the response to ouabain was small in artery segments in which iberiotoxin had produced a marked depolarization (see Figure 2a). However, in artery segments depolarized by 10 μM phenylephrine (which depolarized the membrane from −58.5±0.5 to −30.5±1.8 mV, n=4) but in the absence of iberiotoxin, the depolarizing effect of 500 nM ouabain was more marked (8.2±0.9 mV, n=4).

Figure 2.

Effect of phenylephrine, iberiotoxin and ouabain on hyperpolarizations induced by 5 mM K+ in rat endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries. (a) Typical, single trace showing changes in smooth muscle membrane potential (m.p.) in response to transient application of 5 mM KCl (open circle) in the absence and presence of phenylephrine, iberiotoxin (IbTX) and ouabain as indicated by the horizontal bars. For clarity, the trace has been divided with some overlap such that the depolarization on addition of iberiotoxin is duplicated. In addition, 1 min portions of the trace have been expanded to allow the responses to be distinguished from the injection artefacts. (b) Graphical representation of data from four separate experiments of the type shown in (a). Each column represents the membrane potential before (+s.e.mean) and after (−s.e.mean) addition of 5 mM K+, in the absence (control) and sequential presence of 10 μM phenylephrine (phen), 100 nM IbTX and 500 nM ouabain (ouab).

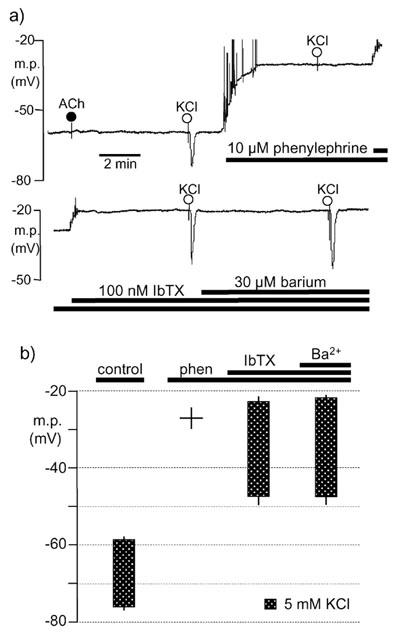

In contrast to ouabain, 30 μM barium was without effect on the membrane potential in the presence of 10 μM phenylephrine +100 nM iberiotoxin and did not inhibit the subsequent hyperpolarization to 5 mM KCl (Figure 3). However, under these conditions, a low concentration of levcromakalim (which itself repolarized the smooth muscle by 8.4±0.4 mV; n=4) markedly inhibited the hyperpolarization to 5 mM KCl (Figure 4). Depolarization and elevation of intracellular calcium potentially lead to the opening of both BKCa and delayed rectifier K+ channels (KV). Since, in the presence of phenylephrine, the hyperpolarization to K+ could be restored by iberiotoxin (an inhibitor or BKCa), the effect of 4-aminopyridine (an inhibitor of KV) was also determined. In the presence of 10 μM phenylephrine (m.p. −29.1±0.4 mV, n=4), application of 5 mM 4-aminopyridine produced a further depolarization of 4.0±0.7 mV, but 5 mM KCl had no effect in either the absence or presence of 4-aminopyridine. In the additional presence of 100 nM iberiotoxin the hyperpolarizing effect of KCl (30.3±1.7 mV, n=4) was restored.

Figure 3.

Lack of inhibitory effect of barium on hyperpolarizations induced by 5 mM K+, in the presence of phenylephrine and iberiotoxin, in rat endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries. (a) Typical single trace showing the smooth muscle hyperpolarization induced by transient application of 5 mM KCl in the absence (control) and presence of phenylephrine, iberiotoxin and barium as indicated by the horizontal bars. For clarity, the trace has been divided with some overlap such that the depolarization on addition of iberiotoxin is duplicated. In all experiments, removal of the endothelium was confirmed by a lack of response to 10 μM acetylcholine (ACh). (b) Graphical representation of data from four separate experiments of the type shown in (a). Each column represents the membrane potential (m.p.) before (+s.e.mean) and after (−s.e.mean) addition of 5 mM KCl, in the absence (control) and sequential presence of 10 μM phenylephrine (phen), 100 nM iberiotoxin (IbTX) and 30 μM barium (Ba2+).

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effect of levcromakalim on hyperpolarizations induced by 5 mM K+, in the presence of phenylephrine and iberiotoxin, in rat endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries. (a) Typical trace showing the smooth muscle hyperpolarization induced by transient application of 5 mM KCl in the presence of phenylephrine (10 μM) and iberiotoxin (100 nM). The response was inhibited by exposure to 300 nM levcromakalim (LK) and restored by 10 μM glibenclamide (glib) in the continued presence of levcromakalim. In all experiments, removal of the endothelium was confirmed by a lack of response to 10 μM acetylcholine (ACh). (b) Graphical representation of data from four separate experiments of the type shown in (a). Each column represents the membrane potential (m.p.) in the presence of phenylephrine and iberiotoxin before (+s.e.mean) and after (−s.e.mean) addition of 5 mM KCl, in the absence (control) and sequential presence of 300 nM levcromakalim (LK) and 10 μM glibenclamide (glib).

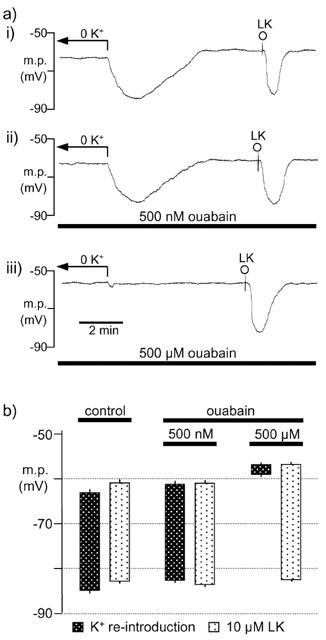

Re-introduction of K+ following a period of at least 30 min in K+-free Krebs hyperpolarized the smooth muscle (Figure 5). Essentially, neither the resting membrane potential nor this hyperpolarization was modified in segments of artery which had been subjected to 20 min incubation with 500 nM ouabain. This contrasts with the ability of such a concentration of ouabain to abolish the hyperpolarization induced by a 5 mM transient elevation of extracellular K+ as shown in Figures 1 and 2 (although in the absence of phenylephrine there was a requirement for the additional presence of 30 μM barium to inhibit the inwardly-rectifying K+ channel; Figure 1). However, the higher concentration of ouabain (500 μM) used in these K+ re-introduction experiments depolarized the smooth muscle to −56.8±0.4 mV and almost abolished the effect of K+ re-introduction (Figure 5). Neither 500 nM ouabain nor 500 μM ouabain modified the membrane potential to which 10 μM levcromakalim hyperpolarized the smooth muscle (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of ouabain on hyperpolarization induced by K+-reintroduction (to 4.6 mM) following a period of at least 30 min in K+-free Krebs (0 K+). (a) Typical traces showing the hyperpolarization in the absence (i) or in the presence of 500 nM (ii) or 500 μM (iii) ouabain. Levcromakalim (10 μM; LK) was added as a positive control. (b) Graphical representation of data from four separate experiments of the type shown in (a). The columns represent either the membrane potential (m.p.) in K+-free Krebs and the peak hyperpolarization following the switch to normal Krebs or that in normal Krebs before (+s.e.mean) and after (−s.e.mean) addition of 10 μM levcromakalim, in the absence (control) and presence of ouabain.

Analysis of α-subunit expression

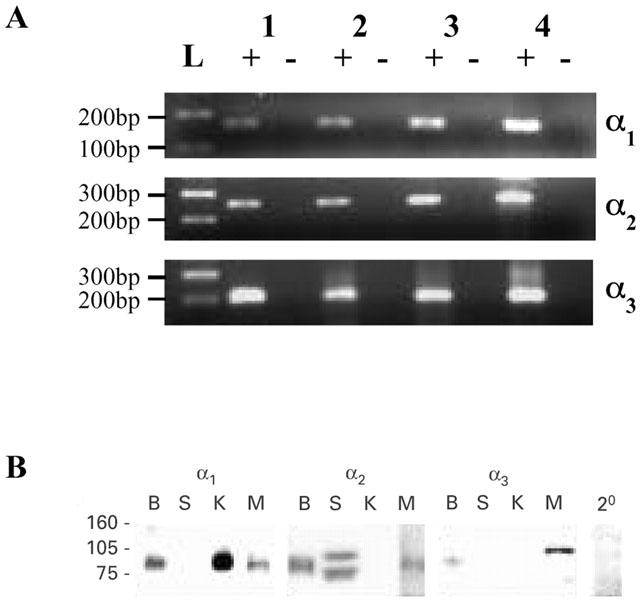

The expression of Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit isoforms in rat mesenteric arteries was examined by RT–PCR and Western blotting. RT–PCR, using primer pairs designed for the detection of each isoform, was performed in rat mesenteric artery cDNA preparations obtained from three rats. Messenger RNA for Na+/K+-ATPase α1-, α2- and α3-subunits (159, 244 and 206 base-pair products, respectively) was detected in all three mesenteric artery samples (Figure 6a). Rat brain cDNA, which contains all three isoforms, was included as a positive control and detection of GAPDH housekeeping gene in each mesenteric artery sample verified cDNA integrity (not shown). The identity of each product was confirmed by cloning and sequencing. No products were amplified from template which was prepared without reverse transcription, thus excluding contamination by genomic DNA.

Figure 6.

Detection of Na+/K+ ATPase α-subunits by RT–PCR and Western blot analysis. (a) RT–PCR products of the expected sizes were detected in rat mesenteric artery (lanes 1–3) and rat brain (positive control, lane 4) cDNA samples prepared with (+), but not without (−), reverse transcription. For size comparison, a 100 base-pair DNA ladder is indicated (L). (b) Western blot analysis of rat mesenteric artery samples (M), together with control samples from rat kidney (K; which predominantly expresses the α1 isoform), skeletal muscle (S; which predominantly expresses the α2 isoform) and brain (B; which expresses all three isoforms). The lack of reactivity of secondary antibody alone with the mesenteric artery (2o) is evident. Molecular weight markers are indicated (kDa).

Samples of rat mesenteric artery were prepared for Western blotting, together with control samples from rat kidney (which predominantly expresses the α1 isoform) skeletal muscle (which predominantly expresses the α2 isoform) and brain (which expresses all three isoforms) (see Blanco & Mercer, 1998). The monoclonal, isoform-specific antibodies detected proteins of approximately the size expected for Na+/K+-ATPase α subunits (97.5 kDa) in the appropriate control tissues (Figure 5b), supporting the well-documented specificity of these antibodies towards rat α-subunit isoforms (Malik et al., 1993; Arystarkhova & Sweadner, 1996). In rat mesenteric artery samples, the α1, α2 and α3 isoforms were detected using 5, 60 and 25 μg protein loadings, respectively (Figure 6b).

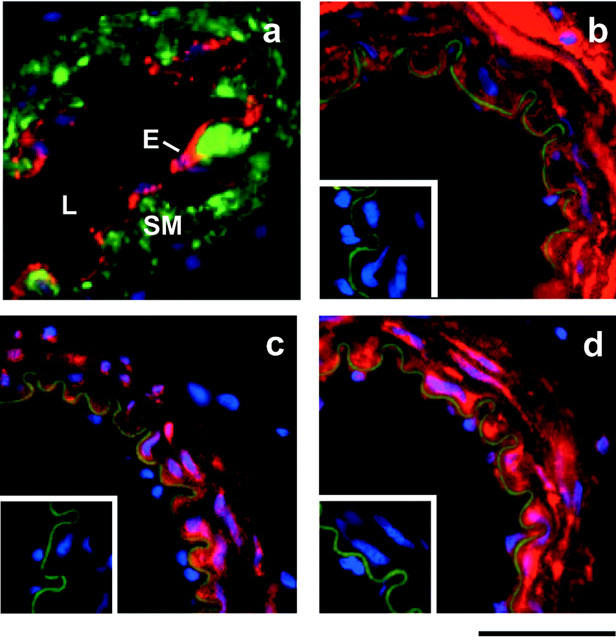

Immunofluorescence labelling

Cryostat sections of rat mesenteric artery were labelled using the monoclonal antibodies specific to the α-subunit isoforms. Visualization of primary antibody binding was achieved using secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red or Cy3 (pseudo-coloured red, Figure 7); nuclei labelled with DAPI appear blue (Figure 7). The intrinsic autofluorescence of the internal elastic lamina was visible through the green filter-set, and was included in images to indicate the smooth muscle-endothelium boundary. This green autofluorescence did not interfere with the red signal from the secondary antibodies. Examination of multiple mesenteric artery sections from three rats indicated that the α1, α2, and α3 isoforms were all expressed in the smooth muscle. Endothelial labelling for the α1 and α3 isoforms was also apparent (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Localization of Na+/K+ ATPase α-subunits by immunofluorescence labelling. The positions of the lumen (L), endothelium (E) and smooth muscle (SM) are as indicated in (a) in which sections were dual-labelled with anti-von Willebrand's factor (red) and anti-muscle actin (green). (b) α1-, (c) α2- and (d) α3- labelling was present in the smooth muscle cell layers of rat mesenteric arteries. Negative controls (no primary antibody) are shown as insets. In all sections, DAPI-stained nuclei appear blue and in (b), (c) and (d) anti-α-subunit immunoreactivity appears red and the autofluorescence of the internal elastic lamina is green. Scale bar indicates 50 μm.

Discussion

The role of the Na+/K+-ATPase in K+-induced hyperpolarizations of rat mesenteric artery has been investigated together with the expression of Na+/K+-ATPase α1-, α2- and α3-subunits. The Na+/K+-ATPase α4-subunit was not investigated in this study, as it is believed to be restricted to the testis and epididymis (Shamraj & Lingrel, 1994; Underhill et al., 1999).

In agreement with previous work (Richards et al., 2001), the present study showed that pre-stimulating endothelium-denuded rat mesenteric arteries with 10 μM phenylephrine abolished the smooth muscle hyperpolarization in response to transient 5 mM increases in [K+]o. However, this observation was extended by the demonstration that K+-induced hyperpolarizations were restored by iberiotoxin alone and that 4-aminopyridine was totally without effect. Thus, the restoration of the hyperpolarization to K+ by the combination of iberiotoxin and 4-aminopyridine, which was previously reported (Richards et al., 2001), is due solely to the effect of iberiotoxin. This suggests that the formation of a ‘K+ cloud' by K+ efflux via the large-conductance calcium-sensitive K+ channel (BKCa) plays a major role in preventing the hyperpolarizing effects of transient increases in [K+]o in phenylephrine-stimulated preparations.

Although we have not directly measured an increase in the [K+]o between the smooth muscle cells, such an increase is consistent with changes in the hyperpolarizing effect of levcromakalim. Thus, 10 μM levcromakalim hyperpolarized to −73.3±0.8 mV (n=4) in the presence of 10 μM phenylephrine but to −82.1±0.7 mV (n=12) in its absence. At this concentration of 10 μM we assume that levcromakalim hyperpolarizes to the K+ equilibrium potential (EK), and thus it appears that phenylephrine modifies EK. If it assumed that this concentration (10 μM) of levcromakalim hyperpolarizes to EK, phenylephrine (10 μM) must shift EK by approximately 10 mV in a depolarizing direction. Using the Nernst equation (see Hamilton et al., 1986) such a shift in EK could be explained by an increase in extracellular K+ of approximately 5 mM.

The depolarization induced on exposure to iberiotoxin in the presence of phenylephrine suggests that some BKCa channels are contributing to the net membrane potential. The fact that the membrane remains very depolarized under these conditions indicates that the dominant conductance is likely to be due to open Cl− channels (Large & Wang, 1996) rather than to BKCa.

An interesting observation from the present study was that when 10 μM phenylephrine was present, the membrane potential in the additional presence of 500 nM ouabain (21.9±1.2 mV, n=4) was not significantly different from that in the presence of 100 nM iberiotoxin (−20.3±2.9 mV, n=8), of iberiotoxin + 500 nM ouabain (−23.5±1.2 mV, n=4) or of iberiotoxin + 4-aminopyridine (−22.1±1.9 mV, n=8). Thus, despite the fact that ouabain, 4-aminopyridine and iberiotoxin each produce depolarization by different mechanisms, the steady-state membrane potential is approximately −22 mV. The calculated Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) in smooth muscle lies in the range −25 to −20 mV (Aickin & Brading, 1983; Large & Wang, 1996). It thus appears that the dominant membrane conductance in the presence of phenylephrine is due to the presence of open chloride channels. Almost certainly, the proximity of the membrane potential to ECl contributes to the lack of depolarization to K+ observed. Under conditions in which hyperpolarization to K+ does not occur (which we assume is due to saturation of Na+/K+-ATPase), it would be expected that elevation of [K+]o would have a depolarizing effect due to the change in EK. Such an effect was never observed, presumably partially because of the dominance of the Cl− conductance, but perhaps also due to the opening of additional BKCa channels in response to the depolarization.

The inability of K+ to induce hyperpolarization in the presence of phenylephrine could be explained by a reduction in membrane resistance due to the presence of open chloride channels such that, despite the current carried by Na+/K+-ATPase, there was no voltage change (since V=IR : Ohm's law). However, previous studies were able to exclude a reduction in smooth muscle input resistance as the primary cause underlying the loss of K+-induced hyperpolarization (Richards et al., 2001). In addition, ouabain (500 nM) produced a further depolarization in the presence of phenylephrine, suggesting that the Na+/K+-ATPase is indeed contributing to the membrane potential. Collectively, the data favour the interpretation that the ouabain-sensitive, K+-responsive isoforms of Na+/K+-ATPase are maximally activated in the presence of phenylephrine due to the presence of a ‘K+ cloud' in the interstitial spaces.

The present study confirms that in non-depolarized preparations, a combination of 30 μM barium and 500 nM ouabain was required to inhibit K+-induced hyperpolarization of rat hepatic arteries, thus implicating both an inward-rectifier K+ channel and Na+/K+-ATPase in the response (Edwards et al., 1999). However, in the presence of phenylephrine, when K+-induced hyperpolarizations were restored by iberiotoxin, 500 nM ouabain alone completely inhibited the hyperpolarizing effects of transient increases in [K+]o. Since phenylephrine produced a large depolarization, the inward-rectifier K+ channel (which is inhibited by 30 μM barium) should not conduct outward K+ current. Indeed the present data showed a complete lack of effect of barium in the presence of the spasmogen, confirming unexplained earlier observations (Dora & Garland, 2001). Thus, whereas hyperpolarization due to activation of the Na+/K+ ATPase by elevations in [K+]o can occur in both resting and phenylephrine-stimulated preparations (provided that the proposed formation of a K+ cloud is prevented), inwardly-rectifying potassium channels only contribute to hyperpolarization in non-stimulated vessels. The activation of Na+/K+-ATPase by the K+ cloud is further supported by the intrinsic depolarizing effect of a low concentration of ouabain in the presence but not in the absence of phenylephrine.

To test further the ‘K+ cloud' hypothesis, vessels pre-treated with phenylephrine in the presence of iberiotoxin were exposed to levcromakalim, an opener of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP). Under these conditions, a K+ cloud was presumably generated by K+ efflux through KATP and the hyperpolarizing effects of added K+ were virtually abolished. In the additional presence of the KATP inhibitor glibenclamide the hyperpolarizing effect of K+ elevation was restored.

Although this observation is consistent with the ‘cloud' hypothesis, it is possible (as discussed earlier) that the opening of KATP reduced membrane resistance sufficiently to diminish the hyperpolarizing effects of the current generated by Na+/K+-ATPase. However, a low concentration of levcromakalim was chosen to minimise any decrease in membrane resistance and earlier experiments (Richards et al., 2001) provided no evidence that a decrease in membrane resistance could account for the loss of K+-induced hyperpolarization in the presence of phenylephrine. Collectively, therefore, the results favour the view that the loss of K+-induced hyperpolarization in the presence of phenylephrine alone or following exposure to phenylephrine+iberiotoxin+levcromakalim are mainly the result of K+ cloud formation rather than of a lowering of membrane resistance.

Rat Na+/K+ ATPase α-subunits show differing sensitivities to inhibition by ouabain, such that the ouabain IC50 is approximately 50 μM for the α1-subunit, whereas for the α2 or α3 isoforms the IC50 values are in the nanomolar range (O'brien et al., 1994). In addition, the different Na+/K+-ATPase α subunits show a varying degree of activation in response to changes in extracellular K+, a phenomenon which may be modulated by the β subunit (for references see Hasler et al., 1998). Studies of the kinetic characteristics of rat Na+/K+-ATPase isozymes in insect Sf-9 cells suggest that whereas α1-containing isoforms are maximally activated at physiological [K+]o, the α2-and α3-containing isoforms can increase their activity in response to small elevations in K+ concentration (Blanco & Mercer, 1998). The functional significance of this observation has been verified in guinea-pig mesenteric resistance artery smooth muscle cells in which an increase in [K+]o from 5 to 10 mM increases Na+/K+-ATPase currents (Nakamura et al., 1999).

In the present study, 500 nM ouabain had little effect on the resting membrane potential in the absence of phenylephrine but produced depolarization in the presence of this agonist. This suggests that the isoform of Na+/K+-ATPase which is stimulated by elevation of extracellular K+ (either by exogenous KCl or by K+ which effluxes from smooth muscle BKCa channels : see Richards et al., 2001) is not active under the basal conditions but is active in the presence of phenylephrine. In contrast, the hyperpolarization produced by reintroduction of potassium ions after incubation in potassium-free solution was ouabain-resistant and this electrical change therefore appears to result predominantly from re-activation of the α1 isoform. A high concentration of ouabain (500 μM), which would inhibit the α1-containing isoform of Na+/K+-ATPase (Blanco & Mercer, 1998), did produce smooth muscle depolarization, indicating that this isoform is active under basal conditions. We have previously shown in the rat hepatic artery that 1 mM ouabain has very little effect on the hyperpolarizing action of K+ on de-endothelialised vessels in the absence of barium (Edwards et al., 1998). Barium alone (30 μM) also only had a small inhibitory effect on the response to K+, although together barium+ouabain abolished the hyperpolarization to K+ (Edwards et al., 1998). This suggests that depolarizing effects of high concentrations of ouabain are due to selective inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase, with little, if any, effect which is attributable to inhibition of inwardly-rectifying K+ channels (which may also contribute to the resting membrane potential; Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Thus, the hyperpolarizing Na+/K+-ATPase currents which have been recorded from vascular smooth muscle cells ‘at rest' (Quinn et al., 2000) are almost certainly due to the activity of an α1-isoform, whereas (as previously proposed, Edwards et al., 1999) α2- and/or α3-isoforms are likely to be responsible for the K+-induced hyperpolarization.

Our molecular studies indicate that rat mesenteric arteries do indeed express mRNA transcripts for Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms responsive to raised K+ (α2 and α3) as well as the ‘housekeeping' isoform (α1). Furthermore, the α1, α3, and to a lesser extent α2, proteins were detected in this tissue and localized to the myocytes. Previous studies of cultured rat mesenteric artery myocytes detected the α1 and α3 Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms by Western blot analysis but, possibly due to cell culturing, failed to detect the α2 isoform (Juhaszova & Blaustein, 1997a). However, expression of α2 and/or α3 isoforms on the myocytes suggests that the machinery is present for the generation of smooth muscle hyperpolarizations in response to increases in extracellular K+. The work of Juhaszova & Blaustein (1997a,b) showed α1 subunits had a homogeneous distribution across the smooth muscle cell surface, whereas the α3 protein seemed to correspond to the underlying sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), in close association with the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. The same workers observed a similar pattern in neurones. They suggested that the α3-containing isozymes may act in concert with the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to control intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations in the vicinity of the SR, thereby controlling Ca2+ mobilisation, and cellular excitability. In addition Blanco & Mercer (1998) have suggested that α subunits that are less sensitive to K+ (i.e. α2 and α3) might be activated to restore ionic gradients after nerve impulses. The results of the present study suggest that the α2 and α3 isoforms may also have an important role in tempering contractile responses following agonist-induced depolarization of vascular smooth muscle.

In the presence of phenylephrine, but in the absence of iberiotoxin, K+ induced smooth muscle hyperpolarization occurs in intact but not in endothelium-denuded arteries (Richards et al., 2001; present study). This suggests that under these conditions, endothelial cells are still able to respond to elevation of K+ and to influence the smooth muscle membrane potential. We previously proposed that the phenylephrine-induced K+ cloud does not fully envelop the endothelial cells, thus allowing some response to elevation of extracellular K+ (Richards et al., 2001). To explore an alternative possibility, namely that Na+/K+-ATPase subunits with different K+ sensitivities are present on endothelial and smooth muscle cells, the distribution of the subunits was assessed using an immunohistochemical approach. Surprisingly, the α2 isoform was predominantly found in the smooth muscle and there was no essential difference between these cells with respect to the expression of the isoform (α3) which has the lowest affinity for K+ (Blanco & Mercer, 1998).

In a variety of tissues, Na+/K+-ATPase activity is enhanced by α1-adrenoceptor activation (Viko et al., 1997; Holtback & Eklof, 1999; Mallick et al., 2000), possibly by dephosphorylation of this enzyme (Mallick et al., 2000). Since the effects of phenylephrine in arteries are restricted to the myocytes (Dora et al., 1997), it is possible that the degree of activation of the ouabain-sensitive isoforms of Na+/K+-ATPase in the myocytes prior to elevation of [K+]o may have been greater than that of the same isoforms in endothelial cells. This would explain the lower sensitivity of the smooth muscle Na+/K+-ATPase to the hyperpolarizing effect of raising extracellular K+ in comparison to the endothelial cells (in which phenylephrine had not stimulated Na+/K+-ATPase).

Na+/K+-ATPase expression and activity is regulated by a variety of moieties including the cytoskeleton, endogenous inhibitors, hormones and protein kinases (for review see Therien & Blostein, 2000) and different subunit isoforms may be heterogeneously regulated. In addition to the multiple α-subunit isoforms there are also at least three isoforms of β-subunit which also show tissue-specific expression. Little is known about the endogenous dimerization of specific subunit isoforms but the opportunity for functional diversity of Na+/K+-ATPases seems to be considerable.

Conclusion

The results of the present study show that rat mesenteric artery myocytes possess α1-, α2- and α3-subunits isoforms of Na+/K+-ATPase. Furthermore, those comprising α2- or α3-subunits, which are sensitive to low concentrations of ouabain, are responsible for the hyperpolarization induced by small increases in [K+]o above the basal physiological level. We conclude that in the presence of phenylephrine, the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and depolarization of the smooth muscle stimulates K+ efflux, predominantly through BKCa. Under these conditions the accumulation of an extracellular K+ ‘cloud' could occur and prevent any further activation of α2- and/or α3-type Na+/K+-ATPases in response to elevation of extracellular K+.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation (M.P. Burnham, G. Edwards, G.R. Richards and A.H. Weston).

Abbreviations

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

References

- AICKIN C.C., BRADING A.F. Towards an estimate of chloride permeability in the smooth muscle of guinea-pig vas deferens. J. Physiol. 1983;336:179–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON D.A., ZYGMUNT P.M., MOVAHED P., ANDERSSON T.L., HÖGESTÄTT E.D. Effects of inhibitors of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, inwardly-rectifying potassium channels and Na+/K+ ATPase on EDHF relaxations in the rat hepatic artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:1490–1496. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARYSTARKHOVA E., SWEADNER K.J. Isoform-specific Monoclonal antibodies to Na,K-ATPase α Subunits. Evidence for a tissue-specific post-translational modification of the α subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23407–23417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLANCO G., MERCER R.W. Isozymes of the Na,K ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:F633–F650. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.5.F633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNHAM M.P., RICHARDS G.R., EDWARDS G., WESTON A.H. Identification and localization of Na+/K+ ATPase subunits in rat arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:82P. [Google Scholar]

- CRAMBERT G., HASLER U., BEGGAH A.T., YU C., MODYANOV N.N., HORISBERGER J.D., LELIEVRE L., GEERING K. Transport and pharmacological properties of nine different human Na, K-ATPase isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:1976–1986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DORA K.A., GARLAND C.J. Properties of smooth muscle hyperpolarization and relaxation to K+ in the rat isolated mesenteric artery. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;80:H2424–H2429. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DORA K.A., DOYLE M.P., DULING B.R. Elevation in intracellular calcium in smooth muscle causes endothelial cell generation of NO in arterioles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:6529–6534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGHTY J.M., BOYLE J.P., LANGTON P.D. Potassium does not mimic EDHF in rat mesenteric arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1174–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS G., DORA K.A., GARDENER M.J., GARLAND C.J., WESTON A.H. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature. 1998;396:269–272. doi: 10.1038/24388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS G., GARDENER M.J., FÉLÉTOU M., BRADY G., VANHOUTTE P.M., WESTON A.H. Further investigation of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) in rat hepatic artery: studies using 1-EBIO and ouabain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:1064–1070. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS G., WESTON A.H. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor – a critical appraisal. Prog. Drug Res. 1998;50:107–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8833-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FÉLÉTOU M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2000;21:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARLAND C.J., PLANE F., KEMP B.K., COCKS T.M. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization: a role in the control of vascular tone. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON T.C., WEIR S.W., WESTON A.H. Comparison of the effects of BRL 34915 and verapamil on electrical and mechanical activity in rat portal vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;88:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb09476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASLER U., WANG X., CRAMBERT G., BEGUIN P., JAISSER F., HORISBERGER J.D., GEERING K. Role of beta-subunit domains in the assembly, stable expression, intracellular routing, and functional properties of Na,K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30826–30835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLTBACK U., EKLOF A.C. Mechanism of FK 506/520 action on rat renal proximal tubular Na+, K+-ATPase activity. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1014–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUEL C., PILEGAARD H., NIELSEN J.J., BANGSBO J. Interstitial K+ in human skeletal muscle during and after dynamic graded exercise determined by microdialysis. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;278:R400–R406. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUHASZOVA M., BLAUSTEIN M.P. Na+ pump low and high ouabain affinity α-subunit isoforms are differently distributed in cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997a;94:1800–1805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUHASZOVA M., BLAUSTEIN M.P. Distinct distribution of different Na+ pump α-subunit isoforms in plasmalemma – physiological implications. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1997b;834:524–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSCHINSKY W., WAHL M. Local chemical and neurogenic regulation of cerebral vascular resistance. Physiol. Rev. 1978;58:656–689. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LACY P.S., PILKINGTON G., HANVESAKUL R., FISH R.J., BOYLE J.P., THURSTON H. Evidence against potassium as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat mesenteric small arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:605–611. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAEMMLI U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARGE W.A., WANG Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C435–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALIK B., JAMIESON G.A., BALL W.J. Identification of the amino acids comprising a surface-exposed epitope within the nucleotide-binding domain of the Na+,K+-ATPase using a random peptide library. Protein Sci. 1993;2:2103–2111. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALLICK B.N., ADYA H.V., FAISAL M. Norepinephrine-stimulated increase in Na+, K+-ATPase activity in the rat brain is mediated through alpha1A-adrenoceptor possibly by dephosphorylation of the enzyme. J. Neurochem. 2000;4:1574–1578. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCARRON J.G., HALPERN W. Potassium dilates rat cerebral arteries by two independent mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:H902–H908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLEAN I.W., NAKANE P.K. Periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde fixative. A new fixative for immunoelectron microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1974;22:1077–1083. doi: 10.1177/22.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA Y., OHYA Y., ABE I., FUJISHIMA M. Sodium-potassium pump current in smooth muscle cells from mesenteric resistance arteries of the guinea pig. J. Physiol. 1999;519:203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0203o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON M.T., QUAYLE J.M. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'BRIEN W.J., LINGREL J.B., WALLICK E.T. Ouabain binding kinetics of the rat alpha two and alpha three isoforms of the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;310:32–39. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRIOR H.M., WEBSTER N., QUINN K., BEECH D.J., YATES M.S. K+ induced dilation of a small renal artery: no role for inward rectifier K+ channels. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;37:780–790. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUINN K., GUIBERT C., BEECH D.J. Sodium-potassium-ATPase electrogenicity in cerebral precapillary arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:H351–H360. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHARDS G.R., BURNHAM M.P., EDWARDS G., FÉLÉTOU M., VANHOUTTE P.M., WESTON A.H. Suppression of K+-induced hyperpolarization by phenylephrine in rat mesenteric artery: relevance to studies of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAMRAJ O.I., LINGREL J.B. A putative fourth Na+, K+ ATPase α-subunit gene is expressed in testis. PNAS U.S.A. 1994;91:12952–12956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKINNER N.S., POWELL W.J. Action of oxygen and potassium on vascular resistance of dog skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1967;212:533–540. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR S.G., WESTON A.H. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; a new endogenous inhibitor from the vascular endothelium. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1988;9:272–274. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THERIEN A.G., BLOSTEIN R. Mechanisms of sodium pump regulation. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:C541–C566. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOWBIN H., STAEHELIN T., GORDON J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDERHILL D.A., CANFIELD V.A., DAHL J.P., GROS P., LEVENSON R. The Na,K-ATPase α4 gene (Atp1a4) encodes a ouabain-resistant α subunit and is tightly linked to the α2 gene (Atp1a2) on mouse chromosome 1. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14746–14751. doi: 10.1021/bi9916168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIKO H., OSNES J.B., SKOMEDAL T. The Na+/K+ ATPase mediates the alpha 1-adrenoceptor stimulated increase in 86Rb+-uptake in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes from adult rat heart. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1997;96:89–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]