Abstract

The activation of tachykinin NK1 receptors in the rat spinal cord produced a transient drop in arterial blood pressure followed by a more prolonged pressor effect which is mediated by the stimulation of the sympatho-adrenal system. This study aims at characterizing the spinal mechanism of that initial hypotension occurring in awake unrestrained rats.

The initial hypotension (−18±2.0 mmHg at 1 min) and the tachycardia (110±10 b.p.m.) produced by the intrathecal (i.t.) injection of the stable NK1 receptor agonist [Sar9, Met(O2)11]-SP (Sar9, 0.65 nmol) at T-9 spinal cord level was inhibited by the prior injection of 65 nmol LY306740 or LY303870 (NK1 receptor antagonists). No inhibition was seen when a similar dose of antagonists was given intravenously.

The prior i.t. injection of the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP52432 (100 nmol) reduced the hypotension evoked by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) and by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (100 nmol). The GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (25 nmol, i.t.) was without effect against Sar9, and the GABAA agonist muscimol (100 nmol, i.t.) had no cardiovascular effect.

The putative involvement of other mediators (dopamine, serotonine, glycine and glutamate) in Sar9-induced hypotension was made unlikely on the basis of various pharmacological treatments. Thus data, suggest that the transient hypotension which occurs upon the activation of NK1 receptors in the spinal cord is due to the release of GABA which in turn activates GABAB receptors to inhibit sympathetic pre-ganglionic fibres. This mechanism may have a physiological significance in the spinal reflex autonomic control of arterial blood pressure.

Keywords: Substance P, NK1 receptor, GABA, spinal cord, autonomic reflex, blood pressure

Introduction

Compelling evidence suggests that substance P (SP) is involved in autonomic cardiovascular regulation in the spinal cord (Couture et al., 1995). The intrathecal (i.t.) injection of SP at T-9 spinal cord level increases mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) through the activation of the sympatho-adrenal system and the peripheral release of catecholamines both in urethane-anaesthetized rats (Keeler et al., 1985; Yashpal et al., 1985; Couture et al., 1988) and in awake, freely moving rats (Hasséssian & Couture, 1989; Hasséssian et al., 1990). This spinal action of SP on the rat cardiovascular system is mediated by NK1 receptors (Hasséssian et al., 1988; Couture et al., 1995). A majority of sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons (SPNs) in the intermediolateral cell column (IML) projecting to the adrenal medulla are NK1 receptor immunoreactive (Helke et al., 1986; Grkovic & Anderson, 1996; Llewellyn-Smith et al., 1997; Pollock et al., 1997; Burman et al., 2001). SPNs could be modulated by bulbospinal SP-containing neurons which originate in the ventral medulla but also by intraspinal and primary sensory C-fibres which can release SP in the vicinity of SPNs (for reviews see Helke et al., 1985; Couture et al., 1995). Ultrastructural studies in the IML of rat lower thoracic spinal cord suggest that SP modulates the activity of SPNs which have NK1 receptors on their dendrites and cell bodies through direct synaptic and indirect non-synaptic mechanisms (Llewellyn-Smith et al., 1997; Pollock et al., 1997). A transient hypotension is however observed prior to the pressor response in both pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats (Couture et al., 1988; Solomon et al., 1999) and in awake, freely moving rats (Hasséssian et al., 1990). The spinal mechanism underlying this hypotension remains unknown and may involve a spinal reflex pathway.

Much evidence suggests that γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) regulates SPNs at the level of the IML in the spinal cord. A significant population of axon terminals which synapse onto SPNs in the IML are GABA immunoreactive (Bacon & Smith, 1988; Bogan et al., 1989; Chiba & Semba, 1991; Cabot et al., 1995; Ligorio et al., 2000) and 32–37% of the sympatho-adrenal neurones have synaptic contacts with GABA-immunoreactive fibres (Bacon & Smith, 1988). The GABAergic input to the SPNs could arise from rostral and caudal ventrolateral medulla and spinal inhibitory interneurons (Magoul et al., 1987; Miura et al., 1994; Lewis & Coote, 1995). Electrophysiological evidence suggests that GABA decreases MAP and/or HR by hyperpolarizing SPNs and inhibiting their discharge activity (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1982; Backman & Henry, 1983; Hasséssian et al., 1991; Inokuchi et al., 1992; Wu & Dun, 1992; Lewis & Coote, 1995).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that SP could release GABA from spinal dorsal horn interneurons to buffer the vasopressor response induced by SP in the spinal cord. Selective GABAA and GABAB antagonists (bicuculline and CGP52432, respectively) were employed to inhibit the transient hypotension induced by i.t. injection of the selective and metabolically protected NK1 receptor agonist [Sar9, Met(O2)11]-SP (Drapeau et al., 1987). Other treatments were also tested in parallel studies to rule out the involvement of other putative neurotransmitters such as dopamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), glutamate and glycine in the initial hypotension induced by the NK1 receptor agonist. Since the i.t. injection of SP elicits different cardiovascular responses in urethane and pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats (Couture et al., 1988), these studies were performed in awake freely moving rats.

Methods

Animal source and care

Male Wistar rats (250–275 g) were purchased 2–3 days prior to the experiments from Charles River, St-Constant, Québec, Canada, and housed individually in plastic cages under a 12 h light-dark cycle in a room with controlled temperature (20°C), humidity (53%) with food (Charles River Rodent) and tap water available ad libitum. The care of animals and research protocols conformed to the guiding principles for animal experimentation as enunciated by the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Animal Care Committee of our University.

Animal preparation

Rats (n=235) were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 65 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone (Somnotol; M.T.C. Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, Ontario, Canada) and a polyethylene catheter (PE-10) siliconized (Intramedics, Clay Adams, NJ, U.S.A.) was inserted into the spinal subarachnoid space through an incision made in the dura at the atlanto-occipital junction and pushed to the 9th thoracic segment (T-9) as described previously (Couture et al., 1995). This segment was chosen because it contains the larger population of SPNs projecting to the adrenal medulla (Llewellyn-Smith et al., 1997). Thereafter, the surgical incisions were sutured and the rats were allowed to recover in individual plastic cages (40×23×20 cm) and housed in the same controlled conditions. Twelve per cent (12%) of rats were excluded from the study because they presented motor deficit such as partial paralysis of one posterior or anterior limb. These rats were immediately sacrificed with an overdose of pentobarbitone. The correct position of the intrathecal (i.t.) catheter was verified by post-mortem examination at the end of experiment and the catheter was found either dorsally or laterally to the spinal cord.

Three days later, rats were re-anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (65 mg kg−1, i.p.) and an intra-arterial (i.a.) siliconized (Sigmacote, Sigma, St-Louis, MO, U.S.A.) PE-50 catheter, filled with physiological saline containing 100 IU ml−1 heparin sodium salt (Sigma, St-Louis, MO, U.S.A.), was inserted into the abdominal aorta through the femoral artery for direct blood pressure recording and exteriorized at the back of the neck. In a group of 14 rats, an additional catheter (PE-50), filled with physiological saline containing 100 IU ml−1 heparin, was inserted into one jugular vein to allow i.v. injections of LY303870 and LY306740. Recovery from anaesthesia was monitored closely under a warming lamp to maintain the body temperature of animals. Thereafter, rats were housed individually in polyethylene cages with a top grid and returned to their resident room. Before intrathecal and vascular surgery, the animals received Ethacilin (5 mg kg−1, i.m., rogar/S.T.B. Inc., London, Ontario, Canada) as antibiotic and Ketoprophen (anafen, 10 mg kg−1, i.m., Merial Canada Inc., Baie d'Urfé, Québec, Canada) as analgesic. Experimental protocols were initiated 24–49 h after vascular surgery, in awake and unrestrained rats. A period of 24 h is sufficient for rats to recover after surgery and pentobarbitone anaesthesia as evidenced by the low plasma levels of catecholamines measured after arterial cannulation (Chiueh & Kopin, 1978).

Measurement of cardiovascular parameters

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured respectively with a Statham pressure Transducer (P23ID) and a cardiac tachometer (model 7P4) (triggered by the arterial blood pressure pulse) coupled to a Grass polygraph (model 79; Grass Instruments Co., Quincy, MA, U.S.A.). The cardiovascular response was measured 1 h after the rats were transported to the testing room. They remained in their resident cage but the top grid was removed and they had no more access to the food and water for the duration of each assay which lasted less than 5 h. When resting blood pressure and heart rate were stable, rats received an i.t. injection of 20 μl artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). Only rats (97%) which did not show cardiovascular changes to aCSF for a 30 min period were selected in the study. Peptides were administered in a volume of 10 μl of vehicle followed by 10 μl volume of aCSF, which corresponds to the void volume of the catheter, to flush the i.t. catheter. Each dose was calculated per rat in 10 μl solution. Vehicle for each compound was tested as control in the same rats.

Experimental protocols

Intrathecal injections of agonists and antagonists

Dose-response curves were constructed using increasing doses of Sar9. Rats (n=8) initially received an i.t. injection of aCSF (10 μl) followed 30 min later by three increasing doses of Sar9 (0.065; 0.65; 6.5 nmol). The time interval between each injection was 60 min.

To determine the mechanism and receptor through which Sar9 produced its vasodepressor response, Sar9 was injected before and after the i.t. administration of one of the following antagonists: LY303870 (65 nmol, n=6) and LY306740 (65 nmol, n=6) (two NK1 receptor antagonists), LY306155 (65 nmol, n=6; inactive (S) enantiomer of LY303870), CGP52432 (100 nmol, n=6; GABAB receptor antagonist), bicuculline (25 nmol, n=6; GABAA receptor antagonist), MK-801 (0.1 and 1 μmol, n=4; NMDA receptor antagonist). Fluoxetine (1.1 μmol, n=4) was used to selectively inhibit the uptake of serotonin (Hwang & Wilcox, 1987). In preliminary experiments, Sar9 was injected at different times following the injection of various doses of these antagonists but only the procedure that caused the most effective inhibition is shown. Antagonists were also tested alone to determine whether they produce a direct cardiovascular effect when injected at T-9. Similarly, various agonists were tested to assess their effect in this paradigm: muscimol (100 nmol, n=6; GABAA receptor agonist), baclofen (100 nmol, n=6; GABAB receptor agonist), quinpirole (23 and 235 nmol, n=4; dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonist), SKF-38393 (10, 100, 300 and 1000 nmol, n=4; dopamine D1 receptor agonist) and 5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT) (0.65 nmol, n=6; 5-HT1A, 1B, 1D receptor agonist). Since a biological effect was obtained with baclofen, a specific antagonist to the GABAB receptor was assessed against the effect of the agonist. Only one antagonist was injected into each rat.

pCPA treatment

The pCPA treatment used in this study was shown to prevent selectively the synthesis of 5-HT in the rat spinal cord (Hasséssian et al., 1993). A group of 12 rats received a solution of p-chlorophenylalanine methyl ester HCl prepared in physiological saline. The compound was injected i.p. at 300 mg kg−1 day−1 during a 48-h treatment. These rats also received 25 mg kg−1 of desipramine HCl 45 min prior to each pCPA injection to prevent non-specific uptake of pCPA into adrenergic neurons by blocking the catecholamine uptake mechanism. The i.t. and i.a. catheters were implanted as previously described 48 h before. The cardiovascular effect of Sar9 (0.65 nmol) was measured 24 h before pCPA and 48 h after the last injection of pCPA.

Drugs and solutions

The composition of aCSF (artificial cerebrospinal fluid) was (in mM): NaCl 128.6, KCl 2.6, MgCl2 2.0 and CaCl2 1.4; pH adjusted to 7.2. [Sar9, Met(O2)11]-Substance P (MW: 1393.7) was purchased from Bachem Bioscience Inc. (King of Prussia, PA, U.S.A.) whereas CGP52432 2H2O (MW: 420.26) was purchased from Tocris Cookson Inc. (Ballwin, MO, U.S.A.). The non-peptide tachykinin antagonists LY306740 2HCl (MW: 632.6), LY303870 2HCl (MW: 686.73) and the opposite (S) enantiomer LY306155 (MW: 559.8) of LY303870 were obtained from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) (Hipskind et al., 1996). The last three drugs were diluted in aCSF containing 20% dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO; Fisher, Montréal, Qué., Canada). All the other compounds were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); (−)-bicuculline methiodide (MW: 509.3), muscimol HBr (MW: 195.02), R(+)-baclofen HCl (MW:250.1), DL-p-chlorophenylalanine methyl ester HCl, (MW: 250.1), desipramine HCl (MW: 302.8), fluoxetine HCl (MW: 345.79), (+)-MK-801 hydrogen maleate (MW: 337:37), (−)-quinpirole HCl (MW: 255.79), S(−)-SKF-38393 HCl (MW: 291.8), 5-carboxamidotryptamine maleate (MW: 319.32). All the agonists and antagonists, except LY303870, LY306155 and LY306740, were prepared in aCSF exclusively. The stock solutions of agonists and antagonists were stored in aliquots of 100 μl at −20°C until use.

Statistical analysis of data

Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean. Statistical comparison of maximal cardiovascular effects before and after receptor blockade was made with a Student's t-test for paired samples. Multiple comparisons (time course effects) were analysed with a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in conjunction with Bonferroni confidence intervals. Only probability values (P) less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Spinal effect of Sar9 on the cardiovascular system

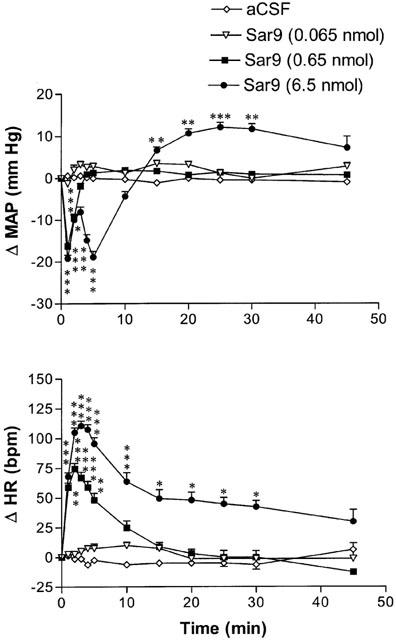

The effects of three increasing doses of Sar9 on MAP and HR are shown in Figure 1. Whereas the lowest dose (0.065 nmol) of Sar9 failed to alter MAP and HR when compared to aCSF values, Sar9 (0.65 and 6.5 nmol) evoked dose-related hypotension and tachycardia that peaked at 1 and 2 min post-injection, respectively. The vasodepressor response was succeeded by a sustained pressor effect at the highest dose. MAP and HR returned to pre-injection levels by 45 min when 6.5 nmol Sar9 was injected. The cardiovascular response to Sar9 was accompanied by episodes of scratching behaviour that lasted for a period of 3–6 min post-injection. The vasopressor response to Sar9 was not investigated further.

Figure 1.

Time-course effects on changes in mean arterial blood pressure (Δ MAP) and heart rate (Δ HR) for a period of 45 min following the intrathecal injection of three increasing doses of Sar9 at T-9 spinal cord level in awake unrestrained rats. Each point represents the means±s.e.mean of eight rats. Baseline MAP and HR values are 90.6±4.3 mmHg and 418±11 b.p.m., respectively. Statistical comparison to vehicle values (aCSF) is indicated by *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

NK1 receptor antagonists block the spinal effect of Sar9

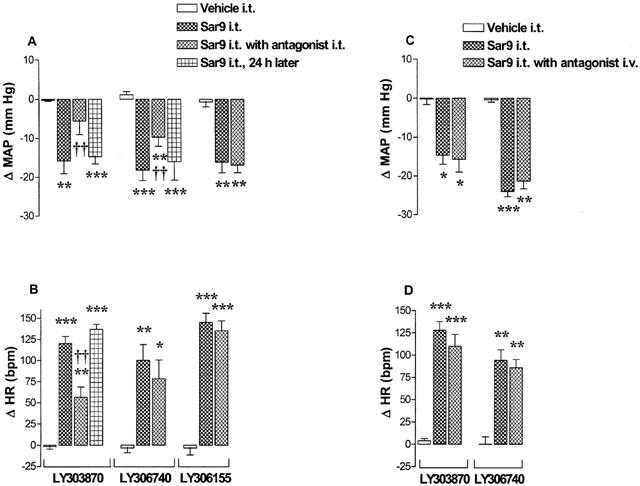

The MAP and HR responses evoked by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) were significantly reduced by the prior i.t. injection of LY303870 (65 nmol, 15 min earlier) (Figure 2A,B). Although 65 nmol LY306740 reduced significantly the MAP response, it had no significant effect on the increase of HR elicited by Sar9. The cardiovascular response to Sar9 was completely back to pre-antagonist values when the agonist was re-injected alone 24 h after either antagonist (Figure 2A,B). In contrast, the (S) enantiomer of LY303870 namely LY306155 (65 nmol) was without effect on the cardiovascular response induced by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) (Figure 2A,B). As control, i.v. pre-administration (15 min earlier) of LY303870 (65 nmol) or LY306740 (65 nmol) had no effect on the cardiovascular response to Sar9 (Figure 2C,D). However, the prior i.v. injection (15 min earlier) of a higher dose of LY306740 (3.5 μmol kg−1, n=4), which is able to cross the blood-brain barrier, blunted the cardiovascular effects produced by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) (maximal changes in MAP and HR were respectively reduced from −17.9±2.8 to −4.8±1.4 mmHg and from 99±17 to 40±15 b.p.m.; P<0.001). Both NK1 antagonists failed to produce direct effects on MAP and HR or apparent motor deficit and they prevented the scratching behaviour elicited by the NK1 agonist (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Maximal changes in mean arterial blood pressure (Δ MAP) and heart rate (Δ HR) induced by 0.65 nmol Sar9 injected to T-9 spinal cord level of awake rats in the absence (prior to and 24 h later) and presence (15 min after) of 65 nmol of LY303870, LY306740 or LY306155 administered either i.t. (A–B) or i.v. (C–D). Data are means±s.e.means of six rats per antagonist. Statistical comparison to vehicle (aCSF/20% DMSO) values (*) or to Sar9 without antagonist (†) is indicated by *P<0.05; **, ††P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Baseline values are for MAP and HR: 103.6±8.3 mmHg and 371.7±14.0 b.p.m. (LY303870); 83.9±5.1 mmHg and 416.7±13.3 b.p.m. (LY306740); 104.7±8.6 mmHg and 373.3±17.8 b.p.m. (LY306155).

Spinal effect of GABA agonists and antagonists

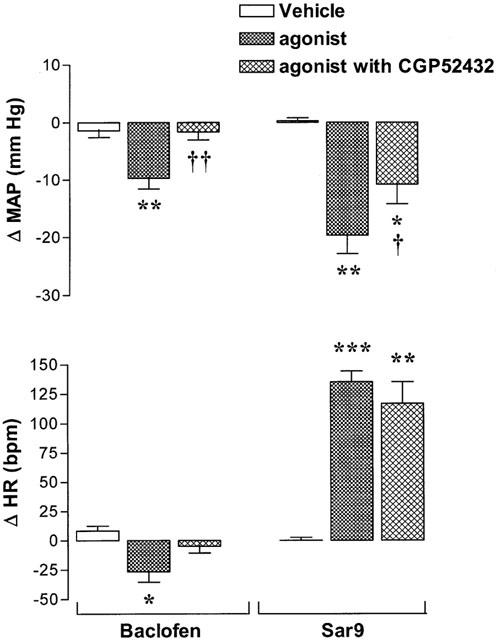

The effect of 100 nmol baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist, on MAP and HR is shown in Figure 3. The i.t. injection of baclofen evoked a transient decrease in MAP and HR that peaked at 5 min and 2 min post-injection, respectively. This response was completely blocked by i.t. pre-injection (1 min earlier) of 100 nmol CGP52432, a selective GABAB receptor antagonist which was devoid of any direct cardiovascular or behavioural effects. The cardiovascular response to baclofen was entirely back to pre-antagonist values when the agonist was re-injected alone 24 h later (data not shown). The MAP response evoked by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) was significantly reduced by the prior i.t. injection of CGP52432 (100 nmol, 1 min earlier) while the increase of HR was not significantly altered (Figure 3). However, the same treatment with CGP52432 (100 nmol) was without effect on the cardiovascular response elicited by 0.65 nmol 5-carboxamidotryptamine (maximal changes in MAP and HR: before, −20.8±1.8 mmHg and 120±9 b.p.m.; after, −23.3±2.0 mmHg and 117±11 b.p.m., n=6).

Figure 3.

Maximal changes in mean arterial blood pressure (Δ MAP) and heart rate (Δ HR) induced by i.t. injection of 100 nmol baclofen or 0.65 nmol Sar9 injected prior to or 1 min after i.t. administration of 100 nmol CGP52432. Data are means±s.e.means of six rats. Statistical comparison to vehicle values (*) or to agonists without CGP52432 (†) is indicated by *, †P<0.05; **, ††P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

In contrast, 100 nmol muscimol, a GABAA receptor agonist, did not cause any significant changes on MAP and HR (maximal changes in MAP and HR are 0.3±1.3 mmHg and 5±6 b.p.m., respectively; n=6) or on behavioural activity. Also, bicuculline (25 nmol), a GABAA receptor antagonist, was without effect on the cardiovascular response induced by Sar9 (maximal changes in MAP and HR: before, −14.3±3.4 mmHg and 92±11 b.p.m.; after, −14.7±3.2 mmHg and 100±6 b.p.m., n=5). Although bicuculline (25 nmol) had no direct effects on resting MAP and HR or on behavioural activity, a higher dose of bicuculline (100 nmol) caused a marked aversive reaction in rats (vocalization, scratching and running activity in the cage) which precluded its testing against Sar9. Doses larger than 100 nmol muscimol were not tested because they were poorly soluble in a physiological medium to enable their i.t. administration.

Other treatments

The i.t. administration of SKF-38393 (10, 100, 300 nmol and 1 μmol) and quinpirole (23 and 234 nmol), dopamine D1 and D2/D3 receptor agonist, respectively had no effect on MAP and HR (Table 1, shown are data measured with the highest dose of either agonist). Pre-injection (i.t. 15 min earlier) of fluoxetine (1.1 μmol), which selectively inhibits the uptake of 5-HT, was without effect on the cardiovascular response induced by Sar9 (0.65 nmol). A 48 h treatment with pCPA, which depletes 5-HT containing neurons in the spinal cord, potentiated the Sar9-induced MAP response (P<0.05), yet the HR response was not affected. The i.t. pre-administration (5 min earlier) of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (0.1 or 1 μmol) failed to alter both the MAP and HR responses evoked by Sar9 (0.65 nmol) (Table 1, shown are data measured with the highest dose of antagonist). None of these drugs elicited changes of behavioural activity at the doses tested.

Table 1.

Maximal changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) and heart rate (ΔHR) induced by various treatments

Discussion

This study confirms previous findings showing that SP and NK1 receptor agonists injected intrathecally to T-9 spinal cord level increase both MAP and HR in awake, freely moving rats at doses equal or higher than 6.5 nmol (Hasséssian et al., 1988; 1990; Hasséssian & Couture, 1989). This spinal action of SP was attributed to the activation of SPNs in the IML which trigger the release of catecholamines from the adrenal medulla and sympathetic fibres (Keeler et al., 1985; Yashpal et al., 1985; Hasséssian et al., 1990). This is congruent with studies showing an excitation of SPNs upon iontophoretic application of SP into the IML of rats and cats (Gilbey et al., 1983; Backman & Henry, 1984). Ultrastructural studies suggest that SP may modulate the activity of SPNs which have NK1 receptor on their dendrites and perikarya through direct synaptic and indirect non-synaptic mechanisms (Llewellyn-Smith et al., 1997; Pollock et al., 1997).

However, an in vitro electrophysiological study on rat spinal cord slices also reported a population of SPNs initially hyperpolarized prior to depolarization following the direct application of SP to the membrane of SPNs. In addition, SP induced the occurrence of repetitive inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (IPSPs) in about 20% SPNs. Both the hyperpolarizing phase of the biphasic response and the IPSPs were blocked by tetrodotoxin and therefore they were ascribed to the activation by SP of inhibitory interneurons (Dun & Mo, 1988). This is consistent with the initial hypotension occurring prior to the pressor response of SP or Sar9 in anaesthetized and non-anaesthetized rats (Hasséssian et al., 1990; Solomon et al., 1999). A previous pharmacological study failed to elucidate the spinal mechanism underlying this hypotension which was markedly enhanced in pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats (Couture et al., 1988). In the latter study, it was concluded that the SP-induced hypotension was unlikely due to the release of a known vasodilatatory substance in systemic circulation since it persisted after inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis or after intravenous administration of cholinergic, histaminergic, serotonergic, adrenergic or opioid antagonists.

LY303870 blocked in a stereospecific manner the hypotension and tachycardia evoked by i.t. injection of Sar9, suggesting that both responses are dependent of NK1 receptor activation. The smaller efficacy of LY306740 to block the cardiovascular response evoked by Sar9 is reminiscent of its lower potency in the rat brain (Cellier et al., 1999). Nevertheless, the prior i.v. injection of a higher dose of LY306740, which is able to cross the blood-brain barrier, completely blocked the cardiovascular response induced by Sar9. Taken together these data support the earlier conclusion that the NK1 receptor mediates the cardiovascular effect of tachykinins in the rat spinal cord (Hasséssian et al., 1988; Couture et al., 1995).

The possibility that Sar9 diffuses into the systemic blood circulation to exert its action on the cardiovascular system is unlikely since LY303870 and LY306740 injected i.v. at the dose which was effective intrathecally did not modify the cardiovascular response induced by i.t. Sar9. Another study also reported that from 1 to 16 min after i.t. administration of [125I]-SP, the venous blood samples contain only 0.8–3.5% of the total labelled peptide injected and that the rostro-caudal diffusion is restricted to 0.5 cm from the site of injection (Cridland et al., 1987). Thus, these observations suggest that the amount of SP detected in systemic circulation after i.t. injection cannot account for the response observed, and consequently, the biphasic MAP response evoked by Sar9 is most likely mediated by a direct effect in the spinal cord. Moreover, this cardiovascular response is unlikely associated to a spinothalamic nociceptive pathway because the pressor response to SP is not altered by i.v. or i.t. injection of an analgesic dose of morphine or by transection of the cervical spinal cord (Hasséssian & Couture, 1989). However, one cannot exclude the possibility that the activation of NK1 receptor located on inhibitory interneurons of the dorsal horn, that are likely more accessible to intrathecally injected drugs, could cause the inhibition of SPNs as supported by electrophysiological evidence (Dun & Mo, 1988). On the basis of our data, GABA may represent the putative neurotransmitter of these inhibitory interneurons activated by SP or an NK1 agonist.

GABAergic component in the hypotension induced by [Sar9, Met(O2)11]-SP

GABA is a neurotransmitter found in bulbospinal neurons projecting directly to the IML and in spinal interneurons originating from the dorsal horn that can inhibit the activity of SPNs (Introduction). Its effects on synaptic transmission are mediated by GABAA, GABAB and GABAC receptors (Hill & Bowery, 1981; Bormann & Feigenspan, 1995; Schmidt et al., 2001). The activation of the ionotropic GABAA and GABAC receptors induces a rapid inhibition of neurons by allowing the influx of Cl− that causes an hyperpolarization of the post-synaptic membrane. In contrast, the metabotropic GABAB receptors exert a slower, more prolonged inhibition on pre- and post-synaptic neurons by modulating adenylyl cyclase activity which causes an inwardly rectifying K+ channels to open and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to close (Bowery, 1989; Kerr & Ong, 1995; Johnston, 1996; Bettler et al., 1998).

The hypotension and the bradycardia elicited by the i.t. injection of the GABAB agonist baclofen are in agreement with previous studies in anaesthetized and non-anaesthetized rats (Hasséssian et al., 1991; Hong & Henry, 1991a, b). The dose of 100 nmol baclofen (T-9 spinal level) was found to inhibit plasma adrenaline (but not noradrenaline) and to depress the vasopressor response to SP, supporting the hypothesis that GABAB receptor agonists are able to inhibit SPNs projecting to the adrenal medulla (Hasséssian et al., 1991). This is in agreement with the finding that the SP-induced vasodepressor effect is more striking in sympathectomized rats and virtually absent 48 h after bilateral adrenalectomy (Hasséssian et al., 1990). The inhibitory effect of CGP52432 on the cardiovascular response induced by baclofen and Sar9 was specific since this blocker was ineffective against 5-carboxamidotryptamine. Therefore, the data suggest that the transient hypotension induced by the NK1 receptor agonist is mediated, at least partly, by endogenous release of GABA and the subsequent activation of GABAB receptor. This possibility is supported by morphological evidence that GABA and SP receptors are co-localized in dendrites in the superficial laminae of the rat dorsal horn (Tao et al., 2000).

The lack of effect of muscimol and the inability of bicuculline (GABAA receptor antagonist) to inhibit the response of Sar9 exclude a primary participation of GABAA receptor. Because GABAC receptors have a higher affinity for muscimol than do GABAA receptors (Bormann & Feigenspan, 1995; Johnston, 1996; Schmidt et al., 2001), it is also unlikely that GABAC receptors are involved in the response to Sar9. So far, there is no indication that GABAC receptors are expressed in the rat spinal cord. Although one cannot exclude the possibility that these drugs did not reach the IML in effective concentration, muscimol (0.5–50 nmol) antagonized the pressor response to SP (16.25 nmol) in a dose-related manner as baclofen did in the same animal model (Hasséssian et al., 1991). The data also suggest that it is unlikely that NK1 and both GABA receptors exert a tonic influence onto cardiovascular SPNs as intrathecal injection of antagonists at these receptors had no direct effect on MAP or HR. In a previous study, however, phaclofen (GABAB receptor antagonist) produced a rise in MAP and HR at 10 μmol but not at doses up to 2 μmol (Hasséssian et al., 1991). In the present study, CGP52432 was used at a lower dose (100 nmol) which should rule out non-specific effects that may be accounted with large doses of a less specific drug such as phaclofen.

Lack of evidence for the involvement of Dopamine, 5-HT, glutamate and glycine in the hypotension induced by [Sar9, Met(O2)11]-SP

Several other treatments were used to examine the putative involvement of other neurotransmitters in the spinal vasodepressor response induced by Sar9. Whereas intrathecally injected dopamine D1 and D2/D3 receptor agonists induced an hypotension similar to Sar9 in pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats (Pellissier & Demenge, 1991; Lahlou, 1998), these receptors are probably not involved in the hypotension induced by Sar9 since selective agonists at these receptors were without spinal cardiovascular effect in awake rats. The failure to see any responses with dopamine receptor agonists in the present study may be due to the experimental conditions (awake rats versus anaesthetized animals) or more likely to the site of injection in the spinal cord as the upper thoracic level was described as the main site of action of these drugs (Pellissier & Demenge, 1991).

Because 5-CT induced a hypotension by activating 5-HT1-like receptors in the rat spinal cord (Hasséssian et al., 1993), we used fluoxetine to block the reuptake of 5-HT and pCPA to inhibit the 5-HT synthesis in the spinal cord. Since either treatment failed to reduce the hypotension induced by Sar9, the participation of 5-HT in the latter response was made unlikely.

Whereas SP enhances release of endogenous glutamate from the rat spinal cord (Kangrga & Randic, 1990), the prior i.t. injection of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 failed to alter the hypotension induced by Sar9. Thus, we conclude that the NMDA receptor is not associated with the vasodepressor response of the NK1 agonist. Since an NMDA receptor antagonist blocked the facilitation of the tail-flick reflex (hyperalgesia) induced by intrathecal SP or by noxious cutaneous stimulation (Yashpal et al., 1991), it is concluded that the spinal nociceptive and cardiovascular responses induced by SP are mediated by distinct mechanisms.

In an in vitro electrophysiological study, the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine blocked the hyperpolarization and IPSPs induced by SP in a few SPNs (Dun & Mo, 1988). In the awake rat, however, the i.t. injection of strychnine could not be assessed because its striking motor and convulsive effects interfered with the recording of blood pressure. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that glycine participates to the cardiovascular response of Sar9 since in parallel experiments, we found that strychnine had no effect on the cardiovascular response induced by Sar9 in pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats (data not shown). Furthermore, intrathecal glycine did not affect, unlike baclofen, the cardiovascular response elicited by SP in conscious rats (Hasséssian et al., 1991).

Conclusion

Several putative mechanisms involved in the transient hypotension induced by the spinal activation of NK1 receptor were studied in awake freely moving rats. Pharmacological evidence suggests that dopamine, 5-HT, glutamate NMDA receptor and glycine are unlikely to play a primary role while the release of GABA and the subsequent activation of GABAB receptor appear to occur after activation of the NK1 receptor in the spinal cord. This mechanism may be of physiological significance in the spinal reflex control of arterial blood pressure by providing a way to limit excessive excitation of sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons by SP under noxious stimulation of primary sensory nociceptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-14379) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada to R Couture.

Abbreviations

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- 5-CT

5-carboxamidotryptamine

- HR

heart rate

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- IML

intermediolateral cell column

- i.t.

intrathecal

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- pCPA

para-chlorophenylalanine

- SP

substance P

- Sar9

[Sar9, Met(O2)11]-Substance P

- SPNs

sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons

References

- BACKMAN S.B., HENRY J.L. Effects of GABA and glycine on sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the upper thoracic intermediolateral nucleus of the cat. Brain Res. 1983;277:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACKMAN S.B., HENRY J.L. Effects of substance P and thyrotropin-releasing hormone on sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the upper thoracic intermediolateral nucleus of the cat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1984;62:248–251. doi: 10.1139/y84-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACON S.J., SMITH A.D. Preganglionic sympathetic neurons innervating the rat adrenal medulla: immunocytochemical evidence of synaptic input from nerve terminals containing substance P, GABA or 5-hydroxytryptamine. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1988;24:97–122. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BETTLER B., KAUPMANN K., BOWERY N. GABAB receptors: drugs meet clones. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998;8:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOGAN N., MENNONE A., CABOT J.B. Light microscopic and ultrastructural localization of GABA-like immunoreactive input to retrogradely labeled sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Brain Res. 1989;505:257–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORMANN J., FEIGENSPAN A. GABAC receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98370-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWERY N. GABAB receptors and their significance in mammalian pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989;10:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURMAN K.J., MCKITRICK D.J., MINSON J.B., WEST A., ARNOLDA L.F., LLEWELLYN-SMITH I.J. Neurokinin-1 receptor immunoreactivity in hypotension sensitive sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Brain Res. 2001;915:238–243. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02907-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABOT J.B., BUSHNELL A., ALESSI V., MENDELL N.R. Postsynaptic gephyrin immunoreactivity exhibits a nearly one-to-one correspondence with gamma-aminobutyric acid-like immunogold-labeled synaptic inputs to sympathetic preganglionic neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;356:418–432. doi: 10.1002/cne.903560309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CELLIER E., BARBOT L., IYENGAR S., COUTURE R. Characterization of central and peripheral effects of septide with the use of five tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonists in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIBA T., SEMBA R. Immuno-electronmicroscopic studies on the gamma-aminobutyric acid and glycine receptor in the intermediolateral nucleus of the thoracic spinal cord of rats and guinea pigs. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1991;36:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(91)90041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIUEH C.C., KOPIN I.J. Hyperresponsivity of spontaneously hypertensive rat to indirect measurement of blood pressure. Am. J. Physiol. 1978;234:H690–H695. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.6.H690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTURE R., HASSÉSSIAN H., GUPTA A. Studies on the cardiovascular effects produced by the spinal action of substance P in the rat. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1988;11:270–283. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTURE R., PICARD P., POULAT P., PRAT A. Characterization of the tachykinin receptors involved in spinal and supraspinal cardiovascular regulation. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995;73:892–902. doi: 10.1139/y95-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRIDLAND R.A., YASHPAL K., ROMITA V.V., GAUTHIER S., HENRY J.L. Distribution of label after intrathecal administration of 125I-substance P in the rat. Peptides. 1987;8:213–221. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAPEAU G., D'ORLÉANS-JUSTE P., DION S., RHALEB N.E., ROUISSI N.E., REGOLI D. Selective agonists for substance P and neurokinin receptors. Neuropeptides. 1987;10:43–54. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(87)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUN N.J., MO N. In vitro effects of substance P on neonatal rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones. J. Physiol. 1988;399:321–333. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILBEY M.P., MCKENNA K.E., SCHRAMM L.P. Effects of substance P on sympathetic preganglionic neurones. Neurosci. Lett. 1983;41:157–159. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRKOVIC I., ANDERSON C.R. Distribution of immunoreactivity for the NK1 receptor on different subpopulations of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;374:376–386. doi: 10.1002/cne.903740303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H., COUTURE R. Cardiovascular responses induced by intrathecal substance P in the conscious freely moving rat. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1989;13:594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H., COUTURE R., DE CHAMPLAIN J. Sympathoadrenal mechanisms underlying cardiovascular responses to intrathecal substance P in conscious rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1990;15:736–744. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H., DRAPEAU G., COUTURE R. Spinal action of neurokinins producing cardiovascular responses in the conscious freely moving rat: evidence for a NK1 receptor mechanism. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;338:649–654. doi: 10.1007/BF00165629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H., POULAT P., HAMEL E., READER T.A., COUTURE R. Spinal cord serotonin receptors in cardiovascular regulation and potentiation of the pressor response to intrathecal substance P after serotonin depletion. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1993;71:453–464. doi: 10.1139/y93-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H., PRAT A, DE CHAMPLAIN J., COUTURE R. Regulation of cardiovascular sympathetic neurons by substance P and gamma-aminobutyric acid in the rat spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;202:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90252-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELKE C.J., CHARLTON C.G., KEELER J.R. Bulbospinal substance P and sympathetic regulation of the cardiovascular system: a review. Peptides. 1985;6 Suppl. 2:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(85)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELKE C.J., CHARLTON C.G., WILEY R.G. Studies on the cellular localization of spinal cord substance P receptors. Neuroscience. 1986;19:523–533. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL D.R., BOWERY N.G. 3H-baclofen and 3H-GABA bind to bicuculline-insensitive GABAB sites in rat brain. Nature. 1981;290:149–152. doi: 10.1038/290149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIPSKIND P.A., HOWBERT J.J., BRUNS R.F., CHO S.S., CROWELL T.A., FOREMAN M.M., GEHLERT D.R., IYENGAR S., JOHNSON K.W., KRUSHINSKI J.H., LI D.L., LOBB K.L., MASON N.R., MUEHL B.S., NIXON J.A., PHEBUS L.A., REGOLI D., SIMMONS R.M., THRELKELD P.G., WATERS D.C., GITTER B.D. 3-Aryl-1,2-diacetamidopropane derivatives as novel and potent NK1 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:736–748. doi: 10.1021/jm950616c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONG Y., HENRY J.L. Cardiovascular responses to intrathecal administration of L- and D-baclofen in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991a;192:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONG Y., HENRY J.L. Effects of phaclofen and the enantiomers of baclofen on cardiovascular responses to intrathecal administration of L- and D-baclofen in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991b;196:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90439-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HWANG A.S., WILCOX G.L. Analgesic properties of intrathecally administered heterocyclic antidepressants. Pain. 1987;28:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INOKUCHI H., YOSHIMURA M., TRZEBSKI A., POLOSA C., NISHI S. Fast inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and responses to inhibitory amino acids of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the adult cat. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1992;41:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTON G.A.R. GABAC receptors: relatively simple transmitter-gated ion channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANGRGA I., RANDIC M. Tachykinin and calcitonin gene-related peptide enhance release of endogenous glutamate and aspartate from the rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:2026–2038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-02026.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEELER J.R., CHARLTON C.G., HELKE C.J. Cardiovascular effects of spinal cord substance P: studies with a stable receptor agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;233:755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERR D.I.B., ONG J. GABAB receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;67:187–246. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00016-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAHLOU S. Involvement of spinal dopamine receptors in mediation of the hypotensive and bradycardic effects of systemic quinpirole in anaesthetised rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;353:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS D.I., COOTE J.H. Chemical mediators of spinal inhibition of rat sympathetic neurones on stimulation in the nucleus tractus solitarii. J. Physiol. 1995;486:483–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIGORIO M.A., AKMENTIN W., GALLERY F., CABOT J.B. Ultrastructural localization of the binding fragment of tetanus toxin in putative gamma-aminobutyric acidergic terminals in the intermediolateral cell column: a potential basis for sympathetic dysfunction in generalized tetanus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;419:471–484. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000417)419:4<471::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLEWELLYN-SMITH I.J., MARTIN C.L., MINSON J.B., PILOWSKY P.M., ARNOLDA L.F., BASBAUM A.I., CHALMERS J.P. Neurokinin-1 receptor-immunoreactive sympathetic preganglionic neurons: target specificity and ultrastructure. Neuroscience. 1997;77:1137–1149. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGOUL R., ONTENIENTE B., GEFFARD M., CALAS A. Anatomical distribution and ultrastructural organization of the GABA ergic system in the rat spinal cord: an immunocytochemical study using anti-GABA antibodies. Neuroscience. 1987;20:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIURA M., TAKAYAMA K., OKADA J. Distribution of glutamate- and GABA-immunoreactive neurons projecting to the cardioacceleratory center of the intermediolateral nucleus of the thoracic cord of SHR and WKY rats: a double-labeling study. Brain Res. 1994;638:139–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLISSIER G., DEMENGE P. Hypotensive and bradycardic effects elicited by spinal dopamine receptor stimulation: effects of D1 and D2 receptor agonists and antagonists. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1991;18:548–555. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLLOCK R., KERR R., MAXWELL D.J. An immunocytochemical investigation of the relationship between substance P and the neurokinin-1 receptor in the lateral horn of the rat thoracic spinal cord. Brain Res. 1997;777:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00965-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT M., BOLLER M., ÖZEN G., HALL W.C. Disinhibition in rat superior colliculus mediated by GABAC receptors. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:691–699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLOMON S.G., LLEWELLYN-SMITH I.J., MINSON J.B., ARNOLDA L.F., CHALMERS J.P., PILOWSKY P.M. Neurokinin-1 receptors and spinal cord control of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Brain Res. 1999;815:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAO Y.-X., LI Y.-Q., ZHAO Z.-Q. Synaptic interaction between GABAergic terminals and substance P receptor-positive neurons in rat spinal superficial laminae. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2000;21:911–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU S.Y., DUN N.J. Presynaptic GABAB receptor activation attenuates synaptic transmission to rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1992;572:94–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90456-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YASHPAL K., GAUTHIER S.G., HENRY J.L. Substance P given intrathecally at the spinal T9 level increases adrenal output of adrenaline and noradrenaline in the rat. Neuroscience. 1985;15:529–536. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YASHPAL K., RADHAKRISHNAN V., HENRY J.L. NMDA receptor antagonist blocks the facilitation of the tail-flick reflex in the rat induced by intrathecal administration of substance P and by noxious cutaneous stimulation. Neurosci. Lett. 1991;128:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIMURA M., NISHI S. Intracellular recordings from lateral horn cells of the spinal cord in vitro. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1982;6:5–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]