Abstract

The ability of the CGRP antagonist BIBN4096BS to antagonize CGRP and adrenomedullin has been investigated on cell lines endogenously expressing receptors of known composition.

On human SK-N-MC cells (expressing human calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) and receptor activity modifying protein 1 (RAMP1)), BIBN4096BS had a pA2 of 9.95 although the slope of the Schild plot (1.37±0.16) was significantly greater than 1.

On rat L6 cells (expressing rat CRLR and RAMP1), BIBN4096BS had a pA2 of 9.25 and a Schild slope of 0.89±0.05, significantly less than 1.

On human Colony (Col) 29 cells, CGRP8–37 had a significantly lower pA2 than on SK-N-MC cells (7.34±0.19 (n=7) compared to 8.35±0.18, (n=6)). BIBN4096BS had a pA2 of 9.98 and a Schild plot slope of 0.86±0.19 that was not significantly different from 1. At concentrations in excess of 3 nM, it was less potent on Col 29 cells than on SK-N-MC cells.

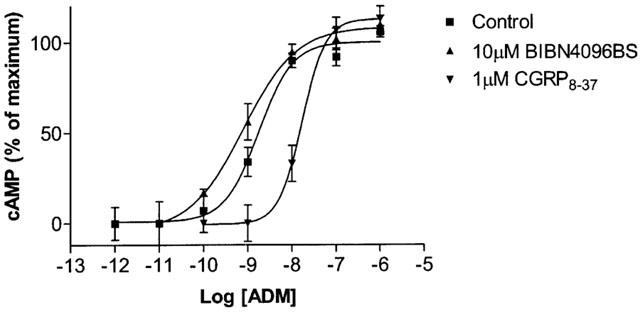

On Rat 2 cells, expressing rat CRLR and RAMP2, BIBN4096BS was unable to antagonize adrenomedullin at concentrations up to 10 μM. CGRP8–37 had a pA2 of 6.72 against adrenomedullin.

BIBN4096BS shows selectivity for the human CRLR/RAMP1 combination compared to the rat counterpart. It can discriminate between the CRLR/RAMP1 receptor expressed on SK-N-MC cells and the CGRP-responsive receptor expressed by the Col 29 cells used in this study. Its slow kinetics may explain its apparent ‘non-competive' behaviour. At concentrations of up to 10 μM, it has no antagonist actions at the adrenomedullin, CRLR/RAMP2 receptor, unlike CGRP8–37.

Keywords: CRLR, CGRP, RAMP1, RAMP2, CGRP8–37, BIBN4096BS, adrenomedullin, L6, SK-N-MC, Col 29

Introduction

Calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) is an abundant, 37 amino acid neuropeptide (Amara et al., 1982). It is part of a peptide family that includes calcitonin, amylin and adrenomedullin. CGRP has a complicated pharmacology. The peptide fragment CGRP8–37 shows a significantly higher affinity for CGRP receptors in preparations such as the guinea-pig atrium or ileum (pA2 >7) compared to tissues such as the rat or guinea-pig vas deferens (pA2 ∼6) (Dennis et al., 1990; Quirion et al., 1992; Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996). The receptors with a high affinity for CGRP8–37 have been designated CGRP1 receptors, as opposed to CGRP2 receptors that have a lower affinity for this peptide antagonist (Dennis et al., 1990; Juaneda et al., 2000). The linear agonists [acetamidomethyl-Cys2,7] human αCGRP and [ethylamide-Cys2,7] human αCGRP are reported to be CGRP2-selective although this is not always observed (Dennis et al., 1989; Dumont et al., 1997; Wisskirchen et al., 1998). The CGRP1 receptor is a complex formed from a G-protein coupled receptor, calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) and an accessory protein, receptor activity modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) (McLatchie et al., 1998). CRLR can associate with a second RAMP, RAMP2, to form an adrenomedullin receptor.

Whilst the CGRP1, CGRP2 receptor division has allowed the rationalization of much pharmacological data, it may be an oversimplification (Poyner & Marshall, 2001). There is no molecular correlate for the CGRP2 receptor, although cells and tissues expressing CGRP2-receptors also express CRLR and RAMP1 (Chakravarty et al., 2000; Rorabaugh et al., 2001). There is a 1000 fold spread in the reported affinity constants for CGRP8–37 (Marshall & Wisskirchen, 2000), which is difficult to accomodate within two receptor classes. It has never been possible to identify CGRP2 receptors in radioligand binding studies (Dennis et al., 1990; Rorabaugh et al., 2001).

Many of the problems with classifying CGRP receptors are a consequence of having to rely on a single, peptide antagonist for determining pharmacology. Recently a number of low molecular weight antagonists have been described. The best characterized of these is BIBN4096BS which arose out of optimization of a dipeptide lead compound (Doods et al., 2000). This compound had about a 200 fold selectivity for primate CGRP receptors (e.g. on human neuroblastoma SK-N-MC cells) compared to non-primate receptors (e.g. rat spleen) (Doods et al., 2000). However, the pharmacology of the rat spleen CGRP receptor is unclear as CGRP8–37 has not been examined on this tissue in functional assays. On rat isolated tissues, BIBN4096BS showed a 10 fold discrimination between CGRP-activated receptors on the rat right atrium and vas deferens (Wu et al., 2000). This work also demonstrated that BIBN4096BS could act as a potent antagonist against a novel receptor on the vas deferens that was activated both by [ethylamine-Cys2,7] human αCGRP and adrenomedullin. Isolated tissues are likely to contain very complicated mixtures of receptors; for example the guinea-pig vas deferens has high affinity binding for CGRP, amylin and adrenomedullin (Poyner et al., 1999). Thus it is not clear what the molecular composition of the receptors might be in the rat spleen, vas deferens and atrium. Accordingly, it is difficult to relate the data so far established for BIBN4096BS with defined complexes of CRLR and RAMPs.

We have recently investigated the nature of the CGRP receptors found in SK-N-MC, L6, Col 29 and Rat 2 cells (Choski et al., 2002). This study confirmed that SK-N-MC cells expressed CRLR and RAMP1, making this a suitable model for a human CGRP1 receptor. Rat L6 cells also expressed these components, establishing that these are suitable models for the rat CGRP1 receptor. Rat 2 cells expressed CRLR and RAMP2, making them a model of adrenomedullin receptors. Col 29 cells expressed CRLR and RAMP1 and had a CGRP1 pharmacology (Choski et al., 2002). We and others had previously observed a CGRP2-like pharmacology in these cells (Cox & Tough, 1994; Poyner et al., 1998). In the light of this discrepancy, it was of particular interest to re-examine the nature of the CGRP receptor in Col 29 cells using BIBN4096BS to see if it discriminates between CGRP-responsive receptors in human cells. Accordingly we have examined the behaviour of BIBN4096BS on SK-N-MC, L6, Col 29 and Rat 2 cells, comparing it with CGRP8–37.

Methods

Cell culture

SK-N-MC human neuroblastoma were a gift from Professor S. Nahorski, University of Leicester and Col 29 cells were a gift from Dr S. Kirkland, Imperial College. L6 and Rat-2 fibroblasts were purchased from the European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures (Porton Down, U.K.). Cells were cultured essentially as described previously (Poyner et al., 1992; 1998; Coppock et al., 1999). Briefly L6, Rat 2 and Col 29 cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated foetal calf serum. SK-N-MC cells were grown in a 1 : 1 mixture of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/F12 medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum. Cells were passaged at confluency with Trypsin/EDTA (Sigma) and grown for experiments in 48 well plates at 37°C in 5%CO2/air in a humidified atmosphere.

Measurement of cAMP

An hour prior to experiments, the medium on the cells was replaced with Kreb's solution (for Col 29, SK-N-MC and L6 cells) or serum free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (GIBCO–BRL), both supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 1 mM isobutyl methyl xanthine. The cells were preincubated with BIBN4096BS or CGRP8–37 for between 30 and 60 min as appropriate before addition of increasing concentrations of human (h)αCGRP or rat adrenomedullin. Incubations were terminated 5 min after addition of agonist by aspiration of the medium and addition of 0.1 ml of absolute ethanol. This was allowed to dry down at room temperature and the cAMP was extracted by addition of 0.25 ml of assay buffer containing (mM): EDTA, 5, HEPES 20, pH 7.5. The samples were agitated for 5 min before 50 μl samples were withdrawn and cAMP measured by a radioreceptor assay as described previously (Poyner et al., 1992).

Analysis of data

The data from each concentration–response curve was fitted to a sigmoidal concentration–response curve to obtain the maximum response, Hill Coefficient and EC50 using the fitting routine PRISM Graphpad. From the individual curves, dose–ratios were calculated and these were used to produce the Schild plots shown in Figure 2. The plots were fitted by linear regression using PRISM Graphpad. The pA2 was taken as the x intercept on the Schild plot where the slope was unconstrained; the pKb or apparent pKb was taken as the intercept where the slope was constrained to 1. For CGRP8–37, a pA2 was calculated from the dose–ratio produced by a single antagonist concentration using the formula pA2=log[antagonist]−log (dose ratio−1). As competitive behaviour has previously been demonstrated for CGRP8–37 on L6, Col 29 and SK-N-MC cells (Poyner et al., 1992; 1998), the pA2 can be assumed to be the same as the pKb.

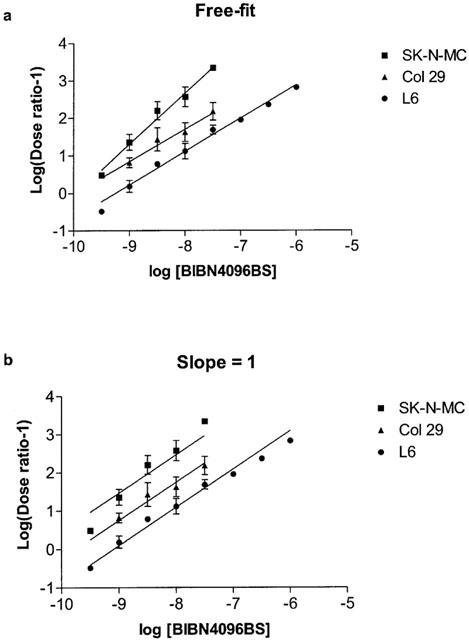

Figure 2.

Schild transform of concentration–response curves shown in Figure 1; (a) fitted to a straight line with unconstrained slope and (b) fitted to a straight line with slope constrained to 1.

Statistical analysis was either by Student's t-test (to determine whether the slopes of the unconstrained Schild plots were equal to 1) or by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test where several values were being compared. Significance was accepted at P<0.05; two-tailed tests were used throughout. All values are quoted as means±s.e.mean.

Drugs and materials

BIBN4096BS was synthesized at Boehringer Ingelheim, Pharma KG. Human αCGRP was purchased from Neosystems (Strassbourg, France). Human αCGRP was custom synthesised by ASG University (Szedgel, Hungary). Rat adrenomedullin was from Bachem (St. Helens, Merseyside, U.K.). Human αCGRP8–37 and peptidase inhibitors were purchased from Calbiochem. Isobutyl methyl xanthine was purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, Dorset, U.K.). Cell culture medium and foetal calf serum were purchased from GIBCO–BRL (Life Technologies, Paisley, Renfrewshire, U.K.). Other reagents were purchased from Sigma or Fisher. BIBN4096BS was dissolved in a small volume of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid, the pH adjusted to 7 with sodium hydroxide and diluted to give a stock solution of 100 mM (Wu et al., 2000). Both it and peptides were stored as frozen aliquots before use as previously described (Poyner et al., 1998).

Results

L6 cells (CRLR+RAMP1, CGRP1 receptor)

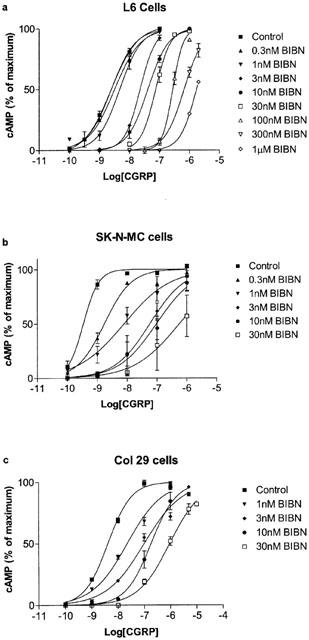

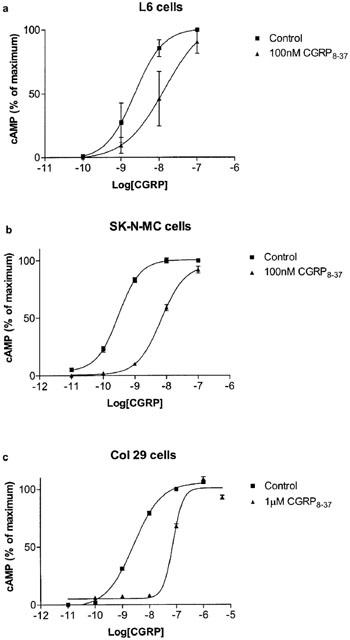

A range of BIBN4096BS concentrations from 0.3 nM to 1 μM were examined on L6 cells. In the absence of BIBN4096BS, hαCGRP stimulated cAMP production with a pEC50 of 8.61±0.03 (n=6). BIBN4096BS caused a rightwards shift in the concentration response curve to CGRP, as illustrated in Figure 1. At lower concentrations there was no significant depression of the maximum response; however at the highest concentrations it was not possible to use sufficient CGRP to examine the maximum response. After calculation of dose–ratios, a Schild plot was made of the data (Figure 2). This gave a slope of 0.89±0.05, significantly different from 1 (P<0.05). The pA2 was estimated from the x axis intercept as 9.25. On the same batch of cells, CGRP8–37 caused a parallel shift in the concentration response curve to CGRP; the dose–ratio was used to calculate an apparent pA2 of 7.81 (Figure 3), in line with previous estimates for the affinity of CGRP8–37 on these cells (Poyner et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

Effects of BIBN4096BS on the stimulation of cAMP production by human αCGRP in the presence of the indicated concentrations of BIBN4096BS in (a) L6 cells, (b) SK-N-MC cells and (c) Col 29 cells. Data represent means±s.e.mean of two to five experiments. Points were measured in duplicate in each experiment. Data are expressed as percentage of maximum cAMP production, estimated by fitting each line to a logistic Hill equation as described in the Methods. Maximum cAMP values were as follows: L6 cells, 270±30 pmol per 106 cells; SK-N-MC cells, 240±20 pmol per 106 cells; Col 29 cells, 170±19 pmol per 106 cells. Basal values were all below 10 pmol per 106 cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of CGRP8–37 on the stimulation of cAMP production by human αCGRP in the presence of the indicated concentrations of antagonist in (a) L6 cells, (b) SK-N-MC cells and (c) Col 29 cells. Data represent means±s.e.mean of four to seven experiments. Points were measured in duplicate in each experiment. Data are expressed as percentage of maximum cAMP production, estimated by fitting each line to a logistic Hill equation as described in the Methods. Maximum cAMP values were as follows: L6 cells, 250±27 pmol per 106 cells; SK-N-MC cells, 230±18 pmol per 106 cells; Col 29 cells, 180±17 pmol per 106 cells. Basal values were all below 10 pmol per 106 cells.

SK-N-MC cells (CRLR+RAMP1, CGRP1 receptor)

On SK-N-MC cells, hαCGRP stimulated cAMP production with a pEC50 of 9.46±0.05 (n=23). BIBN4096BS produced a rightwards shift in the concentration response curve; as with the L6 cells, it was not possible to establish whether CGRP could completely overcome the effects of the highest concentrations of BIBN4096BS (Figure 1). The Schild plot gave a slope of 1.37±0.16, significantly greater than 1 (P<0.05). The pA2 estimated from the x intercept was estimated as 9.95; however, due to the high slope of the Schild plot, this will underestimate the true pKb (Figure 2). Increasing the incubation time with BIBN4096BS from 30 min to 1 h or repeating the incubations in the presence of peptidase inhibitors (1 mM AEBSF, 0.8 μM aprotinin, 50 μM bestatin, 15 μM E-64, 20 μM leupeptin and 10 μM pepstatin) had little effect on the potency of BIBN4096BS (dose–ratio to 0.3 nM BIBN4096BS; control 3.2, 60 min preincubation 3.5, with peptidase inhibitors 4.0).

Col 29 cells (CRLR+RAMP1?, CGRP2 receptor?)

On Col 29 cells, hαCGRP stimulated cAMP production with a pEC50 of 8.38±0.05 (n=6). BIBN4096BS produced a rightwards shift in the concentration response curve (Figure 1). The slope of the Schild plot was 0.86±0.19, not significantly from 1. The pA2 taken from the x intercept was 9.98. As the slope was not significantly different from unity, it was possible to constrain this to 1, giving a pKb of 9.75±0.14. If the slope of the Schild plot for SK-N-MC cells was constrained to 1, the resulting intercept of 10.49±0.017 was significantly greater than the pKb measured on the Col 29 cells (P<0.001).

We have previously noted considerable variability in the affinity of Col 29 cells to CGRP8–37 (Poyner et al., 1998; Choski et al., 2002). The affinity of CGRP8–37 on the Col 29 cells used in the present study was compared with the SK-N-MC cells (Figure 2). Based on the dose–ratios measured in these experiments, the apparent pA2 for CGRP8–37 on the Col 29 cells was 7.34±0.19 (n=7), significantly less (P<0.01) than that estimated for the SK-N-MC cells (8.35±0.18, n=6).

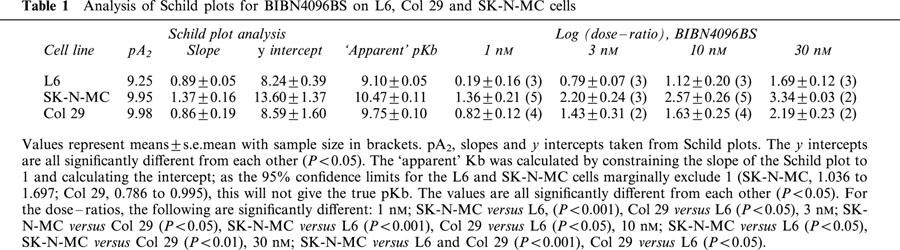

The nature of the BIBN4096BS-interacting receptor in SK-N-MC, Col 29 and L6 cells

The pA2 values for BIBN4096BS as estimated by the x-intercept from the Schild plots are very similar for all three cell lines. However, only for the Col 29 cells is the Schild slope consistent with strict competitive behaviour; the pA2 for the SK-N-MC cells will be an underestimate of the pKb whilst that for the L6 cells will be an overestimate. In Table 1, the data from the Schild plots is summarized; it can be seen that the dose–ratios for all three cell lines are significantly different from each other at high concentrations of BIBN4096BS. This argues that BIBN4096BS is able to distinguish between the receptors on each of the three cell lines. Furthermore, BIBN4096BS has very slow on and off rates; this suggests that the apparent non-competitive behaviour is simply a kinetic artefact (see Discussion). If this is accepted and the slopes of the Schild plots for all three cell lines are constrained to 1, the intercepts are significantly different from each other (Figure 2b, Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of Schild plots for BIBN4096BS on L6, Col 29 and SK-N-MC cells

Rat 2 cells (CRLR+RAMP2, adrenomedullin receptor)

Human αCGRP was inactive on Rat 2 cells at concentrations of up to 1 μM but rat adrenomedullin caused a concentration-dependant stimulation of cAMP production with a pEC50 of 8.75±0.11 (n=3) (Figure 4). This was weakly antagonized by CGRP8–37, with a pA2 of 6.72±0.06 (n=3), estimated from the shift in the concentration–response curve produced by 1 μM of the antagonist. At concentrations of up to 10 μM, BIBN4096BS was unable to antagonize adrenomedullin.

Figure 4.

Effects of CGRP8–37 and BIBN4096BS on the stimulation of cAMP production by rat adrenomedullin in Rat 2 cells. Data represent means±s.e.mean of three to four experiments. Points were measured in triplicate in each experiment. Data are expressed as percentage of maximum cAMP production, estimated by fitting each line to a logistic Hill equation as described in the Methods. Maximum cAMP values were 25±2.7 pmol per 106 cells. Basal values were all below 1 pmol per 106 cells.

Discussion

This study describes the ability of BIBN4096BS to interact with cell lines expressing human and rat CGRP1(CRLR/RAMP1) receptors (i.e. SK-N-MC and L6 cells), rat adrenomedullin receptors (CRLR/RAMP2, Rat 2 cells) and a potential human CGRP2-like receptor (Col 29 cells). The use of cell lines expressing endogenous receptors has some advantages over artificially transfected systems. In particular, it is apparent that batches of some cell lines such as HEK293T and Cos 7 cells express endogenous CRLR or RAMPs. Some batches of Cos 7 cells express an endogenous CRLR that accounts for up to 30% of the binding of CGRP when they are transfected with human RAMP1 (A Conner, unpublished observations). Thus the response seen with these cells will reflect a pattern of mixed monkey/human CRLR expression.

In confirmation of previous observations (Doods et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2000; Edvinsson et al., 2002), BIBN4096BS acted as a very potent antagonist at all CGRP-responsive receptors tested. The reported pA2 values of 11 and 11.2 from the studies of Doods et al. (2000) and Edvinsson et al. (2002) are in good agreement with the values from our study at high antagonist concentration (>1 nM). However, it is apparent that in SK-N-MC cells under the experimental conditions used in this study, BIBN4096BS does not follow strict competitive inhibition as the slope of the Schild plot is greater than 1. A similar result was found with the L6 cells. In this case, the Schild plot slope is less than 1. In neither case is the discrepancy large. For SK-N-MC cells, we have attempted to investigate whether this may be due to peptidase activity (BIBN4096BS contains a peptide bond, albeit highly modified) but the cocktail of, peptidase inhibitors used in this study made little difference. Increasing the incubation time also made little difference. However, using [3H]-BIBN4096BS, slow on/off-kinetics of this compound was observed compared to that of [125I]-CGRP (Schindler & Doods, 2002). At high or low antagonist concentration, kinetic artefacts are more likely to occur. Thus at low concentrations, even 60 min may not be sufficient to allow the drug to reach equilibrium. At high concentrations it is possible that once the BIBN4096BS is bound, its slow off-rate means there is insufficient time for the CGRP to equilibrate with the receptor. It is not practical to increase the incubation time for CGRP, as desensitization is observed after 10 min exposure to the peptide (Poyner et al., 1992). For both SK-N-MC and L6 cells, if the dose–ratios obtained with very low (0.3 nM) and high (300 nM, 1 μM) concentrations of BIBN4096BS are excluded from the Schild analysis, then the resulting plots have slopes that are not significantly different from 1. Thus it remains possible that the underlying reason for the apparent non-competitive inhibition is related to the experimental conditions used in this study.

L6 cells express adrenomedullin receptors in addition to CGRP receptors (Coppock et al., 1996). This may provide an additional explanation of the apparent non-competitive behaviour of BIBN4096BS at these cells. Although the adrenomedullin receptors are not directly linked to stimulation of cAMP production, it is possible that at high CGRP concentrations, CGRP can activate these receptors and that indirectly this leads to some cAMP production that is not antagonized by BIBN4096BS.

For SK-N-MC cells, the pA2 estimated from the x intercept with an unconstrained slope (9.95) probably underestimates the true affinity. Assuming that BIBN4096BS acts predominantly in a competitive fashion at the CRLR/RAMP1 complex, then the ‘apparent pKb' in Table 1 of 10.57, determined by constraining the slope of the Schild plot to 1 is probably a better estimate, although even this may be an underestimate. BIBN4096BS is a more potent antagonist on L6 cells than CGRP8–37, in line with what would be predicted from the other published studies (Doods et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2000). Given the problems with the slope of the Schild plots, it is not possible to estimate how much more potent BIBN4096BS is on human CRLR/RAMP1 compared to rat CRLR/RAMP1, as the ratio depends on the concentration of BIBN4096BS used. Based on the data shown in Figure 2a and Table 1, this could vary between 5 fold to over 10,000 fold; a comparison of the apparent pKb values in Table 1 shows a 24 fold selectivity. The results clearly demonstrate that BIBN4096BS shows preferential binding to the human CRLR/RAMP1 complex in functional assays and that the differences in affinity reported previously are due to genuine species differences within the same receptor subtype.

It has been previously reported that BIBN4096BS has a very low affinity at displacing adrenomedullin in radioligand binding assays (Doods et al., 2000); however it was a good antagonist at an adrenomedullin receptor in the rat vas deferens. The inability to antagonize adrenomedullin at the CRLR/RAMP2 complex expressed by Rat 2 cells demonstrates that it shows at least 1000 fold preference for CRLR/RAMP1 in rats. The nature of the adrenomedullin receptor in the rat vas deferens antagonized by BIBN4096BS remains unknown, but this data suggests that it is most unlikely to be a simple CRLR/RAMP2 complex. It is interesting to note that against adrenomedullin, CGRP8–37 has a pA2 of 6.72; greater or equal to that found against CGRP2-like receptors (Dennis et al., 1990; Wisskirchen et al., 1998; Marshall & Wisskirchen, 2000). Thus it should be used with care, particularly to distinguish between adrenomedullin and CGRP when the latter acts through the CGRP2 group of receptors. It remains a formal possibility that BIBN4096BS has a higher affinity against the human CRLR/RAMP2 complex than the rat equivalent examined in this study.

Sexton et al. (2001) have argued that BIBN4096BS is likely to derive its specificity for CGRP over adrenomedullin by binding to RAMP1 rather than CRLR. Recently Kane and co-workers have produced radioligand binding data to suggest that BIBN4096BS interacts with residue 74 of human RAMP1 (Mallee et al., 2002) and that this is responsible for the human versus rat selectivity. The functional data from this study is consistent with these findings. It would be unsurprising if the binding domains for BIBN4096BS and CGRP do not fully overlap, although it is likely that they will share some points of contact both on RAMP1 and CRLR. The greater selectivity of BIBN4096BS for CRLR/RAMP1 over CRLR/RAMP2 compared to CGRP8–37 may imply that the latter compound undergoes greater interactions with CRLR. As this is common to both receptors, its selectivity would be predicted to be less than that of BIBN4096BS. It will be of considerable interest to compare these compounds on the CRLR/RAMP3 complex, which functions as a mixed adrenomedullin/CGRP receptor (McLatchie et al., 1998; Husmann et al., 2000).

Col 29 cells are derived from human colonic epithelium (Kirkland, 1986). These have been reported to show CGRP2-like pharmacology (Cox & Tough, 1994). Recently, we have found the cells to express CRLR and RAMP1 and to show a pharmacology identical to that of SK-N-MC cells (Choski et al., 2002), in contrast to our previous data (Poyner et al., 1998). It was not possible to account for the change in behaviour of these cells. In the present study a fresh batch of cells was examined, although ultimately it was derived from the same source (Kirkland, 1985) as those examined previously by Cox and Tough and ourselves. CGRP8–37 had a pA2 estimated from a single antagonist concentration in excess of 7. This would normally be considered to be diagnostic of a CGRP1 receptor; however, this affinity was significantly less than that measured on SK-N-MC cells with the same batch of CGRP8–37. To try and control the affinity of the Col 29 cells for CGRP8–37 a variety of manipulations were carried out, including serum starving the cells for 24 h before use or exchanging normal and heat inactivated foetal calf serum. However, these did not produce any reproducible effect on the behaviour of the Col 29 cells. It is possible that the affinity for CGRP8–37 is determined by one or more accessory factors, perhaps acting in concert with CRLR and RAMP1, and that irregular expression of these factors are the cause of the variable affinity for CGRP8–37. It should be noted that Cox and Tough reported no effects of 3 μM CGRP8–37, whereas in our hands this concentration did antagonize CGRP (Poyner et al., 1998). Thus the variation in response to CGRP8–37 seems to be a long-standing phenomenon.

On the batch of Col 29 cells used in the current experiment, BIBN4096BS proved to be a more potent antagonist than CGRP8–37. Unlike the SK-N-MC cells, the slope of the Schild plot was not significantly different from unity. At low concentrations, BIBN4096BS was as potent as on the SK-N-MC cells. However at higher concentrations, the dose–ratio values and hence the affinity were significantly lower on the Col 29 cells compared to the SK-N-MC cells. Thus both CGRP8–37 and BIBN4096BS can discriminate between the CGRP-activated receptors on these cell lines. Whether it is appropriate to call the receptor on the Col 29 cells ‘CGRP2' receptors is less clear, given the apparently high affinity for CGRP8–37. It is clear that the Col 29 cells can change their properties in culture to show a range of affinities for CGRP8–37 and so they must be used with care. The present study does support the concept that in humans CGRP can activate a variety of receptors with high affinity. However, only the molecular nature of the CGRP1 CRLR/RAMP1 receptor is understood. The ‘CGRP2' receptor may be a distinct molecular entity or it may represent activation of some other receptor (amylin or adrenomedullin) by CGRP (see Poyner et al., 2002 for further discussion of this issue).

In conclusion, this study describes the behaviour of BIBN4096BS on a number of CGRP and adrenomedullin receptors of known molecular composition. BIBN4096BS has a higher affinity for human CRLR/human RAMP1 compared to rat CRLR/rat RAMP1. It has a very low affinity for rat CRLR/rat RAMP2. However, under the assay conditions tested, the blockade of CGRP-induced effects by BIBN4096BS appear, in part, to be insurmountable. It can discriminate between the CRLR/RAMP1 complex expressed by SK-N-MC cells and the CGRP-activated receptor on Col 29 cells. This latter receptor may consist of CRLR and RAMP1 with an unknown accessory factor. However the pharmacology of the Col 29 cells appears to show considerable variation with batch and passage number.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Wellcome Trust for support of this work. D.L. Hay was supported by a MRC studentship.

Abbreviations

- BIBN4096BS

1-Piperidinecarboxamide, N-[2-[[5amino-1-[[4-(4-pyridinyl)-1-piperazinyl]carbonyl]pentyl]amino]-1-[(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)methyl]-2-oxoethyl]-4-(1,4-dihydro-2-oxo-3(2H)-quinazolinyl)

- Col 29

Colony 29

- CRLR

Calcitonin receptor-like receptor

- RAMP

Receptor activity modifying protein

References

- AMARA S.G., JONES V., ROSENFELD M.G., ONG E.S., EVANS R.M. Alternative RNA processing in calcitonin gene expression generates mRNA encoding different polypeptide products. Nature (Lond) 1982;298:240–244. doi: 10.1038/298240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAKRAVARTY P., SUTHAR T.P., COPPOCK H.A., NICHOLL C.G., BLOOM S.R., LEGON S., SMITH D.M. CGRP and adrenomedullin binding correlates with transcript levels for calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) and receptor activity modifying proteins (RAMPs) in rat tissues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:189–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOSKI T., HAY D.L., LEGON L., POYNER D.R., HAGNER S., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. Comparison of the expression of calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) and receptor activity modifying proteins (RAMPs) with CGRP and adrenomedullin binding in cell lines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:784–792. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPPOCK H.A., OWJI A.A., AUSTIN C., UPTON P.D., JACKSON M.L., GARDINER J.V., GHATEI M.A., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. Rat-2 fibroblasts express specific adrenomedullin receptors, but not calcitonin-gene-related-peptide receptors, which mediate increased intracellular cAMP and inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Biochem. J. 1999;338:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPPOCK H.A., OWJI A.A., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. A rat skeletal muscle cell line (L6) expresses specific adrenomedullin binding sites but activates adenylate cyclase via calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. Biochem. J. 1996;318:241–245. doi: 10.1042/bj3180241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COX H.M., TOUGH I.R. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors in human gastrointestinal epithelia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:1243–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS T., FOURNIER A., CADIEUX A., POMERLEA U.F., JOLICOEUR F.B., ST PIERRE S., QUIRION R. hCGRP8–37, a calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonist revealing calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor heterogeneity in brain and periphery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;254:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS T., FOURNIER A., ST PIERRE S., QUIRION R. Structure-activity profile of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and brain tissues. Evidence for receptor multiplicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:718–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOODS H., HALLERMAYER G., WU D., ENTZEROTH M., RUDOLF K., ENGEL W., EBERLEIN W. Pharmacological profile of BIBN4096BS, the first selective small molecule CGRP antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:420–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMONT Y., FOURNIER A., ST PIERRE S., QUIRION R. A potent and selective CGRP2 agonist, [Cys(Et)2,7]hCGRP alpha: comparison in prototypical CGRP1 and CGRP2 in vitro bioassays. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDVINSSON L., ALM R., SHAW D., RUTLEDGE R.Z., KOBLAN K.S., LONGMORE J., KANE S.A. Effect of CGRP receptor antagonist BIBN4096BS in human cerebral, coronary and omental arteries and SK-N-MC cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;434:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUSMANN P.M., SEXTON J.A., FISCHER J.A., BORN W. Mouse receptor-activity-modifying proteins 1, -2 and -3: amino acid sequence, expression and function. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000;162:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUANEDA C., DUMONT Y., QUIRION R. The molecular pharmacology of CGRP and related peptide receptor subtypes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:432–438. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRKLAND S.C. Dome formation by a human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line (HCA-7) Cancer Res. 1985;45:3790–3795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALLEE J.J., SALVATORE C.A., LEBOURDELLES B., OLIVER K.R., LONGMORE J., KOBLAN K., KANE S.A. RAMP1 determines the species selectivity of non-peptide CGRP receptor antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14294–14298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL I., WISSKIRCHEN F.M.CGRP receptor heterogeneity: use of CGRP8–37 The CGRP Family: Calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), Amylin and Adrenomedullin 2000Texas: Landes Biosciences; 13–24.ed. Poyner D.R., Marshall I., Brain S.D. pp [Google Scholar]

- MCLATCHIE L.M., FRASER N.J., MAIN M.J., WISE A., BROWN J., THOMPSON N., SOLARI R., LEE M.G., FOORD S.M. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., ANDREW D.P., BROWN D., BOSE C., HANLEY M.R. Pharmacological characterization of a receptor for calcitonin gene-related peptide on rat, L6 myocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., MARSHALL I. CGRP receptors: beyond the CGRP(1)-CGRP(2) subdivision. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001;22:223–223. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)91555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., SEXTON P.M., MARSHALL I., SMITH D.M., QUIRION R., BORN W., MUFF R., FISCHER J.A., FOORD S.M. International Union of Pharmacology. The mammalian CGRP, adrenomedullin, amylin and calcitonin receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:1–14. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., SOOMETS U., HOWITT S.G., LANGEL U. Structural determinants for binding to CGRP receptors expressed by human SK-N-MC and Col-29 cells: studies with chimeric and other peptides. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1659–1666. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., TAYLOR G.M., TOMLINSON A.E., RICHARDSON A.G., SMITH D.M. Characterization of receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide and adrenomedullin on the guinea-pig vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1276–1282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUIRION R., VAN ROSSUM D., DUMONT Y., ST PIERRE S., FOURNIER A. Characterization of CGRP1 and CGRP2 receptor subtypes. Anal. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;657:88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RORABAUGH B.R., SCOFIELD M.A., SMITH D.D., JEFFRIES W.B., ABEL P.W. Functional calcitonin gene-related peptide subtype 2 receptors in porcine coronary arteries are identified as calcitonin gene-related peptide subtype 1 receptors by radioligand binding and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:1086–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHINDLER M., DOODS H. Binding properties of the novel, non-peptide CGRP receptor antagonist radioligand [3H]BIBN 4096BS. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;442:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEXTON P.M., ALBISTON A., MORFIS M., TILIKARATNE N. Receptor activity modifying proteins. Cell. Signall. 2001;13:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMLINSON A.E., POYNER D.R. Multiple receptors for CGRP and amylin on guinea pig ileum and vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1362–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISSKIRCHEN F.M., BURT R.P., MARSHALL I. Pharmacological characterization of CGRP receptors mediating relaxation of the rat pulmonary artery and inhibition of twitch responses of the rat vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1673–1683. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU D., EBERLEIN W., RUDOLF K., ENGEL W., HALLERMAYER G., DOODS H. Characterisation of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors in rat atrium and vas deferens: evidence for a [Cys(Et)(2, 7)]hCGRP-preferring receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;400:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]