Abstract

Pharmacological properties of nifedipine-insensitive, high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in rat mesenteric terminal arteries (NICCs) were investigated and compared with those of α1E and α1G heterologously expressed in BHK and HEK293 cells respectively, using the patch clamp technique.

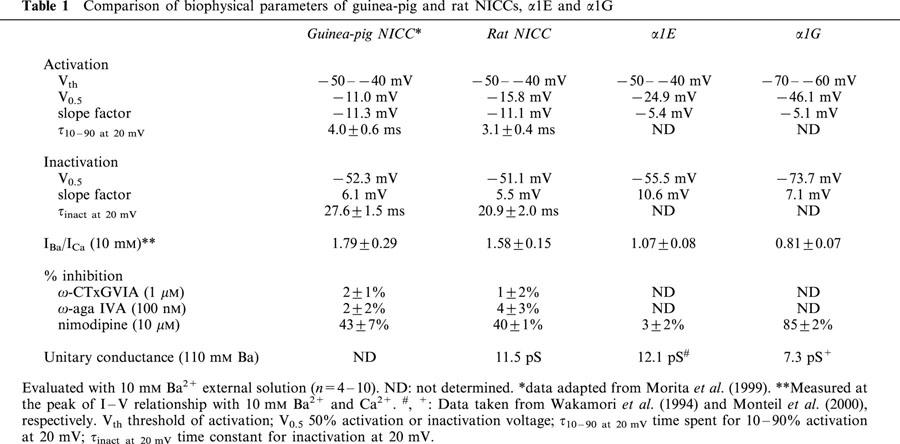

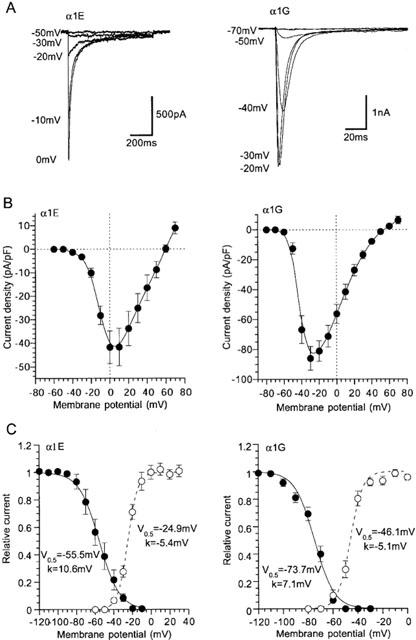

With 10 mM Ba2+ as the charge carrier, rat NICCs (unitary conductance: 11.5 pS with 110 mM Ba2+) are almost identical to those previously identified in a similar region of guinea-pig, such as in current-voltage relationship, voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, and divalent cation permeability. However, these properties are considerably different when compared with α1E and α1G.

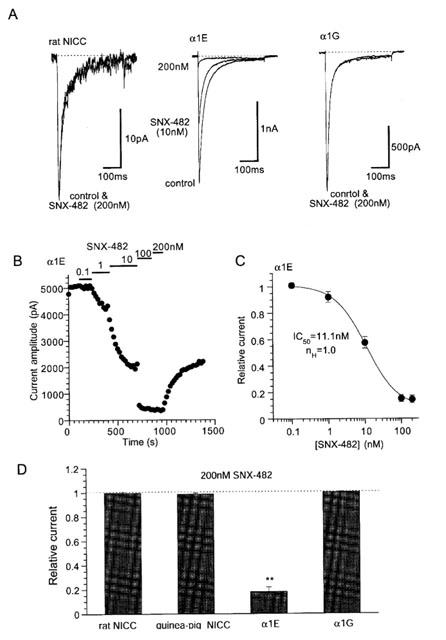

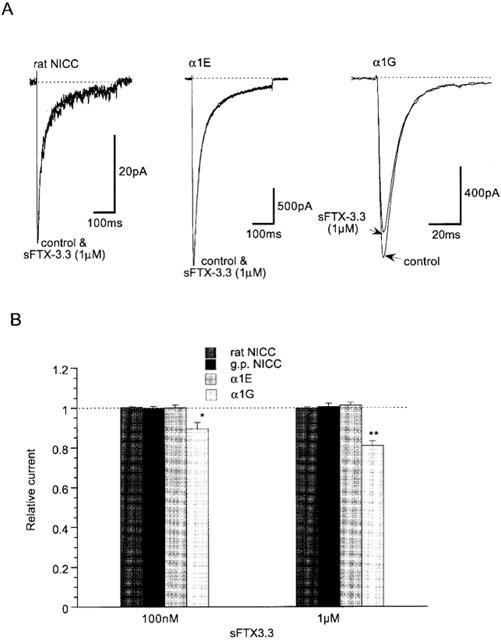

SNX-482(200 nM and sFTX3.3 (1 μM), in addition to ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 μM) and ω-agatoxin IVA (100 nM), were totally ineffective for rat NICC currents, but significantly suppressed α1E (by 82% at 200 nM; IC50=11.1 nM) and α1G (by 20% at 1 μM) channel currents, respectively. A non-specific T-type Ca2+ channel blocker nimodipine (10 μM) differentially suppressed these three currents (by 40, 3 and 85% for rat NICC, α1E and α1G currents, respectively).

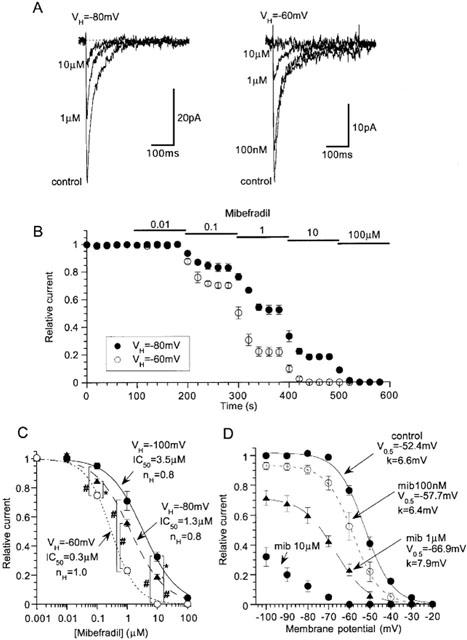

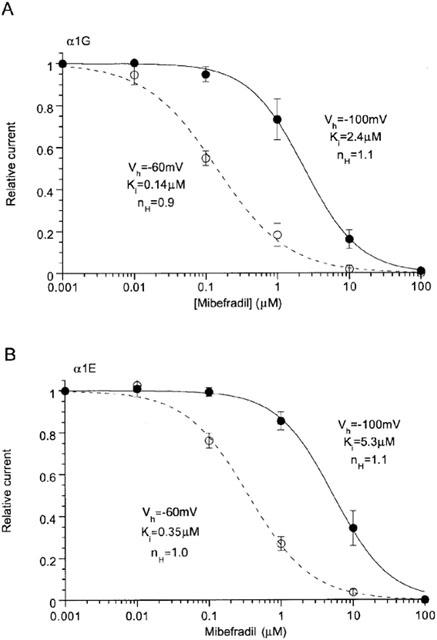

Mibefradil, the widely used T-type channel blocker, almost equally inhibited rat NICC and α1G currents in a voltage-dependent fashion with similar IC50 values (3.5 and 0.3 μM and 2.4 and 0.14 μM at −100 and −60 mV, respectively). Furthermore, other organic T-type channel blockers such as phenytoin, ethosuximide, an arylpiperidine derivative SUN N5030 (IC50=0.32 μM at −60 mV for α1G) also exhibited comparable inhibitory efficacies for NICC currents (inhibited by 22% at 100 μM; IC50=27.8 mM; IC50=0.53 μM, respectively).

These results suggest that despite distinctive biophysical properties, the rat NICCs have indistinguishable pharmacological sensitivities to many organic blockers compared with T-type Ca2+ channels.

Keywords: dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ channel, T-type Ca2+ channel, mibefradil

Introduction

Resistant arterioles are in a partially contracted state due to continuous Ca2+ entry under the tonic influence of intraluminal pressure and sympathetic nerve activity (Hirst & Edwards, 1989; Mulvany & Aalkjar, 1990; Hill et al., 2001). In most of arterial trees, the main route of this Ca2+ entry has been believed to be dihydropyridine (DHP)-sensitive, L-type Ca2+ channels (Nelson et al., 1990; Kotlikoff et al., 1999), but in some vascular tissues such as the coronary artery, contribution of T-type Ca2+ channels has also been suggested (Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1990; Cribbs, 2001). Recent investigations have however revealed that in some peripheral resistant arterioles, DHP-insensitive, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) biophysically and pharmacologically distinguishable from L- or T-type channels may have more physiological importance. For example, in rat renal afferent arterioles, the prominence of P/Q type Ca2+ channels and their functional importance to maintain the arteriolar tone have been demonstrated (Hansen et al., 2000). In guinea-pig mesenteric arterial tree, it has been found that the current density of rapidly inactivating, high voltage-activated (HVA), nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ channels (NICCs) with novel properties dramatically increases towards the periphery (Morita et al., 1999). The primary sympathetic neurotransmitter ATP in this vascular region (Gitterman & Evans, 2001) effectively modulates the activity of these NICCs, thus suggesting their potential contribution to the control of arteriolar tone and blood pressure (Morita et al., 2002). The properties of NICCs do not accord well with those of any hitherto-known DHP-insensitive VDCCs such as N-, P/Q, R- and T-type Ca2+ channels (Hofmann et al., 1999; Morita et al., 1999; Lacinova et al., 2000). Whereas the activation threshold and ionic permeability/blocking efficacy of divalent cations (Ba2+ is more permeable than Ca2+ and Cd2+ has a higher blocking efficacy than Ni2+) of NICCs are clearly of high voltage-activated (HVA) VDCC type, the slow deactivation of NICC current (time constants of the order of millisecond) is rather reminiscent of T-type Ca2+ channel. Furthermore, specific peptide blockers for N- and P/Q type channels, ω-conotoxin GVIA and ω-agatoxin IVA, are ineffective at inhibiting NICC activities, but nimodipine and amiloride, which have been reported to block T-type Ca2+ currents (Nooney et al., 1997; Heady et al., 2001), significantly reduce the amplitude of NICC current. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether these channel activities would reflect a yet unidentified VDCC or, alternatively, arise from the splice variants of known VDCCs in a varying subunit composition (Walker & Waard, 1998; Hofmann et al., 1999; Morita et al., 1999; Lacinova et al., 2000).

In the present study, in order to get more insight into the molecular nature of NICCs and facilitate the understanding of their molecular entity, we have investigated the pharmacological profile of NICC in further detail, in comparison with those of R- and T-type Ca2+ channels, which resemble NICCs best amongst hitherto-known DHP-insensitive Ca2+ channels. For this purpose, we employed cell lines stably expressing α1E and α1G (we chose α1G rather than other T-type VDCC isoforms as it has been best characterized and found to be expressed in some vascular tissues), and myocytes dissociated from the rat rather than guinea-pig mesenteric artery to record NICCs, since far greater genetic information is available for the rat than the guinea-pig. To validate this choice, in the first part of this work, we confirmed that NICCs almost identical to those of guinea-pig are indeed present in the rat mesenteric terminal artery. Surprisingly, the results of this study have shown that despite clear biophysical differences, the rat NICCs exhibit very similar sensitivities to many organic compounds including mibefradil compared with T-type Ca2+ channels.

Methods

Cell dispersion

All procedures used in this study were performed according to the guidelines approved by a local animal ethics committee of Kyushu University. Briefly, Wistar rats of either sex weighing 230–350 g were anaesthetized with inhalation of diethyl ether and sacrificed by decapitation. After opening the abdominal cavity, the whole mesentery was excised out and pinned on the rubber bottom of a dissecting dish filled with a modified Krebs solution. Short segments from the distal half of terminal branches measuring 50–100 μm in diameter were dissected with fine scissors and forceps, and consecutively incubated at 35°C, first in nominally Ca2+-free Krebs solution for 30 min and then the one supplemented with 2 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington, type 2) for 1.5 h. Single cells, yielded by gently triturating these digested segments using a blunt tipped pipette 20 to 30 times, were stored in 1 mM Ca2+-containing Krebs solution at 10°C until use.

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells stably expressing human α1G and rabbit α1E (BII; co-transfected with α2a/δ and β1b subunits; Wakamori et al., 1994), respectively, were maintained in a culture dish filled with Dulbecco s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) complemented with 10% foetal bovine albumin (FBS), 20 units ml−1 penicillin, 30 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 400 μg ml−1 G-418. Cells were re-seeded every 3–4 days before becoming confluent.

Electrophysiological measurements

For recording NICCs, myocytes dissociated from rat mesenteric terminal arteries were allowed to lodge on the bottom of a recording chamber for about 10 min. For recording T- and R-type Ca2+ currents, HEK293 and BHK cells (see above) adhering to the bottom of culture dish were trypsinized and re-seeded on cover slips (1×10 mm) pre-coated with poly-L-lysin, and used for experiments within 12–24 h. A commercial amplifier (Axopatch 1D, Axon Instruments) in conjunction with an A/D, D/A converter was used to generate voltages and sample current signals after low-pass filtering at 1 kHz (digitized at 2 kHz), under the control of an IBM computer (Aptiva) which was driven by a commercial software ‘Clampex v.6.02' (Axon Instruments). The P/4 or P/2 protocol was routinely employed to subtract leak currents, and 50–80% of series resistance (5–10 MΩ) was electronically compensated. Data analyses and illustration were performed using Clampfit v.6.02 (Axon Instruments). All experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C) and all illustrations displayed in figures are corrected for the leak.

For single channel recording, current signals were sampled at 10 kHz using a patch clamp amplifier (200B; Axon Instruments) after low pass filtering through an 8-pole Bessel filter (2 kHz). Leak and capacitive currents were corrected by subtracting the averages of 20–30 null traces from those exhibiting channel openings, which were then analysed using the software Clampfit 7.0 (Axon Instruments). The baseline and level of channel opening were determined by visual inspection.

Solutions

Solutions of the following composition were used (in mM); a modified Krebs solution: Na+ 140, K+ 6, Ca2+ 2, Mg2+ 1.2, Cl− 152.4, glucose 10, HEPES 10 (pH 7.4; adjusted by Tris base). Ten Ba2+-external solution: Na+ 140, K+ 6, Ba2+ 10, Mg2+ 1.2, Cl− 168.4, glucose 10, HEPES 10 (pH 7.4; adjusted by Tris base). Cs+-internal solution: Cs+ 140, Mg2+ 2, Cl− 144, phosphocreatine 5, Na2ATP 1, GTP 0.2, EGTA 10, HEPES 10 (pH 7.2; adjusted by Tris base). 110Ba2+ solution for single channel recording: Ba2+ 110, Cl− 220, HEPES 10 (10 μM nifedipine added; pH 7.4, adjusted by Tris base). 140K+ solution for single channel recording: K+ 140, Mg2+ 1.5, Cl− 143, glucose 10, HEPES 10, EGTA 1 (10 μM nifedipine added; pH 7.4, adjusted by Tris base). At the beginning of experiments each day, nifedipine (10 μM) was freshly dissolved in the bath solution, which was superfused continuously at a rate of 1–2 ml min−1 into the recording chamber (volume: ∼0.2 ml) via a gravity-fed perfusion system. For application of drugs, a fast and topical solution change device (‘Y-tube') was employed. In order to avoid possible contamination by highly lipophilic drugs remaining in the tube, the route was vigorously washed with an acidic water/ethanol (∼30%) mixture after each experiment.

Chemicals

The following agents were purchased; ATP, GTP and EGTA from Dojin (Kumamoto, Japan). Nifedipine, nimodipine, phenytoin and ethosuximide from Sigma; ω-conotoxin GVIA, ω-agatoxin IVA and sFTX3.3 from Calbiochem. Mibefradil and SNX-482 were kindly provided by Hofmann La-Roche Ltd. and Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan), respectively. An arylpiperidine derivative SUN N5030 (Annoura et al., 2002) is a kind gift from Dr H. Annoura (Suntory Biomedical Research Ltd.).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. To evaluate statistical significance of difference between a given set of data, paired and unpaired t-tests and one-way ANOVA with pooled variance t-test with Bonferroni's correction were employed.

Results

Nifedipine-insensitive VDCCs in rat mesenteric terminal artery are the same channels as guinea-pig NICCs

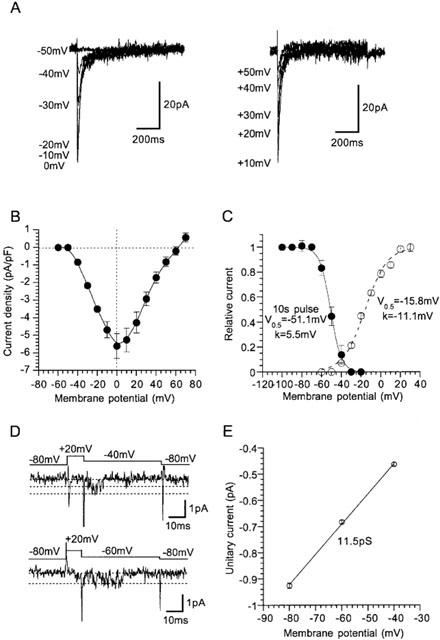

Figure 1 demonstrates the actual traces, current-voltage relationship and activation and inactivation curves of nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ channel (NICC) currents recorded from rat mesenteric terminal arterial myocytes. Since the amplitude of these currents was too small (5–10 pA at 0 mV) to analyse quantitatively, 10 mM Ba2+ rather than normal concentrations of Ca2+ was used as the charge carrier throughout the present study. The rat NICC current shows a rapidly inactivating feature (Figure 1A) and its threshold and peak voltages of activation (Figure 1B) and parameters describing the voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation (Figure 1C) are all comparable to those previously reported for NICCs in the same arterial region of the guinea-pig (Morita et al., 1999; see Table 1). Furthermore, activation (measured as a time spent for 10–90% of the peak) and inactivation (obtained by mono-exponential fitting) time constants of rat NICCs are of similar order to those of guinea-pig NICCs, and larger conductivity of Ba2+ than Ca2+ (about 1.5 times) is also a common feature shared by these two NICCs (Table 1). The amplitude of rat NICC current was rundown-resistant and the time course of inactivation remained almost unchanged regardless of the species of charge-carrying cations (not shown). In addition, other widely used L-type Ca2+ channel blockers such as verapamil (100 μM) and diltiazem (100 μM) (data not shown) as well as subtype-specific VDCC channel blockers such as ω-conotoxin GVIA and ω-agatoxin IVA were totally ineffective at inhibiting the rat NICC current, whereas nimodipine (10 μM) which was previously shown to inhibit guinea-pig NICCs caused a similar degree of inhibition (Table 1; see also Figure 5). These results collectively indicate that rat NICCs belong to the same class of high voltage-activated (HVA) VDCC as NICCs identified in guinea-pig mesenteric terminal artery (Morita et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

Biophysical profile of nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ channel (NICC) current in rat mesenteric terminal artery. Bath; 10 mM Ba2+ external solution (10 μM nifedipine added). Pipette; Cs-internal solution. (A) Representative records of NICC evoked by 800 ms depolarizing step pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV at an interval of 20 s. (B) Current-voltage (I–V) relationship for rat NICC obtained from experiments as shown in A. The amplitude of NICC is normalized by the cell capacitance. (C) activation (open circles) and steady-state inactivation (evaluated by 10 s pre-conditioning pulses; filled circles) curves for rat NICC. Solid and dashed curves indicates the results of the best fits of data points by Boltzmann equation: 1/(1+exp((Vm−V0.5)/k)), where Vm, V0.5 and k denote the membrane potential, 50% activation or inactivation voltages, and slope factor, respectively. Activation curve is calculated by normalizing the chord conductance (the current amplitude is divided by the driving force) to its maximum. Symbols and bars indicate mean±s.e.mean from 5–8 cells. Actual traces (D) and the unitary current amplitude vs voltage relationship of single NICC activities (E) determined from four successful recordings). Pipette contained 110 mM Ba2+ solution supplemented with 10 μM nifedipine. Cells were bathed in 140 mM K+ solution (1 mM EGTA and 10 μM nifedipine added) to zero the transmembrane potential. Voltages values shown in the figure indicate the pipette potential with an inverted sign.

Table 1.

Comparison of biophysical parameters of guinea-pig and rat NICCs, α1E and α1G

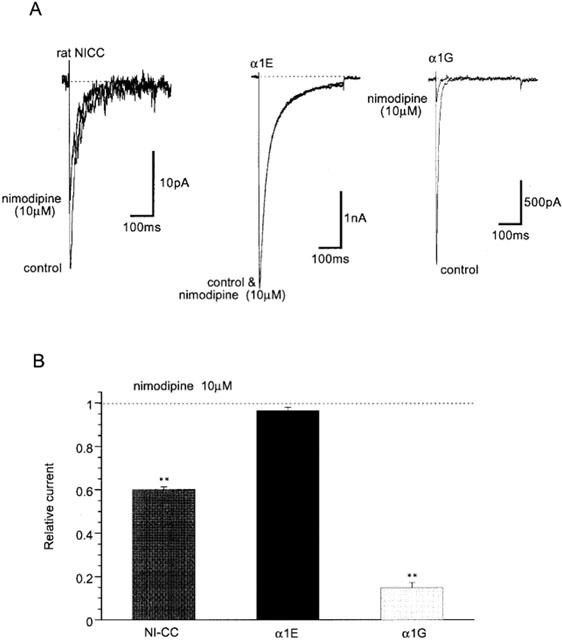

Figure 5.

Differential inhibitory effects of nimodipine on three nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ currents. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 3. (A) Representative records. (B) Summary of inhibitory effects of 10 μM nimodipine. **P<0.01 with ANOVA and pooled variance t-test. n=4–7.

Figure 1D and E demonstrate representative traces and the unitary current-voltage relationship of single rat mesenteric NICCs recorded in cell-attached configuration with a 110 mM Ba2+ containing pipette. The slope conductance of single NICCs determined between −80 and −40 mV is 11.5 pS, the value being similar to that of α1E but considerably larger than that for α1G obtained under the same ionic conditions (Table 1).

The current density of rat NICC in the terminal branches was as high as 5 pA/pF (Figure 1B) representing 60–90% of global voltage-dependent Ca2+ current (75±5%, n=6), but this became significantly smaller in more proximal branches of mesenteric arterial tree (0.3±0.2 pA/pF in the second branch, n=4; P<0.05 with unpaired t-test) with increased density of nifedipine-sensitive Ca2+ current. This finding suggests that contribution of NICC would increase in the peripheral region of rat mesenteric artery as observed previously for the guinea-pig mesenteric artery (Morita et al., 1999).

Differential pharmacological sensitivities to SNX-482, sFTX3.3 and nimodipine

Previous investigations on guinea-pig NICCs have suggested that they share some degree of biophysical and pharmacological similarities with R- and T-type Ca2+ channels (Morita et al., 1999). We therefore investigated the effects on rat NICCs of peptide blockers which have been reported to affect these two DHP-insensitive Ca2+ channels. For this purpose, we used BHK cells stably expressing α1E together with β1b and α2/δ subunits and HEK293 cells stably expressing α1G, as positive references for R- and T-type Ca2+ channels, respectively. As shown in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 1, important parameters characterizing the biophysical properties of VDCC, i.e. the current voltage-relationship, activation and inactivation curves and divalent cation permeability are clearly distinguishable among the three types of Ca2+ currents recorded under the identical ionic conditions (i.e. 10 mM Ba2+). SNX-482, a venom toxin recently reported to be selective for R-type Ca2+ channel (Newcomb et al., 1998), reduced the amplitude of α1E current dose-dependently (IC50=11 nM; Figure 3A–C), but did not at all affect α1G or rat NICC currents at its maximally effective concentration (200 nM; Figure 3A and D). On the other hand, sFTX3.3 (1 μM), a synthetic analogue of venom toxin FTX, which has been suggested to inhibit low voltage-activated Ca2+ currents at submicromolar concentrations (Scott et al., 1992; Norris et al., 1996), caused a modest but significant reduction in the amplitude of α1G current, whereas no detectable change was observed for rat NICC and α1E currents (Figure 4). The inability of SNX-482 and sFTX3.3 to block rat NICC current was also confirmed in myocytes derived from the same arterial region of guinea-pig (Figures 3B and 4B). Furthermore, nimodipine (10 μM), a dihydropyridine Ca2+ antagonist known to inhibit T-type Ca2+ current potently as well as guinea-pig NICC modestly (Nooney et al., 1997; Morita et al., 1999), produced a differential degree of inhibition of the three types of Ca2+ currents; α1G > rat NICC >α1E (Figure 5; Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that rat mesenteric NICCs have distinguishable pharmacological properties from heterologously expressed R- and T-type Ca2+ channels, and this may reflect their essential differences in molecular structure.

Figure 2.

Activation and inactivation profiles of heterologously expressed α1E and α1G Ca2+ currents. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 1. Actual records (A) and I–V relationships (normalized by cell capacitance) (B) of α1E (holding potential; −80 mV) and α1G (holding potential; −100 mV). (C) Activation and steady state inactivation curves evaluated as in Figure 1. Solid and dashed curves represent the best fits of data points with Boltzmann equation. Symbols and bars indicate mean±s.e.mean from 6–8 cells.

Figure 3.

Channel type-specific inhibitory effects of SNX-482. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 1 except for 400 ms voltage step pulses being used. Holding potential: −80 mV (rat NICC and α1E) and −100 mV (α1G). Depolarizing step pulses to 0 mV (rat NICC and α1E) or −20 mV (α1G) were repetitively applied every 20 s. Representative records (A) and time course (B) of the effects of SNX-482. (C) Concentration-inhibition relationship of α1E for SNX-482. Symbols and bars indicate mean±s.e.mean from eight individual experiments. Smooth solid curve is drawn according to the results of Hill analysis. (D) Comparison of the effects of 200 nM SNX-482 on rat and guinea-pig NICCs, α1E and α1G. **P<0.01 with ANOVA and pooled variance t-test. n=4–10.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effects of sFTX3.3 on three nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ currents. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 3. (A) Representative records. (B) Summary of inhibitory effects of 100 nM and 1 μM sFTX3.3. *P<0.05 with ANOVA and pooled variance t-test. n=5–6.

Mibefradil effectively blocks rat mesenteric NI-Ca2+ currents

Mibefradil is known to inhibit DHP-insensitive VDCCs more effectively than DHP-sensitive, L-type Ca2+ channels (Bezprovanny & Tsien, 1995). We therefore tested how this drug affects the rat NICC currents. As shown in Figure 6A,B, when the membrane was held at two different potential levels (−60 and −80 mV), cumulative addition of mibefradil produced dose-dependent reduction in the amplitude of NICC current with different efficacies. At more depolarized potentials, the amplitude of NICC current was more effectively reduced. Figure 6C shows concentration-inhibition curves for the effects of mibefradil at three different potentials. The IC50 values obtained by Hill fitting are clearly dependent on the holding potential, becoming smaller at more depolarized potentials (3.5, 1.3 and 0.3 μM at −100, −80 and −60 mV, respectively), while the stoichiometry of binding remained unchanged (nH=ca. 1.0). These results suggest that the effects of mibefradil on rat NICCs are state-dependent, i.e. the drug has different affinities for the resting (closed) and inactivated states of these channels. Consistent with this, the midpoint of inactivation curve (V0.5) of rat NICC current was shifted toward more negative potentials as the concentration of mibefradil was increased, with concomitant reduction in the maximum amplitude at very negative potentials.

Figure 6.

Voltage-dependent effects of mibefradil on rat NICC. Recording condition are the same as in Figure 3. Representative records (A) and the time course (B) of the effects of mibefradil on NICC evoked by depolarizing pulses to 0 mV (every 20 s) at two different holding potentials (−80 and −60 mV). (C) Concentration-inhibition curves for mibefradil at three different holding potentials. (D) Shifts of steady state inactivation curves at varying concentrations of mibefradil. The results of Hill (C) and Boltzmann (D) fitting are shown. n=5–7. In C, # and * indicate statistically significant differences with P values of <0.02 and <0.05, respectively, evaluated by pooled variance t-test with Bonferroni's correction.

We also evaluated the voltage-dependent effects of mibefradil on α1E and α1G currents. As summarized in Figure 7, both currents exhibited a clear dependence on the holding potential, with increased inhibition at more depolarized potential. Notably, IC50 values for α1G are comparable to those of rat NICC, suggesting that a similar extent of inhibition would occur on both channels at the same level of membrane potential. The inhibitory efficacy of mibefradil for α1E was slightly weaker than for these two channels, the extent being, however, not different more than 3-fold.

Figure 7.

Voltage-dependent effects of mibefradil on α1E and α1G. Ba2+ (10 mM) currents evaluated by depolarizing step pulses applied at every 20 s to 0 and −20 mV for α1E and α1G, respectively. n=5–6.

Other drugs inhibiting rat NICC currents

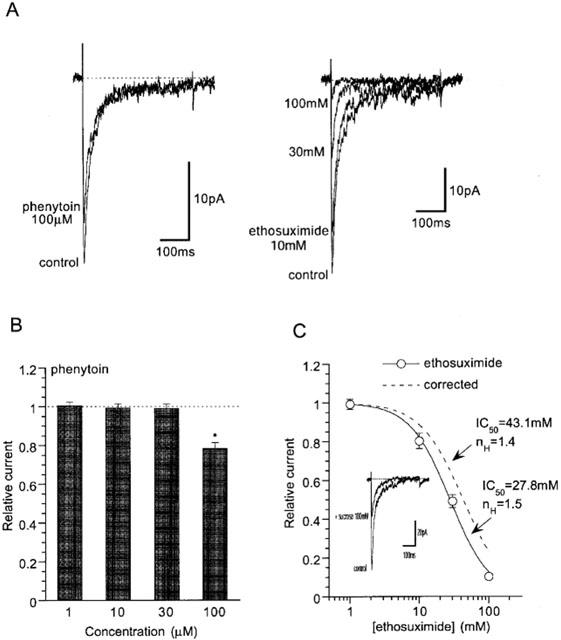

Afore-mentioned results suggest, albeit substantial differences present in the sensitivity to some drugs, considerable pharmacological resemblance exists between α1G and rat NICC currents. We therefore tested how other organic blockers reported to inhibit T-type Ca2+ currents (Heady et al., 2001) affect the rat NICC currents. As summarized in Figure 8, an anticonvulsant phenytoin, at the concentration of 100 μM that causes a substantial inhibition of native and recombinant T-type currents (Todorovic et al., 2000), reduced the amplitude of rat NICC current by about 20% (Figure 8B). Similarly, ethosuximide, another anticonvulsant reported to inhibit T-type Ca2+ current in tens of millimolar range (Todorovic et al., 2000), effectively inhibited the NICC current in the same concentration range (IC50: 27.8 mM; solid curve in Figure 8C). However, part of the latter effect could be ascribed to the hyperosmotic effects of the drug, since when the NICC current was recorded under identical ionic conditions except for the external osmolarity (various concentrations of sucrose added), its amplitude was significantly decreased with increased osmolarity. After correcting this indirect effect, the net inhibition of NICC by ethosuximide is less pronounced with a larger IC50 value of 43.1 mM (dashed curve in Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Effects of phenytoin and ethosuximide on rat NICC. (A) Actual records. (B) Dose-dependent effects of phenytoin. Phenytoin at concentrations higher than 100 μM was not dissolvable in the presence of 10 μM nifedipine. (C) Concentration–inhibition relationship of rat NICC for ethosuximide. Dashed curve indicates the results of Hill fitting after correcting the influence of osmolarity change on Ca2+ currents, which was estimated by adding varying concentrations of sucrose into the bathing solution (see inset). n=5.

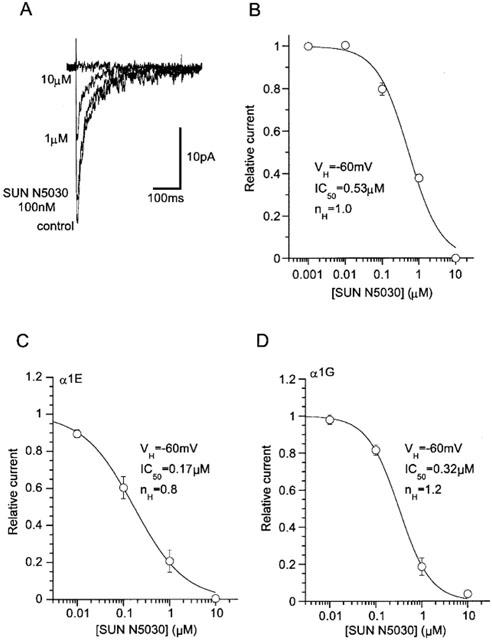

Finally, we tested a newly synthesized arylpiperidine (SUN N5030; see the Methods) which has been reported to inhibit both neuronal Na+ and T-type Ca2+ channels (Annoura et al., 2002). SUN N5030 potently suppressed rat NICC current, the value of IC50 (0.53 μM at −60 mV; Figure 9B) being comparable to that of mibefradil (Figure 6C). The effects of SUN N5030 on α1E and α1G currents were also tested at the same holding potential (−60 mV) under the identical ionic conditions (Figure 9C,D). The obtained IC50 values do not differ by a few times, indicating that this compound can not pharmacologically discriminate between these three types of DHP-insensitive Ca2+ channels.

Figure 9.

Potent and comparable inhibition of three NI-Ca2+ currents by an arylpiperidine derivative SUN N5030. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 3. (A) Actual records of rat NICC in the presence of varying concentration of SUN N5030. (B) Concentration-inhibition curves of rat NICC for SUN N5030. (C,D) Concentration-inhibition curves of α1G and α1E for SUN N5030. Sigmoid curves are drawn according to the results of Hill fitting. n= 6–13.

Discussion

The electrophysiological properties of rat mesenteric NICCs studied in the present study are indistinguishable from those of NICCs previously identified in the same region of guinea pig (Morita et al., 1999). Several essential features reflecting the molecular architecture of VDCC (e.g., voltage-dependence, ion permeability) and sensitivities to various blockers are almost identical between the two Ca2+ channels (Table 1). Similar to guinea-pig NICCs, the current density of rat NICCs was found to increase significantly toward the periphery of mesenteric arterial tree, and reciprocally, the fraction of nifedipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ current to become smaller. This accords with the observations of contractile experiments that the proportion of nifedipine-sensitive component of nerve-evoked contractions decreases with appearance of nifedipine-insensitive, excess K+-induced vasoconstrictions as the size of the mesenteric artery becomes smaller (Gitterman & Evans, 2001) and with the results of RT–PCR experiments that the transcripts of α1C mRNA, which can be detected in the proximal region of rat mesenteric artery, are not amplified from its peripheral arteriolar region (Gustafsson et al., 2001). Since similar HVA NICCs resistant to L, -N or -P/Q type Ca2+ channel blockers can also be recorded preferentially from the terminal branches of rabbit mesenteric artery (Morita, Inoue and Ito, unpublished data), it is plausible that this type of HVA NICCs plays a dominating role in the peripheral mesenteric circulation over the species difference.

According to a previous investigation (Morita et al., 1999), biophysical properties of NICCs in guinea-pig terminal mesenteric artery somewhat resemble those reported for R-type Ca2+ channels, whereas the pharmacological sensitivities of the former to some drugs (e.g. nimodipine, amiloride) are similar to those of T-type Ca2+ channels documented in the literature (Nooney et al., 1997; Heady et al., 2001). However, detailed comparison in this study has revealed that the three types of Ca2+ channels exhibit essential differences in ion permeation and voltage-dependence of gating, both of which are closely associated with the structure of the pore-forming α1 subunit (Table 1; see also Lacinova et al., 2000), and in sensitivities to isoform-specific toxin blockers such as SNX-482 and sFTX3.3. These results strongly support the possibility that NICCs in terminal mesenteric artery would molecularly be distinct from R-type (α1E) and T-type (α1G) Ca2+ channels. However, a recent RT–PCR experiment has provided an apparently conflicting evidence. In a small arteriolar region of rat mesenteric vasculature (diameter <40 μm) the transcripts of α1G and α1H can be detected, and consistent with this observation, nimodipine-insensitive (10 μM) vasocontrictions evoked by local electrical stimulation in the same arteriolar region are strongly attenuated by a locally perfused T-channel blocker mibefradil (10 μM; Gustafsson et al., 2001). Although these findings are in favor of the involvement of T-type Ca2+ channels, we feel that interpretation of these data would be equivocal with respect to the nonspecific effects of nimodipine (which inhibit mesenteric NICC current by ∼40% and T-type current due to α1G by ∼85%) and mibefradil (which block mesenteric NICCs and T-type Ca2+ currents almost equally; Figure 6). It should also be noted that successful amplification of transcripts using primer pairs recognizing limited sequences of α1G (base range: 3910– 4130) and α1H (37–334) mRNA (Gustafsson et al., 2001) would not necessarily mean a significant expression of these genes (or presumably their splice variants) at the protein level solely in smooth muscle cells. Considering these ambiguities together with the observed selectivity of toxin blockers (Figures 3 and 4) as well as distinct biophysical properties (Table 1), it seems at present too premature to ascribe the mesenteric NICCs simply to T-type Ca2+ channel genes, without directly elucidating the molecular structure of NICCs using molecular biological techniques.

Despite the essential differences described above, the observed pharmacological sensitivities to many organic compounds known to effectively block T-type Ca2+ channels such as mibefradil, SUN N5030, phenytoin and ethosuximide (Lacinova et al., 2000; Todorovic et al., 2000; Heady et al., 2001; Annoura et al., 2002) are unexpectedly similar among rat NICCs, α1G- and sometimes α1E channels (Figures 6,7,8,9). Mibefradil was developed as a new generation of VDCC blocker having a distinct structure from the other types of calcium channel antagonists such as dihydropyridines, phenylalkylamines and bezothiazepines (Osterrieder & Holck, 1989: for review; Bernink et al., 1996). This drug was soon shown to potently inhibit low voltage activated-Ca2+ currents in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (Mishra & Hermsmeyer, 1994) and to have strong anti-hypertensive and anti-anginal effects (Bernink et al., 1996; Li & Schiffrin, 1997; Massie, 1997; Frishman, 1997; Kobrin, 1998). However, subsequent electrophysiological analyses have unraveled that the selectivity of this drug for T-type over other types of VDCC would not be so superior as anticipated (Bezprovanny & Tsien, 1995; Molderings et al., 2000; Jimenez et al., 2000; Angus and Wright, 2000). In addition, many unexpected non-specific actions of mibefradil have been noted on a broader repertoire of ionic channels (Nilius et al., 1997; Gomora et al., 1999; Perchenet & Clement-Chomienne, 2000) and intracellular enzymes (Hermsmeyer & Miyagawa, 1996). Nonetheless, most early and even recent studies have interpreted the vasorelaxing and anti-hypertensive actions of mibefradil in the context of its selective blockade of T-type Ca2+ channels versus the other types of VDCCs (Bernink et al., 1996; Massie, 1997; Triggle, 1998; Hermsmeyer, 1998; Ozawa et al., 2001; but see e.g. Leuranguer et al., 2001). In light of the present study, however, it is obvious that at least in the mesenteric circulation, HVA-VDCCs pharmacologically resembling but biophysically distinct from ‘typical' T-type Ca2+ channels are predominantly expressed toward the periphery. Similar prevalence of non-L, non-T-type VDCCs, i.e. P/Q type Ca2+ channel in the peripheral arteriolar regulation has also been demonstrated in renal microvasculature (Hansen et al., 2000), and notably, the sensitivity of the molecular counterpart of this channel (α1A) to mibefradil has been shown to be greatly enhanced by co-expression of the β1b instead of β2a subunit to an extent comparable to that of T-type Ca2+ channels (Jimenez et al., 2000). These facts would prompt us to revise a currently prevailing view emphasizing the importance of L-type (and sometimes T-type) Ca2+ channels in vascular tone regulation (Nelson et al., 1990; Cribbs, 2001), and simultaneously necessitate the re-evaluation of specificity of vasorelaxant drugs including mibefradil, especially with respect to the heterogeneity of VDCC subunits expressed in the peripheral circulation.

The resting membrane potential of arteriolar smooth muscle ranges between −75–−60 mV in isolated arterioles (Hirst & Edwards, 1989), but this value becomes more depolarized when the arterioles are pressurized under cannulated conditions (e.g., ca. −40 mV at 70 mmHg; Potocnik et al., 2000; Hill et al., 2001). It is generally believed that this pressure-induced depolarization raises the rate of Ca2+ entry into the cell through activation of VDCCs, and simultaneously enhances the efficacy of anti-hypertensive drugs owing to the state-dependent mechanism (Bean et al., 1983; Hille, 1992). In fact, the observed IC50 values for NICC current inhibition by mibefradil were significantly smaller at more depolarized holding potentials (Figures 1 and 6), which was accompanied by the shift of steady state inactivation curves toward a more hyperpolarized direction (Figure 6). Such phenomena have been accounted for by the differential affinities of resting and inactivated states of VDCC for an applied blocker, and can be described by the following equation (‘modulated receptor model'; Bean et al., 1983; Hille, 1992).

where Vm, h(Vm), Kapp(Vm), KR and KI denote the membrane potential, the availability of VDCC at Vm, the apparent overall and resting- or inactivated-state-specific dissociation constants for a given blocker at Vm, respectively. As performed previously (e.g. Bezprovanny & Tsien, 1995), we adopted the IC50 values at −100 mV as KR, since at this potential nearly all Ca2+ channels are in the resting state (see Figures 1, 2). To calculate h(−60 mV) values, we used the Boltzmann parameters of steady state inactivation curves for each Ca2+ channel (see Figures 1, 2). KR and KI values obtained in this way were 3.5 and 0.08 μM, 2.4 and 0.12 μM, and 5.3 and 0.14 μM for rat mesenteric NICCs, α1G- and α1E-Ca2+ channels, respectively. These results indicate that all these three channels have a few tens-fold higher affinities for the inactivated state than the resting state, the results being comparable to those of previous studies (Jimenez et al., 2000; Gomora et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2000; Lacinova et al., 2000). Furthermore, very similar efficacies and voltage-dependence of mibefradil's actions on rat NICCs and α1G-channels suggest that in vivo situation the extent of inhibition exerted by mibefradil on these two channels would be indistinguishable. Although the frequency dependence of the effects of mibefradil on these channels has not been examined in the present study, this conclusion would be still valid for electrically less active resistant arterioles like the present preparation that normally do not exhibit regenerative Ca2+ spike activities under physiological ionic conditions (Kuriyama et al., 1982). The tone of arterioles is thought to be regulated by the non-inactivating Ca2+ entry chiefly through VDCCs (Nelson et al., 1990; Kotlikoff et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2001), and this property is indeed likely present in mesenteric NICCs, as suggested by the presence of ‘window current', a significant crossover of activation and inactivation curves (approximately between −50–−20 mV; Morita et al., 1999; 2002; Figure 1C).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Y. Mori (Center for Integrative Bioscience, The Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Okazki, Japan) and Dr T. Kobayashi (Tanabe Pharmaceutical Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for providing us with BHK and HEK 293 cells stably expressing α1E and α1G, respectively, and Dr Mark T. Nelson (Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, University of Vermont), for allowing H. Morita to perform single channel recordings in his laboratory. Thanks are due also to Dr H. Annoura (Suntory Biomedical Research Institute Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and Drs N. Chino and T. Watanabe (Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan) for generously supplying us with an arylpiperidine derivative SUN N5030 and SNX-482, respectively. This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Society of Japan Promotion for Sciences to Y. Ito and R. Inoue.

Abbreviations

- α1E, α1G

alpha-1E and G subunits of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

- ATP

adenosine 5′ triphosphate

- BHK

baby hamster kidney cells

- DHP

dihydropyridine

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- GTP

guanosine 5′-triphosphate

- EGTA

O,O′-bis(2-aminomethyl)ethyleneglycol-N,N,N′,N′-tetra-acetic acid

- FBS

foetal bovine albumin

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cells

- HVA

high voltage-activated

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- mibefradil

(1S,2S)-2-[2-[(3-(2-benzimidazolyl)propyl)methylamino]ethyl]-6-fluoro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-isopropyl-2-napthyl methoxyacetate dihydrochloride

- nH

Hill coefficient

- NICCs

nifedipine-insensitive Ca2+ channels

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- SUN N5030

1-(2-hydroxy-3-phenoxy)propyl-4-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-piperidine hydrochloride

- VDCCs

voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

- ω-CTxGVIA

omega conotoxin GVIA

- ω-aga IVA

omega agatoxin IVA

References

- ANGUS J.A., WRIGHT C.E. Targetting voltage-gated calcium channels in cardiovascular therapy. Lancet. 2000;356:1287–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02807-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANNOURA H., NAKANISHI K., UESUGI M., FUKUNAGA A., IMAJO S., MIYAJIMA A., TAMURA-HORIKAWA Y., TAMURA S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 4-arylpiperidines and 4-aryl-4-piperidinols: dual Na+ and Ca2+ channel blockers with reduced affinity for dopamine D2 receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:371–383. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAN B.P., COHEN C.J., TSIEN R.W. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1983;81:613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNINK P.J.L.M., PRAGER G., SCHELLING A., KOBRIN I. Antihypertensive properties of the novel calcium antagonist miberfadil (Ro 40-5967) Hypertension. 1996;27:426–432. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEZPROVANNY I., TSIEN R.W. Voltage-dependent blockade of diverse types of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels expressed in Xenopus Oocytes by the Ca2+ channel antagonist mibefradil (Ro 40-5967) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;48:540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRIBBS L.L. Vascular smooth muscle calcium channels. Could ‘T' be a target. Circ. Res. 2001;89:560–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRISHMAN W.H. Mibefradil: a new selective T-channel calcium antagonist for hypertension and angina pectoris. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997;2:321–330. doi: 10.1177/107424849700200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANITKEVICH V.Y., ISENBERG G. Contribution of two types of calcium channels to membrane conductance of single myocytes from guinea-pig coronary artery. J. Physiol. 1990;426:19–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GITTERMAN D.P., EVANS R.J. Nerve evoked P2X receptor contractions of rat mesenteric arteries; dependence on vessel size and lack of role of L-type calcium channels and calcium induced calcium release. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:1201–1208. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMORA J.C., ENYEART J.A., ENYEART J.J. Mibefradil potently blocks ATP-activated K+ channels in adrenal cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1192–1197. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMORA J.C., XU L., ENYEART J.A., ENYEART J.J. Effect of mibefradil on voltage-dependent gating and kinetics of T-type Ca2+ channels in cortisol-secreting cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUSTAFSSON F., ANDREASEN D., SALOMONSSON M., JENSEN B.L., HOLSTEIN-RATHLOU N-H. Conducted vasoconstriction in rat mesenteric arterioles: role for dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ channels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H582–H590. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEN P.B., JENSEN B.L., ANDREASEN D., FRIIS U.G., SKOTT O. Vascular smooth muscle cells express the α1A subunit of a P-/Q-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, and it is functionally important in renal afferent arterioles. Circ. Res. 2000;87:896–902. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEADY T.N., GOMORA J.C., MACDONALD T.L., PEREZ-REYES E. Molecular Pharmacology of T-type Ca2+ channels. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2001;85:339–350. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMSMEYER K. Role of T channels in cardiovascular function. Cardiology. 1998;89 Suppl.1:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000047273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMSMEYER K., MIYAGAWA K. Protein kinase C mechanism enhances vascular muscle relaxation by the Ca2+ antagonist, Ro 40-5967. J. Vas. Res. 1996;33:71–77. doi: 10.1159/000159134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL M.A., ZOU H., POTOCNIK S.J., MENINGER G.A., DAVIS M.J. Arteriolar smooth muscle mechanotransduction: Ca2+ signaling pathways underlying myogenic reactivity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:973–983. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLE B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 1992Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 408–412.Chapter 15, pp [Google Scholar]

- HIRST G.D.S., EDWARDS F.R. Sympathetic neuroeffector transmission in arteries and arterioles. Physiol. Rev. 1989;69:546–604. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFMANN F., LACINOVA L., KLUGBAUER N. Voltage-dependent calcium channels: from structure to function. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;139:33–87. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIMENEZ C., BOURINET E., LEURANGUER V., RICHARD S., SNUTCH T.P., NARGEOT J. Determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation affect mibefradil block of calcium channels. Neuropharmacol. 2000;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBRIN I. Anti-anginal and anti-ischemic effects of mibefradil, a new T-type calcium antagonist. Cardiology. 1998;89 Suppl.1:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000047276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTLIKOFF M.I., HERRERA G., NELSON M.T. Calcium permeant ion channels in smooth muscle. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;134:147–199. doi: 10.1007/3-540-64753-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURIYAMA H., ITO Y., SUZUKI H., KITAMURA K., ITOH T. Factors modifying contraction-relaxation cycle in vascular smooth muscles. Am. J. Physiol. 1982;243:H641–H662. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.5.H641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LACINOVA L., KLUGBAUER N., HOFMANN F. Low voltage-activated calcium channels: from genes to functions. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2000;19:121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEURANGUER V., MANGONI M.E., NARGEOT J., RICHARDS S. Inhibition of T-type and L-type calcium channels by mibefradil: physiologic and pharmacologic bases of cardiovascular effects. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2001;37:649–661. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI J.-S., SCHIFFRIN E.L. Effect of short-term treatment of SHR with the novel calcium channel antagonist mibefradil on function of small arteries. Am. J. Hypertens. 1997;10:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(96)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN R.L., LEE J.H., CRIBBS L.L., PEREZ-REYES E., HANCK D.A. Mibedradil block of cloned T-type calcium channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSIE B.M. Mibefradil: a selective T-type calcium antagonist. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997;80:23I–32I. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00791-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MISHRA S.K., HERMSMEYER K. Selective inhibition of T-type Ca2+ channels by Ro 40-5967. Circ. Res. 1994;75:144–148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLDERINGS G.J., LIKUGU J., GOTHERT M. N-type calcium channels control sympathetic neurotransmission in human heart atrium. Circulation. 2000;101:403–407. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTEIL A., CHEMIN J., BOURINET E., MENNESSIER G., LORY P., NARGEOT J. Molecular and functional properties of the human α1G subunit that forms T-type calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:6090–6100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORITA H., COUSINS H., ONOUE H., ITO Y., INOUE R. Predominant distribution of nifedipine-insensitive, high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in the terminal mesenteric artery of guinea pig. Circ. Res. 1999;85:596–605. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORITA H., SHARADA T., TAKEWAKI T., ITO Y., INOUE R. Multiple regulation of nifedipine-insensitive, high voltage-activated Ca2+ current in guinea-pig mesenteric terminal arteriole. J. Physiol. 2002;539:805–816. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULVANY M.J., AALKJAR C. Structure and function of small arteries. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:921–961. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON M.T., PATLAK J.B., WORLEY J.F., STANDEN N.B. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage-dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:C3–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWCOMB R., SZOKE B., PALMA A., WANG G., CHEN X.-H., HOPKINS W., CONG R., MILLER J., URGE L., TARCZY-HORNOCH K., LOO J.A., DOOLEY D.J., NADASDI L., TSIEN R.W., LEMOS J., MILJANICH G. Selective peptide antagonist of the class E calcium channel from the venom of the tarantula Hysterocrates gigas. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15353–15362. doi: 10.1021/bi981255g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NILIUS B., PRENE J., KAMOUCHI M., VIANA F., VOETS T., DROOGMANS G. Inhibition of mibefradil, a novel calcium antagonist, of Ca2+- and volume-activated Cl− channels in macrovascular endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:547–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOONEY J.M., LAMBERT R.C., FELTZ A. Identifying neuronal non-L Ca2+ channels: more than stamp collecting. Trend. Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:363–371. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORRIS T.M., MOYA E., BLAGBROUGH I.S., ADAMS M.E. Block of high-threshold calcium channels by the synthetic polyamines sFTX-3.3 and FTX-3.3. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:939–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSTERRIEDER W., HOLCK M. In vitro pharmacologic profile of Ro 40-5967, a novel Ca2+ channel blocker with potent vasodilator but weak inotropic action. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1989;13:754–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OZAWA Y., HAYASHI K., NAGAHAMA T., FUKIWARA K., SARUTA T. Effect of T-type selective calcium antagonists in the isolated perfused hydronephrotic kidney. Hypertension. 2001;38:343–347. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERCHENET L., CLEMENT-CHOMIENNE O. Characterization of mibefradil block of the human heart delayed rectifier hKv1.5. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POTOCNIK S.J., MURPHY T.V., KOTECHA N., HILL M.A. Effects of mibefradil and nifedipine on arteriolar myogenic responsiveness and intracellular Ca2+ Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1065–1072. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCOTT R.H., SWEENEY M.I., LORBINSKY E.M., PEARSON H.A., YIMMS G.H., PULLAR I.A., WEDLEY S., DOLPHIN A.C. Actions of arginine polyamine on voltage and ligand-activated whole cell currents recorded from cultured neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;106:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TODOROVIC S.M., PEREZ-REYES E., LINGLE C.J. Anticonvulsants but not general anesthetics have differential blocking effects on different T-type current variants. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:98–108. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRIGGLE D.J. The physiological and pharmacological significance of cardiovascular T-type, voltage-gated calcium channels. Am. J. Hypertens. 1998;11 Suppl.:80S–87S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER C.D., WAARD M.D. Subunit interaction sites in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels: role in channel function. Trend. Neurosci. 1998;21:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAKAMORI M., NIIDOME T., FURUTAMA D., FURUICHI T., MIKOSHIBA K., FUJITA Y., TANAKA I., KATAYAMA K., YATANI A., SCHWARTZ A., MORI Y. Distinctive functional properties of the neuronal BII (class E) calcium channel. Receptors and Channels. 1994;2:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]