Abstract

Urotensin-II (U-II), a peptide isolated from the urophysis of teleost fish 35 years ago, is the endogenous ligand of the mammalian orphan receptor GPR14/SENR. Recently, human homologues of both the receptor (UT-II) and the peptide (hU-II) have been discovered. Following de-orphanization, hU-II was declared the ‘new endothelin' as initial studies suggested similarities between the peptides, and in isolated arteries of cynomolgus monkey U-II was a more potent constrictor than endothelin-1 (ET-1), with equal efficacy. However, effects of U-II in vascular tissue from other mammalian species are variable and although potent, U-II exhibits a lesser maximal response than ET-1. In contrast, in humans U-II has emerged as a ubiquitious constrictor of both arteries and veins in vitro and elicits a reduction in blood flow in the forearm and skin microcirculation in vivo. In addition to direct vasoconstrictor activity on smooth muscle receptors, endothelium-dependent U-II-mediated vasodilatation has also been observed. Non-vascular, peripheral actions of U-II include potent inotropy and airway smooth muscle constriction and U-II and its receptor are present throughout rat brain implying a possible neurotransmitter or neuromodulatory role in the central nervous system. U-II is proposed to contribute to human diseases including atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, pulmonary hypertension and tumour growth. The development of selective receptor antagonists should help to clarify the relative importance of hU-II as a multifunctional peptide in mammalian systems and its role in disease. What is clear is that U-II is emerging as a new and potentially important mammalian transmitter.

Keywords: Urotensin-II, orphan receptor, GPR14, SENR, UT-II, vasoconstriction, vasodilatation

Introduction

Since its discovery in 1988, endothelin-1 (ET-1) has been consistently described as the most potent vasoconstrictor yet discovered (Yanagisawa et al., 1988). ET-1 has a possibly unique ability to produce long lasting vasoconstriction both in vitro (Yanagisawa et al., 1988) and in vivo (Clarke et al., 1989; Ide et al., 1989; Weitzberg et al., 1991). It is proposed that in human vasculature ET-1, released from endothelial cells (Russell & Davenport, 1999), contributes to the maintenance of normal vascular tone by opposing vasodilatation produced by endothelium-derived mediators such as nitric oxide and prostacyclin (Haynes & Webb, 1994). The importance of ET-1 as a cardiovascular and renal peptide in humans is well established (see reviews by e.g. Miyauchi & Masaki, 1999; Miyauchi & Goto, 1999; Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001), and new physiological/pathophysiological roles are emerging in, for example, cancer (Asham et al., 2001; Nelson, 2001). At the closing session of the Sixth International Conference on Endothelin held in Montreal in 1999 the pharmacology of the human form of a phylogenetically ancient fish peptide, urotensin-II (U-II), was described. U-II was shown to contract monkey arteries even more potently than ET-1 and exhibited pronounced cardiovascular actions (Douglas et al., 2000a). This review aims to summarise recent data on the mammalian U-II system, with particular emphasis on information from human studies where available, and to compare the pharmacology of U-II to that of ET-1.

Urotensin-II – a fish peptide?

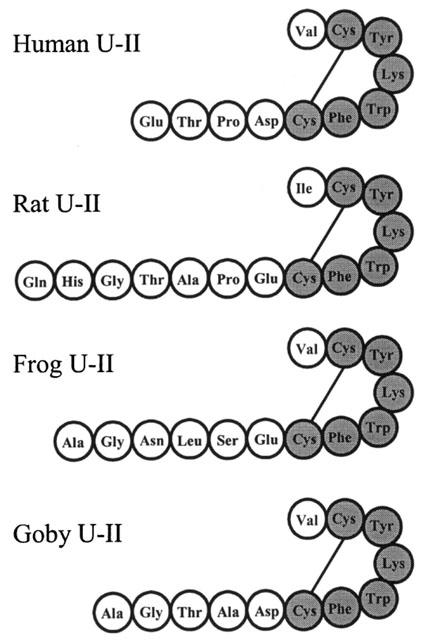

U-II, an urophysial peptide, was first characterized biologically by Bern and colleagues in 1967 (see Bern et al., 1995). This dodecapeptide (Figure 1), initially isolated from the goby, Gillichthys mirabilis, exhibited sequence similarity to somatostatin-14 and the cyclic portion of the peptide, comprising six amino acids, was highly conserved in all forms of the peptide isolated from the caudal secretory system of teleost fish (Pearson et al., 1980). The earliest described functions of U-II in fish inclued smooth muscle and vascular constriction, osmoregulation and a role as a prolactin inhibitory factor (see Bern et al., 1995). Effects of fish U-II, usually goby, on mammalian smooth muscle were subsequently reported. In contrast to smooth muscle vasoconstriction in teleosts, initial observations were of potent tetrodotoxin-insensitive relaxation of carbachol-induced tone in the mouse anococcygeus muscle (Gibson et al., 1984). In rat isolated aorta both endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and endothelium-independent vasoconstriction were detected (Gibson, 1987). Constrictor responses to U-II in rat arteries appeared, however, to be variable and highly dependent on the vascular bed (Itoh et al., 1987; 1988). In vivo, infusion of goby U-II into anaesthetized rats produced a reduction in arterial blood pressure, with reflex tachycardia (Gibson et al., 1986). Since the depressor response was partially attenuated by L-NG-monomethyl arginine (L-NMMA) and completely inhibited by indomethacin (Hasegawa et al., 1992), U-II appeared to mediate its in vivo actions via the release of endothelium-derived relaxing factors. At this time the receptor through which U-II was acting was unknown.

Figure 1.

Examples of the deduced amino acid sequences of mammalian, amphibian and fish U-II. Shaded residues are those conserved across all known species homologues of the peptide.

The orphan G-protein coupled receptor SENR is identical to rat GPR14

Interest in U-II in mammals waned until the sequencing of the human genome and the discovery of putative ‘orphan' G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). Sequences encoding one novel GPCR (Tal et al., 1995) indicated some sequence similarities with the rat somatostatin sst4 and δ-opioid receptors and a human galanin receptor. Transcript for the receptor was identified predominantly in sensory and neural tissues and therefore the receptor was named the sensory epithelium neuropeptide-like receptor (SENR) (Tal et al., 1995). Independently, a screen of a rat genomic DNA library led to the identification of a clone encoding a rat orphan GPCR, GPR14 (Marchese et al., 1995) that was identical to SENR. Both groups reported that the novel gene was intronless and encoded a 386 amino acid receptor.

Discovery of a novel human orphan GPCR

Ames et al. (1999), searching for novel human GPCRs, used rat GPR14 to probe a human genomic library and isolated a clone encoding a 389 amino acid human GPCR. Messenger RNA encoding this human receptor was abundantly expressed in heart and pancreas and also detected in brain, human atria, ventricle, aorta, and endothelial and smooth muscle cell lines. Message was not detected in venous tissue (Ames et al., 1999).

Pairing of human U-II with its receptor by the ‘reverse pharmacology' approach

Reverse pharmacology was used to screen hundreds of potential ligands against both rat GPR14 and the homologous human receptor. Only goby U-II elicited a potent response (Ames et al., 1999). A complementary DNA sequence encoding human U-II (hU-II), was subsequently identified, with the mature eleven amino acid peptide sequence identical to that reported earlier by Coulouarn et al. (1998) (Figure 1). In contrast to the wide distribution of the human U-II receptor mRNA, the peptide message was restricted to the spinal cord and medulla oblongata. As expected, hU-II stimulated a calcium response in HEK-293 cells expressing the human receptor (Ames et al., 1999) and following criteria set out by the International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification this new human receptor has been designated the UT-II receptor (Davenport & Maguire, 2000). In contrast to the limited vasoconstrictor activity of hU-II observed in rat arteries in vitro, hU-II contracted all primate arteries tested and was 10 fold more potent than ET-1 although, consistent with the lack of detectable UT-II receptor mRNA, no response was obtained in venous preparations. The effects of systemic infusion of hU-II into anaesthetized monkeys were dramatic – with dose-dependent (30–300 pmol kg−1 i.v.) increases in total peripheral resistance and left ventricular end diastolic pressure, and decreases in stroke volume, cardiac output and myocardial contractility. Unusually, compared to other vasoconstrictors such as ET-1 and angiotensin-II, heart rate and mean arterial pressure were only marginally reduced at concentrations that elicited severe systemic vasoconstriction (300 pmol kg−1). A bolus dose of 3 nmol kg−1 i.v. hU-II was sufficient to cause death. Therefore the pharmacological profile of hU-II in the monkey in vivo was strikingly different from that obtained in the rat and suggested that in this species at least U-II was the most potent vasoconstrictor discovered, superseding ET-1.

Following publication of the Nature paper by Ames et al. (1999) three independent reports of the identification of U-II as the endogenous ligand for the orphan receptor GPR14 appeared in the literature. Nothacker et al. (1999) identified a robust Ca2+ signal to bovine hypothalamic extracts in cells transiently transfected with GPR14 cDNA. The active material was peptidic. A screen of cysteine-bridge-containing peptides was carried out against GPR14 and only U-II had demonstrable biological activity at subnanomolar concentrations, with synthetic hU-II displaying the same time course for stimulation of the Ca2+ response as the active extracts. Iodinated hU-II bound with expected high affinity to membranes of cells expressing GPR14 (Kd=70 pM). Nothacker et al. (1999) also identified the presence of GPR14 mRNA in cardiovascular tissues including rat heart and aorta.

Two molecular species of U-II were isolated from porcine spinal cord (Mori et al., 1999) and release of arachidonic metabolites was demonstrated when CHO cells expressing SENR were exposed to the prepared peptide fraction (Mori et al., 1999). Using HEK-293/aeq 17 cells stably expressing GPR14, Liu et al. (1999) also demonstrated selective activation of this receptor by fish, frog and human forms of U-II. Finally, the gene coding for the human GPCR, UT-II, has been located to chromosome 17q25.3 (Protopopov et al., 2000).

Vascular responses to U-II in rat in vivo and in vitro

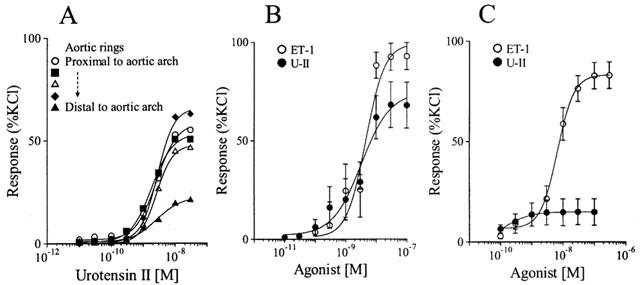

Initial studies into effects of U-II in mammals were mainly carried out in rat. Goby U-II, in vivo, produced an overall depressor response (Gibson et al., 1986; Hasegawa et al., 1992) but in vitro heterogeneity of responsiveness of arteries from different vascular beds was observed. U-II potently contracted rat thoracic aorta and carotid artery with lower maximum responses in abdominal aorta and mesenteric arteries and no response in femoral artery (Gibson, 1987; Itoh et al., 1987). Even within the thoracic aorta the maximal contraction to U-II was less robust in the distal segments compared to those proximal to the aortic arch (for example see Figure 2A). Removal of the endothelium did not influence the constrictor effect of U-II, suggesting a direct action on smooth muscle and saturation binding experiments indicated that a positive correlation existed between receptor density in different rat arteries and the degree of maximum contraction obtained in vitro (Itoh et al., 1988). Vasodilatation of the rat aorta was also reported, but was attenuated by removal of the endothelium (Gibson, 1987). The use of selective and mixed receptor antagonists, ion channel and enzyme inhibitors suggested that the contractile actions of U-II in rat thoracic aorta did not involve either the direct or indirect activation of adrenergic, muscarinic acetylcholine, 5-hydroxytryptamine or histamine receptors, tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels or the generation of products of arachidonic acid metabolism (Gibson, 1987; Itoh et al., 1987). Therefore, U-II produces both endothelium-independent vasoconstriction and endothelium-dependent vasodilatation, as does ET-1, which mediates these opposing effects through its two receptor subtypes.

Figure 2.

Variability of responsiveness of rat and human blood vessels to U-II. An example of the constrictor response to U-II in consecutive 4 mm rings of rat thoracic aorta: the maximum response to U-II diminishes with distance of aortic ring from the carotid bifurcation (A). Comparison of concentration-response curves to U-II and ET-1 in endothelium-denuded rat thoracic aorta (n=6) (B) and human coronary artery (n=6–9) as an example of the species variability in efficacy of U-II. Values are mean±s.e.mean. (see Maguire et al., 2000).

In rat isolated heart, hU-II produced an initial decrease in coronary flow followed by sustained vasodilatation that could be attenuated by inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase or nitric oxide synthase (NOS) (Katano et al., 2000). In a more detailed study, hU-II produced an increase in perfusion pressure, maximal at 100 nM, with the late depressor response observed at higher concentrations. Although potent (EC50≈2.5 nM), the increase in pressure to hU-II (12 mmHg) was less than one fifth that produced by ET-1 (Gray et al., 2001). Comparable data were obtained in isolated rat coronary artery, although in rat mesenteric resistance and basilar arteries only endothelium-dependent relaxations were observed (Bottrill et al., 2000). Human U-II also contracted rat main pulmonary arteries (EC50≈3 nM) but not smaller diameter vessels (Maclean et al., 2000) with hU-II four times more potent than ET-1, although the maximum response to U-II was less than 50% of that to ET-1. In common with other vasoconstrictors, contraction to U-II was potentiated by low concentrations of ET-1 (Maclean et al., 2000). Interestingly, whilst the potency of hU-II in pulmonary arteries from chronic hypoxic rats was not different from controls there was a significant increase in the maximum response to hU-II in animals with pulmonary hypertension suggesting a possible pathophysiological role in this disease (Maclean et al., 2000).

The apparent paradox of the in vivo depressor activity of goby U-II in rat and the early reports that in vitro the predominant response to goby and hU-II in isolated blood vessels was vasoconstriction has been addressed using hU-II in conscious, unrestrained animals (Gardiner et al., 2001). Human U-II (300 and 3000 pmol kg−1) elicited fast onset vasodilatation of the mesenteric vascular bed preceding more prolonged vasodilatation in the hindquarters. Dose-dependent tachycardia was associated with significant reduction in mean arterial blood pressure only at the highest concentration and at 3000 pmol kg−1 hU-II, renal blood flow was reduced without effect on renal vascular conductance. There was no difference between rat and hU-II (Gardiner et al., 2001). It is clear from this study that the main action of hU-II in the rat in vivo is vasodilatation. The absence of significant pressor activity in vivo may reflect the fact that robust constriction in vitro is observed in large blood vessels (e.g. aorta) that do not contribute substantially to blood pressure control and also that the constrictor activity of U-II may be modified by the presence of a functional endothelium.

Variable pharmacological profile of hU-II in mammalian species

The variability in response of rat arteries to U-II was seen in other species. In this respect U-II differs markedly from ET-1 since ET-1 contracts all arteries and veins tested. Continuing their investigations following the pairing of hU-II and its receptor, Douglas et al. (2000b) determined the effect of hU-II on vascular tissues from rat, mouse, dog, pig, marmoset and cynomolgus monkey. The rat data obtained with hU-II were comparable to those previously described for goby U-II by others. An example of the comparative vasoconstrictor responses to hU-II and ET-1 in rat aorta is shown in Figure 2B. Mouse aorta was unresponsive to the peptide. In dog, hU-II was devoid of any significant activity in arteries or veins other than coronary artery. In pig, the data were more complicated. No vasoconstriction was obtained in coronary, renal, mammary or carotid arteries or saphenous vein. In other vascular beds, hU-II elicited some response, but not in all vessels tested. Similar variability in reactivity was obtained in blood vessels of the marmoset (New World primate). The only species tested in which hU-II was consistently a potent and efficacious vasoconstrictor was cynomolgus monkey (Old World primate). Human U-II contracted coronary, pulmonary, renal, femoral, mesenteric, internal mammary and basilar arteries and both thoracic and abdominal aorta (EC50 0.1–1.1 nM). Where determined, hU-II exhibited between 10 and 20 fold higher potency than ET-1. Constrictor responses were also reported in pulmonary arteries and airway smooth muscle of cynomolgus monkey from different regions of the lung (Hay et al., 2000). However, as in other species, hU-II was without notable effect in venous preparations, with modest vasoconstriction observed in pulmonary vein (Douglas et al., 2000b; Hay et al., 2000) and only in tissue taken proximal, but not distal, to the atria (Hay et al., 2000). In airways, whilst potency of hU-II was consistent (EC50≈0.6–2.5 nM) the maximum response to hU-II increased from upper trachea to tertiary bronchus and there was marked inter-animal variation in response (Hay et al., 2000). In rabbit, potent vasoconstriction was obtained to hU-II in thoracic aorta and coronary artery, but no response in pulmonary or ear arteries or ear vein (Saetrum Opgaard et al., 2000). Overall these data implied that in mammals hU-II is a potent (EC50 values in the range 0.1–3 nM), predominantly arterio-selective constricting factor. The most obvious explanation for the variability of the responses obtained is that the level of receptor expression is low and possibly absent or below the density required to elicit a vasoconstrictor response to the peptide in vascular beds from some species or indeed in individual animals.

Human cardiovascular pharmacology of U-II

The overt species variability in responsiveness of blood vessels to hU-II has increased the requirement for human studies to clarify the potential importance of this peptide to human cardiovascular physiology and its role in disease. What is apparent is that, like ET-1, hU-II is emerging as a ubiquitous constrictor of both human arteries and veins in vitro with no evidence of the highly localized expression of U-II receptors in a particular anatomical region of a vascular bed as there is in rat aorta, for example. We have shown that human U-II produced vasoconstriction in human coronary, mammary and radial arteries and saphenous and umbilical veins (Maguire et al., 2000), however, coronary and mammary arteries from some patients were unresponsive to hU-II. In both arterial and venous tissues EC50 values were subnanomolar (≈0.1–0.5 nM) and between 10 and 50 times more potent than ET-1. Despite its potency, the maximum response to hU-II was low compared to ET-1 (see Figure 2C) although comparable to that of angiotensin-II. In agreement with these results, hU-II contracted coronary artery from one of three patients to a lesser extent than ET-1 (Russell et al., 2001). Contractile responses to hU-II were also reported in small muscular pulmonary arteries (internal diameter ≈250 μm) in vitro, from three out of ten patients tested, although only in the presence of L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester. Preconstriction of pulmonary arteries with ET-1 failed to unmask a more robust constrictor response or dilatation to hU-II (Maclean et al., 2000).

There has been one report of hU-II relaxation of human vessels. Resistance pulmonary and mesenteric arteries did not contract to hU-II but potent vasodilatation (IC50 values of 0.04 nM and 0.05 nM, respectively) was obtained following preconstriction with ET-1. In pulmonary artery, hU-II was as effective as adrenomedullin and more potent than acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside (Stirrat et al., 2001). One study reported no effect of hU-II in human arteries and veins (Hillier et al., 2001). The authors suggested that although tissue was obtained from patients with coronary heart disease, sufficient endothelial function remained for hU-II vasodilatation to mask any constrictor response. However, in contrast to the potent vasodilatory actions of hU-II in human pulmonary and abdominal resistance arteries (Stirrat et al., 2001), no such effect was seen in the subcutaneous arteries (Hillier et al., 2001). It had been hoped that the impressive pharmacological profile of hU-II in cynomolgus monkey would be predictive, at least to some degree, of that observed in man. Clearly, it is apparent that the in vitro pharmacological activity of hU-II in the human vasculature differs greatly from that in other species and reinforces the need for in vitro and in vivo studies in man.

The in vivo actions of hU-II in healthy volunteers have also been investigated. In the microcirculation of human skin, intradermal injections (10 μl) of hU-II (0.3–100 pmol 10 μl−1) produced a dose-dependent reduction in blood flow with sustained vasoconstriction at the highest dose (Leslie et al., 2001). Similarly, a significant, dose-dependent decrease in blood flow was obtained in the human forearm in vivo following infusion of hU-II (0.1, 1, 10, 100 and 300 pmol min−1), with each dose administered for 15 min at 1 ml min−1. A maximum reduction in forearm blood flow of 31% was achieved, with no significant change in flow recorded in the contralateral non-infused arm (Böhm & Pernow, 2002). This group previously showed that forearm blood flow is also attenuated by infusions of low concentrations of ET-1 (3–10 pmol min−1), although as reported in human in vitro studies the maximal responses to ET-1 (60% reduction in flow) was greater than that achieved with hU-II (Pernow et al., 1991). These experiments indicate that the predominant response to hU-II in man in vivo, at least in these vascular beds, is vasoconstriction. In a similar investigation no vasoconstrictor effect on human forearm was observed in patients receiving 30 and 100 pmol min−1 or 100 and 300 pmol min−1 hU-II, each dose given for 20 min at 1 ml min−1 (Wilkinson et al., 2002). Pressor activity was not unmasked following administration of aspirin and ‘clamping' of the NO system using L-NMMA and sodium nitroprusside, despite the high levels of hU-II achieved in the plasma. Some methodological differences between the two studies may account for the observed discrepancy. More detailed studies on the systemic effects of hU-II and the development of antagonists for the UT-II receptor will allow the importance of hU-II as a regulator of human vascular tone to be elucidated.

In addition to its vascular effects, hU-II has cardiostimulant properties in human heart in vitro (Russell et al., 2001). In isolated, paced human right atrial trabeculae the peptide increased force of contraction more potently than ET-1 (EC50 value ≈0.3 nM and ≈3.0 nM, respectively) making it the most potent inotropic agent described. Unlike ET-1, which increased time to 50% relaxation and induced spontaneous arrhythmogenic activity in 70% of atrial tissues (Burrell et al., 2000), hU-II did not affect time either to 50% relaxation or to reach peak force and produced spontaneous contractions in only 12% of atria. A maximal concentration of hU-II also increased force of contraction in human right ventricular trabeculae although to a lesser extent than in atria (Russell et al., 2001). These direct effects of hU-II on human heart contrast with those reported in monkey following systemic administration where myocardial contractility was reduced (Ames et al., 1999), although effects of hU-II on the human heart in vivo have yet to be determined.

Structure activity studies

Urotensin-II isoforms from mammals, amphibians and fish contain a conserved C-terminal cyclic hexapeptide sequence (see Douglas & Ohlstein, 2000; Figure 1). Despite low sequence homology in the N-terminus, different isoforms exhibit similar potencies both in vitro (Ames et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1999; Mori et al., 1999; Russell et al., 2001) and in vivo (Gardiner et al., 2001) suggesting that the majority of biological activity resides in the C-terminus. In rat aorta, goby U-II5-12 competed for [125I]-U-II binding and elicited vasoconstriction with equal potency to the full length peptide, whilst U-II6–12 was six times less potent and goby U-II6–11 was essentially inactive (Itoh et al., 1987; 1988). Urotensin-115–12 is therefore the minimum sequence required for full biological activity.

Localization of hU-II mRNA

By dot blot analysis of human tissues, significant expression of prepro-hU-II mRNA appeared to be limited to spinal cord, medulla oblongata and kidney (Ames et al., 1999; Nothacker et al., 1999), although this method only investigates restricted tissue homogenates from one individual and gives no information on cellular localization. The dot blot data were consistent with that reported for frog (Chartrel et al., 1996; Coulouarn et al., 1998) and rodents (Coulouarn et al., 1999), and in the developing rat spinal cord U-II mRNA was detected in sacral motor neurones as early as E10 (Coulouarn et al., 2001). Low levels of hybridization signal could also be detected in human peripheral tissues including spleen, prostate, pituitary, thymus and adrenal gland (Coulouarn et al., 1998) and, using RT–PCR, hU-II mRNA was found to be abundantly expressed in pituitary, adrenal gland, placenta, colonic mucosa, kidney, atrium (Matsushita et al., 2001; Totsune et al., 2001) and to a lesser extent in vascular tissue such as aorta, thoracic artery and saphenous vein (Matsushita et al., 2001). Autoradiographical analysis identified prepro-hU-II mRNA in cervical sections of human spinal cord located specifically to a sub-population of motor neurones (Coulouarn et al., 1998) and in motor nuclei of the rat brain, including the motor trigeminal and abducens nuclei, and ventral horn of the rat spinal cord (Coulouarn et al., 1999).

Localization of hU-II peptide

Limited immunocytochemical studies have been carried out to localize the hU-II peptide. Human U-II-like immunoreactivity (hU-II-LI) was originally reported in human and monkey vasculature with diffuse staining in cardiac myocytes, intense staining in the macrophage and smooth muscle-rich region of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque tissue and immunoreactivity also present in ventral horn motor neurones of spinal cord and acinar cells of the thyroid (Ames et al., 1999). More recently, we have identified hU-II-LI in endothelial cells of human aorta, epicardial coronary artery as well as intramyocardial vessels with diameters (60–120 μM) typical of resistance arteries. No staining was evident over cardiac myocytes or vascular smooth muscle cells. In coronary arteries with atherosclerotic lesions hU-II-LI was detected within the region of infiltrating macrophages of the plaque but not to contractile smooth muscle cells of the media or proliferated smooth muscle cells of the thickened intima (Kuc et al., 2001). Interestingly, in rat brainstem and ventral horn of spinal cord U-II-LI is predominantly co-localized to choline acetyl transferase (ChAt)-positive neurones (Dun et al., 2001) indicating the presence of U-II in cholinergic motor neurones.

Distribution of GPR14 and UT-II receptors

In contrast to the peptide, dot blot analysis of human tissues showed both central and peripheral expression of mRNA encoding the UT-II receptor (Ames et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1999), with similar findings for the SENR/GPR14 receptor in bovine (Tal et al., 1995) and rodent tissues (Tal et al., 1995; Liu et al., 1999; Nothacker et al., 1999; Gartlon et al., 2001). In human tissues, expression of UT-II mRNA was confirmed by RT–PCR in brain cortex, hypothalamus, medulla oblongata, pituitary, kidney, adrenal gland, placenta, colonic mucosa, atrium and ventricle of heart, thoracic artery and aorta (Matsushita et al., 2001; Totsune et al., 2001). Distribution of GPR14 and UT-II receptor proteins has also been determined using radiolabelled goby or human U-II ([125I]-U-II). In rat thoracic aorta, goby [125I]-U-II exhibited high affinity (KD≈6 nM), saturable binding. Binding density to rat arteries was greatest in thoracic aorta (≈20 fmol mg−1 protein) with lower levels in abdominal aorta and mesenteric artery (6 and 2 fmol mg−1 protein respectively) (Itoh et al., 1988) and correlated to maximal contractile activity shownby the unlabelled peptide in vitro. Comparable binding data were obtained in rat cardiac membranes (KD=0.35 nM, Bmax≈4 fmol mg−1 protein) (Ames et al., 1999). Using in situ hybridization in rat brain, Clark and colleagues identified GPR14 mRNA in the pedunculopontine tegmental (PPTg) and lateral dorsal tegmental (LDTg) nuclei that are associated with motor function, arousal and sleep. Levels were too low for detection or absent in other brain regions. Within these mesopontine tegmental nuclei U-II receptor mRNA co-localized to cholinergic neurones (i.e. ChAt-positive) (Clark et al., 2001). Interestingly, using receptor autoradiography, [125I]-U-II binding sites were identified in many additional brain regions, including the lateral septal, medial habenular and interpeduncular nuclei, although for the most part these were areas receiving axonal projections from the mesopontine PPTg or LDTg nuclei (Clark et al., 2001). Differences in the sensitivity between the techniques may be sufficient to explain the different distribution patterns obtained using the in situ hybridization and radioligand binding assays and indeed a wider expression of UT-II mRNA was reported by others in brain using dot blot analysis and RT–PCR (Tal et al., 1995; Ames et al., 1999). One other explanation put forward by the authors is that the binding sites, detected in areas in which no message was apparent, may represent presynaptic U-11 receptors on axonal projections from the PPTg or LDTg nuclei. The presence of U-II peptide in cholinergic neurones of the rat brain stem may also indicate that these are presynaptic U-II autoreceptors, as has been suggested for motor neurones of the spinal cord (Liu et al., 1999). In sections of rat medial habenular binding of [125I]-U-II was saturable, with the expected subnanomolar KD value, but density of binding was low (≈4 fmol mg−1 protein) (Clark et al., 2001).

Distribution of the human UT-II receptor

Using for the first time iodinated hU-II, autoradiographical analysis of human [125I]-U-II binding in human tissues reported highest levels (≈30 amol mm−2) in skeletal muscle and cerebral cortex. Saturation binding experiments in skeletal muscle indicated a single (Hill slope close to one), high affinity binding site with a low receptor density of 2 fmol mg−1 protein. Binding sites were also present in the medial layer of human coronary artery (with no difference in density apparent in normal and atherosclerotic vessels) kidney cortex, myocytes of the left ventricle and pulmonary arteries and bronchioles (Maguire et al., 2000). The density of U-II receptors measured in rat brain, arteries and human skeletal muscle was comparable to that determined for other vasoactive peptides such as ET-1 (Davenport et al., 1995; Bacon et al., 1996), angiotensin II (Wharton et al., 1998) and thromboxane A2 (Katugampola & Davenport, 2001) in, for example, human arteries. However, compared to U-II, much greater densities of ET receptors are present in kidney, lung and brain.

Central effects of U-II in rats

The presence of both U-II-LI and U-II receptors in rat brain imply a neurotransmitter/neuromodulatory role in the central nervous system. Following intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of hU-II (10 μg), rats exhibited a prolonged increase in rearing, grooming and motor activity with decreased periods of inactivity. This behaviour was accompanied by increased plasma prolactin and thyroid stimulating hormone with no alteration in the ratio of dopamine or 5-hydroxytryptamine to their metabolites in frontal cortex, hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, striatum or hippocampus (Gartlon et al., 2001). The responses to i.c.v. hU-II were consistent with the presence of U-II receptor mRNA (Ames et al., 1999; Clark et al., 2001) and protein (Clark et al., 2001) in brain areas associated with locomotor activity, arousal and control of endocrine function.

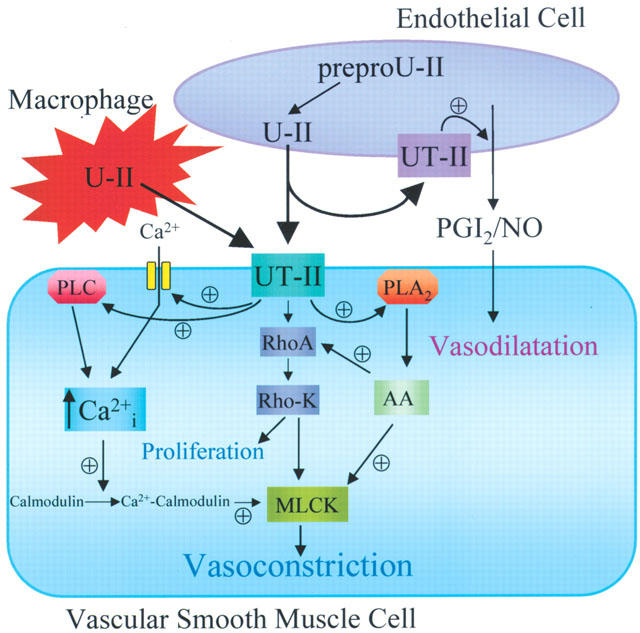

Signal transduction pathways

A role for calcium, calmodulin and phospholipase A2 in the vasoconstrictor response to U-II were inferred from the early in vitro experiments (Gibson, 1987; Itoh et al., 1987; 1988; Gibson et al., 1988) and receptor expression systems linked to calcium mobilization (Ames et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1999; Nothacker et al., 1999) and arachidonic acid metabolism (Mori et al., 1999) were used to identify U-II as the endogenous ligand for GPR14 and UT-II receptors. In rabbit aorta, the maximum contractile response to hU-II was significantly attenuated by the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor 2-nitro-4-carboxyphenyl-N, N,-diphenylcarbamate (NCDC) with no effect of indomethacin. In slices of the same preparation, hU-II-stimulated accumulation of [3H]-inositol phosphates, that was also inhibited by NCDC (Saetrum Opgaard et al., 2000). These data indicate that hU-II activation of its receptor is linked to PLC stimulated phosphoinositide turnover, consistent with the coupling of U-II receptors to G-proteins of the ubiquitous Gq/11 family. Furthermore, in rat arterial smooth muscle, both hU-II-mediated vasoconstriction and proliferation are associated with activation of the small GTPase RhoA and its downstream effector Rho-kinase (Sauzeau et al., 2001). In these experiments vasoconstriction resulted from both a rise in intracellular calcium and calcium sensitization of the contractile proteins, as previously suggested by Gibson (1987) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scheme summarizing the known intracellular pathways that mediate the vascular responses of U-II. U-II released from endothelial cells, or additionally in atherosclerosis from macrophages, acts on smooth muscle receptors to mediate vasoconstriction and proliferation or on endothelial cell receptors to release vasodilators such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2). In smooth muscle cells UT-II receptors are linked to increases in intracellular calcium via activation of PLC and L-type calcium channels, generation of arachidonic acid (AA) and its metabolites via activation of PLA2 and stimulation of the small G-protein RhoA and its downstream effector Rho kinase (Rho-K). Direct activation of Ca2+ sensitive myosin light chain (MLC) kinase, Ca2+ sensitization of MLC kinase by Rho and AA and generation of constrictor AA metabolites may all contribute to U-II-mediated vasoconstriction. ⊕ - Activation.

Plasma levels of U-II in humans

Following development of radioimmunoassays for the detection of U-II (Winter et al., 1999) levels of 5±1 fmol ml−1 have been measured in plasma from healthy individuals (Totsune et al., 2001). These levels are relatively low, suggesting that U-II is not predominantly a circulating hormone. They are, however, comparable to normal circulating levels of ET-1, which acts principally in a paracrine/autocrine manner and are consistent with hU-II functioning as an endothelium-derived mediator. Plasma ET levels increase in cardiovascular disease and conditions such as diabetes mellitus and trauma (see Huggins et al., 1993). Similarly, significantly increased levels of hU-II were present in plasma from patients with renal failure (2–3 fold greater than control), with those on dialysis recording the highest concentrations (Totsune et al., 2001). Augmented hU-II levels in plasma of patients with cirrhosis (Heller et al., 2001) have also been reported. The increased plasma hU-II in renal failure patients may reflect reduced clearance by the kidneys, but increased production of U-II in disease cannot be discounted. Indeed, mRNA for hU-II and its receptor are present in human kidney (Matsushita et al., 2001), suggesting that the kidney may be one source of hU-II. The amount of hU-II detected in urine was significantly elevated in patients with essential hypertension and those with abnormal renal tubules (but not with glomerular disease) compared to healthy controls. The observation that the fractional excretion of U-II exceeded glomerular filtration rate further indicates a renal source of U-II (Matsushita et al., 2001).

Human U-II and disease

To date most research into the role of hU-II in mammalian systems has focused on the cardiovascular effects of the peptide. Data suggest that hU-II has potential as a modulator of vascular tone and cardiac function and that alterations in the hU-II system may contribute to, or result from, cardiovascular disorders. It is unclear at present whether the predominant action of hU-II in human disease will be protective or deleterious. In human atherosclerotic coronary artery lesions the additional macrophage source of hU-II (Kuc et al., 2001) may contribute not only to overall vasoconstriction in the diseased vasculature but also to progression of the lesion, since hU-II has been shown to be mitogenic. In cultured vascular smooth muscle cells, hU-II stimulated proliferation (Sauzeau et al., 2001; Watanabe et al., 2001a, b) and actin cytoskeleton organization (Sauzeau et al., 2001). Its effects were synergistic with other mitogens such as mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein (Watanabe et al., 2001a) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (Watanabe et al., 2001b). U-II antagonists may therefore be beneficial in conditions characterized by vasospasm or vascular remodelling. Similarly, in addition to enhanced hU-II vasoconstrictor responses in pulmonary arteries from rats subjected to chronic hypoxia (Maclean et al., 2000), cardiac hypertrophy resulting from the pulmonary hypertension was associated with an increase in both cardiac tissue U-II levels and U-II receptor density, although binding affinity was reduced compared with control animals (Zhang et al., 2002). In this model, plasma levels of U-II were unchanged by chronic hypoxia suggesting a paracrine or autocrine role for the peptide. Human U-II-induced hypertrophic responses were also observed in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, with hU-II stimulating MAP kinase activity, expression of foetal genes, protein synthesis and morphological changes (Zou et al., 2001). Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells, exposed to high shear stress to reproduce the increased pulmonary pressure associated with congestive heart failure, showed a decrease in U-II mRNA expression and release of the peptide in contrast to an increase in gene expression and release of ET-1 (Dschietzig et al., 2001). The significance of this observation will be more apparent when the physiological role of U-II in bovine pulmonary vasculature (i.e. vasoconstrictor or vasodilator) is clarified. Finally, consistent with its vasoactive and proliferative properties, U-II peptide and receptor mRNAs have been identified in human tumour cell lines, with the secreted peptide detectable in the culture medium from SW-13 adrenocortical carcinoma cells (Takahashi et al., 2001). This particular cell line also secretes ET-1 and the vasodilator adrenomedullin but not other vasoactive peptides such as urocortin, calcitonin gene-related peptide or neuropeptide Y. Thus a role for U-II in tumour growth may be inferred.

Conclusion

Urotensin-II is the latest of an increasing number of endogenous peptides, including nociceptin/orphanin FQ, apelin, ghrelin and the orexins, that have been successfully paired with orphan GPCRs using the reverse pharmacology strategy. It is already apparent that hU-II exhibits diverse effects in mammals both peripherally and centrally, with sufficient data to suggest the emergence of a new transmitter system. In animals, the vasoactive responses to U-II are variable with differences observed between species, between different vascular beds in a single species or indeed in the expression of receptors in anatomically distinct regions of a particular blood vessel, as observed in rat aorta. In contrast, in humans vascular responses to hU-II are more consistent with hU-II acting as a vasoconstrictor peptide localized to the endothelium, like ET-1. Indeed, hU-II exhibits a similar cardiovascular pharmacological/physiological profile to ET-1; both peptides mediate vasoconstriction and vasodilatation, cell proliferation, cardiac hypertrophy and modulate cardiac function. However, unlike ET-1, the maximum constrictor response to hU-II is relatively low. The correlation of binding density to constrictor response observed in rats suggests that regulation of hU-II function may be at the level of receptor expression, with small changes in receptor densities, perhaps in response to alterations in peptide levels in disease, resulting in pathophysiological effects. We await the development and widespread use of UT-II receptor antagonists to further elucidate the role of the hU-II system, particularly in human diseases such as atherosclerosis and heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ChAt

choline acetyl transferase

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- hU-II

human urotensin-II

- hU-II-LI

human U-II-like immunoreactivity

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- NDC

2-nitro-4-carboxyphenyl-N, N-diphenylcarbamate

- LDTg

lateral dorsal tegmental

- L-NAME

L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester

- L-NMMA

L-NG-monomethyl arginine

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PPTg

pedunculopontine tegmental

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- SENR

sensory epithelium neuropeptide-like receptor

- U-II

urotensin-II

References

- AMES R.S., SARAU H.M., CHAMBERS J.K., WILLETTE R.N., ALYAR N.V., ROMANIC A.M., LOUDEN C.S., FOLEY J.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., AO Z., DISA J., HOLMES S.D., STADEL J.M., MARTIN J.D., LIU W.-S., GLOVER G.I., WILSON S., MCNULTY D.E., ELLIS C.E., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., SHABON U., TRILL J.J., HAY D.W.P., OLSTEIN E.H., BERGSMA D.J., DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoconstrictor and agonist for the orphan receptor GPR14. Nature. 1999;401:282–286. doi: 10.1038/45809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASHAM E., SHANKAR A., LOIZIDOU M., FREDERICKS S., MILLER K., BOULOS P.B., BURNSTOCK G., TAYLOR I. Increased endothelin-1 in colorectal cancer and reduction of tumour growth by ET(A) receptor antagonism. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;85:1759–1763. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACON C.R., CARY N.R.B., DAVENPORT A.P. Endothelin peptides and receptors in human atherosclerotic coronary artery and aorta. Circ. Res. 1996;79:794–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERN H.A., PEARSON D., LARSON B.A., NISHIOKA R.S. Neurohormones from fish tails: the caudal neurosecretory system. I. “Urophysiology” and the caudal neurosecretory system of fishes. Recent Prog. Hormone Res. 1995;41:533–552. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571141-8.50016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM F., PERNOW J. Urotensin II evokes potent vasoconstriction in humans in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:25–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOTTRILL F.E., DOUGLAS S.A., HILEY C.R., WHITE R. Human urotensin-II is an endothelium-dependent vasodilator in rat small arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1865–1870. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURRELL K.M., MOLENAAR P., DAWAON P.J., KAUMANN A.J. Contractile and arrhythmic effects of endothelin receptor agonists in human heart in vitro: blockade with SB 209670. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2000;292:449–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHARTREL N., CONLON J.M., COLLIN F., BRAUN B., WAUGH D., VALLARINO M., LACHRICHI S.L., RIVIER J.E., VAUDRY H. Urotensin II in the central system of the frog Rana ridibunda: Immunohistochemical localization and biochemical characterization. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;364:324–339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960108)364:2<324::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK S.D., NOTHACKER H.-P., WANG Z., SAITO Y., LESLIE F.M., CIVELLI O. The urotensin II receptor is expressed in the cholinergic mesopontine tegmentum of the rat. Brain Res. 2001;923:120–127. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARKE J.G., BENJAMIN N., LARKIN S.W., WEBB D.J., DAVIES G.J., MASERI A. Endothelin is a potent long-lasting vasoconstrictor in men. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257:H2033–H2035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., FERNEX C., JEGOU S., HENDERSON C.E., VAUDRY H., LIHRMANN I. Specific expression of the urotensin II gene in sacral motoneurons of developing rat spinal cord. Mech. Develop. 2001;101:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., JEGOU S., TOSTIVINT H., VAUDRY H., LIHRMANN I. Cloning, sequence analysis and tissue distribution of the mouse and rat urotensin II precursors. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., LIHRMANN I., JEGOU S., ANOUAR Y., TOSTIVINT H., BEAUVILLAIN J.-C., CONLON J.M., BERN H.A., VAUDRY H. Cloning of the cDNA encoding the urotensin II precursor in frog and human reveals intense expression of the urotensin II gene in motoneurons of the spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., MAGUIRE J.J. Urotensin II: fish neuropeptide catches orphan receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:80–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., O'REILLY G., KUC R.E. Endothelin ETA and ETB mRNA and receptors expressed by smooth muscle in the human vasculature: majority of the ETA sub-type. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1110–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., ASHTON D.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., OHLSTEIN D.H., RUFFOLO M.R., OHLSTEIN E.H., AIYAR N.V., WILLETTE R.N. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoactive peptide: pharmacological characterization in rat, mouse, dog and primate. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000a;36 Suppl. 1:S163–S166. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200036051-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H. Human urotensin-II, the most potent mammalian vasoconstrictor identified to date, as a therapeutic target for the management of cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., SULPIZIO A.C., PIERCY V., SARAU H.M., AMES R.S., AIYAR N.V., OHLSTEIN E.H., WILLETTE R.N. Differential vasoconstrictor activity of human urotensin-II in vascular tissue isolated from the rat, mouse, dog, pig, marmoset and cynomolgus monkey. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000b;131:1262–1274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DSCHIETZIG T., RICHTER C., BARTSCH C., BOHME C., HEINZE D., OTT F., ZARTNACK F., BAUMANN G., STANGL K. Flow-induced pressure differentially regulates endothelin-1, urotensin-II, adrenomedullin, and relaxin in pulmonary vascular endothelium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;289:245–251. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUN S.L., BRAILOIU G.C., YANG J., CHANG J.K., DUN N.J. Urotensin II-immunoreactivity in the brainstem and spinal cord of the rat. Neurosci. Letts. 2001;305:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., MARCH J.E., KEMP P.A., DAVENPORT A.P., BENNET T. Depressor and regionally-selective vasodilator effects of human and rat urotensin II in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:1625–1629. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARTLON J., PARKER F., HARRISON D.C., DOUGLAS S.A., ASHMEADE T.E., RILEY G.J., HUGHES Z.A., TAYLOR S.G., MUNTON R.P., HAGAN J.J., HUNTER J.A., JONES D.N.C. Central effects of urotensin-II following ICV administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:426–433. doi: 10.1007/s002130100715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON A. Complex effects of Gillichthys urotensin II on rat aortic strips. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;91:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb09000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON A., BERN H.A., GINSBURG M., BOTTING J.H. Neuropeptide-induced contraction and relaxation of the mouse anococcygeus muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984;81:625–629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON A., CONYERS S., BERN H.A. The influence of urotensin-II on calcium flux in rat aorta. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1988;40:893–895. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb06298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON A., WALLACE P., BERN H.A. Cardiovascular effects of urotensin-II in anesthetized and pithed rats. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1986;64:435–439. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(86)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAY G.A., JONES M.R., SHARIF I. Human urotensin-II increases coronary perfusion pressure in the isolated rat heart. Potentiation by nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase inhibition. Life Sci. 2001;69:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASEGAWA K., KOBAYASHI Y., KOBAYASHI H. Vasodepressor effects of urotensin-II in rats. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 1992;14:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- HAY D.W.P., LUTTMANN M.A., DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II is a potent spasmogen of primate airway smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:10–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYNES W.G., WEBB D.J. Contribution of endogenous generation of endothelin-1 to basal vascular tone. Lancet. 1994;344:852–854. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELLER J., SCHEPKE M., NEEF M., WOITAS R.P., SAUERBRUCH T. Increased urotensin II plasma levels in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatology. 2001;34 Suppl. 1:18–19. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLIER C., BERRY C., PETRIE M.C., O'DWYER P.J., HAMILTON C., BROWN A., MCMURRAY J. Effects of urotensin-II in human arteries and veins of varying calibre. Circulation. 2001;103:1378–1381. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.10.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGGINS J.P., PELTON J.T., MILLER R.C. The structure and specificity of endothelin receptors: their importance in physiology and medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993;59:55–123. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90041-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IDE K., YAMAKAWA K., NAKAGOMI T., SASAKI T., SAITO I., KURIHARA H., YOSIZUMI M., YAZAKI Y., TAKAKURA K. The role of endothelin in the pathogenesis of vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neurol. Res. 1989;11:101–104. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1989.11739870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITOH H., ITOH Y., RIVER J., LEDERIS K. Contraction of major artery segments of rat by fish neuropeptide urotensin II. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;252:R361–R366. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.2.R361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITOH H., MCMASTER D., LEDERIS K. Functional receptors for fish neuropeptide urotensin II in major rat arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;149:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATANO Y., ISHIHATA A., AITA T., OGAKI T., HORIE T. Vasodilator effect of urotensin II, one of the most potent vasoconstricting factors, on rat coronary arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;402:209–211. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATUGAMPOLA S.D., DAVENPORT A.P. Thromboxane receptor density is increased in human cardiovascular disease with evidence for inhibition at therapeutic concentrations by the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1385–1392. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEDZIERSKI R.M., YANAGISAWA M. Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease. Annual Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:851–876. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUC R.E., MAGUIRE J.J., DAVENPORT A.P. Urotensin-II is a potent constrictor of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries with immunoreactive peptide localised to the atherosclerotic plaque. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:75. [Google Scholar]

- LESLIE S.J., DENVIR M., WEBB D.J. Human urotensin II causes vasoconstriction in the human skin microcirculation. Circulation. 2001;102 Suppl. II:542. [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q., PONG S.-S., ZENG Z., ZHANG Q., HOWARD A.D., WILLIAMS D.L., JR, DAVIDOFF M., WANG R., AUSTIN C.P., MCDONALD T.P., BAI C., GEORGE S.R., EVANS J.F., CASKEY C.T. Identification of urotensin II as the endogenous ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor GPR14. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;266:174–178. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLEAN M.R., ALEXANDER D., STIRRAT A., GALLAGHER M., DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H., MORECROFT I., POLLAND K. Contractile responses to human urotensin-II in rat and human pulmonary arteries: effect of endothelial factors and chronic hypoxia in rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:201–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGUIRE J.J., KUC R.E., DAVENPORT A.P. Orphan-receptor ligand human urotensin II: receptor localization in human tissues and comparison of vasoconstrictor responses with endothelin-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:441–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCHESE A., HEIBER M., NGUYEN T., HENG H.H.Q., SALDIVA V.R., CHENG R., MURPHY P.M., TSUI L.-C., SHI X., GREGOR P., GEORGE S., O'DOWD B.F., DOCHERTY J.M. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of three novel genes, GPR9, GPR10 and GPR14, encoding receptors related to interleukin 8, neuropeptide Y and somatostatin receptors. Genomics. 1995;29:335–344. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUSHITA M., SHICHIRI M., IMAI T., IWASHINA M., TANAKA H., TAKASU N., HIRATA Y. Co-expression of urotensin-II and its receptor (GPR14) in human cardiovascular and renal tissues. J. Hypertens. 2001;19:2185–2190. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAUCHI T., GOTO K. Heart failure and endothelin receptor antagonists. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAUCHI T., MASAKI T. Pathophysiology of endothelin in the cardiovascular system. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1999;61:391–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORI M., SUGO T., ABE M., SHIMOMURA Y., KURIHARA M., KITADA C., KIKUCHI K., SHINTANI Y., KUROKAWA T., ONDA H., NISHIMURA O., FUJINO M. Urotensin II is the endogenous ligand of a G-protein-coupled orphan receptor, SENR (GPR14) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:123–129. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON J.B. Endothelin receptor antagonists in the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2001;49:91–92. doi: 10.1002/pros.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOTHACKER H.-P., WANG Z., MCNEILL A.M., SAITO Y., MERTEN S., O'DOWD B., DUCKLES S.P., CIVELLI O. Identification of the natural ligand of an orphan receptor G-protein-coupled receptor involved in the regulation of vasoconstriction. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:383–385. doi: 10.1038/14081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON D., SHIVELY J.E., CLARK B.R., GESCHWIND I.I., BARKLEY M., NISHIOKA R.S., BERN H.A. Urotensin II: a somatostatin-like peptide in the caudal neurosecretory system of fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1980;77:5021–5024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERNOW J., HEMSEN A., LUNDBERG J.M., NOWAK J., KAIJSER L. Potent vasoconstrictor effects and clearance of endothelin in the human forearm. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1991;141:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROTOPOPOV A., KASHUBA V., PODOWSKI R., GIZATULLIN R., SONNHAMMER E., WAHLESTEDT C., ZABAROVSKY E.R. Assignment of the GPR14 gene coding for the G-protein-coupled receptor 14 to human chromosome 17q25.3 by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 2000;88:312–313. doi: 10.1159/000015516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., DAVENPORT A.P. Secretory pathways in endothelin synthesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:391–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., MOLENAAR P., O'BRIEN D.M. Cardiostimulant effects of urotensin-II in human heart in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAETRUM OPGAARD O., NOTHACKER H.-P., EHLERT F.J., KRAUSE D.N. Human urotensin II mediates vasoconstriction via an increase in inositol phosphates. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;406:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAUZEAU V., LE MELLIONNEC E., BERTOGLIO J., SCALBERT E., PACAUD P., LOIRAND G. Human urotensin II-induced contraction and arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation are mediated by RhoA and Rho-kinase. Circ. Res. 2001;88:1102–1104. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STIRRAT A., GALLAGHER M., DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H., BERRY C., KIRK A., RICHARDSON M., MACLEAN M.R. Potent vasodilator responses to human urotensin-II in human pulmonary and abdominal resistance arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;280:H925–H928. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI K., TOTSUNE K., MURAKAMI O., SHIBAHARA S. Expression of urotensin II receptor mRNAs in various human tumour cell lines and secretion of urotensin II-like immunoreactivity by SW-13 adrenocortical carcinoma cells. Peptides. 2001;22:1175–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAL M., AMMER D.A., KARPUJ M., KRIZHANOVSKY V., NAIM M., THOMPSON D.A. A novel putative neuropeptide receptor expressed in neural tissue, including sensory epithelia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;209:752–759. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOTSUNE K., TAKAHASHI K., ARIHARA Z., SONE M., SATOH F., ITO S., HIRONOBU S., MURAKAMI O. Role of urotensin II in patients on dialysis. Lancet. 2001;358:810–811. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., PAKALA R., KATAGIRI T., BENEDICT C.R. Synergistic effect of urotensin II with mildly oxidized LDL on DNA synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2001a;104:16–18. doi: 10.1161/hc2601.092848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., PAKALA R., KATAGIRI T., BENEDICT C.R. Synergistic effect of urotensin II with serotonin on vascular smooth muscle proliferation. J. Hypertens. 2001b;19:2191–2196. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEITZBERG E., AHLBORG G., LUNDBERG J.M. Long-lasting vasoconstriction and efficient regional extraction of endothelin-1 in human splanchnic and renal tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;180:1298–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHARTON J., MORGAN K., RUTHERFORD A.D., CATRAVAS J.D., CHESTER A., WHITEHEAD B.F., DE LEVAL M.R., YACOUB M.H., POLAK J.M. Differential distribution of angiotensin AT2 receptors in the normal and failing human heart. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 1998;284:323–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILKINSON I.B., AFFOLTER J.T., DE HAAS S.L., PELLEGRINI M.P., BOYD J., WINTER M.J., BALMENT R.J., WEBB D.J. High plasma concentrations of human urotensin II do not alter local or systemic hemodynamics in man. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;53:341–347. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTER M.J., HUBBARD P.C., MCCROHAN C.R., BALMENT R.J. A homologous radioimmunoassay for the measurement of urotensin II in the euryhaline flounder, Platichthys flesus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1999;114:249–256. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANAGISAWA M., KURIHARA H., KIMURA S., TOMOBE Y., KOBAYASHI M., MITSUI Y., YAZAKI Y., GOTO K., MASAKI T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Y.G., LI J.X., CAO J., CHEN J.J., YANG J., ZHANG Z.K., DU J.B., TANG C.S. Effect of chronic hypoxia on contents of urotensin II and its functional receptors in rat myocardium. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:64–68. doi: 10.1007/s380-002-8319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOU Y., NAGAI R., YAMAZAKI T. Urotensin-II induces hypertrophic responses in cultured cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]