Abstract

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel is blocked by a broad range of organic anionic compounds. Here we investigate the effects of the indazole compound lonidamine on CFTR channels expressed in mammalian cell lines using patch clamp recording.

Application of lonidamine to the intracellular face of excised membrane patches caused a voltage-dependent block of CFTR currents, with an apparent Kd of 58 μM at −100 mV.

Block by lonidamine was apparently independent of channel gating but weakly sensitive to the extracellular Cl− concentration.

Intracellular lonidamine led to the introduction of brief interruptions in the single channel current at hyperpolarized voltages, leading to a reduction in channel mean open time. Lonidamine also introduced a new component of macroscopic current variance. Spectral analysis of this variance suggested a blocker on rate of 1.79 μM−1 s−1 and an off-rate of 143 s−1.

Several point mutations within the sixth transmembrane region of CFTR (R334C, F337S, T338A and S341A) significantly weakened block of macroscopic CFTR current, suggesting that lonidamine enters deeply into the channel pore from its intracellular end.

These results identify and characterize lonidamine as a novel CFTR open channel blocker and provide important information concerning its molecular mechanism of action.

Keywords: CFTR, chloride channel, open channel block, spectral analysis, binding site, indazole

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis is caused by genetic mutations which lead to dysfunction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), an epithelial cell apical membrane Cl− channel (Sheppard & Welsh, 1999). Pharmacological interventions which increase CFTR expression, processing, or activity are currently being vigorously investigated for their potential therapeutic benefit in cystic fibrosis (Schultz et al., 1999; Zeitlin, 2000). Conversely, specific and high-affinity inhibitors of CFTR have been proposed as treatments for secretory diarrhoea (Sheppard & Welsh, 1992; Mathews et al., 1999; Super, 2000) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (Stanton, 1997; Super, 2000), and also as male contraceptives (Gong et al., 2000a). Unfortunately, although many classes of CFTR inhibitors have been described (Hwang & Sheppard, 1999; Schultz et al., 1999), they lack the potency or specificity required for clinical usefulness (Schultz et al., 1999). Nevertheless, these compounds are important experimental tools, and better understanding of their molecular mechanism of action may aid in the future development of more potent inhibitors.

Several different classes of molecules have been described as open-channel blockers of CFTR (Hwang & Sheppard, 1999; Schultz et al., 1999), including sulfonylureas (Sheppard & Welsh, 1992; Schultz et al., 1996; Venglarik et al., 1996; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997) and related substances (Cai et al., 1999), arylaminobenzoates (McCarty et al., 1993; Walsh et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000), and disulphonic stilbenes (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996). These blockers may share similar mechanisms of action. A broad range of negatively charged organic molecules cause voltage dependent open channel block preferentially or exclusively from the intracellular side of the membrane (reviewed in Linsdell, 2001a), leading to the suggestion that these substances bind within a wide inner pore vestibule which shows little specificity (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; Hwang & Sheppard, 1999; Linsdell, 2001a). Use of channel blockers as structural probes of the pore suggests that amino acid residues in the sixth and twelfth transmembrane regions of the CFTR protein may contribute to the walls of this vestibule (McDonough et al., 1994; Walsh et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000; Gupta & Linsdell, 2002).

Recently, we have identified the indazole compound lonidamine and its analogue 1-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-indazole-3-acrylic acid (AF2785) as potent inhibitors of cyclic AMP-activated Cl− currents in rat epithelial cells (Gong & Wong, 2000; Gong et al., 2000b). Here we examine the mechanism and structural basis of inhibition of human CFTR by lonidamine. Some of these results have been reported in abstract form (Gong & Linsdell, 2002).

Methods

Experiments were carried out on two mammalian cell lines, baby hamster kidney (BHK) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, stably or transiently transfected with wild type or mutated human CFTR, prepared as described previously (Gong et al., 2002; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Mutagenesis of CFTR was carried out as described previously (Gong et al., 2002) and verified by DNA sequencing. No differences in current properties were noted between stably and transiently transfected BHK cells (see also Gong et al., 2002), and in some cases data from stably and transiently transfected BHK cells have been combined. Macroscopic and single channel CFTR current recordings were made using the excised, inside-out configuration of the patch clamp technique, as described in detail previously (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Briefly, CFTR channels were activated following patch excision by exposure to 30–140 nM protein kinase A catalytic subunit (PKA) plus 1 mM MgATP. Both pipette (extracellular) and bath (intracellular) solutions contained (mM): 150 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 N-tris-(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethanesulphonic acid (TES), except where the role of extracellular Cl− concentration was examined (Figure 3), where NaCl in the pipette solution was reduced to 6 mM by equimolar replacement with Na·gluconate. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Lonidamine was added to the patch clamp chamber from a stock solution made up in normal extracellular solution, and was initially solubilized in DMSO at 100 mM. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON, Canada) except PKA (prepared in the laboratory of Dr M.P. Walsh, University of Calgary, AB, Canada). The structure of lonidamine is given in Figure 1a.

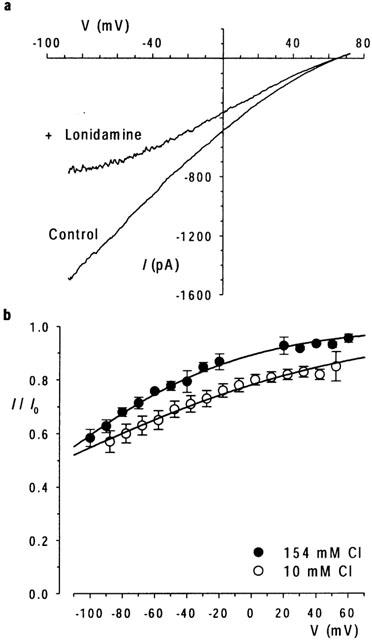

Figure 3.

Lonidamine block is enhanced at low extracellular Cl− concentration. (a) Example I-V relationship recorded with 10 mM extracellular Cl−, before (control) and following addition of 55 μM lonidamine to the intracellular solution. (b) Mean fraction of control current remaining following addition of 55 μM lonidamine, at extracellular Cl− concentrations of 154 mM and 10 mM. Mean of data from five patches in each case. Data with 10 mM extracellular Cl− has been corrected for a calculated liquid junction potential of 12.3 mV. Data have been fitted by equation 2 using the mean parameters described in the text.

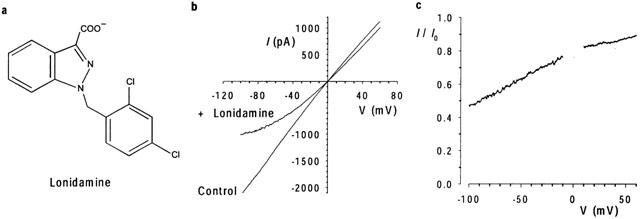

Figure 1.

Inhibition of macroscopic CFTR Cl− currents by intracellular lonidamine. (a) Chemical structure of lonidamine. (b) Example CFTR I-V relationships, leak subtracted as described in Methods, recorded before (control) and following addition of 55 μM lonidamine to the intracellular solution. (c) Fraction of control current remaining (I/I0) following addition of lonidamine for the patch shown in (b).

Current traces were filtered at 100 Hz (for macroscopic current-voltage (I-V) relationships and for single channel currents) using an eight-pole Bessel filter, or at 5 kHz (for spectral analysis of current variance) using an eight-pole Butterworth filter. Filtered currents were digitized at 250 Hz (macroscopic I-V relationships), 1 kHz (for single channel currents) or 10 kHz (for spectral analysis) and analysed using pCLAMP8 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.) or BioPatch Analysis (BioLogic Science Instruments, Claix, France) software. Macroscopic I-V relationships were constructed using depolarizing voltage ramp protocols with a rate of change of voltage 100 mV s−1 (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Background (leak) currents recorded before addition of PKA have been subtracted digitally, leaving uncontaminated CFTR currents (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; 1998). The mean fraction of control current remaining following addition of a blocker B (I/I0) was used to estimate apparent affinity (Kd) according to the equation:

Where nH is the slope factor or Hill coefficient. In some cases, data from individual patches was analysed using the Woodhull (1973) model of voltage dependent block:

Where the voltage dependence of Kd is given by:

Where δ represents the fractional electrical distance experienced by lonidamine, and F, R and T have their usual thermodynamic meanings. This assumes a valence of −1 for lonidamine; its pKa is 4.35 (L. Saso, personal communication), such that >99.9% of the drug is expected to be in the negatively charged form under our experimental conditions.

Single-channel open time was estimated using a 50% threshold detection method. Because most patches contained more than one active CFTR channel, and because the duration of blocked events appeared close to the limit of temporal resolution, closed time and burst duration were not estimated.

Spectral analysis of macroscopic current variance was carried out on continuous current recordings made at −50 mV before and after addition of lonidamine. Current recordings were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and then divided into non-overlapping segments containing 8192 data points (819.2 ms per segment). Power density spectra were then calculated for each segment using BioPatch Analysis software. Spectra from at least 100 segments were then averaged and fitted by the sum of two or three Lorentzian functions of the form:

where Sf is the current variance per unit frequency at each frequency f, S0 is the maximum value of S as f approaches zero, and fc is the corner frequency at which Sf=S0/2.

All other methodological details were as described in detail recently (Linsdell & Gong, 2002; Gong et al., 2002). Experiments were carried out at room temperature, 21–24°C. Mean values are given as mean±s.e.mean. For graphical presentation of mean values, error bars represent the s.e.mean where this is larger than the size of the symbol. Statistical comparisons between groups were carried out using a two-tailed t-test.

Results

Lonidamine inhibition of macroscopic CFTR Cl− currents

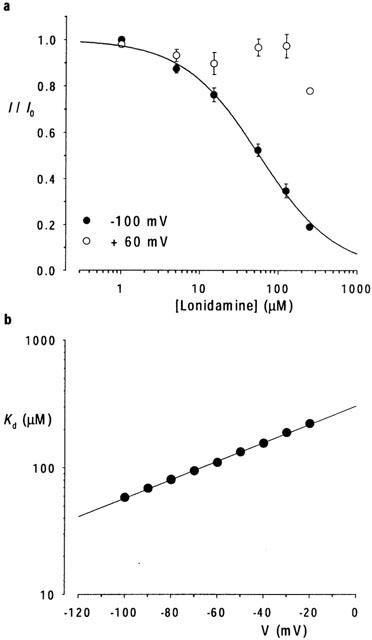

The effects of lonidamine (Figure 1a) on CFTR macroscopic Cl− currents were examined using inside-out membrane patches excised from BHK cells stably or transiently transfected with CFTR (see Methods). As shown in Figure 1, addition of 55 μM lonidamine to the intracellular solution caused a marked voltage-dependent reduction in CFTR current amplitude. The observed voltage dependence is consistent with block of the channel pore within the transmembrane electric field by a negatively charged molecule acting from the inside. The concentration dependence of block is illustrated in Figure 2. Fitting of the mean data shown in Figure 2a by Eq. 1 gives a Kd of 57.8 μM and an nH of 0.91 at −100 mV. However, even at the highest concentration studied (250 μM), block at positive membrane potentials was weak (Figure 2a) and could not reliably be fitted. Higher concentrations of lonidamine were not studied due to poor solubility. A first-order regression fit to the Kd estimated at negative voltages (Figure 2b) suggested a fractional electrical distance (δ) of 0.43. At these voltages, nH was consistently close to unity, suggesting block of the channel by a single lonidamine molecule. Preliminary data suggested a similar affinity and voltage dependence for the related blocker AF2785 (data not shown; Gong & Linsdell, 2002).

Figure 2.

Concentration- and voltage-dependence of block. (a) Mean fraction of control current remaining (I/I0) following addition of different concentrations of lonidamine to the intracellular solution, at a membrane potential of −100 mV and +60 mV. The data at −100 mV have been fitted by equation 1 as described in the text. Mean of data from five patches in each case. (b) Voltage dependence of Kd estimated from fits to mean data such as those shown in (a). Straight line fit suggests fractional electrical distance (δ) of 0.43 for lonidamine block.

The apparent voltage dependence of block (as judged by δ) by intracellular lonidamine is similar to those of a number of CFTR inhibitors which act via open channel block (McCarty et al., 1993; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; 1999; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997; Linsdell, 2001a; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Previously we have discriminated between pore-blocking and gating-modifying effects of the CFTR channel inhibitor Au(CN)2−- by ‘locking' channels in the open state with pyrophosphate (PPi) or by reducing the extracellular Cl− concentration (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Addition of 2 mM PPi to the intracellular solution did not significantly alter the subsequent inhibition of macroscopic current by 55 μM lonidamine; fits to data from individual patches by equation 2 gave a mean Kd(0) of 338±67 μM (n=5) for control, and 523±76 μM (n=6) following addition of PPi (P>0.05), and a δ of 0.425±0.033 (n=5) for control and 0.473±0.031 (n=6) with PPi (P>0.05) (data not shown). In contrast, in patches which had been treated with PPi, reducing extracellular Cl− concentration from 154 mM to 10 mM (by replacement with the impermeant gluconate) significantly strengthened the block by 55 μM lonidamine (Kd(0)=267±32 μM, n=6; P<0.005) and also significantly decreased the voltage dependence of block (δ=0.325±0.015, n=6; P<0.002) (Figure 3).

Kinetic properties of lonidamine block

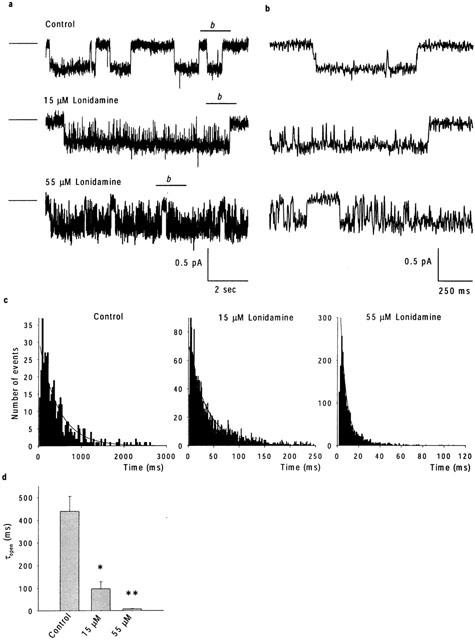

The effects of lonidamine on unitary CFTR currents were examined using inside-out membrane patches excised from CHO cells stably transfected with CFTR. In the absence of blocker, CFTR channel activity was characterized by long open bursts lasting from hundreds of milliseconds to seconds and interrupted by infrequent, brief intraburst closures, with longer interburst closures also lasting from hundreds of milliseconds to seconds (Figure 4a,b). Addition of lonidamine to the intracellular solution led to frequent brief interruptions in the open channel current at hyperpolarized voltages (Figure 4a,b), leading to a concentration-dependent decrease in mean channel open time (Figure 4c,d), as estimated by a simple mono-exponential fit. In contrast, at the concentrations used lonidamine had no apparent effect on unitary current amplitude (Figure 4a,b; data not shown). Since the kinetics of block appear close to the limit of resolution at the filter frequencies used, channel closed time and rates of block and unblock were not quantified from these single channel records. Although the block was not sufficiently well resolved for detailed single channel kinetic analysis, the data presented in Figure 4 are highly suggestive of a kinetically intermediate blocking reaction between lonidamine and the CFTR channel.

Figure 4.

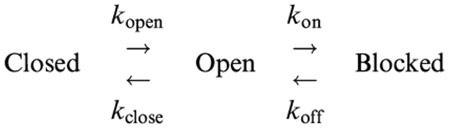

Effects of lonidamine on CFTR single channel currents. (a) Example single channel currents recorded at a membrane potential of −50 mV, under control conditions and when the intracellular solution contained 15 or 55 μM lonidamine. The line to the left of each trace represents the closed state of the channel. The line above each trace marked ‘b' is expanded in (b), allowing individual lonidamine-induced blocking events better to be resolved. (c) Open time histograms, obtained from recordings at −50 mV such as those shown in (a). Note the different scale to the abscissa in each case. All three have been fitted by a single exponential function with time constants of 439 ms (Control), 98 ms (15 μM lonidamine) and 7.8 ms (55 μM lonidamine). (d) Mean open time constants estimated from fits such as those shown in (c). Mean of data from three patches in each case. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from control (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

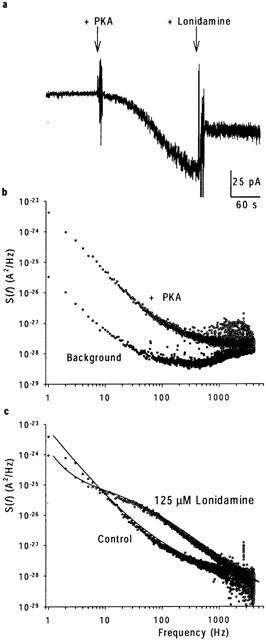

Previously, the effects of sulfonylureas which apparently block CFTR with similar kinetics to lonidamine have been studied and quantified using spectral analysis (Schultz et al., 1996; Venglarik et al., 1996). In order to verify our observations at the single channel level, and better to quantify the kinetics of block, we therefore performed a similar spectral analysis of lonidamine block of CFTR macroscopic current in inside-out membrane patches excised from BHK cells (Figure 5). Activation of CFTR current at −50 mV was associated with an increase in current variance, especially at low frequencies (Figure 5b). The difference spectrum obtained by subtraction of the background variance from that following full current activation with PKA was well fitted by the sum of two Lorentzian components (equation 4) (Figure 5c); a dominant, low frequency component (fc(1)=0.91±0.29 Hz, n=10) which may reflect ATP-dependent channel gating, and a second component with much lower power (S02<0.05% of S01 in each case) and very high frequency (fc(2)=990±51 Hz, n=10), similar to those described previously by others (Fischer & Machen, 1994; Venglarik et al., 1994; 1996). Addition of lonidamine to the intracellular solution not only decreased current amplitude (Figure 5a) but also led to the introduction of a new component of current variance at intermediate frequencies (Figure 5c). Difference spectra recorded following addition of lonidamine were fitted by the sum of three Lorentzian components (equation 4); two with frequencies very similar to those seen before lonidamine addition (although the frequency of fc(1) was significantly increased by high concentrations of lonidamine; see Table 1), and a third, intermediate-frequency component (fc(b)) which presumably reflects lonidamine block and unblock of the open channel (Table 1). Furthermore, the fc of this intermediate Lorentzian components was sensitive to lonidamine concentration (Table 1; Figure 6). Previously (Venglarik et al., 1996), channel blocker-dependent changes in fc such as that shown in Figure 6 have been used to estimate blocker on- and off-rates, kon and koff, according to a simple kinetic scheme:

|

Figure 5.

Spectral analysis of lonidamine block. (a) Activation of macroscopic current at −50 mV following addition of PKA, and block on addition of 125 μM lonidamine. (b) Power spectra associated with background and PKA-activated currents. (c) Difference power spectra calculated following subtraction of background spectrum shown in (b), from data recorded before (control) and following addition of 125 μM lonidamine to the intracellular solution. The control spectrum has been fitted by the sum of two Lorentzian components (see Methods), with maximum variances per unit frequency (S0) of 1.5×10−23 A2 Hz−1 and 2.2×10−28 A2 Hz−1, and corner frequencies (fc) of 0.7 Hz and 990 Hz respectively (see equation 4). In the presence of lonidamine, a third Lorentzian component has been added; maximum variances in this case are 1.4×10−24 A2 Hz−1, 2.5×10−26 A2 Hz−1 and 5.6×10−28 A2 Hz−1, with corner frequencies of 1.6, 71 and 1000 Hz, respectively. The increase in frequency of the lowest frequency component, fc(1), was a consistent observation with this concentration of lonidamine (see Table 1).

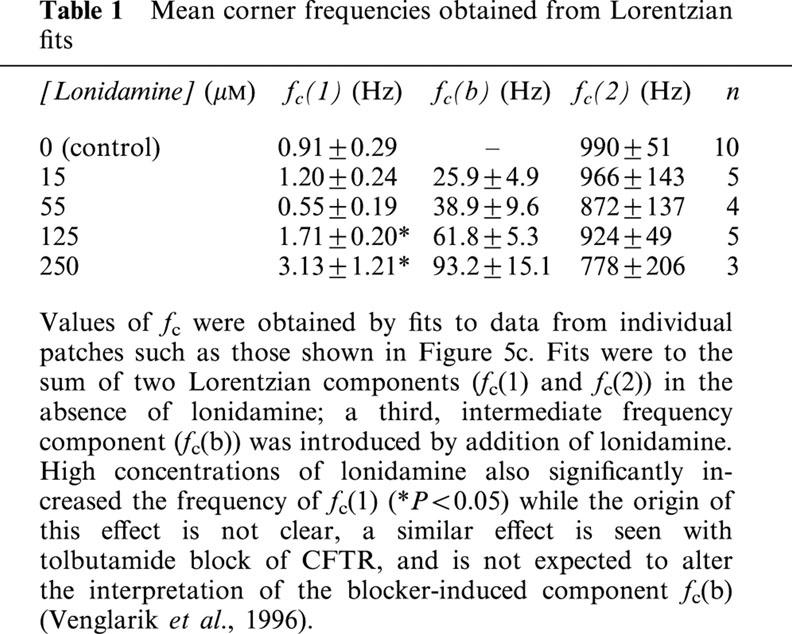

Table 1.

Mean corner frequencies obtained from Lorentzian fits

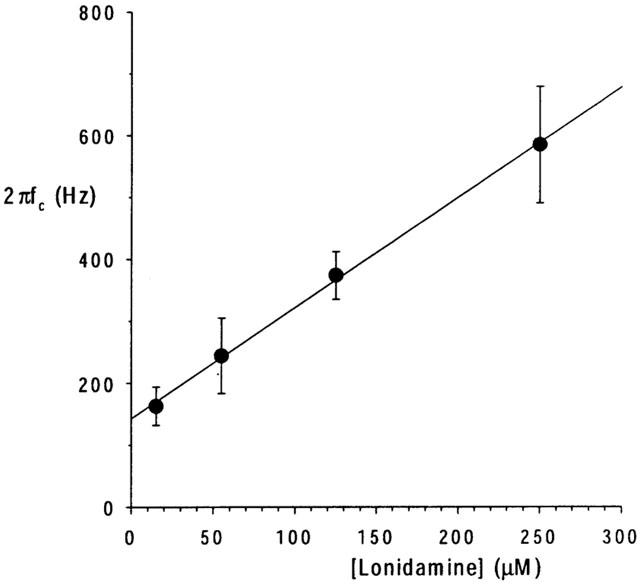

Figure 6.

Relationship between lonidamine-induced current variance corner frequency and concentration. 2πfc, estimated for the lonidamine-induced intermediate frequency Lorentzian component (fc(b); Table 1) as shown in Figure 5c, increases as a linear function of lonidamine concentration. Mean of data from 3–5 patches. The fitted straight line has an intercept of 143 Hz and a slope of 1.79 Hz μM−1.

Although more complicated schemes may be envisioned (Schultz et al., 1996; Nagel, 1999; Sheppard & Welsh, 1999; Zou & Hwang, 2001), this is the simplest that can account for the effects of open-channel blockers such as lonidamine (Venglarik et al., 1996; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997; Zhou et al., 2001). As predicted by such a scheme (Lindemann & van Driessche, 1977; Venglarik et al., 1996), 2πfc (estimated as shown in Figure 5) was a linear function of lonidamine concentration (Figure 6), with an intercept (∼koff) of 143 s−1 and a slope (kon) of 1.79 μM−1 s−1. The ratio of these rates, koff/kon, suggests a Kd of 80 μM at −50 mV, similar to that estimated from the reduction in macroscopic current amplitude (113 μM; Figure 2b). Furthermore, this estimate of kon predicts mean channel open times (∼1/kon) of 37 ms and 10 ms with 15 and 55 μM lonidamine, respectively, similar to values estimated by single channel analysis (Figure 4). The mean duration of the lonidamine-blocked state (∼1/koff) is predicted to be ∼7 ms.

Location of the lonidamine binding site on CFTR

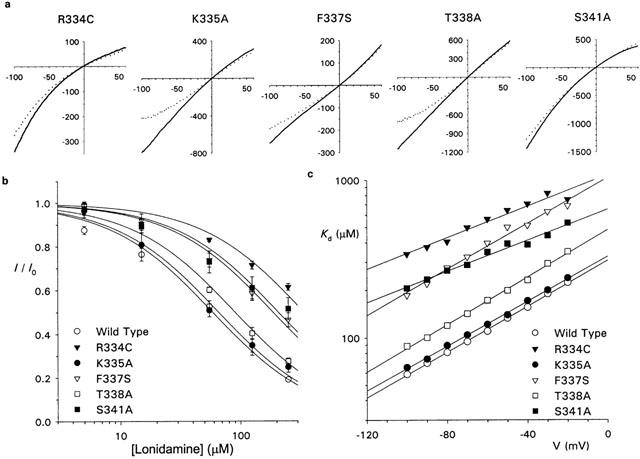

The effects of intracellular lonidamine on CFTR macroscopic and unitary currents are consistent with an open-channel block mechanism. In order to gain some information on the molecular determinants of lonidamine block, we examined its effects on macroscopic currents carried by CFTR pore mutants. We used point mutations at each of five residues in a crucial region of the pore-forming sixth transmembrane region (TM6) (Dawson et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 7a, 55 μM lonidamine inhibited currents carried by R334C, K335A, F337S, T338A and S341A-CFTR. However, R334C, F337S and S341A were only weakly inhibited by this concentration relative to wild-type CFTR (see Figure 1). The effect of these mutations on block by lonidamine is more clearly seen in the dose-response curves shown in Figure 7b. Fits of these mean data by equation 1 suggests a Kd (at −100 mV) of 58.5 μM for wild-type, 65.6 μM for K335A, 90.0 μM for T338A, 186 μM for F337S, 206 μM for S341A, and 338 μM for R334C. Similar analyses at other potentials showed a similar increase in Kd in R334C, F337S, S341A and (to a far lesser extent) T338A (Figure 7c). Fitting data from individual patches with equation 2 gave similar and, except in the case of K335A, significant changes in Kd(-100): wild-type 60.6±5.2 μM (n=5), K335A 63.1±7.4 μM (n=5) (P>0.05), T338A 93.4±4.1 μM (n=5) (P<0.002), F337S 166±18 μM (n=5) (P<0.0005), S341A 169±25 μM (n=5) (P<0.005), R334C 260±19 μM (n=4) (P<0.00001). These same fits also revealed changes in the voltage dependence of block, as judged by changes in δ, although this was only statistically significant in the case of R334C: wild-type 0.426±0.033 (n=5), K335A 0.484±0.024 (n=5) (P>0.05), T338A 0.410±0.045 (n=5) (P>0.05), F337S 0.365±0.015 (n=5) (P>0.05), S341A 0.285±0.061 (n=5) (P>0.05), R334C 0.233±0.066 (n=4) (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Lonidamine block of pore mutant forms of CFTR. (a) Example I-V relationships for R334C, K335A, F337S, T338A and S341A-CFTR, before (solid lines) and following (dotted lines) addition of 55 μM lonidamine to the intracellular solution. In each case the scale is current in pA on the ordinate and membrane potential in mV on the abscissa. (b) Concentration dependence of block at −100 mV for wild-type, R334C, K335A, F337S, T338A and S341A. Mean of data from five patches in each case. Each has been fitted by equation 1, giving Kds of 58.5 μM (wild-type), 65.6 μM (K335A), 90.0 μM (T338A), 186 μM (F337S), 206 μM (S341A) and 338 μM (R334C). For simplicity, nH was fixed at unity. (c) Voltage dependence of Kd, estimated from fits to mean data such as those shown in (b).

Discussion

A broad range of negatively charged organic molecules act as open channel blockers of the CFTR Cl− channel (Hwang & Sheppard, 1999; Schultz et al., 1999; Linsdell, 2001a). Based on the effects of extracellular lonidamine and AF2785 on whole cell Cl− currents in rat epithelial cells, we previously suggested that these compounds may inhibit CFTR by a similar mechanism (Gong & Wong, 2000). We have now further characterized the channel blocking effects of lonidamine applied to the intracellular face of heterologously expressed human CFTR channels. We find that lonidamine causes a voltage-dependent block when added to the intracellular side of the membrane (Figures 1, 2) which is apparently independent of channel gating but significantly strengthened by reducing the extracellular Cl− concentration (Figure 3), and which leads to discrete interruptions in the unitary current record (Figure 4), resulting in a decrease in mean channel open time (Figure 4) and the introduction of a new, intermediate-frequency component of current variance (Figure 5). These effects suggest a common mechanism of action to well-known CFTR open channel blockers such as sulfonylureas (Schultz et al., 1996; Venglarik et al., 1996; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997), arylaminobenzoates (McCarty et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 2000) and disulphonic stilbenes (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996). The apparent kinetics of block suggested by spectral analysis of lonidamine-induced current noise is consistent with the effects observed on single channel currents. Furthermore, an open channel block mechanism of action is supported by the fact that block is weakened following mutagenesis of the putative CFTR pore region (Figure 7). The apparent affinity of lonidamine (58 μM at −100 mV; Figure 2) is comparable to that of well-known classes of CFTR inhibitors listed above (see Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1999), thus increasing the repertoire of well-characterized CFTR open channel blockers. The estimated blocker on- and off-rates (1.79 μM−1 s−1 and 143 s−1 respectively) are also comparable to those previously estimated for blockers such as diphenylamine-2-carboxylate (DPC; McCarty et al., 1993; McDonough et al., 1994), glibenclamide (Schultz et al., 1996; Sheppard & Robinson, 1997), tolbutamide (Venglarik et al., 1996) and meglitinide and mitiglinide (Cai et al., 1999).

Some differences were observed between the present results and those previously reported for lonidamine block of CFTR endogenously expressed in rat epididymal cells (Gong & Wong, 2000). Using whole cell recording, the apparent IC50 for rat CFTR was estimated to be 631 μM when present in the extracellular solution, and block was not strongly voltage-dependent; intracellular lonidamine was reported to be ineffective as a blocker (Gong & Wong, 2000). Furthermore, block by extracellular lonidamine was reported to be strengthened at high pH (Gong & Wong, 2000), although this may reflect a drug loading effect as previously described for DPC (Zhang et al., 2000). We feel that the main differences between the present and previous study are likely to be methodological (e.g. whole cell versus inside-out patch recording, extracellular application and/or intracellular dialysis of lonidamine versus direct application to the intracellular face of the membrane, different voltages used in estimation of apparent affinity). Nevertheless, membrane side-dependent and/or species differences in lonidamine block of CFTR cannot be ruled out and are currently being investigated in more detail (X.D. Gong, P. Linsdell, K.H. Cheung, G.P.H. Leung & P.Y.D. Wong, unpublished observations).

Multiple classes of organic anions have been suggested to cause open channel block of CFTR by binding within a wide inner vestibule of the pore, thereby occluding the pore and temporarily interrupting the flow of Cl− ions (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; Hwang & Sheppard, 1999; Linsdell, 2001a). High affinity open channel blockers may therefore be useful as structural probes of this inner pore vestibule (McDonough et al., 1994; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; Walsh et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000; Gupta & Linsdell, 2002). Block by lonidamine was sensitive to mutagenesis of residues within TM6 (Figure 7), previously identified as an important determinant of pore properties (Dawson et al., 1999; Gong et al., 2002). Lonidamine block was weakened in the TM6 mutants R334C, F337S and S341A (Figure 7), suggesting that these residues may normally contribute to lonidamine binding within the pore. Recent models of the pore (Smith et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2002) suggest that these three residues may be located in an extracellular vestibule (R334), the narrowest pore region (F337), and an intracellular vestibule (S341) respectively. Thus lonidamine may enter deep into the pore when applied to its cytoplasmic end, perhaps with part of the molecule becoming lodged within a physical constriction in the pore. The strong effects of the R334C mutant (Figure 7) are somewhat surprising, given that this residue is purportedly in the external pore vestibule. One possibility is that part of the lonidamine molecule can penetrate most of the way through the pore from its cytoplasmic end, perhaps with a wider aspect of the molecule lodged within the narrowest pore region. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that lonidamine is permeant in the CFTR pore when added to the intracellular side of the membrane.

Each of the five mutants studied has previously been associated with altered anion permeation properties (McDonough et al., 1994; Linsdell et al., 1998; 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2002), suggesting that lonidamine blocks the channel by binding within a functionally important region of the pore. S341 has previously been suggested to contribute to arylaminobenzoate blocker binding within the pore (McDonough et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 2000), while F337 appears to interact with glibenclamide (Gupta & Linsdell, 2002). Thus different organic CFTR channel blockers may share common or overlapping binding sites within the pore, consistent with their apparently similar mechanisms of action. Each of these residues is also implicated in permeant anion binding within the pore (Linsdell, 2001b; Smith et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2002), suggesting that permeant and blocking ions may compete for common intrapore binding sites.

In addition to their use as structural probes of the pore region, high affinity CFTR blockers are potentially useful in the treatment of secretory diarrhoea (Sheppard & Welsh, 1992; Mathews et al., 1999; Super, 2000) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (Stanton, 1997; Super, 2000). The comparable affinity of lonidamine (present study) and AF2785 (Gong & Linsdell, 2002) with more well-known CFTR channel blockers (see Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1999) suggests that these compounds offer a novel starting point in the development of specific and high-affinity CFTR inhibitors. The specificity of lonidamine itself is not known; to the best of our knowledge, its effects on other Cl− channels or ATP-binding cassette proteins has not been reported. Although lonidamine has previously been described as having anti-tumour effects, these have never been associated with direct modulation of multidrug resistance associated-proteins, and may instead result from alterations in cellular respiration and glycolysis (e.g. Floridi et al., 1998). Understanding the molecular mechanism of action of CFTR channel blockers such as lonidamine by identification of crucial determinants of their binding within the pore may aid in the future design of high-affinity, selective and clinically useful CFTR inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CCFF) (to P. Linsdell), and the Rockefeller Foundation and Ernst Schering Research Foundation (to P.Y.D. Wong). X. Gong is a CCFF postdoctoral fellow. P. Linsdell is a CCFF scholar.

Abbreviations

- BHK

baby hamster kidney

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- PKA

protein kinase A catalytic subunit

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- TES

N-tris-(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethanesulphonic acid

- TM6

sixth transmembrane region

References

- CAI Z., LANSDELL K.A., SHEPPARD D.N. Inhibition of heterologously expressed cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels by non-sulphonylurea hypoglycaemic agents. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:108–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON D.C., SMITH S.S., MANSOURA M.K. CFTR: mechanism of anion conduction. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:S47–S75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER H., MACHEN T.E. CFTR displays voltage dependence and two gating modes during stimulation. J. Gen. Physiol. 1994;104:541–566. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLORIDI A., BRUNO T., MICCADEI S., FANCIULLI M., FEDERICO A., PAGGI M.G. Enhancement of doxorubicin content by the antitumor drug lonidamine in resistant Ehrlich ascites tumor cells through modulation of energy metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;56:841–849. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONG X., BURBRIDGE S.M., COWLEY E.A., LINSDELL P. Molecular determinants of Au(CN)2− binding and permeability within the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel pore. J. Physiol. 2002;540:39–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONG X.D., LEUNG G.P., CHEUK B.L., WONG P.Y. Interference with the formation of the epididymal microenvironment – a new strategy for male contraception. Asian J. Androl. 2000a;2:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONG X., LINSDELL P.Mechanism and molecular basis of lonidamine block of the human CFTR chloride channel Biophys. J. 200282239a(abstract) [Google Scholar]

- GONG X.D., WONG P.Y.D. Characterization of lonidamine and AF2785 blockade of the cyclic AMP-activated chloride current in rat epididymal cells. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;178:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s002320010030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONG X.D., WONG Y.L., LEUNG G.P.H., CHENG C.Y., SILVESTRINI B., WONG P.Y.D. Lonidamine and analogue AF2785 block the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-activated chloride current and chloride secretion in the rat epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 2000b;63:833–838. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA J., LINSDELL P. Point mutations in the pore region directly or indirectly affect glibenclamide block of the CFTR chloride channel. Pflügers Arch. 2002;443:739–747. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0762-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HWANG T.-C., SHEPPARD D.N. Molecular pharmacology of the CFTR Cl− channel. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEMANN B., VAN DRIESSCHE W. Sodium-specific membrane channels of frog skin are pores: current fluctuations reveal high turnover. Science. 1977;195:292–294. doi: 10.1126/science.299785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P. Direct block of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by butyrate and phenylbutyrate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001a;411:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P. Relationship between anion binding and anion permeability revealed by mutagenesis within the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. J. Physiol. 2001b;531:51–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0051j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., EVAGELIDIS A., HANRAHAN J.W. Molecular determinants of anion selectivity in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Biophys. J. 2000;78:2973–2982. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., GONG X. Multiple inhibitory effects of Au(CN)2− ions on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel currents. J. Physiol. 2002;540:29–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., HANRAHAN J.W. Disulphonic stilbene block of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in a mammalian cell line and its regulation by a critical pore residue. J. Physiol. 1996;496:687–693. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., HANRAHAN J.W. Adenosine triphosphate-dependent asymmetry of anion permeation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 1998;111:601–614. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., HANRAHAN J.W. Substrates of multidrug resistance-associated proteins block the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1471–1477. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSDELL P., ZHENG S.-X., HANRAHAN J.W. Non-pore lining amino acid side chains influence anion selectivity of the human CFTR Cl− channel expressed in mammalian cell lines. J. Physiol. 1998;512:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.001bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHEWS C.J., MACLEOD R.J., ZHENG S.-X., HANRAHAN J.W., BENNETT H.P.J., HAMILTON J.R. Characterization of the inhibitory effect of boiled rice on intestinal chloride secretion in guinea pig crypt cells. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCARTY N.A., MCDONOUGH S., COHEN B.N., RIORDAN J.R., DAVIDSON N., LESTER H.A. Voltage-dependent block of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by two closely related arylaminobenzoates. J. Gen. Physiol. 1993;102:1–23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONOUGH S., DAVIDSON N., LESTER H.A., MCCARTY N.A. Novel pore-lining residues in CFTR that govern permeation and open-channel block. Neuron. 1994;13:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGEL G. Differential function of the two nucleotide binding domains on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1461:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTZ B.D., DEROOS A.D.G., VENGLARIK C.J., SINGH A.K., FRIZZELL R.A., BRIDGES R.J. Glibenclamide blockade of CFTR chloride channels. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:L192–L200. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTZ B.D., SINGH A.K., DEVOR D.C., BRIDGES R.J. Pharmacology of CFTR chloride channel activity. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:S109–S144. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPPARD D.N., ROBINSON K.A. Mechanism of glibenclamide inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in a murine cell line. J. Physiol. 1997;503:333–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.333bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPPARD D.N., WELSH M.J. Effect of ATP-sensitive K+ channel regulators on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride currents. J. Gen. Physiol. 1992;100:573–591. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPPARD D.N., WELSH M.J. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:S23–S45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH S.S., LIU X., ZHANG Z.-R., SUN F., KRIEWALL T.E., MCCARTY N.A., DAWSON D.C. CFTR: covalent and noncovalent modification suggests a role for fixed charges in anion conduction. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;118:407–431. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANTON B.A. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and renal function. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 1997;109:457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUPER M. CFTR and disease: implications for drug development. Lancet. 2000;355:1840–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENGLARIK C.J., SCHULTZ B.D., DEROOS A.D.G., SINGH A.K., BRIDGES R.J. Tolbutamide causes open channel blockade of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2696–2703. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79839-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENGLARIK C.J., SCHULTZ B.D., FRIZZELL R.A., BRIDGES R.J. ATP alters current fluctuations of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: evidence for a three state activation mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 1994;104:123–146. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALSH K.B., LONG K.J., SHEN X. Structural and ionic determinants of 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropyl-amino)-benzoic acid block of the CFTR chloride channel. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:369–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODHULL A.M. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. J. Gen. Physiol. 1973;61:687–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEITLIN P.L. Future pharmacological treatment of cystic fibrosis. Respiration. 2000;67:351–357. doi: 10.1159/000029528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Z.-R., ZELTWANGER S., MCCARTY N.A. Direct comparison of NPPB and DPC as probes of CFTR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;175:35–52. doi: 10.1007/s002320001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Z., HU S., HWANG T.-C. Voltage-dependent flickery block of an open cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel pore. J. Physiol. 2001;532:435–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0435f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOU X., HWANG T.-C. ATP hydrolysis-coupled gating of CFTR chloride channels: structure and function. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5579–5585. doi: 10.1021/bi010133c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]