Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is a key modulator of cellular Ca2+ signalling and a determinant of mitochondrial function. Here, we demonstrate that NO governs capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE) into HEK293 cells by impairment of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling.

Authentic NO as well as the NO donors 1-[2-(carboxylato)pyrrolidin-1-yl]diazem-1-ium-1,2-diolate (ProliNO) and 2-(N,N-diethylamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide (DEANO) suppressed CCE activated by thapsigargin (TG)-induced store depletion. Threshold concentrations for inhibition of CCE by ProliNO and DEANO were 0.3 and 1 μM, respectively.

NO-induced inhibition of CCE was not mimicked by peroxynitrite (100 μM), the peroxynitrite donor 3-morpholino-sydnonimine (SIN-1, 100 μM) or 8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-BrcGMP, 1 mM). In addition, the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazole[4,3-a] quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ, 30 μM) failed to antagonize the inhibitory action of NO on CCE.

DEANO (1–10 μM) suppressed mitochondrial respiration as evident from inhibition of cellular oxygen consumption. Experiments using fluorescent dyes to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels, respectively, indicated that DEANO (10 μM) depolarized mitochondria and suppressed mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration. The inhibitory effect of DEANO on Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria was confirmed by recording mitochondrial Ca2+ during agonist stimulation in HEK293 cells expressing ratiometric-pericam in mitochondria.

DEANO (10 μM) failed to inhibit Ba2+ entry into TG-stimulated cells when extracellular Ca2+ was buffered below 1 μM, while clear inhibition of Ba2+ entry into store depleted cells was observed when extracellular Ca2+ levels were above 10 μM. Moreover, buffering of intracellular Ca2+ by use of N,N′-[1,2-ethanediylbis(oxy-2,1-phenylene)] bis [N-[25-[(acetyloxy) methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]]-, bis[(acetyloxy)methyl] ester (BAPTA/AM) eliminated inhibition of CCE by NO, indicating that the observed inhibitory effects are based on an intracellular, Ca2+ dependent-regulatory process.

Our data demonstrate that NO effectively inhibits CCE cells by cGMP-independent suppression of mitochondrial function. We suggest disruption of local Ca2+ handling by mitochondria as a key mechanism of NO induced suppression of CCE.

Keywords: Capacitative Ca2+ entry, cellular Ca2+ regulation, nitric oxide, mitochondrial uncoupling, intracellular Ca2+ handling

Introduction

Depletion of Ca2+ stores by either inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent or IP3-independent pathways results in activation of a Ca2+ influx pathway that is termed store-operated Ca2+ entry or ‘capacitative' Ca2+ entry (CCE; Putney, 1986; 1990). The molecular nature of this phenomenon is still elusive. As to the signalling pathways that link CCE channels to intracellular stores, a diffusible Ca2+ influx factor (Randriamampita & Tsien, 1993) as well as a direct physical coupling between CCE channels and components of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (conformational coupling; Putney, 1999) or the fusion of CCE channel-containing membrane vesicles with the plasma membrane (Fasolato et al., 1993) have been proposed. In addition, changes in the sub-plasmalemmal Ca2+ concentration may play a critical role in the process of activation (Krause et al., 1999; Putney et al., 2001). Recently, evidence has been accumulated for the regulation of CCE by an intracellular Ca2+ store other than the ER, i.e. mitochondria. Mitochondria have been proposed to control Ca2+ channel gating in T lymphocytes (Hoth et al., 2000) and in Jurkat T cells (Makowska et al., 2000). In Jurkat cells, capacitative Ca2+ entry channels were reported to remain inactive during depletion of Ca2+ stores when the mitochondrial protonomotive force is collapsed by carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) or myxothiazol (Makowska et al., 2000). The effects of mitochondrial uncoupling on CCE of jurkat cells were not related to changes in cellular ATP/ADP ratio. Mitochondria are likely to sequester Ca2+ from sub-plasmalemmal compartments, thereby blunting the elevation of sub-plasmalemmal Ca2+ during Ca2+ entry and consequently Ca2+-mediated negative feedback inhibition of CCE channels (Lawrie et al., 1996; Rizzuto et al., 1993; 1994; Rutter et al., 1993). Impairment of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling such as blockade of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake leads to severe alterations in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (Werth & Thayer, 1994; Herrington et al., 1996) and was shown to suppress sustained Ca2+ influx into T-lymphocytes (Hoth et al., 1997).

Nitric oxide (NO) is a mediator which governs Ca2+ homeostasis in a highly complex and cell specific manner (Clementi & Meldolesi, 1997; Clementi, 1998). NO was reported to potentiate CCE in pancreatic acinar cells and colonic epithelial cells (Bischof et al., 1995) but inhibits CCE in platelets (Trepakova et al., 1999) and smooth muscle cells (Wayman et al., 1996; Cohen et al., 1999). NO has been proposed to control Ca2+ transport via cGMP-dependent (Gukovskaya & Pandol, 1994) as well as cGMP-independent pathways (Watson et al., 1999). Promotion of SERCA-dependent refilling of intracellular Ca2+ stores has been postulated as the mechanism by which NO causes inhibition of Ca2+ entry signals (Trepakova et al., 1999). Since mitochondrial function has been recognized as an important modulator of cellular Ca2+ signalling, it appeared of interest to test for a possible role of mitochondria as a cellular switchboard linking NO and Ca2+ signals. With the present study, we demonstrate that NO is able to inhibit capacitative Ca2+ entry into HEK 293 cells by a mechanism that is independent of cGMP or peroxynitrite formation, but involves uncoupling of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293 (human embryonic kidney) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum and used for the experiments.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+

Intracellular Ca2+ was measured with 5-Oxazole carboxylic acid, 2-[6-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-5-[2-[2-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-5-methylphenoxy]ethoxy]-2-benzofuranyl]-, (acetyloxy)methyl ester (fura-2/AM). Fura-2/AM was initially dissolved in DMSO at 2 mM and used at a final concentration of 2 μM. Confluent cells were harvested by enzymatic digestion (0.25% trypsin) and suspended in 5 ml DMEM without serum, and loaded with fura-2/AM for 60 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Thereafter, cells were washed once with Ca2+-containing Tris buffer (mM: NaCl 100, KCl 5, Tris 50, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1, pH 7.4), incubated for 20 min and washed in Tris buffer without Ca2+. Fluorescence measurements were carried out with a dual wavelength spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi F2000). Cells were maintained at 37°C, and emission was collected at 510 nm at excitation of 340 nm and 380 nm. For store depletion 100 nm thapsigargin (TG) was added, and extracellular Ca2+ was elevated subsequently by adding 1 mM Ca2+ to induce Ca2+ entry. [Ca2+]i was determined from the fluorescence ratio F340/F380 according to Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). The fluorescence after sequential addition of 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) to the cells provided the maximum fluorescence ratio (Rmax) and the minimum fluorescence ratio (Rmin) respectively. [Ca2+]i was calculated using the equation

where β is the ratio of the emission fluorescence at 380 nm excitation in the presence of Triton X-100 and Triton X-100 plus EGTA, respectively.

Measurement of cGMP accumulation

HEK293 cells were subcultured on 24-well plates. Cells were incubated with NO containing solutions or NO donors for 14 min (corresponding to the incubation time in experiments measuring Ca2+ entry) and the incubation was stopped by removal of medium and addition of 0.01 M HCl. Guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) was measured in the samples by radioimmunoassay as described in Schmidt et al. (1989).

Measurement of Ba2+ entry

Ba2+ entry into TG-stimulated HEK293 cells was measured as described above by recording of the fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) from Fura-2-loaded cells. The experiments were conducted either in nominally Ca2+-free or in extracellular Ca2+-chelated condition as specified. Ba2+ entry was initiated by adding 3 mM Ba2+, and control experiments were performed with vehicle only. Ba2+ entry was quantified as the initial slope of fluorescence ratio calculated from the changes in fluorescence observed within 1 min after Ba2+ addition. TG stimulated Ba2+ entry about 2.5 fold over basal values which were not subtracted in the analysis.

Measurement of cellular oxygen consumption

HEK293 cells from one petri dish were harvested and suspended in 1.8 ml of 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing (mM): NaCl 100, KCl 5, MgCl2 1, and CaCl2 3. Oxygen consumption was measured with a Clark-type electrode (ISO2, World Precision Instruments, Mauer, Germany) in a temperature controlled glass vial sealed with a rubber septum. After equilibration (∼1 min), 5 μl of a stock solution of the NO donor or solvent was injected through the septum, and O2 consumption was monitored over 10–15 min under constant stirring. Two-point calibration of the sensor was performed in air-saturated H2O at 37°C (6.9 p.p.m.; 0.216 mM O2) and argon atmosphere (zero O2).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential with JC-1

Cells were loaded at room temperature with 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanide iodine (JC-1, 5 μM) for 10 min in the dark. Prior to the experiments, cells were washed twice and mounted in a customized superfusion chamber. To monitor mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were illuminated for 200 ms alternatively at 485 nm (485DF15; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.) and 575 nm (575DF25; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.). Emission was detected at 528 and 633 nm (528-633DBEN, XF53; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.).

Measurement of mitochondrial Ca2+ with rhod-2/AM

For measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+, cells were seeded on poly-L-lysine-coated cover slips (6×6 mm) and loaded with Xanthylium, 9-[4-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-3-[2-[2-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]-amino]phenoxy]ethoxy]phenyl]-3.6-bis(dimethylamino)- bromide (rhod-2/AM) in DMEM without fetal calf serum, at a concentration of 2 μM for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were illuminated using a monochromator (Polychrome II, Till Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany) at 540 nm and fluorescence emission was collected at 605 nm. Fluorescence was monitored on a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope equipped with a CCD camera system (Sensicam, PCO, Kelheim, Germany) and analysed using the Axon Imaging Workbench 2.1 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, U.S.A.).

Measurement of mitochondrial Ca2+ using heterologous expression of ratiometric-pericam that is specifically targeted to mitochondria

Mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration was monitored in single, adherent HEK293 cells expressing ratiometric-pericam-mt which was kindly provided by Dr Atsushi Miyawaki, RIKEN, Saitama, Japan. Cells were grown up to 50% of confluence and were transiently transfected with cDNA encoding the ratiometric-pericam-mt (Nagai et al., 2001), using SuperFectTM (Qiagen, BioTrade, Vienna, Austria) in the standard transfection protocol described for this transfection reagent. Between 24–36 h after transfection, cells were mounted in a customized perfusion chamber that allowed superfusion with buffer (flow rate 1–2 ml/min). Experiments were performed at room temperature (20–23°C). For measuring the mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m), an imaging microscope was used (Frieden et al., 2002; Graier et al., 1998; Paltauf-Doburzynska et al., 2000). Briefly, a Nikon inverted microscope (Eclipse 300TE, Nikon, Vienna) was equipped with CFI Plan Fluor ×40 oil immersion objective (NA 1.3, Nikon, Vienna, Austria), an epifluorescence system (150 W XBO; Optiquip, Highland Mills, NY, U.S.A.) and a computer-controlled filter wheel (Ludl, Electronic Products, Hawthorne, NY, U.S.A.). To monitor [Ca2+]m, cells were illuminated at room temperature for 500 ms alternatively at 410 nm (410DF20; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.) and 480 nm (480AF30; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.). Emission was monitored at 535 nm (535AF26 with dichroic 455DRVP; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT, U.S.A.) using a liquid-cooled CCD camera (−30°C; Quantix KAF 1400G2, Roper Scientific, Acton, MA, U.S.A.). All devices were controlled by Metafluor 4.0 (Visitron Systems, Puchheim, Germany). Mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration is presented as the fluorescence ratio (F480/410) at 535 nm emission.

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from the following suppliers: Tissue culture medium was from Gibco BRL (Vienna, Austria); fura-2/AM, rhod-2/AM, JC-1 and BAPTA/AM were from Molecular Probes (Leiden, Netherlands); DEANO was from Alexis (Switzerland) and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Vienna, Austria). NO solutions were prepared as described in Kukovetz & Holzmann (1989).

Statistical analysis

Time courses of fluorescence changes are illustrated as mean values obtained from the indicated number of experiments. For clarity, error bars were omitted in time course illustrations. Averaged data given for specific time points are expressed as mean values±s.e.mean. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05 using Student's t-test for unpaired values.

Results

Inhibition of capacitative Ca2+ entry into HEK293 cells by NO and NO donors

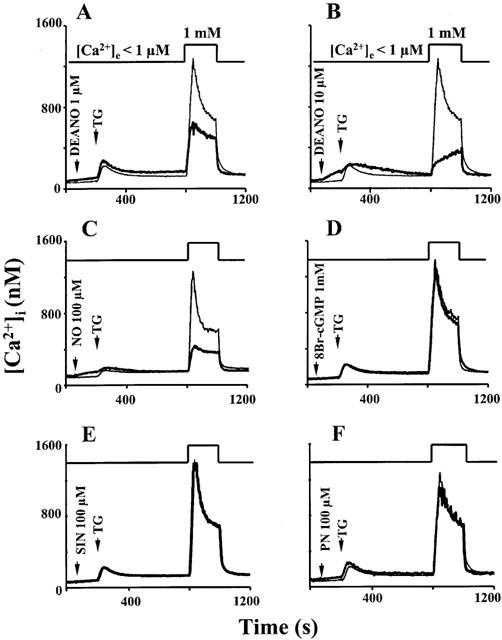

Exposure of HEK293 cells to NO or NO donors (DEANO, ProliNO) inhibited the capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE) induced by thapsigargin (TG) in a classical Ca2+ re-addition protocol. Typical effects of 1 μM and 10 μM DEANO are shown in Figure 1A,B, respectively. Intracellular Ca2+ levels of 713±28 nM (n=12) were measured 3 min after Ca2+ re-addition in the absence of DEANO and 492±36 nM (n=8) and 323±18 nM (n=8) in the presence of 1 μM and 10 μM DEANO, respectively. DEANO did not affect the intracellular Ca2+ signal evoked by TG-induced store depletion in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, but by itself, elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ at higher concentrations (10 μM, Figure 1B). At 10 μM, the NO donor produced a change in the time course of the Ca2+ entry signal in that elevation of intracellular Ca2+ became essentially slow. Figure 1C shows the inhibitory effect obtained when an NO solution was administered (nominally 100 μM). In the presence of NO, intracellular Ca2+ levels were 281±22 nM (n=8) at 3 min after Ca2+ re-addition. The inhibitory effect of NO was not mimicked by 8-Br-cGMP (1 mM, Figure 1D), the peroxynitrite donor SIN-1 (100 μM; Figure 1E) or by authentic peroxynitrite (100 μM; Figure 1F). Moreover, decomposed DEANO (10 μM) and ProliNO (10 μM) did not inhibit TG-induced CCE in HEK 293 cells (not shown, n=3). These results suggested inhibition of CCE by NO via a cGMP and peroxynitrite-independent mechanism. To further test this concept we studied the relation between inhibition of CCE and cellular cGMP levels for the different NO donors and performed experiments with the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ.

Figure 1.

Time courses of [Ca2+]i determined from fura-2 fluorescence. Cells were stimulated with thapsigargin (TG) in Ca2+-free solution, and extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM) was added to induce Ca2+ entry as indicated. Thin lines denote control experiments performed in the absence of drugs, thick lines represent experiments performed in the presence of the indicated compounds (A) DEANO, 1 μM; (B) DEANO, 10 μM; (C) NO in solution, 100 μM; (D) 8-Br-cGMP, 1 mM; (E) SIN-1, 100 μM; (F) peroxynitrite, PN, 100 μM). Data points are mean values derived from 6–15 experiments.

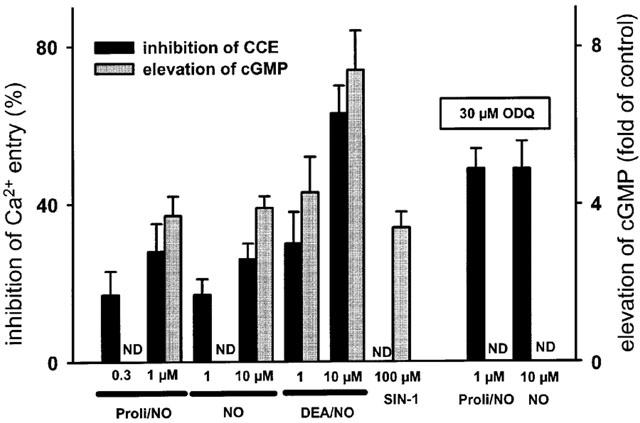

ProliNO is a NONOate that decomposes more rapidly than DEANO. Thus, the actual peak NO concentration obtained with proliNO is expected to be close to the nominal concentration of the NO donor and higher than that obtained with DEANO. The threshold concentration for ProliNO-induced inhibition of CCE, as quantified by changes in cytosolic Ca2+ at 3 min after Ca2+ re-addition to TG-stimulated cells, was slightly lower than that of DEANO (0.3 μM versus 1 μM). At 0.3 μM, ProliNO inhibited CCE significantly but failed to elicit any detectable change in cellular cGMP levels (Figure 2). A similar situation was found with NO in solution at its threshold to produce significant inhibition of CCE (1 μM). By contrast, 100 μM SIN-1 produced a significant elevation of cellular cGMP without any change in CCE. Higher concentrations of ProliNO (1 μM) and NO (nominally 10 μM) induced concomitant changes in CCE and cGMP levels. Preincubation of cells with 30 μM ODQ was sufficient to prevent elevation of cGMP but failed to suppress inhibition of CCE by 1 μM ProliNO and 10 μM NO, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of inhibition of CCE (black columns) and elevation of cGMP levels (grey columns) by NO and NO donors (ProliNO, DEANO and SIN-1). Values obtained with 1 μM ProliNO and 10 μM NO in the presence of the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ are shown in the right panel. Significant elevation of cGMP was not detectable (ND) with 0.3 μM ProliNO, 1 μM NO and in the presence of ODQ. Inhibition of CCE was not detectable (ND) with 100 μM SIN-1. Inhibition of Ca2+ entry was determined from [Ca]i levels measured 3 min after Ca2+ re-addition. Mean values±s.e.mean derived from 4–8 experiments are given, all effects are statistically significant.

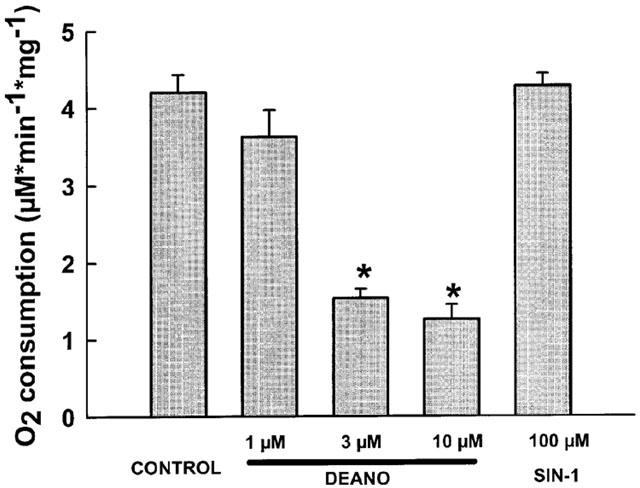

NO reduces oxygen consumption of HEK293 cells

A substantial effect of NO on energy metabolism was evident from experiments measuring oxygen consumption of HEK293 cells. DEANO (1–10 μM) reduced oxygen consumption in a concentration-dependent manner, while SIN-1 (100 μM) did not exert any effect (Figure 3). These results indicate that NO impairs mitochondrial respiration in HEK293 cells by a mechanism independent of peroxynitrite and/or cGMP generation.

Figure 3.

Effects of DEANO (1–10 μM) and SIN-1 (100 μM) on oxygen consumption of HEK293 cells. Mean values±s.e.mean derived from 4–6 experiments are given. *Denotes statistically significant difference at P<0.05 versus control.

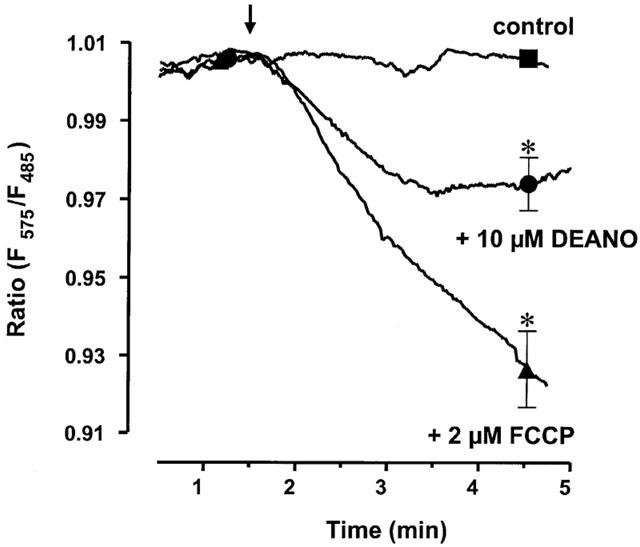

NO depolarizes mitochondria and impairs mitochondrial Ca2+ handling

To test whether NO affects mitochondrial function in HEK293 cells, we first studied the effects of DEANO on mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 as a reporter dye. As illustrated in Figure 4, mitochondrial membrane potential recorded as JC-1 fluorescence was significantly reduced by 10 μM DEANO versus control. The effect of 10 μM DEANO was less pronounced than that of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 μM), a classical uncoupler of mitochondrial function.

Figure 4.

Time courses of mitochondrial membrane potential measured as JC-1 fluorescence during exposure of cells to 10 μM DEANO, 1 μM FCCP or vehicle (control). Mean values of JC-1 fluorescence±s.e.mean at 3 min after administration of drugs or vehicle are given. *Denotes statistically significant difference at P<0.05 versus control.

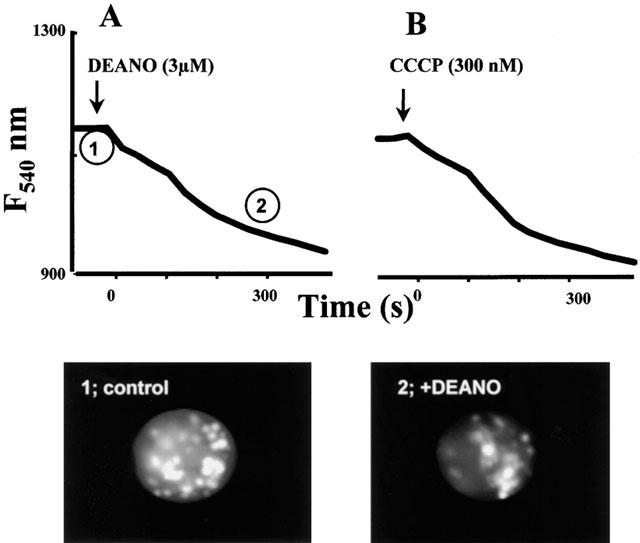

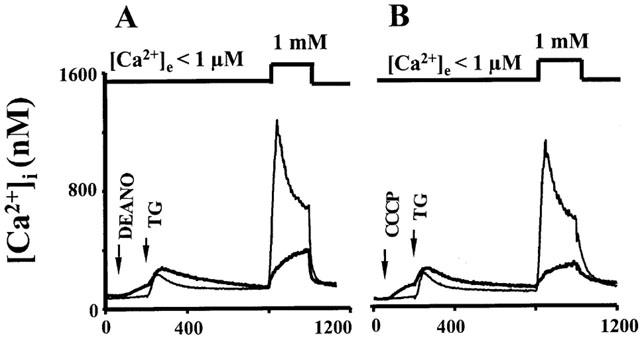

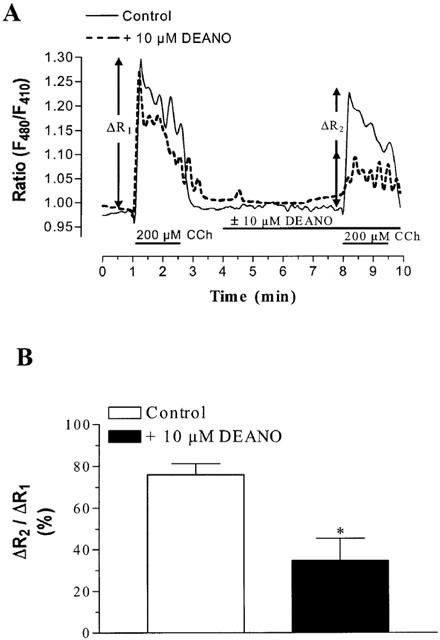

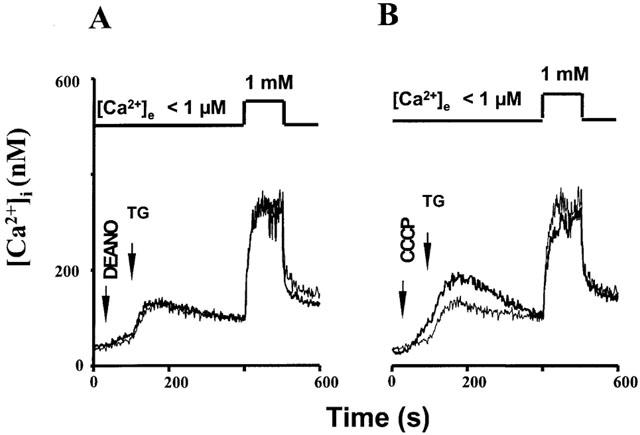

To monitor the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration, cells were loaded with the Ca2+ sensitive dye rhod-2 which accumulates in mitochondria. Rhod-2 fluorescence was localized in discrete spots within the cells. As shown in Figure 5A, 3 μM DEANO caused a rapid decline in rhod-2 fluorescence, an effect that was mimicked by 300 nM of the mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), indicating that the NO donor and the protonophore affect mitochondrial Ca2+ handling to a similar extent at these concentrations. Figure 6A,B compares the effects of 3 μM DEANO and 300 nM CCCP on TG-induced Ca2+ signals. Both agents elicited a slight elevation of basal Ca2+ when administrated in Ca2+-free solution and exerted comparable inhibitory effects on TG-induced CCE. To further test for NO-induced suppression of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling we employed an additional approach based on expression of ratiometric–pericam that is targeted specifically to mitochondria (ratiometric–pericam–mt). HEK293 cells expressing ratiometric–pericam–mt were challenged with carbachol to elicit profound Ca2+ loading of mitochondria, which was detectable by a rise in the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence ratio as shown in Figure 7. This carbachol-induced Ca2+ loading of mitochondria was significantly reduced in the presence of 10 μM DEANO (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Time courses of mitochondrial rhod-2 fluorescence in single HEK293 cells during administration of DEANO (A, 3 μM) and the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP (B, 300 nM). Data points represent the mean derived from 32 and 40 cells, respectively. Lower panel shows typical images corresponding to time points indicated in A.

Figure 6.

Time courses of [Ca2+]i determined from fura-2 fluorescence. Cells were stimulated with thapsigargin (TG) in Ca2+-free solution, and extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM) was added to induce Ca2+ entry as indicated. Thin lines denote control experiments performed in the absence of drugs, thick lines represent experiments performed in the presence of DEANO (A) 3 μM; and CCCP (B) 300 nM. Data points are mean values derived from eight experiments.

Figure 7.

Effects of DEANO (10 μM) on Ca2+ loading of mitochondria during carbachol (CCh; 200 μM) stimulation of HEK293 cells. Mitochondrial Ca2+ was monitored by expression of a ratiometric-pericam that is specifically targeted to mitochondria. (A) Representative time courses of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescence in individual cells with ΔR1 and ΔR2 taken as a measure of the increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ before and after administration of DEANO or vehicle. (B) Effect of 10 μM DEANO on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake calculated as the relation between ΔR1 and ΔR2 for DEANO and vehicle (control), respectively. Mean values±s.e.mean derived from six experiments. *Denotes statistically significant difference at P<0.05 versus control.

Inhibition of capacitative Ca2+ entry channels by NO requires the presence of extracellular Ca2+ and is eliminated by intracellular Ca2+ buffering

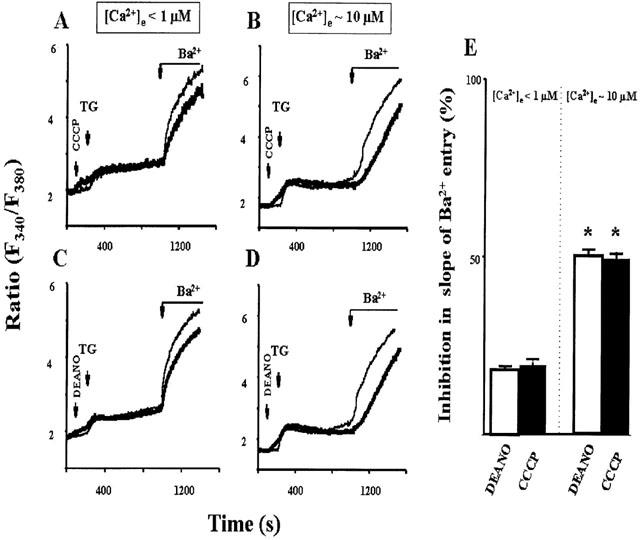

To test the concept that NO inhibits CCE due to impairment of local Ca2+ handling and promotion of Ca2+-mediated autoregulation, we performed experiments with Ba2+ ions which are known to permeate through many Ca2+ entry channels but barely activate negative feedback mechanisms. Neither DEANO (10 μM) nor CCCP (300 nM) inhibited Ba2+ entry when extracellular free Ca2+ was buffered below 1 μM, as predicted for a Ca2+-mediated mechanism (Figure 8A,C). Moreover, the inhibitory action of both agents was regained when extracellular Ca2+ was elevated above 10 μM (Figure 8B, D). Thus, the inhibitory action of both CCCP and the NO donor was Ca2+-dependent. Mean values of the inhibitory effects of both compounds at different extracellular free Ca2+ concentrations are depicted in Figure 8E. Consistent with the hypothesis that both NO and CCCP inhibit CCE due to promotion of an intracellular Ca2+-dependent mechanism, the inhibitory action of both agents was eliminated by preincubation of cells with the cell-permeant Ca2+ chelator BAPTA/AM. Loading of the cells with BAPTA/AM (10 μM) substantially enhances the intracellular Ca2+ buffer capacity whilst still allowing for moderate elevation of fura-2 fluorescence during Ca2+ mobilization and entry. Figure 9 illustrates that in BAPTA/AM-loaded cells, both DEANO and CCCP failed to inhibit TG-induced CCE in HEK293 cells.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of TG-induced Ba2+ entry by DEANO (3 μM) and CCCP (300 nM) at different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (<1 μM: A&C; 10 μM: B&D). Time courses of fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) during stimulation of cells with thapsigargin (TG) and addition of 3 mM Ba2+. Thin lines denote control experiments performed in the absence of drugs, thick lines represent experiments performed in the presence of DEANO (A, 3 μM); and CCCP (B, 300 nM). Data points are mean values derived from 10 experiments (E). Inhibition of the initial rate of Ba2+ entry (calculated from the increase in fluorescence ratio recorded within 1 min upon Ba2+ addition) by DEANO (white columns) and CCCP (black columns). Mean values±s.e.mean derived from 6–8 experiments. *Denotes statistically significant difference at P<0.05 versus control.

Figure 9.

Time courses of [Ca2+]i determined from fura-2 fluorescence. Cells were loaded with BAPTA/AM (10 μM) and stimulated with thapsigargin (TG) in Ca2+-free solution, and extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM) was added to induce Ca2+ entry as indicated. Thin lines denote control experiments performed in the absence of drugs, thick lines represent experiments performed in the presence of DEANO (A; 10 μM) and CCCP (B; 300 nM). Data points are mean values derived from 6–18 experiments. Mean values±s.e.mean are given for n=6–18. *Denotes statistically significant differences at P<0.05 versus control.

Discussion

With the present study we provide evidence for a key role of mitochondria in NO-mediated control of capacitative Ca2+ entry and thus in the coordination of cellular NO and Ca2+ signals. Our results demonstrate for the first time that two previously recognized actions of NO, i.e. modulation of mitochondrial function and inhibition of CCE, are tightly coupled.

NO-induced inhibition of CCE in HEK293 cells is independent of cGMP and peroxynitrite formation

The classical target of NO is soluble guanylyl cyclase (Dierks & Burstyn, 1996), and a variety of biological actions of NO involve cGMP/cGMP-kinase-mediated signal transduction (Looms et al., 2001). Besides this classical signal transduction pathway, NO is known to directly affect other target proteins such as components of the respiratory chain (Brown, 1999) and to exert biological effects due to modification of proteins by S-nitrosation or tyrosine nitration (Hanafy et al., 2001; Poteser et al., 2001). Here, we report that NO as well as NO donors inhibit TG-induced (capacitative) Ca2+ entry (CCE) in HEK293 cells. The rapidly decomposing NO donor ProliNO, which generates peak NO levels close to the donor concentration, exerted significant inhibitory effects at sub-micromolar concentrations, indicating that these rather physiological NO levels are able to affect store operated Ca2+ signaling. High concentrations of NO donors as well as mitochondrial uncouplers gave rise to a moderate elevation of basal intracellular Ca2+ levels and a change in the time course of intracellular Ca2+ during CCE. It remains unclear whether the change in kinetics of the intracellular Ca2+ signals is due to suppression of CCE channel activity below a certain critical level or reflects an additional inhibitory principle of the NO donor.

The inhibitory actions of NO were neither mimicked by 8-Br-cGMP nor by SIN-1, a NO donor that decomposes to produce peroxynitrite resulting in elevated cGMP levels and enhanced protein tyrosine phosphorylation (Takehara et al., 1996). Inhibitory effects of NO and NO donors were not correlated with intracellular cGMP levels. NO and ProliNO inhibited CCE without any detectable increase in cellular cGMP when administrated at threshold concentrations or when higher concentrations were administered in the presence of the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ. Moreover, SIN-1 produced a substantial elevation of cellular cGMP without affecting CCE. These results suggest that NO governs CCE in HEK293 cells by a mechanism independent of cGMP or peroxynitrite formation. The lack of mediator function of peroxynitrite was corroborated by experiments with authentic peroxynitrite. Both NO itself as well as peroxynitrite are known to affect mitochondrial function, albeit in a different manner. NO at physiological levels appears to interact predominantly with cytochrome c oxidase, leading to reduced mitochondrial oxygen uptake and consequently in rather profound alterations in mitochondrial function. By contrast, peroxynitrite is able to cause irreversible oxidative damage of components of the respiratory chain, depending on the effectiveness of mitochondrial scavenging systems, which protect against modification of mitochondrial proteins by peroxynitrite (Radi et al., 2002). The lack of effect of peroxynitrite in the present study indicates a relatively high resistance of mitochondria in HEK293 cells against oxidative modification.

Since a key role of mitochondria in Ca2+ signalling is well established (Werth & Thayer, 1994; Herrington et al., 1996), we were prompted to hypothesize that NO exerts its effect on CCE by modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling.

NO modifies mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in HEK293 cells

An inhibitory effect of DEANO on mitochondrial function was evident from the observed suppression of oxygen consumption. Cellular respiration was suppressed by DEANO but not by SIN-1, indicating that the effect on oxygen consumption was, as that on CCE, not mediated by cGMP or peroxynitrite. Experiments with the fluorescent dyes JC-1 and rhod-2, which report mitochondrial membrane potential and Ca2+ levels, respectively, confirmed the substantial impairment of mitochondrial function by NO. NO reduced mitochondrial membrane potential as evident from a significant reduction of JC-1 fluorescence, and NO-induced reduction of rhod-2 fluorescence indicated suppression of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation. Since rhod-2 fluorescence may be affected to some extent by changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, we set out to test for impairment of mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration by use of an additional, highly specific method for recording of mitochondrial Ca2+. Cells were transfected to express a ratiometric–pericam that is targeted to mitochondria. Measurements of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria by this approach revealed a clear inhibitory effect of NO on mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration. These results are in agreement with previous reports suggesting the ability of NO to decrease mitochondrial Ca2+ levels in hepatocytes and the β-cell lines, INS-1 (Richter et al., 1994; Laffranchi et al., 1995). In principle, the effects of NO on mitochondrial Ca2+ handling may be the consequence of mitochondrial depolarization (Richter et al., 1994) due to inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase (Kushnareva et al., 2001). Consistently, the classical mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, which dissipates mitochondrial H+ gradients and membrane potential mimicked the effects of NO on CCE.

To further analyse the mechanisms that link changes in mitochondrial function to inhibition of CCE, we tested whether a Ca2+-dependent negative feedback regulation of CCE channel is involved.

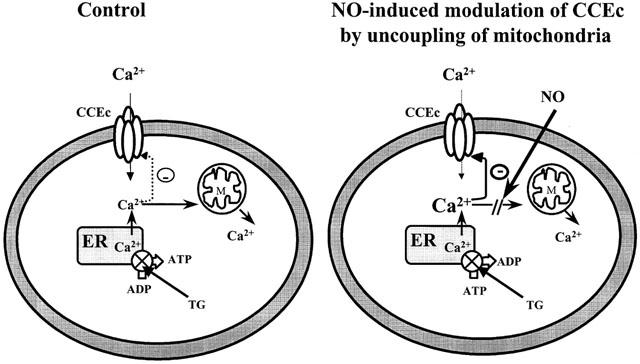

Impairment of mitochondrial function by NO promotes Ca2+-mediated negative feedback regulation of CCE

Functional mitochondria appear to maintain CCE after depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by effective sequestration of subplasmalemmal Ca2+ and by the consequent attenuation of Ca2+-induced inactivation of CCE channels (Hoth et al., 1997). The possible role of Ca2+-mediated inactivation of CCE channels in the inhibitory action of NO was studied by variation of the divalent cations permeating through the CCE channels. Ba2+ is a divalent which is transported well by many Ca2+ entry channels but lacks classical negative feedback effects on the involved transport systems e.g. the voltage-gated L-type channel (Hofer et al., 1997) or capacitative Ca2+ entry channels (Zweifach & Lewis, 1995). Ba2+ entry into TG-stimulated HEK293 cells was completely insensitive to NO. Thus, the regulation of CCE by NO was clearly dependent on the permeant divalent. Addition of Ca2+ ions at micromolar concentrations was sufficient to regain significant inhibitory effects of NO in experiments with Ba2+ as the main extracellular cation. Moreover, attenuation of intracellular Ca2+ rises by use of BAPTA/AM eliminated the inhibitory effects of NO. Although elevation of basal Ca2+ at the inner mouth of CCE channels may not be prevented completely by BAPTA/AM, sub-plasmalammal Ca2+ gradients are most likely blunted. Modulation of intracellular Ca2+ gradients by use of Ba2+ as substrate for divalent cation entry or BAPTA/AM as intracellular Ca2+ buffer is expected to affect a variety of cellular signalling processes. Thus, the results from these experiments need to be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, our results strongly suggest Ca2+ dependence of CCE inhibition by NO and indicate an involvement of Ca2+-dependent feedback regulation of CCE channels. Based on this hypothesis we propose a novel concept (Figure 10) in which NO-induced impairment of mitochondrial functions causes a substantial promotion of Ca2+-mediated feedback inhibition of CCE. This feedback regulation is unlikely to involve facilitated refilling of the regulatory Ca2+ store since refilling of stores was effectively prevented in our experiments by thapsigargin. The role of mitochondria in NO-induced modulation of Ca2+ signals which are initiated by phospholipase C-dependent depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores remains to be clarified. Since mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake has been recognized as a key determinant of the spatiotemporal organization of IP3-induced cytosolic Ca2+ responses (Hajnoczky et al., 2000), it is tempting to speculate that impairment of mitochondrial function by NO represents an effective mechanism for the control of phospholipase C-dependent Ca2+ signalling. NO-induced suppression of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria during phospholipase C stimulation may affect agonist-induced Ca2+ entry not only by promotion of Ca2+-dependent feedback regulation of CCE channels but also by incomplete discharge and/or enhanced filling of the stores.

Figure 10.

Mitochondria are proposed to function as a sink that reduces the Ca2+ concentration close to cytoplasmic face of CCEC. NO as well as CCCP inhibit mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and increase Ca2+ concentrations in regions close to cytoplasmic face of CCEC. The resulting accumulation of local Ca2+ promotes Ca2+-induced negative feedback regulation of CCEC.

With the present study we provide evidence for a role of mitochondria as a link between NO and Ca2+ signalling. Since capacitative Ca2+ entry is a rather ubiquitous Ca2+ signalling mechanism which appears of importance for both excitable as well as non-excitable cells (Philipp et al., 1998; Freichel et al., 1999) it is tempting to speculate that the proposed mitochondrial-based crosstalk between NO and CCE is a general regulatory principle. We propose the spatial and functional relation between mitochondria and Ca2+ entry channels as a key determinant of the sensitivity of capacitative Ca2+ entry to NO.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Atsushi Miyawaki from the Laboratory for Cell Function and Dynamics, Advanced Technology Development Center, Brain Science Institute, Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN), Saitama, Japan very much for kindly providing us the ratiometric-pericam-mt. Supported by the Austrian Science Funds (P-14950 and SFB-715 to K. Groschner; P-14586-PHA and SFB-714 to W.F. Graier).

Abbreviations

- BAPTA/AM

N,N′-[1,2-ethanediylbis(oxy-2,1-phenylene)]

- bis [N-[25-[(acetyloxy) methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]]-

bis[(acetyloxy)methyl] ester

- 8-Br-cGMP

8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- [Ca2+]e

extracellular Ca2+ concentration

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- [Ca2+]m

mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone

- CCE

capacitative Ca2+ entry

- CCEC

capacitative Ca2+ entry channels

- DEANO

2-(N,N-diethylamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide sodium salt

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone

- fura-2/AM

5-Oxazolecarboxylic acid, 2-[6-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-5-[2-[2-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-5-methylphenoxy]ethoxy]-2-benzofuranyl]-, (acetyloxy)methyl ester

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- JC-1

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-benzimidazolyl-carbocyanide iodine

- M

mitochondria

- NO

nitric oxide

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazole[4,3-1] quinoxalin-1-one

- ProliNO

1-[2-(carboxylato)-pyrrolidin-1-yl]diazem-1-ium-1,2-diolate

- rhod-2/AM

Xanthylium, 9-[4-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]amino]-3-[2-[2-[bis[2-[(acetyloxy)methoxy]-2-oxoethyl]-amino]phenoxy]ethoxy]phenyl]-3.6-bis(dimethylamino)- bromide

- SERCA

sarco (endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATP-ase

- SIN-1

3-morpholino-sydnonimine

- TG

thapsigargin

References

- BISCHOF G., BRENMAN J., BREDT D.S., MACHEN T.E. Possible regulation of capacitative Ca2+ entry into colonic epithelial cells by NO and cGMP. Cell Calcium. 1995;17:250–262. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN G.C. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1411:351–369. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMENTI E. Role of nitric oxide and its intracellular signaling pathways in the control of Ca2+ homeostasis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:713–718. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMENTI E., MELDOLESI J. The cross-talk between nitric oxide and Ca2+: a story with a complex past and a promising future. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:266–269. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN R.A., WEISBROD R.M., GERICKE M., YAGHOUBI M., BIERL C., BOLOTINA V.M. Mechanism of nitric oxide-induced vasodilatation. Refilling of intracellular stores by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase and inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ influx. Circ. Res. 1999;84:210–219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIERKS E.A., BURSTYN J.N. Nitric oxide (NO), the only nitrogen monoxide redox form capable of activating soluble guanylyl cyclase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FASOLATO C., HOTH M., PENNER R. A GTP-dependent step in the activation mechanism of capacitative calcium influx. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:20737–20740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREICHEL M., SCHWEIG U., STAUFFENBERGER S., FREISE D., SCHORB W., FLOCKERZI V. Store-operated cation channels in the heart and cells of the cardiovascular system. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 1999;9:270–283. doi: 10.1159/000016321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEDEN M., MALLI R., SAMARDZIJA M., DEMAUREX N., GRAIER W.F. Subplasmalemmal endoplasmic reticulum controls KCa channel activity upon stimulation with moderate histamine concentration in a human umbilical vein endothelial cell line. J. Physiol. 2002;544:73–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAIER W.F., PALTAUF D.J., HILL B.J., FLEISCHHACKER E., HOEBEL B.G., KOSTNER G.M., STUREK M. Submaximal stimulation of porcine endothelial cells causes focal Ca2+ elevation beneath the cell membrane. J. Physiol. 1998;506:109–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.109bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYNKIEWICZ G., POENIE M., TSIEN R.Y. New generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUKOVSKAYA A., PANDOL S. Nitric oxide production regulates cGMP formation and calcium influx in pancreatic acinar cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:G350–G356. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.3.G350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAJNOCZKY G., CSORDAS G., KRISHNAMURTHY R., SZALAI G. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling driven by the IP3 receptor. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32:15–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1005504210587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANAFY K.A., KRUMENACKER J.S., MURAD F. NO, nitrotyrosine, and cGMP in signal transduction. Med. Sci. Monitor. 2001;7:801–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERRINGTON J., PARK Y.B., BABCOCK D.F., HILLE B. Dominant role of mitochondria in clearance of large Ca2+ loads from rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1996;16:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFER G.F., HOHENTHANNER K., BAUMGARTNER W., GROSCHNER K., KLUGBAUER N., HOFMANN F., ROMANIN C. Intracellular Ca2+ inactivates Ca2+ channels with a Hill coefficient of approximately 1 and inhibition constant of approximately 4 μM by reducing channel's open probability. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1857–1865. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78216-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOTH M., BUTTON D.C., LEWIS R.S. Mitochondrial control of calcium-channel gating: A mechanism for sustained signaling and transcriptional activation in T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:10607–10612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180143997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOTH M., FANGER C.M., LEWIS R.S. Mitochondrial regulation of store-operated calcium signalling in T lymphocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:633–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAUSE E., SCHMID A., GONZALEZ A., SCHULZ I. Low cytoplasmic [Ca2+] activates I(CRAC) independently of global Ca2+ store depletion in RBL-1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36957–36962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUKOVETZ W.R., HOLZMANN S. Tolerance and cross-tolerance between SIN-1 and nitric oxide in bovine coronary arteries. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1989;14:S40–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSHNAREVA Y.E., POLSTER B.M., SOKOLOVE P.M., KINNALLY K.W., FISKUM G. Mitochondrial precursor signal peptide induces a unique permeability transition and release of cytochrome c from liver and brain mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;386:251–260. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAFFRANCHI R., GOGVADZE V., RICHTER C., SPINAS G.A. Nitric oxide (nitrogen monoxide, NO) stimulates insulin secretion by inducing calcium release from mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;217:584–591. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWRIE A.M., RIZZUTO R., POZZAN T., SIMPSON A.W.M. A role for calcium influx in the regulation of mitochondrial calcium in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:10753–10759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOOMS D.K., TRITSARIS K., NAUNTOFTE B., DISSING S. Nitric oxide and cGMP activate Ca2+-release processes in rat parotid acinar cells. Biochemical Journal. 2001;355:87–95. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKOWSKA A., ZABLOCKI K., DUSZYNSKI J. The role of mitochondria in the regulation of calcium influx into Jurkat cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:877–884. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAI T., SAWANO A., PARK E.S., MIYAWAKI A. Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+ Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:3197–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051636098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALTAUF-DOBURZYNSKA J., FRIEDEN M., SPITALER M., GRAIER W.F. Histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations in a human endothelial cell line depend on transmembrane ion flux, ryanodine receptor and SERCA. J. Physiol. 2000;524:501–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILIPP S., HAMBRECHT J., BRASLAVSKI L., SCHROTH G., FREICHEL M., MURAKAMI M., CAVALIE A., FLOCKERZI V. A novel capacitative calcium entry channel expressed in excitable cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:4274–4282. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POTESER M., ROMANIN C., SCHREIBMAYER W., MAYER B., GROSCHNER K. S-nitrosation controls gating and conductance of the alpha 1 subunit of class C L-type Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14797–14803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTNEY J.W., JR A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTNEY J.W., JR Capacitative calcium entry revisited. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:611–624. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90016-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTNEY J.W., JR Kissin' cousins: intimate plasma membrane-ER interactions underlie capacitative Ca2+ entry. Cell. 1999;99:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTNEY J.W., JR, BROAD L.M., BRAUN F.J., LIEVREMONT J.P., BIRD G.S. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2223–2229. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADI R., CASSINA A., HODARA R. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite interactions with mitochondria. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:401–409. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANDRIAMAMPITA C., TSIEN R.Y. Emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores releases a novel small molecule that stimulates Ca2+ influx. Nature. 1993;364:809–814. doi: 10.1038/364809a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHTER C., GOGVADZE V., SCHLAPBACH R., SCHWEIZER M., SCHLEGEL J. Nitric oxide kills hepatocytes by mobilizing mitochondrial calcium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;205:1143–1150. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZUTO R., BASTIANUTTO C., BRINI M., MURGIA M., POZZAN T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in intact cells. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:1183–1194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZUTO R., BRINI M., MURGIA M., POZZAN T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighbouring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUTTER G.A., THELER J.M., MURGIA M., WOLLHEIM C.B., POZZAN T., RIZZUTO R. Stimulated Ca2+ influx raises mitochondrial free Ca2+ to supramicromolar levels in a pancreatic beta-cell line. Possible role in glucose and agonist-induced insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22385–22390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT K., MAYER B., KUKOVETZ W.R. Effect of calcium on endothelium-derived relaxing factor formation and cGMP levels in endothelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;170:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEHARA Y., NAKAHARA H., INAI Y., YABUKI M., HAMAZAKI K., YOSHIKO T., INOUE M., HORTON A.A., UTSUMI K. Oxygen-dependent reversible inhibition of mitochondrial respiration by nitric oxide. Cell Struct. Funct. 1996;21:251–258. doi: 10.1247/csf.21.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TREPAKOVA E.S., COHEN R.A., BOLOTINA V.M. Nitric oxide inhibits capacitative cation influx in human platelets by promoting sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase-dependent refilling of Ca2+ stores. Circ. Res. 1999;84:201–209. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON E.L., JACOBSON K.L., SINGH J.C., OTT S.M. Nitric oxide acts independently of cGMP to modulate capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse parotid acini. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:C262–C270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAYMAN C.P., MCFADZEAN I., GIBSON A., TUCKER J.F. Inhibition by sodium nitroprusside of a calcium store depletion-activated non-selective cation current in smooth muscle cells of the mouse anococcygeus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:2001–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERTH J.L., THAYER S.A. Mitochondria buffer physiological Ca2+ loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:348–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZWEIFACH A., LEWIS R.S. Rapid inactivation of depletion-activated calcium current (ICRAC) due to local calcium feedback. J. Gen. Physiol. 1995;105:209–226. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]