Abstract

Well-characterized in vivo and in vitro models exist for the study of ischaemia- and infarction-related ventricular fibrillation (VF). In rats in vivo, VF appears to occur in distinct acute ischaemia- (early) and infarction-related (late) phases. Interestingly, isolated buffer-perfused rat hearts do not develop late VF. This raises the possibility that unidentified components of the blood may be responsible for late VF. We thus sought to characterize an isolated blood-perfused rat heart in order to investigate the possible influence of blood components on arrhythmias arising from ischaemia and infarction.

Hearts, excised from male Wistar rats, were perfused in the Langendorff mode with blood from support rats (male Wistar, 350–430 g) via an extracorporeal circuit. Perfused hearts underwent left coronary artery occlusion for 240 min or a sham procedure (n=10 group−1).

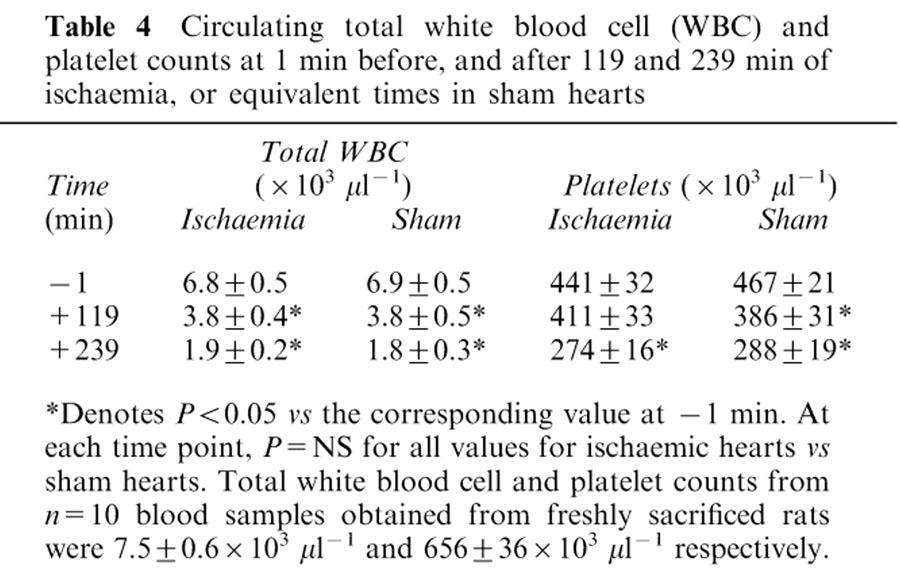

Only 10% of ischaemic hearts developed late VF (90–240 min). Tissue myeloperoxidase activity (an index of neutrophil accumulation) increased during ischaemia from 0.017±0.004 (six fresh hearts) to 0.056±0.005 units mg protein−1 (P<0.05) at 240 min, but values were similar in sham hearts (0.083±0.013). Likewise, the decline (−1 vs 240 min of ischaemia shown) in circulating total white blood cells from 6.8±0.5 to 1.9±0.2×103 μl−1 and in platelets from 441±32 to 274±16×103 μl−1 (both P<0.05) was similar in time-matched sham hearts (data not shown).

Surprisingly, only 10% of ischaemic hearts developed early VF (0–90 min), although the incidence of early ventricular tachycardia was 100% in these hearts (P<0.05 vs sham hearts). Blood K+ values were normal (hyperkalaemia suppresses VF).

Although late VF was absent in blood-perfused hearts, it would be premature to conclude from this that late VF is not mediated by blood components. This is because the similar neutrophil accumulation in ischaemic and sham hearts, the decline in numbers of circulating blood components, and the unexpected paucity of early VF all question the validity of the model.

Keywords: Arrhythmias, blood, heart, ischaemia, neutrophil, platelets, rat, ventricular fibrillation

Introduction

Currently there are no effective drug treatments to prevent sudden cardiac death resulting from ventricular fibrillation (VF) (CAST, 1989; Waldo et al., 1996). Reliable in vivo and in vitro animal models are therefore required for the study of VF in ischaemic heart disease, its mediators, and the effects of experimental anti-arrhythmic drugs (Walker et al., 1988). Conscious and anaesthetized rats (Clark et al., 1980; Johnston et al., 1983; see Curtis et al., 1987 for review) and in vitro buffer-perfused rat hearts (Curtis & Hearse, 1989a) are established and well characterized models, in which the temporal distribution of VF following coronary occlusion is well defined (Curtis, 1998). Rats in vivo subjected to permanent coronary artery ligation exhibit two distinct phases of VF. Early (or phase 1) VF, which may itself have subcomponents, occurs during the first 30 min of ischaemia and, following a period of relative electrical stability, late (or phase 2) VF occurs between 2 and 4 h after the onset of ischaemia, during the period when infarction is developing (Clark et al., 1980; Johnston et al., 1983).

The mechanisms of early VF have been extensively studied, and are thought to involve (at the electrophysiological level) re-entry and flow of injury current (Janse, 1991), and (at the biochemical level) the actions of regional hyperkalaemia (Harris et al., 1954) and various other intercellular biochemicals such as platelet activating factor (see Curtis et al., 1993 for review). VF susceptibility during the first 30 min of ischaemia in isolated (denervated) perfused hearts is similar to the susceptibility in vivo (Curtis, 1998). Thus, early VF does not appear to be dependent on an intact autonomic nervous system. In contrast, the mechanisms and mediators of late VF remain to be established.

Interestingly, the blood-free buffer-perfused rat heart does not develop late VF, despite unequivocal evidence of infarct development (Ravingerova et al., 1995). Recent studies have shown that the lack of sympathetic drive is not sufficient to account for the lack of late VF in the buffer-perfused heart (Clements-Jewery et al., 2002). This suggests that other factors, possibly components of the blood, may be necessary mediators of infarction-related VF. In this regard, a selective accumulation of neutrophils in the ischaemic zone of coronary ligated hearts during sustained ischaemia in vivo has been reported (Allan et al., 1985; Engler et al., 1986; Mullane et al., 1985), and the time course of the accumulation (Entman et al., 1993) appears to overlap with that of susceptibility to late VF (Clark et al., 1980).

In order to investigate the role of blood components in mediating late VF, we used the isolated blood-perfused rat heart preparation. However, although this is an established model for study of cardiac pathophysiological phenomena such as ischaemia/reperfusion-mediated injury and preconditioning (Galinanes et al., 1993, 1996; Kolocassides et al., 1995), it has been little utilized for the study of cardiac arrhythmias. Therefore, in the present study we assessed the susceptibility of the isolated blood-perfused rat heart to development of early and late VF by examining the temporal distribution of arrhythmias during 4 h of regional ischaemia. The levels of circulating blood components, the accumulation of neutrophils in cardiac tissue, and cardiac haemodynamics during the same period permitted an evaluation of the model's applicability for the study of ischaemia- and infarction-related VF and the role of blood components as mediators of late VF.

Methods

Animals and general experimental methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office Guide on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

The isolated blood-perfused heart (and the rat from which it was excised) and the support rat are referred to as the donor heart/rat and the support rat, respectively. The heart isolation and perfusion procedure were similar to those described in previous studies (Galinanes et al., 1993; Hearse et al., 1999; Kolocassides et al., 1995).

Male Wistar support rats (Bantin & Kingman, UK; 370–430 g) were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (60 mg kg−1 i.p.) and given heparin (1000 IU kg−1 i.v.) to prevent blood coagulation. Ventilation was not required since all support rats were able to breathe spontaneously. The right femoral vein and left femoral artery were exposed by blunt dissection and cannulated (18G and 22G Abbocath-T catheters respectively) to enable supply of blood to the perfused donor heart and its return back into the circulation. An extracorporeal circuit was established, primed with 10 ml Gelofusine® (a plasma substitute used clinically, consisting of 4% w v−1 succinylated gelatin, 144 mM Na+, 120 mM Cl− dissolved in water; pH 7.4±0.3 and osmolarity 274 mOsm l−1; B. Braun Medical Ltd, U.K.), and maintained for 20 min prior to cannulation of the donor heart. Gelofusine® was used in preference to heparinized blood since this would have necessitated sacrifice of another rat to procure the blood. Gelofusine® has been used previously in this model (Hearse et al., 1999) and has been shown to improve haemodynamics and oxygen transport in a canine model of haemorrhagic shock (Tait & Larson, 1991). Blood from the arterial limb was passed through a peristaltic pump (Gilson Minipuls 3) and flow was increased gradually over 10 min to a value of 2.3 ml min−1, preventing the sudden drop in arterial pressure that would result if a flow rate of 2.3 ml min−1 were established immediately. Blood was passed through a steel cannula (for connection of the donor heart) and returned, by gravity, via a reservoir and gauze filter to the venous inflow line of the support rat. The total volume of the extracorporeal circuit was 7–12 ml (3.5 ml in the arterial limb, and 4–8 ml in the venous limb depending on the level of the reservoir). The support animal was placed supine on a thermostatically controlled surface to maintain a body temperature of 36–37°C (monitored by a rectal thermometer), and was allowed to breathe a mixture of 95% O2/5% CO2 through a 35% Venturi face mask. Anaesthesia was maintained with sodium pentobarbitone administered when needed as a bolus (0.05–0.1 ml of 60 mg ml−1) into the venous reservoir. Blood pressure was monitored by means of a pressure transducer (Becton Dickinson DTX™ Plus) attached to the arterial line. Perfusion pressure was monitored via a similar pressure transducer connected to a side arm of the aortic cannula.

A second rat (male Wistar; 270–330 g) was then anaesthetized with sodium pentobaribitone (60 mg kg−1 i.p.) and given 1000 IU kg−1 i.v. heparin and sacrificed by cardiac excision for provision of a donor heart for blood perfusion. After excision, the heart was placed into ice-cold bicarbonate buffer containing (in mM): NaCl 118.5, NaHCO3 25.0, MgSO4 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.4, KCl 3.0 and glucose 11.1 (all salts were obtained from BDH chemicals, U.K.). Water for preparing the buffer was supplied using a reverse osmosis system (USF Elga Ltd, U.K.), and had a specific resistivity of greater than 18 MΩ. The heart was cannulated and perfused in the Langendorff mode with arterial blood, and a constant initial pressure of 60 mmHg was maintained using a peristaltic pump (see above) controlled by a custom-built feedback circuit which allows perfusion at either constant flow or constant pressure (Shattock et al., 1997). In order to prevent cardiac cooling, if flow during constant pressure perfusion fell below 0.3 ml min−1 with 90 min or more of the protocol to be completed, perfusion was switched to constant flow (1–3 ml min−1 g−1), and perfusion pressure was recorded. 11 out of 20 hearts (eight ischaemic, three sham) were perfused at constant flow at some point during the protocol for this reason.

A traction-type coronary occluder (Rushmer et al., 1963) consisting of a silk suture (Mersilk, 4/0) threaded through a polythene guide was used for coronary occlusion in the blood-perfused heart. The suture was positioned loosely around the left anterior descending coronary artery beneath the left atrial appendage. Regional ischaemia was induced by tightening the occluder. Sham hearts were included in the protocol; the procedure was identical except that the occluder was not tightened. Blood (3–4 ml) was taken from the donor rat, from the venous pool arising immediately following cardiac excision, to supplement the venous reservoir. The ratio of Gelofusine® to added heparinized blood was therefore approximately 3 : 1. A unipolar electrocardiogram (ECG), made from a Powerlab 3 lead animal ECG but modified so that the positive electrode was replaced with a silver wire that could be inserted into the left ventricular wall, was used for recording and assessment of arrhythmias.

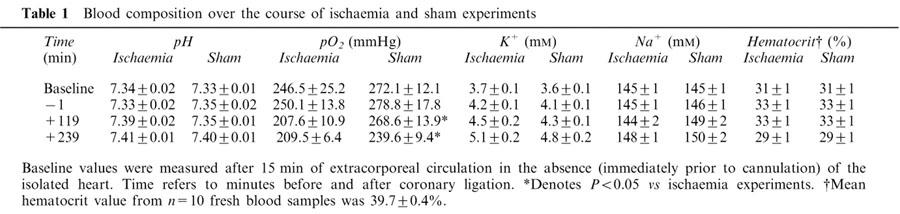

Blood samples (0.9 ml each) were taken from a side arm to the aortic cannula before the donor heart was connected to the circuit (mean time from establishment of the extracorporeal circuit to cannulation of the isolated heart was 2077±41 s), 1 min before coronary occlusion, and after 120 and 240 min of ischaemia, and after equivalent times in sham hearts. Samples were removed slowly over 1–2 min so as to minimize changes in support rat blood pressure, and venous return was increased slightly to offset the blood volume loss. Thus a total of 2.7 ml was removed from the extracorporeal circuit over the course of the protocol, with the final 0.9 ml sample taken immediately prior to termination of the experiment. The total thus represents less than 10% of the total volume of the circuit, if the initial volume of Gelofusine® priming the circuit was 10 ml, and the mean blood volume of the support rats is estimated to be 26.0±0.3 ml (mean weight of the support rats was 0.372±0.005 kg; blood volume is assumed to be approximately 70 ml kg−1). Samples were analysed for blood gas, pH, haematocrit and electrolyte levels by a Stat Profile 9 Blood Gas Analysis machine (Nova Biomedical). Values are given in Table 1. Leukocyte and platelet counts were performed on the same blood samples using Beckman-Coulter Gen-s machines for haematological analysis.

Table 1.

Blood composition over the course of ischaemia and sham experiments

Gelofusine® (or saline in a separate group of hearts described later) was added to the extracorporeal circuit to replace fluid loss by topping up the venous reservoir when required. This was necessary for regulation of venous return in order that changes to the cardiac output and blood pressure of the support rat could be minimized. The average volume added to the extracorporeal circuit during the course of extracorporeal circulation (approximately 270 min) was 7±1 ml. Haematocrit values (Table 1) were well maintained, however, suggesting that the added Gelofusine® did not greatly dilute the blood.

Measurement of the size of the ischaemic zone and coronary flow

The ischaemic zone was identified by visual inspection at the end of the experiment, excised, and quantified as per cent of total ventricular weight. The ischaemic tissue was much darker than non-ischaemic tissue, and in the experience of the experimental operator, its shape and location was similar to that from 50 historical buffer-perfused hearts (Clements-Jewery et al., 2002) in which the ischaemic zone had been identified by a dye exclusion method (Curtis & Hearse, 1989b). Coronary flow was continuously monitored by the calibrated voltage signal controlling the peristaltic pump (i.e. the voltage required to maintain a pressure of 60 mmHg). Values of coronary flow per gram of tissue were calculated from the total coronary flow and the weights of the ischaemic and non-ischaemic zones, as described previously (Curtis & Hearse, 1989b). Flow in ml min−1 g−1 of perfused tissue takes into account any differences in weight and ischaemic zone size between individual hearts. Because measurement of coronary flow values was complicated by the perfusion of some hearts at constant flow during the protocol, for clarity, values of coronary vascular resistance (defined as the perfusion pressure divided by coronary flow) were calculated. This variable provides a measure of coronary vascular function independently of the means of perfusion.

Arrhythmia diagnosis and ECG analysis

The ECG was recorded using a PowerLab system (AD Instruments), and was used to assess arrhythmias in accordance with the Lambeth Conventions (Walker et al., 1988). Ventricular premature beats (VPBs) were defined as premature QRS complexes occurring independently of a P wave, and hence mean values included individual VPBs, bigeminy and salvos as defined by the Lambeth Conventions. The number of VPBs occurring during a specified time period in each heart was log10 transformed to produce a Gaussian-distributed variable for calculation of group mean values (Johnston et al., 1983). QT intervals at the point of 90% repolarization (QT90), heart rate and PR intervals were also measured from the ECG, as previously described (Ridley et al., 1992). The ECG was recorded at a sampling rate of 1 kHz, allowing millisecond precision for measurement of ECG intervals.

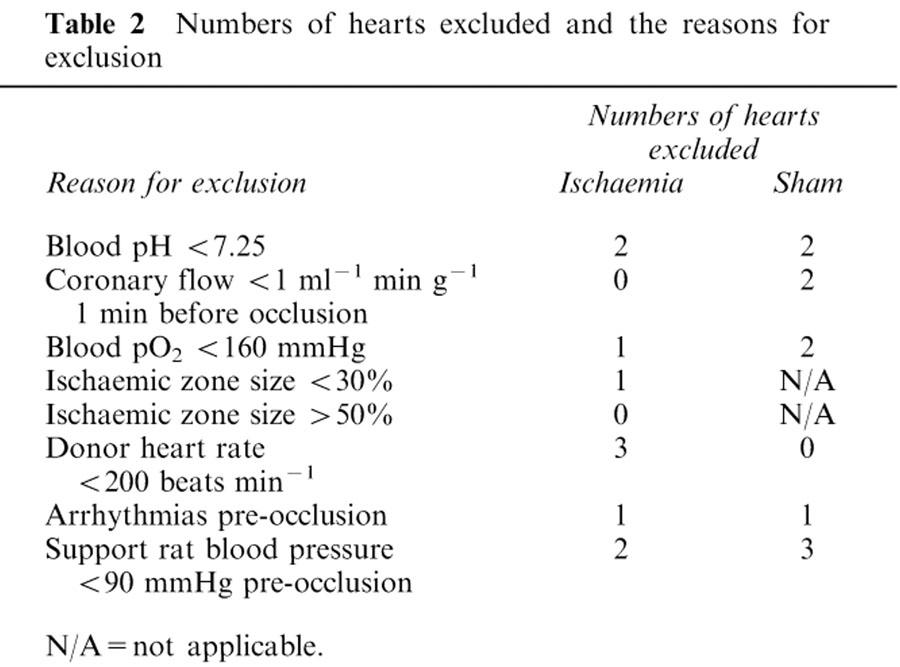

Exclusion criteria

Any heart with a sinus rate of <200 beats min−1, a coronary flow <1 ml min−1 g−1 at 1 min before the onset of ischaemia, or with an ischaemic zone of <30% or >55% of total ventricular weight, was excluded. Hearts were also excluded if more than 5 VPBs, or one or more episode of more serious ventricular arrhythmias such as salvos, ventricular tachycardia (VT) or VF occurred during the 5 min period prior to occlusion (or equivalent period in shams), or if the following variables were outside the normal range or lower limit (pH <7.25 or >7.40; arterial pO2<160 mmHg; haematocrit <27%). Time-matched sham hearts were excluded if they failed to meet the pre-ligation criteria. Support animals (and the hearts their blood was perfusing) were excluded if they did not attain a stable mean blood pressure ⩾90 mmHg during the 5 min prior to coronary occlusion. Numbers of hearts excluded and the reasons for their exclusion are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Numbers of hearts excluded and the reasons for exclusion

Assessment of cardiac myeloperoxidase content

After termination of perfusion, cardiac myeloperoxidase (MPO) content, an index of neutrophil accumulation, was assessed according to the method of Mullane et al. (1985). All the reagents used were obtained from Sigma (U.K.). Samples of left and right ventricular tissue (from shams) or ischaemic and non-ischaemic tissue were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Cardiac tissue samples were homogenized in 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HETAB) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6), in the ratio 1 ml HETAB 100 mg−1 tissue. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 13,000×g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatant samples were frozen at −80°C until the time of assay where-upon thawed samples were kept on ice. To measure supernatant MPO activity, 50 μl of each sample was added to 50 μl of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (0.025% in phosphate buffer with 0.5% HETAB) in a 96-well plate. The reaction was started by addition of 50 μl of 0.01% hydrogen peroxide and the increase in optical density at 510 nm was measured over 3 min. Duplicates were run for each sample, and the average value used to calculate the number of units of MPO present by interpolation with a standard curve established using dilutions of a commercially available preparation of human neutrophil MPO (Sigma Myeloperoxidase: 1 unit is defined as causing an increase in optical density of 1 min−1 at pH 7 at 25°C with guaiacol substrate). Protein in the supernatant was then determined according to the method of Smith et al. (1985) in preference to the method of Lowry et al. (1951), since the bicinchoninic acid method is reliable, less technically complicated than the Lowry method, and not subject to the same interferences from non-ionic detergents and simple buffer salts (Smith et al., 1985). The colour produced from the formation of the bicinchoninic acid reaction with cuprous ion is stable and increases in a proportional fashion over a broad range of increasing protein concentrations. Duplicates were run for each sample, and the average value used for calculation of protein content. MPO concentration was expressed as units MPO mg protein−1.

Statistics

Gaussian distributed variables (expressed as mean±s.e.mean), were subjected to analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's tests where appropriate. Binomially distributed variables were compared using Mainland's contingency tables (Mainland et al., 1956) as previously described (Curtis et al., 1989a). P<0.05 was taken as indicative of a statistically significant difference between values. Arrhythmia incidences were expressed as the percentage of hearts in each group experiencing each arrhythmia during specified time intervals, in order to reveal the temporal pattern of arrhythmogenesis.

Results

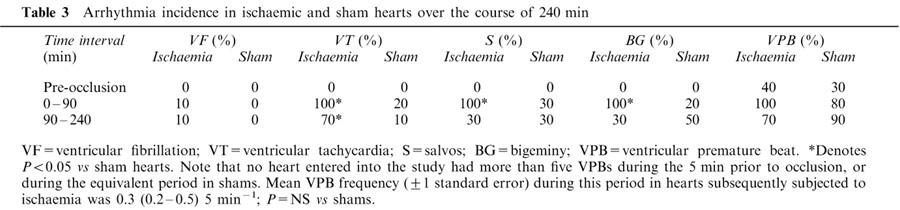

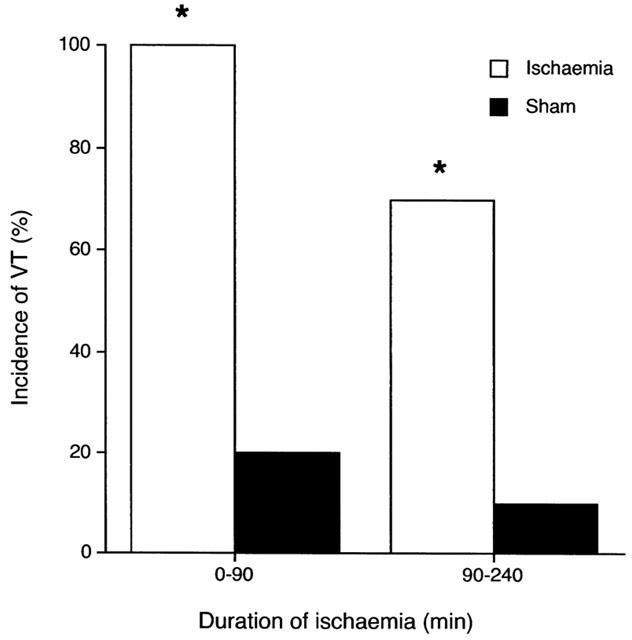

Incidence of late phase arrhythmias and ischaemic zone size

Late VF (90–240 min) occurred in only 10% of ischaemic hearts (Table 3) despite an ischaemic zone size (41±3% of total ventricular weight) similar to that which in vivo is associated with an incidence of late VF approaching 100% (e.g., Johnston et al., 1983; Curtis & Walker, 1988a). There was a greater incidence of ventricular tachycardia (VT) in ischaemic hearts compared with sham hearts during the late phase period (P<0.05; Table 3 and Figure 1). Other arrhythmia incidences were not different compared with sham hearts in the 90–240 min period (Table 3).

Table 3.

Arrhythmia incidence in ischaemic and sham hearts over the course of 240 min

Figure 1.

Incidence of ventricular tachycardia (VT) during the early (0–90 min) and late (90–240 min) periods of ischaemia. *Denotes P<0.05 vs shams. Although episodes of arrhythmias did occur in some sham hearts, the total number of these episodes was much less frequent than in ischaemic hearts (see VPB frequency, Figure 4). No sham hearts developed VF.

Tissue myeloperoxidase activity

Tissue myeloperoxidase activity increased during ischaemia from 0.017±0.004 (left ventricular tissue from n=6 fresh hearts) to 0.056±0.005 units mg protein−1, (Figure 2; P<0.05) at 240 min but values were similar in left ventricular tissue from sham hearts (0.083±0.013; P<0.05 vs fresh hearts). There was a similar increase in MPO activity from 0.027±0.006 (right ventricular tissue from fresh hearts) to 0.066±0.011 units mg protein−1 in non-ischaemic tissue from ligated hearts, and the increase was not significantly different compared with that in right ventricular tissue from sham hearts (0.088±0.020).

Figure 2.

Cardiac tissue myeloperoxidase activity in n=6 fresh hearts and n=10 ischaemic and sham hearts respectively. LV=left ventricle, RV=right ventricle, IZ=ischaemic zone, NZ=nonischaemic zone. *Denotes P<0.05 vs the corresponding fresh heart sample group.

Blood leukocyte and platelet content

The total circulating white blood cell and platelet count declined over 240 min of ischaemia (Table 4; both P<0.05). However, there was a similar decline in time matched sham experiments, and there were no significant differences between ischaemic hearts and shams at any time point (Table 4). Initial values for circulating white blood cells and platelets were less than those in blood samples obtained from freshly sacrificed rats (see legend to Table 4; P<0.05). Circulating blood was diluted by a factor of ∼20% by priming the extracorporeal circuit with Gelofusine®, as indicated by the reduction in haematocrit values in circulating blood (Table 1) compared with blood samples from a separate contemporaneous group of 10 freshly sacrificed rats (31±1 vs 39.7±0.4% respectively; P<0.05).

Table 4.

Circulating total white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts at 1 min before, and after 119 and 239 min of ischaemia, or equivalent times in sham hearts

Haemodynamic and ECG variables

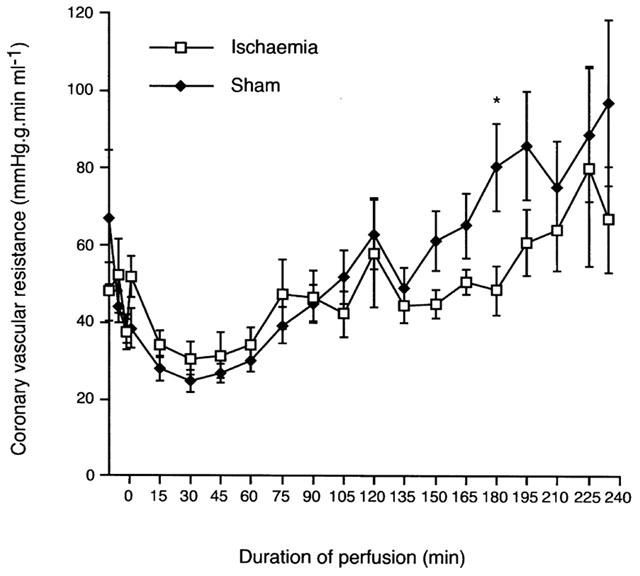

Heart rate, measured every 15 min, was well maintained throughout the duration of the experiment in ischaemic hearts and sham controls (means between 270 and 310 beats min−1) and there were no significant differences between the two groups at any time point (data not shown). QT90 intervals were similar in sham and ischaemic hearts (P=NS) and varied little during 90–240 min (means between 60 and 67 ms). PR intervals in the same time period were similar between ischaemic hearts and sham controls, with mean values between 38 and 44 ms (data not shown; P=NS). Coronary vascular resistance in the non-ischaemic region, calculated as the perfusion pressure per unit coronary flow, decreased 1 min before occlusion from 37±3 to 31±4 mmHg g min ml−1 at 30 min of ischaemia and then increased progressively to 67±14 mmHg g min ml−1 at 240 min (Figure 3; P<0.05). However, a similar pattern was seen in shams, with coronary vascular resistance initially decreasing from 37±4 mmHg g min ml−1 1 min before sham occlusion to 25±3 mmHg g min ml−1 after 30 min of sham occlusion, and then significantly (P<0.05) increasing to 97±21 mmHg g min ml−1 at 240 min (Figure 3; P=NS vs ischaemic hearts).

Figure 3.

Coronary vascular resistance in mmHg g min ml−1 in the non-ischaemic zone of ligated hearts and in whole heart for shams. *Denotes P<0.05 vs ischaemic hearts.

Early (ischaemia-related) arrhythmias

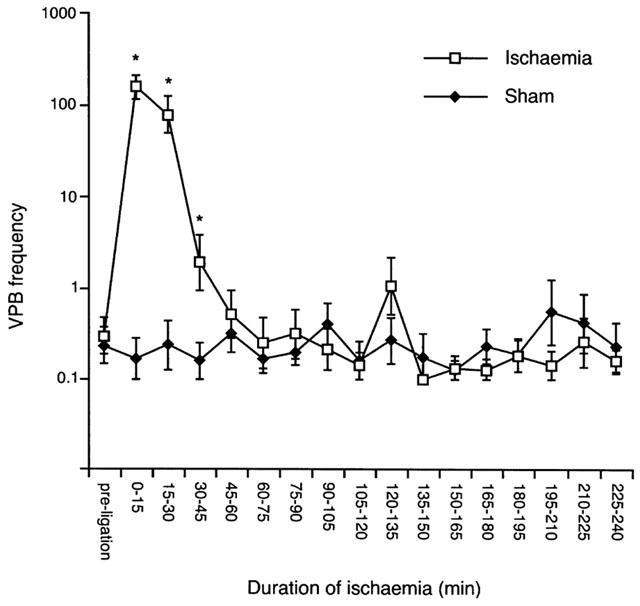

Although not the primary focus of the study at its outset, arrhythmias occurring during the early (0–90 min) period of ischaemia were found to exhibit unexpected characteristics. Surprisingly, only 10% of ischaemic hearts developed early VF (Table 3), which contrasts with an incidence approaching 100% in conscious and pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats in vivo and in buffer-perfused rat hearts (see Curtis, 1998 for review of the relevant literature). Despite the near absence of early VF in blood-perfused hearts, 100% of hearts had ventricular tachycardia in the 0–90 min period (Figure 1; P<0.05 vs shams), and the incidence of salvos and bigeminy was also 100% over the same time period (P<0.05 vs shams). Although VPB incidence (percentage of hearts per group developing VPBs) was actually similar in ischaemic and sham hearts, the VPB frequency (mean number of VPBs per group) was much higher during the first 30 min (Figure 4) in ischaemic hearts with a mean (±1 s.e.mean) of 295 (224–389) VPBs vs a mere 0.25 (0.13–0.49) VPBs 15 min−1 in shams (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Ventricular premature beat (VPB) frequency per 15 min time intervals during 240 min of ischaemia. *Denotes P<0.05 vs shams.

Arrhythmias occurring in sham hearts

Although some sham hearts developed arrhythmias and the cause was unknown, the severity was trivial. None developed VF, and the time course of arrhythmia development did not match that observed in ischaemic hearts. VT was rare, and the total number of episodes in shams was very low compared with ischaemic hearts. Whereas each ischaemic heart developed a mean of 41±6 episodes of VT, with each episode having a mean duration (±1 s.e.mean) of 3.1 (2.6–3.8) s during the first 90 min of ischaemia, in contrast only two episodes of VT were observed in total in the entire sham group during the equivalent period. In the 90–240 min period, ischaemic hearts developed a mean of 2±1 episodes of VT, of mean duration 3.6 (2.5–5.1) s; in contrast, only one sham heart developed VT during the same time period (overall mean frequency 1±1 episodes, of duration 1.8 (1.1–3.0) s).

Support rat blood pressure and heart rate

Support rat mean systolic blood pressure was well maintained in both groups of hearts, with values between 100 and 125 mmHg (data not shown). Systolic pressure rose during the first 120 min of extracorporeal circulation but declined thereafter, in spite of an increase in heart rate from 393±13 to 448±12 beats min−1 (ischaemic group, P=NS vs shams) during the same period.

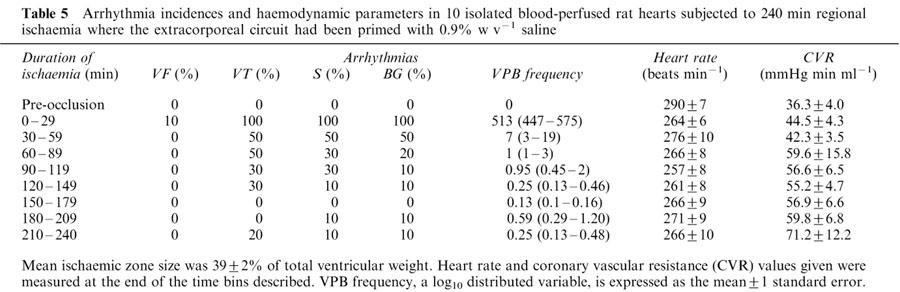

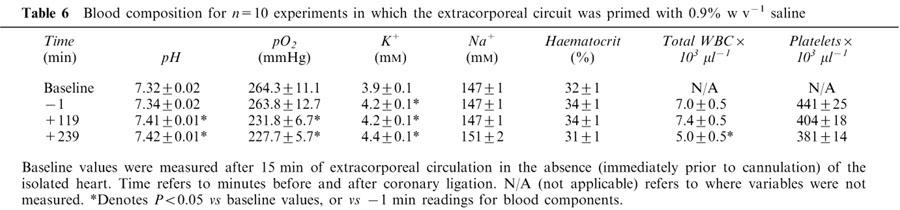

Influence of priming of the extracorporeal circuit with Gelofusine® on ischaemia-induced arrhythmias

The paucity of early ischaemia-related arrhythmias in the above isolated blood-perfused hearts was a surprising observation. To examine whether Gelofusine® may have been partially responsible for the paucity of arrhythmias, a further group of hearts was subjected to left main coronary artery occlusion with the extracorporeal circuit primed with saline (0.9% w v−1) instead of Gelofusine®. The incidences of both early and late VF (Table 3 and 5), and ischaemic zone size (39±2% vs 41±3% of total ventricular weight) were similar with saline and Gelofusine® priming. Heart rate, QT90 and PR intervals (data not shown) and values of coronary vascular resistance (Table 5 and Figure 3) were also similar in the two groups, suggesting that any formation of oedema in the support rats as a result of the use of saline had no effect on the function of the isolated hearts. A decline in circulating platelet and total white blood cell counts was again observed during perfusion (Table 6) but total white blood cell and platelet counts were significantly higher (P<0.05) with saline vs Gelofusine® after 120 and 240 min of ischaemia. With saline, cardiac tissue myeloperoxidase activity increased during ischaemia from 0.02±0.003 (left ventricular tissue from n=10 fresh hearts) to 0.05±0.01 units mg protein−1 (P<0.05) at 240 min. There was a similar increase in MPO activity from 0.02±0.003 (right ventricular tissue from fresh hearts) to 0.04±0.01 units mg protein−1 (P<0.05) in non-ischaemic tissue in the same hearts. These values and the overall pattern of these results were similar to those obtained with Gelofusine®.

Table 5.

Arrhythmia incidences and haemodynamic parameters in 10 isolated blood-perfused rat hearts subjected to 240 min regional ischaemia where the extracorporeal circuit had been primed with 0.9% w v−1 saline

Table 6.

Blood composition for n=10 experiments in which the extracorporeal circuit was primed with 0.9% w v−1 saline

Discussion

Rationale for the use of the blood-perfused heart preparation

The lack of clinically effective drugs to prevent sudden death due to VF may indicate the requirement for more effective and reliable models. Any such model must demonstrate reasonably accurate replication of normal physiological and pathophysiological events and, in addition, function as an effective bioassay (Johnston et al., 1983; Walker et al., 1988; Curtis, 1998). These two requirements are difficult to achieve completely in any single model, so the choice of model will depend on whether an intact milieu or the minimization of independent variables is regarded as paramount.

The isolated blood-perfused heart is a potentially advantageous model for the study of cardiac dysfunction. It is intrinsically a more physiologically relevant model than the isolated buffer-perfused heart, in that the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood is much greater than that of bicarbonate buffer, and delivery of oxygen to the myocardium is more efficient with blood than with an asanguinous solution; much higher partial pressures of oxygen are required to prevent hypoxia in buffer-perfused hearts (Kreutzer & Jue, 1995). Owing to this, and to the differences in the rheological properties of blood vs buffer (i.e., water), coronary flow is at a more physiological level in blood-perfused rat hearts i.e., ∼2–3 ml min g−1 (Hearse et al., 1999) compared with 10–12 ml min g−1 in buffer-perfused hearts (a range that is typical for perfused rabbit and marmoset hearts as well as rat hearts; Rees et al., 1993b). In addition, the blood-perfused heart retains some of the practical advantages of an in vitro preparation (i.e., scope for control of independent variables such as heart rate and coronary flow).

Although the isolated blood-perfused rat heart is an established model for the study of cardiovascular pathophysiology (Galinanes et al., 1993; Hearse et al., 1999; Kolocassides et al., 1995), it has been little utilized for the study of cardiac arrhythmias, and the only published study that is focused on arrhythmias explored a relatively short period of ischaemia (40 min; Lawson et al., 1993). Our long-term goal was to use the isolated blood-perfused rat heart to evaluate the contributions of blood components to initiation of late, infarction-related VF. The present findings suggest that the model is inappropriate for study of late VF, and indeed call in to question the use of the model for the study of other aspects of cardiovascular pathophysiology.

Neutrophil accumulation and the occurrence of late (infarction-related) VF

Only 10% of hearts developed late VF. This contrasts with a 100% incidence in rats in vivo (reviewed by Johnston et al., 1983 and Curtis et al., 1987) and is similar to the 0% incidence in isolated buffer-perfused hearts (Ravingerova et al., 1995) under conditions of equivalent ischaemic zone sizes and K+ content of the blood or buffer perfusing the non-ischaemic tissue. Without further consideration, this may suggest that the presence of blood is insufficient to restore susceptibility to late VF in isolated hearts, and therefore that blood components (such as neutrophils) are not mediators of late VF. However, interpretation of the data is complicated by the fact that total white blood cells and platelets declined in the circulating blood over the duration of the experiment, and values were especially low compared with fresh blood during the 90–240 min period when late phase arrhythmias occur in vivo (Johnston et al., 1983). This loss of blood cells occurred during perfusion of shams as well as in hearts subjected to ischaemia, and thus appears to be a direct consequence of establishing an extracorporeal circulation. An equivalent reduction in circulating total white blood cell and platelet count in blood from rats which had supported an extracorporeal circuit for 5 h, compared with rats anaesthetized for 5 h but which had not supported an extracorporeal circuit, has been reported previously (Lawson, 1993), and this was associated with accumulation of neutrophils in the lungs of the support rat. Likewise, although cardiac neutrophil accumulation was detected in the ischaemic zone during 240 min of perfusion, a similar accumulation was observed in the non-ischaemic tissue. Moreover there was also an equivalent accumulation in sham hearts. Thus cardiac neutrophil accumulation appears not to have occurred as a specific response to ischaemia as it does in vivo (Mullane et al., 1985) but merely to have resulted from the act of perfusion of isolated hearts with blood from a support animal. This is suggestive of a systemic inflammatory response, similar to that which is known to occur during cardiopulmonary bypass operations, in which neutrophils become activated (Butler et al., 1993). Thus, a specific inflammatory response to infarction (i.e. neutrophil recruitment into infarcting tissue) is impossible to distinguish from the systemic non-specific inflammation occurring as a result of passing blood through an artificial extracorporeal circuit and a non-syngeneic heart. This, together with the decline in numbers of circulating blood components during the experiments, makes it impossible to establish the role of neutrophils in mediating late VF using this model.

Circulating blood K+, Gelofusine®, and the occurrence of late VF

In addition to the difficulty in linking neutrophil accumulation to late VF, the possibility that the lack of the latter resulted from factors unrelated to neutrophils requires consideration.

Circulating blood K+ values increased over the course of 240 min (Table 1). However, although moderate systemic hyperkalaemia is antiarrhythmic during myocardial ischaemia and infarction in man (Nordrehaug & von der Lippe, 1983), the concentrations measured in the present study were not sufficiently high to account for the diminished susceptibility to late VF that was observed, according to precise relationship between K+ and VF derived from studies using rats (Curtis et al., 1985a; Saint et al., 1992).

The source of the elevations in blood K+ is unknown, and requires consideration. Similar changes in blood K+ have previously been observed over a 4 h period in surgically prepared anaesthetized rats in vivo (Curtis et al., 1985b). Thus it is possible that acute surgery itself causes elevations in blood K+. Alternatively, another possible source in the present experiments is haemolysis of red blood cells, the result of mechanical disruption by the passage of blood through the peristaltic pump. Haemolysis is a common problem during clinical cardiopulmonary bypass operations in which blood is pumped through an extracorporeal circuit (Lamon et al., 1990). We did not test for haemolysis directly. If it had occurred we would have expected it to be detrimental to the support rat. Although support rat blood pressure did decline during the final 2 h of the experiment at the same time as the elevations in blood K+ were observed, this decline was not marked, and to infer haemolysis from a rise in blood K+ and a decline in blood pressure is perhaps premature since there may well be other reasons for both. A more likely source of K+ may be release from skeletal muscle, which is known to play a role in regulating extracellular K+ levels in vivo (McDonough et al., 2002). Additionally insulin stimulates uptake of K+ into muscles and, since glucose was not added to the extracorporeal circuit, the support rat is essentially fasting and thus insulin levels are likely to decline over time, leading to a loss of blood K+ ‘buffering' by this mechanism. Each of these effects may have contributed to the elevations of blood K+ observed, although as stated, the changes were not sufficient to account for the lack of late VF.

The low incidence of VF was not the result of Gelofusine® priming, since saline priming was associated with similar findings.

Relevance of (and possible mechanism for) the paucity of early (ischaemia-related) VF

The validity of the model is further undermined by the paucity of early, ischaemia-related VF. This was especially surprising considering that rats in vivo (blood present) and isolated buffer-perfused hearts (blood absent) with equivalent ischaemic zone sizes to those in the present experiments typically have early VF incidences of 80–100% (see Curtis, 1998 and Curtis et al., 1987 for reviews). Although, a relatively low incidence of early VF had been reported previously in a blood-perfused rat heart preparation (Lawson et al., 1993), this study had not been corroborated, and so we had anticipated that early VF would be independent of the presence or absence of blood. It should be noted that pentobarbitone, used in the present study to anaesthetize the donor and support rat, does not inhibit early ischaemia-related VF (Mertz & Kaplan, 1982) and so can be excluded as a possible confounding factor. The heparin used in the present study is also unlikely to be responsible for the lack of early (and late) VF, since conscious and anaesthetized rats, to which heparin is administered in order to maintain patent the intra arterial blood pressure lines, consistently exhibit similar biphasic temporal distributions of VF following coronary occlusion (e.g., Clark et al., 1980; Johnston et al., 1983; Curtis et al., 1984, 1985a, 1985b; Curtis & Walker, 1988b), and buffer perfused hearts exhibit early VF despite their having been excised from heparinized animals (e.g., Curtis & Hearse, 1989a, b). Owing to the need for good anticoagulation in the extracorporeal circuit, it was deemed imprudent to attempt to generate a group of nonanticoagulated controls to explore this further and to seek to establish the possibility that heparin is antiarrhythmic uniquely in blood perfused hearts in contrast with its lack of effect in vivo and in buffer perfused hearts.

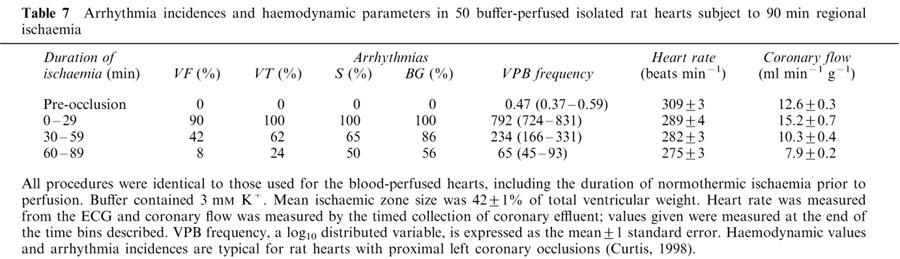

Arrhythmogenesis in an experimental setting is characterized by the incidence, frequency, duration and onset times of the different types of arrhythmias that occur (Johnston et al., 1983; Curtis et al., 1988b). The incidences of early VT, salvos, bigeminy, and VPBs were similar in the blood-perfused hearts to those published for in rats in vivo (Curtis et al., 1987). They were also similar to data from 50 historical isolated buffer-perfused rat hearts from our laboratory (Clements-Jewery et al., 2002). The arrhythmia and haemodynamic data from these historical controls are typical for isolated buffer-perfused hearts subject to proximal left main coronary artery occlusion (e.g., Rees & Curtis, 1993a; 1995), and are presented in Table 7. These data were generated by the same experimental operator as in the present study, and all procedures were identical to those used for the present blood-perfused hearts, including the duration of normothermic ischaemia prior to perfusion. Even though the non-contemporaneous nature of these hearts prevents meaningful statistical analysis with the present data set, it is worthwhile considering the data, because they illustrate that the isolated blood-perfused rat heart exhibits arrhythmia characteristics that appear to differ from those typical for isolated buffer-perfused rat hearts and also those of rats in vivo, and that the pattern of difference is not predictable on the basis of whether blood or buffer were present. Thus, blood-perfused hearts had fewer VPBs during the first 30 min of ischaemia than buffer-perfused hearts. Mean VPB frequency (±1 s.e.mean) was 295 (224–389) and 794 (724–871) in blood- and buffer-perfused hearts respectively. However, arrhythmias developed more swiftly in blood-perfused hearts. Thus the mean (±1 s.e.mean) time to onset of the first ischaemic arrhythmia (like VPB frequency, a log10 Gaussian-distributed variable; Curtis & Hearse, 1989a) was 535 (488–587) s and 622 (608–636) s for blood- and buffer-perfused hearts respectively. Since heart rate (294±6 vs 289±4 beats min−1), ischaemic zone sizes (41±2% vs 42±1%), and values of K+ perfusing the non-ischaemic tissue (4.2 vs 3 mM) during this period were essentially similar in blood and buffer-perfused hearts, respectively, it is difficult to explain these differences. Additionally, as noted earlier, VF occurred in buffer-perfused hearts (as it does in vivo) but not in blood-perfused hearts. Thus, in some respects, but not in others, the overall susceptibility to early phase arrhythmias appears to be lower in the blood-perfused heart compared with the isolated buffer-perfused (and in vivo) hearts.

Table 7.

Arrhythmia incidences and haemodynamic parameters in 50 buffer-perfused isolated rat hearts subject to 90 min regional ischaemia

The best explanation for these observations is that, compared with buffer-perfused hearts and rats in vivo, the balance of endogenous pro- and anti-arrhythmic substances in the milieu (primarily the ischaemic zone) is altered in the blood-perfused heart, causing development of early VF to be disfavoured, yet VPB onset to be hastened, but without affecting the incidence of other arrhythmias during this period. Although the identity of several endogenous pro- and antiarrhythmic substances is known, their relative importance to arrhythmogenesis and the exact nature of their interplay remain to be determined (Curtis et al., 1993; Parratt, 1993).

Anomalous coronary vascular resistance and its possible relevance to arrhythmia susceptibility

An interesting phenomenon observed in the present experiments was the reduction in coronary vascular resistance over the first 30 min of ischaemia, which was followed by a progressive increase during the remainder of the experiment. The same pattern was seen in shams, and so is the product of blood-perfusion rather than ischaemia. This suggests that vasodilatory mediators were released during the first 30 min, with either their wash out, break down or removal, and/or additional release of vasoconstrictor substances after this period. The identity of the vasoactive mediators responsible for each effect is unknown, but release of a wide range of possible candidate substances has been observed during cardiopulmonary bypass operations where blood is passed through an extracorporeal circuit (Downing & Edmunds, 1992). These include bradykinin (Cugno et al., 1999; Nagaoka et al., 1975), histamine (Marath et al., 1987; Withington & Aranda, 1997) prostacyclin (Teoh et al., 1987) and PGE2 (Lajos et al., 1985). Additionally thromboxane A2 may be released from platelets (Teoh et al., 1987). Therefore it is possible that a cocktail of substances is released and that their effects summate to favour vasodilatation during the first 30 min of perfusion, and vasoconstriction thereafter. In addition, it is possible that this balance influences the occurrence of VF since vasodilatation occurred during the period that early VF is normally present in vivo and in buffer-perfused hearts. In this regard, it has been suggested that the vasodilators PGI2, nitric oxide and adenosine are antiarrhythmic during the early phase of arrhythmias (Parratt, 1993). It should be noted that vasodilatation itself cannot explain the near absence of early VF since rat hearts lack sufficient collateral vessels for amelioration of ischaemia by coronary vasodilatation (Maxwell et al., 1987; see Curtis et al., 1987 for explanation). Furthermore, a clear pattern is not implied by the present data since, even though the period of vasodilatation occurred during the period when (early) VF was unexpectedly almost absent, the subsequent period of vasoconstriction was not matched by a commensurate exacerbation of (late) VF.

Conclusion

Although late (infarction-related) VF was absent in blood-perfused hearts, it would be premature to conclude from this that late VF is not mediated by blood components. This is because the decline in circulating white blood cells and platelets, the fact that neutrophil accumulation was similar in ischaemic and sham hearts (indicative of systemic inflammation), and the unexpected paucity of early VF all question the validity of the model, and hence any conclusion about the role of blood components in mediating late VF. The isolated blood-perfused rat heart as used in the present studies thus appears to be an inappropriate model in which to investigate the mediators of late VF. It could also be argued that our study raises serious questions about any studies published previously using the model, since the blood perfused heart clearly does not respond to ischaemia in the same way as the in vivo heart (or indeed the Krebs perfused heart).

Acknowledgments

We thank Fiona Sutherland for her expert technical assistance. H Clements-Jewery is supported by an A.J. Clark Studentship from the British Pharmacological Society.

Abbreviations

- BG

bigeminy

- CVR

coronary vascular resistance

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- HETAB

hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide

- I

ischaemia

- IZ

ischaemic zone

- LV

left ventricle

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NZ

nonischaemic zone

- RV

right ventricle

- S

salvos

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- VPB

Ventricular Premature Beat

- VT

Ventricular Tachycardia

- WBC

white blood cells

References

- ALLAN G., BHATTACHERJEE P., BROOK C.D., READ N.G., PARKE A.J. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative marker of polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation into an experimental myocardial infarct-the effect of ibuprofen on infarct size and polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1985;7:1154–1160. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198511000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER J., ROCKER G.M., WESTABY S. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1993;55:552–559. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)91048-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAST Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:406–412. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908103210629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK C., FOREMAN M.I., KANE K.A., MACDONALD F.M., PARRATT J.R. Coronary artery ligation in anaesthetized rats as a method for the production of experimental dysrhythmias and for the determination of infarct size. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1980;3:357–368. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(80)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMENTS-JEWERY H., HEARSE D.J., CURTIS M.J. Independent contribution of catecholamines to arrhythmogenesis during evolving infarction in the isolated rat heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:807–815. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUGNO M., NUSSBERGER J., BIGLIOLI P., GIOVAGNONI M.G., GARDINALI M., AGOSTONI A. Cardiopulmonary bypass increases plasma bradykinin concentrations. Immunopharmacology. 1999;43:145–147. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J. Characterisation, utilisation and clinical relevance of isolated perfused heart models of ischaemia-induced ventricular fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;39:194–215. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., HEARSE D.J. Ischaemia-induced and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias differ in their sensitivity to potassium: implications for mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of ventricular fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1989a;21:21–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)91490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., HEARSE D.J. Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias are critically dependent upon occluded zone size: relevance to the mechanism of arrhythmogenesis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1989b;21:625–637. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., JOHNSTON K.M., WALKER M.J.A. Arrhythmias and serum potassium during myocardial ischaemia. ICRS Med. Sci. Res. 1985a;13:688–689. [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., MACLEOD B.A., WALKER M.J. Antiarrhythmic actions of verapamil against ischaemic arrhythmias in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1984;83:373–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb16497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., MACLEOD B.A., WALKER M.J. The effects of ablations in the central nervous system on arrhythmias induced by coronary occlusion in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985b;86:663–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb08943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., MACLEOD B.A., WALKER M.J. Models for the study of arrhythmias in myocardial ischaemia and infarction: the use of the rat. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1987;19:399–419. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., PUGSLEY M.K., WALKER M.J. Endogenous chemical mediators of ventricular arrhythmias in ischaemic heart disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:703–719. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., WALKER M.J. The mechanism of action of calcium antagonists on arrhythmias in early myocardial ischaemia: studies with nifedipine and DHM9. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988a;94:1275–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J., WALKER M.J. Quantification of arrhythmias using scoring systems: an examination of seven scores in an in vivo model of regional myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc. Res. 1988b;22:656–665. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.9.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOWNING S.W., EDMUNDS L.H., JR Release of vasoactive substances during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1992;54:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90113-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGLER R.L., DAHLGREN M.D., PETERSON M.A., DOBBS A., SCHMID-SCHONBEIN G.W. Accumulation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes during 3-h experimental myocardial ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:H93–H100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.1.H93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENTMAN M.L., KUKIELKA G.L., BALLANTYNE C.M., SMITH C.W.The role of leukocytes in ischaemic heart disease Immunopharmacology of the Heart 1993UK: Academic Press; 55–74.ed. Curtis, M.J. pp [Google Scholar]

- GALINANES M., BERNOCCHI P., ARGANO V., CARGNONI A., FERRARI R., HEARSE D.J. Dichotomy in the post-ischemic metabolic and functional recovery profiles of isolated blood versus buffer-perfused heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:531–539. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALINANES M., LAWSON C.S., FERRARI R., LIMB G.A., DERIAS N.W., HEARSE D.J. Early and late effects of leukopenic reperfusion on the recovery of cardiac contractile function. Studies in the transplanted and isolated blood-perfused rat heart. Circulation. 1993;88:673–683. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS A.S., BISTENI A., RUSSELL R.A., BRIGHAM J.C., FIRESTONE J.E. Excitatory factors in ventricular tachycardia resulting from myocardial ischemia. Potassium as a major excitant. Science. 1954;119:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.119.3085.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEARSE D.J., FERRARI R., SUTHERLAND F.J. Cardioprotection: intermittent ventricular fibrillation and rapid pacing can induce preconditioning in the blood-perfused rat heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1961–1973. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSE M.J.Re-entry rhythms The Heart and Cardiovascular System 1991New York: Raven press; 2055–2094.ed. Fozzard, H.A. pp [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTON K.M., MACLEOD B.A., WALKER M.J.A. Responses to ligation of a coronary artery in conscious rats and the actions of antiarrhythmics. Canad. J. Phys. Pharm. 1983;61:1340–1353. doi: 10.1139/y83-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLOCASSIDES K.G., GALINANES M., HEARSE D.J. Preconditioning accelerates contracture and ATP depletion in blood-perfused rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:H1415–H1420. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREUTZER U., JUE T. Critical intracellular O2 in myocardium as determined by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance signal of myoglobin. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:H1675–H1681. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAJOS T.Z., VENDITTI J., JR, VENUTO R. Hemodynamic consequences of bronchial flow during cardiopulmonary bypass. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1985;89:934–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMON E.W., BETHARD A., POWELL T.J., JR, BLACKSTONE E.H. Invited letter concerning: hemolysis after cardiopulmonary bypass. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990;99:751–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWSON C.S. Cardiovascular Research, The Rayne Institute, St Thomas' Hospital. London: University of London; 1993. Ischaemic preconditioning, arrhythmias and post-ischaemic contractile dysfunction in rat hearts in vitro and in vivo; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- LAWSON C.S., COLTART D.J., HEARSE D.J. “Dose”-dependency and temporal characteristics of protection by ischaemic preconditioning against ischaemia-induced arrhythmias in rat hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1993;25:1391–1402. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAINLAND D., HERRERA L., SUTCLIFFE M.I. Statistical tables for use with binomial samples–contingency tests, confidence limits and sample size estimates. New York: University College of Medicine Publications; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- MARATH A., MAN W., TAYLOR K.M. Histamine release in paediatric cardiopulmonary bypass–a possible role in the capillary leak syndrome. Agents Actions. 1987;20:299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02074696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAXWELL M.P., HEARSE D.J., YELLON D.M. Species variation in the coronary circulation during regional myocardial ischaemia : a critical determinant of the rate of evolution and extent of myocardial infarction. Cardiovas. Res. 1987;21:737–746. doi: 10.1093/cvr/21.10.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONOUGH A.A., THOMPSON C.B., YOUN J.H. Skeletal muscle regulates extracellular potassium. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2002;282:F967–F974. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERTZ T.E., KAPLAN H.R. Pirmenol hydrochloride (CI-845) and reference antiarrhythmic agents: effects on early ventricular arrhythmias after acute coronary artery ligation in anesthetized rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1982;223:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLANE K.M., KRAEMER R., SMITH B. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1985;14:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAOKA H., YAMADA T., HATANO R., TSUKUURA T., SAKAMOTO T. Clinical significance of bradykinin liberation during cardiopulmonary bypass and its prevention by a kallikrein inhibitor. Jpn. J. Surg. 1975;5:222–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02469765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORDREHAUG J.E., VON DER LIPPE G. Hypokalaemia and ventricular fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction. Br. Heart J. 1983;50:525–529. doi: 10.1136/hrt.50.6.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRATT J. Endogenous myocardial protective (antiarrhythmic) substances. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:693–702. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAVINGEROVA T., TRIBULOVA N., SLEZAK J., CURTIS M.J. Brief, intermediate and prolonged ischemia in the isolated crystalloid perfused rat heart: relationship between susceptibility to arrhythmias and degree of ultrastructural injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1995;27:1937–1951. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES S.A., CURTIS M.J. Pharmacological analysis in rat of the role of the ATPsensitive potassium channel as a potential target for antifibrillatory intervention in acute myocardial ischaemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1995;26:280–288. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199508000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES S.A., CURTIS M.J. Tacrine inhibits ventricular fibrillation induced by ischaemia and reperfusion and widens QT interval in rat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993a;27:453–458. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES S.A., TSUCHIHASHI K., HEARSE D.J., CURTIS M.J. Combined administration of an IK(ATP) activator and Ito blocker increases coronary flow independently of effects on heart rate, QT interval, and ischaemia-induced ventricular fibrillation in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1993b;22:343–349. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIDLEY P.D., YACOUB M.H., CURTIS M.J. A modified model of global ischaemia: application to the study of syncytial mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 1992;26:309–315. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSHMER R.F., WATSON N., HARDING D., BAKER D. Effects of acute coronary occlusion on performance of right and left ventricles in intact unanesthetized dogs. Am. J. Cardiol. 1963;52:41C–46C. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(63)90385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAINT K.M., ABRAHAM S., MACLEOD B.A., MCGOUGH J., YOSHIDA N., WALKER M.J. Ischemic but not reperfusion arrhythmias depend upon serum potassium concentration. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1992;24:701–709. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93384-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHATTOCK M.J., MILLER M.J.I., BRAY D.G., WALDRON C.B. An electronic feed-back circuit to control a peristaltic pump for constant-pressure perfusion of isolated hearts or other organs. J. Physiol. 1997;505:4P. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH P.K., KROHN R.I., HERMANSON G.T., MALLIA A.K., GARTNER F.H., PROVENZANO M.D., FUJIMOTO E.K., GOEKE N.M., OLSON B.J., KLENK D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAIT A.R., LARSON L.O. Resuscitation fluids for the treatment of hemorrhagic shock in dogs: effects on myocardial blood flow and oxygen transport. Crit. Care Med. 1991;19:1561–1565. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199112000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEOH K.H., FREMES S.E., WEISEL R.D., CHRISTAKIS G.T., TEASDALE S.J., MADONIK M.M., IVANOV J., MEE A.V., WONG P.Y. Cardiac release of prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 during coronary revascularization. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1987;93:120–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDO A.L., CAMM A.J., DERUYTER H., FRIEDMAN P.L., MACNEIL D.J., PAULS J.F., PITT B., PRATT C.M., SCHWARTZ P.J., VELTRI E.P. Effect of d-sotalol on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after recent and remote myocardial infarction. The SWORD Investigators. Survival With Oral d-Sotalol. Lancet. 1996;348:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER M.J., CURTIS M.J., HEARSE D.J., CAMPBELL R.W., JANSE M.J., YELLON D.M., COBBE S.M., COKER S.J., HARNESS J.B., HARRON D.W., HIGGINS A.J., JULIAN D.G., LAB M.J., MANNING A.S., NORTHOVER B.J., PARRATT J.R., RIERMERSMA R.A., RIVA E., RUSSELL D.C., SHERIDAN D.J., WINSLOW E., WOODWARD B. The Lambeth Conventions: guidelines for the study of arrhythmias in ischaemia infarction, and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 1988;22:447–455. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.7.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITHINGTON D.E., ARANDA J.V. Histamine release during cardiopulmonary bypass in neonates and infants. Can. J. Anaesth. 1997;44:610–616. doi: 10.1007/BF03015444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]