Abstract

It was investigated how A1-adenosine receptor overexpression alters the effects of carbachol on force of contraction and beating rate in isolated murine atria. Moreover, the influence of pertussis toxin on the inotropic and chronotropic effects of adenosine and carbachol in A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing atria was studied.

Adenosine and carbachol alone exerted negative inotropic and chronotropic effects in electrically driven left atrium or spontaneously beating right atrium of wild-type mice.

These effects were abolished or reversed by pre-treatment of animals with pertussis toxin which can interfere with signal transduction through G-proteins.

Adenosine and carbachol exerted positive inotropic but negative chronotropic effects in atrium overexpressing A1-adenosine receptors from transgenic mice.

The positive inotropic effects of adenosine and carbachol were qualitatively unaltered whereas the negative chronotropic effects were abolished or reversed in atrium overexpressing A1-adenosine receptors after pre-treatment by pertussis toxin.

Qualitatively similar effects for adenosine and carbachol were noted in the presence of isoprenaline, β-adrenoceptor agonist.

It is concluded that overexpression of A1-adenosine receptors also affects the signal transduction of other heptahelical, G-protein coupled receptors like the M-cholinoceptor in the heart. The chronotropic but not the inotropic effects of adenosine and carbachol in transgenic atrium were mediated via pertussis toxin sensitive G-proteins.

Keywords: A1-adenosine receptors, chronotropy, inotropy, M-cholinoceptors, transgenic mice

Introduction

Adenosine (ado) is generated in the heart in response to stimuli such as hypoxia and β-adrenergic stimulation (Bardenheuer et al., 1987; Berne, 1983). Adenosine exerts negative inotropic and chronotropic effects in the heart (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Schrader et al., 1977; Shryock & Belardinelli, 1997), mediated through the A1-adenosine receptor. In addition to A1-adenosine receptors, A2a-, A2b- and A3-adenosine receptors have been detected in the heart (Bokník et al., 1997; Reppert et al., 1991; Salvatore et al., 1993). In the atrium of most mammals (guinea-pig, mouse, man, rat) ado reduces force of contraction and the beating rate when given alone (Böhm et al., 1984; 1985; 1989; Dobson, 1983; Drury & Szent-Györgyi, 1929). Adenosine in the presence of isoprenaline exerts a negative inotropic and chronotropic effect in the atrium of many mammalian species (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). The negative inotropic effect in atrium (and in the ventricle after β-adrenergic stimulation) may involve inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, inhibition of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, activation of protein phosphatases, stimulation of phospholipase C or opening of ion channels (for review: Stein et al., 1998). More specifically, the negative inotropic effect of ado in atrium may be due to activation of voltage dependent KAch-channels, subsequent shortening of action potential duration and therefore less time for influx of Ca2+ (Belardinelli & Isenberg, 1983). Thus, less Ca2+ is in the cell, and therefore less force can be generated by Ca2+ acting on myofilaments.

Transgenic mice have been engineered that overexpress the A1-adenosine receptor (A1-AR) selectively in the heart (Matherne et al., 1997). The transgenic mice were significantly more resistant to the functional and metabolic effects of ischaemia through their overexpressed A1-AR (Matherne et al., 1997; Headrick et al., 1998). In addition, the transgenic overexpression of A1-AR mimicked ischaemic preconditioning in hearts of transgenic animals (Morrison et al., 2000). This cardioprotection is mediated by ATP-sensitive potassium channels (Headrick et al., 2000).

In our previous work we demonstrated that ado can reduce the contractility in isolated left atrial preparations from wild-type mice. Moreover, ado exerted a negative chronotropic effect in right atrial preparations from wild-type mice. In mice that overexpress the A1-AR (in this work called transgenic mice) ado still reduced the beating rate in right atrial preparations. However, ado raised force of contraction (positive inotropic effect) in left atrial preparations from transgenic mice (Neumann et al., 1999). It is conceivable that the reversal of the negative inotropic effect of ado to a positive inotropic effect could reside at the level of ado receptors or in alterations in the post-receptor transduction pathway that is common to the A1-AR and the muscarinic cholinoceptor. Therefore carbachol was studied in parallel to ado in this work.

The direct and indirect effects of ado and carbachol (carb) in the heart are mediated by inhibitory Gi-proteins, which can be covalently modified and blocked by pertussis toxin (Böhm et al., 1986; 1988; Kurachi et al., 1986; Neumann et al., 1994).

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether A1-AR overexpression influences the inotropic and chronotropic effects of M-cholinoceptor stimulation (by carb) in atrium. Furthermore, we wanted to know whether the inotropic and chronotropic effects of ado and carb in atrium are sensitive to pertussis toxin (ptx) pre-treatment of animals that overexpress A1-AR.

Methods

The construct design and initial characterization of the transgenic lines has been previously reported (Matherne et al., 1997). In brief, the rat A1-AR cDNA was expressed under the control of the modified α-myosin heavy-chain (MHC) promoter. The construct was used to generate transgenic mice using standard techniques. In ligand binding experiments Bmax for A1-AR in transgenic animals was about 2600, fmol mg−1 protein, whereas levels in wild-type mice were around 8 fmol mg−1 protein. In the present study, only line 1 of mice which has the highest overexpression of A1-AR was investigated (for comparison see Matherne et al., 1997; Neumann et al., 1999).

Identification of transgenic mice

Genomic DNA was isolated from mice tail biopsies and used for genotyping as described before (Neumann et al., 1999).

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed as described (e.g. Neumann et al., 1994). The A1-AR was quantified using the polyclonal antibody raised against a synthetic polypeptide corresponding to carboxy-terminal domain (amino acids 309–326) of the rat A1-AR (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, U.S.A.). Protein expression of Giα-subunit was measured by means of polyclonal antibody against the carboxy-terminal peptide CKNNLKDCCLF of Giα (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). This antiserum recognizes isoforms Giα1 and Giα2. Both primary antibodies were detected using [125I]-labelled protein A and visualized and quantified in a PhosphorImager™ using ImageQuaNT™ software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.). Western blotting for calsequestrin was performed as described previously (e.g. Bokník et al., 1999).

Pertussis toxin pretreatment

Pertussis toxin (150 μg kg−1 body weight in sodium-phosphate buffer, consisting of 0.1 M of sodium phosphate and 0.5 M of sodium chloride, pH=7.5) was administered intraperitoneally 72 h before isolation of atria. Control animals were treated in the same way with the corresponding amount of solvent alone.

Measurement of contractile function and pacemaker activity

Cardiac preparations were studied from mice of both genders. The body weight ranged from 21.3 to 29.6 g. Right and left atria were dissected from isolated mouse hearts and mounted in an organ bath. Left atrial preparations were continuously electrically stimulated (field stimulation) using a Grass stimulator SD 9, (Quincy, MA, U.S.A.) with each impulse consisting of 1 Hz, with a voltage of 10–15% above threshold and 5 ms duration. Right atrial preparations (auricles) were attached in the same set-up but were not electrically stimulated and allowed to contract spontaneously. These conditions were chosen to ascertain comparability with our earlier work (mouse: Neumann et al., 1999; guinea-pig: e.g. Bokník et al., 1997). The beating rates in isolated atrial preparations from mice are lower than in studies with conscious mice. The bathing solution contained (in mM) NaCl 119.8, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.05, NaH2PO4 0.42, NaHCO3 22.6, Na2EDTA 0.05, ascorbic acid 0.28 and glucose 5.0, continuously gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and maintained at 35°C resulting in a pH of 7.4. Contractions were measured in an isometric set-up. Atria were attached with fine sutures to a hook in the organ bath and a isometric force transducer. Signals were amplified and continuously fed into a chart recorder (Föhr Medical Instruments, Egelsbach, Germany). Adenosine or carbachol were cumulatively applied with 10 min for each concentration. Contraction experiments with carb were performed after addition of ado deaminase (1 μg ml−1 for 30 min) to avoid interference from endogenous ado. It could be argued that the release of endogenous catecholamines might interfere with the results described below. Hence, in some experiments mice were pretreated for 16 h with reserpine (5 mg kg−1). This concentration was adequate because it completely abolished the positive inotropic effect of 10 μM tyramine, an indirect sympathomimetic agent (data not shown).

Ligand binding experiments

Total muscarinic receptor density (Bmax) and equilibration constants (Kd) were determined by quantitating specific binding of the non-selective muscarinic antagonist, [3H]QNB using standard techniques as previously described (Matherne et al., 1997). Briefly, membranes prepared from whole hearts isolated from wild-type control (n=7) and transgenic (n=7) were incubated with adenosine deaminase (5 units ml−1) in membrane buffer with radiolabelled QNB. Membranes were collected onto Whatman GF/C glass fibre filters, which were then washed with ice-cold buffer and a scintillation counter was used to quantitate radioactivity.

Chemicals

The following compounds were used: adenosine, adenosine deaminase, isoprenaline (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), atropine, carbachol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), ZM241385 (Tocris Cookson, Ellisville, MO, U.S.A.). Pertussis toxin was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). The other chemicals were of best analytical grade. Twice distilled water was used throughout.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Significance between groups (PTX versus NaCl- pretreatment, or wild-type versus transgenic) was estimated by unpaired Student's t-test. A P-value smaller than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Left atrial studies

Direct effects of adenosine

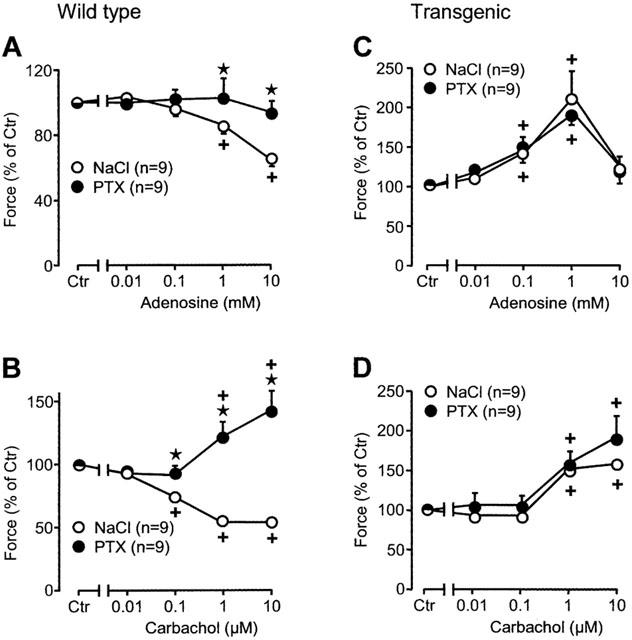

While adenosine concentration dependently reduced force of contraction in wild-type atrium this effect was virtually abolished in PTX pre-treated wild-type animals (Figures 1A, 2A, filled circles). In transgenic atrium, adenosine exhibits a positive inotropic effect. This was first described in our previous study (Neumann et al., 1999) and is recapitulated in Figures 1C and 2C. The positive inotropic effect peaked at 1 mM and is gone at 10 mM adenosine, in agreement with our previous work (Neumann et al., 1999). The positive inotropic effect of ado was blocked by 1 μM DPCPX (Neumann et al., 1999). However 50 nM DPCPX was not able to block the positive inotropic effect of 1 mM adenosine: 1 mM adenosine increased the force of contraction in transgenic atria to 145±12% of pre-drug value. In the presence of 50 nM DPCPX the positive inotropic effect amounted to 147±22% of pre-drug value (not significantly different, n=5, each). Likewise, the positive inotropic effect of 1 mM adenosine was not blocked by 100 nM ZM241385, a potent and selective A2-adenosine receptor antagonist at this concentration (Keddie et al., 1996; Monahan et al., 2000): 1 mM adenosine increased force of contraction in transgenic atria to 174±19% of predrug value, whereas in the presence of ZM241385, 1 mM adenosine increased force of contraction to 155±21% of predrug value. It needs to be elucidated why a high concentration of the A1-AR antagonist is required to block the positive inotropic effect of adenosine in transgenic atria, but a A2-AR mediated effect is unlikely given the lack of effect of ZM241385. Interestingly, the positive inotropic effect is unchanged when PTX-pre-treated atrium is used (Figures 1C, 2C, filled circles). The positive inotropic effect of adenosine was likewise present in atrium from reserpinized transgenic mice (data not shown).

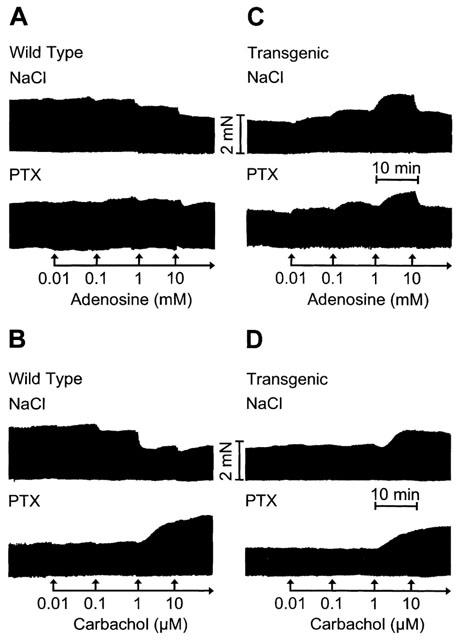

Figure 1.

Original recordings. Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on force of contraction in isolated electrically driven left atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or with corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: time, scale bar indicates 10 min; ordinates: force of contraction, scale bar indicates 2 milli Newton (mN).

Figure 2.

Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on force of contraction in isolated electrically driven left atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or with corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: concentration of adenosine or carbachol, respectively; ordinates: force of contraction in per cent of pre-drug value (Ctr). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of individual left atria. Asterisks denote a significant difference from NaCl-pretreatment (P<0.05, unpaired t-test), crosses indicate a significant difference from pre-drug value (P<0.05, paired t-test).

Direct effects of carbachol

Qualitatively similar observations were made when another G-protein mediated signal was studied: stimulation of the M-cholinoceptor. Carbachol, a M-cholinoceptor agonist, concentration-dependently reduced force of contraction in wild-type atrium (Figures 1B, 2B, open circles). This effect was reversed by PTX pre-treatment of wild-type atrium. Carbachol even exerted a positive inotropic effect after PTX pre-treatment of wild-type atrium (Figures 1B, 2B, filled circles). In transgenic atrium, carbachol exerted a positive inotropic effect, without any PTX pre-treatment (Figures 1D, 2D, open circles). This effect was similar after PTX pre-treatment of transgenic atrium (Figures 1D, 2D, filled circles). The positive inotropic effect of carbachol was likewise present in atrium from re-serpinized transgenic mice (data not shown). The effect of carbachol in transgenic atrium was not affected by 10 μM DPCPX (data not shown).

Indirect effects of adenosine

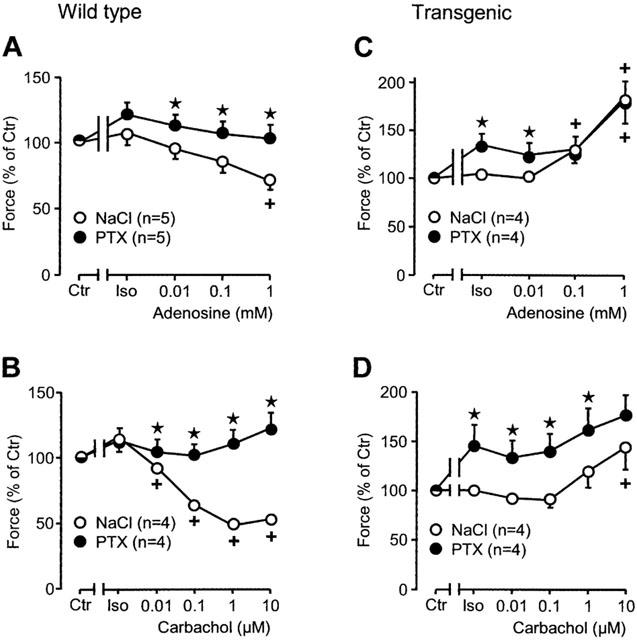

Adenosine does not only exert a direct negative inotropic effect but also attenuates or even reverses the positive inotropic effect of β-adrenergic stimulation (indirect effects). This was systematically studied in Figures 3 and 4. Adenosine reduced force of contraction in the presence of the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline (30 nM). This effect is pronounced in wild-type atrium (Figures 3A and 4A, open circles). The negative inotropic effect of adenosine in the presence of isoprenaline is greatly diminished in PTX pre-treated wild-type atrium (Figures 3A and 4A, filled circles). In transgenic mice, the positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline was hardly detectable. This is in agreement with our earlier report (Neumann et al., 1999, Figure 4). The density of β-adrenoceptors is increased in transgenic hearts versus wild-type hearts (from 32 fmol mg−1 to 90 fmol mg−1, Gauthier et al., 1998). In the presence of isoprenaline, ado exerted a positive inotropic effect (Figures 3C and 4C, open circles). After PTX-treatment, the inotropic effect of isoprenaline was again pronounced (Figures 3C and 4C, closed circle corresponding to Iso on abscissa). Additionally applied ado exerted a positive inotropic effect (Figures 3 and 4C).

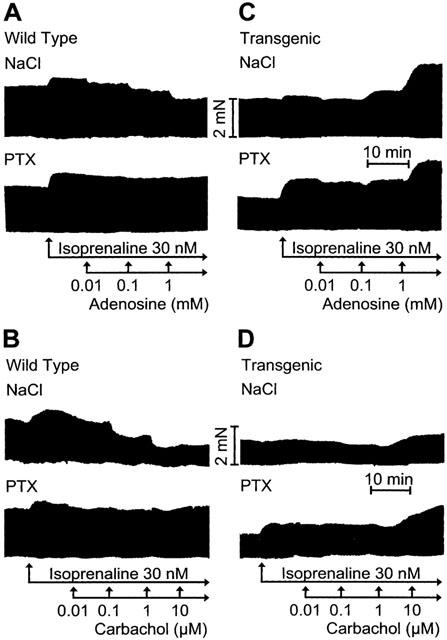

Figure 3.

Original recordings. Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on force of contraction in isolated electrically driven left atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D) in the additional presence of isoprenaline (Iso, 30 nM). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: time, scale bar indicates 10 min; ordinates: force of contraction, scale bar indicates 2 milli Newton (mN).

Figure 4.

Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on force of contraction in isolated electrically driven left atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D) in the additional presence of isoprenaline (Iso, 30 nM). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: concentration of adenosine or carbachol, respectively; ordinates: force of contraction in per cent of pre-drug value (Ctr). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of individual left atria. Asterisks denote a significant difference from NaCl-pretreatment (P<0.05, unpaired t-test), crosses indicate a significant difference from Iso-value (P<0.05, paired t-test).

Indirect effect of carbachol

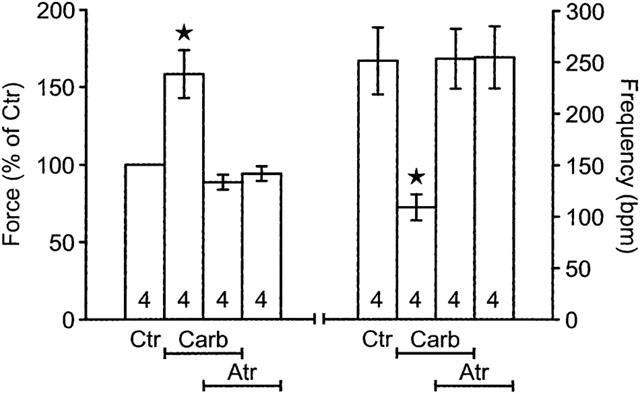

The positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline is abolished and then reversed by increasing concentrations of carb in wild-type atrium (Figures 3B and 4B, open circles). The negative inotropic effect is completely abolished in PTX pre-treated wild-type atrium (Figures 3B and 4B, filled circles). In transgenic atrium the results were different. The positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline is hardly detectable in transgenic atrium. Additionally applied carb even exerts a positive inotropic effect (Figures 3D and 4D, open circles). In PTX pre-treated atrium the effect of isoprenaline is restored and additionally applied carb does slightly increase force of contraction in a concentration dependent way (Figures 3D and 4D). The positive inotropic effects of carbachol are really M-cholinoceptor mediated because they can be blocked by atr (Figure 5). Atropine alone is ineffective on force of contraction (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of carbachol (Carb, 1 μM) alone, or atropine alone (Atr, 1 μM) or both or solvent (Ctr) on force of contraction in isolated electrically driven left atria (LA) and spontaneous beating frequency of right atria (RA) from A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice. Contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. The atria were treated for 10 min with atropine or corresponding amount of solvent and thereafter carbachol was applied to the organ bath. Ordinate left: force of contraction in per cent of pre-drug value; ordinate right: beating frequency in beats per minute (b.p.m.). Numbers in bars indicate the number of individual preparations. Asterisks denote a significant difference from solvent alone (P<0.05).

Right atrial studies

Effect of pertussis toxin

The mean value of the beating rate was 332±18.3 b.p.m. (n=9, range: 199–387 b.p.m.) in wild-type atria and in wild-type atria after PTX treatment 355±12.0 b.p.m. (n=9, range: 333–387 b.p.m., P>0.05). The mean value of the beating rate amounted to 243±16.4 b.p.m. (n=9, range: 188–342 b.p.m.) in transgenic atria, and in transgenic atria after PTX treatment 319±25.4 b.p.m. (n=9, range: 194–424 b.p.m.). Hence, the beating rate was lower in transgenic atria compared to wild-type atria (P<0.05). PTX-pre-treatment increased the beating rate in transgenic atria (P<0.05) to nearly wild-type values.

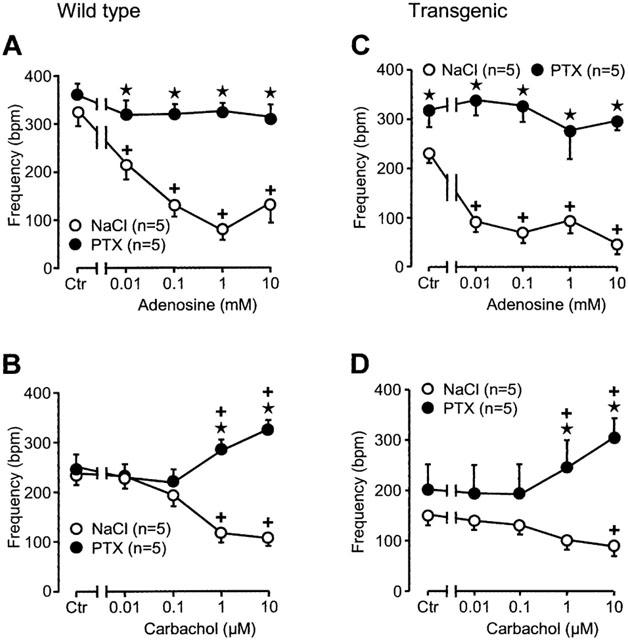

Direct effects of adenosine

We studied the effect of adenosine in transgenic and wild-type right atrium. Atrium was used from sham-treated and PTX-treated animals. Adenosine exerted a concentration dependent negative inotropic effect (Figure 6A, open circles). This effect is blocked by PTX pre-treatment of wild-type animals (Figure 6A, filled circles). In transgenic atrium the basal beating frequency is lower than in wild-type (compare Figure 6C to A). Starting from lower values, ado exerts a negative chronotropic effect. This was noted in our earlier report (Neumann et al., 1999). However, after PTX pre-treatment, the basic beating rate in transgenic atrium is similar to wild-type atrium (filled circles in Figure 6C and open circles in Figure 6A, Ctr). Adenosine was ineffective in transgenic PTX-treated atrium (filled circles in Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on spontaneous beating frequency of isolated right atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: concentration of adenosine or carbachol, respectively; ordinates: beating frequency in beats per minute (b.p.m.). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of individual right atria. Asterisks denote a significant difference from NaCl-pretreatment (P<0.05, unpaired t-test), crosses indicate a significant difference from pre-drug value (P<0.05, paired t-test).

Direct effects of carbachol

Carbachol, like in other species, exerts a negative chronotropic effect in mouse wild-type atrium (Figure 6B). The effect is reversed by PTX pre-treatment. Carbachol concentration-dependently exerts a positive chronotropic effect (Figure 6B). In transgenic atria, carb has likewise a negative chronotropic effect which is blocked by PTX pre-treatment: carb exerts in PTX pre-treated atrium a positive chronotropic effect (Figure 6D). The negative chronotropic effect of carb in atrium of transgenic mice is M-cholinoceptor mediated because it is blocked by atr (Figure 5). Atropine alone did not affect the beating rate (Figure 5).

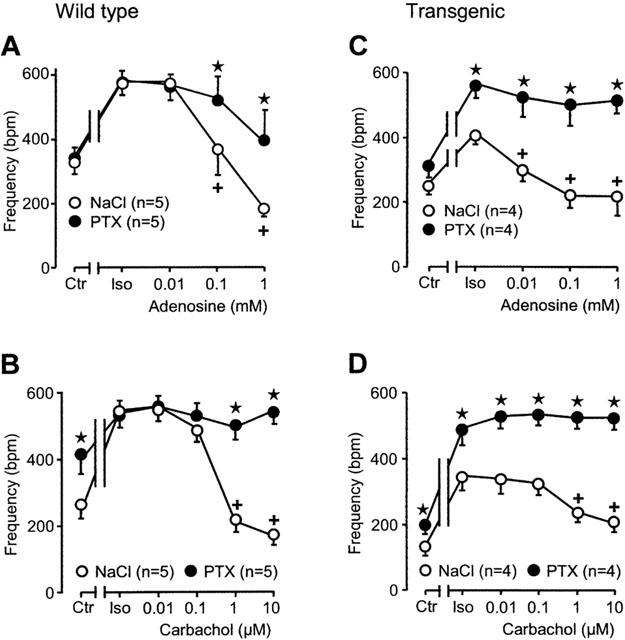

Indirect effects of adenosine

Adenosine exerts a negative chronotropic effect of its own. In addition, it attenuates the positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline. This is seen in Figure 7A (open circles). This effect is not abolished but diminished in PTX pre-treated wild-type atrium (Figure 7A, closed circles). The positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline is smaller in transgenic than in wild-type control atrium (Figure 7A and C, open circles). This small positive chronotropic effect is completely abolished by increasing concentrations of ado (Figure 7C, open circles). After PTX-treatment the negative chronotropic effects of ado are nearly blocked in transgenic right atrium (Figure 7C, closed circles).

Figure 7.

Effects of adenosine (A, C) and carbachol (B, D) on spontaneous beating frequency of right atria from wild-type (A, B) and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice (C, D) in the additional presence of isoprenaline (Iso, 30 nM). Animals were pretreated for 72 h with pertussis toxin (PTX, 150 μg kg−1 body weight) or corresponding amount of solvent alone (NaCl) and contraction experiments were performed as described in Methods. Abscissae: concentration of adenosine or carbachol, respectively; ordinates: beating frequency in beats per minute (b.p.m.). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of individual right atria. Asterisks denote a significant difference from NaCl-pretreatment (P<0.05, unpaired t-test), crosses indicate a significant difference from Iso-value (P<0.05, paired t-test).

Indirect effects of carbachol

Like ado, carb concentration-dependently abolished the positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline in wild-type atrium (Figure 7B, open circles). This negative chronotropic effect of carb is completely gone in PTX pre-treated atrium (Figure 7B, closed circles). In transgenic atrium, carb attenuated the positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline (Figure 7D, open circles). This effect of carb was completely blocked in atrium of PTX pre-treated transgenic mice (Figure 7D, closed circles).

Biochemistry

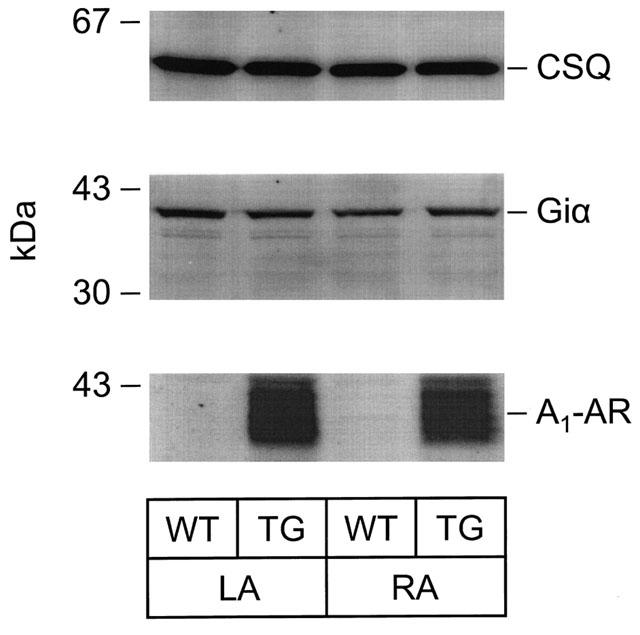

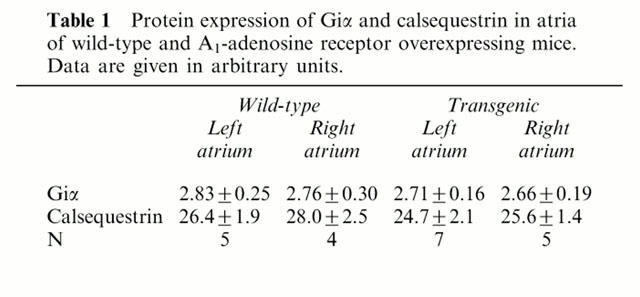

In order to ascertain the expression of PTX-sensitive G-proteins, Western blots from atrial preparations were performed. We detected around 40 kDa a signal which corresponds to Giα proteins. These proteins were ADP ribosylated in the subsequent experiments by pre-treatment of mice with pertussis toxin (HPTX). For comparison we also measured the expression of calsequestrin, a Ca2+-binding protein in the junctional sacroplasmic reticulum. Calsequestrin is very constantly expressed in the heart. Its expression is not altered in hypertrophy or heart failure in many animal models and in human cardiac samples (Hasenfuss, 1998). Indeed the expression of calsequestrin was likewise unchanged in the present study (Figure 8, upper panel, see Table 1). In the same protein samples the expression of Giα was also unchanged between transgenic and wild-type atrium (Figure 8, middle panel, Table 1). In contrast, the transgenic rat A1-AR could be detected with a polyclonal antibody in the very same preparations (Figure 8, lower panel). The density of muscarinic receptors was assessed with QNB binding (see Methods). The density amounted to 120.8±12.8 fmol mg−1 (n=7) in wild-type and 125.5±4.8 fmol mg−1 (n=7) in transgenic mice, respectively which was not significantly different. Similarly, there was no significant difference in QNB-binding affinity between wild-type and transgenic hearts (0.07±0.01 nmol l−1 in wild-type vs 0.06±0.01 nmol l−1 in transgenic).

Figure 8.

Autoradiogram of nitrocellulose strips. Protein expression of A1-adenosine receptor (A1-AR), α-subunit of G-inhibitory protein (Giα) and calsequestrin (CSQ) in atria of wild-type (WT) and A1-adenosine overexpressing mice (TG). Immunological quantification using polyclonal antibodies and [125I]-labelled protein A was performed as described in Methods. Radioactive bands were visualized and quantified using a PhosphorImager™. On the left, molecular weight markers are indicated. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Table 1.

Protein expression of Giα and calsequestrin in atria of wild-type and A1-adenosine receptor overexpressing mice. Data are given in arbitrary units

Discussion

The results of this report focus on the functional characterization of inotropic and chronotropic effects in atrium overexpressing A1-AR. We obtained two main new findings. Firstly, carb exerts a paradoxical positive inotropic effect in transgenic atrium. Secondly, the effects of ado and carb on frequency but not force were altered by PTX pre-treatment in transgenic atrium.

Effects of carbachol in the absence of PTX

We had previously functionally characterized the effects of ado on force and frequency in atrium overexpressing A1-AR (Neumann et al., 1999). Here, we studied for comparison in addition M-cholinoceptor activation by carb. Like ado, carb does attenuate the positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline in wild-type atria. This has been observed in many species (Böhm et al., 1984; 1985; Brückner et al., 1985; Dobson, 1983; for review: Löffelholz & Pappano, 1985).

The negative inotropic effect of carb in wild-type atrium is reversed to a positive inotropic effect in A1-AR overexpressing atrium. The negative inotropic and negative chronotropic effects of carb are mediated by sub-types of M-cholinoceptors. The mRNA for M1-, M2-, M3-, M4- and M5-cholinoceptors were identified in the heart (rat: Krejci & Tucek, 2002; human: Wang et al., 2001). However, the M2-cholinoceptors accounted for more than 90% of total muscarinic mRNA (rat: Krejci & Tucek, 2002). The M1-cholinoceptor is not expressed in the mouse heart (Hardouin et al., 2002). M3-cholinoceptor deficient mice revealed that M3-cholinoceptors do not play a role in carb-induced atrial rate reduction (Stengel et al., 2002). While a contribution of M4- and M5-cholinoceptors is possible, it is likely that the effects of carb in the mouse heart are M2-cholinoceptor mediated. The density of muscarinic receptors was not different in whole heart (atria and ventricles) preparations from wild-type and transgenic mice. Due to the small atrial size no data on the expression of muscarinic receptors in the atrium alone of wild-type and transgenic mice is available, but we assume that atrial expression is comparable to ventricular expression. Further experimentation will be required to resolve this issue. It is conceivable that in transgenic atrium carb might increase phospholipase C activity and therefore IP3-content. This would increase the Ca2+-content in the cells and increase force of contraction. In addition, it is possible that the effect of carb could be explained as an adaptation of cardiac cells to tonic inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity (Thomas & Hoffman, 1987). The exact mechanism needs to be elucidated. It can be doubted whether the results shown for carb in transgenic atrium are of physiological relevance because we used high concentrations (up to 10 μM carb). However, even the well-known negative inotropic effect required 1 μM carb (Figure 6B). At this concentration the positive inotropic effect of carb in transgenic atrium was already present.

Effects of PTX on force

Based on the biochemical studies we wanted to characterize the contraction pathway in more detail using pertussis toxin (PTX). The dose of PTX was based on the literature (e.g. Xiao et al., 1999) and is lower than the dose of PTX which we used in previous work on guinea-pig atrium and ventricle (Böhm et al., 1986; Neumann et al., 1994). Functionally, the dose of PTX used here was sufficient to block the negative inotropic effect of adenosine and carbachol. Both effects are PTX-sensitive (Kurachi et al., 1986). For M-cholinoceptors, similar signal transduction mechanisms like discussed above for A1-AR might be possible (Neumann et al., 1993). One major biochemical difference in the signal transduction between A1-adenosine and M-cholinoceptors is that M-cholinoceptor stimulation but not A1-receptor stimulation increases the cGMP content of the cardiac cell (Löffelholz & Pappano, 1985; Neumann et al., 1993). Hence, additional effects of cGMP and cGMP-dependent kinase may contribute to the effects of carb in the transgenic atrium.

We noted before that the positive inotropic effect of isoprenaline was blunted in transgenic atrium (Neumann et al., 1999; Figure 4). A new finding here is that PTX pre-treatment restores the inotropic response to 30 nM isoprenaline in transgenic atrium to that in wild-type atrium. This argues for a tonic inhibition of β-adrenoceptor pathway in transgenic atrium by stimulation of the function of Gi-proteins (their amount was not changed, see above). Functionally, the positive inotropic effect is not mediated by PTX-sensitive proteins as PTX did not block the positive inotropic effect of ado or carb in the transgenic atrium.

Effects of PTX on rate of beating

The basal beating rate is lower in right atrium of A1-AR overexpressing mice (intact mouse: Matherne et al., 1997; isolated atrium: Neumann et al., 1999). This chronotropic effect must also involve a PTX-sensitive G-protein because PTX pre-treatment increased the frequency to wild-type values. This effect must be due to altered function not due to altered protein expression because the level of Giα on immunoblots from right atrium was unchanged between wild-type and transgenic atrium (Figure 8, Table 1).

The negative chronotropic effects of ado and carb (alone and in the presence of isoprenaline) in transgenic mice are clearly mediated by PTX-sensitive G-proteins. It is possible that the overexpression of A1-AR is lower in pacemaker cells of right atrial preparations than in left atrial preparations. However, this issue is difficult to decide by experimentation due to sensitivity problems in small samples (pacemaker area). The negative chronotropic effects are abolished (ado) or reversed (carb) by PTX pre-treatment. Hence, the effect of ado (or carb) on cAMP generation and action or protein phosphorylation in the sinus node of A1-AR overexpressing atrium involves PTX sensitive G-proteins. The mechanism for the positive chronotropic effect of carb is unclear. An attractive hypothesis is the generation of IP3 or cGMP. As both ado and carb generate IP3 under certain conditions, an involvement of cGMP is a plausible hypothesis to explain this functional difference. Indeed cGMP can directly bind to the pacemaker channel and can increase the pacemaker current (If) in the same way as cAMP but with a lower potency (Musialek et al., 1997; Yoo et al., 1998).

The negative chronotropic effect of ado may involve protein phosphorylation or direct action of cAMP or indirect actin of cGMP or direct action of cGMP on hyperpolarization activated cation channels (Ludwig et al., 1999; Moosmang et al., 2001). β-adrenoceptor stimulation would increase cAMP content and/or protein phosphorylation in cells of the sinus node. This would increase the firing rate of pacemaker cells. Reduction of cAMP (by reduced formation or by increased degradation by cGMP stimulated phosphodiesterases) or reduction of protein phosphorylation by decreased action of cAMP-dependent protein kinase or increase activity of protein phosphatases would reduce the firing rate. The reduction of the current through If might be the mechanism of action of ado in the sinus node (rabbit: Zaza et al., 1996; human: Porciatti et al., 1997). Carbachol can increase the synthetic production of NO and NO leads to enhanced cGMP production. The production of cGMP may have dual effects. The cGMP could stimulate phosphodiesterase activities and this would reduce cAMP and therefore the heart rate. Higher concentrations of cGMP could act as direct stimulators of the If and this would increase the heart rate (Musialek et al., 1997; Yoo et al., 1998). G-proteins must be involved because the negative chronotropic effect of adenosine is PTX-sensitive. The cAMP production or other targets (phosphorylation) might be altered by α- or β/γ-subunits of PTX-sensitive G-proteins.

In summary, we provide evidence that the negative chronotropic but not the positive inotropic effects of ado and carb in atrium overexpressing A1-AR are mediated by PTX-sensitive G-proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ne 393/24-1), and NIH RO1 HL59419. Dr Matherne was a recipient of an AHA established investigator grant.

Abbreviations

- Ado

adenosine

- A1-AR

A1-adenosine receptors

- atr

atropine

- carb

carbachol

- ptx

pertussis toxin

References

- BARDENHEUER H., WHELTON B., SPARKS H.V., JR Adenosine release by the isolated guinea pig heart in response to isoproterenol, acetylcholine, and acidosis: The minimal role of vascular endothelium. Circ. Res. 1987;61:594–600. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELARDINELLI L., ISENBERG G. Isolated atrial myocytes: adenosine and acetylcholine increase in potassium conductance. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;244:H291–H294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.5.H734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNE R.M. Cardiac nucleotides in hypoxia: Possible role in regulation of coronary blood flow. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;204:317–322. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., BRÜCKNER R., HACKBARTH I., HAUBITZ B., LINHART R., MEYER W., SCHMIDT B., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H. Adenosine inhibition of catecholamine-induced increase in force of contraction in guinea-pig atrial and ventricular heart preparations. Evidence against a cyclic AMP- and cyclic GMP-dependent effect. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1984;230:483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., BRÜCKNER R., NEUMANN J., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H., STARBATTY J. Role of guanine nucleotide-binding protein in the regulation by adenosine of cardiac potassium conductance and force of contraction. Evaluation with pertussis toxin. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1986;332:403–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00500095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., BRÜCKNER R., SCHÄFER H., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H. Inhibition of the effects of adenosine on force of contraction and the slow calcium inward current by pertussis toxin is associated with myocardial lesions. Cardiovasc. Res. 1988;22:87–94. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., MEYER W., MÜGGE A., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H. Functional evidence for the existence of adenosine receptors in the human heart. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;116:323–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., PIESKE M., UNGERER M., ERDMANN E. Characterization of A1-adenosine receptors in human atrial and ventricular myocardium from diseased human hearts. Circ. Res. 1989;65:1201–1211. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOKNÍK P., NEUMANN J., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H., WENZLAFF H. Characterization of biochemical effects of CGS 21680C, an A2-adenosine receptor agonist, in the mammalian ventricle. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;30:750–758. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199712000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOKNÍK P., UNKEL C., KLEIN-WIELE O., KNAPP J., LINCK B., LUESS H., MÜLLER F.U., SCHMITZ W., VAHLENSIECK U., ZIMMERMANN N., JONES L.R., NEUMANN J. Regional expression of phospholamban in the human heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;42:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRÜCKNER R., FENNER A., MEYER W., NOBIS T.M., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H. Cardiac effects of adenosine and adenosine analogs in guinea-pig atrial and ventricular preparations. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;234:766–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOBSON J.G., JR Adenosine reduces catecholamine contractile responses in oxygenated and hypoxic atria. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;245 Suppl.:H468–H474. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.3.H468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRURY A.N., SZENT-GYÖRGYI A. The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 1929;68:213–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1929.sp002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUTHIER N.S., MORRISON R.R., BYFORD A.M., JONES R., HEADRICK J.P., MATHERNE G.P. Functional genomics of transgenic overexpression of A1 adenosine receptors in the heart. Drug Development Research. 1998;45:402–409. [Google Scholar]

- HARDOUIN S.N., RICHMOND K.N., ZIMMERMAN A., HAMILTON S.E., FEIGL E.O., NATHANSON N.M. Altered cardiovascular responses in mice lacking the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;301:129–137. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASENFUSS G. Alterations of calcium-regulatory proteins in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;37:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEADRICK J.P., GAUTHIER N.S., BERR S.S., MATHERNE G.P. Transgenic A1 adenosine receptor overexpression improves myocardial energy state during ischemia reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:1059–1064. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEADRICK J.P., GAUTHIER N.S., MORRISON R., MATHERNE G.P. Cardioprotection by KATP channels in wild-type and hearts overexpressing A1-adenosine receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279 Suppl:H1690–H1697. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEDDIE J.R., POUCHER S.M., SHAW G.R., BROOKS R., COLLIS M.G. In vivo characterisation of ZM 241385, a selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;301:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREJCI A., TUCEK S. Quantitation of mRNAs for M1 to M5 subtypes of muscarinic receptors in rat heart and brain cortex. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61:1267–1272. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURACHI Y., NAKAJIMA T., SUGIMOTO T. On the mechanism of activation of muscarinic potassium channels by adenosine in isolated atrial cells. Pflügers Arch. 1986;407:264–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00585301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÖFFELHOLZ K., PAPPANO A.J. The parasympathetic neuroeffector junction of the heart. Pharmacol. Rev. 1985;37:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUDWIG A., ZONG X., STIEBER J., HULLIN R., HOFMANN F., BIEL M. Two pacemaker channels from human heart with profoundly different activation kinetics. EMBO J. 1999;18:2323–2329. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHERNE G.P., LINDEN J., BYFORD A.M., GAUTHIER N.S., HEADRICK J.P. Transgenic A1 adenosine receptor overexpression increases myocardial resistance to ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6541–6546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONAHAN T.S., SAWMILLER D.R., FENTON R.A., DOBSON J.G., JR Adenosine A2a-receptor activation increases contractility in isolated perfused hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279 Suppl.:H1472–H1481. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOOSMANG S., STIEBER J., ZONG X., BIEL M., HOFMANN F., LUDWIG A. Cellular expression and functional characterization of four hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels in cardiac and neuronal tissues. Eur. J. Biol. 2001;268:1646–1652. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRISON R.R., JONES R., BYFORD A.M., STELL A.R., PEART J., HEADRICK J.P., MATHERNE G.P. Transgenic overexpression of cardiac A1 adenosine receptors mimics ischemic preconditioning. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279 Suppl.:H1071–H1078. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUSIALEK P., LEI M., BROWN H.F., PATERSON D.J., CASADEI B. Nitric oxide can increase heart rate by stimulating the hyperpolarization-activated inward current, I(f) Circ. Res. 1997;81:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUMANN J., BOKNIK P., BODOR G.S., JONES L.R., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H. Effects of adenosine receptor and muscarinic cholinergic receptor agonists on cardiac protein phosphorylation. Influence of pertussis toxin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;269:1310–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUMANN J., GUPTA R.C., WATANABE A.M.Biochemical basis of cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic interaction Vagal control of the heart: Experimental basis and clinical implications 1993New York: Futura Publishing Co. Inc; 157–166.ed. Levy, M.N. & Schwartz, P.J. [Google Scholar]

- NEUMANN J., VAHLENSIECK U., BOKNIK P., LINCK B., LÜSS H., MÜLLER F.U., MATHERNE G.P., SCHMITZ W. Functional studies in atrium overexpressing A1-adenosine receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:1623–1629. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORCIATTI F., PELZMANN B., CERBAI E., SCHAFFER P., PINO R., BERNHART E., KOIDL B., MUGELLI A. The pacemaker current I(f) in single human atrial myocytes and the effect of beta-adrenoceptor and A1-adenosine receptor stimulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:963–969. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:415–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REPPERT S.M., WEAVER D.R., STEHLE J.H., RIVKEES S.A. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rat A1-adenosine receptor that is widely expressed in brain and spinal cord. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:1037–1048. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALVATORE C.A., JACOBSON M.A., TAYLOR H.E., LINDEN J., JOHNSON R.G. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRADER J., BAUMANN G., GERLACH E. Adenosine as inhibitor of myocardial effects of catecholamines. Pflügers Arch. 1977;372:29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00582203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHRYOCK J.C., BELARDINELLI L. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular system: biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997;79:2–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN B., KIEHN J., NEUMANN J.Regulation of adenosine receptor subtypes and cardiac dysfunction in human heart failure Cardiovascular Biology of Purines 1998Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 65–92.ed. Burnstock, G., Dobson Jr, J.G., Liang, B.T. & Linden, J. [Google Scholar]

- STENGEL P.W., YAMADA M., WESS J., COHEN M.L. M3-receptor knockout mice: muscarinic receptor function in atria, stomach fundus, urinary bladder, and trachea. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;282 Suppl.:R1443–R1449. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00486.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS J.M., HOFFMAN B.B. Adenylate cyclase supersensitivity: A general means of cellular adaptation to inhibitory agonists. TIPS. 1987;8:308–311. [Google Scholar]

- WANG H., HAN H., ZHANG L., SHI H., SCHRAM G., NATTEL S., WANG Z. Expression of multiple subtypes of muscarinic receptors and cellular distribution in the human heart. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:1029–1036. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIAO R.P., AVDONIN P., ZHOU Y.Y., CHENG H., AKHTER S.A., ESCHENHAGEN T., LEFKOWITZ R.J., KOCH W.J., LAKATTA E.G. Coupling of β2-adrenoceptor to Gi proteins and its physiological relevance in murine cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 1999;84:43–52. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOO S., LEE S.H., CHOI B.H., YEOM J.B., HO W.K., EARM Y.E. Dual effect of nitric oxide on the hyperpolarization-activated inward current (If) in sino-atrial node cells of the rabbit. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:2729–2738. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAZA A., ROCCHETTI M., DIFRANCESCO D. Modulation of the hyperpolarization-activated current (If) by adenosine in rabbit sinoatrial myocytes. Circulation. 1996;94:734–741. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]