Abstract

We investigated the inhibition of hEAG1 potassium channels, expressed in mammalian cells and Xenopus oocytes, by several blockers that have previously been reported to be blockers of hERG1 channels.

In the whole-cell mode of mammalian cells, LY97241 was shown to be a potent inhibitor of both hEAG1 and hERG1 channels (IC50 of 4.9 and 2.2 nM, respectively). Clofilium, E4031, and haloperidol apparently inhibited hEAG1 channels with lower potency than hERG1 channels, but they cannot be considered hERG1-specific.

The block of hEAG1 channels by LY97241 and clofilium was time-, use-, and voltage-dependent, best explained by an open-channel block mechanism.

Both drugs apparently bind from the intracellular side of the membrane at (a) specific site(s) within the central cavity of the channel pore. They can be trapped by closure of the activation gate.

In inside-out patches from Xenopus oocytes, hEAG1 block by clofilium was stronger than by LY97241 (IC50 of 0.8 and 1.9 nM, respectively). In addition, hEAG1 block by clofilium was much faster than by LY97241 although there was no difference in the voltage dependence of the on-rate of block.

Physico-chemical differences of clofilium and the weak base LY97241 determine the access of the drugs to the binding site and thereby the influence of the recording mode on the apparent block potencies. This phenomenon must be considered when assessing the inhibitory action of drugs on ion channels.

Keywords: EAG, ERG, potassium channel, clofilium, LY97241, E4031, haloperidol

Introduction

hEAG1 channels are voltage dependent potassium channels belonging to the EAG family, that consists of the EAG (ether à go-go, ERG (eag related gene) and ELK (eag like potassium channel) subfamilies (Bauer & Schwarz, 2001). Two members of the EAG subfamily from humans, heag1 and heag2, have been cloned and characterized (Occhiodoro et al., 1998; Schönherr et al., 2002).

A typical feature of EAG channels is their prepulse dependence of the activation kinetics, i.e. activation is slowed down by hyperpolarizing prepulses, especially under physiological concentrations of extracellular Mg2+ (Ludwig et al., 1994; Terlau et al., 1996). On the basis of their prepulse dependence, EAG currents could be identified in several human cancer cell lines (Meyer & Heinemann, 1998; Meyer et al., 1999; Ouadid-Ahidouch et al., 2001). Recent publications (Pardo et al., 1999; Gavrilova-Ruch et al., 2002) suggest that the hyperpolarizing activity of EAG channels, which previously has been shown to be necessary for myoblast fusion (Occhiodoro et al., 1998), promotes cell-cycle progression.

In Drosophila melanogaster, mutations in the eag gene cause repetitive firing and increased transmitter release in motor neurons (Ganetzky & Wu, 1983). In contrast, little is known about the physiological function of EAG channels in human neuronal tissues. A modulation of excitability via control of the resting potential seems likely, but so far no EAG current correlate has been found in native neuronal preparations. The strong expression of various channel types in neuronal tissues hampers the identification of EAG-mediated currents by means of their activation kinetics. Specific inhibitors of hEAG channels would be helpful tools for the identification of native EAG currents. So far, however, only blockers with weak specificity, like quinidine, that inhibit EAG channels in the micromolar concentration range (Schönherr et al., 2002), have been identified.

For the related hERG channel that underlies the cardiac repolarization current IKr, inhibitors like methanesulphonanilides are available (Tseng, 2001). Besides the specific block by these and other class-III anti-arrhythmics, hERG channels are inhibited by a wide range of therapeutic agents (Vandenberg et al., 2001), which may lead to lethal ventricular arrhythmia. Because of such side-effects, the mechanism of inhibition of the hERG channel has been studied in detail, indicating that both the fast inactivation and the structure of the channel pore are the major determinants (Tseng, 2001; Vandenberg et al., 2001). An important feature is the larger volume of the inner vestibule of the channel pore due to the lack of a PxP motif that is believed to induce a sharp bend in the S6 helices of Kv channels (del Camino et al., 2000). Another characteristic is the presence of aromatic residues in the S6 segment that allow specific interactions with aromatic moieties of several drugs by π electron stacking (Mitcheson et al., 2000a).

In contrast to hERG, hEAG channels do not inactivate, but the pore structure of both channels is similar. Hence, we speculated that some substances, which inhibit hERG channels, might also block hEAG channels with high potency.

In this study we tested the quaternary ammonium derivative clofilium (Steinberg & Molloy, 1979) and its tertiary analogue LY97241 (Suessbrich et al., 1997b), the methanesulphonanilide E4031 (Herzberg et al., 1998) as well as the antipsychotic drug haloperidol (Suessbrich et al., 1997a) on their ability to inhibit hEAG1 and hERG1 channels. In addition, to gain insight into the block mechanism and to assess the validity of the assay system, we compared the block of hEAG1 channels measured in the whole-cell configuration from mammalian cells with the inside-out configuration of membrane patches from Xenopus oocytes.

Methods

Expression of hEAG1 and hERG1 in mammalian cell lines

hERG1 channels were stably expressed in HEK 293 cells (Schönherr et al., 1999), hEAG1 channels in CHO-K1 cells (Gavrilova-Ruch et al., 2002). CHO-K1 cells were routinely grown in 250-ml culture flasks (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) in Nutrient Mix F-12 medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS). HEK 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's (Invitrogen)/F-12 medium (ratio 1: 1) supplemented with 10% FCS. Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and subcultured every 3–4 days. All cells were used within passage numbers 3 to 25. hEAG1 channels were also transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells using the Polyfect transfection kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For electrophysiological recordings cells were plated on 35-mm petri-dishes.

Expression of hEAG1 in Xenopus oocytes

For heterologous expression in Xenopus occytes capped mRNA of hEAG1 subcloned in pGEM-HE (Schönherr et al., 2000) and hERG1 subcloned in pSP64 (Mark Keating, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, U.S.A.) was synthesized in vitro with T7 and SP6 RNA polymerase, respectively (mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit, Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.). Oocyte preparation and injection of RNA was performed as described previously (Schönherr & Heinemann, 1996).

Electrophysiological recordings

As patch-clamp amplifier we used an EPC9 (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). For recordings from mammalian cells the patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass (Kimble Glass, Vineland, NJ, U.S.A.) with resistances of 1–2 MΩ. Unless stated otherwise, the pipettes were filled with (in mM): KCl 130, MgCl2 2, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, pH 7.4 (adjusted with KOH). The standard bath solution contained (in mM): NaCl 145, KCl 5, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 2, HEPES 10, pH 7.4 (with NaOH). Currents were measured in the whole-cell configuration with access resistances below 3 MΩ. Series resistance compensation was applied to 80–90%. For recording from excised patches from CHO cells the following solutions were used (in mM): extracellular: NaAsp 145, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, HEPES 10, pH 7.4 (with NaOH); intracellular: KAsp 120, KCl 10, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, pH 7.4 (with KOH).

For macro-patch recordings from Xenopus oocytes in the inside-out and outside-out configuration the patch pipettes were formed from aluminum silicate glass (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany) with tip resistances of 1–2 MΩ. Standard external solution was composed of (in mM): NaAsp 103.6, KCl 11.4, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 10, pH 7.2 (NaOH). Standard internal solution contained (in mM): KAsp 110, KCl 15, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, pH 7.2 (KOH). Pipette tips for both types of experiments were fire-polished immediately before use. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–23°C).

All chemicals used were of high grade, obtained from Sigma (Taufkirchen, Germany). E4031 was obtained from Waco chemicals (Neuss, Germany). LY97241 was kindly provided by Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.A.).

Potassium channel blockers were dissolved in the bath solution immediately before the experiments. They were applied to the cells under consideration with an application pipette ensuring complete immersion of the cells/patches in the respective solution. Blocker effects were allowed to equilibrate, monitored by repetitive depolarizations. Current block was analysed by plotting the remaining current, normalized to the control current before blocker application as a function of the blocker concentration. IC50 values were obtained by fitting a Hill equation to these data:

with the half-maximum inhibition concentration IC50 and the Hill coefficient nH. To quantify the time course of onset of block an exponential function:

was employed. I0 and I(∞) are the current amplitudes before blocker application (at time t0) and after block equilibration, respectively. τb is the time constant of onset of block.

Data acquisition and analysis were carried out with Pulse+PulseFit (HEKA) and IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, U.S.A.) software. All data are presented as mean±s.e.mean (n) with n being the number of independent experiments. Statistical differences between two groups of data were performed using two-sided Student's t-test indicated as P<0.05 (*) or P<0.005 (**).

Results

Inhibition of hEAG1 and hERG1 channels by LY97241

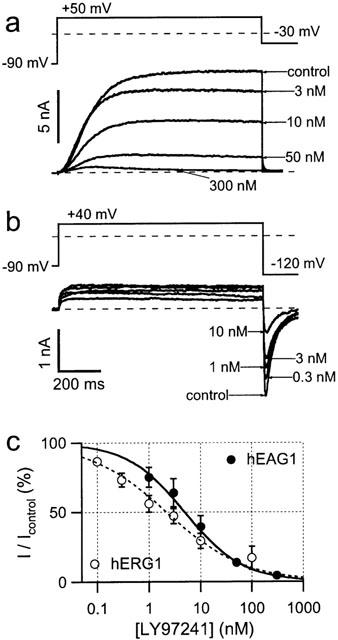

hEAG1 channels mediate voltage dependent, non-inactivating outward K+ currents with a typical prepulse and Mg2+ dependent activation time course. To assay the inhibitory action of various drugs, repetitive 1 s depolarizations to +50 mV were applied and currents were measured at the end of the test pulses (Figure 1a). hERG1 channels also mediate slowly activating K+ currents, but a rapid inactivation prevents correct determination of blocking effects by measuring outward currents. Upon repolarization, the rapid recovery from inactivation and slow deactivation result in slow tail currents with a peak size proportional to the number of channels opened by the prepulse. To examine the inhibitory action of drugs on hERG1 channels, we determined maximum hERG1 inward tail currents at −120 mV following repetitive 1 s prepulses to +40 mV (Figure 1b). To enhance inward current amplitudes, measurements were performed with an external K+ concentration of 40 mM.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of whole-cell hEAG1 and hERG1 currents by LY97241. Superposition of whole-cell current recordings from CHO and HEK293 cells, stably expressing hEAG1 (a) and hERG1 (b) channels, respectively, with the indicated concentrations of LY97241. Cells were depolarized for 1 s to +50 and +40 mV, respectively, at an interval of 14 s. Increasing concentrations of LY97241 were applied to the cells and the shown current traces were taken subsequent to block equilibration. For hEAG1 channels, block was quantified by measuring the outward current at the end of the 1-s depolarization. For hERG1 channels, peak inward current during the deactivation phase at −120 mV was measured. The current magnitudes, normalized to the control currents, are plotted in (c) as a function of the blocker concentration. The error bars are s.e.mean values for 4–8 experiments. The superimposed curves are fits according to the Hill equation (equation 1)

Representative current traces from hEAG1 and hERG1 channels in the presence of increasing concentrations of LY97241 are shown in Figure 1a and b, respectively. Block by LY97241 was determined 8 min after drug application for hERG1 and 4 min after drug application for hEAG1 to quantify the concentration dependence, shown in Figure 1c. The data were fitted with Hill functions (equation 1)yielding IC50 values of 4.9±1.1 nM and 2.2±0.4 nM (see Table 1) for hEAG1 and hERG1 channels, respectively. hEAG1 channels transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells were also potently blocked by LY97241 (IC50: 8.3±1.4 nM; P=0.08 with respect to hEAG1 in CHO cells). Thus, LY97241 is an efficient inhibitor of hEAG1 channels as it blocks in the nanomolar concentration range similarly to hERG1 channels.

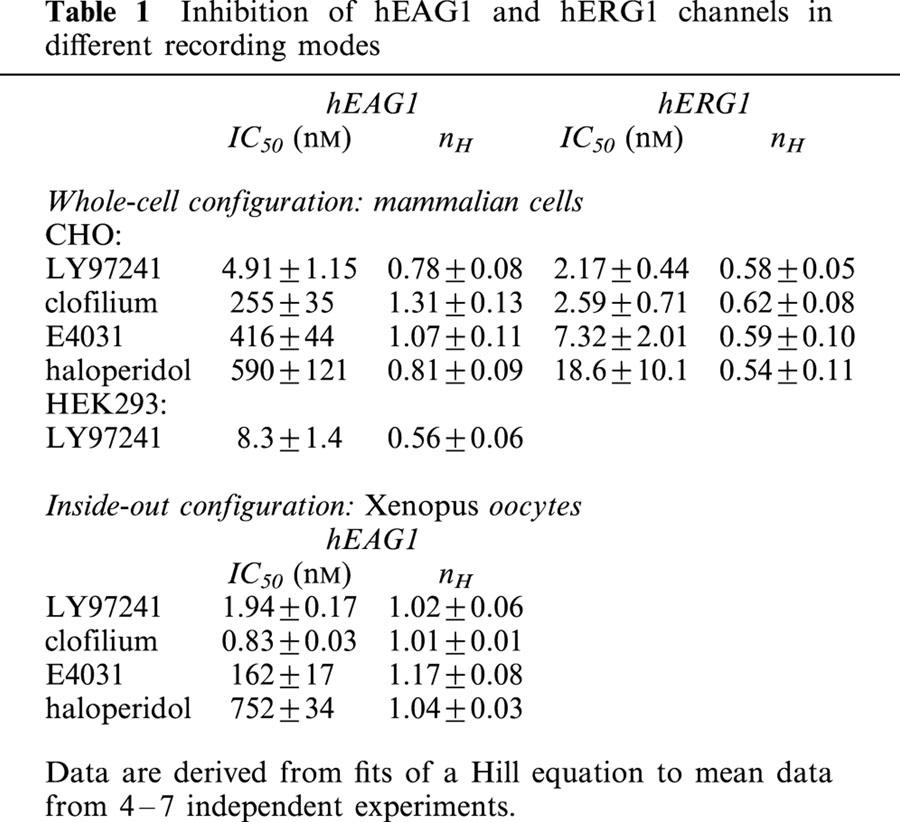

Table 1.

Inhibition of hEAG1 and hERG1 channels in different recording modes

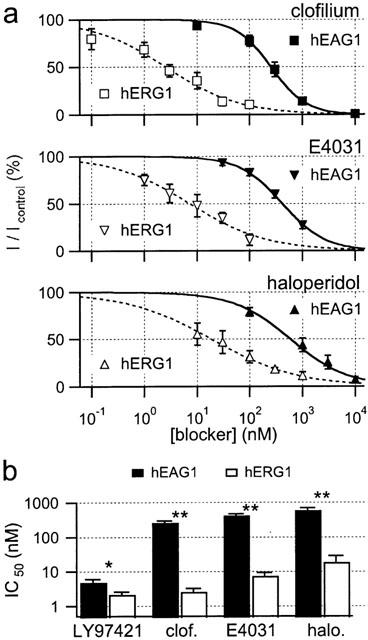

Inhibition of hEAG1 channels by other typical blockers of hERG

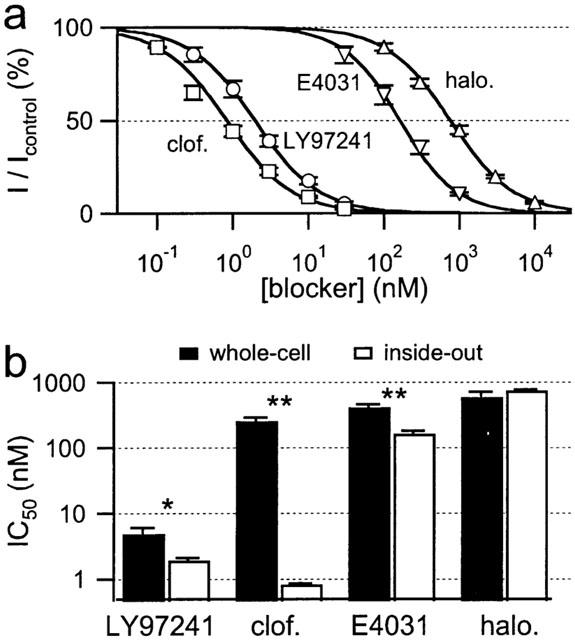

As shown for LY97241, also other ‘hERG-specific' channel blockers may potently inhibit hEAG1 channels in mammalian cells. Therefore, using the same protocol as for LY97241, we tested clofilium, a class-III anti-arrhythmic compound structurally related to LY97241 (see Figure 6), the classical hERG blocker E4031, as well as the antipsychotic drug haloperidol for their ability to inhibit hEAG1 and hERG1 channels expressed in mammalian cells. Dose-response curves for all hERG blockers tested are shown in Figure 2a. The corresponding IC50 values and Hill coefficients are listed in Table 1. As summarized in Figure 2b, all hERG blockers tested also inhibited hEAG1 channels albeit with 1–2 orders of magnitude lower potency. In contrast to LY97241, all drugs tested clearly discriminated between hERG1 and hEAG1 channels.

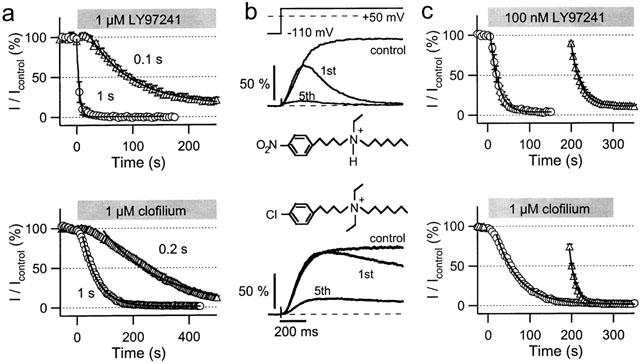

Figure 6.

Contributions of drug accessibility and channel gating to hEAG1 block by LY97241 and clofilium in CHO cells. (a) Onset of hEAG1 channel inhibition by LY97241 (top panel) and clofilium (lower panel). hEAG1 currents were repetitively evoked every 5 s by +50-mV depolarizations of the indicated durations from a holding potential of −110 mV. Currents at the end of the pulses were plotted against the time, where time zero indicates the start of drug application. The continuous curves are single exponentials, fitted to the mean data (n=4). (b) hEAG1 current recordings upon depolarization to +50 mV, normalized to the maximum current amplitude determined under control conditions. The traces shown are averages from four cells and were recorded prior to drug application (control) and 200 s following drug application, when repetitive depolarizations (the first (1st) and fifth (5th) pulses are shown) were started. (c) Currents at the end of the repetitive depolarizations were plotted against the time and fitted with mono-exponential functions. Since 1 μM LY97241 led to an almost full inhibition of hEAG1 currents during the first depolarization (panel b, top traces) a concentration of 100 nM LY97241 was used.

Figure 2.

Block of hEAG1 (CHO) and hERG1 (HEK293) channels by clofilium, E4031 and haloperidol, as indicated. (a) Dose-response curves for hEAG1 (filled symbols) and hERG1 (open symbols) channels were obtained as described in Figure 1. Data were averaged from 4–6 experiments and fitted to the Hill equation (equation 1). (b) IC50 values of hEAG1 (black bars) and hERG1 (white bars) channel inhibition by the four drugs tested.

The data show that LY97241 is a potent inhibitor of both, hERG1 and hEAG1 channels (Figure 2b). However, only hEAG1 – not hERG1 – channels seem to be extremely more sensitive to LY97241 compared to the structurally related clofilium. Therefore, we characterized the inhibition of hEAG1 channels by LY97241 in more detail.

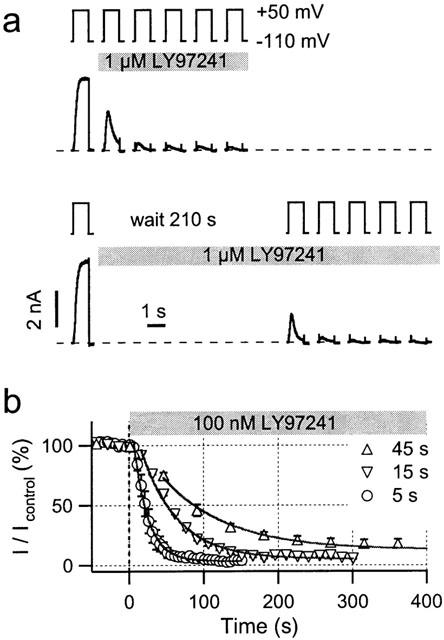

Use-dependence of hEAG1 block by LY97241

Initial block experiments indicated that the onset of channel block by LY97241 is rather slow. Hence, we analysed the inhibitory action of 1 μM LY97241 monitored by 1-s depolarizations to +50 mV. Drug was either applied during repetitive pulses (Figure 3a, upper panel) or 3.5 min before depolarization cycles were resumed (Figure 3a, lower panel). Inhibition develops over time and requires channel opening, indicative of an open-channel block. As shown in Figure 3b, inhibition by 100 nM LY97241 is also slower in onset and weaker at equilibrium for longer intervals between depolarizations. Fits of single exponential functions to the data yielded time constants of 19, 49 and 86 s and a maximum steady-state block of 97, 95 and 87% for pulse intervals of 5, 15 and 45 s, respectively.

Figure 3.

Use-dependence of hEAG1 block by LY97241. (a) Whole-cell current recordings of hEAG1 channels in CHO cells before and after application of 1 μM LY97241 elicited by 1-s depolarizations to +50 mV at an interval of 14 s. Compared to the pulse length, the interpulse interval is not drawn to scale. The first current traces were recorded in the absence of drug. The first trace in the presence of drug leads to a marked increase in current (channel opening) followed by a decrease (block). In subsequent pulses the channels largely remain blocked. The current responses do not obviously depend on whether drug was applied immediately (top) or 210 s before depolarization (bottom). (b) Currents at the end of 1-s depolarizations applied at different frequencies were normalized to the control current before application of 100 nM LY97241 and plotted against the time. Solid lines are drawn according to fits of single exponential functions to the data (n=3).

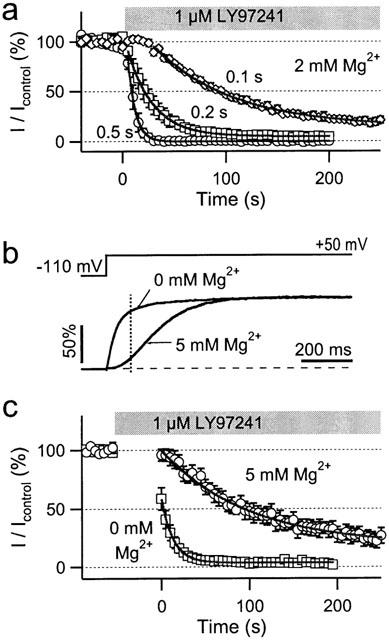

The use-dependence of hEAG1 channel inhibition was further analysed with respect to the length of depolarization applied at a fixed frequency. Reducing the depolarization length from 0.5 s down to 0.1 s resulted in a marked slowing of hEAG1 channel inhibition by 1 μM LY97241. In addition, the steady-state block obtained was weaker (Figure 4a). Mono-exponential fits yielded time constants (τb) for the onset of block of 7, 25 and 77 s with a maximum block of 100, 95 and 86%, for 0.5-, 0.2- and 0.1-s depolarizations, respectively.

Figure 4.

Pulse length dependence of hEAG1 channel inhibition by LY97241. (a) hEAG1 currents in CHO cells were repetitively evoked every 5 s by +50 -mV depolarizations of the indicated durations from a holding potential of −100 mV. Currents at the end of the pulses were plotted against the time, where time zero indicates the application of 1 μM LY97241. The continuous curves are single exponentials, fitted to the mean data (n=4). (b) Normalized hEAG1 currents in response to the indicated pulse protocol in the presence and absence of 5 mM Mg2+ in the extracellular solution. The vertical dashed line indicates 100 ms after pulse start. (c) Onset of current block by 1 μM LY97241 with a pulse interval of 5 s and a pulse duration of 100 ms in the presence and absence of 5 mM Mg2+ in the extracellular solution. The continuous curves are single-exponentials with time constants of 13.4 and 99.1 s for 0 and 5 mM Mg2+, respectively (n=4).

Interestingly, using short 0.1-s depolarizations the onset of block followed rather a sigmoid than an exponential time course, indicating an involvement of channel gating if pulses become too short to obtain steady-state block within one pulse. As shown in Figure 4b, hEAG1 activation gating is strongly affected by extracellular Mg2+: 5 mM external Mg2+ slowed down hEAG1 channel activation such that after 100 ms at +50 mV only 15.6±1.3% (n=5) of the maximum open probability was reached, compared to 81.6±2.8% (n=4) in the absence of Mg2+. Using repetitive 0.1-s depolarizations we analysed the onset of inhibition 50 s after application of 1 μM LY97241 in external solution containing either 0 or 5 mM Mg2+. In 5 mM external Mg2+ block developed slowly (τb=99 s) to 82% maximum block. Without Mg2+, already the first depolarization caused substantial block; steady-state was obtained at 97% (τb=13 s). This clearly shows an involvement of channel gating in the onset of block. The higher the open probability of the channel population, the faster the inhibition occurs and the stronger the maximum block becomes.

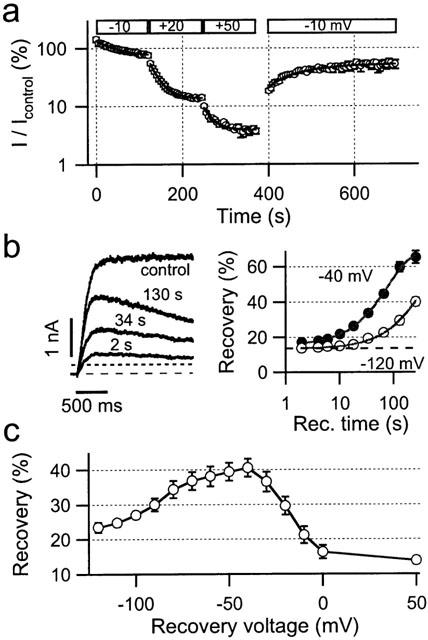

Voltage-dependence of hEAG1 block by LY97241

Since under steady-state conditions the open probability of hEAG1 channels is a function of the voltage, we analysed the onset of block by 100 nM LY97241 at different voltages. Inhibition was monitored via repetitive 1-s depolarizations applied every 5 s from −100 mV. Normalized current amplitudes were plotted against the time (Figure 5a) and fitted with mono-exponential functions yielding time constants of 53, 22 and 21 s for the onset of inhibition and maximum block of 29, 86 and 96% at −10, +20, and +50 mV, respectively. Repetitive depolarizations to −10 mV, after (>95%) steady-state inhibition at +50 mV, resulted in a marked release of block. Hence, inhibition of hEAG1 channels by LY97241 is voltage dependent and reversible.

Figure 5.

Voltage dependence of hEAG1 channel inhibition by LY97241 in CHO cells. (a) Onset of hEAG1 channel inhibition after 200-s preincubation of the cells in 100 nM LY97241 for repetitive 1-s depolarizations, as indicated, on a logarithmic scale. Solid lines indicate single-exponential fits to the data points. (b) Time dependence of recovery from LY97241 inhibition of hEAG1 channels. Representative hEAG1 current responses elicited by depolarizations to +50 mV (left panel) before blocker application (control) and after blocker equilibrium following recovery pulses to −40 mV of the indicated length. The dashed line indicates zero current level, the dotted line indicates the current amplitude for maximum block at the end of the 10-s pulses. Recovery, normalized to the control current, was plotted against the length of the recovery pulses to either −40 or −120 mV (right panel). Solid lines are drawn according to single exponential fits to the mean data (n=3–6). The dashed line indicates maximum recovery observed under repetitive 10-s depolarizations (30-s interval) without application of recovery pulses. (c) Voltage dependence of recovery from LY97241 block of hEAG1 channels. Peak current amplitudes, following 45-s recovery-pulses to different voltages were normalized to the control current before blocker application and plotted against the recovery voltage.

Interestingly, the first depolarization to −10 mV following preincubation of the cell in drug-containing solution resulted in a current increase to 142±14% (n=5), suggesting additional effects of LY97241 on gating characteristics of hEAG1 channels.

We next analysed the recovery from block at different voltages. Maximum block was obtained by applying repetitive 10-s depolarizations to +50 mV every 30 s from a holding potential of −110 mV after addition of 100 nM LY97241. Under these conditions the current at the end of the 10-s depolarizations and the maximum peak current were measured and normalized to the control value before blocker application to calculate maximum inhibition (97±1%) and recovery (14±1%, n=20). To induce additional recovery, conditioning pulses of increasing length to either −40 or −120 mV were applied prior to the 10-s depolarization. Figure 5b (left panel) shows representative current recordings before blocker application as well as following maximum inhibition and conditioning recovery pulses of different lengths at −40 mV. Percentage recovery was plotted as a function of the recovery time in Figure 5b (right panel) for −40 and −120 mV recovery voltage. Fits with mono-exponential functions yielded maximum recoveries of 68.5 and 65.7% with time constants of 79.6 and 355 s for −40 and −120 mV, respectively. Hence, recovery occurs at both voltages tested, but more than 4 fold faster at −40 mV compared to −120 mV.

To analyse the voltage dependence of recovery in more detail we applied 45-s recovery pulses to different voltages prior to the monitoring 10-s depolarizations. Obviously, recovery is voltage dependent with a maximum around −40 mV (Figure 5c). For higher voltage additional re-block might account for the apparently weaker recovery. At lower voltages recovery might be reduced due to trapping of the blocker within the closed channel. To test this hypothesis we induced constant high recovery by applying a first 2-min conditioning pulse to −40 mV, followed by a second hyperpolarizing pulse to −120 mV of different length. Then the monitoring 10-s pulse to +50 mV was applied to calculate recovery from the peak current. The percentage of recovery slightly increased from 49.5±4.7 over 52.5±5.2 to 53.7±8.6% (n=5) with the length (2, 40 and 160 s) of the second hyperpolarizing pulse (data not shown). This suggests that at −120 mV the weaker recovery is due to trapping of LY97241 within the pore of hEAG1 channels.

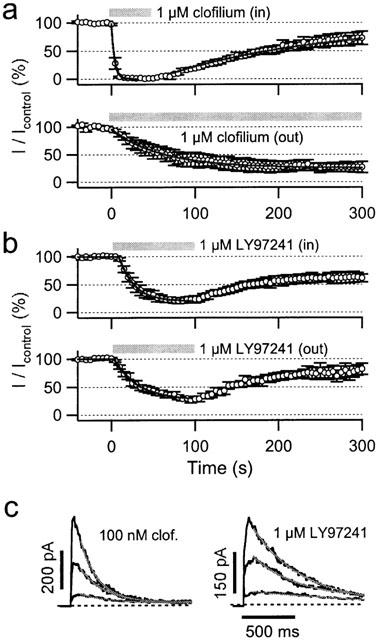

Differences between hEAG1 channel inhibition by LY97241 and clofilium

LY97241 and clofilium are structurally related compounds (Figure 6). However, in the whole-cell mode they inhibit hEAG1 channels to a very different degree (Figure 2b). To shed light on the underlying mechanisms, we analysed the clofilium inhibition of hEAG1 channels in more detail. Like for LY97241 block, inhibition by clofilium cumulatively developed, becoming faster with longer depolarizations (Figure 6a). Short depolarizations also led to a sigmoid onset of inhibition for clofilium. Mono-exponential fits yielded time constants of 54 and 214 s for 1-s and 0.2-s depolarizations, respectively. Thus, onset of block is clearly slower for clofilium than for LY97241.

Accessibility problems for the drugs to reach their binding site(s) may cause this difference. To test this hypothesis we preincubated the cells in solutions containing 1 μM LY97241 and clofilium, respectively, for 200 s before taking current records. Figure 6b shows representative current recordings before and after blocker application. For LY97241 the first depolarization led to almost complete inhibition of the current, while for clofilium the onset of block was clearly slower. Figure 6c shows a direct comparison of the time courses of inhibition for LY97241 and clofilium either directly following drug application or after a 200-s preincubation period. Mono-exponential fits to the data points yielded time constants of 54 and 14 s for 1 μM clofilium and 19 and 23 s for 100 nM LY97241 without and with preincubation, respectively. While without substantial effect for LY97241, preincubation of the cells in clofilium-containing solution led to a strong acceleration of the onset of inhibition. Also the maximum inhibition increased from 22% (without preincubation, IC50=266 nM, data from Figure 2) over 82% after 200 s preincubation to 95% after 400 s preincubation, corresponding to estimated IC50 values of 24 and 5 nM, respectively. This clearly shows that drug accessibility problems strongly affect onset and strength of hEAG1 block by clofilium.

Clofilium binds from the intracellular side

To test whether the reduced accessibility for clofilium is due to an intracellular binding site we expressed hEAG1 channels in Xenopus oocytes and recorded currents in the inside-out and outside-out excised patch configuration. As shown in Figure 7a, inhibition by 1 μM clofilium occurs 16 fold faster when clofilium was applied from the intracellular side. Time constants for onset of inhibition were 4 and 61 s with maximum inhibition of 100 and 75%, obtained in the inside-out and outside-out configuration, respectively. Interestingly, using the same experimental conditions for LY97241, the speed of onset was almost indistinguishable between application from inside and outside (Figure 7b). Mono-exponential fits yielded time constants of 19 and 29 s with maximum inhibition of 80 and 74%, for data obtained in the inside-out and outside-out configuration, respectively. Recovery from block upon washout was very slow in all cases. The data clearly show that clofilium blocks faster, when applied intracellularly, while LY97241 easily reaches its binding site from both sides of the membrane. Similar results were obtained for excised patches from hEAG1-expressing CHO cells. Using the same protocols as in Figure 7a, time constants for block by 1 μM clofilium were 2.1 s in the inside-out and 20 s in the outside-out configuration.

Figure 7.

Block of hEAG1 channels by clofilium and LY97241 in the inside-out configuration. (a, b) hEAG1 currents (n=4) were measured from excised patches of Xenopus oocytes. The pulse protocol was 0.2-s depolarization from a holding potential of −110 mV at an interval of 5 s. The application of drugs is indicated by the gray bars. Clofilium blocks the channel quickly when applied in the inside-out configuration. LY97241 blocked the channels slowly in both patch configurations. The recovery upon washout of drug was slow (time constants in the order of 100 s) in all cases. (c) Onset of block was also assessed after preincubation of inside-out patches with either 100 nM clofilium (left) or 1 μM LY97241 (right) at a prepulse potential of −100 mV. To obtain full recovery between subsequent depolarizations, patches were washed at −40 mV for 3 min. Depolarizations to 0, 40 and +80 mV cause channel opening and subsequent block, approximated with single-exponential functions. Note that the onset of block is much slower for LY97241 although at 10-times higher concentration than clofilium.

To gain further insight into the underlying mechanism we preincubated inside-out patches from Xenopus oocytes for 10 s in blocker-containing solution and assessed the onset of block during long depolarizations. Figure 7c shows representative current recordings upon depolarizations to 0, +40, and +80 mV in the presence of 100 nM clofilium (left panel) and 1 μM LY97241 (right panel). The speed of onset was quantified by mono-exponential fits to the current decay, yielding time constants of 0.71±0.26, 0.59±0.12, and 0.45±0.23 s (100 nM clofilium, n=3) and 1.18±0.27, 0.88±0.26, and 0.71±0.17 s (1 μM LY97241, n=3) for depolarizations to 0, +40, and +80 mV, respectively. Although very different in the time course of block, the voltage dependencies of the on-rate are very similar for clofilium and LY97241. Hence, when applied to inside-out patches, clofilium inhibits hEAG1 channels faster and more strongly than LY97241.

Inhibition of hEAG1 channels by hERG blockers in the inside-out configuration

Since also other hERG-blockers may inhibit hEAG1 channels more potently when applied from the intracellular side, we analysed the concentration dependencies of hEAG1 block by LY97241, clofilium, E4031, and haloperidol in the inside-out patch configuration. Inhibition was determined 3 min after drug application using repetitive 1-s depolarizations to +50 mV. Hill fits to the data (Figure 8a) yielded the IC50 values and Hill coefficients, listed in Table 1. Thus, LY97241 and clofilium are highly potent blockers of both hEAG1 and hERG1 channels and even E4031 and haloperidol substantially block hEAG1 channels in the sub-micromolar range.

Figure 8.

Dose dependence of hEAG1 channel block in excised patches from Xenopus oocytes. Inhibition was determined 3 min after drug application from the current at the end of 1-s depolarization to +50 mV applied every 6 s from a holding potential of −110 mV. (a) Dose-response curves for hEAG1 channel block in inside-out patches for the indicated drugs. The continuous curves are Hill fits yielding the IC50 values shown in b and listed with the corresponding Hill coefficients in Table 1. All data points are mean values±s.e.mean from five independent experiments. (b) Comparison of IC50 values for steady-state block of hEAG1 channels in the whole-cell mode (black) and in inside-out patches (white) for the indicated drugs.

In Figure 8b the IC50 values are compared with those obtained previously in the whole-cell configuration. For haloperidol no difference in inhibition was observed for inside-out and whole-cell configuration. For LY97241 and E4031 a moderate increase in the block efficiency was found in the inside-out configuration. Only for clofilium a more than 100 fold increase in the inhibition potency was observed, when applied from the intracellular side, which suggests that the positive charge of clofilium is the major determinant for this particular phenomenon.

Discussion

LY97241 and clofilium are very potent blockers for hEAG1 channels

In this study we show that LY97241 and clofilium block hEAG1 and hERG1 channels with similar potency in the low nanomolar concentration range. E4031 and haloperidol inhibit hEAG1 channels at submicromolar concentrations, but the block is weaker than for hERG1 channels. Thus, this study quantitatively compares several drugs, formerly considered hERG-specific blockers, under similar conditions with respect to their effect on hEAG1 and hERG1 channels, expressed in mammalian cells. The results will be of special interest for comparison of pharmacological properties of currents measured in native preparations, since IC50 values formerly determined for hERG1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Herzberg et al., 1998; Suessbrich et al., 1997a, b) were at least 10-times higher than the values reported here. Similar differences have been found for dofetilide block of bovine EAG1 channels expressed either in Xenopus oocytes or in CHO cells (Ficker et al., 1998), indicating that the dependence of block efficiency on the expression system is a general phenomenon. It should be noted that even expression in different mammalian cells may not lead to identical results. We report here a slightly greater IC50 value for LY97241 block of hEAG1 channels when expressed in HEK293 cells compared to expression in CHO cells. It is conceivable that the expression patterns of auxiliary subunits as well as posttranslational channel modifications contribute to this phenomenon.

Nevertheless, the Xenopus oocyte expression system is a useful system to investigate the specificity of drugs for different ion channels: Suessbrich et al. (1997b) showed that LY97241 (3 μM) can clearly discriminate between hERG (full inhibition) and several different cardiac potassium channels (less than 5% inhibition). As expected, LY97241 (1 μM) and clofilium (10 μM) inhibited hEAG1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by about 90% (data not shown), indicating that LY97241 and clofilium (in equilibrium) may be used as specific blockers of both hEAG1 and hERG1 channels.

In contrast, haloperidol and E4031 cannot be used as specific hEAG1 blockers. Haloperidol blocks hERG1 channels with 30 fold higher efficiency than hEAG1. In addition, haloperidol has been shown to block also several cardiac potassium channels (Suessbrich et al., 1997a) as well as sodium and calcium channels (Ogata et al., 1989). E4031 discriminates between hERG1 and hEAG1 channels more strongly (60 fold higher potency) and, therefore, constitutes a hERG-specific inhibitor as has been published previously (Herzberg et al., 1998; Sun & Herness, 1996). However, it has to be emphasized that E4031 leads to a marked inhibition of hEAG1 channels at concentrations of 100 nM and higher. This finding has strong implications for the use of E4031 to isolate hERG currents in native neuronal cell preparations, where EAG channels might also be expressed (Ludwig et al., 2000).

LY97241 and clofilium bind in the pore of hEAG1 channels

In this study we showed that LY97241 and clofilium block the open channel. Inhibition requires depolarization and is enhanced by all conditions increasing the channel open probability: higher depolarization frequency, longer pulses, faster channel activation in the absence of extracellular Mg2+, and higher voltage. Once inside the pore, the blocker can be trapped if the channel gate closes. Recovery from block occurs slowly (within minutes) with a maximum at −40 mV, the activation threshold of hEAG1 channels.

Similar characteristics of block by clofilium and LY97241 have been observed for Kv1.5 channels (Steidl & Yool, 2001). However, besides the approximately 100 fold lower potency of block by both substances, inhibition of Kv1.5 channels differs substantially from that of hEAG1 channels: First, steady-state inhibition of Kv1.5 channels is about 4 fold stronger for clofilium than for LY97241. Second, onset of block as well as recovery from block are faster (milliseconds versus several seconds). Third, recovery from block for LY97241 was less voltage dependent, compared to clofilium. These striking differences suggest the existence of a specific binding site within the pore of hEAG1 channels, different from the binding site in Kv1.5 channels.

Clofilium accesses the binding site in hEAG1 channels from the inside

The faster onset of block of hEAG1 channels by clofilium in the inside-out versus outside-out configuration indicates that clofilium only can block the channel from the cytoplasmic side. Similar results have been observed by Malayev et al. (1995) who showed that Kv1.5 channels are blocked more rapidly and more than 2 fold stronger when clofilium is applied from the intracellular side. The rate of onset of clofilium block was not voltage dependent for Kv1.5 channels, but recovery was slower at more hyperpolarized potentials, indicating an activation trap mechanism of channel inhibition.

For LY97241 we detected no differences in onset of hEAG1 channel inhibition in the inside-out versus outside-out configurations. Most surprisingly, the onset of inhibition when applied from the intracellular side was slower, compared to clofilium. One explanation for this phenomenon would be that LY97241 is able to inhibit hEAG1 channels only in its charged (i.e. protonated) form. Another obvious explanation would be that the permanent charge of clofilium helps to enter the channel at positive membrane potentials. This would imply a strong voltage dependence of the onset of block for clofilium, but not for LY97241. In fact, the onset of block by clofilium is voltage dependent, being approximately 1.6 fold faster at +80 mV, compared to 0 mV. However, the onset of inhibition of LY97241, which is slower even at 10 fold higher concentration, shows similar voltage dependence (1.7 fold faster at +80 mV, compared to 0 mV). Hence, the voltage dependence of onset of inhibition by both compounds seems to arise either from inhibition by charged molecules only or from the voltage dependence of channel open probability.

The charge of clofilium, however, may be of importance for the faster onset of block, compared to LY97241. Since both drugs block the open channel and can be trapped by closure of the activation gate, both drugs likely bind within the central cavity of the channel (Doyle et al., 1998; Mitcheson et al., 2000b). In fact, clofilium and LY97241 may bind near the selectivity filter, similar to tetrabutylammonium binding in KcsA channels (Zhou et al., 2001). If so, LY97241 in its deprotonated form may interact with the hydrophobic walls of the intracellular entry pathway, slowing the drug on its way to the binding site. In contrast, the permanent positive charge of clofilium, as proposed for permeating ions, may prevent or diminish such interactions and the drug reaches its binding site more rapidly.

Clofilium and LY97241 appear to bind to a specific binding site within the channel cavity, where they can be trapped efficiently by channel closure that does not seem to be affected by the presence of the drugs. We cannot exclude different binding sites for the two drugs. However, the similar off-rates observed in the recovery experiments (not shown for clofilium) favor a common binding site, as one would also expect from the structural similarities of both drugs.

One may further speculate that hEAG1 and hERG1 channels share a common binding site. However, inhibition of hERG1 channels by LY97241 and clofilium, but also by methanesulphonanilides, is strongly enhanced by the inactivation process. This may explain the stronger block of hERG1 compared to the non-inactivating hEAG1 channels by E4031 but seems to contradict the almost identical potency of LY97241. Future mutagenesis studies have to be performed to identify the influences of inactivation and binding sites in both channels on the molecular level.

Physico-chemical differences of LY97241 and clofilium give rise to a strong dependence of channel block on the recording mode

Clofilium and LY97241 differ in two positions, the para-group of the aromatic ring and the substitution of the amine. Previous studies on the inhibition of hERG1 channels by LY97241 and clofilium suggested an open-channel block with a common internal binding site (Suessbrich et al., 1997b). For hEAG1 channels the onset of block for clofilium was substantially slower than for LY97241 when assayed in the whole-cell mode, resulting in an apparently weaker block before equilibrium was reached. For hERG1 channels we did not find such a striking difference. The onset of block of hERG1 channels for all drugs tested was slower compared to hEAG1 channels. We cannot account for the underlying reasons, but it seems to be a general phenomenon that has also been observed by others (Ficker et al., 1998). Differences in gating behaviour of hERG1 and hEAG1 channels, in particular the slower activation (Schönherr & Heinemann, 1996) might underlie the slower onset of channel inhibition. Hence, longer drug exposures are necessary to analyse hERG1 channel block, which in turn mask apparently weaker inhibition. In fact, blocker equilibration may take very long depending on the drug tested: Castle (1991) reported that steady-state inhibition of rat ventricular potassium currents by clofilium was not attained for exposure times shorter than 30 min, compared to 5 min for a tertiary homologue LY97119. This may also imply that, if hERG1 inhibition is analysed in the inside-out configuration, clofilium will be more potent than LY97241. Unfortunately we were not able to perform these experiments systematically, because hERG1 channels showed almost complete rundown following patch excision.

For hEAG1 channels we showed that the onset of block by clofilium is very much slower in the whole-cell (Figure 6b) than in the inside-out (Figure 7c) configuration. Therefore, we can conclude that in the whole-cell mode the effective clofilium concentration within the cell is several orders of magnitude lower than outside of the cell. This may apply for all hydrophilic drugs, since the intracellular concentration resembles a dynamic equilibrium between entry through the cell membrane and exit into the hydrophilic phase of the patch pipette, both processes that strongly depend on the hydrophobicity of the drug. Hence, the assessment of channel blockade by weakly membrane permeable drugs that access an intracellular binding site in the whole-cell mode is to be considered with great caution. Perforated-patch recordings or comparison of inside-out and outside-out patch-clamp recordings are more appropriate. In clinical applications it is expected that the accumulation of the substances in the cells does not depend that strongly upon the physico-chemical properties. However, this only holds true in the absence of active transport systems (multi-drug resistance receptors).

Possible applications of EAG inhibitors

Thus far no specific inhibitors of EAG channels have been identified. They would be helpful on the one hand to identify the physiological role of EAG channels in the brain (Ludwig et al., 2000). On the other hand, specific EAG blockers are desirable for anti-cancer applications, in particular, to test, whether the proposed oncogenic feature of EAG (Pardo et al., 1999) depends on channel activity or not.

In this study we identified the first highly potent inhibitors of hEAG1 channels and characterized their mechanism of channel block. However, the usefulness of LY97241 for testing the involvement of EAG channels in cell-cycle regulation, like recently reported for imipramine (Gavrilova-Ruch et al., 2002), has to be questioned. As we have shown, channel inhibition strongly depends on open probability, which is a function of membrane voltage. Typical resting potentials of cancer cells, which may become even more hyperpolarized upon expression and activation of hEAG1 channels, range around −30 mV. At such potentials LY97241 is rather ineffective and may therefore have no strong influence on EAG channels, and hence on cell proliferation. Moreover, inhibitors that bind to an extracellular site on EAG channels seem more appropriate to prevent problems arising from the membrane permeability of the drug and from activity of multi-drug resistance systems.

LY97241 may still be a useful tool for identifying EAG channels in neuronal cell preparations, since ERG channels, which are also blocked by this compound, can easily be distinguished from EAG channels on the basis of their voltage dependent inactivation and their very slow tail currents.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for technical assistance by S. Arend and A. Roßner and for helpful discussions with R. Schönherr. This work was supported by the Max Planck Society and the DFG (He 2993/2, 2993/4).

Abbreviations

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-O-O′-bis(2-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- HEPES

N-(hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulphonic acid)

- IKr

rapid component of the cardiac delayed rectifier potassium current

- Kv channel

voltage dependent potassium channel

References

- BAUER C.K., SCHWARZ J.R. Physiology of EAG K+ channels. J. Membrane Biol. 2001;182:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTLE M.A. Selective inhibition of potassium currents in rat ventricle by clofilium and its tertiary homolog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;257:342–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL CAMINO D., HOLMGREEN M., LIU Y., YELLEN G. Blocker protection in the pore of a voltage gated K+ channel and its structural implications. Nature. 2000;430:321–325. doi: 10.1038/35002099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOYLE D.A., MORAIS CABRAL J., PFUETZNER R.A., KUO A., GULBIS J.M., COHEN S.L., CHAIT B.T., MACKINNON R. The structure of the potassium channel: Molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FICKER E., JAROLIMEK W., KIEHN J., BAUMANN A., BROWN A.M. Molecular Determinants of Dofetilide Block of HERG K+ Channels. Circ. Res. 1998;82:386–395. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANETZKY B., WU C.F. Neurogenetic analysis of potassium currents in Drosophila: Synergistic effects on neuromuscular transmission in double mutants. J. Neurogenet. 1983;1:17–28. doi: 10.3109/01677068309107069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAVRILOVA-RUCH O., SCHÖNHERR K., GESSNER G., SCHÖNHERR R., KLAPPERSTÜCK T., WOHLRAB W., HEINEMANN S.H. Effects of imipramine on ion channels and proliferation of IGR1 melanoma cells. J. Membr. Biol. 2002;188:137–149. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERZBERG I.M., TRUDEAU M.C., ROBERTSON G.A. Transfer of rapid inactivation and sensitivity to the class III antiarrhythmic drug E-4031 from HERG to M-eag channels. J. Physiol. 1998;511:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUDWIG J., TERLAU H., WUNDER F., BRÜGGEMANN A., PARDO L.A., MARQUARDT A., STÜHMER W., PONGS O. Functional expression of a rat homologue of the voltage gated ether à go-go potassium channel reveals differences in selectivity and activation kinetics between the Drosophila channel and its mammalian counterpart. EMBO J. 1994;13:4451–4458. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUDWIG J., WESELOH R., KARSCHIN C., KIU Q., METZER R., ENGELAND B., STANSFELD C., PONGS O. Cloning and functional expression of rat eag2, a new member of the ether-à-go-go family of potasium channels and comparison of its distribution with that of eag1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;16:59–70. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAYEV A.A., NELSON D.J., PHILIPSON L.H. Mechanism of clofilium block of the human Kv1.5 delayed rectifier potassium channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER R., HEINEMANN S.H. Characterization of an eag-like potassium channel in human neuroblastoma cells. J. Physiol. 1998;508:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.049br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER R., SCHÖNHERR R., GAVRILOVA-RUCH O., WOHLRAB W., HEINEMANN S.H. Identification of ether à go-go and calcium-activated potassium channels in human melanoma cells. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;171:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s002329900563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHESON J.S., CHEN J., LIN M., CULBERSON C., SANGUINETTI M. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000a;97:12329–12333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210244497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHESON J.S., CHEN J., SANGUINETTI M. Trapping of a methanesulfonanilide by closure of the HERG potassium channel activation gate. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000b;115:229–239. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.3.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OCCHIODORO T., BERNHEIM L., LIU J.-H., BIJENGA P., SINNREICH M., BADER C.R., FISCHER-LOUGHEED J. Cloning of human ether-a-go-go potassium channel expressed in myoblasts at the onset of fusion. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGATA N., YOSHII M., NARAHASHI T. Psychotropic drugs block voltage-gated ion channels in neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 1989;476:140–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OUADID-AHIDOUCH H., LE BOURHIS X., ROUDBARAKI M., TOILLON R.A., DELCOURT P., PREVARSKAYA N. Changes in the K+ current-density of MCF-7 cells during progression through the cell cycle: possible involvement of a h-ether-a-gogo K+ channel. Receptors Channels. 2001;7:345–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARDO L.A., DEL CAMINO D., SÁNCHEZ A., ALVES F., BRÜGGEMANN A., BECKH S., STÜHMER W. Oncogenic potential of EAG K+ channels. EMBO J. 1999;18:5540–5547. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHÖNHERR R., GESSNER G., LÖBER K., HEINEMANN S.H. Functional distinction of human EAG1 and EAG2 potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 2002;514:204–208. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHÖNHERR R., HEINEMANN S.H. Molecular determinants for activation and inactivation of HERG, a human inward rectifier potassium channel. J. Physiol. 1996;493:635–642. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHÖNHERR R., LÖBER K., HEINEMANN S.H. Inhibition of human ether á go-go potassium channels by Ca2+/calmodulin. EMBO J. 2000;19:3263–3271. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHÖNHERR R., ROSATI B., HEHL S., RAO V.G., ARCANGELI A., OLIVOTTO M., HEINEMANN S.H., WANKE E. Functional role of the slow activation properties of ERG K+ channels. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:753–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIDL J.V., YOOL A.J. Distinct mechanism of block of Kv1.5 channels by tertiary and quaternary amine clofilium compounds. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2606–2613. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75904-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINBERG M.I., MOLLOY B.B. Clofilium – a new antifibrillatory agent that selectively increases cellular refractoriness. Life Sci. 1979;25:1397–1406. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUESSBRICH H., SCHÖNHERR R., HEINEMANN S.H., ATTALI F., LANG F., BUSCH A.E. The inhibitory effect of the antipsychotic drug haloperidol on HERG potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;120:968–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUESSBRICH H., SCHÖNHERR R., HEINEMANN S.H., LANG F., BUSCH A.E. Specific block of cloned Herg channels by clofilium and its tertiary analog LY97241. FEBS Lett. 1997b;414:435–438. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN X.D., HERNESS M.S. Inhibition of potassium currents by the antiarrhythmic drug E4031 in rat taste receptor cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;204:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERLAU H., LUDWIG J., STEFFAN R., PONGS O., STÜHMER W., HEINEMANN S.H. Extracellular Mg2+ regulates activation of rat eag potassium channel. Plügers Arch. 1996;432:301–312. doi: 10.1007/s004240050137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSENG G.-N. IKr: The hERG channel. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:835–849. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDENBERG J.I., WALKER B.D., CAMPBELL T.J. HERG K+ channels: friend and foe. TIPS. 2001;22:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU M., MORAIS-CABRAL J.H., MANN S., MACKINNON R. Potassium channel receptor site for the inactivation gate and quaternary amine inhibitors. Nature. 2001;411:657–661. doi: 10.1038/35079500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]