Abstract

We studied the biochemical and contractile responses of isolated human myocardial tissue expressing native receptor variants of the 389G>R β1-adrenoceptor polymorphism.

Right atrial appendage was obtained from homozygous RR patients (n=37) and homozygous GG patients (n=17) undergoing elective cardiac surgery. The positive inotropic effect of noradrenaline in these tissues, mediated through β1-adrenoceptors, was studied using electrically stimulated (1 Hz) atrial strips, as well as the effects of noradrenaline on cyclic AMP levels and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase.

Tissue from RR homozygotes (n=14) showed significantly increased inotropic potency to noradrenaline (−log EC50, M=6.92±0.12) compared to GG homozygotes (n=8, −log EC50, M=6.36±0.11, P<0.005). This difference was not dependent on tissue basal force.

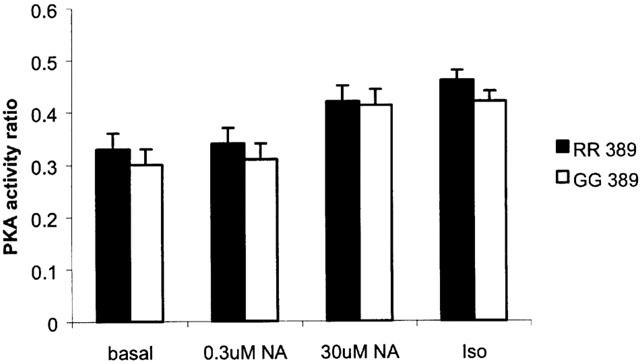

Tissue cyclic AMP levels (pmol mg−1) were also greater in RR homozygotes (basal 34.8±3.7 n=12, 300 nM noradrenaline 41.4±7.6 n=9, 30 μM noradrenaline 45.2±3.2 n=22, 0.2 mM isoprenaline 48.3±4.2 n=16) compared to GG homozygotes (basal 30.7±4.4 n=5, 300 nM noradrenaline 32.6±6.92 n=5, 30 μM noradrenaline 38.1±3.1 n=8, 0.2 mM isoprenaline 42.6±5.2 n=6, P=0.007). There were no differences between the variants in terms of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase activity.

These data provide the first evidence that enhanced G-protein coupling of the R389 β1-adrenoceptor variant reported in rodent fibroblast expression systems is also present in native human receptors. The functional consequence of this is to significantly alter the inotropic potency of β1-adrenoceptor activation depending on its genotype at the 389 position.

Keywords: β1-Adrenoceptor, G-protein, human myocardium, genetic polymorphism, cyclic AMP

Introduction

The human β1-adrenoceptor (β1-AR) mediates lipolysis in adipocytes, renin release from the juxtaglomerular cells, together with inotropic and chronotropic responses of the heart to catecholamines (Stadel & Lefkowitz, 1991). Individual responsiveness to β1-adrenoceptor activation and blockade are highly variable even allowing for confounding factors such as age, sex, pharmacokinetics and aetiology or severity of cardiac disease (Liggett et al., 1989; Martinsson et al., 1989). Of particular interest is a common variant occurring within the coding region of the β1-adrenoceptor (1165C>G), which results in a non-conservative substitution of arginine for glycine (389G>R) (Maqbool et al., 1999; Mason et al., 1999). The functional importance of this variant is suggested by its occurrence in the putative G-protein binding domain and the conservative nature of the 389R residue in all species sequenced to date. Indeed, expression in a rodent cell line has demonstrated a significant effect of the 389R variant on the functional activation of the β1-adrenoceptor as evidenced by increases in both agonist-promoted receptor binding to Gs protein and the adenylyl cyclase activity compared to the 389G variant (Mason et al., 1999). A second and less common variant (145G>A), results in a non-conservative substitution of glycine for serine (49G>S) (Borjesson et al., 2000). By analogy with N-terminal substitutions of the β2-adrenoceptor, expression studies have demonstrated that despite similar affinities for both agonists and antagonists, the 49S receptor variant was relatively resistant to agonist promoted downregulation compared to the 49G variant (Rathz et al., 2002).

In vitro expression studies may not predict, however, the impact of these variants on intact human tissue responses to β1-adrenoceptor activation. Hence, the objective of our study was to use intact human atrial myocardium expressing native variant β1-adrenoceptors to determine whether the 389G>R genotype does influence the response to β1-adrenoceptor stimulation. Our results provide the first in vitro evidence that the 389R variant shows increased responsiveness to the β1-agonist noradrenaline in intact myocardial tissue, and that this is associated with greater cyclic AMP generation.

The cumulative dose response curves were presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the British Hypertension Society (Sandilands et al., 2001).

Methods

Subjects

Five hundred and seventy-two consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery at Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, U.K. were recruited and consented to the study at preoperative assessment. After 389G>R genotyping in the week preceding surgery, 366 homozygous individuals were identified and of these 206 were excluded because they showed either significant angiographic evidence of LV dysfunction or were taking a beta-blocker other than atenolol (see below). Atrial tissue was collected from as many as possible of the remaining 160 subjects: the main reasons for failure were cancellation of the surgery at the scheduled time, or decision by the surgeon to leave the atrial appendage in place. The Huntingdon Local Research Ethics Committee approved the study.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from whole blood using an adaptation of a previous method (Lahini & Nurnberger, 1991). The genotypes of the β1-adrenoceptor encoding amino acid substitutions at position 49 (Gly or Ser) and position 389 (Arg or Gly) were delineated using PCR/RFLP (Maqbool et al., 1999; O'shaughnessy et al., 2000). Briefly, these polymorphic loci were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) generating products that were subsequently digested by Eco0109 I and BcgI respectively. The PCR used 100 ng of DNA in a total volume of 20 μl containing 200 μM of each dNTP (Roche Molecular), 1.2 mM magnesium, ×1 of the supplied reaction buffer (Gibco BRL), 5% DMSO and 1 U of Taq enzyme (Gibco BRL). The primers used (at a final concentration of 1 μM) were: 5′-CCGGGCTTCTGGGGTGTTCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGCGAGGTGATGGCGAGGTAGC-3′ (antisense) for the 49G>S reaction; 5′-CATCATGGGCGTCTTCACGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGGCTTCGAGTTCACCTGC-3′ (reverse) for the 389G>R reaction. Amplification included an initial denaturation of 98°C for 3 min, with 35 cycles of 98°C for 45 s, 62°C for 60 s, 72°C for 30 s for G49S and 98°C for 30 s, 50°C for 60 s and 72°C for 30 s for R389G. 10 μl of PCR product were then digested overnight at 37°C with 20 U of Eco0109 I (New England Biolabs), 10 μl of BSA (100 μg ml−1), 2 μl of reaction buffer (49G>S) and similarly 2 U of BcgI (New England Biolabs), 5 μl of 200 μM S-adenylmethionine, 2 μl of supplied buffer (389G>R) before separation on a 1.5% agarose gel. The genotypes were called by one of the authors (KO) and only those patients who were homozygous (either RR or GG) were considered further for tissue collection. However, the author responsible for performing the functional studies on the atrial tissue (AS) was blinded to the actual RR or GG genotype of the patients until data collection was complete.

Concentration response curves

Right atrial appendage (RAA) was collected preoperatively (before the institution of cardiopulmonary bypass) from patients undergoing routine bypass procedures (coronary artery bypass or valvular surgery) and experiments performed as previously (Kaumann et al., 1989). Tissues from patients on β1-adrenoceptor blockers other than atenolol were not harvested, since only atenolol is sufficiently water-soluble to wash out of the atrial tissue during the initial incubation in the organ bath (Hall et al., 1990). The first half of the study collected RAA tissues to specifically measure the β1-adrenoceptor concentration-response characteristics from RR versus GG patients. To do this, tissues were immediately placed after collection into oxygenated modified Kreb's solution on ice containing (in mmol l−1): Na+ 125, K+ 5, Ca2+ 2.25, Mg2+ 0.5, Cl− 98.5, SO42− 0.5, HCO3−29, HPO42− 1.0, EDTA 0.04, fumurate 5, pyruvate 5, glutamate 5, glucose 10, equilibrated with 95%O2 and 5%CO2, with deionized and distilled H2O. The RAA was then dissected into 3–4 strips (defined using the trabeculae) of 1 mm thickness whilst they were continuously oxygenated (95%O2 and 5%CO2) in Kreb's solution. Each strip was attached to a strain gauge transducer (Hugo Sachs Electronik, HSE, Force Transducer F30 type 372) using 5/0 softsilk, and paced (using field stimulation) at 1 Hz intervals with a square-wave pulse of 5 ms duration at a voltage just above threshold (<4.0 V). The set up used included a 10 ml organ bath (Linton) containing modified Kreb's solution with continuous oxygenation at a constant temperature of 37°C by means of a circulating water bath. The force of contraction was measured on a Graphtec chart recorder. A length-force curve was determined, following which the length of each strip was set to obtain 50% of the resting tension associated with maximal developed force. The tissue was pretreated with the β2-adrenoceptor antagonist ICI 118,551 (50 nM, Research Biochemicals International-RBI) and 5×10−6 M phenoxybenzamine (PBA, RBI) for 90 min followed by washout. The addition of the PBA results in irreversible blockage of both myocardial α-adrenoceptors as well as inhibition of the neuronal uptake of catecholamines in human heart (Kaumann et al., 1989). Cumulative concentration-response curves for noradrenaline were then performed in the presence of fresh ICI 118,551 (50 nM) to measure β1-adrenoceptor responses. The experiment was terminated with 0.2 mM isoprenaline followed by the addition of 6.7 mM CaCl2 to the organ bath, measuring the maximal β1-adrenoceptor-mediated and inotropic responses. Results for each patient were calculated using the average response from the tissue strips.

For the measurement of noradrenaline-stimulated cyclic AMP, a second set of tissues were collected that were separate from the ones used to generate the initial concentration-response data. These tissues were set up as above and subjected to one of the following: vehicle, a single concentration of noradrenaline (300 nM or 30 μM) or 0.2 mM isoprenaline. Phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors were not included in the organ bath at this stage, since in pilot experiments this tended to cause arrythmias. Four minutes later the inotropic response was measured and the tissue rapidly snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C for later biochemical analysis.

Biochemical analysis

Protein kinase (PKA) activity ratio was analysed in frozen atria (Kaumann et al., 1989; Murray et al., 1990). Briefly, frozen atria were homogenized with a Polytron (Kinematica) using a 7 mm probe at speed 8 for 1×10 s pulses in 40 volumes of ice cold buffer containing at pH 6.8: 10 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), then centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 6000×g. Soluble cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase was determined within 5 min of centrifugation by incubating 10 μl of resulting supernatant for 2 min at 30°C with 10 μl of 2.1 nM [32P]-γ-ATP and 50 μl of assay buffer comprising: 3.5 mM malantide, 0.35 M Na2HPO4, 14 mM MgCl2, 1.4 mM EGTA, 1.4% (w v−1) Tween 20 in the absence and presence of 2 μM cyclic AMP. The reaction was terminated with 10 μl of 1 M HCl, following which 35 μl of sample was spotted onto phosphocellulose (P81) papers. These papers were washed six times for 5 min with 0.05% (v v−1) tetraphosphoric acid/38 mM H3PO4, dried and counted in water by Cerenkov radiation. The activity ratio was calculated by dividing the radioactivity (c.p.m.) obtained in the absence of cyclic AMP by that obtained in the presence of cyclic AMP after subtracting blank values (HCl added before [32P]-γ-ATP). Cyclic AMP was also determined from the initial supernatant using an enzyme immunoassay system (Amersham-Biotrak). Firstly, 200 μl of supernatant was acidified with 0.1 volumes of 3 M HCIO4 then centrifuged for 2 min at 15,000×g. The resulting pellet was dissolved in NaOH (0.1 M) for protein determination using the copper bicinchoninic method. Secondly, the supernatant was neutralised with 1.25 volumes of freon/amine and the neutral aqueous layer assayed in duplicate with the cyclic AMP kit.

Data analysis

The organ bath and cyclic AMP measurements were performed under single blinding with the author responsible for these measurements (A.J. Sandilands) only aware that they were from a homozygous individual. All results are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean (unless otherwise stated) with statistical analysis performed using t-tests or 2-way ANOVA (with genotype and concentration as factors) and post-hoc t-testing using the SPSS package (Windows version 10) as appropriate. Statistical significance was taken as P<0.05. Cumulative concentration-response curves were fitted using fig.p software, a non-linear iterative curve-fitting program, to an asymmetric sigmoid equation (Biosoft, Elsevier version 2.98) to derive the EC50 and Emax.

Results

Patient characteristics

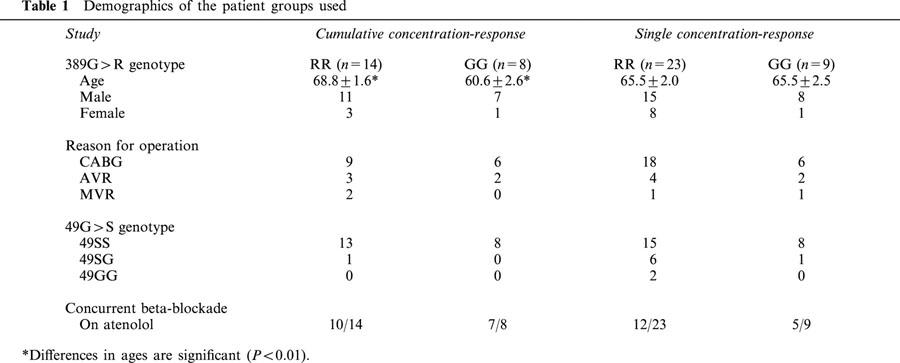

The allele frequencies of these 572 cardiac patients were similar to those previously published: RR 0.52, RG 0.36, GG 0.12 (Maqbool et al., 1999; Mason et al., 1999; O'shaughnessy et al., 2000) and SS 0.75, SG 0.20, GG 0.05 (Ranade et al., 2002). Genotype frequencies were also found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Table 1 shows the demographics of patients used in this study. Only on the basis of age were the groups significantly different with the RR subjects being slightly older than the GG subjects for the cumulative concentration-response study.

Table 1.

Demographics of the patient groups used

Effect of noradrenaline on inotropic potency

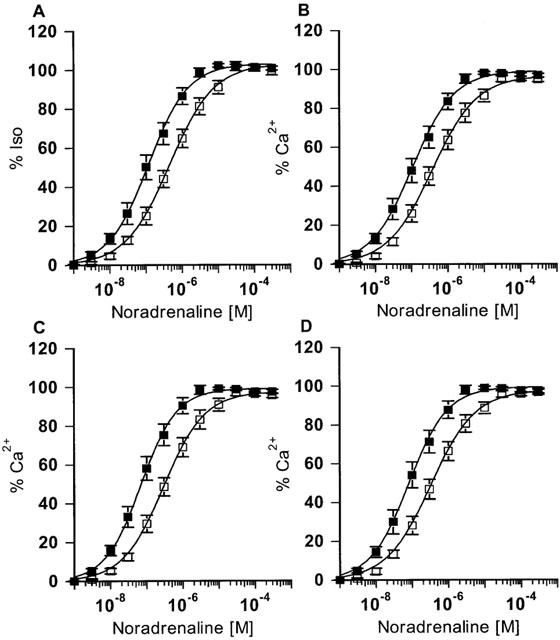

The concentration-response curves to noradrenaline in the presence of ICI 118,551 were normalized to the maximal responses with isoprenaline and calcium (Figure 1). The inotropic potency of noradrenaline is significantly greater in tissues from RR homozygotes compared to GG homozygotes with more than a half log-unit separating their EC50 s. These differences persisted when noradrenaline responses were compared to calcium in the subgroup of patients undergoing bypass-grafting alone (Figure 1C: RR homozygotes, n=9, −log EC50, M=7.13±0.11 and GG homozygotes, n=6, −log EC50, M=6.41±0.12, P<0.005) or in those patients who were concurrently beta-blocked with atenolol prior to study (Figure 1D: R389B+, −log EC50, M=7.05±0.13, n=10; G389B+, −log EC50, M=6.38±0.09, n=7, P<0.01).

Figure 1.

Noradrenaline concentration-response curves. (A) All tissues normalized to isoprenaline (0.2 mM): RR homozygotes, −log EC50, M=6.83±0.12 significantly different to GG homozygotes, −log EC50, M=6.28±0.11, P<0.005. (B) All tissues normalized to maximum calcium contraction: RR homozygotes (n=14, RR, −log EC50, M=6.92±0.12) were significantly different compared to GG homozygotes (GG, n=8, −log EC50, M=6.36±0.11), P<0.005. (C) Tissue from CABG patients only normalized to maximum calcium contraction: RR homozygotes, n=9, −log EC50, M=7.13±0.11 and GG homozygotes, n=6, −log EC50, M=6.41±0.12, P<0.005. (D) Tissue from Atenolol treated patients only normalized to maximum calcium contraction: R389B+, −log EC50, M=7.05±0.13, n=10; G389B+, −log EC50, M=6.38±0.09, n=7, P<0.01. The solid lines are the computer-fitted curves (see Methods).

Forces generated for cumulative concentration response

There was no apparent difference in absolute basal (RR 0.70±0.14 mN and GG 0.79±0.18 mN), maximal forces generated with noradrenaline (RR 1.50±0.12 mN versus GG 1.42±0.22 mN) and forces generated with isoprenaline (RR 1.45±0.13 mN versus GG 1.40±0.2 mN) for all tissues. Similarly, for patients undergoing bypass grafting, neither basal (RR 0.84±0.21 mN and GG 0.86±0.24 mN) nor maximal forces (RR 1.6±0.17 mN versus GG 1.5±0.27 mN) were different. However, there were small but significant differences in the maximal responses when compared to calcium for all tissues (RR 100.3%±1.2 and GG 96.6%±1.1, P<0.05), although this did not reach significance in the sub group of patients undergoing bypass grafting (RR 101.6%±1.7 and GG 98.2%±1.6).

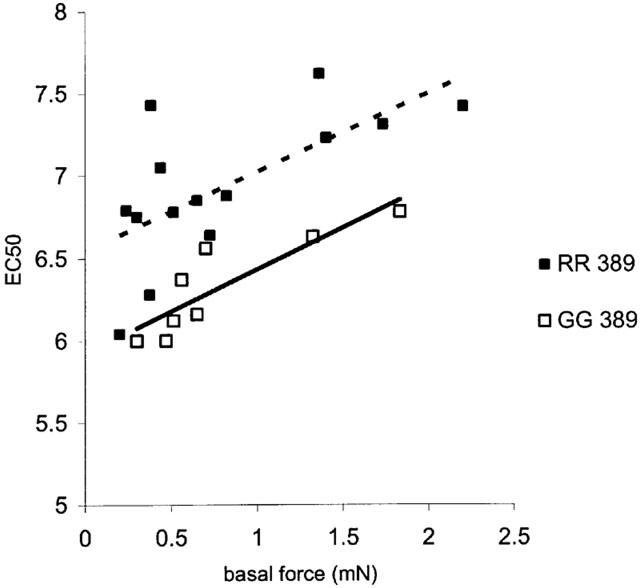

Relationship between basal force and potency for cumulative concentration responses

A linear relationship between potency and tissue basal force was evident for both variants (Figure 2). However, the regression lines were different for the two tissues showing that the difference in potency was present throughout the range of basal forces measured.

Figure 2.

Scattergram of EC50 versus basal tissue force. Fitted regression lines show that the difference in potency between the variants was not dependent on the initial basal tissue force (RR n=14; GG n=8).

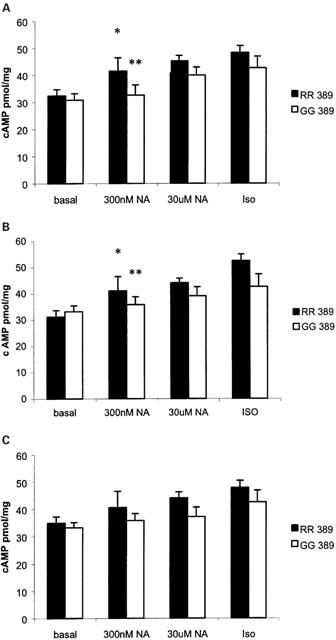

Biochemical parameters

The stimulated cyclic AMP responses were significantly greater in tissues from RR homozygous patients versus GG homozygous patients (Figure 3). This result held for the group of patients as a whole or amongst the sub groups of 49S homozygotes and patients treated with bypass grafting. In particular, there was no significant increase over basal in cyclic AMP production at the lower NA concentration for GG tissues (Figure 3). This pattern of increased cyclic AMP response to sub-maximal noradrenaline mirrored the contractile responses measured in these tissues. The Δ force, as a percentage of the maximum response to isoprenaline (0.2 mM), was 82.3±11.4% (n=7) in RR homozygotes compared with 48.3±7.7% (n=5) for GG homozygotes (P<0.05) using an intermediate concentration of 300 nM NA, with no significant differences in the response to the near maximal concentration of 30 μM NA (RR 114.7±8.5% compared to GG 105.8±14.9%, P=0.61). Despite observing a significant correlation between measured PKA and cyclic AMP levels (R=0.39, P<0.001), there was no significant difference between RR and GG homozygotes in either basal or stimulated PKA responses in all groups studied (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Catecholamine stimulated cyclic AMP levels between the two variants in all atrial myocardial tissues. RR homozygotes (basal n=12, 300 nM NA n=9, 30 μM NA n=22, ISO n=16) were significantly different by 2-way ANOVA (P=0.007) compared to GG homozygotes (basal n=5, 300 nM NA n=5, 30 μM NA n=9, ISO n=9). *P<0.05 compared to RR basal, **not significantly different compared to GG basal. Pairwise comparisons of the variants were not significant at individual concentrations. (B) Catecholamine stimulated cyclic AMP levels between the two 389 variants in tissues from 49S homozygotes only. RR homozygotes (basal n=9, 300 nM NA n=6, 30 μM NA n=15, ISO n=11) were significantly different by 2-way ANOVA (P<0.01) compared to GG homozygotes (basal n=4, 300 nM NA n=4, 30 μM NA n=7, ISO n=6). *P<0.05 compared to RR basal, **not significantly different compared to GG basal. Pairwise comparisons of the variants were not significant at individual concentrations. (C) Catecholamine stimulated cyclic AMP levels between the two 389 variants in tissues from patients undergoing bypass grafting. RR homozygotes (basal n=7, 300 nM NA n=7, 30 μM NA n=18, ISO n=14) were significantly different by 2-way ANOVA (P<0.01) compared to GG homozygotes (basal n=4, 300 nM NA n=4, 30 μM NA n=6, ISO n=6). Pairwise comparisons of the variants were not significant at individual concentrations.

Figure 4.

The calculated PKA activity ratios for atrial myocardium homozygous for 389R (RR) or 389G (GG) β1-adrenoceptor variants. The numbers of tissues are the same as those cited in Figure 3A. Using 2-way ANOVA, the two genotypes were not significantly different.

Discussion

This study demonstrates for the first time, the functional influence of the 389G>R β1-adrenoceptor variants in isolated human myocardium. Our work also highlights that atrial appendage tissue is a useful and convenient pharmacogenetic tool to study the function of native β1-adrenoceptor variants, by measuring responses to exogenous catecholamines in the presence of selective antagonists of α and β2 adrenoceptors.

Previous work using transfected cell lines suggested that the 389G>R polymorphism significantly affected the maximally stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity, but did not affect sensitivity to activation by isoprenaline (Mason et al., 1999). In contrast, our studies show that this polymorphism substantially affects tissue sensitivity to noradrenaline, but not the maximal inotropic response mediated through the receptor. There is a small but statistically significant difference between the two variants in terms of their maximum contraction to calcium, but it is not consistent across groups and its small size (<3% of maximum) must question its biological significance. Yet the difference in potency of catecholamines at β1-adrenoceptors expressed in atrial tissues from RR versus GG patients was seen consistently in both the cumulative concentration response curves and the single dose comparison studies. However, the accumulated cyclic AMP and the degree of PKA activation were limited in our studies by the absence of a PDE inhibitor in the organ bath, so that these experiments represent a net effect of receptor stimulation and degradation of cyclic AMP by PDE. The obvious disparity between the effect of the 389G>R polymorphism in transfected CHW cells and our findings reported here may lie in differences in the relative levels of expression of β1-adrenoceptor, Gs and downstream effector proteins. The multiple isoforms of both Gs protein and adenylyl cyclase vary in their tissue distribution, together with permutations in their expression, which could markedly influence coupling efficiency (Monteith et al., 1995; Wang & Brown, 2002). It may also be pertinent that the transfected cells expressed surface β1-adrenoceptors at a density 3–4 fold higher than those typically reported in human atrial tissue (Molenaar et al., 1997). Any apparent differences will also be dependent on the signalling molecule that is assayed (Whaley et al., 1994), as there is amplification of signal to biological response through these downstream effector proteins. These data highlight the critical importance of studying native receptor function wherever possible to verify the results of in vitro expression systems.

Given the study sample size the RR and GG patients were not balanced for age or gender (see Table 1). In fact, our GG patients were slightly younger, and although not statistically significant the proportion of females was not equal across the groups. Nevertheless, we think that this is unlikely to be a significant confounder, since female gender and increasing age are associated with a reduced LV function (Ileral et al., 2001; Andren et al., 1998). Hence, we would have expected these differences to increase the sensitivity to noradrenaline in GG over RR homozygous tissues, since it is well established that β-adrenoceptor function down regulates with declining LV function (Bohm et al., 1997). Despite this, we found the opposite effect with increased sensitivity amongst tissues from RR homozygotes. For the same reason, we excluded patients with angiographically proven LV dysfunction. However, it is conceivable that this failed to exclude lesser degrees of LV impairment and that this effect may have been disproportionate across the groups of patients undergoing surgery. Nevertheless, analysing just the sub group of patients undergoing CABG showed the same separation of the noradrenaline concentration response curves in the two 389G>R genotypes. A further potential confounder may have been concomitant medication, since most patients undergoing cardiac surgery are taking beta-blocker therapy. Because the chronic use of atenolol in patients has been shown to sensitize their tissue response to noradrenaline (Kaumann et al., 1989), we also analysed the concentration-response curves according to whether or not they were taking atenolol at the time of surgery. Removing those patients not treated with atenolol from the analysis failed to abolish the separation in potency of noradrenaline between the RR and GG homozygotes, although only one GG patient was not β-blocked. Hence, we cannot compare the extent to which the shift in potency between the variants compares to the shift in atrial tissue sensitivity seen with chronic β-blockade.

The less common 49G variant of the β1-adrenoceptor has been shown to increase the level of agonist promoted downregulation in transfected cells with otherwise similar agonist/antagonist binding and basal/agonist stimulated adenylyl cyclase activities (Rathz et al., 2002). As anticipated, 49G homozygotes were rare in our study (see Table 1), and it is certainly not powered to study in detail any interaction between 49G>S and 389G>R polymorphisms. Nonetheless it is interesting that the 49G>S variant did not appear to influence the difference in cyclic AMP generated for 389R homozygotes, since tissue cyclic AMP responses were the same whether the group was studied as a whole or just the homozygous 49S individuals. This aspect of the work is currently being developed further.

Despite the marked effect of 389G>R on adenylyl cyclase activity when expressed in rodent fibroblasts, and the effect on noradrenaline potency we have reported here, in vivo studies have failed to show a difference in haemodynamic responsiveness either to β1-adrenoceptor stimulation (Buscher et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2001) or chronic receptor blockade (O'shaughnessy et al., 2000). Although one recent study has reported that siblings homozygous for the 389R allele have significantly higher diastolic blood pressures and heart rates than siblings with one or two copies of the 389G allele (Bengtsson et al., 2001). Part of this discrepancy in the literature may reflect the focus of clinical studies on single β1-adrenoceptor genotypes. Population studies in future could be faced with addressing a compound β1-adrenoceptor genotype reflecting, not only the 49S>G and 389G>R variants, but one of a number of potentially functionally important polymorphisms identified within the coding region of the β1-adrenoceptor gene (Podlowski et al., 2000). It is also clear that very large sample sizes are needed to detect the small but nonetheless clinically important effects of receptor polymorphisms. A study demonstrating, for example, an effect of the 49S>G variant on resting heart rate used >1000 subjects to show that 49S homozygotes averaged just 5 beats per minute more than 49G homozygotes (Ranade et al., 2002). It seems premature, therefore, to assume that the 389G>R variant is not clinically important based on the published literature.

In summary, our results show that the β1-adrenoceptor 389G>R genotype does influence cardiomyocyte response to noradrenaline in intact human tissues in keeping with earlier expression studies in isolated fibroblasts. Whether or not there is a clinical correlate of this pharmacogenetic effect remains to be conclusively demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Jean Chadderton for collection of atrial tissue, Janet Maguire of the BHF Human Cardiovascular Research Group for her expert assistance in helping to set up the organ bath experiments and data analysis, together with the staff and patients at Papworth hospital. We would also like to thank Alberto Kaumann, Department of Physiology, University of Cambridge, for his extensive advice on design and analysis of the experiments with detailed comments on the manuscript and James Lynham for his help and advice with the cyclic AMP and PKA measurements. Dr Sandilands is supported by a clinical PhD studentship from the BHF and a fellowship from the Sackler foundation'

Abbreviations

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- LV

left ventricle

- PBA

phenoxybenzamine

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PKA

cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase

- RAA

right atrial appendage

References

- ANDREN B., LIND L., HEDENSTIERNA G., LITHELL A. LV diastolic function in a population sample of elderly men. Echo. 1998;15:433–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.1998.tb00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENGTSSON K., MELANDER O., ORHO-MELANDER M., LINDBLAD U., RANSTAM J., RASTAM L., GROOP L. Polymorphism in the β1-adrenergic receptor gene and hypertension. Circulation. 2001;104:187–190. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOHM M., FLESCH M., SCHNABEL P. Beta-adrenergic signal transduction in the failing and hypertrophied myocardium. J. Mol. Med. 1997;75:842–848. doi: 10.1007/s001090050175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORJESSON M., MAGNUSSON Y., HJALMARSON A., ANDERSSON B. A novel polymorphism in the gene coding for the beta1-adrenergic receptor associated with survival in patients with heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2000;21:1853–1858. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCHER R., BELGER H., EILMES K.J., TELLKAMP R., RADKE J., DHEIN S., HOYER P.F., MICHEL M.C., INSEL P.A., BRODDE O.E. In-vivo studies do not support a major functional role for the Gly389Arg β-1 adrenoceptor polymorphism in humans. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.A., KAUMANN A.J., BROWN M.J. Selective β-1AR blockade enhances positive inotropic responses to endogenous catecholamines mediated through β-2 AR's in human atrial myocardium. Circ. Res. 1990;61:1610–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILERAL A., KONDAPENEUI J., HLA A., SHIRAM J. Influence of age on left atrial appendage function in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Clin. Cardiology. 2001;24:39–44. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960240107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., HALL J.A., MURRAY K.J., WELLS F.C., BROWN M.J. A comparison of the effects of adrenaline and noradrenaline on human heart and the role of the β-1 and β-2 AR's in the stimulation of AC and contractile force. Eur. Heart J. 1989;10:29–37. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/10.suppl_b.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAHINI D.K., NURNBERGER J.I. A rapid and non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucl. Acid Res. 1991;19:5444. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIGGETT S.B., SHAH S.D., CRYER P.E. Human tissue adrenergic receptors are not predictive of responses to epinephrine in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:600–609. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.5.E600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAQBOOL A., HALL A.S., BALL S.G., BALMFORTH A.J. Common polymorphisms of beta1-adrenoceptor: identification and rapid screening assay. Lancet. 1999;353:897. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINSSON A., LINDWALL K., MELCHER A., HJEMDAHL P. Beta-adrenergic receptor responsiveness to isoprenaline in humans: concentration effect as compared with dose effect, evaluation and influence of autonomic reflexes. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 1989;28:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASON D.A., MOORE J.D., GREEN S.A., LIGGETT S.B. A gain-of-function polymorphism in a G-protein coupling domain of the human beta1-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:12670–12674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTEITH S.M., WANG T., BROWN M.J. Differences in transcription and translation of long and short Gsα, the stimulatory G-protein, in human atrium. Clin. Sci. 1995;89:487–495. doi: 10.1042/cs0890487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLENAAR P., SARSERO D., ARCH J.R., KELLY J., HENSON S.M., KAUMANN A.J. Effects of (−)-RO363 at human atrial beta-adrenoceptor subtypes, the human cloned beta 3-adrenoceptor and rodent intestinal beta 3-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:65–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY K.J., ENGLAND P.J., LYNHAM J.A., MILLS D., SCHMITZ-PEIFFER C., REEVES M.L. Use of a synthetic dodecapeptide (malantide) to measure the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase activity ratio in a variety of tissues. Biochem. J. 1990;267:703–708. doi: 10.1042/bj2670703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'SHAUGHNESSY K.M., FU B., DICKERSON C., THURSTON D., BROWN M.J. The gain of function variant (R389G) of the β-1 AR does not influence blood pressure or response to β-blockade in hypertensive subjects. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2000;99:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PODLOWSKI S., WENGEL K., LUTHER H., MULLER J., BRAMLAGE P., BAUMANN G., FELIX S., SPEER A., HETZER R., KOPKE K., HOEHE M., WALLUKAT G. β-1 adrenoceptor gene variations: a role in IDCM. J. Mol. Med. 2000;78:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s001090000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANADE K., JORGENSON E., H-SHEU W., PEI D., HSIUNG C.A., CHIANG F., CHEN Y.I., PRATT R., OLSHEN R.A., CURB D., COX D.R., BOTSTEIN D., RISCH N. A polymorphism in the β1 adrenergic receptor is associated with resting heart rate. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:935–942. doi: 10.1086/339621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RATHZ D.A., BROWN K.A., KRAMER L.A., LIGGETT S.B. Amino acid polymorphisms of the human β1-adrenergic receptor affect agonist-promoted trafficking. J. Cardiovascular Pharm. 2002;39:155–160. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDILANDS A.J., O'SHAUGHNESSY K.M., KAUMANN A.J., BROWN M.J.Increased inotropic potency of noradrenaline through the R389 β-1 adrenoceptor gene variant compared to G389 variant in isolated human myocardium J. Hum. Hypertens. 2001151(abstr)11223996 [Google Scholar]

- STADEL J.M., LEFKOWITZ R.J.Beta-adrenergic receptors: Identification and characterization by radioligand binding studies The beta-adrenergic receptors. The receptor series. 1991Humana Press:1–40.In Perkins, J.P. (ed.). [Google Scholar]

- WANG T., BROWN M.J. Influence of beta1-adrenoceptor blockade on the gene expression of adenylate cyclase subtypes and beta-adrenoceptor kinase in human atrium. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2002;101:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHALEY B.S., YUAN N., BIRNBAUMER L., CLARK R.B., BARBER R. Differential expression of the beta-adrenergic receptor modifies agonist stimulation of adenylyl cyclase: a quantitative evaluation. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:481–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE H.G., DISKY V., SOFOWORA G., KIM R.B., LANDAU R., SMILEY R.M., ZHOU H.H., WOODS A.J., HARRIS P., STEIN C.M. Arg389Gly beta-1 adrenoceptor polymorphism varies in frequency among different ethnic groups but does not alter the response in-vivo. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:191–197. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]