Abstract

Atropine, a classical muscarinic antagonist, has been reported previously to inhibit neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). In the present study, the action of atropine has been examined on α3β4 receptors expressed heterologously in Xenopus oocytes and native nAChRs in medial habenula neurons.

At concentrations of atropine often used to inhibit muscarinic receptors (1 μM), responses induced by near-maximal nicotine concentrations (100 μM) at negative holding potentials (−65 mV) are inhibited (14–30%) in a reversible manner in both α4 and α3 subunit-containing heteromeric nAChRs. Half-maximal effective concentrations (IC50 values) for atropine inhibition are similar for the four classes of heteromeric receptors studied (4–13 μM).

For α3β4 nAChRs in oocytes, inhibition by atropine (10 μM) is not overcome at higher concentrations of agonist, and is increased with membrane hyperpolarization. These results are consistent with non-competitive antagonism – possibly ion channel block.

At low concentrations of both nicotine (10 μM) and atropine (<10 μM), potentiation (≈25%) of α3β4 nAChR responses in oocytes is observed. The relative balance between potentiation and inhibition is dependent upon membrane potential.

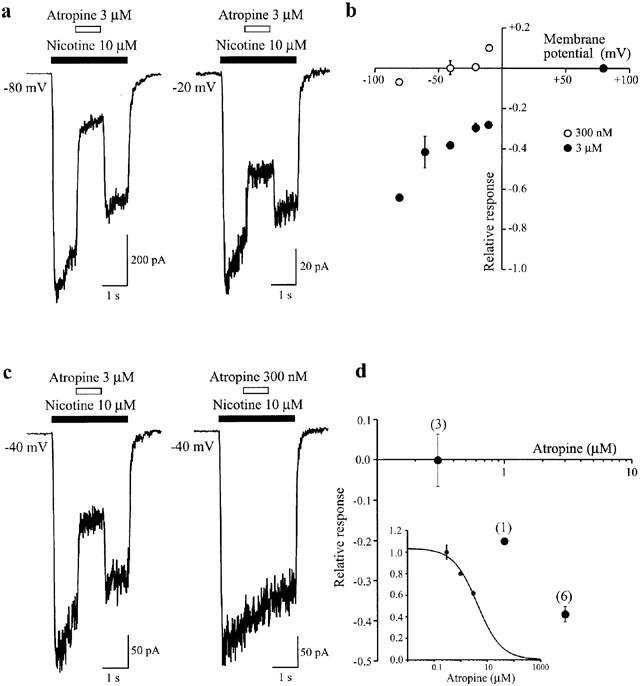

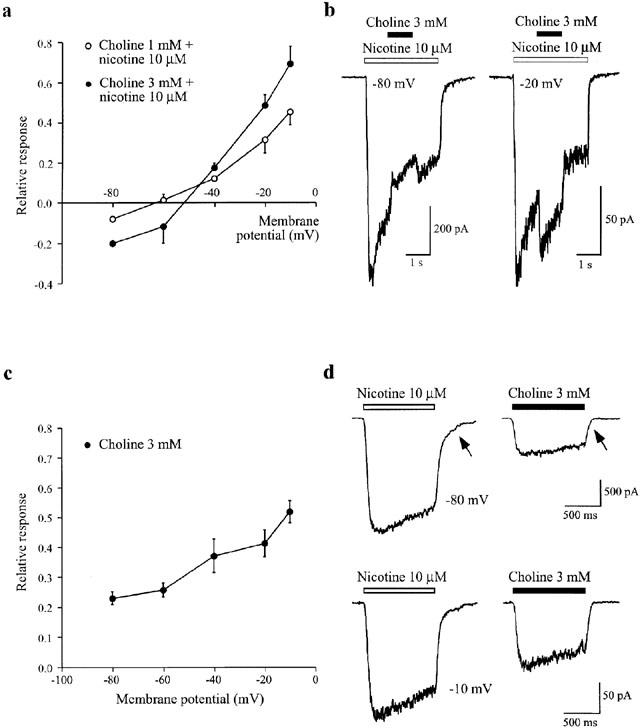

In rat medial habenula (MHb) neurons, atropine (0.3–3.0 μM) inhibited nicotine-induced responses in both a concentration and membrane potential-dependent manner (at −40 mV, IC50=4 μM), similar to the effects on α3β4–nAChRs in oocytes. However, unlike heterologously expressed receptors, potentiation was barely detectable at depolarized membrane potentials using low concentrations of nicotine (3–10 μM). Conversely, the weak agonist, choline (1–3 mM) was observed to augment responses of MHb nAChRs.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, antagonist, ligand-gated ion channel, modulation, potentiation, channel block, choline

Introduction

Within the peripheral nervous system, responses to cholinergic agents were originally categorized as either muscarinic or nicotinic (Dale, 1914); and subsequently substantiated following the purification and cloning of two distinct gene families. However, demonstration that two pharmacologically defined classes of cholinergic receptors mediated the effects of acetylcholine (ACh) in the central nervous system (CNS) proved more difficult. In particular, apparent cross interaction between ‘selective' agonists and antagonists, questioned both the specificity of these compounds and the pharmacological separation of cholinergic receptors. A consistent finding, in both spinal cord and brain, was the complete block of ACh responses by both muscarinic and nicotinic antagonists (Andersen & Curtis, 1964; Headley et al., 1975; Bird & Aghajanian, 1976; McLennan & Hicks, 1978), and moreover, the block of nicotine-induced responses by atropine (Phillis & York, 1968). Assuming specificity of the antagonists, these studies were most readily explained by a non-classical cholinergic receptor with mixed pharmacological properties. While this concept is seemingly inconsistent with most of the known cholinergic receptor genes, the newest members of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) family, encoded by the α9/α10 subunits, possess a combined nicotinic-muscarinic sensitivity (Verbitsky et al., 2000; Elgoyhen et al., 2001). However, this receptor subtype is unlikely to account for the reported widespread actions of atropine in the CNS because of its restricted anatomical distribution (Elgoyhen et al., 1994).

More information concerning the block of nicotinic responses by atropine has come from experiments on a variety of nervous system cell types. These studies suggest that the most likely mechanism of antagonism is via a non-competitive open channel block (Connor et al., 1983; Invoe & Kuriyama, 1991), with IC50 values in the low micromolar range (Barajas-Lopez et al., 2001). Thus, in retrospect, the most parsimonious explanation for the apparent unusual pharmacology of central cholinergic receptors, is an atropine-mediated channel block of nAChRs probably caused by the high concentrations of this drug present in iontophoretic pipettes. Because both central and ganglionic receptors were affected, atropine appears to be a non-selective channel blocker at both α3 and α4 subunit-containing receptors. Indeed, a recent study has confirmed that many subtypes of heterologously expressed heteromeric αβ and homomeric α nAChRs, including those that represent putative native receptors, can be inhibited by micromolar concentrations of atropine in a manner consistent with channel block (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997). α9 receptors are also inhibited by atropine in this concentration range, but the mechanism appears to be competitive (Verbitsky et al., 2000).

In addition to the inhibition, Zwart & Vijverberg (1997) suggest that atropine can also act at the ACh binding site of α4, but not α3, subunit-containing receptors to cause potentiation of currents, but only in the presence of low concentrations of ACh. At higher concentrations of ACh, atropine is competitively displaced and channel block dominates its actions. Interestingly, there have been no reports of potentiation by atropine for native nAChRs – possibly as a result of the use of high agonist concentrations in these studies. Keeping this in mind, we have re-evaluated the action of atropine on central nAChRs. Because few data are available for α3-nAChRs (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), our studies have focused on the less well-characterized putative α3β4 subunit-containing receptors, found in areas of the brain such as the medial habenula (MHb) (Mulle & Changeux, 1990; Quick et al., 1999; Sheffield et al., 2000). Parallel experiments on α3β4 receptors heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes under the same conditions have allowed us to compare the actions of atropine on similar receptors in different systems. In this regard, we have used atropine, not only to probe drug action at α3-nAChRs, but also as a pharmacological agent to further assess the potential subunit composition of central nAChRs.

Methods

Oocyte preparation and RNA expression

Oocytes were harvested from adult Xenopus laevis ovaries using protocols detailed elsewhere (Quick & Lester, 1994). Briefly, ovarian lobes were surgically removed from anaesthetized toads and digested for 2 h with collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Oocytes were maintained at 18°C in ND96-containing medium (mM) NaCl 96, KCl 2, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 5, pH 7.4) supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin and 5% horse serum. nAChR expression was achieved by microinjecting 25 ng subunit RNAs (in 1 : 1 subunit ratios), synthesized in vitro from linearized and purified plasmid templates of rat cDNA clones (Message Machine; Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, U.S.A.). Unless stated otherwise, chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Two-electrode voltage-clamp electrophysiology

Whole-cell currents were recorded from voltage-clamped oocytes 24–96 h post-injection at RT using a Geneclamp 500 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.). Electrodes were filled with 3 M KCl and electrode resistances were between 0.5–3 MΩ. Drugs were diluted (in ND96) from frozen aliquots. Agonist-mediated currents were recorded on an 80486-based PC using AxoScope software (Axon Instruments) following 50–100 Hz low-pass filtering at a digitization frequency of 200 Hz. Solutions were delivered via a gravity-fed 6-way manual valve chamber (Rainin Instruments, Woburn, MA, U.S.A.). Solution exchange considerations can be found in Fenster et al. (1997). Data analysis was performed on agonist-mediated responses that met the following criteria at holding potentials −40 to −65 mV: responses were greater than 50 nA but less than 5 μA, and responses were three times larger than the holding current.

MHB cell isolation

Neurons were isolated from the habenula region of 7–21-day-old rats using methods described previously (Quick et al., 1999). A single rat was anaesthetized under halothane and decapitated. Following removal of the brain, both habenula nuclei (with as little surrounding tissue as possible) were microdissected in ice-cold saline. Following a 30 min incubation at 37°C in a PIPES buffered solution containing 60–90 U papain (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Freehold, NJ, U.S.A.), the tissue was washed with fresh PIPES-buffer and triturated in a low glucose DMEM (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.) with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Dissociated neurons were plated onto sterile glass coverslips coated with 2–4 μg ml−1 of poly-D-lysine (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). The incubation media was supplemented with 1–2% foetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA, U.S.A.). Neurons were maintained at 37°C for at least 1 h and used up to 8 h following isolation.

Recording and drug-application in isolated cells

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from presumed MHb neurons (see Quick et al., 1999) using fire-polished, Sylgard-coated glass pipettes (no. 7052 Garner Glass Clairmont, CA, U.S.A.). Pipettes were filled with a filtered internal solution containing (in mM): Cs-methanesulphonate, 120; CsCl 20; HEPES 10; EGTA 10; Mg-ATP 5, pH 7.4). In some experiments that Mg-ATP was omitted (and CsCl was increased to 30 mM to counter the change in osmolality), in order to facilitate current detection at positive membrane potentials (see Hicks et al., 2000). Pipettes had resistances of 2–5 MΩ. Control and drug-containing solutions were gravity fed into a linear array of glass barrels (Garner Glass) positioned close (<100 μM) to the neuron. The barrels were attached to a piezo-electric bimorph (Piezo Systems, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.) connected to a variable 0–120 V DC-power source under computer control. Complete exchange of solutions occurred in ≈50 ms (Lester & Dani, 1995). Perfusion medium containing (in mM): NaCl 150; KCl 3; D-glucose 10; HEPES 10; CaCl2 2; pH 7.4. Currents induced by nicotinic agonists were recorded using an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (Axon Instruments), low-pass filtered at 500–1000 Hz, digitized at 1–2 kHz and captured on an 80486-based computer using Axobasic software (Axon Instruments).

Drugs

In both Xenopus oocyte and mammalian cell experiments drugs used were in the form of acetylcholine chloride, atropine sulphate, (−)-nicotine tartrate, and choline chloride.

Data analysis

Statistical fits to normalized data were used to determine EC50, IC50, and Hill coefficients using Kaleidagraph (Abelbeck/Synergy Software, Reading, PA, U.S.A). Concentration-response curves for activation were constructed from peak currents of nAChR responses to several agonist concentrations. The data were fit to:

where I is the peak current response to agonist, Imax is the maximum response, EC50 is the agonist concentration producing half-maximal agonist-induced responses, and n is the Hill coefficient. Concentration-response curves for inhibition were fit to the decrease in peak nicotine response during a co-application of atropine at several different concentrations. The magnitude of atropine block was calculated by dividing the response in the presence of atropine to the average of the two agonist-induced responses (in the absence of atropine) that bracketed the atropine application. These data were fit to:

where values are defined as in equation 1, and IC50 is the atropine concentration producing half-maximal agonist-induced responses. The maximum response, Imax, measured in the absence of atropine was constrained to unity for curve fitting, and maximum inhibition by atropine was assumed to be 100%.

Single exponential fits to the data were performed to evaluate the kinetics of desensitization and deactivation:

where I(t) is the current amplitude at a particular time, t, after the peak, Ip, τ is the time constant of desensitization, and ISS is the steady-state current.

Results

Non-specific inhibition of nAChRs by atropine

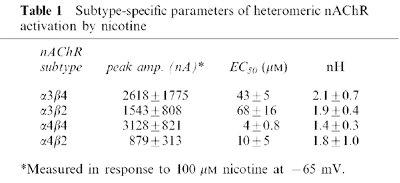

Previous studies have shown that atropine inhibits responses mediated through all subtypes of nAChR at high concentrations of agonist, while causing, in addition, selective potentiation of α4 subunit-containing receptors at low concentrations of agonist (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997). In order to compare our findings with earlier reports of the action of atropine on nAChR function, we expressed in Xenopus oocytes the predominant heteromeric-forming nAChR subunits in various pair-wise combinations (α3β4, α3β2, α4β4, α4β2), and examined their responses to brief applications (5–10 s) of nicotine. Concentration-response curves for nicotine-induced currents established that a concentration of 100 μM was higher than the EC50 value for all nAChRs (Table 1; Fenster et al., 1997), and could be used as the test concentration to assess the inhibitory effects of atropine.

Table 1.

Subtype-specific parameters of heteromeric nAChR activation by nicotine

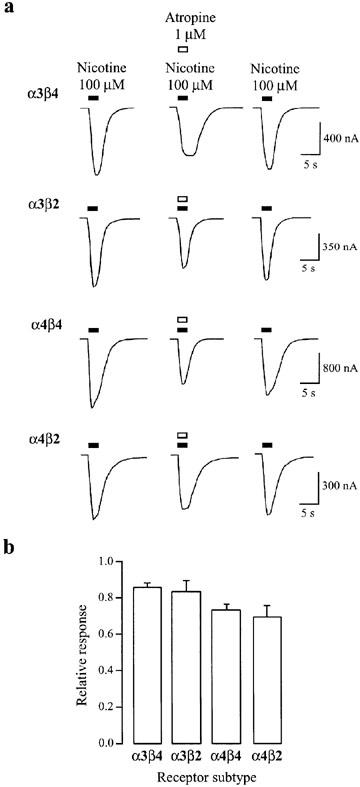

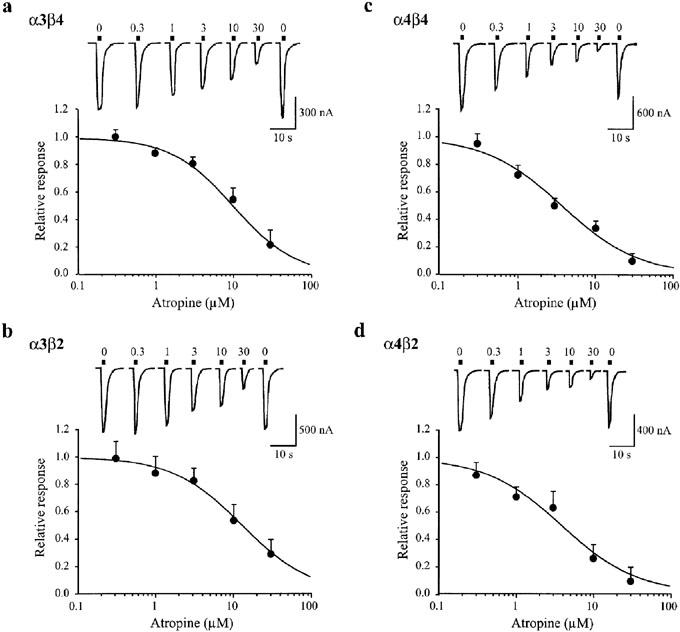

Because the inhibition of nAChRs by atropine is voltage-dependent, increasing with hyperpolarization (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), these experiments were performed at negative membrane potentials (−65 mV). Under these conditions, 1 μM atropine reduced the amplitude of nAChR-mediated currents when it was briefly co-applied with 100 μM nicotine (Figure 1A). For all subunit combinations tested, 1 μM atropine inhibited nicotine-induced currents by ≈15–30% (Figure 1B). The inhibition was reversible following washout of atropine. Our data using co-application of agonist/antagonist are similar to results from other experiments in which atropine was pre-incubated (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), implying that equilibration of the atropine block is quite rapid (see also Figure 4A). We further quantified the atropine inhibition of nicotine-induced currents for all the nAChR combinations by generating atropine inhibition concentration-response curves against 100 μM nicotine (Figure 2). The concentrations for half-maximal inhibition (IC50) by atropine at all subtypes were in the low micromolar range (Figure 2), with slightly higher values for receptors containing α3 subunits. However, the previously demonstrated high susceptibility to block of α4β4 receptor-mediated responses induced by ACh (IC50≈700 nM; Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997) was not reproduced: a finding that in part could be due to the lower efficacy of nicotine at this subtype of receptor (Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997), or because our data were obtained under pseudo steady-state conditions. Overall, our results are consistent with the suggestion that atropine exerts a relatively non-specific block of nAChRs at concentrations in the micromolar range.

Figure 1.

Reversible inhibition by atropine of heteromeric nAChR-mediated currents induced by high concentrations of nicotine. (a) Representative traces of nicotine-induced nAChR currents in the presence and absence of atropine for four different heteromeric (α3β4, α3β2, α4β4, α4β2) nAChRs expressed in oocytes. Applications of nicotine (100 μM) alone or in the presence of atropine (1 μM) are denoted, respectively, by the filled and open bars above each trace. Applications were separated by a 5 min wash in ND96. The holding potential was −65 mV. (b) Summary of experiments as performed in (a). The mean response magnitude in the presence of nicotine and atropine co-application is plotted as a fraction of the average of the two bracketed nicotine-alone-induced responses. Inhibition for all four heteromeric nAChRs is significantly different from control (P<0.05). Data are from 17–26 oocytes per condition. Error bars indicate s.e.mean.

Figure 4.

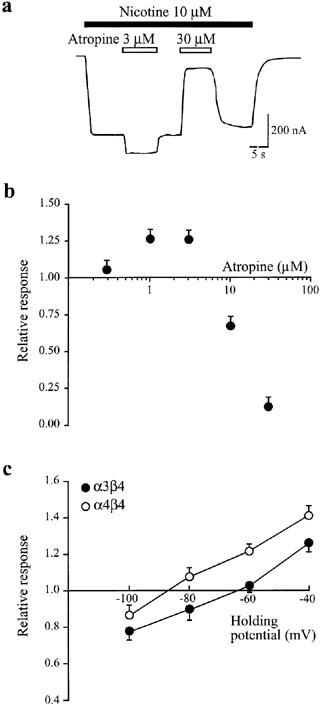

Augmentation of α3β4 receptor-mediated responses by atropine requires low concentrations of both nicotine and atropine. (a). Raw data trace showing responses to 10 μM nicotine (open bars) alone and in the presence (filled bars) of 3 μM and 30 μM atropine in α3β4 subunit expressing oocytes. The holding potential was −40 mV. (b) Summary of data as obtained in (a) at five different atropine concentrations (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 μM). The response magnitude during co-application of nicotine and atropine is calculated relative to the response induced by nicotine alone. Data are from four oocytes measured at every atropine concentration. (c) Voltage-dependence of atropine-mediated potentiation and inhibition in oocytes expressing α3β4 (filled circles) or α4β4 (open circles) nAChRs. The nicotine concentration was 10 μM; the atropine concentration was 1 μM. Responses in the presence of atropine are expressed relative to responses obtained by nicotine alone. Data are from six oocytes measured at every holding potential. Error bars indicate s.e.mean.

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent inhibition by atropine of heteromeric nAChR currents induced by high nicotine concentrations. Oocytes expressing α3β4 (a), α3β2 (b), α4β4 (c), and α4β2 (d) nAChRs were exposed to brief applications of nicotine (100 μM) alone or in the presence of various atropine concentrations (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 μM), denoted by the filled bars above each trace. Applications were separated by a 5 min wash in ND96. The holding potential was −65 mV. The response magnitude in the presence of nicotine and atropine co-application is calculated relative to the average of the two bracketed nicotine-alone-induced responses. Data are from 4–7 oocytes measured at every atropine concentration. Solid curves were generated from data fits to equation 2. Error bars indicate s.e.mean. The fitted IC50 values and Hill coefficients were 10 μM and 1.1 (α3β4), 13 μM and 1.0 (α3β2), 4 μM and 0.9 (α4β4) and 4 μM and 0.9 (α3β4).

Inhibition of heterologously expressed α3β4 receptors by atropine

While the mechanism of atropine has been well-defined for α4β4 receptors (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), much less is known about its interactions with other subtypes; in particular, why atropine does not potentiate currents induced by low concentration of agonist at α3-subunit-containing receptors (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), and, moreover, whether any of the observed actions of atropine at heterologously expressed receptors apply to native receptors. Thus we chose to perform a detailed analysis of the effects of atropine at α3β4 receptors.

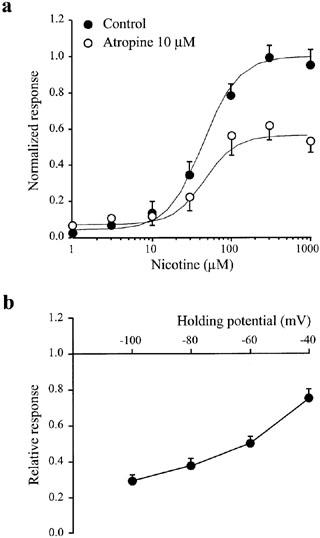

If channel block is the mechanism through which atropine inhibits α3 subunit-containing receptors then the inhibition should be insurmountable even at saturating concentrations of agonist, and in addition will most likely demonstrate a voltage-dependence. Both of these pre-requisites were fulfilled. At a holding potential of −65 mV, concentration-response curves constructed in the presence and absence of 10 μM of atropine resulted in similar concentrations of nicotine necessary for half-maximal activation (EC50=47±8 μM for control and 43±6 μM for atropine-treated oocytes), inconsistent with competitive antagonism which would have resulted in a rightward curve shift. Moreover, there was an almost two-fold decrease in the maximal current produced at saturating nicotine concentrations in the presence of 10 μM atropine, implying a non-competitive block (Figure 3A). In addition, the extent of the atropine inhibition of currents induced by 100 μM nicotine was markedly voltage-dependent, with approximately 20% inhibition at a holding potential of −40 mV and approximately 70% inhibition at a holding potential of −100 mV (Figure 3B). Although these data strongly support inhibition mediated by channel block, an increase in the rate of onset of receptor desensitization could potentially contribute to the reduction in current response, particularly in oocytes where peak responses can be underestimated by slow agonist exchange times and rapid desensitization (see Fenster et al., 1997; Papke & Thinschmidt, 1998). However, the time course of α3β4 nAChR desensitization during a 3 min exposure to a near EC50 concentration of nicotine (50 μM), as assessed from a single exponential fit, was similar in the presence (τ=179±44 s; n=4) and absence of 10 μM atropine (τ=190±56 s).

Figure 3.

Atropine-mediated inhibition of nicotine-induced α3β4 responses is non-competitive and voltage-dependent. Oocytes were injected with cRNA encoding α3β4 nAChRs. (a) Responses to various nicotine concentrations (1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 1000 μM) were elicited in the absence (filled circles) or presence (open circles) of 10 μM atropine. The holding potential was −65 mV. Data are from four oocytes measured at every nicotine concentration. The fitted parameters, Imax (normalized maximum response), n (Hill slope) and EC50 are 1, 1.8 and 39 μM, and 0.58, 1.6 and 38 μM, for curves in the absence and presence of atropine, respectively. (b) Atropine inhibition of nicotine-induced currents at various holding potentials. The nicotine concentration was 100 μM; the atropine concentration was 10 μM. Data are from four oocytes measured at every holding potential. Error bars indicate s.e.mean.

In general, our data for α3β4 receptors are comparable to the results seen with α4-containing nAChRs (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), and support the hypothesis that atropine induces a similar non-specific inhibition of all heteromeric nAChRs via a non-competitive channel blocking-like mechanism.

Atropine-induced potentiation of α3β4 nAChRs at low agonist concentrations

While inhibition predominates at high concentrations of agonist, it has been suggested that atropine can, in addition, selectively potentiate α4 subunit-containing receptors at low concentrations of agonist through a competitive mechanism (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997). However, inspection of our concentration-response curves in the range of 1–10 μM nicotine, appeared to indicate that atropine may cause some potentiation of α3β4 nAChRs (Figure 3A), implying that response augmentation may be more general than previously believed. A more detailed evaluation of atropine-mediated potentiation at α3β4 and α4β4 receptors revealed qualitative similarities but quantitative differences in their modulation by atropine. Figure 4A shows that atropine can cause rapid potentiation and inhibition of α3β4 nAChR-mediated responses induced by a low concentration of nicotine (10 μM) at slightly depolarized potentials, −40 mV. The experiments illustrated in Figure 4B, also obtained at −40 mV, indicate that the potentiation occurs over a very narrow range of atropine concentrations (0.3–3 μM), below which atropine is ineffective, and above which inhibition dominates (see also Figure 4A). Moreover, as shown in Figure 4C, the voltage-dependence of atropine modulation reveals why potentiation of α3 subunit-containing receptors was not observed previously at −80 mV (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997). Compared to α4β4 nAChRs, the potentiation-inhibition curve for α3β4 receptors is shifted by ≈20 mV to more positive membrane potentials (Figure 4C). Thus, potentiation of α3β4 receptors by 3 μM atropine is only apparent at membrane potentials more positive than ≈−60 mV. Atropine (3 μM) applied in the absence of agonist did not evoke responses at negative membrane potentials (n=3), in agreement with published studies implying that atropine is not a partial agonist at these receptors (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997). Overall, these data support the hypothesis that all heteromeric nAChRs respond to atropine similarly: potentiation can be seen at low concentrations of drug but is overcome by inhibition at higher concentrations.

Interaction of atropine with native α3β4 subunit-containing nAChRs

If the effects of atropine on heterologously expressed α3β4 receptors result from a direct pharmacological interaction, it should have a similar outcome at α3β4 nAChRs natively present on central neurons. Thus we have examined, in medial habenula (MHb) neurons, a cell type known to strongly express an α3β4-like receptor (Mulle & Changeux, 1990; Quick et al., 1999; Sheffield et al., 2000), whether atropine can induce both potentiation and inhibition of nicotine-induced responses. Under the same conditions that resulted in augmentation of α3β4 receptor-mediated responses in oocytes (10 μM nicotine; 3 μM atropine), only inhibition of responses in the MHb was observed (Figure 5). Even at very low concentrations of nicotine (EC2≈3 μM; Lester & Dani, 1995; data not shown), or at depolarized potentials (−20 mV), potentiation by atropine was not evident (Figure 5A). Conversely, inhibition was strong at 3 μM nicotine (>60% block at −80 mV), suggesting that potentiation either was completely masked by the inhibition or was absent entirely (Figure 5A). Reducing the concentration of atropine to 300 nM still resulted in inhibition (≈8%) at −80 mV, although under these conditions a small potentiation could be sometimes observed at more positive potentials (−10 mV; Figure 5B). Under the assumption that atropine induced little or no potentiation at −40 mV, an IC50 of 4 μM for atropine-induced block was estimated from the limited concentration response relationship (Figure 5C,D). Similar to the results for α3β4 receptor expressed in oocytes, when applied in the absence of nicotine, atropine (3 μM) was without effect at both negative (−40 mV) and positive potentials (+80 and +120 mV; n=2). These data imply that atropine is a more potent inhibitor of MHb nAChRs than predicted from its block of heterologously expressed α3β4 receptors, and moreover it may be considered almost a ‘pure antagonist' at these receptors.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of nAChRs in the medial habenula by atropine. Voltage and concentration-dependent block of nicotine-induced responses in MHb neurons. (a) Examples illustrating the differential magnitude of block by atropine (3 μM) during responses to nicotine (10 μM) at holding potentials of −80 and −20 mV. (b) Current-voltage relationship showing the fractional block for two different concentrations of atropine (300 nM, n=3; 3 μM, n=6). (c) Examples illustrating the differential magnitude of block by two different concentrations of atropine (3 μM and 300 nM) during responses to nicotine (10 μM) at a holding potential of −40 mV. (d) Plot showing the concentration-dependent nature of the block by atropine (n values shown in parentheses).

Activation of nAChRs on MHb cells by choline

Because the α7 selective agonist choline (Papke et al., 1996; Alkondon et al., 1997), can interact synergistically with certain heteromeric nAChRs in a manner similar, although not identical to atropine (Zwart & Vijverberg, 2000), we have assessed its effects on nAChRs in MHb cells to test whether a lack of competitive potentiation is a common feature of these channels. At negative membrane potentials (−80 mV), choline (1–3 mM) produced a consistent inhibition of responses to 10 μM nicotine, but unlike atropine, potentiated responses at more depolarized potentials (Figure 6A,B). Similar to its reported effects on both heterologously-expressed α3β4 receptors (Papke et al., 1996) and presumed α3β4 receptors in hippocampus (Alkondon et al., 1997), choline (0.3–3 mM acted as a weak agonist at MHb nAChRs (Figure 6C,D). The faster deactivation (Figure 6D, arrows) of choline-induced responses compared with nicotine activated currents is consistent with the suggestion that choline dissociates faster than nicotine, as a result of a lower affinity for the receptor. The response to choline alone, expressed relative to nicotine, also exhibits a voltage-dependence (Figure 6C), probably as a result of self-induced channel block (Zwart & Vijverberg, 2000). The threshold for activation of nAChRs by choline was ≈300 μM (data not shown). Taking the voltage-dependent block into account, the partial agonist action of choline is probably sufficient to account for the potentiation of nicotine-induced responses, e.g., at depolarized potentials (−20 mV) where channel block is minimized, the relative potentiation by choline (49±6% Figure 6A, asterisk) is very similar to the choline/nicotine ratio (41±4% Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Potentiation and inhibition of nAChRs in the medial habenula by choline. (a) Plot showing the voltage-dependence of the modulation of currents induced by nicotine (10 μM) in MHb neurons by two concentrations of co-applied choline (1 mM, n=4; 3 mM, n=6). The response in the presence of choline is expressed as a fraction of the response elicited by 10 μM nicotine alone at each membrane potential. (b) Examples illustrating inhibition and potentiation of responses to nicotine (10 μM) by choline (3 mM) at holding potentials of −80 and −20 mV, respectively. (c) Plot showing voltage-dependent activation of MHb nAChRs by choline (3 mM). Choline responses are expressed relative to nicotine (10 μM) in order to demonstrate the additional voltage-dependence attributable to choline (n=5). (d) Examples of the relative activation of nAChRs by nicotine (10 μM) and choline (3 mM) at −80 and −10 mV. Arrows indicate the faster deactivation kinetics of choline currents compared to nicotine.

Discussion

Our results provide support toward the general hypothesis that all heteromeric αβ nAChRs can be both potentiated and inhibited by atropine. The current studies extend previous findings on α4β4 receptors (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997) to α3β4 receptors, and help explain why potentiation was originally thought restricted to α4 subunit-containing channels. In addition, we find that modulation of presumed α3β4 subunit-containing nAChRs in MHb neurons does not parallel the effects of atropine on heteromeric α3β4 receptors expressed in oocytes. Specifically, atropine-mediated potentiation of responses evoked at low concentrations of agonist is essentially absent for MHb receptors – a finding possibly related to their subunit composition.

Inhibition and potentiation of heteromeric α3β4 receptors

Similar to α4β4 receptors (Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997), inhibition of α3β4 receptor-mediated response by atropine is concentration-dependent (IC50≈9 μM), voltage-dependent and non-competitive. Together, these observations suggest that the most likely mechanism of inhibition is channel block. In addition, and also similar to α4β4 receptors, under conditions of low receptor occupation by agonist (≈EC5 value of 10 μM; Fenster et al., 1997), atropine causes potentiation of nicotine-induced currents. However, there are some quantitative differences in both the voltage and concentration dependencies for α3β4 receptor-induced augmentation compared with α4β4 receptors. Thus, potentiation of α3β4 nAChRs is only observed over a narrow range of atropine concentrations (0.3–3 μM) and produces a maximal potentiation of about 25% (see Figure 4). For α4β4 receptors, augmentation is present over a wider range of concentrations (0.1–10 μM) and reaches about 75% potentiation at peak. These findings can be used to explain why, despite a higher IC50 for inhibition, the potentiation-inhibition curve for α3β4 receptors is shifted to more positive membrane potentials than for α4β4 receptors at low concentrations of atropine. Assuming that response augmentation is linear across the voltage range studied, then the extent of potentiation will determine the membrane potential at which potentiation counteracts the inhibitory effect of channel block. Thus whereas potentiation is apparent for α4β4 receptors at −80 mV, α3β4 receptors are inhibited at this membrane potential (see also Zwart & Vijverberg, 1997).

Consequences of the interaction of atropine and choline with nAChRs in the CNS

As discussed above for the oocyte-expressed heteromeric nAChRs, the net effect of atropine will be determined by a balance between the two opposing processes of atropine-induced channel block and augmentation. For presumed α3β4 subunit-containing receptors in MHb neurons, the IC50 for inhibition (4 μM) is close to that predicted from heterologously expressed α3β4 receptors (IC50=9 μM), however, potentiation is barely detectable. One explanation for this observation is that in these receptors, augmentation by atropine is not sufficient to overcome strong channel block. This interpretation is supported by the additional findings that potentiation of MHb nAChRs is readily detected for the partial agonist choline (Papke et al., 1996; Alkondon et al., 1997), which is a weaker channel blocker (see Figure 6), and that under optimized conditions, very low concentrations of atropine and depolarized membrane potentials, some potentiation may be present (see Figure 5B). Alternatively, atropine-mediated potentiation may not be intrinsic to the nAChRs in MHb. In either case, the differences between heterologously and natively expressed receptors imply that the MHb channels may not be comprised of just α3 and β4 subunits, an idea supported by additional experiments on antagonist pharmacology (Quick et al., 1999) and single cell RT–PCR (Sheffield et al., 2000).

The voltage-dependent and presumed non-competitive block of MHb nAChRs by micromolar concentrations of atropine is similar to that reported for other putative α3β4 containing receptors in, e.g., the enteric submucosal (Barajas-Lopez et al., 2001) and chromaffin cells (Invoe & Kuriyama, 1991) of the peripheral nervous system. Such non-specific inhibition of heteromeric receptors likely explains the atropine block of central receptors during the initial pharmacological characterization of nAChRs (Andersen & Curtis, 1964; Phillis & York, 1968; Headley et al., 1975; Bird & Aghajanian, 1976; McLennan & Hicks, 1978). However, with respect to the antagonism of whole cell currents in MHb cells, it is of interest to note that no evidence of fast channel block by atropine (1 μM) was found in single channel recordings (Connolly et al., 1995).

The weak action of choline alone and its potentiation of MHb nAChR-mediated responses during co-application with nicotine extend the findings that this product of ACh hydrolysis is effective at the binding sites of α3β4 type receptors (Mandelzys et al., 1995; Papke et al., 1996; Alkondon et al., 1997). Moreover, because of its presence in micromolar concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (Klein et al., 1993), choline could act as a diffuse signalling molecule mediating volume transmission (Zoli, 2000; Zwart & Vijverberg, 2000). This type of mechanism is particularly relevant to receptor activation in the MHb, because despite appropriate cholinergic input to this region (Woolf, 1991), it has not been possible to detect, as predicted, a fast nicotinic receptor-mediated synaptic response (Edwards et al., 1992), despite an abundance of nAChRs on MHb neurons (see e.g., Lester & Dani, 1995). The high density of nAChRs, coupled with partial agonist sensitivity, suggest that under certain conditions of ACh release and breakdown, MHb cells could be slightly depolarized by circulating choline, perhaps sufficient to alter their spontaneous firing rates (McCormick & Prince, 1987).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grants NIH NS31669 and DA11940.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- EC50

concentration of drug that produces a half-maximal response

- IC50

concentration of drug that produces half-maximal inhibition

- MHb

medial habenula

- nAChRs

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

References

- ALKONDON M., PEREIRA E.F., CORTES W.S., MAELICKE A., ALBUQUERQUE E.X. Choline is a selective agonist of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat brain neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:2734–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSEN P., CURTIS D.R. The pharmacology of the synaptic and acetylcholine-induced excitation of ventrobasal thalamic neurons. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1964;61:100–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARAJAS-LOPEZ C., KARANJIA R., ESPINOSA-LUNA R. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and atropine inhibit nicotinic receptors in submucosal neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;414:113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRD S.J., AGHAJANIAN G.K. The cholinergic pharmacology of hippocampal pyramidal cells: a microiontophoretic study. Neuropharmacol. 1976;15:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(76)90128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAVEZ-NORIEGA L.E., CRONA J.H., WASHBURN M.S., URRUTIA A., ELLIOTT K.J., JOHNSON E.C. Pharmacological characterization of recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors hα2β2, hα2β4, hα3β2, hα3β4, hα4β2, hα4β4 and hα7 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;280:346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOLLY J.G., GIBB A.J., COLQUHOUN D. Heterogeneity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in thin slices of rat medial habenula. J. Physiol. 1995;484:87–105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOR E.A., LEVY S.M., PARSONS R.L. Kinetic analysis of atropine-induced alterations in bullfrog ganglionic fast synaptic currents. J. Physiol. 1983;337:137–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DALE H.H. The action of certain esters and ethers of choline, and their relation to muscarine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1914;6:147–190. [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS F.A., GIBB A.J., COLQUHOUN D. ATP receptor-mediated synaptic currents in the central nervous system. Nature. 1992;359:144–147. doi: 10.1038/359144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELGOYHEN A.B., JOHNSON D.S., BOULTER J., VETTER D.E., HEINEMANN S. α9: an acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties expressed in rat cochlear hair cells. Cell. 1994;79:705–715. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELGOYHEN A.B., VETTER D.E., KATZ E., ROTHLIN C.V., HEINEMANN S.F., BOULTER J. α10: a determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FENSTER C.P., RAINS M.F., NOERAGER B., QUICK M.W., LESTER R.A.J. Influence of subunit composition on desensitization of neuronal acetylcholine receptors at low concentrations of nicotine. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5747–5759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEADLEY P.M., LODGE D., BISCOE T.J. Acetylcholine receptors on Renshaw cells of the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1975;30:252–259. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(75)90107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HICKS J.H., DANI J.A., LESTER R.A.J. Regulation of the sensitivity of acetylcholine receptors to nicotine in rat habenula neurons. J. Physiol. 2000;529:579–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INVOE M., KURIYAMA H. Properties of the nicotinic-receptor-activated current in adrenal chromaffin cells of the guinea-pig. Pflugers Archiv. 1991;419:13–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00373741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEIN J., GONZALEZ R., KOPPEN A., LOFFELHOLZ K. Free choline and choline metabolites in rat brain and body fluids: sensitive determination and implications for choline supply to the brain. Neurochem. Int. 1993;22:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(93)90058-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESTER R.A.J., DANI J.A. Acetylcholine receptor desensitization induced by nicotine in rat medial habenula neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:195–206. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANDELZYS A., DE KONINCK P., COOPER E. Agonist and toxin sensitivities of ACh-evoked currents on neurons expressing multiple nicotinic ACh receptor subunits. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1212–1221. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCORMICK D.A., PRINCE D.A. Acetylcholine causes rapid nicotinic excitation in the medial habenular nucleus of guinea pig, in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1987;7:742–752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-03-00742.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLENNAN H., HICKS T.P. Pharmacological characterization of the excitatory cholinergic receptors of rat central neurones. Neuropharmacol. 1978;17:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(78)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLE C., CHANGEUX J.P. A novel type of nicotinic receptor in the rat central nervous system characterized by patch-clamp techniques. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:169–175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00169.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPKE R.L., BENCHERIF M., LIPPIELLO P. An evaluation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation by quaternary nitrogen compounds indicates that choline is selective for the α7 subtype. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;213:201–214. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPKE R.L., THINSCHMIDT J.S. The correction of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor concentration-response relationships in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;256:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIS J.W., YORK D.H. Pharmacological studies on a cholinergic inhibition in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1968;10:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUICK M.W., LESTER H.A. Methods for expression of excitability proteins in Xenopus oocytes. Meth. Neurosci. 1994;19:261–279. [Google Scholar]

- QUICK M.W., CEBALLOS R.M., KASTEN M., MCINTOSH M.J., LESTER R.A.J. α3β4 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate function in medial habenula neurons. Neuropharmacol. 1999;38:769–783. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEFFIELD E.B., QUICK M.W., LESTER R.A.J. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNA expression and channel function in medial habenula neurons. Neuropharmacol. 2000;39:2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERBITSKY M., ROTHLIN C.V., KATZ E., ELGOYHEN A.B. Mixed nicotinic-muscarinic properties of the α9 nicotinic cholinergic receptor. Neuropharmacol. 2000;39:2515–2524. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOLF N.J. Cholinergic systems in mammalian brain and spinal cord. Prog. Neurobiol. 1991;37:475–524. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90006-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOLI M.Distribution of cholinergic neurons in the mammalian brain with special reference to their relationship with neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors Neuronal nicotinic receptors. 2000Berlin; New York: Springer; 13–30.In: Clementi F, Fornasari D, Gotti C, (eds)p [Google Scholar]

- ZWART R., VIJVERBERG H.P.M. Potentiation and inhibition of neuronal nicotonic receptors by atropine: competitive and noncompetitive effects. Molec. Pharmacol. 1997;52:886–895. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZWART R., VIJVERBERG H.P.M. Potentiation and inhibition of neuronal α4β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by choline. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;393:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]