Abstract

The macrolid FK506 is widely used in transplantation to suppress allograft rejection. FK506 and its derivatives are powerful neuroprotective molecules, but the underlying mechanisms remain to be resolved. We have previously shown that the FK506 mediated neuroprotection against oxygen radicals is independent of the inhibition of calcineurin but depends on de novo protein synthesis.

Here, we have shown that FK506 mediates protection against H2O2, UV-light or thapsigargin in neuronal cell lines, but not in non-neuronal cells such as R3T3 fibroblasts. We compared in detail the effect of FK506 on apoptotic features in PC12 cells after H2O2 with V-10,367 which binds to FKBPs but does not inhibit calcineurin. Both molecules exert the same neuroprotective effect after H2O2 stimulation. FK506, but not V-10,367, inhibited the cytochrome c release out of the mitochondria and the caspase 3 activation, while both molecules inhibited the cleavage of Poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase (Parp) and prevented the expression of p53.

FK506 and V-10,367 rapidly induced the expression of Hsp70 and Hsp27, but not Hsp90. Their neuroprotective actions could be completely blocked by quercetin, a functional inhibitor of the heat shock proteins.

We conclude that immunophilin-ligands such as FK506 and V-10,367 exert their neuroprotection independent of calcineurin through the induction of the heat shock response. The identification of the underlying signal transduction from application of immunophilin ligands to the expression of heat shock proteins represents a novel target cascade for neuroprotection.

Keywords: Apoptosis; cytochrome c; FK506; heat shock protein; neuroprotection; p53; Poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase; V-10,367

Introduction

The immunophilin ligand FK506 is widely used to prevent allograft rejection e.g. after liver and kidney transplantations. The immunosuppression is mediated by the inhibition of calcineurin in T-cells with subsequent failure of NFAT to translocate into the nucleus and to induce the transcription of IL-2 (Fruman et al., 1992). Besides transplantation, FK506 is used for the treatment of further diseases such as atopic dermatitis (Nghiem et al., 2002; Trautmann et al., 2001).

Apart from immunosuppression, FK506 exerts substantial neuroprotective properties after transient cerebral ischaemia (Sharkey & Butcher, 1994), excitotoxic insults (Dawson et al., 1993), serum withdrawal (Yardin et al., 1998), nerve fibre damage (Winter et al., 2000) or hydrogen peroxide (Klettner et al., 2001). The underlying mechanisms, however, remain to be elucidated. FK506 was supposed to mediate neuroprotection by attenuation of apoptosis e.g. by suppression of death inducing ligands (CD95-L or TRAIL) and by inhibition of the upstream c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) and c-Jun (Martin-Villalba et al., 1999; Yardin et al., 1998). Recently, we have demonstrated that the neuroprotection by FK506 is not linked to the inhibition of JNK (Klettner et al., 2001).

The immunophilin ligand V-10,367 is an FK506 analogue which lacks the calcineurin binding domain (Armistead et al., 1995). Nevertheless, its neuroregenerative and protective effects resemble that of FK506 e.g. for neurite extension in dopaminergic neurons and for neurotrophic actions in an animal model of Parkinson's disease (Costantini et al., 1998), for the accelerated regeneration of rat sciatic nerve fibres (Gold et al., 1998) and for the survival following H2O2 stimulus (Klettner et al., 2001).

Thus, we analysed the protective mechanism and compared the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 with non-calcineurin inhibitor V-10,367 regarding their influence on apoptotic features (cytochrome c release, caspase 3 activation, Poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase (Parp) cleavage and p53 expression). Furthermore, we tested whether the protective effect of FK506 and V-10,367 is dependent on the cell line or stimulus used. Because the neuroprotection by FK506 (and V-10,367) is dependent on de novo protein synthesis (Klettner et al., 2001), we have analysed putative candidate proteins such as heat shock proteins.

This study shows that FK506 and V-10,367 protect neuronal but not non-neuronal cell lines against a variety of stimuli. We demonstrated that H2O2 induces apoptotic features in PC12 cells which are inhibited by FK506, but not by its non-calcineurin inhibiting analogue V-10,367. Both substances induce a rapid induction of heat shock proteins 70 and 27 and the inhibition of this heat shock response by quercetin abolishes the neuroprotective effect of FK506 and V-10,367. The induction of heat shock proteins by already approved clinical drugs might shed light on a novel mechanism for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders (Herdegen & Gold, 2000).

Methods

Cell culture experiments

PC12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's MEM (DMEM) with Glutamax I (Life Technologies, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated horse-serum (Kraeber, Wedel, Germany), 5% heat-inactivated FCS (BioWhittaker, Heidelberg, Germany) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life technologies, U.S.A.). Neuro2A cells and R3T3 cells (CCL-131, ATCC, Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (BioWhittaker, Heidelberg, Germany) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies, U.S.A.). SHSY-5Y cells were maintained in RPMI (Life Technologies, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (BioWhittaker, Heidelberg, Germany) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies, U.S.A.).

Treatment of cells

For all experiments subconfluent cells were used. Cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2, different concentrations of thapsigargin (1, 2 or 5 μM) or 1 min UV-B/C (50 J/cm2, 312 nm). Cells were incubated with indicated concentration of FK506 and V-10,367, respectively, 30 min prior stimulus and 1 μM quercetin was given together with either FK506 or V-10,367. Control cells were treated with the appropriate vehicle in appropriate dilution.

Trypan blue exclusion assay

Cell viability was investigated by trypan blue exclusion in combination with cell counting. For cell counting, subconfluent cells were washed once with PBS, incubated for 2 min at 37° with passage EDTA (PC12) or trypsin, scraped of the culture dish, centrifuged for 10 min and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. Cells were equally diluted in trypan blue and viable cells were counted. At least four sets of independent experiments were conducted.

TUNEL-labelling

Cells treated with 200 μM H2O2 or 1 min UV-light were fixated in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After fixation, TUNEL components from Roche were used according to manufacturer's instruction with terminal dUTP-transferase (TdT) in a final concentration of 200 units ml−1 and visualization by peroxidase reaction with Vector SG chromogen.

Mitochondria preparation

To investigate cytochrome c release, a mitochondria preparation was performed. Treated cells were washed twice with PBS and harvested. All following steps were conducted at 4°C. Cells were washed and resuspended in sucrose buffer in mM: HEPES 20, KCl 10, MgCl2 1.5, EGTA 1, EDTA 1, sucrose 250, PMSF 0.1, DTT 1 and complete protease inhibitor, stored for 1 h on ice and lysed by aspiring cells through a 27 gauge syringe. Lysate was centrifuged at 750×g, supernatant collected and centrifuged at 10000×g. The pellet was washed in sucrose buffer, and resuspended in Lämmli buffer (Tris-HCl 0.0625 M, SDS 2%, Mercaptoethanol 5%, glycerol 10%, bromphenolblue 0.01%).

Whole cell lysates

Whole cell lysates were generated from subconfluent cells. The culture dish was washed once with PBS, and the cells were scraped off in 800 μl PBS. The cells were centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in DLB-buffer (Tris pH 7.4 10 mM, potassium vanadate 1 mM, SDS 1%, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). After incubation on ice, the sample was centrifuged again and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the BioRad protein assay, with BSA as standard.

Western blot

Whole cell lysate or mitochondrial lysate was separated on a 10% (Parp), 12% (p53, eIF2α, Hsp70, Hsp90) or 15% (cytochrome c, Hsp27) SDS-polyacrylamid gel and transferred onto PVDF membrane. The blot was blocked by Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween, (TTBS) and 4% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and incubated overnight at RT with antibodies against Parp (Alexis), cytochrome c (Pharmingen, U.S.A.), grp75 (Santa Cruz), β-actin (Sigma), eIF2α (Santa Cruz), Hsp72 (StressGene), Hsp27 (StressGene), Hsp90 (StressGene) or p-eIF2A (StressGene), respectively. After washing with TTBS, the blot was incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-mouse, goat-anti-rabbit or donkey-anti-goat at RT for 30 min. Following the final wash, the blot was incubated in ECL chemiluminescence reagents and the signal was detected with Amersham Hyperfilm.

Caspase 3 assay

Caspase 3 assay was performed according to the FluorAce Apopain Assay Kit (BioRad). In brief, cell medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS and harvested in apopain lysis buffer (HEPES 10 mM, EDTA 2 mM, Chaps 0.1%, DTT 5 mM, PMSF 1 mM, pepstatin A 10 μg ml−1, aprotinin 10 μg ml−1, leupeptin 20 μg ml−1). Cells were lysed by freezing and thawing four times, protein concentration was measured as described above and the lysate was stored at −80°C. One hundred and fifty μg protein were used per assay, reaction buffer and substrate (Ac-DEVD-AFC) was added. The change in fluorescence was measured at 390–400 nm excitation and 510–550 nm in emission. The increase of the signal over time was analysed and set relative to the control activity.

Statistics

All experiments were performed 3–6 times. Statistical analysis of the caspase assay and survival experiments was performed with GraphPrism software using one-way analysis of variance with repeated measures (ANOVA). Means were compared using the post-hoc Bonferroni test and significance was defined for P<0.05. Data were expressed as mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.mean).

Results

Protection of neuronal cell lines by FK506 and V-10,367 H2O2

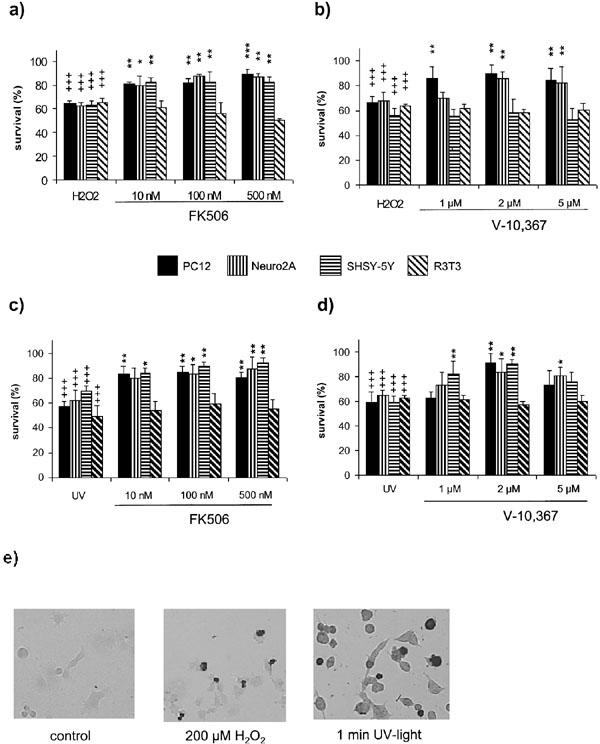

Stimulation with 200 μM H2O2 induces 35–40% cell death in all tested cell lines. FK506 (10–500 nM) protects around 80% of the otherwise dying PC12, Neuro2A and SHSY-5Y cells at all concentrations tested (Figure 1a). V-10,367 was protective at 1–5 μM for PC12 and at 2–5 μM on Neuro2A cells (previously shown), whereas the SHSY-5Y cells were not rescued (Figure 1b). The fibroblast cell line R3T3 could not be protected by either of the two substances tested (Figure 1a,b).

Figure 1.

(a–d) Immunophilin-ligand protection in different cell lines after 200 μM H2O2 (a, b) and 1 min UV-light (c, d). FK506 protects neuronal PC12, SHSY-5Y and Neuro2, but not non-neuronal R3T3 from H2O2 (a) and UV- light (c) induced cell death at the indicated concentrations. V-10,367 shows the same protection after UV-light (b), but fails to protect SHSY-5Y from H2O2 (d). (e) Induction of apoptotic cell death in PC12 by 200 μM H2O2 or 1 min UV-light indicated by TUNEL labelling. +++ gives the significance of changes compared with controls for P⩽0.001. *, ** and *** give the significances of changes by FK506 or V-10,367 compared with H2O2/UV-light treated cells for P⩽0.05, P⩽0.01 and P⩽0.001, respectively. Significances were calculated according to ANOVA and Bonferroni post test.

UV-light

Stimulation with UV-light for 1 min resulted in 35–50% cell death in all tested cell lines. Again, FK506 proved to be protective in the neuronal cell lines between 10–500 nM (Figure 1c). V-10,367 was protective in different concentrations in PC12 (2 μM), Neuro2A (2 and 5 μM) and in SHSY-5Y (1 and 2 μM) (Figure 1d). Again, R3T3 fibroblasts were not protected by either substance at any concentration used (Figure 1c,d). Similar results were obtained using a tetrazolium salt (WST-1) based colorimetric assay (data not shown).

TUNEL-labelling

Stimulation with 200 μM H2O2 or 1 min UV-light, respectively, induces TUNEL-labelling in PC12, indicating apoptotic cell death (Figure 1e).

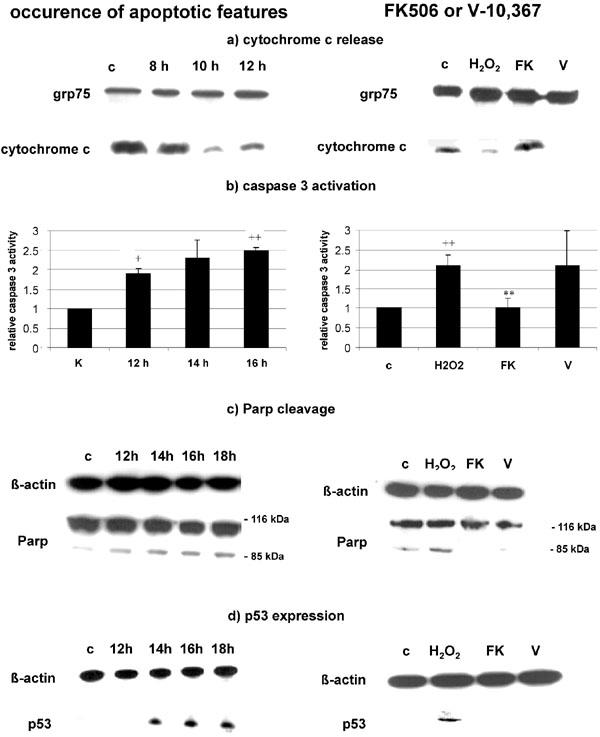

H2O2 induces apoptotic features in PC12 cells

Stimulation with 200 μM H2O2 in PC12 cells induces cytochrome c release from the mitochondria after 10 h of stimulation (Figure 2a). Somewhat later, 12–16 h after H2O2 stimulation, activation of caspase 3 could be visualized (Figure 2b). The cleavage of Parp, a nuclear substrate of caspase 3, was detectable after 14–18 h (Figure 2c), the cleavage, however, was not very prominent. Finally, the expression of the nuclear watcher-protein p53 appeared 14 h after the onset of the stimulus (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

(a) H2O2 induces cytochrome c release after 10 h of incubation (left), which is prevented by 100 nM FK506, but not by 2 μM V-10,367 (right). Expression of grp75 is shown as total protein control. (b) H2O2 induces significant caspase 3 activation after 16 h (left), which is prevented by 100 nM FK506, but not by 2 μM V-10,367 (right). (c) Parp is cleaved after 12–18 h (left), which is prevented by 100 nM FK506 and 2 μM V-10,367 (chosen timepoint 18 h) (right). (d) p53 is upregulated after 14 to 18 h post stimulus (left), which is prevented by 100 nM FK506 and 2 μM V-10,367 (chosen timepoint 18 h) (right). + and ++ give the significances of changes compared with control for P⩽0.05 and P⩽0.01 respectively and ** gives the significance of change compared with H2O2 treated cells for P⩽0.01. Significances were calculated according to ANOVA and Bonferroni post test. c=control, H2O2=treated with 200 μM H2O2, FK=additional treatment with 100 nM FK506, V=additional treatment with 2 μM V-10,367.

FK506 abolishes all apoptotic features

Prestimulation of PC12 cells with 100 nM FK506 attenuates the release of cytochrome c (after 10 h), the activation of caspase 3 (after 16 h) and the cleavage of Parp (after 18 h) (Figure 2a–c), and completely prevented the induction of p53 in PC12 cells (after 18 h) (Figure 2d). The time points were chosen regarding the appearance of the respective apoptotic features (Figure 2).

V-10,367 only attenuates Parp cleavage and p53 expression

Preincubation of PC12 cells with 2 μM V-10,367 had no effect on cytochrome c release (after 10 h) or caspase 3 activation (after 16 h) (Figure 2a,b). On the other hand, Parp cleavage (after 18 h), and p53 expression (after 18 h) were substantially reduced by V-10,367 to a similar degree as by FK506 (Figure 2c,d).

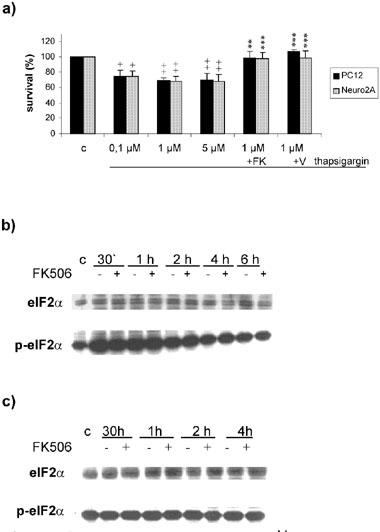

Protection is not dependent on general re-initiation of protein synthesis

We have previously shown that inhibition of the mRNA synthesis by actinomycin D antagonizes the FK506 and V-10,367 mediated protection (Klettner et al., 2001).

Besides its association to DNA, actinomycin D inhibits the dephosphorylation of the initiation factor of translation eIF2α, and in subsequence, phosphorylated eIF2α blocks the initiation of protein translation. Therefore we wanted to know whether FK506 acts through a general onset of protein translation via dephosphorylation of eIF2α. For this purpose, we investigated the potency of FK506 or V-10,367 to protect PC12 and Neuro2A cells from thapsigargin induced cell death since thapsigargin is an effective inductor of eIF2α phosphorylation. Incubation of PC12 and Neuro2A with 100 nM to 5 μM thapsigargin induced the phosphorylation of eIF2α and provoked a substantial cell death (Figure 3a,b). Preincubation with 100 nM FK506 or 2 μM V-10,367 protected PC12 and Neuro2A cells almost completely from cell death induced by 1 μM thapsigargin (Figure 3a) but FK506 did not effect the phosphorylation of eIF2α (Figure 3b). This finding excluded neuroprotection via dephosphorylation of eIF2α. For control, incubation with 200 μM H2O2 did not enhance the basal phosphorylation of eIF2α, and again, FK506 showed no effect (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Influence of FK506 and V-10,367 on thapsigargin induced cell death. Thapsigargin induces significant cell death at all concentrations used (100 nM–5 μM). Cells death induced by 1 μM thapsigargin is significantly inhibited by 100 nM FK506 and 2 μM V-10,367, respectively. (b) Phosphorylation of eIF2α after thapsigargin. 1 μM thapsigargin induces transient phosphorylation of eIF2α which is not influenced by 100 nM FK506. (c) Phosphorylation of eIF2α after H2O2. Two hundred μM H2O2 does not change the phosphorylation status of eIF2α which is not influenced by 100 nM FK506. + and ++ give the significances of changes compared with control for P⩽0.05 and P⩽0.01, respectively. ** and *** give the significances of changes compared with thapsigargin (1 μM) treated cells for P⩽0.01 and P⩽0.001, respectively. Significances were calculated according to ANOVA and Bonferroni post test. c=control, FK=100 μM FK506, V=2 μM V-10,367.

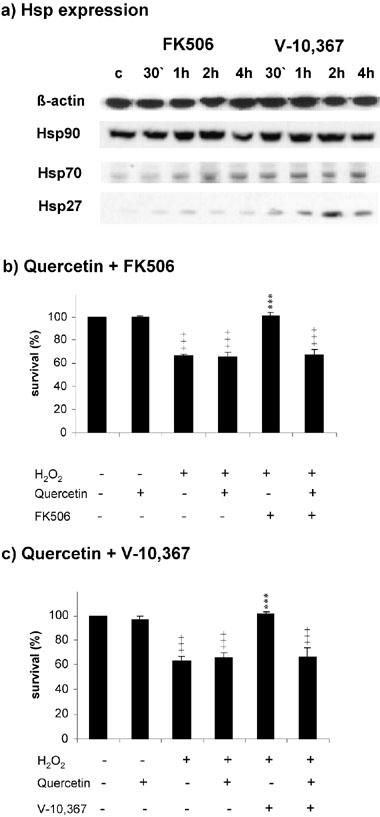

FK506 and V-10,367 protection is dependent on the induction of the heat shock response

Incubation with 100 nM FK506 or 2 μM V-10,367 induced the expression of Hsp70 and Hsp27 between 30 min and 1 h incubation which persisted at least for 4 h, the end of the observed period. In contradistinction, the expression of Hsp90 was not changed (Figure 4a). Coincubation with 1 μM quercetin, an inhibitor of the heat shock response (Hosokawa et al., 1990), completely abolished the protective effect of FK506 and V-10,367 (Figure 4b,c).

Figure 4.

(a) 100 nM FK506 and 2 μM V-10,367 induce the expression of Hsp70 and Hsp27 in PC12 after 30 min to 1 h incubation. Hsp90 is not induced. (b) Preincubation of PC12 with Hsp-inhibitor quercetin completely abolishes the protective effect of 100 nM FK506 after 200 μM H2O2. (c) Preincubation of PC12 with Hsp-inhibitor quercetin completely abolishes the protective effect of 2 μM V-10,367 after 200 μM H2O2. +++ gives the significance of change compared with control for P⩽0.001. *** gives the significance of change compared with treated cells for P⩽0.001. Significances were calculated according to ANOVA and Bonferroni post test. c=control, Q=treated with 1 μM quercetin, FK=treated with 100 μM FK506, V=treated with 2 μM V-10,367.

Discussion

FK506 provides substantial neuroprotection after various insults, e.g. cerebral ischaemia, glutamate or kainate excitotoxicity, serum withdrawal or nerve fibre injury (Dawson et al., 1993; Moriwaki et al., 1998; Sharkey & Butcher, 1994; Winter et al., 2000; Yardin et al., 1998). The underlying mechanisms, however, have not been elucidated. The supposed involvement of JNKs and c-Jun (Winter et al., 2000; Yardin et al., 1998) were recently excluded as a key mechanism of FK506 mediated neuroprotection (Klettner et al., 2001). In this study, we have investigated the action of FK506 and its non-calcineurin inhibiting analogue V-10,367 to distinguish between calcineurin dependent and independent pathways.

FK506 and V-10,367 exhibit similar neuroprotective effects

Following stimulation with H2O2 and UV-light, FK506 and V-10,367 provide a comparable rescue efficiency except for the failure of V-10,367 to protect SHSY-5Y against H2O2. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that SHSY-5Y, in contrast to PC12, do not express ubiquinon 9 (Q9), an important antioxidant that protects the inner mitochondrial membrane from lipid peroxidation (Albano et al., 2002). Fibroblasts do not profit from the protection of either substance against a broad range of stimuli; thus confirming previous reports on cell type specific actions of FK506 (Hashimoto et al., 2001; Hortelano et al., 1999; Kochi et al., 2000).

Apoptotic features after H2O2 stimulation

As previously described, we found that H2O2 induces typical apoptotic features in PC12, i.e. release of cytochrome c, activation of caspase 3, cleavage of the caspase 3 substrate Parp and expression of the watcher-protein p53 (Dumont et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2001; Yamakawa et al., 2000). The temporal occurrence of these features agrees well with mitochondria mediated apoptosis. The mere presence of these typical apoptotic features, however, does not prove their causative relevance for cell death. For example, inhibition of caspase 3 activation does not always protect cell death (Kouroku et al., 2000; Tanabe et al., 1999). Moreover, the release of cytochrome c has been regarded as a redox-defense mechanism rather than a mediator of apoptosis (Atlante et al., 2000; Ghibelli et al., 1999).

Differences between FK506 and V-10,367 reveals calcineurin independent mechanism

FK506 and V-10,367 are equally protective, but V-10,367 does not interfere with the mitochondrial death pathway (cytochrome c release or caspase 3 activation), most likely due to its failure to inhibit calcineurin. Calcineurin catalyses the dephosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bad with subsequent translocation to the mitochondria, release of cytochrome c and activation of caspase 3 (Asai et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999).

Both immunophilin-ligands impede the cleavage of Parp and the expression of p53. Parp acts as DNA-repair enzyme for the restoration of DNA strand breaks (Pieper et al., 1999) with the handicap of the energy depletion of ATP and NADP with subsequent cellular degeneration, so activated Parp is cleaved and inactivated by caspase 3 (Tewari et al., 1995). Related to the absence of Parp cleavage is the suppression of p53 since Parp mediated ribosylation of p53 extends the half life of p53, and Parp knock out mice express less p53 (Malanga et al., 1998; Wesierska-Gadek et al., 1999).

Protection does not operate via the resumption of protein synthesis

Neuroprotection of FK506 and V-10,367 can be inhibited by the actinomycin D, a potent inhibitor of mRNA-synthesis (Klettner et al., 2001). In addition, actinomycin D inhibits the dephosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α (Prostko et al., 1992). which is phosphorylated after various pathological stimuli, e.g. cerebral ischaemia. Subsequently to its phosphorylation, eIF2α inhibits the translation of proteins. The inhibition of protein synthesis has been linked with the cell death whereas the onset of translation contributes to the resistance to cell death (DeGracia et al., 1997; Sullivan et al., 1999). Here, we demonstrate that FK506 and V-10,367 protect against neuronal death by thapsigargin, an effective inductor of eIF2α phosphorylation (Prostko et al., 1992). This protection, however, does not operate via antagonization of eIF2α actions.

A novel mechanism of neuroprotection by FKBP-ligands: the induction of the heat shock response

FK506 and V-10,367 have to exert their protection downstream of or independent of cytochrome c release and caspase 3 activation. Previous studies revealed that Hsp70 realizes protection in WEHI cells irrespective of cytochrome c release and caspase 3 activation (Jaattela et al., 1998), and expression of Hsp70 renders cells less vulnerable to ischaemic cell death (Plumier et al., 1997; Yenari et al., 1998). Moreover, FK506 triggers Hsp70 expression in hepatocytes after hypoxia (Kaibori et al., 2001), Hsp70 induction by FK506 protects kidney cells from ischaemia/reperfusion injury (Yang et al., 2001) and FK506 increases Hsp70 expression in the rat brain following ischaemia (Gold, personal communication). Therefore we analysed the impact of FK506 on Hsp expression.

FK506 as well as V-10,367 induce the rapid expression of Hsp70 and Hsp27, but not of Hsp90. This fast induction links with our earlier findings of the expression of protective proteins 1 h after FK506 and V-10,367 stimulation. The FK506/V-10,367 mediated neuroprotection was completely blocked by quercetin, a well defined inhibitor of the heat shock response (Hosokawa et al., 1990) and quercetin was explicitly shown to prevent the expression of Hsp27 and Hsp70 (Hansen et al., 1997) by blockade of the heat shock element and the consequent transcription of the heat shock proteins (Li et al., 1999). Hsp27, as well as Hsp70, are lowly expressed in PC12 cells, in contrast to Hsp90, which is abundant. It is known that FK506 interacts with Hsp90 via its binding to FKBP52, and this binding is important for its neuroregenerative properties (Gold et al., 1999). It is tempting to speculate that the binding of FK506 to the Hsp90-complex might dissociate Hsp90 from the heat shock factor, thus inducing the heat shock response.

The induction of heat shock proteins might present to be a novel and powerful strategy to treat various neurogenerative disorders.

The model of FK506 mediated neuroprotection: two independent pathways

Our findings demonstrate evidence for a central role of the heat shock response in FK506/V-10,367 mediated neuroprotection. In contrast, the inhibition of apoptotic features such as cytochrome c release and caspase 3 activation (via block of calcineurin) are coincident surrogate parameters and similarly, the repression of Parp and p53 might reflect rather the interference with genetic programmes than the true nature of neuroprotection (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The neuroprotective actions of FK506 consists of a calcineurin dependent (right) and of a calcineurin independent pathway (left). In a calcineurin dependent manner, FK506 interferes with the mitochondrial death pathway, while it induces the expression of Hsp27 and Hsp70 independent of calcineurin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Annika Dorst for her excellent technical assistance, Fujisawa Pharmaceuticals Inc. for the generous gift of FK506 and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. for the generous gift of V-10,367. This work was supported by Boehringer-Ingelheim Corp. (Ingelheim, Germany) and grants from the University of Kiel and the DFG (He1561).

Abbreviations

- FKBP

FK506-binding protein

- Hsp

heat shock protein

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- Parp

Poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase

References

- ALBANO C.B., MURALIKRISHNAN D., EBADI M. Distribution of coenzyme Q homologues in brain. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:359–368. doi: 10.1023/a:1015591628503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARMISTEAD D.B.M., DEININGER D., DUFFY J., SANDERS J., LININGSTON M., MURCKO M., YAMASHITA M., NAIVA M. Design, synthesis and structure of non-macrocyclic inhibitors of FKBP12, the major binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506. Acta Crystallographica. 1995;D51:522–528. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994014502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASAI A., QIU J., NARITA Y., CHI S., SAITO N., SHINOURA N., HAMADA H., KUCHINO Y., KIRINO T. High level calcineurin activity predisposes neuronal cells to apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34450–34458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATLANTE A., CALISSANO P., BOBBA A., AZZARITI A., MARRA E., PASSARELLA S. Cytochrome c is released from mitochondria in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent fashion and can operate as a ROS scavenger and as a respiratory substrate in cerebellar neurons undergoing excitotoxic death. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37159–37166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTANTINI L.C., CHATURVEDI P., ARMISTEAD D.M., MCCAFFREY P.G., DEACON T.W., ISACSON O. A novel immunophilin ligand: distinct branching effects on dopaminergic neurons in culture and neurotrophic actions after oral administration in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 1998;5:97–106. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON T.M., STEINER J.P., DAWSON V.L., DINERMAN J.L., UHL G.R., SNYDER S.H. Immunosuppressant FK506 enhances phosphorylation of nitric oxide synthase and protects against glutamate neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:9808–9812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEGRACIA D.J., SULLIVAN J.M., NEUMAR R.W., ALOUSI S.S., HIKADE K.R., PITTMAN J.E., WHITE B.C., RAFOLS J.A., KRAUSE G.S. Effect of brain ischemia and reperfusion on the localization of phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1291–1302. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMONT A., HEHNER S.P., HOFMANN T.G., UEFFING M., DROGE W., SCHMITZ M.L. Hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis is CD95-independent, requires the release of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species and the activation of NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 1999;18:747–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRUMAN D.A., KLEE C.B., BIERER B.E., BURAKOFF S.J. Calcineurin phosphatase activity in T lymphocytes is inhibited by FK 506 and cyclosporin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3686–3690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHIBELLI L., COPPOLA S., FANELLI C., ROTILIO G., CIVITAREALE P., SCOVASSI A.I., CIRIOLO M.R. Glutathione depletion causes cytochrome c release even in the absence of cell commitment to apoptosis. FASEB J. 1999;13:2031–2036. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G., DENSMORE V., SHOU W., MATZUK M.M., GORDON H.S. Immunophilin FK506-binding protein 52 (not FK506-binding protein 12) mediates the neurotrophic action of FK506. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:1202–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G., ZELENY-POOLEY M., CHATURVEDI P., WANG M.S. Oral administration of a nonimmunosuppressant FKBP-12 ligand speeds nerve regeneration. Neuroreport. 1998;9:553–558. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEN R.K., OESTERREICH S., LEMIEUX P., SARGE K.D., FUQUA S.A. Quercetin inhibits heat shock protein induction but not heat shock factor DNA-binding in human breast carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;239:851–856. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHIMOTO Y., MATSUOKA N., KAWAKAMI A., TSUBOI M., NAKASHIMA T., EGUCHI K., TOMIOKA T., KANEMATSU T. Novel immunosuppressive effect of FK506 by augmentation of T cell apoptosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001;125:19–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERDEGEN T., GOLD B.G. Immunophilin ligands as novel treatment for neurological disorders. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2000;21:3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORTELANO S., LOPEZ-COLLAZO E., BOSCA L. Protective effect of cyclosporin A and FK506 from nitric oxide-dependent apoptosis in activated macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1139–1146. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOSOKAWA N., HIRAYOSHI K., NAKAI A., HOSOKAWA Y., MARUI N., YOSHIDA M., SAKAI T., NISHINO H., AOIKE A., KAWAI K., NAGATA K. Flavonoids inhibit the expression of heat shock proteins. Cell Struct Funct. 1990;15:393–401. doi: 10.1247/csf.15.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAATTELA M., WISSING D., KOKHOLM K., KALLUNKI T., EGEBLAD M. Hsp70 exerts its anti-apoptotic function downstream of caspase-3-like proteases. EMBO J. 1998;17:6124–6134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG D., JHA N., BOONPLUEANG R., ANDERSEN J.K. Caspase 3 inhibition attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA fragmentation but not cell death in neuronal PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 2001;76:1745–1755. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAIBORI M., INOUE T., TU W., ODA M., KWON A.H., KAMIYAMA Y., OKUMURA T. FK506, but not cyclosporin A, prevents mitochondrial dysfunction during hypoxia in rat hepatocytes. Life Sci. 2001;69:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLETTNER A., BAUMGRASS R., ZHANG Y., FISCHER G., BURGER E., HERDEGEN T., MIELKE K. The neuroprotective actions of FK506 binding protein ligands: neuronal survival is triggered by de novo RNA synthesis, but is independent of inhibition of JNK and calcineurin. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;97:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOCHI S., TAKANAGA H., MATSUO H., OHTANI H., NAITO M., TSURUO T., SAWADA Y. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci. 2000;66:2255–2260. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOUROKU Y., FUJITA E., URASE K., TSURU T., SETSUIE R., KIKUCHI T., YAGI Y., MOMOI M.Y., MOMOI T. Caspases that are activated during generation of nuclear polyglutamine aggregates are necessary for DNA fragmentation but not sufficient for cell death. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000;62:547–556. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001115)62:4<547::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI D.P., LI CALZI S., SANCHEZ E.R. Inhibition of heat shock factor activity prevents heat shock potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene expression. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999;4:223–234. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1999)004<0223:iohsfa>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALANGA M., PLESCHKE J.M., KLECZKOWSKA H.E., ALTHAUS F.R. Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11839–11843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN-VILLALBA A., HERR I., JEREMIAS I., HAHNE M., BRANDT R., VOGEL J., SCHENKEL J., HERDEGEN T., DEBATIN K.M. CD95 ligand (Fas-L/APO-1L) and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand mediate ischemia-induced apoptosis in neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:3809–3817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIWAKI A., LU Y.F., TOMIZAWA K., MATSUI H. An immunosuppressant, FK506, protects against neuronal dysfunction and death but has no effect on electrographic and behavioral activities induced by systemic kainate. Neuroscience. 1998;86:855–865. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGHIEM P., PEARSON G., LANGLEY R.G. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus: from clever prokaryotes to inhibiting calcineurin and treating atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;46:228–241. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIEPER A.A., VERMA A., ZHANG J., SNYDER S.H. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, nitric oxide and cell death. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLUMIER J.C., KRUEGER A.M., CURRIE R.W., KONTOYIANNIS D., KOLLIAS G., PAGOULATOS G.N. Transgenic mice expressing the human inducible Hsp70 have hippocampal neurons resistant to ischemic injury. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1997;2:162–167. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1997)002<0162:tmethi>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROSTKO C.R., BROSTROM M.A., MALARA E.M., BROSTROM C.O. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 2 alpha and inhibition of eIF-2B in GH3 pituitary cells by perturbants of early protein processing that induce GRP78. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16751–16754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARKEY J., BUTCHER S.P. Immunophilins mediate the neuroprotective effects of FK506 in focal cerebral ischaemia. Nature. 1994;371:336–339. doi: 10.1038/371336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN J.M., ALOUSI S.S., HIKADE K.R., BAHU N.J., RAFOLS J.A., KRAUSE G.S., WHITE B.C. Insulin induces dephosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha and restores protein synthesis in vulnerable hippocampal neurons after transient brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1010–1019. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANABE K., NAKANISHI H., MAEDA H., NISHIOKU T., HASHIMOTO K., LIOU S.Y., AKAMINE A., YAMAMOTO K. A predominant apoptotic death pathway of neuronal PC12 cells induced by activated microglia is displaced by a nonapoptotic death pathway following blockage of caspase-3-dependent cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15725–15731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEWARI M., QUAN L.T., O'ROURKE K., DESNOYERS S., ZENG Z., BEIDLER D.R., POIRIER G.G., SALVESEN G.S., DIXIT V.M. Yama/CPP32 beta, a mammalian homolog of CED-3, is a CrmA-inhibitable protease that cleaves the death substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cell. 1995;81:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUTMANN A., AKDIS M., SCHMID-GRENDELMEIER P., DISCH R., BROCKER E.B., BLASER K., AKDIS C.A. Targeting keratinocyte apoptosis in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108:839–846. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG H.G., PATHAN N., ETHELL I.M., KRAJEWSKI S., YAMAGUCHI Y., SHIBASAKI F., MCKEON F., BOBO T., FRANKE T.F., REED J.C. Ca2+-induced apoptosis through calcineurin dephosphorylation of BAD. Science. 1999;284:339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESIERSKA-GADEK J., WANG Z.Q., SCHMID G. Reduced stability of regularly spliced but not alternatively spliced p53 protein in PARP-deficient mouse fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTER C., SCHENKEL J., BURGER E., EICKMEIER C., ZIMMERMANN M., HERDEGEN T. The immunophilin ligand FK506, but not GPI-1046, protects against neuronal death and inhibits c-Jun expression in the substantia nigra pars compacta following transection of the rat medial forebrain bundle. Neuroscience. 2000;95:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAKAWA H., ITO Y., NAGANAWA T., BANNO Y., NAKASHIMA S., YOSHIMURA S., SAWADA M., NISHIMURA Y., NOZAWA Y., SAKAI N. Activation of caspase-9 and -3 during H2O2-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells independent of ceramide formation. Neurol. Res. 2000;22:556–564. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2000.11740718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG C.W., AHN H.J., HAN H.J., KIM W.Y., LI C., SHIN M.J., KIM S.K., PARK J.H., KIM Y.S., MOON I.S., BANG B.K. Pharmacological preconditioning with low-dose cyclosporine or FK506 reduces subsequent ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat kidney. Transplantation. 2001;72:1753–1759. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YARDIN C., TERRO F., LESORT M., ESCLAIRE F., HUGON J. FK506 antagonizes apoptosis and c-jun protein expression in neuronal cultures. Neuroreport. 1998;9:2077–2080. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YENARI M.A., FINK S.L., SUN G.H., CHANG L.K., PATEL M.K., KUNIS D.M., ONLEY D., HO D.Y., SAPOLSKY R.M., STEINBERG G.K. Gene therapy with HSP72 is neuroprotective in rat models of stroke and epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:584–591. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]