Abstract

To study the long-term effects of altered cannabinoid receptor activity on myocardial and vascular function, Wistar rats were treated with the selective CB1 antagonist AM-251 (0.5 mg kg−1 d−1), the potent synthetic cannabinoid HU-210 (50 μg kg−1 d−1) or vehicle for 12 weeks after coronary artery ligation or sham operation.

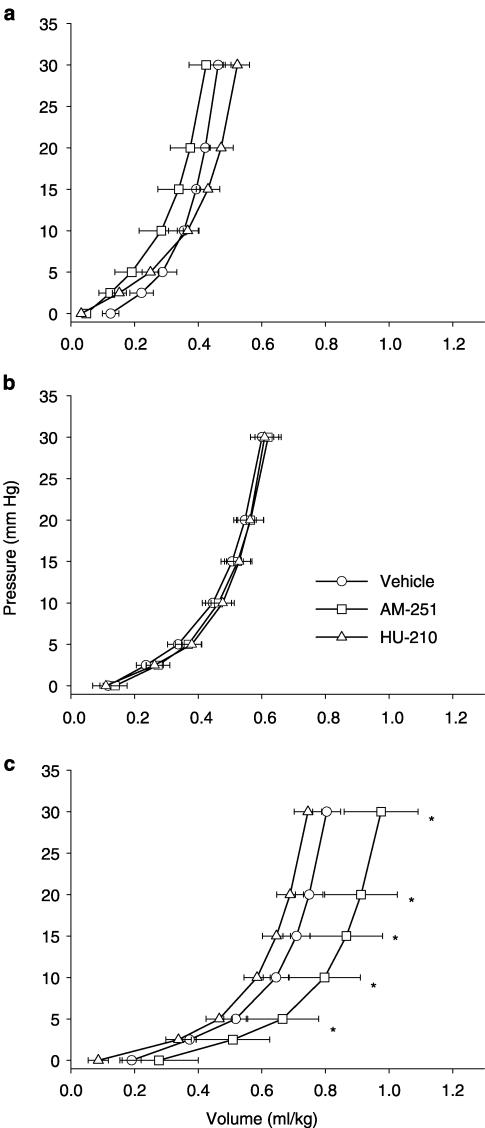

AM-251 further reduced the pressure-generating capacity, shifted the pressure volume curve to the right (P<0.05) and increased the left-ventricular operating volume (AM-251: 930±40 μl vs control: 820±40 μl vs HU-210: 790±50 μl; P<0.05) in rats with large myocardial infarction (MI).

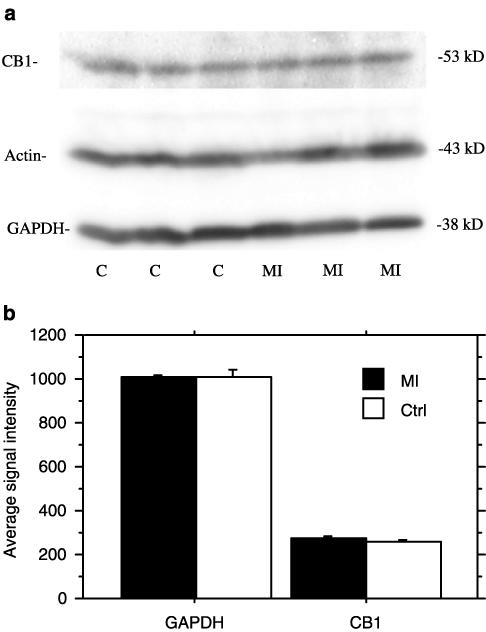

Left-ventricular CB1 immunoactivity in rats 12 weeks after large MI was unaltered as compared with noninfarcted hearts.

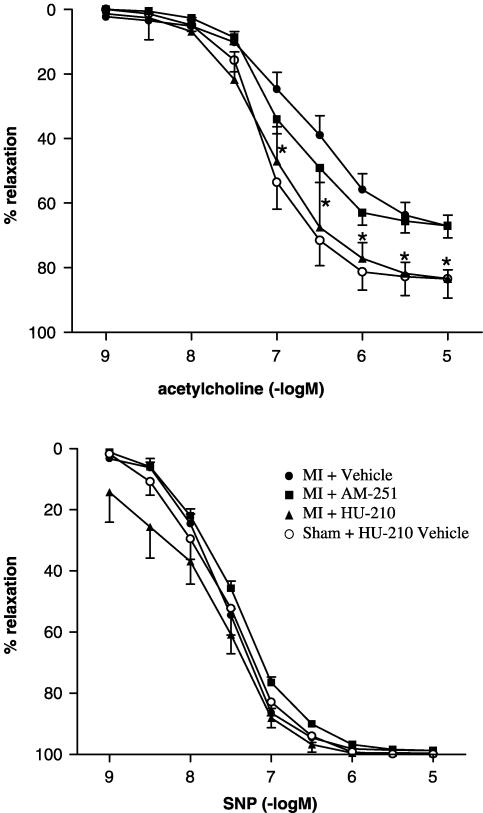

Cannabinoid receptor activation through HU-210, a cannabinoid that alters cardiovascular parameters via CB1 receptors, increased the left-ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP, P<0.05). However, it prevented the drop in left-ventricular systolic pressure (HU-210: 142±5 mm Hg; P<0.05 vs control: 124±3 mm Hg; and P<0.001 vs AM-251: 114±3 mm Hg) and prevented endothelial dysfunction (ED) in aortic rings of rats with large MI (P<0.05).

Compared with AM-251, HU-210 prevented the decline in the maximal rate of rise of left-ventricular pressure and the maximum pressure-generating ability (P<0.05). In rats with small MI, HU-210 increased cardiac index (P<0.01) and lowered the total peripheral resistance (P<0.05).

The study shows that during the development of congestive heart failure post-large MI, cannabinoid treatment increases LVEDP and prevents hypotension and ED. Presumed CB1 antagonism promotes remodeling despite unchanged myocardial CB1 expression.

Keywords: Heart failure, hemodynamics, remodeling, endothelial function, AM-251, HU-210, anandamide, cannabinoid receptors, myocardial infarction

Introduction

Endogenous cannabinoids contribute to hypotension in experimental cardiogenic shock via CB1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1). Their chronic effects during the development of cardiac dysfunction are unknown.

Cannabinoids are potent vascular modulators. The endogenous cannabinoids arachidonyl ethanolamide (anandamide) (Devane et al., 1992) and 2-arachidonyl glycerol (Mechoulam et al., 1995) bind to specific receptors and closely mimic the biological effects of plant-derived and synthetic cannabinoids. CB1 receptors (Matsuda et al., 1990) mediate most of the cardiovascular actions of cannabinoids, for review see Kunos et al. (2000).

Recently, marijuana use has been associated with myocardial infarction (MI). A case-crossover study collected data on 3882 patients with acute MI, of whom 124 (3.2%) had a history of marijuana use. Smoking marijuana seemed to be a rare trigger of acute MI with a relative risk of 3.2 in the absence of other potential triggers (Mittleman et al., 2001).

Irrespective of a possible role for marijuana in triggering MI, the consequences of cannabinoid receptor modulation after MI are not known. We have reported that endocannabinoids generated in monocytes and platelets contribute to hypotension in cardiogenic shock following coronary artery ligation in the rat. Pretreatment with a specific CB1 antagonist restored blood pressure but impaired endothelial function and increased early mortality (Wagner et al., 2001a). Activation of neurohumoral systems plays an important role in cardiac remodeling post-MI (Tsutamoto et al., 2001) and the development of congestive heart failure (Stanek et al., 2001). Remodeling is indicated by an increase in left-ventricular operating volume and a rightward shift of passive left-ventricular pressure–volume curves with increasing infarct size (Fletcher et al., 1981). Endocannabinoids share many properties of neurohumoral mediators (Klein et al., 2000), and we hypothesized that they may contribute to remodeling post-MI.

HU-210 ({-}-11-OH-Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol dimethylheptyl), a nonselective CB1/CB2 receptor agonist, is the most potent synthetic cannabinoid agonist regarding cardiovascular effects. Intravenous application elicits long-lasting bradycardia and hypotension (Lake et al., 1997). The experimental use of CB1 knockout mice proved that HU-210 alters blood pressure and heart rate via CB1 receptors (Jarai et al., 1999).

In the present study, we determined the effects of chronic CB1 antagonism/stimulation on hemodynamic variables, endothelial function and left-ventricular remodeling in rats with infarcts of various sizes.

Methods

Animals

Adult female Wistar rats were used. Coronary artery ligation was performed in a standardized model as previously described (Fletcher et al., 1981). Sham-operated rats underwent the same surgical procedure except coronary ligation.

Pharmacological interventions

In a dose-finding study, blood pressure was measured under ether anesthesia via a polyethylene catheter inserted into the right carotid artery and connected to a microtip manometer (Millar). The CB1 antagonist AM-251 (N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide) (Gatley et al., 1996), 0.5 mg kg−1 d−1 i.p. (but not 0.25 mg kg−1 d−1), prevented the peak hypotensive effect of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide, given 4 mg kg−1 intravenously (−5±10 mmHg vs −45±1 mmHg, n=3, P<0.01). AM-251 alone had no significant effects on heart rate and blood pressure.

There is no published information about the effects of chronic (>2 weeks) CB1 stimulation on cardiovascular parameters. We used HU-210 in a dose of 50 μg kg−1/d−1 i.p., 25 and 0.5 times the i.v. ED50 for its acute hypotensive and bradycardic effects, respectively (Lake et al., 1997).

Rats were housed in polyethylene cages with a 12-h light–dark cycle, fed with standard chow and water ad libitum. The three treatment groups were: (a) AM-251, 0.5 mg kg−1 d−1, in vehicle (1 vol ethanol:1 vol emulphor:18 vol saline), in 0.5 ml i.p.; (b) HU-210, 50 μg kg−1 d−1, in 1:1:18 ethanol/emulphor/saline vehicle, in 0.5 ml i.p.; and c) control rats, who received 0.5 ml vehicle (1:1:18 ethanol/emulphor/saline) i.p. every day. Treatment started 24 h after surgery and was given for 12 weeks and stopped at least 24 h prior to the hemodynamic measurements.

According to the extent of histologic infarct size, three additional subgroups in each treatment group were established: (a) rats were considered to be sham-operated if the necrotic area was <8% of the left ventricle, (b) small/moderate infarcts measured ⩽40% and (c) large infarcts >40% of the left ventricle (Pfeffer et al., 1985).

Hemodynamic studies

At 12 weeks after coronary ligation, polyethylene cannulas were inserted into the right carotid artery for pressure measurements and into the trachea for artificial ventilation. Pressures were measured through a fluid-filled PE50 tubing connected to a microtipped manometer (Millar). The carotid cannula was briefly advanced into the left ventricle and then withdrawn to the aortic arch, while pressure was recorded. Left-ventricular systolic (LVSP) and end-diastolic pressures (LVEDP), maximal rate of rise of left-ventricular systolic pressure (dP/dtmax), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) were measured under light ether anesthesia and spontaneous breathing.

Later, during positive pressure ventilation and after midsternal thoracotomy following isoflurane anesthesia, a calibrated flow probe (2.5 mm, Gould Statham) was placed around the ascending aorta for continuous measurement of aortic blood flow. Mean aortic blood flow was obtained electronically and taken as the cardiac index (CI, ml min−1 per kg body weight). Total peripheral resistance index (TPRI) was calculated as MAP/CI, stroke volume index (SVI) was calculated as CI/HR (μl per kg body weight).

The flow probe was removed and the arterial catheter was advanced into the left ventricle. The ascending aorta was occluded around the catheter by a suture to produce contractions that are isovolumetric except for coronary flow. Measurements were made of left-ventricular peak systolic and end-diastolic pressures. Maximal left-ventricular developed pressure was calculated as peak systolic minus end-diastolic pressure. These measurements defined the maximal pressure-generating ability of the left-ventricle (Fletcher et al., 1981).

Left-ventricular volume

The heart was arrested by potassium chloride and a double-lumen catheter (PE 50 inside PE 200) was inserted into the left-ventricle through the ascending aorta. The right-ventricular free wall was incised to avoid fluid accumulation. The atrioventricular groove was ligated, and isotonic saline was infused at a rate of 0.76 ml min−1 through one lumen, while intraventricular pressure was continuously recorded via the other lumen from negative pressure to 30 mmHg. Three reproducible pressure–volume curves were obtained within 10 min of cardiac arrest, well before the onset of rigor mortis. Stiffness constants were defined as described (Fletcher et al., 1981). Ventricular volumes at pressures of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30 mmHg were calculated from the pressure–volume curve (Fletcher et al., 1981). The operating left-ventricular end-diastolic volume was derived from the left-ventricular pressure–volume curve (Pfeffer et al., 1985) and was defined as the volume on the pressure–volume curve corresponding to a filling pressure equal to in vivo end-diastolic pressure.

Infarct size

As previously described (Pfeffer et al., 1985), the hearts were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and then dissected into the left ventricle plus interventricular septum and right-ventricular free wall. Transverse serial sections of 10-μm thickness were obtained in 1-mm intervals from apex to base, stained with Sirius red so that necrotic tissue stained red. Infarct size was calculated for each section by dividing the sum of the planimetered necrotic endocardial and epicardial circumferences by the sum of the total epicardial and endocardial circumferences of the left ventricle using a calibrated digitizer (Numonics Digitizer 2200).

Vascular reactivity studies

The descending thoracic aorta was dissected following removal and cleaned. Rings of 3 mm were mounted in an organ bath (Föhr Medical Instruments, Seeheim, Germany) for isometric force measurement. The rings were equilibrated for 30 min under a resting tension of 2 × g in oxygenated (95% O2; 5% CO2) Krebs–Henseleit solution containing diclofenac (1 μmol l−1). Rings were repeatedly contracted with KCl (100 m mol l−1) until reproducible responses were obtained. Thereafter, the rings were preconstricted with phenylephrine (0.3–1 μmol l−1) to 80% of maximum constriction level and the relaxant response to the cumulative application of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was assessed.

CB1 receptor immunoactivity

For Western Blot analysis of CB1, 100 mg of fresh frozen heart tissue obtained from two groups was tested: (i) viable left-ventricular myocardium without scar tissue of five untreated rats 12 weeks post-large MI (MI size: 49.5±2.7%) or (ii) myocardium of five untreated control rats. The tissue was Dounce-homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20 mmol l−1 MOPS, 150 mmol l−1 NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mmol l−1 EDTA, pH 7.0) containing the protease inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin, aprotinin (Roche, Basel), pepstatin, E-64 (trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-(4-guanidino)butane) (Roche, Basel), and p-aminobenzamidine. The homogenate was centrifuged (10 min, 14000 × g, 4°C) and the pellet was discarded. Aliquots of the supernatant were used to measure protein concentrations with a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bradford) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany). The remainder was mixed with an aliquot of × 2 Laemmli SDS-sample buffer, boiled at 95°C for 10 min and used for Western Blot analysis as described previously (Laser et al., 2000). Antibodies for the CB1 receptor (N-15) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, U.S.A. actin and GAPDH antibodies were from Chemicon, Temecula, CA, U.S.A. The chemiluminescence signal was digitally recorded with a 12-bit CCD-camera (ChemiImager 5500 from AlphaInnotech, San Leandro, CA, U.S.A.) using ChemiGlow reagent (Biozym, Hess. Oldendorf, Germany). Quantitation of the digital signal (average signal intensity) was performed with AlphaEase software from AlphaInnotec, San Leandro, CA, U.S.A. Unless otherwise stated, all materials were obtained from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Data analysis

ANOVA was used in multiple comparisons to find differences between the various infarct and treatment groups were used, and corrected by the Bonferroni test. Differences in mortality among treatment groups were determined by χ2 and Fisher's exact test. P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Drugs

AM-251 (N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide) and HU-210 ({-}-11-OH-Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol dimethylheptyl) were obtained from Biotrend. For vascular reactivity studies, phenylephrine, acetylcholine and SNP were obtained from Sigma (Germany). For Western Blot analysis, the reagents were obtained as stated above.

Results

Mortality

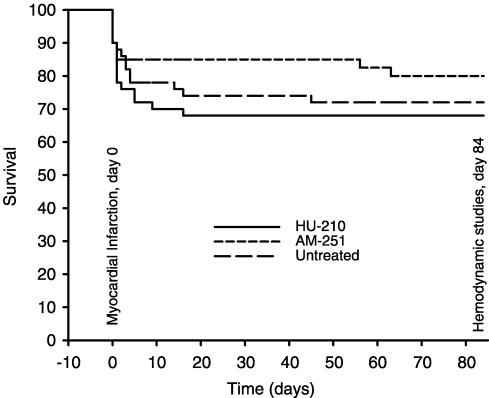

The Kaplan–Meier curve of a total of 140 rats subjected to the surgical procedure did not show significant differences among the three treatment groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival shows no significant difference for rats treated with vehicle (n=50), AM-251 (n=50) or HU-210 (n=40).

MI size, behavior, body and heart weights

Treatment with HU-210 or AM-251 did not change the extent of MI of any of the rats that underwent coronary artery ligation, as compared with respective controls (30.1±4.3% vs 36.4±3.1% vs 29.5±3.4%, respectively, P=0.31). MI sizes were similar among the treatment subgroups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Myocardial infarct size in untreated and treated rats

| Infarct size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Sham operation | Small (<40%) | Large (>40%) |

| Untreated | |||

| MI(%) | 1±1 | 28±3 | 47±1 |

| No. of rats | 10 | 12 | 13 |

| AM-251 | |||

| MI(%) | 3±2 | 31±2 | 48±1 |

| No. of rats | 4 | 12 | 15 |

| HU-210 | |||

| MI(%) | 3±1 | 26±5 | 49±2 |

| No. of rats | 7 | 7 | 10 |

Data presented are mean value ± s.e.m. MI = myocardial infarction.

Rats with infarcts treated with HU-210 gained significantly less weight than rats with infarcts treated with vehicle or AM-251 (Table 2). While AM-251 did not cause obvious side effects, HU-210-treated rats showed enhanced grooming with consequent hair loss. They were listless and anxious and some of them developed short-lasting seizures. Right-ventricular weight and lung weight increased in rats with large MI compared with sham rats throughout all treatment groups.

Table 2.

Body, heart and lung weights

| Infarct size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before operation | Sham operation | Small (<40%) | Large (>40%) | |

| BW(g) | ||||

| Untreated | 244±3 | 304±13 | 295±6 | 303±6 |

| AM-251 | 245±3 | 292±6 | 300±5 | 307±10 |

| HU-210 | 242±2 | 270±17 | 266±9†,## | 271±3# |

| LVW/BW(g kg−1) | ||||

| Untreated | 2.49±0.14 | 2.48±0.05 | 2.56±0.13 | |

| AM-251 | 2.58±0.21 | 2.53±0.08 | 2.60±0.05 | |

| HU-210 | 2.72±0.12 | 2.73±0.11 | 2.68±0.18 | |

| RVW/BW(g kg−1) | ||||

| Untreated | 0.50±0.06 | 0.80±0.07 | 1.11±0.11** | |

| AM-251 | 0.63±0.06 | 0.80±0.11 | 1.20±0.10* | |

| HU-210 | 0.54±0.05 | 0.67±0.05 | 1.23±0.11*** | |

| LungW(g) | ||||

| Untreated | 1.28±0.08 | 1.92±0.21 | 2.57±0.28** | |

| AM-251 | 1.47±0.14 | 2.19±0.29 | 3.02±0.20** | |

| HU-210 | 1.29±0.06 | 1.61±0.24 | 2.89±0.38* |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs sham-operated rats in the same treatment groups.

P<0.05 vs untreated rats with comparable infarct size.

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 HU-210 vs AM-251 rats with comparable infarct size.

Data presented are mean value ± s.e.m. BW = body weight; LVW=left-ventricular weight; RVW=right-ventricular weight; LungW = lung weight.

Hemodynamic measurements before thoracotomy

As shown in Table 3, left-ventricular systolic pressure decreased in untreated and AM-251-treated rats with large infarcts compared with sham-operated animals, but not in HU-210-treated rats. Compared to AM-251, HU-210 prevented the decline in dP/dtmax in rats with large infarcts. With growing infarct size, rats showed enhanced LVEDP in all treatment groups. HU-210 further increased LVEDP in the subgroup with large infarcts.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic Variables before Thoracotomy

| Infarct size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham operation | Small (<40%) | Large (>40%) | |

| LVSP (mmHg) | |||

| Untreated | 148±3 | 135±4 | 124±3*** |

| AM-251 | 146±19 | 133±6 | 114±3* |

| HU-210 | 148±6 | 151±9 | 142±5†,### |

| dP/dtmax (× 1000 mmHg s−1) | |||

| Untreated | 9.3±1.1 | 6.9±0.6 | 6.8±0.6* |

| AM-251 | 9.2±2.0 | 6.8±0.4 | 5.5±0.4 |

| HU-210 | 8.1±1.1 | 8.1±1.1 | 7.2±0.4# |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | |||

| Untreated | 7.9±2.0 | 17.0±4.5 | 30.7±3.0** |

| AM-251 | 8.3±1.0 | 22.7±5.1 | 31.9±2.6* |

| HU-210 | 8.2±1.9 | 18.1±3.4 | 42.4±5.5**,† |

| HR (beats min−1) | |||

| Untreated | 367±12 | 341±10 | 350±17 |

| AM-251 | 344±19 | 351±9 | 316±8 |

| HU-210 | 342±11 | 350±17 | 360±13 |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs sham-operated rats in the same treatment groups.

P<0.05 vs untreated rats with comparable infarct size.

#P<0.05, ###P<0.001 HU-210 vs AM-251 rats with comparable infarct size.

Data presented are mean value ±s.e.m. For abbreviations see extra list.

Hemodynamic measurements after thoracotomy

Table 4 shows that HU-210 increased MAP in rats with large MI. HU-210 improved CI and SVI and reduced TPRI in rats with small MI. Following aortic occlusion, the peak-developed pressure was decreased by chronic CB1 antagonism in rats with large MI.

Table 4.

Cardiac performance after thoracotomy

| Infarct size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham operation | Small (<40%) | Large (>40%) | |

| Baseline: | |||

| MAP (mmHg) | |||

| Untreated | 103±9 | 95±3 | 85±3* |

| AM-251 | 109±22 | 97±5 | 79±3 |

| HU-210 | 110±6 | 108±4 | 104±9†,## |

| HR (beats min−1) | |||

| Untreated | 353±18 | 334±11 | 334±18 |

| AM-251 | 328±23 | 354±18 | 323±9 |

| HU-210 | 357±14 | 370±15 | 354±21 |

| CI (ml min−1 kg−1) | |||

| Untreated | 218±16 | 185±18 | 176±13* |

| AM-251 | 303±59 | 182±14* | 181±12** |

| HU-210 | 325±28 | 293±17††,## | 203±19** |

| SVI (ml kg−1) | |||

| Untreated | 0.62±0.03 | 0.56±0.06 | 0.54±0.04 |

| AM-251 | 0.93±0.20 | 0.53±0.06* | 0.57±0.04* |

| HU-210 | 0.91±0.07 | 0.80±0.05†,# | 0.57±0.04** |

| TPRI (mmHg ml−1 min−1 kg−1) | |||

| Untreated | 0.47±0.01 | 0.56±0.07 | 0.50±0.03 |

| AM-251 | 0.42±0.16 | 0.55±0.04 | 0.46±0.04 |

| HU-210 | 0.36±0.05 | 0.37±0.03†,# | 0.52±0.05* |

| Aortic occlusion: | |||

| Dev Pmax (mmHg) | |||

| Untreated | 215±4 | 177±12 | 143±8*** |

| AM-251 | 236±13 | 159±12** | 115±7***,† |

| HU-210 | 218±15 | 183±9 | 146±9**,# |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs sham-operated rats in the same treatment groups.

†P<0.05, ††P<0.01 vs untreated rats with comparable infarct size.

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 HU-210 vs AM-251 rats with comparable infarct size.

Data presented are mean value ± s.e.m. Dev Pmax=maximal developed pressure; for other abbreviations see extra list.

Left-ventricular volume

As expected, a rightward shift of the pressure–volume curves was found with increasing infarct size (Figure 2). Histologic left-ventricular diameter and cavity were increased (not shown). Importantly, in rats with large infarcts, AM-251 further shifted the passive left-ventricular pressure–volume curve to the right. Stiffness constants were not different among treatment groups (not shown). Left-ventricular operating volume increased with infarct size and was significantly higher in AM-251-pretreated rats (AM-251: 930±40 μl vs untreated: 820±40 μl vs HU-210: 790±50 μl; P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Passive pressure–volume curves in sham-operated rats (a) and in rats with small (b) or large (c) MI. Vertical bars represent SEM. *P<0.05 AM-251 vs other groups.

Vascular reactivity

As indicated in Figure 3, in untreated or AM-251-treated rats with large MI, the endothelium-dependent vasodilator response of aortic rings to acetylcholine was reduced as compared with preparations from rats without MI (sham-operated). HU-210-treatment prevented endothelial dysfunction in rats with large MI. The relaxation to the endothelium-independent vasodilator SNP was unchanged in all treatment groups and independent from the existence of MI.

Figure 3.

Relaxations induced by acetylcholine (upper panel) and SNP (lower panel) in phenylephrine-preconstricted aortic rings from rats 12 weeks after large MI (filled symbols), as compared to sham-operated rats (open symbols). There was no difference among sham-operated rats treated with either AM-251, HU-210 (both not shown), or vehicle. Vertical bars represent SEM, n=6–10. *P<0.05 HU-210 vs vehicle post-large MI.

CB1 receptor immunoactivity

Left-ventricular CB1 receptor immunoactivity in rats with large MI was unaltered as compared with noninfarcted hearts (Figure 4). Statistical comparison with a Student's t-test (mean values±s.e.m) showed no differences in Western Blot signal intensity between control and infracted hearts for CB1 (259±8 and 274±11, respectively) and GAPDH (1009±32 and 1005±11, respectively) as well as for actin (data not shown). Further, chronic CB1 stimulation by daily intraperitoneally administered HU-210 (50 μg kg−1) did not diminish the hypotensive and bradycardic response to intravenously administered HU-210 (10 μg kg−1) as compared with non-pretreated controls challenged with HU-210 (−46±5 vs −49±4 mm Hg; −108±25 vs −85±19 beats min−1, respectively, data obtained 30 min after HU-210 i.v., n=5), which rules out tolerance and receptor desensitization.

Figure 4.

(a) Western Blot analysis with antibodies specific for the CB1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1), actin, and glyceraldehyde-3 phosphodehydrogenase (GAPDH). For each lane, 18 μg of protein from vital left-ventricular myocardium after sham operation (control, lanes 1–3) or 12 weeks after MI (lanes 4–6) were loaded. For additional loading control, the same blots were probed for actin and GAPDH. (b) Average Western Blot signal intensity of CB1 and GAPDH from five control (Ctrl.) and five infarcted animals (MI) were quantified as described in the Methods section. Molecular weight of the protein is shown in kilo Dalton (kD) on the right of the figure.

Discussion

The major result of this study was that chronic presumed CB1 antagonism promoted left-ventricular remodeling indicated by an increased left-ventricular volume in rats with large MI. Structural dilatation rather than a shift on the Frank–Starling curve was suggested by the rightward shift of the whole passive pressure–volume curve by CB1 receptor inhibition well beyond the effect of large MI itself. Further, CB1 receptor inhibition depressed systolic performance as indicated by reduced maximal pressure-generating capacity during aortic occlusion. These data suggest that endogenous cannabinoids prevent left-ventricular remodeling and protect systolic left-ventricular performance in rats after large MI.

In contrast, chronic CB1 receptor stimulation prevented the decline in LVSP in rats with large MI, probably indicating improved systolic performance since it was not due to systemic vasoconstriction, as shown by unaffected TPRI. However, LVEDP increased in HU-210-treated rats. These data suggest that LVSP was increased in these animals by the Frank–Starling mechanism.

The question arises as to why LVEDP was increased in rats treated with a CB1 agonist. The rats did not show an increase of fluid retention (edema, pulmonary congestion postmortem) compared with rats in other groups of same infarct size. Second, systolic performance was maintained. Third, passive left-ventricular stiffness did not differ from untreated rats. However, in vivo diastolic relaxation and filling characteristics are not available and are likely to be responsible for the elevated in vivo LVEDP in rats with large MI and chronic CB1 receptor stimulation. In general, blood pressure restoration for the price of elevated LVEDP is likely to be harmful, since beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors decrease LVEDP and improve survival (Pfeffer et al., 1985; Hu et al., 1998).

HU-210 increased CI and SVI and decreased TPRI only in rats with small infarcts (Table 4), suggesting that a potential benefit of CB1 stimulation is limited by infarct size. It has been previously shown that pharmacological treatment may cause different effects according to the timing of treatment and MI size (Pfeffer et al., 1985; Hu et al., 1998).

There is pharmacological evidence that intravenously administered cannabinoids elicit hypotension via a CB1-mediated mechanism (Lake et al, 1997; Wagner et al., 2001b; for review see Kunos et al., 2000), which has been recently confirmed through the use of CB1 knockout mice (Jarai et al., 1999; Ledent et al., 1999). However, there may be differences between the acute and chronic effects of a drug since tolerance to the cardiovascular effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the principal bioactive ingredient of marijuana, is well-known (Adams et al., 1976). In the present study, tolerance to HU-210 cannot explain the preserved blood pressure in rats with large infarcts, because tolerance would predict similar rather than opposite changes in cardiovascular parameters following treatment with a receptor antagonist. Furthermore, no appreciable tolerance to the hypotensive effect of HU-210 could be detected under the treatment protocol.

The decreased TPRI in CB1-stimulated rats with small infarcts reflects chronically reduced afterload. In noninfarcted rats, intravenous administration of 10 μg kg−1 HU-210 acutely decreased CI without affecting TPRI (Wagner et al., 2001b). Interestingly, HU-210 prevented the development of endothelial dysfunction in rats with large MI (Figure 3). Earlier findings demonstrated an active uptake mechanism for endocannabinoids into endothelial cells (Maccarone et al., 2000) and the influence of cannabinoids on vascular function, for review see Hillard (2000). Endothelial dysfunction is consistently observed in chronically infarcted rats (Bauersachs et al., 1999). In acute MI, endocannabinoid synthesis is enhanced and CB1 antagonism worsened endothelial function (Wagner et al., 2001a). Although this effect was not evident later after MI, it may have contributed to adverse remodeling. In the present study, endothelial dysfunction was defined by a reduced reaction of an isolated aortic segment to acetylcholine (Bauersachs et al., 1999). Our data suggest that this type of endothelial function in conductance vessels depends primarily on systolic performance, responsible for the flow pattern and wall stress in the ascending aorta.

CB1 receptor immunoactivity

Chronic heart failure stimulates several neurohumoral systems of which one might be endocannabinoids. CB1 receptor stimulation did not alter CB1 immunoactivity in the viable heart muscle tissue of rats with large MI (Figure 4). We report, for the first time, CB1 receptor immunoactivity in the heart post-MI, which was not different from that of sham-operated animals. However, we measured cardiac CB1 receptor expression 12 weeks post-MI, which leaves the possibility of transient CB1 upregulation in the heart.

Study limitations

First, the dose of the CB1 agonist HU-210 used in this study was high enough to cause severe side effects (Giuliani et al., 2000b). So far, HU-210 in a comparable dose had been used only for 1 week (Giuliani et al., 2000a). Second, if endocannabinoids are involved in cardioprotection in that model, one should expect clear opposite effects of control and AM-251-treated rats. CB1 antagonism promoted remodeling (Figure 2) in rats with large infarcts and significantly reduced maximal developed pressure (Table 4). However, AM-251 treatment did not have a significant effect on other hemodynamic parameters improved by HU-210, such as LVSP, MAP, dP/dtmax, CI, and TPRI, which argues against a beneficial endocannabinoid ‘tone' in this chronic model. However, the dose may have been too low. Third, peripheral CB1 receptors mediate most of the cardiovascular effects of cannabinoids (Lake et al., 1997; Wagner et al, 1997; Varga et al., 1998; Wagner et al., 2001a,2001b), but not all. For example, some effects have been attributed to activation of CB2 receptors (Lagneux & Lamontagne, 2001), Ca2+-activated potassium channels (White et al., 2001), an as-yet-unidentified ‘anandamide receptor' (Jarai et al., 1999; Wagner et al., 1999), vanilloid receptors (Zygmunt et al., 1999), conversion to vasoactive prostanoids (Grainger & Boachie-Ansah, 2001) or effects on blood vessels were sensitive to atropine or β2-adrenoceptor blockade (Gardiner et al., 2002). It is possible that HU-210 as a nonselective CB1/CB2 agonist may have achieved its effects by activating CB2 receptors. However, it is unlikely, because HU-210 acutely elicits hypotension and bradycardia via CB1 receptors (Lake et al., 1997). The use of CB1 and CB1/CB2 knock-out mice (Jarai et al., 1999; Ledent et al., 1999) could further clarify the possible role of cannabinoid receptors in hemodynamic changes following MI.

In conclusion, the results of the present study show that cannabinoid receptor agonism prevents hypotension and endothelial dysfunction but increases LVEDP post-large MI. Although myocardial CB1 expression remains unchanged, CB1 receptor antagonism has negative consequences on cardiac remodeling.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Wa 1103/2-1).

Abbreviations

- 2-AG

2-arachidonyl glycerol

- AM-251

N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide

- CI

cardiac index

- dP/dtmax

maximal rate of rise of left-ventricular systolic pressure

- ED

endothelial dysfunction

- HR

heart rate

- HU-210

{-}-11-OH-Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol dimethylheptyl

- LVEDP

left-ventricular end-diastolic pressure

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MI

myocardial infarction

- SVI

stroke volume index

- TPRI

total peripheral resistance index

References

- ADAMS M.D., CHAIT L.D., EARNHARDT J.T. Tolerance to the cardiovascular effects of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1976;56:43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb06957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUERSACHS J., BOULOUMIE A., FRACCAROLLO D., HU K., BUSSE R., ERTL G. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic myocardial infarction despite increased vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase and soluble guanylate cyclase expression: role of enhanced vascular superoxide production. Circulation. 1999;100:292–298. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVANE W.A., HANUS L., BREUER A., PERTWEE R.G., STEVENSON L.A., GRIFF C., GIBSON D., MANDELBAUM A., ETINGER A., MECHOULAM R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLETCHER P.J., PFEFFER J.M., PFEFFER M.A., BRAUNWALD E. Left-ventricular diastolic pressure–volume relations in rats with healed myocardial infarction: effects on systolic function. Circ. Res. 1981;49:618–626. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., MARCH J.E., KEMP P.A., BENNETT T. Complex regional haemodynamic effects of anandamide in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1889–1896. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GATLEY S.J., GIFFORD A.N., VOLKOW N.D., LAN R., MAKRIYANNIS A. 123I-labeled AM251: a radioiodinated ligand which binds in vivo to mouse brain cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;307:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIULIANI D., FERRARI F., OTTANI A. The cannabinoid agonist HU-210 modifies rat behavioural responses to novelty and stress. Pharmacol. Res. 2000b;41:47–53. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIULIANI D., OTTANI A., FERRARI F. Effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonist, HU-210, on ingestive behaviour and body weight of rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000a;391:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAINGER J., BOACHIE-ANSAH G. Anandamide-induced relaxation of sheep coronary arteries: the role of the vascular endothelium, arachidonic acid metabolites and potassium channels. Br. J. Pharamacol. 2001;134:1003–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLARD C.J. Endocannabinoids and vascular function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;294:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU K., GAUDRON P., ERTL G. Long-term effects of beta-adrenergic blocking agent treatment on hemodynamic function and left-ventricular remodeling in rats with experimental myocardial infarction. Importance of timing of treatment and infarct size. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998;31:692–700. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARAI Z., WAGNER J.A., VARGA K., LAKE K.D., COMPTON D.R., MARTIN B.R., ZIMMER A.M., BONNER T.I., BUCKLEY N.E., MEZEY E., RAZDAN R.K., ZIMMER A., KUNOS G. Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:14136–14141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEIN T.W., LANE B., NEWTON C.A., FRIEDMAN H. The cannabinoid system and cytokine network. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 2000;225:1–8. doi: 10.1177/153537020022500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNOS G., JARAI Z., BATKAI S., GOPARAJU S.K., ISHAC E.J.N., LIU J., WANG L., WAGNER J.A. Endocannabinoids as cardiovascular modulators. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000;108:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAGNEUX C., LAMONTAGNE D. Involvement of cannabinoids in the cardioprotection induced by lipopolysaccharide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:793–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAKE K.D., COMPTON D.R., VARGA K., MARTIN B.R., KUNOS G. Cannabinoid-induced hypotension and bradycardia in rats mediated by CB1-like cannabinoid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;281:1030–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASER M., WILLEY C.D., JIANG W., COOPER G., IV, MENOCK D.R., ZILE M.R., KUPPUSWAMY D. Integrin activation and focal complex formation in cardiac hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35624–35630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEDENT C., VALVERDE O., COSSU G., PETITET F., AUBERT J.-F., BESLOT F., BÖHME G.A., IMPERATO A., PEDRAZZINI T., ROQUES B.P., VASSART G., FRATTA W., PARMENTIER M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACCARONE M., BARI M., LORENZON T., BISOGNO T., DI MARZO V., FINAZZI-AGRO A. Anandamide uptake by human endothelial cells and its regulation by nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13484–13492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA L.A., LOLAIT S.J., BROWNSTEIN M.J., YOUNG A.C., BONNER T.I. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MECHOULAM R., BEN-SHABAT S., HANUS L., LIGUMSKY M., KAMINSKI N.E., SCHATZ A.R., GOPHER A., ALMOG S., MARTIN B.R., COMPTON D.R., PERTWEE R.G., GRIFFIN G., BAYEWITCH M., BARG J., VOGEL Z. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITTLEMAN M.A., LEWIS R.A., MACLURE M., SHERWOOD J.B., MULLER J.E. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation. 2001;103:2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEFFER J.M., PFEFFER M.A., BRAUNWALD E. Influence of chronic captopril therapy on the infarcted left ventricle of the rat. Cir. Res. 1985;57:84–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANEK B., FREY B., HULSMANN M., BERGER R., STURM B., STRAMETZ-JURANEK J., BERGLER-KLEIN J., MOSER P., BOJIC A., HARTTER E., PACHER R. Prognostic evaluation of neurohumoral plasma levels before and during beta-blocker therapy in advanced left-ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001;38:436–442. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUTAMOTO T., WADA A., MAEDA K., MABUCHI N., HAYASHI M., TSUTSUI T., OHNISHI M., SAWAKI M., FUJII M., MATSUMOTO T., MATSUI T., KINOSHITA M. Effect of spironolactone on plasma brain natriuretic peptide and left-ventricular remodeling in patients with congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001;37:1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARGA K., WAGNER J.A., BRIDGEN T.D., KUNOS G. Platelet- and macrophage-derived endogenous cannabinoids are involved in endotoxin-induced hypotension. FASEB J. 1998;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.11.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER J.A., HU K., BAUERSACHS J., KARCHER J., WIESLER M., GOPARAJU S.K., KUNOS G., ERTL G. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate hypotension after experimental myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001a;38:2048–2054. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER J.A., JARAI Z., BATKAI S., KUNOS G. Hemodynamic effects of cannabinoids: coronary and cerebral vasodilation mediated by CB1 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001b;423:203–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER J.A., VARGA K., ELLIS E.F., RZIGALINSKI B.A., MARTIN B.R., KUNOS G. Activation of peripheral CB1 cannabinoid receptors in haemorrhagic shock. Nature. 1997;390:518–521. doi: 10.1038/37371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER J.A., VARGA K., JARAI Z., KUNOS G. Mesenteric vasodilation mediated by endothelial anandamide receptors. Hypertension. 1999;33:429–434. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE R.., HO W.-S.V., BOTTRILL F.E., FORD W.R., HILEY C.R. Mechanisms of anandamide-induced vasorelaxation in rat isolated coronary arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:921–929. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT P.M., PETERSSON J., ANDERSSON J.A., CHUANG H.-H., SORGARD M., DI MARZO V., JULIUS D., HÖGESTÄTT E.D. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]