Abstract

The presence and profile of purinoceptors in neurons of the hamster submandibular ganglion (SMG) have been studied using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique.

Extracellular application of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) reversibly inhibited voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) currents (ICa) via Gi/o-protein in a voltage-dependent manner.

Extracellular application of uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), 2-methylthioATP (2-MeSATP), α,β-methylene ATP (α,β-MeATP) and adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) also inhibited ICa. The rank order of potency was ATP=UTP>ADP>2-MeSATP=α,β-MeATP.

The P2 purinoceptor antagonists, suramin and pyridoxal-5-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′, 4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS), partially antagonized the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa, while coapplication of suramin and the P1 purinoceptor antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), virtually abolished ICa inhibition. DPCPX alone partially antagonized ICa inhibition.

Suramin antagonized the UTP-induced inhibition of ICa, while DPCPX had no effect.

Extracellular application of adenosine (ADO) also inhibited ICa in a voltage-dependent manner via Gi/o-protein activation.

Mainly N- and P/Q-type VDCCs were inhibited by both ATP and ADO via Gi/o-protein βγ subunits in seemingly convergence pathways.

Keywords: Purinergic receptor, G protein-coupled receptor superfamily, parasympathetic neuron, voltage-gated calcium channels, voltage-dependent inhibition

Introduction

Extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) is known to act as a neurotransmitter in the central and peripheral nervous systems (Burnstock, 1990; Zimmermann, 1994). It has been shown that ATP can be released, or coreleased with acetylcholine or norepinephrine, from nerve endings (Burnstock, 1990) and serves as a modulator of synaptic transmission (Ribeiro, 1996). The actions of ATP are mediated by purinoceptors that are present on many neurons. The purinoceptors are classified into two major subtypes, P1 and P2, which are preferentially activated by adenosine and ATP, respectively. P2 purinoceptors have been categorized into two major groups, P2X and P2Y, based on their pharmacological properties, as well as their molecular structure. P2X are ligand-gated ion channels, while P2Y are G-protein-coupled receptors (Burnstock, 1997).

The submandibular ganglion (SMG) neuron is a parasympathetic ganglion that receives input from preganglionic cholinergic neurons, and innervates the submandibular gland to control the secretion of saliva. This ganglion also receives input from peptidergic afferent fibers and that input provides a pathway for local reflex control of saliva secretion. Salivary glands, in particularly rat and mouse parotid glands, possess P2 purinoceptors that mediate acinar cell elevation of Ca2+ and amylase secretion (McMillian et al., 1993). In sympathetic neurons, P2Y purinoceptors have also been shown to operate on presynaptic nerve terminals to inhibit the release of a neurotransmitter (Von Kügelgen et al., 1993).

Recent works have demonstrated that SMG neurons possess P2X purinoceptors (Liu & Adams, 2001; Smith et al., 2001). In addition, as we reported in our previous study, extracellular ATP caused both depolarization and hyperpolarization of SMG neurons (Suzuki et al., 1990a).

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) serve as crucial mediators of membrane excitability and Ca2+-dependent functions such as neurotransmitter release, enzyme activity and gene expression. The modulation of VDCCs is believed to be an important means of regulating Ca2+ entry and thus has a direct influence on many Ca2+-dependent processes. Several electrophysiological studies indicate that ATP modulates VDCCs currents (ICa) in frog sympathetic ganglia (Elmslie, 1992) and sinoatrial nodal cells (Qi & Kwan, 1996). The reported effects are quite variable: stimulatory, inhibitory or both. In SMG neurons, however, the effect of extracellular ATP on neuronal VDCCs has not yet been clarified. Therefore, the present study was conducted with the goals of (1) testing for a modulatory effect of extracellular ATP on VDCCs of SMG neurons, (2) determining the intracellular mechanisms in the response of extracellular ATP on VDCCs in these neurons, (3) identification of the subtype of VDCCs in the response of extracellular ATP on VDCCs in these neurons. The results indicate that both P1 and P2 purinoceptors contribute to the modulatory effect of extracellular ATP on VDCCs although adenosine only partly mimics the actions of ATP.

Methods

Cell preparation

Experiments were conducted according to international guidelines on the use of animals for experimentation. Hamster SMG neurons were acutely dissociated using a modified version of a method described previously (Yamada et al., 2002). In brief, male hamsters 4-to-6-weeks old were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg kg−1, i.p.) and SMG ganglia were isolated. SMG ganglia were maintained in Ca2+-free Krebs solution of the following composition (in mM): 136 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 MgCl2·6H2O, 10.9 glucose, 11.9 NaHCO3 and 1.1 NaH2PO4·2H2O. SMG neurons were dissociated using collagenase type I (3 mg ml−1 in Ca2+-free Krebs solution; Sigma) for 50 min at 37°C, followed by incubation in trypsin type I (1 mg ml−1 in Ca2+-free Krebs solution; Sigma) for an additional 10 min. The supernatant was replaced with normal Krebs solution of the following composition (in mM): 136 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2·6H2O, 10.9 glucose, 11.9 NaHCO3 and 1.1 NaH2PO4·2H2O. Neurons were then plated onto poly-L-lysine (Sigma)-coated glass coverslips and used within 1–12 h.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Voltage-clamp recordings were conducted using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981). Recording pipettes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution of the following composition (in mM): 100 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 BAPTA, 3.6 MgATP, 14 Tris2phosphocreatine (CP) 0.1 GTP, and 50 U ml−1 creatine phosphokinase (CPK). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The inclusion of CP and CPK helped reduce the ‘rundown' of ICa. In guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) (GDP-β-S; Sigma) experiments, GTP was replaced with 0.1 mM GDP-β-S. After the formation of a giga seal, in order to record ICa, the external solution was replaced from Krebs solution to a solution containing the following (in mM): 67 choline-Cl, 100 tetraethylammonium-Cl, 5.3 KCl, 5 CaCl2 and 10 HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with Tris base. Command voltage protocols were generated using pCLAMP (version 8; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.) and transformed to an analog signal using a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.). The command pulses were applied to cells through an L/M-EPC7 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). The currents were recorded with an L/M-EPC7 amplifier and the pCLAMP 8 acquisition system.

Materials

ATP, GDP-β-S, uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), 2-methylthioATP (2-MeSATP), α,β-methylene ATP (α,β-MeATP), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), suramin, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), pyridoxal-5-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulphonic acid (PPADS), adenosine (ADO) and nifedipine (Nif) were purchased from Sigma. Pertussis toxin (PTX) was purchased from Calbiochem. Anti-Gq/11 antibodies were purchased from Upstate biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). The anti-Gq/11 antibodies were from rabbits immunized with a synthetic peptide corresponding to the COOH-terminal sequence of the human Gq/11 subunit. ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTx GVIA) and ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-Aga IVA) were purchased from Peptide Institute. All drugs except DPCPX and Nif were dissolved in distilled water. DPCPX and Nif were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), as a stock solution at a concentration of 100 mM. All drugs were diluted to the desired final concentration in the external solution just before use. The final concentration of DMSO was <0.01%, which had no effect on the ICa.

Data analysis and statistics

All data analyses were performed using the pCLAMP 8.0 acquisition system. Values in text and figures are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was made by Student's t-test for comparisons between pairs of groups and by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's test. Probability (P) values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa

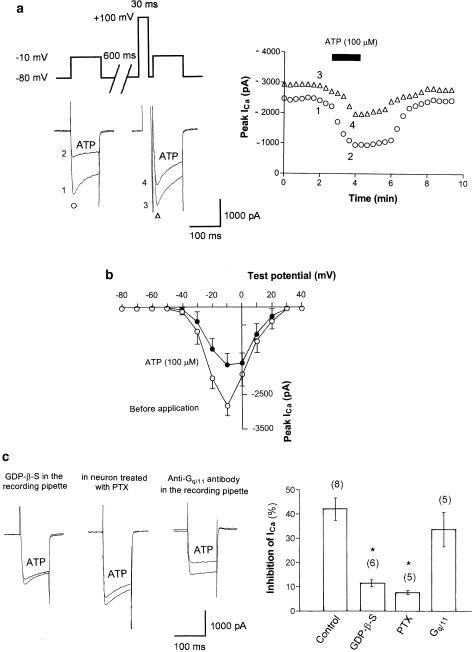

An example of ATP-induced inhibition of ICa is shown in Figure 1. To investigate the voltage dependency of inhibition of ICa by ATP, we used a double-pulse voltage protocol as shown in Figure 1a (left). In this and in subsequent descriptions, we referred to ICa before and after the strong depolarizing voltage pulse as ‘ICa (−prepulse)' and ‘ICa (+prepulse)', respectively. Application of 100 μM ATP inhibited ICa (−prepulse) from −2307.5 to −937.5 pA (59.3% inhibition) in this neuron. On the other hand, 100 μM ATP inhibited ICa (+prepulse) from −2710 to −1962.5 pA (27.5% inhibition) in the same neuron. On average, the inhibition of ICa was 42.0±4.6% for ICa (−prepulse) and 20.4±2.4% for ICa (+prepulse) (n=8). These results suggest that the application of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse attenuated the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa. Note that a strong depolarizing voltage pulse alone increased the amplitude of the ICa in these neurons (e.g. Figure 1a), suggesting that tonic inhibition (Dolphin, 1998) was present before application of the agonists to SMG neurons.

Figure 1.

Extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa. (a) Left panel: Typical superimposed ICa traces recorded using a double-pulse voltage protocol at the times indicated in the time course graph (right panel). Paired ICa were evoked from a holding potential of −80 mV by a 100 ms voltage step to −10 mV at 20 s intervals. An intervening strong depolarizing prepulse (100 mV, 30 ms) ended 5 ms prior to the second ICa activation. Right panel: typical time course of ATP-induced ICa inhibition. Opened circle and triangles in the graph indicate ICa (−prepulse) and ICa (+prepulse), respectively. ATP (100 μM) was bath applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. (b) Current–voltage relations of ICa evoked by a series of voltage steps from a holding potential of −80 mV to test pulses between −80 mV and +40 mV in +10 mV increments) in the absence (opened points) and presence (filled points) of 100 μM ATP. Values of ICa are the averages of five neurons. (c) Extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in the presence of G-protein blocker. Left panel: typical superimposed ICa traces recorded in the presence of GDP-β-S (0.1 mM for 7 min) contained in the recording pipette. Center panel: typical superimposed ICa traces in neuron treated with Gi/o-protein blocker, PTX (500 ng ml−1 for 12 h at 37°C). Right panel: typical superimposed ICa traces recorded in the presence of anti-Gq/11 antibody contained in the recording pipette (0.5 mg ml−1 for 7 min). Right graph: summary of ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in various conditions. The histogram demonstrates the degree of ICa inhibition by 100 μM ATP in control (recording pipette was filled with GTP), intracellular dialysis with GDP-β-S, after PTX and intracellular dialysis with anti-Gq/11 antibody. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested. *P<0.005 compared with control.

An example of the current–voltage relations before and after application of 100 μM ATP is shown in Figure 1b. From a holding potential of −80 mV, the ICa was activated after −40 mV with a peak current amplitude at −10 mV. ATP-induced inhibition resulted in a shift in the voltage dependence of the ICa to more positive potentials. Similar observations were made for UTP-induced inhibition of ICa mediated by expressed P2Y2 receptors in sympathetic neurons (Filippov et al., 1998).

Extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa mediated by P2Y purinoceptors

In the next series of experiments, we investigated whether or not G-protein is involved in the extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa. Experiments were performed using a recording pipette filled with an internal solution containing GDP-β-S (0.1 mM), a nonhydrolyzable analog of GDP and a competitive inhibitor of G-proteins. In each experiment, the tip of the recording pipette was filled with the standard internal solution (see above), and the pipette was then backfilled with a solution substituted for GDP-β-S. An example of the effect of 100 μM ATP on ICa recorded in the presence of GDP-β-S in the pipette solution is shown in Figure 1c (left). As summarized in Figure 1c, GDP-β-S in the pipette solution attenuated the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa. These results suggest that a G-protein is indeed involved in the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons.

G-proteins are heterotrimeric molecules with α,β and γ subunits. The α subunits can be classified into families, depending on whether they are targets for PTX (Gi/o), cholera toxin (Gs) or neither. Numerous studies demonstrated that long (12–24 h) incubations in PTX can be used to inactivate G-proteins of the Gi and Go classes. To characterize the G-protein subtypes in ATP-induced inhibition of ICa, we verified whether the effect of ATP was mediated via Gi- or Go-proteins. An example of the effect of ATP on ICa in a neuron treated with PTX (500 ng ml−1 for 12 h at 37°C) is shown in Figure 1c (centre). As summarized in Figure 1c, pretreatment of PTX attenuated the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa.

The contribution of Gq/11-proteins in the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa was next examined. Experiments were performed with pipette solutions containing anti-Gq/11 antibody. In these experiments, anti-Gq/11 antibody (1 : 50 dilution; final concentration, approximately 0.5 mg ml−1) was dissolved in the internal solution. In this experiment, the tip of the recording pipette was filled with the standard internal solution, and the pipette was then backfilled with the solution containing anti-Gq/11 antibody. An example of the effect of ATP on ICa in the presence of anti-Gq/11 antibody in the pipette solution is shown in Figure 1c (right). As summarized in Figure 1c, anti-Gq/11 antibody in the pipette solution did not attenuate the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa.

These results suggest that the Gi/o-protein is involved in the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa but not Gq/11-protein in SMG neurons. As shown in Figure 1c, with GDP-β-S and anti-Gq/11 antibody in the recording pipette, basal ICa (before application of ATP or ADO) is smaller than that under control condition (GTP in the recording pipette). In this study, applications of ATP or ADP were started 7 min after formation of the whole-cell configuration to obtain the requisite intracellular dialysis of the compounds. Therefore, it was not clear if GDP-β-S and anti-Gq/11 antibody in the recording pipette caused ‘rundown' or reduction of basal ICa. On the other hand, application of PTX did not alter the basal ICa (Figure 1c).

Pharmacological characterization of extracellular ATP-induced inhibition of ICa mediated by P2Y purinoceptors

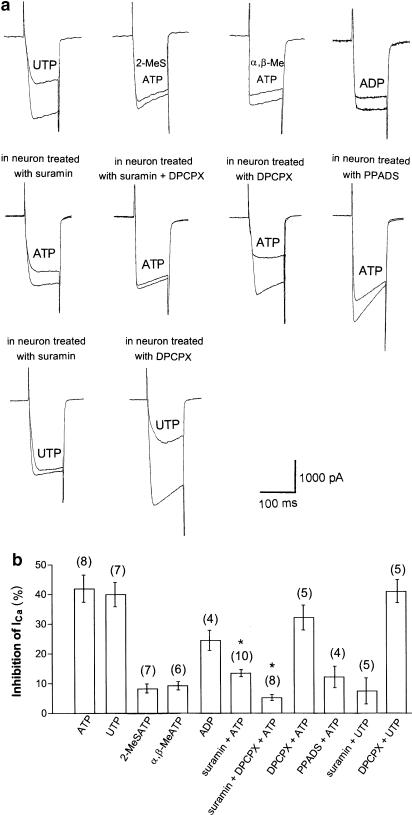

Since ATP is a nonselective purinoceptor agonist, we have further characterized the pharmacological features of the P2Y purinoceptor-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons. Application of 100 μM UTP inhibited ICa from −2447.5 to −1407.5 pA (42.2% inhibition) in this neuron (Figure 2a). Application of 100 μM 2-MeSATP also inhibited ICa from −2167.5 to −1955 pA (9.8% inhibition) in this neuron (Figure 2a). Application of 100 μM α,β-MeATP inhibited ICa from −1997.5 to −1710 pA (14.3% inhibition) in this neuron (Figure 2a). Application of 100 μM ADP inhibited ICa from −2061 to −1717.5 pA (16.6% inhibition) in this neuron (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Extracellular ATP- and ATP-analog-induced inhibition of ICa in various conditions. (a) Upper panel: typical superimposed ICa traces in the absence and presence of 100 μM UTP, 2-MeSATP, α,β-MeATP and ADP. Center panel: typical superimposed ICa traces in the absence and presence of 100 μM ATP with various antagonists. Lower panel: typical superimposed ICa traces in the absence and presence of 100 μM UTP with various antagonists. (b) Summary of ATP- and ATP-analog-induced inhibition of ICa in various conditions. The histogram demonstrates the degree of ICa inhibition by various agonists and various conditions at the concentration of 100 μM. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested. *P<0.005 compared with control.

Contribution of P1 and P2 purinoceptors to ATP-induced inhibition of ICa

To confirm whether the ATP-induced inhibitory effect was mediated by P2 purinoceptors, we used suramin which is an antagonist for the P2 purinoceptors. As shown in Figure 2a and b, a high concentration of suramin (100 μM) did not completely antagonize ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons (42.0±4.6% for ATP only and 13.5±1.2% for ATP in neuron treated with suramin, n=8 and 10, respectively). These results suggest that the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa is mediated not only by P2Y but also other receptors, possibly P1 purinoceptors in SMG neurons. Therefore, we next investigated the effects of ATP on ICa in the presence of a P1 purinoceptor antagonist, DPCPX. An example of ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in the presence of both suramin (100 μM) and DPCPX (1 μM) is shown in Figure 2a. Suramin (100 μM) and DPCPX virtually abolished ATP-induced inhibition of ICa (42.0±4.6% for ATP only and 5.3±1.0% for ATP in neuron treated with suramin+DPCPX, n=8). DPCPX alone partially antagonized ATP-induced inhibition of ICa (32.2±4.2% for ATP in neuron treated with DPCPX, n=5). PPADS also partially antagonized ATP-induced inhibition of ICa (12.2±3.6% for ATP in neuron treated with PPADS, n=4). These results indicate that both P1 and P2 purinoceptors contribute to the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons.

Furthermore, we investigated the effects of purinoceptor antagonists on UTP-induced inhibition of ICa. As shown in Figure 2a and b, suramin (100 μM) completely antagonized UTP-induced inhibition of ICa, whereas DPCPX (1 μM) failed to affect UTP-induced inhibition of ICa (40.0±4.1% for UTP only, 7.5±4.4% for UTP in neuron treated with suramin and 41.1±3.9% for UTP in neuron treated with DPCPX, n=7, 5 and 5, respectively).

Extracellular adenosine-induced inhibition of ICa

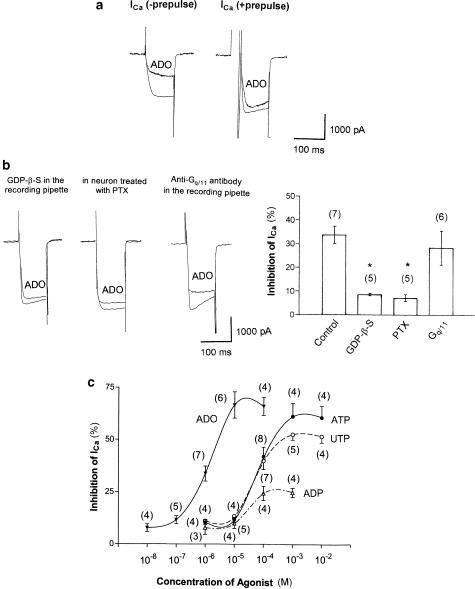

We next investigated the effects of ADO on ICa. An example of ADO-induced inhibition of ICa is shown in Figure 3a, where application of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse attenuated the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa.

Figure 3.

Extracellular ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. (a) Typical superimposed ICa traces recorded using a double-pulse voltage protocol in the absence and presence of 1 μM ADO. (b) Extracellular ADO-induced inhibition of ICa in the presence of G-protein blocker. Left panel: typical superimposed ICa traces recorded in the presence of GDP-β-S (0.1 mM for 7 min) contained in the recording pipette. Center panel: typical superimposed ICa traces in neuron treated with Gi/o-protein blocker, PTX (500 ng ml−1 for 12 h at 37°C). Right panel: typical superimposed ICa traces recorded in the presence of anti-Gq/11 antibody contained in the recording pipette (0.5 mg ml−1 for 7 min). Right graph: summary of ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in various conditions. The histogram demonstrates the degree of ICa inhibition by 100 μM ATP in control (recording pipette was filled with GTP), intracellular dialysis with GDP-β-S after PTX and intracellular dialysis with anti-Gq/11 antibody. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested. *P<0.0005 compared with control. (c) Dose dependence of ATP-, UTP-, ADP- and ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested.

To confirm whether a G-protein is involved in the extracellular ADO-induced inhibition of ICa, experiments were again performed using a recording pipette filled with the internal solution containing GDP-β-S. An example of the effect of 1 μM ADO on ICa recorded in the presence of GDP-β-S in the pipette solution is shown in Figure 3b (left). As summarized in Figure 3b, GDP-β-S in the pipette solution attenuated the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa.

To characterize the G-protein subtype in ADO-induced inhibition of ICa, we also verified whether the effect of ADO was mediated via Gi- or Go-proteins. An example of the effect of ADO on ICa in neuron treated with PTX (500 ng ml−1 for 12 h at 37°C) is given in the figure. As summarized in Figure 3b (center), pretreatment of PTX attenuated the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa.

The potential contribution of Gq/11-proteins in the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa was next examined. An example of the effect of ADO on ICa in the presence of anti-Gq/11 antibody in the pipette solution is shown in Figure 3b (right). The anti-Gq/11 antibody in the pipette solution did not attenuate the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. These combined results suggest that a Gi/o-protein and not Gq/11-protein is involved in the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons.

The dose–response relations in the ATP-, UTP-, ADP- and ADO-induced inhibition of ICa are also shown in Figure 3c. The half-maximum inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of ATP and UTP were estimated to be 79.5 and 78.0 μM, respectively. The IC50 of ADO was estimated to be 985 nM. The rank order of potency of P2 purinoceptor agonists was ATP=UTP>ADP>2-MeSATP=α,β-MeATP.

Pharmacological characterization of VDCC subtypes inhibited by P2Y and P1 purinoceptors

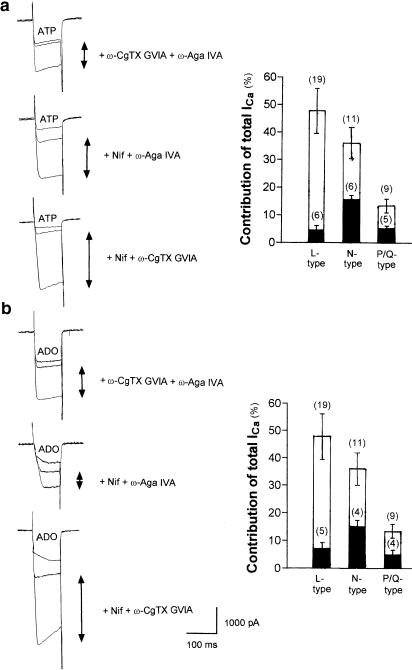

On the basis of pharmacological properties, VDCCs can be separated into low-voltage activated type (T-type) and high-voltage activated types (L-, N-, P/Q- and R-types). We have shown that SMG neurons possess several types of VDCCs (Endoh & Suzuki, 1998), that is, dihydropyridine-sensitive component (ICa-L), ω-CgTx GVIA-sensitive component (ICa-N) and ω-Aga IVA-sensitive component (ICa-P/Q). Mean percentages of ICa-L, ICa-N and ICa-P/Q of total ICa were 48.0, 36.1 and 13.5%, respectively. Therefore, we next attempted to identify which types of the VDCCs are inhibited by extracellular ATP. Since the contribution of the R-type VDCCs to the total ICa is marginal (mean percentage of ICa-R was 3.6%), we investigated the effects of ATP on the L-, N- and P/Q-type ICa components.

The effect of ATP on the ICa-L was investigated using neurons treated with ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM, N-type VDCC blocker) and ω-Aga IVA (1 μM, P/Q-type VDCC blocker) (Figure 4a, upper trace). The effect of ATP on the ICa-N was investigated using neurons treated with nifedipine (10 μM, Nif; L-type VDCC blocker) and ω-Aga IVA (1 μM) (Figure 4a, middle trace). The effect of ATP on the ICa-P/Q was investigated using neurons treated with Nif (10 μM) and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM) (Figure 4a, lower trace). The inhibition of ICa-L, ICa-N and ICa-P/Q components by extracellular ATP was 4.6±0.5, 15.8±1.3 and 5.3±0.8%, respectively, of the total ICa. Only the inhibition of ICa-N and ICa-P/Q was significant. Results shown in Figure 4a demonstrate clearly that ATP inhibited N- and P/Q-type ICa components in SMG neurons.

Figure 4.

Extracellular ATP- and ADO-induced inhibition of distinct ICa. (a) Upper panel: effect of ATP on ICa-L. Center panel: effect of ATP on ICa-N. Lower panel: effect of ATP on ICa-P/Q. Right panel: fractional components of L-, N- and P/Q-types of ICa and those inhibited by 100 μM ATP. (b) Upper panel: effect of ADO on ICa-L. Center panel: effect of ADO on ICa-N. Lower panel: Effect of ADO on ICa-P/Q. Right panel: fractional components of L-, N- and P/Q-types of ICa and those inhibited by 1 μM ADO.

As shown in Figure 3, 100 M ATP inhibited ICa by 42.0±4.6% (n=8). However, the accumulative degree of ATP-induced inhibition of ICa was about 25% in Figure 4, because extracellular application of VDCC blockers required too much time for the full ATP effects to appear. Thus, it was difficult to prevent rundown, even though we had added CP and CPK in the recording pipette.

We next investigated the effects of ADO on the L-, N- and P/Q-type ICa components. The inhibition of ICa-L, ICa-N and ICa-P/Q components by extracellular ADO was 7.1±1.1, 15.1±2.2, and 5.0±1.6%, respectively, of the total ICa. Only the inhibition of ICa-N and ICa-P/Q was significant. Results shown in Figure 4b demonstrate clearly that ADO inhibited N- and P/Q-type ICa components in SMG neurons.

Convergence of P1 and P2Y purinoceptor signalling to inhibit ICa

Convergence or nonadditivity between P1 and P2Y purinoceptor inhibitory pathways was investigated by the coapplication of agonists and by comparing the inhibition of the ICa with that produced by each of these agonists alone. A volume of 100 μM ATP inhibited ICa by 42.0±4.6% (n=8), 1 μM ADO inhibited ICa by 33.8±3.6% (n=7), and the coapplication of both 100 μM ATP and 1 μM ADO inhibited ICa by 33.9±4.2% (n=5). Thus, the mean inhibition of ICa induced by ATP was unaltered by its coapplication with ADO, suggesting that the actions of ATP and ADO are not additive, and further suggesting convergence in these inhibitory pathways (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Extracellular ATP- and ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. Summary of ATP- and ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. The histogram demonstrates the degree of ICa inhibition by 100 μM ATP alone, 1 μM ADO alone and coapplication of 100 μM ATP and 1 μM ADO.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that P1 and P2Y purinoceptors are coexpressed postsynaptically in SMG neurons. Both P1 and P2Y purinoceptors inhibit N- and P/Q-type VDCCs, presumably via G βγ subunits by extracellular ATP. Our present results, together with the results that P2X purinoceptors are also located on SMG neurons (Liu & Adams, 2001; Smith et al., 2001), indicate the growing importance of purinoceptors in the regulation of this ganglion.

According to biophysical criteria, the inhibitory effects of modulation of ICa can be divided into voltage-dependent (VD) and voltage-independent (VI) mechanisms. The VD mechanism is relieved at a higher potential or by means of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse to positive voltages (Bean, 1989; Dolphin, 1996,1998), whereas the VI mechanism is not affected by a strong voltage depolarizing prepulse (Formenti et al., 1993). In frog sympathetic ganglion cells, ATP inhibits ICa in a VD mechanism (Elmslie, 1992). In contrast, in chromaffin cells, ATP inhibits ICa in a VI mechanism (Hernández-Guijo et al., 1999).

In our experiments, double-pulse protocols demonstrated that inhibition of ICa produced by ATP was greatly reduced after a 100 mV depolarizing prepulse and therefore a VD mechanism. The prepulse also abolished the slowing of the current onset produced by ATP. A similar effect was reported for the modulation of ICa by endogenous GABA receptors in sensory neurons (Grassi & Lux, 1989). Slowing of the current onset by ATP in neurons also indicated that ATP-induced inhibition of ICa was in VD mechanism and relieved during depolarization (Bean, 1989), as reported previously for other G-protein-coupled receptors. In addition, the current–voltage relation of ICa shows that the peak current–voltage relation was altered by ATP. Similar observations were made for superior cervical sympathetic neurons (Filippov et al., 1998). The VD manner inhibition is mediated by direct binding of the G-protein βγ subunits to the VDCCs in a membrane-delimited manner (Herlitze et al., 1996; Ikeda, 1996). Our results also indicate that Gi/o-protein is involved in the ATP- and ADO-induced inhibition of ICa. It was demonstrated that Gi/o-protein is involved in the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in bovine chromaffin cells (Gandía et al., 1993). In contrast, Gi/o-protein is not involved in the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in frog sympathetic ganglion (Elmslie, 1992). In supraoptic neurons, Gi/o-protein is involved in the ADO-induced inhibition of ICa (Noguchi & Yamashita, 2000).

Purinoceptors are classified into P2 purinoceptors, sensitive to ATP and ADP, and P1 purinoceptors responding to AMP and ADO. In the present study, suramin partially antagonized the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa, while coapplication of DPCPX and suramin nearly completely antagonized it in SMG neurons suggesting the presence of both P1 and P2 purinoceptor subtypes. It has been reported that ectoenzymes are located on the cell membrane which can efficiently breakdown the ATP to ADO (Welford et al., 1986). Our data indicate that not only P2Y but also P1 purinoceptors contributed to the ATP-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons. It has already been reported that P1 purinoceptors inhibit ICa (Alvarez et al., 1990; Kato et al., 1990). We have also reported that application of ADO caused pivotal responses in SMG neurons (Suzuki et al., 1990b). In the present study, our data indicated that the extracellular ADO inhibited N- and P/Q-type VDCCs mediated by P1 purinoceptors in SMG neurons.

Cloning and pharmacological studies revealed at least five distinct subtypes of P2Y purinoceptors: P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6 and P2Y11 (Boarder & Hourani, 1998). In addition, the localization and pharmacological profiles of subtypes of the P2Y family are further reported (Burnstock, 1997). The P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 purinoceptor subtypes have been shown to be responsive to UTP (Lustig et al., 1993; Bogdanov et al., 1998; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Filippov et al., 1999). The P2Y2 and P2Y4 purinoceptors are equipotently activated by ATP and UTP (Lustig et al., 1993; Bogdanov et al., 1998; Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998). ATP was shown to be practically inactive at the P2Y6 purinoceptor in rat sympathetic neurons, whereas UTP can be its effective agonist (Filippov et al., 1999). The P2Y1 purinoceptor's rank order of potency is as follows: 2-MeSATP>ATP>UTP. The P2Y2 purinoceptor's rank order of potency is as follows: ATP=UTP≫2MeSATP. The P2Y4 purinoceptor's rank order of potency is as follows: UTP>ATP=ADP. The P2Y6 purinoceptor's rank order of potency is as follows: UTP>2MeSATP>ATP. The P2Y11 purinoceptor's rank order of potency is as follows: ATP>2MeSATP≫UTP (Burnstock, 1997). In addition, suramin antagonizes P2Y2 purinoceptors, but both P2Y4 and P2Y6 purinoceptors are suramin-insensitive (Boarder & Hourani, 1998; Bogdanov et al., 1998; King et al., 1998; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). On the other hand, PPADS are reported to antagonize P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 purinoceptors (Robaye et al., 1997; Bogdanov et al., 1998). Therefore, we consider that P2Y2 is the most possible candidate of P2Y purinoceptor subtype in P2Y-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons.

Amino-acid sequence and pharmacological studies revealed four distinct subtypes of P1 purinoceptors: A1, A2a, A2b and A3 (Fredholm et al., 1994; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). DPDPX is a specific antagonist of A1 purinoceptor. Thus, we consider that A1 is the most possible candidate of P1 purinoceptor subtype in P1-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons. It will be important in future experiments to determine which types of P1 purinoceptors contribute to the P1-induced inhibition of ICa in SMG neurons.

ATP- and UTP-induced inhibition of ICa was concentration dependent, IC50 of ATP and UTP being 79.5 μM and 78.0 M, respectively. The IC50 of ATP obtained here (79.5 μM) was similar to that found in other cell types (100 μM in sinoatrial nodal cell, Qi & Kwan, 1996; 55 μM in pelvic ganglion neurons, Zhong et al., 2001).

VDCCs are heteromultimers composed of a pore-forming α1 subunit and several auxiliary subunits (Jones, 1998). In the mammalian nervous system, five α1 subunits that exhibit distinct cellular and subcellular distributions have been described. Functional studies indicate that α1C and α1D subunits encode L-type VDCCs (Williams et al., 1992a; Tomlinson et al., 1993), α1B subunit encodes N-type VDCCs (Williams et al., 1992b; Stea et al., 1993), α1A subunit encodes VDCCs with some properties similar to both P- and Q-types (Sather et al., 1993; Stea et al., 1994) and α1E subunit encodes R-type VDCCs (Soong et al., 1993). Many neurotransmitter-induced inhibition of VDCCs is produced by the G βγ dimers, which associate with α1B VDCCs in particular (Herlitze et al., 1996; Ikeda, 1996) (but also with α1A and α1E), in a membrane-delimited manner. The relatively few inhibitory effects of L-type ICa component in this study are in agreement with the fact that G βγ dimers cannot bind to either the I–II linker region of L-type α1C subunit (De Waard et al., 1997) or the carboxyl terminus of α1C (Qin et al., 1997).

Abbreviations

- ADO

adenosine

- ADP

adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- α, β-MeATP

α,β-methylene ATP

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- GDP-β-S

guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate)

- 2-MeSATP

2-methylthioATP

- PPADS

pyridoxal-5-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- SMG

submandibular ganglion

- UTP

uridine 5′-triphosphate

- VDCC

voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel

References

- ALVAREZ T.L., MONGO K., SCAMPS F., VASSORT G. Effects of purinergic stimulation on Ca current in single frog cardiac cells. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1990;416:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00370241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAN B.P. Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature. 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOARDER M.R., HOURANI S.M.O. The regulation of vascular function by P2 receptors: multiple sites and multiple receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOGDANOV Y.D., WILDMAN S.S., CLEMENTS M.P., KING B.F., BURNSTOCK G. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat P2Y4 nucleotide receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:428–439. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Overview. Purinergic mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990;603:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb37657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. The past, present and future of purine nucleotides as signalling molecules. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1127–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE WAARD M., LIU H.Y., WALKER D., SCOTT V.E.S., GUNETT C.A., CAMPBELL K.P. Direct binding of G-protein βγ complex to voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1997;385:446–450. doi: 10.1038/385446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLPHIN A.C. Facilitation of Ca2+ current in excitable cells. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLPHIN A.C. Mechanisms of modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G-proteins. J. Physiol. 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELMSLIE K.S. Calcium current modulation in frog sympathetic neurones: multiple neurotransmitters and G proteins. J. Physiol. 1992;451:229–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDOH T., SUZUKI T. The regulating manner of opioid receptors on distinct types of calcium channels in hamster submandibular ganglion cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 1998;43:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(98)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILIPPOV A.K., WEBB T.E., BARNARD E.A., BROWN D.A. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors expressed heterologously in sympathetic neurons inhibit both N-type Ca2+ and M-type K+ currents. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5170–5179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05170.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILIPPOV A.K., WEBB T.E., BARNARD E.A., BROWN D.A. Dual coupling of heterologously-expressed rat P2Y6 nucleotide receptors to N-type Ca2+ and M-type K+ currents in rat sympathetic neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1009–1017. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORMENTI A., ARRIGONI E., MANCIA M. Two distinct modulatory effects on calcium channels in adult rat sensory neurons. Biophys. J. 1993;64:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., ABBRACCHIO M.P., BURNSTOCK G., DALY J.W., HARDEN T.K., JACOBSON K.A., LEFF P., WILLIAMS M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANDÍA L., GARCÍA A.G., MORAD M. ATP modulation of calcium channels in chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 1993;470:55–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRASSI F., LUX H.D. Voltage-dependence GABA-induced modulation of in chick sensory neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 1989;105:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERLITZE S., GARCIA D.E., MACKIE K., HILLE B., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERNÁNDEZ-GUIJO J.M., CARABELLI V., GANDÍA L., GARCÍA A.G., CARBONE E. Voltage-independent autocrine modulation of L-type channels mediated by ATP, opioids and catecholamines in rat chromaffin cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:3574–3584. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IKEDA S.R. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES S.W. Overview of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1998;30:299–312. doi: 10.1023/a:1021977304001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO M., YAMAGUCHI H., OCHI R. Mechanism of adenosine-induced inhibition of calcium current in guinea pig ventricular cells. Circ. Res. 1990;67:1134–1141. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.5.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KING B.F., TOWNSEND-NICHOLSON A., BURNSTOCK G. Metabotropic receptors for ATP and UTP: exploring the correspondence between native and recombinant nucleotide receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:506–514. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU D.-M., ADAMS D.J. Ionic selectivity of native ATP-activated (P2X) receptor channels in dissociated neurones from rat parasympathetic ganglia. J. Physiol. 2001;534:423–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSTIG K.D., SHIAU A.K., BRAKE A.J., JULIUS D. Expression cloning of an ATP receptor from mouse neuroblastoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:5113–5117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCMILLIAN M.K., SOLTOFF S.P., CANTLEY L.C., RUDEL R.A., TALAMO B.R. Two distinct cytosolic calcium responses to extracellular ATP in rat parotid acinar cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOGUCHI J., YAMASHITA H. Adenosine inhibits voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in rat dissociated supraoptic neurones via A1 receptors. J. Physiol. 2000;526:313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QI A.-D., KWAN Y.W. Modulation by extracellular ATP of L-type calcium channels in guinea-pig single sinoatrial nodal cell. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:1454–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIN N., PLATANO D., OLCESE R., STEFANI E., BIRNBAUMER L. Direct interaction of G βγ with a C-terminal G βγ-binding domain of the Ca2+ channels α1 subunit is responsible for channel inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:8866–8871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIBEIRO J.A. Purinergic regulation of acetylcholine release. Prog. Brain Res. 1996;109:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBAYE B., BOEYNAEMS J.M., COMMUNI D. Slow desensitization of the human P2Y6 receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;329:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATHER W.A., TANABE T., ZHANG J.-F., MORI Y., ADAMS M.E., TSIEN R.W. Distinctive biophysical and pharmacological properties of class A (BI) calcium channel α1-subunits. Neuron. 1993;11:291–303. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90185-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH A.B., HANSEN M.A., LIU D.-M., ADAMS D.J. Pre- and postsynaptic actions of ATP on neurotransmission in rat submandibular ganglion. Neuroscience. 2001;107:283–291. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOONG T.W., STEA A., HODSON C.D., DUBEL S.J., VINCENT S.R., SNUTCH T.P. Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science. 1993;260:1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.8388125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEA A., DUBEL S.J., PRAGNELL M., LEONARD J.P., CAMPBELL K.P., SNUTCH T.P. A β-subunit normalizes the electrophysiological properties of a cloned N-type Ca2+ channels α1-subunit. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEA A., TOMLINSON J.W., SOONG T.W., BOURINET E., DUBEL S.J., VINCENT S.R., SNUTCH T.P. Localization and functional properties of a rat brain α1A calcium channel reflect similarities to neuronal Q- and P-type channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:10576–10580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUKI T., AIDA H., AEBA A., SAKADA S. Responses of hamster submandibular ganglion cells to ATP. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 1990a;31:63–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUKI T., FUKUDA S., SAKADA S. Adenosine hyperpolarization and slow hyperpolarizing synaptic potential in the hamster submandibular ganglion cell. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 1990b;31:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMLINSON W.J., STEA A., BOURINET E., CHARNET P., NARGEOT J., SNUTCH T.P. Functional properties of a neuronal class C L-type calcium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90006-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KÜGELGEN I., KURZ K., STARKE K. Axon terminal P2-purinoceptors in feedback control of sympathetic transmitter release. Neuroscience. 1993;56:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90330-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELFORD L.A., CUSACK N.J., HOURANI S.M.O. ATP analogues and the guinea-pig taenia coli: a comparison of the structure–activity relationships of ectonucleotidases with those of the P2-purinoceptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1986;129:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS M.E., BRUST P.F., FELDMAN D.H., PATTHI S., SIMERSON S., MAROUFI A., MCCUE A.F., VELICELEBI G., ELLIS S.B., HARPOLD M.M. Structure and functional expression of an ω-conotoxin-sensitive human N-type calcium channel. Science. 1992b;257:389–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1321501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS M.E., FELDMAN D.H., MCCUE A.F., BRENNER R., VELICELEBI G., ELLIS S.B., HARPOLD M.M. Structure and functional expression of α1, α2, and β subunits of a novel human neuronal calcium channel subtype. Neuron. 1992a;8:71–84. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90109-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA E., ENDOH T., SUZUKI T. Angiotensin II-induced inhibition of calcium currents via Gq/11-protein involving protein kinase C in hamster submandibular ganglion neurons. Neurosci. Res. 2002;43:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHONG Y., DUNN P.M., BURNSTOCK G. Multiple P2X receptors on guinea-pig pelvic ganglion neurons exhibit novel pharmacological properties. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:221–233. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMANN H. Signaling via ATP in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]