Abstract

The present study was aimed at examining P2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation in human vessels. The isometric tension was recorded in isolated segments of the human left internal mammary artery branches precontracted with 1 μM noradrenaline.

Endothelial denudation abolished the dilator responses.

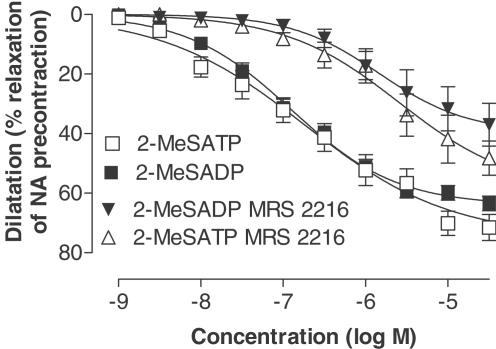

The selective P2Y1 agonist, 2-MeSADP, induced a potent vasodilatation (pEC50=6.9±0.1). The P2Y1 antagonist of 10 μM, MRS 2216, shifted the 2-MeSADP concentration-response curve 1.1 log units to the right. The combined P2Y1 and P2X agonist, 2-MeSATP, stimulated a dilatation with a potency similar to that of 2-MeSADP. Furthermore, MRS 2216 had a similar antagonistic effect on both 2-MeSATP and 2-MeSADP indicating that P2X receptors do not mediate vasodilatation.

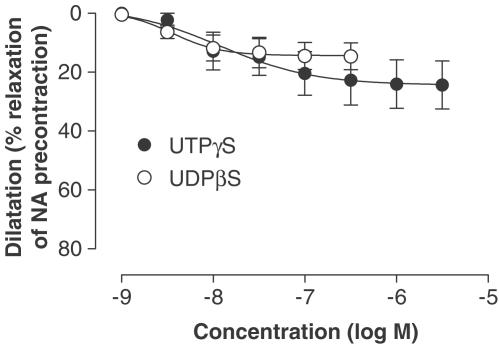

Both the P2Y2/4 agonist, UTPγS and the P2Y6 agonist, UDPβS, stimulated potent dilatations (pEC50=7.8±0.4 for UTPγS and 8.4±0.2 for UDPβS).

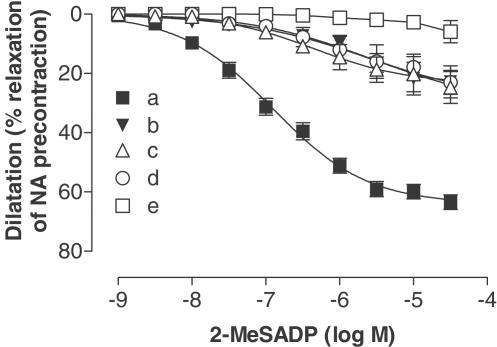

The 2-MeSADP-induced nitric oxide (NO)-mediated dilatation was studied in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. The involvement of the endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor (EDHF) was investigated in the presence of 0.1 mM L-NOARG and indomethacin. The involvement of prostaglandins was investigated in the presence of L-NOARG, charybdotoxin and apamin. Both NO, EDHF and prostaglandins mediated 2-MeSADP dilatation with similar efficacy (Emax=25±5% for NO, 25±6% for EDHF and 27±5% for prostaglandins).

In conclusion, extracellular nucleotides induce endothelium-derived vasodilatation in human vessels by stimulating P2Y1, P2Y2/4 and P2Y6 receptors, while P2X receptors are not involved. Endothelial P2Y receptors mediate dilatation by release of EDHF, NO and prostaglandins

Keywords: coronary circulation, endothelium, endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor, human, nitric oxide, nucleotide, P2 receptor, vasodilatation

Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), uridine triphosphate (UTP) and uridine diphosphate (UDP) regulate vascular tone and blood pressure by stimulating P2 receptors (Gordon, 1986; Kunapuli & Daniel, 1998). Nucleotides induce vasoconstriction stimulating P2 receptors on the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). Conversely, P2 receptors on the endothelium induce vasodilatation by the release of prostaglandins, nitric oxide (NO) and endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor (EDHF) (Malmsjo et al., 1998; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Malmsjo et al., 1999a,1999c). Furthermore, extracellular nucleotides have been shown to mediate both mitogenic effects, angiogenesis, apoptosis and release of tissue-plasminogen activator (t-PA) in endothelial cells (EC) (Satterwhite et al., 1999; von Albertini et al., 1998; Hrafnkelsdottir et al., 2001).

P2 receptors can be divided into two classes on the basis of their signal transmission mechanisms and their characteristic molecular structures: ligand-gated intrinsic ion channels, P2X receptors and G-protein-coupled P2Y receptors. The P2X receptor family is composed of seven cloned subtypes, all activated by the binding of extracellular ATP (P2X1–P2X7) (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Norenberg & Illes, 2000; Khakh et al., 2001). The P2Y family is composed of seven cloned and functionally defined subtypes. P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 are ADP receptors specifically activated by the stable analogue 2-methylthio adenosine 5′-diphosphate (2-MeSADP) (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; von Kugelgen & Wetter, 2000; Hollopeter et al., 2001). P2Y2 receptors are stimulated by UTP, uridine 5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate (UTPγS) and ATP, while P2Y4 receptors are only stimulated by UTP and UTPγS. P2Y6 is activated by UDP and 5′-O-2-thiodiphosphate (UDPβS) (Lazarowski et al., 1996; Nicholas et al., 1996; Hou et al., 2002). The P2Y11 receptor is stimulated by ATP, with no selective agonist known so far (Communi et al., 1997).

The P2X1 receptor is located on VSMCs and is the main vasoconstrictor among the P2X receptors (Evans & Kennedy, 1994), but in the endothelium pharmacological evidence for P2X-mediated dilatation has been scarce. Recently, high expression levels for the P2X4 receptor were found in the EC by Northern blot analysis and competitive, specific RT–PCR (Yamamoto et al., 2000b). Indeed, we have confirmed that P2X4 is by far the P2 receptor having the highest messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) level in human EC, even compared to P2Y receptors (Wang et al., 2002). Other P2X receptors had considerably lower amounts of mRNA. Furthermore, all P2X subtypes have been detected with immunohistochemistry in human EC, but it is not possible to make any quantitative assessment of their relative expression with this method (Ray et al., 2002). The P2X4 receptor is involved in shear stress-mediated EC activation if ATP is present, but any dilator function has not been demonstrated (Yamamoto et al., 2000b).

Molecular and functional expressions of P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors have been shown in EC (Gordon, 1986; Pirotton et al., 1996; Kunapuli, 1998; Kunapuli & Daniel, 1998; Rump et al., 1998; Viana et al., 1998). Recently, we quantified P2Y receptors in human EC and found high mRNA levels of P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2Y11 (Wang et al., 2002). Thus, mRNA and protein for a large number of P2 receptors in EC have been shown, evidence for a functional role is lacking for several of the subtypes.

The endothelium plays a fundamental role in vascular physiology and pathophysiology, and the P2 receptors could be of major importance in regulating endothelial function. We therefore aimed at characterising the P2 receptors responsible for endothelium-derived vasodilatation in human vessels, using selective agonists and a recently developed antagonist. Furthermore, the involvement of different dilator endothelial mediators was investigated.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Branches of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) were obtained from 20 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. The patient group consisted of 14 males and six females with an age of 62±9 years (mean±s.e.m.). All suffered from ischaemic heart disease and six from diabetes mellitus. All patients were medicated with aspirin, 14 with beta-blockers and two with clopidogrel. Five of the diabetic patients were treated with sulphonylurea and one with both sulphonylurea and insulin. The material was too small for subgroup comparisons. The blood vessels were kept in cold buffer solution (for composition, see below) and transported to the laboratory where they were dissected free of adhering tissue under a microscope. The LIMA branches had a maximal inner diameter of approximately 0.5–1 mm. The vessels were cut into 1.5 mm long cylindrical segments. Each segment was mounted on two L-shaped metal prongs, one of which was connected to a force–displacement transducer (FT03C) for continuous recording of the isomeric tension (Hogestatt et al., 1983). The position of the holder could be changed by means of a movable unit allowing fine adjustments of the vascular resting tension by varying the distance between the metal prongs. The mounted vessel segments were immersed in temperature-controlled (37°C) tissue baths containing a bicarbonate-based buffer solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 119, NaHCO3 15, KCl 4.6, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.5 and glucose 5.5. The solution was continuously gassed with 5% CO2 in O2 resulting in a pH of 7.4. The artery segments were allowed to stabilise at a resting tension of 1.5 mN for 1 h before the experiments were started. The contractile capacity of each vessel segment was examined by exposure to a potassium-rich (60 mM) buffer solution in which NaCl was exchanged for an equimolar concentration of KCl (for composition, see above). When two reproducible contractions had been achieved the vessels were used for further studies. Eight ring segments were studied at the same time in separate tissue baths. Relaxation was examined in vascular segments precontracted by 1 μM noradrenaline (NA). Agonists were added cumulatively to determine concentration–response relations. A functional endothelium was confirmed by monitoring dilator responses to 2-MeSADP after NA preconstriction. If dilator responses to 2-MeSADP were absent, the lack of a functional endo-thelium could be confirmed by adding acetylcholine. The vessel segments that did not dilate were judged to have a nonfunctioning endothelium and were excluded from the study.

In experiments where endothelial denudation was needed, this was done by rubbing the luminal side of the vessel gently with a needle before mounting in the myograph.

Agonists

To stimulate P2X1 receptors αβ-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate (α,β-MeATP) was used, 2-MeSADP for P2Y1, 2-methylthio adenosine 5′-triphosphate (2-MeSATP) for P2X and P2Y1 receptor, UTPγS for P2Y2 and P2Y4 (P2Y2/4) (Lazarowski et al., 1996), UDPβS for P2Y6 (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). To study the P2Y receptor-stimulated dilatation without interference of simultaneous P2X1 receptor-induced responses, the extracellular nucleotides were added after desensitisation with 10 μM αβ-MeATP for 10 min (Kasakov & Burnstock, 1982). As the P2Y receptors are only very slowly desensitised, these agonists could be added cumulatively to determine concentration–response relations (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). Dilatation induced by acetylcholine (ACh) was studied in the presence and absence of 2-chloro-2′-deoxy-6-methyladenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate (MRS 2216).

Antagonists

Antagonists were administered 15 min before the application of agonists. To block the P2Y1 receptor, the selective antagonist, the deoxyadenosine bisphosphate derivative MRS 2216 (10 μM), was used (Brown et al., 2000).

The vasodilator and hyperpolarising effect of EDHF is antagonised by a combination of the potassium channel inhibitors, charybdotoxin and apamin (Chataigneau et al., 1998). Arginine analogues like L-NOARG (Nϖ-nitro-L-arginine) inhibit NO synthesis, but do not affect EDHF (Huang et al., 1988; Chen et al., 1991; Fujii et al., 1992). Although potential problems with inhibiting NO-synthetase have been reported, the high concentration of L-NOARG that was used in these experiments has been shown to totally block the release of NO (Zygmunt et al., 1994).

The 2-MeSADP-induced NO-mediated dilatation was studied in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. EDHF was studied in the presence of 0.1 mM L-NOARG and indomethacin. The involvement of prostaglandins was investigated in the presence of L-NOARG, charybdotoxin and apamin.

Drugs

Agonist selectivity and stability are potential problems when analysing the pharmacological profiles of natural nucleotides in intact tissue. Therefore, more stable compounds were used, UTPγS, UDPβS, 2-MeSADP, 2-MeSATP and αβ-MeATP (for a review see Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). UTPγS and UDPγS were gifts from Inspire Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; MRS 2216 was a gift from KA Jacobson, Molecular Recognition Section, Bioorganic Chemistry, NIH, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A. αβ-MeATP, 2-MeSADP, 2-MeSATP, NA, ACh, indomethacin, L-NOARG, charybdotoxin and apamin were purchased from SigmaCo, U.S.A. All the drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Lund University approved the project.

Calculation and statistics

Calculations and statistics were performed using the GraphPad Prism 3.02 software. The negative logarithm of the drug concentration that elicited 50% relaxation (pEC50) was determined by fitting the data to the Hill equation. Emax refers to maximum relaxation calculated as the percentage of the corresponding precontraction with NA. n denotes the number of patients. Statistical significance was accepted when P<0.05, using Student's t-test analysing the 2-MeSADP and 2-MeSATP data with and without P2Y1 blocker. To analyse the blocking of the dilator mediators (NO, EDHF and PG) the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by the Dunnett multiple comparisons test were used. Values are presented as mean±s.e.m.

P2Y1 receptor antagonism

Antagonist equilibrium dissociation constant (apparent KB) for the P2Y1 receptor antagonist, MRS 2216, was determined by Gaddum analysis. This method involves the estimation of equieffective agonist concentrations in the presence and absence of a fixed antagonist concentration (Lazareno & Birdsall, 1993), according to the following equation: KB=[antagonist]conc./(((EC50agonist with antagonist)/EC50 agonist)−1)

Results

P2X1 receptor desensitation

A concentration of 10 μM αβ-MeATP induced a transient contraction. When αβ-MeATP was added a second time, no contraction could be observed, indicating desensitised P2X1 receptors.

Endothelial denudation

Relaxation to each agonist was tested after endothelial denudation in vessels from at least three patients, but none of the agonists caused dilatation.

P2Y receptor-mediated dilatations

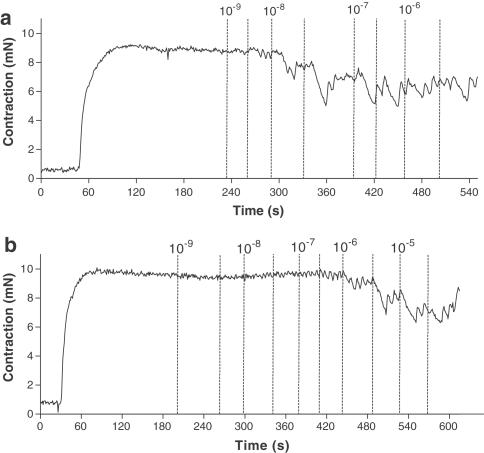

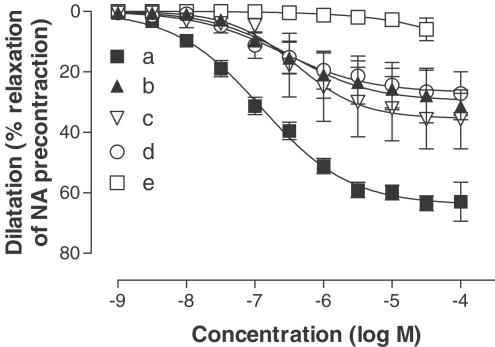

The selective P2Y1 receptor agonist 2-MeSADP caused a maximum vasodilatation of 68±3% (Figure 1 and Table 1). The P2Y1 antagonist MRS 2216 caused a rightward shift of the concentration–response curve changing the pEC50 value from 6.9±0.1 to 5.8±0.3 (Figure 1 and Table 1). The pKB for MRS 2216 was 6.3. A myograph registration of the dilator response to P2Y1 agonist with and without P2Y1 antagonist is shown in Figures 2a and b. There were no significant differences in Emax or in pEC50 between dilatation for 2-MeSADP and 2-MeSATP either alone or after addition of the P2Y1 antagonist MRS 2216 (Figure 1 and Table 1). Both the P2Y2/4 agonist UTPγS and the P2Y6 agonist UDPβS induced potent vasodilatation with low efficacy (see Figure 3 and Table 1). The contractile response to noradrenaline was not affected by the P2Y1 blocker, having an average of 168±17% and 172±15% of the initial potassium contraction with and without MRS 2216. There was no significant change in the ACh-induced dilatation by the presence of MRS 2216 (pEC50=7.2±0.2, pEC50 (MRS 2216)=7.3±0.2, Emax=50±5% and Emax (MRS 2216)=57±4%).

Figure 1.

Concentration-dependent dilatation in response to 2-MeSADP and 2-MeSATP with and without pretreatment with the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2216 (10 μM). The nucleotides were added after desensitisation of P2X1 receptors with αβ-MeATP (10 μM). The dilatations are expressed as percentage relaxation of an initial precontraction induced by NA (1 μM). Data are shown as means±s.e.m.

Table 1.

Concentration-dependent dilatations stimulated by UTPγS, UDPβS, 2-MeSADP and 2-MeSATP with and without the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2216 (10 μM)

| Agonist/antagonist | Emax (%) | pEC50 (−log M) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-MeSADP | 68±3 | 6.9±0.1 | 12 | |

| 2-MeSATP | 63±5 | 6.7±0.3 | 12 | NS |

| 2-MeSADP/MRS 2216 | 40±7 | 5.8±0.3 | 8 | |

| 2-MeSATP/MRS 2216 | 42±8 | 5.6±0.4 | 6 | NS |

| UTPγS | 24±4 | 7.8±0.4 | 6 | |

| UDPβS | 14±2 | 8.4±0.2 | 9 |

The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by NA (1 μM). Data are shown as Emax±s.e.m. and pEC50±s.e.m. There was no significant difference between 2-MeSADP and 2-MeSATP with or without MRS 2216 with respect to the induced dilatation.

Figure 2.

The myograph registration of NA (1 μM) contraction followed by concentration-dependent dilatation to 2-MeSADP with (a) and without (b) pretreatment with the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2216 (10 μM). The time points for the addition of the respective concentrations of 2-MeSADP are marked in the figure by broken lines. The nucleotides were added after desensitisation of P2X1 receptors with αβ-MeATP (10 μM).

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent dilatation stimulated by UDPβS and UTPγS in human LIMA branches, after desensitisation of P2X1 receptors with αβ-MeATP (10 μM). The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by noradrenaline (1 μM). Data are shown as means±s.e.m.

Mediators

Pretreatment of the vessel segments with 10 μM indomethacin, 0.1 mM L-NOARG, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin, abolished all vasodilator responses to the different agonists. In the presence of indomethacin, charybdotoxin and apamin the response stimulated by 2-MeSADP was reduced to 25±6% relaxation of NA contraction (Figure 3 and Table 2). Inhibition with L-NOARG and indomethacin reduced the dilator response stimulated by 2-MeSADP to 25±5% of NA contraction (Figure 3 and Table 2). In the presence of L-NOARG, charybdotoxin and apamin the response stimulated by 2-MeSADP was reduced to 27±5% relaxation of NA contraction (Figure 4 and Table 2). The dilatations were significantly reduced compared to 2-MeSADP alone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Concentration-dependent dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP with and without blocking of the mediators

| Blockers | Emax (%) | pEC50 (−log M) | n | Versus control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Control (no blockers) | 68±3 | 6.9±0.1 | 12 | |

| b | 10 μM indomethacin | 25±6 | 5.4±1.0 | 6 | ** |

| 50 nM charybdotoxin | |||||

| 1 μM apamin | |||||

| c | 10 μM indomethacin | 25±5 | 6.3±0.3 | 7 | ** |

| 0.1 mM L-NOARG | |||||

| d | 0.1 mM L-NOARG | 27±5 | 5.7±0.7 | 6 | ** |

| 50 nM charybdotoxin | |||||

| 1 μM apamin |

(a) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP. (b) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μm indomethacin, 50 nm charybdotoxin and 1 μm apamin. (c) The dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μm indomethacin and 0.1 mm l-NOARG. (d) Dilatation induced by the 2-MeSADP in the presence of 0.1 mm l-NOARG, 50 nm charybdotoxin and 1 μm apamin. The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by noradrenaline (1 μm). Data are shown as Emax±s.e.m. and pEC50±s.e.m.

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP after desensitisation of P2X1 receptors with αβ-MeATP (10 μM). (a) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP. (b) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. (c) The dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin and 0.1 mM L-NOARG. (d) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 0.1 mM L-NOARG, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. (e) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin, 0.1 mM L-NOARG, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by noradrenaline (1 μM). Data are shown as means±s.e.m.

In the presence of indomethacin the response to 2-MeSADP was reduced to 36±10% relaxation of NA contraction, representing the prostaglandins and EDHF-mediated dilatation (Figure 5 and Table 3). In the presence of charybdotoxin and apamin the response to 2-MeSADP was reduced to 30±7% relaxation of NA contraction, representing the NO and prostaglandins-mediated dilatation (Figure 5 and Table 3). In the presence of L-NOARG the dilator response to 2-MeSADP was reduced to 32±4% of NA contraction, representing the prostaglandins and EDHF-mediated dilatation (Figure 5 and Table 3). The results differed significantly from the response to 2-MeSADP (Table 3). No significant changes in NA contraction with and without the different blockers were observed in this material.

Figure 5.

Concentration-dependent dilatation in response to 2-MeSADP after desensitisation of P2X1 receptors with αβ-MeATP (10 μM). (a) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP. (b) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 0.1 mM L-NOARG. (c) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin. (d) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. (e) Dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP in the presence of 0.1 mM L-NOARG, 10 μM indomethacin, 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by noradrenaline (1 μM). Data are shown as means±s.e.m.

Table 3.

Concentration-dependent dilatation in response to 2-MeSADP with and without blocking of the mediators

| Blockers | Emax (%) | pEC50 (−log M) | n | Versus control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Control (no blockers) | 64±3 | 6.9±0.1 | 12 | |

| b | 0.1 mM L-NOARG | 32±4 | 6.5±0.3 | 3 | ** |

| c | 10 μM indomethacin | 36±10 | 6.4±0.3 | 5 | ** |

| d | 50 nM charybdotoxin | 30±7 | 6.6±0.3 | 11 | ** |

| 1 μM apamin |

NO, prostaglandins and EDHF with 0.1 mM L-NOARG, 10 μM indomethacin, 50 nMcharybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin. The table shows the remaining dilator response to 2-MeSADP after (b) blockade of EDHF with 50 nM charybdotoxin and 1 μM apamin, (c) blockade of NO with 0.1 mM L-NOARG and (d) blockade of prostaglandins with 10 μM indomethacin. The dilatations are expressed as percentage of an initial precontraction induced by NA (1 μM). Data are shown as Emax±s.e.m. and pEC50±s.e.m.

Discussion

In this study, the dilator P2Y receptors have been characterised in human LIMA branches. In agreement with the initial definition of P2Y receptors by Burnstock & Kennedy (1985), stimulation of endothelial P2Y1 receptors with the selective agonist 2-MeSADP induced the most efficacious dilatation. This indicates an important dilator role for endothelial P2Y1 receptors. Recent real-time PCR measurements have demonstrated high P2Y1 receptor mRNA levels in human EC (Wang et al., 2002).

MRS 2216 is a new selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist that has no effect on P2X1 and P2X3 receptors (Brown et al., 2000). It has a structure similar to that of 2′-deoxy-N6-methyladenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate (MRS 2179) that has been evaluated in cells selectively transfected with different P2Y receptor subtypes and shown to be a specific antagonist to P2Y1, with no effect on the other P2Y receptor subtypes (Jacobson et al., 2002). MRS 2179 is 11-fold selective for P2Y1 versus P2X1 receptors (Brown et al., 2000). The dilator effects of 2-MeSADP were inhibited by 10 μM MRS 2216 in the present study, indicating that it acts as a potent P2Y1 antagonist in intact blood vessels. Furthermore, the specificity was supported by a lack of effect on ACh-mediated vasodilatation. This is one step towards the development of a P2Y1 receptor antagonist for human use, for which an important role as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation can be anticipated.

Ligand instability is a problem especially when investigations are performed in intact tissues as nucleotide triphosphates are metabolised by ectonucleotidases on the cell membranes (Malmsjo et al., 2000a,2000b). The vascular actions of the pyrimidine-sensitive receptors were not possible to evaluate until the stable pyrimidine analogues UTPγS and UDPβS were characterised on selectively transfected P2Y receptor subtypes (Lazarowski et al., 1996; Hou et al., 2002). UTPγS is selective for P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors but cannot discriminate between them (Lazarowski et al., 1996). UDPβS is selective for P2Y6 receptors with no effects on the other P2 receptors (Hou et al., 2002). It has been demonstrated that UTP mediates endothelium-derived dilatation in human coronary arteries, but it was not possible to discriminate between the pyrimidino-receptor subtypes (Hansmann et al., 1998).

Previous studies have not been able to demonstrate any P2Y6 receptor-mediated dilatations, but P2Y6 receptors on VSMCs have been repeatedly shown to mediate vasoconstriction (Malmsjo et al., 2000a). Surprisingly, P2Y6 receptors were expressed to a similar extent in EC as in VSMC at the protein level (Wang et al., 2002). In the present study, the selective P2Y2/4 agonist, UTPγS and the selective P2Y6 receptor agonist UDPβS induced potent vasodilatations with low efficacy. The low maximum dilatation is probably because of counteracting contractile P2Y2/4 and P2Y6 receptors on VSMCs. Both UTPγS and UDPβS induced vasoconstriction (data not shown), indicating the presence of P2Y2/4 and P2Y6 receptors also on VSMCs in these LIMA branches. The observation of a vasodilator effect induced by UDPβS is important, because it implies that a selective P2Y6 receptor agonist could have hypotensive effects, particularly if administered only at the endothelial side of the vessel. On the other hand, it could be valuable for vasodilation or t-PA release.

UTPγS induced potent dilatations with low efficacy, indicating the presence of dilator P2Y2 or P2Y4 receptors on the endothelium. P2Y2 receptor mRNA has been detected to a level similar to that of P2Y1 receptor mRNA in human EC, the level of P2Y4 receptor mRNA was detected to a lower extent (Wang et al., 2002). These results suggest that the UTPγS dilatation was mediated via P2Y2 and not P2Y4 receptors. Real-time PCR experiments have also demonstrated the presence of P2Y11 receptor mRNA in EC (Wang et al., 2002). P2Y11 is an ATP receptor for which selective agonists have not yet been developed. Therefore, the importance of this receptor in inducing vasodilatation cannot be elucidated yet.

Endothelial P2X receptors

Although considerable levels of mRNA of P2X receptors in EC has been shown, no dilator effects of P2X receptors have yet been demonstrated (Yamamoto et al., 2000a). The highest level of P2 receptor mRNA corresponded to the P2X4 receptor. One difficulty in studying P2X receptors is that no selective P2X receptor antagonists have yet been developed. From the present study it can be concluded that P2X receptors do not induce vasodilatation in human LIMA branches. Firstly, αβ-MeATP did not elicit vasodilatation, indicating no effect of P2X1 and P2X3 receptors. Secondly, the selective P2Y1 receptor agonist, 2-MeSADP, induced dilatations that were similar to those for the combined P2Y1 and P2X receptor agonist, 2-MeSATP. Thirdly, the selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist, MRS 2216, had the same inhibitory effect of the dilatation induced by 2-MeSADP, as that induced by 2-MeSATP. Thus, even if the P2X4 receptor has the highest mRNA level in EC we could not find evidence of any dilator action. However, it may have other roles such as angiogenesis, t-PA release or even apoptosis (von Albertini et al., 1998; Satterwhite et al., 1999; Hrafnkelsdottir et al., 2001).

Dilatation mediators

Activation of P2Y receptors on EC induces vasodilatation by release of prostaglandins and NO (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). In animal studies, P2Y receptors have also been shown to stimulate EDHF-mediated dilatation (Malmsjo et al., 1998,1999c). Infusion of UTP and ATP in humans reduces forearm vascular resistance independent of prostaglandins and NO (Hrafnkelsdottir et al., 2001). Nonetheless, the factor responsible for the remaining dilatation has not been characterised in humans in accordance with all the requirements needed for identifying EDHF.

Although the chemical identity of EDHF remains unknown, certain criteria have been postulated to identify it. EDHF is released by the endothelium, not inhibited by antagonists of NO synthetase or cyclooxygenase pathways, that hyperpolarises and relaxes VSMCs. The dilator effect of EDHF can be antagonised by the potassium channel inhibitors charybdotoxin and apamin (Corriu et al., 1996; Zygmunt & Hogestatt, 1996; Chataigneau et al., 1998; Zygmunt et al., 1998). In the mesenteric artery, activation of P2Y receptors induces endothelium-derived vasodilatation mediated by a factor distinct from NO and prostaglandins that is blocked by charybdotoxin and apamin, indicating that it is EDHF (Malmsjo et al., 1998). This was confirmed by electrophysiological experiments in which both ACh and P2Y receptor agonists induce endothelium-derived hyperpolarisation of VSMCs (Malmsjo et al., 1999c). The hyperpolarisation was antagonised by charybdotoxin and apamin, confirming the use of this combination to inhibit EDHF.

In the present study, 2-MeSADP induced endothelium-derived dilatations of the LIMA branches. Pretreatment of the vessel segments with L-NOARG, indomethacin, charybdotoxin and apamin abolished all vasodilator responses to the agonist, indicating that no dilator mediator other than NO, prostaglandins or EDHF was involved. The dilatations turned out to be mediated by a similar contribution of EDHF, nitric oxide and prostaglandins. This indicates that EDHF is at least as important as NO in mediating vasodilatation to extracellular nucleotides in man. The evidence is in line with our findings in the human forearm where we were unable to block UTP-mediated reduction in vascular resistance by L-NAME and indomethacin (Satterwhite et al., 1999; Hrafnkelsdottir et al., 2001). Furthermore, it is supported by previous evidence of EDHF-mediated dilatation in LIMA for other agonists (Liu et al., 2000; He & Liu, 2001). Prostaglandins were at least as important as NO in mediating vasodilatation to extracellular nucleotides in man. This stands in contrast to recent animal studies where prostaglandins played only a minor role in mediating P2Y receptor induced dilatation (Malmsjo et al., 1998). Furthermore, the dilatation mediated by prostaglandins may have been underestimated in these patients, because all were medicated with aspirin. It should be noted that this study was performed on arteries from patients with atherosclerotic disease where the endothelium function could be altered, although the vessels used did not show any signs of athero-sclerosis. For obvious reasons, the availability of arteries from healthy individuals is limited. The importance of EDHF in inducing dilatation has been shown to be greater in rats with congestive heart failure (Vargas et al., 1996; Malmsjo et al., 1999b). On the other hand, in hypertensive patients, the ATP induced vasodilatation did not differ from healthy controls in vivo (Nilsson et al., 2000).

Conclusion

The P2Y1 receptor selective agonist, 2-MeSADP, induced the most potent and efficacious dilatation in human arteries. The P2Y2/4 agonist UTPγS also induced vasodilatation. Experiments with UDPβS demonstrated for the first time a role for P2Y6 receptors in stimulating endothelium-derived relaxation in humans. The UTPγS and the UDPβS dilatations were less efficacious than that induced by 2-MeSADP, probably because of the counteracting contractile effects of the two former agonists. The highest expressed P2 receptor in EC, the P2X4 receptor, did not mediate endothelium-derived dilatation. This study is the first to provide thorough evidence that nucleotides induce dilatation of human arteries via EDHF, in addition to the previously studied NO and prostaglandins.

Acknowledgments

The study has been supported by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, Franke and Margareta Bergqvist Foundation, the Wiberg Foundation, the Bergwall Foundation, the Zoegas Foundation, the Tore Nilsson Foundation and the Swedish Medical Research Council Grant 13130.

Abbreviations

- 2-MeSADP

2-methylthio adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- 2-MeSATP

2-methylthio adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- αβ-MeATP

αβ-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- Ach

acetylcholine

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ANOVA

the one-way analysis of variance

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- EC

endothelial cells

- EC50

effective concentration (e.g. 50% of maximum)

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor

- LIMA

left internal mammary artery

- L-NOARG

Nϖ-nitro-L-arginine

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- MRS 2179

2′-deoxy-N6-methyladenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate

- MRS 2216

2-chloro-2′-deoxy-6-methyladenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate

- NA

noradrenaline

- NO

nitric oxide

- t-PA

tissue-plasminogen activator

- UDP

uridine diphosphate

- UDPβS

uridine 5′-O-2-thiodiphosphate

- UTP

uridine triphosphate

- UTPγS

uridine 5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cells

References

- BROWN S.G., KING B.F., KIM Y-C., JANG S.Y., BURNSTOCK G., JACOBSON K.A. Activity of novel adenine nucleotide derivatives as agonists and antagonists at recombinant rat P2X receptors. Drug Dev. Res. 2000;49:253–259. doi: 10.1002/1098-2299(200004)49:4<253::AID-DDR4>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G., KENNEDY C. Is there a basis for distinguishing two types of P2-purinoceptor. Gen. Pharmacol. 1985;16:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATAIGNEAU T., FELETOU M., THOLLON C., VILLENEUVE N., VILAINE J.P., DUHAULT J., VANHOUTTE P.M. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in guinea-pig carotid, rat mesenteric and porcine coronary arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:968–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN G., YAMAMOTO Y., YAMAMOTO Y., MIWA K., SUZUKI H. Hyperpolarization of arterial smooth muscle induced by endothelial humoral substances PG-H1888-92. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:1888–1892. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.6.H1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMMUNI D., GOVAERTS C., PARMENTIER M., BOEYNAEMS J.M. Cloning of a human purinergic P2Y receptor coupled to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31969–31973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRIU C., FELETOU M., CANET E., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-derived factors and hyperpolarization of the carotid artery of the guinea-pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:959–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS R.J., KENNEDY C. Characterization of P2-purinoceptors in the smooth muscle of the rat tail artery: a comparison between contractile and electrophysiological responses. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJII K., TOMINAGA M., OHMORI S., KOBAYASHI K., KOGA T., TAKATA Y., FUJISHIMA M. Decreased endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization to acetylcholine in smooth muscle of the mesenteric artery of spontaneously hypertensive rats. PG-660-9. Circ. Res. 1992;70:660–669. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDON J.L. Extracellular ATP: effects, sources and fate. Biochem. J. 1986;233:309–319. doi: 10.1042/bj2330309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSMANN G., IHLING C., PIESKE B., BULTMANN R. Nucleotide-evoked relaxation of human coronary artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;359:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE G.W., LIU Z.G. Comparison of nitric oxide release and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated hyperpolarization between human radial and internal mammary arteries. Circulation. 2001;104:I344–I349. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGESTATT E.D., ANDERSSON K.E., EDVINSSON L. Mechanical properties of rat cerebral arteries as studied by a sensitive device for recording of mechanical activity in isolated small blood vessels. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1983;117:49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb07178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLOPETER G., JANTZEN H.M., VINCENT D., LI G., ENGLAND L., RAMAKRISHNAN V., YANG R.B., NURDEN P., NURDEN A., JULIUS D., CONLEY P.B. Identification of the platelet ADP receptor targeted by antithrombotic drugs. Nature. 2001;409:202–207. doi: 10.1038/35051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOU M., HARDEN T.K., KUHN C.M., BALDETORP B., LAZAROWSKI E., PENDERGAST W., MOLLER S., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. UDP acts as a growth factor for vascular smooth muscle cells by activation of P2Y(6) receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;282:H784–H792. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00997.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HRAFNKELSDOTTIR T., ERLINGE D., JERN S. Extracellular nucleotides ATP and UTP induce a marked acute release of tissue-type plasminogen activator in vivo in man. Thromb. Haemostt. 2001;85:875–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG A.H., BUSSE R., BASSENGE E. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization of smooth muscle cells in rabbit femoral arteries is not mediated by EDRF (nitric oxide) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;338:438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00172124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON K.A., JARVIS M.F., WILLIAMS M. Purine and pyrimidine (P2) receptors as drug targets. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:4057–4093. doi: 10.1021/jm020046y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASAKOV L., BURNSTOCK G. The use of the slowly degradable analog, alpha, beta-methylene ATP, to produce desensitisation of the P2-purinoceptor: effect on non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic responses of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1982;86:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHAKH B.S., BURNSTOCK G., KENNEDY C., KING B.F., NORTH R.A., SEGUELA P., VOIGT M., HUMPHREY P.P. International Union of Pharmacology. XXIV. Current status of the nomenclature and properties of P2X receptors and their subunits. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNAPULI S.P. Multiple P2 receptor subtypes on platelets: a new interpretation of their function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:391–394. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNAPULI S.P., DANIEL J.L. P2 receptor subtypes in the cardiovascular system. Biochem. J. 1998;336:513–523. doi: 10.1042/bj3360513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARENO S., BIRDSALL N.J. Estimation of competitive antagonist affinity from functional inhibition curves using the Gaddum, Schild and Cheng-Prusoff equations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:1110–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZAROWSKI E.R., WATT W.C., STUTTS M.J., BROWN H.A., BOUCHER R.C., HARDEN T.K. Enzymatic synthesis of UTP gamma S, a potent hydrolysis resistant agonist of P2U-purinoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Z.G., GE Z.D., HE G.W. Difference in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated hyperpolarization and nitric oxide release between human internal mammary artery and saphenous vein. Circulation. 2000;102:III296–III301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., ADNER M., HARDEN T.K., PENDERGAST W., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. The stable pyrimidines UDPbetaS and UTPgammaS discriminate between the P2 receptors that mediate vascular contraction and relaxation of the rat mesenteric artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000a;131:51–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., BERGDAHL A., MOLLER S., ZHAO X.H., SUN X.Y., HEDNER T., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. Congestive heart failure induces downregulation of P2X1-receptors in resistance arteries. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999a;43:219–227. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., BERGDAHL A., ZHAO X.H., SUN X.Y., HEDNER T., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. Enhanced acetylcholine and P2Y-receptor stimulated vascular EDHF-dilatation in congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999b;43:200–209. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. P2U-receptor mediated endothelium-dependent but nitric oxide-independent vascular relaxation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:719–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., ERLINGE D., HOGESTATT E.D., ZYGMUNT P.M. Endothelial P2Y receptors induce hyperpolarisation of vascular smooth muscle by release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999c;364:169–173. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMSJO M., HOU M., HARDEN T.K., PENDERGAST W., PANTEV E., EDVINSSON L., ERLINGE D. Characterization of contractile P2 receptors in human coronary arteries by use of the stable pyrimidines uridine 5′-O-thiodiphosphate and uridine 5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000b;293:755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLAS R.A., WATT W.C., LAZAROWSKI E.R., LI Q., HARDEN K. Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective, and an ATP- and UTP-specific receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NILSSON T., HRAFNKELSDOTTIR T., EDVINSSON L., JERN S., ERLINGE D., WALL U. Forearm blood flow responses to neuropeptide Y, noradrenaline and adenosine 5′-triphosphate in hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Blood Press. 2000;9:126–131. doi: 10.1080/080370500453465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORENBERG W., ILLES P. Neuronal P2X receptors: localisation and functional properties. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:324–339. doi: 10.1007/s002100000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIROTTON S., COMMUNI D., MOTTE S., JANSSENS R., BOEYNAEMS J.M. Endothelial P2-purinoceptors: subtypes and signal transduction. J. Auton. Pharmacol. 1996;16:353–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY F.R., HUANG W., SLATER M., BARDEN J.A. Purinergic receptor distribution in endothelial cells in blood vessels: a basis for selection of coronary artery grafts. Atherosclerosis. 2002;162:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUMP L.C., OBERHAUSER V., von KUGELGEN I. Purinoceptors mediate renal vasodilation by nitric oxide dependent and independent mechanisms. Kidney Int. 1998;54:473–481. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATTERWHITE C.M., FARRELLY A.M., BRADLEY M.E. Chemotactic, mitogenic, and angiogenic actions of UTP on vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:H1091–H1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARGAS F., OSUNA A., FERNANDEZ-RIVAS A. Vascular reactivity and flow – pressure curve in isolated kidneys from rats with N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester-induced hypertension. J. Hypertens. 1996;14:373–379. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199603000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIANA F., DE SMEDT H., DROOGMANS G., NILIUS B. Calcium signalling through nucleotide receptor P2Y2 in cultured human vascular endothelium. Cell Calcium. 1998;24:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von ALBERTINI M., PALMETSHOFER A., KACZMAREK E., KOZIAK K., STROKA D., GREY S.T., STUHLMEIER K.M., ROBSON S.C. Extracellular ATP and ADP activate transcription factor NF-kappa B and induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;248:822–829. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von KUGELGEN I., WETTER A. Molecular pharmacology of P2Y-receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:310–323. doi: 10.1007/s002100000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG L., KARLSSON L., MOSES S., HULTGARDH-NILSSON A., ANDERSSON M., BORNA C., GUDBJARTSSON T., JERN S., ERLINGE D. P2 receptor expression profiles in human vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2002;40:841–853. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO K., KORENAGA R., KAMIYA A., ANDO J. Fluid shear stress activates Ca(2+) influx into human endothelial cells via P2X4 purinoceptors. Circ. Res. 2000a;87:385–391. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO K., KORENAGA R., KAMIYA A., QI Z., SOKABE M., ANDO J. P2X(4) receptors mediate ATP-induced calcium influx in human vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000b;279:H285–H292. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT P., GRUNDEMAR L., HOGESTATT E.D. Endothelium-dependent relaxation resistant to N omega-nitro-L-arginine in the rat hepatic. Acta Physiol Scand. 1994;152:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1994.tb09789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT P.M., HOGESTATT E.D. Role of potassium channels in endothelium-dependent relaxation resistant to nitroarginine in the rat hepatic artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1600–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT P.M., PLANE F., PAULSSON M., GARLAND C.J., HOGESTATT E.D. Interactions between endothelium-derived relaxing factors in the rat hepatic artery: focus on regulation of EDHF. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]