Abstract

Mechanisms of methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (methyl paraben) action in allergic reactions were investigated by measuring the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and histamine release in rat peritoneal mast cells (RPMCs).

In the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+, methyl paraben (0.1–10 mM) increased [Ca2+]i, in a concentration-dependent manner. Under both the conditions, methyl paraben alone did not evoke histamine release.

In RPMCs pretreated with a protein kinase C (PKC) activator (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) 3 and 10 nM), methyl paraben (0.3–3 mM) induced histamine release. However, a high concentration (10 mM) of the agent did not increase the histamine release.

U73122 (0.1 and 0.5 μM), an inhibitor of phospholipase C (PLC), significantly inhibited the methyl paraben-induced histamine release in PMA-pretreated RPMCs. U73343 (0.5 μM), an inactive analogue of U73122, did not inhibit the histamine release caused by methyl paraben.

In Ca2+-free solution, PLC inhibitors (U73122 0.1 and 0.5 μM, D609 1–10 μM) inhibited the methyl paraben-induced increase in [Ca2+]i, whereas U73343 (0.5 μM) did not.

Xestospongin C (2–20 μM) and 2 aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (30 and 100 μM), blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor, inhibited the methyl paraben-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in Ca2+-free solution.

In conclusion, methyl paraben causes an increase in [Ca2+]i, which may be due to release of Ca2+ from storage sites by IP3 via activation of PLC in RPMCs. In addition, methyl paraben possibly has some inhibitory effects on histamine release via unknown mechanisms.

Keywords: Methyl p-hydroxybenzoate; mast cells; intracellular calcium concentration; histamine release; phospholipase C; protein kinase C; inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

Introduction

There have been numerous reports on cases of anaphylactic reactions caused by various drugs (Fisher & More, 1981; Mertes & Laxenaire, 2002). Anaphylactic shock is the type I allergy reaction mediated by IgE antibodies and mast cells. The symptom similar to anaphylactic shock is called an anaphylactoid reaction (Fisher & Pennington, 1982), where the mechanism involves activation of mast cells without IgE antibodies (Stellato & Marone, 1995). A preservative, methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (methyl paraben), may be responsible for some cases of anaphylactic shock and anaphylactoid reactions caused by various commercially available medicines (Nagel et al., 1977; Wildsmith et al., 1998). Methyl paraben is nonstimulating and nontoxic, and has a broad antibiotic spectrum. The compound is widely used as a preservative for foods, cosmetics and medicines. Those methyl paraben-containing products caused contact dermatitis and drug hypersensitivity (Larson, 1977; Mowad, 2000), but there has been no fundamental study on allergic reactions related to methyl paraben.

In an immunological mechanism, degranulation of mast cells is triggered off by the aggregation of high-affinity receptor for the Fc region of IgE (FcɛRI) caused by crosslinking of IgE by polyvalent antigens. However, specific IgE antibodies for methyl paraben have not been identified (Kokubu et al., 1989). Simple chemicals such as methyl paraben are incapable of producing sensitization and induction of immediate or delayed hypersensitivity without prior conjugation to carrier molecules, usually proteins. The bound methyl paraben is then considered a hapten, whereas its chemical properties are not clear (Soni et al., 2002).

It was reported that methyl paraben activated the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channel in skeletal muscle terminal cisternae (Cavagna et al., 2000). On the other hand, Teraoka et al. (1997) reported that caffeine, an activator of the ryanodine receptor, did not increase the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in rat peritoneal mast cells, and Soboloff & Berger (2002) described that ryanodine did not significantly increase [Ca2+]i in bone marrow-derived mast cells. However, the lack of stimulatory effects of caffeine and ryanodine on Ca2+ release does not accordingly indicate the absence of ryanodine receptor in many types of nonexcitable cells (Hosoi et al., 2001). The existence of ryanodine receptor is still under controversy, raising the question as to how methyl paraben affects the intracellular events during the allergic reactions.

In the present study, in order to clarify the mechanism of allergic reactions caused by methyl paraben, we investigated the effects of the agent on the changes in [Ca2+]i and histamine release in RPMCs.

Methods

Mast cell isolation and purification

Male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 400–800 g were anaesthetized with diethyl ether, and then killed by bleeding from the carotid arteries. Rat peritoneal mast cells were isolated and purified over Percoll density gradient as previously described (Chan et al., 2000). The peritoneal cavity was injected with the physiological salt solution (PSS) containing BSA (0.3 mg ml−1). After gentle massage of the rat abdominal region, mixed peritoneal cells (30–35 ml of fluid) were obtained by peritoneal lavage. The mixed peritoneal cells were then washed twice by centrifugation (1100 r.p.m., 5 min, 4°C) and were resuspended in 1 ml of PSS. The cell suspension was then mixed with 2 ml of 33% Percoll. BSA-supplemented PSS (1 ml) was then carefully layered over the Percoll-cell mixture. Purification was then performed by centrifugation (3000 r.p.m., 20 min, 4°C), which allowed cell separation and gradient formation. Harvesting of the mast cells posed no problem since these cells gathered in a layer at the bottom of the tube, whereas other cells formed a rather compact layer on top of the gradient and could easily be removed by aspiration. The cell fraction was then washed twice in PSS by centrifugation and finally resuspended to the desired cell density in PSS.

Intracellular calcium measurements

Intracellular Ca2+ images were obtained with the confocal laser scanning microscope (IX70, Olympus). Cells were incubated in PSS containing the acetoxymethyl ester of fluo-3 (fluo-3 AM 5 μM) for 30 min at room temperature (22–25°C). Cells attached to a glass coverslip were mounted on the bottom of a chamber of 500 μl capacity and placed in the microscope for fluorescence measurements. Cells were excited at 488 nm with an argon laser beam through the objective lens (UplanApo40X, Olympus). Fluo-3 fluorescent images (emission 530 nm) were collected with the scan unit (FVX-SU, Olympus) every 0.42 s. To estimate [Ca2+]i, the mean intensity of cell area except nucleus was calculated with the analysing software (FLUOVIEW FV500, Olympus). The data were expressed as ratios of fluorescence intensity changes (F) relative to control values before stimulation (F0), namely (F-F0) F0−1.

Histamine measurements

Drugs were applied to cell suspensions (106 cells ml−1), making a total of 1 ml solution. The histamine-releasing reactions were terminated by placing the test tube in ice-cold water for 10 min. Cell suspensions were then centrifuged and divided into fractions of supernatant (0.5 ml) and supernatant plus pellets (0.5 ml), both of which were acidified with perchloric acid (50 μl) to abolish histamine breakdown. After both fractions were centrifuged at 1100 r.p.m. for 10 min at 4°C to remove proteins, secreted histamine was determined by the fluorometric method. Histamine release was expressed as a percentage of the total cell contents. All samples were stored at –25°C until the histamine level was measured using the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) postlabel system as previously described (Yamatodani et al., 1985; Horinouchi et al., 1993). The system was composed of an intelligent pump (Hitachi, L-6200), a reaction pump (Hitachi, 655-A-13), a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, F-1150), an autosampler (Hitachi, AS-4000), a Chromato-integrator (Hitachi, D-2500) and a 6 ∅, 15 cm column (Catecholepak, Toyosoda, Tokyo, Japan) warmed at 50°C by a column oven (Hitachi, L-5020). Each 100 μl of supernatant was injected into the HPLC for each sample. The excitation wavelength used was 340 nm and the emission was 450 nm.

Chemicals

The drugs used were BSA, EGTA, methyl paraben, HEPES, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), compound 48/80, U73343 and U73122 (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, U.S.A.), dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), A23187, 2APB, xestospongin C and D609 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), Fluo-3 AM (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) and Percoll (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden).

Solutions

The PSS contained (in mM): NaCl 138.6, KCl 5.0, MgCl2 1.5, CaCl2 2.0, HEPES 10, glucose 5.6, KH2PO4 1.0, pH 7.2. Ca2+-free solution was made by substituting an equimolar concentration of MgCl2 instead of CaCl2 and adding 0.5 mM EGTA.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean±s.e.m. and statistical significance was determined using the paired or unpaired Student's t-test. Probabilities less than 5% (P<0.05) were considered significant.

Results

Methyl paraben-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in the presence or absence of external Ca2+

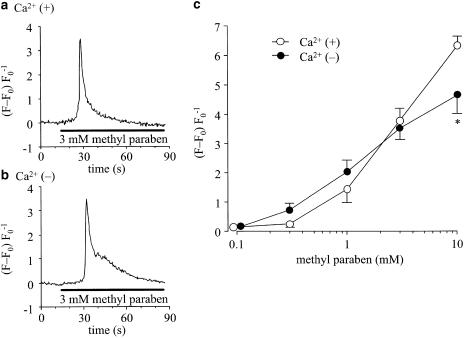

Figure 1a and b shows representative traces of the effects of methyl paraben (3 mM) on [Ca2+]i in rat peritoneal mast cells (RPMCs). Methyl paraben was applied for 75 s. The agent produced a transient increase in [Ca2+]i both in Ca2+-containing solution (PSS, 1a) and in Ca2+-free solution (1b). Figure 1c shows the average of the peak values of the changes in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben (0.1–10 mM). The [Ca2+]i was increased concentration-dependently in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. A similar result was obtained also in the Ca2+-free solution. At a high concentration (10 mM), however, the increase was significantly greater in the Ca2+-containing solution.

Figure 1.

Effects of methyl paraben on [Ca2+]i in RPMCs. The fluo-3 AM-loaded RPMCs were stimulated with methyl paraben for 75 s at room temperature (22–25°C). (a) Methyl paraben (3 mM) increased the [Ca2+]i in an RPMC incubated in PSS containing 2 mM Ca2+. (b) Methyl paraben was applied in Ca2+-free solution containing 0.5 mM EGTA after a 5 min removal of Ca2+. Also in Ca2+-free condition, methyl paraben increased the [Ca2+]i in an RPMC. (c) The Concentration–response relation of methyl paraben-induced [Ca 2+]i increase in Ca2+-containing (open circles) and Ca2+-free (filled circles) mediums. The ordinate shows the net maximum [Ca2+]i of the response with baseline subtracted. The data points indicate mean±s.e.m. of 20 experiments. The asterisk shows a significant difference in Ca2+-containing and Ca2+-free solutions.

Methyl paraben did not evoke histamine release from RPMCs

The amount of histamine release was measured as an index of the degranulation of RPMCs and illustrated in Figure 2. The basal spontaneous release was around 10% of the total contents in RPMCs (control). Compound 48/80 (0.3 μg ml−1) potentiated the histamine release both in PSS and in Ca2+-free solution, increasing it up to 63.9±5.2% (n=4) and 34.6±1.9% (n=4), respectively. A combination of a Ca2+ ionophore (A23187 0.1 μM) and the phorbol ester (PMA 10 nM) caused the release of histamine in PSS (40.9±1.2%, n=5). In contrast, methyl paraben did not increase histamine release in PSS (4.32±0.58%, n=4, by 3 mM and 9.84±1.70%, n=4, by 10 mM). It was also the case in Ca2+-free solution (6.49±0.91%, n=4, by 3 mM and 8.92±1.18%, n=4, by 10 mM).

Figure 2.

Effects of methyl paraben (3 and 10 mM) and various stimuli on histamine release from RPMCs. Cells were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C and subsequently incubated with methyl paraben (3 and 10 mM), compound 48/80 (0.3 μg ml−1) or a combination of A23187 (0.1 μM) and PMA (10 nM) for 30 min in the external solution with (open columns) or without (closed columns) Ca2+. The released histamine in the 30 min period was calculated as a percentage of the total histamine content of the cells. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of eight to 10 experiments.

Methyl paraben-evoked histamine release from PMA-pretreated RPMCs

Incapability of methyl paraben to release histamine in the present study may be due to insufficient activation of protein kinase C (PKC), since it has been reported that both increase in [Ca2+]i and activation of PKC are needed for the release (Beaven & Cunha-Melo, 1988). We, therefore, pretreated RPMCs with PMA for 5 min to activate PKC. The spontaneous histamine release was normalized as a relative histamine release of 1.0. Application of methyl paraben alone at 0.3–10 mM did not induce histamine release (open circles). In the absence of methyl paraben (control), PMA at 3 nM (closed circles) and 10 nM (closed squares) increased the release to 1.17±0.30 (n=4) and 2.05±0.54 (n=4) fold, respectively. Pretreatment with PMA for 5 min greatly enhanced the histamine release evoked by methyl paraben (0.3–10 mM). The peak increase was 2.23±0.11 times the control increase in the presence of 3 nM PMA (n=4, 1 mM methyl paraben) and 1.53±0.53 times the control increase in the presence of 10 nM PMA (n=4, 3 mM methyl paraben). A high concentration (10 mM) of methyl paraben, however, did not augment or even suppressed the histamine release from the PMA-pretreated RPMCs. The 10 nM PMA-induced increase in histamine release was suppressed to 0.79±0.18 (n=4) of the control increase (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of combined application of methyl paraben and PMA on histamine release in PSS. Cells were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C in the external solution with Ca2+ and subsequently incubated without (open circles) or with PMA (3 nM, closed circles or 10 nM, closed squares) for 5 min. The cells were then stimulated with methyl paraben (3 mM) for 30 min in the continuous presence or absence of PMA. The spontaneous histamine release was used for normalization as a relative histamine release of 1.0. The symbols refer to the mean of four to 12 experiments and the error bars represent s.e.m.

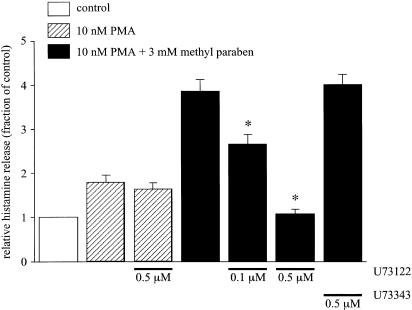

Effects of U73122 and U73343 on histamine release induced by combination of PMA and methyl paraben

To assess the involvement of phospholipase C (PLC) in the histamine release reaction by methyl paraben in the PMA-pretreated RPMCs, effects of a PLC inhibitor U73122 and its inactive analogue U73343 were examined. The spontaneous histamine release in PSS containing 2 mM Ca2+ was normalized as a relative histamine release of 1.0. A volume of 10 nM of PMA increased the release to 1.80±0.17 fold (n=12), and U73122 (0.5 μM) did not significantly inhibit the increase (n=12). The histamine release caused by methyl paraben (3 mM) applied 5 min after application of PMA (10 nM) was 3.86±0.28 times the control (n=5). U73122 significantly reduced this augmented histamine release by the combination of PMA and methyl paraben. The normalized inhibitory value by U73122 on the combination of PMA and methyl paraben-induced augmentation was 0.68±0.04 (n=5) and 0.10±0.02 (n=5) at 0.1 and 0.5 μM, respectively. In contrast, U73343 (0.5 μM) did not inhibit the histamine release caused by the combined application of PMA and methyl paraben (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of U73122 and U73343 on histamine release induced by a combination of PMA and methyl paraben. After preincubation for 5 min at 37°C in PSS, cells were pretreated with PMA (10 nM) or a combination of PMA and U73122 (0.1 and 0.5 μM) or U73343 (0.5 μM) for 5 min. The cells were then stimulated with methyl paraben (closed columns) or not (hatched columns) and incubated for 30 min in PSS with continued treatment of PMA in the continuous presence or absence of U73122 or U73343. The spontaneous histamine release was used for normalization as a relative histamine release of 1.0 (open column). Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of five to 12 experiments. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the combined application of PMA and methyl paraben in the absence of U73122 or U73343 with P<0.05.

Effects of U73122, U73343 and D609 on increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben

We investigated the effects of U73122, U73343 and another PLC inhibitor D609 to confirm that the increase in [Ca2+]i caused by methyl paraben was induced through activation of PLC in RPMCs. The change in [Ca2+]i caused by 3 mM of methyl paraben in the Ca2+-free solution containing 0.5 mM EGTA was used as a control (Figure 5a). Pretreatment with U73122 (0.5 μM) for 5 min markedly inhibited the [Ca2+]i increase, while U73343 (0.5 μM) did not (Figure 5b). D609 at 10 μM completely suppressed the increase (Figure 5c). Figure 5d illustrates the effects of U73312 (0.1 and 0.5 μM), U73343 (0.5 μM) and D609 (1–10 μM) on the peak increase in [Ca2+]i caused by 3 mM of methyl paraben. U73122 (0.1 and 0.5 μM) and D609 (1–10 μM) inhibited the increases in [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the inactive analogue (U73343 0.5 μM) did not.

Figure 5.

Effects of U73122, U73343 and D609 on the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben in Ca2+-free solution containing 0.5 mM EGTA. Methyl paraben (3 mM) was applied for 60–75 s following a 5 min incubation in the Ca2+-free solution. (a) Methyl paraben increased the [Ca2+]i in a fluo-3 AM-loaded RPMC. (b) Pretreatment good for 5 min with U73122 (0.5 μM) markedly suppressed the increase, while U73343 (0.5 μM) had no effects. (c) Pretreatment for 5 min with D609 (10 μM) completely blocked the effect of methyl paraben. (d) Each column indicates the average of the peak increase above the base line (n=8–10). U73122 and D609 suppressed the [Ca2+]i increase dose-dependently. The reduction by U73343 was not significant. Bars indicate s.e.m. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the control with P<0.05.

Effects of xestospongin C and 2APB on increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben

PLC increases the cytosolic levels of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and DAG in mast cells (White et al., 1985). IP3 stimulates release of Ca2+ from internal stores (Meyer et al., 1988; Berridge, 1993) and DAG is known to activate PKC (Nishizuka, 1984). We investigated the effects of xestospongin C and 2 aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB), inhibitors of IP3-induced Ca2+ release, on the methyl paraben-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in RPMCs. Figure 6a depicts a control increase in the [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben (3 mM) in the Ca2+-free solution containing 0.5 mM EGTA. Pretreatment with xestospongin C (6 and 20 μM; Figure 6b) or 2APB (100 μM; Figure 6c) markedly inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i. Effects of the IP3 inhibitors on the peak increase in [Ca2+]i are shown in Figure 6d. Xestospongin C (2–20 μM) and 2APB (30 and 100 μM) suppressed the increases in [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

Effects of xestospongin C and 2APB on the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben in Ca2+-free solution containing 0.5 mM EGTA. Methyl paraben (3 mM) was applied for 70–75 s in Ca2+-free solution after a 5 min removal of Ca2+. (a) Methyl paraben increased the [Ca2+]i in a fluo-3 AM-loaded RPMC. (b) Pretreatment for 5 min with xestospongin C (6 or 20 μM) markedly suppressed the [Ca2+]i increase. (c) Pretreatment for 5 min with 2APB (100 μM) greatly decreased the [Ca2+]i increase. (d) Each column indicates the average of the peak increase above the base line (n=7–10). Xestospongin C and 2APB dose-dependently suppressed the [Ca2+]i increase produced by methyl paraben. Bars indicate s.e.m. Asterisks show significant suppression from the control with P<0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of methyl paraben on the changes in [Ca2+]i and histamine release in RPMCs. Methyl paraben at 1–10 mM dose-dependently increased [Ca2+]i in both Ca2+-containing and Ca2+-free solutions. The peak increase in [Ca2+]i induced by 0.3–3 mM of methyl paraben was not significantly different between the presence and absence of the external Ca2+. This finding suggests that the transient increase in [Ca2+]i by the agent was largely due to release of Ca2+ from intracellular storage sites. At a high concentration (10 mM), however, the peak increase was significantly greater in the Ca2+-containing solution. High concentrations of methyl paraben may induce Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium (Figure 1).

Many reports have demonstrated that Ca2+ chelators such as EGTA increase [Ca2+]i in mast cells, although the reason is not known (Teraoka et al., 1997). In the present experiments too, EGTA caused an increase in [Ca2+]i in some of the mast cells. However, this reaction was observed only within 5 min of the exposure to EGTA (data not shown). Hence, measurements were made 5 min after replacement of PSS with Ca2+-free solution, and cells showing no change in [Ca2+]i were selected for the following experiments. Actually, changes in [Ca2+]i were negligible probably due to the low concentration of EGTA (0.5 mM) in this study.

Application of the stimulants known to release histamine from mast cells, such as compound 48/80, known as an activator of PLC (Cockcroft & Gomperts, 1979), and the combination of A23187 and PMA (Chew et al., 2002), released histamine in our experimental system, but methyl paraben at 0.3–10 mM did not induce histamine release (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Dvorak et al. (1996) demonstrated that the interaction between inositol phospholipids and PKC regulated degranulation of mast cells. In addition, Akita et al. (1990) reported that Ca2+ played an important role in the binding of PKC to the cell membrane. Furthermore, it was suggested that PKC was activated by increased [Ca2+]i and phospholipids, and that the activation was further enhanced by DAG (White et al., 1985). Thus, the increase in [Ca2+]i and the activation of PKC, which may lead to degranulation, are required to release histamine (Heiman & Crews, 1985a,1985b). Application of methyl paraben alone did not induce histamine release in the present experiments, but after activation of PKC by PMA, the agent evoked histamine release, which might be mediated by the activated PKC and the Ca2+ mobilized by methyl paraben. The increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben was dose-dependent (Figure 1), while the release of histamine by the combined application of PMA and methyl paraben was not dose-dependent but inhibited at the higher concentration (10 mM) (Figure 3). These results suggest that methyl paraben not only mobilizes Ca2+ but also inhibits the histamine release via some unknown mechanisms.

The PLC inhibitors, U73122 (Bleasdale et al., 1990) and D609 (Ito et al., 2002), inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i caused by methyl paraben. U73122 also inhibited the histamine release induced by the combined application of PMA and methyl paraben. In contrast, U73343, an inactive analogue of U73122 (Pocock & Bates, 2001), did not show any effects on these reactions. In addition, U73122 did not significantly suppress the histamine release caused by PMA (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Thus the PLC inhibitors suppressed the action of methyl paraben, indicating that methyl paraben causes the increase in [Ca2+]i via activation of PLC. When PLC is activated in mast cells, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is hydrolysed to produce IP3 and DAG. IP3 binds to its receptors on the intracellular Ca2+ storage site to release Ca2+ (Meyer et al., 1988; Berridge, 1993), while DAG activates PKC (White & Metzger, 1988). IP3 receptor blockers, xestospongin C (Gafni et al., 1997) and 2APB (Maruyama et al., 1997), inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by methyl paraben (Figure 6), suggesting that methyl paraben produced IP3 through PLC activation, which resulted in a release of Ca2+ from the intracellular storage sites in RPMCs. 4-Chloro-m-cresol (0.5 and 1 mM), a potent activator of the ryanodine receptor (Zorzato et al., 1993), induced the transient increase in [Ca2+]i; however, additional application of any stimulants such as compound 48/80, methyl paraben or A23187 had no effect on [Ca2+]i in RPMCs (data not shown). These results suggest the colocalization of ryanodine receptor and IP3 receptor in Ca2+ store. Although the effect of methyl paraben on the ryanodine receptor in RPMCs is still unclear, PLC inhibitors and IP3 receptor blockers almost completely suppressed the action of methyl paraben (Figures 4,5,6), indicating that IP3 is a key messenger on Ca2+ release and subsequent histamine release induced by methyl paraben in RPMCs. DAG produced by PLC activation is expected to activate PKC and to evoke degranulation by acting together with mobilized Ca2+. However, no histamine release was observed by methyl paraben alone in the present study (Figure 2 and Figure 3). In addition, methyl paraben released histamine from the mast cells in which PKC had been activated by PMA (Figure 3). These arguments suggest that although methyl paraben activates PLC, the PKC activity is not enough to release histamine in RPMCs.

Methyl paraben is contained in various pharmaceutical agents at certain concentrations: 0.06–0.25% in injections; 0.015–0.2% in syrups; 0.015–0.05% in instillations; and 0.02–0.3% in external medicines (Anonymous, 1998). In addition, methyl paraben is added to cosmetics at 0.32% at maximum (Rastogi et al., 1995), and to food at 0.03–0.07% in combination with propyl paraben (Krebs-Smith et al., 1997). In this study, methyl paraben showed a significant effect on the [Ca2+]i increase and histamine release at the concentrations of 1–3 mM, which correspond to approximately 0.015–0.046%. Therefore, some agents containing methyl paraben may induce an increase in [Ca2+]i when directly acting on mast cells.

The molecular weight of methyl paraben is as small as 152.14, and hence it has been thought that the agent by itself does not have antigenicity and may become antigenic when bound to a certain kind of proteins (Pressman et al., 1968). In the present experiments, methyl paraben might act on mast cells with no relation to FcɛRI on account of the absence of specific IgE and proteins to bind. In vivo, however, the situation would be different from in vitro, and it is likely that methyl paraben specific IgE may mediate the activation of Ca2+ release and subsequent histamine release in mast cells. In addition, it is not clear whether methyl paraben bound to proteins has an inhibitory action on histamine release; therefore, the usual view that methyl paraben induces allergic reactions through an immunological mechanism is not excluded. On the other hand, the present results propose the possibility that methyl paraben may cause anaphylactoid reactions through a nonimmunological mechanism when PKC is simultaneously activated to some extent in the mast cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Y. Ito (Department of Pharmacology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University) for his advice.

Abbreviations

- 2APB

2 aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- RPMCs

rat peritoneal mast cells

References

- AKITA M., SASAKI S., MATSUYAMA S., MIZUSHIMA S. SecA interacts with secretory proteins by recognizing the positive charge at the amino terminus of the signal peptide in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:8164–8169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Preservation, sterilization and stability testing of ophthalmic preparations. Int. J. Pharm. Compounding. 1998;2:192–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAVEN M.A., CUNHA-MELO J.R. Membrane phosphoinositide-activated signals in mast cells and basophils. Prog. Allergy. 1988;42:123–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRIDGE M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLEASDALE J.E., THAKUR N.R., GREMBAN R.S., BUNDY G.L., FITZPATRICK F.A., SMITH R.J., BUNTING S. Selective inhibition of receptor-coupled phospholipase C-dependent processes in human platelets and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:756–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAVAGNA D., ZORZATO F., BABINI E., PRESTIPINO G., TREVES S. Methyl p-hydroxybenzoate (E-218) a preservative for drugs and food is an activator of the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channel. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:335–341. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN C.L., JONES R.L., LAU H.Y. Characterization of prostanoid receptors mediating inhibition of histamine release from anti-IgE-activated rat peritoneal mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:589–597. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEW C.S., CHEN X., PARENTE J.A., Jr, TARRER S., OKAMOTO C., QIN H.Y. Lasp-1 binds to non-muscle F-actin in vitro and is localized within multiple sites of dynamic actin assembly in vivo. J. Cell. Sci. 2002;115:4787–4799. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKCROFT S., GOMPERTS B.D. Evidence for a role of phosphatidylinositol turnover in stimulus-secretion coupling. Biochem. J. 1979;178:681–687. doi: 10.1042/bj1780681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DVORAK A.M., ACKERMAN S.J., LETOURNEAU L., MORGAN E.S., LICHTENSTEIN L.M., MACGLASHAN D.W., Jr Vesicular transport of Charcot–Leyden crystal protein in tumor-promoting phorbol diester-stimulated human basophils. Lab. Invest. 1996;74:967–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER M.M., MORE D.G. The epidemiology and clinical features of anaphylactic reactions in anaesthesia. Anaesth. Intens. Care. 1981;9:226–234. doi: 10.1177/0310057X8100900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER M.M., PENNINGTON J.C. Allergy to local anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 1982;54:893–894. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAFNI J., MUNSCH J.A., LAM T.H., CATLIN M.C., COSTA L.G., MOLINSKI T.F., PESSACH I.N. Xestospongins: potent membrane permeable blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron. 1997;19:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIMAN A.S., CREWS F.T. Characterization of the effects of phorbol esters on rat mast cell secretion. J. Immunol. 1985a;134:548–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIMAN A.S., CREWS F.T. Hydrocortisone inhibits phorbol ester stimulated release of histamine and arachidonic acid from rat mast cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985b;130:640–645. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORINOUCHI Y., ABE K., KUBO K., OKA M. Mechanisms of vancomycin-induced histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells. Agents Actions. 1993;40:28–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01976748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOSOI E., NISHIZAKI C., GALLAGHER K.L., WYRE H.W., MATSUO Y., SEI Y. Expression of the ryanodine receptor isoforms in immune cells. J. Immunol. 2001;167:4887–4894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO J., NAGAYASU Y, UENO S., YOKOYAMA S. Apolipoprotein-mediated cellular lipid release requires replenishment of sphingomyelin in a phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44709–44714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOKUBU M., ODA K., SHINYA N. Detection of serum IgE antibody specific for local anesthetics and methyl paraben. Anesth. Prog. 1989;36:186–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREBS-SMITH S.M., GUENTHER P.M., COOK A., THOMPSON F.E., CUCINELLI J., UDLER J.Foods commonly eaten in the United States: quantities consumed per eating occasion and in a day, 1989–91 1997. NTISPB 98-111719

- LARSON C.E. Methyl paraben–an overlooked cause of local anesthetic hypersensitivity. Anesth. Prog. 1977;24:72–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARUYAMA T., KANAJI T., NAKADE S., KANNO T., MIKOSHIBA K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of ins (1,4,5) P3 -induced Ca2+ release. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1997;122:498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERTES P.M., LAXENAIRE M.C. Allergic reactions occurring during anaesthesia. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2002;19:240–262. doi: 10.1017/s0265021502000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER T., HOLOWKA D., STRYER L. Highly cooperative opening of calcium channels by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Science. 1988;240:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.2452482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOWAD C.M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by parabens: 2 case reports and a review. Am. J. Contact Dermatol. 2000;11:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s1046-199x(00)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGEL J.E., FUSCALDO J.T., FIREMAN P. Paraben allergy. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1977;237:1594–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. The role of protein kinase C in cell surface signal transduction and tumour promotion. Nature. 1984;308:693–698. doi: 10.1038/308693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POCOCK T.M., BATES D.O. In vivo mechanisms of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated increased hydraulic conductivity of Rana capillaries. J. Physiol. 2001;534:479–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRESSMAN D., SIEGEL M., HALL LAR. The closeness of fit of antibenzoate about haptens and the orientation of the haptens in combination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;76:6336–6342. [Google Scholar]

- RASTOGI S.C., SCHOUTEN A., DE KRUIJF N., WEIJLAND J.W. Contents of methyl-, ethyl-, propyl-, butyl- and benzylparaben in cosmetic products. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:28–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOBOLOFF J., BERGER S.A. Sustained ER Ca2+ depletion suppresses protein synthesis and induces activation-enhanced cell death in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13812–13820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONI M.G., TAYLOR S.L., GREENBERG N.A., BURDOCK G.A. Evaluation of the health aspects of methyl paraben: a review of the published literature. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:1335–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STELLATO C., MARONE G. Mast cells and basophils in adverse reactions to drugs used during general anesthesia. Human basophils and mast cells: clinical aspects. Chem. Immunol. 1995;62:108–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERAOKA H., AKIBA H., TAKAKI R., TANEIKE T., HIRAGA T., OHGA A. Inhibitory effects of caffeine on influx and histamine secretion independent of CAMP in rat peritoneal mast cells. Gen. Pharmac. 1997;28:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE J.R., PLUZNIK D.H., ISHIZAKA K., ISHIZAKA T. Antigen-induced increase in protein kinase C activity in plasma membrane of mast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:8193–8197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE K.N., METZGER H. Translocation of protein kinase C in rat basophilic leukemic cells induced by phorbol ester or by aggregation of IgE receptors. J. Immunol. 1988;141:942–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILDSMITH J.A., MASON A., MCKINNON R.P., RAE S.M. Alleged allergy to local anaesthetic drugs. Br. Dent. J. 1998;184:507–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMATODANI A., FUKUDA H., WADA H., IWAEDA T., WARANABE T. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of plasma and brain histamine without previous purification of biological samples: cation-exchange chromatography coupled with postcolumn derivatization fluorometry. J. Chromatogr. 1985;344:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZORZATO F., SCUTARI E., TEGAZZIN V., CLEMENTI E., TREVES S. Chlorocresol: an activator of ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ release. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:1192–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]