Abstract

The functional activity of the peptidic neuromedin B receptor antagonist BIM-23127 was investigated at recombinant and native urotensin-II receptors (UT receptors). Human urotensin-II (hU-II) promoted intracellular calcium mobilization in HEK293 cells expressing the human UT (hUT) or rat UT (rUT) receptors with pEC50 values of 9.80±0.34 (n=6) and 9.06±0.32 (n=4), respectively. While BIM-23127 alone had no effect on calcium responses in either cell line, it was a potent and competitive antagonist at both hUT (pA2=7.54±0.14; n=3) and rUT (pA2=7.70±0.05; n=3) receptors. Furthermore, BIM-23127 reversed hU-II-induced contractile tone in the rat-isolated aorta with a pIC50 of 6.66±0.04 (n=4). In conclusion, BIM- 23127 is the first hUT receptor antagonist identified to date and should not be considered as a selective neuromedin B receptor antagonist.

Keywords: Urotensin-II, UT receptor, BIM-23127, GPR14, neuromedin B

Introduction

Urotensin-II (U-II) is a cyclic peptide first identified in the goby urophysis, an endocrine organ homologous in structure to the mammalian hypothalamoneurohypophysial axis (Pearson et al., 1980). Following the cloning of carp U-II cDNAs (Ohsako et al., 1986), U-II orthologues have since been cloned from additional vertebrates, including humans (Ames et al., 1999; Coulouarn et al., 1998). Human urotensin-II (hU-II) is a cyclic undecapeptide that has been identified as the endogenous ligand for the orphan G protein-coupled receptor, GPR14 (Ames et al., 1999), subsequently redesignated the urotensin-II receptor (UT receptor) by the IUPHAR Committee on Receptor Nomenclature (Douglas & Ohlstein, 2000b).

Both hU-II and the human UT (hUT) receptor are expressed within several cardiovascular tissues (Ames et al., 1999; Douglas & Ohlstein, 2000a), suggesting that hU-II may be an endogenous modulator of cardiovascular function. Indeed, hU-II has been shown to exert potent contractile effects in isolated vascular tissues from numerous species (Douglas et al., 2000c; Paysant et al., 2001), promote inotropic and arrhythmogenic actions in human cardiac trabeculae (Russell et al., 2001), have synergistic effects with factors such as oxidized LDL on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (Watanabe et al., 2001), and promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Zou et al., 2001). In addition, elevated hU-II levels were observed in patients with hypertension (Matsushita et al., 2001) and congestive heart failure (Douglas et al., 2002). Thus, because evidence exists suggesting a role for hU-II as a cardiovascular mediator, the UT receptor represents a potential target in the treatment of cardiovascular disorders. To this end, the development of selective UT receptor antagonists will facilitate a better understanding of the role of U-II in the mammalian cardiovascular system. Therefore, the present study has examined the functional activity of the neuromedin B receptor antagonist BIM-23127 (D-Nal-cyclo-[Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Val-Cys]-2-Nal-NH2; Nal=β-2-Napthyl-L-alanine) at recombinant and native UT receptors. BIM-23127 is a D-amino-acid substituted cyclo-somatostatin octapeptide analog (Orbuch et al., 1993) that shares structural similarity with SB-710411, which functions as a competitive antagonist of the rat UT (rUT) receptor in the rat aorta (Behm et al., 2002) and a full agonist at the recombinant hUT receptor (Herold et al., 2001).

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293 cells stably expressing the hUT or rUT receptors were generated and propagated as described previously (Ames et al., 1999).

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+i) mobilization assay

hUT-HEK293 cells or rUT-HEK293 cells were seeded in blackwalled, clear-bottomed 96-well Biocoat plates (Beckton Dickinson, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.) at a density of 45, 000 cells/well, grown in the incubator at 37°C for 18–24 h, and prepared for Ca2+i measurements as described previously (Ames et al., 1999). Plates were placed into the Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.) where cells, loaded with Fluo 3 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.), were exposed to excitation (488 nm) from a 6-W argon laser. Fluorescence was monitored at 566 nm emission for all 96 wells simultaneously, and data were read every 1 s for 1 min and then every 3 s thereafter. Agonist was added after 10 s and concentration–response curves were obtained by calculating the maximal fluorescent counts above background after addition of each concentration of agonist. For antagonist studies, BIM-23127 (Bachem, King of Prussia, PA, U.S.A.) was added 10 min prior to the addition of hU-II (California Peptide Research, Inc., Napa, CA, U.S.A.). Concentration-response curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Preparation and utilization of rat isolated aortae

All procedures were performed in accredited facilities in accordance with institutional guidelines (Animal Care and Use Committee, GlaxoSmithKline) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (DHSS #NIH 85-23). Proximal descending thoracic aortae were isolated from male Sprague–Dawley rats (400 g) and prepared as described previously (Behm et al., 2002). Following a 60 min equilibration period, vessels were exposed to standard concentrations of KCl (60 mM) and phenylephrine (1 μM). Paired thoracic aortae were pretreated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or BIM-23127 (3 μM) for 30 min, following which cumulative concentration-response curves to hU-II (0.01–300 nM) were constructed.

For reversal of hU-II-induced tone experiments, separate vessels were contracted with 3 nM hU-II (predetermined EC80) and once the response plateaued, contractile tone was reversed by adding increasing log unit concentrations of BIM-23127. For all experiments, each tissue was used to generate only one concentration–response curve and each response was allowed to plateau before the addition of subsequent agonist concentration. All values are expressed as mean±s.e.m. and n represents the total number of animals from which the vessels were isolated. Where relevant, statistical comparisons were made using a paired, two-tailed t-test and differences were considered significant when P⩽0.05.

Competition binding assay

[125I]hU-II binding assays were performed using the scintillation proximity assay (SPA) method. Membranes from hUT and UT receptor-expressing HEK293 cells were prepared as described previously (Ames et al., 1999) and precoupled to wheatgerm–agglutinin-coated SPA beads (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.). Binding conditions (200 μl final volume) consisted of 10–20 μg membrane protein, 0.4 mg SPA beads, and 0.3 nM [125I]hU-II ([125I]Tyr10, 2000 Ci/mmol; Amersham) in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of unlabeled hU-II or BIM-23127 in assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.05% BSA). Non-specific binding was determined with 1 μM unlabeled hU-II. Assays were performed in 96-well Optiplates (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT, U.S.A.). Assay plates were sealed, shaken gently for 1 h at room temperature, centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min, and counted in a Packard Top Count Scintillation Counter. Competition binding curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 3.0 software.

Results

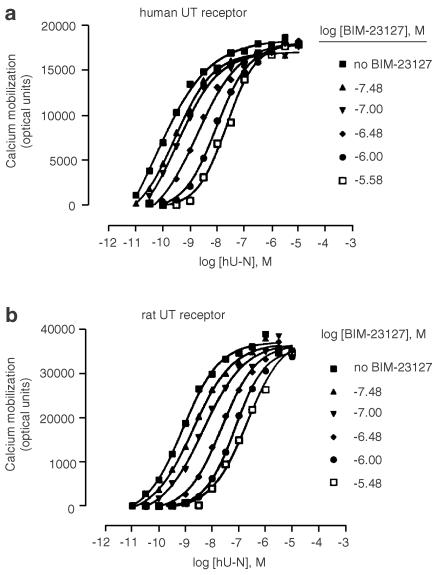

hU-II caused a dose-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i; in hUT-HEK293 cells (Figure 1a) and rUT-HEK293 cells (Figure 1b) with pEC50 values of 9.80±0.34 (n=6) and 9.06±0.32 (n=4), respectively. In both cell lines, in the presence of increasing concentrations of BIM-23127 (33 nM–3.3 μM), the hU-II concentration–response curves were shifted progressively to the right in a parallel manner with no changes in the maximum response to hU-II, suggesting competitive antagonism. Schild plots derived from these data could be fit by straight lines with slopes near unity (1.04±0.06; n=3 for the hUT receptor and 1.03±0.06; n=3 for the rUT receptor) and yielded pA2 values of 7.54±0.14 (n=3) and 7.70±0.05 (n=3) for the hUT receptor and rUT receptor, respectively. BIM-23127 alone (10 μM) did not have agonist properties in either cell line, whereas somatostatin-14 was 5000-fold less potent than hU-II as an agonist (data not shown). In addition, the nonpeptide neuromedin B receptor antagonist PD 168368 (10 μM) had no effect on the hU-II concentration–response curves (data not shown).

Figure 1.

BIM-23127 is a competitive antagonist at hUT and rUT receptors. The effect of BIM-23127 on hU-II-induced Ca2+i mobilization in HEK293 cells expressing either the hUT receptor (a) or the rUT receptor (b) was determined by generating hU-II concentration–response curves in the presence of vehicle increasing concentrations of BIM-23127. Data shown are the average Ca2+i mobilization results (expressed as optical units) of a representative experiment performed in triplicate. pA2 values reported in Results were derived from three separate experiments. Standard error bars were omitted for clarity but were typically <10% of the mean.

BIM-23127 also displayed high affinity for UT receptors in competition binding experiments. Using membranes from transfected HEK293 cells, BIM-23127 bound with pKis of 6.70±0.05, n=3 (vs 8.45±0.16, n=3 for hU-II) at the hUT receptor and 7.20±0.14, n=3 (vs 8.42±0.06, n=3 for hU-II) at the rUT receptor, whereas somatostatin-14 failed to compete for [125I]hU-II binding at concentrations up to 3 μM (data not shown).

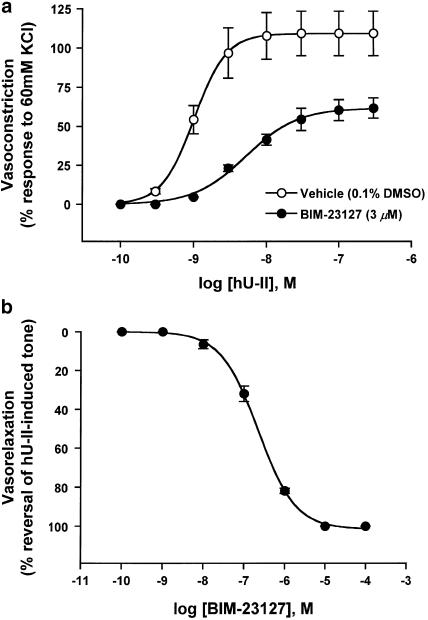

In the rat isolated aorta bioassay, hU-II evoked potent concentration–dependent contractions (Figure 2a) with a pEC50 of 8.98±0.03 (Emax of 109±14% response to 60 mM KCl; n=4). Exposure to 3 μM BIM-23127 produced a significant (∼40%; P<0.05) suppression of the maximum contractile response to hU-II (Emax of 62±7.0% response to 60 mM KCl; n=4) with a slight shift (∼five fold) in the concentration–response curve (pEC50=8.28±0.04). While an affinity value for BIM-23127 could not be determined in vitro because of the insurmountable antagonism, BIM-23127 potently (pIC50=6.66±0.04; n=4) and efficaciously (100% suppression) reversed contractile tone established in the rat isolated aorta with an EC80 dose of hU-II (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Antagonist effects of BIM-23127 in the rat isolated aorta. Concentration–response curves to hU-II were generated (a) in the absence (vehicle) or presence of 3 μM BIM- 23127. Concentration–dependent relaxation response curve to BIM-23127 (b) is expressed as percent reversal of the original tone established in endothelium-denuded aortae with 3 nM hU-II. Values shown in (a) and (b) are mean±s.e.m (n=4) and curves were derived by fitting experimental data to a logistic equation (Behm et al., 2002).

Discussion

hU-II has been shown to be a potent and efficacious spasmogen of mammalian isolated blood vessels and a mediator of additional cardiovascular functions (Douglas & Ohlstein, 2000a). Therefore, the development of novel UT receptor antagonists should be of utility in the management of cardiovascular pathologies such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure. To date, very few synthetic ligands have been reported for the UT receptor, thus hindering an understanding of the role of this ligand–receptor pair in cardiovascular homeostasis.

Owing to the striking sequence similarities between the neuromedin B receptor antagonist BIM-23127 and the UT receptor antagonist SB-710411, the ability of BIM-23127 to function as a UT receptor ligand was assessed. Interestingly, in Ca2+i mobilization assays, BIM-23127 was a potent and competitive antagonist at both hUT and rUT receptors. While BIM-23127 competed with [125I]hU-II for recombinant UT receptors with pKi values several fold less potent than the pKb values for the inhibition of hU-II-promoted Ca2+i mobilization, such differences between affinities for functional assays and binding assays have been observed with other UT receptor ligands (Kinney et al., 2002).

BIM-23127 also was an antagonist in vitro in the rat aorta bioassay where it dose dependently reversed hU-II-induced contractile tone with moderate potency. In addition, 3 μM BIM-23127 significantly suppressed the Emax for hU-II-promoted aortic ring contractions, suggesting non-competitive antagonism. While the mechanism responsible for this observation remains to be elucidated, its potency for reversing hU-II-induced contractile tone in the rat-isolated aorta is among the highest observed to date (Behm et al., 2002; Rossowski et al., 2002).

BIM-23127 did not display agonist activity at concentrations up to 10 μM in either the Ca2+i mobilization assay or the rat aorta bioassay, suggesting that this ligand has applications as a pure antagonist at both recombinant UT receptors and natively expressed UT receptors. In contrast, the residual agonist activity observed in the rat-isolated aorta with the novel UT receptor ligand [Orn8] hU-II described recently (Camarda et al., 2002) potentially limits the utility of [Orn8] hU-II as a UT receptor tool compound.

Given the potent effects of BIM-23127 at hUT and rUT receptors, these results indicate that BIM-23127 in fact is not a selective neuromedin B receptor antagonist as reported previously (Orbuch et al., 1993). Moreover, BIM-23127 displayed affinity values for competition binding at recombinant UT receptors and inhibition of hU-II-promoted Ca2+i mobilization in cells expressing hUT and rUT receptors that were roughly identical to those values determined for competition binding at neuromedin B receptors and for its ability to inhibit neuromedin B-promoted DNA synthesis (Lach et al., 1995). The nonpeptide neuromedin B receptor antagonist PD 168368 did not inhibit hU-II-induced Ca2+i mobilization, suggesting that the observed antagonism was because of the U-II-like structure of the ligand (hexapeptide cyclic core sequence) and is not a general property of neuromedin B receptor antagonists. In accord with these findings, it has become increasingly evident that a class of D-amino-acid substituted cyclo-somatostatin octapeptide analogs, which are structurally related to the cyclic U-II core sequence, display submicromolar to micromolar potency at UT receptors. For example, SB-710411 competitively antagonized hU-II-induced contractions in the rat aorta with a Kb of ∼500 nM (Behm et al., 2002) and was a full agonist at the hUT receptor expressed in HEK293 cells with an EC50 ∼100 nM (Herold et al., 2001). Similarly, the putative UT receptor antagonists PRL-2882, PRL-2903, and PRL-2915 were capable of blocking hU-II-induced rat aorta ring contractions (although the nature of antagonism was not discussed) and competed for [125I]U-II binding at recombinant hUT and rUT receptors (Rossowski et al., 2002). The data presented herein indicate that BIM-23127 is the most potent UT receptor ligand from this class of substituted somatostatin analogs; in fact, BIM-23127 represents the first example of an hUT receptor antagonist described to date. Whilst the identification of a nonpeptide hUT receptor antagonist of moderate potency (IC50=400 nM as determined by Ca2+i mobilization) was discussed recently (Flohr et al., 2002), no data were reported for this lead compound. In addition, BIM-23127 is the most potent antagonist of the recombinant rUT receptor yet reported.

In summary, while data generated with BIM-23127 should be interpreted cautiously because of its roughly equal affinity with the neuromedin B receptor (Lach et al., 1995), it nonetheless represents the most potent UT receptor antagonist characterized to date. Thus, BIM-23127 should find applications as an antagonist in vitro and in vivo for studying the actions of U-II and as a tool compound to examine recombinant UT receptor function from two species, human and rat. Furthermore, the D-amino-acid-substituted cyclo-somatostatin octapeptide analogs may serve as a template for the development of potent and selective UT receptor antagonists.

Abbreviations

- Ca2+i

intracellular calcium

- hU-II

human urotensin-II

- hUT receptor

human UT receptor

- rUT receptor

rat UT receptor

- U-II

urotensin-II

- UT receptor

urotensin-II receptor

References

- AMES R.S., SARAU H.M., CHAMBERS J.K., WILLETTE R.N., AIYAR N.V., ROMANIC A.M., LOUDEN C.S., FOLEY J.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., AO Z., DISA J., HOLMES S.D., STADEL J.M., MARTIN J.D., LIU W.S., GLOVER G.I., WILSON S., MCNULTY D.E., ELLIS C.E., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., SHABON U., TRILL J.J., HAY D.W.P., OHLSTEIN E.H., BERGSMA D.J., DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoconstrictor and agonist for the orphan receptor GPR14. Nature. 1999;401:282–286. doi: 10.1038/45809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEHM D.J., HEROLD C.L., OHLSTEIN E.H., KNIGHT S.D., DHANAK D., DOUGLAS S.A. Pharmacological characterization of SB-710411 (Cpa-c[D-Cys-Pal-D-Trp- Lys- Val-Cys]-Cpa-amide), a novel peptidic urotensin-II receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:449–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMARDA V., GUERRINI R., KOSTENIS E., RIZZI A., CALO G., HATTENBERGER A., ZUCCHINI M., SALVADORI S., REGOLI D. A new ligand for the urotensin II receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:311–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., LIHRMANN I., JEGOU S., ANOUAR Y., TOSTIVINT H., BEAUVILLAIN J.C., CONLON J.M., BERN H.A., VAUDRY H. Cloning of the cDNA encoding the urotensin II precursor in frog and human reveals intense expression of the urotensin II gene in motoneurons of the spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H. Human urotensin-II, the most potent mammalian vasoconstrictor identified to date, as a therapeutic target for the management of cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000a;10:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H.Urotensin receptors The IUPHAR Compendium of Receptor Characterization and Classification 2000bLondon: IUPHAR Media; 365–372.ed. Girdlestone, D. pp [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., SULPIZIO A.C., PIERCY V., SARAU H.M., AMES R.S., AIYAR N.V., OHLSTEIN E.H., WILLETTE R.N. Differential vasoconstrictor activity of human urotensin-II in vascular tissue isolated from the rat, mouse, dog, pig, marmoset and cynomolgus monkey. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000c;131:1262–1274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., TAYARA L., OHLSTEIN E.H., HALAWA N., GIAID A. Congestive heart failure and expression of myocardial urotensin II. Lancet. 2002;359:1990–1997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLOHR S., KURZ M., KOSTENIS E., BRKOVICH A., FOURNIER A., KLABUNDE T. Identification of nonpeptidic urotensin II receptor antagonists by virtual screening based on a pharmacophore model derived from structure–activity relationships and nuclear magnetic resonance studies on urotensin II. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:1799–1805. doi: 10.1021/jm0111043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEROLD C.L., BEHM D.J., AIYAR N.V., NASELSKY D.P., KNIGHT S.D., DHANAK D., DOUGLAS S.A. The somatostatin derivative, Cpa-c-[D-Cys-Pal-D-Trp-Lys-Val-Cys]-Cpa-amide, is an agonist at the human UT receptor but not the rat UT receptor in transfected HEK293 cells. Pharmacologist. 2001;43:189. [Google Scholar]

- KINNEY W.A., ALMOND H.R., QI J., SMITH C.E., SANTULLI R.J., DE GARAVILLA L., ANDRADE-GORDON P., CHO D.S., EVERSON A.M., FEINSTEIN M.A., LEUNG P.A., MARYANOFF B.E. Structure–function analysis of urotensin II and its use in the construction of a ligand-receptor working model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2940–2944. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<2940::AID-ANIE2940>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LACH E.B., BROAD S., ROZENGURT E. Mitogenic signaling by transfected neuromedin B receptors in Rat-1 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1427–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUSHITA M., SHICHIRI M., IMAI T., IWASHINA M., TANAKA H., TAKASU N., HIRATA Y. Co-expression of urotensin II and its receptor (GPR14) in human cardiovascular and renal tissues. J. Hypertens. 2001;19:2185–2190. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHSAKO S., ISHIDA I., ICHIKAWA T., DEGUCHI T. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNAs encoding precursors of urotensin II-alpha and -gamma. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:2730–2735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-09-02730.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORBUCH M., TAYLOR J.E., COY D.H., MROZINSKI J.E, JR, MANTEY S.A., BATTEY J.F., MOREAU J.P., JENSEN R.T. Discovery of a novel class of neuromedin B receptor antagonists, substituted somatostatin analogues. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:841–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAYSANT J., RUPIN A., SIMONET S., FABIANI J.N., VERBEUREN T.J. Comparison of the contractile responses of human coronary bypass grafts and monkey arteries to human urotensin-II. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001;15:227–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2001.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON D., SHIVELY J.E., CLARK B.R., GESCHWIND Ii., BARKLEY M., NISHIOKA R.S., BERN H.A. Urotensin II: a somatostatin-like peptide in the caudal neurosecretory system of fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980;77:5021–5024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSSOWSKI W.J., CHENG B.L., TAYLOR J.E., DATTA R., COY D.H. Human urotensin II-induced aorta ring contractions are mediated by protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases and Rho-kinase: inhibition by somatostatin receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;438:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., MOLENAAR P., O'BRIEN D.M. Cardiostimulant effects of urotensin-II in human heart in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., PAKALA R., KATAGIRI T., BENEDICT C.R. Synergistic effect of urotensin II with mildly oxidized LDL on DNA synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2001;104:16–18. doi: 10.1161/hc2601.092848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOU Y., NAGAI R., YAMAZAKI T. Urotensin II induces hypertrophic responses in cultured cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]