Abstract

(6-((R)-2-{2-[4-(4-Chloro-phenoxy)-piperidin-1-yl]-ethyl}-pyrrolidine-1-sulphonyl)-1H-indole hydrochloride) (SB-656104-A), a novel 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT7) receptor antagonist, potently inhibited [3H]-SB-269970 binding to the human cloned 5-HT7(a) (pKi 8.7±0.1) and 5-HT7(b) (pKi 8.5±0.2) receptor variants and the rat native receptor (pKi 8.8±0.2). The compound displayed at least 30-fold selectivity for the human 5-HT7(a) receptor versus other human cloned 5-HT receptors apart from the 5-HT1D receptor (∼10-fold selective).

SB-656104-A antagonised competitively the 5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT)-induced accumulation of cyclic AMP in h5-HT7(a)/HEK293 cells with a pA2 of 8.5.

Following a constant rate iv infusion to steady state in rats, SB-656104 had a blood clearance (CLb) of 58±6 ml min−1 kg−1 and was CNS penetrant with a steady-state brain : blood ratio of 0.9 : 1. Following i.p. administration to rats (10 mg kg−1), the compound displayed a t1/2 of 1.4 h with mean brain and blood concentrations (at 1 h after dosing) of 0.80 and 1.0 μM, respectively.

SB-656104-A produced a significant reversal of the 5-CT-induced hypothermic effect in guinea pigs, a pharmacodynamic model of 5-HT7 receptor interaction in vivo (ED50 2 mg kg−1).

SB-656104-A, administered to rats at the beginning of the sleep period (CT 0), significantly increased the latency to onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep at 30 mg kg−1 i.p. (+93%) and reduced the total amount of REM sleep at 10 and 30 mg kg−1 i.p. with no significant effect on the latency to, or amount of, non-REM sleep. SB-269970-A produced qualitatively similar effects in the same study.

In summary, SB-656104-A is a novel 5-HT7 receptor antagonist which has been utilised in the present study to provide further evidence for a role for 5-HT7 receptors in the modulation of REM sleep.

Keywords: 5-HT7 receptor, SB-656104-A, SB-269970-A, guinea pig, rat, body temperature, pharmacokinetics, REM sleep

Introduction

The 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT7) receptor has been cloned from a number of species including human, rat and guinea pig (Bard et al., 1993; Lovenberg et al., 1993; Tsou et al., 1994) and has been shown to be positively coupled to adenylyl cyclase (AC) in both recombinant expression systems (e.g. Bard et al., 1993) and in brain tissue (Thomas et al., 1999). Alternative splicing of the 5-HT7 receptor gene in rat and human gives rise to a number of isoforms, namely, 5-HT7(a), (b), (c) in rat and 5-HT7(a), (b), (d) in human and in both species the 5-HT7(a) variant is the predominant isoform (Heidmann et al., 1998). The 5-HT7 receptor displays a unique pharmacological profile that is similar across both species and splice variants, being characterised by a high affinity of 5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT) and ((R)-3-(2-(2-(4-methyl-piperidin-1-yl)ethyl)-pyrrolidine-1-sulphonyl)phenol) (SB-269970-A), (Lovell et al., 2000), moderately high affinity of ritanserin and 8-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin (8-OH-DPAT) and low affinity of pindolol (Bard et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 2000).

mRNA and receptor localisation studies have confirmed that the 5-HT7 receptor is expressed in a number of higher brain regions in rodent and primate species including cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus and hypothalamus (To et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 2002), so potentially implicating the receptor in the control of higher brain function and the aetiology of psychiatric disorders. Consistent with this localisation pattern, the 5-HT7 receptor has recently been reported to modulate neuronal function in a number of brain regions, including rat hippocampus (Bacon & Beck, 2000; Gill et al., 2002) thalamus (Chapin & Andrade, 2001) and dorsal raphe nucleus (Roberts et al., 2001). Such studies have been aided by the use of the 5-HT7 receptor-selective antagonist, SB-269970-A, to confirm 5-HT7 receptor-mediated functional responses. Within the hypothalamus, 5-HT7 receptor mRNA and protein have been reported to be present in a number of nuclei including the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (Neumaier et al., 2001), which functions as the pacemaker for circadian rhythms in mammals (Rusak & Zucker, 1979). Consistent with the evidence for 5-HT7 receptor localisation in the SCN, pharmacological studies, utilising nonselective agonists and antagonists, have provided evidence for a role for 5-HT7 receptors in SCN function and the control of circadian rhythms (Lovenberg et al., 1993; Ehlen et al., 2001). These findings suggested that 5-HT7 receptors localised in the SCN and other brain regions implicated in circadian rhythm/sleep control might play a role in modulating sleep and, in turn, has provided the rationale to investigate the effect of the 5-HT7 receptor-selective antagonists on sleep architecture.

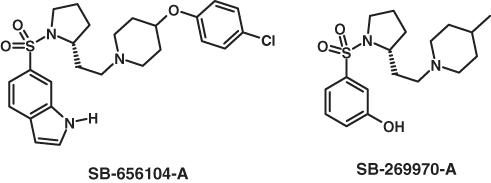

We have previously reported initial studies showing that SB-269970-A reduces the amount of random eye movement (REM) (paradoxical) sleep in rats (Hagan et al., 2000), so providing supportive evidence that 5-HT7 receptors play a role in the control of sleep architecture. However, SB-269970 is not an ideal tool compound for in vivo studies of 5-HT7 receptor function because of its very short half-life, for example, <0.5 h following intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration (Hagan et al., 2000). Therefore, a focussed structure–activity relation (SAR) study around SB-269970-A was initiated in order to try to identify better tool compounds for in vivo studies. Replacement of the phenolic group in SB-269970-A with an indole moiety, and replacement of the piperidinyl 4-methyl group with a heterocyclic ring system proved to be the key changes leading to the identification of 6-((R)-2-{2-[4-(4-chloro-phenoxy)-piperidin-l-yl]-ethyl}-pyrrolidine-1-sulphonyl)-1H-indole hydrochloride (SB-656104-A) (Figure 1), displaying a (∼4-fold) longer half-life in vivo compared to SB-269970-A (Forbes et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Structure of SB-269970-A and SB-656104-A (-A suffix refers to hydrochloride salt).

In the present study, we describe the pharmacological characterisation of SB-656104-A as a novel 5-HT7 receptor antagonist and its profile of action on REM sleep in rats, in comparison with SB-269970-A. Some of the studies described have been reported previously in preliminary form (Forbes et al., 2002).

Methods

All experimental work was conducted in compliance with the Home Office Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and with the Italian Ministry of Health and was reviewed and approved by the Glaxo-SmithKline Procedures Panel.

Radioligand-binding studies

Compound affinity for the human cloned 5-HT7(a) receptor was determined by displacement of [3H]-5-CT and [3H]-SB-269970 binding to cell membranes prepared from HEK293 cells stably expressing the h5-HT7(a) receptor according to the method described by Thomas et al. (1998), (2000), respectively. Binding to the human 5-HT7(b) splice variant was determined using [3H]-SB-269970 binding to membranes prepared from HEK293 cells transiently expressing the cloned receptor according to the method described by Thomas et al. (2000). The full-length 5-HT7(b) receptor gene was previously obtained by polymerase chain reaction from a human brain cDNA library, subcloned into a mammalian expression vector, pCDNA3 (Invitrogen Paisley, U.K.), and transiently expressed utilising the Lipofectamine 2000 method (Invitrogen). Affinity for rat native 5-HT7 receptors was determined by inhibition of [3H]-SB-269970 binding to membranes prepared from rat cerebral cortex according to the method described by Thomas et al. (2000). Binding to other 5-HT and non-5-HT receptor subtypes was determined according to the methods described by Hirst et al. (2000).

cAMP production in h5-HT7(a)/HEK293 cells

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels in cells were determined by radioimmunoassay using a Flashplate kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Cambridge, U.K., SMP004). Briefly, HEK293 cells stably expressing the human cloned 5-HT7(a) receptor (h5-HT7(a)/HEK293) were washed with PBS (Ca2+-free) and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at 21°C. The supernantant was discarded and two resuspension and centrifugation steps were carried out using the manufacturer's ‘stimulation buffer' (in the absence of IBMX). Finally, the cells were resuspended to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells ml−1 in stimulation buffer (containing IBMX). Cells (approximately 105 cells well−1) were incubated (15 min at 37°C) with a range of 5-CT concentrations (0.1 nM–100 μM) and in the presence or absence of SB-656104-A (30 nM–1 μM). Incubation was stopped by addition of the manufacturer's detection buffer containing [125I]-cAMP (0.16 mCi ml−1) to each well. Plates were counted between 4 and 24 h later using a Packard Topcount liquid scintillation counter.

[35S]-GTPγS binding to human 5-HT1D/CHO membranes

[35S]-GTPγS binding to washed membranes from CHO cells stably expressing the human cloned 5-HT1D receptor was measured using the method of Thomas et al. (1995). Briefly, membranes (20–30 μg protein) were preincubated (30°C for 30 min) in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence of 3 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 10 μM GDP, 0.2 mM ascorbate and in the presence or absence of test drugs. Incubations (30 min, 30°C) were started by addition of [35S]-GTPγS (0.1–3 nM) followed by vigorous mixing and stopped by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters followed by five 1 ml washes with ice-cold buffer containing 20 mM HEPES and 3 mM MgCl2. All determinations within an experiment were performed in duplicate. Radioactivity on the filters was determined using liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Data analysis

For receptor binding assays, the concentration of drug inhibiting specific [3H]-radioligand binding by 50% (IC50) was determined and pKi values (−log of the inhibition constant) were calculated from the IC50 values as described by Cheng & Prusoff (1973). Drug concentration–response curves from cAMP accumulation assays were fitted to a four-parameter logistic equation (Grafit, Erithacus Software, Horley, U.K.). Agonist potency was expressed as the pEC50 (−log EC50). Data for antagonism by SB-656104-A of 5-CT-stimulated cAMP production were analysed by Schild analysis (Arunlakshana & Schild, 1959) and an estimate of the pA2 obtained. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of at least three separate experiments each performed using triplicate (adenylyl cyclase activity) or duplicate (receptor binding) determinations. [35S]-GTPγS binding drug concentration–response curves were analysed by a four-parameter logistic equation using GRAFIT (Erithacus Software), and drug potency expressed as the pEC50 (−log EC50) or pIC50 for stimulation of inhibition of binding respectively. Inhibitory effects on basal binding were calculated after subtraction of nonspecific binding (representing approximately 3% of basal binding) defined in the presence of 10 μM unlabelled GTPγS. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of at least three separate experiments each performed in duplicate.

Pharmacokinetic studies with SB-656104

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, ca. 250 g body weight; n=3) were surgically equipped with a cannula in the jugular vein and femoral vein (Griffiths et al., 1996) and allowed 3 days to recover postoperatively. The disposition kinetics and oral bioavailability of SB-656104 were investigated following intravenous (i.v.) infusion of SB-656104, via the femoral vein, as a constant rate infusion over 1 h to achieve a target dose of 1 mg kg−1. SB-656104 was dissolved in 0.9% (w v−1) saline, containing 10% (w v−1) Encapsin™ HPB and 2% (v v−1) DMSO at final concentrations of 0.2 mg ml−1. The dose was administered at a rate of 5 ml kg−1 h−1. At 2 days after i.v. administration, the same three rats received an oral (p.o.) suspension administration of SB-656104 at a target dose of 3 mg kg−1. The compound was suspended in 1% (w v−1) aq methylcellulose at a target concentration of 0.6 mg ml−1, and administered at a target dose volume of 5 ml kg−1. Serial blood samples were taken via the jugular vein cannula over 10 h following i.v. infusion and 12 h following p.o. administration. Periodically preserved rat blood (containing 13% (v v−1) citrate–phosphate–dextrose solution with adenine) at 37°C was replaced, thereby ensuring that at no time during the course of the experiment did the blood volume removed exceed 15% of the circulating blood volume of the rat. After 3 days, the CNS penetration of SB-656104 was investigated following i.v. infusion to steady state in the same three rats. SB-656104 (formulated as above for i.v. infusion) was infused at a target dose rate of 0.6 mg kg−1 h−1 over 12 h. Blood samples were taken via the jugular vein during the latter part of the infusion to confirm steady-state blood concentrations and at 12 h the animals were killed by exsanguination and the brains removed. Blood samples (50 μl) were diluted with an equal volume of water and brain samples were homogenised with 1 vol. of water. All samples were stored at ca. –80°C prior to analysis.

The pharmacokinetics of SB-656104-A were determined from a composite profile following single i.p. administration (10 mg kg−1) to male rats (Sprague–Dawley, body weight ca. 250 g, n=2 animals per timepoint). SB-656104-A was dissolved in 0.9% (w v−1) saline, containing 10% (w v−1) Captisol at a final concentration of 5 mg ml−1. At various times following i.p. dosing, animals were anaesthetised with isoflurane and blood removed by cardiac puncture into heparinised tubes. Brains were also excised. Blood samples were diluted with an equal volume of water. All samples were stored at ca. −80°C prior to analysis.

Blood and brain homogenate samples were analysed for SB-656104 using a method based on protein precipitation and LC/MS/MS analysis. To samples of blood (50 μl diluted to 100 μl with water) and brain homogenate (50 μl), acetonitrile (250 μl) containing an appropriate internal standard was added. Samples were mixed thoroughly (mechanical shaking for 20 min), and then centrifuged (2465 × g for 20 min at room temperature). An aliquot (20 μl) of the resulting supernatant was assayed for SB-656104 concentrations using LC/MS/MS employing positive ‘Turbo-ionspray' ionisation (Sciex API III plus) and a YMC KL-C1 column (C18, 50 × 4 mm ID; Hichrom). The mobile phase was 72% (v v−1) acetonitrile/28% (v v−1) ammonium acetate (10 mM) at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. The lower limit of quantification was 0.01 μM (5 ng ml−1) and the assay was linear up to 10.24 μM (5000 ng ml−1). A value of 15 μl of blood per gram of brain tissue was used to correct the brain concentrations of test compound for any compound present in the residual blood following exsanguination (Brown et al., 1986). Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained from the blood concentration–time curves using WinNonlin Professional v.2.1 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, U.S.A.). Oral bioavailability was calculated from the ratio of the area under the blood concentration–time curve after p.o. and i.v. doses normalising for dose.

5-CT-induce hypothermia in guinea pigs

The method was as described by Hagan et al. (2000). Briefly, SB-656104-A (1, 3, 10, 30 mg kg−1) was injected i.p. 60 min before 5-CT (0.3 mg kg−1 i.p.). For each animal body, temperature was measured at 55, 85 and 115 min following 5-CT administration and used to calculate the mean maximal change in body temperature for that animal. Data are mean±s.e. values for groups of five to eight animals.

Sleep studies

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, Italy) were housed singly on a 12 h light : dark cycle (1400 : 0200 h light) 1 week prior to surgery. Access to food and water was allowed ad libitum. In order to avoid any external effect on the physiological sleep architecture of the animals, a telemetric transmission of electroencephalogram (EEG) and electrooculogram (EOG) biopotential signals was set up. A miniature multichannel telemetric transmitter (TL10M3-F50-EET, Data Sciences Int.) was implanted intra peritoneum and a receiver positioned directly under the home cages digitalising the radio-transmitted signals. Eight rats (275–300 g) were anaesthetised with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg kg−1 i.p.) and two couples of recording electrodes were transported subcutaneously towards the head. In order to record the cortical EEG, two electrodes were permanently fixed, with dental cement, to the skull directly in contact with the dura mater through two drilled holes on the fronto-parietal region. Two electrodes were fixed to the orbital muscles, for recording eye movements (EOG). Following surgery, animals were maintained in their home cage in a temperature-controlled environment (21±1°C) with access to food and water ad libitum. Implanted animals demonstrated a normal behavioural repertoire immediately after recovery from surgery and sleep patterns were assessed after 3 weeks.

The environment conditions described above were maintained during sleep studies. During the test periods, radio transmission of signals was activated by a magnet smoothly slid along the animal's abdomen. Drug studies were carried out according to a randomised paired crossover design, each animal receiving control and drug treatments. Compound effects on REM and non-REM sleep parameters were assessed over the first 5 h of the physiological sleep period (light period, starting at CT 0). EEG and EOG signals were recorded continuously using a UA10 (DSI) connected with a storing PC (Acqknowledge® software) through an A/D convertor (MP100WSW, Biopac Systems, Inc.).

The EEG trace, divided into 10 s epochs, was digitally transformed (FFT transformation) to provide the power spectra of the δ, θ, α and β bands in order to distinguish three different activity patterns in the rat (awake, non-REM sleep and REM sleep). The assigned markers of the automated scoring (using Sleep Analyzer® software, Ing. F Fioravanti) were transferred on the EEG digital signal and subsequently confirmed by the operator by visual parallel examination of the EEG and EOG traces.

The time spent in each sleep stage was calculated together with the number and duration of bouts. Latency to the first non-REM and REM sleep episodes was also quantified. Statistical analysis of the compound effect compared to the vehicle control was assessed using ANOVA followed by Dunnet's test.

Drugs

SB-269970-A hydrochloride and SB-656104-A were synthesised at SmithKline Beecham (Harlow, U.K.). For pharmacokinetic studies in the rat following i.v. and oral administration, the free base form of SB-656104 was used. For all other studies, the HCl salt was used (referred to as SB-656104-A). 5-hydroxytryptamine HCl (5-HT), 5-CT and methiothepin mesylate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, U.K). Captisol (Beta-cyclodextrin sulfobutyl ether, 7 sodium salt) was obtained from Cydex Inc. (Kansas, U.S.A.). For in vivo studies, drugs were dissolved in appropriate solvents (shown in parentheses); 5-CT (0.9% saline); SB-269970-A (distilled water); SB-656104 (10% Captisol/saline). A 1 ml kg−1 dose volume was used for all systemic treatments.

Results

Receptor binding studies

Recombinant and native 5-HT7 receptors can be radiolabelled using both the agonist radioligand, [3H]-5-CT (e.g. To et al., 1995) or the selective antagonist radioligand, [3H]-SB-269970 (Thomas et al., 2000). Both radioligands have been shown to label the same population of binding sites in either recombinant or native tissues with no evidence for multiple agonist affinity states.

SB-656104-A was a potent inhibitor of [3H]-5-CT binding to human 5-HT7(a)/HEK293 membranes (pKi 8.7±0.1) (Table 1) and inhibited [3H]-SB-269970 binding to human 5-HT7(a)/HEK293 membranes with a similar potency (pKi 8.7±0.1). The compound also displayed high affinity for the human 5-HT7(b) receptor splice variant as determined by the inhibition of [3H]-SB-269970 binding to HEK293 membranes transiently expressing the receptor (pKi 8.5±0.2) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Human recombinant receptor affinity profile for SB-656104-A

| Receptor | pKi |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 6.25±0.06 |

| 5-HT1B | 6.20±0.05 |

| 5-HT1D | 7.60±0.02 |

| 5-HT1E | <5.3 |

| 5-HT1F | <5.7 |

| 5-HT2A | 7.20±0.02 |

| 5-HT2B | 7.04±0.08 |

| 5-HT2C | 6.57±0.08 |

| 5-HT4 | 5.72±0.10 |

| 5-HT5A | 6.74±0.01 |

| 5-HT6 | 6.07±0.06 |

| 5-HT7 | 8.70±0.10 |

| α1B | 6.67±0.01 |

| D2 | 7.01±0.06 |

| D3 | 6.49±0.07 |

Data are the mean±s.e.m. from at least three separate experiments each performed in duplicate. Methods used were as described by Hirst et al. (2000).

SB-656104-A also displayed high affinity for the rat native 5-HT7 receptor as defined by the inhibition of [3H]-SB-269970 binding to rat cerebal cortex membranes (pKi 8.8±0.2) (data not shown). The Hill slope for SB-656104-A was not significantly different from 1, consistent with the displacement of binding from a single population of binding sites in this tissue. Table 1 shows the receptor affinity profile for SB-656104-A at the human cloned 5-HT7(a) receptor and at other human cloned 5-HT and non-5-HT receptor sites. The compound displayed at least 30-fold selectivity for the human 5-HT7(a) receptor versus other 5-HT receptor subtypes apart from the 5-HT1D receptor (∼10-fold selective).

cAMP accumulation in human 5-HT7(a)/HEK293 cells

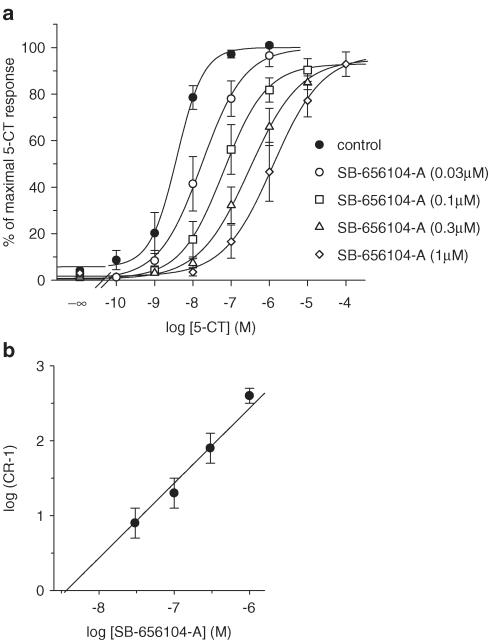

5-CT stimulated cAMP production in h5-HT7(a)/HEK293 cells from a basal level of 13±5.8 to 455±40 pmol 105 cells−1 and with a pEC50 of 8.44±0.14 (Figure 2a). SB-656104-A (0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM) produced a concentration-related rightward shift of the 5-CT concentration–response curve with no significant alteration in the maximal response to 5-CT. Schild analysis of the antagonism by SB-656104-A revealed a slope factor not significantly different from 1 (P=0.34, F-test) consistent with a competitive antagonist profile and a pA2 (corresponding to the pKB for a competitive antagonist) of 8.43±0.18 (Figure 2b). The pA2 value determined for SB-656104-A was comparable to the pKi value determined from radioligand binding studies (Table 1).

Figure 2.

(a) Stimulation of cAMP production in HEK293 cells stably expressing the human 5-HT7(a) receptor by 5-CT alone and in the presence of SB-656104-A (0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM). Data points represent the mean±s.e.m. of at least three separate experiments each performed using duplicate determinations. (b) Schild analysis of the same data.

[35S]-GTPγS binding to human 5-HT1D/CHO membranes

SB-656104-A displayed a moderately high affinity for the human 5-HT1D receptor (pKi 7.6, Table 1) and therefore the compound was evaluated for its functional effect on [35S]-GTPγS binding to human 5-HT1D/CHO membranes (Thomas et al., 1995). SB-656104-A produced a concentration-related inhibition of basal [35S]-GTPγS binding with a pEC50 of 7.38±0.08, comparable to the pKi value (7.60±0.02) obtained from radioligand binding studies (data not shown). SB-656104-A appeared to display an inverse agonist profile producing a maximal inhibition of 66.5±4.4% as compared to methiothepin, which in the same system inhibited basal [35S]-GTPγS binding by 69.7±6.4% (Thomas et al., 1995).

Pharmacokinetic studies

The disposition pharmacokinetics of SB-656104 were determined in the rat (n=3) following i.v. infusion (1 mg kg−1) over 1 h. The compound was well distributed with a steady-state volume of distribution (Vss; 6.7±1.3 l kg−1) in excess of total body water, indicating extensive distribution into tissues. Blood clearance was moderate (CLb; 57±4 ml min−1 kg−1) resulting in a terminal half-life (t1/2) of approximately 2 h. Oral bioavailability (3 mg kg−1) from a simple aqueous suspension was 16% (Table 2). The CNS penetration of SB-656104 was determined at steady state in the rat (n=3) following a constant rate i.v. infusion of SB-656104 (0.6 mg kg−1 h−1) over 12 h. Analysis of blood samples obtained during the latter part of the infusion confirmed steady-state conditions with mean brain and blood concentrations of 0.31 and 0.34 μM, respectively. SB-656104 was therefore CNS penetrant with a steady-state brain : blood ratio of ca. 0.9 : 1. The steady-state determination of CLb (58±6 ml min−1 kg−1) was in excellent agreement with that obtained following the 1 mg kg−1 dose administered over 1 h (57±4 ml min−1 kg−1), thereby confirming SB-656104 as a moderate clearance compound in the rat.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters in the rat following intravenous and oral administration of SB-656104

| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| Intravenous | |

| Dose (mg kg−1) | 1 |

| Terminal half-life (t1/2; h) | 2.0±0.2 |

| Volume of distribution at steady state (vss; l kg−1) | 6.7±1.3 |

| Blood clearance (CLb; ml min kg−1) | 57±4 |

| Oral | |

| Dose (mg kg−1) | 3 |

| Cmax (μM) | 0.042±0.012 |

| Tmax (h)a | 3.0 (2.6–3.0) |

| Terminal half-life (t1/2; h) | 5.1±1.1 |

| Bioavailability (Fpo; %) | 16±7 |

For Tmax, the median and range are quoted; units of measurement are given in brackets in column one; SB-656104 free base was used for the i.v./oral, DMPK studies; data represent mean±s.d. (n=3).

Following i.p. administration to rats at a dose of 10 mg kg−1, the compound displayed a t1/2 of 1.4 h, longer than that reported previously for SB-269970-A (Hagan et al., 2000). At 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h following i.p. administration, mean blood concentrations for SB-656104-A were 1.0, 0.94, 0.49, 0.50 and 0.11 μM, respectively, and mean brain concentrations were 0.65, 0.75, 0.71, 0.31 and 0.19 μM, respectively. The brain : blood ratio of SB-656104 derived from AUC values over 6 h was 1.1 : 1.

5-CT-induce hypothermia in guinea pigs

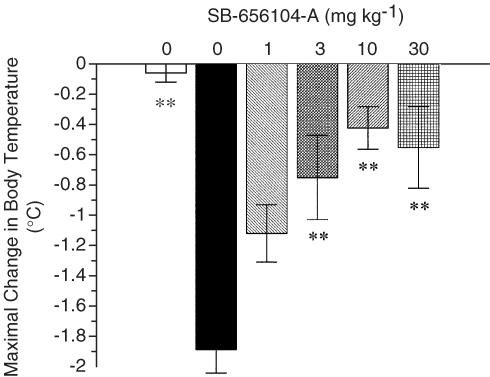

SB-656104-A was evaluated for its effect on 5-CT-induced hypothermia in guinea pigs, a 5-HT7 receptor pharmacodynamic model (Hagan et al., 2000). Although the pharmacokinetic studies had confirmed that SB-656104 (free base) is orally bioavailable in the rat, initial studies to investigate the effect of the compound following oral administration in the 5-CT hypothermia assay gave inconsistent data. For this reason, for this and subsequent in vivo studies, SB-656104-A was evaluated following i.p. administration using 10% captisol saline, a formulation that did not itself produce a significant change in body temperature (Figure 3). 5-CT (0.3 mg kg−1 i.p.) produced a significant hypothermic effect in the guinea pig (1.9±0.16°C). SB-656104-A (1, 3, 10 and 30 mg kg−1) injected i.p. 60 min before 5-CT, produced a significant reversal of the 5-CT-induced hypothermic effect at 3, 10 and 30 mg kg−1 and with an ED50 of 2 mg kg−1. The potency of SB-656104-A was comparable to that reported previously for SB-269970-A in this assay (ED50 3 mg kg−1, Hagan et al., 2000).

Figure 3.

Effect of SB-656104-A on 5-CT-induced hypothermia in guinea pigs. Vehicle (10% captisol/saline) or SB-656104-A (1, 3, 10, 30 mg kg−1) were injected i.p. 60 min before 5-CT (0.3 mg kg−1 i.p.). Body temperature was measured 55, 85 and 115 min after 5-CT administration. Open and solid bars indicate the effect of vehicle control and 5-CT alone, respectively. Data are mean±s.e.m. values for groups of five to eight animals. **P<0.01 compared to the 5-CT alone group following significant one-way ANOVA (F (d.f. 5, 41)=8.01, P=0.00004).

Sleep studies

A preliminary evaluation was carried out to investigate the effect of the vehicle used on physiological sleep patterns (CT 0) by comparing the effect of i.p. administration of 10% captisol/saline or saline (1 ml kg−1). An increased activity of the animals was observed in the first 2 h following 10% captisol/saline compared to saline, probably due to a weak irritant effect induced by captisol. However, there was no significant difference in the latency to the onset of non-REM or REM sleep. In contrast, a significant decrease in the time spent in non-REM sleep was observed in the first 2 h after administration of 10% captisol/saline together with a significant reduction in REM sleep measured in the second hour following dosing (data not shown). There was no significant difference in the amount of non-REM or REM sleep between the 10% captisol/saline and saline-treated animals in the third hour after injection. Thus, the effect of 10% captisol/saline was limited to a transient decrease in both non-REM and REM sleep during the first 2 h of the sleep period. It was therefore concluded that although the physiological baseline was modified by the captisol administration, the impact of this effect on the evaluation of the pharmacological activity of the compound was minimal.

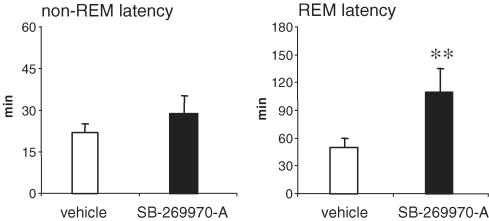

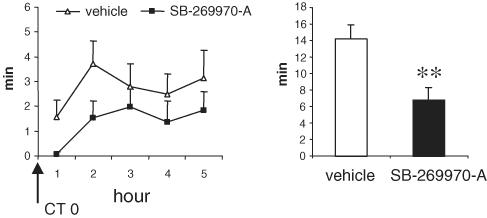

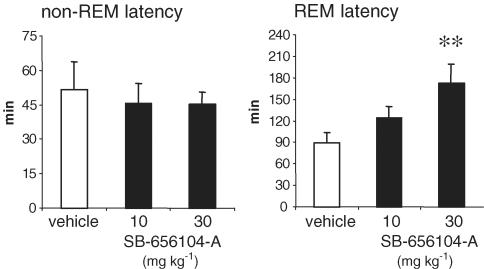

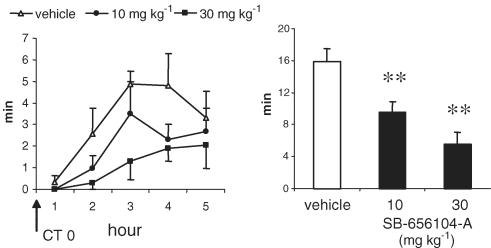

SB-269970-A (30 mg kg−1 i.p.), administered at the beginning of the light period (CT 0, 14 : 00 h), significantly increased (+108%) the latency to the first REM sleep period (Figure 4). SB-269970-A also significantly reduced the time spent in REM sleep in the subsequent 5 h period (Figure 5). In contrast, this dose of SB-269970-A did not significantly alter either the latency to or amount of non-REM sleep. When administered at 10 mg kg−1 i.p., SB-269970-A did not significantly alter either REM or non-REM sleep parameters (data not shown). A qualitatively similar profile of effect was seen for SB-656104-A which, when administered at the beginning of the light period (CT 0), significantly increased the latency to onset of REM sleep at 30 mg kg−1 i.p. (+93% compared to vehicle (Figure 6) and also significantly reduced the total amount of REM sleep at both 10 and 30 m kg−1 i.p. (Figure 7). As seen for SB-269970-A, there was no significant effect on non-REM sleep latency (Figure 6) or the distribution of non-REM sleep over the 5 h recording period (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of SB-269970-A on non-REM and REM sleep latency (mean±s.e.m.) during the physiological sleep phase. Vehicle or SB-269970-A (30 mg kg−1) were administered orally at the beginning of the sleep phase (CT 0, 14.00 h) to eight animals, following a Latin square experimental design. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnet's test. **P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated control animals.

Figure 5.

Effect of SB-269970-A on REM sleep distribution, during the first 5 h of the physiological sleep phase. Data (mean±s.e.m.) are expressed as minutes spent in REM sleep phase for each of the hours or as the total amount (min) in the recorded window. Vehicle or SB-269970-A (30 mg kg−1) were administered orally at the beginning of the sleep phase (CT 0, 14.00 h) to eight animals, following a Latin square experimental design. Statistical significance on the total amount of REM sleep was assessed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnet's test. **P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated control animals.

Figure 6.

Effect of SB-656104-A on non-REM and REM sleep latency (mean±s.e.m.) during the physiological sleep phase. Vehicle or SB-656104-A (10 and 30 mg kg−1) were administered orally at the beginning of the sleep phase (CT 0, 14.00 h) to eight animals, following a Latin square experimental design. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnet's test. **P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated control animals.

Figure 7.

Effect of SB-656104-A on REM sleep distribution, during the first 5 h of the physiological sleep phase. Data (mean±s.e.m.) are expressed as minutes spent in REM sleep phase for each of the hours or as the total amount (min) in the recorded window. Vehicle or SB-656104-A (10 and 30 mg kg−1) were administered orally at the beginning of the sleep phase (CT 0, 14.00 h) to eight animals, following a Latin square experimental design. Statistical significance on the total amount of REM sleep was assessed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnet's test. **P<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated control animals.

Discussion

Following the cloning of the 5-HT7 receptor from a number of species (e.g. Bard et al., 1993; Lovenberg et al., 1993), pharmacological studies using nonselective agonists and antagonists provided evidence that 5-HT7 receptors may play a functional role in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus (Lovenberg et al., 1993; Ying & Rusak, 1997). However, such brain 5-HT7 receptor functional studies have until recently been hindered by a lack of 5-HT7 receptor-selective ligands. We have previously reported SB-269970-A to be a potent and selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist (Hagan et al., 2000; Lovell et al., 2000) and this tool compound has proved useful for in vitro studies to provide further evidence for a role for 5-HT7 receptors in brain function (Bacon & Beck, 2000; Chapin & Andrade, 2001; Gill et al., 2002). We have also reported that SB-269970-A inhibits REM sleep in rats suggesting that 5-HT7 receptors may play a role in control of sleep architecture (Hagan et al., 2000). However, SB-269970-A is not ideal as a tool for such in vivo studies due to its short half-life (<0.5 h). Therefore, SAR studies were initiated, based around SB-269970-A, leading to the identification of SB-656104-A (Forbes et al., 2002). In the present study, we have characterised SB-656104-A as a novel 5-HT7 receptor antagonist in vitro and in vivo and investigated its profile of action on REM sleep in rats, in comparison with SB-269970-A.

In the present study, SB-656104-A was shown to be a potent competitive antagonist at the human cloned 5-HT7(a) receptor and displayed at least 30-fold selectivity versus other human cloned 5-HT receptor subtypes, apart from the 5-HT1D receptor at which the compound displayed an inverse agonist profile. To date, inverse agonism has not been reported at native 5-HT receptors and the relevance or otherwise of this profile of action to the effects of SB-656104-A in vivo is unclear.

In contrast to SB-269970-A which showed a high clearance (Hagan et al., 2000), SB-656104 was a moderate clearance compound in rat (CLb 57 ml min−1 kg−1) and following i.p. administration to rats displayed a t1/2 of 1.4 h, approximately three-fold longer than that reported previously for SB-269970-A (Hagan et al., 2000). Furthermore, brain concentrations of SB-656104-A measured following i.p. administration suggested that significant 5-HT7 receptor occupancy could be achieved.

SB-656104-A was also evaluated for its effect on 5-CT-induced hypothermia in guinea pigs, a 5-HT7 receptor pharmacodynamic model (Hagan et al., 2000). Initial studies to investigate the effect of the compound in the 5-CT hypothermia assay following oral administration gave inconsistent data. Although the reasons for this were not systematically investigated, a contributory factor appeared to be variability in the degree of gut absorption of SB-656104-A since blood : brain levels of the compound were found to vary markedly between animals following p.o. dosing (data not shown). In contrast, SB-656104-A, when administered i.p. produced a dose-related reversal of the 5-CT-induced hypothermic effect and with a potency comparable to that reported previously for SB-269970-A (Hagan et al., 2000). This study therefore indicated that significant 5-HT7 receptor occupancy of SB-656104-A could be achieved in the guinea pig following i.p. dosing.

Evidence in support of a role for the 5-HT7 receptor in SCN function (Lovenberg et al., 1993; Ying and Rusak, 1997; Ehlen et al., 2001) as well as evidence for a relation between disturbances in circadian rhythms and sleep (e.g. Dijk & Czeisler, 1995) provided the rationale to investigate the effect of the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, SB-269970-A, on sleep architecture. The compound has been reported to inhibit REM sleep in the rat without significant effects on other sleep parameters (Hagan et al., 2000). In the present study, we utilised both SB-656104-A and SB-269970-A to further investigate the putative role of 5-HT7 receptors in the control of REM sleep.

When administered at 30 mg kg−1 i.p. at the beginning of the light period (CT 0), both compounds produced a significant increase in the latency to onset of REM sleep and a significant decrease in the time spent in REM sleep measured over the first 5 h of the normal sleep period. In contrast, neither compound significantly altered non-REM sleep parameters. In addition, SB-656104-A (but not SB-269970-A) also significantly reduced the total amount of REM sleep at a dose of 10 mg kg−1 i.p. The more potent effect of SB-656104-A on time spent in REM sleep, compared to SB-269970-A, might be at least partly explained by the longer half-life of the compound following i.p. administration to rats, as determined in pharmacokinetic studies. Overall these data are consistent with the earlier findings of Hagan et al. (2000) reporting an inhibition of REM sleep by SB-269970-A.

The brain concentrations of SB-656104-A measured in a parallel study over a similar time course to that used for the sleep studies predicted a significant degree of 5-HT7 receptor occupancy, although in addition, some occupancy of 5-HT1D and 5-HT2A receptors might also be predicted based on the moderately high affinity of the compound for these receptors (Table 1). However, it is unlikely that an action at these subtypes contributes to the effects on REM sleep since SB-656104-A displayed a qualitatively similar profile of action on REM sleep compared to SB-269970-A, which shows low affinity for both 5-HT1D and 5-HT2A receptors (Lovell et al., 2000). It therefore appears likely that the modulation of REM sleep produced by SB-656104-A and SB-269970-A is explained by their 5-HT7 receptor antagonist properties.

The mechanism by which 5-HT7 receptor antagonism leads to modulation of REM sleep has not been established. It is unlikely that the effects on REM sleep would be due to 5-HT7 receptor-mediated effects on body temperature. Although SB-269970-A has been reported to reduce body temperature in the rat (Kogan et al., 2002), the effect seen was modest. Furthermore, although sleep structure and body temperature both show a circadian rhythm, there is no clear evidence that the circadian modulation of REM sleep is directly related to alterations in body temperature (Dijk, 1999). A more likely explanation for the profile of effect of SB-269970-A and SB-656104-A on REM sleep is via antagonism of 5-HT7 receptors localised in brain regions implicated in the control of sleep and/or circadian rhythms.

Pharmacological studies have provided evidence that 5-HT7 receptors play a role in the modulation of SCN function which acts as the circadian pacemaker in mammals (Lovenberg et al., 1993; Ying and Rusak, 1997; Ehlen et al., 2001). Furthermore, modulation of circadian phase has been shown to alter a number of sleep parameters, including REM sleep (Dijk & Czeisler, 1995). It is therefore possible that 5-HT7 receptors localised in brain regions involved in circadian rhythm/sleep control, such as the SCN, could indirectly modulate REM sleep via alterations in circadian phase.

Key neuronal pathways underlying the generation of REM sleep are thought to involve the activation of pontine GABA-ergic neurones leading to the inhibition of noradrenergic neurones and serotonergic neurones in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus, respectively. This, in turn, leads to the disinhibition of cholinergic ‘REM-on' neurones in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and related nuclei in the mesopontine tegmentum. These nuclei send descending projections to spinal regions to control muscle tone and ascending projections to GABAergic neurones in higher brain regions, such as the thalamus and hippocampal CA3 regions, implicated in the generation of EEG rhythms (Pace-Schott & Hobson, 2002).

Interestingly, 5-HT7 receptors have been reported to play a role in mediating the 5-HT induced modulation of neuronal function not only in the SCN, but also in a number of other brain areas, namely, the dorsal raphe nucleus (Roberts et al., 2001), thalamus (Chapin & Andrade, 2001) and hippocampal CA3 region (Bacon & Beck, 2001; Gill et al., 2002), which have all been implicated in sleep and/or circadian rhythm control (Pace-Schott & Hobson, 2002). Furthermore, there is evidence that 5-HT7 receptor activation leads to inhibition of GABA-ergic neuronal activity in a number of these regions (Kawahara et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 2002).

Although a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist-induced disinhibition of GABAergic neuronal activity might be predicted to give rise to an increase in REM sleep because of increased inhibitory GABAergic tone on 5-HT neurones in the dorsal raphe and consequent disinhibition of mesopontine cholinergic ‘REM-on' neurones, it is important to note that GABA has also been reported to directly inhibit mesopontine cholinergic neurones (Xi et al., 1999). Thus, disinhibition of GABAergic neurones could lead to either facilitation or inhibition of REM sleep and therefore represents a potential mechanism to explain the profile of effect of SB-269970-A and SB-656104-A on REM sleep in rats.

The profile of action of SB-656104-A and SB-269970-A on REM sleep suggests that 5-HT7 receptor antagonists could have clinical utility, potentially, for mood disorders and in particular unipolar depression. Depression is often characterised by a diurnal variation in mood and disrupted circadian timing and sleep patterns. A number of sleep abnormalities have been observed in depressed patients including reduced total sleep time, reduced sleep efficiency and a decreased REM sleep latency combined with an increase in the amount of REM sleep (Gillin et al., 1981; Brunello et al., 2000). In contrast, most antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants increase REM latency and decrease REM density in depressed patients (Staner et al., 1999). One caveat is that not all antidepressant agents produce the same qualitative changes in REM sleep (Brunello et al., 2000). However, a recent study has reported a positive correlation between the latency to the onset of REM sleep, following a single dose of the mixed noradrenaline/dopamine uptake inhibitor, buproprion, and the clinical response to treament with the compound (Ott et al., 2002). Furthermore, the degree of REM latency change in response to buproprion challenge was shown to correlate with the change in depression ratings following long-term treatment.

Data suggest that one mechanism by which antidepressants show clinical efficacy might be by modulating disrupted sleep patterns through a normalisation of the monoamine equilibrium. Interestingly, SB-656104-A and SB-269970-A both produced a qualitatively similar effect on REM sleep parameters compared to that seen for antidepressants from a number of different classes, raising the possibility that 5-HT7 receptor antagonists might show efficacy in depression through normalising disrupted sleep.

Moreover, a number of other findings appear consistent with a potential role for 5-HT7 receptors in the mechanisms underlying depression. Chronic antidepressant administration has been reported to downregulate 5-HT7-like binding sites in rat hypothalamus (Sleight et al., 1995; Mullins et al., 1999; Atkinson et al., 2001), suggesting that 5-HT7 receptors in the hypothalamus may play a role in the therapeutic effects of antidepressants. In addition, 5-HT7 receptor (−,−) knockout mice have been reported to show an antidepressant-like profile in the Porsolt forced swim model (Guscott et al., 2000).

In summary, SB-656104-A has been characterised as a potent 5-HT7 receptor antagonist in vitro which displays an improved pharmacokinetic profile in vivo compared to SB-269970-A. Both SB-656104-A and SB-269970-A have been utilised in the present study to provide further evidence for a role for 5-HT7 receptors in the modulation of REM sleep and a potential role of the receptor in the mechanisms underlying mood disorders such as unipolar depression. SB-656104-A therefore represents a useful tool for studies, both in vitro and in vivo, to further investigate the role of the 5-HT7 receptor in brain function.

Abbreviations

- CT

circadian time

- 5-CT

5-carboxamidotryptamine

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- EOG

electrooculogram

- 8-OH-DPAT

8-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin

- REM sleep

rapid eye movement sleep

- SAR

structure–activity relation

- SB-269970-A

(R)-3-(2-(2-(4-methyl-piperidin-1-yl)ethyl)-pyrrolidine-1-sulphonyl)phenol)

- SB-656104-A

6-((R)-2-{2-[4-(4-chloro-phenoxy)-piperidin-1-yl]-ethyl}-pyrrolidine-1-sulphonyl)-1H-indole hydrochloride

- SSRI

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

References

- ARUNLAKSHANA O., SCHILD H.O. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATKINSON P.J., DUXON M.S., PRICE G.W., HASTIE P.G., THOMAS D.R. Paroxetine down-regulates 5-HT7 receptors in rat hypothalamus but not hippocampus following chronic administration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:40. [Google Scholar]

- BACON W.L., BECK S.G. 5-Hydroxytryptamine7 receptor activation decreases slow afterhyperpolarization amplitude in CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;294:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARD J.A., ZGOMBICK J., ADHAM N., VAYSSE P., BRANCHEK T.A., WEINSHANK R.L. Cloning of a novel human serotonin receptor (5-HT7) positively linked to adenylate cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:23422–23426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN E.A., GRIFFITHS R., HARVEY C.A., OWEN D.A. Pharmacological studies with SK&F 93944 (temelastine), a novel histamine H1-receptor antagonist with negligible ability to penetrate the central nervous system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:569–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUNELLO N., ARMITAGE R., FEINBERG I., HOLSBOER-TRACHSLER E., LEGER D., LINKOWSKI P., MENDELSON W.B., RACAGNI G., SALETU B., SHARPLEY A.L., TUREK F., VAN CAUTER E., MENDLEWICZ J. Depression and sleep disorders: clinical relevance, economic burden and pharmacological treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42:107–119. doi: 10.1159/000026680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPIN E.M., ANDRADE R. A 5-HT7 receptor-mediated depolarization in the anterodorsal thalamus. I. Pharmacological characterization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (IC50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIJK D.J. Circadian variation of EEG power spectra in NREM and REM sleep in humans: dissociation from body temperature. J. Sleep Res. 1999;8:189–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIJK D.J., CZEISLER C.A. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:3526–3538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03526.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EHLEN J.C., GROSSMAN G.H., GLASS J.D. In vivo resetting of the hamster circadian clock by 5-HT7 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5351–5357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05351.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORBES I.T., DOUGLAS S., GRIBBLE A.D., IFE R.J., LIGHTFOOT A.P., GARNER A.E., RILEY G.J., JEFFREY P., STEVENS A.J., STEAN T.O., THOMAS D.R. SB-656104-A: a novel 5-HT7 receptor antagonist with improved in vivo properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:3341–3344. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILL C.H., SOFFIN E.M., HAGAN J.J., DAVIES C.H. 5-HT7 receptors modulate synchronized network activity in rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:82–92. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLIN J.C., DUNCAN W.B., MURPHY D.L., POST R.M., WEHR T.A., GOODWIN F.K., WYATT R.Y., BUNNEY W.E. Age-related changes in sleep in depressed and normal subjects. Psych. Res. 1981;4:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(81)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS R.G., LEWIS A., JEFFREY P.Models of drug absorption in situ and in conscious animals Models for Assessing Drug Absorption and Metabolism 1996New York: Plenum Press; 74–78.eds. Borchardt, R.T., Smith, P.L. and Wilson, G. pp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUSCOTT M.R., FONE K., HADINGHAM K., BROMIDGE F., STANTON J.A., BEER M.S., WHITING P., BRISTOW L.J.The effect of 5-HT7 receptor knockout in the mouse forced swim test Serotonin: From the Molecule to the Clinic 200081Society for Neuroscience Satellite Meeting, New Orleans, November 2000, p

- HAGAN J.J., PRICE G.W., JEFFREY P., DEEKS N.J., STEAN T., PIPER D., SMITH M.I., UPTON N., MEDHURST A.D., MIDDLEMISS D.N., RILEY G., LOVELL P.J., BROMIDGE S., THOMAS D.R. Characterisation of SB-269970-A, a selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:539–548. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIDMANN D.E.A., SZOT P., KOHEN R., HAMBLIN M.W. Function and distribution of three rat 5-hydroxytryptamine7 (5-HT7) receptor isoforms produced by alternative splicing. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1621–1632. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRST W.D., MINTON J.A.L., BROMIDGE S.M., MOSS S.F., LATTER A.J., RILEY G., ROUTLEDGE C., MIDDLEMISS D.N., PRICE G.W. Characterisation of [125I]-SB-258585 binding to human recombinant and native 5-HT6 receptors in rat, pig and human brain tissues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1597–1605. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAHARA F., SAITO H., KATSUKI H. Inhibition of 5-HT7 receptor-activated current in cultured rat suprachiasmatic neurones. J. Physiol. 1994;478:67–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOGAN H.A., MARSDEN C.A., FONE K.C.F. DR4004, a putative 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, also has functional activity at the dopamine D2 receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;449:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVELL P.J., BROMIDGE S.M., DABBS S., DUCKWORTH D.M., FORBES I.T., JENNINGS A.J., KING F.D., MIDDLEMISS D.N., RAHMAN S.K., SAUNDERS D.V., COLLIN L.L., HAGAN J.J., RILEY G.J., THOMAS D.R. A novel, potent and selective 5-HT7 antagonist: (R)-3-(2-(2-(4-methylpiperidin-1-yl)ethyl)-pyrrolidine-1-sulfonyl)-phenol (SB-269970) J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:342–345. doi: 10.1021/jm991151j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVENBERG T.W., BARON B., DE LECEA L., MILLER J.D., PROSSER R.A., REA M.A., FOYE P.E., RACKE M., SLONE A.L., SIEGEL B.W., DANIELSON P.E., SUTCLIFFE J.G., ERLANDER M.G. A novel adenylyl cyclaseactivating serotonin receptor (5-HT7) implicated in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. Neuron. 1993;11:449–458. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90149-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLINS U.L., GIANUTSOS G., EISON A.S. Effects of antidepressants on 5-HT7 receptor regulation in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:352–367. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUMAIER J.F., SEXTON T.J., YRACHETA Y., DIAZ A.M., BROWNFIELD M. Localization of 5-HT7 receptors in rat brain by immunocytochemistry, in situ hybridization, and agonist stimulated cFos expression. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2001;21:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTT G.E., RAO U., NUCCIO I., LIN K.M., POLAND R.E. Effect of buproprion-SR on REM sleep: relationship to antidepressant response. Psychopharmacology. 2002;165:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PACE-SCHOTT E.F., HOBSON J.A. The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat. Rev. NeuroSci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS C., LANGMEAD C.J., SOFFIN E.M., DAVIES C.H., LACROIX L., HEIDBREDER C.A.The effect of SB-269970-A, a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist on 5-HT release and cell firing Monitoring Molecules in Neuroscience 2001Univ. College Dublin, Ireland; 348–350.eds. O'Connor, W.T., Lowry, J.P., O'Connor, J.J. & O'Neill, R.D. pp [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS C., THOMAS D.R., KEW J.N.C. GABAergic modulation of 5-HT7 receptor-mediated effects on 5-HT efflux. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSAK B., ZUCKER I. Neural regulation of circadian rhythms. Physiol. Rev. 1979;59:449–526. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLEIGHT A.J., CAROLO C., PETIT N., ZWINGELSTEIN C., BOURSON A. Identification of 5-hydroxytryptamine7 receptor binding sites in rat hypothalamus: sensitivity to chronic antidepressant treatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANER L., LUTHRINGER R., MACHER J.P. Effects of antidepressant drugs on sleep EEG in patients with major depression – mechanisms and therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 1999;11:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS D.R., ATKINSON P.J., HASTIE P.G., ROBERTS J.C., MIDDLEMISS D.N., PRICE G.W. [3H]-SB-269970 radiolabels 5-HT7 receptors in rodent, pig and primate brain tissues. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:74–81. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS D.R., ATKINSON P.J., HO M., BROMIDGE S.M., LOVELL P.J., HAGAN J.J., MIDDLEMISS D.N., PRICE G.W. [3H]-SB-269970-A selective antagonist radioligand for 5-HT7 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:409–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS D.R., FARUQ S.A., BALCAREK J.M., BROWN A.M. Pharmacological characterisation of [35S]-GTPγS binding to Chinese hamster ovary cell membranes stably expressing cloned human 5-HT1D receptor subtypes. J. Recept. Signal Transduction Res. 1995;15:199–211. doi: 10.3109/10799899509045217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS D.R., GITTINS S.A., COLLIN L.L., MIDDLEMISS D.N., RILEY G., HAGAN J., GLOGER I., ELLIS C.E., FORBES I.T., BROWN A.M. Functional characterisation of the human cloned 5-HT7 receptor (long form); antagonist profile of SB-258719. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1300–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS D.R., MIDDLEMISS D.N., TAYLOR S.G., NELSON P., BROWN A.M. 5-CT stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in guinea pig hippocampus: evidence for involvement of 5-HT7 and 5-HT1A receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:158–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TO Z.P., BONHAUS D.W., EGLEN R.M., JAKEMAN L.B. Characterization and distribution of putative 5-HT7 receptors in guinea-pig brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSOU A.P., KOSAKA A., BACH C., ZUPPAN P., YEE C., TOM L., ALVAREZ R., RAMSEY S., BONHAUS D.W., STEFANICH E., JAKEMAN L., EGLEN R.M., CHAN H.W. Cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 receptor positively coupled to adenylyl cyclase. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XI M.C., MORALES F.R., CHASE M.H. Evidence that wakefulness and REM sleep are controlled by a GABAergic pontine mechanism. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2015–2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YING S.W., RUSAK B. 5-HT7 receptors mediate serotonergic effects on light-sensitive suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Brain Res. 1997;755:246–254. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]