Abstract

Retinal microvessel responses to kinin B1 and B2 receptor agonists and antagonists were investigated in streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats and age-matched controls. In addition, quantitative in vitro autoradiography was performed on retinas from control and STZ-diabetic rats with radioligands specific for B2 ([125I]HPP-Hoe 140), and B1 receptors ([125I]HPP-[des-Arg10]-Hoe 140).

In control rats, the B2 receptor agonist bradykinin (BK, 0.1–50 nM) vasodilated retinal vessels in a concentration and time-dependent manner. This effect was completely blocked by the B2 receptor antagonist Hoe140 (1 μM). In contrast, the B1 receptor agonist des-Arg9-BK (0.1–50 nM) was without effect.

Des-Arg9-BK was able to produce a concentration-dependent vasodilatation as early as 4 days after STZ injection, and the effect of 1 nM des-Arg9-BK was inhibited by the B1 receptor antagonist des-Arg10-Hoe140 (1 μM). Low-level B1 receptor binding sites were detected in control rats, but densities were 256% higher in retinas from 4- to 21-day STZ-diabetic rats.

In control rats, the vasodilatation in response to 1 nM BK involved neither calcium influx nor nitric oxide (NO) as GdCl3 and L-NAME were without effect. However, the vasodilatation did involve intracellular calcium mobilization as well as products of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathway as 2,5-di-t-butylhydroquinone (BHQ), cADP ribose and L-745 337 inhibited this response. The vasodilatation response was blocked by trans-2-phenyl cyclopropylamine (TPC) demonstrating that prostacyclins mediate this response.

In STZ-diabetic rats, the vasodilatation in response to des-Arg9-BK involved both calcium influx and intracellular calcium mobilization from stores both IP3 sensitive and non-IP3 sensitive. Indeed, the effect was blocked by GdCl3, BHQ and cADP ribose. Furthermore, NO production and products of the COX-2 pathway including prostacyclin are involved as the response was inhibited by L-NAME, L-745 377 and TPC.

Vasodilatation in response to either 1 nM BK or 1 nM des-Arg9-BK were blocked by NF023 demonstrating that a Go/Gi G-protein transduces both these effects.

This is the first report on the retinal circulation which provides evidence for vasodilator B2 receptors and the upregulation of B1 receptors very early following induction of diabetes with STZ rats. These results suggest that kinin receptors may be potential targets for therapeutics to treat retinopathies.

Keywords: Bradykinin, B1 receptors, B2 receptors, retina, circulation, streptozotocin, diabetes

Introduction

Components of the kallikrein–kinin system have been shown to be expressed in the retina (Kuznetsova et al., 1991; Ma et al., 1996; Takeda et al., 1999), and kinin receptor agonists induce calcium mobilization in retinal capillary endothelial cells (Hasséssian & Pogan, 2003), which suggests that kinins may play a role in the retinal circulation. Kinins are a family of structurally related 9–11 amino-acid peptides including bradykinin (BK), kallidin (KD; Lys-BK), T-kinin (Ile-Ser-BK; exclusively in the rat) and des-Arg9-kinins which are active metabolites (des-Arg9-BK, Lys-des-Arg9-BK). Kinins exert a variety of vascular effects through two transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors designated B1 and B2 (Regoli & Barabé, 1980; Regoli et al., 1998). While B2 receptors are constitutively expressed, B1 receptors are generally not, or are underexpressed in physiological conditions. Induction or upregulation of B1 receptors occurs following tissue injury, inflammation, diabetes, and following treatment with bacterial endotoxins, certain cytokines or growth factors (Marceau, 1995; Marceau et al., 1997; Marceau & Bachvarov, 1998). Kinins interact with their receptors on the cell surface to mediate a variety of biological effects, such as vasodilatation, regulation of local blood flow, stimulation of cell proliferation, production of pain and inflammatory responses (Marceau & Bachvarov, 1998; Couture et al., 2001). Studies in non-ocular tissues suggest that the kallikreinkinin system may be implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, and intervenes in the maintenance of diabetic lesions (Zuccollo et al., 1996; Cloutier & Couture, 2000; Christopher et al., 2001; Couture et al., 2001). However, its role in the retinal circulation and the pharmacological profile of kinin receptors remains to be elucidated. In the current study, we used an in situ system to investigate B1 and B2 retinal vascular mechanisms in STZ-diabetic rats and age-matched controls. Furthermore, densities of B1 and B2 receptor binding sites in the retina of these animals were determined by in vitro autoradiography.

Methods

STZ-diabetic rat model

Male Wistar rats weighing 225–250 g were purchased from Charles River, St-Constant, Québec, Canada and housed four per wire-bottom cage in rooms under controlled temperature (23–25°C), humidity (50%) and lighting (12 h light–dark cycle) with food and tap water available ad libitum. They were used 3–5 days after their arrival and injected under low light with freshly prepared STZ (65 mg kg−1 i.p.) (Sigma, St-Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Age-matched controls were injected with the sodium citrate buffer (0.05 M, pH 4.5) vehicle. Glucose concentrations were measured, with a commercial blood glucose monitoring Kit (Accusoft, Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec), in blood samples obtained from the tail vein, before STZ injection, and after STZ injection just prior to experimentation in nonfasting animals. Only STZ-treated rats whose blood glucose concentration was higher than 20 mM were considered as diabetic. All animal procedures were in strict compliance with the guiding principles for animal experimentation as established by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO), the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Animal Care Committee of our institutions. Rats were killed at 1, 4, 7 and 21 days post-STZ or vehicle injection, by asphyxia under respiratory Halothane.

In situ experimental procedure

Rat eyes were enucleated by a careful incision of the optic nerves and immediately placed in ice-cold Krebs buffer (pH 7.4) consisting of the following composition (mM): 120 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 27 NaHCO3, 1.0 KH2PO4 and 10 glucose. The retinas were prepared as previously described (Lahaie et al., 1998). Briefly, an incision was made along the entire circumference of the globe at the junction between the sclera and the cornea. The cornea as well as the vitreous humour were then removed with minimal handling of the retina, and the remaining eye cup containing the retina, was fixed with pins to a wax well where it was bathed in 270 μl Krebs buffer. The outer vessel diameter was recorded with a video camera mounted on a dissecting microscope (MZ12, Leica), and responses were quantified by a digital image analyser (Scion Image software, Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.). Vessels with an outer diameter of ≈10 μm were chosen for investigation.

The thromboxane A2 analog 9,11-dideoxy-11α, 9α epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2α (U-46619; 1 μM) was used to provide vascular tone. U-46619 is a reliable vasoconstrictor of retinal vessels, and provides consistent tone for more than 1 h allowing our vasodilation studies to be freely conducted. This thromboxane analogue is regularly used to provide tone in retinal vasodilation studies (Lahaie et al., 1998; Hasséssian, 2000). Vascular diameters were recorded 10 min after administration of BK (B2 agonist) or des-Arg9-BK (B1 agonist). Other retinal preparations were pretreated for 15 min with the antagonist to be tested before the application of BK (1 nM) or des-Arg9-BK (1 nM). Only one treatment and agonist was given to each retinal preparation.

Tissue preparation for autoradiography

Once the retinas were prepared as described above, they were put down on a prefrozen cryomatrix (Shandon, PA, U.S.A.) and submerged in 2-methyl butane cooled at −45 to −55°C with liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C until use. Retinal tissues from four rats per group were mounted together in a gelatine bloc and serially cut into 20 μm thick coronal sections with a cryostat fixed at a temperature between −11 and −13°C. Thus, each section of the cryostat was from four different retinas. A total of four sections per slide (total of 16 retinal slices) were then alternatively thaw-mounted on 0.2% gelatine/0.033% chromium potassium sulphate-coated slides. Two slides were taken for the total binding and one slide (adjacent sections) for the nonspecific binding for each eye. A total of six slides for both eyes were obtained for each group studied and kept at −80°C until use.

In vitro receptor autoradiography

Sections were incubated at room temperature for 90 min in 25 mM PIPES (piperazine-N,N′-bis[2-ethanesulphonic-acid] buffer (pH 7.4; 4°C) containing: 1 mM 1,10-phenanthroline, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.014% bacitracin, 0.1 mM captopril, 0.2% BSA (protease free) and 7.5 mM magnesium chloride in the presence of 150 pM [125I]HPP-desArg10-Hoe 140 (for B1 receptor) or 200 pM [125I]HPP-Hoe 140 (for B2 receptor). Concentrations of radioligands were chosen on the basis of earlier studies in rat tissues, and yielded maximal specific binding (Bmax) on saturation curves (Cloutier et al., 2002). The nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM of unlabelled ligands (HPP-desArg10-Hoe 140 for B1 receptor and HPP-Hoe 140 for B2 receptor). To ascertain the specificity of the labelled B2 radioligand, the same concentration of unlabelled B1 ligand was added to the solution. Likewise, the same concentration of the unlabelled B2 ligand was added to the labelled B1 ligand solution. At the end of the incubation period, slides were transferred sequentially through four rinses of 4 min each in 25 mM PIPES (pH 7.4; 4°C) and dipped for 15 s in distilled water (4°C) to remove excess salts and air-dried. [3H]-Hyperfilm was juxtaposed onto the slides in the presence of [125I]-microscales and exposed at room temperature for 3 days (B1 ligand) or 2 days (B2 ligand). The films were developed in D-19 (Kodak developer) and fixed in Kodak Ektaflo. Autoradiograms were quantified by densitometry using an image analysis system (MCID™, Imaging Research, Ontario, Canada). Standard curve from [125I]-microscales was used to convert density levels into femtomoles per milligram of tissue (fmol mg−1 tissue). Specific binding was determined by subtracting superimposed digitalized images of nonspecific labelling from total binding.

Iodination procedure

Iodination of HPP-desArg10-Hoe 140 and HPP-Hoe 140 was performed according to the chloramine T method (Hunter & Greenwood, 1962). Briefly, 5 μg of peptide were incubated in 0.05 M phosphate buffer for 30 s in the presence of 0.5 mCi (18.5 MBq) of Na125I and 220 nmol of chloramine T in a total volume of 85 μl. The monoiodinated peptide was then immediately purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography on a C4 Vydac column (0.4 × 250 mm2) (The Separations Group, Hesperia, CA, U.S.A.) with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile as mobile phases. The specific activity of the iodinated peptides corresponds to 2000 cpm fmol−1 or 1212 Ci mmol−1.

Chemicals

All reagents and NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS or NOS III) inhibitor, Moncada et al., 1991), indomethacin (cyclooxygenases-1 and 2 inhibitor), 5-methanesulphonamido-6-(2,4-difluorothio-phenyl)-1-indanone (L-745 337) (cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, Warner et al., 1999), trans-2-phenyl cyclopropylamine (TPC) (inhibitor of prostaglandin I2 synthase, Hardy et al., 1998), gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) (vascular endothelial cationic channel blocker, Adding et al., 1998) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St-Louis, MO, U.S.A.). BK and des-Arg9-BK are from Bachem Bioscience Inc. (King of Prussia, PA, U.S.A.), Hoe 140 (D-Arg[Hyp3,Thi5,D-Tic7,Oic8]-BK) (B2 receptor antagonist, Hock et al., 1991) and des-Arg9D-Arg[Hyp3,Thi5,D-Tic7,Oic8]-BK (des-Arg10-Hoe 140) (B1 receptor antagonist, Wirth et al., 1991), from Peninsula Laboratories Inc. (Belmont, CA, U.S.A.), cADP-ribose (inhibitor of Ca2+ mobilization from internal pools that are distinct from IP3-sensitive pools, Galione, 1993), NF023 (8,8′-[Carbonylbis(imino-3,1-phenylene)]bis-(1,3,5-naphthalenetrisulfonic acid), 6Na) (selective and direct G-protein antagonist for α-subunits of the Go/Gi group, Freissmuth et al., 1996), and 2,5-di-t-butylhydroquinone (BHQ) (inhibitor of sarcoplasmic reticulum and microsomal Ca2+-ATPase activity, Khodorova & Astashkin, 1994) from Calbiochem (LaJolla, CA, U.S.A.). HPP-desArg10-Hoe 140 (3-4 hydroxyphenyl-propionyl-desArg9-D-Arg[Hyp3, Thi5, D-Tic7, Oic8]-BK) and HPP-Hoe 140 (3-4 hydroxyphenyl-propionyl-D-Arg[Hyp3, Thi5, D-Tic7, Oic8]-BK) were respectively developed from the selective B1 receptor antagonist desArg10-Hoe 140 (Wirth et al., 1991) and the B2 receptor antagonist Hoe 140 or Icatibant (Hock et al., 1991) in the laboratory of Dr D. Regoli (Department of Pharmacology, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada). Autoradiographic [125I]-microscales (20 μm) and [3H]-Hyperfilm (single-coated, 24 × 30 cm2) were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Canada.

Data analysis

Data are expressed as means±s.e.m., where n represents the number of retinas, and one retina was used from each rat. The vasodilatory responses are expressed as a percentage of the surface area, constituted by a chosen length of vessel, when compared to the vessel diameter before application of U-46619. Results were analysed using Student's t-test for unpaired samples. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett test was used for multiple comparisons with one control group. Only P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Kinetic and concentration–response effect of BK on retinal vessel dilation

The maximal vasodilatation in response to 1 nM BK (P<0.01, n=5) was obtained within 10 min of administration, whereas 1 nM des-Arg9-BK was without effect (P>0.05, n=5) up to 30 min after application (Figure 1a). All subsequent measures of the response to BK and des-Arg9-BK were taken 10 min after administration. BK (0.1–50 nM) increased (P<0.01, n=7) the diameter of retinal vessels in a concentration-dependent manner with an ED50 of 250 pM and the maximal effect was produced by 10 nM BK (Figure 1b). In contrast, des-Arg9-BK (0.1–50 nM) was without effect on the retinal vessel diameter (P>0.05, n=5). Vasodilatation induced by 1 nM BK was completely blocked (P<0.001, n=7) by the B2 receptor antagonist (Hoe 140, 1 μM) (Figure 1c), whereas in a separate set of experiments, the B1 receptor antagonist (des-Arg10-Hoe 140, 1 μM) was without significant effect (P>0.05, n=5) on the BK-induced retinal vessel dilation (Figure 1c). Both antagonists had no direct effect on the vascular tone.

Figure 1.

BK induces rat retinal vessel dilation. (a) Kinetic of the effect of BK (1 nM) and des-Arg9-BK (1 nM) up to 30 min. (b) Concentration–response effect of BK or des-Arg9-BK. Retinal vessel diameter was recorded after a serial (10 min) increasing topical application of BK or des-Arg9-BK (0.1–50 nM). (c) B2 receptors mediate BK-induced retinal vessel dilation. Retinal vessel diameter was recorded after a topical application of Hoe 140 (1 μM) or des-Arg10-Hoe 140 (1 μM) followed 15 min later by the application of BK (1 nM). Responses are expressed as per cent change in the outer diameter of the vessel from baseline (n=5–7). Statistical comparison to time zero (a) or in the absence of agonist (b) or to U-46619 (1 μM) (c) is indicated by (*) or to BK (c) is indicated by (†), where **, P<0.01; *** and †††, P<0.001.

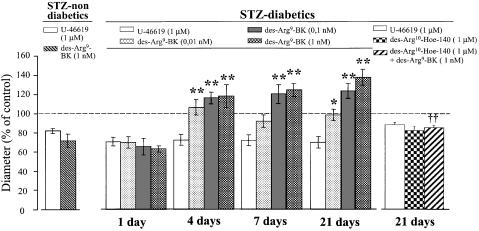

Induction of kinin B1 receptor expression in STZ-diabetic rat retinal vessels

Retinas from 1-, 4-, 7- and 21-day diabetic rats were given 0.01, 0.1 or 1 nM des-Arg9-BK. While 1-day diabetic rat retinal vessels did not dilate in response to any concentration of des-Arg9-BK which were tested (P>0.05, n=6), retinal vessels from 4-, 7- and 21-day diabetic rats dilated (P<0.01, n=6) in a concentration-related manner in response to des-Arg9-BK (Figure 2). However, retinas from STZ-treated nondiabetic rats were not responsive (P>0.05, n=3) to 1 nM des-Arg9-BK up to 21 days after STZ injection (data not shown). Furthermore, vasodilatation induced by 1 nM des-Arg9-BK was completely blocked (P<0.01, n=6) by des-Arg10-Hoe 140 (1 μM) in 21-day STZ-diabetic rats (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Induction of kinin B1 receptor expression in STZ-diabetic rat retinal vessels. Vessel diameter of retina from 1, 4, 7 and 21 days STZ-treated rats was recorded after a serial (10 min) topical application of des-Arg9-BK (0.01–1 nM). Moreover, retinal vessel diameter to des-Arg9-BK (1 nM) was recorded 15 min after the application of des-Arg10-Hoe 140 (1 μM). Responses are expressed as per cent change in the outer diameter of the vessel from baseline (n=3–6). Statistical comparison to U-46619 is indicated by (*) or to des-Arg9-BK is indicated by (1 nM) (†), where *, P<0.05; **, and ††, P<0.01.

Pharmacology of the retinal vessel dilation in control and STZ-diabetic rats

A preliminary set of experiments were conducted, aimed at verifying the subtype of G-protein involved in the kinin-mediated retinal vessel dilation. Retinal vessels from either control or STZ-diabetic rats failed to dilate in response to 1 nM BK or 1 nM des-Arg9-BK (P<0.01, n=3–4) when they were pretreated with NF-023 (100 μM) (Figure 3a and b). In control rats, L-NAME (100 μM) did not modify (P>0.05, n=5) the vasodilatation response to 1 nM BK (Figure 3a). However, indomethacin (1 μM) and L-745 337 (1 μM) blocked (P<0.01, n=6–8) the effect of 1 nM BK (Figure 3a). Furthermore, TPC (5 μM) also blocked (P<0.01, n=6) the effect of 1 nM BK (Figure 3a). In addition, pretreatment of retinas with GdCl3 (10 mM) did not affect (P>0.05, n=5) the vasodilatation response to 1 nM BK (Figure 3a). In contrast, pretreatment of retinas with BHQ (10 μM) or cADP ribose (10 μM) inhibited (P<0.05, n=5–6) the vasodilatation response to 1 nM BK (Figure 3a). Conversely, in STZ-diabetic rats, the vasodilatation response to des-Arg9-BK was blocked or significantly reduced (P<0.01, n=4) by all inhibitors which were used (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Pharmacology of the effects of BK and des-Arg9-BK on retinal vessel tone. Vessel diameter of retina from control (a) or STZ-diabetic rats at 21 days (b) was recorded after topical application of NF023 (100 μM), L-NAME (100 μM), indomethacin (1 μM), L-745 337 (1 μM), TPC (5 μM), GdCl3 (10 mM), BHQ (10 μM) or cADP ribose (10 μM) followed by the application of BK (1 nM) (a), or des-Arg9-BK (1 nM) (b). The responses are expressed as per cent change in the outer diameter of the vessel from baseline (n=4–8). Statistical comparison to U-46619 is indicated by (*) or to agonist alone is indicated by (†), where †, P<0.05; **, and ††, P<0.01.

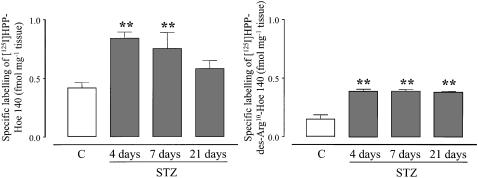

Autoradiography of kinin receptors in control and STZ-diabetic rat retina

Quantitative in vitro autoradiography was performed to analyse the amount of B1 and B2 receptor binding sites in retinas of 4-, 7- and 21-day STZ-diabetic rats and age-matched controls. Levels of specific B1 and B2 receptor binding sites were significantly higher (P<0.01, n=4) in STZ-diabetic rats (Figure 4). Values ranged from 0.42±0.04 to 0.90±0.05 fmol mg−1 tissue (B2 receptor) and from 0.15±0.03 to 0.39±0.02 fmol mg−1 tissue (B1 receptor) respectively in control and STZ-treated rats at 4 days (Figure 4). Hence, the level of B1 receptor binding sites in STZ-diabetic rats was increased by 256% to reach values obtained for B2 receptor binding sites in control rats. While levels of B1 receptor binding sites remained steady and high between 4 and 21 days after STZ injection, B2 receptor binding sites declined with the duration of diabetes. Whereas B2 receptor binding sites were 215% higher than controls after 4 days of diabetes, this increase was no longer significant 21 days after the induction of diabetes with STZ.

Figure 4.

Quantification of specific binding sites with [125I]-HPP-Hoe 140 (B2 receptors) and [125I]-HPP-[des-Arg10]-Hoe 140 (B1 receptors) in the retinal tissue of control (c) and STZ-diabetic rats at 4, 7 and 21 days. Values represent the means±s.e.m. of four rats in each group. Statistical comparison to control is indicated by **P<0.01.

Discussion

This is the first report showing the induction of B1 receptors on retinal vessels of STZ-diabetic rats. Earlier studies have demonstrated that various ocular tissues possess different components of the kallikrein–kinin system (Kuznetsova et al., 1991; Ma et al., 1996; Takeda et al., 1999), and that cultured bovine retinal capillary endothelial cells express only B2 receptors (Hasséssian & Pogan, 2003). Our present results in naive rats show that BK produces a B2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation of retinal vessels with an ED50 of 250 pM. This value is consistent with the Kd which has been reported for the B2 receptor in other tissues (Hall, 1997). Furthermore, our results show that control rat retinal vessels do not express functional B1 receptors, which is consistent with the studies in cultured bovine retinal capillary endothelial cells (Hasséssian & Pogan, 2003). By using an RT–PCR analyses and in situ hybridization, Ma et al. (1996) found that endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels express mRNA for both B1 and B2 receptors. However, there was no investigation of the translation of receptor protein or its insertion into the cell membrane. It is possible that even if the B1 receptor mRNA is transcribed, it will be partially translated or not at all translated because of its instability, or because of an uncoupling with intracellular transducers. The B1 receptor is only minimally expressed under normal physiological conditions as also shown by our present autoradiographic study on isolated retinas. However, functional B1 receptor number is rapidly induced under pathological conditions (Marceau, 1995; Marceau et al., 1997). A previous study illustrated that the expression of this gene is regulated not only by transcriptional activation, but also by post-transcriptional mRNA stabilization process (Zhou et al., 1998). The 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the mRNA is a primary site for the regulation of mRNA stability (Cleveland & Yen, 1989; Bohjanen et al., 1991). A recent study showed that the 3′-UTR of the B1 receptor is very short, containing only 14 bases with an alternative polyadenylation signal (AUUAAA) which overlaps with the stop codon. This region had been proven to be responsible for the relative instability of the B1 receptor transcripts (Zhou et al., 1999). These studies have also shown that the decrease in the B1 mRNA stability is accompanied by a strong decrease in the function of the receptor protein (Zhou et al., 1999), providing clear evidence for the post-transcriptional regulation of the B1 receptor and its expression. Conversely, in STZ-diabetic rats, des-Arg9-BK dilates retinal vessels via B1 receptors and these effects are greater in magnitude than those evoked by B2 receptors in control rats. The response to the B1 receptor agonist appear as early as between 1 and 4 days after the induction of diabetes and remained quite stable between 4 and 21 days which is consistent with the sustained upregulation of B1 receptor binding sites during that period. This observation is directly related to hyperglycemia and is not due to the direct effect of STZ on retinal vessels since STZ-injected rats which did not develop hyperglycemia, did not respond to des-Arg9-BK up to 21 days after injection of STZ. These results are consistent with the profile of B1 expression in other tissues (spinal cord, renal glomeruli, neutrophils of pleural cavity) where B1 induction has been shown to take place in STZ-treated diabetic rats (Cloutier & Couture, 2000; Couture et al., 2001; Mage et al., 2002).

B1 and B2 receptors are linked to a variety of intracellular transduction pathways (Couture & Lindsey, 2000). It is clear that both B1 and B2 receptors which mediate retinal vasodilatation are coupled to G-proteins of the Go/Gi family. Any further characterization of the G-proteins involved will require isolation and sequencing of the G-proteins. Once stimulated, B2 receptors evoke a rise of intracellular calcium derived from the mobilization of IP3-sensitive and IP3-insensitive pools. There does not appear to be the need for any calcium influx for B2 receptor-evoked vasodilatation of retinal vessels. This observation is not unique to these cells as stimulation of mesangial cells with BK preferentially released calcium from intracellular pools (Girolami et al., 1995). The rise of intracellular calcium is associated with the release of prostaglandins, mainly prostacyclin, which mediates the vasodilatation in response to B2 receptor stimulation in our study. Exposure of bovine cultured aortic endothelial cells to ionomycin was followed by a significant release of prostacyclin (Parsaee et al., 1993). Moreover, staurosporine inhibited BK-stimulated prostacyclin release (Parsaee et al., 1993). Prostacyclin is a key mediator of vessel dilation and the rate-limiting enzyme in its synthesis is cyclooxygenase. The present data with L-745 337 suggest the involvement of the inducible form (COX-2) of cyclooxygenase in the vasodilatation response to B2 agonist challenge. This is compatible with the vasodilatation effect of BK through endothelial cells (Regoli et al., 1998).

The response to kinins appears to be accentuated under diabetic conditions, due to several changes. An important development in diabetes is the induction of the B1 receptor. Although its G-protein coupling appears to be similar to that of the B2 receptor found in the control rat retinal circulation, there are marked changes downstream which appear to play a pronounced role in the vasodilatation response. In the STZ-diabetic rat, stimulation of kinin receptors leads to a rise of intracellular calcium which, unlike in the control rat, is due to a combination of influx and release of calcium from intracellular IP3-sensitive as well as non-IP3-sensitive pools. This combination, leading to a rise of intracellular calcium, produces the release of not only prostacyclin through COX-2, as was observed in the control rat, but also of nitric oxide (NO). Thus, the vasodilatation mediated by B1 receptors in STZ-diabetic rats is more complex than that mediated by B2 receptors in control rats. Indeed, prolonged exposure to pathologically high D-glucose concentrations results in an enhanced endothelium-derived relaxing factor (NO) formation caused by the amplification of agonist-stimulated calcium mobilization in endothelial cells (Graier et al., 1993). This mechanism may be of particular importance representing a possible basis of vasodilatation and reduced vascular resistance in diabetes. Autoradiographic data showing a transient upregulation of B2 receptor binding sites but a sustained upregulation of B1 receptor binding sites from 4 to 21 days post-STZ treatment may suggest that B1 receptors take over the effect of B2 receptors during the evolution of the disease.

Although vasodilation may be present very early in diabetic retinopathy, ischaemia is eventually a deleterious factor in the disease. Irrespective of the underlying causes for such ischaemia, vasodilators may be of potential therapeutic use. BK and desArg9BK metabolites are vasodilators which are degraded by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) (Couture et al., 2001), and ACE inhibition is known to have beneficial effects in the diabetic retina (Sjolie et al., 1997; Sjolie & Chaturvedi, 2002). Such observations warrant further investigation of kinins in relation to ocular vascular diseases. Future studies will clarify the full scope of the role kinins have in diabetic retinopathy. In conclusion, the present data show that control rat retinas contains only functional B2 receptors but not B1 receptors. Early in diabetes, the retinal circulation begins to express B1 as well as B2 receptors, both of which are upregulated and produce vasodilatation. These results are the first evidence for a possible implication of kinin receptors in retinal vasodilation which is one of the changes which take place in the diabetic retina, and raise the need to investigate further the potential involvement of kinins in the initiation or progression of the full scope of microvascular changes which take place in diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Quebec and The Canadian Diabetes Association for their support. H.M.H. is a Scholar of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

Abbreviations

- BK

bradykinin

- des-Arg9-BK

des-Arg9-bradykinin

- Cox

cyclooxygenases

- STZ

streptozotocin

References

- ADDING L.C., BANNENBERG G.L., GUSTAFSSON L.E. Gadolinium chloride inhibition of pulmonary nitric oxide production and effects on pulmonary circulation in the rabbit. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;83:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOHJANEN P.R., BETYNIAK B., JUNE C.H., THOMPSON C.B., LINDSTEN T. An inducible cytoplasmic factor (AU-B) binds selectively to AUUUA multimers in 3′untranslated region of lymphokine mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:3288–3295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTOPHER J., VELARDE V., ZHANG D., MAYFIELD D., MAYFIELD R.K., JAFFA A.A. Regulation of B(2)-kinin receptors by glucose in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H1537–H1546. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEVELAND D.W., YEN T.J. Multiple determinants of eucaryotic mRNA stability. New Biol. 1989;1:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLOUTIER F., COUTURE R. Pharmacological characterization of the cardiovascular responses elicited by kinin B1 and B2 receptor agonists in the spinal cord of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:375–385. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLOUTIER F., DE SOUSA BUCK H., ONGALI B., COUTURE R. Pharmacologic and autoradiographic evidence for an up-regulation of kinin B2 receptors in the spinal cord of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1641–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTURE R., HARRISSON M., VIANNA R.M., CLOUTIER F. Kinin receptors in pain and inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;429:161–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTURE R., LINDSEY C.J.Brain kallikrein–kinin system: from receptors to neuronal pathways and physiological functions Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy 2000Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V; 241–300.ed. Quirion, R., Björklund, A. & Hökfelt, T. Vol. 16, Part I, Peptide Receptors. pp [Google Scholar]

- FREISSMUTH M., BOEHM S., BEINDL W., NICKEL P., IJZERMAN A.P., HOHENEGGER M., NANOFF C. Suramin analogues as subtype-selective G protein inhibitors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:602–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALIONE A.V. Cyclic ADP-ribose: a new way to control calcium. Science. 1993;259:325–326. doi: 10.1126/science.8380506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIROLAMI J.P., OUARDANI M., BASCANDS J.L., PÉCHER C., BOMPART G., LEUNG-TACK J. Comparison of B1 and B2 receptor activation on intracellular calcium, cell proliferation, and extracellular collagen secretion in mesangial cells from normal and diabetic rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995;73:848–853. doi: 10.1139/y95-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAIER W.F., WASCHER T.C., LACKNER L., TOPLAK H., KREJS G.J., KUKOVETZ W.R. Exposure to elevated D-glucose concentrations modulates vascular endothelial cell vasodilatory response. Diabetes. 1993;42:1497–1505. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.10.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.M. Bradykinin receptors. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997;28:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDY P., ABRAN D., HOU X., LAHAIE I., PERI K.G., ASSELIN P., VARMA D.R., CHEMTOB S. A major role for prostacyclin in nitric oxide-induced ocular vasorelaxation in the piglet. Circ. Res. 1998;83:721–729. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H.M. Insights into the vasodilation of rat retinal vessels evoked by vascular endothelial growth factor121 (VEGF121) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000;476:101–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4221-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSÉSSIAN H.M., POGAN L.Retinal capillary endothelial cells express functional kinin B2 receptors 2003. Submitted

- HOCK F.J., WIRTH K., ALBUS U., LINZ W., GERHARDS H.J., WIEMER G., HENKE S.T., BREIPOHL G., KÖNIG W., KNOLLE J., SCHÖLKENS B.A. Hoe 140 a new potent and long acting bradykinin-antagonist: in vitro studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:769–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER W.M., GREENWOOD F.C. Preparation of iodine-131 labelled human growth hormone of high specific activity. Nature. 1962;194:495–496. doi: 10.1038/194495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHODOROVA A.B., ASTASHKIN E.I. A dual effect of arachidonic acid on Ca2+ transport systems in lymphocytes. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUZNETSOVA T.P., CHESNOKOVA N.B., PASKHINA T.S. Activity of tissue and plasma kallikrein and level of their precursors in eye tissue structures and media of healthy rabbits. Vopr. Med. Khim. 1991;37:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAHAIE I., HARDY P., HOU X., HASSÉSSIAN H., ASSELIN P., LACHAPELLE P., ALMAZAN G., VARMA D.R., MORROW J.D., ROBERTS L.J., CHEMTOB S.A. Novel mechanism for vasoconstrictor action of 8-isoprostaglandin F2 alpha on retinal vessels. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:R1406–R1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MA J.X., SONG Q., HATCHER H.C., CROUCH R.K., CHAO L., CHAO J. Expression and cellular localization of the kallikrein–kinin system in human ocular tissues. Exp. Eye Res. 1996;63:19–26. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGE M., PÉCHER C., NEAU E., CELLIER E., DOS REISS M.L., SCHANSTRA J.P., COUTURE R., BASCANDS J.-L., GIROLAMI J.-P. Induction of B1 receptors in streptozotocin diabetic rats: possible involvement in the control of hyperglycemia-induced glomerular Erk 1 and 2 phosphorylation. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2002;80:328–333. doi: 10.1139/y02-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F. Kinin B1 receptors: a review. Immunopharmacology. 1995;30:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00011-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., BACHVAROV D.R. Kinin receptors. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 1998;16:385–401. doi: 10.1007/BF02737658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., LARRIVEE J.-F., SAINT-JACQUES E., BACHVAROV D.R. The kinin B1 receptor: an inducible G protein coupled receptor. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCADA S., PALMER R.M., HIGGS E.A. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARSAEE H., MCEWAN J.R., MACDERMOT J. Bradykinin-induced release of PGI2 from aortic endothelial cell lines: responses mediated selectively by Ca2+ ions or a staurosporine-sensitive kinase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:411–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., BARABÉ J. Pharmacology of bradykinin and related kinins. Pharmacol. Rev. 1980;32:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., NSA ALLOGHO S., RIZZI A., GOBEIL F. Bradykinin receptors and their antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;348:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SJOLIE A.K., CHATURVEDI N. The retinal renin–angiotensin system: implications for therapy in diabetic retinopathy. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002;16 (3):S42–S46. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SJOLIE A.K., STEPHENSON J., ALDINGTON S., KOHNER E., JANKA H., STEVENS L., FULLER J. Retinopathy and vision loss in insulin-dependent diabetes in Europe. The EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:252–260. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEDA H., KIMURA Y., HIGASHIDA H., YOKOYAMA S. Localization of B2 bradykinin receptor mRNA in the retina and sclerocornea. Immunopharmacology. 1999;45:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARNER T.D., GIULIANO F., VOJNOVIC I., BUKASA A., MITCHELL J.A., VANE J.R. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIRTH K., BREIPOHL G., STECHL J., KNOLLE J., HENKE S., SCHÖLKENS B.A. Des-Arg9-D-Arg-[Hyp3, Thi5, D-Tic7, Oic8]-BK (des-Arg10-[Hoe 140]) is a potent bradykinin B1 receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;205:217–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90824-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU X., POLGAR P., TAYLOR L. Roles for interleukin-1 beta, phorbol ester and a post-transcriptional regulator in the control of bradykinin B1 receptor gene expression. Biochem. J. 1998;330:361–366. doi: 10.1042/bj3300361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU X., PRADO G.N., CHAI M., YANG X., TAYLOR L., POLGAR P. Posttranscriptional destabilization of the bradykinin B1 receptor messenger RNA: cloning and functional characterization of the 3′-untranslated region. Mol. Cell Biol. Res. Commun. 1999;1:29–35. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZUCCOLLO A., NAVARRO M., CATANZARO O. Effects of B1 and B2 kinin receptor antagonists in diabetic mice. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1996;74:586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]