Abstract

We examined whether β3- and/or atypical β-adrenoceptors relax the rat isolated mesenteric artery.

Mesenteric arteries precontracted with phenylephrine were relaxed by β-agonists with the following potencies (pD2): nonselective agonist isoprenaline (6.00)>nonconventional partial agonist cyanopindolol (5.45)>β2-agonist fenoterol (4.98)>nonconventional partial agonist CGP 12177 (4.19)>β3-agonist ZD 2079 (3.72). The β3-agonist CL 316243 1 mM relaxed the vessel only marginally.

The concentration–response curves (CRCs) for cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 were not affected by the nonselective β-antagonist propranolol 0.3 μM, the β2-antagonist ICI 118551 1 μM and by CL 316243 60 μM, but shifted to the right by bupranolol (pA2 5.3–5.7), CGP 20712 (5.4) and SR 59230A (6.5–6.7) (the latter three drugs block atypical and/or β3-adrenoceptors at high concentrations).

The CRC for isoprenaline was shifted to the right by propranolol (pA2 7.0) but, in the presence of propranolol 0.3 μM, not affected by SR 59230A 1 μM. The CRC for fenoterol was shifted to the right by propranolol (pA2 6.9) and ICI 118551 (6.8).

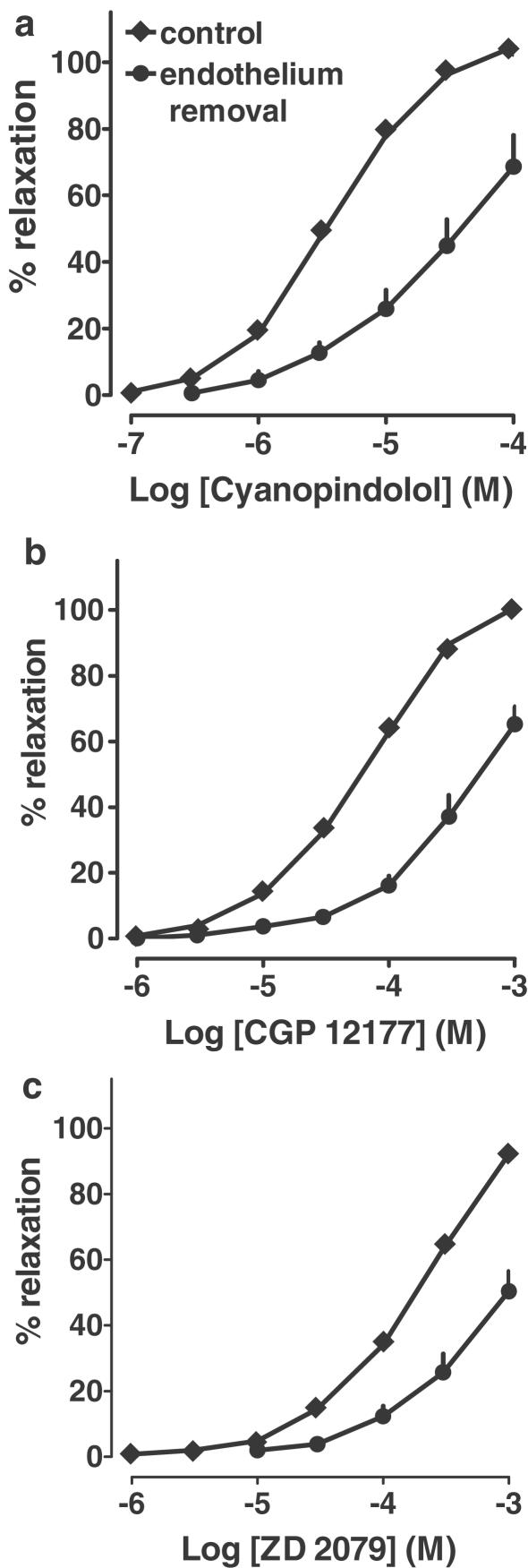

Removal of endothelium diminished the vasorelaxant effects of cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079.

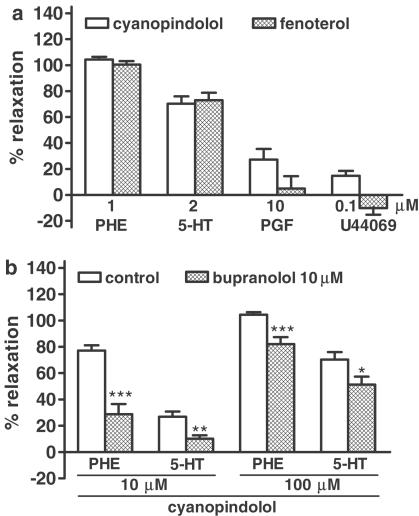

Fenoterol and cyanopindolol also relaxed (endothelium-intact) mesenteric arteries precontracted with serotonin. The relaxant effect of cyanopindolol was antagonized by bupranolol to about the same degree as in phenylephrine-contracted vessels.

In conclusion, β2- and atypical β-adrenoceptors (but not β3-adrenoceptors) relax the rat mesenteric artery. The atypical β-adrenoceptor, which is partially located endothelially, may differ from the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor.

Keywords: Atypical β-adrenoceptors, β3-adrenoceptors, cyanopindolol, CGP 12177, ZD 2079, CL 316243, CGP 20712, bupranolol, SR 59230A, rat mesenteric artery

Introduction

During the last decade, it has been shown that, in addition to β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, additional types of β-adrenoceptors mediate cardiovascular effects, including the β3-adrenoceptor and one or even two additional types of β-adrenoceptors (for review, see Kaumann & Molenaar, 1997; Brodde & Michel, 1999; Brahmadevara et al., 2003). The latter receptor(s) as opposed to the β3-adrenoceptor will be termed here ‘atypical β-adrenoceptor(s)'.

In the heart, the presence of β3-adrenoceptors causing a negative inotropic effect has been suggested (although the evidence is not unequivocal; for review, see Kaumann & Molenaar, 1997; Brodde & Michel, 1999). Atypical β-adrenoceptors causing a positive inotropic and chronotropic effect have been found in the heart of humans, rats, mice and ferrets both under in vitro and in vivo conditions (for review, see Kaumann & Molenaar, 1997; Brodde & Michel, 1999). The positive inotropic and chronotropic effects of an agonist at this receptor, CGP 12177, although abolished in double β1-/β2-adrenoceptor knockout mice, remained intact in β2-adrenoceptor knockout mice, indicating an obligatory role of the β1-adrenoceptor (Kaumann et al., 2001). Accordingly, this cardiostimulant atypical β-adrenoceptor is now frequently referred to as the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor.

With respect to blood vessels, β3-adrenoceptor mRNA has been identified in rat aortic endothelial cells (Rautureau et al., 2002) and portal vein myocytes (Viard et al., 2000) and vasorelaxant β3-adrenoceptors have been suggested to occur in the isolated rat carotid artery (MacDonald et al., 1999), rat thoracic aorta (Trochu et al., 1999) and canine pulmonary artery (Tagaya et al., 1999). Under in vivo conditions, activation of β3-adrenoceptors causes peripheral vasodilator effects in dogs (Shen et al., 1996) and mice (Rohrer et al., 1999) and increases blood flow to the brown adipose tissue in rats (Takahashi et al., 1992). On the other hand, the occurrence of vasorelaxant atypical β-adrenoceptors was proposed for the following isolated vessels of the rat: aorta (Doggrell, 1990; Oriowo, 1995; Shafiei & Mahmoudian, 1999; Brawley et al., 2000a), mesenteric artery (branches with small diameter: Torrens et al., 2002), carotid artery (Oriowo, 1994; 1995) and pulmonary vessels (Dumas et al., 1998). Moreover, both β3-adrenoceptors and atypical β-adrenoceptors may contribute to the relaxation of the human internal mammary artery (Shafiei et al., 2000). In a study on the (phenylephrine-constricted) rat aorta, Brahmadevara et al. (2003) reached the conclusion that the vasorelaxant effects of a series of β3-adrenoceptor agonists neither involve the β3-adrenoceptor nor the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor. Although Brahmadevara et al. (2003) reason whether the vasorelaxant effects of the drugs might be due to an antagonism towards α1-adrenoceptors, the possibility has to be considered that they act via an atypical β-adrenoceptor different from the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor.

With respect to the rat mesenteric artery (main vessel), in which the three β3-adrenoceptor agonists ZD 2079, ZD 7114 and ICI 215001 elicited a propranolol-resistant vasorelaxant effect (Sooch & Marshall, 1997), the receptor mediating these effects is unclear. Although Sooch & Marshall (1997) conclude that atypical β-adrenoceptors are involved, the view that the three drugs act via β3-adrenoceptors would also be very plausible. Hence, the goal of our study was to determine the type of β-adrenoceptors involved in this preparation and to study whether these receptors are located in the endothelium. For determination of the receptor subtype, selective β3-adrenoceptor agonists and nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists (activating both β3-adrenoceptors and atypical β-adrenoceptors) were used. In addition, β-adrenoceptor antagonists with potency at β3-adrenoceptors and/or at atypical β-adrenoceptors like SR 59230A, bupranolol and CGP 20712 were examined.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Male Wistar rats (220–410 g) were killed by decapitation. The mesenteric artery was isolated, removed carefully to prevent endothelium damage, cleared of fat and connective tissue and cut into 3 mm rings. In some rings, the endothelium was removed by gentle rubbing of the intimal surface with small pincers. Then all rings were suspended on stainless-steel wires in a 10 ml organ bath containing Krebs solution composed as follows (mM): NaCl, 118; KCl, 4.8; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 24; KH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 11; EDTA, 0.03. The bath fluid (maintained at 37°C) was gassed continuously with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and replaced every 20 min. After 1 h of stabilization under a resting tension of 10 mN, experiments were performed. Muscle tension was recorded by a force–displacement transducer (PIM 100RE, BIO-SYS-TECH, Białystok, Poland) and displayed on a computer.

Concentration–response curves

After the equilibration period, rings were constricted with phenylephrine (1 μM) (S1). In some experiments, serotonin (5-HT; 2 μM), prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α; 10 μM) or the thromboxane A2 mimetic U44069 (0.1 μM) were used as vasoconstrictor agents. The functionality of the endothelium was checked by the presence of at least 80% relaxation in response to acetylcholine (1 μM). In denuded rings, endothelium removal was confirmed by the absence of acetylcholine-induced relaxation. After washout, some rings were treated with an antagonist while control tissues received the respective vehicle. Since the maximal β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation crucially depends on the level of the tone of the tissue (for review, see Guimarães & Moura, 2001) and since bupranolol, CGP 20712 and SR 59230A diminished the vasoconstrictor tone induced by phenylephrine (see Results), these antagonists were studied in tissues that displayed a relatively high response to phenylephrine and/or the phenylephrine-induced contraction was repeated once or twice in order to obtain the same level of tone as in antagonist-free experiments. After 30 min of incubation with the antagonists, the rings were constricted again with phenylephrine 1 μM or serotonin 2 μM (S2) and cumulative concentration–response curves to agonists were conducted. After washing, tissues were contracted with the vasoconstrictor under study for the last time (S3) to check the endothelium function by the presence of acetylcholine-induced relaxation.

Drugs used

The drugs used were: phenylephrine, serotonin (creatinine sulphate complex), U 44069 (9,11 -dideoxy-9α, 11α-epoxymethano-prostaglandin F2α), acetylcholine chloride, isoprenaline bitartrate, propranolol hydrochloride, CGP 20712 (2-hydroxy-5(2-((2-hydroxy-3-4(1-methyl-4-trifluoromethyl)1H-imidazole-2-yl)-phenoxy)propyl)amino)ethoxy)-benzamide monomethane sulphonate), prazosin hydrochloride (Sigma, Steinhein, Germany), prostaglandin F2α (free acid; ICN), fenoterol (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), CGP 12177 hydrochloride (±)-4-[3-[(1, 1-dimethylethyl)amino]-2-hydroxypropoxy]-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one hydrochloride, cyanopindolol hemifumarate, BRL 37344 ((R*,R*)-((±)-4-[2-[(3-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl) amino]-propyl]phenoxyacetic acid), ICI 118551 (erythro-(±)-1-(7-methylindan-4-yloxy)-3-isopropylaminobutan-2-ol) (Tocris, Bristol, U.K.), ZD 2079 ((R)-N-(2-[4-(carboxymethyl)phenoxy]ethyl-N-(β-hydroxyphenethyl) ammonium chloride) (Astra Zeneca, Macclesfield, U.K.), CL 316243 ((R, R)-5-[2-[[2-(3-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethylamino]propyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-2,2-dicarboxylate) (American Cyanamid Company), ketanserin tartrate (Janssen, Beerse, Belgium), bupranolol (Schwarz Pharma, Monheim, Germany), SR 59230A (3-(2-ethylphenoxy)-1-[(1S)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphth-1-ylamino]-(2S)-2-propanol oxalate) (Sanofi, Milan, Italy). Cyanopindolol and ZD 2079 were dissolved in a mixture of water and dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), SR 59230A was dissolved in DMSO, prazosin was dissolved in a mixture of DMSO and 0.01 M HCl, ketanserin, PGF2α and U44069 were dissolved in ethanol and serotonin was dissolved in 0.1 N HCl such that the final concentration of the solvent in the organ bath was less than 0.1% v v−1. All other drugs were dissolved in distilled water.

Calculations and statistical analysis

Responses to agonists were calculated as percentage change in the maximal tension of vessel rings after addition of the respective vasoconstrictor and expressed as mean±s.e.m. of n experiments. Mean concentration–response curves to agonists were analysed by fitting to a four-parameter logistic equation (given below) using nonlinear regression (Graph Pad Prism):

|

where X is the logarithm of the molar concentration of the agonist and Y is the response. To assess the potency of the β-adrenoceptor agonists, maximum responses (Emax) and pD2 values were obtained. pD2 values were determined according to the equation pD2=−log EC50, where EC50 is the concentration (M) of the agonist that produces 50% of its maximum response. The potency of β-adrenoceptor antagonists (pA2) was calculated from the equation: pA2=log(CR−1)−log[B], where [B] is the molar concentration of the antagonist and CR is the concentration ratio of the EC50 values in the presence and absence of the antagonist.

Statistical analyses were performed using the t-test for unpaired data. When two or more treatment groups were compared to the same control, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett test was used. Differences were considered as significant when P<0.05.

Results

General

The vasoconstrictors under study, phenylephrine (0.001–30 μM), prostaglandin F2α (0.1–300 μM), the thromboxane A2 mimetic U44069 (0.001–10 μM) and serotonin (0.01–100 μM), induced a concentration-dependent contraction of rat mesenteric artery rings (pD2=6.86±0.05, n=7; 4.78±0.05, n=3; 6.85±0.05, n=3; 6.19±0.07, n=3, respectively). For the subsequent experiments, a single concentration of phenyleph-rine – 1 μM, PGF2α – 10 μM, U44069 – 0.1 μM and 5-HT – 2 μM were chosen, which produced a comparable degree of contraction (about 4.1–4.7 mN before administration of β-adrenoceptor agonists). These concentrations were approximately equivalent to EC80, EC50, EC50 and EC60, respectively.

Influence of antagonists on phenylephrine- and serotonin-induced contraction

As shown in Table 1, the size of contraction induced by the second administration of phenylephrine or serotonin (S2) increased by about 15–20% compared to the first one (S1). The nonselective β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol 0.3 μM, the β2-adrenoceptor antagonist ICI 118551 1 μM and removal of endothelium had no effect on the phenyle-phrine-elicited contraction. However, the nonselective β-adrenoceptor receptor antagonist bupranolol 10 μM, the β1-adrenoceptor antagonist CGP 20712 10 μM and the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist SR 59230A 1 μM diminished the phenylephrine-evoked contraction by about 35, 20 and 10%, respectively (Table 1). In order to obtain a comparable tone under all conditions, the three β-adrenoceptor antagonists were studied in tissues exhibiting a relatively high response to phenylephrine or phenylephrine 1 μM-evoked contraction was repeated once or twice more in those tissues. In this way, the tone of the rings was about 4.4 mN immediately prior to administration of the β-adrenoceptor agonists in all experimental groups contracted with phenylephrine (for S2 values, see Table 1). In rings preconstricted with serotonin, bupranolol 10 μM did not affect the level of the contraction by itself (Table 1). The α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin 10 μM completely abolished the vasoconstriction induced by phenylephrine without affecting that evoked by serotonin. The serotonin-elicited constriction of the rat isolated mesenteric artery was almost completely abolished by the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin 300 nM (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effects of β-adrenoceptor antagonists and of endothelium removal on contractile responses induced by phenylephrine and serotonin in the rat mesenteric artery

| Tension (mN) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasoconstricting agent | Group | n | S1 before antagonist | S2 after antagonist | S2/S1 (%) |

| Phenylephrine 1 μM | Control rings | 86 | 3.7±0.1 | 4.4±0.1 | 118.9±2.7 |

| Propranolol (0.3 μM) | 24 | 3.7±0.1 | 4.6±0.1 | 124.3±2.7 | |

| CGP 20712 (10 μM) | 20 | 4.7±0.2 | 4.6±0.2 | 97.9±4.3*** | |

| ICI 118551 (1 μM) | 17 | 3.7±0.2 | 4.2±0.2 | 113.5±5.4 | |

| Bupranolol (10 μM) | 17 | 5.0±0.2 | 4.1±0.2 | 82.0±4.0*** | |

| Control rings – DMSO | 21 | 3.7±0.2 | 4.5±0.2 | 121.6±5.4 | |

| SR 59230A (1 μM) | 21 | 4.2±0.1 | 4.6±0.1 | 109.5±2.4* | |

| Denuded rings | 17 | 3.5±0.1 | 4.2±0.2 | 120.0±5.7 | |

| Serotonin 2 μM | Control rings | 6 | 3.9±0.2 | 4.5±0.4 | 115.4±10.3 |

| Bupranolol (10 μM) | 6 | 4.1±0.3 | 4.8±0.1 | 117.1±2.4 | |

Data are expressed as changes in isometric tension (mN) induced by phenylephrine or serotonin before (S1) and after addition of β-adrenoceptor antagonists (S2) and as the percentage of S2 over S1.

Values are shown as mean±s.e.m. for n experiments *P<0.05;

***P<0.001 compared to the respective control rings.

Influence of β-adrenoceptor agonists on phenylephrine-induced contraction

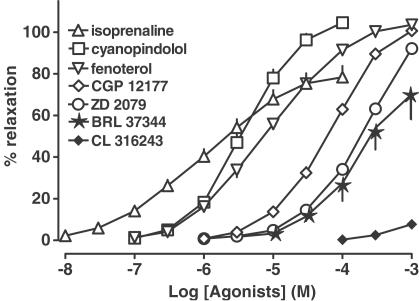

Isoprenaline, the β2-adrenoceptor agonist fenoterol, the two nonconventional partial agonists cyanopindolol and CGP 12177 and the β3-adrenoceptor agonist ZD 2079 produced a concentration-dependent relaxation of phenylephrine-preconstricted isolated mesenteric arteries (Figure 1). Full relaxation was elicited by fenoterol, cyanopindolol and CGP 12177; the shape of the concentration–response curve of ZD 2079 also suggests that this drug, which was studied up to 1 mM, causes full relaxation (Figure 1; Hill slopes: fenoterol – 0.77±0.04; cyanopindolol – 1.07±0.05; CGP 12177–1.01±0.05; ZD 2079–1.06±0.07). In the case of isoprenaline, the maximal relaxation was by about 20% lower than that of fenoterol, cyanopindolol and CGP 12177; isoprenaline differs from the latter three drugs and from ZD 2079 also with respect to the particularly low steepness of its concentration–response curve (Figure 1; Hill slope for isoprenaline – 0.62±0.03). On the basis of their pD2 values, the following rank order of potencies was obtained: isoprenaline>cyanopindolol>fenoterol>CGP 12177>ZD 2079 (Table 2). Another two β3-adrenoceptor agonists, BRL 37344 and CL 316243, showed weak potency and efficacy in relaxing rings of the mesenteric artery. The relaxation at 1 mM (the highest concentration tested) was by about 75 and 5%, respectively (Table 2, Figure 1). For these reasons, the relaxant effects of the latter two compounds were not considered in our further studies.

Figure 1.

Effects of β-adrenoceptor agonists in rat mesenteric artery. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by phenylephrine. Means±s.e.m. of four to 25 tissues for each curve. For many points s.e.m. is contained within the symbols.

Table 2.

Potencies of β-adrenoceptor agonists for their relaxant effect on phenylephrine-preconstricted rat mesenteric artery

| Agonist | n | Emax (%) | pD2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprenaline | 13 | 81.3±5.5 | 6.00±0.09 |

| Fenoterol | 8 | 103.8±1.3 | 4.98±0.09 |

| Cyanopindolol | 14 | 106.5±1.8 | 5.45±0.07 |

| +DMSO | 5 | 103.6±1.2 | 5.35±0.04 |

| CGP 12177 | 23 | 102.7±1.0 | 4.19±0.04 |

| +DMSO | 8 | 101.3±3.6 | 4.06±0.08 |

| ZD 2079 | 25 | 99.4±1.7a | 3.72±0.04 |

| +DMSO | 5 | 99.8±3.9a | 3.62±0.12 |

| BRL 37344 | 4 | 75.2±11.2a | –b |

| CL 316243 | 4 | 4.2±2.8a | –b |

Values are shown as mean±s.e.m. for n experiments.

Relaxant effect at 1 mM.

pD2 value cannot be given since the maximum effect was not reached at 1 mM.

Influence of β-adrenoceptor antagonists on relaxation induced by isoprenaline and fenoterol in phenylephrine preconstricted rings

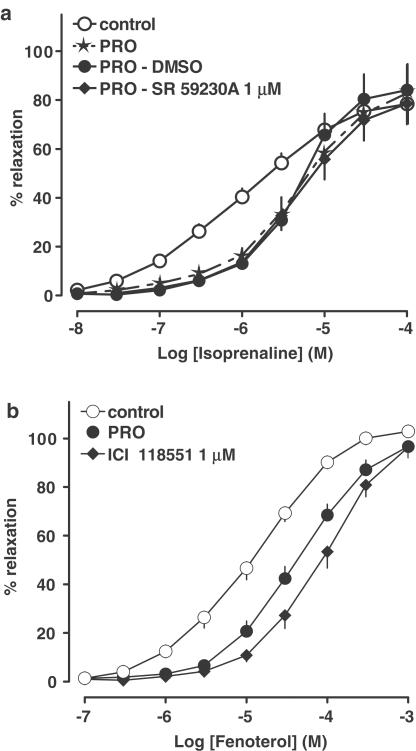

The nonselective β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol 0.3 μM shifted the concentration–response curve of isoprenaline to the right by a factor of 4.5, without affecting the maximum relaxation (Figure 2a, for pA2 value, see Table 3). The shift was greater at the lower concentrations of isoprenaline; following administration of propranolol the steepness of the concentration–response curve of isoprenaline was increased (Figure 2a; Hill slopes: control – 0.62±0.03; propranolol – 0.95±0.05; ***P<0.001). Additional administration of the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist SR 59230A 1 μM did not affect the concentration–response curve of isoprenaline obtained in the presence of propranolol and DMSO, the vehicle of SR 59230A (Figure 2a, for pA2 value, see Table 3). Figure 2b shows that the concentration–response curve for fenoterol was shifted 4.0- and 7.9-fold to the right by propranolol 0.3 μM and the β2-adrenoceptor antagonist ICI 118551 1 μM, respectively, with no reduction in the maximum response (for pA2 values, see Table 3). Both β-adrenoceptor antagonists also produced a significant steepening of the fenoterol concentration–response curve (Hill slopes: control – 0.77±0.04; propranolol – 0.94±0.03; **P<0.01; ICI 118551 – 0.96±0.03; **P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Influence of β-adrenoceptor antagonists on relaxation induced by isoprenaline and fenoterol in the rat mesenteric artery preconstricted with phenylephrine. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by phenylephrine. PRO − propranolol 0.3 μM. Means±s.e.m. of four to 13 tissues for each curve. For many points s.e.m. is contained within the symbols.

Table 3.

Potencies of β-adrenoceptor antagonists for their antagonistic effect against the relaxant effects of β-adrenoceptor agonists in phenylephrine-preconstricted rat mesenteric artery

| pA2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | CGP 20712 | IC1 118551 | Bupranolol | SR 59230A | |

| Agonist | (0.3 μM) | (10 μM) | (1 μM) | (10 μM) | (1 μM) |

| Isoprenaline | 7.0 | ND | ND | ND | <6a |

| Fenoterol | 6.9 | ND | 6.8 | ND | ND |

| Cyanopindolol | <6.5 | 5.4 | <6.0 | 5.7 | 6.7 |

| CGP 12177 | <6.5 | 5.4 | <6.0 | 5.3 | 6.5 |

| ZD 2079 | <6.5 | 5.4 | <6.0 | 5.3 | 6.7 |

Obtained in the presence of propranolol 0.3 μM. ND, not determined.

Influence of β-adrenoceptor antagonists on relaxation induced by nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists and ZD 2079 in phenylephrine preconstricted rings

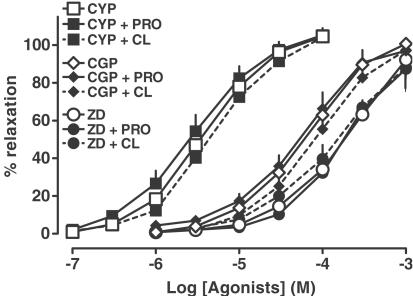

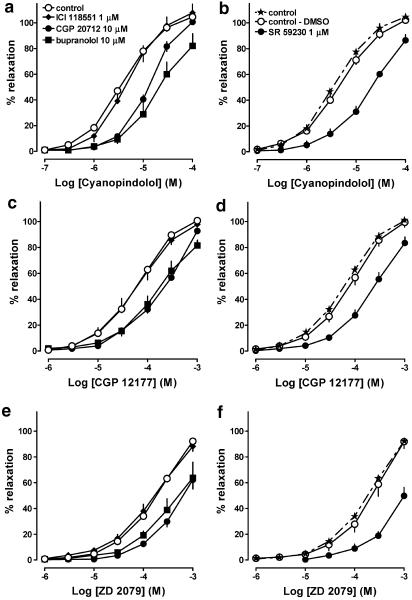

As shown in Figure 3, propranolol 0.3 μM failed to affect the concentration–response curves for the nonconventional β-adrenoceptor agonists cyanopindolol and CGP 12177 and the β3-adrenoceptor agonist ZD 2079. The influence of ICI 118551, the β1-adrenoceptor antagonist CGP 20712 (used here at a high concentration, also known to antagonize atypical β-adrenoceptors) and the nonselective β-adrenoceptor antagonist bupranolol on the relaxation of mesenteric arteries elicited by cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 is shown in Figure 4a, c, e, respectively (for pA2 values, see Table 3). Thus, ICI 118551 1 μM did not affect the vasodilator responses to all agonists, whereas CGP 20712 10 μM and bupranolol 10 μM shifted their concentration–response curves to the right, yielding pA2 values of about 5.5.

Figure 3.

Influence of propranolol 0.3 μM (PRO) and CL 316243 60 μM (CL) on relaxation induced by cyanopindolol (CYP), CGP 12177 (CGP) and ZD 2079 (ZD) in the rat mesenteric artery preconstricted with phenylephrine. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by phenylephrine. Means±s.e.m. of three to 25 tissues for each curve. For many points s.e.m. is contained within the symbols.

Figure 4.

Influence of β-adrenoceptor antagonists on relaxation induced by cyanopindolol (a, b), CGP 12177 (c, d) and ZD 2079 (e, f) in rat mesenteric artery preconstricted with phenylephrine. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by phenylephrine. Note that for SR 59230A, which was dissolved in DMSO, a separate control curve was determined. Means±s.e.m. of three to 25 tissues for each curve. For many points s.e.m. is contained within the symbols.

We also examined the influence of the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist SR 59230A on the vasodilator effect of cyanopindolol (Figure 4b), CGP 12177 (Figure 4d) and ZD 2079 (Figure 4f) (for pA2 values, see Table 3). Since SR 59230A was dissolved in DMSO, we performed additional experiments, in which we proved that DMSO had no effect on the concentration–response curves for these three agonists. SR 59230A 1 μM shifted the concentration–response curves for cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079, respectively, to the right, yielding pA2 values of about 6.6.

Figure 4a and c also shows that CGP 20712 did not affect the maximal response to cyanopindolol and CGP 12177. With respect to the interaction of ZD 2079 with CGP 20712 (Figure 4e) and of each of the three agonists with bupranolol (Figure 4a, c and e) or SR 59230A (Figure 4b, d and f), a depression of the maximal relaxation cannot be definitely excluded on the basis of our experiments since we did not use concentrations of the agonists exceeding 0.1 mM (cyanopindolol) and 1 mM (CGP 12177 and ZD 2079). The shape of the concentration–response curves, however, also strongly suggests that in the latter cases the antagonists did not affect the maximum relaxant response of the agonists. The Hill slopes obtained for the concentration–response curves of the three agonists in the presence of CGP 20712, bupranolol and SR 59230A were close to unity (data not shown).

Influence of CL 316243 on relaxation induced by nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists and ZD 2079 in phenylephrine preconstricted rings

In additional experiments, we examined the influence of a high concentration of CL 316243 on the vasorelaxation evoked by cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079. We chose a concentration of CL 316243 (60 μM) which does not possess any vasodilator action by itself (see Figure 1). As shown in Figure 3, we did not observe any effect of this β3-adrenoceptor agonist on the concentration–response curves for all the three agonists.

Influence of cyanopindolol and fenoterol on contraction induced by various vasoconstrictors

As shown in Figure 5a, the extent of the vasorelaxant effect of the nonconventional partial agonist cyanopindolol and the β2-adrenoceptor agonist fenoterol is dependent on the vasoconstricting stimulus. Cyanopindolol 0.1 mM and fenoterol 1 mM fully relaxed rings contracted with phenylephrine 1 μM. The relaxation evoked by the same concentrations of cyanopindolol and fenoterol was less by about 20% in rings preconstricted with serotonin 2 μM, and it was very small or even undetectable in vessels constricted with PGF2α 10 μM and U44069 0.1 μM. The vasorelaxant effect of cyanopindolol was inhibited to a comparable degree by bupranolol 10 μM in rings preconstricted with phenylephrine and serotonin (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Effects of cyanopindolol ((a) – 100 μM; (b) −10 and 100 μM) and fenoterol ((a) −1 mM) in rat mesenteric artery preconstricted with phenylephrine ((a, b); PHE; 1 μM), serotonin ((a, b); 5-HT; 2 μM), PGF2α ((a); PGF; 10 μM) and U 44069 ((a); 0.1 μM). Some experiments were performed in the presence of bupranolol (b). Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by respective compound. Means±s.e.m. of three to 15 tissues. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared to the corresponding control.

Influence of endothelium removal on relaxation induced by nonconventional partial agonists and ZD 2079 in phenylephrine preconstricted rings

Removal of endothelium shifted the concentration–response curves for both nonconventional β-adrenoceptors agonists and ZD 2079 to the right (Figure 6). Since concentrations higher than 0.1 mM (cyanopindolol) and 1 mM (CGP 12177 and ZD 2079) were not studied, the question whether endothelium removal also depressed the maximal relaxant effect cannot be answered. In order to obtain a rough parameter for the extent of effect of endothelium removal, the negative logarithms of the concentrations of the three agonists causing a relaxation of endothelium-denuded arterial rings by 50% were determined (pEC50%) and compared to the pD2 values obtained for the control curves. The respective values were 4.40±0.16 (n=6) and 5.45±0.07 (n=14) for cyanopindolol, 3.29±0.11 (n=5) and 4.19±0.04 (n=23) for CGP 12177 and 3.09±0.09 (n=6) and 3.72±0.04 (n=25) for ZD 2079. In each case, pD2 and pEC50% values were significantly (P<0.001) different.

Figure 6.

Influence of endothelium removal on relaxation induced by cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 in rat mesenteric artery preconstricted with phenylephrine. Results are expressed as percentage relaxation of tone induced by phenylephrine. Means±s.e.m. of five to 25 tissues for each curve. For many points s.e.m. is contained within the symbols.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to determine the pharmacological properties of the non-β1-/non-β2-adrenoceptors relaxing the rat mesenteric artery in terms of β3- or atypical β-adrenoceptors and to study whether these receptors are located endothelially.

Effects of β-adrenoceptor agonists

Our study was carried out with the nonselective β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline, the β2-adrenoceptor agonist fenoterol, the selective β3-adrenoceptor agonists BRL 37344, CL 316243 and ZD 2079 and the nonconventional partial agonists CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol. The term ‘nonconventional partial agonists' encompasses drugs which activate β3- and atypical β-adrenoceptors at concentrations much higher than those at which they block β1- and/or β2-adrenoceptors. All β-adrenoceptor agonists caused a concentration-dependent relaxation of isolated mesenteric arteries precontracted with phenylephrine. The rank order of potencies was: isoprenaline>cyanopindolol>fenoterol>CGP 12177>ZD 2079⩾BRL 37344⋙CL 316243. Full relaxation was induced by cyanopindolol, fenoterol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079. In contrast, isoprenaline relaxed rat mesenteric arteries maximally by about 80% and the relaxation obtained for the highest concentration of BRL 37344 (1 mM) was about 75%. CL 316243, the most selective agonist at the rat β3-adrenoceptor developed so far (Bloom et al., 1992), at concentrations up to 1 mM was almost devoid of vasorelaxant activity.

The fact that β3-adrenoceptor agonists caused relaxation might suggest the involvement of β3- rather than atypical β-adrenoceptors in this effect. However, a detailed comparison of the order of potencies rather argues for the contrary conclusion. Since marked species differences have been determined in the action of β3-adrenoceptor and partial nonconventional β-adrenoceptor agonists (e.g. Cohen et al., 1999; Gauthier et al., 1999), we are focusing on the rat. Thus, for the β3-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of the colon, the following rank order of potencies (pD2 values in parentheses) was determined: BRL 37344 (9.1)≈CL 316243 (9.0)>SR 58611 (8.2)>ZD 2979 (7.0)≈cyanopindolol (7.0)≈CGP 12177 (6.9) (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996; Brahmadevara et al., 2003). CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol were only partial agonists in this experimental model. Moreover, β3-adrenoceptor agonists (CL 316243, BRL 37344 and/or SR 58611) were also more potent than CGP 12177 in other β3-adrenoceptor models including relaxation of ileum (Roberts et al., 1999), distal colon (Oriowo, 1995) and stomach fundus (Cohen et al., 1999), as well as lipolysis in white adipocytes (Galitzky et al., 1997) or thermogenesis in brown fat cells both in vitro (Zhao et al., 1998) and in vivo (Malinowska & Schlicker, 1997).

On the other hand, responses mediated by the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor are induced by nanomolar or low micromolar concentrations of nonconventional β-adrenoceptor agonists, whereas micromolar concentrations of preferential β3-adrenoceptor agonists do not possess such an activity. Thus, in the heart, CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol induced positive chronotropic and inotropic effects (in vitro: pD2 from 7.1 to 7.7; Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996; Cohen et al., 1999 and in vivo: pED50 8.0 and 7.3, respectively; Malinowska & Schlicker, 1997), whereas β3-adrenoceptor agonists (CL 316243, BRL 37344, ZD 2079 and/or SR 58611; at concentrations up to at least 6 μM or doses up to 10 μmol kg−1) were devoid of an effect. Our agonist data only partially resemble the properties of the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor; there are at least three differences. (i) The agonistic effects of CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol occur in a relatively high concentration range. This was also previously shown for the atypical β-adrenoceptors in the rat aorta (Shafiei & Mahmoudian, 1999; Brawley et al., 2000a; Brahmadevara et al., 2003), carotid artery (Oriowo, 1994) and mesenteric artery (small branches; Torrens et al., 2002). (ii) The order of potency for the two nonconventional partial agonists (cyanopindolol>CGP 12177) is opposite to that for the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptor; the same has been shown for the atypical vasorelaxant receptor in the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a; Brahmadevara et al., 2003). (iii) The potencies of some of the selective β3-adrenoceptor agonists are only slightly lower than those of CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol. This is in harmony with the findings for the atypical β-adrenoceptors in the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a; Brahmadevara et al., 2003) and carotid artery (Oriowo, 1994).

Interaction of β-adrenoceptor agonists and antagonists

First, experiments were performed to exclude the involvement of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in the relaxant effects of cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 (BRL 37344 could not be used for this purpose since a complete concentration–response curve was not obtained with this agonist). The nonselective β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol and the selective β2-adrenoceptor antagonist ICI 118551 used at concentrations that antagonized the vasorelaxant effects of isoprenaline and/or fenoterol indeed failed to affect the vasorelaxant effects elicited by cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079. The relatively low pA2 values of propranolol and ICI 118551 against isoprenaline and/or fenoterol may be related to the fact that the concentration–response curves of these agonists had a low steepness, possibly suggesting that they interact with more than one receptor.

Next, we used three drugs known to possess antagonistic effects at β3- and/or atypical β-adrenoceptors, that is, bupranolol, CGP 20712 and SR 59230A. Unfortunately, only one concentration of these drugs could be examined since they relaxed the mesenteric artery by themselves excluding the use of higher concentrations (for a more detailed discussion, see below). Moreover, the effects of cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 occurred at very high concentrations. Bupranolol shifted the concentration–response curve of each of these agonists to the right. The pA2 value is somewhat lower than that obtained at the β3- or the low-affinity state β1-adrenoceptor in rat tissues (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996), and virtually identical to that obtained at the atypical β-adrenoceptor mediating vasorelaxation of the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a).

High concentrations of CGP 20712 have been shown to antagonize the positive chronotropic and inotropic action in the rat heart (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996; Malinowska & Schlicker, 1996; 1997) and the relaxation of the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a), but failed to counteract or hardly inhibited the β3-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of rat ileum (Roberts et al., 1999) and colon (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996), lipolysis in white adipocytes (Galitzky et al., 1997; Carpéné et al., 1999) or thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue in pithed rats (Malinowska & Schlicker, 1997). The antagonistic effect of CGP 20712 in our study suggests that atypical β-adrenoceptors rather than β3-adrenoceptors are involved in the vasorelaxant effects of cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079.

Another argument speaking in favour of atypical β-adrenoceptors rather than β3-adrenoceptors are the findings with the selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL 316243. CL 316243 showed a very slight vasorelaxant effect and the possibility had to be considered that this drug is a partial agonist at the β3-adrenoceptor. As a partial agonist, it should antagonize the effects of the full agonists cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079. This, however, was not observed. The lack of an inhibitory influence of β3-adrenoceptor agonists (CL 316243, BRL 37344 or ZD 2079) on the activation of atypical β-adrenoceptors by nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists was also described previously in the rat aorta (Oriowo, 1994) and heart (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996; Malinowska & Schlicker, 1996).

The antagonistic effect of the β3-adrenoceptor antagonist SR 59230A against the vasorelaxant actions of the nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists and ZD 2079 observed in our experiments does not necessarily speak against the involvement of atypical β-adrenoceptors. Thus, SR 59230A also acts as a weak antagonist against atypical β-adrenoceptors in the rat heart in vitro (Kaumann & Molenaar, 1996) and in vivo (Malinowska & Schlicker, 1997) and in rat fat cells (Galitzky et al., 1997). The fact that SR 59230A failed to affect the vasorelaxant effect of isoprenaline studied in the presence of propranolol might mean that atypical β-adrenoceptors do not contribute to the complex vasorelaxant effect of isoprenaline. The reason why SR 59230A had an antagonistic effect at the atypical β-adrenoceptor in the rat mesenteric artery but not at the atypical β-adrenoceptor in the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a) is difficult to understand; this discrepancy is the more surprising since the two receptors are very similar in many other respects.

The vasoconstrictor tone – quantitative and qualitative aspects

In most of the experiments of the present study, the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine was used to precontract the mesenteric artery. As already mentioned, three antagonists decreased the precontracted vessel by themselves. The β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation crucially depends on the level of the tone of the tissue (for review see Guimarães & Moura, 2001). For this reason, we added the three antagonists either to vascular specimens showing a relatively high contraction in response to the first administration of phenylephrine (S1), or we repeated the phenylephrine-induced contraction once or twice more than in tissues used for antagonist-free experiments. The latter procedure appears to be justified since the concentration of phenylephrine used is close to that producing the maximum effect. Since the vascular tone was virtually identical in all tissues immediately before giving the agonist under study (S2), we are convinced that the argument that the antagonistic effects of the three antagonists solely reflect unspecific effects due to the reduction of the vascular tone is not very plausible.

In the study by Brahmadevara et al. (2003), cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and BRL 37344 failed to produce relaxation when rat aortic rings were preconstricted with PGF2α. Therefore, the authors concluded that the vasodilatory effects of these drugs on phenylephrine-constricted aortic rings may be related to an interference with the α1-adrenoceptor signalling pathway. However, our results do not confirm this hypothesis for the mesenteric artery. We found that the vasodilator effect of cyanopindolol (and of fenoterol, examined in parallel) was retained by 80% in rings preconstricted with serotonin. The vasoconstrictor effect of this amine was resistant to the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin, but was reduced by the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin. Bupranolol inhibited the effect of cyanopindolol to a comparable degree both in phenylephrine- and serotonin-preconstricted vessels and did not relax mesenteric rings constricted with serotonin. The latter finding also argues against the view that the antagonistic effect of bupranolol against cyanopindolol is solely due to an unspecific effect related to its slight vasorelaxant effect in phenylephrine-constricted arteries.

Involvement of endothelium in the vasorelaxant effects of atypical β-adrenoceptors

Removal of endothelium diminished the effects of cyanopindolol, CGP 12177 and ZD 2079. Thus, we conclude that part of the atypical β-adrenoceptors is located in the endothelium. The degree of attenuation of the vasorelaxant effect appears to differ between cyanopindolol (highest), CGP 12177 and ZD 2079 (lowest). This discrepancy markedly contrasts with the virtually identical properties of the three agonists with respect to their interaction with five β-adrenoceptor antagonists and with CL 316243 and cannot be explained satisfactorily at the moment. Similarly, Brawley et al. (2000b) found that the removal of endothelium or the presence of L-NAME (NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; an inhibitor of the biosynthesis of nitric oxide) diminished the vasorelaxant actions of cyanopindolol and CGP 12177 in the rat isolated aorta (preconstricted with noradrenaline) and only tended to do that in the case of ZD 2079. In contrast, Brahmadevara et al. (2003), in experiments also performed in the rat isolated aorta (preconstricted with phenylephrine), did not determine any influence of endothelium removal on relaxation to CGP 12177 and SR 58611A. Thus, further studies are required for explanation of the exact role of endothelium for the vasodilatory action of atypical β-adrenoceptors.

Conclusions

The present study reveals that the non-β1-/non-β2-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of the rat mesenteric artery does not involve β3-adrenoceptors; moreover, the involvement of unspecific effects or an interference with α1-adrenoceptors is also unlikely. The receptors involved are partially located in the endothelium and can be classified as atypical β-adrenoceptors that resemble the low-affinity state of the β1-adrenoceptors in the heart in some respects (e.g. activation by the nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists cyanopindolol and CGP 12177 and blockade by high concentrations of bupranolol and CGP 20712). However, there are three differences with respect to the action of the nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists when compared to the cardiostimulatory β-adrenoceptor: (1) lower potency; (2) opposite rank order of potency, that is, cyanopindolol>CGP 12177; (3) potency of some β3-adrenoceptor agonists (ZD 2079 and BRL 37344, as opposed to CL 316243) not much lower than that of the nonconventional partial β-adrenoceptor agonists. Despite some discrepancies, the latter properties have also been described for the vasorelaxant atypical β-adrenoceptor in the rat aorta (Brawley et al., 2000a; Brahmadevara et al., 2003) and carotid artery (Oriowo, 1994). The vasorelaxant atypical β-adrenoceptor may, therefore, be different from the cardiostimulant atypical β-adrenoceptor although further studies with antagonists are needed to reach a definite conclusion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the State Committee for Scientific Research (Poland; grant no. 3 PO5F 040 22). We wish to thank Mrs I. Malinowska for her skilled technical assistance and the pharmaceutical companies SchwarzPharma AG, American Cyanamid Company and Astra Zeneca for gifts of drugs.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- 5-HT

serotonin

- PGF2α

prostaglandin F2α

- PHE

phenylephrine

References

- BLOOM J.D., DUTIA M.D., JOHSON B.D., WISSNER A., BURNS M.G., BURNS LARGIS E.E., DOLAN J.A., CLAUS T.H. Disodium (R,R)-5-[2-[(3-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl]-amino-propyl]-l,3-benzodioxole-2,2-dicarboxylate (CL 316,243): a potent β-adrenergic agonist virtually specific for β3 receptors. A promising antidiabetic and antiobesity agent. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3081–3084. doi: 10.1021/jm00094a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAHMADEVARA N., SHAW A.M., MACDONALD A. Evidence against β3-adrenoceptors or low affinity state of β1-adrenoceptors mediating relaxation in rat isolated aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:99–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAWLEY L., SHAW A.M., MACDONALD A. β1-, β2- and atypical β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in rat isolated aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000a;129:637–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAWLEY L., SHAW A.M., MACDONALD A. Role of endothelium/nitric oxide in atypical beta-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in rat isolated aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000b;398:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRODDE O.-E., MICHEL M.C. Adrenergic and muscarinic receptors in the human heart. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:651–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARPÉNÉ C., GALITZKY J., FONTANA E., ATGIÉ C., LAFONTAN M., BERLAN M. Selective activation of β3-adrenoceptors by octopamine: comparative studies in mammalian fat cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1999;359:310–321. doi: 10.1007/pl00005357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN M.L., BLOOMQUIST W., KRIAUCIUNAS A., SHUKER A., CALLIGARO D. Aryl propanolamines: comparison of activity at human β3 receptors, rat β3 receptors and rat atrial receptors mediating tachycardia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOGGRELL S.A. Relaxant and β2-adrenoceptor blocking activities of (±)-, (+) and (−)-pindolol on the rat isolated aorta. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990;42:444–446. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb06590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMAS M., DUMAS J.-P., BARDOU M., ROCHETTE L., ADVENIER C., GIUDICELLI J.-F. Influence of β-adreno-ceptor agonists on the pulmonary circulation. Effects of a β3-adrenoceptor antagonist SR 59230A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;348:223–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALITZKY J., LANGIN D., VERWAERDE P., MONTASTRUC J.-L., LAFONTAN M., BERLAN M. Lipolytic effects of conventional β3-adrenoceptor agonists and of CGP 12,177 in rat and human fat cells: preliminary pharmacological evidence for a putative β4-adrenoceptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1244–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUTHIER C., TAVERNIER G., TROCHU J.N., LEBLAIS V., LAURENT K., LANGIN D., ESCANDE D., LE MAREC H. Interspecies differences in the cardiac negative inotropic effects of β3-adrenoceptor agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;290:687–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUIMARÃES S., MOURA D. Vascular adrenoceptors: an update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:319–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., ENGELHARDT S., HEIN L., MOLENAAR P., LOHSE M. Abolition of (−)-CGP 12177-evoked cardiostimulation in double beta1/beta2-adrenoceptor knockout mice. Obligatory role of beta1-adrenoceptors for putative beta4-adrenoceptor pharmacology. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2001;363:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s002100000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., MOLENAAR P. Differences between the third cardiac β-adrenoceptor and the colonic β3-adrenoceptor in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:2085–2098. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., MOLENAAR P. Modulation of human cardiac function through 4 beta-adrenoceptor populations. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1997;355:667–681. doi: 10.1007/pl00004999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD A., MCLEAN M, MACAULAY L., SHAW A.M. Effects of propranolol and L-NAME on beta-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in rat carotid artery. J. Anton. Pharmacol. 1999;19:145–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.1999.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALINOWSKA B., SCHLICKER E. Mediation of the positive chronotropic effect of CGP 12177 and cyanopindolol in the pithed rat by atypical β-adrenoceptors, different from β3-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:943–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALINOWSKA B., SCHLICKER E. Further evidence for differences between cardiac atypical β-adrenoceptors and brown adipose tissue β3-adrenoceptors in the pithed rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1307–1314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORIOWO M.A. Atypical β-adrenoceptors in the rat isolated common carotid artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:699–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORIOWO M.A. Different atypical β-adrenoceptors mediate isoprenaline-induced relaxation in vascular and non-vascular smooth muscles. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL 269–PL 275. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAUTUREAU Y., TOUMANIANTZ G., SERPILLON S., JOURDON P., TROCHU J.N., GAUTHIER C. Beta 3-adrenoceptor in rat aorta: molecular and biochemical characterization and signalling pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:153–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS S.J., PAPAIOANNOU M., EVANS B.A., SUMMERS R.J. Characterization of β-adrenoceptor mediated smooth muscle relaxation and the detection of mRNA for β1-, β2- and β3-adrenoceptors in rat ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:949–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROHRER D.K., CHRUSCINSKI A., SCHAUBLE E.H., BERNSTEIN D., KOBILKA B.K. Cardiovascular and metabolic alternation in mice lacking both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16701–16708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAFIEI M., MAHMOUDIAN M. Atypical β-adrenoceptors of rat thoracic aorta. Gen. Pharmacol. 1999;32:557–562. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAFIEI M., OMRANI G., MAHMOUDIAN M. Coexistence of at least three distinct beta-adrenoceptors in human internal mammary artery. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2000;87:275–286. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.87.2000.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN Y.T., CERVONI P., CLAUS T., VAINER S.F. Differences in β3-adrenergic receptor cardiovascular regulation in conscious primates, rats and dogs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;278:1435–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOOCH S., MARSHALL I. Atypical β-adrenoceptors in the rat vasculature. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;812:211–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAGAYA E., TAMAOKI J., TAKEMURA H., ISONO K., NAGAI A. Atypical adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of canine pulmonary artery through a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent pathway. Lungs. 1999;177:321–332. doi: 10.1007/pl00007650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI H., YOSHIDA T., NISMURA N., NAKANISHI T., KONDO M., YOSHIMURA M. Beta3-adrenergic agonist, BRL-26830A, and alpha/beta blocker, arotinolol, markedly increase regional blood flow in the brown tissue in anaesthetized rats. Jpn. Circ. J. 1992;56:936–942. doi: 10.1253/jcj.56.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORRENS C., BRAWLEY L., ITOH S., POSTON L., HANSON M.A. Atypical β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatation in rat isolated small mesenteric arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:59. [Google Scholar]

- TROCHU J.-N., LEBLAIS V., RAUTUREAU Y., BÉVÉRELLI F., LE MAREC H., BERDEAUX A., GAUTHIER C. Beta 3-adrenoceptor stimulation induces vasorelaxation mediated essentially by endothelium-derived nitric oxide in rat thoracic aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:69–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIARD P., MACREZ N., COUSSIN F., MOREL J.-L., MIRONNEAU J. Beta-3 adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in rat portal vein myocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:1497–1505. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO J., CANNON B., NEDERGAARD J. Carteolol is a weak partial agonists on β3-adrenergic receptors in brown adipocytes. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998;76:428–433. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-4-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]