Abstract

To determine the mechanisms by which cation- or anion-specific channels select between these ions, we have examined the role of electrostatic factors in a typical ligand-gated ion channel, the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3) receptor, by removal and/or insertion of rings of conserved charged residues at either end of the pore.

Neutralization of the negatively charged ring at the intracellular end of the channel (E−1′A) results in a nonselective channel (PNa/PCl=0.89).

Insertion of positively charged residues at the extracellular end of the pore either results in a nonfunctional receptor (A24′K) or one that remains cation-selective (PNa/PCl=110; S19′R).

Combining the removal of a negatively charged ring (E−1′A) with the insertion of a positively charged ring (S19′R), however, results in a channel that is predominantly anion-selective (PNa/PCl=0.37).

The data suggest that for the cation-selective 5-HT3 receptor, the control of selectivity exerted by charged rings at either end of the pore is dominated by the ring of negatively charged residues at the intracellular side of the channel. As changing the charge at this position has also been shown to change ionic selectivity in anion-selective receptors, these data suggest that electrostatic factors can control selectivity in the whole Cys-loop family.

Keywords: Ion selectivity, serotonin receptor, ligand-gated ion channel, ionotrophic receptor, 5-HT3 receptor, gating

Introduction

The 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3) receptor is a member of the Cys-loop family of ligand-gated ion channels which includes nicotinic acetylcholine (nACh), GABAA and glycine receptors (Reeves & Lummis, 2002). These receptors are pentamers, and multiple subunits have been identified for each family. Three 5-HT3 receptor subunits are known, although the A subunit is unusual in that it can form functional homopentameric receptors (Reeves & Lummis, 2002). The recent determination of a protein homologous to the extracellular domain of the nACh receptor has revealed many characteristics of the ligand binding domain of this family of proteins (Brejc et al., 2001). There is, however, currently no equivalent information on the ‘effector' region, the ion channel, which both selects and controls the ion species that move in or out of the cell.

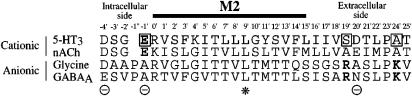

There is good evidence that the pore-lining region of ligand-gated ion channels is formed from the second transmembrane domain, M2 (Figure 1). Studies on nACh receptors have identified rings of residues in M2 which alter conductance (Imoto et al., 1988), the selectivity among monovalent (Imoto et al., 1988; Cohen et al., 1992) divalent (Bertrand et al., 1993) cations, or channel gating (Labarca et al., 1995). There is good evidence that the structure of this region in all these proteins, including the 5-HT3 receptor, is predominantly α-helical: recent studies on the latter using the substituted cysteine scanning method (SCAM) have shown that the pattern of residues that are accessible to water-soluble reagents is consistent with a predominantly α-helical structure (Reeves et al., 2001; Panicker et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Alignment of the amino-acid sequences of M2 and its flanking regions for representative cation- and anion-selective ligand-gated ion channel subunits. Sequences are shown in single-letter code for the murine 5-HT3A receptor, the α7 subunit of the chicken nACh receptor, the α1 subunit of the rat glycine receptor and the α1 subunit of the bovine GABAA receptor (North, 1995). Bold type indicates conserved charged amino-acid residues. Boxes indicate amino-acid residues that were mutated in the present study. The cytoplasmic (−4′), intermediate (−1′) and extracellular (20′) rings of charged residues bordering M2 in the cation-selective channels (Θ) as well as the conserved central leucine residue (*) are also indicated.

The ion channel coupled to the 5-HT3 receptor (Derkach et al., 1989) is a relatively nonselective cation channel, and, as in α7 nACh (Galzi et al., 1992; Corringer et al., 1999) and glycine (Keramidas et al., 2000) receptors, residues at three homologous positions in M2 have been identified as important determinants of charge selectivity (Gunthorpe & Lummis, 2001). Mutation of these three residues reverses the charge selectivity of each channel. Corringer et al. (1999) examined the individual contributions of mutations at each position to charge selectivity, and concluded that while some residue changes were ‘permissive', insertion of a proline residue was essential to convert a cationic to an anionic receptor. Such an insertion, however, may cause a structural change in the protein, thus preventing a proper dissection of the roles of charged residues in M2. Indeed, more recently, changing a single amino acid (A−1′E) at the intracellular end of the channel has been shown to reverse ion selectivity in the glycine receptor (Keramidas et al., 2002). Thus to explore if the role of the −1′ residue is confined to anion-selective receptors, and to examine ionic selectivity without the confounding issue of changing a proline residue, we have examined conserved charged residues at each end of the channel in the cation-selective 5-HT3 receptor. Our data, combined with other studies, suggest that electrostatic factors are the major determinants of ion selectivity in this family of proteins.

Methods

Materials

All cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco BRL (Paisley, U.K.), except fetal calf serum which was from Sigma (Poole, U.K.). [3H] granisetron (81 Ci mmol−1) was from DuPont (Stevenage, U.K.). The 5-HT3A receptor N-terminal domain antiserum pAb120 was generated as previously described (Spier et al., 1999). All other reagents were of the highest obtainable grade.

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were stably transfected with vectors encoding wild-type (WT) or mutant 5-HT3A(b) receptor subunits (where (b) represents the short splice variant of the 5-HT3A receptor) as described previously (Hargreaves et al., 1994). Briefly, HEK293 cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM/F12 in 7% CO2. Mutagenesis was performed using the Kunkel method (Kunkel, 1985), and following transfection, stable cell lines were selected using geneticin. Cells were grown on 18-mm2 coverslips for electrophysiological studies, in 90-mm-diameter dishes for radioligand binding studies and on 22-mm-diameter coverslips for immunocytochemistry and Ca2+ imaging studies.

Radioligand binding

This was as described previously with minor modifications (Lummis et al., 1993). Briefly, transfected HEK293 cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature: all subsequent steps were carried out at 1–4°C. Cells were scraped into 1 ml of HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) containing the following proteinase inhibitors (PI): 1 mM EDTA, 50 μg ml−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor, 50 μg ml−1 bacitracin and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride. Harvested cells were washed in HEPES/PI and frozen at −20°C. After thawing, they were washed twice with HEPES buffer, resuspended and 50 μg of cell membranes was incubated in 0.5 ml HEPES buffer containing [3H]granisetron (81 Ci mmol−1, Dupont) ranging in concentration from 0.05 to 6 nM. d-Tubocurarine (1 μM) was used to determine nonspecific binding. Reactions were incubated for 1 h at 4°C and were terminated by rapid vacuum filtration using a Brandel cell harvester onto GF/B filters presoaked for 3 h in 0.3% polyethyleneimine (PEI) followed by two rapid washes with 4 ml ice cold HEPES buffer. Radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting (Beckman LS6000sc). Protein concentration was estimated using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay with BSA standards. Data were analysed by iterative curve fitting (GraphPad, PRISM, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) according to the equation B=(Bmax[L]n)/([L]n+Kn), where B is the bound radioligand, Bmax is the maximum binding at equilibrium, K is the equilibrium dissociation constant, [L] is the free concentration of radioligand and n is the Hill coefficient.

Ca2+ imaging

This was as described previously with minor modifications (Hargreaves et al., 1994). Briefly, HEK/5-HT3A cells grown on coverslips were washed once with HEPES-buffered medium (HBM: 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES, 15 mM glucose, pH 7.4) and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in HBM containing 2 μM fura-2/acetoxymethyl ester and 1 mg ml−1 BSA. After washing (2 × 1 ml HBM) and at least 30 min further incubation, the cells were washed (2 × 1 ml) in Na+-free HBM where Na+ was replaced by N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), and coverslips were placed in a perfusion chamber on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope. The equipment used was similar to that described previously (Hargreaves et al., 1994). In brief, cells on a round glass coverslip were mounted in a chamber on the stage of an inverted epifluorescence microscope. Excitation light from a 100 W xenon lamp passed through a rapidly rotatable housing holding narrow band interference filters (340 and 380 nm). Emitted light was captured by an ISIS-M CCD camera (Photonic Science, Robertsbridge, U.K.) after passage through a dichroic mirror (400 nm) and high-pass barrier filter (480 nm). Agonists were introduced directly into the chamber (exchange time <5 s) in Na+-free HBM until maximal responses were reached or for 30 s (whichever was longer). The 340/380 nm image pairs were collected at 5 s intervals using Metafluor software (Universal Imaging Corp., PA, U.S.A.), and fluorescence ratios were formed by dividing pairs of images; these were converted to [Ca2+]i by reference to a look-up table created using standard solution (Molecular Probes). The traces shown were produced by calculating the average [Ca2+] within the perimeter of individual cells. Concentration–response curves and parameters were obtained using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Immunofluorescent localization

This was as described previously with minor modifications (Spier et al., 1999). Briefly, transfected cells were washed with three changes of Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 0.1 M Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl) and fixed using ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB: 66 mM Na2HPO4, 38 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.2). To label the N-terminal domain, pAb120 antiserum was used at 1 : 1000 dilution in TBS. Intracellular receptor expression was determined by inclusion of 0.3% Triton X-100 (TTBS) for membrane permeabilization. Primary antibody incubation was overnight at 4°C. Biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) avidin D (Vector) were used to detect bound antibody as per the manufacturer's instructions. Coverslips were mounted in vectashield mounting medium (Vector) and immunofluorescence was observed using a Nikon optiphot or confocal microscope.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were performed as previously described (Gunthorpe & Lummis, 2001), with minor modifications. In brief, whole-cell currents, with cells clamped at −60 mV unless specified otherwise, were recorded either with an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments) controlled by Strathclyde software (Dempster, 1997) or with an EPC9 amplifier (HEKA Electronik) controlled by Pulse software (version 8.3). Intracellular saline (I1) contained 140 mM CsCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1.1 mM EGTA and 10 mM Hepes-CsOH (pH 7.2). Cells were continuously perfused (4–5 ml min−1) with an extracellular solution (E1) containing 120 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 30 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.2). Reversal potential experiments were performed with a pipette solution (I2) consisting of 145 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM EGTA, 10 mM glucose and 10 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.2). Control extracellular saline (E2) comprised 145 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.2); in dilution experiments, 145 mM NaCl was replaced with 72.5 mM NaCl (50% dilution; E3) or 36.25 mM NaCl (25% dilution; E4). Osmolarity was maintained by the addition of D-mannitol where necessary. Agonists were applied with a solution exchange time of <100 ms (Gunthorpe & Lummis, 2000) using either a DAD-12 (ALA Scientific) or a ValveBank 8II (Automate Scientific) at 3-min intervals in order to allow complete recovery from desensitization. Liquid junction potentials were calculated by the method of Barry & Lynch (1991) and potential measurements were corrected post hoc. Current–voltage data were generated by voltage ramps. Cation/anion permeability ratios were determined by fitting shifts in the reversal potential Erev to a modified form of the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz equation: ΔErev=(RT/F)ln{[(aNa)o+(aCl)iPCl/PNa]/[(aNa)i+(aCl)oPCl/PNa]}, where (aNa)o and (aCl)i represent the extracellular and intracellular activities of Na+ and Cl−, respectively.

Results

Characterization of mutant receptors

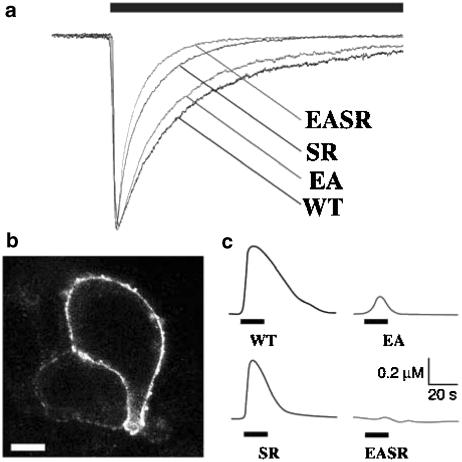

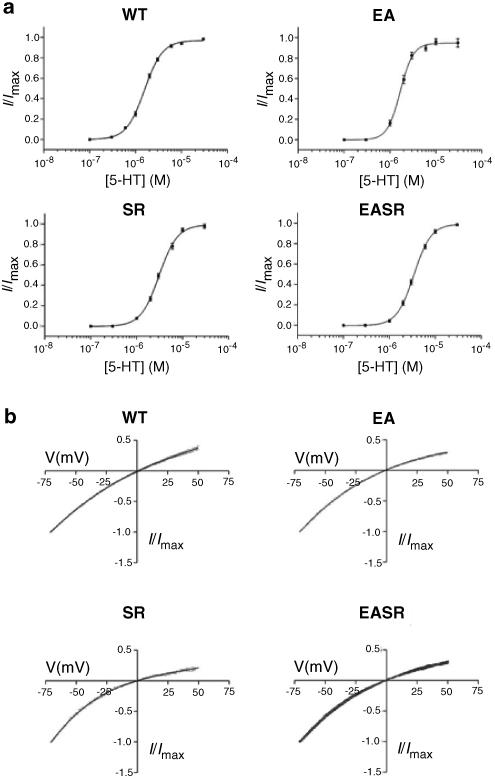

Replacement of glutamate at position −1′ with alanine (E−1′A; designated EA), or serine at position 19′ with arginine, either alone (S19′R; designated SR) or together with the EA mutation (E−1′A, S19′R; designated EASR), generated functional 5-HT-gated receptors (Figure 2a). Concentration–response curves revealed that these mutant receptors had EC50 values for 5-HT and rectification properties similar to those of WT receptors (Figure 3). The mutant receptors also had similar activation kinetics but did exhibit differences in desensitization rates, with time constant (τ) values decreasing in the order WT>EA>SR>EASR (Table 1). Single amino-acid substitutions in M2 have previously been shown to affect the desensitization rate both in the 5-HT3 receptor and in other ligand-gated ion channels (Revah et al., 1991; Yakel et al., 1993; Yakel, 1996; Gunthorpe et al., 2000) and suggest that the conformational changes that occur during channel densensitization are sensitive to small structural changes.

Figure 2.

Expression of WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors. (a) Normalized whole-cell recordings of the responses to 10 μM 5-HT (solid bar, 30 s) in HEK293 cells expressing WT, EA, SR or EASR mutant receptors. (b) Typical immunofluorescence labelling of nonpermeabilised HEK293 cells expressing the AK mutant receptor with an antiserum specific for the N-terminal region of 5-HT3 receptors. Scale bar, 10 μM. (c) Typical maximal increases in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by 10 μM 5-HT (solid bar) in individual HEK293 cells loaded with Fura-2 expressing WT or mutant receptors.

Figure 3.

Properties of WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors. Concentration–response curves (a) and current–voltage plots (b) for WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors. Currents were recorded in symmetrical solutions and normalized curves plotted as mean±s.e.m. The EC50 values for 5-HT derived from the normalized current (I/Imax) curves were 1.56, 1.68, 3.1 and 3.4 μM, and the Hill coefficients were 2.2, 3.1, 3.1 and 2.3, for WT, EA, SR and EASR receptors, respectively (n=50, 6, 9 and 15).

Table 1.

Activation and desensitization kinetic parameters for WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors at 10 μM 5-HT

| Receptor | Activation rise time (ms) | Desensitization τ (ms) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 490±39 | 7580±800 | 38 |

| EA | 596±65 | 4230±287* | 17 |

| SR | 458±37 | 2077±114* | 55 |

| EASR | 539±67 | 950±69* | 37 |

Data are means±s.e.m. for the indicated number (n) of cells.

P<0.05 versus WT (Student's t-test).

The A24′K receptor is nonfunctional

There are two conserved positively charged residues (19′ and 24′) at the extracellular end of M2 in anionic receptors. To explore if 24′ has a similar role to 19′, we also replaced the neutral residue here in the 5-HT3 receptor with a positively charged lysine (creating A24′K; designated AK). When this was expressed, either alone or in combination with EA, SR or both mutations, no functional receptors were detected in any of the (>400) transfected cells examined. Measurement of radioligand binding with the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron, however, revealed high levels of specific binding, with dissociation constants similar to those observed with WT receptors (data not shown). Furthermore, immunocytochemical analysis of the transfected cells confirmed the expression of 5-HT3 receptors at the plasma membrane (Figure 2b). Thus, the mutant receptors appeared to be expressed normally but were nonfunctional. Similar results were previously obtained with nACh receptors containing a substitution at position 20′ (Campos-Caro et al., 1996); these mutant receptors were expressed at a high level but exhibited markedly impaired functional responses. Our data therefore support the conclusion of this previous study that the M2–M3 loop is important in linking the binding of agonist to a functional response, but do not suggest a role of these conserved charged amino-acid residues in ion selectivity.

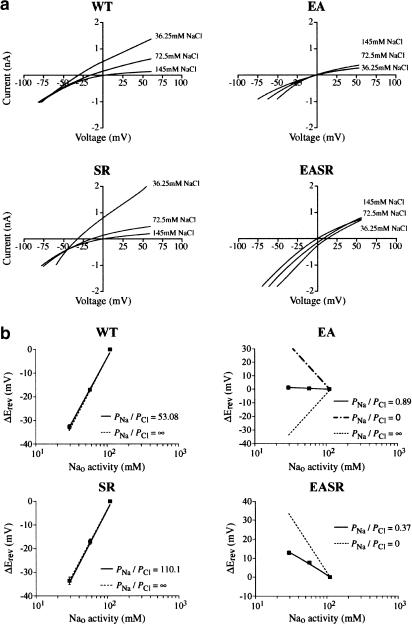

Ion selectivity of mutant receptors

To examine the ion selectivity of the functional mutant receptors, we perfused cells with a saline containing a series of different NaCl concentrations as described in Materials and methods, and then determined reversal potentials from current–voltage plots (Figure 4a). The relative permeabilities of Na+ and Cl− were calculated from current–voltage relations by plotting the change in reversal potential against Na+ activity (Figure 4b). Recombinant WT and SR receptors exhibited PNa/PCl values of 53 and 110 respectively, indicating that they were cation selective. In contrast, the EA receptors manifested almost no ion selectivity (PNa/PCl=0.89). Moreover, Cl− was the predominant charge carrier for EASR receptors (PNa/PCl=0.37); the ion selectivity was thus anionic in the double mutant. We also examined Ca2+ influx through each the mutant receptors. The maximum [Ca2+]i of cells expressing the SRi mutant following activation of 5-HT3 receptors was similar to that of WT receptors; a maximally effective concentration of 5-HT (10 μM) increased the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of cells expressing these two types of receptors to 268±34 nM (n=4) and 370±28 nM (n=5), respectively. In contrast, the maximum [Ca2+]i of cells expressing the EA mutant increased to only 57±9 nM (n=6) upon 5-HT application, and no detectable Ca2+ entry was apparent in cells expressing the EASR double mutant, the AK mutant or mock-transfected HEK cells (n=5–10). Typical Ca2+ traces are shown in Figure 2c. These results are thus consistent with those of the ion selectivity experiments, and also suggest that the differences in desensitization rates between the mutant receptors are not due to differing levels of Ca2+ entry.

Figure 4.

Determination of cation/anion permeability ratios of WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors. (a) Current–voltage curves of WT and mutant receptors in different solutions. (b) Plots of reversal potential versus extracellular Na+ (Nao) activity for determination of relative cation/anion permeability ratios of WT and mutant 5-HT3A receptors. The expected lines for PNa/PCl=0 or ∞ are also shown. Data are means±s.e.m. for n values of 25 (WT), 6 (EA), 9 (SR) and 15 (EASR).

Discussion

The different amino acids that constitute M2 allow activation of different members of the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel family to result in opposite effects in the nervous system: excitation when 5-HT3 and nACh receptors, which are cation selective, are activated, and inhibition when GABAA and glycine receptors, which are selective for anions, are activated (Aidley & Stanfield, 1996). Our data show that ion selectivity can be controlled by the appropriate localization of charged amino acids at one end of M2. Thus replacement of a ring of negatively charged (glutamate) residues with alanine at the intracellular end of M2 in the 5-HT3A receptor subunit resulted in a receptor with no ion selectivity, and if this was combined with substitution of a ring of neutral (serine) residues with positively charged (arginine) residues at the extracellular end of M2, we generated a receptor that was predominantly anion selective. Other properties of these receptors were largely unchanged, suggesting that electrostatic factors alone can control ion selectivity.

The fact that rings of negatively charged amino acid residues play a role in determining conductance and cation selectivity in the nACh receptor is well established (e.g. Imoto et al., 1988; Konno et al., 1991; Galzi et al., 1992; Corringer et al., 1999). The ring at the −1′ position in this protein is formed primarily by glutamate residues and is the ‘intermediate' or ‘intracellular' ring originally identified by Imoto et al. (1988) as having a greater effect on ion selectivity than the ‘extracellular' or ‘cytoplasmic' rings. Its proposed location in the critical narrow region of the pore, which is shown in the model in Figure 5, supports this role. Galzi et al. (1992) showed that it was one of 3 amino acids whose replacement in the M2 region of the nACh receptor with amino acids found in the same locations in anion-selective receptors could convert the channel to anionic. Subsequently, similar studies were performed in glycine (Keramidas et al., 2000) and 5-HT3 (Gunthorpe & Lummis, 2001) receptors and confirmed that changing the equivalent amino acids in these receptors also resulted in a change in ion selectivity. However, all the resulting receptors exhibited additional substantial differences in properties compared with the corresponding WT receptors, including large changes in desensitization, reduced rates of activation and increased agonist affinity compared to WT receptors. These changes may result from substantial structural alterations within the channel; further studies on the nACh receptor (Corringer et al., 1999), which showed that the critical difference between the anionic and cationic versions of mutant α7 nACh receptors was the introduction of a proline residue in the M1–M2 loop (−1′ position), support this hypothesis. Indeed the inserted proline residue can generate functional anionic receptors even when inserted at the −3′ or −1′ positions, although insertion at −4′ resulted in cationic receptors and 0′ in nonfunctional receptors. We suggest, as previously speculated by Galzi et al. (1992), that this structural alteration changes the geometry of M2 such that accessibility of permeant ions to the usual selectivity filters is modified. In the current study, where we have examined the role of the amino acid residues in their natural conformation, the data suggest that charged residues at the −1′ position form the major selectivity filter for cation-selective receptors.

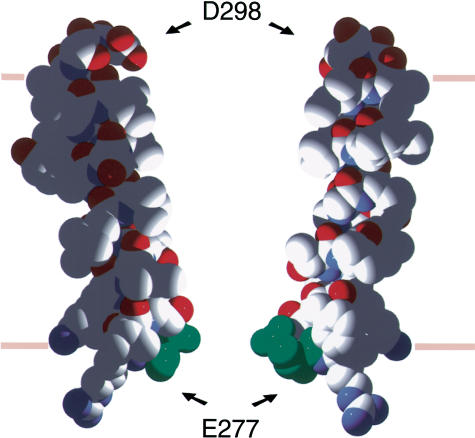

Figure 5.

Model showing the location of E−1′ in M2. The model is based on the Pashkov NMR data for the nACh receptor, with electronic mutations and some rotamer corrections. All atoms are coloured CPK (N=blue, O=red, C=white) except for E−1′, which is green. The likely location of the membrane is indicated by pink bars.

It is interesting that in 5-HT3B receptor subunits, the residue at the −1′ position is alanine and not glutamate as in the A subunits (Figure 1). B subunits only appear to form functional receptors in combination with A; thus it appears that not all −1′ residues must be acidic to create a cation-selective receptor. Similarly, not all nACh receptor subunits have acidic residues at the −1′ position (North, 1995). No functional data have yet been published on the 5-HT3C subunits which, like the B subunits, do not have an acidic residue at the −1′ position. We await this with interest.

The glutamate at −1′ has previously been shown to be important in ion permeability, selectivity and as a cation binding site in the nACh receptor channel (e.g. Imoto et al., 1988; Dani, 1989; Konno et al., 1991; Galzi et al., 1992; Bertrand et al., 1993; Pascual & Karlin, 1998; Corringer et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2000). The data shown here, however, are the first report of the generation of a nonselective channel by its neutralization, which, combined with the data of Keramidas et al. (2002) and Wotring et al. (2003), defines this residue as the single most important contributor to cation selectivity. Interestingly though, while some of the data from the GABAρ receptor are similar to ours, as acidifying the −1′ residue resulted in a nonselective channel (Wotring et al., 2003), acidifying the equivalent residue in the glycine receptor actually reversed the ion selectivity (Keramidas et al., 2002).

Thus in some receptors this residue may be more significant in controlling ion selectivity than in others. Our data show that a ring of charged residues at the 19′ position can also play a role, and indeed acidifying this position in the glycine receptor enhances the cation : anion selectivity. In addition, the size of the pore may be critical – the diameter of the cation-selective glycine receptor has been shown to be larger than that of those that are anion selective.

It is also probable that regions outside the pore-lining domains play a role in ion selectivity. Unwin (2000) has proposed that charged residues located in the inner and outer vestibules of the nACh receptor concentrate the appropriately charged species, as do the acidic amino acids in the K+ channel of Streptomyces lividan (Doyle et al., 1998), and the basic residues in CIC (Dutzler et al., 2002). It is therefore not surprising that the predominantly anionic EASR mutant still has some Na+ permeability (PNa/PCl=0.37), as the receptor is still designed to select for positively charged species at the vestibules close to the pore entrance.

Thus, in conclusion, we have evaluated the role of conserved charged amino-acid residues in the control of ion selectivity in their native orientation in a typical Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel – the 5-HT3 receptor. The data suggest that the electrostatic properties of the channel are of paramount importance, and by changing these we can reverse the selectivity of the channel. These data, combined with those of Keramidas et al. (2002) and Wotring et al. (2003), extend the findings of Imoto et al. (1988) in extrapolating his theory that rings of charged residues control ion selection in the nACh receptor to other cation- and also anion-selective receptors. However, these newer data differ in demonstrating that in both cation- and anion-selective receptors, only a single ring of residues is sufficient to control this selectivity, thus further exemplifying the similarity between different proteins in this receptor family.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Wellcome Trust. SCRL is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Basic Biomedical Science.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- nACh receptor

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- WT

wild type

References

- AIDLEY D.J., STANFIELD P.R. Ion Channels, Molecules in Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- BARRY P.H., LYNCH J.W. Liquid junction potentials and small cell effects in patch-clamp analysis. J. Membr. Biol. 1991;121:101–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01870526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTRAND D., GALZI J.-L., DEVILLERS-THIÉRY A., BERTRAND S., CHANGEUX J.-P. Mutations at two distinct sites within the channel domain M2 alter calcium permeability of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREJC K., VAN DIJK W.J., KLAASSEN R.V., SCHUURMANS M., VAN DER OOST J., SMIT A.B., SIXMA T.K. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS-CARO A., SALA S., BALLESTA J.J., VICENTE-AGULLO F., CRIADO M., SALA F. A single residue in the M2–M3 loop is a major determinant of coupling between binding and gating in neuronal nicotinic receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:6118–6123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN B.N., LABARCA C., CZYZYK L., DAVIDSON N., LESTER H.A. Tris+/Na+ permeability ratios of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are reduced by mutations near the intracellular end of the M2 region. J. Gen. Phys. 1992;99:545–572. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRINGER P.J., BERTRAND S., GALZI J.L., DEVILLERS-THIERY A., CHANGEUX J.P., BERTRAND D. Mutational analysis of the charge selectivity filter of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1999;22:831–843. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANI J.A. Open channel structure and ion binding sites of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:884–892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-03-00884.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMPSTER J.A new version of the Strathclyde Electrophysiology software package running within the Microsoft windows environment J. Physiol. 1997504.P, 57P

- DERKACH V., SURPRENANT A., NORTH R.A. 5-HT3 receptors are membrane ion channels. Nature. 1989;339:706–709. doi: 10.1038/339706a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOYLE D.A., MORAIS CABRAL J., PFUETZNER R.A., KUO A., GULBIS J.M., COHEN S.L., CHAIT B.T., MACKINNON R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUTZLER R., CAMPBELL E.B., CADENE M., CHAIT B.T., MACKINNON R. X-ray structure of a CIC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALZI J.L., DEVILLERS-THIERY A., HUSSY N., BERTRAND S., CHANGEUX J.P., BERTRAND D. Mutations in the channel domain of a neuronal nicotinic receptor convert ion selectivity from cationic to anionic. Nature. 1992;359:500–505. doi: 10.1038/359500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNTHORPE M.J., PETERS J.A., GILL C.H., LAMBERT J.J., LUMMIS S.C. The 4′lysine in the putative channel lining domain affects desensitization but not the single-channel conductance of recombinant homomeric 5-HT3A receptors. J. Physiol. 2000;522:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNTHORPE M.J., LUMMIS S.C.R. Conversion of the ion selectivity of the 5-HT3A receptor from cationic to anionic reveals a conserved feature of the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;276:10977–10983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARGREAVES A.C., LUMMIS S.C.R., TAYLOR C.W. Ca2+ permeability of cloned and native 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;46:1120–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMOTO K., BUSCH C., SAKMANN B., MISHINA M., KONNO T., NAKAI J., BUJO H., MORI Y., FUKUDA K., NUMA S. Rings of negatively charged amino acids determine the acetylcholine receptor channel conductance. Nature. 1988;335:645–648. doi: 10.1038/335645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERAMIDAS A., MOORHOUSE A.J., FRENCH C.R., SCHOFIELD P.R., BARRY P.H. M2 pore mutations convert the glycine receptor channel from being anion- to cation-selective. Biophys. J. 2000;79:247–259. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERAMIDAS A., MOORHOUSE A.J., PIERCE K.D., SCHOFIELD P.R., BARRY P.H. Cation-selective mutations in the M2 domain of the inhibitory glycine receptor channel reveal determinants of ion-charge selectivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;119:393–410. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONNO T., BUSCH C., VON KITZING E., IMOTO K., WANG F., NAKAI J., MISHINA M., NUMA S., SAKMANN B. Rings of anionic amino acids as structural determinants of ion selectivity in the acetylcholine receptor channel. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1991;244:69–79. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNKEL A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LABARCA C., NOWAK M.W., ZHANG H., TANG L., DESHPANDE P., LESTER H.A. Channel gating governed symmetrically by conserved leucine residues in the M2 domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 1995;376:514–516. doi: 10.1038/376514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUMMIS S.C.R., SEPÚLVEDA M.I., KILPATRICK G.J., BAKER J. Characterization of [3H]meta-chlorophenylbiguanide binding to 5-HT3 receptors in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;243:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90160-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORTH R.A. Handbook of Receptors and Channels: Ligand- and Voltage-gated Ion Channels 1995Boca Raton: CRC Press; Chaps 4,5,7 and 8 [Google Scholar]

- PANICKER S., CRUZ H., ARRABIT C., SLESINGER P.A. Evidence for a centrally located gate in the pore of a serotonin-gated ion channel. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1629–1639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASCUAL J.M., KARLIN A. State-dependent accessibility and electrostatic potential in the channel of the acetylcholine receptor. Inferences from rates of reaction of thiosulfonates with substituted cysteines in M2 segment of the alpha subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 1998;111:717–739. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REVAH F., BERTRAND D., GALZI J.L., DEVILLERS-THIERY A., MULLE C., HUSSY N., BERTRAND S., BALLIVET M., CHANGEUX J.P. Mutations in the channel domain alter desensitization of a neuronal nicotinic receptor. Nature. 1991;353:846–849. doi: 10.1038/353846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REEVES D.C., GOREN E., AKABAS M.H., LUMMIS S.C.R. Structural and electrostatic properties of the 5-HT3 receptor pore revealed by substituted cysteine accessibility mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42035–42042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REEVES D.C., LUMMIS S.C.R. The molecular basis of the structure and function of the 5-HT3 receptor: a model ligand-gated ion channel (Review) Mol. Membr. Biol. 2002;19:11–26. doi: 10.1080/09687680110110048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPIER A.D., WOTHERSPOON G., NAYAK S.V., NICHOLS R.A., PRIESTLEY J.V., LUMMIS S.C.R. Antibodies against the extracellular domain of the 5-HT3 receptor label both native and recombinant receptors. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;67:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNWIN N. The Croonian Lecture 2000. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the structural basis of fast synaptic transmission. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2000;355:1813–1829. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON G.G., PASCUAL J.M., BROOIJMANS N., MURRAY D., KARLIN A. The intrinsic electrostatic potential and the intermediate ring of charge in the acetylcholine receptor channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000;115:93–106. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOTRING V.E., MILLER T.S., WEISS D.S. Mutations at the GABA receptor selectivity filter: a possible role for effective charges. J. Physiol. 2003;548:527–540. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAKEL J.L. Desensitization of 5-HT3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes: dependence on voltage and primary structure. Behav. Brain Res. 1996;73:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAKEL J.L., LAGRUTTA A., ADELMAN J.P., NORTH R.A. Single amino acid substitution affects desensitization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:5030–5033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]