Abstract

Nerve growth factor (NGF) and other members of the neurotrophin family are critical for the survival and differentiation of neurons within the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Neurophilin ligands, including FK506, potentiate NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in several experimental models, although the mechanism of this potentiation is unclear.

Therefore, we tested which signaling pathways were involved in FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells using specific pharmacological inhibitors of various signaling molecules.

Inhibitors of Ras (lovastatin), Raf (GW5074), or MAP kinase (PD98059 and U0126) blocked FK506 activity, as did inhibitors of phospholipase C (U73122) and phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (LY294002).

Protein kinase C inhibitors (Go6983 and Ro31-8220) slightly but significantly inhibited neurite outgrowth, whereas inhibitors of p38 MAPK (SB203580) or c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SP600125) had no effect.

These data suggest that FK506 potentiates neurite outgrowth through the Ras/Raf/MAP kinase signaling pathway downstream of phospholipase C and phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase.

Keywords: Neurophilin, FK506, NGF, neurite outgrowth

Introduction

Tacrolimus (FK506) is a potent immunosuppressive drug used after organ transplantation. FK506 activity is mediated by binding to members of the immunophilin family of proteins, designated FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs). In addition to its function in the immune system, FK506 also has neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects, including stimulation of axonal regrowth and enhancement of functional recovery following peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury (for a review, see Gold, 2000).

Nerve growth factor (NGF) and other members of the neurotrophin family are critical for the survival and differentiation of neurons within the peripheral and central nervous systems. Several signal transduction molecules have been implicated in mediating NGF-induced differentiation and survival, including the Ras/Raf/MAP kinase pathway, phospholipase C (PLC), protein kinase A (PKA), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and protein kinase C (PKC; for a review see Huang & Reichardt, 2001). FK506 potentiates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, providing a convenient model system for understanding the signaling interactions of FK506 and NGF. The proposed mechanism of this potentiation involves the interaction of FK506 with FKBP52 and components of the mature steroid receptor complex (Gold et al., 1999a). Although that study proposed that MAP kinase was involved in FK506-mediated neurite potentiation, the molecules in the NGF signaling pathway that mediate interaction with this steroid receptor complex are not entirely clear. To clarify these sites of interaction, we used specific inhibitors of molecules in the NGF signaling pathway to further delineate the signal transduction pathways responsible for the neurite potentiation properties of FK506.

Methods

Preparation of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell cultures

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were plated onto six-well plates at 6 × 104 cells per well and treated with 0.4 μM aphidicolin for 5 days. Cells were then treated with NGF (10 ng ml−1) alone or with FK506. Pharmacological inhibitors (Table 1 ) were added 48 h later. Neurite length was measured 48 h later (i.e., 96 h after initial treatment with NGF). Duplicate wells were run in all experiments, and the entire experiment was repeated at least three times.

Table 1.

Effect of pharmacological inhibitors on neurite outgrowth

| Neurite length (μm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor treatment | Target | Concentration | Inhibitor alone | Inhibitor+NGF |

| Exp 1 | ||||

| None | 115.2±5.4 | 233.3±5.9 | ||

| LY294002 | PI3K | 1 μM | 117.7±5.2 | 234.8±7.5 |

| 5 μM | 109.2±3.3 | 252.6±8.5 | ||

| PD98059 | ERK | 10 μM | 116.7±4.0 | 230.7±7.2 |

| U0126 | ERK | 10 μM | 97.5a±3.0 | 198.2b±10.1 |

| SB203580 | p38 | 10 μM | 124.2±4.3 | 232.2±7.1 |

| MAPK | ||||

| Exp 2 | ||||

| None | 105.0±3.3 | 202.1±6.8 | ||

| Lovastatin | Ras | 5 μg ml−1 | 115.5±2.7 | 171.2±5.3 |

| GW5074 | Raf | 1 μM | 110.5±3.3 | 202.5±8.6 |

| U73343 | PLC- | 1 μM | 108.2±2.9 | 193.0±6.9 |

| U73122 | PLC | 1 μM | 106.1±2.3 | 180.1±5.7 |

| Ro 31-8220 | PKC | 1 μM | 109.4±3.1 | 199.0±6.6 |

| Go6983 | PKC | 1 μM | 103.8±2.5 | 183.1±9.3 |

| SP600125 | JNK | 1 μM | 114.5±3.1 | 200.8±5.8 |

| H-89 | PKA | 5 μM | 118.7±3.5 | 270.6b±8.6 |

| Rp-cAMPs | PKA | 10 μM | 126.3±4.7 | 260.5b±9.7 |

| PD98059 | ERK | 20 μM | ND | 145.4b±5.4 |

| U0126 | ERK | 20 μM | ND | 112.8b±3.8 |

Significantly different than no inhibitor treatment (P<0.05). Significantly different than NGF alone.

(P<0.05). ND, not determined.

Data represent length of the longest neurite on SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells treated with or without NGF for 96 h, with inhibitor treatments during the last 48 h (N=3).

Analysis of neurite length in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells develop axonal-like processes upon treatment with NGF. For analysis of process length, cells (at least 20 per well) were photographed at 96 h. Neurite length was measured using WinRoof software (Mitani Corporation, Fukui, Japan) running on an IBM XT computer; only processes more than twice the cell body length and only one process per cell were measured. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons post-test; P<0.05 was considered significant.

Drugs and chemicals

FK506 was synthesized at Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). DMEM was purchased from GIBCO. NGF was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, U.S.A.). H-89 and aphidicolin were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Lovastatin was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.). U0126, LY294002, and PD98059 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). All other inhibitors were purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.).

Results

FK506 potentiates neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells

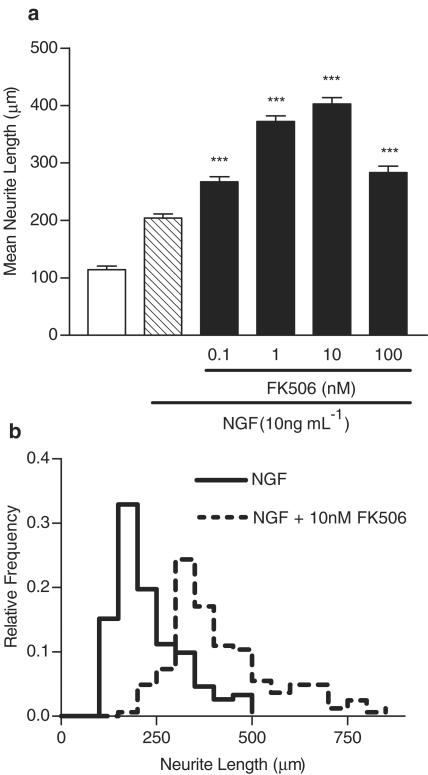

We first wanted to clarify the dose–response relationship of FK506 for potentiating NGF-induced neurite elongation in SH-SY5Y cells (Gold et al., 1997; 1999a). FK506 (0.1–100 nM) significantly increased NGF-induced neurite elongation with a bell-shaped dose–response relationship, with maximum efficacy at 10 nM (Figure 1a). FK506 and NGF cotreatment dramatically shifted the distribution of neurite lengths to the right compared with NGF alone, indicating growth of longer neurites (Figure 1b). FK506 had no effect on neurite outgrowth alone (data not shown). We chose to a submaximal and maximally effective dose (1 and 10 nM FK506) in subsequent inhibitor experiments.

Figure 1.

FK506 potentiates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. (a) FK506 potentiates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. Neurite length was measured 96 h after treatment was initiated. Data are mean± s.e.m. values of at least three independent experiments. **P< 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NGF by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test. (b) Relative frequency histogram comparing the distribution of individual neurite lengths following NGF treatment alone or with 10 nM FK506.

The Raf/Ras/MAPK pathway is involved in FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth

We next wanted to determine the role of MEK/Erk kinases in mediating FK506 activity. We exposed aphidicolin-predifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells to the MEK 1/2 inhibitors PD98059 and U0126, which specifically block MEK activation (Alessi et al., 1995; Favata et al., 1998), in the presence of NGF with or without FK506. Both inhibitors significantly blocked FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth (at 10 μM) with minimal effect on neurite length following NGF treatment alone (Figure 2a, Table 1). However, higher concentrations of these inhibitors (20 μM) inhibited NGF-induced neurite outgrowth, confirming the importance of MEK 1/2 in NGF-induced neuritogenesis (Table 1).

Figure 2.

FK506 potentiates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth via the Ras/Raf/MAP kinase pathway and involves PLC and PI3K signaling. (a) Inhibitors of Raf (lovastatin, 5 μg ml−1) or Ras (GW5074, 1 μM) block the neurotrophic activity of FK506. (b) The MEK 1/2 inhibitors, U0126 (10 μM) or PD98059 (PD; 10 μM), block the neurotrophic activity of FK506. (c) The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY1, 1 μM; LY5, 5 μM), but not the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (SB) (10 μM), blocks FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth. (d) The PLC inhibitor U73122 (U2; 1 μM), but not the inactive analogue U73343 (U3), blocks FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth. (e) Inhibitors of PKC, Go6983 (Go; 1 μM) and Ro31-8220 (Ro; 1 μM), modestly inhibit FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth, whereas the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP; 1 μM) has no effect. (f) Inhibitors of PKA, H-89 (5 μM) and RpcAMPs (RpC; 10 μM), do not block FK506 activity. Neurite length was measured 96 h after NGF treatment was initiated, with inhibitors present during the final 48 h. Data are mean± s.e.m. values of at least three independent experiments. *, **, ***, P<0.05, 0.01, or 0.001 vs NGF + FK506 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test.

A number of signal transduction pathways converge on MEK/ERK. Therefore, to determine whether FK506 interacted with the NGF signaling pathway upstream of MEK, we tested the involvement of the upstream signaling kinases Ras and Raf by using specific inhibitors for these kinases (GW5074 (1 μM) for Raf (Lackey et al., 2000); lovastatin (5 μg ml−1) which inhibits Ras isoprenylation). Both inhibitors blocked the neurotrophic activity of FK506 (Figure 2b), without inhibiting NGF-induced neurite outgrowth (Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway is necessary for FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth.

Signaling molecules proximal to trkA are involved in FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth

In addition to the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway, other signaling molecules are also activated upon addition of NGF, including PLC, PKC, PKA, and JNK (Sofroniew et al., 2001). Using the same pharmacological inhibitor strategy, we tested whether these molecules were involved in the mechanism of action of FK506. The PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, but not the p38 MAP Kinase inhibitor, SB203580, blocked FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth (Figure 2c). The PLC inhibitor, U73122, effectively blocked FK506 activity, whereas the inactive analog, U73343, had no effect (Figure 2d). Two inhibitors of PKC, Ro 31-8220 and Go6983, slightly but significantly inhibited FK506 activity, whereas the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, had no effect (Figure 2e). Two inhibitors of PKA, H-89 and Rp-cAMPS did not affect FK506 activity (Figure 2f).

Discussion

Although FK506 possesses neurotrophic activity in a number of in vitro and in vivo models (Gold, 2000; Guo et al., 2001b), the mechanism by which FK506 mediates these effects is not entirely clear. Neither calcineurin inhibition nor binding to FKBP-12 are necessary for the neurotrophic effects of neurophilins (Gold et al., 1997; 1999a; Steiner et al., 1997; Costantini et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2001a; Klettner et al., 2001; Tanaka et al., 2002). Furthermore, the NGF-potentiating activity of FK506 can be disrupted by an anti-FKBP52 blocking antibody, as well as disrupters of both the mature steroid receptor complex and heat shock proteins, suggesting that these proteins play a role in the neurotrophic activity of FK506 (Gold et al., 1999a; Klettner & Herdegen, 2003). However, the molecules that serve as convergence points between the steroid receptor complex/FKBP52 and the NGF signaling pathway are unknown. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to elucidate the mechanism by which FK506 potentiates NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells by using specific pharmacological inhibitors of signaling molecules downstream of NGF stimulation. Our results demonstrate that FK506 enhances NGF-induced neurite elongation in a bell-shaped manner, consistent with previous reports (Gold et al., 1999a). Importantly, FK506 alone does not change neurite length, suggesting that it functions through enhancing NGF signaling. Furthermore, at the concentrations tested with FK506, these inhibitors did not inhibit neurite outgrowth after NGF treatment (Table 1), demonstrating the specificity of these signaling molecules in mediating the activity of FK506. The critical role of these signaling molecules precludes complete inhibition under chronic conditions. Thus, while some inhibitor concentrations used are lower than those necessary for acute biochemical effects, these concentrations reflect the highest noncytotoxic dose in our chronic treatment conditions (data not shown). Furthermore, the fact that most inhibitors had functional consequences suggests that, even though inhibition might not have been complete, their target molecules play a role in FK506 activity.

NGF binds to the high-affinity protein tyrosine kinase receptor, TrkA, initiating several signaling pathways affecting both morphological and transcriptional targets (Huang & Reichardt, 2001). Here we show for the first time that the Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk pathway is critical for FK506-mediated potentiation of NGF activity. The role of PLC-γ signaling in mediating the long-term activity of NGF is largely unknown, although it plays a role in NGF-induced gene expression (Choi et al., 2001). Our finding that the PLC inhibitor U73122, but not its inactive analog U73343, inhibited FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth suggests a role for PLC in differentiation downstream of FK506 activity. NGF/TrkA stimulation of PI3 K is involved in neurite outgrowth and differentiative signaling, and may either complement or parallel the Ras–Raf-MEK-Erk 1/2 cascade. For example, NGF-induced JNK activation is impaired by two PI3 K inhibitors, wortmannin and LY294002, and overexpression of PI3K results in both neurite outgrowth and JNK activation in the absence of Erk activation (Kobayashi et al., 1997). Our results demonstrate that the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 dose-dependently inhibited FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth, suggesting that this protein is also important in the mechanism of FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth. The apparently weak inhibitory effect that the PKC inhibitors Go6983 and Ro31-8220 had on FK506 activity is in line with recent evidence that nuclear accumulation of active ERK requires functional PKC and is prevented by addition of the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (Olsson et al., 2000).

Inhibitors of JNK and p38 MAP kinases did not affect FK506 activity, consistent with findings that these kinases are stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines and cellular stress such as UV light and osmotic shock, but are not stimulated by neurotrophins (Mielke & Herdegen, 2000). Similar concentrations of these inhibitors have physiological effects (e.g., 3 μM SP600125 affects cytokine production (Utsugi et al., 2003), and 10 μM SB203580 protects against dopamine-induced cell death (Junn & Mouradian, 2001)), suggesting that appropriate doses were chosen. Using two inhibitors of PKA activity with distinct mechanisms (Rp-cAMPS is a competitive inhibitor of cAMP binding, whereas H-89 is a competitive inhibitor of ATP binding), we show here that PKA activity is not required for FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth. Interestingly, addition of these inhibitors significantly increased neurite length in the presence of NGF (Table 1). Recent studies suggest that cAMP and PKA participate in the regulation of growth factor signaling through a number of different mechanisms (Barbier et al., 1999; Pursiheimo et al., 2002). While we speculate that inhibition of PKA ameliorates PKA-mediated inhibition of Ras/Raf/ERK signaling, resulting in enhanced neurite outgrowth, clearly further studies are needed to clarify this interaction.

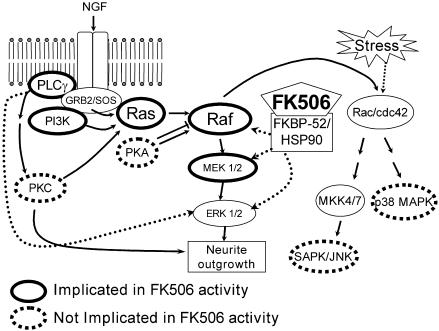

In summary, while these data should be interpreted cautiously because of the indirect nature of inhibitor studies, these data suggest that FK506 enhances neurite outgrowth through the Ras/Raf/MAP kinase signaling pathway downstream of PLC and PI3K (our working hypothesis is presented in Figure 3). Furthermore, these results demonstrate that FK506 enhances NGF signaling via a common growth factor signaling pathway, but has no neurotrophic properties alone, suggesting that nonspecific stimulation of neurotrophin substrates would be reduced in vivo. Recent reports that injured neurons remain responsive to FK506 even after delayed administration (Gold et al., 1999b; Sulaiman et al., 2002), at times when endogenous neurotrophins are elevated (e.g., following spinal cord injury; Murakami et al., 2002), support the hypothesis that FK506 enhances signaling of endogenously produced neurotrophins in vivo, rather than simply acting as a neuroprotective agent. Thus, these studies provide insight into the potential molecular mechanisms by which FK506 promotes nerve regeneration in vivo.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism for FK506-potentiated neurite outgrowth. TrkA activation by NGF leads to activation of multiple signaling pathways, including Ras/Raf/MAPK. FK506 interacts with constituents of the mature steroid receptor complex (HSP90 via FKBP52; Gold et al., 1999a), which putatively enhances the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway. Line patterns indicate results from our experiments. Hashed arrows are putative links; thin arrows indicate pathways established by other studies (Huang & Reichardt, 2001).

Abbreviations

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase-Cγ

References

- ALESSI D.R., CUENDA A., COHEN P., DUDLEY D.T., SALTIEL A.R. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARBIER A.J., POPPLETON H.M., YIGZAW Y., MULLENIX J.B., WIEPZ G.J., BERTICS P.J., PATEL T.B. Transmodulation of epidermal growth factor receptor function by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:14067–14073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI D.Y., TOLEDO-ARAL J.J., SEGAL R., HALEGOUA S. Sustained signaling by phospholipase C-gamma mediates nerve growth factor-triggered gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2695-2705.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTANTINI L.C., COLE D., CHATURVEDI P., ISACSON O. Immunophilin ligands can prevent progressive dopaminergic degeneration in animal models of Parkinson's disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:1085–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAVATA M.F., HORIUCHI K.Y., MANOS E.J., DAULERIO A.J., STRADLEY D.A., FEESER W.S., VAN DYK D.E., PITTS W.J., EARL R.A., HOBBS F., COPELAND R.A., MAGOLDA R.L., SCHERLE P.A., TRZASKOS J.M. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G. Neuroimmunophilin ligands: evaluation of their therapeutic potential for the treatment of neurological disorders. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2000;9:2331–2342. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.10.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G., DENSMORE V., SHOU W., MATZUK M.M., GORDON H.S. Immunophilin FK506-binding protein 52 (not FK506-binding protein 12) mediates the neurotrophic action of FK506. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999a;289:1202–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G., GORDON H.S., WANG M.-S. Efficacy of delayed or discontinuous FK506 administrations on nerve regeneration in the rat sciatic nerve crush model: lack of evidence for a conditioning lesion-like effect. Neurosci. Lett. 1999b;267:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD B.G., ZELENY-POOLEY M., WANG M.S., CHATURVEDI P., ARMISTEAD D.M. A nonimmunosuppressant FKBP-12 ligand increases nerve regeneration. Exp. Neurol. 1997;147:269–278. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO X., DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M. Neuroimmunophilin ligands exert neuroregeneration and neuroprotection in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001a;13:1683–1693. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO X., DILLMAN J.F., III, DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M. Neuroimmunophilins: novel neuroprotective and neuroregenerative targets. Ann. Neurol. 2001b;50:6–16. doi: 10.1002/ana.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG E.J., REICHARDT L.F. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUNN E., MOURADIAN M.M. Apoptotic signaling in dopamine-induced cell death: the role of oxidative stress, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, cytochrome c and caspases. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:374–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLETTNER A., BAUMGRASS R., ZHANG Y., FISCHER G., BURGER E., HERDEGEN T., MIELKE K. The neuroprotective actions of FK506 binding protein ligands: neuronal survival is triggered by de novo RNA synthesis, but is independent of inhibition of JNK and calcineurin. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;97:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLETTNER A., HERDEGEN T. The immunophilin-ligands FK506 and V-10,367 mediate neuroprotection by the heat shock response. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBAYASHI M., NAGATA S., KITA Y., NAKATSU N., IHARA S., KAIBUCHI K., KURODA S., UI M., IBA H., KONISHI H., KIKKAWA U., SAITOH I., FUKUI Y. Expression of a constitutively active phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induces process formation in rat PC12 cells Use of Cre/loxP recombination system. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16089–16092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LACKEY K., CORY M., DAVIS R., FRYE S.V., HARRIS P.A., HUNTER R.N., JUNG D.K., MCDONALD O.B., MCNUTT R.W., PEEL M.R., RUTKOWSKE R.D., VEAL J.M., WOOD E.R. The discovery of potent cRafl kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIELKE K., HERDEGEN T. JNK and p38 stresskinases – degenerative effectors of signal-transduction-cascades in the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000;61:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAKAMI Y., FURUKAWA S., NITTA A., FURUKAWA Y. Accumulation of nerve growth factor protein at both rostral and caudal stumps in the transected rat spinal cord. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002;198:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSSON A.K., VADHAMMAR K., NANBERG E. Activation and protein kinase C-dependent nuclear accumulation of ERK in differentiating human neuroblastoma cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 2000;256:454–467. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PURSIHEIMO J.P., KIEKSI A., JALKANEN M., SALMIVIRTA M. Protein kinase A balances the growth factor-induced Ras/ERK signaling. FEBS Lett. 2002;521:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOFRONIEW M.V., HOWE C.L., MOBLEY W.C. Nerve growth factor signaling, neuroprotection, and neural repair. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:1217–1281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINER J.P., HAMILTON G.S., ROSS D.T., VALENTINE H.L., GUO H., CONNOLLY M.A., LIANG S., RAMSEY C., LI J.H., HUANG W., HOWORTH P., SONI R., FULLER M., SAUER H., NOWOTNIK A.C., SUZDAK P.D. Neurotrophic immunophilin ligands stimulate structural and functional recovery in neurodegenerative animal models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2019–2024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULAIMAN O.A., VODA J., GOLD B.G., GORDON T. FK506 increases peripheral nerve regeneration after chronic axotomy but not after chronic Schwann cell denervation. Exp. Neurol. 2002;175:127–137. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA K., FUJITA N., HIGASHI Y., OGAWA N. Neuroprotective and antioxidant properties of FKBP-binding immunophilin ligands are independent on the FKBP12 pathway in human cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;330:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UTSUGI M., DOBASHI K., ISHIZUKA T., ENDOU K., HAMURO J., MURATA Y., NAKAZAWA T., MORI M. c-Jun N-terminal kinase negatively regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12 production in human macrophages: role of mitogen-activated protein kinase in glutathione redox regulation of IL-12 production. J. Immunol. 2003;171:628–635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]