Abstract

Arvanil (N-arachidonoylvanillamine), a nonpungent capsaicin–anandamide hybrid molecule, has been shown to exert biological activities through VR1/CB1-dependent and -independent pathways. We have found that arvanil induces dose-dependent apoptosis in the lymphoid Jurkat T-cell line, but not in peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Apoptosis was assessed by DNA fragmentation through cell cycle and TUNEL analyses.

Arvanil-induced apoptosis was initiated independently of any specific phase of the cell cycle, and it was inhibited by specific caspase-8 and -3 inhibitors and by the activation of protein kinase C. In addition, kinetic analysis by Western blots and fluorimetry showed that arvanil rapidly activates caspase-8, -7 and -3, and induces PARP cleavage.

The arvanil-mediated apoptotic response was greatly inhibited in the Jurkat-FADDDN cell line, which constitutively expresses a negative dominant form of the adapter molecule Fas-associated death domain (FADD). This cell line does not undergo apoptosis in response to Fas (CD95) stimulation.

Using a cytofluorimetric approach, we have found that arvanil induced the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in both Jurkat-FADD+ and Jurkat-FADDDN cell lines. However, ROS accumulation only plays a residual role in arvanil-induced apoptosis.

These results demonstrate that arvanil-induced apoptosis is essentially mediated through a mechanism that is typical of type II cells, and implicates the death-inducing signalling complex and the activation of caspase-8. This arvanil-apoptotic activity is TRPV1 and CB-independent, and can be of importance for the development of potential anti-inflammatory and antitumoral drugs.

Keywords: Endocannabinoid, arvanil, TPRV1, apoptosis, caspases, fas, ROS

Introduction

The endocannabinoid system has raised a great interest in the last decade, because of the pleiotropic biological effects ascribed to this complex network, which is composed of cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors, metabolism-related enzymes and endogenous signalling molecules (named endocannabinoids) (De Petrocellis et al., 2000; Di Marzo et al., 2000a). Anandamide (N-arachidonoyl ethanolamide) (AEA) was the first endocannabinoid described to date, and its mechanism of action and metabolism regulation have been extensively studied in different biological models (Devane et al., 1992; Di Marzo & Fontana, 1995; Lee et al., 1995; Mechoulam et al., 1996; De Petrocellis et al., 2000). AEA is produced by neurons and other cell types from the hydrolysis of a phospolipid precursor, N-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylethanol-amide, in a reaction catalysed by a Ca2+-dependent phospholipase D (Di Marzo et al., 1994), and acts as a mediator in the brain mainly by signalling through the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. AEA is also an agonist of the vanilloid receptor type 1 (VR1 or TRPV1), a nociceptive receptor expressed preferentially in primary afferent nociceptive neurons (Zygmunt et al., 1999; Smart et al., 2000). TRPV1 is a nonselective cation channel gated by noxious heat, extracellular protons and either exogenous or endogenous ligands (Caterina et al., 1997). Interestingly, the sensitivity of this receptor to heat and ligands is drastically increased under inflammatory conditions, and the activation of TRPV1 by lower concentrations of endogenous agonists during inflammation (including AEA) is seemingly involved in the hyperalgesia accompanying inflammation (Szallasi, 2001; Amaya et al., 2003). Signal termination for AEA includes cellular reuptake by a putative AEA membrane transporter (AMT) and hydrolysis by the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) (Cravatt et al., 1996; Ueda et al., 2000).

Over the past few years, different strategies have been developed to increase the effectiveness and bioavailability of endocannabinoids with pharmacological potential in neurological conditions such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, neuropathic pain and neurological inflammation (Gubellini et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2002). Most of these approaches have been focused on the development of new CB agonists (Di Marzo et al., 2000a), TRPV1 agonists/antagonists (Sterner & Szallasi, 1999; Appendino et al., 2002) and AMT or FAAH inhibitors (Hillard & Jarrahian, 2000; Bisogno et al., 2002), but also the design of new molecules that could retain activities at both CB1 and TRPV1 has been pursued.

N-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxy-benzyl)-arachidonoylamide (arvanil) was designed in an attempt to obtain a hybrid metabolically stable TRPV1/CB1 ligand with a pharmacological profile suitable for the development of ultrapotent analgesics (Di Marzo et al., 2002). Arvanil is a ‘chimeric' ligand that combines the structural features of capsaicin and anandamide, namely the vanillyl moiety of capsaicin and the arachidonoyl group of anandamide. Arvanil has an affinity for CB1 receptors comparable to, or lower than, that of AEA, and also activates TRPV1 more potently than capsaicin or AEA (Melck et al., 1999). Moreover, arvanil is one of the most potent AMT inhibitors developed to date and also inhibits FAAH, the enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of AEA and other endocannabinoids (Glaser et al., 2003). In addition, arvanil has been suggested to induce CB/TRPV1-independent biological effects in vivo (Di Marzo et al., 2000b; Brooks et al., 2002).

Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is a genetically controlled mechanism playing an important role in the regulation of cellular homeostasis. Many triggers can induce apoptosis, including the stimulation of cell membrane-bound receptors (reviewed in Timmer et al., 2002). Among them, CD95 (APO-1, Fas) is an important member of the tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily (reviewed in Wallach et al., 1997) expressed in many different tissues, including T cells, playing a fundamental role in the homeostasis of the immune system (Kroemer & Martinez, 1994). The CD95 signalling pathway has been explored by biochemical and genetic approaches, and it is activated by direct interaction with CD95L (a physiological ligand) or by cytotoxic drugs (Micheau et al., 1999). Upon CD95 stimulation and trimerization, a set of proteins is recruited to this receptor, leading to the formation of the death-inducing signalling complex (DISC) (Kischkel et al., 1995), which contains the intracellular adapter protein FADD that binds to the death domain of the CD95 receptor and to caspase-8, inducing its proteolytic activation. Caspase-8, in turn, activates a proteolytic caspase cascade that transmits and amplifies death signals by the activation of apoptotic executioner caspases such as caspase-3 and -7. These executioner caspases cleavage several substrate proteins including poly(ADP ribose)polymerase (PARP), resulting in the self-destruction of the cells (reviewed in Cryns & Yuan, 1998).

CD95-induced apoptosis is executed by at least two different signalling pathways. In type I cells, large amounts of caspase-8 are recruited to and activated at the DISC, immediately followed by the activation of caspase-3 prior to loss of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential ΔΨm (Scaffidi et al., 1998). In type II cells, the DISC formation is less evident and Bid, a substrate of caspase-8, is cleaved to generate a proapoptotic form, tBid, that targets the mitochondria, allowing the release of cytochrome c, which is an essential cofactor for caspase-3 activation (Li et al., 1998; Budd, 2002). The truncated proapoptotic form of Bid complexes and inhibits Bcl-2 in the outer mitochondria membrane, leading to the release of cytochrome c without a disruption of the ΔΨm (reviewed in Scaffidi et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2000).

Since anandamide and capsaicin have been shown to induce apoptosis in different cell types (Macho et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2000; Maccarrone et al., 2000; Sarker et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2001), we were interested in studying the apoptotic effect of the AEA–capsaicin hybrid arvanil in both peripheral T cells and in a lymphoma T-cell line widely used as a model for T-cell signalling. We present evidence that arvanil induces apoptosis in the Jurkat cell line but not in T resting cells. DNA fragmentation and PARP cleavage in arvanil-treated cells are preceded by the activation of caspase-8, -3 and -7, and are apparently independent of CB and TVRP1 signalling pathways. We also demonstrate that arvanil-induced apoptosis is mediated by a pathway that involves DISC formation.

Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Jurkat cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) were maintained in exponential growth in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine and the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). The Jurkat-FADDDN cell line is a Jurkat-derived clone stably transfected with an expression vector encoding a dominant-negative form of the FADD protein (Hofmann et al., 2001), and was maintained in complete medium containing 100 μg ml−1 of G418. The cell-permeable inhibitors of caspases zDEVD-fmk and zIETD-fmk (N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone and N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone, respectively) were from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). FITC-12-deoxy-2-uridine triphosphate (FITC-dUTP) and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT) were from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). The rabbit polyclonal α-caspase-3 was from Dako Diagnostic (Copenhagen, Denmark), the antisera α-caspase-7, α-caspase-8 and anti-PARP were from Chemicon (Harrow, U.K.), the mAb anti-CD95 was from Pharmingen (San Antonio, CA, U.S.A.) and the mAb anti-tubulin was from Sigma Chemical Co. (Barcelona, Spain). Arvanil was either purchased (Alexis, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) or synthesized according to a recently published procedure for the acylation of vanillamine (Appendino et al., 2002). In short, a cooled (0°C) solution of arachidonic acid (99%, purchased from Alexis) in dry dichloromethane was sequentially treated with vanillamine hydrochloride (1 mol. equiv.), triethylamine (2 mol. equiv.) and propylphophonic acid anhydride (PPAA, 50% solution in ethyl acetate, 2 mol. equiv.). After stirring for 15 min at 0°C, the reaction was worked up by evaporation, and arvanil was purified by a short column of silica gel using petroleum ether-ethyl acetate 9 : 1 as eluant. Typical yields were in the range of 70–79%. Arvanil was dissolved in ethanol and the stock solution was prepared at 10 mM and stored at −20°C. The maximum final concentration of the solvent in the cell cultures was 0.25%, which did not affect any of the parameters analysed in this study. All other reagents not cited above or later were from Sigma Chemical Co.

Isolation of peripheral human T cells

Human PBMC, from healthy adult volunteer donors, were isolated by centrifugation of venous blood on Ficoll-Hypaque® density gradients (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.). Macrophages were removed by incubating the PBMC on 100 mm plastic Petri plates at 37°C for 60 min, and the remaining cells were passed twice through a nylon wool column to deplete residual B cells and macrophages. Nylon wool T cells were usually 95% CD3+ and less than 5% CD25+.

Determination of nuclear DNA loss and cell cycle analysis

The percentage of cells undergoing chromatinolysis (subdiploid cells) was determined by ethanol fixation (70% for 24 h at 4°C). Then, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 4% glucose, and subjected to RNA digestion (RNAse-A, 50 U ml−1) and PI (20 μg ml−1) staining in PBS for 1 h at RT, and analysed by cytofluorimetry. With this method, low molecular weight DNA leaks from the ethanol-fixed apoptotic cells and the subsequent staining allows the determination of the percentage of subdiploid cells (sub-G0/G1 fraction).

Detection of DNA strand breaks by the TUNEL method

Cells (1 × 106) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h at 4°C, washed twice in PBS and permeabilized in 0.1% sodium citrate containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. Fixed cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in a final volume of 50 μl of TUNEL buffer (0.3 nmol FITC-dUTP, 3 nmol dATP, 50 nmol CoCl2, 5 U TdT, 200 mM potassium cacodylate, 250 μg ml−1 BSA and 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.6). The cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed twice in PBS and analysed by flow cytometry. To determine both DNA strand breaks and cell cycle, TUNEL-stained cells were counterstained with PI and treated with RNAse, as described above, prior to cytofluorometric analysis. In this method, fixation in formaldehyde prevents the extraction of low molecular weight DNA from apoptotic cells and thus the cell cycle distribution estimates both apoptotic and nonapoptotic cells.

Determination of caspase-3 and -8 activity

Jurkat cells (3 × 106) were washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min on ice with 100 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4/NaHPO4, pH 7.5, 130 mM NaCl, 1% Triton® X-100 and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate). Cell lysates were spun, the supernatants collected and the protein concentrations determined by the Bradford method. For each reaction, 30 μg of protein from cell lysates was added to 1 ml of freshly prepared protease assay buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT) containing 15 μg of either Ac-DEVD-AMC or Ac-IETD-AMC (Sigma Chemical Co.). Reaction mixtures in the absence of cellular extracts were used as negative controls (fluorescence background). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and the AMC liberated from Ac-peptides-AMC was measured using a spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi F-2500 model, Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) with an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength range of 400–550 nm. Data were collected as the integer of relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) minus the background fluorescence, and represented as RFI-fold induction ±s.d. over untreated control.

Determination of ROS generation

To study the superoxide anion generation (ROS), cells were incubated (106 ml−1) in PBS with dihydroethidine (HE) (red fluorescent after oxidation) (2 μM) (Sigma) for 20 min at 37°C, followed by analysis on an Epics XL Analyzer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL, U.S.A.).

Transient transfections and luciferase assays

Jurkat cells (107 ml−1) were transiently transfected with a construct containing the luciferase gene driven by a 2.3 kb fragment of FasL promoter (pxp2-FasL) that was kindly provided by J.A. Pintor-Toro (CSIC, Sevilla, Spain). The transfections were performed using Lipofectine™ reagent (Invitrogen, Barcelona, Spain), according to the manufacturer's recommendations, for 24 h. Transfected cells were treated as indicated for 6 h. Then, the cells were lysed in 25 mM Tris-phosphate pH 7.8, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100 and 7% glycerol. Luciferase activity was measured using an Autolumat LB 953 (EG&G Berthold, U.S.A.), following the instructions of the luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.), and protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method. The background obtained with the lysis buffer was subtracted in each experimental value and the specific transactivation expressed as a fold induction over untreated cells. Data are represented as mean±s.e. of three independent experiments.

Western blots

Jurkat cells (1 × 106 cells ml−1) were stimulated with different concentrations of arvanil for the indicated period of times. Cells were then washed with PBS and resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 10 mM KCl, 0.15 mM EGTA, 0.15 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaFl, 1 mM DTT, leupeptin 1 μg ml−1, pepstatin 0.5 μg ml−1, apronitin 0.5 μg ml−1 and 1 mM PMSF) containing 0.5% NP-40. After 15 min on ice, cytoplasmic proteins were obtained by centrifugation and protein concentration determined by a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, U.S.A.). The proteins (30 μg) were boiled in Laemmli buffer and electrophoresed in 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.5 A at 100 V; 4°C) for 1 h. The blots were blocked in TBS solution containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat dry milk overnight at 4°C, and immunodetection of specific proteins was carried out with primary antibodies (anticaspase-3, anticaspase-7, anticaspase-7, anti-PARP or anti-α-tubulin), using an ECL system (Amersham, U.K.).

Results

Arvanil induces apoptosis in Jurkat cells but not in primary T cells

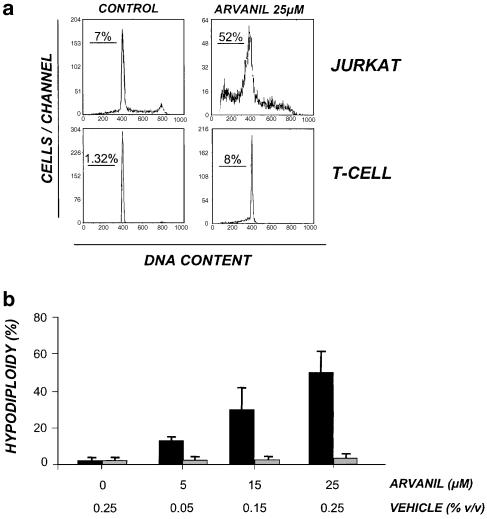

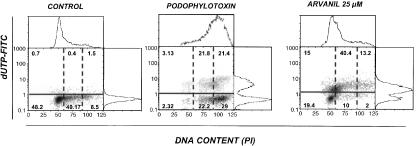

The effect of arvanil on cellular apoptosis was investigated in the leukaemia cell line Jurkat and in human purified primary T cells. The cells were incubated with arvanil (25 μM) for 6 h and the hypodiploidy (i.e., loss of fragmented DNA) was detected by flow cytometry as a marker for apoptosis. In Figure 1a, it is shown that arvanil was able to induce a strong increase in the percentage of hyplodiploid cells. However, when human purified primary T cells were treated with the same concentration of arvanil, we could not detect a significant increase in the percentage of hypodiploidy cells. While ethanol did not affect the cell cycle, arvanil-induced hypodiploidy in Jurkat cells was dose-dependent and it was already detected with the lower concentration tested (Figure 1b). Next, to examine whether arvanil-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells is dependent on a specific phase of the cell cycle, we performed double-staining experiments with PI and FITC-dUTP, as described in Methods. In this way, the phase of the cell cycle during which DNA fragmentation occurs can be established. In Figure 2, it is shown that arvanil-induced DNA fragmentation (68.6% of the cells) appeared to be proportional to the number of cells in each phase of the cell cycle. Thus, in contrast to the results obtained by cell treatment with podophylotoxin, a compound that binds tubulin and arrests cell cycle at the G2/M phase initiating the DNA fragmentation, arvanil-induced apoptosis was independent of any specific phase of the cell cycle. This result could explain the different percentages of apoptotic cells found by using either cell cycle analysis by PI staining (52% in Figure 1a) or the TUNEL method (68% in Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Arvanil induces apoptosis in Jurkat cells but not in primary T cells. (a) Cell cycle analysis. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of arvanil for 6 h and the percentage of hypodiploid cells was detected using flow cytometry. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Jurkat cells (black bars) or human peripheral isolated T cells (grey bars) were treated with arvanil at the indicated doses for 6 h, and the percentage of hypodiploid cells determined by flow cytometry. The percentage of vehicle (v v−1) used in each treatment is indicated. Values are means±s.e. of three different experiments.

Figure 2.

TUNEL analysis of arvanil-induced apoptosis. Jurkat cells were treated either with arvanil 25 μM for 6 h or podophylotoxin 10 μM for 24 h, and the cell cycle and the DNA strand breaks analysed using flow cytometry, as described in Methods. The continuous horizontal line divides the diagram into fragmented DNA cells (upper square) and nonfragmented DNA cells (lower square), and vertical dash lines separate each phase of the cell cycle: Go/G1 (left), S (middle) and G2/M (right). Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each group. Results are representative of three different experiments.

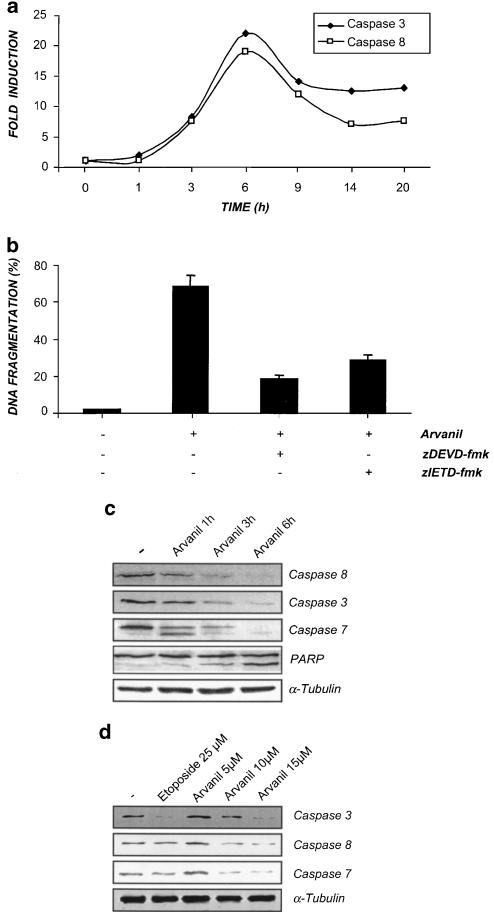

Apoptosis induced by arvanil in Jurkat cells involves the caspase cascade pathway

The caspase family consists of postaspartate-cleaving cysteine proteases that have been shown to be required for apoptosis in a number of experimental systems (reviewed in Thornberry & Lazebnik, 1998). Thus, to study the activation of the executor caspase-3 and the modulator caspase-8 in a direct way, we incubated the cells with arvanil (15 μM) for different periods of time, and the activities of both caspases were determined by a fluorimetric method that is highly specific and sensitive. Figure 3a shows that the treatment of Jurkat cells with arvanil led to the activation of both caspases, with a very similar kinetic showing a maximal activation after 6 h of treatment. Next, to establish the involvement of caspase activation in arvanil-mediated apoptosis of Jurkat cells, we preincubated the cells with either of the tetrapeptide caspase inhibitors zDEVD-fmk or zIETD-fmk before arvanil treatment. zDEVD-fmk and zIETD-fmk are reported to inhibit caspase-3 and -8, respectively. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined 6 h after arvanil treatment by the TUNEL method, and in Figure 3b it is shown that apoptosis induced by arvanil was largely inhibited by both caspase inhibitors. It is noteworthy that zDEVD-fmk was slightly more effective at protecting Jurkat cells from arvanil-induced apoptosis than zIETD-fmk. These results demonstrate a role for caspase-8 in the apoptotic pathway activated by arvanil, and, since this caspase triggers a proteolytic cascade that amplifies death signals by the activation of executioner caspase-3 and -7, we were interested in examining if arvanil could also induce the activation of caspase-7 in Jurkat cells. This caspase was present in control Jurkat cells primarily as a 35 kDa protein (Figure 3c). Treatment with arvanil (15 μM) resulted in a time-dependent processing of caspase-7, accompanied by the formation of one major product of about 32 kDa, which probably represents the loss of the prodomain at DSVD23↓. Processing of caspase-7 was first observed 1 h after arvanil treatment and it was completed at 6 h of treatment. Similar kinetics of activation was found for caspase-3 and -8 in arvanil-treated cells. However, although PARP cleavage was initiated after 1 h treatment, the maximum cleavage was reached after 6 h of treatment with arvanil. In addition, arvanil-induced processing of the three procaspase forms was found to be dose-dependent, being detectable with 10 μM arvanil, a concentration at which apoptosis is already detectable (Figure 3d). Arvanil treatment did not affect the steady-state levels of the housekeeping protein α-tubulin.

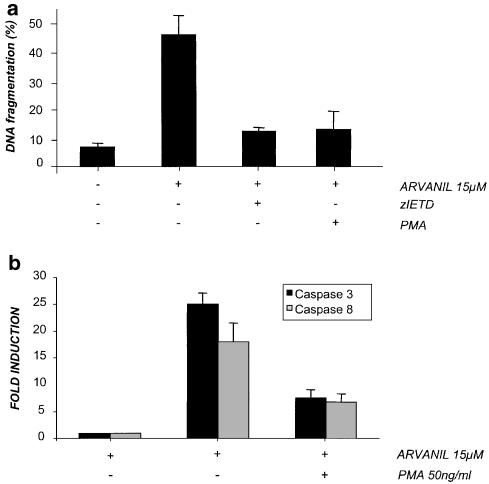

Figure 3.

Involvement of caspase activation in arvanil-induced apoptosis. (a) Caspase activity determination. Jurkat cells were treated with arvanil (15 μM) and the kinetics of caspase-3 and -8 activation detected by fluorimetry. (b) DNA fragmentation analysis in the presence of caspase-3 and -8 inhibitors. Cells were preincubated with 20 μM of the caspase inhibitors zDEVD-fmk (for caspase-3) and zIETD-fmk (for caspase-8), and treated with arvanil 15 μM for 6 h. After this time, DNA fragmentation was detected by the TUNEL method. Values are means±s.e. of three different experiments. (c) Kinetic studies of caspase-8, -3 and -7 activation and PARP cleavage by Western blot. Cells were treated with arvanil 15 μM at the indicated times and the steady-state protein levels of caspase-3, -8, -7, PARP and α-tubulin detected by Western blot. (d) Dose–response effects of arvanil (6 h) on the proteolytic degradation of caspase-3, -8 and -7.

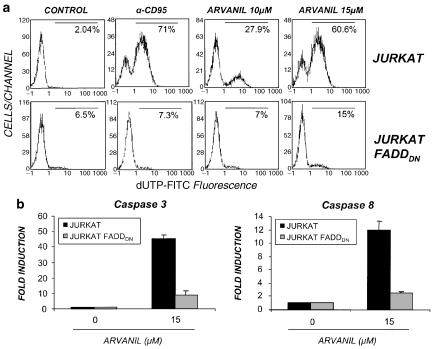

FADD-dependent caspase activation is required for arvanil-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells

It is accepted that Fas (CD95) signaling pathway is mediated by recruitment of FADD and procaspase-8 to the death domain of Fas to form the DISC (Kischkel et al., 1995; reviewed in Timmer et al., 2002). The involvement of further DISC protein for arvanil-induced apoptotic pathway was investigated by analysing CD95 and arvanil-induced apoptosis in a Jurkat line stably expressing a dominant-negative form of the FADD (FADDDN) adapter protein, which lacks the death effector domain (Hofmann et al., 2001). Overexpression of FADDDN prevents DISC formation and activation of caspase-8 triggered by FasL or anti-Fas antibodies (Chinnaiyan et al., 1996). In Figure 4a, it is shown that either anti-CD95 or arvanil induce DNA fragmentation in the parental Jurkat cells; by contrast, in the Jurkat-FADDDN, no apoptosis was found in response to the agonist mAb anti-CD95. Arvanil-induced apoptosis was also largely inhibited in the FADDDN cells although a residual apoptosis was observed with the higher doses of arvanil tested. Activation of caspase-3 and -8 was also impaired in Jurkat-FADDDN when compared with the Jurkat wild type and, again, some degree of caspase activation could be detected in arvanil-treated Jurkat-FADDDN cells (Figure 4b). These results suggest that an additional pathway independent of FADD is also activated by arvanil in Jurkat cells. A number of previous studies have reported that in type II cells PMA treatment inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis (reviewed in Krammer, 2000). In this sense, the inhibitory effect on PMA-induced apoptosis can be mediated by disrupting DISC formation or by activation of the ERK pathway (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 1999; Meng et al., 2002). Thus, to investigate the role of PKC in arvanil-induced apoptosis, Jurkat cells were stimulated with the PKC agonist PMA for 30 min prior to treatment with arvanil. Then, DNA fragmentation was measured, and in Figure 5a it is shown that PMA pretreatment almost abolished the apoptosis induced by arvanil, which also correlated with the ability of PMA to inhibit arvanil-induced activation of caspase-3 and -8 (Figure 5b).

Figure 4.

Arvanil-induced apoptosis is impaired in Jurkat-FADDDN cells. (a) DNA fragmentation. Jurkat and Jurkat FADDDN cells were treated with either anti-CD95 mAb or arvanil (10 and 15 μM) for 6 h, and the percentage of apoptotic cells (DNA fragmentation) was detected by TUNEL staining and flow cytometry (b). Fluorimetric analysis of caspase-3 and -8 activities in Jurkat and Jurkat FADDDN cells treated with arvanil (15 μM) for 6 h. Data are represented as the means of RFI fold induction over untreated control±s.e. of three different experiments.

Figure 5.

PMA inhibits arvanil-induced apoptosis and caspase-3 and -8 activation. (a) Jurkat T cells were preincubated with either zIETD (20 μM) or PMA (20 nM), and treated with arvanil 15 μM for 6 h. The percentage of apoptosis was determined as in Figure 3b. (b) Caspase-3 and -8 activity detection by fluorimetry in cells treated with arvanil in the presence or absence of PMA.

Arvanil does not induce FasL transcriptional activity

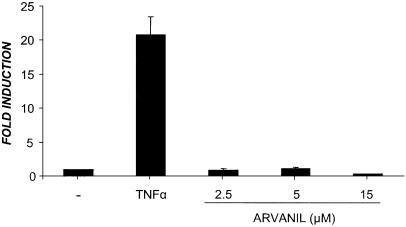

It has been shown that some cytotoxic drugs can induce Fas-mediated apoptosis by upregulation of the FasL gene (Pucci et al., 1999; Mansouri et al., 2003). Since FasL expression is tightly regulated at the transcriptional level, we investigated the regulation of the FasL promoter in Jurkat cells transiently transfected with the promoter reporter plasmid pxp2-FasL-Luc. After transfection, cells were treated either with TNFα or with increasing concentrations of arvanil for 3 h, to ensure that the measurement of luciferase activity is not affected by arvanil-induced DNA fragmentation. In Figure 6, it is shown that the TNFα-responsive FasL promoter was not upregulated by arvanil with any of the concentrations tested. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that although arvanil-induced apoptosis is mainly dependent on FADD, clustering of CD95 by FasL binding is not necessary.

Figure 6.

Arvanil does not affect FasL gene expression. Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with the pxp2-FasL-luc plasmid, as described in Methods. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were treated with either TNFα or with arvanil at the indicated doses for 3 h. Then, the cells were lysed and the luciferase activity measured. Values are means of RLU fold induction±s.e. of three independent experiments.

Arvanil induces sequential ROS generation in Jurkat cells

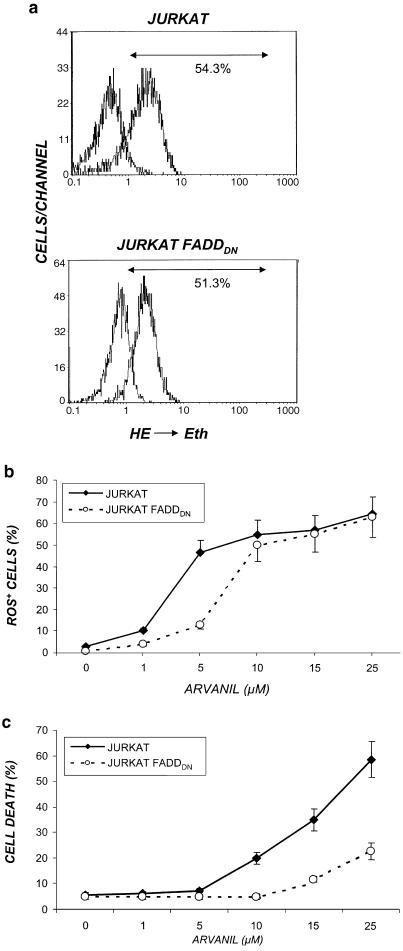

Arvanil is a nonpungent anandamide–capsaicin hybrid that contains the vanilloid ring (Melck et al., 1999). We have previously shown that vanilloid compounds behave as quinone analogues and induce intracellular ROS and apoptosis in Jurkat cells (Macho et al., 1998; 1999; 2000; 2003). Thus, we studied the ability of arvanil to generate ROS using HE (nonfluorescent) that becomes ethidium (Eth, red fluorescent) after its oxidation via ROS (Petit et al., 1990). We treated both Jurkat and Jurkat-FADDDN cells with arvanil (10 μM) for 6 h, and the percentage of cells with high levels of intracellular ROS was analysed by flow cytometry (Figure 7a). We observed that ROS increase in both cell lines treated with this compound was dose-dependent (Figure 7b). Interestingly, when cell death was measured in parallel in arvanil-treated cells, Jurkat-FADDDN cells were clearly more resistant to cell death that the parental clone (Figure 7c). These differences suggest that ROS generation could be implicated in a part of arvanil-induced apoptosis, but not in the whole process, a fact that could explain the residual albeit significant apoptosis observed in arvanil-treated Jurkat-FADDDN cells (Figure 4a).

Figure 7.

Arvanil induces ROS formation in both Jurkat and Jurkat-FADDDN cell lines. (a) Jurkat or Jurkat-FADDDN cells were treated with arvanil 15 μM, and after 6 h they were collected and the percentage of cells with high Eth fluorescence (ROS generation) detected by flow cytofluorimetry (b, c). Dose–response generation of ROS (b) and cell death (c) in arvanil-treated Jurkat and Jurkat-FADDDN cells for 6 h. Values are means±s.e. of three different experiments.

Discussion

It is now widely accepted that in addition to their cannabimimetic effects, AEA and other endocannabinoids have pleiotropic activities (reviewed in Parolaro et al., 2002). Thus, AEA has been implicated in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation (reviewed in Parolaro et al., 2002) and, more recently, cannabinoids have been shown to play an important role in the angiogenic process accompanying tumoral spread and invasion (Blazquez et al., 2003; Casanova et al., 2003), suggesting a possible antitumoral activity for the endocannabinoid system (reviewed in Bifulco & Di Marzo, 2002). Accordingly, there is growing evidence that AEA, and perhaps other arachidonic acid derivatives as well, may exert a control on cellular growth and apoptosis through different signal pathways. In this sense, metabolically stable analogues of AEA like arvanil might be of special interest in studying the mechanistic aspects of the apoptotic properties of endocannabinoids and endovanilloids.

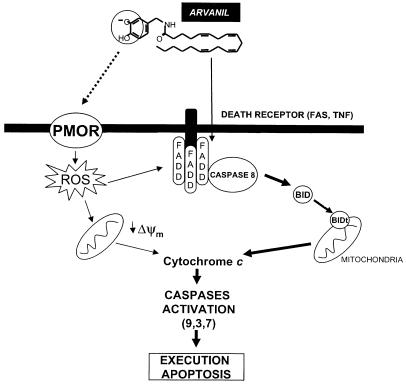

Arvanil is a capsaicin–anandamide hybrid with a very high structural homology to the recently described endovanilloid N-arachidonoyl dopamine (NADA) (Bisogno et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2002). Arvanil and NADA are TRPV1 and CB1 receptor agonists, and lack CB2 agonist activity. Since Jurkat cells do not express neither TRPV1 or CB1 receptors (Sancho et al., 2003), we assumed that arvanil-induced apoptosis is through TRPV1 and CB receptor-independent pathways. Our results strongly suggest that DISC formation and activation of caspase-8 are the initial steps in arvanil-induced apoptosis and, although arvanil did not upregulate FasL, it is likely that arvanil induces Fas clustering and DISC formation, since stably FADDDN-transfected Jurkat cells showed a clear diminished caspase-8 and -3 activation and DNA fragmentation in response to this compound. Moreover, the effects of arvanil on DISC formation were supported by our results showing that PKC activation protects from arvanil-induced apoptosis. It has been demonstrated that in type II (e.g., Jurkat) cells, PKC activation prevents CD95-mediated apoptosis by inhibiting CD95 receptor oligomerization at the cell membrane, thus avoiding DISC formation (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 1999). In addition, PMA activates the ERK pathway that prevents apoptosis and promotes cell survival (Scaffidi et al., 1999). Altogether, our results indicate that arvanil induces an apoptosis that is typical of type II cells by a FasL-independent mechanism (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram highlighting the proposed mechanism for arvanil-induced apoptosis. Arvanil induces FADD clustering, which allows the recruitment of caspase-8. Then, this caspase is cleaved and activated, leading to an apoptotic cascade that includes Bid truncation, leaking of cytochrome c from mitochondria and activation of different effector caspases (-3, -7, -9). To complement this pathway, arvanil induces ROS that may help to DISC formation and may also induce the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c.

Although a high percentage of human primary T cells express CD95, our results show that arvanil does not induce apoptosis in these cells. The arachidonic acid moiety of arvanil may allow the molecule to enter the cells by a process of simple diffusion, as it has been recently suggested for AEA (Glaser et al., 2003). Like other antitumour lipids (Cabaner et al., 1999), the cellular uptake of arvanil could be much larger in tumoral cells that in primary resting T cells. In addition, primary resting T cells could be more resistant to anti-CD95-mediated apoptosis than Fas-expressing cultured cell lines, as previously proposed (Miyawaki et al., 1992). Thus, our results suggest that, in addition to CD95/Fas expression, other cellular factors may be required for arvanil-induced apoptosis.

We and others have demonstrated that the vanilloid moiety of resiniferatoxin, capsaicin and capsiate behaves as a quinone analogue, targeting and inhibiting the plasma membrane redox system (Vaillant et al., 1996; Wolvetang et al., 1996; Macho et al., 1999). As a result of this inhibition, quinone analogues generate an excess of intracellular ROS that contributes to the apoptotic pathway (Hildeman et al., 1999). Here we show that arvanil, which contains a vanilloid moiety, can also behave as a quinone analogue, since it was able to induce high levels of intracellular ROS in either Jurkat or Jurkat FADDDN cell lines. However, the fact that Jurkat FADDDN cells were highly resistant to arvanil-induced apoptosis compared to the wild-type clone suggests that ROS generation could be implicated in arvanil-induced apoptosis by at least two pathways. First, arvanil-induced ROS may activate a sphingomyelinase at the lipid rafts of the cell membrane, increasing the intracellular levels of ceramide (reviewed in Andrieu-Abadie et al., 2001), which has been involved in the apoptotic pathways induced by a wide range of stimuli including Fas (reviewed in Carmody & Cotter, 2001). Then, ceramide could favour DISC assembly triggering the apoptotic cascade. This hypothesis will be in concordance with a recent report showing that Fas-resistant cell lines (like our Jurkat FADDDN cell clone) are also resistant to apoptosis induced by either serum withdrawal or exogenous ceramide (Caricchio et al., 2002). Secondly, ROS may also induce a direct attack to the mitochondria pores, inducing the release of cytochrome c and further activation of executor caspases (Macho et al., 1998). This second pathway could explain the residual albeit significant cell death observed in arvanil-treated Jurkat-FADDDN cells, which was due to apoptosis rather than necrosis.

Anandamide transport inhibitors and FAAH inhibitors are designed to increase AEA concentrations outside the cells, thus enhancing its biological effects. For instance, it has been shown that both AMT and FAAH inhibitors (AM404 and ATFMK, respectively) enhance the apoptotic effects of AEA in human neuroblastoma CHP100 and lymphoma U937 cells (Maccarrone et al., 2000). Recently, it has also been reported that arvanil inhibits AEA transport into cells by targeting FAAH (Glaser et al., 2003), and, although Jurkat cells express FAAH (Sancho et al., 2003), we found that its pharmacological inhibition with arachidonoyl trifluoromethyl ketone (ATMFK) did not induce apoptosis in this particular cell line (data not shown), ruling out the possible involvement of this enzyme in arvanil-induced apoptosis.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that arvanil induces apoptosis in lymphoid cells through a FADD-mediated mechanism that involves the activation of caspase-8, -3 and -7. This activity might underlie some of the known anti-inflammatory and proapoptotic effects of endocannabinoids/endovanilloids, and provides a rationale for the synthesis of new analogues endowed with selective anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants BIO 2000-1091-C01 (MCyT) and QLK3-CT2000-00463 (UE) to E.M., and by the MCyT grant SAF2002-01157 to A.M. We thank Dr Lienhard Schmitz (University of Bern, Switzerland) for providing the stably transfected Jurkat-FADDDN cell line.

Abbreviations

- AEA

arachidonoyl ethanolamide

- CB

cannabinoid receptor

- DISC

death-inducing signalling complex

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- FADD

Fas-associated death domain

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TRPV1

vanilloid receptor type 1

- TUNEL

terminal transferase-mediated dUTP-fluorescein nick end-labelling

- ΔΨm

mitochondria transmembrane potential

References

- AMAYA F., OH-HASHI K., NARUSE Y., IIJIMA N., UEDA M., SHIMOSATO G., TOMINAGA M., TANAKA Y., TANAKA M. Local inflammation increases vanilloid receptor 1 expression within distinct subgroups of DRG neurons. Brain Res. 2003;963:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRIEU-ABADIE N., GOUAZE V., SALVAYRE R., LEVADE T. Ceramide in apoptosis signaling: relationship with oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPENDINO G., MINASSI A., MORELLO A.S., DE PETROCELLIS L., DI MARZO V. N-Acylvanillamides: development of an expeditious synthesis and discovery of new acyl templates for powerful activation of the vanilloid receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:3739–3745. doi: 10.1021/jm020844o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIFULCO M., DI MARZO V. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in cancer therapy: a call for further research. Nat. Med. 2002;8:547–550. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISOGNO T., DE PETROCELLIS L., DI MARZO V. Fatty acid amide hydrolase, an enzyme with many bioactive substrates. Possible therapeutic implications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2002;8:533–547. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISOGNO T., MELCK D., BOBROV M., GRETSKAYA N.M., BEZUGLOV V.V., DE PETROCELLIS L., DI MARZO V.N-acyl-dopamines: novel synthetic CB(1) cannabinoid-receptor ligands and inhibitors of anandamide inactivation with cannabimimetic activity in vitro and in vivo Biochem. J. 2000351817–824.(Part 3) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLAZQUEZ C., CASANOVA M.L., PLANAS A., DEL PULGAR T.G., VILLANUEVA C., FERNANDEZ-ACENERO M.J., ARAGONES J., HUFFMAN J.W., JORCANO J.L., GUZMAN M. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by cannabinoids. FASEB J. 2003;17:529–531. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0795fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS J.W., PRYCE G., BISOGNO T., JAGGAR S.I., HANKEY D.J., BROWN P., BRIDGES D., LEDENT C., BIFULCO M., RICE A.S., DI MARZO V., BAKER D. Arvanil-induced inhibition of spasticity and persistent pain: evidence for therapeutic sites of action different from the vanilloid VR1 receptor and cannabinoid CB(1)/CB(2) receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;439:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUDD R.C. Death receptors couple to both cell proliferation and apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:437–441. doi: 10.1172/JCI15077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABANER C., GAJATE C., MACHO A., MUNOZ E., MODOLELL M., MOLLINEDO F. Induction of apoptosis in human mitogen-activated peripheral blood T-lymphocytes by the ether phospholipid ET-18-OCH3: involvement of the Fas receptor/ligand system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:813–825. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARICCHIO R., D'ADAMIO L., COHEN P.L. Fas, ceramide and serum withdrawal induce apoptosis via a common pathway in a type II Jurkat cell line. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:574–580. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARMODY R.J., COTTER T.G. Signalling apoptosis: a radical approach. Redox Rep. 2001;6:77–90. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASANOVA M.L., BLAZQUEZ C., MARTINEZ-PALACIO J., VILLANUEVA C., FERNANDEZ-ACENERO M.J., HUFFMAN J.W., JORCANO J.L., GUZMAN M. Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:43–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI16116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATERINA M.J., SCHUMACHER M.A., TOMINAGA M., ROSEN T.A., LEVINE J.D., JULIUS D. The capsaicin receptor – a heat-activated ion-channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHINNAIYAN A.M., TEPPER C.G., SELDIN M.F., O'ROURKE K., KISCHKEL F.C., HELLBARDT S., KRAMMER P.H., PETER M.E., DIXIT V.M. FADD/MORT1 is a common mediator of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4961–4965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAVATT B.F., GIANG D.K., MAYFIELD S.P., BOGER D.L., LERNER R.A., GILULA N.B. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRYNS V., YUAN J. Proteases to die for. Genes. Dev. 1998;12:1551–1570. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE PETROCELLIS L., MELCK D., BISOGNO T., DI MARZO V. Endocannabinoids and fatty acid amides in cancer, inflammation and related disorders. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000;108:191–209. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVANE W.A., HANUS L., BREUER A., PERTWEE R.G., STEVENSON L.A., GRIFFIN G., GIBSON D., MANDELBAUM A., ETINGER A., MECHOULAM R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI MARZO V., BISOGNO T., DE PETROCELLIS L. Endocannabinoids: new targets for drug development. 2000a;6:1361–1380. doi: 10.2174/1381612003399365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI MARZO V., BREIVOGEL C., BISOGNO T., MELCK D., PATRICK G., TAO Q., SZALLASI A., RAZDAN R.K., MARTIN B.R. Neurobehavioral activity in mice of N-vanillyl-arachidonyl-amide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000b;406:363–374. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI MARZO V., FONTANA A. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabinomimetic eicosanoid: ‘killing two birds with one stone'. Prostagland. Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1995;53:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI MARZO V., FONTANA A., CADAS H., SCHINELLI S., CIMINO G., SCHWARTZ J.C., PIOMELLI D. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372:686–691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI MARZO V., GRIFFIN G., DE PETROCELLIS L., BRANDI I., BISOGNO T., WILLIAMS W., GRIER M.C., KULASEGRAM S., MAHADEVAN A., RAZDAN R.K., MARTIN B.R. A structure/activity relationship study on arvanil, an endocannabinoid and vanilloid hybrid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;300:984–991. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASER S.T., ABUMRAD N.A., FATADE F., KACZOCHA M., STUDHOLME K.M., DEUTSCH D.G. Evidence against the presence of an anandamide transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730816100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUBELLINI P., PICCONI B., BARI M., BATTISTA N., CALABRESI P., CENTONZE D., BERNARDI G., FINAZZI-AGRO A., MACCARRONE M. Experimental parkinsonism alters endocannabinoid degradation: implications for striatal glutamatergic transmission. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6900–6907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06900.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILDEMAN D.A., MITCHELL T., TEAGUE T.K., HENSON P., DAY B.J., KAPPLER J., MARRACK P.C. Reactive oxygen species regulate activation-induced T cell apoptosis. Immunity. 1999;10:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLARD C.J., JARRAHIAN A. The movement of N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) across cellular membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000;108:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFMANN T.G., MOLLER A., HEHNER S.P., WELSCH D., DROGE W., SCHMITZ M.L. CD95-induced JNK activation signals are transmitted by the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), but not by Daxx. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;93:185–191. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG S.M., BISOGNO T., TREVISANI M., AL-HAYANI A., DE PETROCELLIS L., FEZZA F., TOGNETTO M., PETROS T.J., KREY J.F., CHU C.J., MILLER J.D., DAVIES S.N., GEPPETTI P., WALKER J.M., DI MARZO V. An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:8400–8405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122196999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUNG M.Y., KANG H.J., MOON A. Capsaicin-induced apoptosis in SK-Hep-1 hepatocarcinoma cells involves Bcl-2 downregulation and caspase-3 activation. Cancer Lett. 2001;165:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM T.H., ZHAO Y., BARBER M.J., KUHARSKY D.K., YIN X.M. Bid-induced cytochrome c release is mediated by a pathway independent of mitochondrial permeability transition pore and Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39474–39481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISCHKEL F.C., HELLBARDT S., BEHRMANN I., GERMER M., PAWLITA M., KRAMMER P.H., PETER M.E. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:5579–5588. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAMMER P.H. CD95's deadly mission in the immune system. Nature. 2000;407:789–795. doi: 10.1038/35037728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROEMER G., MARTÍNEZ A.-C. Pharmacological inhibition of programmed lymphocyte death. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE M., YANG K.H., KAMINSKI N.E. Effects of putative cannabinoid receptor ligands, anandamide and 2-arachidonyl-glycerol, on immune function in B6C3F1 mouse splenocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;275:529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE Y.S., NAM D.H., KIM J.A. Induction of apoptosis by capsaicin in A172 human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;161:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI H., ZHU H., XU C.J., YUAN J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACCARRONE M., LORENZON T., BARI M., MELINO G., FINAZZI AGRO A. Anandamide induces apoptosis in human cells via vanilloid receptors. Evidence for a protective role of cannabinoid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31938–31945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHO A., BLAZQUEZ M.V., NAVAS P., MUNOZ E. Induction of apoptosis by vanilloid compounds does not require de novo gene transcription and activator protein 1 activity. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:277–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHO A., CALZADO M.A., MUNOZ BLANCO J., GOMEZ DIAZ C., GAJATE C., MOLLINEDO F., NAVAS P., MUNOZ E. Selective induction of apoptosis by capsaicin in transformed cells: the role of reactive oxygen species and calcium. 1999;6:155–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHO A., LUCENA C., CALZADO M.A., BLANCO M., DONNAY I., APPENDINO G., MUNOZ E. Phorboid 20-homovanillates induce apoptosis through a VR1-independent mechanism. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHO A., LUCENA C., SANCHO R., DADDARIO N., MINASSI A., MUNOZ E., APPENDINO G. Non-pungent capsaicinoids from sweet pepper synthesis and evaluation of the chemopreventive and anticancer potential. Eur. J. Nutr. 2003;42:2–9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-003-0394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANSOURI A., RIDGWAY L.D., KORAPATI A.L., ZHANG Q., TIAN L., WANG Y., SIDDIK Z.H., MILLS G.B., CLARET F.X. Sustained activation of JNK-p38 MAP kinase pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- MECHOULAM R., BEN SHABAT S., HANUS L., FRIDE E., VOGEL Z., BAYEWITCH M., SULCOVA A.E. Endogenous cannabinoid ligands – chemical and biological studies. J. Lipid Mediat. Cell. Signal. 1996;14:45–49. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(96)01507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELCK D., BISOGNO T., DE PETROCELLIS L., CHUANG H., JULIUS D., BIFULCO M., DI MARZO V. Unsaturated long-chain N-acyl-vanillyl-amides (N-AVAMs): vanilloid receptor ligands that inhibit anandamide-facilitated transport and bind to CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;262:275–284. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENG X.W., HELDEBRANT M.P., KAUFMANN S.H. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate inhibits death receptor-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat cells by disrupting recruitment of Fas-associated polypeptide with death domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3776–3783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHEAU O., SOLARY E., HAMMANN A., DIMANCHE-BOITREL M.T. Fas ligand-independent, FADD-mediated activation of the Fas death pathway by anticancer drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7987–7992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAWAKI T., UEHARA T., NIBU R., TSUJI T., YACHIE A., YONEHARA S., TANIGUCHI N. Differential expression of apoptosis-related Fas antigen on lymphocyte subpopulations in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 1992;149:3753–3758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAROLARO D., MASSI P., RUBINO T., MONTI E. Endocannabinoids in the immune system and cancer. Prostagland. Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2002;66:319–332. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETIT P.X., O'CONNOR J.E., GRUNWALD D., BROWN S.C. Analysis of the membrane potential of rat- and mouse-liver mitochondria by flow cytometry and possible applications. Eur. J. BioChem. 1990;194:389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUCCI B., BELLINCAMPI L., TAFANI M., MASCIULLO V., MELINO G., GIORDANO A. Paclitaxel induces apoptosis in Saos-2 cells with CD95L upregulation and Bcl-2 phosphorylation. Exp. Cell. Res. 1999;252:134–143. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICE A.S., FARQUHAR-SMITH W.P., NAGY I. Endocannabinoids and pain: spinal and peripheral analgesia in inflammation and neuropathy. Prostagland. Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2002;66:243–256. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUIZ-RUIZ C., ROBLEDO G., FONT J., IZQUIERDO M., LOPEZ-RIVAS A. Protein kinase C inhibits CD95 (Fas/APO-1)-mediated apoptosis by at least two different mechanisms in Jurkat T cells. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4737–4746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANCHO R., CALZADO M.A., DI MARZO V., APPENDINO G., MUNOZ E. Anandamide inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation through a cannabinoid receptor-independent pathway. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:429–438. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARKER K.P., OBARA S., NAKATA M., KITAJIMA I., MARUYAMA I. Anandamide induces apoptosis of PC-12 cells: involvement of superoxide and caspase-3. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCAFFIDI C., FULDA S., SRINIVASAN A., FRIESEN C., LI F., TOMASELLI K.J., DEBATIN K.M., KRAMMER P.H., PETER M.E. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCAFFIDI C., SCHMITZ I., ZHA J., KORSMEYER S.J., KRAMMER P.H., PETER M.E. Differential modulation of apoptosis sensitivity in CD95 type I and type II cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22532–22538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMART D., GUNTHORPE M.J., JERMAN J.C., NASIR S., GRAY J., MUIR A.I., CHAMBERS J.K., RANDALL A.D., DAVIS J.B. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERNER O., SZALLASI A. Novel natural vanilloid receptor agonists: new therapeutic targets for drug development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZALLASI A. Vanilloid receptor ligands: hopes and realities for the future. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:561–573. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBERRY N.A., LAZEBNIK Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIMMER T., DE VRIES E.G., DE JONG S. Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis: a clinical application. J. Pathol. 2002;196:125–134. doi: 10.1002/path.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEDA N., PUFFENBARGER R.A., YAMAMOTO S., DEUTSCH D.G. The fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000;108:107–121. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAILLANT F., LARM J.A., MCMULLEN G.L., WOLVETANG E.J., LAWEN A. Effectors of the mammalian plasma membrane NADH-oxidoreductase system. Short-chain ubiquinone analogues as potent stimulators. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1996;28:531–540. doi: 10.1007/BF02110443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACH D., BOLDIN M., VARFOLOMEEV E., BEYAERT R., VANDENABEELE P., FIERS W. Cell death induction by receptors of the TNF family: towards a molecular understanding. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLVETANG E.J., LARM J.A., MOUTSOULAS P., LAWEN A. Apoptosis induced by inhibitors of the plasma-membrane NADH-oxidase involves Bcl-2 and calcineurin. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1315–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT P.M., PETERSSON J., ANDERSSON D.A., CHUANG H., SORGARD M., DI MARZO V., JULIUS D., HOGESTATT E.D. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]