Abstract

The aim of this work was to study the effects of N-salicyloyltryptamine (STP), a novel anticonvulsant agent, on voltage-gated ion channels in GH3 cells.

In this study, we show that STP at 17 μM inhibited up to 59.2±10.4% of the Ito and 73.1±8.56% of the IKD K+ currents in GH3 cells. Moreover, the inhibitory activity of the drug STP on K+ currents was dose-dependent (IC50=34.6±8.14 μM for Ito) and partially reversible after washing off.

Repeated stimulation at 1 Hz (STP at 17 μM) led to the total disappearance of Ito current, and an enhancement of IKD.

In the cell-attached configuration, application of STP to the bath increased the open probability of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels.

STP at 17 μM inhibited the L-type Ca2+ current by 54.9±7.50% without any significant changes in the voltage dependence.

STP at 170 μM inhibited the TTX-sensitive Na+ current by 22.1±2.41%. At a lower concentration (17 μM), no effect on INa was observed.

The pharmacological profile described here might contribute to the neuroprotective effect exerted by this compound in experimental ‘in vivo' models.

Keywords: Anticonvulsant, patch clamp, Maxi-BKCa, N-salicyloyltryptamine, calcium channels, sodium channels

Introduction

A number of therapeutic approaches are utilized with the aim of controlling epileptic seizures that affect a significant proportion of the human population. One approach is to develop new pharmacological agents that inhibit neuronal hyperexcitability, presumably one of the causes of seizure activity. Neuronal hyperexcitability is a complex phenomenon related to ion channel function, which, as seen in different animal models, can provoke epileptic seizures. Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels have a fundamental role in neuronal action potential discharge that is probably altered during seizure episodes. STP, a new analogue of N-benzoyltryptamine, was shown to produce anticonvulsant effects by reducing the number of animals that experienced seizure activity in both pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) and maximal electroshock models (Oliveira et al., 2001). As far as we know, there have been no cellular electrophysiological studies with STP to examine its mechanisms of action.

We have focused on the effects of STP on electrophysiological parameters which strongly influence neuronal excitability including: (1) voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca2+ currents and (2) voltage- and Ca2+-dependent K+ currents. By gathering a large picture on the STP-mediated effects on neuronal excitability, we hope to understand the putative correlation between the basic mechanisms of action at the cellular level and in vivo studies.

Methods

Cell culture

GH3 cells (American Type Culture Collection), a rat neuroendocrine cell line, were cultured in DMEM-HEPES modification (Sigma, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cultilab, Brazil). The cells were routinely grown as stocks in 75 cm2 flasks (Costar, U.S.A.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. The medium was changed twice a week. For electrophysiological recordings, the cells were subcultured on glass coverslips (Corning, #1, U.S.A.), and plated in 47 mm dishes.

Electrophysiology

In most experiments (19 out of 24), the whole-cell mode of the patch-clamp technique was used (Hamill et al., 1981). The electrodes were pulled on a PP-83 two-stage puller (Narishige, Japan) from both soft (∼1.5 mm nonheparinized microhematocrit glass capillaries, Selecta, Brazil) and borosilicate glass capillaries (1.5 mm diameter, Clark, U.K.). The pipette resistance was 2–5 MΩ when filled with the appropriate pipette solution.

Membrane currents were recorded through a HEKA-EPC 9 amplifier with pulse, and pulse-fit acquisition and analysis software (Instrutech, Germany). To minimize space-clamp problems, only isolated cells were selected for recording. Cells were not accepted for recording if the initial seal resistance was <2 GΩ. Voltage errors were minimized using series resistance compensation (generally 50–70%). Cancellation of the capacitance transients and leak subtraction was performed using a programmed P/4 protocol (Bezanilla & Armstrong, 1977). Time-course and current–voltage data were typically collected by recording responses to a fixed step pulse (usually 0 mV, unless otherwise indicated) or a consecutive series of step pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV, at intervals of +10 mV. Data collection was initiated approximately 3–5 min after break-in, when control membrane currents had stabilized. Data were always recorded during continuous perfusion of the clamped cell with extracellular solution. STP effects were tested by recording both time-course and I–V sequences, first in control conditions, and then during perfusion with a test solution containing STP at the desired concentration, and again, when possible, after STP washing off to test for reversibility. There were no corrections for liquid junction potentials.

Single-channel recordings

Currents flowing through single (or in few cases multiple) Maxi-K channels in patches of surface membrane from GH3 cells were recorded using the patch-clamp technique. All recordings were made using the cell-attached configuration. Maxi-K channels were identified by their large conductance, and characteristic voltage and Ca2+ dependence (Barrett et al., 1982; Kaczorowski et al., 1996). All experiments were done at room temperature (25–28°C), and the solutions used in each procedure are shown in Table 1. Data acquisition and voltage protocols were controlled by a HEKA-EPC9 amplifier controlled by the Pulse software (Instrutech, Germany). Current traces were filtered at 2.5 kHz (4-pole Bessel Filter), and acquired on a MacPC computer at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz.

Table 1.

Ionic composition of solutions (mM)

| NaCl | KCl | CsCl | HEPES | CaCl2 | CdCl2 | Glucose | MgCl2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing solutions (pH 7.4) | ||||||||

| Na+ currents | 140.0 | — | 5.4 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 0.5 |

| Ca2+ currents | 140.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 20.0a | — | 5.0 | — | |

| K+ currents | 140.0 | 5.0 | — | 10.0 | 2.0 | — | 10.0 | — |

| Maxi-BKca | — | 150.0 | — | 5.0 | 0.001 | — | — | — |

| Pipette solutions (pH 7.2) | ||||||||

| Na+ currents | 10.0 | — | 130.0 | 5.0 | — | — | ||

| Ca2+ currents | 10.0 | — | 130.0 | 10.0 | — | — | ||

| K+ currents | 10.0 | 130.0 | — | 10.0 | — | — | ||

| Maxi-BKca | — | 150.0 | — | 5.0 | — | — | — | 1.0 |

To measure Ca2+ currents, we substituted BaCl2 for CaCl2 equimolarly.

Single-channel analysis

Continuous gap-free records containing one or few channels were collected and stored in a computer. Off-line analyses were carried out using the AXGOX 3 software developed by Dr Noel W. Davies, University of Leicester. The average current was calculated from amplitude histograms, and the open time probability (Popen) was calculated by the method of 50% threshold to detect open and closed events (Beirao et al., 1994).

Solutions

See Table 1 for composition.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Comparison of data was performed by one-way analysis of variance, followed, when necessary, by Bonferroni test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prism (GraphPad Software, CA, U.S.A.) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Effect of STP on Na+ currents in GH3 cells

Figure 1 (panels (a) and (b)) shows typical results from the conventional patch-clamp whole-cell technique for pulses from −80 to 0 mV (20 ms duration) to elicit fast transient inward currents (Figure 1a), which is a characteristic of Na+ currents in GH3 cells. It can be seen that the amplitude of peak inward current was decreased about 25% after application of 170 μM STP. This inhibition could be reversed almost completely by washing the drug off. The vehicle (Cremophor) was tested and there was no effect on the Na+ current (data not shown). Figure 1b represents the time course of change in peak INa in representative cells exposed to 170 μM STP. Depolarizing voltage steps were given every 5 s (upper panel, 0.2 Hz) or every 0.5 s (bottom panel, 2 Hz). In each cell investigated, after control current traces were collected. STP solution (170 μM) was perfused into the bath. The amplitude of peak currents was reduced in the presence of STP, reaching a maximal effect after ∼60 s, and reversed 60–80 s after the onset of washing out the drug. The results presented here indicate that STP inhibits Na+ channels through a mechanism that seems to be independent of the frequency rate. Peak INa amplitude, normalized relative to cell capacitance (pA/pF), was plotted as a function of voltage, to generate I–V relationships (Figure 1c). The currents activated around −40 mV, and gradually reached maximal activation at 0 mV. A comparison of the I–V curves shows that STP at 170 μM evoked a significant decrease of INa amplitude by 22.12±3.41% (P<0.05, n=5). We have also performed experiments testing STP at 17 μM on INa, but we did not observe any significant effect (data not shown, n=3).

Figure 1.

STP decreased Na+ currents in GH3 cells. (a) Current tracings elicited by step depolarizations from −80 to 0 mV for 20 ms duration, before 170 μM STP (1), under STP (2), and after the removal of STP (3). (b) Upper panel – typical time course of INa, for a representative GH3 cell elicited by 170 μM STP. STP induced a decrease of INa amplitude (2) that was almost completely reversed by washing out the drug (3). Bottom panel – lack of frequency dependence of STP block in GH3 cells. Na+ channels were activated with a test pulse to 0 mV (20 ms), from a holding potential of −80 mV at 2 Hz. There were no significant differences in the amount of block when pulses were applied at higher frequencies. (c) Current–voltage relationship of INa in control conditions (open circles, n=5), in the presence of 170 μM STP (closed circles, n=5), and after washout (open squares, n=5). The bars represent mean±s.e.m. (d) Summary of the effects of STP on INa. STP-induced inhibition is expressed as percentage of control. The control peak current measured at 0 mV was considered as 100% (blank bar graph). Values are mean±s.e.m. with five different experiments. *Statistically different at P<0.05.

Effects on L-type Ca2+ channels

L-type Ca2+ channel currents were recorded with Ba2+ as the charge carrier. Na+ currents were blocked by adding TTX (300 nM) to the external solution, and K+ currents were inhibited by using Cs+-based pipette solution. The major effect of STP (17 μM) was to decrease the amplitude of L-type Ca2+ currents. Figure 2a shows records of membrane currents of a typical GH3 cell under voltage clamp. The currents were elicited by depolarizing the cell to 0 mV for 50 ms, from a holding potential of −80 mV every 5 s. These currents inactivated very slowly during the depolarization. STP at 17 μM inhibited approximately 65% of the total current through Ca2+ channels. Block of current through Ca2+ channels occurred faster than block of INa. After application of STP (17 μM), a steady-state block of the Ba2+ current was achieved within about 1 min (Figure 2b(2)). However, the effect of 17 μM STP was only partially reversible during 2 min washout (Figure 2b(3)). The composite I–V relationship of IBa is shown in Figure 2c (IBa amplitude was normalized to cell capacitance). IBa began to activate at −40 mV, and its amplitude increased gradually, with depolarization attaining the maximal amplitude at +10 mV (pA/pF −18.5±3.6, n=5) and at 0 mV (pA/pF −9.9±1.1, n=5) for control and in the presence of STP (17 μM), respectively. This result suggests that STP under our experimental conditions may modify the activation process of L-type Ca2+ channels in GH3 cells. In the presence of 17 μM STP, the current density amplitude of IBa at +10 mV was 45.06±7.50% (n=5) of its control value. Figure 2d summarizes the results described above. The current density measured at +10 mV in 17 μM STP was normalized to control. The averaged inhibition was 54.9±7.50%. The finding that STP also reduces Ca2+ currents lends support to the idea that STP may be exerting its anticonvulsant effects through multiple mechanisms.

Figure 2.

STP inhibits Ba2+ currents in GH3 cells. (a) Whole-cell Ba2+ currents are activated by test pulses from −80 to 0 mV every 5 s. Control condition (1), in the presence of 17 μM STP (2) and after STP removal (3). (b) Representative time course of the amplitude of IBa, measured every 5 s at 0 mV (holding potential, −80 mV). The cell was first exposed to control extracellular solution. Application of STP (17 μM) induced a significant inhibition (2). After washout, IBa did not return to basal amplitude (3). (c) Mean I–V relationships of Ba2+ currents. Peak inward current normalized to cell capacitance plotted vs test potential for cells recorded in the absence (open circles, n=5), and during STP application (filled circles, n=5). Note that the peak value shifted to the left when the cells were exposed to STP. (d) Percentage block of whole-cell Ba2+ currents by STP (17 μM, n=5). The control peak current measured at +10 mV was considered as 100% (blank bar graph). In all experiments, the holding potential was −80 mV, and 5 mM Ba2+ was used as charge carrier. *Statistically different from control (P<0.05).

Effects on K+ channels

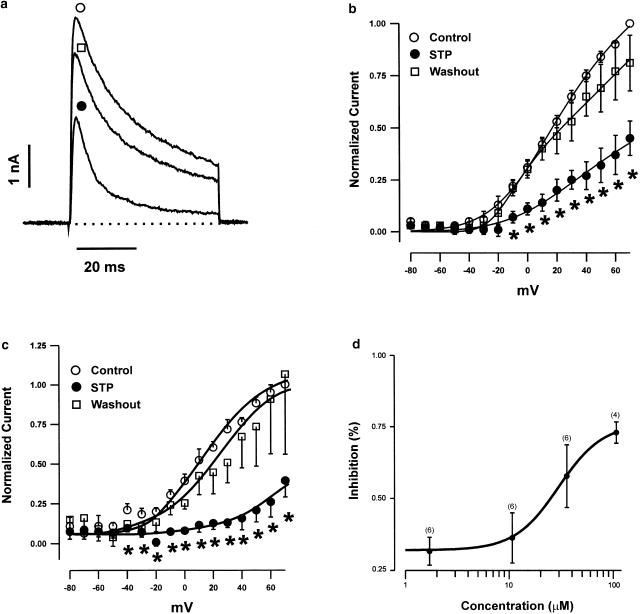

In GH3 cells, a 50 ms depolarizing step, from a holding potential of −80 to +70 mV, activated outward K+ currents that consisted of a rapidly activating and inactivating current (Ito), followed by a delayed noninactivating current (IKD) (Figure 3a). These two currents have already been extensively described by others (Ritchie, 1987; Oxford & Wagoner, 1989). In order to reliably measure the current amplitudes for the two populations of K+ channels, we took the first 10 ms of the depolarizing pulse to measure Ito peak values, and the last 10 ms to measure mean IKD. Figure 3a shows the superimposed current traces recorded in control (open circle), in the presence of 17 μM STP (closed circle), and after washout (open square). The average normalized currents measured from control and STP-exposed cells are plotted as a function of membrane potential in Figure 3b (peak current, Ito) and 3c (mean current, IKD). Sequential comparisons of individual values show a statistically significant decrease in both Ito- and IKD-normalized current from potentials positive to 0 mV. For instance, normalized Ito and IKD at +60 mV in cells exposed to 17 μM STP was significantly reduced (59.1±10.40% for Ito and 73.1±8.6% for IKD, n=5) compared to controls. STP inhibited whole-cell K+ currents of Ito channels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3d). Concentration–response relationships for STP block were fit to a logistic equation of the following form:

|

Figure 3.

Effect of STP on voltage-dependent outward K+ currents in GH3 cells. (a) Current records elicited by step depolarization before (open circle), during the perfusion of 17 μM STP (closed circle), and after STP washout (open square). I–V plots of both the maximal Ito current amplitudes (b), and the mean current at the end of the 50 ms test pulses (c) are shown. Data are mean±s.e.m. of either Ito or IKD current values, normalized to the respective maximal current amplitude measured at +70 mV. (d) Dose–response relationship showing the effect of STP on Ito currents. The percentage of current inhibition corresponds to the fraction of the peak current that is inhibited by different concentrations of STP, compared with the control value of peak current measured at +70 mV. Data points were obtained from 4–6 cells, and were fit by a logistic function (see text for details).

The half-maximal inhibition concentration (IC50) for block of Ito currents was 34.6±8.14 μM (n=4–6 cells).

To investigate the possibility of any use-dependent effects on voltage-dependent K+ currents caused by STP exposure, 20 repetitive 300 ms depolarizing pulses to +50 mV at a frequency of 1 Hz were applied to GH3 cells (n=4 cells). Figure 4a and b shows the representative superimposed original current traces obtained after applying a pulse train at a frequency of 1 Hz in the absence (Figure 4a) and presence of 17 μM STP (Figure 4b). The normalized amplitude of Ito induced by each pulse successively applied in the absence and presence of STP is plotted in Figure 4c. Under control conditions, the peak amplitude of the Ito current slightly decreased during a pulse train. In the presence of 17 μM STP, the peak current amplitude elicited by the first depolarizing pulse was not significantly reduced (Figure 4b), indicating an absence of tonic block. The peak amplitude of Ito thereafter progressively decreased until a new ‘steady-state inhibition' was reached. One important point that should be addressed is the significant increase of the outward current observed during the pulse train, which makes the interpretation of the data presented in Figure 4 rather difficult. However, outward current increase during the pulse train may be related to the STP neuroprotective effect previously described (Oliveira et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

Use-dependent effects induced by STP. Original records obtained in the absence (a) and presence (b) of STP, when applying 20 depolarizing pulses (300 ms in duration) from −80 to +50 mV, at a frequency of 1 Hz. (c) Plot of normalized current under control conditions (open circles) and in the presence of 17 μM STP (closed circles) as a function of the number of pulses. The peak amplitudes of the current at every pulse were normalized to the peak amplitudes of current obtained at the first pulse.

Effect of STP on Maxi-K channels in cell-attached patches

The open probability of the Maxi-K channel is dependent both on membrane potential and [Ca2+]i (Kaczorowski et al., 1996; Lingle et al., 1996; Cui et al., 1997; Gribkoff et al., 1997). In an attempt to determine the possible effect of STP on Maxi-K channel in GH3 cells, we measured single-channel currents under the condition that the open probability was small, but that it could be reliably measured. These experiments were carried out using the cell-attached configuration, and the pipette solution contained K+ at 150 mM. The membrane-patch potential was clamped at +70 mV. Figure 5a(1) (control) and b(1) (in the presence of STP) illustrates how STP modifies gating of a single Maxi-K channel. In control (Figure 5a(3)), channel open probability was low (0.007), and brief bursts of channel openings are separated by long closed periods. Addition of 17 μM STP by using a fast exchange solution device (Leao et al., 2000) to the bath caused an increase in average channel open probability to 0.016 (Figure 5a(3)). A similar effect was observed in four out of five patches analyzed. Inspection of the single-channel record suggests a possible mechanism for activation of the channel by STP. A striking difference from control is the appearance of discrete episodes of high channel open probability in the presence of STP (see Figure 5a(1) and b(1)). Since intracellular Ca2+ is required for activation of Maxi-K channels, and assuming that STP does not substitute for Ca2+ in causing channel opening, one possible mechanism that we can think of is that STP may modify the ability of Ca2+ to open Maxi-K channels. The underlying mechanism by which STP changes the gating of Maxi-K channels was not addressed in the present study.

Figure 5.

Effect of STP on the activity of Maxi-K channels in cell-attached patches. GH3 cells were bathed in high K+ solution (150 mM). The cell was held at +70 mV and the original current record was obtained in control and during the STP application (17 μM) into the bath. Panel (a(1)) shows a typical control record. Panel (b(1)) depicts current traces showing the change in the activity of Maxi-K channels after the addition of STP. Channel openings are shown as an upward deflection. Panels (a(2)) and (b(2)) represent the amplitude histograms in the absence and presence of STP, respectively. All data points shown in the amplitude histograms were fitted by two Gaussian distributions, using the method of maximum likelihood. The closed state corresponds to the peak at 0 pA. (a-3) Shows the calculated open probability for control, and in the presence of STP (17 μM).

Discussion

Anticonvulsants are a chemically diverse class of compounds that share the ability to alleviate the symptoms of epileptic episodes. Several previous studies have shown that these drugs can have different targets and mechanisms of action (Micheli, 2000; Pandeya et al., 2000; Pilip et al., 2000; Bonifacio et al., 2001; Fischer et al., 2001; Freiman et al., 2001; Hassel et al., 2001; Moldrich et al., 2001). In a systematic analysis of the natively expressed ion channels in GH3 cells, we show here that STP follows the general profile already described for other anticonvulsant drugs, but has the unexpected property of enhancing the calcium-activated K+ channel activity, making it a very interesting compound to be investigated.

Current work on epilepsy reveals an expanding list of seizure phenotypes arising from ion channel dysfunctions (Steinlein & Noebels, 2000). Epilepsy arises from the disruption of neuronal firing properties that are determined by the concerted activity of different ion channels. These facts imply that an inhibitory action such as the one reported here could account for the described effect of STP (Oliveira et al., 2001). Anticonvulsant agents have been reported to inhibit voltage-gated ion channels, including Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels (Funahashi et al., 2001; Kwan et al., 2001; Patten et al., 2001). The STP effect on INa current was small, compared with data from other related drugs (Haeseler et al., 2000; 2001; Sun & Lin, 2000; Madeja et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2001). Moreover, unlike these other drugs (Gebhardt et al., 2001), inhibition by STP was not use-dependent. We did not see increased inhibition or faster onset of inhibition when the drug was applied during 2 Hz stimulation compared to 0.2 Hz. Furthermore, STP did not change the INa voltage dependence. Even though the effect of STP on INa was small, Na+ channels may still be a good candidate to explain the blockade of epileptiform discharges, because they are responsible for the membrane depolarization.

Cortical spike-wave discharges have been identified in mice carrying a class of mutations in genes encoding voltage-gated calcium channels (Steinlein & Noebels, 2000). Calcium channels are important regulators of membrane excitability and neurotransmitter release. STP at 17 μM inhibited the total currents through Ca2+ channels by 55%. These cells have been reported to express both T- and L-type Ca2+ channels. However, the absence of fast inactivation in our records suggests that L-type channels dominate in the cells we studied. The strong inhibition of high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels we observed, suggests that modulation of HVA Ca2+ currents plays a role in the efficacy of STP as an anticonvulsant. A similar observation has been published previously, where it was suggested that this class of drugs interacts with the α2δ subunit, which regulates channel gating (Stefani et al., 2001).

There is evidence relating voltage-dependent K+ channels with clinical epileptic phenotypes. Two genes that encode novel voltage-dependent K+ channels of the KQT subfamily are implicated in epilepsy syndromes (Leppert, 2000). Functional studies of these genes showed that KCNQ2/Q3 heteromultimeric channels represent a molecular correlate of the neuronal M-current, which regulates subthreshold electrical excitability (Wang et al., 1998). Retigabine, an anticonvulsant agent, prevents epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine, bicuculline, low Mg2+, and low Ca2+ in hippocampal slices, and seizures induced by PTZ, maximal electroshock, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) in rodents (Wickenden et al., 2000). Retigabine, like many other antiepileptic substances including STP, seems to exert its action via multiple mechanisms. This compound has the ability to open K+ channels in neuronal cells, one feature that sets it apart from currently available anticonvulsant drugs, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate (Rundfeldt, 1997). In a recent paper, Wickenden et al. (2000) showed that retigabine potently enhances KCNQ2/Q3 currents by inducing leftward shifts in the voltage dependence of channel activation.

Our work shows that STP inhibits both the transient outward K+ current and the sustained K+ current in GH3 cells (Figure 3b and c, but see comment in the text). These findings are surprising, as one might assume that they would lead to cellular hyperexcitability. This would be at odds with the general rule of diminished excitability as a general mechanism of anticonvulsant drugs. The most intriguing result that we reported here was the significant increase in the Maxi-K channel activity caused by STP, and, because of its large conductance, it may generate a hyperpolarization which could prevent epileptiform discharges from spreading. Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels are widely distributed in the brain. Maxi-K channels function as neuronal Ca2+ sensors, and contribute to the control of cellular excitability and the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Currently, little is known of any significant role of Maxi-K channels in the genesis of neurological diseases. Recent advances in the molecular biology and pharmacology of these channels have revealed sources of phenotypic variability, and demonstrated that pharmacological agents can successfully modulate them (Shieh et al., 2000).

It is tempting to speculate that activation of Maxi-K channels may be responsible for at least part of the anticonvulsant activity presented by this drug in ‘in vivo' models. Understanding the underlying mechanism by which STP enhances the Maxi-K activity is an important area for future study. All experiments were performed using the cell-attached mode, raising the possibility that the observed effects of STP on Maxi-K channels in GH3 cells may involve intracellular signal transduction pathways.

Taken together, our findings establish that STP has a rather large spectrum of effects at the cellular level. From a functional viewpoint, the composite action of STP may prevent the ability of neuronal cells to generate action potentials. Moreover, structure–activity studies with derivatives of STP could be particularly useful in the development of new compounds that will be more selective, and therefore more effective in the treatment of human epilepsies.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the LAMEX staff for the suggestions and discussions during the development of this project. We are indebted to Drs James Goolsby and Christopher Kushmerick for the critical reading of our manuscript. This work was supported by grants from CNPq, FAPEMIG, and UFPB. RA Mafra, PSL Beirão, and JS Cruz are CNPq Research Fellows.

Abbreviations

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagles' medium

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- HEPES

(N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid])

- HVA

high-voltage activated

- Ito

rapidly activating and inactivating K+ current

- IKD

delayed noninactivating current

- Maxi-BKCa

large-conductance calcium-activated K+ channels

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PTZ

pentylenetetrazol

- STP

N-salicyloyltryptamine

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

References

- BARRETT J.N., MAGLEBY K.L., PALLOTTA B.S. Properties of single calcium activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1982;331:211–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEIRAO P.S.L., DAVIES N.W., STANFIELD P.R. Inactivating ‘ball' peptide from Shaker B blocks Ca2+-activated but not ATP-dependent K+ channels of rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1994;474:269–274. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEZANILLA F., ARMSTRONG C.M. Inactivation of the sodium channel. I. Sodium current experiments. J. Gen. Physiol. 1977;70:549–566. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONIFACIO M.J., SHERIDAN R.D., PARADA A., CUNHA R.A., PATMORE L., SOARES-DA-SILVA P. Interaction of the novel anticonvulsant, BIA 2-093, with voltage-gated sodium channels: comparison with carbamazepine. Epilepsia. 2001;42:600–608. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.43600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUI J., COX D.H., ALDRICH R.W. Intrinsic voltage dependence and Ca2+ regulation of mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;109:647–673. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER W., KITTNER H., REGENTHAL R., MALINOWSKA B., SCHLICKER E. Anticonvulsant and sodium channel blocking activity of higher doses of clenbuterol. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2001;363:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s002100000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREIMAN T.M., KUKOLJA J., HEINEMEYER J., ECKHARDT K., ARANDA H., ROMINGER A., DOOLEY D.J., ZENTNER J., FEUERSTEIN T.J. Modulation of K+-evoked [3H]-noradrenaline release from rat and human brain slices by gabapentin: involvement of KATP channels. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2001;363:537–542. doi: 10.1007/s002100100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUNAHASHI M., HIGUCHI H., MIYAWAKI T., SHIMADA M., MATSUO R. Propofol suppresses a hyperpolarization-activated inward current in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;311:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEBHARDT C., BREUSTEDT J., NOLDNER N., CHATTERJEE S.S., HEINEMANN U. The antiepileptic drug losigamone decreases the persistent Na current in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2001;920:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIBKOFF V.K., STARRETT J.E., Jr., DWORETZKY S.I. The pharmacology and molecular biology of large-conductance calcium-activated (BK) potassium channels. Adv. Pharmacol. 1997;37:319–347. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAESELER G., MAMARVAR M., BUFLER J., DENGLER R., HECKER H., ARONSON J.K., PIEPENBROCK S., LEUWER M. Voltage-dependent blockade of normal and mutant muscle sodium channels by benzylalcohol. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1321–1330. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAESELER G., STORMER M., BUFLER J., DENGLER R., HECKER H., PIEPENBROCK S., LEUWER M. Propofol blocks human skeletal muscle sodium channels in a voltage-dependent manner. Anesth. Analg. 2001;92:1192–1198. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASSEL B., IVERSEN E.G., GJERSTAD L., TAUBOLL E. Up-regulation of hippocampal glutamate transport during chronic treatment with sodium valproate. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:1285–1292. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KACZOROWSKI G.J., KNAUS H.G., LEONARD R.J., MCMANUS O.B., GARCIA M.L. High-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; structure, pharmacology, and function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1996;28:255–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02110699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWAN P., SILLS G.J., BRODIE M.J. The mechanisms of action of commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;90:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEAO R.M., CRUZ J.S., DINIZ C.R., CORDEIRO M.N., BEIRAO P.S. Inhibition of neuronal high-voltage activated calcium channels by the omega-phoneutria nigriventer Tx3-3 peptide toxin. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1756–1767. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEPPERT M. Novel K+ channel genes in benign familial neonatal convulsions. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1066–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINGLE C.J., SOLARO C.R., PRAKRIYA M., DING J.P. Calcium-activated potassium channels in adrenal chromaffin cells. Ion Channels. 1996;4:261–301. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1775-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADEJA M., WOLF C., SPECKMANN E.J. Reduction of voltage-operated sodium currents by the anticonvulsant drug sulthiame. Brain Res. 2001;900:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHELI F. Methylphenylethynylpyridine (MPEP) Novartis. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2000;1:355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLDRICH R.X., BEART P.M., JANE D.E., CHAPMAN A.G., MELDRUM B.S. Anticonvulsant activity of 3,4-dicarboxyphenylglycines in DBA/2 mice. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:732–735. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVEIRA F.A., DE ALMEIDA R.N., SOUSA M.F., BARBOSA-FILHO J.M., DINIZ S.A., DEM I. Anticonvulsant properties of N-salicyloyltryptamine in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001;68:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OXFORD G.S., WAGONER P.K. The inactivating K+ current in GH3 pituitary cells and its modification by chemical reagents. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1989;410:587–612. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANDEYA S.N., MISHRA V., PONNILAVARASAN I., STABLES J.P. Anticonvulsant activity of p-chlorophenyl substituted arylsemicarbazones – the role of primary terminal amino group. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2000. 2000;52:283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATTEN D., FOXON G.R., MARTIN K.F., HALLIWELL R.F. An electrophysiological study of the effects of propofol on native neuronal ligand-gated ion channels. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2001;28:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PILIP S., URBANSKA E.M., SWIADER M., WLODARCZYK D., KLEINROK Z., CZUCZWAR S.J., TURSKI W.A. Anticonvulsant action of chlormethiazole is prevented by subconvulsive amounts of strychnine and aminophylline but not by bicuculline and picrotoxin. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2000;52:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RITCHIE A.K. Two distinct calcium-activated potassium currents in a rat anterior pituitary cell line. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1987;385:591–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUNDFELDT C. The new anticonvulsant retigabine (D-23129) act as an opener of K+ channels in neuronal cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;336:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIEH C.C., COGHLAN M., SULLIVAN J.P., GOPALAKRISHNAN M. Potassium channels: molecular defects, diseases, and therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:558–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEFANI A., SPADONI F., GIACOMINI P., LAVARONI F., BERNARDI G. The effects of gabapentin on different ligand- and voltage-gated currents in isolated cortical neurons. Epilepsy Res. 2001. 2001;43:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(00)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINLEIN O.K., NOEBELS J.L. Ion channels and epilepsy in man and mouse. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000;10:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN L., LIN S.S. The anticonvulsant SGB-017 (ADCI) blocks voltage-gated sodium channels in rat and human neurons: comparison with carbamazepine. Epilepsia. 2000;41:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG H.S., PAN Z., SHI W., BROWN B.S., WYMORE R.S., COHEN I.S., DIXON J.E., MCKINNON D. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channels subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WICKENDEN A.D., WEIFENG Y.U., ZOU A., JEGLA T., WAGONER P.K. Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:591–600. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE X., DALE T.J., JOHN V.H., CATER H.L., PEAKMAN T.C., CLARE J.J. Electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of the human brain type IIA Na+ channel expressed in a stable mammalian cell line. Pflugers Arch. 2001;441:425–433. doi: 10.1007/s004240000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]