Abstract

In this study we describe the ability of two human urotensin-II (hU-II) derivatives [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) and [Pen5,DTrp7,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) (urantide) to block hU-II-induced contractions in the rat isolated thoracic aorta. Both compounds competitively antagonized hU-II- induced effects with pKB=7.4±0.06 (n=12) and pKB=8.3±0.09 (n=12), respectively. In contrast, neither [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) nor urantide (1 μM each) was able to modify noradrenaline- or endothelin 1-induced contractile effects. At micromolar concentrations, [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) produced weak (⩽25% of hU-II maximum) agonist responses in the rat aorta, whereas urantide was totally uneffective as agonist up to 1 μM. In addition, [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) and urantide displaced [125I]urotensin II from specific binding at hU-II recombinant receptors (UT receptors) transfected into CHO/K1 cells (pKi=7.7±0.05, n=4 and pKi=8.3±0.04, n=4, respectively). To our knowledge, urantide is the most potent UT receptor antagonist so far described, and might represent a useful tool for exploring the (patho)physiological role of hU-II in the mammalian cardiovascular system.

Keywords: Urotensin II, UT receptor, urantide, (rat) aorta

Introduction

Urotensin II (U-II) is a cyclic dodecapeptide originally isolated from the teleost fish neurosecretory system (Pearson et al., 1980), and subsequently identified in other species, including man (Coulouarn et al., 1998). The interest in human U-II (hU-II) – an undecapeptide retaining the cyclohexapeptide sequence of fish U-II – has grown enormously in the last few years, following the identification of a specific human receptor (formerly identified as the GPR14/SENR orphan receptor), termed UT receptor (see for review Ames et al., 1999; Maguire & Davenport, 2002). Various studies aiming at investigating the (patho)physiological role played by this peptide in mammals have shown that hU-II produces a very potent vasoconstriction of cynomolgus monkey arteries and human arteries and veins, and potently contracts certain blood vessels from other species, as for example the rat thoracic aorta (Ames et al., 1999; Douglas et al., 2000; Maguire & Davenport, 2002). hU-II has been found 1–2 orders of magnitude more potent than endothelin-1 (ET-1) in producing vasoconstriction, so that it is presently regarded as the most potent mammalian spasmogen identified (Ames et al., 1999; Douglas et al., 2000). The vasoactive responses to hU-II undergo large variations, between and within species, as for the type of vessels sensitive to this peptide than for the contractile efficacy shown by hU-II (see for review Douglas, 2003). Regional differences in responsiveness to U-II of blood vessels have also been reported. This is the case of the rat aorta: a vessel in which the effect produced by either fish U-II (Itoh et al., 1987) or hU-II (Maguire et al., 2000) is maximal in the arch and thoracic portion whereas it is minimal/absent in the abdominal tract. hU-II also produces in vitro and in vivo vasodilation of certain vascular beds (e.g. Bottrill et al., 2000) and exerts potent inotropic effects in the human heart in vitro (e.g. Russell et al., 2001). On the basis of its spectrum of activities, hU-II has been suggested to modulate cardiovascular homeostasis and possibly to be involved in certain cardiovascular pathologies (see for review Douglas, 2003; Russell et al., 2003). However, the role of hU-II awaits to be challenged by development of UT receptor-deprived transgenic animals and by discovery of potent and selective UT receptor antagonists. In this regard, the antagonist compounds so far developed suffer from one or more of the following drawbacks: (1) show weak potency at UT receptors (e.g. SB-710411; Behm et al., 2002; see for further examples Douglas, 2003), (2) bear residual/full agonist activity at UT receptors of certain species (e.g. [Orn8]U-II; Camarda et al., 2002a), (3) possess concomitant antagonist activity at different receptor types (e.g. BIM-23127; Herold et al., 2003).

Here we describe the pharmacological activities of two penicillamine-substituted hU-II peptide fragments: [Pen5, Orn8]hU-II(4–11) and [Pen5, DTrp7, Orn8]hU-II(4–11). This latter peptide, named urantide (urotensin II antagonist peptide), is the most potent UT receptor antagonist compound so far reported in the rat isolated aorta, and is also endowed with high affinity at human UT receptors.

Methods

Organ bath experiments

Male albino rats (Wistar strain, 275–350 g) were decapitated under ether anaesthesia. The thoracic aorta was cleared of surrounding tissue and excised from the aortic arch to the diaphragm. From each vessel, a helically cut strip was prepared, and then it was cut into two parallel strips. The endothelium was removed by gently rubbing the vessel intimal surface with a cotton-tip applicator; the effectiveness of this manoeuvre was assessed by the loss of relaxation response to acetylcholine (1 μM) in noradrenaline (1 μM)-precontracted preparations. All preparations were placed in 5 ml organ baths filled with oxygenated normal Krebs–Henseleit solution. Motor activity of the strips was recorded isotonically (load 5 mN). A cumulative concentration–response curve to hU-II was constructed on one of the two strips, which served as control. The other strip received the antagonist peptide under examination and, after a 30-min incubation period, hU-II was administered cumulatively. Maximal contractile responses of preparations were obtained by administration of KCl (80 mM) at the end of the cumulative curves to hU-II. Antagonist activity was expressed in terms of pKB (negative logarithm of the antagonist dissociation constant) and, assuming a slope of −1.0, was estimated as the mean of the individual values obtained with the equation: pKB=log[dose ratio−1]−log[antagonist concentration] (Kenakin, 1997). Competitive antagonism was checked by the Schild plot method: a plot with linear regression line and slope not significantly different from unity was considered as proof of simple reversible competition (Kenakin, 1997). Ethical approval of the experimental protocol with animals was obtained from the local Ethics committee.

Binding experiments

All experiments were performed on membranes obtained from stable CHO-K1 cells expressing the recombinant human UT receptor (Euroscreen ES-440-M, Bruxelles, Belgium). Assay conditions were: buffer TRIS (20 mM, pH 7.4 at 37°C) added with MgCl2 (5 mM) and 0.5% BSA. Final assay volume was 0.1 ml, containing 1 μg membrane proteins. The radioligand used for competition experiments was [125I]urotensin II (specific activity 2000 Ci−mmol−1; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) in the range 0.07–1.4 nM (corresponding to 1/10–1/5 of its KD). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM of unlabelled hU-II, and ranged between 10–20% of total binding. The incubation period (120 min at 37°C) was terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filter sheets (presoaked in BSA 0.5% for 3 h). Filters were then washed four times with 4 ml of ice-cold TRIS buffer (20 mM). Trapped radioactivity was counted by a Cobra (Canberra-Packard) γ-counter.

Chemicals

Noradrenaline was from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), acetylcholine from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland), ET-1 from Neosystem (Strasbourg, France) and hU-II from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). All other peptides were synthesized by conventional solid-phase methods, as described previously (Grieco et al., 2002).

Results

Functional experiments

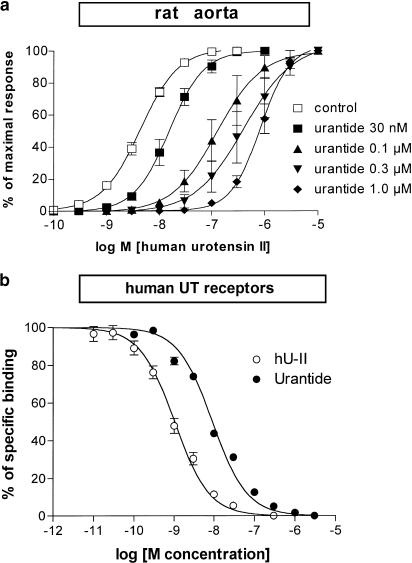

hU-II (0.1–100 nM) produced slowly developing tonic contractions of the rat isolated aorta, whose maxima ranged between 23 and 95% (average 67±5%, n=28) of those produced by KCl 80 mM. As stated before (Grieco et al., 2002), the effects of hU-II in the rat aorta were mimicked by the natural fragment hU-II(4–11) and by the penicillamine-substituted analogue [Pen5]hU-II(4–11) (Table 1 ). In contrast, no agonist effect was observed by cumulative administration of either [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) or urantide, in the range 0.1 nM–10 μM. However, the administration of single concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 1.0 and 10 μM) of [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) produced weak tonic contractile responses, averaging 11, 17, 22 and 25% (n=4–5 each) of the maximal effect produced by hU-II in the control matched preparation. On the other hand, urantide was totally ineffective as an agonist even when administered as a single concentration, up to 1 μM. Both urantide and [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) (30 min before for each) produced a concentration-related competitive inhibition of hU-II-induced contractions (pKB=8.3 and 7.4, respectively) (Table 1; Figure 1). Schild plot analysis (slope=−0.81, 95% c.l. −0.4/−1.2 and slope=−0.95, 95% c.l. −0.5/−1.4, respectively) confirmed the competitive antagonism of both [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) and urantide. Urantide (1 μM) failed to modify noradrenaline-induced contractile responses (pEC50=7.4±0.04 and 7.3±0.04; n=4, in control and in pretreated preparations, respectively) or ET-1-induced contractile responses (pEC50=8.9±0.04 and 9.0±0.02; n=4, in control and in pretreated preparations, respectively). [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) (1 μM) was also ineffective against noradrenaline or ET-1 in the rat aorta (n=4 each; data not shown). In addition, urantide (1 μM) failed to modify acetylcholine-induced relaxations (pEC50=7.0±0.01, Emax=54±10% and pEC50=7.1±0.08, Emax=62±10%; n=4, in control and in pretreated preparations, respectively) in noradrenaline (1 μM)-precontracted preparations bearing intact endothelium.

Table 1.

Functional effects in the rat isolated thoracic aorta, and receptor affinity at recombinant human UT receptors transfected in CHO/K1 cells shown by hU-II derivatives of general formula H-Asp-cyclo[Xaa-Phe-Yaa-Zaa-Tyr-Cys]-Val-OH

| Peptide | Xaa | Yaa | Zaa | pEC50a | pKBb | pKic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hU-II | Cys | Trp | Lys | 8.3±0.06 | — | 9.1±0.06 |

| hU-II(4–11)d | Cys | Trp | Lys | 8.6±0.04 | — | 9.6±0.07 |

| [Pen5]hU-II(4–11)d | Pen | Trp | Lys | 9.6±0.07 | — | 9.7±0.07 |

| [Pen5,Orn8] hU-II(4–11) | Pen | Trp | Orn | NE | 7.4±0.06 | 7.7±0.05 |

| Urantide | Pen | DTrp | Orn | IN | 8.3±0.09 | 8.3±0.04 |

pEC50 (−log EC50) values are from experiments in the rat thoracic aorta.

pKB (−log KB) values are from experiments in the rat thoracic aorta.

pKi (−log Ki) values are from experiments on recombinant human UT receptors.

Data are from Grieco et al. (2002).

NE=not evaluable. IN=inactive up to 10 μM. All data are mean±s.e.m. of 4–12 experiments.

Figure 1.

(a) Blockade by urantide of hU-II-induced contractions in the rat isolated thoracic aorta. (b) Displacement by hU-II and by urantide of [125I]urotensin II specific binding at transfected hUT receptors expressed on CHO/K1 cell membranes. Each value is mean±s.e.m. of 3–4 experiments.

Binding experiments

In homologous competition experiments, [125I]urotensin II saturably bound hUT receptors, with nanomolar affinity (pKD=9.2±0.1; n=4). Likewise, unlabelled hU-II displaced with comparable affinity (pKi=9.1±0.06; n=12) [125I]urotensin II from specific binding on hUT receptors. Urantide or [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) competitively displaced [125I]urotensin II from specific binding on hUT receptors, showing affinities of pKi=8.3 and 7.7, respectively (Table 1; Figure 1).

Discussion

Several compounds of both peptide and nonpeptide nature have now been reported to block hU-II-mediated responses at both rat and human UT receptors (Douglas, 2003). Among the most potent compounds, the hU-II derivative [Orn8]U-II shows consistent agonist efficacy at human and rat UT receptors, acting as full or partial agonist, depending on the bioassay used (Camarda et al., 2002a). SB-710411, a somatostatin peptide antagonist, acts likewise being full agonist at human and monkey UT receptors (Behm et al., 2002). Nevertheless, both compounds have been shown to block competitively hU-II-mediated responses in the rat aorta, with comparable affinities (pKB=6.6 and 6.3 for [Orn8]U-II and SB-710411, respectively). BIM-23127 is a neuromedin B receptor antagonist that is also able to block intracellular calcium increase induced by hU-II in host cells transfected with hUT or rat UT receptors (pA2 7.5–7.7, respectively) (Herold et al., 2003). However, BIM-23127 shows about 0.5 log unit lower affinities in preventing hU-II binding to human or rat UT receptors. Moreover, in the rat isolated aorta bioassay, it acts as a weak (pIC50=6.7) and insurmountable blocker of hU-II-induced contractions (Herold et al., 2003).

Both [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) and urantide are derived from the hU-II(4–11) fragment, chosen as the minimal active portion of hU-II. hU-II(4–11) was conformationally constrained by replacement of Cys5 by penicillamine (ß,ß-dimethylcysteine), in order to stabilize the putative bioactive conformation. Our search led first to the identification of a UT receptor agonist showing ultrapotent activity in the rat aorta: [Pen5]hU-II(4–11) (Grieco et al., 2002; Table 1). The replacement of Lys8 by ornithine in the endocyclic portion of [Pen5]hU-II(4–11) provoked a shift from a very efficacious agonist to an antagonist endowed with residual low agonist efficacy: [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11). Finally, the inversion of the configuration of the Trp residue in position 7, that is, the replacement of Trp7 by DTrp7, was suggested by the presence of the same modification in both BIM-23127 and SB-710411. This further modification yielded urantide: [Pen5,DTrp7,Orn8]h-U-II(4–11). The present results show that urantide is actually the most potent UT receptor antagonist at rat UT receptors, being 50- to 100-fold more potent than any other compound described thus far in the rat isolated aorta bioassay: one of the most reliable and responsive bioassays for studying hU-II-mediated effects (Camarda et al., 2002b). It is worth noting that urantide selectively blocks hU-II-induced effects in the rat aorta, being unable to modify the responses produced by different spasmogenic compounds, such as noradrenaline or ET-1. Moreover, unlike other exisiting UT receptor antagonist compounds, urantide behaves as a simple competitive antagonist in the rat aorta, being devoid of any agonist efficacy even after administration of single micromolar concentrations. In this regard, it is of interest that [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) is capable of producing agonist contractile responses of the rat aorta, but only after administration of single concentrations in the micromolar range. The observed lack of agonist responses to [Pen5,Orn8]hU-II(4–11) administered cumulatively, as well as the poor concentration dependency of its contractile effects, might be due to homologous receptor desensitization, a phenomenon known to affect UT receptor-mediated responses in this preparation (Camarda et al., 2002b). The binding experiments at human UT receptors transfected into CHO/K1 cells have shown that urantide possesses the same high affinity for the human-type (pKi=8.3) as for the rat-type (pKB=8.3) UT receptor. This is actually the highest affinity for the human UT receptor shown by an antagonist compound. Further investigation will be necessary, however, to ascertain whether urantide maintains its antagonist behaviour at human UT receptors. Another question is whether urantide may interact with somatostatin receptors. This possibility would be supported by the high sequence homology existing between U-II and the UT receptor on the one hand and somatostatin and members of the somatostatin receptor family on the other (Liu et al., 1999). As a matter of fact, certain somatostatin receptor ligands interact also with UT receptors (e.g. Behm et al., 2002; Rossowski et al., 2002). While further investigation would be necessary to answer the question, it can be argued that it is unlikely that urantide may also act as a somatostatin receptor ligand, since it does not potentiate ET-1-induced effects in the rat aorta (present results) as do SB-710411 and other somatostatin agonist or antagonist analogues – a phenomenon thought to be closely connected to somatostatin receptor affinity (Behm et al., 2002).

In conclusion, we have shown that a trisubstituted fragment of hU-II [Pen5,DTrp7,Orn8]h-U-II(4–11), or urantide, is a very potent, selective and competitive antagonist on UT receptors in the rat isolated aorta. To our knowledge, urantide is by far the most potent UT receptor antagonist so far described, being about 50- to 100-fold more potent than any other known compound in the rat isolated aorta. Urantide also shows a comparable high affinity for human UT receptors, but its agonist/antagonist behaviour has not been investigated yet. Our data suggest that urantide might be used as a new potent tool for exploring the pathophysiological role of hU-II in the mammalian cardiovascular system.

Abbreviations

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- hU-II

human urotensin-II

- UT receptor

urotensin-II receptor

References

- AMES R.S., SARAU H.M., CHAMBERS J.K., WILLETTE R.N., AIYAR N.V., ROMANIC A.M., LOUDEN C.S., FOLEY J.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., AO Z., DISA J., HOLMES S.D., STADEL J.M., MARTIN J.D., LIU W.S., GLOVER G.I., WILSON S., MCNULTY D.E., ELLIS C.E., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., SHABON U., TRILL J.J., HAY D.W., OHLSTEIN E.H., BERGSMA D.J., DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoconstrictor and agonist for the orphan receptor GPR14. Nature. 1999;401:282–286. doi: 10.1038/45809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEHM D.J., HEROLD C.L., OHLSTEIN E.H., KNIGHT S.D., DHANAK D., DOUGLAS S.A. Pharmacological characterization of SB-710411 (Cpa-c[D-Cys-Pal-D-Trp-Lys-Val-Cys]-Cpa-amide), a novel peptidic urotensin-II receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:449–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOTTRILL F.E., DOUGLAS S.A., HILEY C.R., WHITE R. Human urotensin-II is an endothelium-dependent vasodilator in rat small arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1865–1870. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMARDA V., GUERRINI R., KOSTENIS E., RIZZI A., CALO G., HATTENBERGER A., ZUCCHINI M., SALVADORI S., REGOLI D. A new ligand for the urotensin II receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002a;137:311–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMARDA V., RIZZI A., CALO G., GENDRON G., PERRON S.I., KOSTENIS E., ZAMBONI P., MASCOLI F., REGOLI D. Effects of human urotensin II in isolated vessels of various species; comparison with other vasoactive agents. Naunyn Schmied. Arch. Pharmacol. 2002b;365:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s00210-001-0503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., LIHRMANN I., JEGOU S., ANOUAR Y., TOSTIVINT H., BEAUVILLAIN J.C., CONLON J.M., BERN H.A., VAUDRY H. Cloning of the cDNA encoding the urotensin II precursor in frog and human reveals intense expression of the urotensin II gene in motoneurons of the spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II as a novel cardiovascular target: ‘heart' of the matter or simply a fishy ‘tail'. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003;3:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., SULPIZIO A.C., PIERCY V., SARAU H.M., AMES R.S., AIYAR N.V., OHLSTEIN E.H., WILLETTE R.N. Differential vasoconstrictor activity of human urotensin-II in vascular tissue isolated from the rat, mouse, dog, pig, marmoset and cynomolgus monkey. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1262–1274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIECO P., CAROTENUTO A., CAMPIGLIA P., ZAMPELLI E., PATACCHINI R., MAGGI C.A., NOVELLINO E., ROVERO P. A new, potent urotensin II receptor peptide agonist containing a Pen residue at the disulfide bridge. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:4391–4394. doi: 10.1021/jm025549i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEROLD C.L., BEHM D.J., BUCKLEY P.T., FOLEY J.J., WIXTED W.E., SARAU H.M., DOUGLAS S.A. The neuromedin B receptor antagonist, BIM-23127, is a potent antagonist at human and rat urotensin-II receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139:203–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITOH H., ITOH Y., RIVIER J., LEDERIS K. Contraction of major artery segments of rat by fish neuropeptide urotensin II. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;252:R361–R366. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.2.R361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENAKIN T.P. Pharmacologic Analysis of Drug–Receptor Interaction 1997Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; third edn [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q., PONG S.S., ZENG Z., ZHANG Q., HOWARD A.D., WILLIAMS D.L., JR, DAVIDOFF M., WANG R., AUSTIN C.P., MCDONALD T.P., BAI C., GEORGE S.R., EVANS J.F., CASKEY C.T. Identification of urotensin II as the endogenous ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor GPR14. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;266:174–178. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGUIRE J.J., DAVENPORT A.P. Is urotensin-II the new endothelin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:579–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGUIRE J.J., KUC R.E., DAVENPORT A.P. Orphan-receptor ligand human urotensin II: receptor localization in human tissues and comparison vasoconstrictor responses with endothelin-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:441–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON D., SHIVELY J.E., CLARK B.R., GESCHWIND I.I., BARKLEY M., NISHIOKA R.S., BERN H.A. Urotensin II: a somatostatin-like peptide in the caudal neurosecretory system of fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980;77:5021–5024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSSOWSKI W.J., CHENG B.L., TAYLOR J.E., DATTA R., COY D.H. Human urotensin II-induced aorta ring contractions are mediated by protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases and Rho-kinase: inhibition by somatostatin receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;438:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., MEYERS D., GALBRAITH A.J., BETT N., TOTH I., KEARNS P., MOLENAAR P. Elevated plasma levels of human urotensin-II immunoreactivity in congestive heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:1576–1581. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00217.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., MOLENAAR P., O'BRIEN D.M. Cardiostimulant effects of urotensin-II in human heart in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]