Abstract

Chronic cellular inflammation and airway wall remodelling with subepithelial fibrosis and airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell hyperplasia are features of chronic asthma. Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) may be implicated in these processes by regulating the transcriptional activity of activator protein (AP)-1.

We examined the effects of an inhibitor of JNK, SP600125 (anthra [1,9-cd] pyrazole-6 (2 H)-one), in a model of chronic allergic inflammation in the rat.

Rats sensitised to ovalbumin (OA) were exposed to OA-aerosol every third day on six occasions and were treated with SP600125 (30 mg kg−1 b.i.d; 360 mg in total) for 12 days, starting after the second through to the sixth OA exposure. We measured eosinophilic and T-cell inflammation in the airways, proliferation of ASM cells and epithelial cells by incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), and bronchial responsiveness to acetylcholine.

SP600125 significantly reduced the number of eosinophils (P<0.05) and lymphocytes (P<0.05) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, suppressed eosinophilic (P<0.05) and CD2+ T-cell (P<0.05) infiltration within the bronchial submucosa, and the increased DNA incorporation in ASM (P<0.05) and epithelial cell incorporation (P<0.05).

SP600125 did not alter bronchial hyper-responsiveness observed after chronic allergen exposure.

Pathways regulated by JNK positively regulate ASM cell proliferation and allergic cellular inflammation following chronic allergen exposure.

Keywords: Asthma, mitogen-activated protein kinase, c-Jun-N-terminal kinase, signal transduction, airway inflammation, bronchial hyper-responsiveness

Introduction

Asthma is characterised by a chronic inflammatory process, consisting of eosinophils, lymphocytes and macrophages together with bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR) (Azzawi et al., 1990; Bousquet et al., 1990; Djukanovic et al., 1990; Bradley et al., 1991). One of the consequences of chronic airway inflammation in asthma is remodelling of the airways, which consists of increases in airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass (Dunnill et al., 1969), goblet cell hyperplasia (Laitinen et al., 1985; Aikawa, 2001) and subepithelial fibrosis (Roche et al., 1989). ASM thickening in chronic asthma involves both hyperplasia and hypertrophy of ASM cells (Ebina et al., 1993) and compared with other structural abnormalities in the airways of asthmatics, increased ASM mass is a most important determinant of excessive airway lumen narrowing (James et al., 1989). The mechanisms underlying these ASM changes are complex, involving proinflammatory and mitogenic cytokines and growth factors.

In mammals, three major mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) families that differ in their substrate specificity and responses to stress have been identified and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases such as asthma: c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 kinase (for review, Robinson & Cobb, 1997; Ip & Davis, 1998). The JNK group is activated by exposure of cells to cytokines and to environmental stress (for review, Whitmarsh & Davis, 1996). JNK isoforms, encoded by three genes, phosphorylate-specific sites (serines 63 and 73) on the amino-transactivation domain of c-jun following exposure to ultra-violet (UV) irradiation, growth factors or cytokines (Devary et al, 1992; Kallunki et al, 1994; Kontoyiannis et al, 1999). JNK-1 and JNK-2 have been identified in the lungs of mammals, while JNK-3 has been located to the brain (Bennett et al., 2001). By phosphorylating these sites, JNKs enhance the transcriptional activity of activation protein (AP)-1, which in turn activates a wide range of immunomodulatory genes (Karin, 1995), which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic asthma (Ip & Davis, 1998; Chung & Barnes, 1999). Increased activation and expression of AP-1 has also been demonstrated in the airways of asthmatics (Demoly et al, 1992).

We have previously reported on a model of repeated allergen exposure in sensitised Brown–Norway rats which demonstrates BHR, airway inflammation with eosinophils and lymphocytes, and certain characteristics of airway wall remodelling including increased rates of ASM and epithelial cell DNA synthesis (Salmon et al., 1999a,1999b,1999c). There is also evidence of increased collagen deposition in the sub-epithelium and mucous cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy. In order to examine the role of JNK activation in the pathogenesis of BHR, cellular inflammation and airway cell proliferation following chronic allergen exposure, we used SP600125 (anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazole-6(2H)-one), a newly developed inhibitor of JNK (Bennett et al., 2001). We demonstrated that JNK is partly involved in the T-cell and eosinophilic inflammation, and epithelial and ASM cell proliferation, but not in BHR.

Methods

Animals, sensitisation procedures and allergen-exposure

Pathogen-free inbred male Brown–Norway rats (Harlan Olac Ltd. Bicester, U.K.) (200–250 g, 9–13 weeks old) were injected with 1 ml of 1 mg ovalbumin (OA) in 100 mg Al(OH)3 suspension in 0.9% (wt vol−1) saline intraperitoneally (i.p.) on three consecutive days. OA aerosol exposure (15 min; 1% OA) to rats was performed in a 6.5 l Plexiglas chamber connected to a DeVilbiss PulmonSonic nebuliser (model No. 2512, DeVilbiss Health Care, U.K. Ltd., Middlesex, U.K.) that generated an aerosol mist pumped into the exposure chamber by the airflow supplied by a small animal ventilator (Harvard Apparatus Ltd., Kent, U.K.) set at 60 strokes min−1 with a pumping volume of 10 ml.

Protocol

Three groups of OA-sensitised were studied:

Sham-treated and saline-exposed animals (group saline, n=10): sensitised animals were exposed to aerosolised saline for 20 min, on days 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 and 21 and then studied 18–24 h after the final exposure. Animals received vehicle for SP600125 (20% ethanol with 0.25%CMC/0.25%Tween in 0.2 ml volume) i.p, once a day, on days 12, 15, 18 and 21 of the procedure (total of 12 doses).

Sham-treated and OA-exposed animals (group OA, n=10): the procedures were the same as for group saline, except the aerosol was with 1% OA aerosol.

Sensitised, SP600125-treated and repeatedly OA exposed (SP600125, n=10): the procedures were the same as for group OA. Animals received SP600125 (30 mg kg−1) 2 h prior to antigen exposure on days 12, 15, 18 and 21 (360 mg kg−1 in total).

In order to determine whether the increase in bronchial responsiveness is not confined to acetylcholine (ACh), we also determined responsiveness concomitantly to ACh and 5-hydroxytryptamine aerosols in a separate group of sensitised rats exposed to either saline or to OA aerosols (n=8 in each group), as described above.

SP600125

SP600125 (anthra [1,9-cd] pyrazole-6 (2 H)-one) is a novel JNK inhibitor synthesised by Signal Research Division of Celgene, Inc., San Diego, CA. SP600125 is active against JNK-1, -2 and -3 with IC50s of 0.04–0.09 μM (Bennett et al., 2001). It is selective for JNK because, against several related MAP kinases such as ERK and p38, the IC50 is orders of magnitude higher at >10 μM (Bennett et al., 2001). We used the dose of 30 mg kg−1 which has been shown to inhibit high levels of JNK kinase activity in joint lysates from rats with adjuvant arthritis (Han et al., 2001). We have shown that this dose of SP600125 also inhibits JNK activation following single allergen challenge in the Brown–Norway rat (unpublished).

Measurement of bronchial responsiveness

Animals were anaesthetised with 0.3 ml kg−1. Hypnorm (i.m) consisting of fentanyl 0.315 mg ml−1 and fluanisone 10 mg ml−1 and 1.5 mg kg−1 Hypnovel (i.p.) consisting of midazolam and ventilated (10 ml kg−1 tidal volume; 60 min−1 rate). Rats were monitored for airflow by whole-body plethysmography with a pneumotachograph (Infodisp, Herts, U.K.) connected to a transducer (Infodisp, Herts, U.K.), transpulmonary pressure via an oesophageal catheter connected to a transducer (Infodisp, Herts, U.K.) and blood pressure via carotid artery catheterisation. The signals from the transducers were digitised with an analogue-digital board connected to a Microsoft computer and analysed with Buxco software, which is programmed to instantaneously calculate pulmonary resistance (RL). Aerosol generated from increasing half log10 concentrations of ACh chloride (ACh) was administered by inhalation (45 breaths of 10 ml kg−1 stroke volume) with the initial concentration of 10−3.5 mol l−1 and the maximal concentration of 10–1 mol l−1. The concentration of ACh needed to increase RL 200% above baseline (PC200) was calculated by interpolation of the log concentration–lung resistance curve.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and cell counting

This is described in detail elsewhere (Haczku et al., 1995). Briefly, after an overdose of anaesthetic, rats were lavaged with a total of 20 ml 0.9% sterile saline via the endotracheal tube. Total cell counts, viability and differential cell counts from cytospin preparations stained by May–Grünwald–Giemsa stain were determined under an optical microscope (Olympus BH2, Olympus Optical Company Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). At least 500 cells were counted and identified as macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils according to standard morphology under × 400 magnification.

Collection of lung tissues

After opening of the thoracic cavity and removal of the lungs, the right lung without major vascular and connective tissues was cut into pieces and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C for later assays for mRNA expression. The left lung was inflated with 3 ml saline/Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT) tissue embedding medium (1 : 1). Two blocks of half cm3 were cut from the left lung around the major bronchus, embedded in OCT medium, and snap-frozen in melting isopentane and liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections (6 μm) of the tissues were cut, air-dried, fixed in acetone, and then air-dried again, wrapped in aluminium foil and stored at −80°C for later immunohistochemical studies.

Bromodeoxyuridine dosing

5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine (Sigma Chemicals, Poole, U.K. ) was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and diluted with sterile water, giving a final concentration of DMSO less than 7%. Rats were injected with 50 mg kg−1 (i.p) BrdU in 1 ml of solution immediately following the allergen challenges on days 12, 15, 18 and 21, and received a second dose 8 h later (total of eight injections).

Immunohistochemistry for bromodeoxyuridine and α-smooth muscle actin

As previously described (Salmon et al., 1999a,1999b,1999c), a primary anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody solution (clone BU-1; Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, U.K. ) was applied at 37°C for 75 min. A secondary biotinylated rat adsorbed antiserum to mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, U.K.) was then applied followed by 45 min incubation with a peroxidase linked avidin–biotin complex solution (ABC-Elite kit, Vector Laboratories). Bromodeoxyuridine-positive cells were visualised using 3,3-diaminobenzidinetetrachloride solution (Sigma) with glucose oxidase–nickel enhancement to give a black end-product (Shu et al., 1988). Sections were then rinsed and a primary anti-α-smooth muscle actin, monoclonal antibody (clone 1A4; Sigma) was applied for 1 h at room temperature. A secondary biotinylated rat-adsorbed antiserum to mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories) was applied to the sections, followed by an avidin–biotin complex reagent conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, U.K.). The α-smooth muscle actin staining was visualised using Sigma FAST (4-chloro-2-methylbenzenediazonium/3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid 2,4-dimethylanilide phosphate (α-naphthol AS-MX) and Fast Red TR) in Tris buffer (Sigma) to give a red end-product. Nuclei that were not immunoreactive for BrdU were counterstained by application of the fluorescent DNA ligand 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride (DAPI) (Sigma) at a concentration of 0.0001% and mounted under glass coverslips.

Quantification of DNA synthesis and airway smooth muscle area

Quantification of images was performed using a Zeiss microscope fitted for both transmitted light and fluorescence imaging, with images captured using a colour camera at maximum sensitivity, and analysed using an image analysis system (KS 300 model, Imaging Associates Ltd., Thame, U.K.). The field of interest containing the whole airway was visualised with a × 5 objective using DAPI fluorescence and converted to a digitised image. The airway of interest was identified and internal perimeter, cross-sectional area and maximum breadth (‘feret' diameter which is a caliper measurement obtained when a box is overlaid on the perimeter of the object and rotated around 180°) measured. The airway was then visualised using a × 20 objective, the transmitted light image containing BrdU positive cells captured. Without moving the section, a red fluorescence image of the alkaline phosphatase-Fast Red labelled α-smooth muscle actin immunoreactivity was captured. A blue fluorescence image for DAPI-positive nuclei was then captured and all three images were converted to stored digital images. The area of α-smooth muscle actin immunoreactivity was measured and then a mask created of this region which was overlaid onto the transmitted light image of the same area and the number of BrdU-positively stained nuclei was counted. The mask was then overlaid onto the DAPI fluorescent image and the number of nuclei counted.

DNA synthesis in airway smooth muscle cells was measured as the number of BrdU-immunoreactive nuclei divided by the total number of nuclei (BrdU plus DAPI nuclei) within the α-smooth muscle-actin defined immunoreactive area. Airway smooth muscle thickness was measured as the total α-smooth muscle actin immunoreactive area around each airway (in μm2) per unit length2 (μm2) of basement membrane.

The five largest conducting airways cut perpendicular and lateral to the plane of the airways between the first and second division of the main bronchi from a single lung section was used to calculate the DNA synthesis and ASM thickness indices for rats from each treatment group. As previously described, when using these parameters a standard error of less than ±15% of the mean index is achieved for ASM indices when comparing one against five consecutive sections of lung (Salmon et al., 1999c). All counts in this study were performed with the investigator blinded to treatment group.

Eosinophil and T-cell immunohistochemistry

Staining for eosinophil MBP-positive and CD2+ T cells was performed as previously described (Salmon et al., 1999a,1999b,1999c). In brief, a monoclonal antibody against human MBP (clone BMK-13; Monosan, Uden, The Netherlands) was used on lung sections at a concentration of 1 : 80 for 1 h at room temperature. After labelling with a biotinylated horse anti-mouse monoclonal secondary antibody, positively stained cells were visualised using the alkaline phosphatase-anti-alkaline phosphatase method. For staining of CD2+ T lymphocytes, sections were incubated with mouse anti-rat CD2 monoclonal antibody (pan T-cell markers, Pharmingen, Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, U.K.) at a dilution of 1 : 400 for 1 h at room temperature. After labelling with a biotinylated horse anti-mouse monoclonal antibody, positive cells were visualised by using an avidin–biotin complex reagent conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories) and Sigma FAST. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (BDH, Lutterworth, U.K.) and mounted under glass coverslips.

MBP+ eosinophil and T-cell counts

For detection of eosinophils, we used a mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody against human MBP, clone BMK-13, which has been shown to be both sensitive and specific for staining rat eosinophils in frozen sections (Salmon et al., 1999a,1999b,1999c). The cryostat sections were incubated with BMK-13 at a dilution of 1 : 50 for 30 min at room temperature. After labelling with the second antibody, rabbit anti-mouse IgG, positively stained cells were visualised with alkaline phosphatase–anti-alkaline phosphatase method.

For staining of CD2+ T lymphocytes in tissues, sections were incubated with mouse anti-rat monoclonal antibodies, anti-rat CD2 (pan T-cell marker) antibody at a dilution of 1 : 500 for 1 h. Biotin goat anti-mouse antibody and avidin phosphatase at a dilution of 1 : 200 were applied for 30 min in turn.

For all tissue sections, alkaline phosphatase was developed as a red stain after incubation with Naphthol AS-MX phosphate in 0.1 M trismethylamine-HCl buffer (pH 8.2) containing levamisole to inhibit endogenous alkaline phosphatase and 1 mg ml−1 Fast Red-TR salt. Sections were counterstained with Harris Haematoxylin and mounted in Glycergel. System and specificity controls were carried out for all staining. Slides were read in a coded randomised blinded fashion, under a microscope. Cells within 175 μm beneath the basement membrane were counted in all airways. Submucosal area was quantified with the aid of a computer-assisted graphic tablet. Counts were expressed as cells per mm of basement membrane length.

Measurement of JNK activation in lung tissues

In four rats in each experimental group, lung tissues were obtained. Immunoblot analysis was performed according to Laemmli (1970). Briefly, 50 μg of total lung protein per lane were separated through 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in the following buffer (Tris 20 mM, pH 7.6, NaCl 140 mM and 0.1% Tween) and then incubated for 1 h with affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-nonphosphorylated c-jun (c-jun) (Cell Signalling Technology, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) and antiphosphorylated c-jun (p-c-jun) (Cell Signalling Technology, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) as markers of JNK activity. We used an equal mix of the anti-phosphoserine-63 and -73 antibodies because these sites are important for activation of c-jun. The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse or anti-rabbit (diluted to 1 : 10,000) and ECL reagent was used for detection. Each filter was reprobed with an anti-human α-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, U.K.). The bands, which were visualised by autoradiography, were quantified using a densitometer with Grab-It and GelWorks software (UVP, Cambridge, U.K.).

Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. or 95% confidence interval. For multiple comparisons of different groups, Kruskall–Wallis test for analysis of variance was used. If the Kruskall–Wallis test for analysis of variance was significant, we applied Mann–Whitney U-test for comparison between two individual groups. The data were analysed using Graphpad™ for Windows statistical package. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Bronchial responsiveness to ACh

Bronchial responsiveness to ACh was increased following multiple allergen exposures in sensitised rats from −log PC200 of 1. 86±0.16 to 2.46±0.14 (P<0.05, n=8); in the same rats, −log PC200 to 5-hydroxytryptamine increased from 1.51±0.18 to 2.12±0.21 (P<0.05). There was a significant correlation between −logPC200 ACh and −logPC200 5-hydroxytryptamine (r=0.93; P<0.0001).

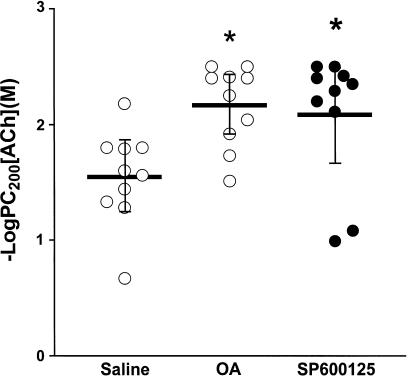

There was no significant difference in baseline lung resistance between the groups (data not shown). There was a significant increase in bronchial responsiveness to increasing concentrations of ACh in the sensitised, repeated allergen-exposed and vehicle-treated rats (−logPC200: 2.16±0.11, 1.91–2.42) (mean; 95% CI) compared to sensitised, repeated saline-exposed and vehicle-treated rats (1.55±0.13, 1.25–1.83, P<0.05, Figure 1). Treatment of repeated allergen-exposed rats with SP600125 did not alter the increased bronchial reactivity to ACh (2.08±0.17, 1.68–2.49, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean −logPC200, which is the negative logarithm of the provocative concentration of ACh needed to increase baseline lung resistance by 200%, after saline, ovalbumin (OA) and after OA with SP600125 administration. There was a significant increase in −logPC200 after chronic OA exposure, indicating BHR. (*P<0.05 as compared to group saline); SP600125 did not alter BHR. Horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group with the bars representing the 95% CI.

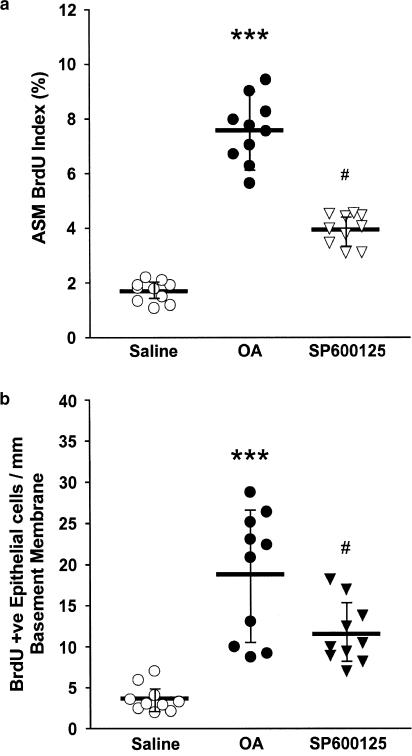

Airway smooth muscle and epithelial BrdU indices

DNA synthesis as measured by BrdU index in airway smooth muscle cells was 1.69% (1.41–1.96) in saline-exposed rats where and increased to 7.58% (6.73–8.426; P<0.001) in allergen-exposed rats. Treatment with SP600125 caused a significant attenuation in the ASM BrdU index (3.94%, 3.53–4.35) compared with the repeated allergen-exposed and vehicle-treated rats (Figure 2a). Repeated allergen exposure resulted in a significant increase in the number of BrdU-positive cells in the epithelium (18.80 mm−1 basement membrane; 13.27–24.33) compared to the sensitised, saline-exposed and vehicle-treated controls (3.64; 2.46–4.82; P<0.01). SP600125 inhibited this response (11.54; 8.85–14.23, P<0.05). Following repeated allergen exposure, there was no significant increase in the area of airway smooth muscle thickness per unit length2 of basement membrane between the saline- and allergen-exposed groups, with the sensitised, allergen-exposed and vehicle-treated group having a mean thickness of 0.018 μm2 μm−2 of basement membrane (0.014–0.022) and the sensitised, saline-exposed and vehicle-treated rats a thickness of 0.017 (0.013–0.021). Treatment with SP600125 did not alter airway smooth muscle thickness compared to the allergen-exposed and vehicle-treated group (0.0178; 0.0131–0.023).

Figure 2.

Effect of SP600125 on (a) airway smooth muscle cell BrdU incorporation, and (b) epithelial cell BrdU incorporation. Treatment with SP600125 attenuated the increase in ASM BrdU index observed after allergen exposure (***P<0.001, as compared to group saline; #P<0.05 as compared to group OA). Similar results were obtained for BrdU immunoreactive epithelial cells (**P<0.01, compared to group saline; #P<0.05 as compared to group OA). Horizontal bars represent the mean values for each group with the bars representing the 95% CI.

Inflammatory cell responses

There was a significant increase in the numbers of total cells (P<0.001), macrophages (P<0.001), eosinophils (P<0.001), lymphocytes (P<0.001) and neutrophils (P<0.001) recovered in BAL fluid of sensitised rats exposed to OA compared to sensitised rats exposed to saline (Table 1 ). SP600125 significantly reduced the OA-induced increase in eosinophil (P<0.05) and lymphocyte (P<0.05) counts.

Table 1.

Effect of SP600125 treatment on allergen-induced inflammatory cell numbers in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and airway tissue in sensitised rats

| Cell type | Saline | OA | SP600125 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAL totala | 80.0±8.69 | 320.0±39.59*** | 298.3±37.69 |

| BAL macrophagesa | 79.6±8.70 | 207.5±34.03*** | 192.9±15.87 |

| BAL eosinophilsa | 0.24±0.10 | 61.24±7.689*** | 36.75±7.84# |

| BAL lymphocytesa | 0.09±0.07 | 24.9±6.3*** | 11.73±2.6# |

| BAL neutrophilsa | 0.63±0.05 | 26.34±4.58*** | 32.05±6.48 |

| Tissue MBP+ eosinophilsb | 5.13±0.97 | 30.07±1.91** | 20.82±3.25# |

| Tissue CD2+ T cellsb | 20.89±1.23 | 31.59±1.98* | 25.57±1.66# |

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Counts of total cells, macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils were significantly increased in sensitised rats exposed to OA aerosol (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 as compared to group saline). SP600125 treatment decreased the increase in counts of lymphocytes and eosinophils (#P<0.05 as compared to group OA).

The concentration of cells in BAL fluid was × 104 ml−1.

Tissue cells are expressed as cells mm−1 basement membrane.

Allergen exposure of sensitised rats caused a significant increase in the airway submucosal infiltration of MBP+ eosinophils (P<0.01) and CD2+ T lymphocytes (P<0.05; Table 1). SP600125 significantly reduced the OA-induced increase in MBP+ eosinophils (P<0.05) and CD2+ T cells (P<0.05) infiltrating the airway submucosa.

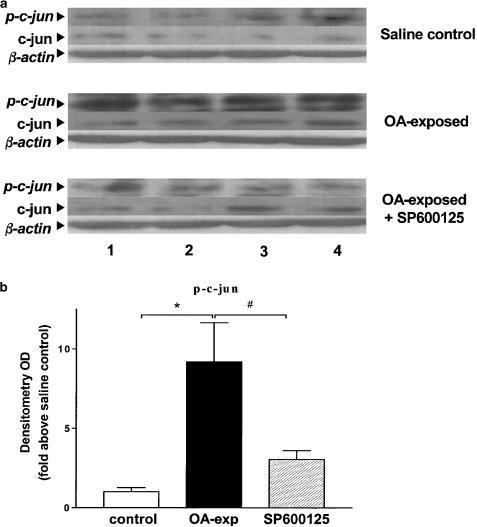

Protein kinase expression

Increased expression of phosphorylated-c-jun (p-c-jun) was detected in lung tissue isolated from four OA exposed and sensitised animals as shown by Western blot analysis (P<0.05, Figure 3a). Pretreatment with SP600125 reduced p-c-jun expression in OA-stimulated sensitised animals (P<0.05, Figure 3b). There were no changes in total c-jun expression after allergen exposure or after pretreatment with SP600125. Equal loading was confirmed by the equal amount of β-actin in the three groups.

Figure 3.

Effect of SP600125 on the phosphorylation of c-jun. (a) Western blot analysis of c-jun and phospho-c-jun in lung tissue from sensitised rats exposed to saline (saline control) or to OA exposed or to OA exposed, pretreated with SP600125 (OA exposed+SP600125). Phospho-c-jun expression was observed in OA-exposed rats and was inhibited in SP600125-treated rats. Results of four rats in each group are shown (labelled 1–4). c-jun expression was not changed. There were also no changes in β-actin. (b) Mean density of phospho-c-jun in the three groups of rats. *P<0.05, as compared to group saline; #P<0.05 as compared to group OA exposed. Data shown as mean±s.e.m.

Discussion

Using a novel potent inhibitor of JNK, SP600125, we evaluated the role of JNK in chronic allergen-induced eosinophilic inflammation and airway smooth muscle and epithelial cell mitogenesis. Following repeated allergen exposure of sensitised Brown–Norway rats, we detected significant increases in both ASM and epithelial cell DNA synthesis, as measured by BrdU incorporation, as we have previously reported (Salmon et al., 1999a,1999b,1999c). There was an increase in eosinophil and CD2+ T-cell accumulation within the airways. We found that SP600125 significantly attenuated ASM and epithelial cell DNA synthesis, and eosinophil and CD2+ T-cell accumulation within the airways. No change in ASM thickness was observed following repeated allergen exposure.

The dose of SP600125 employed in our study inhibited JNK activity as measured by the amount of phosphorylated c-jun levels in the lungs following single allergen challenge of sensitised BN-rats (Eynott et al., 2002). In addition, in an in vivo adjuvant arthritis model in the rat, inhibition of metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction was observed at the same dose of 30 mg kg−1 that we used, with evidence of suppression of JNK activation in the synovium (Han et al., 2001). Based on these previous studies in the rat, we chose a dose of 30 mg kg−1 for our current study. In a previous study, we have demonstrated in the lungs of allergen-exposed sensitised Brown–Norway rats that SP600125 abolished the induction of phospho-c-jun expression, but did not affect the phosphorylated expression of a kinase downstream of p38 MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase (MAPKAPK)-2 (unpublished). This indicates that, in our model, SP600125 selectively inhibited JNK activity in preference to p38 MAPK activity indicating that this compound caused selective inhibition of JNK activity in preference to p38 MAPK activity. Similarly, in this chronic model of allergen exposure, we found evidence of increased phospho-c-jun expression in lung, which was inhibited by SP600125.

In our chronic allergen exposure model, we found an increase in ASM cell and epithelial cell DNA incorporation indicating cell proliferation, and inhibition of JNK by SP600125 inhibited this process. JNK activation has been linked with smooth muscle cell proliferation (Fei et al., 2000; Kyaw et al., 2002) and pharmacological inhibition of JNK activation suppressed vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in vitro (Lu et al., 1998). Other studies have evaluated the involvement of JNK in vivo using gene transfer techniques. Prevention of neointimal hyperplasia by transfer of dominant-negative mutants of JNK has been demonstrated, implicating directly a role for the JNK pathway in smooth muscle cell proliferation (Izumi et al., 2001). The contribution of JNK in this process in vivo is complex because of other potential effects of JNK activation. In previous studies in our chronic allergen exposure model, we found that ASM proliferation was inhibited by an endothelin receptor antagonist, indicating the involvement of endothelin in this process (Salmon et al., 1999a). Inhibition of JNK activity can reduce endothelin-induced ASM proliferation in vitro (Fei et al., 2000). This study suggests that at least partly, endothelin released during chronic allergen exposure may lead to activation of JNK, which in turn leads to the mediation of ASM proliferation.

The level of eosinophils in the airways was inhibited by SP600125 indicating that the JNK pathway may be involved in the recruitment of eosinophils to the airways. The JNK pathway has been implicated in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in inflammatory cells (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999) and of leukocyte adhesion and infiltration (Min & Pober, 1997). Inhibition of cellular recruitment may be explained by inhibition of epithelial expression of adhesion molecules. Inflammatory cells adhere to vascular endothelium and airway epithelium as part of their process of egress into the airway lumen. In human endothelial cell lines, TNF induced E-selectin transcription was associated with the activation of JNK (Min & Pober, 1997). TNFα activation of ICAM-1 expression is also associated with JNK activation (De Cesaris et al., 1999). Other adhesion molecules such as α4-integrin and VCAM-1 may also be regulated by JNK and these may have important roles in the recruitment of T cells and eosinophils during allergen-induced airway inflammation (Nakajima et al., 1994).

Eosinophils may be an important source of growth factors, and therefore may be responsible for ASM proliferation. The increase in ASM and epithelial cell DNA synthesis observed following repeated allergen challenge coincided with a significant increase in both eosinophils and CD2+ T cells infiltrating the airway submucosa. SP600125 also reduced eosinophil and CD2+ T-cell and eosinophil numbers and decreased ASM and epithelial cell proliferation. This does not establish a causative link between eosinophils and T cells, and airway smooth muscle hypertrophy, but direct interaction of activated CD4+ T cells with airway smooth muscle cells can cause airway smooth muscle hyperplasia (Lazaar et al., 1994).

We found no effect of SP600125 on allergen-induced BHR. This lack of effect is unlikely to be due to the initiation of SP600125 administration after the start of OA exposure since in the same experiment, we found inhibitory effects on cellular inflammation and ASM proliferation. Our studies however may shed some light on the complex relationship between BHR and airway remodelling. There is an implicit assumption that an increase in muscle cell mass causes BHR through an increase in the contractile response resulting from an increased number of ASM cells or through an increase in force generated per smooth muscle cells, particularly if there has been hypertrophy. Although we found increased proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells, there was no increase in airway smooth muscle thickness. It is possible that airway smooth muscle thickness increases at later time-points or that there is elongation of the muscle bundles. Changes in phenotype of muscle cells into a hypercontractile state has been induced in vitro (Halayko & Stephens, 1994), but so far, there is little evidence for this occurring in vivo. Nevertheless, the lack of an increase in muscle thickness associated with BHR may invoke hypercontractility of the muscle bundles, as supported by preliminary data in this model demonstrating that bronchiolar muscle cells are hypercontractile to a number of agonist constrictors (Moir et al., 2003). In addition, in our model, we have now demonstrated that BHR is not only demonstrable to one constrictor agent, ACh, but also to another agent, 5-hydroxytryptamine. The role of proliferating ASM cells in BHR is unclear since inhibition of proliferating ASM cells by SP600125 was not associated with a reduction or abolition of BHR. Whether these cells are ‘hypercontractile' is not known.

In summary, the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, inhibited airway eosinophilic inflammation in a model of chronic allergen exposure without affecting BHR. SP600125 was effective in inhibiting both ASM and epithelial DNA incorporation. Activation of the JNK pathway is likely to be partly involved in the cellular inflammation and airway cell proliferation following chronic allergen exposure.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AP-1

activation protein-1

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BHR

bronchial hyper-responsiveness

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- JNK

c-Jun-N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MAPK-APK-2

mitogen-activated protein kinases-activated protein kinase-2

- MBP

major basic protein

- (NF)-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- OA

ovalbumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PC200

provocative concentration of acetylcholine needed to increase lung resistance by 200% above baseline

- Rl

lung resistance

- TNF

Tumour necrosis factor

References

- AIKAWA T.S. Marked goblet cell hyperplasia with mucus accumulation in the airways of patients who died of severe acute asthma attack. Chest. 2001;101:916–921. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.4.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AZZAWI M., BRADLEY B., JEFFERY P.K., FREW A.J., WARDLAW A.J., KNOWLES G., ASSOUFI B., COLLINS J.V., DURHAM S., KAY A.B. Identification of activated T lymphocytes and eosinophils in bronchial biopsies in stable atopic asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;142:1407–1413. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT E.C., SASAKI D.T., MURRAY B.W., O'LEARY E.C., SAKATA S.T., WEIMING X., LEISTEN J.C., MOTIWALA A., PIERCE S., SATOH Y., BHAGWAT S.S., MANNING A.M., ANDERSON D.W. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUSQUET J., CHANEZ P., LACOSTE J.Y., BARNEON G., GHAVANIAN N., ENANDER I., VENGE P., AHLSTED S., SIMONY-LAFONTAINE J., GODARD P. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;323:1033–1039. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010113231505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADLEY B.L., AZZAWI M., JACOBSON B., ASSOUFI J.V., COLLINS A.M., IRANI L.B., SHWATZE S.R., DURHAM JEFFREY P.K, KAY A.B. Eosinophils, T lymphocytes, mast cells, neutrophils and macrophages in bronchial biopsies from atopic asthma: comparison with atopic non-asthma and normal controls and relationship to bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1991;88:661–674. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90160-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG K.F., BARNES P.J. Cytokines in asthma. Thorax. 1999;54:825–857. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.9.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE CESARIS P., STARACE D., STARACE G., FILIPPINI A., STEFANINI M., ZIPARO E. Activation of Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase pathway by tumor necrosis factor alpha leads to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28978–28982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.28978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMOLY P., BASSET S.N., CHANEZ P., CAMPBELL A.M., GAUTHIER R.C., GODDARD P., MICHEL F.B., BOUSQUET J. c-fos proto-oncogene expression in bronchial biopsies of asthmatics. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1992;7:128–133. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVARY Y., GOTTLIEB R.A., SMEAL T., KARIN M. The mammalian ultraviolet response is triggered by activation of Src tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1992;71:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DJUKANOVIC R., WILSON J.W., BRITTEN K.M., WILSON S.J., WALLS A.F., ROCHE W.R., HOWARTH P.H., HOLGATE S.T. Quantification of mast cells and eosinophils in the bronchial mucosa of symptomatic atopic asthmatics and healthy control subjects using immunohistochemistry. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;142:863–871. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNNILL M.S., MASSARELLA G.R, ANDERSON J.A. A comparison of the quantitative anatomy of the bronchi in normal subjects, in status asthmaticus, in chronic bronchitis, and in emphysema. Thorax. 1969;24:176–179. doi: 10.1136/thx.24.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBINA M., TAKAHASHI T., CHIBA T., MOTOMIYA M. Cellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia of airway smooth muscle underlying bronchial asthma. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 1993;148:720–726. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EYNOTT P.R., LEUNG S.-Y., NATH P., ADCOCK I.M., CHUNG K.F. Effects of selective c-JUN NH2-terminal kinase inhibition in a sensitized Brown–Norway rat model of allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2002;165:A315. [Google Scholar]

- FEI J., VIEDT C., SOTO U., ELSING C., JAHN L., KREUZER J. Endothelin-1 and smooth muscle cells: induction of jun amino-terminal kinase through an oxygen radical-sensitive. Mech. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000;20:1244–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACZKU A., CHUNG K.F., SUN J., BARNES P.J., KAY A.B., MOQBEL R. Airway hyperresponsiveness, elevation of serum-specific IgE and activation of T cells following allergen exposure in sensitized Brown-Norway rats. Immunology. 1995;85:598–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALAYKO A.J., STEPHENS N.L. Potential role for phenotypic modulation of bronchial smooth muscle cells in chronic asthma. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994;72:1448–1457. doi: 10.1139/y94-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN Z., BOYLE D.L., CHANG L., BENNETT B., KARIN M., YANG L., MANNING A.M., FIRESTEIN G.S. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IP Y.T., DAVIS R.J. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) from inflammation to development. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZUMI Y., KIM S., NAMBA M., YASUMOTO H., MIYAZAKI H., HOSHIGA M., KANEDA Y., MORISHITA R., ZHAN Y., IWAO H. Gene transfer of dominant-negative mutants of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase prevents neointimal formation in balloon-injured rat artery. Circ. Res. 2001;88:1120–1126. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAMES A.L., PARE P.D., HOGG J.C. The mechanics of airway narrowing in asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989;139:242–246. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALLUNKI T., SU B., TSIGELNY I., SLUSS H.K., DERIJARD B., MOORE G., DAVIS R., KARIN M. JNK2 contains a specificity-determining region responsible for efficient c-Jun binding and phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1994;24:2996–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONTOYIANNIS D., PASPARAKIS M., PIZARRO T.T., COMINELLI F., KOLLIAS G. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KYAW M., YOSHZUMI M., TSUCHIYA K., KIRIMI K., SUZAKI M., ABE S., HASEGAWA T., TAMAKI T. Antioxidants inhibit endothelin-1 (1–31)-induced proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells via the inhibition of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and activator protein-1 (AP-1) Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;15:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAEMMLI U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAITINEN L.A., HEINO M., LAITINEN A., KAVA T., HAAHTELA T. Damage of the airway epithelium and bronchial reactivity in patients with asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1985;131:599–606. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZAAR A.L., ALBELDA S.M., PILEWSKI J.M., BRENNAN B., PURE E., PANETTIERI R.A. T lymphocytes adhere to airway smooth muscle cells via integrins and CD44 and induce smooth muscle cell DNA synthesis. J. Exp Med. 1994;180:807–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU L.H., LEE S.S., HUANG H.C. Epigallocathetechin suppression of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells: correlation with c-jun and JNK. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1227–1237. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIN W., POBER J.S. TNF initiates E-selectin transcription in human endothelial cells through parallel TRAF-NF-kappa B and TRAF-RAC/CDC42-JNK-c-Jun/ATF2 pathways. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3508–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOIR L.M., LEUNG S.Y., EYNOTT P.R., MCVICKER C.G., WARD J.P., CHUNG K.F., HIRST S.J. Repeated allergen inhalation induces phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle in bronchioles of sensitized rats. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003;284:L148–L159. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00105.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAJIMA H., SANO H., NISHIMURA T., YOSHIDA S., IWAMOTO I. Role of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1/very late activation antigen 4 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1/lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 interactions in antigen-induced eosinophil and T cell recruitment into the tissue. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1145–1154. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON M.J., COBB M.H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1997;9:180–185. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCHE W.R., BEASLEY R., WILLIAMS J.H., HOLGATE S.T. Subepithelial fibrosis in the airways of asthmatics. Lancet. 1989;23:520–522. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALMON M., LIU Y.C., ROUSELL J., HUANG T.-J., HISADA T., BARNES P.J., NICKLIN P.L., CHUNG K.F. Endothelin-1 expression in the lungs of sensitised Brown–Norway rats after repeated allergen exposure: contribution to increased airway smooth muscle and epithelial proliferation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1999a;155:618–625. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.5.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALMON M., WALSH D.A., HUANG T.J., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F. Quantitative proliferative changes in the airways of sensitised and chronically challenged Brown–Norway rats: effect of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist pranlukast. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999b;127:1151–1158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALMON M., WALSH D.A., KOTO H., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F. Repeated allergen exposure of sensitized Brown-Norway rats induces airway cell DNA synthesis and remodelling. Eur. Respir. J. 1999c;14:633–641. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14c25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHU S., JU G., FAN L. The glucose oxidase-DAB-nickel method in peroxidase histochemistry of the central nervous system. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;85:169–171. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITMARSH A.J., DAVIS R.J. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Mol. Med. 1996;74:589–607. doi: 10.1007/s001090050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]