Abstract

Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are thought to be important modulators of neuronal function in the superior colliculus (SC). Here, we investigated the pharmacology and signalling mechanisms underlying group I mGluR-mediated inhibition of neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the rat SC slice.

The group I agonist (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) potently depressed synaptically evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs), currents (EPSCs), and action potentials in a dose-dependent manner (IC50: 6.3 μM). This was strongly reduced by the broad-spectrum antagonist (+)-alpha-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG, 1 mM, ∼95% reduction), by the mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (100 μM, ∼80% reduction) but not by the mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP, 1–100 μM).

The putative mGluR5-specific agonist (RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG, 500 μM) also inhibited EPSPs. Interestingly, CHPG's actions were not blocked by MPEP, but LY367385 (100 μM) reduced the effect of CHPG by 50%.

Inhibition induced by DHPG was independent of phospholipase C (PLC)/protein kinase C pathways, and did not require intact intracellular Ca2+ stores. It was not abolished but enhanced by the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (5 μM), suggesting that DHPG's action was not due to facilitated inhibition or changes in neuronal network activity.

The K+ channel antagonist 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 50–100 μM) converted the inhibitory effect of DHPG into facilitation. Paired-pulse depression was strongly reduced by DHPG, an effect that was also prevented by 4-AP.

Our data indicate that group I agonists regulate transmitter release, presumably via an autoreceptor in the SC. This receptor may be involved in adaptation to repetitive stimulation via a non-PLC mediated pathway.

Keywords: DHPG, CHPG, paired pulse depression, slice, presynaptic, autoreceptor, short-term plasticity

Introduction

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) have been divided into three different classes, based on their amino-acid sequence homology, pharmacology and coupling to intracellular signalling cascades. So far, group I comprises mGluR subtypes 1 and 5, and their respective splice variants. While group II and III mGluRs are negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase, group I mGluRs are linked to phospholipase C (PLC) and subsequent production of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), diacylglycerol (DAG), and protein kinase C (PKC) stimulation. Although this scenario has been confirmed in many preparations, additional signalling pathways can also be activated by group I agonists (for reviews, see Anwyl, 1999; Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). For example, production of cAMP and arachidonic acid has been described, as well as a link to voltage-dependent Ca2+ and K+ channels (Anwyl, 1999; Fagni et al., 2000). Furthermore, it was reported that the distribution of mGluR1 and mGluR5 does not always correlate with patterns of IP3 receptor and PKC expression (e.g. Fotuhi et al. 1993), also indicating a link to alternative intracellular pathways. Recently, non-PLC-mediated mechanisms triggered by group I mGluRs, and G-protein-independent coupling of mGluR1 to Src kinase have been demonstrated (Heuss & Gerber, 2000; Benquet et al., 2002; Ireland & Abraham, 2002).

Immunohistochemical studies have suggested a predominantly postsynaptic location for group I mGluRs, with only limited evidence for presynaptic expression (Romano et al., 1995; Luján et al., 1996; Wittmann et al., 2001). However, functional studies suggest that group I mGluRs can modulate glutamate release (Gereau & Conn, 1995; Rodríguez-Moreno et al., 1998; Reid et al., 1999; Mannaioni et al., 2001).

Immunocytochemical studies have revealed weak mGluR1, but strong mGluR5 labelling in the superior colliculus (SC) (Shigemoto & Mizuno, 2000; Cirone et al., 2002b). The SC is a multilayered midbrain structure that receives inputs from various sensory modalities and triggers orientation responses towards novel sensory stimuli (Stein & Meredith, 1993). The superficial SC receives a direct input from the retina, with >90% of retinal ganglion cells projecting to this area in the rat (Dreher et al., 1985) and glutamate is the principle excitatory transmitter at these synapses (Binns & Salt, 1994; Platt & Withington, 1998). Recently, studies on the function of mGluRs in the SC have demonstrated the contribution of group II/III receptors to visual processing (Cirone & Salt, 2000; 2001; Pothecary et al., 2002). Activation of group I mGluRs leads to an inhibition of visual responses by the agonist DHPG in vivo, and this action may be mediated by mGluR1 (Cirone et al., 2002a).

The aim of the present study was therefore to characterise the pharmacology and signalling mechanisms underlying group I mGluR modulation of neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the SC.

Methods

SC slice preparation

SC slices were prepared from Lister-hooded or Wistar rats (3–4 weeks old), as described previously (Platt & Withington, 1997; 1998). All procedures on animals followed institutional guidelines for animal experimentation and were approved by the Home Office. Briefly, animals were terminally anaesthetised with halothane, decapitated, the brain quickly removed and placed into ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM): 129.5 NaCl, 1.5 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.5 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3 and 10 glucose (pH 7.4, continuously gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2). Parasagittal midbrain slices (350 μm) were prepared using a vibratome (Intracell Ltd., Herts, U.K.), and maintained in prewarmed (30°C) aCSF. Experiments commenced after at least 1 h of incubation.

Electrophysiology

Both field and whole-cell recordings were conducted in SC slices. For synaptically evoked responses (ERs), a monopolar stimulation electrode (∼0.5 MΩ, WPI, U.S.A.) driven by a DS2A stimulus isolator (Digitimer, U.K.) was placed in the outermost part of the optic layer. As in previous papers (Platt & Withington, 1998), slices were stimulated every 30 s at 70–80% of the maximum response until a stable baseline was obtained for at least 20 min.

Evoked glutamate-mediated field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs), single-cell EPSPs or postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, U.S.A.). Data were stored on a computer and analysed using the PWIN software package (Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology, Magdeburg, Germany). For field recordings, borosilicate glass electrodes (∼2 MΩ) were filled with aCSF and placed in the superficial grey layer adjacent to the stimulation electrode.

Patch clamp recordings were obtained using the blind patch technique. Patch electrodes (5–12 MΩ) were filled with a standard intracellular solution containing (in mM): 140 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 1 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) and 4 KOH, pH 7.5. Recordings were corrected for the liquid junction potential (−12mV). Whole-cell currents and membrane potentials were also collected using PWIN. Input resistance (IR) was monitored throughout with negative current injections (−50 pA), and cells with irreversible changes of greater than 10% were discarded. In voltage clamp protocols, cells were clamped at a holding potential of –60 mV. QX-314 (10 mM) was included in the intracellular solution to prevent spike attempts and allow measurement of postsynaptic currents. Current and voltage signals were filtered at 5 kHz and digitised at 30 kHz.

For some experiments, Lucifer Yellow (LY, 2 mM) was added to the standard intracellular solution to allow identification of cell types. After recordings were completed, slices were fixed overnight in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (in phosphate buffer (0.1 M) containing and 0.2% picric acid), at 4°C. On the following day, slices were incubated in DMSO for 20 min, mounted on a glass slide using Vectashield (Vector Labs, CA, U.S.A.), visualised and photographed under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Compounds were dissolved in prewarmed, oxygenated aCSF and applied via bath perfusion (perfusion rate: 6–8 ml min−1). Salts for the aCSF were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, U.K.), tetrodotoxin (TTX) was from Alomone (Jerusalem, Israel). All mGluR-related compounds were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, U.K.).

Data analysis

Time courses were calculated relative to baseline values (in %), for both fEPSP slope and amplitude. To pool data in the presence of antagonists, time courses were averaged using 10 points preagonist application as baseline (=100%). Dose–response curves and bar charts show means±s.e.m. For patch clamp recordings, analysis of current and voltage amplitudes was carried out offline. Statistical significance was assessed for data before and during mGluR agonist application using Prism for Windows (Version 3.00, GraphPad Software Inc., CA, U.S.A.). For pairs of data, Student's t-test was conducted, for multiple comparisons one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's multiple comparison or Newmann–Keuls comparison as post hoc tests were performed. Significance was set as P<0.05 (significant) and P<0.01 (highly significant).

Results

DHPG inhibits synaptic transmission in the SC

The action of the mGluR agonist (S)-3,5- dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) on synaptic transmission in the SC slice was initially assessed using extracellular recording techniques (Figure 1). DHPG caused a depression of synaptic transmission that was concentration-dependent and fully reversible up to 500 μM, slope and amplitude were affected to the same extent (Figure 1a). Decreasing and increasing concentrations were applied successively, with no difference in potency or evidence of cumulative actions. LTD-like phenomena, that is, long-lasting suppression of synaptic transmission, as described for other preparations (Palmer et al., 1997; Moult et al., 2002), were only found with high concentrations (1 mM, n=3, data not shown), which are likely to involve nonspecific actions. The concentration–response curve revealed a maximal inhibition of 73%, and an IC50 value of 6.3 μM for DHPG (Figure 1), in line with values reported by others (Schoepp et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of synaptic transmission by the group I mGluR agonist DHPG. (a) DHPG reduced evoked fEPSP amplitude (in mV, circles) and slope (in mV ms−1, triangles) in a reversible and concentration-dependent manner. Illustrated are a time course and sample traces, the scale bar represents 2 mV by 4 ms. In (b) the dose–response relationship depicts maximal inhibition and IC50. The number of experiments performed with each concentration is given in brackets.

Postsynaptic actions of DHPG

Whole-cell current clamp recordings were conducted subsequently to characterise postsynaptic actions of DHPG (10 μM). DHPG applied to 48 SC neurons caused three different types of responses in 40 of these neurons, and no alteration of the membrane potential in the remaining eight cells. Postsynaptic responses are illustrated in Figure 2, as monitored by slow chart recorder traces of the membrane potential.

Figure 2.

Postsynaptic actions of DHPG. (a) Example of a small depolarising response to 10 μM DHPG and a decrease in IR (negative deflections resulted from injection of −50 pA hyperpolarising current pulses. (b) A hyperpolarising response to DHPG, and an increase in membrane noise. (c) Oscillations and biphasic responses to DHPG. (ci) In this cell, DHPG induced a brief hyperpolarisation and bursts of spiking, interspersed with small, short hyperpolarisations. (cii) In a different cell, a depolarisation led to spontaneous bursts of spiking, broken up by hyperpolarisations. Scale bars are 30 s by 10 mV. On the right, cell types identified with LY labelling are displayed for corresponding patterns of responses (WFV–wide field vertical; PIR – piriform; NFV – narrow field vertical). For details, see text.

About half (23/40) of the responding neurons showed a small, transient membrane depolarisation of 6±1 mV (mean membrane potential before DHPG: −61±1 mV), accompanied by a reversible decrease in IR (Figure 2a). For –50 pA current injections, the mean IR calculated for nine neurons changed by 27% (control: 650±65 MΩ, IR decreased by 180±58 MΩ). Occasionally, an increase in input resistance was also observed (n=2).

In 7/40 (18%) of neurons a transient membrane hyperpolarisation of 7±1 mV was observed upon DHPG application, alongside a decreased input resistance, frequently accompanied by an increase in membrane noise (Figure 2b). A third type of response elicited by DHPG was biphasic/oscillatory (Figure 2c), with both hyperpolarising–depolarising and depolarising–hyperpolarising effects (10/40, 25%). Based on the intracellular labelling with LY, cell types were subsequently identified (Figure 2, right panel). A clear-cut correlation between cell type and response to DHPG could not be established, for example, narrow field vertical cells displayed all three types of responses. Pure hyperpolarising responses were not obtained for wide field vertical cells; however, they did show both biphasic and depolarising responses.

Actions of DHPG on neuronal firing

The action of DHPG on neuronal firing was studied both with regards to synaptically evoked spikes and intrinsic, current injection evoked firing. Whole-cell recordings of synaptically ERs in single SC neurons (n=35, Figure 3) revealed an inhibition of evoked spikes by DHPG in the majority of cells (22/35) with stimulus intensities just above spike threshold (Figure 3ai). Counterbalancing of postsynaptic DHPG responses (see above) with continuous current injection did not lead to recovery of synaptically evoked spikes (Figure 3ai).

Figure 3.

DHPG inhibits synaptically ERs in SC neurons. (ai) Experiment where the firing evoked by optic layer stimulation was blocked by DHPG (10 μM). The time course of the spike amplitude of the ER and the resting membrane potential (VR) of the neurone are illustrated. The DHPG-induced depolarisation was counterbalanced with a continuous current injection (‘CI') to re-establish the original VR, which did not lead to spike recovery. Sample traces for time points indicated in the main graph are provided. (aii) In 37% of neurones, synaptic responses were not fully blocked by DHPG but superimposed traces demonstrate the reduced spike amplitude, delay in time-to-peak and reduction of after-depolarisation and late after-hyperpolarisation (lAHP). (b) Intrinsic firing induced by 50 pA current injection was not abolished in DHPG. (bi) The neurone depicted showed a depolarising response (from −62 to –58mV) to DHPG, and some reduction in spike frequency. Changes in input resistance occurred for current injections <−40 pA and >+40 pA, as indicated by the voltage–current relationship plotted in (bii) (c) In voltage clamp, synaptically evoked EPSCs in SC neurons were also inhibited by DHPG. A time course of the EPSC amplitude (in % relative to baseline) and sample traces for the reversible inhibition by DHPG (10 μM) are illustrated. Cells were held at −60 mV, sodium spikes were blocked by QX-314 in the pipette solution. Scale bar: 500 pA, 20 ms.

In comparison, firing induced by depolarising current injections (50–100 pA, 200 ms) was only minimally affected, as illustrated in Figure 3b. The neurone depicted showed a depolarising response (from −62 to –58 mV) to DHPG, and some reduction in spike frequency. Analysis of the voltage–current relationship for current injections from –100 to +40 pA (ΔI: 20 pA) indicated changes in IR below –40 pA and above 40 pA.

Inhibition of evoked spikes occurred independent of the type of postsynaptic response induced by DHPG, and even in cells where no postsynaptic action was observed. Spike production evoked by synaptic stimulation could be restored following washout of DHPG and was overcome by an increase in stimulus intensity in the presence of DHPG. For synaptic responses not fully blocked by DHPG (13/35), and for spikes recovered with increased stimulus intensities, a reduced spike amplitude, delay in time-to-peak and a reduction of after-depolarisation (ADP) and late after-hyperpolarisation (lAHP) was observed (Figure 3aii).

To provide further evidence for a presynaptic action of DHPG, we recorded synaptically-evoked EPSCs in voltage-clamped neurons held at –60 mV. In agreement with the above data, DHPG (10 μM, n=9) reduced evoked EPSCs in a reversible manner (Figure 3c). The mean inhibition of EPSCs in the presence of DHPG was 58±6%. An increase in holding current was observed in 4/9 cells, indicative of simultaneous postsynaptic actions of DHPG.

Pharmacology of group I mGluR actions on synaptic transmission

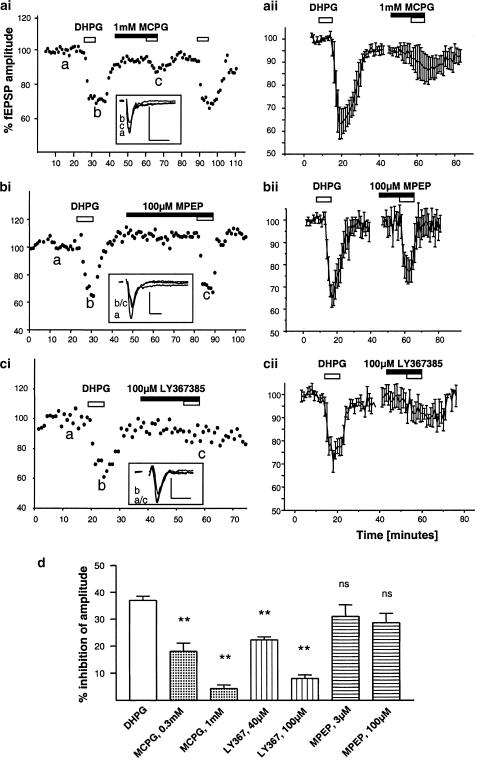

For the characterisation of the pharmacology of group I mGluR-mediated inhibition, various mGluR antagonists were tested for their ability to prevent the action of 10 μM DHPG (Figure 4), which on average caused an inhibition of the fEPSP amplitude of 37±2% (n=38). None of the antagonists were found to affect synaptic transmission as such. Thus, there is no endogenous tone of mGluR activation, and they are apparently not activated by low-frequency glutamate release in the SC slice.

Figure 4.

Pharmacological characterisation of the inhibitory effect of the group I mGluR agonists DHPG. (a) Reduction of the DHPG effect (10 μM) by 1 mM MCPG from a single experiment (ai) and an averaged time course (aii, n=5). Also shown is a third application of DHPG, illustrating the reproducibility of DHPG responses and the reversibility of the antagonist action. (b) inhibition obtained with DHPG in the absence and presence of the specific mGluR 5 antagonists 100 μM MPEP for a single experiment (bi), and averaged data (bii, n=5). (c) The mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (100 μM) affected DHPG's response significantly. Sample traces illustrate fEPSPs for time points indicated in the main graph, scalebars are 1 mV by 5 ms. In (d) the effects of all antagonists are summarised in comparison to the control DHPG response. Nonsignificant (ns) and highly significant (**) differences are denoted.

With regards to the ability of mGluR antagonists to prevent DHGP's action, the broad-spectrum antagonist (+)-alpha-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG) was found to strongly reduce the action of DHPG (Figure 4a). Since the fEPSP slope and amplitude were affected to the same extent (see above), data are shown for the amplitude only for this and subsequent results. At a concentration of 300 μM, MCPG reduced the effects of DHPG by 51% (n=6; P<0.01), while at 1 mM it reduced the DHPG response by 95±2% (n=5; P<0.01, Figure 4a). A control application of DHPG following the combined MCPG/DHPG exposure demonstrated that the effect of DHPG was fully recoverable.

The mGluR5 subtype-selective antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) at a dose of 3 μM, which is reported to substantially block mGluR 5 actions, did not significantly affect DHPG responses (n=6, P>0.05). At the high concentration of 100 μM MPEP showed a trend to reduce DHPG's action, which was, however, not found to be significant (remaining average inhibition: 28±3%; P>0.05, Figure 4b,d).

In comparison, the selective mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (Figure 4c) was much more effective in blocking the actions of DHPG. In the presence of 100 μM LY367385 DHPG inhibited the fEPSPs by only 8±1% (n=6, P<0.01), and even 40 μM LY367385 reduced the inhibitory effects of DHPG from 37±2 to 22±1% (n=5; P<0.01). Data obtained with all antagonists are summarised in Figure 4d.

While the above findings indicated that the action of DHPG on synaptic transmission is mostly mediated by mGluR1, we found that the mGluR5 agonist (R,S)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG) also inhibited synaptic transmission (Figure 5). In agreement with previous reports, this compound was much less potent than DHPG (Doherty et al., 1997), a concentration of 500 μM induced 20±2% inhibition of fEPSPs (n=15). Surprisingly, this action was not significantly affected by either 3 μM (15±4%, n=4, P>0.05) or 100 μM MPEP (17±3%, n=7, P>0.05). In contrast, the mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (100 μM, Figure 5b) had a marked effect, significantly reducing the action of CHPG to 7±2% inhibition (n=5, P<0.05).

Figure 5.

The specific mGluR 5 agonist, CHPG (500 μM), inhibits fEPSPs in the SC. This was not significantly affected by the mGluR 5 antagonist MPEP as illustrated for a single (ai) and an averaged time course (n=5, 3 μM, aii). The mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (100 μM, b), however, reduced the action of CHPG significantly. Data are summarised in part (c), significant differences are indicated (*P<0.05).

Signalling cascades triggered by DHPG action

To identify the signalling cascades underlying the group I agonist-induced inhibition, a series of antagonists for intracellular messenger pathways were examined. Firstly, we used slices incubated with the PLC inhibitor U-73122 (2 μM, Figure 6a, n=8) for 2 h prior to DHPG application (the compound was also present throughout the experiment). In Purkinje neurons, this approach had been found to inhibit DHPG responses (Netzeband et al., 1997), but in SC slices no effect of U-73122 on DHPG responses was obtained (DHPG-induced inhibition in U-73122: 32±2%, P>0.05). Subsequently, we investigated whether PKC activation was necessary for, or involved in, the action of DHPG. The PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (1 μM, n=4, Figure 6b) had neither an effect on baseline synaptic transmission nor modified DHPG's inhibitory action (P>0.05).

Figure 6.

The inhibitory action of DHPG is not mediated via PLC-dependent signalling. (a) Incubation of SC slices with the PLC blocker U-73122 (2 μM) did not affect the action of DHPG. (b) In the presence of the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (1 μM) the DHPG-induced inhibition was also not significantly altered. (c) after application of the irreversible Ca2+-ATPase blocker thapsigargin, which depletes intracellular calcium stores, DHPG still inhibited synaptic transmission as in control conditions. (d) Effects of DHPG in all drug conditions in relation to the control DHPG response (all not significantly different). Sample traces are included in all figures for time points indicated in the main graph. Scale bars: 1 mV by 5 ms.

One of the main routes of action described in many other preparations for group I mGluRs is the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores via IP3 receptors. To establish the possible contribution of such a Ca2+ response to the DHPG-mediated inhibition we applied thapsigargin (2 μM, n=5), which irreversibly blocks the intracellular Ca2+ ATPase, thus causing a depletion of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Rae et al., 2000). After an initial control application of 10 μM DHPG, thapsigargin was applied, followed by subsequent applications of DHPG. The response to the second application of DHPG was not altered (Figure 6c), and even a third application of DHPG produced the same inhibition (not shown). These data are summarised in Figure 6d. Overall, the inhibitory DHPG response could not be attributed to the ‘classic' PLC signalling pathway described for group I mGluRs.

Modulation of voltage-dependent ion channels by DHPG

Group I mGluRs may couple to voltage-dependent Ca2+ (VDCCs) or K+ channels to modulate synaptic transmission. To explore such a connection, the coupling of mGluRs to N-type VDCCs was probed using ω-conotoxin GVIA (CTX), a specific, irreversible antagonist of these channels. This antagonist potently blocked synaptic transmission (Figure 7a), concentrations of 1 μM abolished >90% of the signal (n=3), leaving only the presynaptic fibre volley unaffected (not shown). To establish whether inhibition of N-type VDCCs would occlude or modify the action of DHPG, we applied a concentration of CTX that blocked about 50% of the fEPSP (500 nM, n=8).

Figure 7.

The contribution of calcium and potassium channels to the inhibitory action of DHPG. (a) The N-type calcium channel blocker CTX had a strong effect on synaptic transmission (ai) (in the experiment shown, the stimulus intensity (SI) was increased to compensate for this inhibition), but the DHPG action was not significantly altered, as illustrated for an averaged time course (n=4) with baseline in CTX set to 100% (aii). (b) The L-type channel blocker nifedipine (20 μM, n=9) had no impact on basic synaptic transmission but reduced DHPG's action, as shown for a representative experiment (bi) and averaged data (bii). (ci) The potassium channel blocker 4-AP had a strong effect on amplitude and latency of the fEPSP and abolished the inhibitory action of DHPG. (cii) In patch clamp recordings, 50 μM 4-AP prevented the inhibitory action of DHPC on EPSCs. (d) The GABAA antagonist bicuculline (n=5) affected fEPSPs amplitude (reduction) and duration (increase), and enhanced the inhibitory action of DHPG as indicated by sample traces (inset) and individual time course in (di). (dii) Means calculated relative to baseline data in bicuculline. Sample traces are provided for time points (a–c) indicated, scale bars ai, bi, ci & di: 1 mV by 5 ms, cii: 100 pA by 4 ms. (e) Effects of the DHPG response on the fEPSP amplitude in % change of the fEPSP amplitude. ns: not significant, *significant, **highly significant.

In a subset of experiments (n=5), stimulus intensity was increased to ensure that the lack of postsynaptic activation does not influence the results (Figure 7ai). Irrespective of this, DHPG always inhibited fEPSPs to a similar extent in the presence of CTX in comparison with control conditions (35±5%, P>0.05), as illustrated by the averaged data calculated relative to the fEPSP in the presence of CTX (Figure 7aii).

The effect of the L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist nifedipine (20 μM, n=9) was also studied (Figure 7b). Nifedipine did not alter baseline synaptic transmission and is thus not involved in regulating glutamate release (see also Platt & Withington, 1998). However, nifedipine significantly reduced the inhibitory effects of DHPG from 37±2 to 22±4% (P<0.05).

Taken together, these data suggest that N-type VDCCs are crucial for presynaptic glutamate release, but the inhibitory action of DHPG is not mediated via this route, in contrast to other brain regions where CTX-sensitive VDCCs were identified as the target for inhibition by mGluR agonists (Swartz & Bean, 1992; Glaum & Miller, 1995). L-type VDCCs on the other hand appear to contribute to the action of DHPG. However, even with the relatively high concentration of nifedipine used here, only a small proportion of DHPG-induced inhibition was affected which indicates that this may be an indirect, modulatory effect caused by an overall change in excitability.

Another potential target for inhibition of synaptic transmission is via the modulation of presynaptic K+ channels. To investigate this possibility, we have used the K+ channel antagonist 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; Rodríguez-Moreno et al., 1998; Reid et al., 1999; Wu & Barish, 1999). Application of 4-AP (50 μM–1 mM) had variable effects on the fEPSP amplitude, occasionally causing an enhancement after a transient depression (n=3) but more frequently, a maintained reduction of the amplitude (Figure 7ci, n=6). Consistent with a 4-AP-induced depolarisation, the half-width of the fEPSP always increased (Figure 6ci, sample traces) and an increase in spontaneous activity was indicated by activity patterns observed on the oscilloscope and by additional components that appeared in evoked fEPSPs. Importantly, in the presence of 4-AP (50–100 μM), an inhibitory action of DHPG on synaptic transmission was never observed. Rather, DHPG caused a small but significant enhancement of the fEPSP (by 10±3%, n=6).

To further confirm the role of 4-AP-sensitive K channels in DHPG's action, patch clamp recordings were conducted. In current clamp, 4-AP induced a postsynaptic depolarisation, a delay of spike onset and spike broadening (data not shown). Under voltage clamp conditions, 4-AP application led to a significant rise in the holding current. Peak EPSCs were on average reduced by 16±6% (n=7, Vhold=−60mV, 50 μM 4-AP). In agreement with field recordings, 4-AP was found to abolish the inhibitory action of DHPG on EPSCs (−0.5±6%; Figure 7d). Thus, it can be concluded that coupling to K+ channels, presumable to ID (Wu & Barish, 1999), is a key factor in the inhibitory action of DHPG in the SC.

Since spontaneous activity and generally enhanced excitability may have contributed to the action of 4-AP, we conducted another set of experiments with the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (Figure 7d). These experiments also allowed us to establish whether the inhibitory action of DHPG may be indirect, for example, due to alterations in network activities and/or facilitation of inhibitory transmission. Similar to the effect of 4-AP, bicuculline (5 μM, n=5) application led to prolonged fEPSPs with reduced amplitudes. Interestingly, the inhibitory action of DHPG was found not to be abolished but to be significantly stronger in the presence of bicuculline (P<0.05), thus demonstrating that strengthening of inhibitory transmission is not the cause of DHPG-induced inhibition.

Modulation of paired-pulse depression by DHPG

Paired pulse depression (PPD) and facilitation (PPF) are found at a number of synapses in the CNS. Depression of the fEPSP during repeated stimulation with short interstimulus intervals (ISIs) is an established phenomenon in the superficial SC likely to reflect the tendency of the SC to habituate to repetitive incoming stimuli (Binns and Salt, 1995; 1997; Platt and Withington, 1997). PPD is observed for paired stimulation with ISIs between 10 and 500 ms, and PPD for short intervals (<100 ms) can be converted into PPF when the initial probability of glutamate release is reduced in low Ca2+ solution (Platt & Withington, 1997). Thus, PPD is also a suitable paradigm to probe for mechanisms that modulate transmitter release.

To investigate whether PPD is sensitive to group I mGluR activation, we applied the paired pulse protocol in the presence of 10 μM DHPG (n=6, Figure 8). Data are expressed as the ratio of the amplitude of the second response relative to the first (PP ratio, in %). In agreement with the above data, DHPG depressed the first response of the evoked pair of fEPSPs. More importantly, the second response remained of similar size thus reducing PPD significantly at ISIs of 10 and 40 ms compared to control conditions (P<0.01 and 0.05, respectively). Identical to the effect of a low Ca2+ solution (Platt & Withington, 1997) PPD at the 200 ms ISI was not altered by DHPG indicating that the small depression obtained for ISIs >200 ms may involve other mechanisms such as feedforward or feedback inhibition (Platt & Withington, 1997). PPD was also probed in the combined presence of DHPG and 4-AP (50 μM, n=7). Under these conditions, PP ratios were not different from controls (P>0.05), and PP ratios at 10 ms ISI were significantly different between DHPG and DHPG plus 4-AP. This further confirmed the ability of 4-AP to prevent the action of DHPG.

Figure 8.

PPD in the SC is reduced by DHPG. (a) The PP ratio (amplitude of the second fPEPS in % of the first fEPSP amplitude) is shown for ISIs of 10, 40 and 200 ms. A comparison between PPD in the absence and presence of 10 μM DHPG revealed that PPD is significantly reduced in DHPG at ISIs of 10 and 40 ms (P<0.01 and 0.05, respectively). This effect was abolished by 50 μM 4-AP. Significance is indicated for comparisons with control PP ratios by * and ** for significant and highly significant differences. (b) Sample traces corresponding to the ISIs indicated above in part (a) Stimulus artefacts have been removed and traces truncated between the pairs of fEPSPs (#).

Discussion

This is the first detailed pharmacological characterisation of the actions of group I agonists in the SC. In agreement with a previous report (Cirone et al., 2002b), we found a marked inhibitory action of group I agonists and present evidence that this is mediated via a presynaptic, mGluR1-like receptor. In addition, DHPG had diverse postsynaptic effects, suggesting that group I mGluRs can modulate transmission and excitability via multiple sites. However, the inhibitory presynaptic action was found to dominate, since ERs were suppressed irrespective of postsynaptic actions. This may however differ in the in vivo situation, due to the complex regulation and interactions between multiple inputs into the SC.

Since none of the mGluR antagonists used caused any apparent change in basic synaptic transmission, we conclude that mGluR I receptors are not contributing significantly to low-frequency transmission in the SC slice. In vivo, the combined mGluR1/5 antagonist (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine facilitated visual responses (Cirone et al., 2002b), indicating that endogenous activation of mGluRs can be uncovered when more than one subtype is inhibited. Similar to our investigation, LY367385 was found not to affect visual responses in the SC in this study. In the hippocampus, mGluRs did also not contribute to normal low-frequency synaptic transmission, and high-frequency trains were required to uncover their activation (e.g. Scanziani et al., 1997). Therefore, group I mGluRs may detect prolonged, high-frequency activation and thus contribute to novelty detection within the SC.

Pharmacology of mGluR responses

The sensitivity of the DHPG response to LY367385 and the lack of effect of MPEP antagonism strongly point to an mGluR1-receptor-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission in the SC. Indeed, similar findings were noted by Cirone et al. (2002b), who also demonstrated that DHPG-mediated inhibition of fEPSPs in the SC are sensitive to LY367385 (200 μM) but not MPEP (5 μM). Group I mGluR-mediated inhibition in the hippocampus is also sensitive to LY367385 (Mannaioni et al., 2001). Although the putatively selective mGluR5 agonist CHPG (Doherty et al., 1997) was also effective in our system, its actions were blocked by LY367385 and insensitive to MPEP. In parallel studies in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, CHPG exhibits postsynaptic effects in the presence of MPEP (A.J. Irving & M.G. Rae, unpublished data). Thus, the specificity of CHPG for mGluR5 in the CNS must be questioned.

Given that in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemical studies have indicated a much higher mGluR5 expression compared to mGluR1 in the SC (Mutel et al., 2000; Cirone et al., 2002b) a prominent role for mGluR1 in modulating synaptic transmission was unexpected. However, similar discrepancies have been noted in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, which also appear to lack mGluR1, contradicting functional studies (Valenti et al., 2002). This may indicate the presence of additional (presynaptic) mGluR1-like receptors, not detected with the probes available to date.

Signalling mechanism

The PLC pathway does not appear to be involved in DHPG's action on synaptic transmission in the SC. Inhibitors of PLC (U-73122), PKC (cheletherine) or a Ca2+-store-depleting agent (thapsigargin) did not affect DHPG responses. Evidence for the activation of a non-PLC/PKC transduction mechanism by group I mGluRs in the hippocampus has also been demonstrated previously (Heuss & Gerber, 2000). Moreover, the same group has shown in CA3 pyramidal cells that activation of mGluR1 potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) currents via a G-protein-independent mechanism involving Src kinase activation, whereas mGluR5-mediated enhancement of NMDA currents is G-protein-dependent (Benquet et al., 2002). Recently, evidence for tyrosine kinase and phosphatase involvement in DHPG-mediated actions has been brought forward (Heuss & Gerber, 2000; Benquet et al., 2002, Moult et al., 2002), but the link to mGluRs and details of activation have not been identified yet.

Other targets that can be potentially modulated by mGluRs involve voltage-dependent ion channels such as VDCCs (e.g. Glaum & Miller, 1995; Sayer 1998). While we show here that N-type VDCCS are crucially involved in transmitter release in the SC, a submaximal dose of CTX did not interfere with DHPG-mediated inhibition. This suggests that presynaptic N-type VDCCs are unlikely to be a major target of DHPG action in the SC, in contrast to other preparations (e.g. Swartz & Bean, 1992). For the reduction in inhibitory DHPG action observed in the presence of the L-type VDCC antagonist nifedipine, we suggest this to be caused by an indirect modulation. Nifedipine itself did not alter synaptic transmission and thus mGluR coupling to this channel cannot affect presynaptic release directly. Functional interactions between L-type VDCCS and group I mGluRs have, however, been suggested (Fagni et al., 2000), which can determine general neuronal excitability and signalling cascades.

The most striking reversal of DHPG's action was found with the K+ channel antagonist 4-AP, and even an enhancing response was observed in field recordings. Frequently used as a depolarising agent and to evoke transmitter release, 4-AP was also found to occlude ACPD-mediated actions in hippocampal neurons (Wu & Barish, 1999), thus identifying voltage-dependent K+ currents such as ID as a possible target, in line with data obtained here. In synaptosomal preparations, 4-AP application has also provided evidence for DHPG-induced facilitation of glutamate release in various brain regions, in a PKC-sensitive manner (Reid et al., 1999). In cortical synaptosomes, an initial facilitation of release followed by an inhibition was demonstrated. For this action of DHPG, block of PKC only abolished facilitation and partly reduced the subsequent inhibition (Rodríguez-Moreno et al., 1998). It was concluded that the facilitation is mediated via the PLC-dependent production of DAG, while the inhibition is related to a reduction in Ca2+ influx but does not involve a diffusible messenger (Herrero et al., 1998). It remains to be investigated whether the switch reported is indeed due to the same receptor coupling to different pathways, or caused by the activation of an unusual group I-like receptor, the latter hypothesis being supported by our data.

Presynaptic actions

The inhibitory action of DHPG was found to be enhanced in disinhibited slices thus showing that it is not an indirect effect due to increased GABA release or changed feedback/feedforward inhibitory networks. A similar enhancement of group I mGluR inhibitory actions on excitatory synaptic transmission following blockade of inhibition has been observed in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Harvey et al., 1996).

Evidence for an inhibition of glutamate release in the SC was found with DHPG since synaptically evoked spikes and EPSPs were blocked in whole-cell recordings, while current-injection-induced spiking was only marginally affected. Additionally, inhibitory actions did not depend on the type of the postsynaptic response, and also occurred in voltage-clamped neurons. In agreement with a previous study (Cirone et al., 2002b), it was therefore concluded that presynaptic actions are the cause of the inhibitory profile of DHPG, which was also strongly supported by our data obtained with the paired-pulse paradigm. Similar observations have been made in the hippocampus and subthalamic nucleus, where DHPG enhanced PPF (Manzoni & Bockaert, 1995; Awad-Granko & Conn, 2001). At mossy fibre synapses, frequency-dependent accumulation of glutamate occurs (Scanziani et al., 1997), which leads to a downregulation of transmitter release. In the superficial SC, the modulation of PPD by DHPG is in line with an autoreceptor-dependent feedback mechanism as an effective way to regulate glutamate release and short-term plasticity. The enhancement of the threshold for glutamate release during periods of repetitive incoming signals has also been suggested for presynaptic group II/III mGluRs (Cirone & Salt, 2000; 2001; Pothecary et al., 2002). It therefore remains to be investigated whether different mGluRs act in parallel, or independently at a particular subset of synapses. Presynaptic group I mGluR action may be specific for a particular set of fibres in the optic layer, such as the retinotectal fibres (Cirone et al., 2002b). This pathway makes up the largest proportion of fibres in the optic layer (and is particularly preserved in our sagittal slice preparation) and thus drives the main proportion of glutamatergic transmission at the optic layer – superficial grey layer synapses in the superficial SC. Since maximal inhibition of up to 75% of the fEPSP could be achieved and spike production was prevented by DHPG, it seems possible that the retinotectal input may be regulated by group I mGluRs, though a definite localisation of presynaptic mGluR1 awaits confirmation.

In summary, we report here that group I agonists can regulate synaptic transmission in the SC via 4-AP sensitive K channels, but not via a PLC-dependent pathway. Presynaptic mGluR1-like autoreceptors may be of major importance for feedback regulation of glutamate release and short-term plasticity in the SC.

Abbreviations

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- ACPD

1S,3R-1-aminocyclopentanedicarboxylate

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- ADP

after-depolarising potential

- lAHP

late after-hyperpolarising potential

- CHPG

(R,S)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine

- CTX

ω-conotoxin GVIA

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DHPG

(S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- Em

membrane potential

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- EPSP

excitatory postsynaptic potential

- ER

evoked response

- fEPSP

field excitatory postsynaptic potential

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulphonic acid

- IP3

inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IR

input resistance

- ISI

interstimulus interval

- IV

current–voltage (relationship)

- LTD

long-term depression

- LY

Lucifer Yellow

- MCPG

(+)-alpha-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- MPEP

6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine

- NFV

narrow field vertical (neurone)

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PIR

piriform (neurone)

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PPD

paired pulse depression

- PPF

paired pulse facilitation

- SC

superior colliculus

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VDCC

voltage-dependent calcium channel

- WFV

wide-field vertical (neurone)

References

- AWAD-GRANKO H., CONN P.J. Activation of groups I or III metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits excitatory transmission in the rat subthalamic nucleus. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:32–41. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANWYL R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Brain Res. Rev. 1999;29:83–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENQUET P., GEE C.E., GERBER U. Two distinct signaling pathways upregulate NMDA receptor responses via two distinct metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes. J. Neurosci. 2002;12:9679–9686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09679.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINNS K.E., SALT T.E. Excitatory amino acid receptors participate in synaptic transmission of visual responses in the superficial layers of the cat superior colliculus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINNS K.E., SALT T.E. Different roles for GABAA and GABAB receptors in visual processing in the rat superior colliculus. J. Physiol. 1997;504:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.629bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINNS K.E., SALT T.E. Excitatory amino acid receptors modulate habituation of the response to visual stimulation in the cat superior colliculus. Vis. Neurosci. 1995;12:563–571. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRONE J., POTHECARY C.A., TURNER J.P., SALT T.E. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) modulate visual responses in the superficial superior colliculus of the rat. J. Physiol. 2002a;541:895–903. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.016618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRONE J., SALT T.E. Physiological role of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in visually responsive neurones of the rat superficial superior colliculus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:847–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRONE J., SALT T.E. Group II and III metabotropic glutamate receptors contribute to different aspects of visual response processing in the rat superior colliculus. J. Physiol. 2001;534:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRONE J., SHARP C., JEFFERY G., SALT T.E. Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the superior colliculus of the adult rat, ferret and cat. Neuroscience. 2002b;109:779–786. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOHERTY A.J., PALMER M.J., HENLEY J.M., COLLINGRIDGE G.L., JANE D.E. (RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG) activates mGlu5, but not mGlu1, receptors expressed in CHO cells and potentiates NMDA responses in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:265–267. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREHER R., SEFTON A.J., NI S.Y.K., NISBETT G. The morphology, number, distribution and central projections of class I retinal ganglion cells in albino and hooded rats. Brain Behav. Evol. 1985;26:10–48. doi: 10.1159/000118764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGNI L., CHAVIS P., ANGO F., BOCKAERT J. Complex interactions between mGluRs, intracellular Ca2+ stores and ion channels in neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:80–100. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOTUHI M., SHARP A.H., GLATT C.E., HWANG P.M., VON KROSIGK M., SNYDER S.H., DAWSON T.M. Differential localization of phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:2001–2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02001.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEREAU R.W., CONN P.J. Multiple presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal area CA1. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6879–6889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLAUM S.R., MILLER R.J. Presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate ω-conotoxin-GIVA-insensitive calcium channels in the rat medulla. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:953–964. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00076-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARVEY J., PALMER M.J., IRVING A.J., CLARKE V.R, COLLINGRIDGE G.L. NMDA receptor dependence of mGlu-mediated depression of synaptic transmission in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:1239–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERRERO I., MIRAS-PORTUGAL M.T., SANCHEZ-PRIETO J. Activation of protein kinase C by phorbol esters and arachidonic acid are required for the optimal potentiation of glutamate exocytosis. J. Neurochem. 1998;59:1574–1577. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEUSS C., GERBER U. G protein-independent signalling by G-protein coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRELAND D.R., ABRAHAM W.C. Group I mGluRs increase excitability of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by a PLC-independent mechanism. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:107–116. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUJÁN R., NUSSER Z., ROBERTS J.D.B., SHIGEMOTO R., SOMOGYI P. Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8:1488–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNAIONI G., MARINO M.J., VALENTI O., TRAYNELIS S.F., CONN P.J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5 differentially regulate CA1 pyramidal cell function. J Neurosci. 2001;16:5925–5934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05925.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZONI O., BOCKAERT J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibit excitatory synapses in the CA1 area of rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7:2518–2523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOULT P.R., SCHNABEL R., KILPATRICK I.C., BASHIR Z.I., COLLINGRIDGE G.L. Tyrosine dephosphorylation underlies DHPG-induced LTD. Neuropharmacol. 2002;43:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUTEL V., ELLIS G.J., ADAM G., CHABOZ S., NILLY A., MESSER J., BLEUEL Z., METZLER V., MALHERBE P., SCHLAEGER E.-J., ROUGHLEY B.S., FAULL R.L.M., RICHARDS J.G. Characterization of [3 H]Quisqualate binding to recombinant rat metabotropic glutamate 1a and 5a receptors and to rat and human brain sections. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:2590–2601. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NETZEBAND J.G., PARSON K.L., SWEENEY D.D., GRUOL D.L. Metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists alter neuronal excitability and Ca2+ levels via the phospholipase C transduction pathway in cultured Purkinje neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:63–75. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALMER M.J., IRVING A.J., SEABROOK G.R., JANE D.E., COLLINGRIDGE G.L. The group I receptor agonist DHPG induces a novel form of LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1517–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIN J.-P., DUVOISIN R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and function. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLATT B., WITHINGTON D.J. Paired-pulse depression in the superficial layers of the guinea-pig superior colliculus. Brain Res. 1997;777:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLATT B., WITHINGTON D.J. GABA-induced long-term potentiation in the guinea-pig superior colliculus. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POTHECARY C.A., JANE D.E., SALT T.E. Reduction of excitatory transmission in the retino-collicular pathway via selective activation of mGluR8 receptors by DCPG. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAE M.G., MARTIN D.J., COLLINGRIDGE G.L., IRVING A.J. Role of Ca2+ stores in metabotropic L-glutamate receptor mediated supralinear Ca2+ signaling in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8628–8636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08628.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REID M.E., TOMS N.J., BEDINGFIELD J.S., ROBERTS P.J. Group I mGlu receptors potentiate synaptosomal [3H]glutamate release independently of exogenously applied arachidonic acid. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODRÍGUEZ-MORENO A., SISTIAGA A., LERMA J., SÁNCHEZ-PRIETO J. Switch from facilitation to inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission by group I mGluR desensitization. Neuron. 1998;21:1477–1486. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMANO C., SESMA M.A., MCDONALD C.T., O'MALLEY K., VAN DEN POL A.N., OLNEY J.W. Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 immunoreactivity in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;355:455–469. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAYER R.J. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate slow inhibition of calcium current in neocortical neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1981–1988. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCANZIANI M., SALIN P.A., VOGT K.E., MALENKA R.C., NICOLL R.A. Use-dependent increase in glutamate concentration activate presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;385:630–634. doi: 10.1038/385630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOEPP D.D., JANE D.E., MONN J.A. Pharmacological agents acting at subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1431–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIGEMOTO R., MIZUNO N. Metabotropic glutamate receptors–immunocytochemical and in situ hybridisation analyses. Handb Chem. Neuroanat. 2000;18:63–98. [Google Scholar]

- STEIN B.E., MEREDITH M.A. The Merging of the Senses. Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.: MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- SWARTZ K.J., BEAN B.P. Inhibition of calcium channels in rat CA3 pyramidal neurons by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. J. Neurosci. 1992;21:4358–4371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04358.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALENTI O., CONN P.J., MARINO M.J. Distinct physiological roles of the Gq-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors co-expressed in the same neuronal populations. J. Cell Physiol. 2002;191:125–137. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITTMANN M., HUBERT G.W., SMITH Y., CONN P.J. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 inhibits glutamatergic transmission in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. Neuroscience. 2001;105:881–889. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU R.-L., BARISH M.E. Modulation of a slowly inactivating potassium current, ID, by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6825–6837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06825.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]