Abstract

Both clinical and preclinical models of postsurgical pain are being used more frequently in the early evaluation of new chemical entities. In order to assess the validity and reliability of a rat model of postincisional pain, the effects of different classes of clinically effective analgesic drugs were evaluated against multiple behavioural end points.

Following surgical incision, under general anaesthesia, of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw, we determined the time course of mechanical hyperalgesia, tactile allodynia and hind limb weight bearing using the Randall–Selitto (paw pressure) assay, electronic von Frey and dual channel weight averager, respectively. Behavioural evaluations began 24 h following surgery, and were continued for 9–14 days.

Mechanical hyperalgesia, tactile allodynia and a decrease in weight bearing were present on the affected limb within 1 day of surgery with maximum sensitivity 1–3 days postsurgery. Accordingly, we examined the effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), morphine and gabapentin, on established hyperalgesia and allodynia, 1 day following plantar incision.

In accordance with previous reports, both systemic morphine and gabapentin administration reversed mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia in the incised rat hind paw. Both drugs were more potent against mechanical hyperalgesia than tactile allodynia.

All of the NSAIDs tested, including cyclooxygenase 2 selective inhibitors, reversed mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia in the incised rat hind paw. The rank order of potency for both hyperalgesia and allodynia was indomethacin > celecoxib > etoricoxib > naproxen.

We have investigated the potency and efficacy of different classes of analgesic drugs in a rat model of postincisional pain. The rank order of potency for these drugs reflects their utility in treating postoperative pain in the clinic. As these compounds showed reliable efficacy across two different behavioural end points, the Randall–Selitto (paw pressure) assay and electronic von Frey, these methods may prove useful in the study of postsurgical pain and the assessment of novel treatments.

Keywords: Incisional pain, hyperalgesia, allodynia, NSAID, COX, gabapentin

Introduction

One out of every two patients suffers intense or very intense pain during the first few days postsurgery (Chauvin, 1999). In addition to this significant therapeutic problem, clinical and preclinical models of postsurgical or postincisonal pain are becoming increasingly important for the investigation of the pathophysiological mechanisms of persistent pain (Zahn & Brennan, 1998; Yamamoto & Sakashita, 1999; Zahn & Brennan, 1999a, 1999b; Li & Clark, 2000; Vandermeulen & Brennan, 2000; Kozubenko et al., 2001; Tsuda et al., 2001; Zahn et al., 2002; Pogatzki et al., 2002a, 2002c, 2002d,), and for the evaluation of novel analgesic therapeutics (Field et al., 1997; 1999; Gonzalez et al., 1998; Chiari & Eisenach, 1999; Brennan & Zahn, 2000; Jain, 2000; Song et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Yamamoto et al., 2000; Girard et al., 2001; Hord et al., 2001; Brennan, 2002; Jarvis et al., 2002; Kroin et al., 2002; Omote et al., 2002; Prado & Machado, 2002; Prado et al., 2002). This model has also driven investigation into the pharmacological mechanisms of pre-emptive analgesia, by comparing the effects of the administration of compounds before or during surgery (Brennan et al., 1997; Gonzalez et al., 1998; Ronn et al., 2000; Prado & Pontes, 2002; Pogatzki et al., 2002d; Redua et al., 2002) with administration immediately following surgery. However, variations in treatment regimes has led to subsequent difficulty in comparing between studies, and has made it difficult to follow a consistent pharmacological profile for different classes of drugs in this model.

In his original publications, (Brennan et al., 1996), describe a model of postsurgical pain involving a 1 cm incision of the skin and muscle of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw. Following plantar incision, rats show decreases in response thresholds to graded von Frey filaments, and decreases in weight bearing in the effected limb for several days (Brennan et al., 1996). In the present study, we have compared the effects of different classes of analgesics on established hypersensitivity due to an incision of the rat hind paw. To this end, we have performed a timecourse of hyperalgesia, allodynia and weight bearing following plantar incision, and determined the timepoint when mechanical hypersensitivity was maximal and stable. The effects of morphine, gabapentin, etoricoxib, celecoxib, indomethacin and naproxen were evaluated due to their common prescription for moderate to severe pain associated with injury or inflammation in the clinic. To assess the reliability of the efficacy and potency of these compounds, we have utilized three different behavioural assays, two of which have not been previously described in this model: tactile allodynia using an automated electronic von Frey (IITC, CA, U.S.A.)(Cairns et al., 2002) and mechanical hyperalgesia using the Randall–Selitto (paw pressure) assay (Randall & Selitto, 1957). Hind paw weight bearing was also measured, as described previously (Brennan et al., 1996; Clayton et al., 2002). Von Frey utilises a non-noxious stimulus, and is therefore considered to measure tactile allodynia, while the Randall–Selitto assay utilizes a noxious stimuli and is considered to measure mechanical hyperalgesia (Hogan, 2002).

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by an institutional animal care and use committee, and this study was conducted in accordance with the International Association for the study of pain guidelines on the use of animals in experimental research Zimmerman, 1983. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–200 g; Taconic, NY, U.S.A.), 8–10 per group, were used in all experiments. Animals were housed in groups of three, and had free access to food and water at all times except prior to oral administration of drugs when food was removed 12 h before and returned 5 h after dosing. Animals were on a 12 h light–dark cycle.

Surgery

Surgery was performed as previously described (Brennan et al., 1996), with minor modifications. Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with 2% isofluorane and the plantar surface of the left hind paw prepared in a sterile manner. A 1 cm longitudinal incision was made with a number 10 scalpel, through skin and fascia of the plantar aspect of the paw, starting 0.5 cm from the proximal edge of the heel and extending toward the toes. The plantaris muscle was elevated and incised longitudinally. Following haemostasis with gentle pressure, the skin was opposed with two single interrupted sutures using 5–0 nylon. The wound site was covered with povidone–iodine anti–biotic powder (PRN Pharmacal, Pensacola, FL, U.S.A.) and the animals allowed to recover in their home cages.

Behavioural testing

Mechanical hyperalgesia was measured as the hind paw withdrawal, threshold to a noxious mechanical stimulus (PPWT), and was determined using the paw pressure technique (Randall & Selitto, 1957). The analgesymeter (7200, Ugo Basile, Italy) employed a rounded probe, cutoff was set at 250 g and the end point was taken as paw withdrawal.

To assess tactile allodynia, paw withdrawal threshold to a non-noxious tactile stimulus (VFWT) was determined using an automated electronic von Frey (IITC, CA, U.S.A.). The electronic von Frey employs a single nonflexible filament to which the experimenter applies an increasing force. A force above 50 g was considered to be a noxious stimuli, as this elicited a response in naïve animals. The stimulus was applied to site 2 of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw, as previously described. The end point was taken as nocifensive paw withdrawal, and three thresholds were taken per test and averaged.

Hind limb weight bearing was assessed using an incapacitance meter (Stoelting, CA, U.S.A.) that independently measures the weight that the animal distributes to each hind paw. Nontreated animals distribute their weight equally on both hind paws, while a unilateral intraplantar administration of Freud's complete adjuvant (FCA) causes the animals to favour the noninjected limb (Clayton et al., 2002). The equipment was set to average the weight over 3 s, three measurements were taken and the mean percentage weight borne on the affected limb expressed.

To determine the time course of hyperalgesia, allodynia and weight bearing, a baseline measurement was made prior to surgery, and then again at 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9 and 14 days postsurgery for hyperalgesia, 1, 2, 3, 7 and 9 days postsurgery for allodynia, or 1, 3, 7 and 14 days postsurgery for weight bearing (in separate groups of rats).

Based on these time-course results, all compounds were tested 24 h following plantar incision (in separate groups of rats). Measurements (PPWT and VFWT only) were determined prior to surgery, and then again 24 h postincision (predrug). Immediately following the predrug test, compounds were administered and further measurements were taken at 1, 3, 5 and 24 h (postdrug). For comparison with compound-treated groups, incised animals treated with the appropriate vehicle were included in each experiment, as were vehicle-treated, nonincised control rats.

Drugs and reagents

Morphine sulphate (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.) was administered subcutaneously (s.c., 2 ml kg−1) in 0.9% saline. Gabapentin (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p., 2 ml kg−1) in 0.9% saline. Celecoxib (Toronto Research Chemicals, Canada), naproxen (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.), indomethacin (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.) and etoricoxib (Riendeau et al., 2001) (synthesized at Purdue Pharma LP, NJ, U.S.A.) were administered orally by gastric gavage (p.o., 10 ml kg−1) in 0.5% methylcellulose.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed on the untransformed thresholds for both electronic von Frey and paw pressure, and on the % weight borne on the injured limb for weight bearing. Data were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher PLSD post hoc analysis, with P⩽0.05 considered statistically significant as compared to vehicle-treated controls. Percent reversal of hyperalgesia for each animal was defined as

Data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The dose that produces 50% of the maximum percent reversal (ED50) was calculated using the curve-fitting functions in Graphpad PRISM, v. 3.0.

Results

Time course of mechanical hyperalgesia, tactile allodynia and hind limb weight bearing

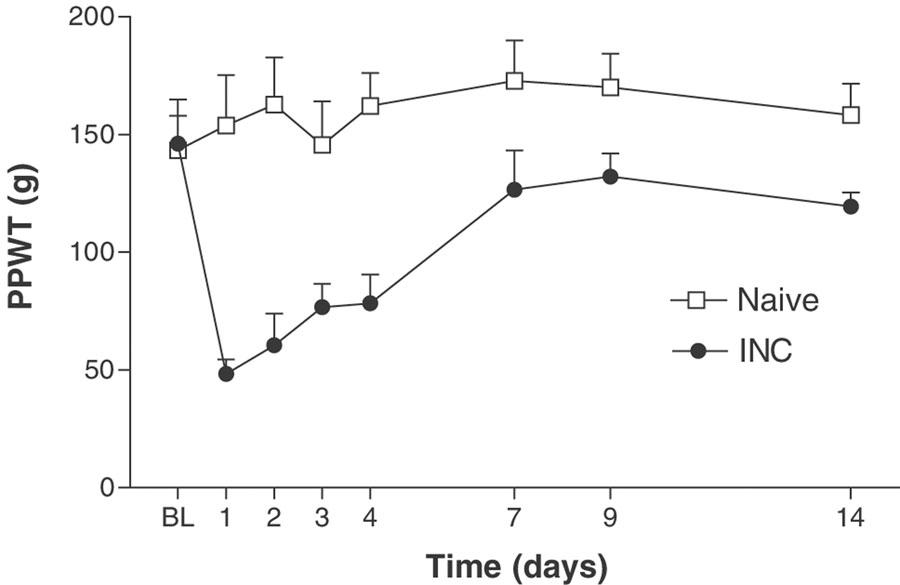

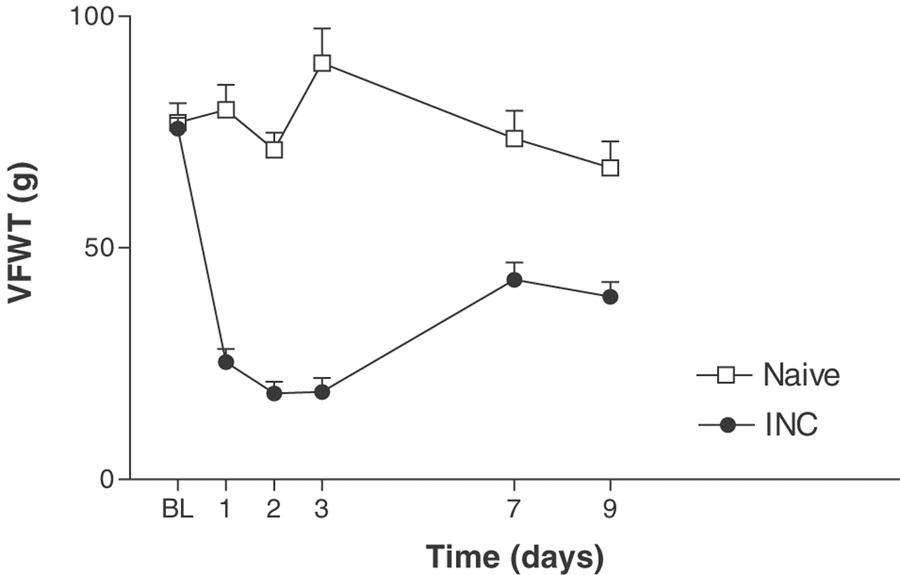

Incision of the plantar surface of the hind paw produced a significant reduction in PPWT and VFWT, as measured using both the paw pressure (mechanical hyperalgesia; Figure 1) and the electronic von Frey assays (tactile allodynia; Figure 2) at all time points studied up to 14 or 9 days, respectively (the latest time points studied). The reduction in PPWT for the paw pressure assay was maximal 1 day postincision (48.3±6.2 g), as compared to baseline (146.1±18.8 g) and naïve controls (143.3±14.7 g). The reduction in VFWT for the electronic von Frey assay was maximal 1–3 day's postincision (18.6±2.6–25.3±2.8 g) as compared to baseline (75.7±2.4 g) and naïve controls (71.2±3.8–89.9±7.5 g).

Figure 1.

Time course of mechanical hyperalgesia, measured by Randall and Selitto analgesymeter, following incision of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw. A significant mechanical hyperalgesia was present at all postsurgical test time points. BL–baseline, INC–incisional group, PWT–paw-withdrawal threshold. Values represent mean±s.e.m., n=8–10 per group. P<0.05 as compared to naïve rats.

Figure 2.

Time course of tactile allodynia, measured by electronic von Frey, following incision of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw. A significant tactile allodynia was present at all postsurgical time points. BL–baseline, INC–incisional group, PWT–paw withdrawal threshold. Values represent mean±s.e.m., n=8–10 per group. P<0.05 as compared to naïve rats.

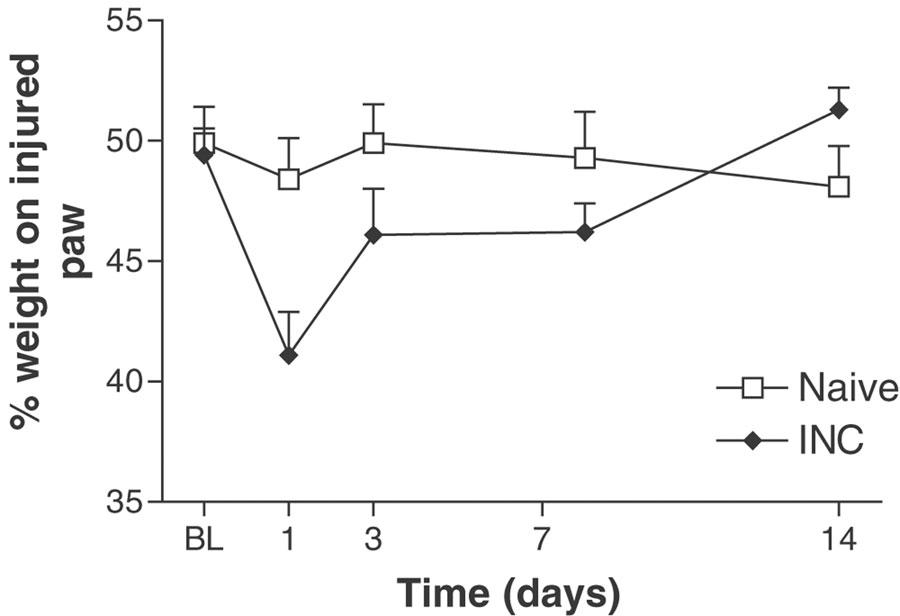

Incision of the plantar surface of the hind paw produced a significant reduction in weight borne on the injured limb 1 and 3 days post–surgery (Figure 3). The reduction in weight bearing was maximal 1 day post–incision (41.1±1.8%), as compared to baseline (49.4±1.1%) and naïve controls (48.4±1.7%).

Figure 3.

Time course of weight bearing, measured by an incapacitance meter, following incision of the plantar surface of the rat hind paw. A significant decrease in weight bearing on the injured limb was present 1 day postsurgery. BL–baseline, INC–incisional group. Values represent mean±s.e.m., n=8–10 per group. P<0.05 as compared to naïve rats.

Action of compounds on mechanical hyperalgesia

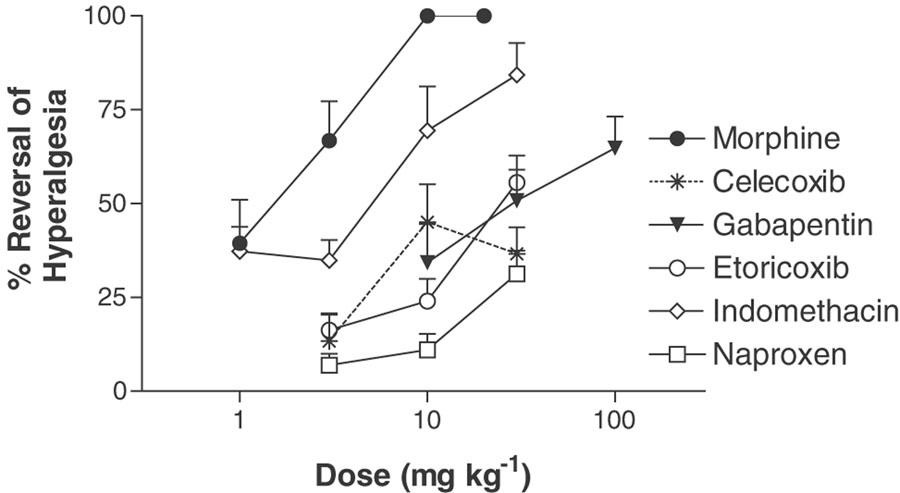

The results are summarized in Table 1. All rats displayed predrug PPWT 24 h following administration of each drug tested. Morphine (1–20 mg kg−1, s.c.) produced a dose-dependent reversal of mechanical hyperalgesia when tested 1 day following plantar incision (Figure 4 and Table 1). Morphine produced a maximal reversal (100%; 10–20 mg kg−1) 1 h post administration (PPWT=250.0±0.0 g at 20 mg kg−1 compared to 72.0±6.7 g for vehicle-treated animals); however sedation was noted in all animals treated with the 10 and 20 mg kg−1dose of morphine. The duration of the antihyperalgesic effect of morphine was short, with only the highest dose (20 mg kg−1) causing significant antihyperalgesia when tested 5 h following administration (data not shown).

Table 1.

Summary of the action of a number of analgesic compounds against mechanical hyperalgesia (a) and tactile allodynia (b) in a rat model of incisional pain

| Compound | Doses (mg kg−1) | Route | MED (mg kg−1) | Onset of action | Duration of action | Maximum percent reversal | ED50 (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Paw pressure | |||||||

| Morphine | 1, 3, 10, 20 | s.c. | 3 | By 1 h | Short | 100 % (1 h) | 1.9 |

| Gabapentin | 10, 30, 100 | i.p. | 30 | By 1 h | Medium | 64% (1 h) | 11.3 |

| Indomethacin | 1, 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 1 h | Medium | 84 % (1 h) | 2.8 |

| Naproxen | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 30 | By 1 h | Long | 31% (3 h) | 93 |

| Celecoxib | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 1 h | Medium | 45% (1 h) | 4.1 |

| Etoricoxib | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 1 h | Long | 56% (3 h) | 28.8 |

| (b) Electronic von Frey | |||||||

| Morphine | 1, 3, 10, 20 | s.c. | 1 | By 1 h | Short | 100% (1 h) | 0.81 |

| Gabapentin | 10, 30, 100 | i.p. | 30 | By 3 h | Short | 19% (3 h) | 3.4 |

| Indomethacin | 1, 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 3 h | Short | 46% (5 h) | 7.1 |

| Naproxen | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 30 | By 3 h | Medium | 43% (3 h) | 20.2 |

| Celecoxib | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 3 h | Medium | 47% (3 h) | 8.9 |

| Etoricoxib | 3, 10, 30 | p.o. | 10 | By 1 h | Long | 70% (3 h) | 10.1 |

MED is defined as the minimum dose that elicits a statistically significant reversal as compared to vehicle-treated controls. Onset of action is defined as the earliest detected statistically significant reversal with the MED. Duration of action is defined as short – the MED elicited a statistically significant reversal at only one of the time points postadministration, medium – the MED elicited a statistically significant reversal at two of the time points postadministration, long – the MED elicited a statistically significant reversal at three of the time points postadministration. Maximum percent reversal is reported for the highest dose studied. ED50 is defined as the dose which produces 50% of its maximum effect. s.c. – subcutaneous, i.p. – intraperitoneal, p.o. – oral gavage, MED – minimum effective dose.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the effects of morphine (1–20 mg kg−1, s.c.), celecoxib (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.), gabapentin (10–100 mg kg−1, i.p.), etoricoxib (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.), indomethacin (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) and naproxen (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) on reversal of incision-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in the incised rat hind paw following a single dose (n=8–10 per group). Data (mean PWT±s.e.m.,) are presented at the time of maximal reversal for each compound. Sedation was observed in all rats following treatment with morphine (10 and 20 mg kg−1, s.c.).

Gabapentin (10–100 mg kg−1, i.p.) produced a maximum reversal of 64% (100 mg kg−1; Figure 4 and Table 1) 3 h following administration (PPWT=128.5±15.4 g at 100 mg kg−1 compared to 67.0±5.3 g for vehicle-treated animals). There was no effect of gabapentin on rat PPWT when tested 5 h following administration (data not shown).

Indomethacin (1–30 mg kg−1 p.o.) and celecoxib (3–30 mg kg−1; p.o.) produced a maximum reversal of 84% (30 mg kg−1) and 45% (30 mg kg−1), respectively (Figure 4 and Table 1), 1–3 h following administration (indomethacin PPWT=145.5±19.2 g at 30 mg kg−1 compared to 80.0±15.9 g for vehicle-treated animals; celecoxib PPWT=71.7±6.4 g at 30 mg kg−1 as compared to 37.2±8.0 g for vehicle-treated animals). Neither indomethacin nor celecoxib was effective in reversing mechanical hyperalgesia when tested 5 h following administration (data not shown). Naproxen and etoricoxib (both 3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) produced a maximum reversal of 31 and 56% (both 30 mg kg−1), respectively (Figure 4 and Table 1) (naproxen PPWT=75.0±9.1 g at 30 mg kg−1 compared to 42.7±8.4 g for vehicle treated animals; etoricoxib PPWT=104.7±6.5 g at 30 mg kg−1 as compared to 49.5±5.7 g for vehicle-treated animals). Rats treated with either naproxen or etoricoxib displayed significant antihyperalgesia at the 1, 3 and 5 h tests following administration. Based on ED50 (Table 1), the rank order of potency is indomethacin > celecoxib > etoricoxib > naproxen.

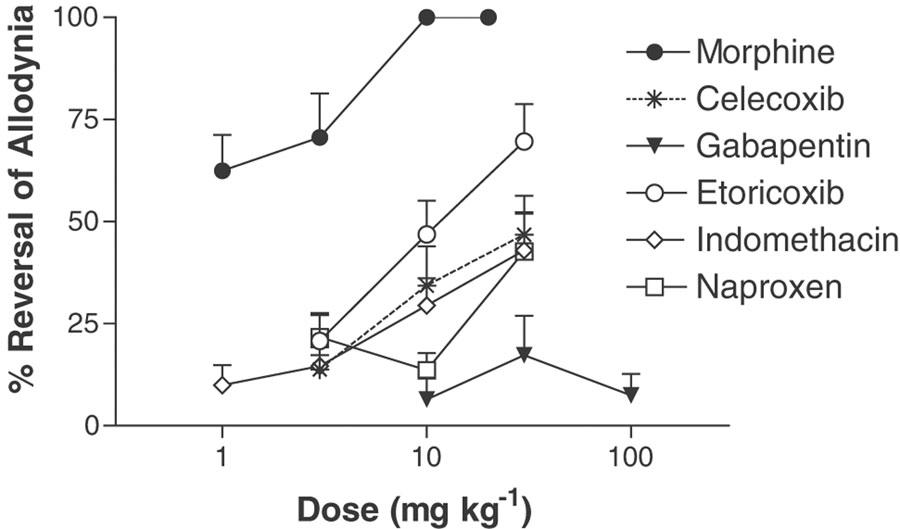

Action of compounds on tactile allodynia

The results are summarized in Table 1. All rats displayed predrug VFWT 24 h following administration of each drug tested. The actions of morphine against tactile allodynia were similar to its actions against mechanical hyperalgesia. Morphine (1–20 mg kg−1, s.c.) produced a complete reversal (10–20 mg kg−1) of tactile allodynia when tested 24 h following plantar incision; however, sedation was noted at the two highest doses (Figure 5 and Table 1) (VFWT=82.6±5.6 g at 20 mg kg−1 compared to 22.9±2.2 g for vehicle-treated animals). Only the highest dose of morphine was effective when tested 3 h following administration (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the effects of morphine (1–20 mg kg−1, s.c.), celecoxib (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.), gabapentin (10–100 mg kg−1, i.p.), etoricoxib (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.), indomethacin (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) and naproxen (3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) on reversal of incision induced tactile allodynia in the incised rat hind paw, following a single dose (n=8–10 per group). Data (mean PWT±s.e.m.,) are presented at the time of maximal reversal for each compound. Sedation was observed in all rats following treatment with morphine (10 and 20 mg kg−1, s.c.).

Gabapentin (10–100 mg kg−1, i.p.) produced a maximum reversal of 19% 3 h following administration (Figure 5 and Table 1), but was ineffective at the 1 and 5 h tests (data not shown) (VFWT=25.0±2.2 g at 100 mg kg−1 compared to 18.3±1.8 g for vehicle-treated animals).

Indomethacin (1–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) produced a maximum reversal of 46% (30 mg kg−1) 3 h following administration (Figure 5 and Table 1) (indomethacin VFWT=36.7±2.9 g at 30 mg kg−1 compared to 23.6±3.1 g for vehicle-treated animals). In contrast to its effects on mechanical hyperalgesia, the effects of indomethacin on mechanical allodynia were only observed at the 3 h test (Figure 4). Naproxen, celecoxib and etoricoxib (all 3–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) produced a maximum reversal of 43, 47 and 70%, respectively (Figure 4 and Table 1) (naproxen VFWT=42.9±3.0 g at 30 mg kg−1 compared to 27.0±3.2 g for vehicle treated animals; celecoxib VFWT=39.0±3.7 g at 30 mg kg−1 as compared to 26.4±3.7 g for vehicle treated animals; etoricoxib VFWT=52.9±4.4 g at 30 mg kg−1 as compared to 24.2±2.4 g for vehicle-treated animals). Naproxen and celecoxib were effective when tested 3 and 5 h following administration, but etoricoxib displayed the longest duration of effect with significant reversal of mechanical allodynia at the 1, 3 and 5 h tests. Based on ED50 (Table 1), the rank order of potency is indomethacin > celecoxib > etoricoxib > naproxen.

Action of compounds on weight bearing

Although a significant decrease in the weight bearing was observed (as described above), it was too modest to permit quantification of the pharmacological action of compounds.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that a reliable and quantifiable mechanical hyperalgesia, tactile allodynia and decrease in weight bearing, as measured by Randall–Selitto (paw pressure) assay, electronic von Frey and incapacitance meter, respectively, develop in a rat model of postsurgical pain. This is the first description of the use of these behavioural end points in this model. The time course of hypersensitivity is in accordance with previous reports using alternative behavioural measurements (Brennan et al., 1996). We found that mechanical hyperalgesia, tactile allodynia and decrease in weight bearing were maximal 1–3 days postincision and resolved over similar time courses. Although a significant decrease in the weight bearing was observed, it was too modest to permit quantification of the action of compounds.

Investigation of the potency and efficacy of test compounds on mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia was undertaken 1 day postincision. This time point allowed the assessment of the action of analgesics on an established pain state, and removed the possibility that treatment during surgery or in the immediate postsurgical period could alter the development of behavioural hypersensitivity. We have demonstrated that both mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia can be reversed by a number of different classes of analgesic drugs.

All of the compounds that we tested significantly reversed mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia, as compared to vehicle-treated controls. The effects are dose dependent with the greatest effects being observed at the greatest doses. Morphine has been previously shown to reduce pain behaviours in a rat model of incisional pain when administered pre-or postsurgically via an intrathecal (Brennan et al., 1997; Pogatzki et al., 2002b), s.c. (Field et al., 1997; Zahn et al., 1997; Ronn et al., 2000) or i.p. route (Wang et al., 2000). The effective dose of morphine is often observed to be in the range that causes sedation. The effects of gabapentin have also been previously described in this model; when administered subcutaneously prior to surgery, it can prevent the development of both thermal hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia (Field et al., 1997). In addition, intrathecal gabapentin has been shown to be antiallodynic when administered 4 h following surgery (Cheng et al., 2000).

Four recent studies have investigated the action of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors on plantar incision-induced pain. Three of these (Yamamoto & Sakashita, 1999; Kroin et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2003) demonstrated that postsurgical intrathecal administration of COX2 inhibitors have no effect on incision–induced pain behaviours. In contrast to these, the fourth study (Yamamoto et al., 2000) showed that oral administration of indomethacin or a selective COX2 inhibitor (JTE522) 5 min following plantar incision can reduce tactile allodynia, as assessed with von Frey filaments. We are unaware of any reports of the efficacy of celecoxib, naproxen or etoricoxib in this rat model; however, flunixin, a potent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), when given subcutaneously in the immediate postsurgical period and daily thereafter, produced an antiallodynic effect (Stewart & Martin, 2003).

In our experiments, all NSAIDs tested effectively reversed incision-induced decreases in PPWT and VFWT with the relative order of potency being indomethacin > celecoxib > etoricoxib > naproxen against both mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia. This in vivo rank order of potency is in accordance with the compounds' respective in vitro potencies at human COX2 (Warner et al., 1999; Riendeau et al., 2001). These results are in agreement with those of Yamamoto et al. (2000) and Stewart & Martin (2003) in demonstrating that systemically administered NSAIDs and selective COX2 inhibitors are effective in a rat model of incisional pain.

In the present study, both morphine and gabapentin were efficacious in reversing mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia, thus confirming and extending previous reports. Interestingly, gabapentin was more efficacious against mechanical hyperalgesia than tactile allodynia. It has been proposed that mechanical hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia are mediated by a distinct population of neurons (Woolf et al., 1992). The increased efficacy of gabapentin against mechanical hyperalgesia may be due to a preferential effect on the population of neurons responsible for this hypersensitivity.

The pharmacology of the plantar incision model of postoperative pain is distinct from that of inflammatory and neuropathic pain models. NSAIDs are effective in animal models of inflammatory pain, while gabapentin is effective in animal models of neuropathic pain. The partial efficacy of both NSAIDs and gabapentin in the incisional pain model suggests that both inflammatory and neuropathic mechanisms contribute to the hyperalgesia and allodynia that is observed. An investigation of the changes in mRNA and protein expression in the dorsal root ganglia peripheral terminals and dorsal horn of the spinal cord following incision and comparison to changes in inflammatory and neuropathic pain states would allow further investigation of this hypothesis.

In summary, we have investigated the potency and efficacy of different classes of analgesic drugs in a rat model of postincisional pain. The rank order of potency for these drugs reflects their utility in treating postoperative pain in the clinic. As the Randall–Selitto (paw pressure) assay and electronic von Frey show consistent time–course relationships and pharmacological profiles as previously described behavioural measurements, these methods should prove useful in the study of postsurgical pain and the assessment of novel treatments.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dan Waligora (Amgen, CA) and Morgan Woods (Purdue, NJ) for technical assistance with surgeries, and Jeff Mara (Purdue, NJ) for assistance with drug compounds.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- ED50

The dose that produces 50% of the maximum percent reversal

- FCA

Freud's complete adjuvant

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- p.o.

oral administration by gastric gavage

- PPWT

paw withdrawal threshold to a noxious mechanical stimulus

- s.c.

subcutaneously

- s.e.m.

standard error of the mean

- VFWT

paw-withdrawal threshold to a non-noxious tactile stimulus

References

- BRENNAN T.J. Frontiers in translational research – the etiology of incisional and postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:535–537. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN T.J., UMALI E.F., ZAHN P.K. Comparison of pre- versus post-incision administration of intrathecal bupivacaine and intrathecal morphine in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1517–1528. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN T.J., VANDERMEULEN E.P., GEBHART G.F. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN T.J., ZAHN P.K. Effect of intrathecal ACEA-1021 in a rat model for postoperative pain. J. Pain. 2000;1:279–284. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2000.8921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAIRNS B.E., GAMBAROTA G., SVENSSON P., ARENDT-NIELSEN L., BERDE C.B. Glutamate-induced sensitization of rat masseter muscle fibers. Neuroscience. 2002;109:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAUVIN M. Relieving post-operative pain. Presse Med. 1999;28:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG J.K., PAN H.L., EISENACH J.C. Antiallodynic effect of intrathecal gabapentin and its interaction with clonidine in a pat model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1126–1131. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIARI A.I., EISENACH J.C. intrathecal adenosine – interactions with spinal clonidine and neostigmine in rat models of acute nociception and postoperative hypersensitivity. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1413–1421. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLAYTON N., MARSHALL F.H., BOUNTRA C., O'SHAUGHNESSY C.T. CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors are implicated in inflammatory pain. Pain. 2002;96:253–260. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIELD M.J., CARNELL A.J., GONZALEZ M.I., MCCLEARY S., OLES R.J., SMITH R., HUGHES J., SINGH L. Enadoline, a selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist shows potent antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic actions in a rat model of surgical pain. Pain. 1999;80:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIELD M.J., HOLLOMAN E.F., MCCLEARY S., HUGHES J., SINGH L. Evaluation of gabapentin and S-(+)-3-isobutylgaba in a rat model of postoperative pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;282:1242–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIRARD P., PANSART Y., COPPE M.C., GILLARDIN J.M. Nefopam reduces thermal hypersensitivity in acute and postoperative pain models in the rat. Pharmacol. Res. 2001;44:541–545. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ M., FIELD M.J., HOLLOMAN E.F., HUGHES J., OLES R.J., SINGH L. Evaluation of PD154075, a tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist, in a rat model of postoperative pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;344:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGAN Q. Animal pain models. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2002;27:385–401. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.33630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORD A.H., DENSON D.D., AZEVEDO M.I. Systemic tizanidine hydrochloride (Zanaflex (TM)) partially decreases experimental postoperative pain in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2001;93:1307–1309. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAIN K.K. An evaluation of intrathecal ziconotide for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2000;9:2403–2410. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.10.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARVIS M.F., BURGARD E.C., MCGARAUGHTY S., HONORE P., LYNCH K., BRENNAN T.J., SUBIETA A., VAN BIESEN T., CARTMELL J., BIANCHI B., NIFORATOS W., KAGE K., YU H.X., MIKUSA J., WISMER C.T., ZHU C.Z., CHU K., LEE C.H., STEWART A.O., POLAKOWSKI J., COX B.F., KOWALUK E., WILLIAMS M., SULLIVAN J., FALTYNEK C. A-317491, a novel potent and selective nonnucleotide antagonist of P2X(3) and P2X(2/3) receptors, reduces chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:17179–17184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252537299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOZUBENKO N.V., KOBELIATSKY Y.Y., USHAKOVA G.A. Changes in the expression of astroglial proteins under conditions of postoperation hyperalgesia. Neurophysiology. 2001;33:344–348. [Google Scholar]

- KROIN J.S., BUVANENDRAN A., MCCARTHY R.J., HEMMATI H., TUMAN K.J. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition potentiates morphine antinociception at the spinal level in a postoperative pain model. Regional Anesth. Pain Med. 2002;27:451–455. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.35521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI X.Q., CLARK J.D. The role of heme oxygenase in neuropathic and incisional pain. Anesth. Analg. 2000;90:677–682. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMOTE K., YAMAMOTO H., KAWAMATA T., NAKAYAMA Y., NAMIKI A. The effects of intrathecal administration of an antagonist for prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP1 on mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesth. Analg. 2002;95:1708–1712. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POGATZKI E.M., GEBHART G.F., BRENNAN T.J. Characterization of A delta- and C-fibers innervating the plantar rat hindpaw one day after an incision. J. Neurophysiol. 2002a;87:721–731. doi: 10.1152/jn.00208.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POGATZKI E.M., NIEMEIER J.S., BRENNAN T.J. Persistent secondary hyperalgesia after gastrocnemius incision in the rat. Eur. J. Pain. 2002b;6:295–305. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2002.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POGATZKI E.M., URBAN M.O., BRENNAN T.J., GEBHART G.F. Role of the rostral medial medulla in the development of primary and secondary hyperalgesia after incision in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2002c;96:1153–1160. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POGATZKI E.M., VANDERMEULEN E.P., BRENNAN T.J. Effect of plantar local anesthetic injection on dorsal horn neuron activity and pain behaviors caused by incision. Pain. 2002d;97:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRADO W.A., MACHADO E.B. Antinociceptive potency of aminoglycoside antibiotics and magnesium chloride: a comparative study on models of phasic and incisional pain in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002;35:395–403. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRADO W.A., PONTES R.M.C. Presurgical ketoprofen, but not morphine, dipyrone, diclofenac or tenoxicam, preempts post-incisional mechanical allodynia in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002;35:111–119. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRADO W.A., SCHIAVON V.F., CUNHA F.Q. Dual effect of local application of nitric oxide donors in a model of incision pain in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;441:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANDALL L.O., SELITTO J.J. A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed tissue. Arch. Int. Pharmacodynam. 1957;3:409–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDUA M.A., VALADAO C.A.A., DUQUE J.C., BALESTRERO L.T. The pre-emptive effect of epidural ketamine on wound sensitivity in horses tested by using von Frey filaments. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2002;29:200–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2995.2002.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIENDEAU D., PERCIVAL M.D., BRIDEAU C., CHARLESON S., DUBE D., ETHIER D., FALGURYRET J.-P., FRIESEN R.W., GORDON R., GREIG G., GUAY J., MANCINI J., OUELLET M., WONG E., XU L., BOYCE S., VISCO D., GIRARD Y., PRASIT P., ZAMBONI R., RODGER W., GRESSER M., FORD-HUTCHINSON A.W., YOUNG R.N., CHAN C.-C. Etoricoxib (MK-0663): Preclinical profile and comparison with other agents that selectively inhibit cyclooxygenase-2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;296:558–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RONN A., NORGAARD K.M., LYKKEGAARD K., SVENDSEN O. Effects of pre- or postoperative morphine and of preoperative ketamine in experimental surgery in rats, evaluated by pain scoring and c-fos expression. Scand. J. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2000;27:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- SONG Y.T., BOWERSOX S.S., CONNOR D.T., DOOLEY D.J., LOTARSKI S.M., MALONE T., MILJANICH G., MILLERMAN E., RAFFERTY M.F., ROCK D., ROTH B.D., SCHMIDT J., STOEHR S., SZOKE B.G., TAYLOR C., VARTANIAN M., WANG Y.X. (S)-4-methyl-2-(methylamino)pentanoic acid 4,4-bis(4- fluorophenyl)butyl amide hydrochloride, a novel calcium channel antagonist, is efficacious in several animal models of pain. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm000134n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWART L.S.A., MARTIN W.J. Evaluation of postoperative analgesia in a rat model of incisional pain. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2003;42:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUDA M., KOIZUMI S., INOUE K. Role of endogenous ATP at the incision area in a rat model of postoperative pain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1701–1704. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200106130-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDERMEULEN E.P., BRENNAN T.J. Alterations in ascending dorsal horn neurons by a surgical incision in the rat foot. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1294–1302. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y.X., PETTUS M., GAO D., PHILLIPS C., BOWERSOX S.S. Effects of intrathecal administration of ziconotide, a selective neuronal N-type calcium channel blocker, on mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Pain. 2000;84:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARNER T.D., GIULIANO F., VOJNOVIC I., BUKASA A., MITCHELL J.A., VANE J.R. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOLF C.J., SHORTLAND P., COGGESHALL R.E. Peripheral-nerve injury triggers central sprouting of myelinated afferents. Nature. 1992;355:75–78. doi: 10.1038/355075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO T., SAKASHITA Y. The role of the spinal opioid receptor like1 receptor, the NK-1 receptor, and cyclooxygenase-2 in maintaining postoperative pain in the rat. Anesth. Analg. 1999;89:1203–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO T., SAKASHITA Y., NOZAKI-TAGUCHI N. Anti-allodynic effects of oral COX-2 selective inhibitor on postoperative pain in the rat. Can. J. Anaesth. 2000;47:354–360. doi: 10.1007/BF03020953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAHN P.K., BRENNAN T.J. Intrathecal metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists do not decrease mechanical hyperalgesia in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesth. Analg. 1998;87:1354–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAHN P.K., BRENNAN T.J. Incision-induced changes in receptive field properties of rat dorsal horn neurons. Anesthesiology. 1999a;91:772–785. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAHN P.K., BRENNAN T.J. Primary, and secondary hyperalgesia in a rat model for human postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1999b;90:863–872. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199903000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAHN P.K., GYSBERS D., BRENNAN T.J. Effect of systemic and intrathecal morphine in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:1066–1077. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAHN P.K., SLUKA K.A., BRENNAN T.J. Excitatory amino acid release in the spinal cord caused by plantar incision in the rat. Pain. 2002;100:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHU X., CONKLIN D., EISENACH I. Cyclooxygenase-1 in the spinal cord plays an important role in postoperative pain. Pain. 2003;104:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMAN M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]