Abstract

Current antitussive medications have limited efficacy and often contain the opiate-like agent dextromethorphan (DEX). The mechanism whereby DEX inhibits cough is ill defined. DEX displays affinity at both NMDA and sigma receptors, suggesting that the antitussive activity may involve central or peripheral activity at either of these receptors. This study examined and compared the antitussive activity of DEX and various putative sigma receptor agonists in the guinea-pig citric-acid cough model.

Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of DEX (30 mg kg−1) and the sigma-1 agonists SKF-10,047 (1–5 mg kg−1), Pre-084 (5 mg kg−1), and carbetapentane (1–5 mg kg−1) inhibited citric-acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs. Intraperitoneal administration of a sigma-1 antagonist, BD 1047 (1–5 mg kg−1), reversed the inhibition of cough elicited by SKF-10,047. In addition, two structurally dissimilar sigma agonists SKF-10,047 (1 mg ml−1) and Pre-084 (1 mg ml−1) inhibited cough when administered by aerosol.

Aerosolized BD 1047 (1 mg ml−1, 30 min) prevented the antitussive action of SKF-10,047 (5 mg kg−1) or DEX (30 mg kg−1) given by i.p. administration and, likewise, i.p. administration of BD 1047 (5 mg kg−1) prevented the antitussive action of SKF-10,047 given by aerosol (1 mg ml−1).

These results therefore support the argument that antitussive effects of DEX may be mediated via sigma receptors, since both systemic and aerosol administration of sigma-1 receptor agonists inhibit citric-acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs. While significant systemic exposure is possible with aerosol administration, the very low doses administered (estimated <0.3 mg kg−1) suggest that there may be a peripheral component to the antitussive effect.

Keywords: Sigma-1 agonist, antitussive, cough, guinea-pig

Introduction

Chronic cough associated with either irritation and/or inflammation of the airways is a common symptom of many respiratory diseases such as COPD, chronic bronchitis and asthma (Higenbottam, 2002). The most common antitussives in use today include the opioid, codeine, and the opiate-like agent dextromethorphan (DEX) (Grattan et al., 1995; Chung, 2003). These antitussives have limited efficacy and appear to act via a central mechanism (through receptors close to the cough center in the brainstem) (Chou & Wang, 1975). As a consequence, they often display an undesirable side effect profile including sedation, respiratory depression, and altered gastrointestinal motility (Tortella et al., 1994; Tarkkila et al., 1997; Eckhardt et al., 1998; Walker & Zacny, 1998; Hoffmann et al., 2003). Thus, there is a clinical need for a more effective antitussive that exhibits efficacy with a reduction in side effects.

The precise mechanism whereby DEX inhibits cough is still ill defined. DEX displays antagonist and agonist activity at the cationic NMDA receptor channel (Franklin & Murray, 1992) and sigma receptors (Chau et al., 1983), respectively, suggesting that the antitussive action of DEX may involve an action at either of these receptors. There is some additional evidence that DEX may also have some action at opioid receptors due to the structural similarities to opiates (Allen et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2002a, 2002b; Zhu et al., 2003). In mice, capsaicin-induced cough is attenuated by the NMDA receptor antagonists AP-5, AP-7, and MK801 (Kamei et al., 1989), at a similar dose as elicited by DEX. Sigma receptor agonists pentazocine and N-allylnormetazocine (SKF-10,047) also inhibit cough in rodents (Kamei et al., 1992a). The antitussive effect of DEX, given by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, is reversed by rimcazole, a nonselective sigma receptor antagonist (Kamei et al., 1993; Kotzer et al., 2000). Despite this evidence, the role of the sigma receptor in the modulation of cough as a novel therapeutic target for antitussives has been largely ignored.

Sigma receptors are a ubiquitous type of receptor whose function has not been well defined. The sigma-1 receptor sequence, while highly conserved (>90%) across mammalian species/tissues (Barnes et al., 1992; Schuster et al., 1995), does not display homology to any other known receptors, although it does share 30% homology with a fungal sterol isomerase (Moebius et al., 1996). Sigma receptors have a single transmembrane region (Prasad et al., 1998; Yamamoto et al., 1999), are 18–26 kDa molecular weight proteins, and there are at least two subtypes (σ1 and σ2) (McCann et al., 1994; Vilner et al., 1995; Bergeron & Debonnel, 1997). To date, only the sigma-1 receptor has been cloned (Kekuda et al., 1996; Seth et al., 1998; Mei & Pasternak, 2001) with cloning of the sigma-2 receptor proving difficult. Initially, the sigma receptor was thought to be an opioid receptor due to high-affinity enantiomer selective binding of various opiates as well as steroids and psychoactive drugs to the sigma receptor (Martin et al., 1976). This misnomer still persists, despite the re-classification as a nonopioid receptor and the effects of these opiates being insensitive to the opioid antagonist naltrexone (Vaupel, 1983).

Sigma receptors are found in various tissues throughout the body; however, the density is not uniform. The highest concentration of receptors is seen mainly in limbic and motor areas of the CNS, followed by the periphery (liver, spleen, endocrine, GI tract, and lung) (Roman et al., 1989; Wolfe et al., 1989; 1997; Whitlock et al., 1996; Alonso et al., 2000). The endogenous ligand for the sigma receptor is not yet known, but has been hypothesized to be progesterone (Meyer et al., 1998). While the specific function of the sigma receptor remains elusive, sigma receptors are present in high concentrations in areas of the CNS related to sensory processing such as the dorsal root ganglia and the nucleus tractus solitarus (NTS) (Walker et al., 1990; Alonso et al., 2000). The NTS is a site where the airway afferent fibers first synapse and an area very close to the cough center in the brainstem. This region, therefore, seems ideally placed to function as a ‘gate' for the cough reflex, and therefore antitussives acting through the sigma receptor could conceivably modulate afferent activity prior to reaching the cough center.

The role of sigma receptors in mediating the antitussive effects of DEX has not been systematically examined. Existing literature, which indicates the possible involvement of sigma-1 receptors, has all been conducted in the rat (Kamei et al., 1992a), a species in which it is difficult to measure cough consistently. To our knowledge, no one has investigated the role of sigma receptors using the guinea-pig, which, owing to the higher propensity to cough than rats, is a much preferred species to conduct antitussive research. The objective of this study was to further investigate whether DEX, as well as other putative sigma receptor agonists, inhibit citric-acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs.

Methods

Animals

Male Hartley guinea-pigs (425–475 g) were obtained from Elm Hill Laboratories (Chelmsford, MA, U.S.A.), barrier-housed in a clean environment with access to water and food ad libitum, and kept in a temperature-controlled environment maintained on a 12-h cycle. The colony was free of pathogens. The procedures used were approved by the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee of Cambridge.

In vivo cough

Unanesthetized male guinea-pigs were pretreated with compounds 30 min prior to the introduction of citric acid to induce cough. Animals were placed in individual PERSPEX™ cylindrical plethysmographs and exposed to citric acid aerosol (0.2 M) generated via an ultrasonic nebulizer (EMKA, Paris, France). Nebulization produced an aerosol with a mean particle size of 3.5 μM at a rate of approximately 0.5 ml min−1. The exposure period to the citric acid was 2 min, followed by a further observation period of 9 min. The total number of coughs, therefore, was determined over a total period of 11 min. Individual coughs were detected in three ways: (1) via a pressure transducer attached to the plethysmograph amplified onto a pen recorder, (2) via a microphone placed inside the plethysmograph, and (3) via visual observation of the animal. Each animal was exposed to citric acid only once.

Compound administration

For i.p. administration, animals were injected with the compounds carbetapentane, SKF-10,047, DEX or PRE 084 (1–30 mg kg−1), 30 min prior to citric acid. In an attempt to investigate the potential peripheral action of the sigma agonists, we administered these agonists by aerosol in addition to systemic administration. For aerosol exposure, the compounds were aerosolized via whole-body exposure using an ultrasonic nebulizer for 30 min prior to citric acid exposure. The inhaled dose of sigma agonists SKF-10,047 and 2-(4-morpholinethyl) 1-phenylcyclohaxanecarboxylate hydrochloride (Pre-084; 1 mgml−1) in this study was estimated to be <0.3 mg kg−1, as calculated according to Karlsson et al. (1990). For reversal studies, N-(2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl)-N-methyl-2-)dimethylamino ethylamine (BD 1047) (a reported sigma-1 antagonist with 10-fold selectivity for the sigma-1 receptor over the sigma-2 receptor (Matsumoto et al., 1995), or saline vehicle, was administered, by either aerosol or i.p. route, 30 min prior to agonist administration.

Membrane preparation for sigma-1-binding assay

Brain homogenate was prepared from frozen male Hartley guinea-pig brains (Harlan Laboratories Westbury, NY, U.S.A.), by placing whole brains (minus cerebellum) in ice-cold 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 0.32 M sucrose, and homogenizing in a volume of 10 ml g−1 tissue (Tekmar homogenizer). This was followed by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 31,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, resuspended at 3 ml g−1 and incubated at 25°C for 15 min. This was then centrifuged at 31,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting pellets were resuspended by homogenization to final volume of 1.53 ml g−1 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and aliquots stored at −70°C until use. Protein was estimated using a BCA Protein estimation kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.).

Sigma-1-binding assay

On the day of the assay, membrane aliquots were thawed, resuspended in fresh Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), and stored on ice until required. Assays were conducted in 96-well polypropylene plates (total volume 250 μl per well). Each assay well contained 65 μl of [3H]-pentazocine (final concentration 5 nM), 60 μl assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), 5 μl sigma-1 agonist (diluted in DMSO) and 120 μl membrane preparation (approximately 170 μg protein). Total binding (TB) and nonspecific binding (NSB) wells contained DMSO or unlabelled pentazocine (10 μM), respectively, in place of the compound. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 2 h before termination of the assay by filtration through GF/B filterplates that had been prewetted with 0.5% polyethylinimine for at least 30 min prior to use. Filters were washed twice with a total of 400 μl (2 × 200 μl) Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 8.0). Once the filters dried, this was followed by the addition of 50 μl scintillation fluid per well (Microscint-20). The amount of bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry using a Packard Topcount liquid scintillation counter (Perkin-Elmer, Downers Grove, IL, U.S.A.).

Materials

Citric acid, carbetapentane, DEX, and SKF-10,047 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Pre-084 and BD 1047 were obtained from Tocris (Ballwin, MO, U.S.A.). All compounds were dissolved in saline (0.9%), unless stated otherwise.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed by Students' unpaired t-test for individual comparisons, and by repeated-measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's or Bonferroni post-test for individual comparisons between groups. Differences were considered significant when P<0.05 (*).

Results

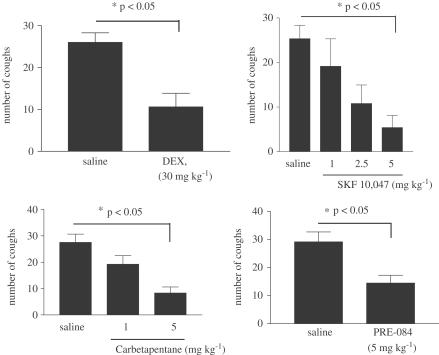

I.p. administration of sigma agonists

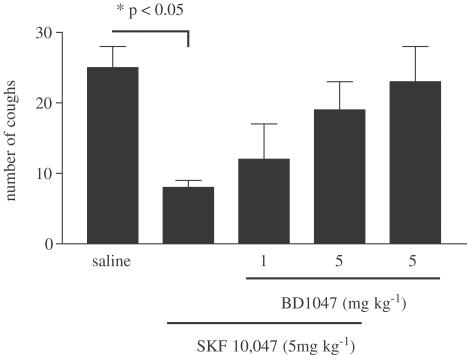

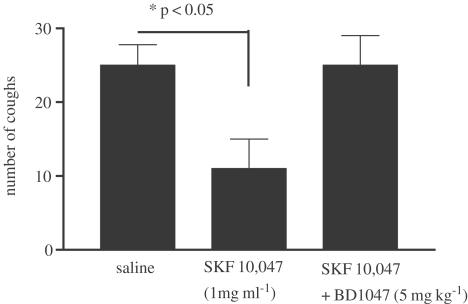

In control animals treated with vehicle (saline), citric acid elicited 28±3 coughs (n=9) during the 11-min observation period. DEX (30 mg kg−1) inhibited cough (11±3, n=6), with the maximal inhibition of approximately 60% (Figure 1a). Lower doses of DEX did not elicit a significant antitussive effect (results not shown). The selective sigma-1 receptor agonist SKF-10,047 (1–5 mg kg−1) inhibited cough in a dose-dependent manner, with maximal inhibition of cough (80%) apparent at 5 mg kg−1 (Figure 1b). Two other sigma-1 receptor agonists, carbetapentane (1–5 mg kg−1) and Pre-084 (5 mg kg−1), both inhibited citric-acid-induced cough with maximal inhibitions of 50 and 70%, respectively (Figure 1c, d). Pretreatment of animals with the sigma-1 receptor antagonist BD 1047 (1–5 mg kg−1) reversed the inhibition of cough elicited by SKF-10,047 (5 mg kg−1) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2). Administration of BD 1047 alone (5 mg kg−1) did not have any effect on cough.

Figure 1.

Ability of various sigma-1 agonists, when given by i.p. administration, to inhibit citric-acid-induced cough compared to saline vehicle. (a) DEX (30 mg kg−1, n=9, 6), (b) SKF-10,047 (1–5 mg kg−1, n=9, 6, 5, and 5), (c) carbetapentane (1–5 mg kg−1, n=9, 8, and 6), (d) Pre-084 (5 mg kg−1, n=7, 10). In parenthesis, results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of the respective number of observations for each treatment. Statistics, where appropriate, show P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's post-test).

Figure 2.

Reversal of the antitussive effect of i.p. administered SKF-10,047 (5 mg kg−1) by pretreatment with σ−1 antagonist BD 1047 (1–5 mg kg−1, i.p.). BD 1047 alone elicited no antitussive effect. Results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 13, 11, 7, 16, and 11 observations, respectively. P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test). No other comparisons demonstrated significance.

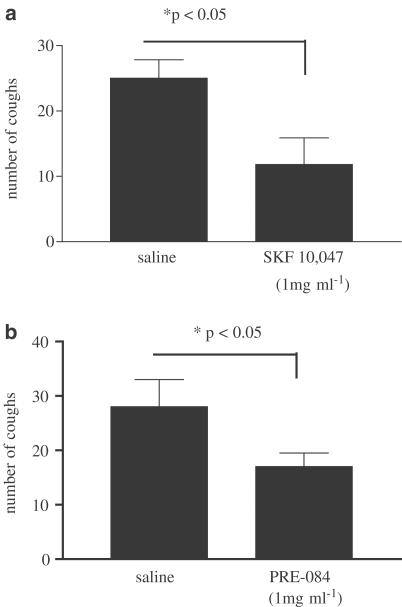

Aerosol administration of sigma agonists

SKF-10,047 (1 mg ml−1), administered for 30 min prior to citric acid exposure, inhibited cough with a maximal inhibition of 53% (Figure 3a). Likewise, Pre-084 (1 mg ml−1), administered for 30 min prior to citric acid exposure, also inhibited cough by 37% when given by aerosol (Figure 3b). The estimated inhaled dose of these agonists was <0.3 mg kg−1, 10 times lower than the systemically administered concentrations required to see antitussive effects.

Figure 3.

Effect of SKF-10,047 (1 mg ml−1) and Pre-084 (1 mg ml−1), dissolved in saline and given by aerosol administration, on citric-acid-induced cough. Results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 19 and 11 observations, respectively, for SKF-10,047, and 8 and 7 for Pre-084. P<0.05 (Student's unpaired t-test).

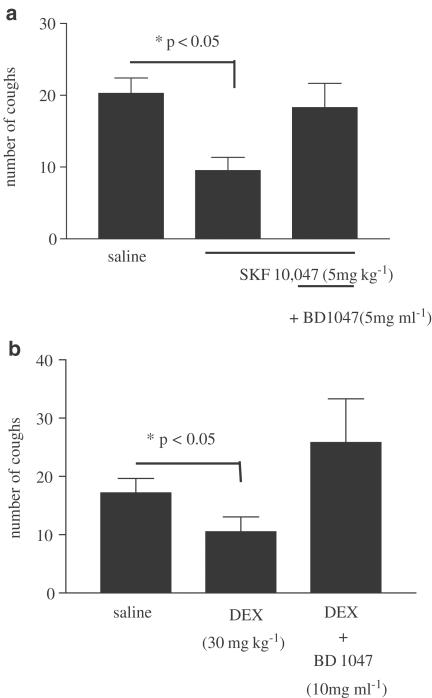

Aerosol administration of the sigma-1 antagonist BD 1047 reverses the antitussive effects of SKF-10,047 and DEX

We wanted to further explore whether the antitussive effect of the sigma agonists could be mediated via peripheral sigma-1 receptors. This was investigated by examining the ability of the sigma-1 receptor antagonist BD 1047 to inhibit the antitussive action of sigma-1 agonists when given by various routes. BD 1047, when given by aerosol (5–10 mg ml−1 for 30 min prior to citric acid), reversed the inhibition of cough by i.p. SKF-10,047 (5 mg kg−1) or DEX (30 mg kg−1) (Figure 4a, b). Similarly, to confirm the involvement of a peripherally activated sigma-1 receptor in the inhibition of cough, we examined the ability of the selective sigma-1 antagonist BD 1047 (5 mg kg−1, i.p. 30 min prior to citric acid) to reverse the inhibition of cough by aerosol administration of SKF-10,047 (1 mg ml−1). Pretreatment with BD 1047 prevented the antitussive effect of SKF-10,047 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of BD 1047 (5–10 mg ml−1), dissolved in saline and given by aerosol administration, on the antitussive effect of (a) SKF-10,047 (5 mg kg−1, n=8, 8, and 10) or (b) DEX (30 mg kg−1, n=9, 6, and 6) given by i.p. administration. In parenthesis, results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of the respective number of observations for each treatment. Statistics, where appropriate, show P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-test).

Figure 5.

Effect of BD 1047 (5 mg kg−1), given by i.p. administration, on the antitussive activity of SKF-10,047 (1 mg ml−1) given by aerosol administration. Results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 19, 11, and 7 observations, respectively. P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-test).

Competitive binding of [3H](+) pentazocine

The reference sigma agonists used in the in vivo cough assay were examined for their binding affinity in guinea-pig brain (Table 1). The Ki's reported in this table are similar to those reported in the literature, and support binding to a distinct common site. The rank ordering of affinity (highest to lowest) was as follows: BD 1047>Pre-084>SKF-10,047>carbetapentane>DEX.

Table 1.

Comparison of the binding affinity of various sigma-1 agonists determined by competitive binding to [3H]-pentazocine-labelled sites on guinea-pig brain membranes

| Sigma ligand | Ki (nM)±s.e.m. |

|---|---|

| SKF 10,047 | 22±6, n=5 |

| Dextromethorphan | 365±29, n=7 |

| Carbetapentane | 75±28, n=3 |

| PRE-084 | 9.0±1.25, n=3 |

| BD 1047H | 1.54±0.4, n=5 |

This table reflects the calculated Ki's (mean±s.e.m.) and the number of observations.

Discussion

The most common antitussives in use today include the opioid codeine and the opiate-like agent DEX (Lee et al., 2000; Chung, 2003). DEX displays significant affinity at sigma receptors (Chau et al., 1983); however, a defined role of peripheral sigma receptors as antitussives has not been systematically examined. The objective of this study was to further investigate whether DEX, as well as other putative sigma receptor agonists, inhibit citric-acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs.

In this study, using the citric-acid-induced guinea-pig cough model, we report that DEX and various selective, structurally dissimilar, sigma-1 agonists inhibit cough when administered by two separate routes of administration (either i.p. injection or whole-body aerosol exposure). The inhibition of cough was striking and, furthermore, concentration dependent for two of the agonists studied, SKF-10,047 and carbetapentane. This observation is similar to an earlier study which reported that certain sigma-1 agonists (including SKF-10,047, 1,3-di-(2-tolyl)guanidine (DTG) and pentazocine) inhibited capsaicin-induced cough in rats (Kamei, 1999). Both DTG and pentazocine display affinity at sigma-2 receptors in addition to sigma-1 receptors (Hellewell et al., 1994), and pentazocine has significant affinity at opioid receptors (μ and δ subtypes; Kamei et al., 1994). Activation of these subtypes of opioid receptor has also been shown by the same authors to inhibit cough in this model (Kamei et al., 1992b, 1994). In our examination of cough, in addition to the protypical agonist SKF-10,047, we used two additional selective sigma-1 agonists Pre-084 and carbetapentane to confirm the involvement of sigma-1 receptors in the inhibition of cough.

Interestingly, we observed that the doses of sigma agonists required to inhibit cough in our study were much lower than DEX, indicating that the sigma agonists were more efficacious antitussives compared to DEX. A tentative explanation may be the relative affinities of the agonists used in this study for the sigma-1 receptor. The affinity of DEX at the sigma-1 receptor is reported to be in the high nanomolar range (Ki=200–500 nM) (Walker et al., 1990). In contrast, the affinity of the agonists used in this study were several fold higher: SKF-10,047 (22 nM; Walker et al., 1990; Chou et al., 1999), carbetapentane (75 nM; Calderon et al., 1994), and Pre-084 (7.7 nM; Su et al., 1991). Thus, if the sigma-1 receptor is indeed responsible for the antitussive activity noted in our investigation, this might explain the higher concentrations of DEX required to elicit a similar effect. Alternatively, perhaps the discrepancy may be due to the relative nonselectivity of DEX compared to the prototypical sigma-1 agonists used here. For example, the antitussive activity of DEX can be reversed by methysergide, the 5-HT1/5-HT2 receptor antagonist, indicating the involvement of 5-HT receptors in any antitussive effects (Kamei, 1996). In addition, DEX displays a significant affinity for NMDA receptors (Franklin & Murray, 1992), in contrast to several of the sigma-1 agonists used here, since neither Pre-084 nor carbetapentane have reported affinity for NMDA receptors. SKF-10,047 does have moderate affinity for the NMDA receptor (Wardley-Smith & Wann, 1989). The ability of DEX to modulate glutaminergic sensory neurotransmission via the NMDA receptor complicates the definition of the mechanism of action of this drug (Gronier & Debonnel, 1999). Although the precise neurotransmission process involved in cough is still under debate, any drug that modulates this process could conceivably affect the generation of cough.

Clarification of the involvement of the sigma-1 receptor as an antitussive target was supported by the ability of BD 1047, having no effect by itself, to completely prevent the antitussive effect of SKF-10,047. Although evidence suggests that SKF-10,047 can act at other receptors including NMDA and opiate receptors (Tam, 1985; Wardley-Smith & Wann, 1989), the use of a specific antagonist of sigma-1 (BD 1047) to reverse the effect of SKF-10,047 supports the suggestion that SKF-10,047 is acting as a sigma-1 agonist in the present investigation. Reversal of the antitussive effect of DEX by nonselective sigma antagonists, rimcazole and haloperidol, has been previously demonstrated (Kamei et al., 1993; Kotzer et al., 2000). To our knowledge, however, BD 1047 is a more selective sigma-1 receptor antagonist than either rimcazole or haloperidol. Although it has been suggested that BD 1047 can act as a partial agonist at high concentrations in vivo (Zambon et al., 1997), BD 1047 alone had no effect on cough in the present investigation. Additionally, since the concentrations of BD 1047 used in this study were relatively low (5 mg kg−1), it is unlikely that nonspecific effects of BD 1047 are involved in our study. While BD 1047 can have affinity at sigma-2 receptors (47 nM), this is 50-fold less than its affinity at sigma-1 (0.9 nM). While we cannot rule out the possible involvement of sigma-2 receptors, there are no sigma-2 antagonists commercially available to test in the current study.

The specific function of the sigma receptor remains elusive; however, sigma receptors are present in high concentrations in the NTS, a site where the afferent fibers first synapse and an area very close to the cough center in the brainstem (Shook et al., 1990). This region therefore may function as a ‘gate' for the cough reflex and allow antitussives, acting through the sigma receptor, to modulate afferent activity prior to reaching the cough center. In order to activate this site, sigma-1 agonists have to be able to reach the systemic circulation prior to penetrating the CNS. It is conceivable that systemic administration of highly lipophilic sigma-1 agonists might penetrate the CNS, and we have clearly shown that sigma agonists inhibited cough when given by the i.p. route. Nevertheless, sigma receptors also exist in the periphery including the lung (DeHaven-Hudkins et al., 1994; our unpublished observations), where they may also be capable of modulating cough. This has been demonstrated by the finding that DEX inhibits cough when administered peripherally using aerosol (Callaway et al., 1991; Grattan et al., 1995). Based upon this information, we investigated whether administration of sigma agonists (SKF-10,047 and Pre-084) by aerosol would inhibit cough in our study. It is thought that, at least temporally, whole-body aerosol administration immediately prior to citric-acid-induced cough would confine the deposition of sigma-1 agonist to the local site (airways and lung), and thereby activate sigma receptors that predominantly exist in this region. Both SKF-10,047 and Pre-084 significantly inhibited cough when given via this route, indicating that peripheral pulmonary sigma receptors may be partially responsible for the apparent antitussive effect, and indeed the lung may be an additional site of action for these agonists to inhibit cough. A likely criticism of this study is the lack of confirmation of a peripheral localization of the sigma agonists following aerosol administration and the ruling out of systemic exposure. To address this, we attempted to calculate the approximate dose of sigma agonist received when given by this route, which for the guinea-pig was estimated to be <0.3 mg kg−1, approximately 10-fold less than the dose required to be given by the i.p. route to see an antitussive effect. Thus, we believe that the very low doses administered this way are effective at inhibiting cough, presumably because of the deliverance direct to the site of action. We examined the ability of aerosolized sigma-1 antagonist BD 1047 to inhibit cough elicited by SKF-10,047 or DEX when these agonists were administered via i.p. administration. In addition, we also examined the ability of BD 1047 give by i.p. administration to reverse the peripheral administration of SKF-10,047. The sigma-1 antagonist BD 1047 given by aerosol immediately prior to citric-acid exposure prevented the antitussive effect of SKF-10,047 or DEX given via the i.p. route. Similarly, BD 1047 given systemically inhibited the antitussive effect of peripheral administration of SKF-10,047. These results, in addition to the ability of the two distinct sigma-1 agonists to inhibit cough when administered by aerosol, would suggest that the sigma agonists may likely be acting, at least partially, peripherally to inhibit cough. From a therapeutic standpoint, a peripherally acting antitussive would be more beneficial, since it may not be associated with the side effects commonly seen with centrally acting antitussives.

In conclusion, sigma-1 agonists alone are capable of inhibiting citric-acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs when administered by two separate routes of administration. The ability of a selective sigma-1 antagonist to prevent the antitussive effect of a sigma agonist and DEX supports the role for sigma-1 receptors in mediating the antitussive action of DEX. A component of the antitussive effects may be mediated peripherally, since aerosol administration of low concentrations of sigma agonists also inhibited cough. A peripheral activity for DEX has been demonstrated previously (Callaway et al., 1991; Grattan et al., 1995). It is possible that selective sigma-1 agonists targeted towards sigma-1 receptors may prove to be novel, useful antitussive agents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by UCB Research Inc., UCB Pharma, 840 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 02139, U.S.A.

Abbreviations

- BD 1047

(N-(2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl)-N-methyl-2-) dimethylamino) ethylamine

- DEX

dextromethorphan

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarus

- Pre-084

2-(4-morpholinethyl) 1-phenylcyclohaxanecarboxylate hydrochloride

- σ-1

Sigma-1

- SKF-10,047

N-allylnormetazocine

References

- ALLEN R.M., GRANGER A.L., DYKSTRA L.A. Dextromethorphan potentiates the antinociceptive effects of morphine and the delta-opioid agonist SNC80 in squirrel monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;300:435–441. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALONSO G., PHAN V., GUILLEMAIN I., SAUNIER M., LEGRAND A., ANOAL M., MAURICE T. Immunocytochemical localization of the sigma(1) receptor in the adult rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2000;97:155–170. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKER A.K., HOFFMANN V.L., MEERT T.F.Dextromethorphan and ketamine potentiate the antinociceptive effects of mu- but not delta- or kappa-opioid agonists in a mouse model of acute pain Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002a7473–86.(4: Allen RM et al. Dextromethorphan potentiates.... (PMID: 11805202)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKER A.K., HOFFMANN V.L., MEERT T.F. Interactions of NMDA antagonists and an alpha 2 agonist with mu, delta and kappa opioids in an acute nociception assay. Acta Anaesthesiol. Belg. 2002b;53:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES J.M., BARNES N.M., BARBER P.C., CHAMPANERIA S., COSTALL B., HORNSBY C.D., IRONSIDE J.W., NAYLOR R.J. Pharmacological comparison of the sigma recognition site labelled by [3H]haloperidol in human and rat cerebellum. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1992;345:197–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00165736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGERON R., DEBONNEL G. Effects of low and high doses of selective sigma ligands: further evidence suggesting the existence of different subtypes of sigma receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1997;129:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s002130050183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALDERON S.N., IZENWASSER S., HELLER B., GUTKIND J.S., MATTSON M.V., SU T.P., NEWMAN A.H. Novel 1-phenylcycloalkanecarboxylic acid derivatives are potent and selective sigma 1 ligands. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2285–2291. doi: 10.1021/jm00041a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALLAWAY J.K., KING R.G., BOURA A.L. Evidence for peripheral mechanisms mediating the antitussive actions of opioids in the guinea pig. Gen. Pharmacol. 1991;22:1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(91)90585-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAU T.T., CARTER F.E., HARRIS L.S. Antitussive effect of the optical isomers of mu, kappa and sigma opiate agonists/antagonists in the cat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983;226:108–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOU D.T., WANG S.C. Studies on the localization of central cough mechanism; site of action of antitussive drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1975;194:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOU Y.C., LIAO J.F., CHANG W.Y., LIN M.F., CHEN C.F. Binding of dimemorfan to sigma-1 receptor and its anticonvulsant and locomotor effects in mice, compared with dextromethorphan and dextrorphan. Brain Res. 1999;821:516–519. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG K.F. Current and future prospects for drugs to suppress cough. IDrugs. 2003;6:781–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEHAVEN-HUDKINS D.L., LANYON L.F., FORD-RICE F.Y., ATOR M.A. Sigma recognition sites in brain and peripheral tissues. Characterization and effects of cytochrome P450 inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECKHARDT K., LI S., AMMON S., SCHANZLE G., MIKUS G., EICHELBAUM M.Same incidence of adverse drug events after codeine administration irrespective of the genetically determined differences in morphine formation Pain 19987627–33.(3: Tarkkila P et al. Comparison of respiratory eff… (PMID: 9347436)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANKLIN P.H., MURRAY T.F. High affinity [3H]dextrorphan binding in rat brain is localized to a noncompetitive antagonist site of the activated N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-cation channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:134–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRATTAN T.J., MARSHALL A.E., HIGGINS K.S., MORICE A.H. The effect of inhaled and oral dextromethorphan on citric acid induced cough in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;39:261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRONIER B., DEBONNEL G. Involvement of sigma receptors in the modulation of the glutamatergic/NMDA neurotransmission in the dopaminergic systems. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;368:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELLEWELL S.B., BRUCE A., FEINSTEIN G., ORRINGER J., WILLIAMS W., BOWEN W.D. Rat liver and kidney contain high densities of sigma 1 and sigma 2 receptors: characterization by ligand binding and photoaffinity labeling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;268:9–18. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higenbottam T. Chronic cough and the cough reflex in common lung diseases. Pulmonary Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;15:241–247. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2002.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMANN V.L., VERMEYEN K.M., ADRIAENSEN H.F., MEERT T.F.Effects of NMDA receptor antagonists on opioid-induced respiratory depression and acute antinociception in rats Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 200374933–941.(2: Dematteis M et al. Dextromethorphan and dextrorp… (PMID: 9794151)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J. Role of opioidergic and serotonergic mechanisms in cough and antitussives. Pulmon. Pharmacol. 1996;9:349–356. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J. Possible role of sigma-receptors in the regulation of cough reflex, gastrointestinal and retinal function. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1999;114:35–41. doi: 10.1254/fpj.114.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., IWAMOTO Y., KAWASHIMA N., HITOSUGI H., MISAWA M., KASUYA Y. Involvement of haloperidol-sensitive sigma-sites in antitussive effects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992a;224:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)94815-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., IWAMOTO Y., MISAWA M., KASUYA Y. Effects of rimcazole, a specific antagonist of sigma sites, on the antitussive effects of non-narcotic antitussive drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;242:209–211. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90083-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., IWAMOTO Y., MISAWA M., NAGASE H., KASUYA Y. Antitussive effect of (+/−) pentazocine in diabetic mice is mediated by delta-sites, but not by mu- or kappa-opioid receptors. Yakubutsu Seishin Kodo. 1994;14:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., KATSUMA K., KASUYA Y. Involvement of mu-opioid receptors in the antitussive effects of pentazocine. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1992b;345:203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00165737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., TANIHARA H., IGARASHI H., KASUYA Y. Effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists on the cough reflex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;168:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARLSSON J.A., LANNER A.S., PERSSON C.G. Airway opioid receptors mediate inhibition of cough and reflex bronchoconstriction in guinea pigs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;252:863–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEKUDA R., PRASAD P.D., FEI Y.J., LEIBACH F.H., GANAPATHY V. Cloning and functional expression of the human type 1 sigma receptor (hSigmaR1) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;229:553–558. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTZER C.J., HAY D.W., DONDIO G., GIARDINA G., PETRILLO P., UNDERWOOD D.C. The antitussive activity of delta-opioid receptor stimulation in guinea pigs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE P.C.L., JAWAD M.S., ECCLES R. Antitussive efficacy of dextromethorphan in cough associated with acute upper respiratory tract infection. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000;52:1137–1142. doi: 10.1211/0022357001774903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN W.R., EADES C.G., THOMPSON J.A., HUPPLER R.E., GILBERT P.E. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine-like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1976;197:517–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUMOTO R.R., BOWEN W.D., TOM M.A., VO V.N., TRUONG D.D., DE COSTA B.R. Characterization of two novel sigma receptor ligands: antidystonic effects in rats suggest sigma receptor antagonism. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;280:301–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCANN D.J., WEISSMAN A.D., SU T.P.Sigma-1 and sigma-2 sites in rat brain: comparison of regional, ontogenetic, and subcellular patterns Synapse 199417182–189.(5: Roman F et al. Autoradiographic localization… (PMID: 2542120)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEI J., PASTERNAK G.W. Molecular cloning and pharmacological characterization of the rat sigma1 receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;62:349–355. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER C., SCHMIEDING K., FALKENSTEIN E., WEHLING M. Are high-affinity progesterone binding site(s) from porcine liver microsomes members of the sigma receptor family. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;347:293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOEBIUS F.F., BERMOSER K., REITER R.J., HANNER M., GLOSSMANN H. Yeast sterol C8–C7 isomerase: identification and characterization of a high-affinity binding site for enzyme inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16871–16878. doi: 10.1021/bi961996m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRASAD P.D., LI H.W., FEI Y.J., GANAPATHY M.E., FUJITA T., PLUMLEY L.H., YANG-FENG T.L., LEIBACH F.H., GANAPATHY V. Exon–intron structure, analysis of promoter region, and chromosomal localization of the human type 1 sigma receptor gene. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMAN F., PASCAUD X., CHOMETTE G., BUENO L., JUNIEN J.L.Autoradiographic localization of sigma opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract of the guinea pig Gastroenterology 19899776–82.(6: Wolfe JR SA et al. Sigma-receptors in endocrine… (PMID: 2537173)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUSTER D.I., ARNOLD F.J., MURPHY R.B.Purification, pharmacological characterization and photoaffinity labeling of sigma receptors from rat and bovine brain Brain Res. 199567014–28.(2: Barnes JM et al. Pharmacological comparison of… (PMID: 1314960)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SETH P., FEI Y.J., LI H.W., HUANG W., LEIBACH F.H., GANAPATHY V. Cloning and functional characterization of a sigma receptor from rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:922–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70030922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOOK J.E., WATKINS W.D., CAMPORESI E.M. Differential roles of opioid receptors in respiration, respiratory disease, and opiate-induced respiratory depression. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;142:895–909. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SU T.P., WU X.Z., CONE E.J., SHUKLA K., GUND T.M., DODGE A.L., PARISH D.W. Sigma compounds derived from phencyclidine: identification of PRE-084, a new, selective sigma ligand. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAM S.W. [3H]SKF 10,047, (+)-[3H]ethylketocyclazocine, mu, kappa, delta and phencyclidine binding sites in guinea pig brain membranes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;109:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TARKKILA P., TUOMINEN M., LINDGREN L. Comparison of respiratory effects of tramadol and oxycodone. J. Clin. Anesth. 1997;9:582–585. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORTELLA F.C., ROBLES L., WITKIN J.M., NEWMAN A.H. Novel anticonvulsant analogs of dextromethorphan: improved efficacy, potency, duration and side-effect profile. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUPEL D.B. Naltrexone fails to antagonize the sigma effects of PCP and SKF 10,047 in the dog. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1983;92:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILNER B.J., JOHN C.S., BOWEN W.D. Sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors are expressed in a wide variety of human and rodent tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995;55:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER D.J., ZACNY J.P.Subjective, psychomotor, and analgesic effects of oral codeine and morphine in healthy volunteers Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1998140191–201.(2: Eckhardt K et al . Same incidence of adverse dru… (PMID: 9696456)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER J.M., BOWEN W.D., WALKER F.O., MATSUMOTO R.R., DE COSTA B., RICE K.C. Sigma receptors: biology and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1990;42:355–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARDLEY-SMITH B., WANN K.T. The effects of non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonists on rats exposed to hyperbaric pressure. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;165:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90775-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITLOCK B.B., LIU Y., CHANG S., SAINI P., HA B.K., BARRETT T.W., WOLFE S.A., JR Initial characterization and autoradiographic localization of a novel sigma/opioid binding site in immune tissues. J. Neuroimmunol. 1996;67:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(96)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLFE S.A., JR, CULP S.G., DE SOUZA E.B. Sigma-receptors in endocrine organs: identification, characterization, and autoradiographic localization in rat pituitary, adrenal, testis, and ovary. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1160–1172. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-3-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLFE S.A., JR, HA B.K., WHITLOCK B.B., SAINI P.Differential localization of three distinct binding sites for sigma receptor ligands in rat spleen J. Neuroimmunol. 19977245–58.(3: Whitlock BB et al . Initial characterization and… (PMID: 8765330)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO H., MIURA R., YAMAMOTO T., SHINOHARA K., WATANABE M., OKUYAMA S., NAKAZATO A., NUKADA T. Amino acid residues in the transmembrane domain of the type 1 sigma receptor critical for ligand binding. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMBON A.C., DE COSTA B.R., KANTHASAMY A.G., NGUYEN B.Q., MATSUMOTO R.R. Subchronic administration of N-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl) ethyl]-N-methyl-2-(dimethylamino) ethylamine (BD1047) alters sigma 1 receptor binding. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;324:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHU H., JENAB S., JONES K.L., INTURRISI C.E.The clinically available NMDA receptor antagonist dextromethorphan attenuates acute morphine withdrawal in the neonatal rat Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2003142209–213.(2: Baker AK et al . Interactions of NMDA antagoni… (PMID: 12461830)related articles, links) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]