Abstract

Our objective was to determine whether α2A-adrenoceptors modulate the baroreceptor reflex. The efficacy of the reflex was evaluated by measuring the spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate variability at rest and the heart rate responses to evoked changes in blood pressure. Experiments were carried out in conscious, unrestrained, and anaesthetized α2A-adrenoceptor-deficient (α2A-KO) mice and WT mice.

In conscious α2A-KO mice, the spontaneous blood pressure variability was greater, and the spontaneous heart rate variability was lower than in conscious WT mice. This was also observed in anaesthetized animals.

The reflex bradycardia after intravenous injection of phenylephrine was greatly attenuated in conscious α2A-KO compared to conscious WT mice; the baroreceptor reflex gain (ratio maximal change in heart rate/maximal change in mean arterial pressure) was decreased by 40%.

Similar results were obtained when reflex bradycardia was elicited by intra-arterial volume loading of conscious WT and α2A-KO mice. The baroreceptor reflex gain upon volume loading was also low in anaesthetized α2A-KO mice.

The reflex tachycardia evoked by intravenous sodium nitroprusside injection was also significantly less in α2A-KO mice as compared to WT, conscious as well as anaesthetized; the baroreceptor reflex gains were decreased by 50 and 65%, respectively.

Direct stimulation of cardiac β-adrenoceptors by the agonist isoprenaline produced similar cardioacceleration in α2A-KO and WT animals.

Our results show that the baroreceptor reflex function is impaired in mice lacking α2A-adrenoceptors. We conclude that central α2A-adrenoceptors facilitate the reflex response to both loading and unloading of the arterial baroreceptors.

Keywords: α2A-Adrenoceptors, anaesthetized mice, baroreceptor reflex, blood pressure, cardiovascular regulation, conscious mice, heart rate, knockout mice

Introduction

The baroreceptor reflex represents the major mechanism of rapid adjustment to blood pressure changes. The afferents from the baroreceptors of the carotid sinus and aortic arch terminate almost exclusively in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS). Short neuronal pathways then connect the afferents to parasympathetic efferents (in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus) and sympathetic efferents (in the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata, RVLM) in such a way that stimulation of the carotid or aortic stretch receptors by a blood pressure increase is followed by a rise in vagal tone and a decrease in sympathetic tone, and vice versa (for review, see Dampney, 1994; Singewald & Philippu, 1996; Aicher et al., 2000; Dampney et al., 2002; Stauss, 2002).

More than 25 years ago, Haeusler (1975) suggested that α-adrenoceptors activated by clonidine (i.e., α2-adrenoceptors, but this term was new at that time and Haeusler did not use it) were present on some neurons of the medullary baroreflex pathway, and that these receptors, although not themselves constituents of the reflex, modulated it. Since then, several studies have supported Haeusler's hypothesis. α2-Adrenoceptors occur in all cardiovascular brain stem nuclei at high density (Scheinin et al., 1994; Tavares et al., 1996), and their expression in the NTS and the RVLM is increased following chronic impairment of the baroreflex by surgical denervation of the aortic baroreceptors (El-Mas & Abdel-Rahman, 1997). Reflex heart rate responses to baroreceptor loading and unloading are enhanced when the α2-adrenoceptor agonists clonidine and α-methylnoradrenaline (or its precursor, α-methyldopa) are injected into the cisterna cerebellomedullaris or microinjected into the NTS (Badoer et al., 1983; Kubo et al., 1990). Conversely, the reflex bradycardia induced by electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus or aortic depressor nerves is decreased when the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine is injected into the vertebral artery or microinjected into the NTS (Huchet et al., 1981; 1983; Kubo et al., 1990). Overall, these studies indicate that activation of brain stem α2-adrenoceptors facilitates the reflex response to blood pressure changes.

Several points remain, however, questionable or unanswered. First, in the publications cited above, yohimbine was used as an α2-antagonist. Yohimbine, however, may also act on α1-adrenoceptors, dopamine, and serotonin receptors (Goldberg & Robertson, 1983), and, in one study, the baroreflex function actually was not altered by yohimbine (Knuepfer et al., 1993). Second, no previous study discriminated between the different α2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Experiments using autoradiography, immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization indicate that, although the main α2-adrenoceptor subtype in the cardiovascular nuclei of the brain stem is α2A, the two other subtypes α2B and α2C are also present (Boyajian et al., 1987; Scheinin et al., 1994; Rosin et al., 1996; Tavares et al., 1996). Third, the exact role of α2-adrenoceptors within the baroreflex loop – whether a necessary link or only facilitatory – has not been firmly established. For example, in some studies, microinjection of yohimbine into the NTS or the nucleus ambiguus did not only attenuate, but even abolished the reflex bradycardia induced by intra-arterial volume loading or electrical stimulation of the aortic nerve (Gurtu et al., 1982; 1983; Sved et al., 1992), suggesting that α2-adrenoceptors did not only modulate, but were even required for, baroreceptor reflex function.

The objective of the present study was to re-examine the role of α2-adrenoceptors in the baroreceptor reflex and to identify the subtype involved. Disruption of receptor genes represents a new tool to elucidate receptor mechanisms. Therefore, we used mice in which the gene encoding the α2A-adrenoceptor had been disrupted (α2A-KO; Altman et al., 1999; for review, see Hein, 2001). Mice sharing the genetic background of the α2A-KO animals (wild type (WT)) were used as controls. The efficacy of the baroreceptor reflex was evaluated by two approaches. First, spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate oscillations at rest were analyzed; an impairment of the baroreflex increases the spontaneous fluctuations in blood pressure, whereas the spontaneous fluctuations in heart rate are decreased (Parati et al., 1997; Pires et al., 2001; Souza Neto et al., 2003). Second, the baroreflex gain following evoked changes in blood pressure was examined. For this purpose, reflex decreases in heart rate were elicited by bolus injection of phenylephrine or, nonpharmacologically, by intra-arterial volume loading, and reflex increases in heart rate were elicited by bolus injection of sodium nitroprusside. Most experiments were carried out in conscious, unrestrained animals, but some assessments were also done in anaesthetized mice.

Methods

Animals

The α2A-adrenoceptor-deficient (α2A-KO) mice have been described previously (Altman et al., 1999; Hein et al., 1999). The experiments were carried out on male α2A-KO and WT (C57BL/6x129Sv) mice aged 12–16 weeks (mean body weight=31±1 g). Genotypes were checked from DNA probes isolated from the tail of the animals. All procedures and experiments were approved by the Committee for Animal Experiments of the district of Freiburg (Tierversuchskommission).

Surgery

Animals were anaesthetized with halothane (1–2%). A polyethylene catheter (0.28 mm i.d., 0.61 mm o.d.) was implanted into the abdominal aorta (through the right femoral artery, 1–2 mm beyond the iliac bifurcation) for recording blood pressure and heart rate; this catheter was also used to sample blood for the determination of the plasma noradrenaline concentration. A second catheter was implanted into the right femoral vein for intravenous (i.v.) injections of drugs. In some animals, a third catheter was placed into the left femoral artery for intra-arterial (i.a.) volume loading. Catheters were filled with heparinized saline.

For experiments in conscious mice, the free catheter ends were tunnelled under the skin of the back to the level of the shoulder blades. Animals were then placed in individual cages and allowed at least 4 h to recover from surgery. Preliminary experiments showed that extending the postsurgery period to 24 h did not change the cardiovascular parameters (unpublished results; compare also baseline values for mean arterial pressure and heart rate in the present study with Altman et al. (1999) and Makaritsis et al. (1999)).

For experiments in anaesthetized mice, halothane anaesthesia was stopped and urethane was given i.v. (0.75 g kg−1).

Experimental protocol

At the end of surgery (anaesthetized mice) or of the recovery period (conscious mice), the arterial catheter was connected to a low-volume pressure transducer (Baxter, Bentley Laboratories Europe, Uden, The Netherlands) coupled to a bridge amplifier (Hugo Sachs Elektronik, Hugstetten, Germany). Heparin (40 IU/40 μl) was injected i.a. The arterial blood pressure was recorded continuously on a PC –computer, using a software for digital on-line acquisition and analysis of haemodynamic data (PolyView, Grass-Instruments, Astro-Med, Rodgau, Germany). Values for mean arterial pressure at each time point were the averages of values recorded over 10 heart beats (i.e., about 1 s). Heart rate was calculated manually by measuring the time duration of the 10 heart beats.

A 35–50 min stabilization period was allowed before any measurements were made. The spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate variability at rest were then estimated by measuring the mean arterial pressure and heart rate every second during 10 min. For each animal, the mean, variance, and coefficient of variation (CV) (the standard deviation as a percentage of the mean) were calculated from the 600 mean arterial pressure and heart rate values thus obtained. The variance and CV were taken as indexes of the spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate variability.

At the end of this 10 min period, the baseline mean arterial pressure and heart rate values (PRE) for the subsequent induction of baroreceptor reflexes were determined. Arterial blood (100 μl) was sampled immediately afterwards via the arterial catheter, for the determination of the plasma noradrenaline concentration. The baroreceptor reflex was activated 15 min after the PRE values by injection of a vasoactive drug or by volume loading (see below). The mean arterial pressure and heart rate were then evaluated every 30 s during the next 5 min.

Only one experiment was carried out in a single mouse. At the end of the experiment, animals were killed by an overdose of i.v. pentobarbitone.

Induction of baroreceptor reflexes

Baroreceptor reflexes were induced by three procedures: first, brief increases in blood pressure caused by i.v. injection of phenylephrine (50 μg kg−1); second, longer-lasting increases in blood pressure caused by i.a. volume loading (10 ml kg−1 of dextran solution infused within 2 min); third, brief decreases in blood pressure caused by i.v. injection of sodium nitroprusside (500 μg kg−1). The baroreceptor reflex gain was calculated in each experiment as the ratio of the maximal change in heart rate (beats min−1) over the maximal change in mean arterial pressure (mmHg).

The capability of the heart to increase its rate of beat was tested by i.v. administration of the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline (5 μg kg−1).

Determination of the plasma noradrenaline concentration

Arterial blood samples (100 μl) were immediately centrifugated (12,000 × g; 3 min; 0°C) to obtain 50 μl plasma. Noradrenaline in the plasma was determined by alumina chromatography, followed by HPLC and electrochemical detection, as previously described (Szabo et al., 2001).

Statistics

Means±s.e.m. of n experiments are given throughout. Differences between groups were evaluated with the nonparametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. P<0.05 was taken as the limit of statistical significance.

Drugs

Drugs were obtained from the following sources: (±)-isoprenaline bitartrate, (±)-phenylephrine hydrochloride, sodium nitroprusside and urethane from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany); dextran solution (Rheomacrodex® 10%) from Pharmacia (Erlangen, Germany); heparin (Heparin-Natrium Braun) from B. Braun Melsungen (Melsungen, Germany).

Isoprenaline, phenylephrine, sodium nitroprusside and urethane were dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered as i.v. bolus injections with a volume of 1 ml kg−1. Intravenous bolus injections of equivalent volumes of saline had no effect on the mean arterial pressure and heart rate (+2±1 and +3±3%, respectively; n=4 conscious α2A-KO mice). Doses refer to the salts.

Results

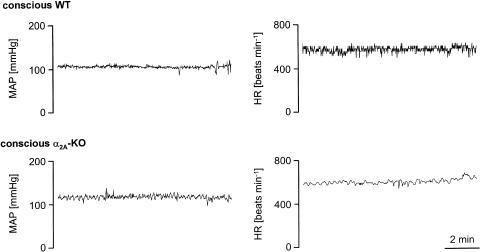

Figure 1 shows typical 10 min recordings of the mean arterial pressure and heart rate in conscious, unrestrained animals. In the α2A-KO mouse, the spontaneous fluctuations in mean arterial pressure are more frequent and more pronounced than in the WT mouse, whereas the spontaneous fluctuations in heart rate are less frequent and less pronounced. In fact, statistical evaluation showed that the two calculated indexes of spontaneous blood pressure variability, variance and CV, were significantly increased, whereas the indexes of spontaneous heart rate variability were significantly decreased, in the α2A-KO compared to WT animals (Table 1). Similar results were obtained in anaesthetized animals (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Typical 10 min recordings of mean arterial pressure and heart rate in a conscious WT and α2A-KO mouse. After a 35–50 min stabilization period, the MAP and HR were measured every second during the next 10 min. Note that the recording conditions were the same in the two animals. The tracings are representative of 23 (WT) and 24 (α2A-KO) animals.

Table 1.

Spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate variability at rest

| Mean arterial pressure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (mmHg) | Variance | CV (%) | |

| Conscious mice | ||||

| WT | 23 | 111±3 | 11.0±1.0 | 2.9±0.1 |

| α2A-KO | 24 | 118±2* | 20.3±3.0* | 3.7±0.3* |

| Anaesthetized mice | ||||

| WT | 6 | 97±8 | 5.7±1.0 | 2.6±0.4 |

| α2A-KO | 10 | 84±2 | 28.5±8.9* | 5.6±0.8* |

| Heart rate | ||||

| n | Mean (beats min−1) | Variance | CV (%) | |

| Conscious mice | ||||

| WT | 23 | 565±14 | 911.8±266.1 | 4.8±0.6 |

| α2A-KO | 24 | 596±9* | 354.2±54.4* | 3.0±0.2* |

| Anaesthetized mice | ||||

| WT | 6 | 510±37 | 700.4±202.2 | 5.0±0.8 |

| α2A-KO | 10 | 573±25 | 135.5±54.2* | 1.8±0.3* |

After a 35–50 min stabilization period, the mean arterial pressure and heart rate were measured every second during the next 10 min; the mean, variance, and coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated from the 600 values thus obtained. Values are means±s.e.m. of n experiments.

P<0.05 versus WT.

Baseline values for the subsequent induction of baroreflexes are given in Table 2. In awake α2A-KO mice, heart rate was increased compared to WT, but the mean arterial pressure was unchanged; the concentration of noradrenaline in plasma was also significantly greater in α2A-KO than in WT animals. In anaesthetized animals, baseline values for mean arterial pressure and heart rate were similar in the two strains; the plasma noradrenaline concentration tended to be higher in α2A-KO compared to WT mice.

Table 2.

Baseline mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and plasma noradrenaline concentration

| n | Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | Heart rate (beats min−1) | Plasma noradrenaline concentration (pg ml−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conscious mice | |||

| WT | |||

| 23 | 113±3 | 588±15 | 774±70 |

| α2A-KO | |||

| 24 | 118±3 | 625±13* | 1299±217* |

| Anaesthetized mice | |||

| WT | |||

| 6 | 93±6 | 519±37 | 1297±227 |

| α2A-KO | |||

| 10 | 83±3 | 569±25 | 2418±477 |

Initial (PRE) values for mean arterial pressure, heart rate and the plasma noradrenaline concentration were determined 15 min before the induction of baroreceptor reflexes, and are the means±s.e.m. of n experiments.

P<0.05 versus WT.

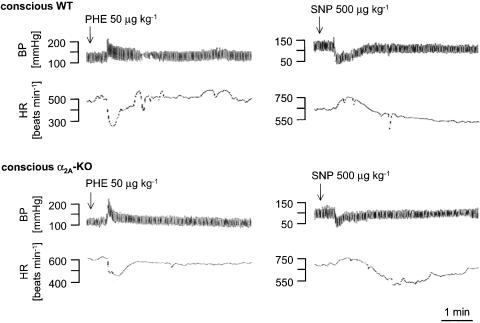

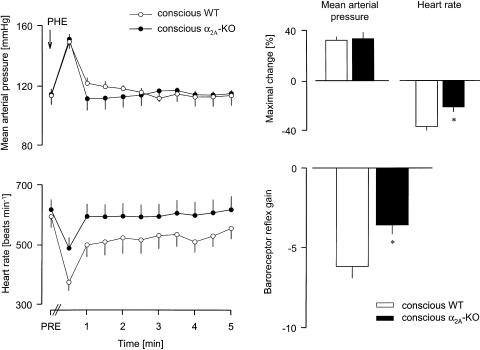

Bolus i.v. injection of 50 μg kg−1 phenylephrine to conscious WT and α2A-KO mice elicited very similar, brief increases in blood pressure (see Figure 2 for typical recordings and Figure 3). The reflex bradycardia in response to the blood pressure increase was much smaller in α2A-KO than in WT mice. The baroreceptor reflex gain was therefore decreased by 40% in the α2A-KO animals (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Typical BP and HR responses to phenylephrine or sodium nitroprusside injection in conscious WT and α2A-KO mice. PHE or SNP was injected i.v., as indicated by the arrows. The tracings are representative of six experiments each.

Figure 3.

Reflex bradycardia evoked by injection of phenylephrine in conscious WT and α2A-KO mice. After determination of baseline values (PRE), PHE 50 μg kg−1 was injected i.v., as indicated by the arrow. The MAP and HR were then evaluated every 30 s during the next 5 min. The baroreceptor reflex gain is the ratio of the maximal HR change over the maximal MAP change. Means±s.e.m. of six experiments each. *P<0.05 versus WT.

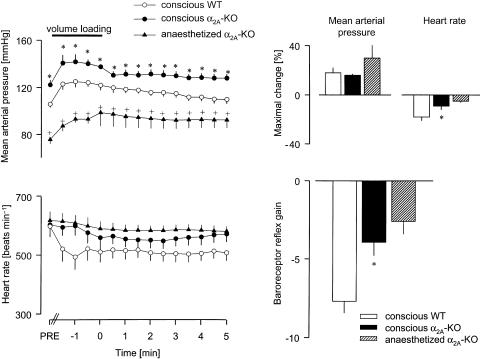

I.a. volume loading also produced very similar, but longer-lasting increases in mean arterial pressure in conscious animals of the two strains (Figure 4). In conscious WT mice, heart rate fell rapidly and greatly, and remained notably below the baseline (PRE) during the whole measurement period. In conscious α2A-KO mice, heart rate decreased slowly and significantly less and almost returned to its PRE value after 5 min; the baroreceptor reflex gain was markedly reduced in these animals, by 50% compared to WT (Figure 4). A similarly low baroreflex gain was obtained in volume-loaded anaesthethized α2A-KO mice (Figure 4; we did not carry out volume loading in anaesthetized WT mice).

Figure 4.

Reflex bradycardia evoked by volume loading in conscious WT and α2A-KO mice, and in anaesthetized α2A-KO mice. After determination of baseline values (PRE), dextran solution (10 ml kg−1 i.a.) was infused for 2 min, as indicated by the horizontal bar (from t=−2 to 0 min). The MAP and HR were then evaluated every 30 s from the beginning of infusion. The baroreceptor reflex gain is the ratio of the maximal HR change over the maximal MAP change. Means±s.e.m. of six (conscious WT and α2A-KO) and four (anaesthetized α2A-KO) experiments. *P<0.05 versus WT. +P< 0.05 versus conscious α2A-KO.

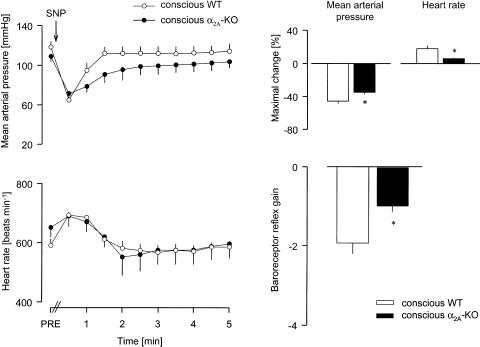

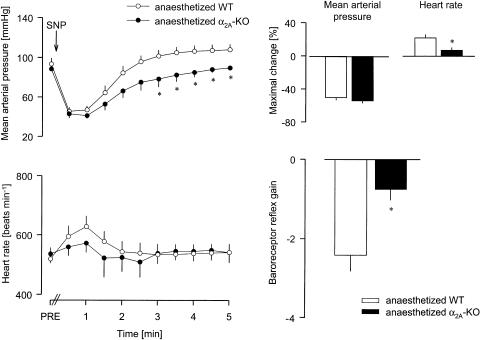

The acute hypotension induced by i.v. injection of sodium nitroprusside was slightly lower in conscious α2A-KO than conscious WT mice (see Figure 2 for typical recordings and Figure 5). The maximal tachycardic reflex response was much less in conscious α2A-KO mice, so that the baroreceptor reflex gain was decreased by 50% compared to WT (Figure 5). In anaesthetized WT and α2A-KO mice, i.v. injection of sodium nitroprusside elicited similar hypotension (Figure 6). Again, the reflex tachycardia was much smaller in the anaesthetized α2A-KO mice, and the baroreceptor reflex gain was reduced by 65% (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Reflex tachycardia evoked by injection of SNP in conscious WT and α2A-KO mice. After determination of baseline values (PRE), SNP 500 μg kg−1 was injected i.v., as indicated by the arrow. The MAP and HR were then evaluated every 30 s during the next 5 min. The baroreceptor reflex gain is the ratio of the maximal HR change over the maximal MAP change. Means±s.e.m. of six experiments each. *P<0.05 versus WT.

Figure 6.

Reflex tachycardia evoked by injection of SNP in anaesthetized WT and α2A-KO mice. After determination of baseline values (PRE), SNP 500 μg kg−1 was injected i.v., as indicated by the arrow. The MAP and HR were then evaluated every 30 s during the next 5 min. The baroreceptor reflex gain is the ratio of the maximal HR change over the maximal MAP change. Means±s.e.m. of six experiments each. * P<0.05 versus WT.

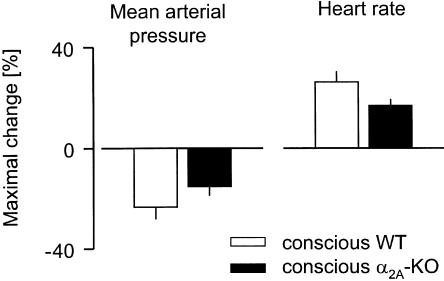

Isoprenaline produced blood pressure falls and heart rate increases in conscious animals of the two strains (Figure 7). Both the fall in blood pressure and the increase in heart rate tended to be smaller in α2A-KO mice, but the differences were not significant.

Figure 7.

Maximal changes in MAP and HR evoked by isoprenaline in conscious WT and α2A-KO mice. Isoprenaline 5 μg kg−1 was injected i.v. Means±s.e.m. of five (WT) and six (α2A-KO) experiments.

Discussion

As explained in Introduction, modulation of the baroreceptor reflex by central α2-adrenoceptors was first postulated more than 25 years ago (Haeusler, 1975). Subsequent studies suggested that activation of α2-adrenoceptors enhanced, whereas blockade of the receptors impaired, the baroreceptor reflex function (Huchet et al., 1981; 1983; Badoer et al., 1983; Kubo et al., 1990; Yamazaki & Ninomiya, 1993; but see Knuepfer et al., 1993). The present study using genetically modified mice lacking α2A-adrenoceptors confirms and extends these findings.

The efficacy of the baroreceptor reflex was first evaluated by means of the spontaneous blood pressure and heart rate oscillations in resting animals. Increases in spontaneous blood pressure variations together with decreases in spontaneous heart rate variations are indicative of an impairment or loss of baroreflexes (Parati et al., 1997; Pires et al., 2001; Souza Neto et al., 2003). In conscious α2A-KO mice, the spontaneous fluctuations in mean arterial pressure were more frequent and more pronounced than in conscious WT mice, and the two calculated indexes of spontaneous blood pressure variability were significantly increased. Simultaneously, the spontaneous fluctuations in heart rate were less frequent and less pronounced in conscious α2A-KO than in WT mice, and the two calculated indexes of spontaneous heart rate variability were significantly decreased. Similar differences between the two strains of mice were obtained when the animals were anaesthetized.

The efficacy of the baroreceptor reflex was secondly evaluated by measuring the baroreflex gain following evoked blood pressure changes. In conscious animals, deletion of α2A-adrenoceptors greatly attenuated the reflex bradycardia elicited by brief, pharmacologically induced, and longer-lasting, nonpharmacologically induced hypertension, as well as the reflex tachycardia following sodium nitroprusside-induced hypotension. In all experiments, the evoked changes in blood pressure were very similar in the two mouse strains. The calculated baroreceptor reflex gain was therefore decreased by 40–50% in α2A-KO mice compared to WT. Again, similar results were obtained in anaesthetized animals.

Overall, these results show that the efficacy of the baroreceptor reflex is attenuated in animals lacking the α2A-adrenoceptor gene. However, deletion of α2A-adrenoceptors has many consequences, of which at least three might attenuate the apparent baroreceptor function without an impairment of the reflex proper. First, lack of α2A-adrenoceptors may amplify the response to alerting or stressful stimuli, and, since stress inhibits the baroreflex (Dampney et al., 2002; Stauss, 2002), the sensitization to stress might be responsible for the changes observed in α2AKO mice. However, the baroreflex efficacy was impaired equally in awake α2A-KO mice and in anaesthetized α2A-KO mice, among which the latter are presumably less susceptible to stress. Moreover, i.v. injection per se had no effect on cardiovascular parameters, showing that at least this manipulation was not a stressful stimulus. Second, loss of α2A-adrenoceptors leads to higher resting sympathetic tone, as shown by the increased plasma noradrenaline levels and presumably also the higher baseline heart rates (Table 2 of the present study and Hein et al., 1999; Makaritsis et al., 1999). It seems unlikely, however, that these differences in baseline can explain the attenuated heart rate responses in α2A-KO mice. We also studied a group of Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) mice, a common laboratory strain; these animals had the same basal heart rate as the α2A-KO mice – higher than the WT mice – but their baroreflex gain was much greater than in the α2A-KO animals and as large as in the WT mice (Niederhoffer, Hein and Starke, data not shown). Third, loss of α2A-adrenoceptors is accompanied by downregulation of cardiac β-adrenoceptors (Altman et al., 1999), so a lower density of cardioexcitatory β-receptors in α2A-KO mice could explain the limited cardioacceleration in these animals after sodium nitroprusside hypotension. However, direct stimulation of cardiac β-adrenoceptors by isoprenaline elicited a 15–20% increase in heart rate in α2A-KO mice, a value only slightly (and not significantly) lower than in WT mice, and, more importantly, very similar to the maximal increase obtained after sodium nitroprusside in WT animals (+18%). Taken together, these considerations suggest that α2A-adrenoceptors in fact influence the baroreceptor reflex proper.

In previous studies, the exact role of α2-adrenoceptors in the baroreflex pathway has remained uncertain. Some authors concluded that they act only as modulatory receptors (see above). In contrast, Gurtu et al. (1982; 1983) and Sved et al. (1992) suggested that activation of α2-adrenoceptors – at least in the NTS and the nucleus ambiguus – is essential for the propagation of the baroreceptor reflex, that is, that the receptors are necessary constituents of the reflex arc. In the present experiments, the reflex was reduced but not abolished in mice lacking α2A-adrenoceptors. Radioligand-binding experiments in brain homogenates from α2A-KO mice showed that specific α2-adrenoceptor binding was reduced by 90%, and that the residual α2-adrenoceptors were not α2A (Altman et al., 1999). Thus, the use of genetically modified mice clearly demonstrates that α2A-adrenoceptors do not represent a necessary link in the reflex, and that these receptors modulate, rather than mediate, the baroreceptor reflex. However, participation of a non-α2A-adrenoceptor as modulatory receptor or as necessary link in the baroreflex remains possible.

Where are the α2A-adrenoceptors modulating the baroreceptor reflex located? For several reasons, the NTS and the RVLM are a likely possibility. The two areas receive substantial noradrenergic input, and experimentally induced increases and decreases in blood pressure correlate with reductions and elevations, respectively, of catecholamine release in these nuclei (Yamazaki & Ninomiya, 1993; Singewald & Philippu, 1996). Selective lesion of catecholaminergic terminals in the NTS or RVLM of rats impairs the baroreceptor reflex function (Snyder et al., 1978; Granata et al., 1983). Also, α2A-adrenoceptors are densely expressed in both nuclei (Scheinin et al., 1994; Tavares et al., 1996), and activation of these receptors seems to represent the main mechanism of the cardioinhibitory and hypotensive effect of clonidine-like α2-adrenoceptor agonists (Guyenet et al., 1995; Vayssettes-Courchay et al., 2002; Szabo, 2002). Finally, chronic impairment of baroreflexes leads to an upregulation of α2-adrenoceptors in the NTS and the RVLM, although the study did not discriminate between the different subtypes (El-Mas & Abdel-Rahman, 1997). However, in addition to the NTS and the RVLM, α2A-adrenoceptors are also expressed in the two parasympathetic motor nuclei, the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus, and in the caudal ventrolateral medulla, the relay between NTS and RVLM in the medullary baroreflex loop (Scheinin et al., 1994; Tavares et al., 1996), suggesting that the receptors may also operate there to modulate the baroreceptor reflex.

In conclusion, spontaneous blood pressure variability was increased, spontaneous heart rate variability was reduced, and heart rate reflex responses to evoked changes in blood pressure were attenuated in mice lacking the α2A-adrenoceptor gene. These results show that central α2A-adrenoceptors play a crucial role in the baroreceptor reflex, facilitating reflex responses to both baroreceptor loading and unloading. However, deletion of α2A-adrenoceptors did not totally abolish the baroreflexes, suggesting that these receptors are modulatory and not a conditio-sine-qua-non for the reflex.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ni 644/1-1 and SFB505) and the Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft, Freiburg. We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Claudia Schurr.

Abbreviations

- α2A-KO

α2A-adrenoceptor deficient

- CV

coefficient of variation

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarii

- PRE

initial absolute values (before induction of baroreceptor reflexes)

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata

- WT

wild type

References

- AICHER S.A., MILNER T.A., PICKEL V.M., REIS D.J. Anatomical substrates for baroreflex sympathoinhibition in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 2000;51:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTMAN J.D., TRENDELENBURG A.U., MACMILLAN L., BERNSTEIN D., LIMBIRD L., STARKE K., KOBILKA B.K., HEIN L. Abnormal regulation of the sympathetic nervous system in α2A-adrenergic receptor knockout mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:154–161. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BADOER E., HEAD G.A., KORNER P.I. Effects of intracisternal and intravenous alpha-methyldopa and clonidine on haemodynamics and baroreceptor-heart rate reflex properties in conscious rabbits. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1983;5:760–767. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYAJIAN C.L., LOUGHLIN S.E., LESLIE F.M. Anatomical evidence for alpha-2 adrenoceptor heterogeneity: differential autoradiographic distributions of [3H]rauwolscine and [3H]idazoxan in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987;241:1079–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMPNEY R.A.L. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol. Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMPNEY R.A.L., COLEMAN M.J., FONTES M.A.P., HIROOKA Y., HORIUCHI J., LI Y.W., POLSON J.W., POTTS P.D., TAGAWA T. Central mechanisms underlying short- and long-term regulation of the cardiovascular system. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2002;29:261–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EL-MAS M.M., ABDEL-RAHMAN A.A. Aortic barodenervation up-regulates α2-adrenoceptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius and rostral ventrolateral medulla: an autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1997;79:581–590. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00648-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDBERG M.R., ROBERTSON D. Yohimbine: a pharmacological probe for study of the α2-adrenoceptor. Pharmacol. Rev. 1983;35:143–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANATA A.R., RUGGIERO D.A., PARK D.H., JOH T.H., REIS D.J. Lesions of epinephrine neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla abolish the vasodepressor components of baroreflex and cardiopulmonary reflex. Hypertension. 1983;5 Suppl. V:V80–V84. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.6_pt_3.v80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURTU S., SHARMA D.K., SINHA J.N., BHARGAVA K.P. Evidence for involvement of α2-adrenoceptors in the nucleus ambiguous in baroreflex-mediated bradycardia. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1983;323:199–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00497663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURTU S., SINHA J.N., BHARGAVA K.P. Involvement of α2-adrenoceptors of nucleus tractus solitarius in baroreflex mediated bradycardia. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1982;321:38–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00586346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUYENET P.G., LYNCH K.R., ROSIN D.L., STORNETTA R.L., ALLEN A.M.α2-Adrenergic receptors rather than imidazoline binding sites mediate the sympatholytic effect of clonidine in the rostral ventrolateral medulla Ventral Brainstem Mechanisms and the Control of Respiration and Blood Pressure 1995New York, Basel and Hong-Kong: Marcel-Dekker; 319–358.ed. Trouth, C.O., Millis, R.M., Kiwull-Schöne, H.F. & Schläfke M.E. pp [Google Scholar]

- HAEUSLER G. Cardiovascular regulation by central adrenergic mechanisms and its alteration by hypotensive drugs. Circ. Res. 1975;36:223–232. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.6.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIN L. Transgenic models of α2-adrenergic receptor subtype function. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;142:161–185. doi: 10.1007/BFb0117493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIN L., ALTMAN J.D., KOBILKA B.K. Two functionally distinct α2-adrenergic receptors regulate sympathetic neurotransmission. Nature. 1999;402:181–184. doi: 10.1038/46040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUCHET A.M., CHELLY J., SCHMITT H. Role of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in the modulation of the baroreflex vagal bradycardia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1981;71:455–461. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUCHET A.M., DOURSOUT M.F., OSTERMANN G., CHELLY J., SCHMITT H. Possible role of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in the modulation of the sympathetic component of the baroreflex. Neuropharmacology. 1983;22:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(83)90196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNUEPFER M.M., MCCANN R.K., KAMALU L. Effects of cocaine on baroreflex control of heart rate in conscious rats. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1993;43:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90332-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUBO T., GOSHIMA Y., HATA H., MISU Y. Evidence that endogenous catecholamines are involved in α2-adrenoceptor-mediated modulation of the aortic baroreceptor reflex in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. Brain Res. 1990;526:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91238-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKARITSIS K.P., JOHNS C., GAVRAS I., ALTMAN J.D., HANDY D.E., BRESNAHAN M.R., GAVRAS H. Sympathoinhibitory function of the α2A-adrenergic receptor subtype. Hypertension. 1999;34:403–407. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARATI G., FRATTOLA A., DI RIENZO M., CASTIGLIONI P., MANCIA G. Broadband spectral analysis of blood pressure and heart rate variability in very elderly subjects. Hypertension. 1997;30:803–808. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.4.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIRES S.L.S., BARRES C., SASSARD J., JULIEN C. Renal blood flow dynamics and arterial pressure lability in the conscious rat. Hypertension. 2001;38:147–152. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSIN D.L., TALLEY E.M., LEE A., STORNETTA R.L., GAYLINN B.D., GUYENET P.G., LYNCH K.R. Distribution of α2C-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;372:135–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960812)372:1<135::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEININ M., LOMASNEY J.W., HAYDEN-HIXSON D.M., SCHAMBRA U.B., CARON M.G., LEFKOWITZ R.J., FREMEAU R.T. Distribution of α2-adrenergic receptor subtype gene expression in rat brain. Mol. Brain Res. 1994;21:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGEWALD N., PHILIPPU A. Involvement of biogenic amines and amino acids in the central regulation of cardiovascular homeostasis. TIPS. 1996;17:356–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER D.W., NATHAN M.A., REIS D.J. Chronic lability of arterial pressure produced by selective destruction of the catecholamine innervation of the nucleus tractus solitarii in the rat. Circ. Res. 1978;43:662–671. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUZA NETO E.P., NEIDECKER J., LEHOT J.J. To understand blood pressure and heart rate variability. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim. 2003;22:425–452. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(03)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAUSS H.M. Baroreceptor reflex function. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;283:R284–R286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00219.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SVED A.F., TSUKAMOTO K., SCHREIHOFER A.M. Stimulation of α2-adrenergic receptors in nucleus tractus solitarius is required for the baroreceptor reflex. Brain Res. 1992;576:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90693-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZABO B. Imidazoline antihypertensive drugs: a critical review on their mechanism of action. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;93:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZABO B., FRITZ T., WEDZONY K. Effects of imidazoline antihypertensive drugs on sympathetic tone and noradrenaline release in the prefrontal cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:295–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAVARES A., HANDY D.E., BOGDANOVA N.N., ROSENE D.L., GAVRAS H. Localization of α2A- and α2B-adrenergic receptor subtypes in brain. Hypertension. 1996;27:449–455. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAYSSETTES-COURCHAY C., BOUYSSET F., CORDI A., LAUBIE M., VERBEUREN T.J. Effects of medullary α2-adrenoceptor blockade in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;453:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAZAKI T., NINOMIYA I. Noradrenaline contributes to modulation of the carotid sinus baroreflex in the nucleus solitarii area in the rabbit. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1993;149:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]