Abstract

Resveratrol, an active ingredient of red wine extracts, has been shown to exhibit neuroprotective effects in several experimental models.

The present study evaluated the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against amyloid β(Aβ)-induced toxicity in cultured rat hippocampal cells and examined the role of the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway in this effect.

Pre-, co- and post-treatment with resveratrol significantly attenuated Aβ-induced cell death in a concentration-dependent manner, with a concentration of 25 μM being maximally effective.

Pretreatment (1 h) of hippocampal cells with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate, a PKC activator, at increasing concentrations (1–100 ng ml−1), resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in Aβ-induced toxicity, whereas the inactive 4α-phorbol had no effect.

Pretreatment (30 min) of hippocampal cells with GF 109203X (1 μM), a general PKC inhibitor, significantly attenuated the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol against Aβ-induced cell death.

Treatment of hippocampal cells with resveratrol (20 μM) also induced the phosphorylation of various isoforms of PKC leading to activation.

Taken together, the present results indicate that PKC is involved in the neuroprotective action of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity.

Keywords: Resveratrol, hippocampus, β-amyloid, signal transduction pathway, neuroprotection, red wine extracts

Introduction

Resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound found in juice and wine from dark-skinned grape cultivars, has been shown to have a neuroprotective role in various models, in vitro and in vivo (Chanvitayapongs et al., 1997; Draczynska-Lusiak et al., 1998; Virgili & Contestabile, 2000; Bastianetto et al., 2000; Karlsson et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001; Jang & Surh, 2001,2003; Gelinas & Martinoli, 2002; Sharma & Gupta, 2002; Sinha et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Nicolini et al., 2003; Russo et al., 2003). In particular, resveratrol has been shown to protect cultured neurons against amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) (Jang & Surh, 2003), a neurotoxic peptide that likely plays a critical role in the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (for a review, see Butterfield, 2002). However, the mechanism(s) involved in these neuroprotective effects remains to be fully established. Resveratrol is known to possess potent antioxidant activity (Miller & Rice-Evans, 1995) and it is generally assumed that its neuroprotective action is principally associated with this property (Bastianetto et al., 2000; Karlsson et al., 2000; Ishige et al., 2001; Sinha et al., 2002; Jang & Surh, 2003). In addition to its antioxidant effects, resveratrol may be acting by modulating intracellular signaling pathways (Miloso et al., 1999; Della Ragione et al., 2002; Nicolini et al., 2003; Jang & Surh, 2003).

One important intracellular signaling system is protein kinase C (PKC), a family of 12 serine/threonine kinases. Since PKC has been found to modulate cell viability resulting in the protection of various neuronal cells (Behrens et al., 1999; Dore et al., 1999; Xie et al., 2000; Maher 2001; Cordey et al., 2003), we investigated here if this pathway could be involved in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity.

Methods

Chemicals

Materials used for cell cultures were obtained from Gibco BRL (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). PKC sampler kit was purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, U.S.A.). Anti-phospho-PKC (pan) antibody, phospho-PKC antibody sampler kit, p42 MAP kinase (ERK2) antibody, p44 MAP kinase (ERK1) antibody and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). Donkey anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Hybond-C nitrocellulose membrane and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were from Amersham Biosciences (Baie d'Urfé, Québec, Canada). Resveratrol, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), poly-D-lysine and β-actin antibody (clone AC15) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Aβ25–35 was kindly provided by P. Gaudreau (CHUM, University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada). Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were obtained from American Peptide Co. (Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.). 4α-Phorbol-12,13-didecanoate (4α-phorbol) and GF 109203X were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.).

Primary hippocampal cell cultures

Pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (St-Constant, Quebec, Canada). Animal care was according to protocols and guidelines of the McGill University Animal Care Committee in accordance with regulations of the Canadian Council for Animal Care. Hippocampal neuronal cell cultures were prepared from hippocampi of fetuses at embryonic day 19–20 as described by Bastianetto et al. (1999). Briefly, hippocampi were dissected in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 15 mM HEPES, 10 U ml−1 penicillin and 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Tissues were collected and washed in HBSS four to five times and 0.25% (v v−1) trypsin was added for digestion at 37°C for 10 min. The digestion was stopped by the addition of fetal bovine serum at a final concentration of 10% (v v−1). After rinsing four to five times with HBSS, a cell suspension was obtained by repeated aspiration with a Pasteur pipette. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min to remove the HBSS, and were resuspended in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (2%, v v−1), L-glutamate (25 μM), 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin.

Cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine (10 μg ml−1) precoated 96-well plates (about 1 × 105 well−1) for cytotoxicity analysis and six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells well−1 for Western blot analysis. Cells were cultured at 37°C in 95% humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 until use. The initial medium was removed at day 3 and replaced with fresh medium. Cell cultures were routinely observed under phase-contrast inverted microscope.

Cell treatments

Cells grown in 96-well plates at day 6 were washed, and the medium was replaced with neurobasal medium containing no B27 for 2 h before treatment. Cultured cells were pre- (2 h), co- or post-treated (2 h) with resveratrol at various concentrations (0–40 μM), followed by exposure to various Aβ peptides (Aβ25–35, Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42) for 24 h. Prior to use, Aβ25–35, Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 were dissolved in sterilized distilled water and were aggregated at 37°C for 1, 72 and 72 h, respectively. To determine whether a signaling pathway is involved in the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol, a few signaling pathway-specific inhibitors were used, including GF 109203X, a general PKC inhibitor, PD98059, a selective mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor, and LY294002, a selective phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3-K) inhibitor. In addition, PMA, an activator of PKC (Nishizuka, 1992), and 4α-phorbol, as a negative control compared to PMA, were also used. These pathway-specific inhibitors, PMA and 4α-phorbol, were first dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in neurobasal medium as a 20 × working solution. Each pathway-specific inhibitors (5 μl) was added to cell culture 30 min before treatment with resveratrol at 20 μM and coadministrated with Aβ25–35 for a further 24 h. PMA at various concentrations and 4α-phorbol (100 ng ml−1) were added 1 h before administration of Aβ25–35. Control conditions were treated with the appropriate amount of vehicle, DMSO, at a final concentration of 0.1%, which had no effect on cell viability (data not shown). After these treatments, cell viability was assessed as described below.

For Western blot analysis, cells were grown to confluence in six-well plates. At day 6, the media was removed, and cells were washed twice in neurobasal medium containing no B27 and were then placed in the same medium 2 h before treatment. Resveratrol was dissolved in DMSO as a 1000 × stock solution and then diluted 10 times with neurobasal media as 100 × working solutions. Cell cultures in 1 ml medium in six-well plates in triplicates were added with 10 μl of the final solution containing resveratrol to give concentrations ranging from 5 to 40 μM. Synthetic Aβ25–35 was dissolved in distilled water at 2 mM and incubated for 1 h at 37°C before use. Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were dissolved in neurobasal medium and incubated for 4 days at 37°C before use. For time course experiments, cells were grown in the presence of resveratrol at a concentration of 20 μM for 5 to 60 min.

Cell viability assays

After these various treatments, cell viability was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as described by Bastianetto et al. (2000). Briefly, MTT was dissolved in HBSS at 5 mg ml−1, and 10 μl of the solution was added to each well of 96-well plates. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C, the medium was removed and 100 μl of 0.1 N HCl in isopropanol was added to solubilize the reaction product formazan by shaking for 5 min. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Ville St-Laurent, Québec, Canada). Cell viability of vehicle-treated control groups not exposed to either Aβ31–35 or resveratrol was defined as 100%. In addition, cell viability was evaluated by measuring the amount of cytoplasmic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium. Culture supernatants (50 μl) were collected from each well, and LDH activities were measured at 490 nm using a CytoTox96 nonradioactive assay kit (Promega, Madison, U.S.A.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. LDH activity in each experiment was calculated as percentage of control LDH in the culture medium exposed to Aβ-peptides in the absence of resveratrol, which was defined as 100%. Assays were repeated in three independent experiments, each performed in triplicates. The qualitative assessment of neuronal injury was examined by phase-contrast microscopy.

Western blot

Following treatments, media were removed and cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold HBSS. Cells were then put into 200 μl of lysis buffer that contained 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 μM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin and 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin. In order to maximally inhibit protein tyrosine phosphatases, the lysis buffer was prepared with an activated sodium orthovanadate. The stock solution of sodium orthovanadate (200 mM) was prepared and its pH was adjusted to 10.0. At pH 10.0, the solution turned yellow and was boiled until it became colorless. The solution was cooled to room temperature and its pH readjusted to 10.0. The solution was boiled again until it remained colorless and the pH stabilized at 10.0. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was stored as aliquots at –20°C. The activated sodium orthovanadate, aprotinin and leupeptin were added to the lysis buffer just prior to use. Cells were lysed on ice for 30 min with vortexing for 1 min at 10 min intervals. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove debris. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using bicinchoninic acid (Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.), with bovine serum albumin used as standards. After adjusting the concentrations, equal amounts of samples were added to appropriate amount of 6 × sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) sample buffer and shaken for 15 min. Samples were boiled for 5 min, and 10 μl of the samples was loaded onto NuPAGE 4–12% bis-tris electrophoresis gel (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Electrophoresis was run on a constant voltage at 160 V for ∼1.2 h and proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were analyzed as described in Zheng et al. (2002) with the appropriate antibodies: anti-phospho-PKC (pan) antibody (to detect PKC-α, -βI, -βII, -ζ, -ɛ, -η and -δ, phosphorylated at a carboxy-terminal residue homologous to Ser-660 of PKC-βII), PKC sampler kit (to detect PKC -α, -β, -γ, -δ, -ɛ, -η, -θ, -ι, -λ) and phospho-PKC antibody sampler kit (to detect phospho-PKC-α/βII, -μ, -δ, -ξ/λ, -θ). Appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 : 10,000) were used to detect the proteins of interest by enhanced chemiluminescnce. An aliquot of samples were loaded and probed with anti-β-actin antibody for detection of β-actin as a loading control. Films were scanned at 600 d.p.i. in transmittance mode using a UMAX scanner and the levels of PKC phosphorylation and PKC isoenzymes were assessed by densities of bands, which were quantified using a MCID program (Imaging Research Inc., St Catharines, Ontario, Canada) or the NIH Image program available at their web site (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image). The values of the band intensities were normalized with that of β-actin as internal standards. The levels of PKC phosphorylation, PKC isozymes of treated cultures were compared with those of untreated control cultures.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.m) from three or more independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was established by ANOVA followed by Student t-test using SPSS (v.10.1) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) or Microsoft Excel software. Statistical significance was established at P<0.05.

Results

Neuroprotective/neurorescuing effect of resveratrol against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity in rat hippocampal cell cultures

To establish that Aβ causes neuronal cell death, we performed cytotoxicity experiments using three different Aβ fragments namely Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40 and Aβ25–35, a synthetic toxic fragment of the amyloid protein. In initial experiments, rat hippocampal cells grown in serum-free neurobasal media containing B27 supplements at day 6 were treated with different concentrations of Aβ1–42 or Aβ1–40 for 24 h and then the cell viability was measured by colorimetric MTT assay. Aggregated Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 caused up to 40–60% cell death at concentrations ranging from 5 to 20 μM. Both soluble and aggregated Aβ25–35 (20 μM) induced similar toxic effects that were comparable to Aβ1–42 at 5 μM. Since it has been shown that Aβ25–35 and full-length Aβ1–42 can induce neuronal apoptosis by similar mechanisms (for a review, see Mattson, 1997), Aβ25–35 was used in all subsequent experiments.

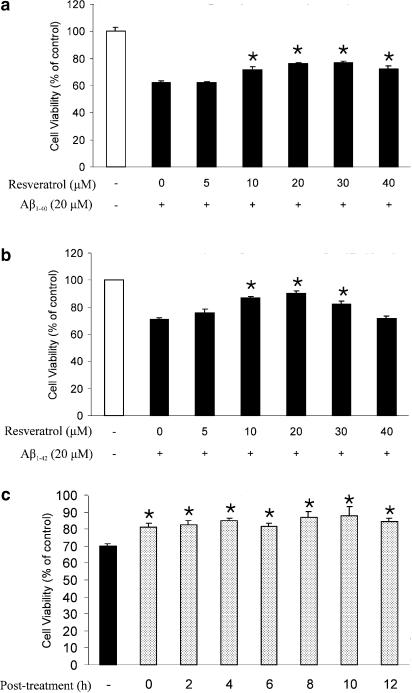

Based on recent literature (Miloso et al., 1999; Bastianetto et al., 2000; Nicolini et al., 2001), resveratrol is highly effective in maintaining cell viability at concentrations ranging between 1 and 50 μM. To examine the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity, rat cultured hippocampal cells were pre- (2 h), co- or post-treated (2 h) with resveratrol in the presence or absence of Aβ25–35 (20 μM) for 24 h. As shown in Figure 1a, viability of hippocampal neuronal cells exposed to Aβ25–35 (20 μM) for 24 h was reduced to 63.5±3.9% compared to that of vehicle-treated control groups. A pretreatment of hippocampal neuronal cells with resveratrol (15–40 μM) significantly reduced Aβ25–35-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, with a maximal effect (93%) obtained at 25 μM. The neuroprotective effect of resveratrol was also confirmed using the LDH assay (Figure 1b). Co- and post-treatment with resveratrol was neuroprotective but with a somewhat lower potency than seen following a pretreatment of the cells (Figure 1c and d). Similarly, a cotreatment with resveratrol showed similar neuroprotective effects against Aβ1–40 (Figure 2a) and Aβ1–42 (Figure 2b) toxicity in cultured hippocampal cells. Interestingly, resveratrol, in a dose-dependent manner, was also able to rescue hippocampal cells pre-exposed (0–12 h) to Aβ25–35 (Figure 2c). Resveratrol at the concentrations of up to 30 μM was tested alone for possible intrinsic cytotoxicity activity and showed no significant differences in cell survival compared to untreated control cells.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of resveratrol against Aβ25–35-induced cell death in hippocampal neurons. Cells were pretreated with resveratrol at various concentrations, 2 h before the addition of Aβ25–35 (20 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was assayed with MTT (a) and LDH (b). Cells were also cotreated (c) or post (2 h)-treated (d) with resveratrol. Percentage of cell viability was relative to vehicle-treated controls (white bars). Values represent mean±s.e.m of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicates. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by Student's t-test, compared to group that was treated with Aβ alone.

Figure 2.

Protective effects of resveratrol against Aβ1–40- and Aβ1–42-induced toxicity and its rescuing effect in hippocampal neurons. Cells were cotreated with resveratrol at various concentrations in the presence of Aβ1–40 (20 μM) (a) or Aβ1–42 (20 μM) (b) for 24 h. (c) Cells were also post-treated with resveratrol at the indicated time after addition of Aβ25–35 (20 μM). Cell viability was assayed with MTT. Percentage of cell viability was relative to vehicle-treated controls (white bars). Values represent mean±s.e.m of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicates. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by Student's t-test, compared to group that was treated with Aβ alone.

Changes in cell morphology were assessed by microscopic examination (Figure 3). Cultured hippocampal cells were treated without or with resveratrol in the absence or presence of Aβ25–35 at 20 μM for 24 h. Cells treated with vehicle (control) (Figure 3a) exhibited large vacuole-free cell bodies with elaborate networks of neurites. The synapse connections between neurons could be clearly seen. Exposure of cells to Aβ25–35 at 20 μM for 24 h resulted in some cell death and the less neurites (Figure 3b). These morphological changes were counteracted by resveratrol at 20 μM (Figure 3c, d).

Figure 3.

Microscopic analysis of resveratrol against Aβ25–35-induced cell death. Representative phase-contrast photomicrographs of primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons exposure for 24 h to (a) vehicle (0.1% DMSO); (b) Aβ25–35 (20 μM); (c) resveratrol (20 μM); and (d) cells pretreated with 20 μM resveratrol for 30 min prior to exposure to Aβ25–35 (20 μM). Scale bar=500 μm.

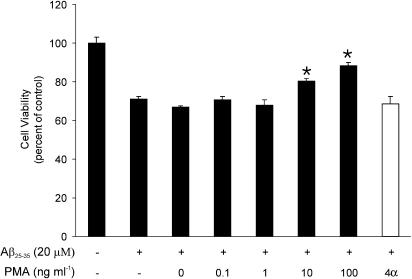

PKC activation is neuroprotective

To determine whether the activation of PKC pathways protects neurons against Aβ, we treated cell cultures with increasing concentrations of PMA 1 h before administration of Aβ25–35 and cells were then exposed to Aβ25–35 (20 μM) for 24 h. As shown in Figure 4, treatment with PMA resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in Aβ toxicity. However, 4α-phorbol, an inactive moiety, had no effect on Aβ toxicity.

Figure 4.

PMA reduces Aβ25–35-induced toxicity in dose-dependent manner. Cultures were treated with PMA (solid bars) at the indicated concentrations and 100 ng ml−1 4α-phorbol (open bar) 1 h before the addition of Aβ25–35. Cell viability was assessed 24 h later using the MTT assay. Data represent the mean (±s.e.m.) from a representative experiment (n=3). *P<0.05 relative to Aβ25–35 alone.

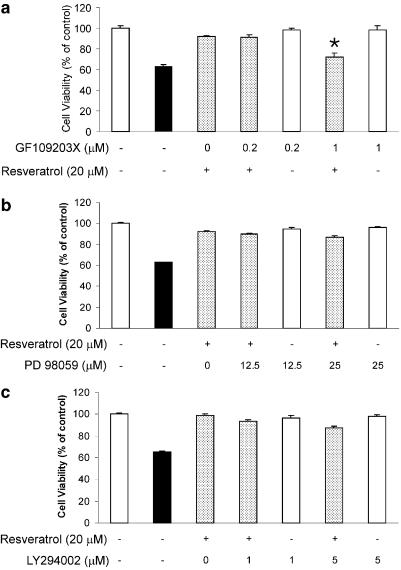

PKC inhibitor blocks the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol

To determine whether PKC could be involved in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol, a broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor, GF 109203X, was used. Treatment of GF 109203X (1 μM) 30 min prior to the addition of resveratrol significantly blocked the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against Aβ25–35-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 4a). By itself, GF 109203X (1 μM) did not affect cell viability (Figure 5a). Inhibitors of other intracellular signaling pathways such as PD98059 (25 μM, MAP kinase) (Figure 5b) and LY294002 (5 μM; PI3 kinase) (Figure 5c) failed to modulate the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against Aβ25–35-induced toxicity.

Figure 5.

Blockade by a PKC inhibitor of the protective effects of resveratrol against Aβ25–35-induced cell death in hippocampal neurons. Hippocampal neurons were pretreated with GF 109203X (a), PD98059 (b) and LY294002 (c) 30 min before adding resveratrol (20 μM) in the presence (shadow bars) or absence (white bars) of Aβ25–35 (20 μM). Treatment with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) alone (black bar). After 24 h, the viability of cells was measured using the MTT assay. Results are expressed as mean (%)±s.e.m. *P<0.01 by Student's t-test, compared to group that was treated with resveratrol (20 μM) in the presence of Aβ25–35 (20 μM).

Resveratrol activates PKC in primary hippocampal neurons

Since it has been previously shown that the activation by phosphorylation of PKC is closely associated with cell survival (Levites et al., 2002), we investigated next if resveratrol was able to promote phosphorylation, as assessed using an anti-phospho-PKC (pan) antibody. First, we determined the time course of PKC-induced phosphorylation by resveratrol. Phosphorylation of PKC showed a maximal increase 30 min after treatment with resveratrol and maintained till 60 min, and then returned to basal level at 120 min (Figure 6a). The phosphorylation of PKC was also induced by resveratrol in a dose-dependent manner, with maximal effects seen at 20–30 μM (Figure 6b), correlating to the optimal concentrations.

Figure 6.

Effects of resveratrol and Aβ25–35 on the phosphorylation of PKC in hippocampal cells. The phosphorylation of PKC was detected in cell lysates by Western blot using an anti-phospho-PKC (pan) antibody. (a) Hippocampal cells treated with resveratrol (20 μM) for the indicated times. (b) Hippocampal cells treated with resveratrol at various concentrations for 30 min. (c) Hippocampal cells treated with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) for the indicated times. (d) Hippocampal cells treated without or with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) in combinations with resveratrol at various concentrations for 30 min. Western blots (left) were probed with anti-phospho-PKC (pan), and bands from phospho-PKC immunoblots were quantified using an MCID program, normalized to β-actin, and represented graphically (right). Results are the mean±s.e. of three independent experiments. Student t-test: *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control.

Interestingly, the phosphorylation of PKC was decreased 60 min after addition of Aβ25–35 (20 μM) (Figure 6c). Moreover, the coadministration of resveratrol at its effective concentration of 20 μM and Aβ25–35 (20 μM) abolished the inhibitory effect of Aβ25–35 on the phosphorylation of PKC (Figure 6d).

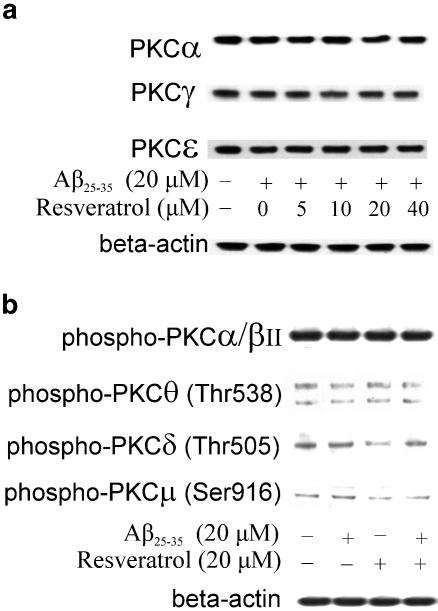

The possible preferential role of a given PKC isozyme in the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol was investigated next using a PKC sampler kit containing PKC isozyme-specific antibodies. The PKC family is composed of at least 12 isozymes, which are classically divided into conventional (α, βI, βII, γ), novel (δ, ɛ, η/Δ, θ, μ) and atypical (ζ, λ/ι) ones on the basis of their structure and cofactor requirements (Newton, 1997). It was shown that HT-22 cells, a subclone of a mouse hippocampal cell line, express multiple PKC isozymes, including the cPKC, PKCα, the nPKC, PKCδ and PKCɛ, and the aPKC, PKCζ and PKCλ, but not PKCβI, PKCβII, PKCγ or PKCθ (Maher, 2001). Our results revealed that cultured hippocampal cells expressed all PKCα, PKCβ, PKCγ, PKCδ, PKCɛ, PKCλ and PKCι, but not PKCθ. Resveratrol (5–40 μM) failed to significantly modulate the expression of PKCα, PKCγ and PKCɛ (Figure 7a), suggesting the unlikely involvement of these PKC isozymes in the neuroprotective action of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity. Moreover, using a phospho-PKC antibody sampler kit, we also detected a few phospho-PKC isozymes, including phospho-PKC-α/βII, -μ, -δ and -θ in control cultured neurons or following exposure to resveratrol at 20 μM in the presence or absence of Aβ25–35 (20 μM). As shown in Figure 7b, resveratrol did not affect the phosphorylation of PKC-α/βII, PKC-μ (Ser916) and PKC-θ (Thr538), but slightly decreased the phosphorylation of PKC-δ, suggesting the likely involvement of PKC-δ (Thr505) in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol. In addition, resveratrol (up to 40 μM) was unable to modulate the phosphorylation of either Akt kinase (Figure 8a) or ERK1 and ERK2 kinases (Figure 8b), suggesting specificity for its effects on PKC.

Figure 7.

Effects of resveratrol and Aβ25–35 on the PKC isoforms and the phosphorylation of PKC isoforms in hippocampal cells. PKC isoforms and the phosphorylation of PKC isoforms were detected in cell lysates by Western blot using a PKC sampler kit and an anti-phospho-PKC antibody sampler kit, respectively. (a) Western blots of PKC isoforms in hippocampal cells treated with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) and/or resveratrol at various concentrations for 30 min. (b) Western blots of phospho-PKC isoforms in hippocampal cells treated with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) and/or resveratrol (20 μM) for 30 min. Control was treated only with vehicle DMSO at a final concentration of 0.1%. Results are the representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Effects of resveratrol and Aβ25–35 on the phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 in hippocampal cells. (a) Western blots of phospho-ERK1/2 in hippocampal cells treated with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) and/or resveratrol at various concentrations for 30 min. (b) Western blots of phospho-Akt in hippocampal cells treated with Aβ25–35 (20 μM) and/or resveratrol at various concentrations for 30 min. Control was treated only with vehicle DMSO at a final concentration of 0.1%. Results are the representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, resveratrol, an active component from grapes, was shown to concentration-dependently protect against Aβ-induced toxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Resveratrol was active against various amyloid-related peptides including Aβ1–42, the most neurotoxic amyloid derivative present in the AD brain. Interestingly, resveratrol was able to block Aβ-induced toxicity not only following a pre- or co-treatment with the toxic peptide, but even to rescue neurons post-Aβ exposure. The mechanism(s) involved in the neuroprotective–neurorescuing effects of resveratrol likely include PKC as revealed by (a) the inhibitory action of GF 109203X, a potent, broadly acting PKC antagonist, on the protective effect of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity; (b) the activation of PKC by PMA which is neuroprotective and (c) the dose-dependent stimulation of PKC phosphorylation by resveratrol, and its reversal of Aβ-induced decrease in PKC phosphorylation. Moreover, resveratrol failed to modulate the phophorylation of Akt, ERK1 and ERK2 kinases demonstrating some specificity for its action on the PKC pathway.

Resveratrol was found to be neuroprotective against all three major neurotoxic amyloid peptides, namely Aβ25–35, Aβ1–40, and most importantly Aβ1–42. Interestingly, the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol was not only observed upon its pre- or co-treatment with the Aβs, but even if added up to 12 h postexposure to the toxic Aβ peptides. These results confirm and extend previous studies that mostly focused on the neuroprotective–neurorescuing properties of resveratrol against the neurotoxic effects of the 25–35 derivative (Jang & Surh, 2002). The neuroprotective–neurorescuing action of resveratrol especially against Aβ1–42-induced neurotoxicity is of particular interest as recent reports have suggested that changes in the Aβ1–40/Aβ1–42 ratio is critical for the onset and progression of the symptoms of AD (Hardy & Selkoe, 2002).

Several mechanisms may underlie resveratrol-induced neuroprotection against Aβ neurotoxicity (for a recent review, see Bastianetto & Quirion, 2001). For example, resveratrol has been shown to possess significant free-radical scavenging properties in a variety of cellular types (Chanvitayapongs et al., 1997; Subbaramaiah et al., 1998; Bastianetto et al., 2000; Karlsson et al., 2000; Sinha et al., 2002) and we have recently reported that it can act as an antioxidant against nitric oxide-induced toxicity (Bastianetto et al., 2000). Zhuang et al. (2003) also suggested that resveratrol was a potent activator of the heme oxydase system. Besides its antioxidant properties, various intracellular signaling mechanisms have been suggested to be involved, at least partly, in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol. For example, Miloso et al. (1999) have shown that resveratrol can induce the activation of the MAP kinases, ERK1 and ERK2 in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. However, we failed to observe a significant effect of resveratrol on the phosphorylation of MAP kinases as well as on that of Akt kinases in our model. In contrast, resveratrol potently stimulated the phosphorylation (leading to activation) of PKC, and reversed the inhibitory effect of Aβ peptides on PKC phosphorylation. Moreover, PMA, a potent and chronic activator of PKC, showed a dose-dependent reduction in Aβ-induced toxicity. In addition, GF 109203X, a well-known inhibitor of PKC, blocked the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity as well as its action on the phosphorylation of PKC. Taken together, our results suggest that the PKC pathway, but not MAP and Akt kinases, plays a major role in the neuroprotective–neurorescuing properties of resveratrol against Aβ-induced toxicity in hippocampal neurons. It is of interest to add that PKC has been shown to be implicated in cell survival and programmed cell death (Deacon et al., 1997; Maher, 2001; Levites et al., 2002).

In an attempt to determine the possible PKC isozymes involved in the neuroprotective action of resveratrol in our model, we examined its effects on the expression as well as phosphorylation of various isozymes. Several studies have suggested roles for PKCα, PKCɛ, PKCξ and PKCλ/ι in the suppression of programmed cell death (PCD) (Murray & Fields, 1997; Gubina et al., 1998; Whelan & Parker, 1998). However, our results showed that resveratrol failed to modulate the expression of PKCα, PKCγ and PKCɛ in cultured hippocampal neurons, suggesting that these isozymes are unlikely to be involved in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. Other isozymes expressed in hippocampal neurons including PKCβI, βII, δ, η, ι, λ should hence be investigated when proper tools such as highly selective antibodies will be available to establish their possible role in resveratrol-induced neuroprotection. It has been shown that PKCδ is associated with the promotion of PCD (Konishi et al., 1999). Furthermore, overexpression of PKCδ can induce (Ghayur et al., 1996) or potentiate (Konishi et al., 1999) PCD. Consistent with these results, our result that resveratrol resulted in decrease in the phosphorylation of PKCδ (Figure 7b) suggests that PKCδ is likely involved in the resveratrol-mediated protection.

Besides a role for PKC in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol, the possible involvement of novel signaling pathways and transcription factors should be considered especially as some very recent studies have shown, for example, that resveratrol can increase the expression of the transcription factor egr1 (Della Ragione et al., 2002) as well as protect against paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells (Nicolini et al., 2003). We are thus in the process of using global genomic and proteomic approaches (Marcotte et al., 2003) to potentially uncover new pathways and systems that could be involved in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against various toxic insults including the Aβ peptides.

The relevance of our findings to in vivo clinical situations remains to be demonstrated. However, some recent studies have revealed the potential neuroprotective beneficial action of moderate red wine intake against various neurological disorders including AD (Orgogozo et al., 1997; Leibovici et al., 1999) and stroke (Sinha et al., 2002) as well as in vivo animal models of these diseases (Russo et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2002). Future studies aiming at precisely understanding the cellular mechanisms involved in the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol could thus open new avenues for the treatment of these disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- Aβ

amyloid β-peptide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LY294002

2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PI3-K

phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase

- PCD

programmed cell death

- PD98059

2(2′-amino-3′-methoxyphenyl

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulfate

References

- BASTIANETTO S., RAMASSAMY C., POIRIER J., QUIRION R. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) protects hippocampal cells from oxidative stress-induced damage. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;66:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASTIANETTO S., RAMASSAMY C., DORE S., CHRISTEN Y., POIRIER J., QUIRION R. The Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) protects hippocampal neurons against cell death induced by beta-amyloid. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:1882–1890. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASTIANETTO S., QUIRION R. Resveratrol and red wine constituents: evaluation of their neuroprotective properties. Pharm. News. 2001;8:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- BASTIANETTO S., ZHENG W.H., QUIRION R. Neuroprotective abilities of resveratrol and other red wine constituents against nitric oxide-related toxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:711–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEHRENS M.M., STRASSER U., KOH J.Y., GWAG B.J., CHOI D.W. Prevention of neuronal apoptosis by phorbol ester-induced activation of protein kinase C: blockade of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Neuroscience. 1999;94:917–927. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTTERFIELD D.A. Amyloid beta-peptide (1–42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease brain. Free Radic. Res. 2002;36:1307–1313. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000049890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANVITAYAPONGS S., DRACZYNSKA-LUSIAK B., SUN A.Y. Amelioration of oxidative stress by antioxidants and resveratrol in PC12 cells. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1499–1502. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORDEY M., GUNDIMEDA U., GOPALAKRISHNA R., PIKE C.J. Estrogen activates protein kinase C in neurons: role in neuroprotection. J. Neurochem. 2003;84:1340–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEACON E.M., PONGRACZ J., GRIFFITHS G., LORD J.M. Isoenzymes of protein kinase C: differential involvement in apoptosis and pathogenesis. Mol. Pathol. 1997;50:124–131. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELLA RAGIONE F., CUCCIOLLA V., CRINITI V., INDACO S., BORRIELLO A., ZAPPIA V. Antioxidants induce different phenotypes by a distinct modulation of signal transduction. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DORE S., TAKAHASHI M., FERRIS C.D., ZAKHARY R., HESTER L.D., GUASTELLA D., SNYDER S.H. Bilirubin, formed by activation of heme oxygenase-2, protects neurons against oxidative stress injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 1999;96:2445–2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRACZYNSKA-LUSIAK B., DOUNG A., SUN A.Y. Oxidized lipoproteins may play a role in neuronal cell death in Alzheimer disease. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1998;33:139–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02870187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GELINAS S., MARTINOLI M.G. Neuroprotective effect of estradiol and phytoestrogens on MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in neuronal PC12 cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;70:90–96. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHAYUR T., HUGUNIN M., TALANIAN R.V., RATNOFSKY S., QUINLAN C., EMOTO Y., PANDEY P., DATTA R., HUANG Y., KHARBANDA S., ALLEN H., KAMEN R., WONG W., KUFE D. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE/CED 3-like protease induces characteristics of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2399–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUBINA E., RINAUDO M.S., SZALLASI Z., BLUMBERG P.M., MUFSON R.A. Overexpression of protein kinase C isoform epsilon but not delta in human interleukin-3-dependent cells suppresses apoptosis and induces bcl-2 expression. Blood. 1998;91:823–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDY J., SELKOE D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG S.S., TSAI M.C., CHIH C.L., HUNG L.M., TSAI S.K. Resveratrol reduction of infarct size in Long-Evans rats subjected to focal cerebral ischemia. Life Sci. 2001;69:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIGE K., SCHUBERT D., SAGARA Y. Flavonoids protect neuronal cells from oxidative stress by three distinct mechanisms. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:433–446. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANG J.H., SURH Y.J. Protective effects of resveratrol on hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. Mutat. Res. 2001;496:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(01)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANG J.H., SURH Y.J. Protective effects of resveratrol on β-amyloid-induced oxidative PC12 cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1100–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARLSSON J., EMGARD M., BRUNDIN P., BURKITT M.J. Trans-resveratrol protects embryonic mesencephalic cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide: electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping evidence for a radical scavenging mechanism. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:141–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONISHI H., MATSUZAKI H., TAKAISHI H., YAMAMOTO T., FUKUNAGA M., ONO Y., KIKKAWA U. Opposing effects of protein kinase C delta and protein kinase B alpha on H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis in CHO cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;264:840–846. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEIBOVICI D., RITCHIE K., LEDESERT B., TOUCHON J. The effects of wine and tobacco consumption on cognitive performance in the elderly: a longitudinal study of relative risk. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999;28:77–81. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVITES Y., AMIT T., YOUDIM M.B., MANDEL S. Involvement of protein kinase C activation and cell survival/cell cycle genes in green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin 3-gallate neuroprotective action. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30574–30580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAHER P. How protein kinase C activation protects nerve cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:2929–2938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-02929.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCOTTE E.R., SRIVASTAVA L.K., QUIRION R. cDNA microarray and proteomic approaches in the study of brain diseases: focus on schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2003;100:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTSON M.P. Cellular actions of beta-amyloid precursor protein and its soluble and fibrillogenic derivatives. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:1081–1132. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER N.J., RICE-EVANS C.A. Antioxidant activity of resveratrol in red wine. Clin. Chem. 1995;41:1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILOSO M., BERTELLI A.A., NICOLINI G., TREDICI G. Resveratrol-induced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases, ERK1 and ERK2, in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;264:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY N.R., FIELDS A.P. Atypical protein kinase C iota protects human leukemia cells against drug-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27521–27524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON A.C. Regulation of protein kinase C. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997;9:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOLINI G., RIGOLIO R., MILOSO M., BERTELLI A.A., TREDICI G. Anti-apoptotic effect of trans-resveratrol on paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;302:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOLINI G., RIGOLIO R., SCUTERI A., MILOSO M., SACCOMANNO D., CAVALETTI G., TREDICI G. Effect of trans-resveratrol on signal transduction pathways involved in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem. Int. 2003;42:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phosopholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORGOGOZO J.M., DARTIGUES J.F., LAFONT S., LETENNEUR L., COMMENGES D., SALAMON R., RENAUD S., BRETELER M.B. Wine consumption and dementia in the elderly: a prospective community study in the Bordeaux area. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 1997;153:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSO A., PALUMBO M., ALIANO C., LEMPEREUR L., SCOTO G., RENIS M. Red wine micronutrients as protective agents in Alzheimer-like induced insult. Life Sci. 2003;72:2369–2379. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA M., GUPTA Y.K. Chronic treatment with trans resveratrol prevents intracerebroventricular streptozotocin induced cognitive impairment and oxidative stress in rats. Life Sci. 2002;71:2489–2498. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINHA K., CHAUDHARY G., GUPTA Y.K. Protective effect of resveratrol against oxidative stress in middle cerebral artery occlusion model of stroke in rats. Life Sci. 2002;71:655–665. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUBBARAMAIAH K., CHUNG W.J., MICHALUART P., TELANG N., TANABE T., INOUE H., JANG M., PEZZUTO J.M., DANNENBERG A.J. Resveratrol inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription and activity in phorbol ester-treated human mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:21875–21882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIRGILI M., CONTESTABILE A. Partial neuroprotection of in vivo excitotoxic brain damage by chronic administration of the red wine antioxidant agent, trans-resveratrol in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;281:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Q., XU J., ROTTINGHAUS G.E., SIMONYI A., LUBAHN D., SUN G.Y., SUN A.Y. Resveratrol protects against global cerebral ischemic injury in gerbils. Brain Res. 2002;958:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHELAN R.D., PARKER P.J. Loss of protein kinase C function induces an apoptotic response. Oncogene. 1998;16:1939–1944. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE J., GUO Q., ZHU H., WOOTEN M.W., MATTSON M.P. Protein kinase C protects neural cells against apoptosis induced by amyloid β-peptide. Mol. Brain Res. 2000;82:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHENG W.H., KAR S., QUIRION R. Insulin-like growth factor-1-induced phosphorylation of transcription factor FKHRL1 is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt kinase and role of this pathway in insulin-like growth factor-1-induced survival of cultured hippocampal neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:225–233. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHUANG H., KIM Y.S., KOEHLER R.C., DORE S. Potential mechanism by which resveratrol, a red wine constituent, protects neurons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;993:276–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]