Abstract

Background

As in other eukaryotes, plant mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are composed of three classes of hierarchically organized protein kinases, namely MAPKKKs, MAPKKs, and MAPKs. These modules rapidly amplify and transduce extracellular signals into various appropriate intracellular responses. While extensive work has been conducted on the post-translational regulation of specific MAPKKs and MAPKs in various plant species, there has been no systematic investigation of the genomic organization and transcriptional regulation of these genes.

Results

Ten putative poplar MAPKK genes (PtMKKs) and 21 putative poplar MAPK genes (PtMPKs) have been identified and located within the poplar (Populus trichocarpa) genome. Analysis of exon-intron junctions and of intron phase inside the predicted coding region of each candidate gene has revealed high levels of conservation within and between phylogenetic groups. Expression profiles of all members of these two gene families were also analyzed in 17 different poplar organs, using gene-specific primers directed at the 3'-untranslated region of each candidate gene and real-time quantitative PCR. Most PtMKKs and PtMPKs were differentially expressed across this developmental series.

Conclusion

This analysis provides a complete survey of MAPKK and MAPK gene expression profiles in poplar, a large woody perennial plant, and thus complements the extensive expression profiling data available for the herbaceous annual Arabidopsis thaliana. The poplar genome is marked by extensive segmental and chromosomal duplications, and within both kinase families, some recently duplicated paralogous gene pairs often display markedly different patterns of expression, consistent with the rapid evolution of specialized protein functions in this highly adaptive species.

Background

Members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase family are involved in major signaling pathways in all eukaryotes [1]. These pathways, which are typically activated by intracellular or environmental cues, usually consist of three hierarchically organized protein kinases. The first component of this module, the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK), activates a downstream MAPK kinase (MAPKK) through double serine-threonine phosphorylation. The phosphorylated MAPKK then acts as a dual-specificity protein kinase to activate the third component of the pathway, i.e. MAPK, via phosphorylation of specific threonine and tyrosine residues in a T-X-Y motif located within the activation loop of the protein. At this point, activated MAPKs can modulate various cellular activities through activation of other protein kinases, or metabolic enzymes, or by phosphorylation of transcription factors and components of the cytoskeleton. Important links between MAPK activities and fundamental processes like cell proliferation/differentiation and defence responses have been established from extensive studies performed in human, mouse and yeast systems [2].

MAPK cascades are also present in plants [3-5], where they have been involved in a wide variety of phenomena, including plant responses to biotic, abiotic and oxidative challenges [6-9], hormone signaling [10-12], plant cytokinesis [13] and pollen development [14]. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes at least 60 MAPKKKs, 10 MAPKKs and 20 MAPKs [4] but most of these proteins have not been functionally characterized. The plant MAPKK and MAPK families have both diverged into four major groups (A, B, C and D). MAPKs belonging to groups A, B and C all possess a TEY motif in their activation loop, while members of group D harbor a TDY motif. The most extensively studied plant MAPKs are Arabidopsis AtMPK3 and AtMPK6, and their Nicotiana tabacum orthologs, NtWIPK and NtSIPK, respectively. These group A MAPKs have been involved in non-host disease resistance [15,16], gene-for-gene defence signal transduction [17,18], wounding response [19] and ethylene production [20,21]. They also appear to act as positive regulators of the hypersensitive response (HR) [22], a defence-related form of programmed cell death. In rice (Oryza sativa), several MAPKs have also been characterized and display similar stress response functions, as well as developmental regulation [23-25].

The cellular functions in which MAPKs participate are mainly dependent on their phosphorylation status. In single-celled organisms like yeast, post-translational mechanisms seem to account for most of the regulation of the MAPK cascades, with little evidence of transcriptional regulation. On the other hand, in multicellular eukaryotes, MAPK cascades regulation often occurs at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational levels [26]. In mammals, the duration of MAPK activation can depend on the nature of the stimulus, and these differences in the temporal pattern of activation can lead to distinct physiological responses in the cell [27]. This has also been demonstrated in tobacco, where transient activation of NtMEK2 (a stress-responsive MAPKK) and its downstream effector, NtSIPK, induces strong expression of defence-related genes, whereas sustained activation of the same proteins leads to the activation of NtWIPK and subsequent cell death [22]. Compartmentalization and organization of yeast and mammalian MAPK cascade components by scaffolding proteins [28,29]. can also contribute to signaling specificity [2]. For plants, there is no published data involving scaffolding proteins in MAPK signaling, but a recent report has described the formation of protein complexes that include stress responsive MAPKs [30]. Subcellular compartmentalization of MAPK components may also be critical to their function in plants, since treatment of Petroselinum crispum cells with a Phytophthora-derived elicitor resulted in the translocation of three cytosolic MAPKs to the nucleus, where they are thought to interact with transcription factors [31].

Regulation of MAPKs at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels can also play an important role in controlling the MAPK cascades function. Alternative splicing has been observed for the mammalian MAPK ERK1 [26,32], as well as for the Arabidopsis MAPKKK gene, ANP1 [33], and the rice MAPK gene, OsMPK5 [34]. Moreover, strong up-regulation in the expression of some plant MAPK genes is seen in response to stress, including tobacco NtWIPK [15], tomato LeMPK3 [8], alfalfa MsMMK4 [35] and rice OsBWMK1 [36] and OsMSRMK3 [25]. Finally, some plant MAPKs display organ-specific expression, suggesting that their function is spatially and/or temporally delimited. For example, the Petunia hybrida MAPK gene, PMEK 1, is preferentially expressed in reproductive female organs [37], while the tobacco MAPK gene Ntf4 (a close relative of the stress-responsive MAPK gene NtSIPK) is expressed only in certain organs such as pollen grains, developing embryos and mature embryos [38].

Transcriptional regulation of MAPK cascade components thus appears to provide an important level of control in plants, suggesting that systematic analysis of their transcriptional patterning in a given plant species should provide insight into potential biological functions of specific classes of these signaling components. The development of transcriptomic databases (microarray and others) in some model plant species such as Arabidopsis and rice has made it possible to track, in silico, the expression profile of a given MAPK gene. The recent availability of a genome sequence from Populus trichocarpa now opens up the possibility to investigate, based on transcriptional regulation, the possible involvement of specific MAPK gene family member(s) in organ development processes that are unique to woody species. In this paper, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the organ-specific expression patterns for all predicted poplar MAPK and MAPKK genes. Correlation of these data with structural analysis of both the MAPKK and the MAPK gene families also revealed distinct expression patterns within recently duplicated (paralogous) gene pairs, suggestive of rapid evolution of specialized signaling protein functions in this highly adaptable woody perennial.

Results

Genomic distribution of poplar MAPK and MAPKK genes

Previous analysis of the genome sequence of poplar (Populus trichocarpa) had identified robust gene models corresponding to all the MAPK (PtMPK) and MAPKK (PtMKK) family members [39]. With this information, we were able to obtain an overview of the chromosomal distribution of these important signaling components. PtMPK genes are distributed over 12 of the 19 poplar chromosomes (Figure 1). Chromosomes I and II both carry three divergent PtMPK genes, whereas chromosomes V, VII and X display two PtMPK genes each. The remaining poplar MAPK genes are unique with respect to their chromosomal location. PtMPK7 and PtMPK18 have not yet been assigned to any linkage group, and therefore remain positioned on their respective scaffolds. Interestingly, although there are numerous PtMPK paralogs displaying high levels of sequence similarity, they are distributed all across the genome and do not form clusters containing closely related genes as may have been expected if they originated from local duplication events. This pattern probably reflects the series of whole genome, chromosomal and large segmental duplication events that typify the poplar genome (G. Tuskan, personal communication).

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the scattered distribution of the poplar MAPK genes (PtMPKs) over the Populus trichocarpa genome. Twelve of the 19 poplar chromosomes are presented as vertical bars. In addition, two scaffolds containing a PtMPK gene are shown. PtMPK genes are represented by colored boxes and the color code presented here is also used in the other figures. Recent duplication events between paralogous genes are indicated using dotted lines.

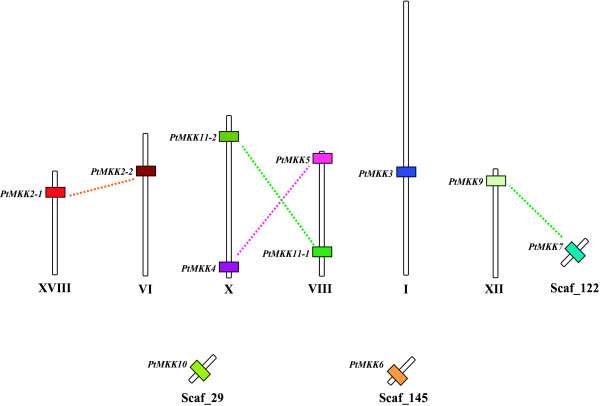

PtMKK genes also display a scattered genomic distribution (Figure 2) across six of the 19 poplar chromosomes, with three (PtMKK6, PtMKK7 and PtMKK10) of the 11 gene models located on unattributed scaffolds. Only chromosomes VIII and X contain more than one PtMKK gene.

Figure 2.

Schematic view of the scattered distribution of the poplar MAPKK genes (PtMKKs) over the Populus trichocarpa genome. Six of the 19 poplar chromosomes are presented as vertical bars. In addition, three scaffolds containing a PtMKK gene are shown. PtMKK genes are represented by colored boxes and the color code presented here is also used in the other figures. Recent duplication events between paralogous genes are indicated using dotted lines.

Exon and intron organization of poplar MAPK and MAPKK genes

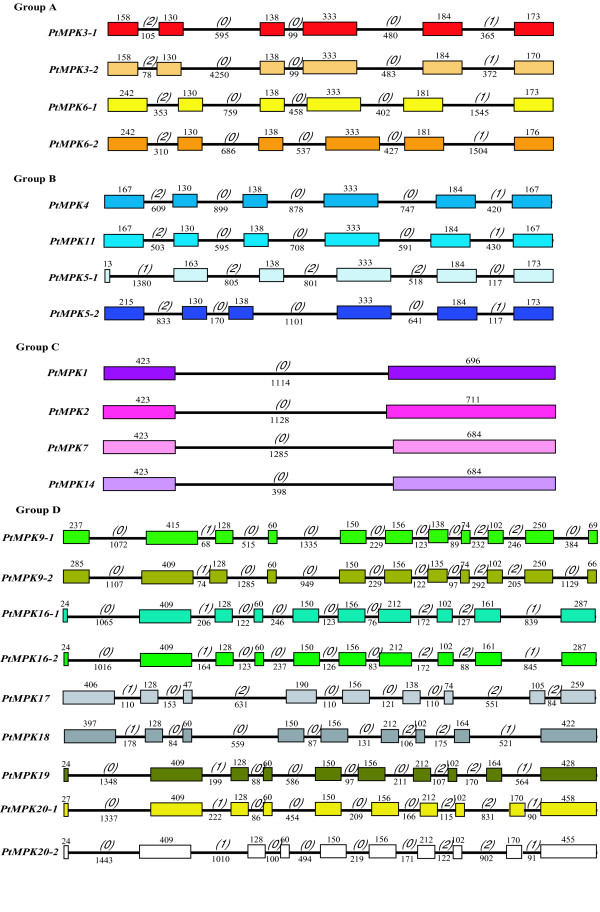

Analysis of the pattern of exon-intron junctions can provide important insights into the evolution of gene families. Therefore, we extracted data regarding predicted exon and intron distribution for the coding regions of all PtMPKs and PtMKKs (Figures 3 and 4) as well as for all Arabidopsis putative orthologs (AtMPKs, Figure 5 and AtMKKs, Figure 6). Group A PtMPKs exhibit a highly conserved distribution of exons and introns (Figure 3) consisting of six exons of conserved length, and five introns of conserved or variable sizes. PtMPKs belonging to group B also possess six exons, with lengths similar to those found in group A PtMPKs, while the associated introns vary in size between the different members of group B. Group C PtMPKs are each composed of only two exons with strictly conserved or very similar sizes. PtMPK14 is the only group C member with a shorter intron (398 vs ~ 1200 base pairs for the other three members).

Figure 3.

Intron and exon organization of poplar MAPK genes (PtMPKs). Introns and exons are represented by black lines and colored boxes respectively. The length in base pairs of each intron and exon is also indicated. Numbers between brackets correspond to the intron phase. PtMPKs have been grouped according to phylogenetic classification [39].

Figure 4.

Intron and exon organization of poplar MAPKK genes (PtMKKs). Introns and exons are represented by black lines and colored boxes respectively. The length in base pairs of each intron and exon is also indicated. Numbers between brackets correspond to the intron phase. PtMKKs have been grouped according to phylogenetic classification [39].

Figure 5.

Intron and exon organization of Arabidopsis MAPK genes (AtMPKs). Introns and exons are represented by black lines and colored boxes respectively. The length in base pairs of each intron and exon is also indicated. Numbers between brackets correspond to the intron phase. AtMPKs have been grouped according to phylogenetic classification [39].

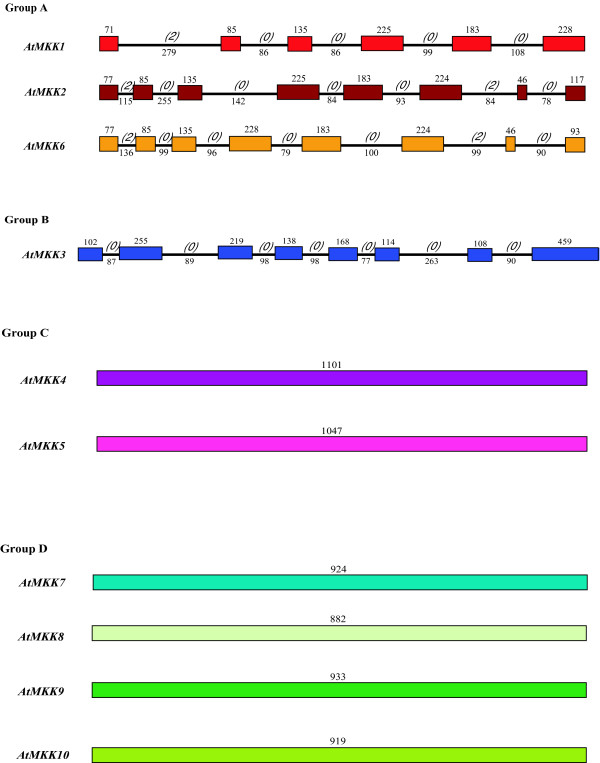

Figure 6.

Intron and exon organization of Arabidopsis MAPKK genes (AtMKKs). Introns and exons are represented by black lines and colored boxes respectively. The length in base pairs of each intron and exon is also indicated. Numbers between brackets correspond to the intron phase. AtMKKs have been grouped according to phylogenetic classification [39].

In contrast to these three highly conserved structural patterns, group D PtMPKs possess a complex distribution of exons and introns, including different pattern subsets within the same phylogenetic group. For instance, PtMPK9-1 and PtMPK9-2 are both composed of 11 exons, whereas PtMPK16-1, PtMPK16-2, PtMPK19, PtMPK20-1 and PtMPK20-2 all possess ten. Despite some modest differences in the length of particular exons, it is clear that the exon structural pattern is well conserved not only between close paralogs (e.g. PtMPK16-1 and PtMPK16-2), but also between group D PtMPKs that apparently diverged following earlier duplication events (e.g., PtMPK16-1 and PtMPK19). These same patterns are also found in the Arabidopsis MPK gene family with the exception of group B MPKs, which display three different patterns of exon-intron distribution (Figure 5).

The MKK genes display two strikingly different structural patterns in both poplar and Arabidopsis (Figures 4 and 6). Members of group C and D MKKs have a completely intronless configuration, whereas the group B MKK3s and all group A MKKs possess numerous exon and intron junctions. In poplar, PtMKK2-1, PtMKK2-2 and PtMKK6 show quite strong exon length conservation, with the exception of an additional 17 base pairs exon in PtMKK2-1. PtMKK3, on the other hand, has a completely unique exonic structure, consistent with both its evolutionary distinctiveness [39] and the presence of an unusual C-terminal NTF2 domain that is not found in any other MKK group.

Intron phase (i.e., the position of an intron within a codon; phase 0 when lying before the first base, phase 1 when lying after the first base and phase 2 when lying after the second base) was also assessed for all PtMPK and PtMKK gene models (Figures 3 and 4), as well as for all AtMPK and AtMKK gene models (Figures 5 and 6). For both PtMPKs (58%) and PtMKKs (73%), the majority of introns are within phase 0, while 23% of introns found in both poplar protein kinase families are within phase 2. Phase 1 introns represent 19% of all PtMPKs introns and only 4% of all PtMKKs introns. For Arabidopsis, similar numbers are found (Figures 5 and 6), except that there are no phase 1 introns predicted within AtMKK genes.

The association of two adjacent introns in eukaryotic genes can be in any of nine different intron phase combinations, leading to two classes of exons: symmetric exons (0-0), (1-1), (2-2) and asymmetric exons (0-1), (0-2), (1-0), (1-2), (2-0), (2-1). For poplar MPKs, 51% of all exons are symmetric and the great majority of these are (0-0) exons (79%). A similar picture is found in Arabidopsis, where 54% of AtMPKs exons are symmetric. Once again the majority of these are (0-0) exons (85%). No symmetric exons harboring the (1-1) configuration are found in any of the poplar or Arabidopsis MPK gene models. For the PtMKK and AtMKK gene families, we respectively found 58% and 68% of symmetric exons and for both species, all of these symmetric exons are in the (0-0) configuration. For both plants, the most frequent asymmetric exons found in MPKs and MKKs are those belonging to the (0-1), (0-2) and (2-0) configurations.

Real-time quantitative PCR data normalization and general considerations

The real-time, fluorescence-based reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RTqPCR) technique has become a method of choice because of its wide dynamic range, sensitivity and robust quantification of mRNA levels. In contrast to microarray profiling, transcript accumulation (TA) of closely-related gene members can also be easily discriminated in RTqPCR by using oligonucleotide primers specific to unique gene signatures. Such comparisons are only valid, however, if the chosen primer sets display comparable efficiencies in their ability to amplify targeted amplicons. We therefore tested all the selected primer sets against genomic DNA from three different genetic backgrounds, namely Populus trichocarpa (Nisqually-1), Populus trichocarpa X Populus deltoides (H11-11) and Populus deltoides (ST-70). In these assays, most primer sets yielded a very similar Ct value (around 21 for most genes) across the three different genetic backgrounds (see additional file 1). This indicates that these primer pairs can equally hybridize to the P. trichocarpa alleles in the Nisqually-1 background, to the P. deltoides alleles in the ST-70 background and most importantly to both the P. trichocarpa and the P. deltoides alleles in the H11-11 hybrid, which was used in this study to monitor PtMPK and PtMKK expression profiles. On the other hand, primer pairs specific for PtMPK2, PtMPK4, PtMPK9-2, PtMPK16-2, PtMKK4 and PtMKK7 all display higher Ct values in the P. deltoides background. This reflects that these gene specific primer pairs preferentially hybridize to the P. trichocarpa allele in the hybrid genotype, and that TA obtained on cDNA (see below) might slightly underestimate the actual level of expression since the P. deltoides allelic contribution is not perfectly captured. This observation could be related to lower primer set efficiency, resulting from polymorphism within the 3'UTR region of the different alleles. Nevertheless, melting curve and gel electrophoresis analysis confirmed single product amplification for all respective MPKs and MKKs in the three poplar genotypes (data not shown). Moreover, within one particular genetic background, the steady Ct value obtained for the different MPKs and MKKs confirmed that for a constant number of target sequences (e.g., 5 ng of DNA), each primer set gave a similar Ct value (see additional file 1). This clearly demonstrates the similar efficiencies of the various primer sets used in this study, and allows direct gene-to-gene comparisons of the levels of expression detected in the various organs sampled.

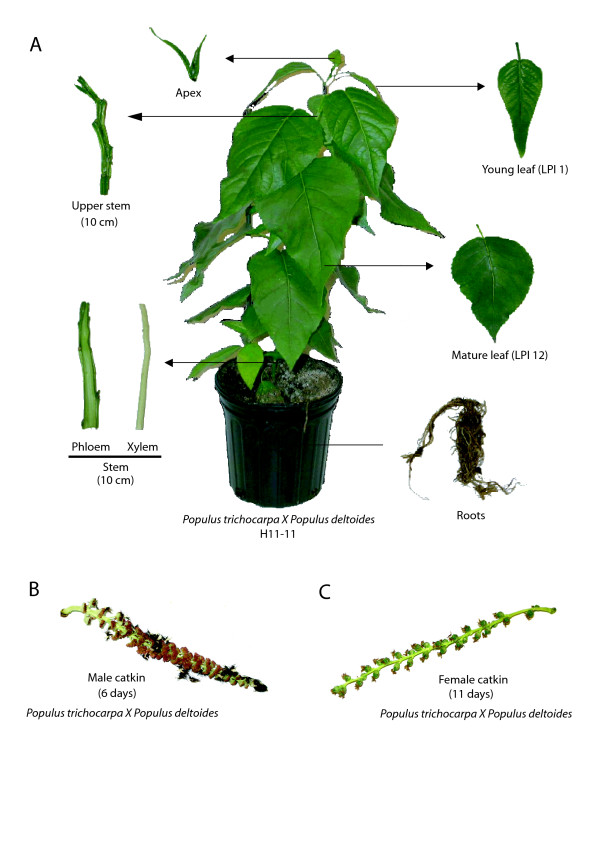

Finally, the use of internal standard candidate genes that display relatively stable expression over time and between tissues or organs allows sample-to-sample normalization of the RTqPCR expression data. In the present study, the use of RTqPCR primers specific for a cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (cdc2) gene revealed generally consistent levels of cdc2 TA in different organs from poplar (Figure 7A, B, C), with less than two-fold variation observed across most vegetative organs, and in suspension-cultured cells (Figure 8). Slightly higher transcript abundance of cdc2 was detected in actively growing organs, such as floral and foliar buds, where CDC2 is likely involved in cell-cycle progression [40,41]. Therefore, cdc2 expression levels provided a good normalization baseline. In addition, since Actin 2 (Act2) has been stated to be a good internal control gene for RTqPCR studies across various poplar organs [42], we have used this candidate as housekeeping gene. TA for Act2 proved to be quite stable across most organs, with a maximum five-fold increase from mature leaf to upper stem (Figure 8). This level of variation seems relatively low considering the wide diversity of tissues tested in our survey (from meristematic organs such as buds to mature leaves). Moreover, our results revealed that two poplar MAPKs (PtMPK6-1/6-2) display quite constant TA in all assayed organs (Figure 8). The highest TA was detected in the female floral bud sample, but this level of expression represents only a one-fold increase in comparison to the average TA in all organs. Finally, PtMKK2-2 was also detected at low but constant levels in all tested organs. The respective TA levels for cdc2, Act2, PtMPK6-1, PtMPK6-2 and PtMKK2-2 across many different organ types provide confirmation that an appropriate and consistent dosage of cDNA was used in the various RTqPCR reactions. In our analysis, TA levels corresponding to <100 transcript molecules per ng total RNA were scored as 'very low', values of 100–400 as 'moderate', values >400 as 'high', and values >1000 as 'very high'. Levels <10 were treated as effectively zero.

Figure 7.

Illustration of some of the harvested poplar organs used in this study. (A) P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides; H11-11 hybrid clone at PI 16 stage.(B) Harvested male catkin from cut branches of 10-year-old field-grown trees (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides). (C) Harvested female catkin from cut branches of 10-year-old field-grown trees (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides).

Figure 8.

Steady-state transcript accumulation for cdc2, Act2 and three kinase genes throughout the surveyed organs (indicated at the bottom of the figure). After determination of RTqPCR primers efficiency and generation of standard curves, RTqPCR analysis was performed for cdc2, Act2, and for two poplar MPKs as well as for one poplar MKK. Twelve nanograms of cDNA were used in each RTqPCR reaction. Results are expressed in number of specific transcripts per ng of total RNA. Values represent the mean of six independent reactions (two repeats for each of three independent samples). Cts were determined using single fluorescent readings that were taken after each cycle.

Poplar MAPK and MAPKK gene expression patterns

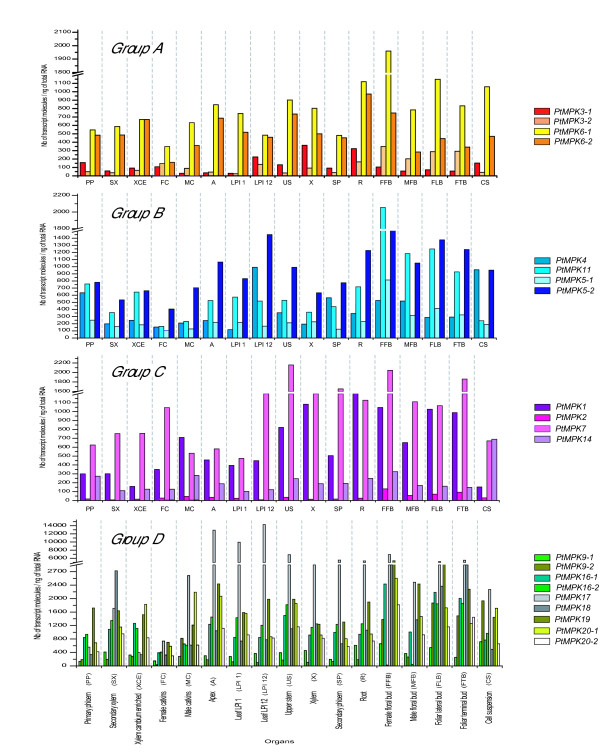

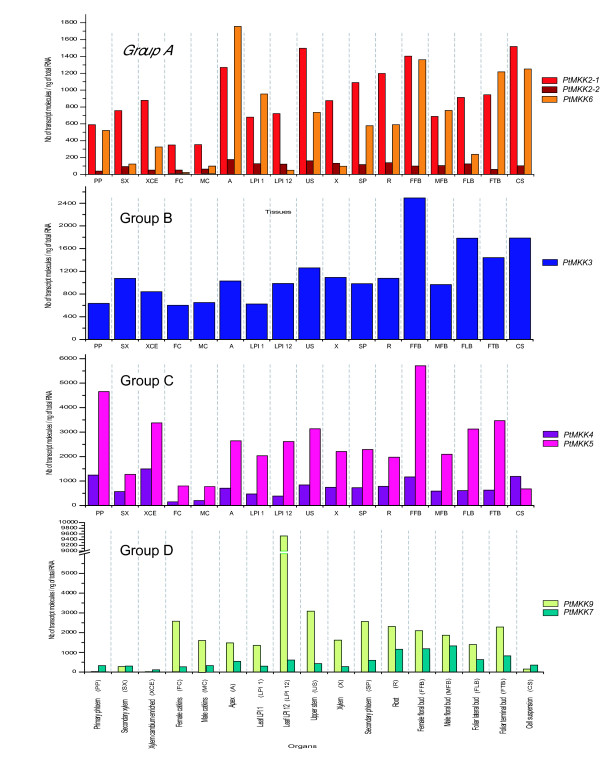

Virtually all PtMPKs and PtMKKs are expressed in all organs analyzed, but their level of expression varies considerably. Regardless of the phylogenetic groups or organs examined, the TA for PtMPKs generally fluctuates between moderate to very high levels (See additional file 2). Members of group D MPKs show TA levels of ~1500 transcript molecules per ng of total RNA, while members of the group A, B and C MPKs show lower levels, around 400–600. For the PtMKK gene family, the most highly expressed members are those belonging to group C (TA >1600, see additional file 3). Group B and D MKK genes have similar levels of TA (~1100–1600). Finally, group A MKK genes are the most weakly expressed, with on average 550 transcript molecules per ng of total RNA.

MAPKs

Group A MPKs

The most extensively studied plant MAPKs belong to Group A which, in Arabidopsis, consists of three members, AtMPK3, AtMPK6 and AtMPK10 [4]. No direct putative ortholog of AtMPK10 has been detected in the poplar genome, but phylogenetic analysis [39] revealed the presence of two closely-related poplar presumed orthologs for the defense-related genes AtMPK3 (PtMPK3-1 and 3-2) and AtMPK6 (PtMPK6-1 and 6-2). In most organs, the expression of both PtMPK3-1 and 3-2 is lower than that of PtMPK6-1 and 6-2 (Figure 9; see additional file 2). PtMPK3-1 is relatively strongly expressed in roots and xylem, in comparison to other samples. In most organs PtMPK3-1 tends to be slightly more expressed than PtMPK3-2. However, this pattern is reversed in the four types of buds (male and female floral buds, lateral and terminal foliar buds) as well as in both types of catkins. PtMPK6-1 and 6-2 both show similar expression profiles across many organs, but TA for PtMPK6-1 becomes slightly more pronounced than that of its paralog in all four types of buds, in both types of catkins and in suspension-cultured cells.

Figure 9.

Steady-state transcript accumulation for all members of the four phylogenetic groups of PtMPK genes. After determination of RTqPCR primers efficiency and generation of standard curves, RTqPCR analysis was performed for each poplar MAPK gene. Twelve nanograms of cDNA were used in each RTqPCR reaction. Results are expressed in number of specific transcripts per ng of total RNA. Values represent the mean of six independent reactions (two repeats for each of three independent samples). Cts were determined using single fluorescent readings that were taken after each cycle.

Group B MPKs

There is less information on the biological roles of the other MAPK groups in plants, although some reports have suggested the potential involvement of group B MPK genes in response to environmental stresses as well as in cell development [4]. In poplar, PtMPK11 and PtMPK5-2, the most highly expressed of the four group B MAPK genes, are particularly actively transcribed in male and female floral buds (Figure 9). By contrast, the paralogous PtMPK5-1 gene shows the lowest level of TA within this group.

Group C MPKs

Among the group C MPKs, it has been reported that the tobacco Ntf3 gene is expressed in pollen [43] and that the Arabidopsis AtMPK7 gene has circadian rhythm-regulated patterns of expression [44]. The most highly expressed of the four poplar group C MPK genes is PtMPK7, with elevated TA levels detected in female catkin, buds, phloem, xylem, mature leaves (LPI 12) and roots (Figure 9). This gene is also differentially expressed in particular developmental stages of specific organs, with more abundant transcripts detected in floral buds (male and female) than in either type of catkin. A similar situation is observed for leaves, where PtMPK7 TA is more pronounced in mature leaves than in young leaves. This is similar to what has been reported for the rice putative ortholog OsMAPK4 (now annotated as OsMPK7 [39]), whose expression is higher in mature leaves than in young leaves [45].

Group D MPKs

The group D MPKs represent the largest group of MPKs in poplar, as they do in Arabidopsis and rice [4,39]. In rice and alfalfa (Medicago sativa), two group D MAPK genes (OsBMWK1 and MsTDY1) are induced transcriptionally by pathogen challenge and wounding, respectively [36,46] Activated OsBMWK1 (now annotated as OsMPK17-1 [39]) has also been shown to phosphorylate a transcription factor that binds a cis-acting element in the promoter of defence-related genes [47].

In poplar, PtMPK17 is the most highly expressed of the group D MPK genes and, indeed, it is the most highly expressed among all the MPK and MKK genes (Figure 9). On the other hand, the most weakly expressed group D MPK genes, PtMPK9-1 and PtMPK9-2, display low transcript levels in all organs with the noteworthy exception of all types of buds, and cell suspensions. As previously observed in other MPK groups, some members of the group D MPK genes seem to represent the paralogous products of recent genomic duplication events, since they possess a very high degree of sequence similarity, are located on different chromosomes and have only one direct putative ortholog in Arabidopsis [39]. PtMPK16-1 and PtMPK16-2 are particularly interesting paralogs, since they have very similar expression profiles in most organs, including male and female catkins. On the other hand, PtMPK16-1 is strongly expressed in male and female floral buds, whereas expression of PtMPK16-2 is barely detectable in these reproductive organs.

MAPKKs

Group A MKKs

In other plant species, some group A MKKs appear to be functionally associated with group B MPKs [48,49] These phosphotransfer relationships have been involved in responses to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis, and in cell development in tobacco. As in Arabidopsis, there are three group A MKK genes found in poplar. PtMKK2-2 shows low but constant levels of TA in all tested organs (Figure 10; see additional file 3), while the paralogous PtMKK2-1 is much more highly expressed. Higher expression of PtMKK6, on the other hand, seems to be associated with proliferating organs such as apex, floral and terminal buds, cell suspensions, and young leaves (LPI 1), with a 25-fold decrease in PtMKK6 expression levels observed along the foliar developmental gradient from young to mature leaves. Interestingly, the presumed Arabidopsis and tobacco orthologs of PtMKK6 have been involved in regulation of cytokinesis and cell division [13], suggesting that this protein may play an analogous role in poplar tissues.

Figure 10.

Steady-state transcript accumulation for all members of the four phylogenetic groups of PtMKK genes. After determination of RTqPCR primers efficiency and generation of standard curves, RTqPCR analysis was performed for each poplar MAPKK gene. Twelve nanograms of cDNA were used in each RTqPCR reaction. Results are expressed in number of specific transcripts per ng of total RNA. Values represent the mean of six independent reactions (two repeats for each of three independent samples). Cts were determined using single fluorescent readings that were taken after each cycle.

Group B MKKs

Group B MKKs in poplar are represented by a single gene, PtMKK3. This is also seen in Arabidopsis (AtMKK3) and rice (OsMKK3) [39]. MKKs of this class are unique in encoding a characteristic MKK protein kinase domain fused in C-terminal to a putative nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) domain [4]. No biological functions have yet been assigned to plant MKK3s, but PtMKK3 has moderate to relatively high expression levels across all organs (TA between 400 to 2600), with the highest levels detected in female floral buds, lateral foliar buds and cell suspensions (Figure 10).

Group C MKKs

Among the plant MKKs, attention has been largely focused on those found in group C because of their demonstrated roles in stress signaling. Ectopic expression of constitutively-activated versions of the tobacco NtMEK2 protein, and of other group C MKKs, has been used to demonstrate that they are capable of phosphorylating and thus activating stress-responsive Group A MPKs [50-52]. Poplar possesses two group C MKKs, PtMKK4 and PtMKK5, both of which are expressed. Of the two, PtMKK5 shows higher TA in most organs, while the expression of PtMKK4 only predominates in suspension-cultured cells (Figure 10).

Group D MKKs

Limited functional information is available for group D MKKs, of which there are five encoded representatives in the poplar genome (PtMKK7, PtMKK9, PtMKK10, PtMKK11-1 and PtMKK11-2). However, our RTqPCR analysis suggests that only PtMKK7 and PtMKK9 are clearly expressed (Figure 10). The other three genes may therefore be pseudogenes, or be expressed only under circumstances that were not tested in our survey. The pseudogene hypothesis is also supported by the observation of structural differences in normally conserved motifs within the predicted PtMKK10, 11-1 and 11-2 protein kinase domains, and by the apparent absence of expression data for the Arabidopsis (AtMKK10) and rice (OsMKK10-1/10-2) putative orthologs [39].

While both PtMKK7 and PtMKK9 expression could be detected, the patterns differ significantly across organs and developmental stages (Figure 10). PtMKK9 expression is generally more pronounced except in secondary xylem, cell suspensions, primary phloem and xylem cambium-enriched, where PtMKK7 predominates. PtMKK9 is particularly highly expressed in mature leaves (LPI 12), where it reaches close to 10 000 transcript molecules per ng of total RNA, in contrast to the younger leaf sample (LPI1). The levels of transcript accumulation for PtMKK7 are on the other hand relatively constant across most organs. This striking difference in expression pattern has also been observed in Arabidopsis expression databases for AtMKK7 and AtMKK9 [53] where AtMKK9 transcription is most strongly associated with mature or senescing leaves.

Discussion

The genomic organization of poplar MAPK and MAPKK genes clearly reflects the impact of whole genome duplications, of chromosomal duplications and of large-scale segmental duplications on the expansion of gene families. This is especially true for Populus, since genes represented by individual models in Arabidopsis are frequently found as unclustered paralogous gene sets in poplar. This mode of expansion is not unique to the MAPK and MAPKK genes, since a similar phenomenon has been observed for the poplar cellulose synthase (CesA) gene family [54]. The absence of tandemly duplicated gene clusters within the poplar MAPK and MAPKK gene families is also shared by other plant species including Arabidopsis and rice [39].

Comparative analysis of exon-intron junctions within the coding region of Arabidopsis MAPK and MAPKK gene families [55] and their poplar counterparts also highlights the conservation of these signaling components. Hence, group A and group C MPKs in both species display identical numbers of exons (six and two, respectively), and the sizes of the exons as well as the intron phases are extremely well conserved. These findings show that the respective degree of conservation of group A and group C MPK genes extends beyond primary sequence identity and is likely to be a feature of these genes in all eudicots.

A more complex situation exists for group B MPKs, where all group B PtMPKs contain six exons, while only two out of five group B AtMPKs (AtMPK4 and AtMPK12) display this organization. Nevertheless, except in PtMPK5-1, the phases of the various introns found in these gene models are also perfectly conserved. These gene models might thus share a common evolutionary history. On the other hand, AtMPK5, AtMPK11 and AtMPK13 all possess four exons with variable intron phase combinations. These combinations are not observed in any poplar MPKs. This suggests that the Arabidopsis group B MPK gene family has evolved differently than the corresponding poplar family. It is possible that one of the ancestral genes that gave rise to the present group B AtMPK family was not transmitted to poplar when these species diverged or that the precursor gene was lost during poplar evolution. Alternatively, the generation of the four exon configurations observed in Arabidopsis was the result of a duplication event that followed species divergence.

For group D MPKs, despite more complex configurations of exons and introns, it is possible to recognize that the respective putative orthologs between Arabidopsis and poplar display similar or sometimes even identical exon organization, with very well conserved exon length and intron phase. The only exception in this regard is AtMPK15, which possesses a unique seven exon composition within its coding region. This pattern is not observed for any other Arabidopsis or poplar MPK genes and indeed, no direct putative ortholog of AtMPK15 can be detected in the poplar genome. This AtMPK gene might therefore have arisen in Arabidopsis after species divergence, or might have been lost during poplar evolution.

At the level of MAPKKs, phylogenetic conservation of exon length and of exon-intron junctions is also generally observed. Hence, in group A MKKs, both the AtMKK2 and AtMKK6 coding regions are composed of eight exons, which is identical to the structure of their respective predicted orthologs in poplar, PtMKK2-2 and PtMKK6. In addition intron phase configuration is identical among these genes. On the other hand, the AtMKK1 coding region consists of six exons, a pattern that is not conserved in the coding region of the closest poplar putative ortholog, PtMKK2-1, which is constituted of nine exons. For group B MKKs, despite the high level of predicted protein sequence similarity between AtMKK3 and PtMKK3, the number of exons within their respective coding regions differs (eight exons for AtMKK3; nine for PtMKK3). However, this lack of conservation in the exon and intron organization is not caused by the kinase domain evolutionary status. In fact, the regions encoding the protein kinase domain are well conserved in terms of exon count, exon length and intron phase and differences between these two gene models are found at the end of the coding regions (within the NTF2 domain of the corresponding encoded proteins). Finally, as reported earlier [4], both the Arabidopsis group C and D MKKs display an intronless configuration. This trait is fully conserved within both poplar group C and group D MKK gene families.

Overall, exon lengths in both the Arabidopsis and poplar MPKs and MKKs are clearly more conserved than intron lengths. This indicates stronger negative selection for alteration of corresponding protein sequences. Additionally, most variations occurring in exon lengths come at the beginning or at the end of the coding sequences. This reflects that within the protein sequence, the centrally located kinase catalytic domain is probably submitted to more stringent functional conservation. Evolutionary analysis of plant terpene synthase genes also revealed strong conservation within the C-terminal enzyme catalytic site, with most variable domains observed in the N-terminal part of uncertain functions [56]. For their part, poplar MPK and MKK introns are generally much longer than those found in the corresponding Arabidopsis genes. This may reflect reduced pressure for genome compaction within the larger poplar genome.

Transcript abundance at a given time and in particular organs is an important prerequisite to subsequent production of the corresponding protein required for proper execution of developmental, metabolic and signaling processes. The goal of the present study was to obtain a reasonably comprehensive overview of the whole organ expression patterns for all members of the poplar MAPK and MAPKK gene families. These families contain numerous recently duplicated members (paralogs), which raises the question of the extent to which these copies have remained functionally redundant. Our data suggest that while these gene families are highly conserved among eudicot species, individual family members are nevertheless evolving to display considerable diversity and specialization in the context of poplar biology. For example, while the paralogous genes PtMPK3-1 and PtMPK3-2 share 93% amino acid sequence similarity, and both genes are expressed at similar levels in most organs, PtMPK3-2 transcripts are markedly more abundant than those of its sister paralog in all four types of bud organ. This association with developmentally distinct juvenile organs suggests that PtMPK3-2 may be undergoing neo-functionalization for specific developmental roles, perhaps related to meristem development. For organs other than buds, the similar transcriptional activity of both PtMPK3-1 and PtMPK3-2 might simply represent genetic redundancy, where expression of both genes contributes to a common signaling pathway. Alternatively, this could be an example of sub-functionalization [57], where both genes have become compromised in some of their functions, but when operating together, can still provide the functionality associated with the ancestral gene. Since the closest Arabidopsis and tobacco presumed orthologs of PtMPK3-1 and PtMPK3-2 are AtMPK3 and NtWIPK, respectively, two stress-responsive MAPKs that respond at both the transcriptional and post-translational levels to biotic and abiotic stresses [58,15], it will be interesting to determine whether one or both poplar genes display similar defence-related functions.

The expression profiles of the paralogous PtMPK6-1 and 6-2 genes differ from what has been reported for the putative orthologous tobacco genes, NtSIPK and Ntf4. While NtSIPK is expressed in leaves [19], stem and pollen [14], Ntf4 expression was found to be restricted to seeds, pollen and anthers [38] and notably, Ntf4 expression was not detected in female structures (ovaries and pistil) in the tobacco hermaphrodite flower. This suggests that specialized functions might have been acquired by one or both tobacco paralogs. On the other hand, since both paralogs are expressed in pollen, co-activation by the same MKK, NtMEK2, as well as the absence of phenotype after the silencing of Ntf4 [14], point to some level of genetic redundancy of these MAPKs in this particular organ. For poplar, despite the predominance in TA for PtMPK6-1 over PtMPK6-2 in all types of buds, in male and female flowers, there is no evidence of strikingly different patterns of expression. In fact, PtMPK6-1 and PtMPK6-2 display similar TA for most organs, suggestive of overall redundancy. Further investigation will be needed to evaluate the impact of this discrepancy in expression profiles between presumed orthologous tobacco and poplar genes. Interestingly, in a recent publication, NtSIPK and Ntf4 were both detected in leaf extracts using antibodies [59]. This contrasts with previously published data [38] and suggests that at least in leaves, both NtSIPK and Ntf4 display redundant expression profiles.

Expression of group B and C MPK genes has also been investigated in other species. For example, the phylogenetically closely related Arabidopsis AtMPK1 and AtMPK2, as well as the Petunia hybrida PhMEK1 gene and the tobacco Ntf3 gene, showed constitutive expression in various organs (leaves, stem, roots and flowers) [37,43,60]. Interestingly, AtMPK2 is more highly expressed than AtMPK1 in the analyzed organs [60], a situation also observed for the poplar predicted ortholog PtMPK1 over PtMPK2.

Other members of the group B and C MPK genes also display notable differences in their expression profiles. The poplar group C PtMPK7 is generally much more highly expressed than its paralog, PtMPK14, in all tested organs except cell cultures. As well, expression of the group B PtMPK5-2 is generally higher than that of PtMPK5-1. The physiological impact of these differences in levels of transcript accumulation among paralogs remains to be resolved. Such a pattern could however be an indicator of pseudogenization of one member of a recently duplicated gene pair, even though signal transduction genes are often thought to be subject to strong conservation constraints [61].

Although extensive microarray data are available, no systematic analysis of expression profiles of group D MPK genes in plants has been reported. However, OsWJUMK1, the rice putative ortholog of PtMPK20-1/20-2, was found to be expressed in both vegetative and reproductive organs [25] as are the poplar putative orthologs, with PtMPK20-1 expression dominating over PtMPK20-2. The PtMPK16-1/16-2 pair of paralogs is particularly interesting, since PtMPK16-1 is highly expressed in both male and female floral buds, whereas transcripts corresponding to PtMPK16-2 are barely detectable in these organs. Taken together with the PtMPK3-1/3-2 patterns, this points to particularly rapid divergence of functional specificity that highly similar paralogous genes appear to have evolved within the context of reproductive organ development in poplar.

Among the poplar MKKs, we found that PtMKK6 is strongly expressed in most of the actively proliferating organs we investigated. Consistent with this, the closest ortholog of PtMKK6 in tobacco, NtMEK1, encodes a protein that has been shown to be part of a MAPK cascade involved in the progression of the cell cycle [62]. A similar role has been identified for the Arabidopsis putative ortholog, AtMKK6 [13], which suggests that MKK6s could be highly conserved players in plant cytokinesis and stem cell development. PtMKK3, a group B MKK, is expressed at relatively high levels in all vegetative organs in poplar and is moderately expressed in all types of post-dormancy buds, as well as in male and female catkins. Likewise, in Arabidopsis, the orthologous AtMKK3 mRNA is detected in vegetative organs and also in the hermaphrodite flower [63].

Conclusion

Overall, our work demonstrates that differential spatio-temporal transcript accumulation patterns exist for most members of both the MPK and the MKK gene families in poplar. Although virtually all poplar MPK and MKK genes are expressed during development, there are striking differences in steady-state TA in specific cases, some of which could be associated with functional divergence between recently duplicated paralogs. However, it is also critical to note that while RTqPCR data provide an estimate of whole organ gene expression levels, more pronounced local patterns of differential expression associated with regions composed of specialized cells will not be detected. More fine-grained analyses such as in situ hybridization or promoter:reporter phenotyping will be required to define the exact pattern of expression of these paralogous gene pairs, particularly in biological contexts uniquely relevant to dioecious woody perennials, such as gender specification, male and female flower maturation or wood formation. Finally, while the focus of the present study was on MPKs and MKKs expression profiling in a developmental context, plant MAPK cascade components also play central roles in responses to environmental cues. It will therefore be interesting to monitor the expression of these genes in physiological contexts such as tree defence signaling during biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogen infections, or adaptation to environmental stresses.

Experimental procedures

Plant material and organ sampling

Hybrid poplar cell suspension cultures (Populus trichocarpa X Populus deltoides H11-11) were maintained as described previously [64]. Four days after transfer to fresh medium, cells were harvested by vacuum filtration, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C to await analysis. Hybrid poplar cuttings (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides H11-11) were grown in Promix soil under controlled greenhouse conditions (22°C/19°C day/night, 16-h day) for 2 weeks. Thereafter, young trees were placed in a growth chamber (Conviron, Environmental Growth Chambers Inc., Chagrin Falls, OH) where conditions were as follows: 26°C/22°C day/night, 20-h day, 60% RH, light intensity 100 μmol m-2 s-1. Plants were fertilized once every 2 weeks alternatively with 10/52/10 (0.5 g/l) plus 15.5/0/0 (Ca 19% 0.5 g/l) or with 20/20/20 (1 g/l) until PI 16 stage was reached [65]. Apex, young (LPI 1) and mature (LPI 12) leaves, upper stem (10 cm below the apex), primary phloem and xylem (10 cm above the ground) and roots were simultaneously removed from the trees, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Each specific organ was harvested from 12 different trees. Three biological samples were thus created by pooling each organ sample from four different trees. Ten-year-old field-grown trees (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides) located in Sainte-Croix-de-Lotbinière (46° 39'55"N 71° 51' 13" W) were used for sampling various bud types. Post-dormancy buds were collected on April 8 2005 on male and female trees by quickly removing them from previously cut branches. Bud samples were then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Other cut branches from male and female trees (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides) were also brought back to greenhouses to induce bud flush using the following conditions; 22°C/19°C day/night, 16-h day. Branches were placed in plastic buckets half-filled with water and buds were allowed to develop. Male and female catkins (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides) were collected when the completed developmental state was reached; 6 days for males and 11 days for females. At this stage, male catkins harbored pollenic bags and female catkins harbored fruiting capsules (Figure 7B,C). Other 10-year-old field-grown tree (P. trichocarpa X P. deltoides) organs (primary phloem, secondary xylem and xylem cambium-enriched) were kindly provided by Dr. Janice Cooke, Université Laval.

RNA purification and amplification of 3' non-coding regions of poplar MPK and MKK genes

The poplar genomic sequences and predicted coding sequences are available from the DOE Joint Genome Institute database [66]. As described elsewhere [39] gene models for MPKs and MKKs were targeted for phylogenetic study and a nomenclature based on predicted protein sequence similarity with Arabidopsis and rice was adopted to reflect putative orthology. This information was also used to manually establish chromosome position, exon-intron junctions and intron phase for each PtMPK and PtMKK gene family member. Given the high degree of gene conservation among MPK and MKK genes, it was essential to develop gene-specific probes based on the respective 3' non-coding regions. To do this, a cDNA library was prepared from mRNA isolated from poplar cell suspensions. Frozen poplar cell suspensions were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen and RNA samples were prepared as previously described [67]. From 1.3 mg total RNA, mRNA was isolated and subsequently purified using the Oligotex mRNA Maxi kit (Qiagen, Mississauga ON). Subsequently, 3'-RACE PCR reactions were performed following the manufacturer's instructions (SMART™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit, Clonetech, Palo Alto, CA). Based on the genomic and the predicted coding sequences of the poplar MPK and MKK genes, we designed one gene-specific sense primer at the end of the coding sequence of each gene (Tables 1 and 2). This allowed us to amplify the corresponding 3' untranslated region (UTR). Amplicons were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and these products were then ligated into pCR2.1 vector (Original TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and electrotransformed into E. coli XL1 blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmid DNA was subsequently purified using the QIA-prep-8 Plasmid Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using the dideoxy nucleotide termination method with an ABI 373 Stretch XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 3'UTR sequences were aligned using Multalin [68] with the genomic and the predicted coding sequences of the corresponding poplar MPK and MKK genes.

Table 1.

Sequences of PtMPKs 3'RACE and RTqPCR primers used for 3'UTR MAPK gene isolation and expression profiling.

| Group | Gene name | 3' RACE Primers (5' to 3') | Forward RTqPCR Primers (5' to 3') | Reverse RTqPCR Primers (5' to 3') |

| A | PtMPK3-1 | CCCACTTGTTCACCCTCTGGCCATTG | CCATAAGCACTACCAGTCC | TCA GATACAGAGGAGTGC |

| PtMPK3-2 | AGCATTGGCTCATCCATACCTTGCAAGG | CTTTAGCACTACCAATCCCG | TGAACAATTAGCAAGTCCAGG | |

| PtMPK6-1 | TCCCAACTGTCCACCCGGCAGCTATTG | CATTGTGACTGGTCAGCTTGA | GTTCCCCTGAATTCTGTCC | |

| PtMPK6-2 | GATCCCAGACAGAGGATTACTGTTGAGG | ATGAGTCGACCAGCGTGGC | CACTACATTGACGCCGATAC | |

| B | PtMPK4 | AGTCGATGAGGCACTGTGCCATCCATAC | TGGTGTGCAGTTGGGAAGG | GAACCTTCATAGAGATTCTGC |

| PtMPK5-1 | TCGCATCACTGTTGATGAGGCCCTTTGT | CGTCATTTCCTGGAGAATATG | ACAATGCAATTCACTTCAGGC | |

| PtMPK5-2 | CCCAATAACCGCATCACTGTCGATGAGG | CATAACTTCTGACACATTTGGG | CATACAACACATGATCCTTGC | |

| PtMPK11 | GAGGCATTGTGCCATCCATACTTGGCAC | GTTTGCTGAGCAGAATCTCC | GCGTCCTCAAAACCATGAAG | |

| C | PtMPK1 | CCGGAGCACTGGAACACCCTTACATGTC | AAGAAGCACGCACAAGCCAG | TACAAGCTGAAAGGGCCACC |

| PtMPK2 | GCTGCAACCCTCCAGCTCAGGTCCC | GTGTGTTTTTGTACGTGTCTG | AGAACTAGAAGCTCACTGCC | |

| PtMPK7 | CAGGGCTGTACGATCCAAGACGCGACCC | CTAGTGTGTCTGTGAGATCAG | GGATGCCATAGTCCGGCTC | |

| PtMPK14 | ACCCTTACATGTCAGGGCTGCACGATCC | TGCACGATCCAAGACACGAC | TGCGAAAACAACTTCTGGGTG | |

| D | PtMPK9-1 | CCAGGGTCACAGCAACCAGATGGTTCAG | GATTCAGATGGCTGCCTTTG | ACAAGCTACTGCCTGATCTTC |

| PtMPK9-2 | GCAGCTCAAAGCACTGATATTGAGAGGC | CCAGCGTAGTGTGGATAGTG | TCACATCTCCTCTCTGCAATC | |

| PtMPK16-1 | CGGTGCTGCGTTACAACAATTGTGGAGC | AATCTGTGCCATTTTGTCTGTG | TGGCCTTATGAATACAGCCAC | |

| PtMPK16-2 | GTGGAGCAGCAGCAGCAGAGAATCTTGA | CAGCAGCAGAGAATCTTGAC | CCATTGGAACCTTCAACCAC | |

| PtMPK17 | CTCTTTCTCGTGCAGCTAAGCAGAGCCC | CCTATTTGCACATCTTGGAGG | GCGGTAGTACATTTAGTGAGG | |

| PtMPK18 | CCTCCCCAAACCAGCTCTCCACACCACTGCT | GATAAATCCTTTCCACCCTCG | GTTGACTACACCCTTGAAACC | |

| PtMPK19 | CTGGGATGGCCATGGATGTGAACGCCTA | GTTGGTATCACGATCAATTATG | TGACTAGATACAGGACGTGG | |

| PtMPK20-1 | GGGAGGGAGCAAGGAAGAACATGTGGAT | GGACTGAGGAGATCCACTTG | CCCCCTCTTTTTACACAATCC | |

| PtMPK20-2 | GTGGCATGGCAGCCAAATATGCACCAGA | GGTTGGAGCTGTTCAATATGG | GACACGTTGATCTTCTGAGTC |

Table 2.

Sequences of PtMKKs " 3'RACE and RTqPCR primers used for 3'UTR MAPKK gene isolation and expression profiling.

| Group | Gene name | 3' RACE Primers (5' to 3') | Forward RTqPCR Primers (5' to 3') | Reverse RTqPCR Primers (5' to 3') |

| A | PtMKK2-1 | TGGTATTGCTGGAGTGTGCAACAGGCCA | TGCAAATGCATCAAACTCCTG | CCACCCAAAAGAGACATCAG |

| PtMKK2-2 | CTCCACCTTCTGCACCACCAGACCAATT | AGCTTGCAAACTATGAGGAAC | CGATTCTGTCAGGGAAAACC | |

| PtMKK6 | GCTGCAACCCTCCAGCTCAGGTCCC | GGGAAGGTTGTCATCTTTGG | TGGGTAATTCACAGGAGGTTC | |

| B | PtMKK3 | GCAGTTGCAATCCGCGTTTCAGGATCC | GCTCTATGTTCCTCCAGTTAC | GAAATGGTTTCATATCTGTCACG |

| C | PtMKK4 | ATTGCTTGTTGTTTGCAGAGGGAGCCGG | GAATTGTTGTGGGTTATTGTTG | GGTCAGAACTAAAGGTGCTGTG |

| PtMKK5 | CCCAATAACCGCATCACTGTCGATGAGG | AGCATCCGTTTATTGTGAGAAG | AACTACCTACTAAGCAATTGGC | |

| D | PtMKK7 | CGAGCTTGCCGGAGGGAGCATCTGAGGA | TGACCCGAATGCCCAGTTAA | TTCCTCTCATTTCAAGAGCAG |

| PtMKK9 | GCGTCGGAGGAGTTTCGGGACTTTATTC | ACTTTATTCAGTGTTGCCTGC | GGGTCAAATCACAAGTCCAC | |

| PtMKK10 | TGTGGAGAGAAACCAGACTGGGCAGCAT | TTTGGTCTGGATATAAGCTGTG | TGCAAAACCAGCATCATCTTC | |

| PtMKK11-1 | GGGAGTGCTCTGCAGTTGTTGCAACACC | TGCAACACCCTTTTATACTGC | TGATGGAAGTGACAGGATGG | |

| PtMKK11-2 | GGAGAATCCCCTAGCTTCCCAAAGGAAG | CCTATGTTTGCTTAGGGGAG | TTGGTCCAAGAGCCATTTCG |

All poplar organ-specific samples were ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was isolated as previously described [67]. To remove DNA traces in total RNA samples, we performed DNase treatments as recommended in the manufacturer's instructions (DNase 1 Deoxyribonuclease I digests, Invitrogen). cDNAs were synthesized from 500 ng total RNA (SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System, Invitrogen).

Real-Time quantitative PCR (RTqPCR) analysis

In order to confirm the efficiencies of the RTqPCR primer sets, genomic DNA from Populus trichocarpa (Nisqually-1), Populus trichocarpa X Populus deltoides (H11-11) and Populus deltoides (ST-70) was extracted using 150 mg of leaf tissue (LPI 3). Briefly, plant material from each genetic background was ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. DNA extractions were then conducted using DNeasy system (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five nanograms of DNA were used in each RTqPCR reaction that was carried out using the Opticon2 DNA Engine (MJResearch, Waltham, MA). After an initial 15 min activation step at 95°C, 45 cycles (94°C, 15 s; 57°C, 1 min; 72°C, 30 s) were performed and a single fluorescence reading was taken after each cycle immediately following the elongation period at 72°C. A melting curve was performed at the end of the cycling procedure to ensure single product amplification. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were determined by the Opticon Monitor 2 software at a manually set fluorescence threshold of 0.016. Agarose gel electrophoresis (1.2%) was also performed to compare amplicons obtained from the various genetic backgrounds.

To quantify organ-specific TA for the corresponding poplar MPK and MKK genes, standard curves were produced based on serial dilution of each of the pCR2.1 plasmids containing the cloned 3'UTR of each gene, and used to determine the number of transcript molecules as described in [69]. Twelve nanogram aliquots of cDNA were used in each RTqPCR reaction. Amplifications were conducted in 1× QuantiTect™ SYBR Green mix (Qiagen) with 0.25 μM of both forward (5') and reverse (3') oligonucleotide RTqPCR primers. Specific 5'- and 3'-oligonucleotides were designed to target the previously sequenced 3' UTR regions of each poplar MPK and MKK gene (Tables 1 and 2), and RTqPCR reactions were carried out as described above, except that the manually set fluorescence threshold was 0.03.

In order to obtain consistent and reproducible RTqPCR data, accurate measurement of RNA concentrations and the preparation of samples that are free from any inhibitors of the reverse transcription and PCR processes are critical steps. Moreover, since we have analyzed many different organs in parallel, it was necessary to normalize the data by employing internal standard candidate genes that show consistent expression over a wide array of tissues or organ samples. To validate proper dosage of cDNA, cdc2 RTqPCR primers were included in the analysis as a control gene. Primer sequences were as follows: forward primer sequence: 5'ATTCCCCAAGTGGCCTTCTAAG 3'; reverse primer sequence: 5' TATTCATGCTCCAAAGCACTCC 3'). Act2 was also employed as a control housekeeping gene and RTqPCR primer sequences were as follows: forward primer sequence: 5' TTCTACAAGTGCTTTGATGGTGAGTTC 3'; reverse primer sequence: 5' CTATTCGATACATAGAAGATCAGAATGTTC 3').

To simplify graphical presentation, standard deviations are not included in Figures 8 to 10. However, all the corresponding data together with respective standard deviation are available in the additional files 2 and 3. Each value of transcript accumulation for a specific PtMPK or PtMKK gene represents the average of six independent PCR reactions; two technical repetitions of three biological samples. Overall, regardless of organs or phylogenetic classification, technical variation within one sample was, on average, < 0.25 Ct. This means that our quantification of transcript accumulation was highly reproducible within one sample and that technical error has little impact on the values reported here. The variation from one biological sample to another within a specific organ was also consistently < 1.0 Ct. Samples that showed greater variation than 1.0 Ct were reamplified, with usually smaller disparity. The highest variations on transcripts numbers were found in leaf samples (LPI 1 and 12) as well as in xylem and secondary phloem, for both MPK and MKK gene families. The underlying reason for this finding remains unclear, but it could be associated with higher concentrations of potent inhibitors of the reverse transcription and/or PCR processes.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

M-CN and L-PH designed and performed all the in silico analysis and laboratory experiments, and drafted the manuscript. M-JM participated to the real time RT-qPCR experiments. NB and BEE critically revised the manuscript and provided important intellectual content. AS conceived the analysis, participated in its coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read, helped to edit, and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Evaluation of each RTqPCR primer set efficiency using genomic DNA from three different genetic backgrounds: Populus trichocarpa (T), Populus trichocarpa X Populus deltoides (TXD) and Populus deltoides (D).

Raw values, standard deviations and means of the number of transcript molecules per ng of total RNA obtained for each PtMPK gene in the various poplar organs surveyed.

Raw values, standard deviations and means of the number of transcript molecules per ng of total RNA obtained for each PtMKK gene in the various poplar organs surveyed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Brian Boyle (Canadian Forest Service) who provided help for RTqPCR analysis. We also thank Dr. Janice Cooke (Université Laval) who provided some of the 10-year-old field-grown tree organs, and Dr. Steven Strauss and Dr. Amy M. Brunner (Oregon State University) who supplied total RNA extracts from early stage floral organs (data not shown). Finally, special thanks go to Caroline Côté (Université Laval) for her help with the poplar cuttings and to Serge Morin (Minitère de Ressources naturelles et de la Faune du Québec) for helpful discussions and assistance with collection of the various bud types. This work was supported by a grant from the National Biotechnology Strategy of Canada and NSERC to A. Séguin, and an NSERC scholarship to L.-P. Hamel.

Contributor Information

Marie-Claude Nicole, Email: MCNicole@cfl.forestry.ca.

Louis-Philippe Hamel, Email: LPHamel@cfl.forestry.ca.

Marie-Josée Morency, Email: MJMorency@cfl.forestry.ca.

Nathalie Beaudoin, Email: Nathalie.Beaudoin@USherbrooke.ca.

Brian E Ellis, Email: bee@interchange.ubc.ca.

Armand Séguin, Email: seguin@cfl.forestry.ca.

References

- Widmann C, Gibson S, Jarpe MB, Johnson GL. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:143–180. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/er.22.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Pitzschke A, Hirt H. Emerging MAP kinase pathways in plant stress signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:301–308. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu WL, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature. 2002;415:977–983. doi: 10.1038/415977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Klessig DF. MAPK cascades in plant defense signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:520–527. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel MA, Miles GP, Ellis BE. Ozone treatment rapidly activates MAP kinase signalling in plants. Plant J. 2000;22:367–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrose M, Bonshtien A, Sessa G. LeMPK3 is a mitogen-activated protein kinase with dual specificity induced during tomato defense and wounding responses. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14819–14827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonak C, Nakagami H, Hirt H. Heavy metal stress. Activation of distinct mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways by copper and cadmium. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3276–3283. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockaitis K, Howell SH. Auxin induces mitogenic activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation in roots of Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2000;24:785–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knetsch M, Wang M, Snaar-Jagalska BE, Heimovaara-Dijkstra S. Abscisic Acid Induces Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation in Barley Aleurone Protoplasts. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1061–1067. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.6.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett EC, Desikan R, Moser RC, Neill SJ. ABA activation of an MBP kinase in Pisum sativum epidermal peels correlates with stomatal responses to ABA. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:197–205. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.343.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Nishihama R, Morikiyo K, Ishikawa M, Machida Y. NQK1/NtMEK1 is a MAPKK that acts in the NPK1 MAPKKK-mediated MAPK cascade and is required for plant cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1055–1067. doi: 10.1101/gad.1071103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin V, Aionesei T, Limmongkon A, Barinova I, Touraev A, Lauriere C, Coronado MJ, Testillano PS, Risueno MC, Heberle-Bors E, Wilson C. The MAP kinase kinase NtMEK2 is involved in tobacco pollen germination. FEBS Lett. 2004;560:86–90. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Liu Y, Klessig DF. Multiple levels of tobacco WIPK activation during the induction of cell death by fungal elicitins. Plant J. 2000;23:339–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Du H, Klessig DF. Activation of the tobacco SIP kinase by both a cell wall-derived carbohydrate elicitor and purified proteinaceous elicitins from Phytophthora spp. Plant Cell. 1998;10:435–450. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Klessig DF. Resistance gene N-mediated de novo synthesis and activation of a tobacco mitogen-activated protein kinase by tobacco mosaic virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7433–7438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeis T, Piedras P, Zhang S, Klessig DF, Hirt H, Jones JD. Rapid Avr9- and Cf-9-dependent activation of MAP kinases in tobacco cell cultures and leaves: convergence of resistance gene, elicitor, wound, and salicylate responses. Plant Cell. 1999;11:273–287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Klessig DF. The tobacco wounding-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase is encoded by SIPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7225–7230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang S. Phosphorylation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase by MPK6, a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3386–3399. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CY, Liu Y, Thorne ET, Yang H, Fukushige H, Gassmann W, Hildebrand D, Sharp RE, Zhang S. Activation of a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade induces the biosynthesis of ethylene in plants. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2707–2718. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jin H, Yang KY, Kim CY, Baker B, Zhang S. Interaction between two mitogen-activated protein kinases during tobacco defense signaling. Plant J. 2003;34:149–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HJ, Fu SF, Tai YH, Chou WC, Huang DD. Expression of Oryza sativa MAP kinase gene is developmentally regulated and stress-responsive. Physiol Plant. 2002;114:572–580. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal GK, Iwahashi H, Rakwal R. Rice MAPKs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal GK, Agrawal SK, Shibato J, Iwahashi H, Rakwal R. Novel rice MAP kinases OsMSRMK3 and OsWJUMK1 involved in encountering diverse environmental stresses and developmental regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:775–783. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebersold DM, Shaul YD, Yung Y, Yarom N, Yao Z, Hanoch T, Seger R. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1c (ERK1c), a novel 42-kilodalton ERK, demonstrates unique modes of regulation, localization, and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10000–10015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10000-10015.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. Structural organization of MAP-kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in yeast and mammals. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:481–485. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elion EA. The Ste5p scaffold. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3967–3978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberherr D, Thao NP, Nakashima A, Umemura K, Kawasaki T, Shimamoto K. A sphingolipid elicitor-inducible mitogen-activated protein kinase is regulated by the small GTPase OsRac1 and heterotrimeric G-protein in rice 1. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1644–1652. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.057414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Rudd JJ, Macioszek VK, Scheel D. Dynamic changes in the localization of MAPK cascade components controlling pathogenesis-related (PR) gene expression during innate immunity in parsley. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22440–22448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung Y, Yao Z, Hanoch T, Seger R. ERK1b, a 46-kDa ERK isoform that is differentially regulated by MEK. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15799–15808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910060199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama R, Banno H, Kawahara E, Irie K, Machida Y. Possible involvement of differential splicing in regulation of the activity of Arabidopsis ANP1 that is related to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) Plant J. 1997;12:39–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12010039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Yang Y. Disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance in rice are inversely modulated by an abscisic acid-inducible mitogen-activated protein kinase. Plant Cell. 2003;15:745–759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogre L, Ligterink W, Meskiene I, Barker PJ, Heberle-Bors E, Huskisson NS, Hirt H. Wounding induces the rapid and transient activation of a specific MAP kinase pathway. Plant Cell. 1997;9:75–83. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Fong SH, Yang D, Wang GL. BWMK1, a novel MAP kinase induced by fungal infection and mechanical wounding in rice. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999;12:1064–1073. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.12.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decroocq-Ferrant V, Decroocq S, Van Went J, Schmidt E, Kreis M. A homologue of the MAP/ERK family of protein kinase genes is expressed in vegetative and in female reproductive organs of Petunia hybrida. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:339–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00020188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin V, Touraev A, Kieft H, van Lammeren AA, Heberle-Bors E, Wilson C. Temporal and tissue-specific expression of the tobacco ntf4 MAP kinase. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;45:679–689. doi: 10.1023/A:1010645431133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel LP, Nicole MC, Sritubtim S, Morency MJ, Ellis M, Ehlting J, Beaudoin N, Barbazuk B, Klessig D, Lee J, Martin G, Mundy J, Ohashi Y, Scheel D, Sheen J, Xing T, Zhang S, Seguin A, Ellis BE. Ancient signals: Comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature. 1990;344:503–508. doi: 10.1038/344503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner AM, Yakovlev IA, Strauss SH. Validating internal controls for quantitative plant gene expression studies. BMC Plant Biol. 2004;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Eller N, Gartner A, Vicente O, Heberle-Bors E. Isolation and characterization of a tobacco cDNA clone encoding a putative MAP kinase. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:543–551. doi: 10.1007/BF00019302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R, Landgraf J, Accerbi M, Simon V, Larson M, Wisman E. Microarray analysis of diurnal and circadian-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:113–123. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SF, WC C, Huang DD, Huang HJ. Transcriptional regulation of a rice mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, OsMAPK4, in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:958–963. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbeck MA, Samac DA, Fedorova M, Gregerson RG, Gantt JS, Vance CP. The alfalfa (Medicago sativa) TDY1 gene encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:882–893. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.10.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong YH, Moon BC, Kim JK, Kim CY, Kim MC, Kim IH, Park CY, Kim JC, Park BO, Koo SC, Yoon HW, Chung WS, Lim CO, Lee SY, Cho MJ. BWMK1, a rice mitogen-activated protein kinase, locates in the nucleus and mediates pathogenesis-related gene expression by activation of a transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1961–1972. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderini O, Glab N, Bergounioux C, Heberle-Bors E, Wilson C. A novel tobacco mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase, NtMEK1, activates the cell cycle-regulated p43Ntf6 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18139–18145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikant B, Giuliani C, Halbmayer-Watzina S, Limmongkon A, Heberle-Bors E, Wilson C. The Arabidopsis thaliana MEK AtMKK6 activates the MAP kinase AtMPK13. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou S, Yamamoto A, Yoshioka H, Kawakita K, Doke N. Functional analysis of potato mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, StMEK1. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2003;69:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kiegerl S, Cardinale F, Siligan C, Gross A, Baudouin E, Liwosz A, Eklof S, Till S, Bogre L, Hirt H, Meskiene I. SIMKK, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase, is a specific activator of the salt stress-induced MAPK, SIMK. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2247–2258. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KY, Liu Y, Zhang S. Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in disease resistance in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:741–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genvestigator®. 2006. https://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch/

- Djerbi S, Lindskog M, Arvestad L, Sterky F, Teeri TT. The genome sequence of black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) reveals 18 conserved cellulose synthase (CesA) genes. Planta. 2005;221:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1498-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Information Resource. 2006. http://www.arabidopsis.org/

- Trapp SC, Croteau RB. Genomic organization of plant terpene synthases and molecular evolution implications. Genetics. 2001;158:811–832. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold E. Plant metabolic diversity: a regulatory perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi T, Irie K, Hirayama T, Hayashida N, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Matsumoto K, Shinozaki K. A gene encoding a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase is induced simultaneously with genes for a mitogen-activated protein kinase and an S6 ribosomal protein kinase by touch, cold, and water stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:765–769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Yang KY, Li GJ, Liu Y, Zhang S. Activation of Ntf4, a tobacco MAPK, during plant defense response and its involvement in hypersensitive response-like cell death. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1482–1493. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi T, Gotoh Y, Nishida E, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Hayashida N, Iwasaki T, Kamada H, Shinozaki K. Characterization of two cDNAs that encode MAP kinase homologues in Arabidopsis thaliana and analysis of the possible role of auxin in activating such kinase activities in cultured cells. Plant J. 1994;5:111–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.5010111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Purugganan MD. The evolutionary dynamics of plant duplicate genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Ishikawa M, Nishihama R, Araki S, Ito M, Ito M, Machida Y. Control of plant cytokinesis by an NPK1-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:767–775. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Hayashida N, Seki M, Shinozaki K. Molecular cloning and characterization of three cDNAs encoding putative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKKs) in Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 1998;5:341–348. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.6.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel LP, Miles GP, Samuel MA, Ellis BE, Séguin A, Beaudoin N. Activation of stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa × Populus deltoides) Tree Physiol. 2005;25:277–288. doi: 10.1093/treephys/25.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson PR, Isebrands JG. The plastochron index as applied to developmental studies of cottonwood. Can J For Res. 1971;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Eukaryotic Genomics. 2006. http://genome.jgi-psf.org

- Chang S, Puryear J, Cairney J. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1993;11:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchicalclustering. 2006. http://prodes.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/multalin.html

- Rutledge RG, Côté C. Mathematics of quantitative kinetic PCR and the application of standard curves. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:e93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Evaluation of each RTqPCR primer set efficiency using genomic DNA from three different genetic backgrounds: Populus trichocarpa (T), Populus trichocarpa X Populus deltoides (TXD) and Populus deltoides (D).

Raw values, standard deviations and means of the number of transcript molecules per ng of total RNA obtained for each PtMPK gene in the various poplar organs surveyed.

Raw values, standard deviations and means of the number of transcript molecules per ng of total RNA obtained for each PtMKK gene in the various poplar organs surveyed.