Abstract

NK1 and NK3 receptors do not appear to play significant roles in normal GI functions, but both may be involved in defensive or pathological processes. NK1 receptor antagonists are antiemetic, operating via vagal sensory and motor systems, so there is a need to study their effects on other gastro-vagal functions thought to play roles in functional bowel disorder's. Interactions between NK1 receptors and enteric nonadrenergic, noncholinergic motorneurones suggest a need to explore the role of this receptor in disrupted colonic motility. NK1 receptor antagonism does not exert consistent analgesic activity in humans, but similar studies have not been carried out against pain of GI origin, where NK1 receptors may have additional influences on mucosal inflammatory or ‘irritant' processes. NK3 receptors mediate certain disruptions of intestinal motility. The activity may be driven by tachykinins released from intrinsic primary afferent neurones (IPANs), which induce slow EPSP activity in connecting IPANs and hence, a degree of hypersensitivity within the enteric nervous system. The same process is also proposed to increase C-fibre sensitivity, either indirectly or directly. Thus, NK3 receptor antagonists inhibit intestinal nociception via a ‘peripheral' mechanism that may be intestine-specific. Studies with talnetant and other selective NK3 receptor antagonists are, therefore, revealing an exciting and novel pathway by which pathological changes in intestinal motility and nociception can be induced, suggesting a role for NK3 receptor antagonism in irritable bowel syndrome.

Keywords: Tachykinins, NK1, NK3, emesis, intestinal motility, visceral pain, osanetant, talnetant

Introduction

The presence of tachykinins in the gut and their actions when exogenously-applied have been extensively studied (Holzer & Holzer-Petsche, 2001). Mammalian tachykinins (substance P, neurokinins A and B) activate tachykinin NK1, NK2 and NK3 receptors, with a characteristic rank-order of affinity. Neurokinin B (NKB), for example, has the highest affinity for NK3 receptors, followed by NKA>substance P, which in turn, have greater affinity for NK2 and NK1 receptors, respectively (Maggi, 2000). However, the differences in affinities are not large, so in terms of an ability to interact with each of the NK receptors, a degree of ‘agonist-promiscuity' becomes a real possibility. This concept is discussed later, with respect to the role of the NK3 receptor in the intestine.

The availability of selective NK receptor antagonists makes its possible to investigate the actions of endogenous tachykinins on normal, defensive and pathological gastrointestinal (GI) functions. This review focuses on the NK1 and NK3 receptors and their possible involvement in functional bowel disorders (FBDs).

NK1 Receptors

Nausea and vomiting

NK1 receptor antagonists such as aprepitant, vofopitant and ezlopitant can inhibit acute and delayed emesis induced by cancer chemotherapeutic agents when given alone and more importantly, when given in combination with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and/or dexamethasone (Andrews & Rudd, 2004). For optimal activity, NK1 receptor antagonists must cross the blood–brain barrier to reach a number of different brain regions. The relative importance of these regions in determining the antiemetic efficacy is unclear. A prevailing view is that NK1 receptors within the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) of the brainstem play a major role, probably by acting ‘upstream' from the vagal nerve terminal (Watson et al., 1995; Andrews & Rudd, 2004). In addition, NK1 receptors elsewhere play important roles, noteably those within the Botzinger complex (part of the ventral respiratory group of neurones) and the dorsal motor vagal nucleus (DMVN, from where a majority of vagal efferents project back to the gut). In the latter, NK1 receptors are present on motor neurones projecting to the greater curvature of the stomach (Ladic & Buchan, 1996; Lewis & Travagli, 2001), implicating these receptors in physiological (e.g., fundic accomodation) and pathological behaviours of the stomach (e.g., gastric relaxation, leading to nausea or stasis), probably via release of nitric oxide (NO) and VIP within the enteric nervous system (ENS) (Krowicki & Hornby, 2000). NK1 receptors are not expressed on all vagal terminals. Blondeau et al (2002) reported that NK1-receptor immunoreactivity (NK1-Ir) was present in 19% of vagal neurones innervating the rat stomach, rising to 46% for the duodenum, but being absent on vagal neurones innervating the ileum and caecum.

The NTS is regarded as a major integrative region, receiving the majority of the abdominal vagal afferent neurones as well as information from other brain areas, and sending projections to regions involved in different motor components of the emetic reflex. The widespread distribution of NK1 receptors to the NTS (Watson et al., 1995) and to the DMVN (e.g., Maubach & Jones, 1997; Krowicki & Hornby, 2000) is consistent with the observation that in animals, anti-emetic activity is observed regardless of the emetic stimulus. Thus, NK1 receptors can be considered to ‘gate' an emetic stimulus arising from ‘peripheral' (e.g., via the blood to the Area Postrema (AP) or via vagal afferent fibres to the NTS and the AP) or ‘central' sources (i.e., projecting to the NTS for integration and ultimately involving the DMVN).

Gastro-vagal activity in functional bowel disorders

The antiemetic activity of NK1 receptor antagonists is currently the only function that is observed in both animals and humans. This activity plus the widespread distribution of the receptor to brainstem nuclei receiving and driving vagal activity suggests that NK1 receptor antagonists might also affect certain symptoms of FBD's (e.g., functional nausea and/or functional dyspepsia), which may be mediated via the vagus (see Andrews & Sanger, 2002, for a discussion on this possibility). Three areas are considered.

Subcomponents of the emetic reflex

The antiemetic activity of NK1 receptor antagonists indicates a role for the receptor in mediating a defensive behaviour of the gut, but the absence of significant GI ‘adverse events' during trials with these compounds (see Andrews & Rudd, 2004) suggests little or no role in normal GI physiology. However, it is not known if NK1 receptors can mediate symptoms of FBDs that are less severe than emesis, but that superficially appear to resemble ‘components' of the emetic response. For example, are NK1 receptors involved in the generation of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations, a vago-vagal reflex that vents gas from the stomach, but that is also involved in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux (Holloway & Dent, 2000)? Does the receptor have a role in symptoms of nausea or early satiety in patients with functional nausea and functional dyspepsia? The answers to these questions are important not just to develop the full therapeutic potential of NK1 receptor antagonists but also to investigate the degree to which tachykinin functions are activity-dependent, with efficacy increasing in proportion to the severity of symptoms.

Affective pain

An involvement of the vagus in affective-emotional components of visceral pain is recognised clinically (Ness et al., 2001) and in animals (e.g., Traub et al., 1996, using rat gastric distension as a model). Further, Jocic et al (2001) and Michl et al. (2001) exposed the rat stomach to noxious levels of acid and measured cfos activity in the brainstem. NK1 receptor antagonism attenuated the acid-induced transcription of cfos mRNA in the NTS and augmented it in the subfornical organ. The authors suggested that these changes play some role in dyspepsia, a consideration given weight by the ability of the vagus to signal and evoke many of the different components of dyspepsia (Andrews & Sanger, 2002).

Gastro-vagal-inflammation or irritation

Anterograde tachykinin release from vagal neurones may play at least some role in exacerbating or mediating relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) and/or fundus. Thus, in the ferret isolated LES, relaxation evoked by capsaicin was reduced by NK1 receptor antagonism (Smid et al., 1998). In anaesthetised ferrets, repeated oesophageal acidification evoked LES relaxation, thought to be due to substance P released from extrinsic afferent nerve endings, activating local inhibitory pathways via NK1 receptors (Blackshaw & Dent, 1997). Similar data were obtained in guinea-pig gastric fundus, where NKA induced relaxation (Jin et al., 1998). In human isolated LES, [Sar9, Met (O2)11]-SP had no effects on muscle tension (Huber et al., 1993), but further experiments are required to examine the influence of this ligand on nerve-mediated activity.

Substance P is stored in large amounts within enterochromaffin (EC) cells of the mucosa, where it can be released to act at NK1 receptors on vagal afferent nerve terminals situated in close proximity (Minami et al., 2001). The role played by this source of substance P is unclear. Interestingly, raised levels of substance P and NK1-Ir have been reported in the crypt epithelia of rats with experimentally induced colitis or ileal pouch inflammation; in the ileal pouch, the inflammation was reduced by NK1 receptor antagonism (see Stucchi et al., 2003). Investigations into the pathophysiological functions of substance P-containing EC cells are, therefore, warrented.

Intestinal motility and secretion

NK1-Ir has been found in the mouse ileum ENS and on the interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICC's; Vannucchi & Faussone-Pellegrini, 2000). In human colon, NK1-Ir has been observed in circular but not usually the longitudinal muscle, and possibly also in the ICCs. Intense staining around the blood vessels and in the muscle precluded any ability to say that the receptors were located on enteric nerves (Rettenbacher & Reubi, 2001). In guinea-pig ileum, NK1 receptors were found mostly on NO synthase-containing myenteric neurones, with some on neurones expressing choline acetyltransferase and other markers projecting to the circular muscle, mucosa and submucosa. In the submucosal plexus, most NK1-Ir had neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity (Lomax et al., 1998).

In general, NK1 receptors do not play a major role in normal intestinal motility. However, although NK1 receptor antagonism has little or no effects on normal peristalsis in guinea-pig or pig isolated intestine (Holzer et al., 1998; Tonini et al., 2001; Schmidt & Hoist, 2002), villous agitation may evoke substance P-mediated, tetrodotoxin-sensitive internalisation of NK1 receptors in myenteric neurones of guinea-pig ileum (Southwell et al., 1998), and NK1 receptor antagonism can abolish the noncholinergic component of peristalsis measured during muscarinic receptor antagonism (Holzer et al., 1998; Tonini et al., 2001; Schmidt & Hoist, 2002). These and other data suggest a role for NK1 receptors in noncholinergic, nonadrenergic (NANC) neurotransmission. NANC excitatory effects may be induced by NK1 receptor activation in human isolated ileum (Zagorodnyuk et al., 1997). In rat isolated colon, NK1 receptor antagonism reduced electrically evoked, ascending, excitatory nerve-mediated contractions (Hahn et al., 2002). Similarly, observations with NK1 receptor knockout mice (Saban et al., 1999) suggest that both the knockout and NK1 receptor antagonism increase NANC inhibitory motor nerve activity. By contrast, in guinea-pig ileum, NK1 receptor antagonism had no effect on ascending enteric reflex contractions evoked by distension (Holzer et al., 1993) but reduced the descending inhibitory reflex (Johnson et al., 1998), these data being consistent with the effects of NK1 receptor agonists on guinea-pig inhibitory neurotransmission (Lecci et al., 1999; Bian et al., 2000).

The ability of NK1 receptors to modulate NANC activity currently has no clear function, although a role in colonic motility is suggested. In human colon circular muscle, NK1 receptor activation facilitated electrically-induced, neuronally-mediated after-contractions (Mezies et al., 2001), and this effect was greater in preparations resected from patients with idiopathic chronic constipation, in which smaller responses to electrical stimulation were observed (Mitolo-Chieppa et al., 2001). Further, close intra-arterial injections of NK1 receptor agonists stimulate giant migrating contractions of dog colon (Tsukamoto et al., 1997) and antagonism at the receptor blocked increased defaecation induced by restraint stress in rats (Ikeda et al., 1995) and blocked substance P- and stress-induced defaecation by Monglolian gerbils, without affecting increases in defaecation evoked by 5-HT or carbachol (Okano et al., 2001). In conscious dogs, De Ponti et al. (2001) found that NK1 (or NK2 or NK3) receptor antagonism had no effects on propagated colonic myoelectrical events induced by 5-HT4 receptor activation, but reduced the associated increase in electrical spike or mechanical activity, an effect not observed with these antagonists in the small intestine. Together, these studies are consistent with an action of NK1 receptors within the large bowel, although for the studies in vivo, a spinal site of action cannot always be ruled out. However, two other studies seem to be at variance with this view. Bradesi et al (2002) reported that NK1 receptor antagonism inhibited substance P-induced histamine release from the colon of rats exposed to restraint stress, but this effect was absent in pre-ovariectomised rats, suggesting an involvement of ovarian steroids in the response. Secondly, prokinetic activity was observed in response to NK1 receptor antagonism in rabbit isolated colon (Onori et al., 2003).

Gastrointestinal nociception or hypersensitivity

In spite of excellent antinociceptive properties of NK1 receptor antagonists in animals, this promise has not been reproduced in humans (Hill, 2000). Suggested reasons for this failure include a requirement to predose with the antagonist, receptor/neurotransmitter redundancy in pain-conducting systems or a mismatch between the complex animal appreciation of ‘nociception' and the human sensation of pain (see Laird et al., 2000a, for an expansion of this argument).

For the gut, antinociceptive actions of NK1 receptor antagonists have been observed using rat models of discomfort induced by gastric or colorectal distension (e.g., Julia et al., 1994; Anton et al., 2001; but see Kamp et al., 2001) and also in guinea-pigs, where antinociceptive activity was apparent only in animals with a sensitised response to colo-rectal distension (Greenwood-van Meerveld et al., 2003). Using NK1 receptor knockout mice, different intestinal nociceptive stimuli were suggested to operate via NK1-dependent (neurogenic inflammation) and –independent (non-neurogenic inflammation or mechanical) pathways (Laird et al., 2000a, 2000b). These data are consistent with an involvement of NK1 receptors in intestinal inflammation induced by infection (Sonea et al., 2002), intracolonic infusion of the proteinase-activated receptor-2 ligand SLIGRL (Cenac et al., 2003) or following ischaemia and reperfusion (Souza et al., 2002). In patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), raised numbers of mucosal mast cells have been reported and these changes were not clearly correlated with symptoms in one study (O'Sullivan et al., 2000), but increased numbers of activated colonic mast cells in close proximity to nerve fibres were correlated to symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort in another (Barbara et al., 2004). Ion secretion evoked by mast cell stimulation, capsaicin or electrical field stimulation was each blocked by NK1 receptor antagonism in human isolated mucosa (Moriarty et al., 2001). Further, gastric hyperalgesia involving mast cell degranulation may be inhibited by NK1 receptor blockade (Anton et al., 2001), raising the possibility that NK1 receptor antagonism might reduce human GI pain at least partly by modulating mechanisms by which extrinsic sensory neurones become sensitised.

Summary and potential for treatment of FBDs

NK1 receptor antagonists do not greatly affect normal GI functions. However, their antiemetic activity suggests an activity-dependent, defensive role for the NK1 receptor, operating via vagal sensory and motor pathways. It is not known if the same pathways play similar roles in conditions such as functional dyspepsia, but there is a need to study the effects of NK1 receptor antagonism on such disorders. Interactions between the NK1 receptor and NANC transmission also suggest a need to explore the role of this receptor in disrupted colonic motility. Finally, NK1 receptor antagonism may exert analgesic activity in humans, but similar studies have not been carried out for the gut, where an opportunity exists for NK1 receptor involvement in mucosal inflammatory or ‘irritant' processes.

NK3 Receptors

Gastro-vagal functions

Any involvement of the NK3 receptor in gastro-vagal neuropathophysiology is not clear. This lack of clarity exists in spite of the presence of ‘moderate' levels of NK3-Ir within the rat NTS and DVMN regions of the brainstem (Mileusnic et al., 1999). Electrophysiological studies indicate that the neurones of the NTS and DMVN do not respond to NKB or senktide (Maubach & Jones, 1997). However, intracerebroventricular, but not systemic administration of the NK3 receptor antagonist osanetant (SR-142,801) may block the ability of rectal distension to evoke colonic water secretion via capsaicin-sensitive, vagus-dependent mechanisms (Eutamene et al., 1997).

Gastrointestinal motility

Receptor and ligand distribution:

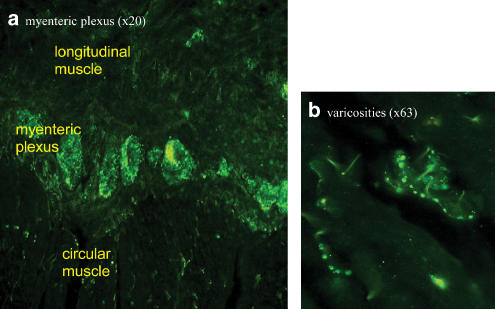

Tachykinins have been localised to intestinal intrinsic primary afferent neurones (IPANs) by immunohistochemistry and the cell bodies of myenteric IPANs bear NK3 receptors (Costa et al., 1996; Mann et al., 1997; Jenkinson et al., 1999; Lomax & Furness, 2000). These neurones are sensitive to chemical and/or mechanical stimuli and are characterised by morphology (short axon; multiple dendrites projecting to multiple enteric neurones), location (projecting circumferentially from the mucosa, with cell bodies in the myenteric and submucosal plexus) and electrophysiology (ability to generate slow excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) or slow postsynaptic excitation) (Clerc et al., 1999). An individual IPAN will synapse with additional IPANs, generating a slow-EPSP and thereby forming a self-reinforcing network. IPANs also transmit to longitudinally projecting excitatory and inhibitory inter-/ motor-neurones via fast- and slow-EPSPs. NK3 receptors are distributed to myenteric ascending excitatory and descending inhibitory motorneurones, and to secretomotor neurones. Finally, NK3 receptors are found in the submucosal plexus on secretomotor/vasodilator neurones, but not on IPANs (Jenkinson et al., 1999). Of the species examined, the receptors are found on myenteric neurones in guinea-pig gastric antrum and on myenteric and submucosal neurones in the ileum (Schemann & Kayser, 1991; Jenkinson et al., 1999). A similar distribution of the receptor has been reported in rat intestine myenteric and (to a lesser extent) submucosal neurones. However, NK3-Ir was absent in the stomach and oesophagus, where IPAN-like neurones are also thought to be absent (Grady et al., 1996; Mann et al., 1997). In the human sigmoid colon, intense NK3-Ir was detected in the myenteric and submucosal plexus, with no apparent difference in the relative intensities (Dass et al., 2002; Figure 1); NK3-Ir was not detected on longitudinal and circular muscle, or on the muscularis mucosa. A similar localisation of NK3-Ir was found in the human gastric fundus, but with apparently lower levels in the myenteric plexus.

Figure 1.

NK3 receptor immunoreactivity in the myenteric plexus of human sigmoid colon (NB Dass; reported in Dass et al., 2002). A rabbit anti-NK3 (438-452) receptor polyclonal antibody was used with an Alexa 488 conjugated secondary antibody. Intense NK3-Ir was detected in (a) the myenteric and submucosal plexus and (b) was clearly evident on varicose nerve fibres. NK3-Ir was not detected in smooth muscle cells, or in muscularis mucosa.

Each of the mammalian tachykinins is present within the gut, although compared with NKA and substance P, the amount of NKB may be low (Tsuchida et al., 1990). Nevertheless, since large amounts of NKA and substance P occur within the ENS, it is argued that NK3 receptors are activated by each of these tachykinins (Grady et al., 1996) released in amounts sufficent to activate the receptor, and in an ‘activity-dependent' manner (see Introduction). This is consistent with observations that enteric tachykinin-containing neurones are not associated with clusters of NK receptors, and that tachykinins diffuse for significant distances within the gut, as indicated by the detection of tachykinins in venous effluent (in vivo) or bathing solutions (in vitro) surrounding an intact intestine (see Jenkinson et al., 1999).

Gastric motility

NK3 receptor antagonists do not affect gastric tone or compliance in conscious dogs (Crema et al., 2002), or the gastric emptying of a liquid phenol red meal in conscious rats (Table 1 ). These data suggest that NK3 receptors play no role in the control of normal gastric emptying. Further experiments are required to determine if NK3 receptors can mediate disturbances in gastric motility.

Table 1.

Effects of the NK3 receptor antagonist talnetant (SB-223412), on gastrointestinal motility in conscious rats. (a) The effects on gastric emptying were measured 45 min after administration of a liquid phenol-red test meal in conscious rats (Tache et al., 1987). (b) Effects on GI motility were measured 30 min after oral dosing of a charcoal meal to conscious rats (Takemori et al., 1969)

| Groupa | Oral treatment | Dose (mg/kg) | % gastric emptying | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenol red only | — | 0.0 | |

| 2 | Vehicle | — | 60.6 | |

| 3 | Talnetant | 5 | 55.2 | |

| 4 | Talnetant | 15 | 50.7 | |

| 5 | Talnetant | 50 | 62.4 | |

| 6 | Morphine sulphate | 20 | 30.8** | |

| Groupb | Oral treatment | Dose (mg/kg) | Group mean distance travelled by charcoal as % of total gut length±s.d. | % change from vehicle-treated animals |

| 1 | Vehicle | — | 53.0±7.6 | − |

| 2 | Talnetant | 5 | 46.9±5.3 | −11.5 |

| 3 | Talnetant | 15 | 52.1±7.1 | −1.7 |

| 4 | Talnetant | 50 | 50.4±8.6 | −4.9 |

| 5 | Morphine sulfate | 10 | 37.4±12.4 | −29.4 |

Significance of difference from the vehicle-treated group: P<0.01 (ANOVA followed by William's test; talnetant groups, or Student's t-test; morphine).

Statistical significance of difference from the vehicle-treated group: **P<0.01 (as above). The doses of talnetant were selected to antagonise at the rat NK3 receptor (Sarau et al., 1997) and were similar to those inhibit rat intestinal anti-nociceptive activity (Fioromonti et al., 2003). s.d.=standard deviation.

Intestinal motility

A major function of intestinal NK3 receptors appears to be linked to the role of the IPANs. Transmission between IPANs, via slow EPSPs, is unaffected by NK1 receptor ligands (Neunlist et al., 1999) but greatly inhibited by NK3 receptor antagonists in guinea-pig intestine (Neunlist et al., 1999; Alex et al., 2001; Sanger et al., 2002). NK3 receptors may also be involved in polarised reflexes of the intestine, possibly via transmission between IPANs or between IPANs and ascending or descending interneurons. Thus, experiments with senktide, which activates and desensitises NK3 receptors, suggest that IPAN-evoked activation of the ascending excitatory pathway in guinea-pig intestine may be mediated by ACh and/or by tachykinins, acting at NK3 receptors (Johnson et al., 1996). NK3 receptors may also play a role in the descending inhibitory pathways (Johnson et al., 1998), involving NO-dependent and -independent neurotransmission (Lecci et al., 1996).

Distension-evoked activation of IPANs may not normally release tachykinins. This suggestion is possible because NK3 receptor antagonism does not affect distension-evoked peristalsis in guinea-pig ileum (Holzer et al., 1998; B. Tuladhar, unpublished), in pig ileum (Schmidt & Hoist, 2002) or the hexamethonium-resistant propulsive movements of rat isolated colon (Lecci et al., 1996). Similarly, the NK3 receptor antagonist talnetant (0.01, 0.1, 1.0 μM) did not affect neuronally-mediated, electrically-evoked contractions of human isolated taenia coli (unpublished) or rat gastro-caecal transit times (Table 1). Finally, NK3 receptor antagonism did not affect baseline short-circuit current in guinea-pig colonic mucosa (e.g., Goldhill & Angel, 1998; Frieling et al., 1999). Exceptions to these findings of inactivity are the ability of NK3 receptor antagonism to facilitate the amplitude of giant contractions in rat isolated colon (Gonzalez & Sarna, 2001), or ‘submaximal' propulsion in rabbit isolated colon (Onori et al., 2001), a preparation in which prokinetic activity may also be evoked by NK1 receptor antagonism (Onori et al., 2003).

Evidence is now emerging to suggest that when IPANs are activated by a stimulus more intense than that required to evoke peristalsis, these neurones release tachykinins to activate NK3 receptors on connecting IPANs and possibly elsewhere, to change intestinal motility and sensations. Prior to the availability of selective NK3 receptor antagonists, clues to this function could be found using exogenously applied tachykinins. For example, the NK3 receptor agonist senktide may activate NO-dependent and –independent, neuronally mediated circular muscle relaxation in guinea-pig colon (Giuliani & Maggi, 1995), facilitate ACh release from the myenteric plexus (Yau et al., 1992), stimulate and inhibit propulsive activity in rabbit distal colon (Onori et al., 2001), increase colonic spike bursts in conscious rats (Julia et al., 1999), facilitate the sensitivity to induction of peristalsis by intraluminal distension (Holzer et al., 1995), increase intestinal transit in conscious rats (Chang et al., 1999) and induce Cl− secretion by guinea-pig colonic mucosa (but not in pig jejunum; Thorboll et al., 1998) (e.g., Goldhill & Angel, 1998; Frieling et al., 1999). To investigate the role of endogenous tachykinins in ‘disrupted' intestinal movements, we studied the effects of talnetant on intestinal reflexes evoked by ‘supramaximal' mechanical stimuli. We looked for an ability to influence polarised reflexes in intact guinea-pig isolated colon (Sanger et al., 2002), by the application of 6, 12 and 20 g weights to evoke contractions oral to the distension and small relaxations on the anal side; the amplitude of the contractions appeared to be independent of the load applied and all changes were prevented by nicardipine. Talnetant reduced the amplitudes of ascending excitatory reflexes and antagonised or even reversed the descending inhibitory reflexes. Significantly, these effects appeared to be greater when the heavier weights were used to generate the reflexes. Thus, these data could be explained if tachykinins were released from the IPANs by the increasingly greater degrees of stretch, to induce slow EPSPs via activation of NK3 receptors and as a consequence, changes in the excitability of the polarised reflexes. Consistent with this hypothesis are electrophysiological experiments which show that slow EPSPs are graded with the frequency of activity in presynaptic fibres, with maximum amplitudes of slow EPSPs occurring in response to stimulation of inputs at 10 Hz or more (Morita & North, 1985).

Furness et al. (2002) showed that the NK3 receptor antagonist SR 142901 did not affect excitatory enteric reflex activity in rat isolated colon induced by a submaximal degree of stretch (1.5 g). However, an effect of NK3 receptor antagonism became apparent after sensitisation by repeat-distensions and during the combined presence of an NK1 receptor antagonist. Consequently, these data remain consistent with the hypothesis that NK3 receptors play a role in disrupted patterns of intestinal motility induced by relatively intense IPAN stimulation, while sparing reflexes evoked by milder stimulation. To further explore this idea, the effects of talnetant 250 nM were studied on peristalsis evoked in guinea-pig isolated ileum by ‘optimal' and ‘excessive' intraluminal distension (B Tuladhar, unpublished). Peristaltic waves elicited by optimal distension pressures (1.2–3 cmH2O) were unaffected by talnetant, but the number of peristaltic events and thus, the efficiency of the peristaltic reflex was increased by talnetant when higher pressures (3.5 or 4 cmH2O) were used. Together with the stretch experiments described above, it is suggested that NK3 receptor antagonists have a role in mediating intestinal reflexes evoked by ‘supraoptimal' stimuli.

Pain

NK3 receptors are present within the intrinsic neurones of the spinal cord, where they have functional activity (see Fioramonti et al., 2003 for references). Further, intrathecal administration of NK3 receptor antagonists reduces rat behavioural responses to noxious colo-rectal distension (Kamp et al., 2001; Gaudreau & Plourde, 2003). NK3-Ir appears to be absent in normal adult rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG; Ding et al., 1996; Seybold et al., 1997), but NKB-evoked responses were detected by whole patch clamp in cultured capsaicin-sensitive neurones from rat DRG (Inoue et al., 1995) and a functional NK3 receptor may be present on capsaicin-sensitive nerve terminals within rat spinal cord, possibly activated by NKB released from intrinsic spinal neurones (Schmid et al., 1998). The latter suggests that NK3 receptors will also be distributed to C-fibre nerve terminals within the intestine and this is supported by the ability of NK3 receptor antagonism to reduce capsaicin-evoked, tetrodotoxin-sensitive contractions of guinea-pig isolated ileum or oesophagus (Bartho et al., 1999).

Selective NK3 receptor antagonists, administered systemically, reduce nociceptive behaviour caused by colo-rectal distension in conscious rats (Julia et al., 1999; Fioramonti et al., 2003). Such activity was not seen when measuring pseudoaffective vascular responses to jejunal distension in anaesthetised rats (McLean et al., 1998), but mismatches between these methods of assessing intestinal nociception have previously been reported (Banner & Sanger, 1995). Julia et al. (1999) found that the antinociceptive effect was not mimicked by intracereboventricular administration of the same antagonist. Further, NK3 receptor antagonism reduced distension-evoked spinal afferent nerve discharge from the intestine but did not do the same when distension was applied to the urinary bladder, an organ that does not possess IPAN's. The explanation for this organ-dependent difference is not clearly understood (see editorial by Mayer & Marvizon, 1999, for a discussion of these data), but the following was suggested. Firstly, central NK3 receptors play only a minimal role in modulating intestinal nociception. Secondly, although a supraspinal site of action could not be excluded, it becomes a possibility that IPAN activity plays a role in the mechanism of action on the gut. Thus, the tachykinins released from intestinal IPANs may increase the sensitivity of spinal afferent nerve terminals within the intestine via a localised change in muscle tension and/or by direct activation of NK3 receptors on these nerve terminals.

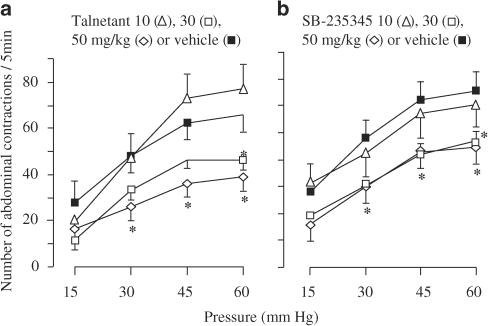

The hypothesis of a ‘peripheral' site of action to explain the antinociceptive activity of NK3 receptor antagonists receives support from Fioramonti et al. (2003). These authors used the rat colo-rectal distension model to compare the anti-nociceptive activity of orally administered talnetant with that of SB-235375, a selective NK3 receptor antagonist with no measureable ability to enter the brain or spinal cord (see also Shafton et al., 2004, for pharmacokinetic data on SB-235375). SB-235375 exerted antinociceptive activity of potency and magnitude similar to that of talnetant (Figure 2). Shafton et al. (2004) also used SB-235375 to show that this compound inhibited nociceptive responses to brief colo-rectal distension, at doses that had no effects on similar nociceptive responses evoked by skin pinch; both nociceptive behaviours were measured as a visceromotor response via electromyograph recordings from the external oblique muscle of the abdomen. These results are consistent with an intestinal specificity of antinociceptive activity, first reported by Julia et al. (1999).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of responses to colo-rectal distension in conscious rats by the selective NK3 receptor antagonists talnetant and SB-235375 (Fioramonti et al., 2003). The effects of isobaric colo-rectal distension were assessed by measuring the number of abdominal contractions induced by increasing pressures of distension. Talnetant (a) or SB-235345 (b) was dosed orally and the effects were compared with vehicle; n=10 each, *P<0.05 vs vehicle. Unlike talnetant, SB-235345 had no measurable ability to cross the rat blood–brain barrier into the brain or spinal cord (see also, Shafton et al., 2004).

Summary and potential for treatment of FBDs

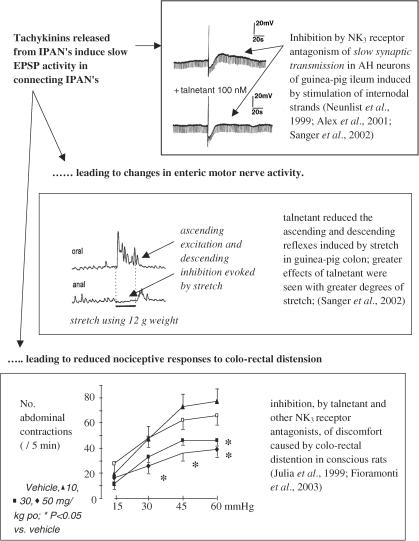

Antagonism at the receptor has little or no ability to modulate normal GI motility. However, NK3 receptors may play a role in disrupted intestinal motility (Figure 3). It is hypothesised that during these conditions, the current data also point to a ‘peripheral', possibly IPAN-mediated mechanism whereby NK3 receptor antagonists inhibit intestinal nociception. Thus, the above hypothesis further proposes that neurokinins released from the IPANs can affect C-fibre sensitivity, either indirectly by affecting smooth muscle tension or directly by activation of NK3 receptors located on C-fibre terminals within the intestine. To achieve this activity, IPANs and intestinal C-fibre terminals do not necessarily have to make synaptic contact, as tachykinins are known to diffuse for significant distances.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms by which NK3 receptors may play a role in disrupted intestinal motility and sensations.

NK3 receptor antagonism may also reduce certain effects of immune (IgE and IgG serum litres reduced after sensitisation to cow's milk, but the increase in intestinal mast cell numbers was reduced only by NK1 receptor antagonism; Gay et al., 1999) and inflammatory (TNBS-induced neurogenic colitis reduced by NK3 or NK2 receptor antagonism in guinea-pigs; Mazelin et al., 1998) stimuli on gut function. The mechanisms of these actions are unclear, but as for the above studies on intestinal motility and sensation, the data are consistent with an activity-dependent role for the receptor.

Conclusions

NK1 and NK3 receptors do not seem to play major roles in normal GI physiology, but evidence suggests that the receptors can be activated in an activity-dependent manner, indicating roles in ‘defensive' and/ or pathological GI functions. In terms of FBDs, the role of the NK1 receptor is unclear, but clinical studies involving gastro-vagal reflexes, intestinal motility and GI pain have yet to be performed. Recent studies with talnetant and other selective NK3 receptor antagonists are beginning to open up an exciting and novel pathway by which pathological changes in intestinal motility and nociception can be induced, suggesting a role for NK3 receptor antagonism in IBS.

Acknowledgments

Collegues and collaborators are acknowledged for stimulating discussions over the years: Drs Narinda Dass, Douglas Hay, Tachi Yamada, Lionel Bueno and Bishwa Tuledhar, and Professors John Furness and Paul Andrews.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AP

area postrema

- cmH2O

cm of water

- DMVN

dorsal motor vagal nucleus

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- EC cel

enterochromaffin cell

- ENS

enteric nervous system

- FBD

functional bowel disorder

- GI

gastrointestinal

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- ICC

interstitial cells of cajal

- IPAN

intrinsic primary afferent neurone

- LES

lower esophageal sphincter

- NANC, non-adrenergic

non-cholinergic

- NKA

neurokinin A

- NKB

neurokinin B

- NK1

neurokinin1

- NK2

neurokinin2

- NK3

neurokinin3

- NK1-Ir

NK1 receptor immunmoreactivity

- NO

nitric oxide

- NTS

nucleus Tractus solitarius

- Slow EPSP

slow excitatory postsynaptic potential

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

References

- ALEX G., KUNZE W.A.A., FURNESS J.B., CLERC N. Comparison of the effects of neurokinin-3 receptor blockade on two forms of slow synaptic transmission in myenteric AH neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;104:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDREWS P.L.R., RUDD J.A.The role of tachykinins and the neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor in nausea and emesis Handbook Exp. Pharmacol. 2004(in press)

- ANDREWS P.L.R., SANGER G.J. Abdominal vagal afferent neurones: an important target for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2002;2:650–656. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANTON P.M., THEODOROU V., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Chronic low-level administration of diquat increases the nociceptive response to gastric distension in rats: role of mast cells and tachykinin receptor activation. Pain. 2001;92:219–227. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNER S.E., SANGER G.J. Differences between 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in modulation of visceral hypersensitivity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:558–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARBARA G., STANHELLINI V., DE GIORGIO R., CREMON C., COTRELL G.S., SANTINI D., PASQUINELLI G., MORSELLI-LABATE A.M., GRADY E., BUNNETT N.W., COLLINS S.M., CORINALDESI R. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:693–702. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARTHO L., LENARD L., PATACCHINI R., HALMAI V., WILHELM M., HOLZER P., MAGGI C.A. Tachykinin receptors are involved in the ‘local efferent' motor response to capsaicin in the guinea-pig small intestine and oesophagus. Neuroscience. 1999;90:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIAN, X-C, BERTRAND P.P., FURNESS J.B., BORNSTEIN J.C. Evidence for functional NK1-tachykinin receptors on motor neurones supplying the circular muscle of guinea-pig small and large intestine. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2000;12:307–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLACKSHAW L.A., DENT J. Lower oesophageal sphincter responses to noxious oesophageal chemical stimuli in the ferret: involvement of tachykinin receptors. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1997;66:189–200. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(97)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLONDEAU C., CLERC N., BAUDE A. Neurokinin-1 and Neurokinin-3 receptors are expressed in vagal efferent neurons that innervate different parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Neuroscience. 2002;110:339–349. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADESI S., EUTAMENE H., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Acute restraint stress activates functional NK1 receptor in the colon of female rats: Iinvolvement of steroids. Gut. 2002;50:349–354. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENAC N., GARCIA-VILLAR R., FERRIER L., LARAUCHE M., VERGNOLLE N., BUNNETT N.W., COELHO A.M., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Proteinase-activated receptor-2-induced colonic inflammation in mice: possible involvement of afferent neurons, nitric oxide and paracellular permeability. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4296–4300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG F.Y., LEE S.D., YEH G.H., WANG P.S. Rat gastrointestinal motor responses mediated via activation of neurokinin receptors. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1999;14:39–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLERC N., FURNESS J.B., KUNZE W.A.A., THOMAS E.A., BERTRAND P.P. Long-term effects of synaptic activation at low frequency on excitability of myenteric AH neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;90:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTA M., BROOKES S.J.H., STEELE P.A., GIBBINS I., BURCHER E., KANDIAH C.J. Neurochemical classification of myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig ileum. Neuroscience. 1996;75:949–967. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CREMA F., MORO E., NARDELLI G., DE PONTI F., FRIGO G., CREMA A. Role of tachykinergic and cholinergic pathways in modulating canine gastric tone and compliance in vivo. Pharmacol. Res. 2002;45:341–347. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2002.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DASS N.B., BASSIL A., MORGAN M., SANGER G.J.Localisation and distribution of functional neurokinin-3 (NK3) receptors in human gastrointestinal tract Gastroenterology 2002122Suppl. 1Abstract M1033 [Google Scholar]

- DE PONTI F., CREMA F., MORO E., NARDELLI G., CROCI T., FRIGO G.M. Intestinal motor stimulation by the 5-HT4 receptor agonist ML10302: differential involvement of tachykinergic pathways in the canine small bowel and colon. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2001;13:543–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING Y.-Q., SHIGEMOTO R., TAKADA M., OHISHI H., NAKANISHI S., MIZUNO N. Localization of the neuromedin K receptor (NK3) in the central nervous system of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;364:290–310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960108)364:2<290::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUTAMENE H., THEODOROU V., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Rectal distension-induced colonic net water secretion in rats involves tachykinins, capsaicin sensory and vagus nerves. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1595–1602. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIORAMONTI J., GAULTIER E., TOULOUSE M., SANGER G.J, BUENO L. Intestinal anti-nociceptive behaviour of NK3 receptor antagonism in conscious rats: evidence to support a peripheral mechanism of action. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2003;15:363–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIELING T., DOBREVA G., WEBER E., BECKER K., RUPPRECHT C., NEUNLIST M., SCHEMANN M. Different tachykinin receptors mediate chloride secretion in the distal colon through activation of submucosal neurones. Naunyn-Schmeideberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1999;359:71–79. doi: 10.1007/pl00005327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURNESS J.B., KUMANO K., LARSSON H., MURR E., KUNZE W.A.A., VOGALIS F. Sensitization of enteric reflexes in the rat colon in vitro. Auton. Neurosci. 2002;97:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUDREAU G.-A., PLOURDE V. Role of tachykinin NK1, NK2 and NK3 receptors in the modulation of visceral hypersensitivity in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;351:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAY J., FIORAMONTI J., GARCIA-VILLAR R., EDMONDS-ALT X., BUENO L. Involvement of tachykinin receptors in sensitisation to cow's milk proteins in guinea-pigs. Gut. 1999;44:497–503. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIULIANI S., MAGGI C.A. Effect of SR 142801 on nitric oxide-dependent and independent responses to NK3 receptor antagonists in isolated guinea-pig colon. Naunyn-Schmeideberg's, Arch. Pharmacol. 1995;352:512–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00169385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDHILL J., ANGEL I. Mechanism of tachykinin NK3 receptor-mediated colonic ion transport in the guinea-pig. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;363:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ A., SARNA S.K. Neural regulation of in vitro giant contractions in the rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;281:G275–G282. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRADY E.F., BALUK P., BOHM S., GAMP P.D., WONG H., PAYAN D.G., ANSEL J., PORTBURY A.L., FURNESS J.B., MCDONALD D.M, BURNETT N.W. Characterisation of antisera specific to NK1, NK2 and NK3 neurokinin receptors and their utilization to localise receptors in the rat gastrointestinal tract. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6975–6986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06975.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENWOOD-VAN MEERVELD B., GIBSON M.S., JOHNSON A.C., VENKOVA K., SUTKOWSKI-MARKMANN D. NK1 receptor-mediated mechanisms regulate colonic hypersensitivity in the guinea-pig. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;74:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAHN A., STORR M., ALLESCHER H.-D. Effect of tachykinins on ascending and descending reflex pathway in rat small intestine. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2002;23:289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL R. NK1 (substance P) receptor antagonists — why are they not analgesic in humans. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:244–246. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLOWAY R.H., DENT J. Medical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease — beyond the proton pump inhibitors. Dig. Dis. 2000;18:7–13. doi: 10.1159/000016928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLZER P., HOLZER-PETSCHE U. Tachykinin receptors in the gut: physiological and pathological implications. Curr. Opinion Pharmacol. 2001;1:583–590. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLZER P., LIPPE I.T., HEINEMANN A., BARTHO L. Tachykinin NK1 and NK2 receptor mediated control of peristaltic propulsion in the guinea-pig small intestine in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLZER P., SCHLUET W., MAGGI C.A. Ascending enteric reflex contraction: roles of acetylcholine and tachykinins in relation to distension and propagation of excitation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;264:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLZER P., SCHLUET W., MAGGI C.A. Substance P stimulates and inhibits intestinal peristalsis via distinct receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:322–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUBER O., BERTRAND C., BUNNETT N.W., PELLEGRINI C.A., NADEL J.A., NAKAZATO P., DEBAS H.T., GEPPETTI P. Tachykinins mediate contraction of the human lower esophageal sphincter in vitrovia activation of NK-2 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;239:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90982-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IKEDA K., MIYATA K., KUBOTA H., YAMADA T., TOMIOKA K. RP67580, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, decreased restraint stress-induced defecation in rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;198:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11972-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INOUE K., NAKAZAWA K., INOUE K., FUJIMORI K. Nonselective cation channels coupled with tachykinin receptors in rat sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:736–742. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENKINSON K.M., MORGAN J.M., FURNESS J.B., SOUTHWELL B.R. Neurons bearing NK3 tachykinin receptors in the guinea-pig ileum revealed by specific binding of fluorescently labelled agonists. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112:233–246. doi: 10.1007/s004180050411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN J.G., MISRA S., GRIDER J.R., MAKHLOUF G.M. Functional differences between SP and NKA relaxation of gastric muscle by SP is mediated by VIP and NO. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;264:G678–G685. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.4.G678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOCIC M., SCHULIGOI R., SCHONINKLE E., PABST M.A., HOLZER P. Cooperation of NMDA and tachykinin NK1 and NK2 receptors in the medullary transmission of vagal afferent input from the acid-threatened rat stomach. Pain. 2001;89:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON P.J., BORNSTEIN J.C., YUAN S.Y., FUNESS J.B. Analysis of contributions of acetylcholine and tachykinins to neuro-neuronal transmission in motility reflexes in the guinea-pig ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:973–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON P.J., BORNSTEIN J.C., BURCHER E. Roles of neuronal NK1 and NK3 receptors in synaptic transmmission during motility reflexes in the guinea-pig ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1375–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JULIA V., MORTEAU O., BUENO L. Involvement of neurokinin 1 and 2 receptors in viscerosensitive response to rectal distension in rats. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:94–102. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JULIA V., SU X., BUENO L., GEBHART G.F. Role of neurokinin 3 receptors on responses to colorectal distension in the rat: electrophysiological and behavioural studies. Gastroenterol. 1999;116:1124–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMP E.H., BECK D.R., GEBHART G.F. Combinations of neurokinin receptor antagonists reduce visceral hyperalgesia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROWICKI Z.K., HORNBY P.J. Substance P in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus evokes gastric motor inhibition via neurokinin 1 receptor in rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LADIC L.A., BUCHAN A.M.J. Association of substance P and its receptor with efferent neurons projecting to the greater curvature of the rat stomach. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1996;58:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(96)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAIRD J.M.A., OLIVAR T., ROZA C., DE FELIPE C., HUNT S.P., CERVERO F. Deficits in visceral pain and hyperalgesia of mice with a disruption of the tachykinin NK1 receptor gene. Neuroscience. 2000a;98:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAIRD J.M.A., ROZA C., DE FELIPE C., HUNT S.P., CERVERO F. Role of central and peripheral tachykinin NK1 receptors in capsaicin-induced pain and hyperalgesa in mice. Pain. 2000b;90:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LECCI A., GIULIANI S., TRAMONTANA M., MEINI S., DE GIORGIO R., MAGGI C.A. In vivo evidence for the involvement of tachykinin NK3 receptors in the hexamethonium-resistant inhibitory transmission in the rat colon. Naunyn-Schmeideberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:671–679. doi: 10.1007/BF00167186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LECCI A., DE GIORGIO R., BARTHO L., STERNINI C., TRAMONTANA M., CORINALDESI R., GIULLANI S., MAGGI C.A. Tachykinin NK1 receptor-mediated inhibitory responses in the guinea-pig small intestine. Neuropeptides. 1999;33:91–97. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS L.A., TRAVAGLI R.A. Effects of substance P on identified neurons of the rat dorsal mtor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;281:G164–G172. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMAX A.E.G., BERTRAND P.P., FURNESS J.B. Identification of the populations of enteric neurons that have NK1 tachykinin receptors in the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;294:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s004410051153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMAX A.E.G., FURNESS J.B. Neurochemical classification of enteric neurons in the guinea-pig distal colon. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;302:59–73. doi: 10.1007/s004410000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGGI C.A. The troubled story of tachykinins and neurokinins. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:173–175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANN P.T., SOUTHWELL B.K., DING Y.Q., SHIGERMOTO R., MIZURNO N., FUNESS J.B. Localisation of neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor immunoreactivity in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;289:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s004410050846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYER E.A., MARVIZON J.C. Neurokinin 3 receptors in the gut: A new target for the treatment of visceral pain. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1250–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAUBACH K.A., JONES R.S. Electrophysiological characterisation of tachykinin receptors in the rat nucleus of the solitary tract and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZELIN L., THEODOROU V., MORE J., EMONDS-ALT X., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Comparative effects of nonpeptide tachykinin receptor antagonists on experimental gut inflammation in rats and guinea-pigs. Life Sci. 1998;63:293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLEAN P.G., GARCIA-VILLAR R., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Effects of tachykinin receptor antagonists on the rat jejunal distension pain response. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;345:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEZIES J.R., MCKEE R., CORBETT A.D. Differential alterations in tachykinin NK2 receptors in isolated colonic circular smooth muscle in inflammatory bowel disease and idiopathic chronic constipation. Reg. Peptides. 2001;99:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHL T., JOCIC M., SCHULIGOI R., HOLZER P. Role of tachykinin receptors in the central processing of afferent input from the acid-threatened rat stomach. Reg. Peptides. 2001;102:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEUSNIC D., LEE J.M., MAGNUSON D.J., HEJNA M.J., KRAUSE J.E., LORENS JB., LORENS S.A. Neurokinin-3 receptor distribution in rat and human brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 1999;89:1269–1290. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINAMI M., ENDO T., YOKOTA H., OGAWA T., NEMOTO M., HAMAUE N., HIRAFUJI M., YOSHIOKA M., NAGAHISA A., ANDREWS P.L.R. Effects of CP-99, 994, a tachykinin receptor antagonist, on abdominal afferent vagal activity in ferrets: evidence for involvement of NK1 and 5-HT3 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;428:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITOLO-CHIEPPA D., MANSI G., NACCI C., DE SALVIA M.A., MONTAGNANI M., POTENZA M.A., RINALDI R., LERRO G., SIRO-BRIGIANI G., MITOLO C.I., RINALDI M., ALTOMARE D.F. Idiopathic chronic constipation: tachykinins as co-transmitters in colonic contraction. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;31:349–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIARTY D., GOLDHILL J., SELVE N., O'DONOGHUE D.P., BAIRD A.W. Human colonic anti-secretory activity of the potent NK1 antagonist SR140133: assessment of potential anti-diarrheal activity in food allergy and inflammatory bowel disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;133:1346–1354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORITA K., NORTH R.A. Significance of slow synaptic potentials for transmission of excitation in guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Neuroscience. 1985;14:661–672. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NESS T.J., RANDICH A., FILLINGIM R., FAUGHT R.E., BACKENSTO E.M.Left vagus nerve stimulation suppresses experimentally induced pain Neurology 200156986–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUNLIST M., DOBREVA G., SCHEMANN M. Characteristics of mucosally projecting myenteric neurones in the guinea-pig proximal colon. J. Physiol. 1999;517.2:533–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0533t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKANO S., NAGAYA H., IKEURA Y., NATSUGARI H., INATOMI N. Effects of TAK-637, a novel neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, on colonic function in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;298:559–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONORI L., AGGIO A., TADDEI G., CICCOCIOPPO R., SEVERI C., CARNICELLI V., TONINI M. Contribution of NK3 tachykinin receptors to propulsion in the rabbit isolated distal colon. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2001;13:211–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONORI L., AGGIO A., TADDEI G., LORETO M.F., CICCOCIOPPO R., VICINI R., TONINI M. Peristalsis regulation by tachykinin NK1 receptors in the rabbit isolated distal colon. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:G325–G331. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00411.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'SULLIVAN M., CLAYTON N., BRESLIN N.P., HARMAN I., BOUNTRA C., MCLAREN A., O'MORAIN C.A. Increased mast cells in the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2000;12:449–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RETTENBACHER M., REUBI J.C. Localization and characterisation of neuropeptide receptors in human colon. Naunyn-Schmeideberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:291–304. doi: 10.1007/s002100100454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SABAN R., NGUYEN, N-B, SABAN M.R., GERARD N.P., PASRICHA P.J. Nerve-mediated motility of ileal segments isolated from NK1 receptor knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G1173–G1179. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANGER G.J., ALEX G., SHAFTON A.D., FURNESS J.B. NK3 receptor antagonism by talnetant (SB-223412) suggests a role for NK3 receptors in enteric reflexes evoked by relatively intense stimuli. Gastroenterology. 2002;122 Suppl. 1:A-256. [Google Scholar]

- SARAU H.M., GRISWOLD D.E., POTTS W., FOLEY J.J., SCHMIDT D.B., WEBB E.F., MARTIN L.D., BRAWNER M.E., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., MEDHURST A.D., GIARDINA G.A., HAY D.W. Nonpeptide tachykinin receptor antagonists. I. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterisation of SB-223412, a novel, potent and selective neurokinin-3 receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;281:1303–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEMANN M., KAYSER H. Effects of tachykinins on myenteric neurones of the guinea-pig gastric corpus: involvement of NK-3 receptors. Pflugers Arch. 1991;419:566–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00370296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMID G., CARITA F., BONANNO G., RAITERI M. NK-3 receptors mediate enhancement of substance P release from capsaicin-sensitive spinal cord afferent terminals. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:621–626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT P.T., HOIST J.J. Tachykinin NK1 receptors mediate atropine-resistant net aboral propulsive complexes in porcine ileum. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;37:531–535. doi: 10.1080/00365520252903062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEYBOLD V.S., GRKOVIC I., PORTBURY A.L., DING, Y-Q, SHIGEMOTO R., MIZUNO N., FURNESS J.B., SOUTHWELL B.R. Relationship of NK3 receptor-immunoreactivity to subpopulations of neurons in rat spinal cord. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;381:439–448. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970519)381:4<439::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAFTON A.D., BOGESKI G., KITCHENER P.D., LEWIS A.V., SANGER G.J., FURNESS J.B.Effects of the peripheral acting NK3 receptor antagonist, SB-235375, on intestinal and somatic nociceptive responses and on intestinal motility Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 2004(in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- SMID S.D., LYNN P.A., TEMPLETON R., BLACKSHAW L.A. Activation of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic inhibitory pathways by endogenous and exogenous tachykinins in the ferret lower oesophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterol. Mot. 1998;10:149–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1998.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONEA I.M., PALMER M.V., AKILI D., HARP J.A. Treatment with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist reduces severity of inflammatory bowel disease induced by Cryptosporidium parvum. Clin. Diag. Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:333–340. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.333-340.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUTHWELL B.R., WOODMAN H.L., ROYAL S.J., FURNESS J.B. Movement of villi induces endocytosis of NK1 receptors in myenteric neurons from guinea-pig ileum. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s004410051032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUZA D.G., MENDONCA V.A., CASTRO M.S.D., POOLE S., TEIXEIRA M.M. Role of tachykinin NK receptors on the local and remote injuries following ischaemia and reperfusion of the superior mesenteric artery in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:303–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUCCHI A.F., SHEBANI K.O., LEEMAN S.E., WANG, C-C, REED K.L., FRUIN A.B., GOWER A.C., MCCLUNG J.P., ANDRY C.D., O'BRIEN M.J., POTHOULAKIS C., BECKER J.M. A neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist reduces an ongoing ileal pouch inflammation and the response to a subsequent inflammatory stimulus. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:G1259–G1267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00063.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TACHE Y., MAEDA-HAGIWARA M., TURKELSON C.M. Central nervous system action of corticotropin-releasing factor to inhibit gastric emptying in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:G241–G245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.253.2.G241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEMORI A.E., KUPFERBERG H.J., MILLER J.W. Quantitative studies of the antagonism of morphine by nalorphine and naloxone. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1969;169:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORBOLL J.E., BINDSLEV N., HANSEN M.B., SCHMIDT P., SKADHAUGE E. Functional characterisation of tachykinin receptors mediating ion transport in porcine jejunum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;359:271–279. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TONINI M., SPELTA V., DE PONTI F., DE GIORGIO R., D'AGOSTINO G., STANGHELLINI V., CORINALDESI R., STERNINI C., CREMA F. Tachykinin-dependent and-independent components of peristalsis in the guinea-pig isolated distal colon. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:938–945. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUB R.J., SENGUPTA JN., GEBHART G.F. Differential c-fos expression in the nucleus of the solitary tract and spinal cords following noxious gastric distension in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;74:873–884. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUKAMOTO M., SARNA S.K., CONDON R.E. A novel motility effect of tachykinins in normal and inflamed colon. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:G1607–G1614. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.6.G1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUCHIDA K., SHIGEMOTO R., YOKOTA Y., NAKANISHI S. Distribution and localisation of neurokinin A-like immunoreactivity and neurokinin B-like immunoreactivity in rat peripheral tissue. Regul. Pept. 1990;30:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(90)90094-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANNUCCHI M.-G., FAUSSONE-PELLEGRINI M.-S. NK1, NK2 and NK3 tachykinin receptor localization and tachykinin distribution in the ileum of the mouse. Anat. Embryol. 2000;202:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s004290000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON J.W., NAGAHISA J.B., LUCOT J.B., ANDREWS P.L.R.The tachykinins and emesis: Towards complete control Serotonin and the Scientific Basis of Anti-Emetic Therapy 1995Oxford: Oxford Clinical Communications; 233–238.ed. Reynolds D.J.M., Andrews P.L.R., Davis C.J. pp [Google Scholar]

- YAU W.M., MANDEL K.G., DORSETT J.A., YOUTHER M.L. Neurokinin 3 receptor regulation of acetylcholine release from myenteric plexuses. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:G659–G664. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.5.G659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAGORODNYUK V., SANTICIOLI P., TURINI D., MAGGI C.A. Tachykinin NK1 and NK2 receptors mediate non-adrenergic non-cholinergic excitatory neuromuscular transmission in the human ileum. Neuropeptides. 1997;31:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(97)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]