Abstract

Ammonia and methylamine (MET) are endogenous compounds increased during liver and renal failure, Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and diabetes, where they alter some neurobehavioural functions probably acting as potassium channel blockers.

We have already described that potassium channel blockers including tetraethylammonium (TEA), ammonia and MET are hypophagic in mice. Antisense oligonucleotides (aODNs) against Shaker-like Kv1.1 gene abolished the effect of TEA but not of ammonia and MET.

The central effects elicited in fasted mice by ammonia and MET were further studied. For MET, an ED50 value 71.4±1.8 nmol mouse−1 was calculated. The slope of the dose–response curves for these two compounds and the partial hypophagic effect elicited by ammonia indicated a different action mechanism for these amines.

The aODNs pretreatments capable of temporarily reducing the expression of all seven known subtypes of Shaker-like gene or to inactivate specifically the Kv1.6 subtype abolished the hypophagic effect of MET but not that of ammonia.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, Western blot and immunohistochemical results indicate that a full expression in the brain of Kv1.6 is required only for the activity of MET, and confirms the different action mechanism of ammonia and MET.

Keywords: Ammonia, methylamine, mouse, antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides, Kv1.6 channels, food intake

Introduction

Methylamine (MET), a short aliphatic amine present in mammals, derives from the endogenous deamination of adrenaline, sarcosine, creatinine and lecithin, or from food and drink (Zeisel & Da Costa, 1986; Buffoni, 1995). Ammonia (NH3) shares with MET some metabolic properties in vertebrates also resulting from the endogenous or exogenous catabolism of amino acids and proteins or from the oxidative deamination of different amines (Cooper & Plum, 1987).

Although an increase in the urinary excretion of MET during pregnancy, parturition and muscular exertion has been observed (Dar et al., 1985; Precious et al., 1988), the general physiological significance of this short aliphatic amine, less investigated than NH3, is far from being completely clarified.

Experimental and clinical studies point to the important pathological role of NH3, MET and other basic compounds, such as neurotoxins (Szerb & Butterworth, 1992; Raabe, 1994; Butterworth, 2000; Olde Damink et al., 2002). These weak bases increase in hyperammoniaemias during liver or renal diseases (Simenhoff, 1975; Baba et al., 1984; Yu & Dyck, 1998) or in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia (Seiler, 2002; Yu et al., 2003), altering, depending on the tissue levels reached, the metabolism, morphology and excitability of central tissues. In diabetes, the increased endogenous levels of MET are suspected of having a role in central and peripheral vascular degeneration because of the formation, from its oxidative deamination, of the angiotoxic compounds formaldehyde and H2O2 (Yu et al., 2003).

A common feature of NH3 and MET is that both compounds induce an exocytotic process in excitable cells mainly through two postulated mechanisms: (i) an intravesicular alkalinization (Seglen, 1983; Mundorf et al., 1999) or (ii) a blocking property of different type of potassium currents in the cells (Szerb & Butterworth, 1992; Moroni et al., 1998; Hrnjez et al., 1999). Consistent with both of these, neurotransmitter release and consequently some behavioural and neurological functions including arousal, learning, pain perception and motor activity could be modified in hyperammonaemic situations (Kuta et al., 1983; Szerb & Butterworth, 1992; Aguilar, 2000).

Neurobehavioural investigations have recently shown that different voltage-dependent potassium channel blockers, including NH3, MET and tetraethylammonium (TEA), reduce the food intake in starved mice by acting as depolarizing compounds in the brain (Ghelardini et al., 1997; Banchelli et al., 2001; Pirisino et al., 2001; Ghelardini et al., 2003). In some experiments, an antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide (aODN) targeting the translation start region of the Shaker-like Kv1.1 gene (aODN1) abolished the anorectic effect of TEA, suggesting that functionally active Kv1.1 channel subtypes in the brain are required for the activity of this compound. However, the observation that the hypophagic effect of NH3 and MET was unaffected by this aODN indicated a possible involvement of channel subtypes different from Kv1.1 for the hypophagic effect of these latter compounds (Pirisino et al., 2001).

Starting from this hypothesis, because of the aforementioned physiopathological relevance of NH3 and MET, the present work was undertaken in order to investigate the possibility that these amines perform their hypophagic effect through an interaction with voltage-activated potassium channels different from Kv1.1 subtype. An antisense strategy capable of temporarily knocking down the expression of all seven known subtypes of Shaker-like genes was used to achieve this aim.

Methods

Animals

Male Swiss albino mice (24–26 g) from Morini (San Polo d'Enza, Italy) were used. In all, 15 mice or five rats were housed per cage. The cages were placed in the experimental room 24 h before the test for acclimatization purposes. The animals were fed a standard laboratory diet and tap water ad libitum; they were kept at 23±1 °C, with a 12 h light/dark cycle, and light at 0700. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Community Council's Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) relative to experimental animal care. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used.

Evaluation of food consumption

The mice did not have access to food for 12 h, but water was available ad libitum. A weighed amount of food (standard laboratory pellets) was given, and the amount consumed (evaluated as the difference between the original amount and the food left in the cage, including spillage) was measured after 15, 30, 45 and 60 min, in order to evaluate the time course of each treatment, after the intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of saline or drug solutions, with an accuracy of 0.1 g. An arbitrary cutoff time of 60 min was adopted, and the total amount of food consumed was expressed in mg mouse h−1. A constant decrease in the food intake was observed at every interval, which indicated that the hypophagic effect of the treatments did not disappear within 60 min. The cutoff time used in our experiments (60 min) corresponded to the maximum food intake observable in control animals: after 60 min, the amount of food intake drastically decreased in the control group. The food intake was measured in animals housed individually, for acclimatization, in the cage 12 h before inducing the food deprivation. The experiment was then performed in the same cage.

Drug administration by i.c.v. route

The i.c.v. administration took place under ether anaesthesia with isotonic saline used as solvent, according to the method described by Haley & McCormick (1957) without the assistance of a stereotaxic apparatus. During anaesthesia, the mice were grasped firmly by the loose skin behind the head. The effects produced by ether anaesthesia and by i.c.v. injection were determined in different groups of mice: naive animals, animals that received anaesthesia without receiving an i.c.v. injection and animals that received an i.c.v. injection of saline. No difference in the food intake among groups was observed. A hypodermic needle (0.4 mm external diameter) attached to a 10 μl syringe was inserted perpendicularly through the skull and no more than 2 mm into the brain of the mouse, where a 5 μl solution was then administered. The injection site was 1 mm to the right or left of the midpoint on a line drawn through to the anterior base of the ears. Injections were performed into the right or left ventricle. To ascertain that solutions were administered exactly into the cerebral ventricle, some mice were injected with 5 μl of diluted 1 : 10 India ink and their brains were examined macroscopically after sectioning. The accuracy of the injection technique was evaluated, with 95% of the injections being correct. Owing to this high percentage of correct injections, no animal was excluded.

Before i.c.v. administration of the compounds used, it was assessed that the pH values of the nM compound solutions, ranging from 7.2 to 6.7, did not vary significantly from those of the saline (pH=6.8±0.4).

Design of aODNs

An anti-mouse aODN against all the Kcna isoforms, named anti-Kv1–7 aODN (aODN1−7), was designed comparing the sequences of the known mouse Kcna coding genes (Kcna1, Kcna2, Kcna3, Kcna4, Kcna5, Kcna6 and Kcna7) and choosing a common and conserved region with a 92% homology. The sequence of the aODN1−7 was: 5′-TGG CGG GAG AGC TTG AAG AT-3′. In order to knockdown single Kcna isoforms, we designed seven specific anti-mouse Kcna aODNs (aODN1, aODN2, aODN3, aODN4, aODN5, aODN6 and aODN7), the sequences of which are shown in Table 1. Moreover, in consideration of the described sequence-independent, nonantisense effects of ODNs described, we designed one type of control: a 20-mer fully degenerated ODN (dODN), 5′-NNN NNN NNN NNN NNN NNN NN-3′ (where N is G, or C, or A, or T). The aODN and the control dODN were phosphorothioate protected by a 5′- and 3′-end double substitution (phosphorothioate residues are emphasized), synthesized on a 10-μmol scale and purified by HPLC. ODNs were vehiculated intracellular by cationic lipid DOTAP (13 μM) Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) to enhance both uptake and stability (Whitesell et al., 1993).

Table 1.

Anti-Kcna1, Kcna2, Kcna3, Kcna4, Kcna5, Kcna6 and Kcna7 ODN sequences

| aODNs | aODNs sequences | GenBank Accession Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| aODN1–7 | TGG CGG GAG AGC TTG AAG AT | |

| aODN1 | GCATTCTCCCCCGACATCAC | NM_010595 |

| aODN2 | ACTGGGTCTCCGGTAGCCAC | NM_008417 |

| aODN3 | CGCCGCCACTGCCAC | NM_008418 |

| aODN4 | GTACGAACACCCATCCCCAT | NM_021275 |

| aODN5 | CTCCTCATCCTCAGCA | AF302768 |

| aODN6 | CCCGGCGCCGCCAGCGTCAG | NM_013568 |

| aODN7 | GCAGCCACCCCAGTCGGGTG | AF032099 |

Semiquantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT—PCR)

For the quantification of Kv1.6. mRNA levels, total RNA was extracted by Tri Reagent Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Semiquantitative determination of Kv1.6 mRNA levels was carried out by an internal standard-based RT–PCR assay with serial dilution of total RNA and using β-actin as reference gene, as described previously (Pacini et al., 1999). Total RNA (200 ng) were reverse transcribed and amplified by the SuperScript One-Step RT–PCR System (Invitrogen, Europe). A 219 bp segment of the murine Kv1.6 cDNA sequence was targeted with upstream primer 5′-GGC TTC CTT CTC ATG CTC AC-3′, bases 2559–2578 and downstream primer 5′-GTG ACT GAT GGG CAT GAT TG-3′, bases 2759–2778, while a 326 bp segment of the murine β-actin sequence (GenBank™ Accession Number NM_007393) was amplified with upstream primer 5′-GCG GGA AAT CGT GCG TGA CAT T-3′, bases 2106–2127, and downstream primer 5′-GAT GGA GTT GAA GGT AGT TTC GTG-3′, bases 2409–2432. The RT–PCR profile was: one cycle of 55°C for 30 min and 94°C for 2 min (cDNA synthesis and predenaturation) followed by PCR amplification performing 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min. Amplification products were run on a 2% agarose gel and the ethidium bromide-stained bands were quantified by densitometric analysis. Within the linear range of amplification, at least three values of Kv1.6 amplification products were normalized to the starting total RNA volumes and referred to the corresponding β-actin values.

Western blotting

Mouse brains (∼0.2 g) of control (dODN6) and antisense-treated (aODN6) mice were homogenized on ice in 1 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and 0.1 mg ml−1 protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche, Milan, Italy). Homogenates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting supernatants underwent determination of protein concentration by the bicinchoninic acid reagent Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Lysates containing 30 μg of proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Western blot analyses were performed using anti-Kv1.6 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Europe), followed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) at a dilution of 1 : 2000. The blots were developed using Opti-4CN kit (BioRad, Europe).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunochemical experiments, control mice (dODN6) were overdosed with 5% chloral hydrate by means of intraperitoneal administration and were perfused transcardially with 50 ml of cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.02 M, pH 7.4), followed by 100 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed immediately and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h; they were cryoprotected in a series of cold sucrose solutions of increasing concentration. Frozen brains were cut at 8 μm in the coronal plane and were incubated in a 1 : 200 dilution of primary antibody (anti-Kv1.6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Europe) overnight at 4°C, followed by a 30 min wash in PBS. The sections were then immersed for 1 h in the peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G diluted at 1 : 500 in PBS. Next, the sections were rinsed for 30 min in PBS, followed by a 15-min incubation in NovaRED substrate (VECTOR NovaRED substrate kit, Vector, Peterborough, U.K.). Sections were counterstained with toluidine blue and then mounted on slides. Control sections were treated as described above, but omitting the primary antibody.

Reagents and drugs

Ammonium acetate, MET HCl and TEA chloride used in the food intake experiments were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (Milan, Italy). The compounds were dissolved in isotonic (NaCl 0.9 %) saline. Drug concentrations were prepared in such a way that the necessary dose could be administered by i.c.v. injection in a volume of 5 μl mouse−1. The ODNs used for the antisense strategy were from Genosys (The Woodlands, U.S.A.). DOTAP was from Boheringer-Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). Antisense and degenerated ODNs were dissolved in the vector (DOTAP) at least 30 min before injection.

Statistical analysis

All experimental results are given as the mean±s.e.m. An analysis of variance was used to verify the significance between two means of the behavioural results, and was followed by Fisher's protected least significant difference procedure for post hoc comparison. Data were analysed using the Stat View software for Macintosh (1992). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Food intake experiments

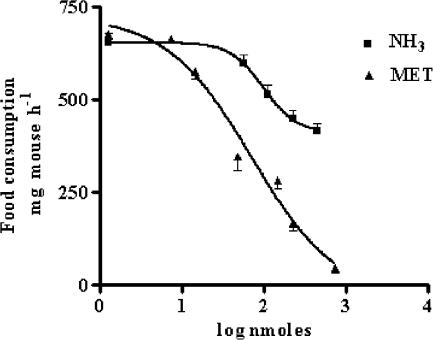

Figure 1 shows a comparison from dose–response experiments for the hypophagic effect of i.c.v.-injected MET and NH3 in 12-h starved mice. Expressed as the dose of compound required to produce a 50% reduction of feeding, an ED50 value (71.4±1.8 nmol mouse−1) was calculated only for MET, since highest reduction induced by NH3 was about 30% of the total food consumption in control mice.

Figure 1.

Dose-related reduction of food intake in 12 h starved mice after the i.c.v. injection of MET or NH3, as measured 60 min after food readministration. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of at least 10 mice.

Effect of aODN1 and aODN1−7 pretreatments

In Table 2, the hypophagic effects of equivalent doses (about three times higher than MET ED50; 226 nmol) of MET and NH3, injected i.c.v. in 20 nmol aODN1−7-pretreated mice, are reported. As detailed in the Methods section, this aODN was specifically designed to abolish contemporaneously the expression of all seven known subtypes of Shaker-like Kv1 channels. In Table 2, the effect induced by repeated administration of this aODN on the hypophagic effect of NH3, MET and TEA is also compared with the effect elicited by 3 nmol aODN1 pretreatment. A dose of 20 nmol of aODN1−7 was selected for these experiments on the basis of preliminary results, which showed that this quantity reduced the hypophagic response of 30 nmol i.c.v. TEA (taken as a reference compound) of an amount similar to the one previously observed when pretreatments with 3 nmol of aODN1 were used (Pirisino et al., 2001). Moreover, the administration schedule of aODN1−7 (a single i.c.v. injection on days 1, 4 and 7 before the administration of compounds) was the same as the one previously used in experiments with aODN1 (Galeotti et al., 1997a, 1997b; Ghelardini et al., 1997). In these, by means of quantitative RT–PCR analysis, it was observed that this treatment significantly reduced (by more than 60%) the expression of the Kv1.1 channel subtype in the mouse brain.

Table 2.

Reduction of the hypophagic effect of NH3-, MET- and TEA in ODNs-pretreated 12 h fasted mice

| Compound, 226 nmol/5 μl i.c.v. | Food consumption (mg mouse h−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dODN1 | %a | aODN1 | %a | dODN1−7 | %a | aODN1−7 | %a | |

| Saline | 653±26 | — | 697±20 | — | 623±12 | — | 604±11 | — |

| NH3 | 449±23 | 23 | 429±25 | 38 | 414±23 | 33 | 451±18 | 25 |

| MET | 154±21 | 76 | 131±27 | 81 | 211±10 | 66 | b487±18 | 19 |

| cTEA | 381±16 | 49 | b674±25 | 3 | 313±70 | 50 | b583±17 | 3 |

All tested compounds significantly reduced the food intake (P< 0.01) in dODNs-treated animals compared with control mice (saline injected). In all, 3 nmol of a/dODN1 and 20 nmol of a/dODN1–7 were injected i.c.v. in 5 μl of DOTAP solution.

Percentage reduction vs saline, ODNs-pretreated controls. Each value represents the mean±s.e. mean of at least 10 animals.

Significant (P<0.01) in comparison with the anorectic effect of the compound in dODNs-pretreated animals.

cTEA+ 30 nmol i.c.v.

As shown in Table 2, the hypophagic effect of both MET or NH3 was unaffected by pretreatments with aODN1. However, in mice pretreated with 20 nmol of the aODN1−7, a significant inhibition was observed only for the hypophagic effect of MET, despite the fact that the recovery of the food consumption was incomplete when compared with the food intake observed in controls, saline-injected, dODN1−7-pretreated mice. In contrast, the hypophagic responses of TEA were almost completely reversed in mice pretreated with both aODN1 or aODN1−7.

The ability of aODN1−7 in counteracting the hypophagic effect of MET was also evaluated by increasing the dosage of this aODN. In Figure 2, a progressive reduction of the MET effect is shown with maximum effect between 20 and 40 nmol of aODN1−7. In the experiments reported in Table 2, as well as in Figure 2, the degenerated ODN (dODN1 or dODN1−7) were both unable to modify significantly the food consumption of saline-injected animals.

Figure 2.

Effect of increasing concentrations (i.c.v. injection at days 1, 4 and 7) of aODN1−7 or dODN1−7 on MET-induced food consumption in 12 h starved mice, as measured 60 min after food readministration. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of at least 10 mice. *P<0.01 in comparison with dODN1−7-pretreated mice.

The motor coordination in mice after different pharmacological treatments was also evaluated by the Hole-board test, as described previously (Ghelardini et al., 2003), starting 15 min after the i.c.v. injection of the test compounds or 48 h after the last ODN injection. As all the compounds, at the highest active doses employed in the present study, did not cause any detectable modification in mouse gross behaviour (motor coordination, spontaneous motility or inspection activity) in comparison with control groups (data not shown), excluding that the results obtained were due to an altered viability of animals, such experiments are not reported for brevity in the text.

Effect of aODNs relative to each single Kv1 subtype on MET activity

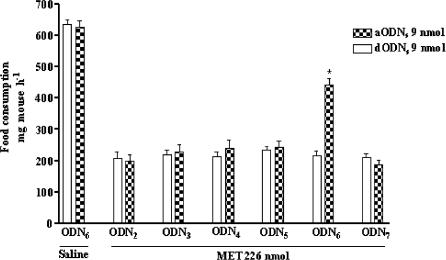

The results obtained in mice pretreated with aODN1 or aODN1−7 indicated that one or more subtypes of Shaker-like channels ranging from Kv1.2 and Kv1.7 were probably the molecular targets for the hypophagic activity of MET. To confirm this hypothesis, the effect of MET was evaluated in mice pretreated with aODNs specifically designed to block the expression of each single Shaker-like channel subtype in the mouse brain (see Table 1 for reference). As a result (Figure 3), a significant inhibition of the hypophagic effect of MET was obtained only in mice receiving the aODN towards Kv1.6 subtype, in accordance with the general scheme of aODN administration reported in Methods section. In Figure 3, the absence of any interference on food intake in control, starved mice pretreated with 9 nmol of aODN6 or dODN6 strongly supported the view that these ODNs where devoid ‘per se' of any type of central activity at the dosage employed. Similar results were obtained in control mice pretreated with ODNs specific for the other channel subtypes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of aODN2, aODN3, aODN4, aODN5, aODN6, aODN7 and related dODNs (controls) (9 nmol per single i.c.v. injection at days 1, 4 and 7) on MET-induced food consumption in 12 h fasted mice, as measured 60 min after food readministration. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of at least 10 mice. *P<0.01 in comparison with dODN6-pretreated mice.

A pretreatment with 9 nmol of aODN6 was used in these experiments, because this was preliminarily assessed as the smaller dose of aODN6 almost equipotent to 20 nmol of aODN1−7 in reducing the MET-induced hypophagic response in mice.

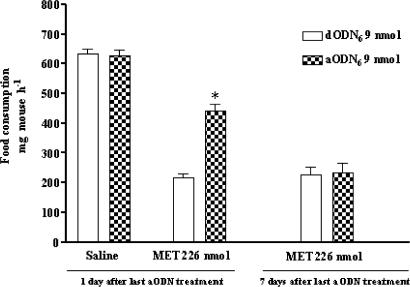

Time dependence of the aODN6 on MET effects

The aODN6 pretreatment (9 nmol i.c.v. per mouse) prevented the hypophagic response of MET, and this effect was detected 24 h after the end of the aODN6 pretreatment. In contrast, 7 days after the last aODN6 injection, the effect of the aODN6 disappeared and the same animals were once again sensitive to the anorectic effect of MET (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Recovery of the hypophagic response of i.c.v.-administered MET (226 nmol) in aODN6- or dODN6- (controls) (9 nmol per single i.c.v. injection at days 1, 4 and 7) pretreated mice. At 7 days after the last aODN injection, the inhibitory effect of the aODN6 was completely lost. *P<0.01 in comparison with dODN6-pretreated mice taken as controls. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of at least 10 mice.

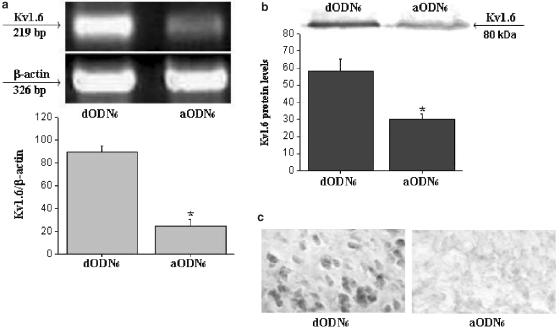

Effect of aODN6 on mKvl.6 gene expression

The lowering of Kv1.6 mRNA after aODN administration, as an index of Kv1.6 gene expression inactivation, was quantified by RT–PCR. Before quantification, RT products were preliminarily tested for possible genomic DNA contamination. For this purpose, segments of 200 bp for mouse Kv1.6 cDNA and of 326 bp for β-actin cDNA, visualized by agarose-gel electrophoresis (Figure 5a), showed bands of an expected length and the absence (data not shown) of any contamination in the negative controls. Quantitative results of Kv1.6 and β-actin mRNA brain levels after aODN6 (9 nmol mouse−1 i.c.v.) pretreatment confirmed that, in starved mice, the MET-induced hypophagic effect were actually related by the specific inhibition of Kv1.6 gene expression. These results show that the ratio of Kv1.6 mRNA over β-actin mRNA was sharply lowered (about 70% reduction) in aODN6-treated mice, as compared with dODN6-treated ones. The decrease in specific mRNA was in good correlation with a significant reduction (about 50% reduction) of the phenotypic expression of the 80 kDa Kv1.6 protein level (Figure 5b) in brain homogenates obtained from aODN-treated mice as well as with the reduction of hypophagic response of MET (Figures 3 and 4). Some experiments were also conducted on brain tissues of mice pretreated with aODNs designed to be selective for every other Shaker-like channel subtype. These aODNs induced a lowering in specific mRNA levels to an extent similar to that observed in aODN6-treated mice. However, because these aODNs were without any effect in reducing the hypophagic response of MET, no further investigation was made of their properties.

Figure 5.

(a) Lowering of Kv1.6 over β-actin mRNA levels in brain homogenates as detected by RT–PCR. (b) Reduction of phenotypic expression of the 80 kDa Kv1.6 protein level in brain homogenates obtained from aODN6-treated mice. (c) Left panel, Kv1.6 immunoreactivity in the LAH of hypothalamic neurons of dODN6- (controls) pretreated mice; evidence for a significant reduction of immunostaining in brain sections from aODN6-pretreated mice (right panel).

Effect of aODN6 on hypothalamic Kv1.6 protein expression

To evaluate whether the reduction of Kv1.6 protein observed in whole brain mouse homogenates corresponded to a similar reduction in specific brain areas of aODN6-treated mice, we performed some preliminary, immunohistochemical, experiments on brain sections of the same mice used to assess food consumption. In dODN6-pretreated mice, we localized a high expression of Kv1.6 in different brain areas of the mouse. Hypothalamic neurons, for example, showed strong Kv1.6 immunoreactivity in the lateroanterior hypothalamic nucleus (LAH), with a relatively marked staining in the plasmatic membrane of cell bodies (Figure 5c, left panel). Kv1.6 immunoreactivity was not observed in sections obtained from aODN6-pretreated animals (Figure 5c, right panel).

Discussion

MET and NH3, two known endogenous weak bases, when injected i.c.v., dose-dependently reduced food intake in mice. An analysis of the sigmoid curves obtained with these two compounds indicate that MET is more active than NH3 for this effect. These results agree with previous observations (Pirisino et al., 2001), which showed that single doses of these compounds were differently potent in eliciting hypophagic effects when injected i.c.v. in mice starved for 12 h. Moreover, if we look at the slope of the dose–response curves and consider the maximum effects elicited, it is reasonable to conclude that these two amines work with a probably different mechanism of action.

NH3 and MET, and other basic compounds, are considered of importance in hepatic or renal insufficiency and in central neurodegenerative disease including Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. However, despite the fact that endogenous levels of MET are often increased in those pathological conditions in which NH3 brain elevations are also seen (Yu et al., 2003), minor attention has been paid up, until now, to the specific mechanism of action of this amine, which is often considered, due to its chemicophysical properties, to be similar to that of NH3.

Alteration of axonal conductance (Raabe, 1989), ionic pumps inhibition (Lux & Neher, 1970) and modification of central 5-HT or dopamine turnover has been described for NH3 (Szerb & Butterworth, 1992). Such changes are considered to be responsible for alterations to several behavioural functions in experimental animals and ureamic patients (Kuta et al., 1983; Szerb & Butterworth, 1992). GABAergic or glutammatergic transmission is also modified in hyperammonaemic status so that, depending on the brain levels, both neuroexcitation and seizures or lethargy, confusion, global CNS depression and coma could develop (Basile, 2002; Zielinska et al., 2002). For MET, only indirect evidence are obtained in mice pretreated with MAO A or MAO B inhibitors, which indicates that this compound acts as a central anorexigenic without any apparent interference from the release of monoaminergic mediators (Pirisino et al., 2001).

NH3 and MET are both recognized as acting as exocytotic agents in excitable cells. It has been considered that, because of their liposolubility, these compounds quickly pass in unprotonated form through the plasmatic membrane of the neurons, disrupting – by an elevation of the intragranular pH – the association of neurotransmitters with Ca2+, ATP and vesicular proteins (Seglen, 1983; Mundorf et al., 1999). On the other hand, the pKa values of NH3 and MET (9.2 and 10.6, respectively) indicate that, under physiological pH, 98–99% of these amines are protonated so that, in this form, they may also enter the cells through ionic channels. It has been shown that, among a series of amines of increasing molecular weight, the protonated form of NH3 and MET have the highest probability of occupying the channel site for K+, reducing the conductance of this ion with depolarizing effects. This is in accordance with other results which show that NH3 and MET, in their protonated form, are able to block different types of potassium currents in the cells (Szerb & Butterworth, 1992; Moroni et al., 1998; Hrnjez et al., 1999).

Potassium channels represent the largest family of the ion channels having an important role in cellular excitability, regulating neurotransmitter release and other cellular functions. Membrane depolarization open voltage-gated potassium channels conducting outward currents, which in turn leads to repolarization of the membrane. A subfamily of the voltage-operated potassium channels, widely distributed in brain tissue, is related to Shaker-like genes encoding for seven members (Kv1.1–Kv1.7) of these channels (Kashuba et al., 2001; Chung et al., 2001).

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the possibility that the hypophagic effects of NH3 and MET might be due to an interaction of a Shaker-like channel subtypes different from Kv1.1. The present investigations confirm some previously reported results (Pirisino et al., 2001), showing that neither NH3- nor MET-induced hypophagic effects are influenced by aODN anti-Kv1.1 channels. When the animals were pretreated with aODN1−7, a different pattern of activity resulted. The inhibition of the hypophagic effect of TEA, which was assessed as being sensitive to aODN1, was still observed. However, a significant reversal of the MET-induced effects was seen, suggesting that aODN1−7 have reduced the expression of Shaker-like channel subtypes different from Kv1.1 ones that probably represent an important molecular target of MET.

Dose–response experiments indicate that aODN1−7 maximally inhibited the MET-induced hypophagic effects at concentrations seven times higher than those required by aODN1 for its effects (20 vs 3 nmol, respectively). As reported in the Methods section, the aODN1−7 was designed to inactivate contemporaneously the expression of seven different channel subtypes by choosing a common and conserved mRNA region with a 92% homology. By widening the pattern of activity, this procedure could have reduced the specificity of aODN1−7 for an individual channel subtype, leading to an increase in the concentrations required to inhibit a single channel expression. On the other hand, pretreatments with aODN1−7 were still ineffective in reducing the hypophagic effect of NH3 in starved mice, further confirming that MET and NH3 act as hypophagic compounds but with a completely different action mechanism. These observations may provide an explanation for the partial hypophagic response of NH3 as compared to the total abolition of this response induced by MET. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the release of neuromediators with different hypophagic potency could be differently modulated by NH3 or MET, as a consequence of the interaction with their respective molecular targets.

To clarify which subtype of the Shaker-like potassium channels was responsible for the hypophagic effect of MET, this compound was administered to mice pretreated with aODNs designed to block the expression of single channel subtypes. Results indicate that the hypophagic effect of MET was significantly reduced only in mice pretreated with the anti-Kv1.6 aODN (aODN6). The reduction in mRNA levels, together with a significant inhibition of specific Kv1.6 protein in brain homogenates of mice used for food intake experiments, confirm that, differently to NH3, MET require the full expression of Kv1.6 channel subtype in the membrane for its activity. Interestingly, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical analysis, the aODN6 particularly downregulated Kv1.6 the expression in the LAH. As lateral hypothalamus displays high receptor density for different monoaminergic as well as nonmonoaminergic endogenous neuromediators known to participate centrally in the regulation of the food intake (Inui, 2000), it is possible to hypothesize that MET could act as hypophagic mainly in this brain area.

Considering the apparent difference in the action mechanism of NH3 and MET, it is possible that NH3, because of its low molecular size and high liposolubility, freely accumulate into neurons by passive diffusion as well as through ionic channels. The intragranular alkalinization and/or an unselective potassium channel blocking activity should be equally involved in the central effect of this amine. On the contrary, the ammonium analogue MET, at least at the doses employed in this work, could be regarded as a selective blocker of neuronal Shaker-like Kv1.6 channel subtype able to modulate, in such way, the release of some hypophagic neuromediators. This view seems to be in some agreement with the electrophysiological results of Moroni et al. (1998) and of Hrnjez et al. (1999), which show that NH3, MET and other alkyl amines compete with different selectivity for potassium currents in different cellular experimental models.

Conclusions

To conclude, we have demonstrated for the first time that MET, an endogenous basic compound of physiopathological interest, differently to NH3, induces its central hypophagic effects by acting on Kv1.6. potassium channels subtypes. These observations may provide more insight into the role of this weak base in pathological conditions in which an increase in the plasma and brain levels of this amine is found.

Acknowledgments

The financial support for this research was obtained from 2001 Italian Grant of MIUR.

Abbreviations

- aODNs

antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- MET

methylamine

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

References

- AGUILAR M.A. Chronic moderate hyperammoniemia impairs active and passive avoidance behavior and conditional discrimination learning in rats. Exp. Neurol. 2000;161:704–713. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABA S., WATANABE Y., GEJYO F., ARAKWA M. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of serum aliphatic amines in chronic renal failure. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1984;136:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(84)90246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANCHELLI G., GHELARDINI C., RAIMONDI L., GALEOTTI N., PIRISINO R. Selective inhibition of amine oxidases differently potentiate the hypophagic effect of benzylamine in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;413:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASILE A.S. Direct and indirect enhancement of GABAergic neurotransmission by ammonia: implications for the pathogenesis of hyperammonemic syndromes. Neurochem. Int. 2002;41:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUFFONI F. Semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidases: some biochemical properties and general considerations. Prog. Brain Res. 1995;106:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTTERWORTH R.F. Complications of cirrhosis III. Hepatic encephalopathy. J. Hepatol. 2000;32:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG Y.H., CHUNG-MIN S., KIM M.J., LEE B.K., CHA C.I. Istochemical study on the distribution of six members of the Kv1 channel subunits in the rat cerebellum. Brain Res. 2001;895:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOPER A.J.L., PLUM F. Biochemistry and physiology of brain ammonia. Physiol. Rev. 1987;67:440–519. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAR M.S., MORSELLI P.L., BOWMAN E.R. The enzymatic system involved in the mammalian metabolism of methylamine. Gen. Pharmacol. 1985;16:615–620. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALEOTTI N., GHELARDINI C., CAPACCIOLI S., QUATTRONE A., NICOLIN A., BARTOLINI A. Blockade of clomipramine and amitriptyline analgesia by an antisense oligonucleotide to mKv1.1, a mouse Shaker-like K+ channel. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;330:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)10134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALEOTTI N., GHELARDINI C., PAPUCCI L., CAPACCIOLI S., QUATTRONE A., BARTOLINI A. An antisense oligonucleotide on the mouse Shaker-like potassium channel Kv1.1 gene prevents antinociception induced by morphine and baclofen. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997b;281:941––949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHELARDINI C., GALEOTTI N., PECORI V.A., CAPACCIOLI S., QUATTRONE A., BARTOLINI A. Effect of K+ channel modulation on mouse feeding behaviour. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;329:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)10102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHELARDINI C., QUATTRONE A., GALEOTTI N., LIVI S., BANCHELLI G., RAIMONDI L., PIRISINO R. Antisense knockdown of the Shaker-like Kv1.1 gene abolishes the central stimulatory effects of amphetamines in mice and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1096–1105. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALEY T.J., MCCORMICK W.G. Pharmacological effects produced by intracerebral injection of drugs in the conscious mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1957;12:12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1957.tb01354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HRNJEZ B.J., SONG J.C., PRASAD M., MAYOL J.M., MATTHEWS J.B. Ammonia blockade of intestinal epithelial K+ conductance. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G521–G532. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.3.G521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INUI A. Transgenic approach to the study of body weight regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASHUBA V.I., KVASHA S.M., PROTOPOPOV A.I., GIZATULLIN R.Z., RYNDITCHE A.V., WAHLESTEDT C., WASSERMAN W.W., ZABAROVSKY E.R. Initial isolation and analysis of the human Kvl.7 (KCNA7) gene, a member of the voltage-gated potassium channel gene family. Gene. 2001;268:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUTA C.C., MAICKEL R.P., BOROWITZ J.L. Modification of drug action by hyperamoniemia. J. Pharmacol. Expt. Ther. 1983;229:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUX H.D., NEHER E. The action of ammonium on post-synaptic inhibition of cat spinal motorneurones. Exp. Brain Res. 1970;11:431–447. doi: 10.1007/BF00233967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORONI A., BARDELLA L., THIEL G. The impermeantion methylammonium blocks K+ and NH4+ currents thorough KAT1 channel differently: evidence for ion interaction in channel permeation. J. Membr. Biol. 1998;163:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s002329900367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNDORF M.L., HOCHSTETLER S.E., WIGHTMAN R.M. Amine weak bases disrupt vesicular storage and promote exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:2397–2405. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLDE DAMINK S.W.M., DEUTZ N.E.P., DEJONG C.H.C., SOETERS P.B., JALAN R. Interorgan ammonia metabolism in liver failure. Neurochem. Int. 2002;41:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PACINI A., QUATTRONE A., DENEGRI M., FIORILLO C., NEDIANI C., RAMON Y., CAJAL S., NASSI P. Transcriptional downregulation of PARP gene expression by E1A binding to pRb proteins protects murine keratinocyted from radiation-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35107–35112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIRISINO R., GHELARDINI C., BANCHELLI G., GALEOTTI N., RAIMONDI L. Methylamine and benzylamine induced hypophagia in mice: Modulation by semicarbazide-sensitive benzylamine oxidase inhibitors and aODN towards Kv1.1 channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:880–886. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRECIOUS E., GUNN C.E., LYLES G.A. Deamination of methylamine by semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase in human umbilical artery and rat aorta. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1988;37:707–713. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAABE W.Neurophysiology of ammonia intoxication Hepatic Encephalopathy: Pathophysiology and Treatment 1989Clifton, NJ: Humana Press; 49–77.ed. Butterworth, R. & Pomier-Layrargues, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- RAABE W.Effects of hyperammoniemia on neuronal function: NH4+, IPSP and Cl− extrusion Cirrhosis, Hyperammoniemia and Hepatic Encephalopaty 1994New York: Plenum Press; 71–82.ed. Grisolia, F. & Felipo, V. pp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGLEN P.O. Inhibitors of lysosomal function. Methods Enzymol. 1983;96:737–764. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)96063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEILER N. Ammonia and Alzaimer's disease. Neurochem. Int. 2002;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZERB C.J., BUTTERWORTH R.F. Effects of ammonium ions on synaptic transmission in the central nervous system. Progr. Neurobiol. 1992;39:135–152. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMENHOFF M.L. Metabolism and toxicity of aliphatic amines. Kidney Int. 1975;7:S314–S317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITESELL L., GESELOWITZ D., CHAVANY C., FAHMY B., WALBRIDGE S., ALGER J.R., NECKERS L.M. Stability, clearance, and disposition of intraventricularly administered oligodeoxynucleotides: implications for therapeutic application within the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:4665–4669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU P.H., DYCK R.F. Impairment of methylamine clearance in uremic patients and its nephropathological implications. Clin. Nephrol. 1998;49:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU P.H., WRIGHT S., FAN E.H., LUN Z.R., GUBISNE-HARBERLE D. Physiological and pathological implications of semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1647:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEISEL S.H., DA COSTA K.A. Increase in human exposure to methylamine precursors of N-nitrosamines after eating fish. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6136–6138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIELINSKA M., HILGIER W., LAW R.O., GORYNSKI P., ALBRECHT J. Effects of ammonia and hepatic failure on the net efflux of endogenous glutamate, aspartate and taurine from rat cerebrocortical slices: modulation by elevated K+ concentrations. Neurochem. Int. 2002;41:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]