Abstract

Rosiglitazone is an agonist of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) and ameliorates insulin resistance in type II diabetes. In addition, it may also promote increased pancreatic β-cell viability, although it is not known whether this effect is mediated by a direct action on the β cell. We have investigated this possibility.

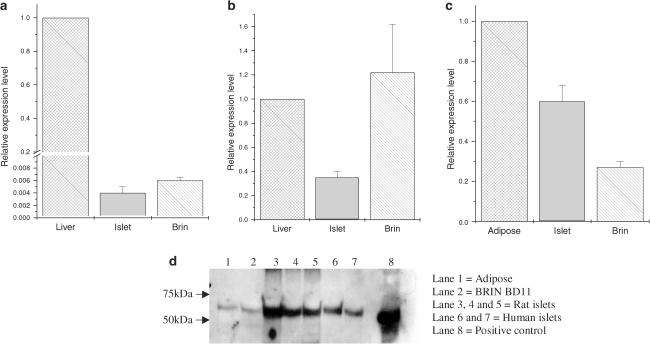

Semiquantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis (Taqman®) revealed that freshly isolated rat islets and the clonal β-cell line, BRIN-BD11, express PPARγ, as well as PPARα and PPARδ. The levels of expression of PPARγ were estimated by reference to adipose tissue and were found to represent approximately 60% (islets) and 30% (BRIN-BD11) of that found in freshly isolated visceral adipose tissue. Western blotting confirmed the presence of immunoreactive PPARγ in rat (and human) islets and in BRIN-BD11 cells.

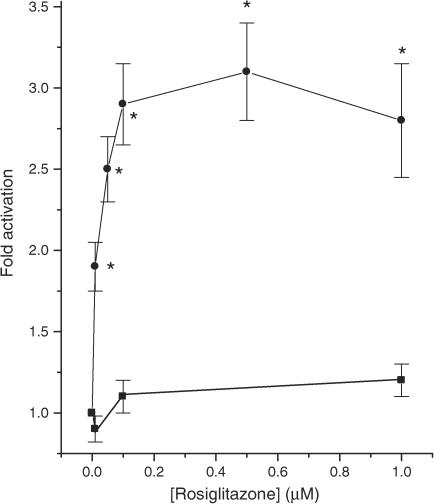

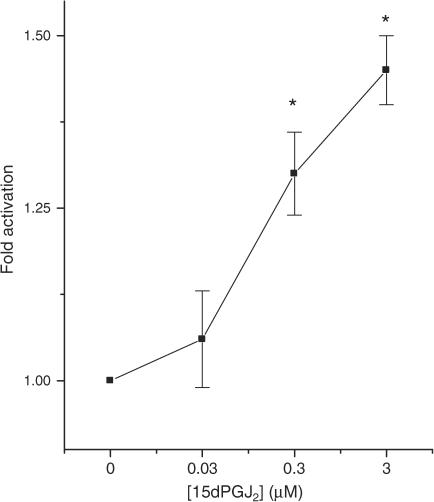

Transfection of BRIN-BD11 cells with a PPARγ-sensitive luciferase reporter construct was used to evaluate the functional competence of the endogenous PPARγ. Luciferase activity was modestly increased by the putative endogenous ligand, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2). Rosiglitazone also caused activation of the luciferase reporter construct but this effect required concentrations of the drug (50–100 μM) that are beyond the expected therapeutic range. This suggests that PPARγ is relatively insensitive to activation by rosiglitazone in BRIN-BD11 cells.

Exposure of BRIN-BD11 cells to the lipotoxic effector, palmitate, caused a marked loss of viability. This was attenuated by treatment of the cells with either actinomycin D or cycloheximide suggesting that a pathway of programmed cell death was involved. Rosiglitazone failed to protect BRIN-BD11 cells from the toxic actions of palmitate at concentrations up to 50 μM. Similar results were obtained with a range of other PPARγ agonists.

Taken together, the present data suggest that, at least under in vitro conditions, thiazolidinediones do not exert direct protective effects against fatty acid-mediated cytotoxicity in pancreatic β cells.

Keywords: Rosiglitazone; pioglitazone; 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2; lipotoxicity; islets of Langerhans; BRIN-BD11 cell; Taqman

Introduction

Two thiazolidinediones (TZDs), rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, have recently come into clinical use as insulin sensitizers and these are effective in the management of type II diabetes (Camp, 2003; Diamant & Heine, 2003; Stumvoll, 2003). Their insulin-sensitising actions at the whole organism level are likely to involve complex mechanisms but the principal molecular target is a nuclear transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) (Olefsky, 2000; Furnsinn & Waldhausl, 2002; Camp, 2003; Tadayyon & Smith, 2003). This receptor is expressed in a range of tissues but is most abundant in adipocytes. Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone act as agonists of PPARγ and, accordingly, they promote increased adipogenesis and a reduction in plasma-free fatty acids (Camp, 2003; Diamant & Heine, 2003; Stumvoll, 2003; Tadayyon & Smith, 2003). These actions probably underlie the decrease in insulin resistance although it is also possible that TZDs may exert effects in other insulin-sensitive tissues, such as skeletal muscle and liver.

In addition to their effects on peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues, recent evidence has been taken to suggest that TZDs may also act at the level of the endocrine pancreas. This conclusion has arisen from data indicating that the progressive decline in β-cell function and viability that normally accompanies type II diabetes are attenuated during administration of TZDs (Buckingham et al., 1998; Ishida et al., 1998; Shimabukuro et al., 1998; Jia et al., 2000; Finegood et al., 2001). These effects were first observed in animal models of type II diabetes but are also seen in man (Cavaghan et al., 1997; Prigeon et al., 1998; Buchanan et al., 2002; Ovalle & Bell, 2002) where they could contribute to the improvement in glucose homeostasis during TZD administration.

Thus, it is possible that the pancreatic β cell may be a target for the actions of TZDs and, in support of this, PPARγ expression has been detected in islet cells (Braissant et al., 1996; Dubois et al., 2000; Patane et al., 2002) and in clonal β-cell lines (Zhou et al., 1998; Roduit et al., 2000; Kawai et al., 2002). However, there are conflicting data on the expression of PPARγ in these cells (Flamez et al., 2002; Nakamichi et al., 2003) and it remains controversial whether PPARγ agonists can directly influence β-cell function. For example, Masuda et al. (1995) and Ohtani et al. (1998) reported that the TZD, troglitazone, increased the rate of insulin secretion from isolated islets and HIT-T15 cells and Shimabukuro et al. (1998) observed a reduction in triacylglycerol content of islets from Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats during culture with troglitazone. In addition, Kawai et al. (2002) suggested that troglitazone can ameliorate the lipotoxic effects of fatty acids in cultured β cells. By contrast, Cnop et al. (2002) observed that troglitazone fails to counteract β-cell lipotoxicity and, in another study, overexpression of PPARγ was reported to be detrimental to insulin synthesis and secretion (Nakamichi et al., 2003).

In view of these discrepancies, the aims of the present study were to directly establish the levels of expression of PPARγ in cells of the endocrine pancreas from rat and man, and to determine whether PPARγ is functionally active in these cells. We also sought to test the hypothesis that activation of PPARγ might protect β cells from the lipotoxic effects of fatty acids. The results confirm that PPARγ is expressed in islets and in a clonal β-cell line but they provide no evidence to support the proposition that TZDs can protect these cells from fatty acid-induced toxicity.

Methods

Tissue isolation and cell culture

The insulin secreting rat β-cell line, BRIN-BD11 (McClenaghan et al., 1996) was grown in RPMI-1640 medium containing 11 mM glucose. HEK293T cells (a human embryonic kidney epithelium cell line) were a gift from Dr S. Hazlewood and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM). In all cases, the culture medium was supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and were used in experiments when approximately 80% confluent.

Freshly isolated rat islets were obtained from male Wistar rats by collagenase digestion and were harvested for protein and RNA extraction within 2 h of death of the animal. Rat visceral adipose tissue was removed immediately upon killing of the animal and was frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to extraction of protein and RNA. Human islets were isolated from heart beating cadaver organ donors at the Diabetes U.K. Core Islet Transplant Laboratory in Leicester, U.K. The islets were transported in CMRL-1066 medium containing 20% foetal bovine serum. On arrival in our laboratory, they were resuspended in RPMI-1640 containing 10% foetal bovine serum prior to harvesting.

Exposure of BRIN-BD11 cells to palmitate

Palmitate (Sigma, U.K.) was dissolved in 50% ethanol at 70°C and then bound to albumin by incubation with a 10% fatty acid-free bovine albumin solution at 37°C for 1 h. This mixture was then added to serum-free, modified RMPI-1640 medium (containing 5.5 mM glucose) to give a final concentration of 0.5% ethanol and 1% BSA. Cells were treated with the albumin bound palmitate, in the absence of serum, 24 h after seeding into six-well plates (1 × 105 cells well−1). All control wells received 0.5% ethanol and 1% BSA alone and it was confirmed that this procedure did not cause significant loss of viability in the absence of added fatty acids. Test reagents were introduced at appropriate times either prior to or during the period of culture with fatty acids.

Vital dye staining

For routine determination of cell death, vital dye staining was used. Floating and attached cells were collected from each well, centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 150 μl of RPMI-1640 medium. This was then mixed with 150 μl of Trypan Blue (0.4% in PBS). The numbers of live and dead cells were counted using a haemocytometer and the percentage dead cells calculated.

Transfection of cell lines

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells well−1 24 h before transfection. BRIN-BD11 cells were transfected with 0.25 μg of DNA and 1.5 μl of TransFAST® well−1 (Promega, U.K.), and HEK293T cells with 0.12 μg DNA and 0.72 μl TransFAST® well−1 in 100 μl serum-free RPMI medium. After 1 h, a further 100 μl of medium containing 20% serum was added to the cells. Cells were incubated with the transfection reagents for 24 h and then exposed for a further 48 h to test compounds. After treatment, luciferase activity was measured using a ‘Steady Glo' luciferase assay system (Promega, U.K.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection efficiencies were estimated using a β-galactosidase reporter and were typically in the range 25–30% for BRIN-BD11 cells.

Protein extraction

To extract protein from cell lines, islets or adipose tissue, the tissue was washed in ice-cold PBS before addition of lysis buffer (20 m M Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1% Triton X) for 10 min, on ice and then vortexed. The protein extract was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C.

Western blotting

Denatured protein samples were separated on precast 12% Bis/Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, U.K.) for approximately 50 min at 200 V in MOPS-SDS running buffer (50 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propane sulphonic acid, 50 mM Tris Base, 3.5 mM. SDS, 1 mM EDTA). The proteins were transferred from the gel to PVDF membranes by electroblotting and the membranes were then blocked overnight at 4°C in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween (TTBS) and 5% goat serum. PPARγ antibody was diluted 1 : 2000 and incubated for 4 h at room temperature in TTBS plus 1% goat serum. The secondary antibody, anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma) was diluted in TTBS containing 1% goat serum and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. To visualise the immunoreactive bands, 2 ml of CDP-Star (Sigma) chemiluminescent substrate solution was used and the membrane was placed against X-ray film.

Preparation of cDNA

TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, U.K.) was used to extract RNA from cultured cells, islets and tissue extracts. RNA (1 μg) in a total of 10 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water was used in each reverse transcription reaction. To this, 1 μl of random primers (Promega) was added and the mixture was heated at 70°C for 10 min and rapidly cooled on ice. In all, 4 μl RT buffer, 1 μl RNasin (Promega), 2 μl DDT (0.1 M) and 1 μl dNTPs (Invitrogen, U.K.) were added and incubated at 42°C for 5 min before the addition of 1 μl AMV reverse transcriptase enzyme (Promega). This was incubated at 42°C for 1.5 h and the reaction stopped by heating to 95°C for 2 min.

Semiquantitative PCR (Taqman®) analysis

Taqman analysis allows the real-time quantification of PCR products as the amplification reaction proceeds. This approach utilises the 5′–3′ exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus (Taq) polymerase to cleave a dual-labelled probe (Fam probe) annealed to a target sequence during amplification. The release of a fluorogenic tag from the 5′ end of the probe is proportional to the target sequence concentration (copy number). This can be measured in ‘real time', where the increase in emission intensity is followed on a per-cycle basis using the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detector.

A working reaction mix was prepared containing 12.5 μl 2 × Universal PCR Master Mix (2 × TaqMan buffer, 16% glycerol, 0.4 mM dATP, 0.4 mM dCTP, 0.4 mM dGTP, 0.8 mM dUTP, 11 mM MgCl2, 0.05 U μl−1 AmpliTaq Gold and 0.02 U μl−1 UNG from PE Applied Biosystems), 1.5 μl forward primer (5 μM), 1.5 μl reverse primer (5 μM), 0.5 μl Fam-probe (5 μM) and 4 μl of sterile water. The working master mix (20 μl) was added to each well of a MicroAmp optical 96-well PCR plate (PE Applied Biosystems), to which 10 μl of mineral oil and 5 μl of the template cDNA was then added. The reaction was run on an ABI PRISM 7700 thermal cycler using the following cycling parameters: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s with 60°C for 1 min. The primer sequences used in the studies are given in Table 1. A ‘house-keeping' gene (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAPDH) was amplified in parallel with experimental samples and used to normalise the results in order to allow semiquantitative analysis of PPARγ expression.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers and Taqman probes used in the measurement of PPAR isoform levels by real-time, semiquantitative RT–PCR

| Rat PPARα | |

| Forward | AGT TTT TGC GGA CTA CCA GTA CTT AGG |

| Reverse | |

| Probe | CTC TGT CAT CAC AGA CAC CCT CTC TCC AGC |

| Rat PPARδ | |

| Forward | GAC CAG AGC ACA CCC TTC CTT C |

| Reverse | CCC ATC ACA GCC CAT CTG C |

| Probe | ACC TCG CCC AGA ATT CCT CCC CTT CCT |

| Rat PPARγ | |

| Forward | CTG ACC CAA TGG TTG CTG ATT AC |

| Reverse | GGA CGC AGG CTC TAC TTT GAT C |

| Probe | CCT ATG AGC ACT TCA CAA GAA ATT ACC ATG |

Statistics

All individual experiments were performed on at least three separate occasions with the exception of Western blotting (twice). Results are presented as mean values±s.e.m. Differences between values were estimated by analysis of variance and were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

Detection of PPAR isoforms in islet cells

Initially, qualitative RT–PCR was employed to examine whether rat and human islets express PPARγ, and this was confirmed by the amplification of appropriate products from RNA isolated from several batches of islets of both species (not shown). Use of isoform-specific primers further revealed that PPARγ2 is present, although it was not possible to establish whether PPARγ1 is also expressed (as these transcripts differ only because the mRNA encoding PPARγ2 contains a 3′ extension). The studies were then extended to evaluate the relative levels of PPARγ mRNA in rat islets and in BRIN-BD11 β-cells by semiquantitative RT–PCR (Taqman®). In addition, the levels of two additional PPAR isoforms, PPARα and PPARδ, were also monitored. The levels were compared with those found in relevant positive control tissues for each isoform (PPARα and PPARδ – liver; PPARγ − adipose) and were normalised by parallel amplification of GAPDH. The results revealed that rat islet and BRIN-BD11 cells express measurable levels of PPARα mRNA but these were some 200-fold less than those found in liver (Figure 1a). The levels of PPARδ expressed in BRIN-BD11 cells were similar to those in liver, whereas rat islet samples contained less PPARδ mRNA (Figure 1b). Most significantly, rat islets (freshly isolated) and BRIN-BD11 cells were found to express levels of PPARγ mRNA that were similar in magnitude to those found in freshly harvested adipose tissue (islets approximately 60%, BRIN-BD11 cells ∼30%; Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Semiquantitative analysis of the expression of PPAR isoforms in rat islets and BRIN-BD11 cells. Panels a–c: RNA was extracted from rat islets (islet) BRIN-BD11 cells (Brin), rat liver and rat adipose tissue and amplified by semiquantitative RT–PCR (Taqman). Standard curves were constructed from liver (a, b) and adipose (c) and used to monitor the expression of PPAR isoforms (PPARα – panel a; PPARδ – panel b; PPARγ – panel c) in islet and BRIN-BD11 cells. The levels of expression of each PPAR isoform are expressed relative to that found in liver or adipose (defined as 1 in each case). Results are presented as relative expression±s.e.m. (n=3). Panel d: Proteins were extracted from adipose tissue (10 μg; lane 1), BRIN-BD11 cells (10 μg; lane 2), rat islets (5 μg; lanes 3–5), human islets (5 μg; lanes 6, 7) or HEK293 cells expressing PPARγ (5 μg; lane 8 – positive control) and separated by electrophoresis prior to transfer to PVDF membranes. The membranes were then probed with anti-PPARγ serum and immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence.

In order to confirm that the PPARγ mRNA detected by semiquantitative RT–PCR was accompanied by expression of PPARγ protein, Western blotting was employed (Figure 1d). The protein content of each experimental sample was measured prior to electrophoresis and, as expected from the Taqman® analysis, it was confirmed that immunoreactive PPARγ immunoreactivity was readily detectable in rat and human islet samples, and in BRIN-BD11 cells, when a total of 5–10 μg of total cell protein were loaded (Figure 1d).

Functional analysis of PPARγ expression in β cells

Since PPARγ is expressed in rat and human islets and in BRIN-BD11 cells, further studies were undertaken to assess the functional competence of this molecule. BRIN-BD11 cells were employed for these studies due to their relative ease of transfection. The cells were transfected with a reporter construct containing four copies of a PPAR response element (PPRE) upstream of the firefly luciferase gene and then exposed to rosiglitazone. In control cells (not treated with rosiglitazone), expression of the reporter construct resulted in a significant increase in basal luminescence, suggesting that the reporter was active in the BRIN-BD11 cells (untransfected: 18±10 relative light units; transfected: 426±72 U; n=4, P<0.001). However, culture of BRIN-BD11 cells with rosiglitazone over the concentration range 0–1 μM failed to cause any further activation of the reporter (Figure 2). By contrast, the putative endogenous PPARγ ligand, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2) caused a dose-dependent increase in luciferase activity in these cells (Figure 3) although the magnitude of this response was still very modest.

Figure 2.

Effects of rosiglitazone on PPRE-luciferase reporter activity in transfected BRIN-BD11 or HEK 293T cells. BRIN-BD11 cells (squares) were transfected with PPRE-luciferase and HEK-293T cells (circles) were cotransfected with PPRE-luciferase and PPARγ prior to exposure to rosiglitazone and measurement of reporter activity 48 h later. Each point represents the mean value from triplicate determinations±s.e.m. from a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results. *P<0.01 relative to cells incubated in the absence of rosiglitazone.

Figure 3.

Effects of 15dPGJ2 on PPRE-luciferase reporter activity in transfected BRIN-BD11 cells. BRIN-BD11 cells were transfected with a PPRE-luciferase construct prior to exposure to 15dPGJ2 and measurement of luciferase reporter activity 48 h later. Each point represents the mean value from triplicate determinations±s.e.m. from a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results. *P<0.05 relative to cells incubated in the absence of 15dPGJ2.

In view of the unexpected lack of response of transfected BRIN-BD11 cells to TZDs and the rather small increase caused by 15dPGJ2, it was considered necessary to eliminate the possibility that the luciferase reporter construct might be unresponsive to rosiglitazone after transfection. Therefore, equivalent studies were undertaken in HEK293T cells cotransfected with the same PPRE-luciferase reporter together with full-length human PPARγ. When these cells were then cultured with rosiglitazone, a dose-dependent activation of the reporter was observed, over the concentration range 0–1 μM rosiglitazone (EC50∼20 nM; Figure 2). This is fully consistent with the expected potency for activation of the PPRE-reporter construct by rosiglitazone (Davies et al., 2001; Wurch et al., 2002).

Taken together, these data imply that, despite the expression of PPARγ in BRIN-BD11 cells, this receptor is not readily available for activation by rosiglitazone at therapeutically effective concentrations. In support of this, it was also observed that the levels of a known PPARγ-responsive gene, PTEN (Patel et al., 2001; Farrow & Evers, 2003), were not altered (at either the mRNA or protein level) when BRIN-BD11 cells were treated with rosiglitazone. Moreover, cotransfection of BRIN-BD11 cells with the retinoid receptor RXR (which is a transcriptional partner for PPARγ) also failed to reveal a PPARγ-mediated increase in transcriptional activity (not presented).

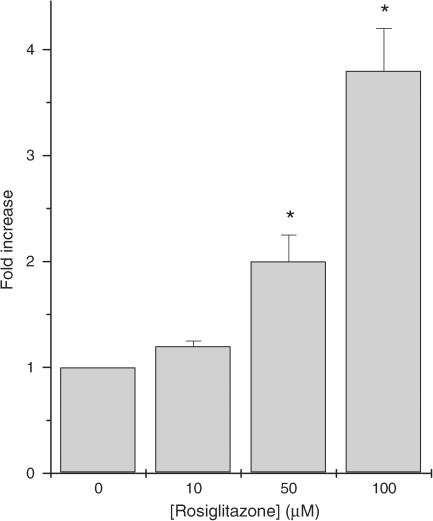

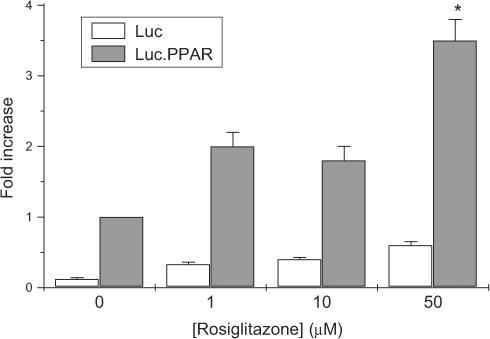

In order to address these issues further, the transfection experiments with the PPRE-luciferase reporter construct were repeated but, in this case, BRIN-BD11 cells were exposed to concentrations of rosiglitazone well beyond those normally required for activation of PPARγ (Figure 4). The results revealed that 50–100 μM rosiglitazone caused a marked increase in luciferase activity suggesting that high concentrations of the drug may activate the endogenous PPARγ present in BRIN-BD11 cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of high concentrations of rosiglitazone on PPRE-luciferase reporter activity in transfected BRIN-BD11. BRIN-BD11 cells were transfected with a PPRE-luciferase construct prior to exposure to rosiglitazone and measurement of luciferase reporter activity 48 h later. Each point represents the mean value±s.e.m. from triplicate determinations from a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results. *P<0.01 relative to cells incubated in the absence of rosiglitazone.

Further studies were then undertaken with transfected HEK293T expressing either the PPRE-luciferase reporter alone or the reporter in combination with human PPARγ. In cells expressing only the luciferase reporter construct, it was noted that an increase in the concentration of rosiglitazone from 1 to 50 μM caused a small increase in reporter activity. However, this was much less than the increase seen in HEK-293T cells expressing both the reporter and PPARγ. Thus, the response to the TZD appeared to be biphasic, with an initial activation of the reporter occurring over the sub-μM range (Figure 2), while a second increase was seen at higher concentrations of rosiglitazone (Figure 5). To ensure that this effect was not a unique property of rosiglitazone, similar studies were also performed with pioglitazone and equivalent data were obtained (not shown). In BRIN-BD11 cells, the initial response to low concentrations of rosiglitazone was not evident (Figure 2) whereas the second response, elicited by higher levels of the drug, was observed (Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Effects of high concentrations of rosiglitazone on PPRE-luciferase reporter activity in transfected HEK-293T cells. HEK-293T cells were transfected with PPRE-luciferase alone (open bars) or PPRE-luciferase, together with PPARγ (grey bars) prior to exposure to rosiglitazone and measurement of luciferase reporter activity 48h later. Each point represents the mean value±s.e.m. from triplicate observations from a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results. *P<0.01 relative to the equivalent cells incubated in the presence of 10 μM rosiglitazone.

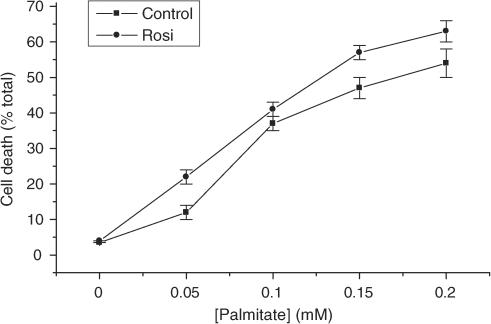

Effects of rosiglitazone on palmitate-induced toxicity in β cells

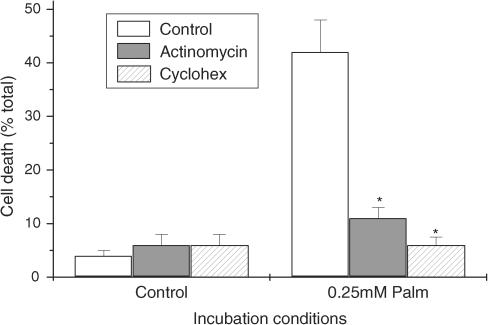

Since it has been deduced from studies conducted in vivo that rosiglitazone may protect pancreatic β cells from the lipotoxic effects of fatty acids, further experiments were undertaken to investigate whether a similar response also occurs in vitro. The saturated fatty acid palmitate was selected for these experiments since palmitate is the most abundant circulating fatty acid in vivo and it is known to cause the death of rat and human β cells incubated in vitro (Maedler et al., 2001; 2003; Eitel et al., 2002; Welters et al., 2004a, 2004b). In accord with this, exposure of BRIN-BD11 cells to palmitate caused a rapid, dose-dependent loss of viability (Figure 6). This response was completely prevented if BRIN cells were also exposed to actinomycin D or cycloheximide during treatment with palmitate (Figure 7) consistent with the proposal that palmitate-induced cell death primarily involves the activation of a process of programmed cell death, under these conditions (Welters et al., 2004a, 2004b).

Figure 6.

BRIN-BD11 cells were cultured in the absence (squares) or presence (circles) of 1 μM rosiglitazone for 24 h. After this time, increasing concentrations of palmitate were added (complexed to bovine serum albumin) and incubation continued for a further 18 h. At the end of this period, the cells were harvested and their viability was determined by vital dye staining. Each point represents the mean value±s.e.m. from quadruplicate measurements from a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results.

Figure 7.

Effect of inhibition of transcription or translation on palmitate-induced cell death. BRIN-BD11 cells were incubated under control conditions or in the presence of 0.25 mM palmitate (bound to 1% fatty acid-free albumin) and either 2 μg ml−1 actinomycin-D or 10 μg ml−1 cycloheximide in cell culture medium containing 5.5 mM glucose. Cell death was determined after 18 h by vital dye staining. Results represent the mean level of viability±s.e.m. from triplicate determinations in a representative experiment that was repeated three times with similar results. *Significantly less than palmitate alone (P<0.01).

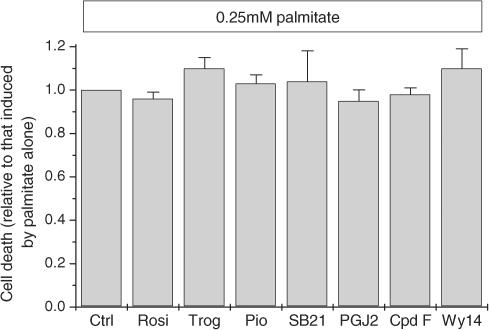

Exposure of cells to a therapeutically-effective concentration of rosiglitazone (1 μM) for 24 h prior to the addition of palmitate failed to attenuate the extent of cell death induced by palmitate, even at low concentrations of the fatty acid (Figure 6). In view of the data indicating that rosiglitazone may only be active in BRIN-BD11 cells at higher concentrations, the experiment was repeated by exposure to 0.25 mM palmitate in the presence of 50 μM rosiglitazone. However, once again, no protective effects were observed (not shown). Similar results were also obtained with a wide range of other PPARγ ligands (Figure 8) and when cells were exposed to either the selective PPARδ agonist, compound F, or to Wy14643, an agonist of PPARα (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Effects of various PPAR ligands on palmitate-induced cell death in BRIN-BD11 cells. BRIN-BD11 cells were pretreated for 24 h under control conditions (Ctrl) or in the presence of rosiglitazone (Rosi, 1 μM), troglitazone (Trog, 1 μM), Pioglitazone (Pio, 1 μM), SB219994 (SB21, 2 nM), 15dPGJ2 (PGJ2, 3 μM), compound F (Cpd F, 5 μM) or Wy14643 (Wy14, 20 μM). After this time, 0.25 mM palmitate was added (complexed to bovine serum albumin) and incubation continued for a further 18 h. At the end of this period, the cells were harvested and their viability was determined by vital dye staining. The reduction in cell viability was determined under each incubation condition and is expressed relative to that seen in the presence of palmitate alone.

Discussion

TZDs are now accepted as effective therapeutic agents for use in the management of insulin resistance associated with type II diabetes (Camp, 2003; Diamant & Heine, 2003; Stumvoll, 2003; Tadayyon & Smith, 2003). Their effects are considered to reflect the selective activation of PPARγ in adipocytes and there is strong evidence to support this view. However, an increasing body of data implies that TZDs may also exert effects at additional sites and that they may even promote beneficial effects that are not directly related to improvements in insulin resistance. Among the latter are responses occurring at the level of the pancreatic β cell since it has been reported, in both animal models and in man, that treatment with TZDs leads to enhanced β-cell function (Cavaghan et al., 1997; Buckingham et al., 1998; Ishida et al., 1998; Prigeon et al., 1998; Shimabukuro et al., 1998; Jia et al., 2000; Finegood et al., 2001; Buchanan et al., 2002; Ovalle & Bell, 2002). This is likely to reflect a deceleration in the rate of apoptosis of β cells mediated by gluco- or lipotoxicity, and could contribute significantly to the therapeutic efficacy of the drugs. However, despite this evidence, it remains uncertain whether TZDs (or other PPARγ agonists) can exert direct effects on the pancreatic β cell since, although PPARγ expression has been reported in the endocrine pancreas (Braissant et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 1998; Dubois et al., 2000; Patane et al., 2002), other studies have failed to detect PPARγ transcripts in this tissue (Flamez et al., 2002; Nakamichi et al., 2003).

We now show that both rat and human islets of Langerhans express PPARγ and we reveal that at least part of this represents PPARγ2, an isoform that is often considered to be largely restricted to the adipocyte (Stumvoll & Haring, 2002). The expression of PPARγ was confirmed by semiquantitative RT–PCR (Taqman®) which demonstrated that the level of PPARγ transcripts in islets is similar in magnitude to that found in white adipose tissue. Expression of PPARγ was confirmed at the protein level (Figure 1d), suggesting that the endocrine pancreas could be a target for PPARγ agonists in vivo. Analysis of a clonal β-cell line (BRIN-BD11) confirmed these data, demonstrating that the expression of PPARγ in extracts of whole islets was not restricted to the α- or δ-cells (or to nonendocrine cell types) present in this tissue.

Despite the evidence that PPARγ is expressed in islet cells, transfection of clonal BRIN-BD11 cells with a PPRE-reporter construct failed to yield evidence of increased luciferase activation when the cells were exposed to rosiglitazone at concentrations of up to 1 μM. Similar effects were seen whether the transfected cells were cultured with rosiglitazone for either 24 or 96 h and when an independent assay of PPARγ activation (changes in expression of the PPARγ-responsive gene, PTEN (Patel et al., 2001; Farrow & Evers, 2003)) was used. This lack of response was not due to any intrinsic defect in the reporter construct since control experiments revealed that transfection of the reporter into BRIN-BD11 cells resulted in a marked increase in background luciferase activity. Moreover, the same reporter construct was activated by sub-μM concentrations of rosiglitazone when expressed in HEK293T cells. This is consistent with the pharmacological potency of rosiglitazone for binding to PPARγ and with its functional effects in transfected HEK293T cells, as reported in previous studies (Lehmann et al., 1995; Young et al., 1998; Ferry et al., 2001; Wurch et al., 2002). Thus, these results imply that, although PPARγ is expressed in BRIN-BD11 cells, it is relatively resistant to activation by therapeutically effective concentrations of rosiglitazone.

The putative endogenous PPARγ ligand 15dPGJ2 (Nosjean & Boutin, 2002) did cause a modest activation of the PPRE-luciferase construct in BRIN-BD11 cells but this effect was small in magnitude and may have resulted from crossactivation of either PPARα or PPARδ, since RT-PCR analysis confirmed that these are also present in β cells.

In previous studies, TZDs have been reported to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, to lower islet triacylglyceride levels and to elicit changes in islet cell gene expression (Masuda et al., 1995; Ohtani et al., 1998; Shimabukuro et al., 1998; Sanchez et al., 2002; Augstein et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2003). These actions could be taken to imply a role for PPARγ in β-cell function. However, several of these studies were conducted with troglitazone, a drug that is now known to mediate some responses that are independent of PPARγ (Game et al., 2003; Laurora et al., 2003; Narayanan et al., 2003). In addition, data were sometimes obtained using islets that were removed from animals exposed to TZDs in vivo, which leaves open the possibility that any effects may have been mediated by indirect mechanisms. Thus, there is little firm evidence that β cells are directly responsive to therapeutic concentrations of PPARγ ligands and the present work suggests that this may not be the case.

When the concentration of rosiglitazone was increased beyond that normally required for effective activation of PPARγ, a significant increase in PPRE-luciferase activity was detected in transfected BRIN-BD11 cells. This confirms that rosiglitazone is able to activate PPARγ in BRIN-BD11 cells but implies that PPARγ may be unusually resistant to activation by rosiglitazone in these cells. However, when similar experiments were repeated in HEK293T cells, it became clear that the secondary activation elicited by high concentrations of rosiglitazone was not restricted to the β-cell line. Moreover, since this secondary increase was dramatically attenuated in HEK293T cells expressing only the reporter construct (in the absence of PPARγ), it can be concluded that the effect is mediated by PPARγ.

Thus, it appears that high concentrations of rosiglitazone (well above those found in patients exposed to therapeutically effective oral doses of the compound) can elicit a PPARγ-mediated transactivation of PPREs in BRIN-BD11 β cells, but that it does not do so at lower drug concentrations. The reasons for this are unclear but imply that the availability of coactivator proteins (e.g. PGC-1) may be limiting, or that the activity of corepressor proteins is sufficiently high to prevent the functional activation of PPARγ when sub-μM concentrations of rosiglitazone are present. If a similar situation exists in vivo, then these data cast doubt on the likelihood that TZDs exert direct effects on β cells. Clearly, however, this cannot be formally eliminated since the possibility remains that, given the high levels of PPARγ expression, conditions may be such in vivo that the protein is rendered responsive to agonists.

To investigate the possibility that rosiglitazone may exert direct protective effects at the level of the pancreatic β cell, BRIN-BD11 cells were exposed to the lipotoxic effector palmitic acid. As expected, this resulted in a dose-dependent loss of cell viability that was completely abrogated by either actinomycin D or cycloheximide (Figure 7). These results confirm that the induction of cell death by palmitate requires active gene transcription and translation and, as such, they suggest that the mechanism of cell death involves the activation of a process of programmed cell death rather than a nonspecific lytic action. This is consistent with conclusions arising from other studies conducted with palmitate in BRIN-BD11 cells (Welters et al., 2004a, 2004b) and, importantly, it confirms that the cytotoxic effects of palmitate can be attenuated under appropriate in vitro conditions. However, neither rosiglitazone (up to 50 μM) nor a range of other PPARγ ligands was able to reduce the extent of cell death induced by palmitate.

These results strongly suggest that the protective effects of TZDs observed under lipotoxic conditions in vivo are unlikely to reflect a direct action on the pancreatic β cell. Rather, any beneficial effects observed at the level of the β cell are more likely to be secondary to the improved insulin resistance and lowered lipid levels that accompany TZD therapy.

While the present manuscript was under review, Lupi et al. (2004) also observed that human islets express PPARδ and PPARγ, although, they did not detect PPARα expression. These authors reported that rosiglitazone can counteract fatty acid-induced alterations in PPARγ expression and insulin secretion in human islets maintained in culture, suggesting that cultured human β cells may be responsive to rosiglitazone. However, it is important to note that the parameters measured and the conditions employed for human islet incubation were very different from those used here. For example, no direct measurements of islet cell viability or PPARγ functionality were made in the human islet studies. Additionally, although it was found that fatty acids and rosiglitazone altered PPARγ transcript levels, the authors were not able to confirm that this correlated with PPARγ protein levels (or activity) nor that the effects of rosiglitazone were mediated by PPARγ. Indeed, since another insulin-sensitising compound, metformin, (which does not activate PPARγ) also prevented the fatty acid-induced functional impairment, it is possible that a PPAR-independent pathway is involved. In this context, it is also noteworthy that selective deletion of PPARγ from the β cells of the mouse fails to affect glucose homeostasis and has prompted the conclusion that the antidiabetic actions of rosiglitazone do not require the expression of PPARγ in β cells (Rosen et al., 2003).

Overall, therefore, the present results provide firm evidence that pancreatic β cells express PPARγ but they do not support the view that this molecule is necessarily available to mediate protective responses when β cells are exposed to therapeutic concentrations of TZDs under conditions of lipotoxicity. In considering the implications of these findings, it should be noted that the expression of the PPARγ coactivator molecule, PGC-1, is subject to regulation in β cells (De Souza et al., 2003) and it remains possible, therefore, that the availability of this (or a related) molecule may be more important to the functionality of PPARγ than the absolute level of the transcription factor itself.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Diabetes U.K., the Northcott-Devon Medical Foundation and the award of a Lilly Diabetes Research Grant.

Abbreviations

- 15dPGJ2

15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

- PPRE

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor response element

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

- ZDF rat

Zucker diabetic fatty rat

References

- AUGSTEIN P., DUNGER A., HEINKE P., WACHLIN G., BERG S., HEHMKE B., SALZSIEDER E. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice by troglitazone is associated with modulation of ICAM-1 expression on pancreatic islet cells and IFN-gamma expression in splenic T cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;304:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAISSANT O., FOUFELLE F., SCOTTO C., DAUCA M., WAHLI W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCHANAN T.A., XIANG A.H., PETERS R.K., KIOS S.L., MARROQUIN A., GOICO J., OCHOA C., TAN S., BERKOWITZ K., HODIS H.N., ZEN S.P. Preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk hispanic women. Diabetes. 2002;51:2796–2803. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCKINGHAM R.E., AL-BARAZANJI K.A., TOSELAND C.D., SLAUGHTER M., CONNOR S.C., WEST A., BOND B., TURNER N.C., CLAPHAM J.C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, rosiglitazone, protects against nephropathy and pancreatic islet abnormalities in Zucker fatty rats. Diabetes. 1998;47:1326–1334. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMP H.S. Thiazolidinediones in diabetes: current status and future outlook. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003;4:406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAVAGHAN M.K., EHRMANN D.A., BYRNE M.M., POLONSKY K.S. Treatment with the oral antidiabetic agent troglitazone improves beta cell responses to glucose in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:530–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI119562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CNOP M., HANNAERT J.C., PIPELEERS D.G. Troglitazone does not protect rat pancreatic beta cells against free fatty acid-induced cytotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;63:1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00860-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES S.S., PONTSLER A.V., MARATHE G.K., HARRISON K.A., MURPHY R.C., HINSHAW J.C., PRESTWICH G.D., HILAIRE A.S., PRESCOTT S.M., ZIMMERMAN G.A., MCINTYRE T.M. Oxidized alkyl phospholipids are specific, high affinity peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands and agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;19:16015–16023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE SOUZA C.T., GASPARETTI A.L., PEREIRA-DA-SILVA M., ARAUJO E.P., CARVALHEIRA J.B., SAAD M.J.A., BOSCHERO A.C., CARNEIRO E.M., VELLOSO L.A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1-dependent uncoupling protein-2 expression in pancreatic islets of rats: a novel pathway for neural control of insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1522–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAMANT M., HEINE R.J. Thiazolidinediones in type 2 diabetes mellitus: current clinical evidence. Drugs. 2003;63:1373–1405. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOIS M., PATTOU F., KERR-CONTE J., GMYR V., VANDEWALLE B., DESREUMAUX P., AUWERX J., SCHOONJANS K., LEFEBYRE J. Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) in normal human pancreatic islet cells. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1165–1169. doi: 10.1007/s001250051508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EITEL K., STAIGER H., BRENDEL M.D., BRANDHORST D., BRETZEL R.G., HARING H.U., KELLERER M. Different role of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in beta-cell apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;299:853–856. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARROW B., EVERS B.M. Activation of PPARγ increases PTEN expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;301:50–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRY G., BRUNEAU V., BEUVERGER P., GOUSSARD M., RODRIGUEZ M., LAMAMY V., DROMAINT S., CANET E., GALIZZI J.P., BOUTIN J.P. Binding of prostaglandins to human PPARγ: tool assessment and new natural ligands. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;417:77–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00907-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINEGOOD D., MCARTHUR M.D., KOJWANG D., THOMAS M.J., TOPP B.G., LEONARD T., BUCKINGHAM R.E. Cell mass dynamics in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Rosiglitazone prevents the rise in net cell death. Diabetes. 2001;50:1021–1029. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLAMEZ D., BERGER V., KRUHOFFER M., ORNTOFT T., PIPELEERS D., SCHUIT F.C. Critical role for cataplerosis via citrate in glucose-regulated insulin release. Diabetes. 2002;51:2018–2024. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURNSINN C., WALDHAUSL W. Thiazolidinediones: metabolic actions in vitro. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1211–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAME B.A., XU M., LOPES-VIRELLA M.F., HUANG Y. Regulation of MMP-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells by insulin sensitizing thiazolidinediones. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIDA H., KATO S., NISHIMURA M., MIZUNO N., FUJIMOTO S., MUKAI E., KAJIKAWA M., YAMADA Y., ODAKA H., IKEDA H., SENIO Y. Beneficial effect of long-term combined treatment with voglibose and pioglitazone on pancreatic islet function of genetically diabetic GK rats. Horm. Metab. Res. 1998;30:673–678. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIA D.M., TABARU A., NAKAMURA H., FUKUMITSU K.I., AKIYAMA T., OTSUKI M. Troglitazone prevents and reverses dyslipidemia, insulin secretory defects, and histologic abnormalities in a rat model of naturally occurring obese diabetes. Metabolism. 2000;49:1167–1175. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.8599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAI T., HIROSE H., SETO Y., FUJITA H., FUJITA H., UKEDA K., SARUTA T. Troglitazone ameliorates lipotoxicity in the beta cell line INS-1 expressing PPAR gamma. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2002;56:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURORA S., PIZZIMENTI S., BRIATORE F., FRAIOLI A., MAGGIO M., REFFO P., FERRETTI C., DIANZANI M.U., BARRERA G. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands affect growth-related gene expression in human leukemic cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;305:932–942. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEHMANN J.M., MOORE L.B., SMITH-OLIVER T.A., WILKISON W.O., WILSON T.M., KLIEWER S.A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma PPAR gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUPI R., DEL GUERRA S., MARSELLI L., BUGLIANI M., BOGGI U., MOSCA F., MARCHETTI P. Rosiglitazone prevents the impairment of human islet function induced by fatty acids. Evidence for a role of PPARγ2 in the modulation of insulin secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:E560–E567. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00561.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAEDLER K., SPINAS G.A., DYNTAR D., MORITZ W., KAISER N., DONATH M. Distinct effects of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids on β-cell turnover and function. Diabetes. 2001;50:69–76. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAEDLER K., OBERHOLZER J., BUCHER P., SPINAS G.A., DONATH M.Y. Monounsaturated fatty acids prevent the deleterious effects of palmitate and high glucose on human pancreatic β-cell turnover and function. Diabetes. 2003;52:726–733. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASUDA K., OKAMOTO Y., TSUURA Y., KATO S., MIURA T., TSUDA K., HORIKOSHI H., ISHIDA H., SEINO Y. Effects of Troglitazone (CS-045) on insulin secretion in isolated rat pancreatic islets and HIT cells: an insulinotropic mechanism distinct from glibenclamide. Diabetologia. 1995;38:24–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02369349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLENAGHAN N.H., BARNETT C.R., AH-SING E., ABDEL-WAHAB Y.H., O'Harte F.P., YOON T.W., SWANSTON-FLATT S.K., FLATT P.R. Characterization of a novel glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cell line, BRIN-BD11, produced by electrofusion. Diabetes. 1996;45:1132–1140. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMICHI Y., KIKUTA T., ITO E., OHARA-IMAIZUMI M., NISHIWAKI C., ISHIDA H., NAGAMATSU S. PPAR-gamma overexpression suppresses glucose-induced proinsulin biosynthesis and insulin release synergistically with pioglitazone in MIN6 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;306:832–836. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARAYANAN P.K., HART T., ELCOCK F., ZHANG C., HAHN L., MCFARLAND D., SCHWARZ L., MORGAN D.G., BUGELSKI P. Troglitazone-induced intracellular oxidative stress in rat hepatoma cells: a flow cytometric assessment. Cytometry. 2003;52A:28–35. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSJEAN O., BOUTIN J.A. Natural ligands of PPARγ: are prostaglandin J2 derivatives really playing the part. Cell Signal. 2002;7:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHTANI K.I., SHIMIZU H., SATO N., MORI M. Troglitazone (CS-045) inhibits beta-cell proliferation rate following stimulation of insulin secretion in HIT-T 15 cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:172–178. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLEFSKY J.M. Treatment of insulin resistance with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:467–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI10843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OVALLE F., BELL D.S. Clinical evidence of thiazolidinedione-induced improvement of pancreatic beta-cell function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2002;4:56–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2002.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATANE G., ANELLO M., PIRO S., VIGNERI R., PURRELLO F., RABUAZZO A.M. Role of ATP production and uncoupling protein-2 in the insulin secretory defect induced by chronic exposure to high glucose or free fatty acids and effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibition. Diabetes. 2002;51:2749–2756. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL L., PASS I., COXON P., DOWNES C.P., SMITH S.A., MACPHEE C.H. Tumor suppressor and anti-inflammatory actions of PPARγ agonists are mediated via upregulation of PTEN. Curr. Biol. 2001;10:764–768. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRIGEON R.L, KAHN S.E., PORTE D., JR Effect of troglitazone on β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:819–823. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODUIT R., MORIN J., MASSE F., SEGALL L., ROCHE E., NEWGARD C.B., ASSIMACOPOULOS-JEANNET F., PRENTKI M. Glucose down-regulates the expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha gene in the pancreatic beta-cell. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35799–35806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSEN E.D., KULKARNI R.N., SARRAF P., OZCAN U., OKADA T., HSU C-H., EISENMAN D., MAGNUSON M.A., GONZALEZ F.J., KAHN C.R., SPEIGELMANN B.M. Targeted elimination of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in β-cells leads to abnormalities in islet mass without compromising glucose homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:7222–7229. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7222-7229.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANCHEZ J.C., CONVERSET V., NOLAN A., SCHMID G., WANG S., HELLER M., SENNITT M.V., HOCHSTRASSER D.F., CAWTHORNE M.A. Effect of rosiglitazone on the differential expression of diabetes-associated proteins in pancreatic islets of C57Bl/6 lep/lep mice. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:509–516. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200033-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMABUKURO M., ZHOU Y.T., LEE Y., UNGER R.H. Troglitazone lowers islet fat and restores beta cell function of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3547–3550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUMVOLL M. Thiazolidinediones – some recent developments. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003;12:1179–1187. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.7.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUMVOLL M., HARING H. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 Pro12Ala polymorphism. Diabetes. 2002;8:2341–2347. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADAYYON M., SMITH S.A. Insulin sensitisation in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003;12:307–324. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELTERS H.J., SMITH S.A., TADAYYON M., SCARPELLO J.H.B., MORGAN N.G. Evidence that protein kinase Cδ is not required for palmitate-induced cytotoxicity in BRIN-BD11 β-cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004a;32:27–235. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0320227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELTERS H.J., TADAYYON M., SCARPELLO J.H.B., SMITH S.A., MORGAN N.G. Mono-unsaturated fatty acids protect against β-cell apoptosis induced by saturated fatty acids, serum withdrawal or cytokine exposure. FEBS Lett. 2004b;560:103–108. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WURCH T., JUNQUERO D., DELHON A., PAYWELS J. Pharmacological analysis of wild-type alpha, gamma and delta subtypes of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2002;365:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s00210-001-0504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG L., AN H.X., DENG X.L., CHEN L.L., LI Z.Y. Rosiglitazone reverses insulin secretion altered by chronic exposure to free fatty acid via IRS-2-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2003;24:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG P.W., BUCKLE D.R., CANTELLO B.C., CHAPMAN H., CLAPHAM J.C., COYLE P.J., HAIGH D., HINDLEY R.M., HOLDER J.C., KALLENDER H., LATTER A.J., LAWRIE K.W., MOSSAKOWSKA D., MURPHY G.J., ROXBEE COX L., SMITH S.A. Identification of high-affinity binding sites for the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) in rodent and human adipocytes using a radioiodinated ligand for peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:751–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Y.T., SHIMABUKURO M., WANG M.Y., LEE Y., HIGA M., MILBURN J.L., NEWGARD C.B., UNGER R.H. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in disease of pancreatic beta cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:8898–8903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]