Abstract

We studied the effects of indomethacin on endothelium-dependent and -independent vascular relaxation in rat thoracic aortic rings and its role in superoxide anion (O2−) production.

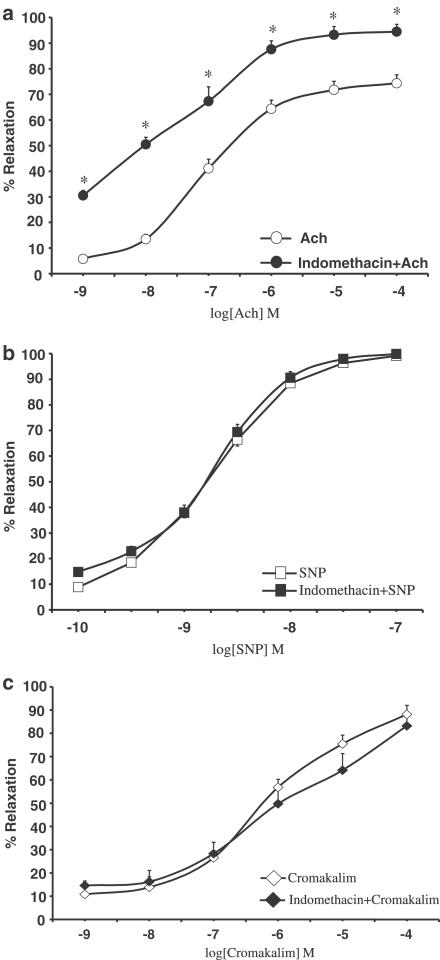

We measured isometric force changes in response to acetylcholine (Ach, 1 nM–0.1 mM), sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 0.1 nM–0.1 μM; a nitric oxide (NO) donor) and cromakalim (1 nM–0.1 mM; a KATP-channel opener) in aorta rings contracted with norepinephrine (NE, 0.1 μM). Indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) significantly increased Ach-induced vasodilation (EC50 decreased from 8.99 μM to 16 nM). The free radical scavengers superoxide dismutase and 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl completely reverted these effects. Indomethacin did not affect SNP- or cromakalim-induced vasodilation.

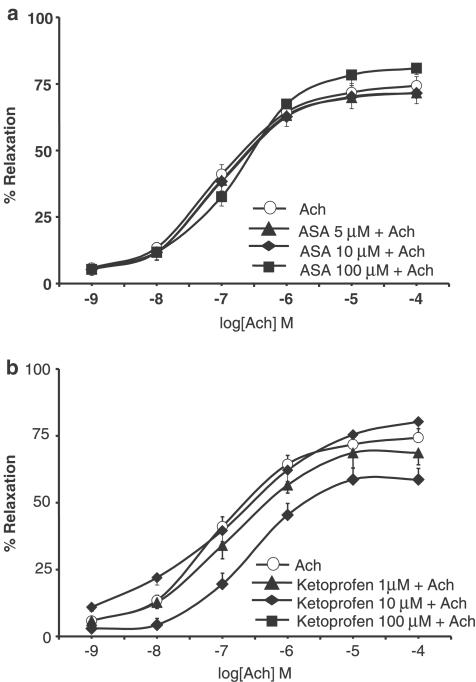

Neither acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, 5–100 μM; 15 min) nor ketoprofen (1−100 μM; 15 min) affected Ach, SNP and cromakalim concentration–response curves.

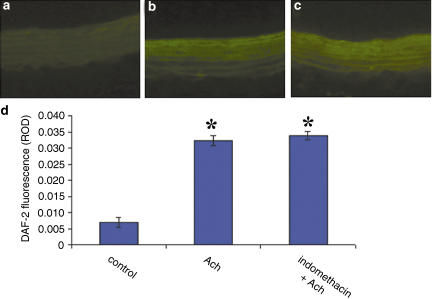

Incubation of the aorta with Ach (1 μM) rapidly and markedly increased intracellular NO fluorescence in the aorta endothelium. Indomethacin did not affect Ach-induced NO production.

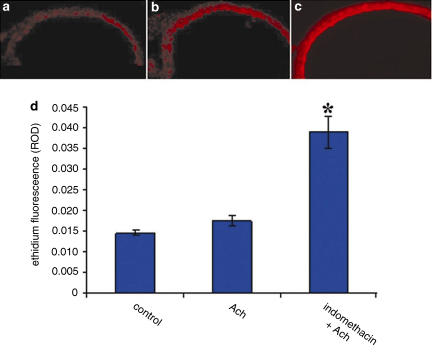

We measured intracellular O2− in the aorta endothelium with dihydroethidium (DHE) dye. Indomethacin significantly increased O2− fluorescence versus controls. Neither ASA nor ketoprofen affected O2− fluorescence.

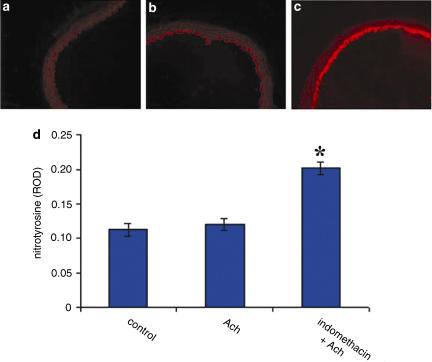

Nitrotyrosine staining was increased in indomethacin-treated aorta sections exposed to Ach, which indicates endogenous formation of peroxynitrite. It was low in aorta sections exposed to Ach alone or with ASA or ketoprofen.

We cannot judge if indomethacin-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation damages or protects the cardiovascular system. Here, we show that indomethacin acts on the cardiovascular system regardless of cyclooxygenase inhibition.

Keywords: Indomethacin, vasodilation, nitric oxide, superoxide anion, peroxynitrite

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have long been used to treat inflammation and hyperalgesia and to counteract platelet aggregation in cardiovascular diseases (Brooks et al., 2003). They act by inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, plasminogen activator, leukotrienes and proinflammatory cytokines. Some NSAIDs are potent scavengers of reactive oxygen species and inhibit intracellular oxidative activity (Maffei Facino et al., 1993b; Bevilacqua et al., 1994; Mouithys-Mickalad et al., 2000). Nimesulide, indomethacin and diclofenac exert antioxidant effects in the liposome membrane model (Maffei Facino et al., 1993a). In addition, aspirin protects endothelial cells from oxidant damage via the nitric oxide (NO) cyclic GMP pathway (Grosser & Schroder, 2003).

A body of data shows that elevated oxidative stress contributes to the endothelial dysfunction associated with atherosclerosis, hypertension and heart failure (Cai & Harrison, 2000; Oguogho & Sinzinger, 2000; Berry et al., 2001; Sorescu et al., 2001; Warnholtz et al., 2001). Indeed, superoxide anions (O2−) reduce NO bioavailability, thus leading to impaired endothelial function. Thus, reduced NO availability can result from decreased activity of the NO-production pathway or increased oxidative inactivation of NO induced by O2−. Superoxide anions may directly inactivate NO (Gryglewski et al., 1986; Dobrucki et al., 2000) and the product of this reaction, peroxynitrite (ONOO−), can hydroxylate and nitrate aromatic compounds and induce cellular injury (Ronson et al., 1999).

On the other hand, low, strictly controlled O2− levels exert an important regulatory function (Droge, 2002, Sorescu & Griendling, 2002, Wolin et al., 2002). For example, O2− are involved in activating the hypertrophic responses of vessels and cardiomyocytes (Sorescu & Griendling, 2002), and, at least in some vascular beds, upon dismutation to hydrogen peroxide, they may contribute to endothelium-dependent vasodilation (Wolin et al., 2002). Thus, the delicate balance between the beneficial and detrimental effects of O2− is clearly an important aspect of the regulation of vascular function.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of indomethacin on endothelium-dependent and -independent vascular relaxation in aortic rings of rats and its role in oxidative stress.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rats, weighting 250–300 g, were housed two per cage under controlled light (12 : 12 h light : dark cycle; lights on 06:00) and environmental conditions (ambient temperature 20−22°C, humidity 55−60%) for at least 1 week before beginning experiments. Chow and tap water were freely available to animals. Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Second University of Naples. Animal care was in compliance with Italian (D.L.116/92) and EEC (O.J. of E.C. L358/1 18/12/86) regulations on the protection of laboratory animals.

Preparation of aortic rings

WKY rats were anesthetized with diethyl ether and killed with a small animal guillotine. The thoracic aorta was immediately excised and placed in Krebs' solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25 and glucose 11.1, maintained at room temperature. The thoracic aorta was carefully cleaned of adhering fat, and connective tissue removed and cut into transverse rings (3–4 mm). Aortic rings were mounted, under 2 g resting tension, in an organ bath (Ugo Basile, Milan, Italy) containing ±10 ml Kreb's solution and maintained at 37°C, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Isometric measurement were recorded with a Grass FTO3C transducer and displayed on PowerLab (AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia). The tissue was allowed to equilibrate for 60 min before experiments were carried out, during which time the resting tension was readjusted to 2 g, as required.

Experimental protocol

The aortic rings were submaximally contracted with 0.1 μM norepinephrine (NE). The presence of endothelium was verified by the ability of 1 μM acetylcholine (Ach) to induce relaxation. Concentration–response curves of aortic rings to Ach (1 nM–0.1 mM), sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 0.1 nM–0.1 μM; an NO donor) and cromakalim (1 nM–0.1 mM; a KATP-channel opener) were constructed with and without indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min), acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, 5–100 μM; 15 min) and ketoprofen (1−100 μM; 15 min). To examine the effect of NO on endothelium-dependent vasodilation, we incubated the rings for 15 min with N-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA, 0.1 mM; a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor). To ascertain the role of reactive oxygen species, we preincubated the rings with superoxide dismutase (SOD; 150–450 U ml−1) and the radical scavenger 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (Tempol; 1 and 10 μM) that permeates the membrane.

Measurement of NO production by diaminofluorescein

We used the fluorescent NO indicator 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA) to measure intracellular NO concentration in the endothelial cells of rat thoracic aorta (Kojima et al., 1998). This compound readily enters cells and is hydrolyzed by cytosolic esterases to diaminofluorescein (DAF-2), which is trapped inside the cells. In the presence of NO and oxygen, a relatively nonfluorescent DAF-2 is transformed into the highly green fluorescent triazole form, DAF-2T. Thus, increases in triazole form of diaminofluorescein-2 (DAF-2T) fluorescence reflect increases in intracellular NO concentration. After 30 min of equilibrium in Krebs buffer at 37°C, the aorta segments were incubated with DAF-2 DA (10 μM; Calbiochem) for 2 h. Aortic segments were exposed to DAF under basal conditions and after Ach administration, in the presence or absence of indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min), ASA (5 μM; 15 min) and ketoprofen (1 μM; 15 min). To confirm that fluorescence was related to NO production, we used the NOS inhibitor L-NMMA (0.1 mM). The aorta segments were then included in Killik frozen section medium (Biooptica), quickly frozen, and cut into 20-μm thick sections in a cryostat (Reichert-Jung). Sections were placed on polylysinated microscope slides, closed in Antifade™ (Molecular Probes) medium, and analyzed using a filter for FITC (excitation 450–490 nm; emission 515–560 nm).

Measurement of ex vivo aortic O2− production with dihydroethidium

We used dihydroethidium (DHE), an oxidative fluorescent dye, to localize O2− in aortic segments in situ (Castilho et al., 1999). Vascular rings were rapidly removed, transferred in Krebs buffer and left to equilibrate for 30 min at 37°C. The rings were stimulated with Ach (1 μM; 30 min), added to the Krebs buffer. To examine whether O2− was involved in the effect exerted by NSAIDs on endothelium, aorta segments were incubated with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min), ASA (5 μM; 15 min) or ketoprofen (1 μM; 15 min), before the response to Ach was measured. Aorta sections were prepared as for DAF measurements. Sections were placed on polylysinated microscope slides, incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 0.1 μM DHE (Molecular Probes) in the dark. Images were obtained with a TRITC (tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate) filter (excitation 555 nm; emission 580 nm).

Localization of nitrotyrosine by immunofluorescence

We used immunofluorescence methods to verify nitrotyrosine production in aorta segments. Assays were performed on aorta segments prepared as for O2− measurement with DHE. The aorta was fixed in 4% phosphate buffer saline (PBS) formaldehyde and included in Killik frozen section medium (Biooptica), frozen at −20°C, and cut into 20-μm thick sections in a cryostat (Reichert-Jung). Sections were placed on polylysinated microscope slides. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (DBA, Milan, Italy; 1 : 100)+BSA 1%+Triton X-100 0.1% in PBS. After three washes in PBS, the sections were incubated in rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (DBA) 1 : 100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes in PBS, the sections were stored at −20°C until image acquisition and processing. All sections were stained simultaneously to reduce staining variability.

Drugs

NE, Ach chloride, SNP, cromakalim, L-NMMA and all the other reagents and compounds used for Krebs' solution were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Indomethacin was from Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA (Parma, Italy), ketoprofen from the Istituto Biochimico Italiano SpA (Milan, Italy), ASA from Bayer (Köln, Germany) and Tempol from Alexis Italia (Vinci, Florence, Italy). Drugs were dissolved in distilled deionized water to prepare stock solution (except for indomethacin, which was dissolved in saline) and further dilutions were made in Krebs' solution. The stock solution of SNP was light-proofed with aluminum foil.

Image analysis

Sections were analyzed using a fluorescence Zeiss Axioskope 20 equipped with a high-resolution analogue CCD camera (Hamatsu Photonics), and a PC-assisted image acquisition and analysis system (MCID-2, ImagingRes., Ontario, CA, U.S.A.). Sections were digitized at medium magnification (objective: × 10). Four areas per ring for a total of six aortic rings were sampled for each experimental condition (24 images per experimental condition). The endothelium was manually defined for each image. A target definition was used to avoid reading background staining. All measurements were conducted ‘blind' and the sequence of treatments was randomized to limit bias. The integrated relative optical density (ROD) in the target region was calculated.

For fluorescence analysis, the lamp was tested for optimal temporal stability. Because of fluorescence decay, all images were taken within 30 s of light exposure. Each image was Kalmann-averaged 32 × to increase the signal/noise ratio. The gain was set to 3 ×, which gave linear responses in the measurement range we used. Photo bleaching of specimens was controlled using the Antifade medium, analyzing the slices as fast as possible, and using a relatively low-power fluorescent lamp (50 W). Finally, the digitized images were inverted using the specific software filter, to obtain white background and dark signal, because ROD is measured according to the intensity of dark regions.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Vascular responses to vasodilator agonists are reported as the percentage reduction in tension (percent relaxation) compared with the level of tone induced by contraction with NE. The results of experiments with multiple rings (usually 2–4) from one animal were averaged and used in subsequent analyses. Numbers (n) refer to the numbers of animals used for each protocol. Results are expressed as means±s.e. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was used to compare the effects of indomethacin, ASA and ketoprofen on relaxation to the agonists. The dose producing 50% maximal relaxation (EC50) was used to assess a parallel shift in the log dose–response curve. Planned comparisons were made using t-test for unpaired data. Rejection level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Effect of NSAIDs on vasodilation in intact aortic rings

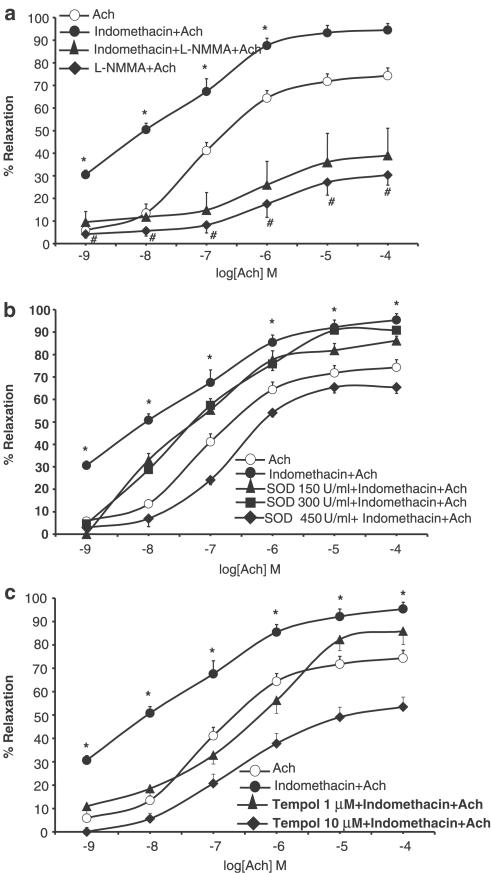

The isolated aortic rings contracted with 0.1 μM NE produced 1.90±0.12 g of tension. Ach (1 nM–0.1 mM) induced concentration-dependent vasorelaxation. Exposure of ring segments to indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) significantly increased Ach-induced vasodilation (P<0.05 for all doses; n=12), thereby causing the EC50 to decrease from 8.99 μM to 16 nM (Figure 1a). As shown in Figure 1b and c, concentration–response curves to SNP (0.1 nM–0.1 μM) and cromakalim (1 nM–0.1 mM) were not affected by pretreatment with indomethacin (EC50 1.11 and 1.84 nM for SNP (alone) and for SNP plus indomethacin, respectively; EC50 0.62 and 1.04 μM for cromakalim (alone) and for cromakalim plus indomethacin, respectively). Neither ASA (5−100 μM) nor ketoprofen (1−100 μM) modified Ach (Figure 2), SNP or cromakalim concentration–response curves (data not shown). Treatment of aortic rings for 15 min with 0.1 mM L-NMMA, an NOS inhibitor, substantially shifted Ach concentration–response curves to the right and blunted Ach-induced maximal relaxation by 60%. There were no differences between rings incubated or not with indomethacin (Figure 3a), which shows that the facilitating effect of indomethacin on Ach-induced vasodilation was reversed by L-NMMA. Moreover, pretreatment (20 min before indomethacin) with SOD or the free radical scavenger Tempol concentration-dependently reverted the potentiating effect of indomethacin on Ach-induced vasodilation. At higher concentrations, both scavengers slightly reduced the Ach-induced relaxation of aortic rings (Figure 3b, c).

Figure 1.

Concentration–response curves to (a) Ach (1 nM–0.1 mM; n=12), (b) SNP (0.1 nM–0.1 μM; n=8) and (c) cromakalim (1 nM–0.1 mM; n=8) on NE-contracted aortic rings from WKY rats in control conditions and after pretreatment with indomethacin (20 min; 10 μM). *P<0.05 versus all doses of Ach alone.

Figure 2.

Concentration–response curves to Ach (1 nM–0.1 mM)) on NE-contracted aortic rings from WKY rats in control condition and after pre-treatment with (a) ASA (5–100 μM; 15 min; n=16)) or (b) ketoprofen (1−100 μM; 15 min; n=18).

Figure 3.

Concentration–response curves to Ach (1 nM–0.1 mM) on NE-contracted aortic rings from WKY rats (n=12) (a) in control condition, with L-NMMA, 0.1 mM; 15 min), after pretreatment with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) alone and with L-NMMA Effects of SOD (150–450 U ml−1) (b) and Tempol (1–10 μM) (c) on Ach-induced vasodilation in the presence or absence of indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min). #P<0.05 L-NMMA+Ach versus Ach alone; *P<0.05 indomethacin+Ach versus indomethacin+L-NMMA+Ach.

NO concentration

Figure 4 depicts representative fluorescence microscopic images of NO-induced DAF-2 green fluorescence in endothelial cells from rat aorta. DAF-2 green fluorescence was localized mainly in endothelial cells, but spread to the underlying smooth muscle layers, according to the diffusion profile of NO in vessels. Incubation of aorta with Ach (30 min; 1 μM) produced a rapid and marked increase in NO fluorescence (Figure 4a; P<0.05 Ach versus basal condition; n=8). In the presence of indomethacin (20 min; 10 μM), Ach did not elicit a further increase in NO (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

NO production in aortic rings from WKY rats (n=4), as assessed by DAF-2 fluorescence, under basal condition (a), after stimulation with 1 μM Ach alone (b) and after pretreatment with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) (c). Quantification of DAF-2 fluorescence (d). *P<0.05 versus control.

Intracellular O2− concentration

DHE

To verify the role of O2− in indomethacin-induced vasodilation, we measured O2− production in rat aorta, with DHE. DHE is a fluorescent dye that specifically reacts with intracellular O2− and is converted to the red fluorescent compound ethidium. Ethidium then binds irreversibly to double-stranded DNA and appears as punctate nuclear staining. Figure 5 shows the images of O2−-induced red fluorescence in endothelial cells. Incubation of aorta with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) significantly increased O2− fluorescence (Figure 5c) compared with control conditions (Figure 5a) and with Ach alone (Figure 5b) (P<0.05 indomethacin versus basal condition; n=8; P<0.05 indomethacin versus Ach alone; n=6). Neither ASA nor ketoprofen affected O2− fluorescence (data not shown).

Figure 5.

O2− production in aortic rings from WKY rats (n=4), as assessed by DHE fluorescence, under basal conditions (a), after stimulation with 1 μM Ach alone (b) and after pretreatment with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) (c). Quantification of DHE fluorescence (d). P<0.05 versus basal condition and after stimulation with Ach.

Nitrotyrosine

Immunofluorescence analysis showed low nitrotyrosine staining in aorta segments treated with Ach alone (Figure 6b). Nitrotyrosine staining increased only when indomethacin was added to the segments (Figure 6c; P<0.05. indomethacin versus basal condition and versus Ach alone; n=8). Neither ASA nor ketoprofen affected nitrotyrosine staining (data not shown). Nitrotyrosine staining, which reflects the endogenous formation of ONOO−, confirmed the results obtained with DHE.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent detection of nitrotyrosine production in aortic rings from WKY rats (n=4), under basal condition (a), after stimulation with 1 μM Ach alone (b) and after pre-treatment with indomethacin (10 μM; 20 min) (c). Quantification of immunofluorescence (d). P<0.05 versus basal condition and after stimulation with Ach.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that indomethacin increases Ach-induced vasodilation of isolated aortic rings of rat. This process does not involve cyclooxygenase (COX)-inhibition because, under the same experimental conditions, neither ASA nor ketoprofen modified aortic vasodilation induced by Ach. It has been suggested that the effect of indomethacin on Ach-induced vasodilatation in SH, and to some extent in WKY, rat aorta depends on the inhibition of synthesis of vasoconstrictive COX products such as PGH2 and TXA2 (Ulker et al., 2003). This may be the case in SHR aorta where it is highly probable that COX-2 enzymes are activated. Our findings obtained in adult WKY rats are not consistent with this hypothesis, because ASA and ketoprofen did not potentiate Ach-induced relaxation at any of the concentrations used. Moreover, no COX-2 expression has been reported in adult WKY rats in the absence of inflammatory stimuli. Vasodilation induced by the endothelium-independent vasodilators SNP and cromakalim was not affected by indomethacin, ASA or ketoprofen. L-NMMA, an NOS inhibitor, reverted the increased vasodilation induced by indomethacin in isolated aortic rings. Pretreatment with SOD or Tempol also abolished the indomethacin-induced increase of Ach-induced vasodilation. In the endothelium of freshly dissected aorta, Ach-induced NO production, measured with DAF fluorescence microscopy, was not further augmented by indomethacin pretreatment. These observations indicate that indomethacin-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation does not result from increased NO concentration in the endothelium. According to our hypothesis, the augmented response to Ach-induced vasodilatation due to indomethacin is the consequence of an increased production of ONOO−s (formed from the interaction between ROS and NO). In vessels, NO is released mainly from the endothelium and spreads to the smooth muscle, so determining vasorelaxation. Therefore, the vascular endothelium is crucial for NO synthesis and for the regulation of NOS activity, although myocytes and neutrophils also produce NO. Endothelial cells also generate O2− when stimulated by cytokines, ischemia–reperfusion and hypoxia–reoxygenation, and in such diseases as hypertension (Ronson et al., 1999). We hypothesized that indomethacin causes vasodilation by stimulating O2− production in the vascular endothelium. In fact, DHE fluorescence microscopy showed that indomethacin significantly increased O2− content in the vascular endothelium of thoracic aorta, whereas neither ASA nor ketoprofen affected O2– concentration. This finding confirms the functional data obtained with the free radical scavengers SOD and Tempol.

Increased nitrotyrosine staining of indomethacin-treated aorta sections indicates that O2− overproduction is concomitant with NO formation thereby leading to ONOO− synthesis. NO is the only biological molecule known to be produced in sufficient amounts to react fast enough with O2– to outcompete endogenous SOD (Beckman & Koppenol, 1996; Beckman, 1996). ONOO− is a physiologically active toxic metabolite of NO that leads to vascular and myocardial dysfunction. The physiological consequences of ONOO− generated by the biradical interaction between NO and O2− as regards the vasculature are multiple, that is, a decrease in the amount of NO available for G-protein stimulation and for antineutrophil effects, and O2– neutralization, thereby limiting endothelial and vascular smooth muscle injury. The net outcome of these often opposing effects depends on the concentration of ONOO− in the compartment of interest (Ronson et al., 1999). ONOO− may have beneficial properties under in vivo physiological conditions when thiol-containing agents (glutathione, albumin and cysteine) are available to convert the ONOO− anion to S-nitrosothiols and related products that can be used by tissue (Zhang et al., 1997). The resulting thiol intermediates may subsequently regenerate NO; both nitrosothiols and NO are able to exert physiological effects consistent with NO-mediated stimulation of guanylate cyclase (i.e. vasodilation) and attenuation of neutrophil functions (i.e. reduced adherence to stimulated endothelium) (Ronson et al., 1999). Moreover, under physiological conditions, ONOO− exerts prolonged vasorelaxation in dog coronary artery, bovine pulmonary artery, rabbit aorta and in the anesthetized rat (Liu et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1994; Moro et al., 1995; Kooy et al., 1997). Thus, ONOO− reactivity in biological systems appears to be such that it may lead to the formation of compounds able to generate NO (Guzik et al., 2002). However, persistent production of oxidants, including ONOO−, may cause depletion of thiols. This, in turn, would leave tissues unprotected from the effects of ONOO−, which would lead to oxidative injury and impairment of physiological function. Indeed, in isolated perfused rat heart, ONOO− caused NO-mediated vasodilation, but repeated exposure to ONOO− caused vascular dysfunction and inhibition of relaxation to other vasodilator compounds (Villa et al., 1994). In conclusion, we suggest that indomethacin increases Ach-induced vasodilation causing an increase of reactive oxygen species and in particular of ONOO−. This study provides evidence that indomethacin may act on the cardiovascular system independently of COX inhibition. It is still unclear if the indomethacin-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation could damage or protect the cardiovascular apparatus.

Abbreviations

- Ach

acetylcholine

- ASA

acetylsalicylic acid

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DAF-2

diaminofluorescein

- DAF-2 DA

4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate

- DAF-2T

triazole form of diaminofluorescein-2

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- L-NMMA

N-monomethyl-L-arginine

- NE

norepinephrine

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NSAIDs

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- O2−

superoxide anion

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- ROD

relative optical density

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- Tempol

4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl

- TRITC

tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate

- WKY rats

Wistar–Kyoto rats

References

- BECKMAN J.S. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996;9:836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKMAN J.S, KOPPENOL W.H. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–C1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRY C., BROSNAN M.J., FENNELL J., HAMILTON C.A., DOMINICZAK A.F. Oxidative stress and vascular damage in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2001;10:247–255. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVILACQUA M., VAGO T., BALDI G., RENESTO E., DALLEGRI F., NORBIATO G. Nimesulide decreases superoxide production by inhibiting phosphodiesterase type IV. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;268:415–423. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS G., YU X.M., WANG Y., CRABBE M.J., SHATTOCK M.J., HARPER J.V. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via differential effects on the cell cycle. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003;55:519–526. doi: 10.1211/002235702775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAI H., HARRISON D.G. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ. Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTILHO R.F., WARD M.W., NICHOLLS D.G. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cell. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:1394–1401. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOBRUCKI L.W., KALINOWSKI L., URACZ W., MALINSKI T. The protective role of nitric oxide in the brain ischemia. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2000;51:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DROGE W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROSSER N., SCHRODER H. Aspirin protects endothelial cell from oxidant damage via the nitric oxide–cGMP pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:1345–1351. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000083296.57581.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYGLEWSKI R.J., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUZIK T.J., WEST N.E., PILLAI R., TAGGART D.P., CHANNON K.M. Nitric oxide modulates superoxide release and peroxynitrite formation in human blood vessels. Hypertension. 2002;39:1088–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000018041.48432.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOJIMA H., NAKATSUBO N., KIKUCHI K., KAWAHARA S., KIRINO Y., NAGOSHI H., NAGANO T. Detection and imaging of nitric oxide with novel fluorescent indicators: diaminofluoresceins. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:2446–2453. doi: 10.1021/ac9801723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOOY N.W., LEWIS S.J., ROYALL J.A., YE Y.Z., KELLY D.R., BECKMAN J.S. Extensive tyrosine nitration in human myocardial inflammation: evidence for the presence of peroxynitrite. Crit. Care Med. 1997;25:812–819. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199705000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU S., BECKMAN J.S., KU D.D. Peroxynitrite, a product of superoxide and nitric oxide, produces coronary vasorelaxation in dogs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:1114–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAFFEI FACINO R., CARINI M., ALDINI G. Antioxidant activity of nimesulide and its main metabolites. Drugs. 1993a;46:15–21. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199300461-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAFFEI FACINO R., CARINI M., ALDINI G., SAIBENE L., MACCIOCCHI A. Antioxidant profile of nimesulide, indomethacin and diclofenac in phosphatidylcholine liposomes (PCL) as membrane model. Int. J. Tissue React. 1993b;15:225–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., DARLEY-USMAR V.M., LIZASOAIN I., SU Y., KNOWLES R.G., RADO M.W., MONCADA S. The formation of nitric oxide donors from peroxynitrite. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:1999–2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOUITHYS-MICKALAD A.M., ZHENG S.X., DEBY-DUPONT G.P., DEBY C.M., LAMY M.M., REGINSTER J.Y., HENROTIN Y.E. In vitro study of the antioxidant properties of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by chemiluminescence and electron spin resonance (ESR) Free Radic. Res. 2000;33:607–621. doi: 10.1080/10715760000301131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGUOGHO A., SINZINGER H. Isoprostanes in atherosclerosis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2000;51:673–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RONSON R.S., NAKAMURA M., VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. The cardiovascular effects and implications of peroxynitrite. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;44:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SORESCU D., GRIENDLING K.K. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, and NAD(P)H oxidases in the development and progression of heart failure. Congest. Heart Fail. 2002;8:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SORESCU D., SZOCS K., GRIENDLING K.K. NAD(P)H oxidases and their relevance to atherosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2001;11:124–131. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ULKER S., McMASTER D., McKEOWN P.P., BAYRAKTUTAN U. Impaired activities of antioxidant enzymes elicit endothelial dysfunction in spontaneous hypertensive rats despite enhanced vascular nitric oxide generation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;59:488–500. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLA L.M., SALAS E., DARLEY-USMAR V.M., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. Peroxynitrite induces both vasodilation and impaired vascular relaxation in the isolated perfused rat heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12383–12387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARNHOLTZ A., MOLLNAU H., OELZE M., WENDT M., MUNZEL T. Antioxidants and endothelial dysfunction in hyperlipidemia. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2001;3:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11906-001-0081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLIN M.S., GUPTE S.A., OECKLER R.A. Superoxide in the vascular system. J. Vasc. Res. 2002;39:191–207. doi: 10.1159/000063685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU M., PRITCHARD K.A., JR, KAMINSKI P.M., FAYNGERSH R.P., HINTZE T.H., WOLIN M.S. Involvement of nitric oxide and nitrosothiols in relaxation of pulmonary arteries to peroxynitrite. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:H2108–H2113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.5.H2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG H., SQUADRITO G.L., UPPU R.M., LEMERCIER J.N., CUETO R., PRYOR V. Inhibition of peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation of glutathione by carbon dioxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997;339:183–189. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]