Abstract

We recently provided evidence for a functional link between cannabinoid and opioid endogenous systems in relapse to heroin-seeking behaviour in rats. In the present study, we aimed at investigating whether the previously observed cross-talk between cannabinoids and opioids could be extended to mechanisms underlying relapse to cannabinoid-seeking behaviour after a prolonged period of abstinence.

In rats previously trained to intravenously self-administer the synthetic cannabinoid receptor (CB1) agonist WIN 55,212-2 (12.5 μg kg−1 inf−1) under a fixed ratio (FR1) schedule of reinforcement, noncontingent nonreinforced intraperitoneal (i.p.) priming injections of the previously self-administered CB1 agonist (0.25 and 0.5 mg kg−1) as well as heroin (0.5 mg kg−1), but not cocaine (10 mg kg−1), effectively reinstate cannabinoid-seeking behaviour following 3 weeks of extinction.

The selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A (0.3 mg kg−1 i.p.) does not reinstate responding when given alone, but completely prevents the cannabinoid-seeking behaviour triggered by WIN 55,212-2 or heroin primings.

The nonselective opioid antagonist naloxone (1 mg kg−1 i.p.) has no effect on operant behaviour per sè, but significantly blocks cannabinoid- and heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour.

These results provide the first evidence of drug-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour, and further strengthen previous findings on a cross-talk between the endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems in relapse mechanisms to drug-seeking.

Keywords: CB1 cannabinoid receptor; opioid; cocaine; drug-seeking; extinction; reinstatement; WIN 55,212-2; heroin; naloxone; SR 141716A

Introduction

In human addicts, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the persistence of drug craving are largely unknown. The high rate of relapse to drug use is the most difficult problem in the treatment of human drug addiction after periods of abstinence (Hunt et al., 1971; O'Brien, 1997).

Suitable animal models of relapse to drug-taking and drug-seeking, the extinction/reinstatement procedures, are currently used in many laboratories to investigate mechanisms underlying drug-, stress- or cue-induced craving and relapse (Stewart & De Wit, 1987; Markou et al., 1993; Lu et al., 2003; Shaham et al., 2003). Drug-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour refers to the resumption of a previous drug-reinforced behaviour by noncontingent exposure to the same or different drug after a period of extinction (De Wit & Stewart, 1981).

To date, very few studies have investigated the involvement of the endocannabinoid system in relapse to drug-seeking behaviour (Schenk & Partridge, 1999; De Vries et al., 2001; 2003; Fattore et al., 2003). Notably, all these studies refer to a possible cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine- (Schenk & Partridge, 1999; De Vries et al., 2001) or heroin-seeking (De Vries et al., 2003; Fattore et al., 2003), although no study to date has investigated on the pharmacological or environmental factors triggering relapse to cannabinoid-seeking behaviour.

The present study was designed to assess whether cannabinoid-seeking behaviour could be resumed by priming injections of the same previously self-administered drug, as already reported for cocaine-, heroin- or nicotine-seeking behaviour (De Wit & Stewart, 1981; 1983; Jaffe et al., 1989; Shaham et al., 1996; Chiamulera et al., 1996). To this purpose, we used the previously described cannabinoid intravenous self-administration (IVSA) model (Fattore et al., 2001), in which Long Evans rats were trained to self-administer the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 under a continuous reinforcement schedule with nose-poking as operandum. Once a stable level of cannabinoid intake was reached, trained rats underwent a long-term extinction before reinstatement test primings were performed, according to the ‘between-session' protocol previously used in our laboratory in studying relapse to heroin-seeking (Fattore et al., 2003).

In addition, heroin and cocaine were also tested for their ability to resume cannabinoid-seeking behaviour in the rat following prolonged drug abstinence.

A growing body of evidence supports the existence of functional neuronal links between opioids and cannabinoids in the mutual modulation of rewarding and addictive effects (Ledent et al., 1999; Manzanares et al., 1999; Mascia et al., 1999; Rubino et al., 2000; Cossu et al., 2001; Solinas et al., 2004). For example, the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A alters heroin IVSA in rats (Navarro et al., 2001; Solinas et al., 2003), while naloxone reduces cannabinoid IVSA behaviour in mice (Fratta et al., 1999; Navarro et al., 2001; Fattore et al., 2000; 2002).

Recently, we reported that CB1 receptor agonists WIN 55,212-2 and CP 55,940 reliably reinstate heroin-seeking following a prolonged withdrawal period (Fattore et al., 2003). Intriguingly, the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A significantly attenuates heroin-induced relapse to drug-seeking, suggesting its potential role in the treatment of opioid addiction. To better define the possible interaction between cannabinoids and opioids in the reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour, noncontingent priming injections with the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A or naloxone were also tested.

Specifically, we determined whether (i) heroin priming would trigger nonreinforced drug-seeking behaviour in animals trained to self-administer WIN 55,212-2 following long-term (3 weeks) extinction; (ii) the CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A, as well as the nonselective opioid receptor antagonist naloxone, either alone or (iii) in combination with heroin and WIN 55,212-2 primings, would affect cannabinoid-seeking behaviour.

Finally, evidence points to the existence of functional interactions between the endocannabinoid and dopamine (DA) systems. Indeed, Δ9-THC self-administration in monkeys is markedly facilitated after previous acquisition of cocaine IVSA (Tanda et al., 2000), whereas cocaine treatment causes a decrease in the content of 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol in the limbic forebrain (Gonzalez et al., 2002a) as well as in CB1 receptor mRNA levels in several brain areas (Gonzalez et al., 2002b). Very recently, cocaine has also been reported to increase anandamide level in the striatum (Centonze et al., 2004), a brain region crucially involved in drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviour. With regard to a functional interaction between cannabinoid and DA systems in relapse mechanisms, it has been reported that CB1 receptor stimulation by HU210 is able to reinstate cocaine-seeking behaviour after prolonged drug abstinence, an effect significantly attenuated by SR 141716A (De Vries et al., 2001).

On the basis of this latter evidence, we decided to verify the bidirectionality of such interaction by testing the effect of cocaine on the resumption of extinguished cannabinoid-seeking behaviour.

Methods

The following experiments were conducted in strict accordance with both the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH) and the EC regulations for animal use in research (86/609/EEC).

Animals

Male Long Evans rats (Harlan Nossan, Italy) weighing 280–300 g at the beginning of the experiments were used. Animals were kept under standard conditions (temperature 20–21°C, 60–65% relative humidity) and reversed 12–12 h light/dark cycle (light on 19:00 h). On arrival, rats were housed four/cage with free access to food and water and handled once daily for approximately 10 min for 6–7 days.

Drugs

For IVSA training, WIN 55,212-2 (Tocris, Italy) was dissolved in one drop of Tween 80 and diluted in heparinized (1%) sterile saline solution, in a volume of injection of 100 μl. In order to ensure sterility, drug solution was filtered through 22 μm syringe filters prior to use.

For reinstatement tests (i.e. drug primings), WIN 55,212-2 and SR 141716A (Sanofi, Montpellier, France) were dissolved in Tween 80, diluted with sterile saline and administered i.p. at a volume of 0.5 ml kg−1. WIN 55,212-2 was given immediately prior to the start of the reinstatement test session, while SR 141716A was injected 20 min before. Heroin-HCl, naloxone and cocaine-HCl (Sigma, Italy) were dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and injected i.p. at a volume of 0.5 ml kg−1 10 min before starting the session.

Apparatus

The intravenous (i.v.) self-administration apparatus (Ecos, Italy) consisted of six Plexiglas cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm3). Two holes, equipped with fotobeam detectors, were made 2 cm above the floor, at a distance of 15 cm apart. During the experimental session, an infusion pump was connected with a length of plastic tubing to a swivel system, which was in turn connected via a silastic tube to the catheter. Nose-poking in one of the holes (defined as active) switched on the infusion pump, injecting the drug solution into the animal's venous system. Nose-poking in the other hole, defined as inactive, had no programmed consequences.

The assignment of the active (drug-paired) and the inactive (no drug-paired) holes were counterbalanced between rats and remained constant for each subject throughout the study. Assessment of the self-administration schedule and data collection were controlled by a PC software.

Surgery

Under deep anaesthesia with Equithesin (0.97 g pentobarbital, 2.1 g Mg-sulphate, 4.25 g chloral-hydrate, 42.8 ml propylene glycol, 11.5 ml ethanol 90%; 0.5 ml kg−1 i.p.), a permanent catheter was surgically implanted into the right jugular vein as previously described by Weeks (1972). After surgery, each rat was housed individually and recovered for 7 days under subcutaneous (s.c.) antibiotic treatment (0.1 ml Baytrill, Bayer). Once recovered from surgery, animals were kept on restricted food (20 g of rat chow per day, given in the home cage at the end of the session) and self-administration training was started. All antibiotics and anaesthetics were purchased as sterile solutions from local distributors.

Experimental procedure

The IVSA procedure was conducted as described previously (Fattore et al., 2001), with animals trained to self-administer WIN 55,212-2 (12.5 μg kg−1 inf−1) under a continuous (FR1) schedule of reinforcement for 3 h daily sessions. Responding on the active hole resulted in an infusion (100 μl) of the cannabinoid agonist over a period of 5 s.

Concurrently with each active nose-poke, a green light cue above the hole was turned on for 5 s. A 10-s timeout period immediately following each infusion was introduced, during which the green light was turned off and further nose-poking was recorded but had no consequences. IVSA sessions occurred once daily Monday–Saturday at the same time during the dark phase of the cycle (between 9:00 and 13:00). Catheters were flushed daily after each IVSA session with a sterile saline solution containing heparin (1%) to ensure catheter patency.

As rats acquired a stable responding for the cannabinoid (i.e. at least 3 consecutive days of stable responding with ±10% variation), training sessions were continued for 6–7 days before extinguishing drug-reinforced behaviour by replacing the drug solution with saline. Extinction sessions were conducted daily for 3 consecutive weeks. On alternate days during the last week of extinction, rats received three injections of saline (0.5 ml kg−1 i.p.) to habituate them to subsequent drug-priming administrations.

Rats were then tested for reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking induced by one of the following (i.p.) primings: WIN 55,212-2 (0.25 and 0.5 mg kg−1), heroin (0.5 mg kg−1), cocaine (10 mg kg−1), SR 141716A (0.3 mg kg−1), SR 141716A+WIN 55,212-2, SR 141716A+heroin, naloxone (1 mg kg−1), naloxone+heroin or naloxone+WIN 55,212-2.

Drug treatments were counterbalanced among animals, with a 3-day extinction period separating each priming; however, no more than three reinstatement test sessions per animal were conducted. As a control study, one group of six rats was primed with saline and an additional one with the same vehicle of cannabinoids (0.5 ml kg−1). Each treatment group included a minimum of six animals.

Responding patterns during each reinstatement test session were analysed quantitatively using the following measures: (1) mean cumulative number of nose-pokes on both the active and inactive holes; (2) mean latency to the first nose-poke on the active hole, i.e. mean time to initiate active responding; (3) individual temporal pattern of responding during the different phases (i.e. training, extinction, reinstatement tests) of the study.

Statistical analysis

Due to catheter blockade or leakage, not all animals completed the entire set of experiments, and data were therefore computed as for independent rather than correlated samples. All measures were analysed with two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with drug primings as the between-group factor and the experimental phases (training:extinction:priming) as repeated within-subject measure. Moreover, within each drug treatment group, data from the three experimental phases were compared and analysed by means of one-way ANOVA. Upon confirmation of significant main effect, differences among individual means were analysed using Newman–Keuls and Bonferroni post hoc tests, following one-way and two-way ANOVA, respectively. The total number of responses in the inactive hole as well as responses during timeout period over each test session were not included in the analysis since they were no longer present once a stable drug intake had been achieved (i.e. after the acquisition period). Significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

WIN 55,212-2 and heroin, but not cocaine, reinstate cannabinoid-seeking behaviour following prolonged extinction

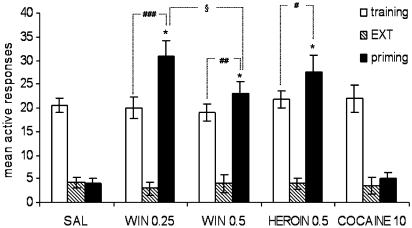

As illustrated in Figure 1, a priming with saline or cocaine did not induce reinstatement of operant responding, while re-exposure to the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 or heroin significantly reinstated extinguished drug-seeking behaviour in the previously cannabinoid-paired (active) hole following long-term extinction. Interestingly, both heroin and cannabinoid reinstated responding for cannabinoid at a level which was significantly higher than the respective pre-extinction (training) baseline. ANOVA revealed a drug × phase significant interaction (F(8,102)=35.68, P<0.0001), with an overall significant effect of phases (F(8,102)=35.68) as well as drug treatments (F(4,102)=31.11).

Figure 1.

Effect of acute primings of WIN 55,212-2, heroin and cocaine on the reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour following prolonged abstinence. Each bar represents the mean±s.e.m. of active nose-pokes over the last 3 days of cannabinoid IVSA (training), over the last five consecutive sessions of extinction (EXT) and during the reinstatement test sessions (priming). Doses are expressed as mg kg−1 (i.p.). *P<0.001 vs respective EXT; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs respective training; §P<0.05 between primings of the two doses of WIN 55,212-2. ANOVA followed by post hoc test (n=7–8).

Indeed, a stronger level of responding was reinstated by the lowest dose of WIN 55,212-2 tested (0.25 mg kg−1), which significantly (P<0.001) increased the active nose-poking rate (+55%) with respect to the pre-extinction baseline rate (F(2,14)=84.13), while the higher dose of the CB1 receptor agonist (0.5 mg kg−1) had a lower, but still significant, effect (F(2,14)=121.9, P<0.01). Moreover, planned comparisons showed a dose-dependent effect of WIN 55,212-2 primings, the reinstated levels of responding by the two cannabinoid doses being statistically different (F(1,42)=5.94, P=0.0192). The previously reported doses of WIN 55,212-2 were selected for the present study following a wide screening test of drug doses (0.0125 up to 1.0 mg kg−1) and administration routes (i.v., i.p. or s.c.), whereby they proved to be the only doses capable of producing a significant reinstatement of responding (data not shown).

As illustrated in Figure 1, an acute priming injection of heroin also triggered relapse to cannabinoid-seeking behaviour, reinstating active responding at a rate which was significantly (P<0.05) higher than the respective pre-extinction baseline (F(2,14)=73.18). The i.p. route of drug administration was found to produce the most robust reinstatement of responding in cannabinoid-trained rats, i.v. heroin primings (ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mg kg−1) being less effective in this respect, at least under our experimental conditions (data not shown). On the other hand, a priming injection of cocaine had no effect on responding (Figure 1) and no difference was observed with respect to the aftermath of a priming with saline, indicating that cocaine was not able to reinstate cannabinoid-seeking behaviour after prolonged abstinence (F(2,14)=199.3, NS). The dose of cocaine (10 mg kg−1) was chosen due to its behavioural activity in reinstating cocaine-seeking behaviour following long-term extinction (De Vries et al., 1998). As for saline, primings with cannabinoid vehicle had no effect at all on responding, and were therefore excluded from the statistical analysis.

The absence of modifications in the number of inactive nose-pokes during the reinstatement test sessions (data not shown) indicates that rats maintained a good discrimination between the active and inactive holes, thus dispelling all doubts as to a possible nonspecific effect of drug priming injections (i.e. generalization).

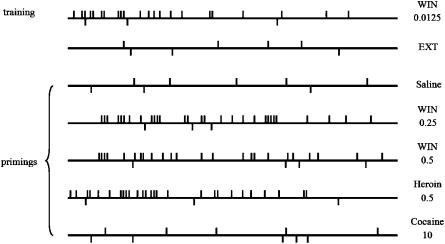

A closer examination of the response pattern of individual rats better highlighted the differences in the resumption of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour following the different drug primings. In Figure 2, the first record refers to the pre-extinction training phase (i.e. last day of WIN 55,212-2 self-administration), during which the mean nose-poking activity on the active hole was rated at 20.66±2.25, while during extinction (second record, day before priming test) the mean active responding was 3.8±1.25.

Figure 2.

Event records from representative rats during training, extinction and reinstatement test sessions. The vertical deflections above the horizontal line mark the exact time of each individual nose-poke on the active hole, while each deflection below the line represents a response on the inactive hole over the 3 h experimental session. Training refers to the last day of WIN 55,212-2 self-administration before extinction, EXT refers to the last day of extinction before priming tests, while the following patterns refer to the reinstatement test sessions following saline (0.5 ml kg−1) or drug primings (i.p.). On the right are indicated each drug priming; doses are expressed as mg kg−1.

Subsequently, the individual response patterns displayed during the different reinstatement test sessions following drug primings are illustrated. It can be noted that, when primed with saline, rats made only few nose-pokes on either the active or inactive hole. On the contrary, following acute priming with both 0.25 and 0.5 mg kg−1 of WIN 55,212-2, rats exhibited consistent and somewhat regular response patterns, with maximal responding occurring within 90–120 min following drug-priming injection.

Cannabinoid-related temporal patterns appeared to differ from those exhibited by the same animals during the previous phase of cannabinoid intake (i.e. training), showing a marked delay in the onset of responding and a persistence over time (i.e. responding is present until the end of the session).

Interestingly, a typical responding pattern of heroin-primed rat was quite different from those displayed by cannabinoid-primed animals, regardless of the similarity in the cumulative mean number of total active responses (27.5±3.6 vs 31±3.1 and 23±2.5 for WIN 0.25 and WIN 0.5 mg kg−1, respectively). Indeed, heroin priming-induced effect was of earlier onset but of shorter duration, the responding activity being clearly higher at the beginning of the session, especially during the first hour, becoming gradually less frequent over the remaining time. However, all cannabinoid- and heroin-primed groups displayed a very low number of responses on the inactive hole (constantly ⩽4) throughout all the experiments, indicating that the operant behaviour of animals was specifically oriented towards the previously drug-associated hole.

Following cocaine priming, animals exhibited only slow and temporally sporadic responding with prolonged inter-response intervals: the mean number of responses on both the active and inactive holes was very low and did not exceed five/session.

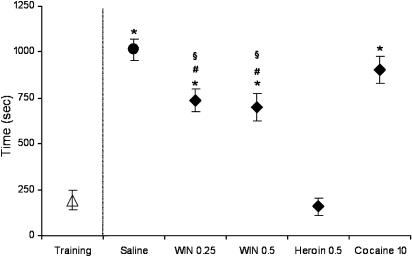

As shown in Figure 3, analysis of the mean latencies to the first nose-poke on the active hole revealed that cannabinoid- and heroin-primed groups were different in the onset of reinstated responding (F(4,35)=39.26, P<0.0001). Indeed, while saline- or cocaine-primed rats took a mean of 1012 and 905 s to initiate responding, cannabinoid-primed rats showed a mean latency to the first active nose-poke consistently longer than heroin-primed animals (158±44.5 for heroin vs 737±59.7 and 699.8±44.3 for WIN 0.25 and WIN 0.5 mg kg−1, respectively), despite the similarity in the reinstated responding level.

Figure 3.

Latency to the first nose-poke on the active hole following primings with saline (circle) or drugs (diamonds). Data are expressed as the mean time (s) taken to make the first active nose-poke during the pre-extinction baseline (i.e. training, open triangle) and the reinstatement test session (filled symbols) following extinction. *P<0.001 vs heroin, #P<0.01 vs saline, §P<0.05 vs cocaine. One-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test (n=7–8).

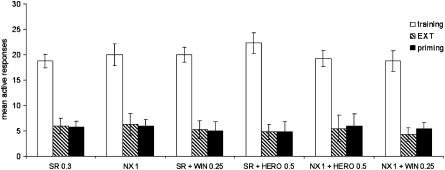

SR 141716A and naloxone prevent heroin- and cannabinoid-triggered reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour

Figure 4 shows that given alone the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR 141716A had no effect on relapse to cannabinoid-seeking, since it produced no modification to animal responding respect to previous extinction baseline. Indeed, ANOVA revealed an overall main effect of phases (F(2,114)=1228.77, P<0.0001) but not drug treatments (F(5,114)=1.06, NS). The dose of SR 141716A (0.3 mg kg−1) was chosen due to its ability to reverse behavioural effects induced by both CB1 receptor agonists and heroin while not affecting cannabinoid-taking per sè (Navarro et al., 2001; Fattore et al., 2003).

Figure 4.

Antagonism by SR 141716A (SR) and naloxone (NX) of WIN 55,212-2- and heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour. Each bar represents the mean±s.e.m. of active nose-pokes observed over the last 3 days of cannabinoid IVSA (training), over the last five consecutive sessions of extinction (EXT) and during the reinstatement test sessions (drug priming). Doses are expressed as mg kg−1 (i.p.). Effect of phases: P<0.0001; effect of treatment: P=NS (two-way ANOVA).

However, pretreatment with SR 141716A completely prevented WIN 55,212-2-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour, so that responding rate following cannabinoid primings was no higher than during extinction (5±1.8 vs 5.3±1.41). More notably, SR 141716A abolished heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking, producing no differences in nose-poking activity between the reinstatement test session and the previous extinction baseline (4.8±2.1 vs 4.8±1.5).

Similarly, the opioid antagonist naloxone (1 mg kg−1 i.p.) did not reinstate responding per sè, but it completely blocked heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour, the mean responding rate during the reinstatement sessions being no different from that observed during extinction (6±2.4 vs 5.5±2.53). More importantly, also WIN 55,212-2-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour was fully prevented by pretreatment with the opioid antagonist (5.5±1.10 vs 4.3±1.3).

During all reinstatement test sessions, the mean number of responses on the inactive hole never exceeded five per session.

Discussion

The present study assesses the first extinction/reinstatement model of cannabinoid-seeking in the rat and provides evidence for a role of the endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems in the resumption of nonreinforced cannabinoid-seeking behaviour following long-term extinction.

We demonstrated that a single noncontingent nonreinforced priming injection of WIN 55,212-2, at doses not affecting temporal parameters of operant responding (Carriero et al., 1998), reliably reinstated extinguished operant responding for cannabinoid in the rat. This finding is in agreement with observations from other investigators reporting that relapse to cocaine-, heroin- or nicotine-seeking behaviour is triggered by the same previously self-administered drug (De Wit & Stewart, 1981; 1983; Jaffe et al., 1989; Chiamulera et al., 1996; Shaham et al., 1996; De Vries et al., 1998), thus validating our extinction/reinstatement model of cannabinoid-seeking as a useful tool for investigating relapse to cannabinoids in the rat. In this study, we have tested WIN 55,212-2 at different doses (0.125–0.25–0.5–1 mg kg−1) and found a bell-shaped dose–response curve, with the doses of 0.125 and 1 mg kg−1 not effective in reinstating cannabinoid-seeking behaviour (data not shown). The finding that a 0.5 mg kg−1 dose of the CB1 receptor agonist induced a significantly weaker effect than the lowest dose of 0.25 mg kg−1 could be explained if the latter is taken as already being on the descending portion of the dose–response curve. Notably, a very similar dose-dependent decrease in responding was also observed during WIN 55,212-2 self-administration (Fattore et al., 2001). The ability of WIN 55,212-2 to reinstate extinguished responding is specifically mediated by CB1 receptors since resumption of cannabinoid-seeking by WIN 55,212-2 is completely reversed by SR 141716A, at a dose that did not modify baseline response rates per sè.

Remarkably, pretreatment with naloxone also prevents relapse to cannabinoid-seeking, strengthening the notion of a cross-interaction between opioid and cannabinoid systems in behavioural responses related to reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour (Fattore et al., 2003). Acute administration of naloxone has been previously reported to (i) block self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonists WIN 55,212-2 and HU210 in drug-naïve mice without being self-administered by animals (Navarro et al., 2001; Fattore et al., 2002), (ii) induce withdrawal syndrome in HU210-dependent animals (Navarro et al., 2001) and (iii) significantly reduce CP 55,940-induced conditioned place preference in rats (Braida et al., 2001).

In line with these observations is the finding that an acute heroin priming resumes extinguished cannabinoid-seeking behaviour, in an even quicker manner than WIN 55,212-2 primings, providing strong support for the bi-directionality of the cannabinoid–opioid interaction in relapse-related mechanisms.

The fact that the effect of heroin is completely reversed by pretreatment with naloxone, at a dose that did not affect operant response in animals per sè, implies that heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking is also mediated throughout opioid receptor stimulation. Importantly, when the effect of SR 141716A on the heroin-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking was evaluated, the compound proved to completely inhibit heroin-induced relapse to cannabinoid-seeking, thus suggesting that blockade of CB1 receptors may also reduce the reinforcing/motivational properties of heroin, as previously suggested (Navarro et al., 2001; De Vries et al., 2003; Fattore et al., 2003). Cannabinoid and opioid interactions have been proposed to enhance the propensity to heroin abuse in marijuana users; however, a very recent paper shows that Δ9-THC-tolerant rats were no more vulnerable than control animals to the reinforcing properties of morphine in a self-administration study (Gonzalez et al., 2004).

In view of the notion that one drug of abuse can reinstate extinguished responding established with another drug of abuse only when the two drugs share physiological and/or pharmacological consequences (De Wit & Stewart, 1981; 1983), the observation that cannabinoid and opioid agents produce cross-reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour following long-term withdrawal is quite remarkable. Indeed, priming injections of WIN 55,212-2 reinstate heroin-seeking behaviour (Fattore et al., 2003) as well as heroin primings result in relapse to cannabinoid-seeking behaviour (present findings).

Cross-tolerance or mutual potentiation has been demonstrated between cannabinoids and opioids, leading several authors to suggest that both drugs share common links in their molecular mechanisms of action (Rubino et al., 1997; Hampson et al., 2000; Shapira et al., 2000; Massi et al., 2003; Vigano et al., 2003).

CB1 cannabinoid and μ opioid receptors are co-expressed in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Navarro et al., 1998), and it has been suggested that cannabinoids and opioids may interact at the levels of their cellular (Shapira et al., 2003), intracellular (Fimiani et al., 1999) or signal transduction (Thorat & Bhargava, 1994; Manzanares et al., 1999) pathways. Such interactions could be involved, at least in part, in the central mechanisms modulating relapse to drug-seeking. However, two other possible considerations may be of help in explaining cannabinoid–opioid interactions in drug abuse and relapse. The first is the ability of cannabinoids to increase the synthesis and induce the release of endogenous opioids in brain areas critically involved in addiction and dependence (Manzanares et al., 1998; Valverde et al., 2001). This evidence suggests that the newly released endogenous opioids might act on opioid receptors in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and consequently enhance mesolimbic DA release (Tanda et al., 1997). Secondly, the co-localization of CB1 and opioid receptors has been demonstrated in GABAergic efferent neurons, implying that stimulation of either CB1 or opioid receptors inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission in the NAc (Hoffman & Lupica, 2001) while stimulation of both receptors could have a synergistic effect.

We also found that priming injections of cocaine does not reinstate cannabinoid–seeking behaviour following extended drug abstinence. This result was rather unexpected in light of the notion that endocannabinoid and DA systems exert a mutual control on signalling processes (Van der Stelt & Di Marzo, 2003). Similarly to other drugs of abuse, cannabinoids increase dopaminergic transmission in several limbic areas (Gardner et al., 1988; Navarro et al., 1993; Szabo et al., 1999; Van der Stelt & Di Marzo, 2003), while cannabinoid withdrawal reduces mesolimbic dopaminergic activity (Diana et al., 1998).

Previous evidence pointed to an interaction between cannabinoid and DA systems in the modulation of relapse to drug-seeking (De Vries et al., 2001) as well as in drug-taking (Fattore et al., 1999) and reward-facilitating (Vlachou et al., 2003; Duarte et al., 2004) mechanisms, although cocaine is spontaneously self-administered by CB1 knockout mice (Cossu et al., 2001). Moreover, studies on drug-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviour typically indicated the mesocorticolimbic DA system as an essential substrate for triggering relapse in the reinstatement paradigm, via the neural systems that it regulates, from the VTA to the NAc and, to a lesser extent, on its afferent and efferent projection areas such as medial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala and ventral pallidum (Grimm & See, 2000; Shalev et al., 2002).

However, the specific role of the dopaminergic system in relapse to cannabinoids or opioids has not yet been elucidated, so that it may be possible that the dopaminergic transmission is not the main neuronal system directly involved in the processes underlying reinstatement of cannabinoid- and heroin-seeking. Indeed, reinstatement of heroin-seeking behaviour has been reported following amphetamine (De Vries et al., 1998) but not apomorphine, bromocriptine or the D1 agonist SKF-82958 (De Vries et al., 1999; Wise et al., 2000) primings. Cocaine itself shows differential effects on relapse to heroin depending on drug doses and route of administration used (De Wit & Stewart, 1983; De Vries et al., 1998). Based on these observations, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that systems other than the dopaminergic one (i.e. the opioid system) may play a major role in relapse to cannabinoids, possibly via a more indirect central action.

Taken together, the evidence provided by the present study demonstrates that cannabinoid-seeking behaviour is reinstated by both WIN 55,212-2 and heroin-priming injections in trained rats following long-term extinction, thus demonstrating the bi-directionality of cannabinoid–opioid interactions in modulating central mechanisms underlying relapse.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from ‘Centre of Excellence on Neurobiology of Dependence' and the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR) FIRB 2001 and PRIN 2002. We are grateful to Mrs. Ann Farmer for language editing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CB1

type 1 cannabinoid receptor

- CP 55,940

(−)-cis-3-[2-hydroxy-4(1,1-dimethyl-heptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclo-hexanol

- DA

dopamine

- Δ9-THC

delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- HU210

3-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)-11-hydroxy-Δ8-tetrahydro-cannabinol

- IVSA

intravenous self-administration

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- SR 141716A

N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl) -4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carbox-amide hydro-chloride

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- WIN 55,212-2

R(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazinyl]-(1-naphthalenyl)-methanone mesylate

References

- BRAIDA D., POZZI M., CAVALLINI R., SALA M. Conditioned place preference induced by the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940: interaction with the opioid system. Neuroscience. 2001;104:923–926. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARRIERO D., ABERMAN J., LIN S.Y., HILL A., MAKRIYANNIS A., SALAMONE J.D. A detailed characterization of the effects of four cannabinoid agonists on operant lever pressing. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s002130050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENTONZE D., BATTISTA N., ROSSI S., MERCURI N.B., FINAZZI-AGRO A., BERNARDI G., CALABRESI P., MACCARRONE M.A critical interaction between dopamine D2 receptors and endocannabinoids mediates the effects of cocaine on striatal GABAergic transmission Neuropsychopharmacology 2004(Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- CHIAMULERA C., BORGO C., FALCHETTO S., VALERIO E., TESSARI M. Nicotine reinstatement of nicotine self-administration after long-term extinction. Psychopharmacology. 1996;127:102–107. doi: 10.1007/BF02805981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSSU G., LEDENT C., FATTORE L., IMPERATO A., BÖHME G.A., PARMENTIER M., FRATTA W. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;118:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VRIES T.J., HOMBERG J.R., BINNEKADE R., RAASO H., SCHOFFELMEER A.N. Cannabinoid modulation of the reinforcing and motivational properties of heroin and heroin-associated cues in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:164–169. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VRIES T.J., SCHOFFELMEER A.N., BINNEKADE R., MULDER A.H., VANDERSCHUREN L.J.M.J. Drug-induced reinstatement of heroin- and cocaine-seeking behaviour following long-term extinction is associated with expression of behavioural sensitization. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:3565–3571. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VRIES T.J., SCHOFFELMEER A.N., BINNEKADE R., VANDERSCHUREN L.J. Dopaminergic mechanisms mediating the incentive to seek cocaine and heroin following long-term withdrawal of IV drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 1999;143:254–260. doi: 10.1007/s002130050944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VRIES T.J., SHAHAM Y., HOMBERG J.R., CROMBAG H., SCHUURMAN K., DIEBEN J., VANDERSCHUREN L.J.M.J., SCHOFFELMEER A.N.M. A cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine seeking. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE WIT H., STEWART J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE WIT H., STEWART J. Drug-reinstatement of heroin-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1983;79:29–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00433012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIANA M., MELIS M., MUNTONI A.L., GESSA G.L. Mesolimbic dopaminergic decline after cannabinoid withdrawal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:10269–10273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUARTE C., ALONSO R., BICHET N., COHEN C., SOUBRIE P., THIEBOT M.H. Blockade by the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant (SR141716), of the potentiation by quinelorane of food-primed reinstatement of food-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:911–920. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATTORE L., COSSU G., FRATTA W. Functional interaction between cannabinoids and opioids in animal models of drug addiction 2002Orlando, FL, U.S.A; Proceedings of the ‘Frontiers in Addiction Research' NIDA syposium satellite at the SfN Meeting, 1–2 November 2002 [Google Scholar]

- FATTORE L., COSSU G., MARTELLOTTA M.C., FRATTA W. Intravenous self-administration of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:410–416. doi: 10.1007/s002130100734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATTORE L., COSSU G., MASCIA M.S., OBINU M.C., LEDENT C., PARMENTIER M., IMPERATO A., BÖHME G.A., FRATTA W. Role of cannabinoid CB1 receptor in morphine rewarding effects in mice. Pharm. Pharmacol. Commun. 2000;6:281–285. [Google Scholar]

- FATTORE L., MARTELLOTTA M.C., COSSU G., MASCIA M.S., FRATTA W. CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 decreases intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 1999;104:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATTORE L., SPANO M.S., COSSU G., DEIANA S., FRATTA W. Cannabinoid mechanism in reinstatement of heroin-seeking after a long period of abstinence in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:1723–1726. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIMIANI C., LIBERTY T., AQUIRRE A.J., AMIN I., ALI N., STEFANO G.B. Opiate, cannabinoid, and eicosanoid signalling converges on common intracellular pathways nitric oxide coupling. Prostagland. Other Lipid Mediat. 1999;57:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(98)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRATTA W., COSSU G., MARTELLOTTA M.C., FATTORE L. A common neurobiological mechanism regulates cannabinoid and opioid rewarding effects in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;52:S10–S11. [Google Scholar]

- GARDNER E.L., PAREDES W., SMITH D., DONNER A., MILLING C., COHEN D., MORRISON D. Facilitation of brain stimulation reward by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology. 1988;96:142–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02431546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ S., CASCIO M.G., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J., FEZZA F., DI MARZO V., RAMOS J.A. Changes in endocannabinoid contents in the brain of rats chronically exposed to nicotine, ethanol or cocaine. Brain Res. 2002a;954:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ S., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J., DI MARZO V., HERNANDEZ M., AREVALO C., NICANOR C., CASCIO M.G., AMBROSIO E., RAMOS J.A. Behavioral and molecular changes elicited by acute administration of SR141716 to Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol-tolerant rats: an experimental model of cannabinoid abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ S., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J., SPARPAGLIONE V., PAROLARO D., RAMOS J.A. Chronic exposure to morphine, cocaine or ethanol in rats produced different effects in brain cannabinoid CB(1) receptor binding and mRNA levels. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002b;66:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIMM J.W., SEE R.E. Dissociation of primary and secondary reward-relevant limbic nuclei in an animal model of relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMPSON R.E., MU J., DEADWYLER S.A. Cannabinoid and kappa opioid receptors reduce potassium K currents via activation of G(s) proteins in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2356–2364. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN A.F., LUPICA C.R. Direct actions of cannabinoids on synaptic transmission in the nucleus accumbens: a comparison with opioids. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;85:72–83. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNT W.A., BARNETT L.W., BRANCH L.G. Relapse rates in addiction programs. J. Clin. Psychol. 1971;27:455–456. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197110)27:4<455::aid-jclp2270270412>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAFFE J.H., CASCELLA N.G., KUMOR K.M., SHERER M.A. Cocaine-induced cocaine craving. Psychopharmacology. 1989;97:59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00443414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEDENT C., VALVERDE O., COSSU G., PETITET F., AUBERT J.F., BESLOT F., BÖHME G.A., IMPERATO A., PEDRAZZINI T., ROQUES B.P., VASSART G., FRATTA W., PARMENTIER M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU L., SHEPARD J.D., SCOTT HALL F., SHAHAM Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003;27:457–491. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZANARES J., CORCHERO J., ROMERO J., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J.J., RAMOS J.A., FUENTES J.A. Chronic administration of cannabinoids regulates proenkephalin mRNA levels in selected regions of the rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;55:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZANARES J., CORCHERO J., ROMERO J., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J.J., RAMOS J.A., FUENTES J.A. Pharmacological and biochemical interactions between opioids and cannabinoids. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKOU A., WEISS F., GOLD L.H., CAINE S.B., SCHULTEIS G., KOOB G.F. Animal models of drug craving. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:163–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02244907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASCIA M.S., OBINU M.C., LEDENT C., PARMENTIER M., BÖHME G., IMPERATO A., FRATTA W. Lack of morphine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;383:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSI P., VACCANI A., RUBINO T., PAROLARO D. Cannabinoids and opioids share cAMP pathway in rat splenocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2003;145:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAVARRO M., CARRERA M.R.A., FRATTA W., VALVERDE O., COSSU G., FATTORE L., CHOWEN J.A., GOMEZ R., DEL ARCO I., VILLANUA M.A., MALDONADO R., KOOB G.F., DE FONSECA F.R. Functional interaction between opioid and cannabinoid systems in drug self-administration. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5344–5350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05344.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAVARRO M., CHOWEN J., ROCIO A., CARRERA M., DEL ARCO I., VILLANUA M.A., MARTIN Y., ROBERTS A.J., KOOB G.F., DE FONSECA F.R. CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist-induced opiate withdrawal in morphine-dependent rats. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3397–3402. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810260-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAVARRO M., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J.J., DE MIGUEL R., HERNANDEZ M.L., CEBEIRA M., RAMOS J.A. An acute dose of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol affects behavioral and neurochemical indices of mesolimbic dopaminergic activity. Behav. Brain Res. 1993;57:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'BRIEN C.P. A range of research-based pharmacotherapies for addiction. Science. 1997;278:66–70. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBINO T., MASSI P., VIGANO D., FUZIO D., PAROLARO D. Long-term treatment with SR141716A, the CB1 receptor antagonist, influences morphine withdrawal syndrome. Life Sci. 2000;66:2213–2219. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBINO T., TIZZONI L., VIGANO D., MASSI P., PAROLARO D. Modulation of rat brain cannabinoid receptors after chronic morphine treatment. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3219–3223. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHENK S., PARTRIDGE B. Cocaine-seeking produced by experimenter-administered drug injections: dose–effect relationship in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;147:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s002130051169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAHAM Y., RAJABI H., STEWART J. Relapse to heroin-seeking in rats under opioid maintenance: the effects of stress, heroin priming, and withdrawal. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1957–1963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01957.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAHAM Y., SHALEV U., LU L., DE WIT H., STEWART J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHALEV U., GRIMM J.W., SHAHAM Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine-seeking: a review. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:1–52. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAPIRA M., GAFNI M., SARNE Y. Long-term interactions between opioid and cannabinoid agonists at the cellular level: cross-desensitization and downregulation. Brain Res. 2003;960:190–200. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAPIRA M., VOGEL Z., SARNE Y. Opioid and cannabinoid receptors share a common pool of GTP-binding proteins in cotransfected cells, but not in cells which endogenously coexpress the receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2000;20:291–304. doi: 10.1023/A:1007058008477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLINAS M., PANLILIO L.V., ANTONIOU K., PAPPAS L.A., GOLDBERG S.R. The cannabinoid CB1 antagonist N-piperidinyl-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methylpyrazole-3-carboxamide (SR-141716A) differentially alters the reinforcing effects of heroin under continuous reinforcement, fixed ratio, and progressive ratio schedules of drug self-administration in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;306:93–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLINAS M., PANLILIO L.V., GOLDBERG S.R.Exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) increases subsequent heroin taking but not heroin's reinforcing efficacy: a self-administration study in rats Neuropsychopharmacology 2004(Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- STEWART J., DE WIT H.Reinstatement of drug-taking behaviour as a method for assessing incentive motivational properties of drugs Methods of Assessing the Reinforcing Properties of Abused Drugs 1987New York: Springer-Verlag; 211–227.ed. Bozarth, M.A. pp [Google Scholar]

- SZABO B., MULLER T., KOCH H. Effects of cannabinoids on dopamine release in the corpus striatum and the nucleus accumbens in vitro. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:1084–1089. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANDA G., MUNZAR P., GOLDBERG S.R. Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:1073–1074. doi: 10.1038/80577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANDA G., PONTIERI F.E., DI CHIARA G. Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common mu1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science. 1997;276:2048–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORAT S.N., BHARGAVA H.N. Evidence for a bidirectional cross-tolerance morphine and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;260:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALVERDE O., NOBLE F., BESLOT F., DAUGE V., FOURNIE-ZALUSKI M.C., ROQUES B.P. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol releases and facilitates the effects of endogenous enkephalins: reduction in morphine withdrawal syndrome without change in rewarding effect. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:1816–1824. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER STELT M., DI MARZO V. The endocannabinoid system in the basal ganglia and in the mesolimbic reward system: implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;480:133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIGANO D., CASCIO G.M., RUBINO T., FEZZA F., VACCANI A., DI MARZO V., PAROLARO D. Chronic morphine modulates the contents of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol, in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VLACHOU S., NOMIKOS G.G., PANAGIS G. WIN 55,212-2 decreases the reinforcing actions of cocaine through CB1 cannabinoid receptor stimulation. Behav. Brain. Res. 2003;141:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEEKS J.R.Long-term intravenous infusion Methods in Psychobiology 1972London: Academic Press; 155–168.ed. Myers, R.D. pp [Google Scholar]

- WISE R.A., MURRAY A., BOZARTH M.A. Bromocriptine self-administration and bromocriptine-reinstatement of cocaine-trained and heroin-trained lever pressing in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2000;100:355–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02244606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]