Abstract

Systemic infusions of urocortin 1 produce a decrease in mean arterial pressure. This effect may be mediated by a direct action on novel corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 (CRF2) receptors predicted to be expressed in blood vessels and the heart. Our objectives were to determine the presence of CRF2 receptors in the human cardiovascular system using the selective radioligand [125I]antisauvagine 30. We also investigated the potential functional roles of novel CRF2 ligands in the regulation of vascular tone in human arteries in vitro.

Radioligand binding techniques were used to characterise the CRF2 receptor. [125I]antisauvagine 30 bound specifically, saturably, reversibly and with high affinity to CRF2 receptors in human left ventricle (KD 0.21±0.03 nM, BMAX 0.80±0.18 fmol mg−1 protein), and no change in receptor density or affinity was observed in the dilated cardiomyopathy group.

Autoradiographical studies revealed highly localised binding of [125I]antisauvagine 30 to intramyocardial blood vessels. Binding sites were also detected in the myocardium and in the medial layer of internal mammary arteries.

In endothelium-denuded human internal mammary artery in vitro, all peptides tested produced a potent and sustained vasodilator response reversing endothelin-1-induced constrictions (10 nM) (urocortin 1: pD2 8.39±0.32, EMAX 46±7.7%; urocortin 2: pD2 8.27±0.17, EMAX 60±8.5%; urocortin 3: pD2 8.61±0.25, EMAX 61±7.2%; CRF: pD2 8.28±0.27, EMAX: 40±10%).

We have demonstrated the presence of CRF2 receptors in the human cardiovascular system and a direct, endothelium-independent vasodilator action of urocortins 2 and 3, which may counter-balance the centrally mediated pressor effects of CRF and urocortin 1.

Keywords: Corticotropin-releasing factor, human ventricle, human internal mammary artery, peptides, urocortin, vasculature, vasodilatation

Introduction

Originally identified as a transmitter involved in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of the stress response (Vale et al., 1981), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) was the first endogenous ligand of the CRF family of peptides to be paired to CRF receptors. Subsequently, it has been shown to elicit cardiovascular effects mediated via both central and peripheral mechanisms (Fisher et al., 1983; Parkes et al., 1997). The 41 amino-acid (aa) peptide is present in the central nervous system (CNS) and only very low levels are in the heart and periphery. Three further cognate ligands have been paired to CRF receptors, the first being the 40 aa, urocortin 1 (Donaldson et al., 1996). Two other peptides were codiscovered independently from human and mouse cDNA libraries, leading to the evolution of two nomenclatures (Hsu & Hsueh, 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2001), and the International Union of Pharmacology has recommended that urocortin II/stresscopin-related peptide is called urocortin 2 and urocortin III/stresscopin termed urocortin 3 (Hauger et al., 2003). Although the propeptide sequences predicted by the two groups are identical, the proposed cleavage sites for the mature peptides differed slightly.

Two subtypes of receptor, CRF1 and CRF2, have been identified by molecular techniques, both of which couple positively to adenylate cyclase. In addition, three splice variants of the CRF2 subtype have been reported, but there is no evidence for any pharmacological differences to distinguish them (Hauger et al., 2003). There is no information on the relative distributions of the receptor proteins; however, their mRNAs have been mapped: mRNA for CRF1 is localised almost exclusively to the CNS, with negligible levels in the periphery. Contrastingly, CRF2 mRNA is localised to discrete areas of the CNS and high levels are present in the cardiovascular system (Nishikimi et al., 2000; Kimura et al., 2002). It is therefore hypothesised that the central pressor effects of CRF are via CRF1 and CRF2 mediate the peripheral vasoactive responses.

Intracerebroventricular injections of CRF produce an increase in mean arterial pressure (Fisher et al., 1983); however, systemic infusions of CRF cause vasodilatation in man (Hermus et al., 1987) and urocortin 1 has been shown to act as a vasodilator of human veins in vitro (Sanz et al., 2002). While CRF and urocortin 1 bind both CRF1 and CRF2 with high affinity, urocortins 2 and 3 are selective for CRF2 and have little or no affinity at CRF1 receptors. Thus, it has been proposed that urocortins 2 and 3 are important in the recovery phase of the stress response via activation of peripheral CRF2 receptors, thereby counteracting the effects of CRF1 activation in the CNS. Mice lacking CRF2 receptors have elevated blood pressure, suggesting that this pathway is also important in maintaining basal tone (Coste et al., 2000) and urocortins have been shown to cause vasodilatation in rat arteries in vitro (Rohde et al., 1996; Kageyama et al., 2003). There is little information on changes in this signalling pathway in cardiovascular disease, but one study has reported a decrease in CRF2 mRNA in failing rat hearts (Nishikimi et al., 2000).

A 30 aa antagonist, antisauvagine 30, so called because it is a truncated form of the amphibian CRF agonist sauvagine, has up to 1000-fold selectivity for CRF2 (Higelin et al., 2001). Antisauvagine 30 has been iodinated, but to date the only characterisation of this novel radioligand used receptors artificially expressed in HEK cells. CRF2 receptor protein has not been identified in mammalian cardiovascular tissue; therefore, the aims of this investigation were to use [125I]antisauvagine 30 to determine whether CRF2 receptors are present in the human cardiovascular system. We also determined if the novel endogenous CRF2 ligands have a functional role in the peripheral regulation of vascular tone in human arteries.

Methods

Patients

Internal mammary artery (IMA) was obtained from patients (11 male, two female) undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, mean age 55 years (range: 36–68 years). Cardiac tissue was obtained from patients undergoing heart–lung transplants for cystic fibrosis (four male, four female; mean age 24 years, range 18–33 years) or heart transplant operations for dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (six male, two female; mean age 44 years, range 24–59 years). Drug therapies included ACE inhibitors, AT1 receptor antagonists, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, nitrates, statins, anticoagulants and antiarrhythmics. All tissue was obtained with local ethical approval.

Materials

Human CRF, urocortin 1, urocortin 2 (43 aa) and urocortin 3 (40 aa) and mouse urocortin 2 (38 aa, Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan) stock solutions (0.1 mM) were prepared in 1% acetic acid (urocortin 1), 0.1% acetic acid (CRF) or distilled H2O (human urocortins 2 and 3 and mouse urocortin 2) and stored in aliquots at −20°C. [125I]antisauvagine 30 (specific activity ∼2000 Ci mmol−1) was from Amersham Biosciences (Bucks, U.K.). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd (Dorset, U.K.) or BDH Ltd. (Dorset, U.K.).

Radioligand binding

CRF2 receptors were characterised in human left ventricle (LV) using the selective radioligand [125I]antisauvagine 30 (Davenport & Kuc, 2002).

Tissue preparation

All radioligand binding experiments used 30 μm cryostat sections of tissue on gelatin-coated slides, except for autoradiographical studies, which used 10 μm sections.

Saturation assays

Cryostat sections of human LV were preincubated for 15 min in 50 mM Tris buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.3% bovine serum albumin at pH 7.4 and then incubated with increasing concentrations of [125I]antisauvagine 30 (4 pmol l−1–2 nmol l−1) in for 30 min at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was determined by incubating adjacent sections with 1 μM unlabelled urocortin 1. Sections were washed for 10 min in Tris-HCl buffer (mM: Tris, 50, pH 7.4) at 4°C and counted in a γ-counter.

Kinetic assays

For association assays sections were incubated with 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 in incubation buffer for increasing periods of time (0–150 min) at room temperature. Sections were then washed for 10 min in Tris-HCl buffer at 4°C and counted in a γ-counter. For dissociation assays, sections were incubated in 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 in incubation buffer for 30 min, followed by washing for increasing periods of time (0–24 h) in an excess of Tris-HCl buffer (4°C) and counted in a γ-counter. Nonspecific binding was determined using 1 μM urocortin 1.

Competition assays

Competition assays were carried out under the same conditions as for the saturation assays. Sections of human LV were incubated with 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 alone and in the presence of increasing concentrations (20 pM–10 μM) of urocortins 1 or 2. Nonspecific binding was determined using 1 μM urocortin 1.

Autoradiographical studies

Sections were incubated with 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 as described above. After washing, sections were air-dried and apposed, with 125I microscale standards (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, U.K.), to radiation-sensitive film (Kodak Biomax MR). Histological localisation was verified using immunohistochemical staining of adjacent tissue sections with antibodies raised against α-actin (Kuc, 2002) (DAKO, Bucks, U.K.).

Data analysis

Association and dissociation rate constants (Kobs and K−1, respectively), affinity constants (KD) and maximum binding densities (BMAX) were calculated using the KELL suite of programmes (Biosoft, Cambs, U.K.). All data were expressed as mean±s.e.m. Affinity constants were compared using a Mann–Whitney U-test (P<0.05) and BMAX values (expressed as fmol mg−1 protein) were compared using Student's t-test (P<0.05). Autoradiographical images were analysed using computer-assisted densitometry (Quantimet 970, Leica, Bucks, U.K.) and binding densities were expressed as amol mm−2 as described previously (Davenport & Kuc, 2002).

In vitro pharmacology

The endothelial layer was removed from rings of IMA (3 mm) using a blunt seeker and the vessels were mounted in 5 ml organ baths for the measurement of isometric tension (Wiley & Davenport, 2001). Tissue was maintained at 37°C in Krebs' solution (mM: NaCl, 90; NaHCO3, 45; KCl, 5; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5; Na2HPO4·2H2O, 1; CaCl2, 2.25; fumaric acid, 5; glutamic acid, 5; glucose, 10; sodium pyruvate, 5; pH 7.4) and gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2. Optimal basal tension was determined by constricting vessels with 100 mM KCl under increasing levels of resting tension until no greater magnitude of response was obtained. Vessels were washed and left for 10 min between additions of KCl. The absence of endothelium was verified by constricting vessels with 100 nM U46619 and testing for endothelium-dependent relaxation with 100 nM bradykinin. Rings were then left for 1 h before the start of the experiment. Constrictions were induced with 10 nM endothelin-1 (ET-1) and cumulative concentration response curves to urocortin 1 and related peptides were constructed once the constrictor response had reached a plateau. One ring of artery from each patient was constricted with 10 nM ET-1 and monitored over the time course of the experiment as a control. Each experiment was terminated with 100 mM KCl to confirm tissue viability.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as the percentage relaxation of the constrictor response to ET-1. The negative log of the concentration required to produce 50% of the maximum response of the agonist in the tissue (pD2 value) was determined for each concentration–response curve using the iterative curve fitting software Fig P (Biosoft, Cambs, U.K.). All data were expressed as mean±s.e.m. (Wiley & Davenport, 2001).

Results

Radioligand binding

Kinetic studies

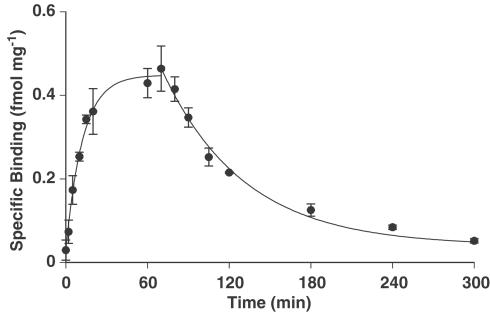

Assay conditions were optimised by characterising the binding kinetics of [125I]antisauvagine 30 in human LV. An association rate constant (Kobs) of 0.16±0.02 min−1 was obtained giving a half-time for association of 5.0±1.0 min (n=3, Figure 1). The dissociation rate constant (K−1) was calculated to be 0.010±0.0006 min−1, giving a half-time for dissociation of 68±4 min (n=3, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time-dependent association and dissociation of 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding in human LV (n=3).

Saturation assays

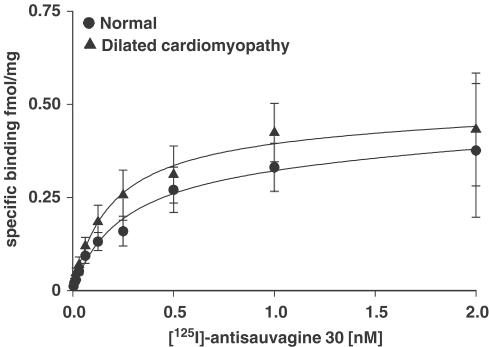

[125I]antisauvagine 30 (4 pM–2 nM) bound to normal LV with an affinity of 0.21±0.03 nM and a BMAX of 0.80±0.18 fmol mg−1 protein (n=8; Figure 2; Table 1). No change in either affinity or receptor density was observed in ventricular tissue from patients transplanted for DCM (KD: 0.18±0.03 nM; BMAX: 0.65±0.15 fmol mg−1 protein; P>0.05; n=8; Figure 2; Table 1). A one-sit fit was preferred over a two-sit fit and Hill slopes were close to unity (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Saturation binding assay for [125I]antisauvagine 30 (4 pM–2 nM) in human LV (normal, n=8 and DCM, n=8, P>0.05).

Table 1.

Saturation binding data in left ventricle of human heart

| Control | Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|---|

| BMAX (fmol mg−1) | 0.80±0.18 | 0.65±0.15 |

| KD (nM) | 0.21±0.03 | 0.18±0.03 |

| nH | 0.93±0.08 | 0.88±0.07 |

| n | 8 | 8 |

Specificity

In human LV, competition assays for urocortins 1 and 2 (5 pM–10 μM) against 0.2 nM. [125I]antisauvagine 30 yielded affinities of 24.0±5.0 and 16.1±3.4 nM, respectively (n=6). Six unrelated peptides expressed in the cardiovascular system (ET-1, atrial natriuretic peptide, apelin, proadrenomedullin peptide 12, ghrelin and angiotensin II) failed to compete for [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding sites in human LV at a concentration of 1 μM (n=3, data not shown).

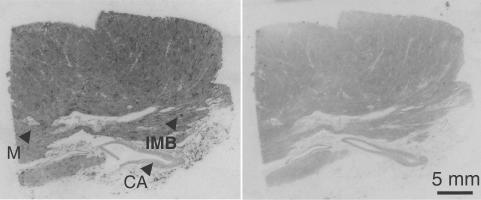

Autoradiography

The highest density of [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding was observed in small intramyocardial blood vessels of human LV (diameters <200 μm, 45.2±5.9 amol mm−2, n=5, verified in comparison with α-actin-like immunoreactivity in adjacent sections) and lower levels were detected in myocytes (8.0±3.2 amol mm−2, n=5; Figure 3). Binding was also visualised in the media of internal mammary arteries (17.7±3.9 amol mm−2, n=4).

Figure 3.

Example of 0.2 nM [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding in human LV: (a) total binding and (b) nonspecific binding. CA, coronary artery; IMB, intramyocardial blood vessel; M, myocardium.

In vitro pharmacology

Vasoreactivity

IMA produced a maximal contractile force of 15.9±1.3 mN mm−1 (response to 100 mM KCl; 55 segments from 13 patients). All segments tested produced a sustained constriction (mean force 12.1±1.01 mN mm−1) to 10 nM ET-1, a concentration previously shown to induce a submaximal response (Wiley & Davenport, 2001). Bradykinin (100 nM) did not produce vasodilatation in any segment, indicating an absence of functional endothelium.

Reversal studies

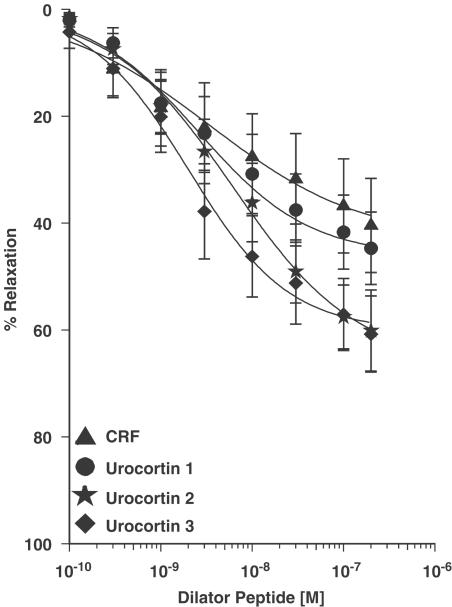

All CRF-related peptides tested (0.1–300 nM) produced endothelium-independent vasodilatation, reversing constrictions induced by 10 nM ET-1. All five CRF peptides caused a partial reversal of the constrictor response to ET-1 (Figure 4). Urocortins 2 and 3 had the greatest maximum responses of the five peptides (Table 2), producing 60±8.5% (n=8/10) and 61±7.2% (n=7/9) reversals, respectively. All the peptides had similar, nanomolar potencies as can be seen from the pD2 values (Table 2). None of the peptides tested produced a vasoconstrictor response on endothelium-denuded vessels.

Figure 4.

Concentration–response curves to human CRF receptor ligands (0.1–300 nM, n=7–9), reversing constrictions induced by 10 nM ET-1 in human endothelium-denuded IMA. Results were expressed as a percentage of the constrictor response to ET-1 (mean±s.e.m.).

Table 2.

Vasodilatation to CRF2 receptor ligands in human internal mammary artery

| Peptide | EMAX ± s.e.m. (% relaxation) | pD2±s.e.m. | n (responders/total)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRF | 40±10 | 8.28±0.27 | 8/8 |

| Urocortin 1 | 46±7.7 | 8.39±0.32 | 7/8 |

| Urocortin 2 | 60±8.5 | 8.27±0.17 | 8/10 |

| Urocortin 2 (mouse) | 39±6.3 | 8.43±0.38 | 5/7 |

| Urocortin 3 | 61±7.2 | 8.61±0.25 | 7/9 |

Not all patients responded to the peptides and the n value is given as the number of responders as a fraction of the total tested.

Discussion

We have presented the first evidence of [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding in human cardiovascular tissue. CRF2 receptors were abundant in the heart, consistent with the reported mRNA distribution (Valdenaire et al., 1997). Interestingly, particularly high levels were localised to intramyocardial blood vessels. As expected, binding was inhibited by unlabelled urocortin 1 and the CRF2 selective urocortin 2, but not by other vasoactive peptides tested, consistent with the proposal that urocortins 1 and 2 are cognate ligands for CRF2 receptors. In addition, we have demonstrated a vasodilator role for the novel endogenous ligands urocortins 2 and 3 in human arteries in vitro. [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding in human LV was saturable, reversible, specific and had high affinity, characteristics indicative of receptor–ligand interactions. Saturation assays gave a binding density of approximately 1 fmol mg−1 protein in human LV. This is comparable to the density of other recently paired orphan receptors such as the APJ receptor (∼4 fmol mg−1 protein) (Katugampola et al., 2001a) and GHS receptor (∼8 fmol mg−1 protein) (Katugampola et al., 2001b) and also to well-characterised cardiovascular receptors such as the AT1 receptor (∼5 fmol mg−1 protein) (Zisman et al., 1998) in human LV. Autoradiograms of [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding revealed a medium density of binding in the myocardium, but much higher levels were localised to the small intramyocardial vessels. Consequently, the receptor density is likely to be much higher within small coronary vessels. Receptors present on the cardiac myocytes are consistent with the inotropic effects of CRF and related peptides observed by other groups (Parkes et al., 1997; Terui et al., 2001) and also with the cardioprotective effect of urocortin (Lawrence et al., 2002). The distribution of binding in human heart is unusual for a G-protein-coupled receptor, but is similar to CGRP receptors (Coupe et al., 1990).

[125I]antisauvagine 30 bound rapidly to the tissue and spontaneously dissociated, as was found with cloned receptors expressed in HEK cells (Higelin et al., 2001). Saturation curves were monophasic and Hill slopes were close to unity, consistent with the hypothesis that it is the CRF2 subtype that is expressed in this tissue. Both urocortin 1 and the CRF2 selective urocortin 2 competed for [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding sites with nanomolar affinities. Furthermore, iterative nonlinear curve fitting produced one-site fits for both ligands, suggesting that the majority of CRF receptors in the human heart are of the CRF2 subtype.

There was no difference in either receptor density or affinity in tissue from patients transplanted for DCM. This result is at variance with the report of decreased CRF2 mRNA expression in rat hearts with DCM (Nishikimi et al., 2000); however in this study, we measured binding levels in entire sections of LV and this may mask any downregulation of receptor protein within the small vessels. Alternatively, the discrepancy could be explained by the fact that the tissue obtained from patients transplanted for DCM are in end-stage heart failure and the disease progression could have gone beyond compensatory mechanisms.

We showed for the first time that urocortins 2 and 3 are directly acting, potent vasodilators in human arteries. ET-1 produces an extremely long-lasting vasoconstriction, both in vivo (Clarke et al., 1989) and in vitro (Wiley & Davenport, 2001), and although none of the peptides tested fully reversed the constriction induced by 10 nM ET-1, the responses obtained were comparable to other established vasodilators including adrenomedullin and CGRP, in a study also conducted in IMA contracted with 10 nM ET-1 (Wiley & Davenport, 2002). Additionally, urocortin 2 reduces mean arterial pressure when systemically infused in rats (Chen et al., 2003), an effect that could be blocked with antisauvagine 30 (Mackay et al., 2003), and CRF2 knockout mice have elevated mean arterial pressure (Coste et al., 2000). Taken together, these data suggest that the peripheral CRF pathway may be important in modulating vascular tone, particularly in pathophysiological conditions, where ET-1 levels are increased (Hiroe et al., 1991; Lerman et al., 1991).

The two novel urocortins reversed ET-1-induced constrictions with a similar potency to CRF and urocotin 1, but produced the greatest maximum responses, supporting the hypothesis that they may be the endogenous ligands for CRF2 receptors in the periphery. Furthermore, both urocortins 2 and 3 show no activity at the CRF1 subtype (Hsu & Hsueh, 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2001). In agreement with the effects of human urocortin 2, the 38 aa mouse sequence of urocortin 2 was also a potent vasodilator in this study.

The source of the endogenous ligands that activate peripheral CRF receptors physiologically remains unknown. Although CRF production has been reported in the adrenal glands, the peptide is present at very low levels in human plasma (Suda et al., 1985; Watanabe et al., 1999), and plasma levels of urocortin 1 are also extremely low (Watanabe et al., 1999), although they have been reported to be elevated in patients with heart failure (Ng et al., 2004). Both urocortin 1 and CRF bind with nanomolar affinity to CRF-binding protein present in the plasma (Lewis et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2001), so the level of either peptide actually exposed to the vascular smooth muscle from the plasma is likely to be negligible. CRF-like immunoreactivity has only been detected in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Simoncini et al., 1999). This localisation may be restricted to the foetal and placental vascular beds, since extremely low levels of CRF are reported in human heart (Kimura et al., 2002). Urocortin 1-like immunoreactivity has been localised to the endothelial layer and media of coronary arteries in rats and humans (Huang et al., 2002; Kimura et al., 2002), although it did not have as great an effect as either urocortins 2 or 3 in this study. Urocortin 1 has also been detected in human cardiac myocytes (Nishikimi et al., 2000; Kimura et al., 2002). No detailed studies have been published on the localisation of urocortins 2 or 3; however, high levels of both urocortins 2 and 3 are present in the adrenals, suggesting their potential release as hormones (Hauger et al., 2003), and urocortin 2 transcript has been detected in the human heart (Hsu & Hsueh, 2001). It would therefore be tempting to speculate that the urocortins are the main endogenous ligands of CRF receptors in the periphery, rather than CRF.

In this study, the dilator effect of the CRF peptides was caused by a direct action on the vascular smooth muscle. It is not possible to test whether a greater response could be obtained with an intact endothelium with the vessels we obtain from coronary bypass surgery, since surgical manipulation does not leave a functional endothelium. The endothelium dependence of the dilator response to CRF ligands remains unclear and appears to vary between vascular beds. In the rat, endothelial denudation had no effect on dilator responses in the basilar (Schilling et al., 1998) or mesenteric artery (Lei et al., 1993); however, responses to urocortin were reduced in the absence of endothelium in coronary (Huang et al., 2002) and uterine (Jain et al., 1999) arteries.

In conclusion, the novel radioligand [125I]antisauvagine 30 was used to localise and characterise the CRF2 receptor in the human cardiovascular system. The localisation of [125I]antisauvagine 30 binding to the medial layer of blood vessels and potent vasodilator action of the novel CRF2 selective ligands urocortins 2 and 3 suggests that the CRF2 receptor may mediate a compensatory mechanism to decrease vascular tone in the periphery. This may serve to counter-balance the centrally mediated hypertensive effects of CRF and urocortin 1 and the signalling pathway could also provide a novel target for the treatment of hypertension associated with cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation. We thank the theatre and consultant staff at Papworth Hospital for help with tissue collection.

Abbreviations

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- CRF2

corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptor

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- IMA

internal mammary artery

- LV

left ventricle

References

- CHEN C.Y., DOONG M.L., RIVIER J.E., TACHE Y. Intravenous urocortin II decreases blood pressure through CRF2 receptor in rats. Regulat. Peptides. 2003;113:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARKE J.G., BENJAMIN N., LARKIN S.W., WEBB D.J., DAVIES G.J., MASERI A. Endothelin is a potent long-lasting vasoconstrictor in men. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257:H2033–H2035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTE S.C., KESTERSON R.A., HELDWEIN K.A., STEVENS S.L., HEARD A.D., HOLLIS J.H., MURRAY S.E., HILL J.K., PANTELY G.A., HOHIMER A.R., HATTON D.C., PHILLIPS T.J., FINN D.A., LOW M.J., RITTENBERG M.B., STENZEL P., STENZEL POORE M.P. Abnormal adaptations to stress and impaired cardiovascular function in mice lacking corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:403–409. doi: 10.1038/74255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUPE M.O., MAK J.C., YACOUB M., OLDERSHAW P.J., BARNES P.J. Autoradiographic mapping of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors in human and guinea pig hearts. Circulation. 1990;81:741–747. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., KUC R.E. Radioligand binding assays and quantitative autoradiography of endothelin receptors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002;206:45–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-289-9:045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONALDSON C.J., SUTTON S.W., PERRIN M.H., CORRIGAN A.Z., LEWIS K.A., RIVIER J.E., VAUGHAN J.M., VALE W.W. Cloning and characterization of human urocortin. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2167–2170. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER L.A., JESSEN G., BROWN M.R. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF): mechanism to elevate mean arterial pressure and heart rate. Regul. Peptides. 1983;5:153–161. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(83)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAUGER R.L., GRIGORIADIS D.E., DALLMAN M.F., PLOTSKY P.M., VALE W.W., DAUTZENBERG F.M. International union of pharmacology. XXXVI. Current status of the nomenclature for receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor and their ligands. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:21–26. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMUS A.R., PIETERS G.F., WILLEMSEN J.J., ROSS H.A., SMALS A.G., BENRAAD T.J., KLOPPENBORG P.W. Hypotensive effects of ovine and human corticotrophin-releasing factors in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1987;31:531–534. doi: 10.1007/BF00606625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIGELIN J., PY LANG G., PATERNOSTER C., ELLIS G.J., PATEL A., DAUTZENBERG F.M. 125I-Antisauvagine-30: a novel and specific high-affinity radioligand for the characterization of corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:114–122. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIROE M., HIRATA Y., FUJITA N. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991;68:1114–1115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90511-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSU S.Y., HSUEH A.J. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat. Med. 2001;7:605–611. doi: 10.1038/87936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG Y., CHAN F.L., LAU C.W., TSANG S.Y., HE G.W., CHEN Z.Y., YAO X. Urocortin-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat coronary artery: role of nitric oxide and K+ channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1467–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAIN V., VEDERNIKOV Y.P., SAADE G.R., CHWALISZ K., GARFIELD R.E. Endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanisms of vasorelaxation by corticotropin-releasing factor in pregnant rat uterine artery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAGEYAMA K., FURUKAWA K., MIKI I., TERUI K., MOTOMURA S., SUDA T. Vasodilative effects of urocortin II via protein kinase A and a mitogen-activated protein kinase in rat thoracic aorta. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2003;42:561–565. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200310000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATUGAMPOLA S.D., MAGUIRE J.J., MATTHEWSON S.R., DAVENPORT A.P. [125I]-(Pyr1)Apelin-13 is a novel radioligand for localizing the APJ orphan receptor in human and rat tissues with evidence for a vasoconstrictor role in man. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001a;132:1255–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATUGAMPOLA S.D., PALLIKAROS Z., DAVENPORT A.P. [125I]-His9-ghrelin, a novel radioligand for localizing GHS orphan receptors in human and rat tissue: up-regulation of receptors with athersclerosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001b;134:143–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA Y., TAKAHASHI K., TOTSUNE K., MURAMATSU Y., KANEKO C., DARNEL A.D., SUZUKI T., EBINA M., NUKIWA T., SASANO H. Expression of urocortin and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtypes in the human heart. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:340–346. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUC R.E. Radioligand binding assays and quantitative autoradiography of endothelin receptors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002;206:45–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-289-9:045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWRENCE K.M., CHANALARIS A., SCARABELLI T., HUBANK M., PASINI E., TOWNSEND P.A., COMINI L., FERRARI R., TINKER A., STEPHANOU A., KNIGHT R.A., LATCHMAN D.S. K(ATP) channel gene expression is induced by urocortin and mediates its cardioprotective effect. Circulation. 2002;106:1556–1562. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028424.02525.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEI S., RICHTER R., BIENERT M., MULVANY M.J. Relaxing actions of corticotropin-releasing factor on rat resistance arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:941–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LERMAN A., EDWARDS B.S., HALLETT J.W. Circulating and tissue endothelin immunoreactivity in advanced atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:997–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS K., LI C., PERRIN M.H., BLOUNT A., KUNITAKE K., DONALDSON C., VAUGHAN J., REYES T.M., GULYAS J., FISCHER W., BILEZIKJIAN L., RIVIER J., SAWCHENKO P.E., VALE W.W. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:7570–7575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121165198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKAY K.B., STIEFEL T.H., LING N., FOSTER A.C. Effects of a selective agonist and antagonist of CRF2 receptors on cardiovascular function in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;469:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01725-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NG L.L., LOKE I.W., O'BRIEN R.J., SQUIRE I.B., DAVIES J.E. Plasma urocortin in human systolic heart failure. Clin. Sci. 2004;106:383–388. doi: 10.1042/CS20030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIKIMI T., MIYATA A., HORIO T., YOSHIHARA F., NAGAYA N., TAKISHITA S., YUTANI C., MATSUO H., MATSUOKA H., KANGAWA K. Urocortin, a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor family, in normal and diseased heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H3031–H3039. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKES D.G., VAUGHAN J., RIVIER J., VALE W., MAY C.N. Cardiac inotropic actions of urocortin in conscious sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:H2115–H2122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REYES T.M., LEWIS K., PERRIN M.H., KUNITAKE K.S., VAUGHAN J., ARIAS C.A., HOGENESCH J.B., GULYAS J., RIVIER J., VALE W.W., SAWCHENKO P.E. Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2843–2848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROHDE E., FURKERT J., FECHNER K., BEYERMANN M., MULVANY M.J., RICHTER R.M., DENEF C., BIENERT M., BERGER H. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the mesenteric small arteries of rats resemble the (2)-subtype. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;52:829–833. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANZ E., MONGE L., FERNANDEZ N., MARTINEZ M.A., MARTINEZ-LEON J.B., DIEGUEZ G., GARCIA-VILLALON A.L. Relaxation by urocortin of human saphenous veins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:90–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHILLING L., KANZLER C., SCHMIEDEK P., EHRENREICH H. Characterization of the relaxant action of urocortin, a new peptide related to corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat isolated basilar artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMONCINI T., APA R., REIS F.M., MICELI F., STOMATI M., DRIUL L., LANZONE A., GENAZZANI A.R., PETRAGLIA F. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells: a new source and potential target for corticotropin-releasing factor. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:2802–2806. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDA T., TOMORI N., YAJIMA F., SUMITOMO T., NAKAGAMI Y., USHIYAMA T., DEMURA H., SHIZUME K. Immunoreactive corticotropin-releasing factor in human plasma. J. Clin. Invest. 1985;76:2026–2029. doi: 10.1172/JCI112204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERUI K., HIGASHIYAMA A., HORIBA N., FURUKAWA K.I., MOTOMURA S., SUDA T. Coronary vasodilation and positive inotropism by urocortin in the isolated rat heart. J. Endocrinol. 2001;169:177–183. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALDENAIRE O., GILLER T., BREU V., GOTTOWIK J., KILPATRICK G. A new functional isoform of the human CRF2 receptor for corticotropin-releasing factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1352:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALE W., SPIESS J., RIVIER C., RIVIER J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE F., OKI Y., OZAWA M., MASUZAWA M., IWABUCHI M., YOSHIMI T., NISHIGUCHI T., IINO K., SASANO H. Urocortin in human placenta and maternal plasma. Peptides. 1999;20:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILEY K.E., DAVENPORT A.P. Nitric oxide-mediated modulation of the endothelin-1 signalling pathway in the human cardiovascular system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:213–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILEY K.E., DAVENPORT A.P. Comparison of vasodilators in human internal mammary artery: ghrelin is a potent physiological antagonist of endothelin-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:1146–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZISMAN L.S., ASANO K., DUTCHER D.L., FERDENSI A., ROBERTSON A.D., JENKIN M., BUSH E.W., BOHLMEYER T., PERRYMAN M.B., BRISTOW M.R. Differential regulation of cardiac angiotensin converting enzyme binding sites and AT1 receptor density in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1998;98:1735–1741. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]