Abstract

The changes of tissue sensitivity to glucocorticoids are associated with many pathological states including neurological diseases. In the present study, using a novel in vitro post-mortem tracing method on human brain slices, we demonstrated that cortisol, a major glucocorticoid hormone in humans, affected axonal transport both in the cortex neurons in four Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and four nondemented controls.

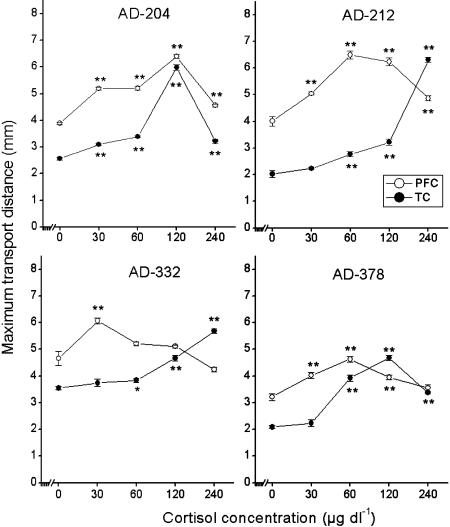

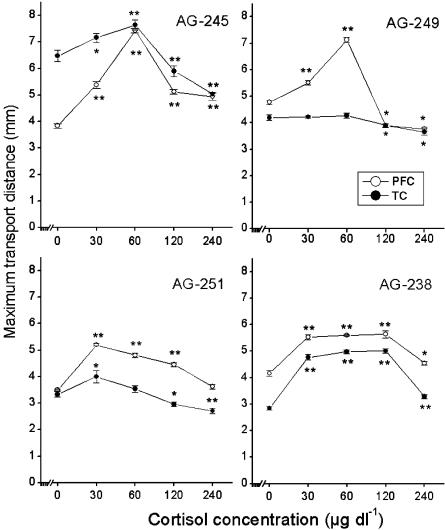

Cortisol appeared to affect axonal transport of prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporal cortex (TC) neurons in AD patients and controls in a dose-dependent way at concentrations of 30, 60, 120 and 240 μg dl−1.

Higher doses of cortisol were needed for TC neurons to achieve a similar axonal transport effect as obtained in PFC neurons in AD patients. The maximum effect (Emax) on axonal transport was achieved in PFC slices at relatively low contraction (30–120 μg dl−1), while in TC slices, a maximum effect was only reached at relatively high concentrations (120–240 μg dl−1).

For PFC and TC slices from nondemented aging subjects, lower doses of cortisol (30–60 μg dl−1) on axonal transport were sufficient to achieve the maximum effect as compared to those used in AD brain slices, while levels of more than 60 μg dl−1 of cortisol mostly depressed axonal transport.

These results suggest that glucocorticoid resistance, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of a number of common human disorders, may exist in AD brains and play an important role in neuropathological mechanisms and dementia.

Keywords: Glucocorticoid resistance, Alzheimer's disease, axonal transport, cortical neurons, post-mortem tracing, cortisol, glucocorticoid hormone, human brain

Introduction

Glucocorticoids have a broad array of life-sustaining functions and play an important role in the therapy of many diseases. Thus, changes of tissue sensitivity to glucocorticoids may be associated with and influence the course and treatment of many pathological states. Such tissue sensitivity changes have been identified as glucocorticoid resistance and hypersensitivity. It has been demonstrated that glucocorticoid resistance contributes to the pathogenesis of a number of common human disorders, including neurological diseases (Kino et al., 2003). Recent studies on the brain, an important glucocorticoid target tissue, suggest that glucocorticoid resistance may exist in the central nervous system and be related to the neuropathological mechanisms of some neurological diseases in humans such as depression (Meijer et al., 2003). Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an age-related disease and the most common cause of dementia. The neuropathological mechanisms of AD are not fully understood. Therefore, no effective therapeutic ways have been developed so far. There is strong evidence that AD is linked to abnormal functions of glucocorticoids, which is reflected not only in the changes of activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA-axis) but also in clinical syndromes (De Leon et al., 1988; Franceschi et al., 1991; Hatzinger et al., 1995). In the present study, using a novel in vitro neuronal function research method and post-mortem human brain tissue, we found that cortisol, a major glucocorticoid hormone in humans, affects axonal transport in the cortex neurons and shows obvious resistance in the cortex neurons of AD.

Methods

Human post-mortem brain tissues

Human brains were obtained from the Netherlands Brain Bank (NBB) by rapid autopsy. According to the protocol of the NBB, specific permission for brain autopsy and use of the brain and medical records for research purposes were obtained either from the patients themselves or from partners or relatives. The brains from four AD patients and four nondemented aged subjects were studied. AD was clinically diagnosed based on the Criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and the Stroke–Alzheimer's disease and Related Disorders Association. No primary neurological or psychiatric disease was found in nondemented aged subjects. The brain tissue from the right hemisphere was used for the present study. Both brains from AD patients and controls were systematically neuropathologically investigated. Neuropathological changes in AD were scored using the staging system of Braak.

In vitro post-mortem tracing protocol

Following removal of the brain from the skull, standardized pieces of gyrus from the anterior part of the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC, equivalent to Broca's area 9) and medial temporal cortex (TC, equivalent to Broca's area 21) were dissected and trimmed into slices (0.4–0.6 cm) containing the cortical layers and 1.5–2.0 cm white matter. The recovery of neuronal axonal transport from the post-mortem human brain tissue for the experimental study has been described in our previous studies (Dai et al., 1998a, 1998b; 2002). The main steps for the post-mortem tracing of axonal transport were as follows: (1) Preincubation: The prepared brain slices were immediately placed in a container with modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (M-ACSF, Sucrose, 252 mM; KCl, 3 mM; NaHCO3, 26 mM; NaH2PO4, 1.4 mM; D-glucose, 10 mM, pH 7.4) at 0–4°C. The main difference between M-ACSF and ACSF was that sucrose was substituted for NaCl to maintain a constant osmolarity. In addition, CaCl2 and MgSO4 were omitted in M-ACSF. Total preincubation time prior to the tracer injection was 1.5–2.0 h. (2) Injection: The tissue was put on a small plate, which was placed on a large plate with ice. The injection areas were viewed under an operating microscope. A glass micropipette with 5% biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, molecular weight 10 000, Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) in Tris buffered saline (TBS, 0.05 M Tris, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.6) was mounted on a micromanipulator and penetrated the slice surface to a depth of 2 mm into the cortical layers (layers 3–5). Iontophoretic injection of the tracer was made with a constant current voltage device using a 7 μA positive current at 50 mV with 7 s on, 7 s off duty cycles over 1.5 min. The tip diameter of the micropipette was 40 μm. M-ACSF was used in the small plate during the tracer injection in order to keep the tissue moist. After injection, the tissue was put back in M-ACSF for about 20 min before incubation. (3) Incubation: The tissue was incubated in a beaker containing 300 ml ACSF (NaCl, 120 mM; KCl, 3 mM; CaCl2, 1.0 mM; MgSO4, 1.0 mM; NaHCO3, 26 mM; NaH2PO4, 1.4 mM; D-glucose, 10 mM, pH 7.3) at room temperature (22°C) for 12 h and 95% O2+5% CO2 were constantly supplied with a membrane oxygenator placed in the ACSF during the incubation period. Cortisol (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to the ACSF at concentrations of 30, 60, 120 and 240 μg dl−1, respectively. (4) Fixation and sectioning: The tissue was fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 3 days. After fixation, brain tissue was placed in 20% sucrose in the same buffer for 1 day for cryoprotection before being sectioned, frozen and serially cut on a cryostat (35 μm). Sections were collected in 0.05 M TBS (0.05 M Tris, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.6) in sequential order in two vials for each brain slice. Sections were treated with 100% methanol and 3% H2O2 each for 10 min in order to reduce endogenous peroxidase activity. (5) Tracer detection: One vial of sections from each brain slice was incubated with the avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) complex (1 : 800) in a mixture of 0.05 M Tris, 0.9% NaCl, 0.25% gelatine and 0.5% Triton-X 100, pH 7.4 for 2 h at room temperature. After several rinses with TBS, the sections were incubated with 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), 0.2% nickel-ammoniumsulfate and 0.003% H2O2 in 0.05 M TBS (pH 7.4), and mounted on gelatine-coated slides. Then the sections were dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped.

Measurement of axonal transport

All stained sections were processed to be able to measure the lengths of labeled fibers. The section was mounted on a Zeiss microscope with a stage connected to two motors able to move the stage along the X–Y axis by means of a joystick. A small marker was used on an ocular lens of the microscope to indicate the position when the stage was moved. The distance of the stage movement was displayed on a recorder. In most cases, the labeled fibers left the injection site and ran into the white matter in a straight line. The distance could thus be determined by measuring the labeled fibers from the injection center to the part where no staining was visible under the × 100 microscopic visual field. In a few brain slices, the labeled fibers ran in a curved line. Their lengths were measured segment by segment. For each section, the eight longest labeled fibers were measured.

Analysis of data

We selected the eight longest labeled fibers from all measured sections in each brain slice for statistical analysis, and used their average value as the maximum transport distance (MTD). A statistical analysis of significant difference of the dose–response effect in prefrontal and TC in each case was carried out by use of One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's test by comparing MTD at a given concentration of cortisol (30, 60, 120 or 240 μg dl−1) with that at 0 μg dl−1 (no-treatment). ANOVA was also used to analyze and compare the maximum effect in the prefrontal and TC neurons in AD and nondemented aged brains. A P-value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The brain slices were treated with cortisol at concentrations of 30, 60, 120 and 240 μg dl−1, respectively. The dose–response effect of cortisol on the MTD of PFC and TC neurons from four AD and four nondemented aged brains was analyzed. Cortisol appeared to affect axonal transport of PFC and TC neurons in AD patients and controls in a dose-dependent way (Figures 1 and 2). Interestingly, higher doses of cortisol were needed for TC neurons to achieve a similar axonal transport effect as obtained in PFC neurons in AD patients (Figure 1). In three out of four AD cases (AD-212, 332, 378; Figure 1), the effect on axonal transport was not visible at a concentration of 30 μg dl−1 in TC neurons compared to that of 0 μg dl−1. In contrast, cortisol produced a significant effect on PFC neurons at a concentration of 30 μg dl−1 in all AD cases (Figure 1). In addition, the maximum effect (Emax) on axonal transport was achieved in PFC slices at 30 (6.06±0.12 mm, AD-332), 60 (6.49±0.15 mm, AD-212; 4.68±0.09 mm, AD-378), 120 μg dl−1 (6.40±0.64 mm, AD-204) (Figure 1 and Table 1), respectively, while in TC slices a maximum effect was only reached at concentrations of 120 μg dl−1 (5.99±0.11 mm, AD-204; 4.63±0.10 mm, AD-378) or 240 μg dl−1 (6.30±0.10 mm, AD-212; 5.69±0.09 mm, AD-332) (Figure 1 and Table 1). For PFC and TC slices from nondemented aging subjects (Figure 2 and Table 1), lower doses of cortisol (30–60 μg dl−1) on axonal transport were sufficient to achieve the maximum effect as compared to those used in AD brain slices, while levels of more than 60 μg dl−1 of cortisol mostly depressed axonal transport. In nondemented aged control case 96-249 (Figure 2), no dose–response effect was observed at a concentration of 30 or 60 μg dl−1 in TC slices, indicating that 30 μg dl−1 or more of cortisol already produced a depressing effect on axonal transport in this case. We compared the maximum effect of cortisol in PFC with that in TC in AD and nondemented aged controls (AG). Except two cases (AG-249, AG-251) in AG, no differences were found between PFC and TC in each case in AD and AG (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Dose–response effects in four AD brains. A statistical analysis of significant difference was carried out by comparing MTD at a given concentration of cortisol (30, 60, 120 or 240 μg dl−1) with that at 0 μg dl−1 (no-treatment). A higher concentration of cortisol was needed to achieve the maximum effect in TC compared to that in PFC. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=8). Asterisks indicate a significant difference *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

Figure 2.

Dose–response effects in four brains of nondemented aged subjects (AG). A statistical analysis of significant difference was carried out by comparing MTD at a given concentration of cortisol (30, 60, 120 or 240 μg dl−1) with that at 0 μg dl−1 (no-treatment). A relatively lower dose of cortisol (30–60 μg dl−1) achieved the maximum effects both in PFC and TC, and more than 120 μg dl−1 cortisol mostly depressed the axonal transport. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=8). Asterisks indicate a significant difference *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

Table 1.

The maximum effect (Emax) of cortisol on distance of axonal transport (mm) in prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporal cortex (TC) in AD and nondemented aged controls (AG)

| AG-238 | AG-245 | AG-249 | AG-251 | |

| PFC | 5.60±0.03 | 7.44±0.08 | 7.13±0.09 | 5.20±0.05 |

| TC | 5.01±0.09 | 7.64±0.18 | 4.51±0.30** | 3.99±0.23** |

| AD-204 | AD-212 | AD-332 | AD-378 | |

| PFC | 6.40±0.06 | 6.49±0.15 | 6.06±0.12 | 4.68±0.09 |

| TC | 5.99±0.11 | 6.30±0.10 | 5.69±0.09 | 4.63±0.10 |

Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=8). Asterisks indicate a significant difference

P<0.01.

Neuropathological examination showed that the TC underwent more severe neuropathological changes, such as senile plaques (SP), neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and disruption of interneuronal network (INN), than the PFC in these AD cases, but no difference was found in AG (data is not shown, see Dai et al., 2002).

Discussion

In the present study, we found a ‘bell-shaped' type effect of cortisol on axonal transport in cortical neurons in human brains in most cases, a stimulating effect at low concentrations, and a depressing effect at high concentrations. The exact mechanism behind the effect of cortisol on axonal transport has not been studied before, and thus is unknown. Axonal transport plays a crucial role in neuronal survival and function. In normal neurons, the axonal transport system is composed of microtubules, microtubule-associated proteins (MAP) and accessory factors (Hirokawa, 1998). For the stimulating effects of cortisol at relatively low concentrations (physiological level), it may be that, through nongenomic mechanisms, for example, by membrane receptors or ion channels (Schumacher, 1990), cortisol may affect the intracellular concentrations of Ca2+, which is one of the important accessory factors in axonal transport (Hammerschlag et al., 1975). It has been shown that increasing free intracellular calcium may induce the dephosphorylation of tau proteins, which belong to the family of MAP, and influence the axonal transport (Adamec et al., 1997). It is possible that cortisol may increase glucose utilization and oxidative metabolisms and, consequently, ATP production. Increasing production of ATP may induce ‘cascade' effects, such as a change of functional state of protein kinases and phosphatases (Cyr & Brady, 1992), which regulate the function of axonal transport via the change of the phosphorylation state of MAP. In addition, cortisol may be involved in more complex mechanisms through classic genomic actions via intracellular glucocorticoid receptors. However, at relatively high concentrations (stress or pharmacological level), cortisol may show reverse effects and depress axonal transport.

In our previous study, we demonstrated a decrease of axonal transport in the TC neurons as compared to axonal transport in the PFC neurons in AD patients, but not in nondemented controls (Dai et al., 2002). Interestingly, in the present study, we found that cortisol promoted axonal transport in AD patients. Higher doses of cortisol were needed for TC neurons to achieve a similar effect as was obtained in PFC neurons at lower doses, indicating that the more severely affected brain areas in AD need higher concentrations of cortisol to achieve a similar effect in axonal transport. An explanation for our finding is that resistance to the action of cortisol exists in AD brains in the severely affected brain areas such as TC, which normally have high glucocorticoid receptors. The resistance to cortisol action may be due to a change of glucocorticoids receptor functions, not due to downregulation of the number of glucocorticoid receptor. In fact, the high amount of glucocorticoid receptors remains unchanged or is even higher in AD brains, and the presence of equal or even higher glucocorticoid receptor gene expression is also observed in hippocampal neurons in AD (Seckl et al., 1993; Wetzel et al., 1995). In addition, we found that the maximum effect of cortisol on axonal transport in PFC was not different compared with that in the TC in all AD cases and two AG cases, indicating that resistance changes might be due to the change of sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptor, not the defect of the whole glucocorticoid receptor system. The observed significant differences of maximum effect between PFC and TC in two cases (AG-249, AG-251) of AG could be explained by the fact that the maximum effect may appear at concentrations between 0 and 30 μg dl−1, which was not obtained by our recent observation.

Glucocorticoids play an important role in many neural functions that are mediated by classic genomic effects via intracellular glucocorticoid receptors or nongenomic mechanisms. The glucocorticoid hormone cortisol is essential for cognitive appraisal and affects numerous cognitive domains, including attention, perception, memory, and emotional processing in humans (Lupien et al., 1998; Erickson et al., 2003). Cortisol also participates in energy metabolism and gene expression in the brain, and it coordinates behavioral adaptation to the environmental and internal conditions through the regulation of many neurotransmitters and neural circuits. In the present study, we found that glucocorticoid resistance exists in AD brain, and is related to the degree of neuropathological changes, suggesting that glucocorticoid resistance in AD brain may contribute to neuroendocrinal changes, neuropathological mechanisms and dementia.

In fact, activation of the HPA axis is a consistent endocrine sign in AD (De Leon et al., 1988; Hatzinger et al., 1995). In healthy humans, the normal glucocorticoid secretion shows a strong 24-h rhythm with peak concentrations in the early morning and a trough in the late afternoon. Such a circadian change of the level of glucocorticoid secretion is necessary for the normal functioning of different brain areas. The brain areas with a high glucocorticoid receptor level such as the hippocampus and TC seem to need the peak concentrations of glucocorticoids to facilitate their functioning, since the glucocorticoid receptor can only be occupied in these brain areas during the diurnal peak. However, in aged persons, the normal high circadian fluctuation of cortisol secretion is diminished by increasing basal levels on the one hand and decreasing the diurnal peak on the other. This alteration is much more obvious in AD patients (De Leon et al., 1988; Hatzinger et al., 1995). Our recent findings suggest that the changed pattern of cortisol secretion in AD may be a reflection of ‘glucocorticoid resistance' in AD brains since glucocorticoid resistance in AD may disturb not only the neural functions but also the negative feedback regulation via different brain areas such as hippocampus (Jacobson & Sapolsky, 1991), and result in an activation of the HPA-axis. Glucocorticoid resistance in AD may also contribute to the pathogenetic process of AD and induce cascade changes, such as the loss of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis (Landfield & Eldridge, 1994), abnormal production and degradation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ), development of NFT and neuronal degeneration. Indeed, a previous study found that a moderate to high dose regimen of prednisolone decreases amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) production and increases Aβ degradation in the normal human brain but not in AD patients (Tokuda et al, 2002), indicating that glucocorticoid hormone may have a beneficial effect on the metabolism of Aβ in the normal human brain, and such an effect presents a resistance in AD patients. This is of importance since a large amount of intracerebral Aβ deposition is a typical neuropathological hallmark for AD. However, it is not clear whether glucocorticoid resistance in AD brain is the cause or the consequence of neuropathological changes, and needs to be investigated further. Therefore, our findings may give a new idea for AD treatment.

In conclusion, we developed a novel method to investigate pharmacologically the neuronal functions from post-mortem human brains. Such a method may provide an important new tool for the study of neuropathological mechanisms and the identification of new drugs for the treatment of human neurological diseases such as AD.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Kooreman, and J. Wouda for their help in collecting brain material and to W.T.P. Verweij for secretarial help. This study was supported in part by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), ‘Chunhui project' (China Ministry of Education), and by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) for a cooperation project between the Netherlands and China (03CDP014). The human post-mortem brains were obtained from the Netherlands Brain Bank (coordinator Dr R. Ravid).

Abbreviations

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AG

nondemented aged controls

- BDA

biotinylated dextran amine

- HPA-axis

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- INN

disruption of interneuronal network

- MTD

maximum transport distance

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- SP

senile plaques

- TBS

Tris buffered saline

- TC

medial temporal cortex

References

- ADAMEC E., MERCKEN M., BEERMANN M.L., DIDIER M., NIXON R.A. Acute rise in the concentration of free cytoplasmic calcium leads to dephosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau. Brain Res. 1997;757:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CYR J.L., BRADY S.T.Molecular motors in axonal transport. Cellular and molecular biology of kinesin Mol. Neurobiol. 19926137–155.Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI J., BUIJS R.M., KAMPHORST W., SWAAB D.F. Impaired axonal transport of cortical neurons in Alzheimer's disease is associated with neuropathological changes. Brain Res. 2002;948:138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI J., SWAAB D.F., BUJIS R.M. ‘Dead neurons' still have the potential of recovering axonal transport. Lancet. 1998a;351:499–500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78689-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI J., SWAAB D.F., VAN DER VLIET J., BUJIS R.M. Postmortem tracing reveals the organization of hypothalamic projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the human brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998b;400:87–102. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981012)400:1<87::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LEON M.J., MCRAE T., TSAI J.R., GEORGE A.E., MARCUS D.L., FREEDMAN M., WOLF A.P., MCEWEN B. Abnormal cortisol response in Alzheimer's disease linked to hippocampal atrophy. Lancet. 1988;2:391–392. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERICKSON K., DREVETS W., SCHULKIN J. Glucocorticoid regulation of diverse cognitive functions in normal and pathological emotional states. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003;27:233–246. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCESCHI M., AIRAGHI L., GRAMIGNA C., TRUCI G., MANFREDI M.G., CANAL N., CATANIA A. ACTH and cortisol secretion in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1991;54:836–837. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.9.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMERSCHLAG R., DRAVID A.R., CHIU A.Y. Mechanism of axonal transport: a proposed role for calcium ions. Science. 1975;188:273–275. doi: 10.1126/science.47182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HATZINGER M., Z'BRUN A., HEMMETER U., SEIFRITZ E., BAUMANN F., HOLSBOER-TRACHSLER E., HEUSER I.J. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system function in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1995;16:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIROKAWA N. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science. 1998;279:519–526. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON C., SAPOLSKY R.M. The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Endocr. Rev. 1991;12:118–134. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINO T., DE MARTINO M.U., CHARMANDARI E., MIRANI M., CHROUSOS G.P. Tissue glucocorticoid resistance/hypersensitivity syndromes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;85:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDFIELD P.W., ELDRIDGE J.C. Evolving aspects of the glucocorticoid hypothesis of brain aging: hormonal modulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis. Neurobiol. Aging. 1994;15:579–588. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUPIEN S.J., DE LEON M., DE SANTI S., CONVIT A., TARSHISH C., NAIR N.P., THAKUR M., MCEWEN B.S., HAUGER R.L., MEANEY M.J. Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:69–73. doi: 10.1038/271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEIJER O.C., KARSSEN A.M., De KLOET E.R. Cell- and tissue-specific effects of corticosteroids in relation to glucocorticoid resistance: examples from the brain. J. Endocrinol. 2003;178:13–18. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUMACHER M. Rapid membrane effects of steroid hormones: an emerging concept in neuroendocrinology. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:359–361. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SECKL J.R., FRENCH K.L., O'DONNELL D., MEANEY M.J., NAIR N.P., YATES C.M., FINK G. Glucocorticoid receptor gene expression is unaltered in hippocampal neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Brain Res. 1993;18:239–345. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90195-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOKUDA T., OIDE T., TAMAOKA A., ISHII K., MATSUNO S., IKEDA S. Prednisolone (30–60 mg day−1) for diseases other than AD decreases amyloid beta-peptides in CSF. Neurology. 2002;58:1415–1418. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WETZEL D.M., CHURCHILL B.M., KAZEE A.M., HAMILL R.W. Glucocorticoid receptor mRNA in Alzheimer's diseased hippocampus. Brain Res. 1995;679:72–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00230-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]