Abstract

Platelet–leukocyte aggregation (PLA) links haemostasis to inflammation. The role of nitric oxide (NO) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, -2, -3, -9) in PLA regulation was studied.

Homologous human platelet–leukocyte suspensions were stimulated with thrombin (0.1–3 nM) and other proteinase activated receptor-activating peptides (PAR-AP), including PAR1AP (0.5–10 μM), PAR4AP (10–70 μM), and thrombin receptor-activating peptide (1–35 μM).

PLA was studied using light aggregometry with simultaneous measurement of oxygen-derived free radicals, dual colour flow cytometry, and phase-contrast microscopy.

The release of NO was measured using a porphyrinic nanosensor, while MMPs were investigated by Western blot, substrate degradation assays, immunofluorescence microscopy, and flow cytometry. The levels of P-selectin and microparticles (MP) in PLA were measured by flow cytometry.

PLA was also characterized using pharmacological agents: S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO, 0.01–10 μM), 1H-Oxadiazole quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ, 1 μM), NG-L-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 100 μM) and compounds that modulate the actions of MMPs such as phenanthroline (100 μM), monoclonal anti-MMP antibodies, and purified MMPs.

PAR agonists concentration-dependently induced PLA, an effect associated with the release of microparticles (MP) and the translocation of P-selectin to the platelet surface.

NO and radicals were also released during PLA. Inhibition of NO bioactivity by the concomitant release of free radicals or by the treatment with L-NAME or ODQ stimulated PLA, while pharmacological administration of GSNO decreased PLA.

PAR agonist-induced PLA resulted in the liberation of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9.

During PLA, MMPs were present on the cell surface, as shown by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence.

PLA led to the activation of latent MMPs to active MMPs, as shown by Western blot and substrate degradation assays.

Inhibition of MMPs actions by phenanthroline and by the antibodies attenuated PLA. In contrast, purified active, but not latent, MMPs amplified thrombin-induced PLA.

It is concluded that NO and MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 play an important role in regulation of PAR agonist-induced PLA.

Keywords: Platelet–leukocyte aggregation, nitric oxide, matrix metalloproteinases

Introduction

Platelet–leukocyte aggregation (PLA), an integral component of interactions between platelets and leukocytes, is a part of normal haemostasis beneficial to wound healing and clotting. PLA is also essential for leukocyte recruitment, an important stage of inflammatory and immune reactions (Granger & Kubes, 1994). However, increased PLA is evidenced in the circulation of patients with acute coronary syndromes and cardiopulmonary bypass (Klinger & Jelkmann, 2002). Moreover, PLA plays an important role in the development of atherosclerotic lesions in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E (Huo et al., 2003).

The initial heterotypic platelet–leukocyte contact is mediated by P-selectin, a protein of the α granule membrane of resting platelets, which is rapidly translocated to the surface during platelet activation (Larsen et al., 1989; Moore, 1998). In addition to P-selectin, platelets contribute to PLA by releasing microparticles (MPs). Microparticles, vesicles derived from platelet plasma membrane, express platelet-specific receptors GPIIb/IIIa, GPIb/IX/V and P-selectin, and support platelet aggregation and PLA (Pasquet et al., 1996; Merten et al., 1999; Forlow et al., 2000).

In the present study, we investigated PLA that was stimulated with proteinase activated receptor (PAR) agonists. One of the well-known PAR agonists is thrombin, which is a multifunctional serine proteinase generated during blood coagulation. Thrombin interacts with cells via a specific proteolysis of the extracellular NH2-terminal of PARs, which leads to exposure of a new tethered ligand, binding intramolecularly to the receptor and initiating signal transduction (Lau et al., 1994). Two of the four PARs, PAR1 and PAR4, have been identified in human platelets and are responsible for thrombin-induced platelet activation (Kahn et al., 1999). Specific PAR-activating peptides (PAR-APs) have been designed to study thrombin-induced cell activation. These peptides mimic the tethered ligands, activating receptors without proteolysis, and they have been used as selective pharmacological probes of PAR functions (Vassallo et al., 1992; Chung et al., 2002).

Stimulation of human platelets with PAR agonists results in the release of mediators of aggregation including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Chung et al., 2002). MMPs comprise a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, exhibiting differential proteolytic activity against various proteins of the extracellular matrix (Woessner, 1999). Recently, five MMPs including MMP-1, -2, -3, -9 and -14 have been identified in human, porcine, rat and mouse platelets (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Kazes et al., 2000; Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2001; Galt et al., 2002; Jurasz et al., 2002; Jayachandran et al., 2003; Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004). The experiments using inhibitors, as well as purified MMP-1 and -2, have shown that these enzymes may prime platelets for adhesion and aggregation (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2001; Galt et al., 2002; Jurasz et al., 2002). Moreover, MMP-2 and -14 are mediators of tumour cell-induced platelet aggregation that plays an important role in the haematogenous dissemination of cancer (Jurasz et al., 2001; Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004). In contrast, MMP-9, which is expressed in platelets in lower amounts than MMP-1 or -2 (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a), counteracts the platelet-aggregatory effects of MMP-2 and inhibits aggregation, while MMP-3 is devoid of significant effects on aggregation (Galt et al., 2002). Interestingly, the release and actions of platelet MMPs are regulated by nitric oxide (NO) (Sawicki et al., 1997; Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001).

MMPs are also expressed by human leukocytes (Bar-Or et al., 2003). In contrast to platelets where MMPs appear not to be associated with granules (Sawicki et al., 1998), human granulocytes contain specific gelatinase granules (Borregaard & Cowland, 1997) that release MMPs such as MMP-9 upon stimulation with endotoxin and proinflammatory cytokines (Van den Steen et al., 2000; 2003; Albert et al., 2003). MMPs play an important role in migration of immune cells to sites of inflammation by degrading basement membranes and extracellular matrix components. In addition, MMPs are involved in regulation of chemokine and cytokine activities through proteolytic cleavage of these proteins (McQuibban et al., 2000b; Van den Steen et al., 2000; 2003; Opdenakker et al., 2001).

The objectives of this investigation were: (1) to characterize an in vitro model of human PLA induced by thrombin, TRAP, PAR1AP and PAR4AP, and (2) to study the effects of NO and MMPs on PAR agonist-induced PLA.

Methods

Platelet and leukocyte suspensions

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Alberta and the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas-Houston. Homologous (from the same donor) suspensions of platelets and leukocytes were prepared from citrated whole blood collected from healthy volunteers, who had not taken any drugs known to affect platelet and leukocyte functions for 2 weeks prior to the study. Washed platelets were isolated by differential centrifugation and resuspended in Tyrode's solution (2.5 × 108 platelets ml−1), as previously described (Radomski & Moncada, 1983). Homologous mixed, polymorphonuclear and mononuclear leukocytes were isolated using a Lympholyte®-polygradient separating medium (Cedarlane® Laboratories, Hornby, ON, Canada). Briefly, blood layered over medium was centrifuged at 500 g for 30 min at room temperature. The medium allows separation of mononuclear from polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Both mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells were harvested, centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min at room temperature and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 5 × 107 cells ml−1. Erythrocyte contamination was less than 5% of the total cell number.

Lumi-aggregometry

Platelets and leukocytes were coincubated, in the ratio indicated in each experiment, in a whole-blood ionized calcium lumi-aggregometer (Chronolog, Havertown, PA, U.S.A.) at 37°C for 2 min. The platelet number remained constant in all experiments. PLA was initiated by the addition of PAR agonists and monitored by Aggro-Link software for at least 9 min. For experiments using pharmacological inhibitors or purified human MMP proteins, PLA was initiated after 1–2 min of preincubation with these compounds. Monoclonal antibodies against MMPs were preincubated for 20 min prior to addition of PAR agonists. In some experiments, the simultaneous PLA generation of oxygen-derived radicals was measured by luminol (50 μM)-enhanced chemiluminescence and expressed as % luminescence (Freedman & Keaney, 1999).

Porphyrinic nanosensor

The release of NO during PLA was measured by a porphyrinic nanosensor (diameter 0.5 mm) (Malinski & Taha, 1992; Malinski & Czuchajowski, 1996). The sensor was placed in the platelet–leukocyte suspensions with the help of a micromanipulator. The response current (analytical signal) was measured in amperometric mode at 0.68 V versus silver/silver chloride electrode (SSCE) or in differential pulse voltammetry mode (potential scan 0.45–0.72 V versus SSCE) using GAMRY (GAMRY Institutes, Pennsylvania, PN, U.S.A.) voltammetric analyzer and software. The sensor was calibrated using saturated aqueous solution of NO (1.72 mM).

Flow cytometry

PLA was also quantified by dual colour flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A). The samples collected after aggregation were incubated for 15 min in the dark with saturating concentrations CD45-FITC and CD62P-PE to label leukocytes and platelets, respectively. Samples were diluted in FACS Flow fluid and analyzed immediately (within 10 min of incubation) by gating leukocytes, based on their FITC-CD45 fluorescence and light scatter profile, and quantifying the platelet fluorescent signal associated with leukocytes. Formation of PLA was expressed as the % of leukocytes exhibiting platelet CD62P-PE fluorescence in the total counted events.

For the measurement of microparticles, the samples of PAR agonist-stimulated platelets were incubated with PE-labelled monoclonal antibodies against human glycoprotein (GP)Ib (CD42-PE, DAKO Diagnostics Canada Inc.). Microparticle population was distinguished and gated by the forward scatter cutoff that was set to the immediate left of the single intact platelet population of an unstimulated sample. Microparticles were reported as the % of PE-positive cells in the gated region of the total counted events.

In order to analyze P-selectin on the surface of individual platelets and to minimize platelet aggregation that likely interferes with the binding of antibodies, no stirring or vortexing steps were used. Platelet samples were first activated with PAR agonists for 10 min, and then diluted 10 times with physiological saline. In some experiments, platelets were preincubated with inhibitors for 1–2 min prior to the addition of agonists. Platelet samples were then incubated for 15 min in the dark without stirring at room temperature in the presence of saturating concentrations of PE-labeled anti-P-selectin-specific monoclonal antibodies (CD62P-PE, Becton Dickinson). In the flow cytometry analysis, a two-dimensional analysis gate of forward and side light scatter was drawn to include single platelets and exclude platelet aggregates and microparticles. The quantification of P-selectin was expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on a fluorescence histogram of the gated platelet population.

For each sample measured using flow cytometry, 10,000 events were acquired and the fluorescence was expressed using a logarithmic scale.

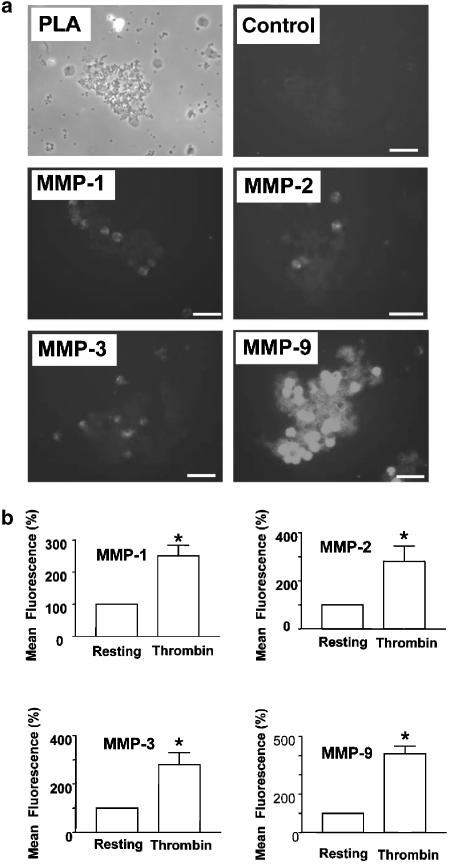

Membrane surface MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 in resting and thrombin (1 nM)-activated platelet–leukocyte suspensions was analyzed by flow cytometry as described by Kazes et al. (2000). Briefly, the MMP immunoreactivity was probed with the use of human monoclonal antibodies against MMPs as the primary antibodies, and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig specific polyclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson) as the secondary antibodies.

Phase-contrast and immunofluorescence microscopy

PLA was induced with thrombin (1 nM) and the reaction was terminated at 20% of maximal aggregation, as determined using the aggregometer. The samples were fixed by adding an equal volume of 4% formaldehyde in Tyrode's buffer, and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were first viewed using phase-contrast Olympus CKX41 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY, U.S.A.). Cytospins were prepared by centrifuging 120 μl of the different cell suspensions onto a glass slide in a cytocentrifuge (AC-060, Cytopro, Wescor Inc., Logan, Utah, U.S.A.) Slides were allowed to air dry at room temperature and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation for 30 min at room temperature in Dulbecco's PBS containing 10% BSA (DPBS/BSA). Slides were incubated for 60 min with either anti-MMP-1 (5 μg ml−1), anti-MMP-2 (20 μg ml−1), anti-MMP-3 (5 μg ml−1) and anti-MMP-9 (10 μg ml−1) antibodies in blocking buffer (DPBS/BSA). IgG (10 μg ml−1) was used as isotype control. Following washing with DPBS/BSA, slides were incubated with a 1 : 300 dilution of anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC for 60 min. Following washing with PBS, the slides were mounted in SlowFade Light Antifade solution (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) and examined using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 imaging microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., Thornwood, NY, U.S.A.). The immunofluorescence images were captured using AxioCam MRm digital camera (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc.).

Western blotting

The presence of MMP-1-, MMP-2-, MMP-3- and MMP-9-related immunoreactivity during PLA was measured as described before (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; 2000; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Mayers et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2002). Briefly, the pellets obtained from centrifugation (10,000 × g for 2 min) of 1 ml platelet–leukocyte incubate were homogenized, sonicated and centrifuged (Radomski et al., 2002), and the resultant supernatants (25 μg protein per lane) were subjected to 12% SDS–PAGE. To study the MMP immuoreactivity in the releasate from 1 ml platelet–leukocyte incubate stimulated with thrombin (1 nM), 10 μl of releasate was loaded per lane. Following electrophoresis and transfer, the blots were probed with monoclonal antibodies reactive against human MMPs (0.1–0.5 μg ml−1). The MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 immunoreactivity bands were revealed by means of enhanced luminescence kit and quantified using a ChemiDoc XRS system (Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004).

MMP substrate degradation assays

To quantify the enzymatic activities of MMP-1 and -3 released during PLA, activity assay kits were purchased from Chemicon and the measurements performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, following PLA, samples of platelet–leukocyte suspensions were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature and the resultant supernatant stored at −80°C until assayed for the presence of MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 activities. The activities of MMP-1 and -3 were expressed as ng per μg of total protein in the sample or normalized to the control level, respectively.

The gelatinolytic activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were measured by zymography as previously described (Radomski et al., 1998; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Jurasz et al., 2001; Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001; Albert et al., 2003; Cedro et al., 2003; Marcet-Palacios et al., 2003; Mayers et al., 2003; Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004). Zymography was performed by subjecting the releasates (10 μl per lane) to 8% SDS–PAGE with copolymerized gelatin (2 mg ml−1; Sigma) as substrate. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed with 2% Triton X-100, and then incubated in incubation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer with 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.5) at 37°C until the activities of the enzymes could be determined. After incubation, the gels were stained with 0.05% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Sigma) in a mixture of methanol : acetic acid : water (2.5 : 1 : 6.5) and destained in 4% methanol with 8% acetic acid. The gelatinolytic activities were detected as transparent bands against the background of Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gelatin. The MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities were then quantified using a ChemiDoc XRS system (Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004).

Reagents, peptides, antibodies and purified proteinases

Apyrase, S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO), aspirin, luminol and NG-L-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Oakville, ON, Canada). 1H-Oxadiazole quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) was from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Ellisvile, MO, U.S.A.). All other reagents were analytical grade.

TRAP (thrombin receptor-activating peptide, Ser-Phe-Leu-Leu-Arg-Asn-Pro-Asn-Asp-Lys-Tyr-Glu-Pro-Phe-amide) was purchased from Sigma. PAR1AP (Thr-Phe-Leu-Leu-Arg-amide) and PAR4AP (Ala-Tyr-Pro-Gly-Lys-Phe-amide) (Chung et al., 2002) were synthesized by the Alberta Peptide Institute (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada). The purity (>95% by HPLC) and composition of peptides were verified by mass spectrometry and the concentrations of stock solutions dissolved in 25 mM HEPES buffer were measured by quantitative amino-acid analysis. P-selectin antagonist, γ-aminobutyric-WVDW (Appeldoorn et al., 2003), was purchased form Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

To study MMPs the following monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-MMP-1, -3 and -9 were purchased from Oncogene Research Products (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and anti-MMP-2 was from Chemicon International, (Temecula, CA, U.S.A.). Fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD45 monoclonal antibodies directed against human leukocyte common antigen (CD45-FITC) were from Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A., while phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD62P (P-selectin, CD62P-PE) and glycoprotein (GP)Ib (CD42-PE) were from DAKO Diagnostics Canada Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada. Thrombin was obtained from Chronolog (Havertown, PA, U.S.A.).

Purified MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 were from Chemicon. Purified MMP-2 and MMP-3 are supplied as a mixture of zymogen and active enzyme, while MMP-1 and -9 preparations contain mainly zymogens. 4-Aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA, 0.1 mM) was used to activate MMPs (Sawicki et al., 1997). The enzymes were activated by incubation with APMA for 1 h at 37°C. Under these conditions, >85% of latent MMP-2 and MMP-9 was activated, as measured by zymography. The concentration of APMA present in platelet–leukocyte incubates did not affect thrombin-induced PLA (P>0.05, n=3). In all experiments using antibodies IgG (Chemicon) was used as isotype control.

Statistics

The results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test and Student's t-tests were performed, where appropriate. Statistical significance was considered when P<0.05.

Results

NO and PAR agonist-induced PLA

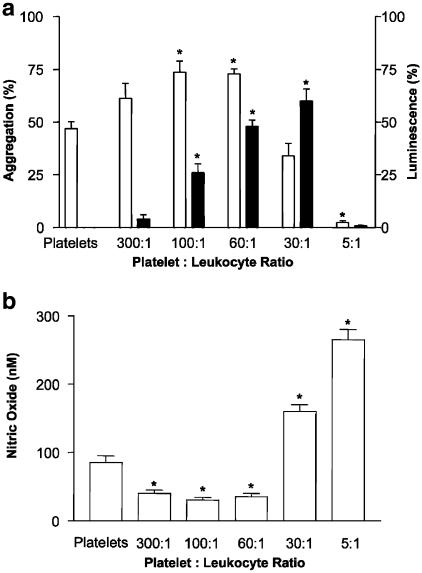

Figure 1a shows the effects of leukocytes on platelet aggregation induced by thrombin, as measured by lumi aggregometry. Only viable, but not fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde (data not shown), leukocytes exerted biphasic effects on platelet aggregation and the release of oxygen-derived reactive species. At high platelet : leukocyte ratios (60 : 1 and 100 : 1), leukocytes enhanced platelet aggregation and the corresponding release of reactive species; while at the lowest ratio (5 : 1), they suppressed aggregation and free radical release. These biphasic effects of mixed (mononuclear and polymorphonuclear) leukocytes were not detected when mononuclear leukocytes were used. Indeed, lower numbers of mononuclear leukocytes (60 : 1 and 100 : 1) only slightly potentiated thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (5+2%, n=3), while higher numbers did not affect aggregation (P>0.05, n=3). The results described below were obtained with mixed leukocyte suspensions.

Figure 1.

Biphasic effects of leukocytes on platelet aggregation and free radicals, and NO release. (a) Platelets and leukocytes were coincubated (from 300 : 1 to 5 : 1), and the EC50 of thrombin (0.3 nM) was added to initiate aggregation (open bar) and generation of oxygen-derived free radicals (closed bar). Data are mean±s.e.m., n=8. (b) A biphasic effect of leukocytes on the release of NO during PLA induced by thrombin (0.3 nM). Data are mean ±s.e.m., n=3. *P<0.05 platelet–leukocyte suspensions versus platelets.

The effects of leukocytes on the release of NO were also biphasic. The concentration of NO in thrombin-stimulated platelets was 85±10 nM (Figure 1b). At a ratio of 300 : 1, the NO concentration decreased about 50% and reached a minimum of 30±4 nM at a ratio of 100 : 1. However, at a ratio of 60 : 1 and higher the exponential increase in NO concentrations was observed. The highest NO concentration of 256±15 nM was measured at a ratio of 5 : 1.

The addition of ODQ (1 μM), a selective inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase (Moro et al., 1996), completely reversed inhibition of PLA by leukocytes at a ratio of 30 : 1 (n=5), but only partially (48±12%, n=5) at a ratio of 5 : 1. In contrast, the inhibitory effect of leukocytes at a ratio of 5 : 1 on PLA was completely reversed by L-NAME (100 μM, n=3). In contrast to ODQ and L-NAME, an NO donor, GSNO (0.01–10 μM) (Radomski et al., 1992), inhibited PLA in a concentration-dependent manner. Similar results were obtained with TRAP, PAR1AP and PAR4AP (data not shown).

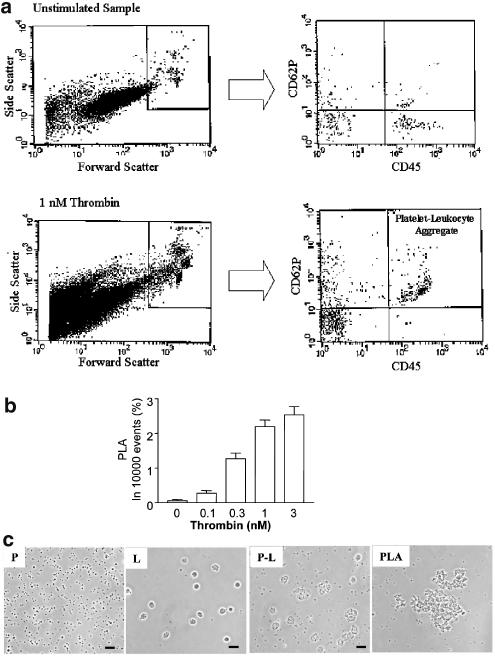

Ratio 60 : 1 was used in all subsequent experiments. Figure 2a–c shows that thrombin induced PLA as measured by flow cytometry and phase-contrast microscopy. Concentration–response curves were also obtained for other PAR agonists (PAR1AP=0.5–10 μM; TRAP=1–35 μM; PAR4AP=10–70 μM; n=5). PLA was inhibited by a P-selectin antagonist, γ-aminobutyric-WVDW (0.05–5.0 μM) with the maximal effect of 75±18%, mean±s.e.m., n=3.

Figure 2.

Thrombin-induced PLA, as measured by flow cytometry and observed using phase-contrast microscopy. (a) Representative flow cytometry recordings. Scatter plots (left panels) showing the light scattering properties of total 10 000 events of an unstimulated sample and thrombin (1 nM)-stimulated sample. The population of PLA is distinguished and gated by the forward scatter cutoff that is set to the immediate right of the individual platelet population of an unstimulated sample. With the use of PE-labeled anti-CD62P and FITC-labeled anti-CD45 antibodies, the corresponding two-parameter scatter plots (right panels) show the percent of PLA, positive in both PE- and FITC-fluorescence, in the 10,000 counted events. (b) The statistical analysis of thrombin-induced PLA. Data are mean±s.e.m. (n=5). (c) PLA as viewed using phase-contrast microscopy. (P) Resting platelets; (L) Resting leukocytes; (P–L) platelet–leukocyte suspension; and (PLA) Thrombin (1 nM)-induced PLA. Scale bar: 20 μm.

The effects of PAR agonists on PLA were also associated with the release of MPs (15- to 28-fold increase, n=5).

MMP and PAR agonist-induced PLA

Figure 3 shows the effects of aspirin (cyclooxygenase inhibitor), apyrase (ADP scavenger) and phenanthroline (MMP inhibitor) on PAR agonist-induced PLA, as measured by flow cytometry. All three inhibitors reduced PAR agonist-induced PLA, phenanthroline being the most effective. Similar results were obtained using aggregometry (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of aspirin, phenanthroline and apyrase on PLA, as measured by flow cytometry. PLA was stimulated by EC50s of PAR agonists in the presence of aspirin (ASA, 300 μM), phenanthroline (Phen, 100 μM) or apyrase (Apy, 300 μg ml−1). Data are mean±s.e.m., n=5–9, *P<0.05 treatments versus PAR agonist control, #P<0.05 ASA and Apy versus Phen.

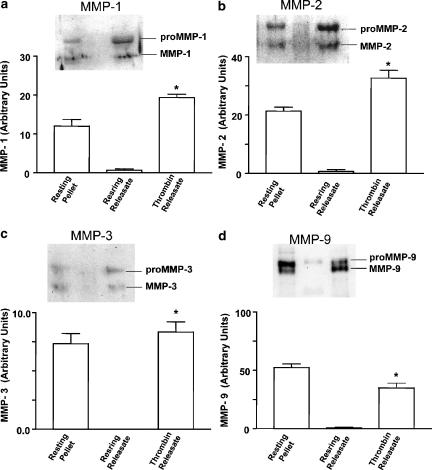

MMPs that were released during PLA were characterized using Western blotting, enzyme activity assays, immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Western blot analysis showed that both latent and active MMPs were present in resting platelet–leukocyte pellets (Figure 4). In these pellets, the ratio between pro and active MMP was 1.6±0.2, 1.8±0.4, 1.4±0.3 and 2.2±0.2 (mean±s.e.m., n=3–5) for MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9, respectively. Thrombin resulted in a significant (P<0.05) decrease (0.7±0.1, 0.9±0.2; 0.5±0.1, 1.1±0.2, respectively) in the ratios between pro and active MMPs in platelet–leukocyte pellets indicating MMP activation. In the absence of thrombin, little or no MMP-related immunoreactivity could be detected in platelet–leukocyte releasates. Thrombin-induced PLA led to a significant increase in the levels of active MMPs in the releasate (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of MMPs in platelet–leukocyte incubates. The presence of MMP-1 (a), MMP-2 (b), MMP-3 (c) and MMP-9 (d) was probed in the pellets (Resting Pellet) and releasates (Resting Releasate) of resting platelet–leukocyte incubates. Thrombin Releasate: the presence of MMPs in platelet–leukocyte releasates stimulated with thrombin (0.5 nM). Data are mean±s.e.m., n=3–5. Insets: representative immunoblots showing the MMP-related immunoreactivity. *P<0.05 Thrombin Releasate versus Resting Releasate.

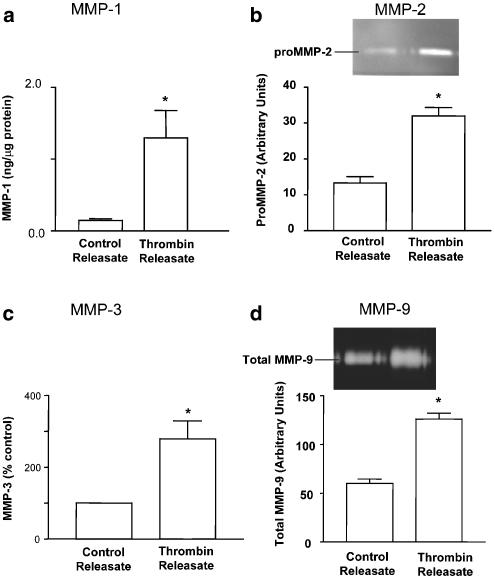

Thrombin-induced PLA also resulted in increased activity of active MMPs in the releasate, as shown using substrate degradation assays for MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The activity of MMPs in platelet–leukocyte releasates. PLA was induced by thrombin (0.5 nM) and the activities of MMP-1 (a), MMP-2 (b), MMP-3 (c) and MMP-9 (d) were measured in the releasates of control (Control Releasate) and thrombin (Thrombin Releasate)-stimulated platelet–leukocyte incubates. Insets: representative zymograms. Data are mean ±s.e.m., n=4–6. *P<0.05 Thrombin Releasate versus Control Releasate.

The presence of these MMPs during thrombin-induced PLA was also detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. The images presented in Figure 6a show that MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 were associated with the surface of platelet–leukocyte aggregates.

Figure 6.

Membrane expression of MMPs during thrombin-induced PLA, as shown by immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. (a) Immunofluorescence microscopy of MMPs in PLA. Platelet–leukocyte aggregation was induced by thrombin (0.5 nM) and the slides were first examined using phase-contrast microscopy (PLA). The samples were then immunostained and viewed using immunofluorescence microscope (MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9). C: IgG control. Scale bars: 20 μm. (b) Flow cytometry of MMPs in PLA. Resting or thrombin (0.5 nM)-stimulated platelet–leukocyte suspensions were subjected to flow cytometry analysis using specific anti-MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 monoclonal antibodies. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=3. *P<0.05 thrombin-stimulated versus resting incubates.

Finally, membrane expression of these MMPs during thrombin-induced PLA was further confirmed using flow cytometry. Indeed, Figure 6b shows that stimulation of platelet–leukocyte incubates with thrombin resulted in increased MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9-related fluorescence on the surface of platelet–leukocyte aggregates.

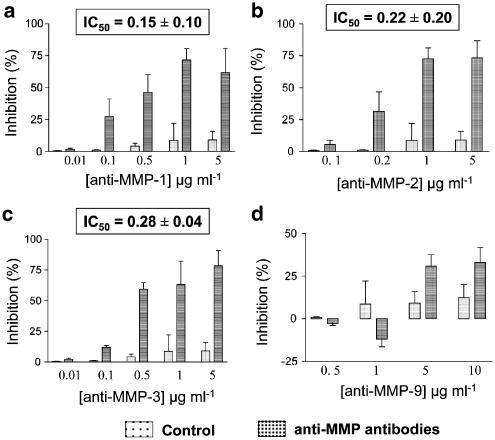

Figure 7a–c shows that monoclonal antibodies against MMP-1, -2 and -3 inhibited PLA in a concentration-dependent manner, as measured by aggregometry. Moreover, these antibodies decreased thrombin-induced PLA, as measured by flow cytometry with IC50s of 0.25±0.09, 0.31±0.12 and 0.36±0.07 μg ml−1 (n=3), for MMP-1, -2 and -3, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effects of monoclonal antibodies against MMPs on PLA. Platelet–leukocyte suspensions were preincubated with monoclonal antibodies against (a) MMP-1, (b) MMP-2, (c) MMP-3, (d) MMP-9 or IgG control prior to thrombin stimulation (0.5 nM). Insets show IC50 values. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=6.

The anti-MMP-9 antibody regulated PLA biphasically, as measured by aggregometry: at lower concentrations (0.5–1 μg ml−1) PLA was potentiated (3–12%), while at higher concentrations (5–10 μg ml−1) PLA was inhibited by this treatment (Figure 7d). The biphasic effect of anti-MMP-9 antibody was not detected when PLA was measured by flow cytometry. The antibody (0.5–10 μg ml−1) inhibited PLA in a concentration-dependent manner with the maximal effect of 65±18%, mean±s.e.m., n=3).

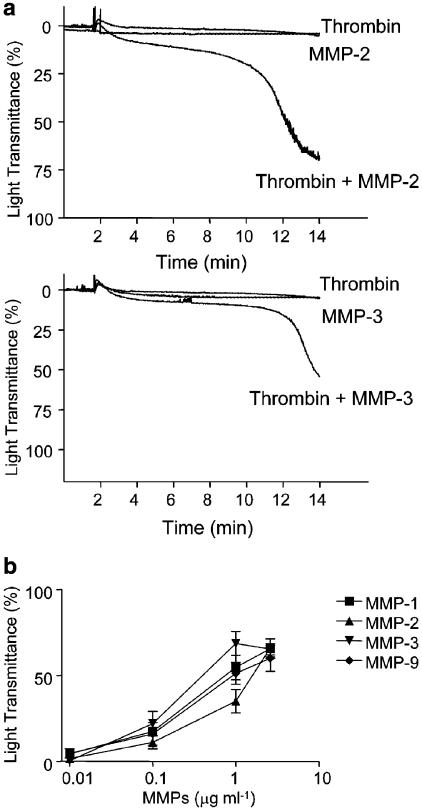

Figure 8 shows that purified MMP-2 and MMP-3 (supplied by the manufacturer as a mixture of latent and activated enzyme) (a), as well as APMA-activated MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 (b) all potentiated PLA induced by subthreshold concentrations of thrombin. In contrast, pro-MMP-1 and pro-MMP-9 exerted no significant effect on PLA (P>0.05, n=3).

Figure 8.

Effects of human purified MMPs on PLA stimulated with thrombin. (a) Platelet–leukocyte suspensions were preincubated with MMP-2 (1 μg ml−1) or MMP-3 (2.6 μg ml−1) before stimulation with a subthreshold concentration of thrombin (0.1 nM). Results are representative of five independent experiments. (b) Concentration–response curves showing potentiation of thrombin (0.1 nM)-stimulated PLA by MMPs. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=3–5.

Discussion and conclusions

PAR agonist-induced PLA and its inhibition by NO

A model of PAR agonist-induced human PLA was characterized. We used PAR agonists with different pharmacological profile to investigate PAR-induced PLA including thrombin (nonselective PAR agonist with proteolytic activity), thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP, a nonselective PAR agonist without any proteolytic activity), PAR1AP (a selective PAR1 agonist) and PAR4AP (a selective PAR4 agonist). Interestingly, thrombin activates both platelet (PAR1 and PAR4) and leukocyte (PAR1, PAR2 and PAR4) receptors (Kahn et al., 1999; Macfarlane et al., 2001).

At physiological concentrations of platelets and leukocytes, mixed (polymorphonuclear and mononuclear) leukocytes potentiated PAR agonist-induced aggregation, while higher (inflammation-mimicking) concentrations of leukocytes inhibited PAR agonist-induced PLA and the associated free radical release. Similar relationships were not observed with mononuclear leukocytes, indicating that these cells do not play a major role in PAR agonist-induced PLA. Since both platelets (Radomski et al., 1990a, 1990b; Malinski et al., 1993) and neutrophils (McCall et al., 1989) have the capacity to release NO, we measured the release of NO during PLA using a selective porphyrinic nanosensor. In the absence of leukocytes, platelets aggregated by the EC50 concentrations of thrombin generated NO that attenuated aggregation. However, in the presence of low concentrations of leukocytes, the concomitant increase in the levels of oxygen-derived free radicals (as measured by chemiluminescence) could reduce the bioactivity of NO. Indeed, the interactions between NO and radicals such as O2− are likely to account for a decrease in NO bioactivity on platelets (Radomski et al., 1987b; McCall et al., 1989), leading to increased PLA. Interestingly, PLA is associated with generation of hydrogen peroxide formed by dismutation of O2− (Nagata et al., 1993). However, at high leukocyte concentrations, the high production of NO (most likely from leukocytes) not only scavenged O2− and diminished its concentration but also was sufficient to inhibit PLA.

The inhibitory effect of leukocytes (at a ratio of 30 : 1) on PLA was reversed by ODQ, an inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase (Garthwaite et al., 1995; Moro et al., 1996), suggesting the involvement of cyclic GMP pathway in this inhibition. However, the inhibitory effects of large amounts of NO released by higher concentrations of leukocytes could only be reversed by L-NAME implicating cyclic GMP-independent mechanisms in this effect of NO. Furthermore, GSNO, an NO donor effectively inhibited PAR agonist-stimulated PLA. Thus, similar to platelet aggregation (Radomski et al., 1987a, 1987b), NO is a major inhibitory mediator of PLA.

PLA was further detected using phase contrast microscopy and quantified by flow cytometry. The use of flow cytometry complemented aggregometry, as the latter method measures larger cell aggregates than the former method. Furthermore, flow cytometry enabled us a more selective measurement of platelet–leukocyte aggregates. In flow cytometry experiments, platelet–leukocyte aggregates were identified by the size and the double labelling using antibodies directed against common leukocyte antigen and P-selectin. Using this experimental approach we found that PAR agonists increased PLA, to a similar extent, in a concentration-dependent manner.

As expected, we found that MPs and P-selectin play an important role in PAR agonist-stimulated PLA. Although MPs are substantially smaller than the intact platelets, they participate in cell–cell interactions, involving platelets, leukocytes and endothelium (Merten et al., 1999; Forlow et al., 2000). P-selectin mediates neutrophil recruitment to sites of platelet deposition (Granger & Kubes, 1994; Konstantopoulos et al., 1998). We showed that γ-aminobutyric-WVDW, a P-selectin antagonist (Appeldoorn et al., 2003), inhibited PLA indicating that this receptor plays a critical role in PAR agonist-stimulated PLA. Although selectins mediate initial margination and rolling, activated β2-integrins are necessary for stable adhesion and spreading of leukocytes on the immobilized platelets (Diacovo et al., 1996; Kuijper et al., 1996; 1998; Weber & Springer, 1997; Gahmberg et al., 1998; Simon et al., 2000; Santoso et al., 2002).

Stimulation of PAR agonist-induced PLA by MMPs

We have previously shown that PAR agonist-induced aggregation of human platelets depends upon stimulation of thromboxane A2 (TXA2)-, MMP- and ADP-dependent pathways of aggregation (Chung et al., 2002). Therefore, we used respective inhibitors of these pathways including aspirin (cyclooxygenase inhibitor), phenanthroline (MMP inhibitor) and apyrase (ADP scavenger) (Sawicki et al., 1997; Jurasz et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2001; Chung et al., 2002) to study PAR agonist-induced PLA. The experiments using light aggregometry and flow cytometry showed that although all three inhibitors differentially reduced PLA, phenanthroline was consistently the most effective pharmacological agent to inhibit PLA induced by all PAR agonists. Therefore, we investigated the role of MMPs in PLA. Since platelets and leukocytes are known to express MMPs including MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Pei, 1999; Kazes et al., 2000; Jurasz et al., 2001; 2002; Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001; Opdenakker et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2001; Galt et al., 2002; Bar-Or et al., 2003; Jayachandran et al., 2003), we focused on these enzymes as potential mediators of PLA.

Studies using immunoblot showed that these MMPs are present in resting platelet–leukocyte suspensions. Stimulation of these incubates with thrombin led to the activation and liberation of MMPs to the releasate. This translocation was associated with increased enzyme activities in the releasate. The immunofluorescence and flow cytometry data provided strong evidence for the presence of MMPs on the surface of PLA. Most MMPs are synthesized and released into the extracellular space as proenzymes, which are bound to specific (tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases) or nonspecific (α2-macroglobulin) inhibitors and remain latent until activated. We suggest that PAR agonists induce the translocation of pro-MMPs (either from platelets or leukocytes) to the surface of PLA where these proteinases are activated.

Once released during PAR stimulation, platelet–leukocyte MMPs appear to stimulate PLA. The inhibitory effects of monoclonal antibodies against MMP-1, -2 and -3 further support the proaggregatory roles of these MMPs. This is consistent with the known stimulatory roles of MMP-1 and -2 in platelet adhesion and aggregation (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Kazes et al., 2000; Radomski et al., 2001; Galt et al., 2002; Jurasz et al., 2002; Jayachandran et al., 2003). In contrast, MMP-9 acts as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a). Using aggregometry we found that anti-MMP-9 antibodies exerted biphasic (stimulator at low and inhibitor at high concentrations) effects on PLA. The stimulator effect most likely reflects an increase in platelet aggregation caused by anti-MMP-9 antibodies because this enhancement could not be detected by flow cytometry that selectively measures platelet–leukocyte aggregates. This is consistent with the notion that MMP-9 acts as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a). The pharmacological experiments exploring the effects of monoclonal antibodies against MMP-1, -2 and -3 on PLA showed that each of the antibodies on its own resulted in a robust (60–75%) inhibition of aggregation. The experiments with phenanthroline also suggest that the maximal level of inhibition of PLA is approximately 75%. It is unlikely that the antibodies used in these experiments exerted nonspecific effects on PLA since this possibility was ruled out in control experiments using isotype-specific IgG. Moreover, we have no evidence for reciprocal crossreactivity of monoclonal anti-MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9 antibodies. Therefore, we suggest that the interactions between these four MMPs regulate PLA. In addition to MMPs, some other factors that are generated by activated leukocytes can also participate in PLA regulation. These include platelet activating factor, and/or other than MMPs leukocyte granule proteinases such as cathepsin G and elastase (Del-Maschio et al., 1990).

To further probe the effects of MMPs on PLA we used purified human MMP-1, -2, -3 and -9. As with platelet aggregation (Sawicki et al., 1997; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a; Galt et al., 2002), incubation of purified MMPs with platelet–leukocyte suspensions did not result in PLA. However, MMPs greatly potentiated the effects of subthreshold concentrations of thrombin on PLA. The requirement for priming platelet–leukocyte suspensions with PAR agonist in order to reveal the effects of MMPs indicates that a cellular target for the action of these enzymes is expressed upon cell activation.

The mechanisms of MMP actions on PLA remain to be elucidated. Since active, but not latent, enzymes exert their effects on PLA it is likely that these actions are related to the proteolytic properties of MMPs. MMPs hydrolyze Gly-Leu and Gly-Ile bonds, thus degrading the extracellular matrix component (ECM) such as collagen that contain these domains (Lauer-Fields et al., 2000). In addition to the ECM, MMPs can also cleave proteins such as big endothelin-1 (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999b) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-3 (McQuibban et al., 2000a), resulting in protein activation or degradation, respectively. The interactions of MMPs with integrins have also been described. The association of MMP-1 with α2β1 integrin confines this proteinase to the points of cell contact with collagen, so that the ternary complex of integrin, proteinase, and substrate function together to regulate ECM degradation and migration (Stricker et al., 2001). Strongin and co-workers showed that MT1-MMP via interactions with αvβ3 integrin promotes MMP-2 maturation (Deryugina et al., 2001) and enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (Deryugina et al., 2002). Our group has also shown that platelet receptors GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa (Martinez-Cuesta et al., 2001; Radomski et al., 2001; Alonso-Escolano et al., 2004) are likely to be upregulated by the MT1-MMP/MMP-2 system. This upregulation leads to increased binding of von Willebrand factor to platelets and promotes their adhesion to the endothelium (Radomski et al., 2001; Upadhya & Strasberg, 2002). Furthermore, platelet MMPs proteolytically process GPIb during ageing leading to platelet activation and injury (Bergemeier et al., 2003). In addition, MMP-1 is known to stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation, thus promoting clustering of β1-integrins to focal adhesion points (Galt et al., 2002). All these actions may contribute to PLA-promoting effects of MMPs.

Finally, it is clear that the presence of leukocytes makes PAR agonist-induced PLA qualitatively and quantitatively different from PAR agonist-induced platelet aggregation. This is evidenced by the following observations: (1) PAR agonist-induced PLA is highly (60–75%) dependent on the release of MMPs, while PAR agonist-induced platelet aggregation is only partially (25–30%) dependent on the release of these proteinases (Sawicki et al., 1997; Chung et al., 2002); (2) PAR4AP-induced platelet aggregation is MMP-independent (Chung et al., 2002), while PAR4AP-induced PLA is MMP-dependent; (3) MMP-3, which does not exert a significant effect on platelet aggregation (Galt et al., 2002), plays a role in PLA; and (4) MMP-9 inhibits thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a), but stimulates thrombin-induced PLA.

We conclude that PAR agonists induce PLA and this process is regulated by NO and MMPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the University of Texas-Houston to MWR. MWR was a CIHR scientist.

Abbreviations

- Apy

apyrase

- ASA

aspirin

- GSNO

S-nitroso-glutathione

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinases

- MP

microparticle

- NO

nitric oxide

- ODQ

1H-Oxadiazole quinoxalin-1-one

- PAR-AP

proteinase activated receptor-activating peptides

- PLA

platelet–leukocyte aggregation

- Phen

phenanthroline

- TRAP

thrombin receptor activating peptide

References

- ALBERT J., RADOMSKI A., SOOP A., SOLLEVI A., FROSTELL C., RADOMSKI M.W. Differential release of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and nitric oxide following infusion of endotoxin to human volunteers. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2003;47:407–410. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALONSO-ESCOLANO D., STRONGIN A.Y., CHUNG A.W., DERYUGINA E.I., RADOMSKI M.W. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase stimulates tumour cell-induced platelet aggregation: role of receptor glycoproteins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;141:241–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPELDOORN C.C.M., MOLENAAR T.J.M., BONNEFOY A., VAN LEEUVEN S.H., VANDERVOORT P.A.H., HOYLAERTS M.F., VAN BERKEL T.J.C., BIESSEN E.A.L. Rational optimization of a short human p-selectin-binding peptide leads to nanomolar affinity antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10201–10207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAR-OR A., NUTTALL R.K., DUDDY M., ALTER A., KIM H.J., IFERGAN I., PENNINGTON C.J., BOURGOIN P., EDWARDS D.R., YONG V.W. Analyses of all matrix metalloproteinase members in leukocytes emphasize monocytes as major inflammatory mediators in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2003;126:2738–2749. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGEMEIER W., BURGER P.C., PIFFATH C.L., HOFFMEIESTER K.M., HARTWIG J.H., NIESWANDT B., WAGNER D.D. Metalloproteinase inhibitors improve the recovery and hemostatic function of in vitro-aged or -injured mouse platelets. Blood. 2003;102:4229–4235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORREGAARD N., COWLAND J.B. Granules of the human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood. 1997;89:3503–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEDRO K., RADOMSKI A., RADOMSKI M.W., RUZYLLO W., HERBACZYNSKA-CEDRO K. Release of matrix metalloproteinase-9 during balloon angioplasty in patients with stable angina: a preliminary study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2003;92:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG A.W., JURASZ P., HOLLENBERG M.D., RADOMSKI M.W. Mechanisms of action of proteinase-activated receptor agonists on human platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL-MASCHIO A., EVANGELISTA V., RAJTAR G., CHEN Z.M., CERLETTI C., DE_GAETANO G. Platelet activation by polymorphonuclear leukocytes exposed to chemotactic agents. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:H870–H879. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.3.H870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERYUGINA E.I., RATNIKOV B., MONOSOV E., POSTNOVA T.I., DISCIPIO R., SMITH J.W., STRONGIN A.Y. MT1-MMP initiates activation of pro-MMP-2 and integrin alphavbeta3 promotes maturation of MMP-2 in breast carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;263:209–223. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERYUGINA E.I., RATNIKOV B.I., POSTNOVA T.I., ROZANOV D.V., STRONGIN A.Y. Processing of integrin alpha(v) subunit by membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase stimulates migration of breast carcinoma cells on vitronectin and enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9749–9756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIACOVO T.G., ROTH S.J., BUCCOLA J.M., BAINTON D.F., SPRINGER T.A. Neutrophil rolling, arrest, and transmigration across activated, surface-adherent platelets via sequential action of P-selectin and the beta 2-integrin CD11b/CD18. Blood. 1996;88:146–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-PATRON C., MARTINEZ-CUESTA M.A., SALAS E., SAWICKI G., WOZNIAK M., RADOMSKI M.W., DAVIDGE S.T. Differential regulation of platelet aggregation by matrix metalloproteinases-9 and -2. Thromb. Haemostasis. 1999a;82:1730–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-PATRON C., RADOMSKI M.W., DAVIDGE S.T. Vascular matrix metalloproteinase-2 cleaves big endothelin-1 yielding a novel vasoconstrictor. Circ. Res. (Online) 1999b;85:906–911. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORLOW S.B., MCEVER R.P., NOLLERT M.U. Leukocyte–leukocyte interactions mediated by platelet microparticles under flow. Blood. 2000;95:1317–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREEDMAN J.E., KEANEY J.F. Nitric oxide and superoxide detection in human platelets. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAHMBERG C.G., VALMU L., FAGERHOLM S., KOTOVUORI P., IHANUS E., TIAN L., PESSA_MORIKAWA T. Leukocyte integrins and inflammation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.: Cmls. 1998;54:549–555. doi: 10.1007/s000180050183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALT S.W., LINDEMANN S., ALLEN L., MEDD D.J., FALK J.M., MCINTYRE T.M., PRESCOTT S.M., KRAISS L.W., ZIMMERMAN G.A., WEYRICH A.S. Outside-in signals delivered by matrix metalloproteinase-1 regulate platelet function. Circ. Res. (Online) 2002;90:1093–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019241.12929.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARTHWAITE J., SOUTHAM E., BOULTON C.L., NIELSEN E.B., SCHMIDT K., MAYER B. Potent and selective inhibition of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANGER D.N., KUBES P. The microcirculation and inflammation: modulation of leukocyte–endothelial cell adhesion. J. Leukocyte Biol. 1994;55:662–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUO Y., SCHOBER A., FORLOW S.B., SMITH D.F., HYMAN M.C., JUNG S., LITTMAN D.R., WEBER C., LEY K. Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Nat. Med. 2003;9:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAYACHANDRAN M., OWEN W.G., MILLER V.M. Effects of ovariectomy on aggregation, secretion, and metalloproteinases in porcine platelets. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H1679–H1685. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00958.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JURASZ P., CHUNG A.W., RADOMSKI A., RADOMSKI M.W. Nonremodeling properties of matrix metalloproteinases: the platelet connection. Circ. Res. (Online) 2002;90:1041–1043. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000021398.28936.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JURASZ P., SAWICKI G., DUSZYK M., SAWICKA J., MIRANDA C., MAYERS I., RADOMSKI M.W. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 in tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation: regulation by nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 2001;61:376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHN M.L., NAKANISHI_MATSUI M., SHAPIRO M.J., ISHIHARA H., COUGHLIN S.R. Protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 mediate activation of human platelets by thrombin. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:879–887. doi: 10.1172/JCI6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZES I., ELALAMY I., SRAER J.D., HATMI M., NGUYEN G. Platelet release of trimolecular complex components MT1-MMP/TIMP2/MMP2: involvement in MMP2 activation and platelet aggregation. Blood. 2000;96:3064–3069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINGER M.H., JELKMANN W. Role of blood platelets in infection and inflammation. J. Interferon Cytokine Res.: Off. J. Int. Soc. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:913–922. doi: 10.1089/10799900260286623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONSTANTOPOULOS K., NEELAMEGHAM S., BURNS A.R., HENTZEN E., KANSAS G.S., SNAPP K.R., BERG E.L., HELLUMS J.D., SMITH C.W., MCINTIRE L.V., SIMON S.I. Venous levels of shear support neutrophil–platelet adhesion and neutrophil aggregation in blood via P-selectin and beta2-integrin. Circulation. 1998;98:873–882. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.9.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUIJPER P.H., GALLARDO_TORES H.I., LAMMERS J.W., SIXMA J.J., KOENDERMAN L., ZWAGINGA J.J. Platelet associated fibrinogen and ICAM-2 induce firm adhesion of neutrophils under flow conditions. Thromb. Haemostasis. 1998;80:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUIJPER P.H., GALLARDO TORRES H.I., VAN DER LINDEN J.A., LAMMERS J.W., SIXMA J.J., KOENDERMAN L., ZWAGINGA J.J. Platelet-dependent primary hemostasis promotes selectin- and integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion to damaged endothelium under flow conditions. Blood. 1996;87:3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARSEN E., CELI A., GILBERT G.E., FURIE B.C., ERBAN J.K., BONFANTI R., WAGNER D.D., FURIE B. PADGEM protein: a receptor that mediates the interaction of activated platelets with neutrophils and monocytes. Cell. 1989;59:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAU L.F., PUMIGLIA K., COTE Y.P., FEINSTEIN M.B.Thrombin-receptor agonist peptides, in contrast to thrombin itself, are not full agonists for activation and signal transduction in human platelets in the absence of platelet-derived secondary mediators Biochem. J. 1994303391–400.Part 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUER-FIELDS J.L., TUZINSKI K.A., SHIMOKAWA K., NAGASE H., FIELDS G.B. Hydrolysis of triple-helical collagen peptide models by matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13282–13290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACFARLANE S.R., SEATTER M.J., KANKE T., HUNTER G.D., PLEVIN R. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:245–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALINSKI T., CZUCHAJOWSKI L.Measurements by electrochemical methods Methods of Nitric Oxide Research 1996New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 319–339.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- MALINSKI T., TAHA Z. Nitric oxide release from a single cell measured in situ by a porphyrinic-based microsensor. Nature. 1992;358:676–678. doi: 10.1038/358676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALINSKI T., RADOMSKI M.W., TAHA Z., MONCADA S. Direct electrochemical measurement of nitric oxide released from human platelets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;194:960–965. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCET-PALACIOS M., GRAHAM K., CASS C., BEFUS A.D., MAYERS I., RADOMSKI M.W. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP increase the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in vascular smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;307:429–436. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINEZ-CUESTA M.A., SALAS E., RADOMSKI A., RADOMSKI M.W. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 in platelet adhesion to fibrinogen: interactions with nitric oxide. Med. Sci. Monitor. 2001;7:646–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYERS I., HURST T., PUTTAGUNTA L., RADOMSKI A., MYCYK T., SAWICKI G., JOHNSON D., RADOMSKI M.W. Cardiac surgery increases the activity of matrix metalloproteinases and nitric oxide synthase in human hearts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001;122:746–752. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.116207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYERS I., HURST T., RADOMSKI A., JOHNSON D., FRICKER S., BRIDGER G., CAMERON B., DARKES M., RADOMSKI M.W. Increased matrix metalloproteinase activity after canine cardiopulmonary bypass is suppressed by a nitric oxide scavenger. J. Thorac. Cardiovas. Surg. 2003;125:661–668. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCALL T.B., BOUGHTON_SMITH N.K., PALMER R.M., WHITTLE B.J., MONCADA S. Synthesis of nitric oxide from L-arginine by neutrophils. Release and interaction with superoxide anion. Biochem. J. 1989;261:293–296. doi: 10.1042/bj2610293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCQUIBBAN G.A., GONG J.H., TAM E.M., MCCULLOCH C.A., CLARK_LEWIS I., OVERALL C.M. Inflammation dampened by gelatinase A cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science. 2000a;289:1202–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCQUIBBAN G.A., GONG J.H., TAM E.M., MCCULLOCH C.A., CLARK-LEWIS I., OVERALL C.M. Inflammation dampened by gelatinase A cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science. 2000b;289:1202–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERTEN M., PAKALA R., THIAGARAJAN P., BENEDICT C.R. Platelet microparticles promote platelet interaction with subendothelial matrix in a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-dependent mechanism. Circulation. 1999;99:2577–2582. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.19.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE K.L. Structure and function of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Leuk. Lymphoma. 1998;29:1–15. doi: 10.3109/10428199809058377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., RUSSEL R.J., CELLEK S., LIZASOAIN I., SU Y., DARLEY_USMAR V.M., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. cGMP mediates the vascular and platelet actions of nitric oxide: confirmation using an inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:1480–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGATA K., TSUJI T., TODOROKI N., KATAGIRI Y., TANOUE K., YAMAZAKI H., HANAI N., IRIMURA T. Activated platelets induce superoxide anion release by monocytes and neutrophils through P-selectin (CD62) J. Immunol. (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 1993;151:3267–3273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPDENAKKER G., VAN_DEN_STEEN P.E., DUBOIS B., NELISSEN I., VAN_COILLIE E., MASURE S., PROOST P., VAN_DAMME J. Gelatinase B functions as regulator and effector in leukocyte biology. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2001;69:851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASQUET J.M., TOTI F., NURDEN A.T., DACHARY_PRIGENT J. Procoagulant activity and active calpain in platelet-derived microparticles. Thromb. Res. 1996;82:509–522. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEI D. Leukolysin/MMP25/MT6-MMP: a novel matrix metalloproteinase specifically expressed in the leukocyte lineage. Cell Res. 1999;9:291–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI A., JURASZ P., SANDERS E.J., OVERALL C.M., BIGG H.F., EDWARDS D.R., RADOMSKI M.W. Identification, regulation and role of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-4 (TIMP-4) in human platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:1330–1338. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI A., SAWICKI G., OLSON D.M., RADOMSKI M.W. The role of nitric oxide and metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of hyperoxia-induced lung injury in newborn rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1455–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI A., STEWART M.W., JURASZ P., RADOMSKI M.W. Pharmacological characteristics of solid-phase von Willebrand factor in human platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1013–1020. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M., MONCADA S. An improved method for washing of human platelets with prostacyclin. Thromb. Res. 1983;30:383–389. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(83)90230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. The anti-aggregating properties of vascular endothelium: interactions between prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987a;92:639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. Comparative pharmacology of endothelium-derived relaxing factor, nitric oxide and prostacyclin in platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987b;92:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. Characterization of the L-arginine:nitric oxide pathway in human platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990a;101:325–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. An L-arginine/nitric oxide pathway present in human platelets regulates aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990b;87:5193–5197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., REES D.D., DUTRA A., MONCADA S. S-nitroso-glutathione inhibits platelet activation in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:745–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTOSO S., SACHS U.J., KROLL H., LINDER M., RUF A., PREISSNER K.T., CHAVAKIS T. The junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM-3) on human platelets is a counterreceptor for the leukocyte integrin Mac-1. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:679–691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI G., RADOMSKI M.W., WINKLER_LOWEN B., KRZYMIEN A., GUILBERT L.J. Polarized release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 from cultured human placental syncytiotrophoblasts. Biol. Reprod. 2000;63:1390–1395. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI G., SALAS E., MURAT J., MISZTA_LANE H., RADOMSKI M.W. Release of gelatinase A during platelet activation mediates aggregation. Nature. 1997;386:616–619. doi: 10.1038/386616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI G., SANDERS E.J., SALAS E., WOZNIAK M., RODRIGO J., RADOMSKI M.W. Localization and translocation of MMP-2 during aggregation of human platelets. Thromb. Haemostasis. 1998;80:836–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMON D.I., CHEN Z., XU H., LI C.Q., DONG J., MCINTIRE L.V., BALLANTYNE C.M., ZHANG L., FURMAN M.I., BERNDT M.C., LOPEZ J.A. Platelet glycoprotein ibalpha is a counterreceptor for the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:193–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRICKER T.P., DUMIN J.A., DICKESON S.K., CHUNG L., NAGASE H., PARKS W.C., SANTORO S.A. Structural analysis of the alpha(2) integrin I domain/procollagenase-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-1) interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29375–29381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UPADHYA G.A., STRASBERG S.M. Platelet adherence to isolated rat hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells after cold preservation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1764–1770. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DEN STEEN P.E., PROOST P., WUYTS A., VAN DAMME J., OPDENAKKER G. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood. 2000;96:2673–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DEN STEEN P.E., WUYTS A., HUSSON S.J., PROOST P., VAN DAMME J., OPDENAKKER G. Gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil collagenase/MMP-8 process the chemokines human GCP-2/CXCL6, ENA-78/CXCL5 and mouse GCP-2/LIX and modulate their physiological activities. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:3739–3749. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VASSALLO R.R., KIEBER_EMMONS T., CICHOWSKI K., BRASS L.F. Structure–function relationships in the activation of platelet thrombin receptors by receptor-derived peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:6081–6085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER C., SPRINGER T.A. Neutrophil accumulation on activated, surface-adherent platelets in flow is mediated by interaction of Mac-1 with fibrinogen bound to alphaIIbbeta3 and stimulated by platelet-activating factor. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2085–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI119742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOESSNER J.F., JR Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition: from the Jurassic to the Third Millennium. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1999;878:388–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]