Abstract

We investigated the effects of grapefruit juice (GFJ) and orange juice (OJ) on drug transport by MDR1 P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2), which are efflux transporters expressed in human small intestine.

We examined the transcellular transport and uptake of [3H]vinblastine (VBL) and [14C]saquinavir in a human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) and in porcine kidney epithelial cell lines transfected with human MDR1 cDNA and human MRP2 cDNA, LLC-GA5-COL150, and LLC-MRP2, respectively.

In Caco-2 cells, the basal-to-apical transports of [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir were greater than those in the opposite direction. The ratio of basal-to-apical transport to apical-to-basal transport of [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir by Caco-2 cells was reduced in the presence of MK571 (MRPs inhibitor), verapamil (P-gp inhibitor), cyclosporin A (inhibitor of both), 50% ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, or their components (6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin, bergamottin, tangeretin, hepatomethoxyflavone, and nobiletin).

Studies of transport and uptake of [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir with MDR1 and MRP2 transfectants showed that VBL and saquinavir are transported by both P-gp and MRP2. GFJ and OJ components inhibited the transport by MRP2 as well as P-gp. However, their inhibitory potencies for P-gp or MRP2 were substrate-dependent.

The present study has revealed that GFJ and OJ interact with not only P-gp but also MRP2, both of which are expressed at apical membranes and limit the apical-to-basal transport of VBL and saquinavir in Caco-2 cells.

Keywords: P-glycoprotein, MDR1, MRP2, transport, grapefruit juice, orange juice, furanocoumarins, polymethoxyflavones, vinblastine, saquinavir

Introduction

The intestinal epithelium acts as a barrier between the lumen of the intestine and the systemic circulation, and restricts the absorption of drugs from the gastrointestinal tract. In particular, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a drug efflux pump, and cytochrome P450-3A4 (CYP3A4), a drug-metabolizing enzyme, have been shown to limit the intestinal absorption of a variety of drugs (Watkins, 1997; Wacher et al., 1998). P-gp is one of the ABC-transporter superfamily, and is constitutively expressed on the apical membranes of intestinal epithelial cells (Cordon-Cardo et al., 1990). It plays a crucial role in restricting xenobiotic absorption by extruding its substrates from the cells into the intestinal lumen. Multidrug resistance protein (MRP) 2, a member of the MRP subfamily, has also been reported to be expressed in human small intestine (Kool et al., 1997). MRP2 is an organic anion transporter, which excretes xenobiotics from the cells (Borst et al., 2000). However, it remains unclear whether MRP2 influences the intestinal drug permeability.

It is well known that grapefruit juice (GFJ) affects the pharmacokinetics of a wide variety of drugs (Bailey et al., 1991; Kupferschmidt et al., 1995). This interaction has been attributed to irreversible inhibition of CYP3A4 in the small intestine by components of the juice (Guengerich & Kim, 1990; Miniscalco et al., 1992; Ha et al., 1995). However, we have shown that GFJ components also inhibit P-gp-mediated drug efflux in a human colon carcinoma cell line, Caco-2 cells (Takanaga et al., 1998). We established that the GFJ components 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin (DHBG), bergamottin (BG), and other furanocoumarin derivatives potently inhibit P-gp function (Ohnishi et al., 2000). The steady-state uptake of [3H]vinblastine (VBL) in Caco-2 cells was increased similarly by 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ and 20 μM CysA, but the increase in the steady-state uptake of [3H]VBL by 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ in MDR1-transfected cells was lower than that by 20 μM CysA (Ohnishi et al., 2000). These results suggested that other efflux transporter(s) are involved in the efflux of [3H]VBL in Caco-2 cells. We have also shown that orange juice (OJ) and its components, tangeretin (TAN), 3,3′,4′,5,6,7,8-heptamethoxyflavone (HMF), and nobiletin (NBL) inhibit P-gp, but not CYP3A4 (Ohnishi et al., 2000).

The aim of this study is to examine the effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ and their components on the drug transport by P-gp and MRP2. As model drugs, we used VBL, a common substrate of P-gp and MRP2, and saquinavir, which has quite low bioavailability.

Methods

Materials

[3H]VBL sulfate (9.6 mCi mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham International (Buckinghamshire, U.K.). [14C]Saquinavir was kindly supplied by Roche Products Limited (London, U.K.). GFJ and OJ were commercial products of the Dole Food Company Inc. (U.S.A). BG was purchased from Indofine Chemical Co., Inc. (Someyville, NJ, U.S.A.). TAN was obtained from Extrasynthese (Genay, France). NBL was a kind gift from Kanebo (Tokyo, Japan). Verapamil (VER) was purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Cyclosporin A (CysA) was a kind gift from Novartis Pharma Inc. (Basel, Switzerland). MK571 was obtained from BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Inc. (PA, U.S.A.). Probenecid and sulfinpyrazone were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). All other chemicals used in the experiments were commercial products of reagent grade.

Preparation of the 50% ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ

Extraction of various components from GFJ and OJ was performed as we reported previously (Takanaga et al., 1998; 2000). GFJ or OJ (200 ml) was mixed with 600 ml of ethyl acetate and shaken vigorously for 10 min. After removal of the aqueous phase, the organic layer was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in 10 ml of methanol and stored at −20°C. For experiments, the methanol was evaporated under a nitrogen stream and the residue was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with buffer to give a final concentration of 50% of juice. The DMSO concentration was 0.5%.

Extraction of DHBG and HMF

DHBG and HMF were extracted and purified from GFJ and Aurantii pericarpium, which is the peel of Citrus aurantium var. daidai.

GFJ was extracted with ethyl acetate, and the organic layer was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in water and applied to a Cosmosil 75C18-OPN column (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Elution with 40, 50, 60, and 70% methanol afforded four fractions. The components in each fraction were checked by TLC analysis (Silica gel 60, F254, Merck) developed with hexane-acetone. The major fraction containing most DHBG was subjected to further separation on a silica gel column (Silica gel 60, Merck) eluted with hexane-acetone (5 : 1, 3 : 1, and 1 : 1) and chloroform-methanol (1 : 1). The eluate was separated into about 18 fractions, which were evaporated to dryness, and each residue was checked by TLC analysis. The fractions containing DHBG were mixed and subjected to further separation on Cosmosil 75C18-OPN column. Elution with 40, 50, and 60% methanol afforded 18 fractions. The fraction containing DHBG was identified in 60% methanol fraction by TLC, and evaporated to dryness. The residue was confirmed to be DHBG by HPLC and 1H-NMR spectroscopy, as described previously (Ohnishi et al., 2000).

A. pericarpium was extracted with acetone, and the organic layer was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in methanol, and applied to a silica gel column eluted with hexane-acetone (4 : 1, 3 : 1) and chloroform-methanol (1 : 1). The eluate was separated into two fractions. The components in each fraction were checked by TLC analysis developed with hexane-acetone. The major fraction containing most HMF was subjected to further separation on a silica gel column eluted with hexane-acetone (4 : 1, 3 : 1). The eluate was separated into six fractions, and each fraction was checked by TLC analysis. The major fraction containing most HMF was subjected to further separation on an MCI column (Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Elution with 70, 80, and 90% methanol afforded three fractions. The fraction containing HMF was recrystallized and separated again on a Cosmosil 75C18-OPN column with 40–90% methanol to afford four fractions. The appropriate fraction was separated on an MCI column with 70–90% methanol to give two fractions. The fraction containing HMF was evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified to homogeneity and the product was confirmed to be HMF by 1H-NMR spectroscopy as described previously (Takanaga et al., 2000).

Cell culture

Caco-2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U ml−1 penicillin G, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. All cells in this study were between passage 55 and 60. P-gp of about 170 kDa was detected in Caco-2 cells (data not shown). MRP2 of about 190 kDa was also detected in Caco-2 cells as well as in LLC-MRP2 cells (positive control), but not in LLC-pCI cells (negative control) (data not shown). Apical localization of both P-gp and MRP2 was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence with C219 (TFB Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and MRP2 III-6 (Monosan, Netherlands), respectively, in photomicrographs of horizontal sections of a Caco-2 monolayer obtained by means of confocal laser-scanning imaging (data not shown). These results are consistent with previous reports (Hunter et al., 1993, Bock et al., 2000).

LLC-PK1 cells (porcine kidney epithelial cell line) and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (a transformant cell line derived by transfecting LLC-PK1 with human MDR1 cDNA isolated from normal adrenal gland) were obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Ibaraki, Japan). LLC-PK1 cells were grown in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. LLC-GA5-COL150 cell line was obtained by selection with 150 ng ml−1 colchicine and cultured in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air, as reported previously (Ueda et al., 1992; Tanigawara et al., 1992). LLC-pCI (a transformant cell line derived by transfecting LLC-PK1 with empty vector alone) and LLC-MRP2 cells (a transformant cell line derived by transfecting LLC-PK1 with human MRP2 cDNA) were obtained by selection with 800 μg ml−1 G418 and cultured in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air, as reported previously (Kawabe et al., 1999). In LLC-GA5-COL150 and LLC-MRP2 cells, P-gp and MRP2 are located at the apical membrane (Tanigawara et al., 1992; Kawabe et al., 1999).

Transcellular transport study with Caco-2 cells

All transport and uptake experiments were performed as described in the previous report (Tsuji et al., 1994). The cells were seeded at 6.3 × 104 cells well−1 on a polycarbonate membrane (3.0 μm pore size) TranswellTM cluster (Corning Coster Japan, Japan) for 19–22 days and cultured to confluence. The transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was monitored prior to the experiment with a Millicell ERS meter (Millipore Corp., MA, U.S.A.). The cell inserts with TEER values >350 Ω cm2 were used. The transport of mannitol was used as a paracellular marker. The buffer on the apical side was adjusted to pH 6.5 at 37°C (HBSS-MES: 136.7 mM NaCl, 5.36 mM KCl, 0.952 mM CaCl2, 0.812 mM MgSO4, 0.441 mM KH2PO4, 0.385 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM D-glucose, 10 mM MES; 0.5 ml). The buffer on the basal side was adjusted to pH 7.3 at 37°C (HBSS-HEPES: 136.7 mM NaCl, 5.36 mM KCl, 0.952 mM CaCl2, 0.812 mM MgSO4, 0.441 mM KH2PO4, 0.385 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM D-glucose, 10 mM HEPES; 1.5 ml). For the transport experiments, Caco-2 cells were washed three times with the above-mentioned buffer. Transport buffer was added to the receiver side. [3H]VBL (100 nM) and [14C]mannitol (826 nM), or [14C]saquinavir (5 μM) were added to the donor side and the cells were incubated at 37°C. An inhibitor, ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, that of OJ, or one of their components, was added to both sides. At 45, 90, 135, and 180 h after the start of incubation, 0.5 ml of the basal or 0.2 ml of the apical side solution was sampled from the receiver side, and an equivalent volume of transport buffer was added as a replacement. After the transport study, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold transport buffer. The filters with monolayers were detached from the inserts, then the cells on the filters were solubilized with 0.4 ml of 1 M NaOH, and the solution was neutralized with 0.4 ml of 1 M HCl. The amount of protein in the cells was measured by Lowry's method (Lowry et al., 1951) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

The transport of [3H]VBL, [14C]mannitol, and [14C]saquinavir was quantified by adding scintillation fluid (Clearsol I, Nakarai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), and the radioactivity was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (LC6500, Beckman Instrument, Inc., CA, U.S.A).

The transcellular transport was expressed as the ratio of the transported amount per cellular protein (μl mg−1 protein) to the initial drug concentration on the donor side. The real permeability coefficient (Ptrans) was calculated by using the following equations:

Transport from apical to basal side:

Transport from basal to apical side:  where Papp and Pfilter are the apparent permeability coefficients (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) estimated in the transport study in the presence and absence of Caco-2 cells, respectively. The apparent permeability coefficient is the slope obtained from the linear portion of the transport–time plot. In order to estimate inhibitory potency on cellular transport to the apical side, the ratio of Ptrans (B-to-A) to Ptrans the (A-to-B) (Ptrans ratio) was compared in the presence or absence of the inhibitor.

where Papp and Pfilter are the apparent permeability coefficients (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) estimated in the transport study in the presence and absence of Caco-2 cells, respectively. The apparent permeability coefficient is the slope obtained from the linear portion of the transport–time plot. In order to estimate inhibitory potency on cellular transport to the apical side, the ratio of Ptrans (B-to-A) to Ptrans the (A-to-B) (Ptrans ratio) was compared in the presence or absence of the inhibitor.

For experiments containing extracts, osmolarity was between 320 and 430 mOsm (OM802, Vogel, Berlin, German), and the osmolarity in the control study was adjusted by adding mannitol.

Transcellular transport study with MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants

LLC-PK1, LLC-GA5-COL150, LLC-pCI, and LLC-MRP2 cells were seeded on a polycarbonate membrane (3.0 μm pore size) TranswellTM cluster (Corning Coster Japan, Japan) at 4 × 105, 5 × 105, 4 × 105, and 5 × 105 cells well−1, respectively. The cells were grown for 3 days and the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, without colchicine and G418, 6 h before the transport experiments. For the experiments, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed once or twice with transport buffer: (141 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37°C). The transport buffer was added to the receiver side. [3H]VBL (100 nM) or [14C]saquinavir (5 μM) was added to the donor side. Assay of radiolabeled compounds, measurement of protein in cells, and measurement of the transport of [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir were performed as described above.

Uptake study with MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants

Cells were seeded on four-well multidishes (Nunc, Denmark) at a cell density of 4 × 104, 8 × 104, 2 × 104, and 4 × 104 cells well−1 for LLC-PK1, LLC-GA5-COL150 cells, LLC-pCI, and LLC-MRP2, respectively. The cells were grown for 3 days and the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, without colchicine and G418, 6 h before the uptake experiments. For the experiments, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with the transport buffer (141 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37°C). Uptake experiments were performed in 250 μl of incubation buffer containing 20 nM [3H]VBL or 5 μM [14C]saquinavir in the presence or absence of an inhibitor, ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, that of OJ, or one of their components. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold buffer to stop the uptake. After the uptake experiments, the cells were dissolved in 3M NaOH (200 μl) and neutralized with 6 M HCl (100 μl). Assay of radiolabeled compounds, measurement of protein in cells, and measurement of the transport of [3H]VBL or [14C]saquinavir were performed as described above.

The uptake of [3H]VBL or [14C]saquinavir is presented as cell/medium ratio (μl mg−1 protein). Cell/medium ratio was obtained by dividing the uptake amount by the cellular protein amount (dpm mg−1 protein) by the initial drug concentration in the uptake buffer (dpm μl−1). To examine the effects of various compounds on steady-state uptake, we incubated the cells for 90 min. In order to estimate the inhibitory potency on cell to apical side transport, the uptake potentiation ratio was calculated by using the following equations:

Uptake potentiation ratio

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. The significance of differences between groups and control was evaluated by using Student's t-test or ANOVA, followed by Scheffe's test. Differences between means were considered to be significant when the P-value was less than 0.05.

Results

Effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ and their components, and Cys A, VER, and MK571 on the transcellular transport of [3H]VBL across Caco-2 cells

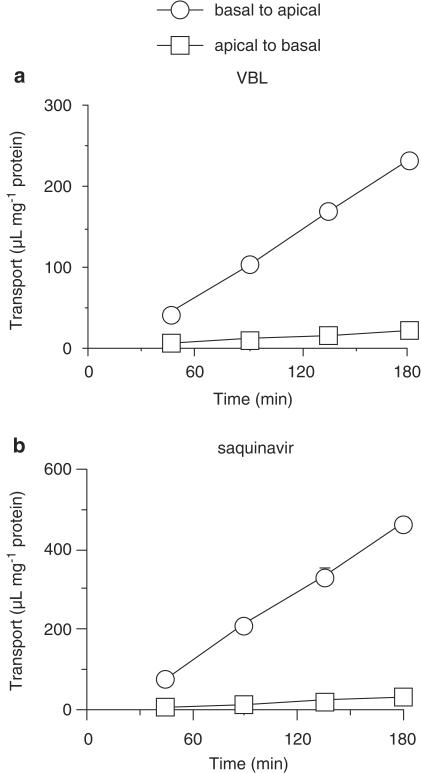

The basal-to-apical transport of [3H]VBL was markedly higher than that in the opposite direction across Caco-2 cells (Figure 1a). Table 1 shows the effects of inhibitors of each transporter, GFJ, and OJ. MK571 (50 μM), VER (100 μM) and CysA (20 μM), decreased the Ptrans ratio to 28, 50, and 21% of the control, respectively. The Ptrans ratio was reduced to 14, 35 or 42% of the control in the presence of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, DHBG or BG, respectively. The Ptrans ratio was reduced to 29, 30, 30 or 31% of the control in the presence of the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, TAN, HMF or NBL, respectively. The permeability coefficient of mannitol, a paracellular marker, was not affected by any of the inhibitors tested (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Transcellular transport of 100 nM [3H]VBL (panel a) and 5 μM [14C]saquinavir (panel b) across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Basal-to-apical transport (circles) and apical-to-basal transport (squares) were investigated at 37°C in apical buffer containing HBSS-MES (pH 6.5) and basal buffer containing HBSS-HEPES (pH 7.4). Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments.

Table 1.

Effects of inhibitors of P-gp and/or MRP2, ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ and various components of GRJ and OJ on the transport of 100 nM [3H] vinblastine across Caco-2 cells

| Ptrans (A-to-B) (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) | Ptrans (B-to-A) (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) | Ptrans ratio (Ptrans (B-to-A)/Ptrans (A-to-B) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.12±0.001 (100) | 1.55±0.034 (100) | 13.01±0.14 (100) |

| +50 μM MK571 | 0.33±0.017** (275) | 1.20±0.045* (78) | 3.59±0.13** (28) |

| +100 μM verapamil) | 0.25±0.003** (208) | 1.59±0.048 (103) | 6.45±0.22 (50) |

| +20 μM cyclosporin A | 0.34±0.006** (283) | 0.93±0.043** (60) | 2.76±0.16** (21) |

| +50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ | 0.32±0.016** (267) | 0.58±0.026** (38) | 1.84±0.04 (14) |

| +20 μM 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin | 0.30±0.003** (250) | 1.38±0.030 (89) | 4.61±0.07 (35) |

| +10 μM bergamottin | 0.21±0.009** (175) | 1.14±0.104** (74) | 5.41±0.29** (42) |

| +50% ethyl acetate extract of OJ | 0.28±0.005** (233) | 1.05±0.027** (68) | 3.72±0.03** (29) |

| +20 μM tangeretin | 0.31±0.006** (259) | 1.21±0.032* (78) | 3.89±0.14** (30) |

| +20 μM heptamethoxyflavone | 0.29±0.010** (233) | 1.11±0.036* (72) | 3.88±0.02** (30) |

| +20 μM nobiletin | 0.23±0.016** (229) | 0.10±0.042* (71) | 4.00±0.08** (31) |

Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from three experiments. The significances of differences from the control was determined by ANOVA, followed by Scheffe's test (*P<0 05, **P< 0.0001).

Effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, their components, Cys A, VER, and MK571, on the transcellular transport of [14C]saquinavir across Caco-2 cells

The basal-to-apical transport of [14C]saquinavir was markedly higher than that in the opposite direction across Caco-2 cells (Figure 1b). Table 2 shows the effects of inhibitors of each transporter, GFJ, and OJ. In the presence of 50 μM MK571, 100 μM VER or 20 μM Cys A, the Ptrans ratio was decreased to 38, 26 or 18% of the control, respectively. The Ptrans ratio were reduced to 14, 43 and 67% of the control by the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, DHBG, and BG, respectively. The Ptrans ratio was reduced to 31, 33, 32 or 32% of the control by the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, TAN, HMF or NBL, respectively.

Table 2.

Effects of inhibitors of P-gp and/or HRP2, ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, and various components of GFJ and OJ on the transport of 5 μM [14C]saquinavir across Caco-2 cells

| Ptrans (A-to-B) (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) | Ptrans (B-to-A) (μl min−1 mg−1 protein) | Ptrans ratio Ptrans (B-to-A) Ptrans (A-to-B) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.18±0.013 (100) | 3.88±0.029 (100) | 19.00±1.61 (100) |

| +50 μM MK571 | 0.54±0.003** (295) | 4.00±0.131 (103) | 7.30±0.28** (38) |

| +100 μM verapamil | 0.65±0.021** (352) | 3.19±0.087* (82) | 4.92±0.06** (26) |

| +20 μM cyclosporin A | 0.72±0.023** (391) | 2.46±0.048** (63) | 3.34±0.08** (18) |

| +50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ | 0.55±0.017** (296) | 1.42±0.043** (37) | 2.60±0.01** (14) |

| +20 μM 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin | 0.37±0.009* (199) | 2.98±0.096* (77) | 8.14±0.21** (43) |

| +10 μM bergamottin | 0.36±0.020* (198) | 4.62±0.220 (119) | 12.81±1.23** (67) |

| +50% ethyl acetate extract of OJ | 0.38±0.022* (207) | 2.25±0.049** (58) | 5.93±0.31** (31) |

| +20 μM tangeretin | 0.47±0.020** (257) | 2.94±0.116* (76) | 6.27±0.49** (33) |

| +20 μM heptamethoxyflavone | 0.40±0.080** (216) | 2.44±0.071** (63) | 6.13±0.28** (32) |

| +20 μM nobiletin | 0.40±0.013** (217) | 2.44±0.052** (63) | 6.11±0.25** (32) |

Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from three experiments. The significance of differences from the control was determined by ANOVA followed by Scheffe's test (*P<0.05, **P<0.0001).

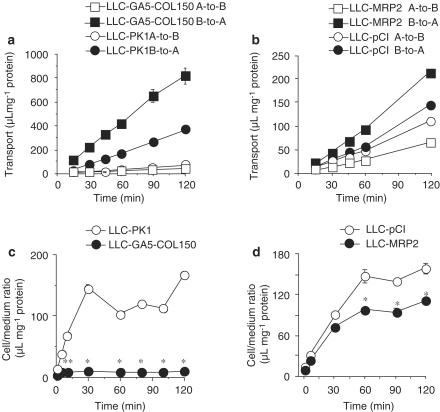

Transcellular transport and uptake of [3H]VBL by MDR1 and MRP2 transfectants

The basal-to-apical transport of [3H]VBL by LLC-GA5-COL150 cells was higher than that by LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 2a). The uptake of [3H]VBL by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells increased with time and reached a steady state at 30 min (Figure 2c). The steady-state uptake of [3H]VBL in LLC-GA5-COL150 cells was significantly lower than that of LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 2c). Similarly, the apical-to-basal transport and basal-to-apical transport of [3H]VBL by LLC-MRP2 cells were lower and higher, respectively, than those by LLC-pCI cells (Figure 2b). As shown in Figure 3d, the uptake of [3H]VBL by LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells increased with time and reached a steady state at 60 min. The steady-state uptake of [3H]VBL in LLC-MRP2 cells was significantly lower than that of LLC-pCI cells (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Transport of [3H]VBL by P-gp and MRP2. (a, b) Transcellular transport of 100 nM [3H]VBL by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (a), or LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells (b). (c, d) Uptake of 20 nM [3H]VBL by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (c), or LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells (d). LLC-GA5-COL150 cells are a transformant cell line derived by transfecting LLC-PK1 with human MDR1 cDNA and they overexpress P-gp. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments. Significant differences from corresponding control cells were identified by using Student's t-test (*P<0.05).

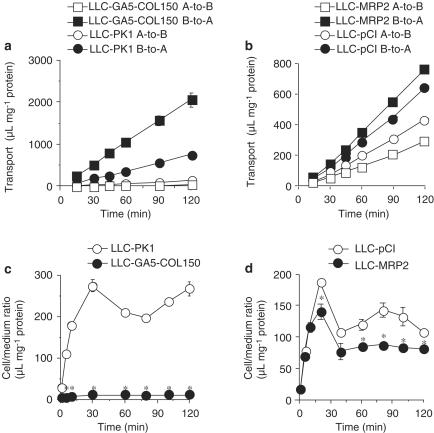

Figure 3.

Transport of [14C]saquinavir by P-gp and MRP2. (a, b) Transcellular transport of 5 μM [14C]saquinavir by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (a), or LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells (b). (c, d) Uptake of 5 μM [14C]saquinavir by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (c), or LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells (d). LLC-GA5-COL150 cells are a transformant cell line derived by transfecting LLC-PK1 with human MDR1 cDNA and they overexpress P-gp. Each point represents the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments. Significant differences from corresponding control cells were identified by using Student's t-test (*P<0.05).

Effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, and their components on the uptake of [3H]VBL in MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants

The effects of inhibitors of P-gp (Cys A and VER) and MRP (Cys A, MK571, probenecid, and sulfinpyrazone), the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, DHBG, BG, the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, TAN, HMF, and NBL on the uptake of [3H]VBL for 90 min by MDR1 transfectants, MRP2 transfectants and control cells were examined. The inhibitory potencies for P-gp and MRP2 were compared in terms of the ‘uptake potentiation ratio'. The uptake potentiation ratios of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, TAN, HMF, and NBL for P-gp were 153, 165, 178, 157, and 216%, respectively (Table 3). In the presence of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, BG, and NBL, the uptake potentiation ratios for MRP2 were 151, 118, 116 and 128%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of inhibitors of P-gp and/or MRP, ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, and various components of GFJ and OJ on the P-gp or MRP2-mediated efflux of [3H]vinblastine and [14C]saquinavir

| P-gp | MRP2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake potentiation ratio (%)a | Uptake potentiation ratio (%)b | ||||

| Vinblastine | Saquinavir | Vinblastine | Saquinavir | ||

| Verapamil | (100 μM) | 168±1.1* | 946±5.5 | 83.6±5.7 | 122±2.7* |

| Cyclosporin A | (20 μM) | 396±1.0* | 380±24* | 150±5.l* | 217±5.0* |

| MK571 | (50 μM) | 49.0±1.9 | 80.8±3.8 | 153±5.7* | 143±4.8* |

| Sulfinpyrazone | (5 mM) | 40.5±1.7 | 82.3±11 | 143±8.2* | 153±3.l* |

| Probenecid | (5 mM) | 56.7±1.0 | 111±9.3 | 135±1.8* | 137±3.1* |

| 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ | 153±9.9* | 284±32* | 151±7.6* | 180±9.0* | |

| 6′,7′-dihydroxybergiamottin | (20 μM) | 114±3.1* | 338±24* | 89.0±5.3 | 113±3.1 |

| Bergamottin | (20 μM) | 56.9±4.6 | 159±5.5* | 116±4.3* | 108±11 |

| 50% ethyl acetate extract of OJ | 165±4.9* | 106±11 | 118±6.3* | 173±2.0* | |

| Tangeretin | (20 μM) | 178±3.2* | 146±14* | 108±2.0 | 147±2.8* |

| Heptamethoxyflavone | (20 μM) | 157±2.7* | 128±2.8* | 105±3.3 | 131±6.4* |

| Nobiletin | (20 μM) | 216±8.1* | 101±1.4 | 128±1.9* | 162±9.l* |

Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from three experiments.

Mean values of increase ratio of uptake in the presence of inhibitor to absence were calculated and compared between with LLC-PKl and LLC-GA5-COL150, or LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 using Student's t-test (P<0.05).

Transcellular transport and uptake of [14C]saquinavir by MDR1 and MRP2 transfectants

The basal-to-apical transport of [14C]saquinavir by LLC-GA5-COL150 cells was higher than that by LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 3a). Further, the uptake of [14C]saquinavir by LLC-PK1 and LLC-GA5-COL150 cells increased with time and reached a steady state at 30 min. The steady-state uptake of [14C]saquinavir in LLC-GA5-COL150 cells was significantly lower than that in LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 3c). Similarly, LLC-MRP2 cells showed greater basal-to-apical transport and smaller apical-to-basal transport of [14C]saquinavir in comparison to LLC-pCI cells (Figure 3b). As shown in Figure 3d, the uptake of [14C]saquinavir by LLC-pCI and LLC-MRP2 cells increased with time and reached a steady state at 40 min. The steady-state uptake of [14C]saquinavir in LLC-MRP2 cells was significantly lower than that in LLC-pCI cells.

Effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ, and their components on the uptake of [14C]saquinavir in MDR1 and MRP2 transfectants

The effects of inhibitors of P-gp and MRP, the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, DHBG, BG, the ethyl acetate extract of OJ, TAN, HMF, and NBL on the uptake of [14C]saquinavir for 90 min by MDR1 transfectants, MRP2 transfectants, and each control cell were examined. The uptake potentiation ratios of GFJ and DHBG for P-gp were 284 and 338%, respectively (Table 3). In the presence of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, OJ, TAN, HMF or NBL, the uptake potentiation ratio in LLC-MRP2 was 180, 173, 147, 131 or 162%, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

The aim of this study is to examine the contribution of MRP2 to drug efflux in Caco-2 cells, and the effects of the ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ and OJ and their components on the drug transport by P-gp and MRP2.

We demonstrated using LLC-GA5-COL150 and LLC-MRP2 cells that [3H]VBL is transported by both P-gp and MRP2. This is also consistent with previous reports on transcellular transport in LLC-GA5-COL150 cells (Tanigawara et al., 1992) and human MRP2 cDNA transfectants, MDCKII-MRP2 cells (Evers et al., 1998). In Caco-2 cells, the transcellular transport of [3H]VBL was inhibited by P-gp inhibitors (VER and Cys A) and MRP inhibitors (MK571 and Cys A), suggesting that MRP2, as well as P-gp, contributes to the transport of [3H]VBL. MK571 did not inhibit P-gp, but did inhibit MRP2. MK571 also inhibits MRP1 (Gekeler et al., 1995), and may inhibit other MRP family members. However, to our knowledge MRP2 is the only member of this family that is known to be expressed at the apical site of epithelial cells such as Caco-2 cells and intestinal epithelium (Bock et al., 2000). Therefore, we conclude that MRP2, as well as P-gp, contributes to the transport of [3H]VBL in Caco-2 cells.

We confirmed that [14C]saquinavir, which has limited bioavailability, is transported by both P-gp and MRP2 by means of transport studies and uptake studies using MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants. In accordance with our results, P-gp has been shown to transport saquinavir in a study using MDR1 transfectants (Lee et al., 1998). Gutmann et al. (1999) suggested that MRP2 may transport saquinavir based on a transport study using fluoresceinated saquinavir and leukotriene C4, a potent inhibitor of MRP, in killifish renal proximal tubules expressing P-gp and MRP2. Recently, Williams et al. (2002) and Huisman et al. (2002) demonstrated MRP2-mediated transport of saquinavir by the use of polarized epithelial canine cells transfected with MRP2 cDNA. Our results are consistent with these reports. Furthermore, the fact that the transcellular transport of [14C]saquinavir across Caco-2 cells was inhibited by P-gp inhibitors (VER and Cys A) and MRP inhibitors (MK571 and Cys A), suggests contributions of both transporters to saquinavir efflux in Caco-2 cells.

The basal-to-apical transport of both [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir across Caco-2 cells was significantly decreased by the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ as well as by 20 μM Cys A, an inhibitor of P-gp and MRP. The ethyl acetate extracts of GFJ inhibited not only P-gp, but also MRP2. Therefore, it is likely that the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ reduces the transport of [3H]VBL and [14C]saquinavir across Caco-2 cells by inhibiting both P-gp and MRP2.

In agreement with a previous uptake study (Ohnishi et al., 2000), the inhibitory potencies of GFJ components, 20 μM DHBG and 10 μM BG, on the transport of [3H]VBL in Caco-2 cells were lower than that of the 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ. Similar results were obtained in the uptake study of [3H]VBL using MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants. The concentrations of DHBG and BG in the 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ are reported to be 6.38 and 0.99 μM (Ohnishi et al., 2000), respectively, being lower than the concentrations used in the present study. Our data are consistent with previous reports showing that P-gp was inhibited by BG and DHBG (Eagling et al., 1999, Wang et al., 2001). However, if the effects of DHBG and BG are simply additive, the inhibitory effect of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ on the efflux of [3H]VBL via P-gp and MRP2 cannot be attributed wholly to DHBG and BG. A furanocoumarin dimer, FC726, is contained in the 50% ethyl acetate extract of GFJ at a concentration of 7.75 μM and inhibits the efflux of [3H]VBL in Caco-2 cells two-fold more potently than DHBG or BG (Ohnishi et al., 2000). Therefore, FC726 may contribute to the inhibitory effect of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ on P-gp and MRP2. Further study on the combined effects of furanocoumarins will be necessary to establish whether other components are involved in the inhibitory effects of GFJ.

The selectivity of the inhibitory effects of juice components is summarized in Table 4, based on the results of uptake studies with MDR1 transfectants and MRP2 transfectants and our previous reports concerning effects on CYP3A4 (Ohnishi et al., 2000, Takanaga et al., 2000,). Interestingly, the selectivity of the ethyl acetate extract of GFJ, that of OJ and their components towards P-gp and MRP2 is clearly substrate-dependent. If substrates and inhibitors bind to a transporter at the same site, the rank order of inhibitory potencies on transport of any substrate via the transporter would be the same as that for any other substrate. Cys A and NBL, which inhibit saquinavir transport mediated by MRP2, did not affect the transport of VBL mediated by MRP2. This could be explained by a higher affinity of VBL for MRP2 than that of saquinavir. The efflux of saquinavir by P-gp was inhibited potently by Cys A and DHBG, but was not affected by VER or NBL. On the other hand, VER and NBL inhibited the efflux of VBL by P-gp and the effect of DHBG on the efflux by P-gp was lower than that of Cys A. These findings cannot be explained only by a difference of affinity between VBL and saquinavir. This apparent conflict may possibly be explained by differences among substrates in the binding mode to P-gp. Indeed, P-gp has been demonstrated to possess multiple binding sites for substrates (Doppenschmitt et al., 1999). Another possible explanation is that there are distinct binding sites for substrates and inhibitors, and the allosteric effect on the binding site for inhibitors is dependent on the substrate. Further research on these possibilities is in progress.

Table 4.

Inhibitory effects of various compounds on CYP3A4, P-gp and MRP2 functions

| CYP3A4a | P-gpb | MRP2b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinblastine | Saquinavir | Vinblastine | Saquinavir | ||

| MK571 | ND | − | − | + | + |

| Verapamil | ND | ++ | − | − | − |

| Cyclosporin A | ND | +++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| Ethyl acetate extract of GFJ | ND | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin | + | − | +++ | − | − |

| Bergamottin | + | − | + | − | − |

| Ethyl acetate extract of OJ | ND | ++ | − | − | ++ |

| Tangeretin | − | ++ | + | − | + |

| Heptamethoxyflavone | − | + | − | − | + |

| Nobilein | − | +++ | − | − | ++ |

+, inhibitory effects on the activity of testosterone 6 β-hydroxylation by human microsomal P450 3A4. +, <50% of control at 10 μM. (Ohnishi et al., 2000; Takanaga et al., 2000).

+, the extent of the uptake potentiation ratio.

+, > 130%; ++, > 160%; +++, > 200%.

ND, not determined.

In conclusion, the present study has revealed that GFJ and OJ interact with not only P-gp, but also MRP2, both of which are expressed at apical membranes and limit the apical-to-basal transport of vinblastine and saquinavir in Caco-2 cells. Therefore, MRP2, in addition to P-gp and CYP3A4, may contribute to the drug pharmacokinetic changes induced by GFJ and OJ.

Abbreviations

- BG

bergamottin

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CysA

cyclosporin A

- DHBG

6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin, 5-[(6,7-dihydroxy-6-keto-2-octenyl)oxy]psoralen

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- GFJ

grapefruit juice

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HMF

3,3′,4′,5,6,7,8-heptamethoxyflavone

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MRP2

multidrug resistance protein 2

- NBL

nobiletin, 3′,4′,5,6,7,8-hexamethoxyflavone

- OJ

orange juice

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- TAN

tangeretin, 4′,5,6,7,8-pentamethoxyflavone

- TEER

transepithelial electrical resistance

- VBL

vinblastine

- VER

verapamil

References

- BAILEY D.G., SPENCE J.D., MUNOZ C., ARNOLD J.M. Interaction of citrus juices with felodipine and nifedipine. Lancet. 1991;337:268–269. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90872-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOCK K.W., ECKLE T., OUZZINE M., FOURNEL-GIGLEUX S. Coordinate induction by antioxidants of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A6 and the apical conjugate export pump MRP2 (multidrug resistance protein 2) in Caco-2 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:467–470. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORST P., EVERS R., KOOL M., WIJNHOLDS J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORDON-CARDO C., O'BRIEN J.P., BOCCIA J., CASALS D., BERTINO J.R., MELAMED M.R. Expression of the multidrug resistance gene product (P-glycoprotein) in human normal and tumor tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1990;38:1277–1287. doi: 10.1177/38.9.1974900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOPPENSCHMITT S., LANGGUTH P., REGARDH C.G., ANDERSSON T.B., HILGENDORF C., SPAHN-LANGGUTH H. Characterization of binding properties to human P-glycoprotein: development of a [3H]verapamil radioligand-binding assay. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:348–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EAGLING V.A., PROFIT L., BACK D.J. Inhibition of the CYP3A4-mediated metabolism and P-glycoprotein-mediated transport of the HIV-1 protease inhibitor saquinavir by grapefruit juice components. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;48:543–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVERS R., KOOL M., VAN DEEMTER L., JANSSEN H., CALAFAT J., OOMEN L.C., PAULUSMA C.C., OUDE ELFERINK R.P., BAAS F., SCHINKEL A.H., BORST P. Drug export activity of the human canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in polarized kidney MDCK cells expressing cMOAT (MRP2) cDNA. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1310–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI119886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEKELER V., ISE W., SANDERS K.H., ULRICH W.R., BECK J. The leukotriene LTD4 receptor antagonist MK571 specifically modulates MRP associated multidrug resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;208:345–352. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUENGERICH F.P., KIM D.H. In vitro inhibition of dihydropyridine oxidation and aflatoxin B1 activation in human liver microsomes by naringenin and other flavonoids. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:2275–2279. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.12.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTMANN H., FRICKER G., DREWE J., TOEROEK M., MILLER D.S. Interactions of HIV protease inhibitors with ATP-dependent drug export proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:383–389. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HA H.R., CHEN J., LEUENBERGER P.M., FREIBURGHAUS A.U., FOLLATH F. In vitro inhibition of midazolam and quinidine metabolism by flavonoids. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;48:367–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00194952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUISMAN M.T., SMIT J.W., CROMMENTUYN K.M., ZELCER N., WILTSHIRE H.R., BEIJNEN J.H., SCHINKEL A.H. Multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) transports HIV protease inhibitors, and transport can be enhanced by other drugs. AIDS. 2002;16:2295–2301. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J., JEPSON M.A., TSURUO T., SIMMONS N.L., HIRST B.H. Functional expression of P-glycoprotein in apical membranes of human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Kinetics of vinblastine secretion and interaction with modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14991–14997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABE T., CHEN Z.S., WADA M., UCHIUMI T., ONO M., AKIYAMA S., KUWANO M. Enhanced transport of anticancer agents and leukotriene C4 by the human canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter (cMOAT/MRP2) FEBS Lett. 1999;456:327–331. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00979-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOOL M., DE HAAS M., SCHEFFER G.L., SCHEPER R.J., VAN EIJK M.J., JUIJN J.A., BAAS F., BORST P. Analysis of expression of cMOAT (MRP2), MRP3, MRP4, and MRP5, homologues of the multidrug resistance-associated protein gene (MRP1), in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3537–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUPFERSCHMIDT H.H., HA H.R., ZIEGLER W.H., MEIER P.J., KRAHENBUHL S. Interaction between grapefruit juice and midazolam in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;58:20–28. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE C.G., GOTTESMAN M.M., CARDARELLI C.O., RAMACHANDRA M., JEANG K.T., AMBUDKAR S.V., PASTAN I., DEY S. HIV-1 protease inhibitors are substrates for the MDR1 multidrug transporter. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3594–3601. doi: 10.1021/bi972709x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein mesurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINISCALCO A., LUNDAHL J., REGARDH C.G., EDGAR B., ERIKSSON U.G. Inhibition of dihydropyridine metabolism in rat and human liver microsomes by flavonoids found in grapefruit juice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:1195–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHNISHI A., MATSUO H., YAMADA S., TAKANAGA H., MORIMOTO S., SHOYAMA Y., OHTANI H., SAWADA Y. Effect of furanocoumarin derivatives in grapefruit juice on the uptake of vinblastine by Caco-2 cells and on the activity of cytochrome P450 3A4. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1369–1377. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANAGA H., OHNISHI A., MATSUO H., SAWADA Y. Inhibition of vinblastine efflux mediated by P-glycoprotein by grapefruit juice components in caco-2 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1998;21:1062–1066. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANAGA H., OHNISHI A., YAMADA S., MATSUO H., MORIMOTO S., SHOYAMA Y., OHTANI H., SAWADA Y. Polymethoxylated flavones in orange juice are inhibitors of P-glycoprotein but not cytochrome P450 3A4. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGAWARA Y., OKAMURA N., HIRAI M., YASUHARA M., UEDA K., KIOKA N., KOMANO T., HORI R. Transport of digoxin by human P-glycoprotein expressed in a porcine kidney epithelial cell line (LLC-PK1) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;263:840–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUJI A., TAKANAGA H., TAMAI I., TERASAKI T. Transcellular transport of benzoic acid across Caco-2 cells by a pH-dependent and carrier-mediated transport mechanism. Pharm. Res. 1994;11:30–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1018933324914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEDA K., OKAMURA N., HIRAI M., TANIGAWARA Y., SAEKI T., KIOKA N., KOMANO T., HORI R. Human P-glycoprotein transports cortisol, aldosterone, and dexamethasone, but not progesterone. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:24248–24252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WACHER V.J., SILVERMAN J.A., ZHANG Y., BENET L.Z. Role of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 3A in limiting oral absorption of peptides and peptidomimetics. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87:1322–1330. doi: 10.1021/js980082d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG E.J., CASCIANO C.N., CLEMENT R.P., JOHNSON W.W. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein transport function by grapefruit juice psoralen. Pharm. Res. 2001;18:432–438. doi: 10.1023/a:1011089924099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATKINS P.B. The barrier function of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein in the small bowel. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997;27:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS G.C., LIU A., KNIPP G., SINKO P.J. Direct evidence that saquinavir is transported by multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1) and canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter (MRP2) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3456–3462. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3456-3462.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]