Abstract

The effects of falcarindiol on the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induced by lipopolysaccharide/interferon-γ (LPS/IFN-γ) in rat primary astrocytes were investigated. The molecular mechanisms underlying falcarindiol that confers its effect on iNOS expression were also elucidated.

Falcarindiol abrogated the LPS/IFN-γ-mediated induction of iNOS by about 80%. Falcarindiol attenuated the induction of iNOS in a concentration-dependent manner.

The inhibitory effect of falcarindiol on iNOS induction was attributable to decrease in the protein content and the mRNA level of iNOS.

Treatment with 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min decreased LPS/IFN-γ-induced nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation by 32%.

Treatment with 50 μM of falcarindiol for 60 min diminished the LPS/IFN-γ-mediated activation of IκB kinase-α (IKK-α) and IKK-β by 28.2 and 29.7%, respectively.

Falcarindiol modulated the nuclear translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1) in a time-dependent manner. Falcarindiol (50 μM) decreased the tyrosine phosphorylation of janus kinase 1 (JAK1) by 84.8% at 5 min. Falcarindiol also abrogated the tyrosine phoshorylation of JAK2 by 82.3% at 10 min.

The present study demonstrates that falcarindiol attenuated the activation of IKK and JAK contributing to the blockade of activation of NF-κB and Stat1, thereby leading to the suppression of iNOS expression.

Keywords: Falcarindiol, iNOS, astrocyte, IKK, JAK

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a free radical gas involved in a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms. Inducible NO synthase (iNOS) is induced by a variety of proinflammatory cytokines and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Dawson & Dawson, 1996). In the central nervous system (CNS), iNOS is expressed mainly in activated astrocytes and microglia. High levels of NO produced via iNOS in CNS are implicated in oligodendrocyte degeneration in demyelinating diseases and neuronal death during trauma and ischemic injury (Lipton et al., 1993; Merrill et al., 1993; Mitrovic et al., 1994; Hobbs et al., 1999).

The expression of iNOS is predominantly regulated at the transcriptional level. The promoter region of murine iNOS gene contains at least 22 elements for the binding of transcription factors. These include 10 copies of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) response element (IRE); three copies of γ-activated site (GAS); two copies of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE), activating protein-1 (AP-1), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) response element; and one X box (Xie et al., 1993). Evidences have shown that NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1), and AP-1 are important for the expression of iNOS (Marks-Konczalik et al., 1998; Israel, 2000; Karin & Delhase, 2000; Dell'Albani et al., 2001).

NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by association with a member of the inhibitor family of NF-κB (IκB) (Baeuerle & Henkel, 1994; Thanos & Maniatis, 1995). The phosphorylation of IκB-α and IκB-β by IκB kinase-α (IKK-α) and IKK-β induce degradation of IκB and the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus. NF-κB binds to the binding motif in the promoters of target genes and so regulates their transcription (Israel, 2000; Karin & Delhase, 2000). IFN-γ induces Stat1 into nucleus and binding to GAS, through tyrosine phosphorylation, by janus kinase (JAK) (Gao et al., 1997; Kovarik et al., 1998). The activation of protein kinases are also involved in the expression of iNOS. These include protein kinase C-ɛ (PKCɛ), PKCη, PKCδ, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and p38 (Díaz-Guerra et al., 1996; Bhat et al., 1998; Chen et al., 1998; Carpenter et al., 2001).

Falcarindiol, one kind of polyacetylene, was isolated from either Saposhnikovia divaricata or Panax quinquefolium (Figure 1). Both S. divaricata and P. quinquefolium are widely used in Chinese medicine for anti-inflammatory purpose. Previous report has indicated that furanocoumarins, deltoin and imperatorin, are the major components contributing to the inhibitory effect of S. divaricata on NO production in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Wang et al., 1999a). However, our previous result has shown falcarindiol inhibits the nitrite production more potent than furanocoumarins (Wang et al., 2000). In an attempt to clarify the action mechanisms of falcarindiol, we therefore evaluated the effects of falcarindiol on the expression of iNOS induced by LPS/IFN-γ in rat primary astrocytes. The mechanisms by which falcarindiol confers its effect on iNOS expression have also been examined.

Figure 1.

Structure of falcarindiol.

Methods

Materials

All reagents for electrophoresis were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). Medium and materials for cell culture were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.). Radioisotope, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents, and anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Buckinghamshire, England). The recombinant rat IFN-γ was obtained from PeproTech (London, U.K.). Rabbit polyclonal antibody for iNOS was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, U.S.A.). Consensus oligonucleotide (for NF-κB, AP-1, and ISRE/GSA), rabbit polyclonal antibodies (for IκB-α, IκB-β, IKK-α, and IKK-β), and GST-IκB-α fusion protein were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Rabbit anti-phospho-JAK1, JAK1, and JAK2 polyclonal antibody were obtained from BioSource (Nivelles, Belgium). Rabbit anti-phospho-JAK2, phospho-Stat1, and Stat1 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). RNA isolation kit was obtained from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). Primer sets for iNOS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) were obtained from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). Fluorogenic probes for iNOS and G3PDH and reagents for real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), or Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Cell culture

Neonatal 6 days Sprague–Dawley rats were anaesthetized with ether and killed by decapitation. The Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine had approved the animal protocol. Primary culture of astrocytes were prepared from the cerebral cortices and maintained in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Wang et al., 1999b). After confluence, contaminated microglia and oligodendrocytes were removed by shaking at 200 r.p.m. with an orbital shaker. Thereafter, the cells were subcultured in culture dishes and the medium was changed every 2–3 days. After confluence, cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 1% FBS and all the experiments were performed under this condition.

Measurement of nitrite and iNOS in vitro enzymatic activity

Cells were incubated with 5 μg ml−1 LPS and 10 ng ml−1 IFN-γ to induce the expression of iNOS. The induction of iNOS was assessed by measuring the accumulation of nitrite in the culture medium by using Griess reagent with NaNO2 as standard. For the assay of iNOS in vitro enzymatic activity, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested in hypotonic buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, and 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin). Cellular lysates were prepared by freezing and thawing, then incubated with iNOS reaction buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 0.2 mM NADPH, 10 μM FAD, 10 μM FMN, 100 μM tetrahydrobiopterin, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM arginine containing 0.5 μCi [3H]arginine, with or without 2 mM Nω-nitro-L-arginine) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 0.8 ml Hepes buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 5.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM citrulline). [3H]Arginine and [3H]citrulline were separated over Dowex AG50W-X8 columns (sodium form). The radioactivity of citrulline was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The enzymatic activity of iNOS was presented as pmol of citrulline formed min−1 mg−1 cellular protein (Wang et al., 1999b). Falcarindiol was included in the reaction mixture to verify the direct effect of falcarindiol on the activity of iNOS.

Assay of cell viability

Primary astrocytes were treated with 0–50 μM of falcarindiol for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by the ability to reduce 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) as described previously (Wang et al., 1999b).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Treated cells were harvested in lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 2.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, and 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin). Total cellular lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-iNOS antibody. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). Immunoreactive proteins were detected by using anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and ECL detection reagents.

For detection of protein phosphorylation, cells were harvested in lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 2.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, and 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin). The immunoblotting was performed to investigate the activation of JAK1, JAK2, and Stat1 by using anti-phospho-JAK1 (Tyr1022/1023), anti-phospho-JAK2 (Tyr1007/1008), and anti-phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701) antibodies, respectively.

Estimate of the mRNA level of iNOS by quantitative real-time RT–PCR

Cells were treated with iNOS inducers or inducers plus falcarindiol for 4 h. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to real time quantitative RT–PCR by using ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system. The detailed experiments were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. The design of primer sets and probe was according to the sequence of iNOS gene (GenBank, accession from No. AJ230463 to No. AJ230487). For real-time quantitative RT–PCR, two primers (forward primer: 5′GGCAGGATTCAGTGGTCCAA3′, reverse primer: 5′TGCTGGAACATTTCTGATGCA3′) and sequence-specific probe (FAM-CAGGTCTTCGATGCCCGGAGCT-TAMRA) were used to specifically amplify the cDNA of iNOS. To amplify the cDNA of G3PDH, the forward primer (5′TGAAGGTCGGTGTCAACGGATTTGGC3′), reverse primer (5′CATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC3′), and sequence-specific probe (FAM-CGGATTTGGCCGTATCGGACGA-TAMRA) were used. The end products were analyzed on 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Fluorescent signal of each cycle is collected and plotted as amplification plot (plot of fluorescence signal versus cycle number). The parameter CT (threshold cycle) is defined as the fraction cycle number at which the fluorescence passes the fixed threshold above baseline. The log of initial target copy number for a set of standards versus CT is a straight line. Therefore, CT and a relative standard curve with known amounts of total RNA were used to determine the relative amount of iNOS or G3PDH in unknown samples.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Treated cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and harvested. The cells were used to prepare nuclear extracts. The nuclear extracts (5 μg for AP-1, 10 μg for NF-κB, or ISRE/GAS) were incubated with 1 ng of 5′-end-labeled consensus oligonucleotide for AP-1, NF-κB, or ISRE/GAS in binding solution (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2, 140 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 12% glycerol, and 1 μg poly(dI-dC)) at room temperature for 30 min. The mixtures were subjected to 5% of nondenatured PAGE by using 1 × TBE as electrophoresis buffer. The gels were dried and radioactive oligonucleotides were detected and quantified by storage phosphor autoradiography.

In vitro kinase assay of IKK-α and IKK-β

Treated cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and solubilized by kinase lysis buffer (40 mM Tris pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 1 mM benzamidine). Total cellular lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation using either anti-IKK-α or anti-IKK-β antibody. After incubation with antibodies at 4°C overnight, sepharose CL-4B beads conjugated with protein A were added into mixture and incubated for another 2 h. The beads were washed three times with kinase lysis buffer (containing 500 mM NaCl and 10 mM NaF), and twice with kinase buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM Na3VO4, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 5 μg ml−1 antipain). The in vitro kinase assay was performed by incubating beads with 20 μl of kinase buffer containing 0.5 μg of GST-IκB-α fusion protein. The reaction was started by adding radioactive ATP to a final concentration of 50 μM with 5 μCi [γ-32p]ATP and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding sample buffer, the mixture was subjected to 10% SDS–PAGE. The gel was dried and radioactive IκB-α fusion protein was detected and quantified by storage phosphor autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means±s.d., and were analyzed by ANOVA with post hoc multiple comparison using a Bonferroni test.

Results

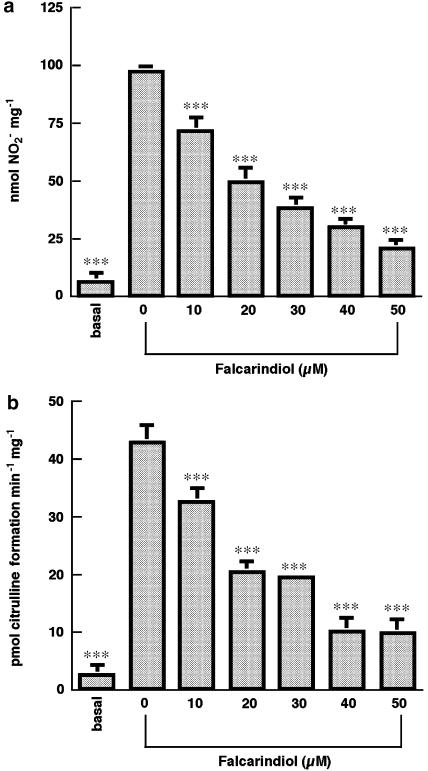

Falcarindiol inhibited the induction of iNOS

Treatment of primary culture of astrocytes with 5 μg ml−1 LPS plus 10 ng ml−1 IFN-γ for 24 h elicited a significant increase of iNOS induction as determined by nitrite accumulation in the culture medium (n=5) (Figure 2a). The accumulation of nitrite in culture medium was elevated from 5.7 to 96.4 nmol mg−1 cellular protein. Treatment with falcarindiol blocked the LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated accumulation of nitrite in a concentration-dependent manner. The LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated accumulation of nitrite was decreased to 20.7% of control by treatment with 50 μM falcarindiol.

Figure 2.

Effect of falcarindiol on the induction of iNOS. Primary astrocytes were preincubated with various concentrations of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to 5 μg ml−1 LPS plus 10 ng ml−1 IFN-γ (LPS/IFN-γ) in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 24 h. The culture media were collected for nitrite determination (a). To assay the in vitro enzymatic activity of iNOS (b), cells were treated with falcarindiol as described above. Treated cells were harvested and the activity of iNOS was determined by citrulline formation. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from five independent experiments. Significant differences between cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone and cells treated with vehicle or inducers plus falcarindiol are indicated by ***P<0.001.

The in vitro enzymatic activity of iNOS was also verified by the formation of citrulline. Treatment of astrocytes with LPS/IFN-γ increased the enzyme activity of iNOS from 2.4 to 42.6 pmol citrilline min−1 mg−1 cellular protein (n=5) (Figure 2b). Falcarindiol at 20 and 50 μM decreased the enzyme activity of iNOS by 51.9 and 77.4%, respectively. The IC50 of falcarindiol was 21.1 μM for both nitrite accumulation and enzyme activity. Neither the basal level of nitrite accumulation nor the basal level of in vitro enzymatic activity was altered by treatment with falcarindiol alone (data not shown). The result from experiment that falcarindiol was introduced in the reaction mixture showed that falcarindiol did not directly affect the activity of iNOS. Falcarindiol had no effect on the cell viability at 10–50 μM as determined by the ability of MTT reduction (100% for control cells versus 91.4% for cells treated with 50 μM falcarindiol for 24 h, n=4).

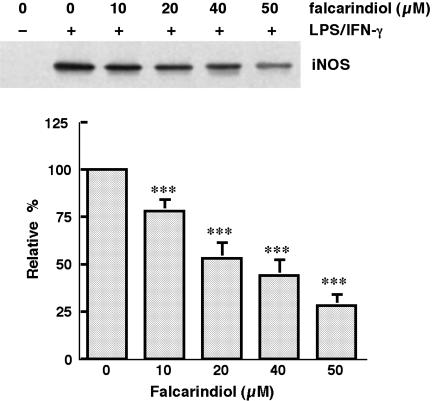

Falcarindiol reduced the protein content and mRNA level of iNOS

iNOS protein was barely detected in control cells. LPS/IFN-γ significantly increased the content of iNOS in primary astrocytes (n=4) (Figure 3). The protein content of iNOS induced by LPS/IFN-γ was abolished in a concentration-dependent manner by falcarindiol. Falcarindiol at 20 and 50 μM reduced the iNOS content by 47.2 and 71.8%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of falcarindiol on the protein content of iNOS. Primary astrocytes were preincubated with falcarindiol at the concentration indicated for 30 min. After incubation, astrocytes were challenged with LPS/IFN-γ plus or minus falcarindiol for 24 h. After incubation for 24 h, cells were harvested and iNOS was immunoprecipited and analyzed by immunoblotting. The top part is the immunoblot of iNOS. The bottom part is the relative level of iNOS in control cells and cells treated with falcarindiol. Results are means±s.d. from four independent experiments, and are expressed relative to cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone. Significant differences between control and falcarindiol-treated cells are indicated by ***P<0.001.

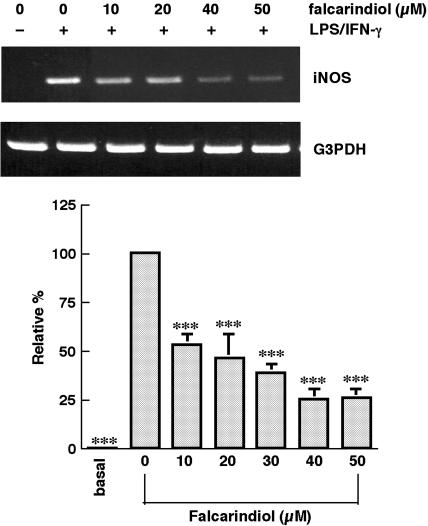

iNOS mRNA was greatly elevated by exposure to LPS/IFN-γ. Falcarindiol, 20 and 50 μM, diminished the level of iNOS mRNA by 53.2 and 73.8%, respectively (n=4) (Figure 4). Therefore, the attenuation of iNOS induction was attributable mainly to the decrease in protein content and mRNA level.

Figure 4.

Quantitative real-time RT–PCR analysis of the iNOS mRNA level in primary astrocytes. Primary astrocytes were preincubated with various concentrations of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 4 h. After incubation, total RNA was isolated and subjected to real-time RT–PCR analysis. The level of iNOS mRNA of each sample had been normalized with that of G3PDH. The top part is a photograph of agarose gel electrophoresis of iNOS and G3PDH. The bottom part is the relative level of iNOS. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from four independent experiments, and are expressed relative to cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone. Significant differences between cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone and cells treated with vehicle or falcarindiol plus inducers are indicated by ***P<0.001.

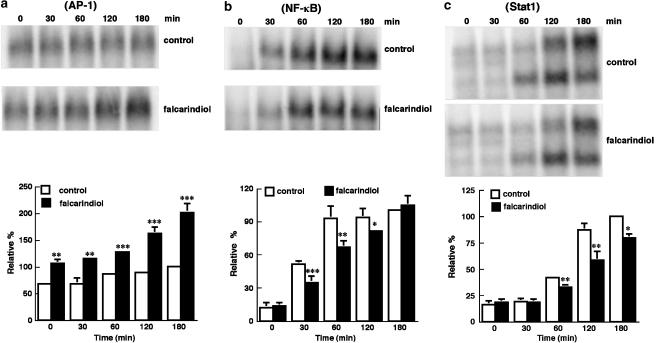

The effects of falcarindiol on the nuclear translocation of AP-1, NF-κB, and Stat1 induced by LPS/IFN-γ

LPS/IFN-γ treatment elevated the AP-1 association with consensus oligonucleotide by 1.5-fold at 3 h (n=4) (Figure 5a). Falcarindiol alone significantly increased the association of AP-1 with consensus oligonucleotide by 1.6-fold. LPS/IFN-γ significantly elevated the association of NF-κB with consensus oligonucleotide by 6.4- and 12.6-fold for 30 and 60 min, respectively (Figure 5b). Treatment with 50 μM falcarindiol attenuated the LPS/IFN-γ-induced activation of NF-κB by 32% after 30 min treatment. Falcarindiol (50 μM) also inhibited the nuclear tanslocation of Stat1 by 22.5, 33.6, and 20.7% for 1, 2, and 3 h treatment, respectively (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Time-course effect of falcarindiol on the EMSA for AP-1, NF-κB, and Stat1 binding. Primary astrocytes were preincubated without (opened column) or with (closed column) 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 0–180 min. After incubation, nuclear extracts were isolated and subjected to binding with 5′-end-labeled consensus oligonucleotides. The AP-1 (a), NF-κB (b), and Stat1(c) binding were quantified by storage phosphor autoradiography. The top part of each panel is a representative autoradiograph of AP-1, NF-κB, or Stat1 binding. The bottom part of each panel is the relative level of AP-1, NF-κB, or Stat1 binding. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from four independent experiments, and are expressed relative to the control cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ for 3 h. Significant differences between cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone and cells treated with inducers plus falcarindiol are indicated by *P<0.05; **P<0.01; and ***P<0.001.

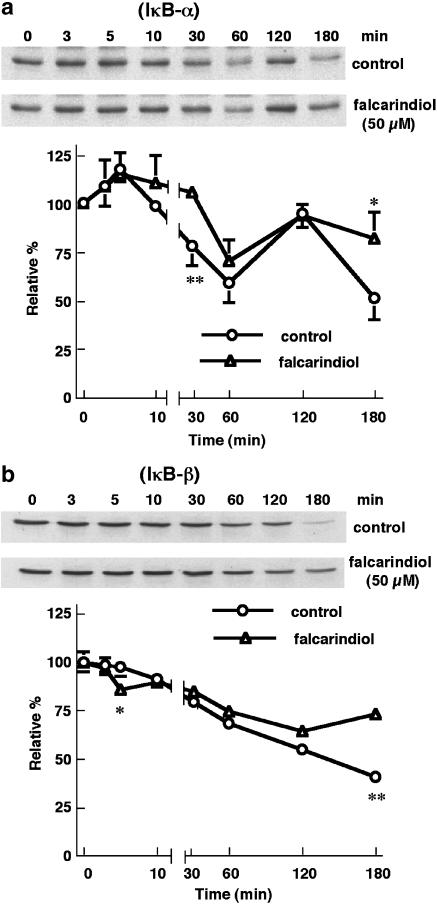

Falcarindiol modulated the degradation of IκB-α and IκB-β

LPS/IFN-γ provoked the degradation of IκB-α by 40.6% at 60 min in primary astrocytes (n=5) (Figure 6a). In all, 50 μM of falcarindiol completely abolished the degradation of IκB-α at 30 min, and attenuated the degradation from 48.3 to 18.2% at 180 min. Falcarindiol did not affect the resynthesis of IκB-α. The degradation of IκB-β induced by LPS/IFN-γ showed similar pattern to that of IκB-α except without resynthesis (Figure 6b). Falcarindiol (50 μM) eliminated the degradation of IκB-β from 59.2 to 27.0% at 180 min.

Figure 6.

Time-course effect of falcarindiol on the degradation of IκB-α and IκB-β. Primary astrocytes were preincubated without (circle) or with (triangle) 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 0–180 min. After the incubation periods, cellular lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting. The top parts of panels (a) and (b) are representative immunoblots of intracellular IκB-α and IκB-β, respectively. The bottom parts are the relative levels of intracellular IκB-α and IκB-β. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from five independent experiments, and expressed relative to the cells at zero time. Significant differences between control and falcarindiol-treated cells are indicated by *P<0.05; and **P<0.01.

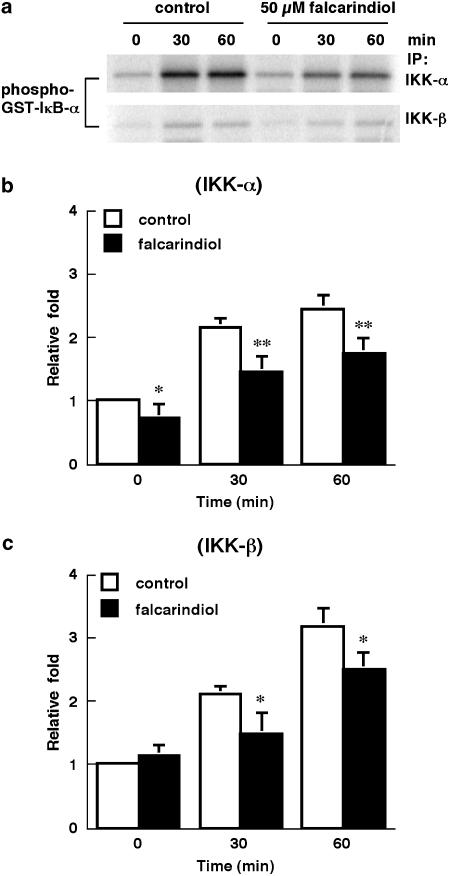

Falcarindiol abrogated the activation of IKK-α and IKK-β induced by LPS/IFN-γ

Treatment of primary astrocytes with LPS/IFN-γ for 30 and 60 min significantly increased the activity of IKK-α to 2.2- and 2.5-fold of control, respectively, by using GST-IκB-α fusion protein as substrate (n=4) (Figure 7a, b). Falcarindiol (50 μM) significantly diminished the LPS/IFN-γ-mediated activation of IKK-α by ≈30% for 0–60 min. LPS/IFN-γ elevated the activity of IKK-β to 2.1- and 3.2-fold of control for 30 and 60 min, respectively (Figure 7c). Falcarindiol attenuated the activation of IKK-β similarly to that of IKK-α. Falcarindiol (50 μM) abrogated the activation of IKK-β by 29.7 and 21.5% for 30 and 60 min, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect of falcarindiol on the activity of IKK-α and IKK-β. Primary astrocytes were preincubated without (opened column) or with (closed column) 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 30 or 60 min. After incubation, cells were collected and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-IKK-α (b) or anti-IKK-β (c) antibody. The in vitro kinase assay was performed using GST-IκB-α fusion protein as substrate. The radioactivity of GST-IκB-α fusion protein was quantified by storage phosphor autoradiography. Panel (a) is representative autoradiograph of GST-IκB-α fusion protein. Panels (b) and (c) are the relative kinase activity of IKK-α and IKK-β, respectively. Results are means±s.d. from four independent experiments, and expressed relative to the control cells at zero time. Significant differences between control and falcarindiol-treated cells are indicated by *P<0.05; and **P<0.01.

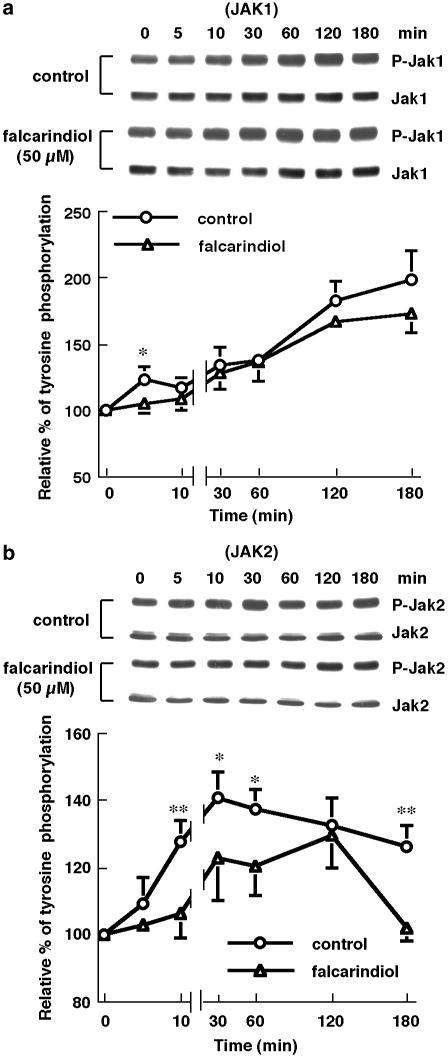

The effects of falcarindiol on tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1, JAK1, and JAK2

LPS/IFN-γ elicited significantly tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 in residue 701 as determined by using specific anti-phospho-Stat1 antibody. The tyrosine phosphorylation appeared at 5 min and reached the maximum at 30–60 min, after which the level of phosphorylation was decreased (n=5) (Figure 8). Treatment with 50 μM falcarindiol remarkably attenuated the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1. Falcarindiol decreased the tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 by 26.6% at 60 min.

Figure 8.

Effects of falcarindiol on the tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1. Primary astrocytes were preincubated without (circle) or with (triangle) 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 0–180 min. After the incubation periods, cellular lysates were prepared. The immunoblotitng was performed using anti-phsohpo-Stat1 antibodies to determine the tyrosine phosphorylation and using anti-Stat1 antibody to measure the protein content. The top part is immunoblots of tyrosine phosphorylation and protein content of Stat1. The bottom part is the relative level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1. The extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 had been normalized with the protein content of Stat1. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from five independent experiments, and are expressed relative to the control cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ for 60 min. Significant differences between cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone and cells treated with inducers plus falcarindiol are indicated by *P<0.05; and ***P<0.001.

The activation of JAK1 and JAK2 was also evaluated by immunoblotting (Figure 9). Treatment with LPS/IFN-γ for 5 and 180 min significantly increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 at residue 1022 and 1023 to 122 and 197% of control, respectively (n=4) (Figure 9a). Falcarindiol (50 μM) decreased the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 by 84.8% at 5 min, whereas it did not affect the level of JAK1 tyrosine phosphorylation after 5–180 min. LPS/IFN-γ elevated the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 at residue 1007 and 1008 by 27.7% at 10 min (Figure 9b). The level of tyrosine phosphorylation was reached maximum at 30 min and then slightly decreased. A 50 μM volume of falcarindiol inhibited the tyrosine phoshorylation of JAK2 by 82.3% at 10 min. Similar results were also observed at 30, 60, and 180 min.

Figure 9.

Effects of falcarindiol on the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 and JAK2. Primary astrocytes were preincubated without (circle) or with (triangle) 50 μM of falcarindiol for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were exposed to LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of falcarindiol for 0–180 min. After the incubation periods, cellular lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting. The immunoblotting was performed using anti-phsohpo-JAK1 (a) or anti-phospho-JAK2 (b) antibodies to determine the tyrosine phosphorylation and using anti-JAK1 or anti-JAK2 antibody to measure the protein content. The top parts of each panel are immunoblots of tyrosine phosphorylation and protein content of JAK1 or JAK2. The bottom parts are the relative level of tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 or JAK2. The level of tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 and JAK2 had been normalized with the protein amount of JAK1 or JAK2. Results are means±s.d. (where large enough to be shown) from four independent experiments, and are expressed relative to the cells at zero time. Significant differences between cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ alone and cells treated with inducers plus falcarindiol are indicated by *P<0.05; and **P<0.01.

Discussion

Falcarindiol elicited significant inhibition on the LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated accumulation of nitrite in culture medium and elevation of iNOS in vitro enzymatic activity. The inhibition was in parallel to the decrease in protein content and mRNA level of iNOS. Falcarindiol conferred its effect by impairing IKK and JAK activation consequently attenuating the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and Stat1, thereby leading to the abrogation of LPS/IFN-γ-mediated induction of iNOS.

Falcarindiol has been studied focusing on the cytotoxic activity against tumor cells (Bernart et al., 1996). In this manuscript, falcarindiol exerted inhibitory effect on the LPS/IFN-γ-mediated iNOS expression. Some studies also showed that falcarindiol reduced iNOS-mediated NO production induced by LPS in BV-2 cells, microglia, mouse peritoneal macrophags, and C6 glioma cells (Matsuda et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1999b; Min Kim et al., 2003). Our previous results suggest that the structure of polyacetylenes are involved in their inhibitory potencies on the induction of iNOS (Wang et al., 1999b). Falcarinone failed to block the expression of iNOS indicating that the hydroxyallylic moiety is essential for the inhibition.

In present study, we attempted to explore the mechanisms underlying falcarindiol that abrogated the LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated induction of iNOS. The signaling of LPS is mediated by its receptor membrane-bound CD14 and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Wright et al., 1990). TLR4 serves as a cell surface coreceptor with CD14 to mediate transmembrane signaling. The signaling of LPS is mediated by the activation of Rip/TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) → NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) → IKK-α/IKK-β pathway, leading to subsequent cellular events (Cao et al., 1996; Woronicz et al., 1997; Chow et al., 1999; Poltorak et al., 2000).

Treatment with LPS/IFN-γ elicits the serine phosphorylation of IκB-α and IκB-β by IKK-α or IKK-β, which provokes the degradation of IκB and the dissociation of NF-κB from IκB. NF-κB subsequently translocates into the nucleus and interacts with the NF-κB binding motif in the promoters of target genes (DiDonato et al., 1997; Mercurio et al., 1997; Régnier et al., 1997; Woronicz et al., 1997; Li & Stark, 2002). NF-κB activation has been shown to be important for the expression of iNOS. Our results showed that falcarindiol inhibited the activation of NF-κB during 30–120 min. Therefore, the inhibition of NF-κB activation may account partly for the suppression of iNOS expression by falcarindiol. Result of IκB-α degradation showed a resynthesis of IκB-α following the degradation. Studies on the promoter analysis of the gene encoding IκB-α have demonstrated that there are three NF-κB-binding sites located in promoter region (Ito et al., 1994). This explains that there was a resynthesis of IκB-α following the degradation.

Multiple evidences indicate that IKK-β is primarily responsible for the activation of NF-κB in response to proinflammatory stimuli, whereas IKK-α is essential for epidermal differentiation and B-cell maturation (Hu et al., 1999; Li et al., 1999; Takeda et al., 1999; DiDonato, 2001; Senftleben et al., 2001). The present study showed that falcarindiol exerted similar inhibitory extent for both IKK-α and IKK-β. The rate and extent of IκB-α degradation were more significant than that of IκB-β, indicating IκB-α is the preferable substrate for IKK comparing to IκB-β. The autophosphorylation of a serine cluster located between the LHL motif of IKK-β and its COOH terminus decreases IKK activity (Delhase et al., 1999). This feedback inhibition contributes to the transient activation of IKK by strong stimulation such as TNF. Our results showed that the activation of IKK was sustained up to 60 min in contrast to the transient activation of IKK in response to TNF-α (Mercurio et al., 1997; Zandi et al., 1997). Our results reflect that the feedback inhibition of IKK activity is much slower in response to LPS/IFN-γ than that of TNF-α. The sustained activity of IKK may also provide explanation for the degradation of IκB after 3 h treatment.

Binding of IFN-γ to its receptor, composing of two subunits IFN-γ receptor 1 (IFNGR1) and IFNGR2, induces oligomerization and activation of the receptor-associated JAK1 and JAK2 by trans-phosphorylation. JAK-mediating tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 triggers the dimerization through the interaction of phosphorylated tyrosine residue and Src-homology-2 domain. Dimerized Stat1 translocates into the nucleus and regulates gene expression by binding to ISRE or GAS (Gao et al., 1997; Kovarik et al., 1998; Ohmori & Hamilton, 2001; Ramana et al., 2002; Schroder et al., 2004). Our results showed falcarindiol significantly attenuated the activation of JAK and Stat1. These results indicate that JAK/Stat1 pathway played a pivotal role for falarindiol to confer its inhibitory effect on iNOS expression. The 5′-flanking region of the murine iNOS gene contains at least 10 copies of IRE, three copies of the GAS and two copies of the ISRE (Xie et al., 1993). Piles of evidences have demonstrated that Stat1 functions as the crucial regulator for iNOS expression. Stat1 knockout mice are defective for induction of NO production by LPS or LPS/IFN-γ (Meraz et al., 1996; Ohmori & Hamilton, 2001). JAK/Stat1 pathway is essential for the cytokine-mediated iNOS expression in either human or murine cell cultures (Dell'Albani et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Tedeschi et al., 2003; 2004; Yao et al., 2003).

In the present study, we showed falcarindiol blocked the activation of JAK1 and JAK2. Falcarindiol elicited inhibitory effect on JAK1 only at 5 min time point. The appearance of tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 occurred early at 5 min. Therefore, the inhibition at 5 min is not only statistically significant but may also be biologically relevant. The high level of basal tyrosine phosporylation of JAK1 and JAK2 were observed in the present study. The confluent cells we used in this study may explain the high level activity of JAK. Nevertheless, the question emerged that why high level activity of JAK did not coincide with the appearance of phosphorylated Stat1. The formation of docking sites for Stat1 is requisite for the generation of phosphorylated Stat1 by the kinase activity of JAK. This event is a paired ligand-induced process. Functionally active IFN-γ is a homodimer that binds to two IFNGR1 subunits, thereby generating binding site for two IFNGR1 subunits (Stark et al., 1998; Levy & Darnell, 2002; Shuai & Liu, 2003). The assembly of receptor complex leads to the activation of JAK and the formation of Stat1 docking site. Therefore, this explains the event that in spite of the high basal activity of JAK kinase there was no phosphorylated Stat1 formation in the absence of IFN-γ.

The main AP-1 proteins in mammalian cell are c-fos and c-jun. AP-1 activity has been described being implicated in the expression of iNOS (Marks-Konczalik et al., 1998; Pahan et al., 2002). The activity AP-1 is regulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Cytokines stress activates various transcription factors (ternary-complex factors (TCFs), myocyte-enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C), activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), and jun) that induce the expression of fos and jun. Post-translational phosphorylation of jun by JNK also activates the AP-1 activity (Eferl & Wagner, 2003). In the present study, results showed that falcarindiol itself promoted the binding of AP-1 with the consensus oligonucleotide. The stimulation of falcarindiol on AP-1 activity may mediate by elevating the expression of fos/jun or the phosphorylation of jun. It is worthwhile to note that several reports have shown that AP-1 may also function as a negative regulator of iNOS expression (Kleinert et al., 1998; Pance et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2004). Therefore, we speculate that whether there was possibility that the overstimulation of AP-1 activity induced by falcarindiol might relate to its inhibition of iNOS expression.

Besides transcriptional activation, mRNA stability also controls the mRNA level of iNOS. The AU-rich element (ARE) containing one or more AUUUA sequences confers instability on the mRNA (Chen & Shyu, 1995). AUUUA motifs have been found in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of iNOS mRNA from rat astrocytes and mouse macrophages (Galea et al., 1994). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that falcarindiol disturbed the stability of iNOS mRNA by modulating the interaction of AU-binding factors with ARE, thereby leading to the decrease in the level of mRNA.

The present study provided novel mechanisms for falcarindiol to block the expression of iNOS. Falcarindiol attenuated the activation of IKK and JAK leading to the blockade of nuclear translocation of NF-κB and Stat1, consequently eliminating the induction of iNOS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Science Council Grant NSC89-2320-B-077-012, NSC90-2320-B077-015, and National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine Grant NRICM93-DBCMR-03. Taiwan, R.O.C.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- ARE

AU-rich element

- GAS

IFN-γ-activated site

- G3PDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IκB

inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IL

interleukin

- IRE

IFN-γ response element

- ISRE

IFN-stimulated response element

- JAK

janus kinase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NIK

NF-κB-inducing kinase

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PKC

protein kinase C

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- Stat1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRAF

TNF receptor-associated factor

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- BAEUERLE P.A., HENKEL T. Function and activation of NF-κB in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNART M.W., CARDELLINA J.H., BALASCHAK M.S., ALEXANDER M.R., SHOEMAKER R.H., BOYD M.R. Cytotoxic falcarinol oxylipins from Dendropanax arboreus. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:748–753. doi: 10.1021/np960224o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHAT N.R., ZHANG P., LEE J.C., HOGAN E.L. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 subgroups of mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression in endotoxin-stimulated primary glial cultures. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1633–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAO Z., XIONG J., TAKEUCHI M., KURAMA T., GOEDDEL D.V. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARPENTER L., CORDERY D., BIDEN T.J. Protein kinase Cdelta activation by interleukin-1beta stabilizes inducible nitric-oxide synthase mRNA in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5368–5374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.C., WANG J.K., CHEN W.C., LIN S.B. Protein kinase Cη mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric-oxide synthase expression in primary astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19424–19430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.-W., CHAO Y., CHANG Y.-H., HSU M.-J., LIN W.W. Inhibition of cytokine-induced JAK-STAT signalling pathways by an endonuclease inhibitor aurintricarboxylic acid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:1011–1020. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.Y.A., SHYU A.B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOW J.C., YOUNG D.W., GOLENBOCK D.T., CHRIST W.J., GUSOVSKY F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M. Nitric oxide in neuronal degeneration. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1996;221:33–40. doi: 10.3181/00379727-211-43950e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELHASE M., HAYAKAWA M., CHEN Y., KARIN M. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELL'ALBANI P., SANTANGELO R., TORRISI L., NICOLETTI V.G., DE VELLIS J., GIUFFRIDA STELLA A.M. JAK/STAT signaling pathway mediates cytokine-induced iNOS expression in primary astroglial cell cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;65:417–424. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DÍAZ-GUERRA M.J.M., BODELÓN O.G., VELASCO M., WHELAN R., PARKER P.J., BOSCÁ L. Up-regulation of protein kinase C-ɛ promotes the expression of cytokine-inducible nitric oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32028–32033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIDONATO J.A.IKK on center stage Sci. STKE 20012001, pe1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- DIDONATO J.A., HAYAKAWA M., ROTHWARF D.M., ZANDI E., KARIN M. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFERL R., WAGNER E.F. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALEA E., REIS D.J., FEINSTEIN D.L. Cloning and expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase from rat astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 1994;266:3172–3177. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO J., MORRISON D.C., PARMELY T.J., RUSSELL S.W., MURPHY W.J. An interferon-γ-activated site (GAS) is necessary for full expression of the mouse iNOS gene in response to interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:1226–1230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOBBS A.J., HIGGS A., MONCADA S. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase as a potential therapeutic target. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999;39:191–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU Y., BAUD V., DELHASE M., ZHANG P., DEERINCK T., ELLISMAN M., JOHNSON R., KARIN M. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKalpha subunit of IkappaB kinase. Science. 1999;284:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISRAEL A. The IKK complex: an integrator of all signals that activate NF-kappaB. Trends Cell. Biol. 2000;10:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO C.Y., KAZANTSEV A.G., BALDWIN A.S., JR Three NF-κB sites in the IκB-α promoter are required for induction of gene expression by TNFα. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3787–3792. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M., DELHASE M. The IkappaB kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin. Immunol. 2000;12:85–98. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINERT H., WALLERATH T., FRITZ G., IHRIG-BIEDERT I., RODRIGUEZ-PASCUAL F., GELLER D.A., FÖRSTERMANN U. Cytokine induction of NO synthase II in human DLD-1 cells: roles of the JAK-STAT, AP-1 and NF-κB-signaling pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:193–201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOVARIK P., STOIBER D., NOVY M., DECKER T. Stat1 combines signals derived from IFNγ and LPS receptors during macrophage activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:3660–3668. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVY D.E., DARNELL J.E., JR Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI Q., VAN ANTWERP D., MERCURIO F., LEE K.F., VERMA I.M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI X., STARK G.R. NFκB-dependent signaling pathways. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIPTON S.A., CHOI Y.B., PAN Z.H., LEI S.Z., CHEN H.S., SUCHER N.J., LOSCALZO J., SINGEL D.J., STAMLER J.S. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compound. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKS-KONCZALIK J., CHU S.C., MOSS J. Cytokine-mediated transcriptional induction of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene requires both activator protein 1 and nuclear factor κB-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22201–22208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA H., MURAKAMI T., KAGEURA T., NINOMIYA K., TOGUCHIDA I., NISHIDA N., YOSHIKAWA M. Hepatoprotective and nitric oxide production inhibitory activities of coumarin and polyacetylene constituents from the roots of Angelica furcijuga. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:2191–2196. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERAZ M.A., WHITE J.M., SHEEHAN K.C., BACH E.A., RODIG S.J., DIGHE A.S., KAPLAN D.H., RILEY J.K., GREENLUND A.C., CAMPBELL D., CARVER-MOORE K., DUBOIS R.N., CLARK R., AGUET M., SCHREIBER R.D. Targeted disruption of the Stat 1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the Jak-Stat signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84:431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERCURIO F., ZHU H., MURRAY B.W., SHEVCHENKO A., BENNETT B.L., LI J.W., YOUNG D.B., BARBOSA M., MANN M. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERRILL J.E., IGNARRO L.J., SHERMAN M.P., MELINEK J., LANE T.E. Microglial cell cytotoxicity of oligodendrocytes is mediated through nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 1993;151:2132–2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIN KIM J., LEE P., SON D., KIM H., YEOU KIM S. Falcarindiol inhibits nitric oxide-mediated neuronal death in lipopolysaccharide-treated organotypic hippocampal cultures. NeuroReport. 2003;14:1941–1944. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200310270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITROVIC B., IGNARRO L.J., MONTESTRUQUE S., SMOLL A., MERRILL J.E. Nitric oxide as a potential pathological mechanism in demyelination: its differential effects on primary glial cells in vitro. Neuroscience. 1994;61:575–585. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHMORI Y., HAMILTON T.A. Requirement for Stat1 in LPS-induced gene expression in macrophage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHAN K., JANA M., LIU X., TAYLOR B.S., WOOD C., FISCHER S.M. Gemfibrozil, a lipid-lowering drug, inhibits the induction of nitric-oxide synthase in human astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45984–45991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200250200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANCE A., CHANTOME A., REVENEAU S., BENTRARI F., JEANNIN J.-F. A repressor in the proximal human inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter modulates transcriptional activation. FASEB J. 2002;16:131–133. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0450fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLTORAK A., RICCIARDI-CASTAGNOLI P., CITTERIO S., BEUTLER B. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and Toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:2163–2167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040565397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMANA C.V., GIL M.P., SCHREIBER R.D., STARK G.R. Stat1-dependent and -independent pathways in IFN-γ-dependent signaling. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RÉGNIER C.H., SONG H.Y., GAO X., GOEDDEL D.V., CAO Z., ROTHE M. Identification and characterization of an IκB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRODER K., HERTZOG P.J., RAVASI T., HUME D.A. Interferon-γ: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;75:163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENFTLEBEN U., CAO Y., XIAO G., GRETEN F.R., KRAHN G., BONIZZI G., CHEN Y., HU Y., FONG A., SUN S.C., KARIN M. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUAI K., LIU B. Regulation of JAK-Stat signaling in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:900–911. doi: 10.1038/nri1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STARK G.R., KERR I.M., WILLIAMS B.R.G., SILVERMAN R.H., SCHREIBER R.D. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEDA K., TAKEUCHI O., TSUJIMURA T., ITAMI S., ADACHI O., KAWAI T., SANJO H., YOSHIKAWA K., TERADA N., AKIRA S. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKalpha. Science. 1999;284:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEDESCHI E., MENEGAZZI M., MARGOTTO D., SUZUKI H., FÖRSTERMANN U., KLEINERT H. Anti-inflammatory actions of St. John's Wort: inhibition of human inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by down-regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription-1α (STAT-1α) activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;307:254–261. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEDESCHI E., MENEGAZZI M., YAO Y., SUZUKI H., FÖRSTERMANN U., KLEINERT H. Green tea inhibits human inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by down-regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription-1α activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:111–120. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THANOS D., MANIATIS T. NF-κB: a lesson in family values. Cell. 1995;80:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG C.C., CHEN L.G., YANG L.L. Inducible nitric oxide inhibitor of Chinese herb I. Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. Cancer Lett. 1999a;145:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG C.N., SHIAO Y.J., KUO Y.H., CHEN C.C., LIN Y.L. Inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitors from Saposhnikovia divaricata and Panax quinquefolium. Planta Med. 2000;66:644–647. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG C.N., SHIAO Y.J., LIN Y.L., CHEN C.F. Nepalolide A inhibits the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by modulating the degradation of IκB-α and IκB-β in C6 glioma cells and rat primary astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999b;128:345–356. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORONICZ J.D., GAO X., CAO Z., ROTHE M., GOEDDEL D.V. IκB kinase-β: NF-κB activation and complex formation with IκB kinase-α and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT S.D., RAMOS R.A., TOBIAS P.S., ULEVITCH R.J., MATHISON J.C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE Q.-W., WHISNANT R., NATHAN C. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-ndependent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1779–1784. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO Y., HAUSDING M., ERKEL G., ANKE T., FÖRSTERMANN U., KLEINERT H. Sporogen, S14-95, and S-curvularin, three inhibitors of human inducible nitric oxide synthase expression isolated from fungi. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:383–391. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZANDI E., ROTHWARF D.M., DELHASE M., HAYAKAWA M., KARIN M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG B., PERPETUA M., FULMER M., HARBRECHT B.G. JNK signaling involved in the effects of cyclic AMP on IL-1β plus IFN-γ-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in hepatocytes. Cell Signal. 2004;16:837–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]