Abstract

Our aim was to synthesise an 18F analogue of endothelin-1 (ET-1), to dynamically image ET receptors in vivo by positron emission tomography (PET) and to elucidate the function of the ETB subtype as a clearing receptor in organs expressing high densities including kidney and lung.

[18F]-ET-1 was characterised in vitro and bound with a single subnanomolar affinity (KD=0.43±0.05 nM, Bmax=27.8±2.1 fmol mg−1 protein) to human left ventricle (n=4).

The in vivo distribution of [18F]-ET-1 in anaesthetised rats was measured using a dedicated small animal PET scanner (microPET) and ex vivo analysis.

Dynamic PET data demonstrated that high levels of radioligand accumulated rapidly in the lung, kidney and liver, consistent with receptor binding. The in vivo distribution correlated with the anatomical localisation of receptors detected in vitro using [125I]-ET-1. However, the receptor density visualised in the heart was unexpectedly low compared with that predicted from the in vitro measurements.

[18F]-ET-1 binding in lungs could not be displaced by the ETB selective antagonist BQ788, in agreement with the proposed internalisation of ET-1 by ETB receptors. In contrast, infusion of BQ788 prior to injecting [18F]-ET-1 significantly reduce the amount of radioligand visualised in the ETB rich lung and kidney by 85% (P<0.05, n=3) and 55% (P<0.05, n=3), respectively.

Under conditions of ETB receptor blockade, the heart could be visualised by microPET imaging.

These results suggest that clearance by ETB receptors in the lung and kidney prevents binding of ET-1 to receptors in the heart.

Keywords: Endothelin, ET-1, positron emission tomography, PET, microPET, 18F, in vivo imaging

Introduction

The potent, vasoactive peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) has been suggested to play a role in cardiovascular diseases including chronic heart failure, hypertension, atherosclerosis, cerebral vasospasm and pulmonary hypertension (Schiffrin et al., 1997; Miyauchi & Masaki, 1999; Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001). The action of ET-1 is mediated by two receptor subtypes, ETA and ETB, that are widely expressed in human tissue (Davenport & Russell, 2001). In humans, ET-1 is thought to be continuously released from the endothelium, causing long-lasting vasoconstriction by stimulation of ETA receptors present on the underlying smooth muscle and so contributing to the maintenance of normal vascular tone (Russell & Davenport, 1999). In contrast, ET-1 acting on ETB receptors expressed by the endothelium causes vasodilatation through release of nitric oxide and prostacyclin (de Nucci et al., 1988) counterbalancing the vasoconstriction (Haynes & Webb, 1998). Furthermore, the ET receptor system is involved in the modulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis (Wu-Wong & Opgenorth, 2001). In chronically instrumented rats it has been demonstrated that exogenous administered ET-1 interacts with vascular ET receptors (Gardiner et al., 1993; 1994a, 1994b).

Positron emission tomography (PET) is widely used to study transmitter systems in vivo. Recent developments in dedicated tomographs for laboratory animals have resulted in an improved spatial resolution of 1–2 mm (Chatziioannou, 2002; Lewis et al., 2002). These tomographs can delineate discrete organs and their larger substructures and consequently provide the means to study normal controls and rodent models of disease.

Two drug strategies are currently being pursued to prevent the unwanted actions of ET-1: ETA selective or mixed ETA/ETB antagonists (Lüscher & Barton, 2000). However, the optimum pharmacological profile for the ET antagonists has not yet been fully clarified (Dupuis, 2000; Kalra et al., 2002; Ertl & Bauersachs, 2004). Reports in the literature have suggested that ETB receptors in the lung and kidney might have an additional beneficial function clearing ET-1 from the circulation (Fukuroda et al., 1994). In vitro studies have shown that the ET-1/ETB receptor complex is rapidly internalised following agonist stimulation and transported to the lysosomes for degradation, suggesting a mechanism for the clearance of ET-1 via this subtype (Bremnes et al., 2000; Oksche et al., 2000).

To test the hypothesis of tissue-specific removal of circulating peptide and further clarify the function of the ETB subtype as a clearing receptor in vivo, our aim was to synthesise an 18F analogue of ET-1 that retained high-affinity binding and use this ligand to dynamically image ET receptors in the presence and absence of the ETB selective antagonist BQ788. Here we report for the first time the imaging of a vascular peptide receptor system using 18F and microPET.

Methods

Animals

PET experiments were performed in male Sprague–Dawley rats (328±14 g). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom Animal Scientific Procedures Act, 1986 and complied with guidelines of the local animal ethics committee. Rats were housed with free access to standard rat food and water prior to the experimental procedure.

In vitro experiments

Tissue preparation

Human tissue was obtained with local ethical approval at the time of operation, snap frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until use. Cryostat sections (30 μm) were cut from the left ventricular wall from explanted hearts of recipient patients undergoing cardiac transplantation for dilated cardiomyopathy and normal renal tissue (containing cortex and medulla) obtained from the opposite pole to non-obstructing tumours following nephrectomy.

In vitro binding characterisation of [18F]-ET-1

[18F]-ET-1 was characterised using ligand-binding assays as previously described (Davenport & Kuc, 2002). For association experiments, sections of human left ventricle were incubated with [18F]-ET-1 (1 nM) for increasing time periods (0–120 min) and in saturation assays with increasing concentrations of [18F]-ET-1 (5 pM–2.5 nM) for 90 min. For competition experiments, sections of kidney were incubated with a fixed concentration of [18F]-ET-1. Inhibition of binding to ETA or ETB receptors was obtained by co-incubation with 1 μM FR139317 (ETA selective antagonist) and 1 μM BQ3020 (ETB selective agonist), respectively. Nonspecific binding in all assays was defined by co-incubating adjacent sections with unlabelled ET-1 (1 μM). Specifically bound ligand was measured by gamma counting (Cobra II, PerkinElmer Life Sciences Ltd, Cambridge, U.K.) or by apposing the tissue to a storage phosphor imaging screen before analysis (Cyclone, PerkinElmer Life Sciences Ltd, Cambridge, U.K.). Binding was quantified using 18F standard curves for gamma counting or co-exposing the standards with the tissue sections.

Animal preparation

Rats were anaesthetised with 3% isofluorane (Baker Norton, Bristol, U.K.) vaporised in N2O/O2 (0.8/0.4 l min−1) and maintained with 2% isofluorane. Body temperature was monitored and maintained in the normal range. A femoral vein was cannulated for administration of [18F]-ET-1 and BQ788, and an artery cannulated for blood pressure monitoring. During PET scanning, anaesthesia was reduced to 1.5–2% isofluorane in N2O/O2 (0.8/0.4 l min−1).

MicroPET imaging

Study design

Dynamic in vivo imaging of [18F]-ET-1 binding to ET receptors in rat was studied using microPET. For control experiments using [18F]-ET-1 alone, dynamic scans were performed for up to 2 h. To test the effect of ETB receptor blockade, rats were pretreated with the ETB antagonist BQ788 (1 mg kg−1) immediately prior to injection of [18F]-ET-1 and imaged for 2 h. In one experiment, to test whether [18F]-ET-1 binding could be displaced, BQ788 (10 mg kg−1) was infused 30 min after the administration of radioligand and the animal scanned for an additional 75 min. In one study, to obtain a whole-body distribution of ET-1, data were acquired in four separate bed positions, using 6 × 5 min time frames for each position, starting 20 min postinjection of [18F]-ET-1.

MicroPET system

Animals were imaged using a microPET P4 scanner (Tai et al., 2001) (Concorde Microsystems, Knoxville, U.S.A.). Rats were placed prone on the scanning bed and located in a purpose-built plastic stereotaxic frame. The computer controlled scanning bed was positioned so that the axial field of view (7.8 cm) encompassed the organs of interest.

Acquisition protocol

[18F]-ET-1 (7.8±1.4 MBq) was administered to the rats as a bolus intravenous injection. A timing window of 10 ns was used in conjunction with an energy window of 250–750 keV to increase sensitivity. The data (except the whole-body scan) were initially acquired into the following time frames starting at the time of tracer administration: 10 × 0.5, 5 × 1, 15 × 2 and then in 5 min frames to the end of the experiment. Subsequently, the list-mode data in the first frame were binned into 6 × 2 s frames to provide sufficient sampling of the vena cava activity to permit normalisation of the scans for injected activity.

Image reconstruction

All images were reconstructed using the 3D filtered backprojection algorithm (Kinahan & Rogers, 1989), adapted in-house to work with data from the microPET P4 scanner. Corrections for randoms, dead time and normalisation were applied to the data during reconstruction. Images were reconstructed into 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm3 voxels in an array of 200 × 200 × 151 and a Hanning window cutoff at 0.8 × Nyquist frequency was incorporated into the reconstruction filters.

Quantitative analysis of microPET data

Regions-of-interest (ROI) were delineated for the organs of interest using Analyze (Robb et al., 1989) (AnalyzeDirect Inc., Lenexa, U.S.A.) to construct time–activity curves. Consistently sized regions were used for all studies and were of sufficient size (⩾1.3 ml) that quantification error due to the partial volume effect should not be significant for the resolution of the microPET. Data were corrected for decay and normalised for injected dose by the integral under the time–activity curve (up to the peak) for a ROI over the vena cava.

Ex vivo tissue analysis

At the end of scanning, animals were killed by intravenous injection of pentobarbitone and organs dissected, weighed and analysed for the amount of radioactivity. Cryostat cut sections were apposed to a storage phosphor imaging screen (Cyclone, PerkinElmer Life Sciences Ltd, Cambridge, U.K.). To compare the distribution of receptors detected by [18F]-ET-1 with that obtained with the well-characterised in vitro ligand [125I]-ET-1 tissue sections were stored at −70°C for a week (90 half-lives) to allow for the decay of 18F. Sections were then re-incubated with a fixed concentration of [125I]-ET-1 (0.1 nM) using the same conditions as for the saturation experiment above. Nonspecific binding was defined by co-incubating adjacent sections with unlabelled ET-1 (1 μM). Quantitative data in each experiment were obtained by co-exposing tissue with 18F and 125I standards respectively. To compare levels of 18F and 125I binding to tissue sections, quantitative data were normalised to values for the lung in each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. The results from the association and saturation experiments were analysed using the KELL nonlinear iterative curve fitting suite of programmes (Biosoft, Cambridge, U.K.). The saturation data were fitted to a one- or two-site model using a nonlinear function. A two-site model was accepted only if it resulted in a significantly better fit as judged by an F-test (P<0.05). Mean values were compared using Student's t-test and differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Peptides and radiolabelled compounds

ET-1 and BQ3020 were obtained from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan) and Neosystem (Strasbourg, France), respectively. BQ788 and FR 139317 were synthesised by Dr A.M. Doherty (Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals Research Division, Ann Arbor, U.S.A.). [125I]-ET-1 (2000 Ci mmol−1) was obtained from Amersham Biosciences U.K. Ltd (Chalfont St Giles, U.K.). BQ788 for injection was dissolved in a small volume of DMSO before formulation in saline (2 mg ml−1, 2% DMSO).

ET-1 was labelled with 18F in the ɛ-amino group of Lys9 by conjugation with the Bolton–Hunter type reagent N-succinimidyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate (Johnström et al., 2002). Mean specific activity at injection was 182±43 GBq μmol−1 and the radiochemical purity was >95%.

Results

[18F]-ET-1 in vitro binding characteristics

Binding of [18F]-ET-1 to human left ventricle (n=4) was concentration-dependent and saturable (Table 1). A one-site model was preferred to a two-site model and the Hill slope (nH) was close to unity. The binding was time-dependent with a half-time for association of 17 min and an association rate constant (kobs) of 0.045±0.004 min−1.

Table 1.

Dissociation constant (KD), maximal density of receptors (Bmax) and Hill coefficient (nH) for [18F]-ET-1 in human left ventricle

| KD (nM) | Bmax (fmol g−1 protein) | nH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [18F]-ET-1 | 0.43±0.05 | 27.8±2.1 | 0.95±0.04 |

| [125I]-ET-1 | 0.354±0.074 | 64.3±9.8 | 0.97±0.03 |

For comparison, data obtained by Molenaar et al. (1993) for [125I]-ET-1 in human left ventricle is included.

Binding of [18F]-ET-1 to human kidney (n=4) was partially inhibited by FR139317 (1 μM) and BQ3020 (1 μM), with a significant reduction in specific binding of 33.7±13.3% (P<0.05) and 73.3±2.5% (P<0.05) respectively.

MicroPET imaging

[18F]-ET-1 in vivo distribution and binding kinetics

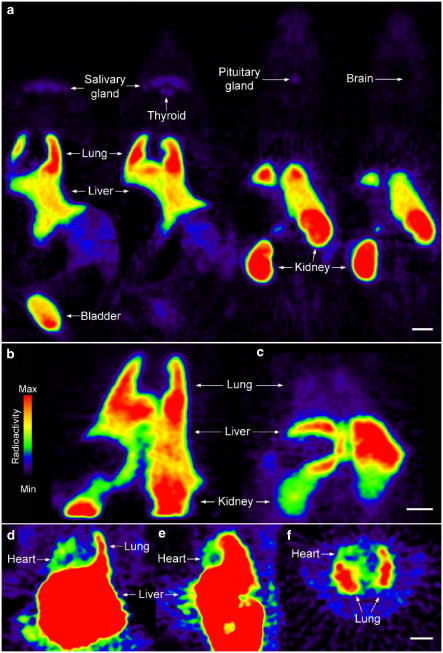

In control rats, high uptake of radioactivity was found in the lung, liver, kidney and bladder. Low levels of uptake could be visualised in the thyroid, pituitary and salivary glands, whereas brain and bone showed no uptake (Figure 1a). Delineation of the heart was difficult in control rats (Figure 1a) whereas substructures in the kidney such as the glomeruli, cortex and inner medulla/papilla could be resolved in the reconstructed images from the microPET (Figure 4a).

Figure 1.

[18F]-ET-1 microPET images: (a) whole-body distribution in four coronal planes; (b) distribution after injection of BQ788 revealing the lack of tracer displacement in the lung; (c) blockade of binding in the lung and kidney and increased uptake in the liver after preinjection of BQ788; visualisation of ET receptors in the heart after preinjection of BQ788 in coronal (d), sagittal (e) and transverse planes (f). Scale bars=10 mm.

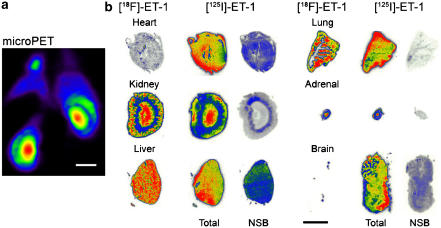

Figure 4.

(a) [18F]-ET-1 microPET image showing delineation of substructures in rat kidney. (b) Distribution within ex vivo tissue sections visualised using phosphor imaging after in vivo administration of [18F]-ET-1 and in vitro incubation of the same tissue section with [125I]-ET-1. Nonspecific binding (NSB) was determined using an adjacent section. The kidney distribution in the microPET image is similar to that seen in the ex vivo section but at a lower resolution. Scale bars=10 mm.

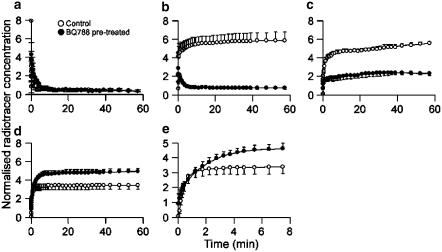

The dynamic data showed a fast clearance of [18F]-ET-1 from the circulation (t1/2=0.43 min) with a concurrent accumulation of radioactivity in the lung and liver, which rapidly reached equilibrium (Figure 2). No reduction in the level of radioactivity was observed in the lung and liver during scanning up to 2 h (dynamic data shown for up to 1 h). In the kidney an initial equilibrium was reached with a later, slow increase in uptake of radioactivity after 20 min (Figure 2). Injection of [18F]-ET-1 did not significantly alter blood pressure compared to baseline (n=4 animals).

Figure 2.

Time–activity curves for [18F]-ET-1 in control (n=3) and BQ788 pretreated rats (n=3): (a) blood pool, (b) lung, (c) kidney, (d) liver and (e) liver (expanded time scale).

Effect of ETB receptor blockade

Injection of the ETB selective antagonist BQ788 (10 mg kg−1) 30 min after radioligand administration could not displace binding in the lung (Figure 1b, dynamic data not shown). However, when BQ788 (1 mg kg−1) was injected before administration of [18F]-ET-1 a change in the distribution kinetics could be observed (Figures 1c and 2). Significant reductions in uptake were observed in the lung and kidney, which at steady state were approximately 85% (P<0.05) and 55% (P<0.05), respectively (Figure 2). In contrast, liver showed a 40% increase in uptake, reaching significance after 1 h (P<0.05). A closer inspection of the initial uptake phase for the liver revealed a difference in the shape of the curve. In control rats equilibrium was reached within 2–3 min, whereas in the preblocked experiment a slower association was observed reaching steady state after 6–8 min (Figure 2e). When the animal was pretreated with BQ788, uptake in the heart wall could be visualised indicating binding to ETA receptors (Figure 1d–f). As expected, preinjection of BQ788 caused a significant rise in blood pressure of 45% (P=0.01, n=3 animals) after infusion of the radioligand (Ishikawa et al., 1994). Vehicle for BQ788 (2% DMSO in saline) had no effect on [18F]-ET-1 kinetics when infused alone.

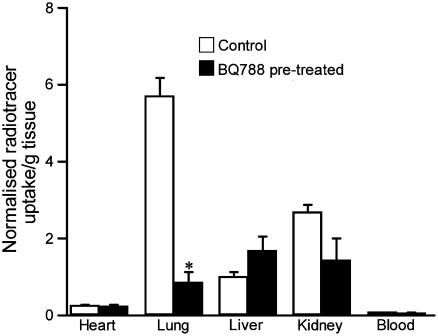

[18F]-ET-1 ex vivo distribution

Ex vivo analysis of the tissue corroborates the results obtained in the microPET, with lung the major uptake organ (Figure 3). After pretreatment with BQ788 the ex vivo data also showed a significant reduction in [18F]-ET-1 uptake in the lung (85%, P<0.05). In the kidney and liver, the data followed the same trend as in the microPET studies, with a reduction in uptake for kidney (47%) and an increase in uptake in liver (67%), although these were not significant. No significant difference was observed in the heart between control and preblocked animals.

Figure 3.

Ex vivo distribution of [18F]-ET-1 in tissue for control (n=3) and BQ788 pretreated rats (n=3). Data were normalised for injected dose by the integral under the time–activity curve (up to the peak) using the dynamic PET data for a ROI over the vena cava. *P<0.05.

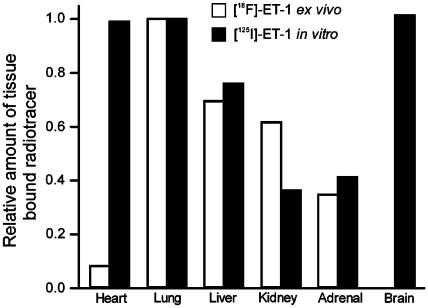

In vitro, the anatomical distribution of [125I]-ET-1 matched the ex vivo distribution of [18F]-ET-1 for all tissues except the brain and heart (Figure 4b). In the brain, the expected high density of ET receptors was visualised in vitro using [125I]-ET-1, with complete absence of binding in the ex vivo study confirming the microPET observation that [18F]-ET-1 does not cross the blood–brain barrier (Figures 4b and 5). Of more interest was our observation that the level of binding of [18F]-ET-1 in the heart was much lower than would be predicted by the in vitro binding using [125I]-ET-1 (Figures 4b and 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the level of radioactivity bound to tissue sections from the ex vivo ([18F]-ET-1) and the in vitro ([125I]-ET-1) experiment. Quantitative data were normalised to values for the lung in each experiment.

Distribution of [18F]-ET-1 in lung sections revealed a more localised uptake in the BQ788 preblocked rats compared to the control experiments (Figure 6). The corresponding microPET images of the lung also suggest a more heterogeneous distribution of radioactivity.

Figure 6.

Distribution of [18F]-ET-1 in the lung. Ex vivo tissue sections for (a) control and (b) BQ788 pretreated rat confirming blockade of nonvascular ETB receptors. Scale bar=5 mm. Transverse microPET images of the lungs revealing a more localised distribution in the BQ788 pretreated rat (d) compared to control (c). Scale bar=10 mm.

Discussion

We have shown that [18F]-ET-1 retains high-affinity binding with the expected single subnanomolar affinity comparable to values observed in vitro for [125I]-ET-1 (Table 1) (Molenaar et al., 1993) and that binding was inhibited by ETA or ETB selective ligands to levels comparable to the ratio of ETA/ETB receptors densities previously reported for human kidney (ETA: 35% and ETB: 65%) (Karet et al., 1993). Furthermore, [18F]-ET-1 can be used to visualise ET receptors with high resolution in vivo for at least 2 h using the new generation of small animal PET scanners. Although this study focused on larger organs, much smaller structures such as the thyroid and pituitary gland were easily delineated within the PET images, demonstrating that localised uptake in small structures below the notional resolution of the microPET can be resolved and imaged in vivo.

The distribution of receptors within organs visualised by [18F]-ET-1 in vivo using microPET and ex vivo using autoradiography was directly comparable to the pattern revealed by in vitro labelling with [125I]-ET-1, with two exceptions. As expected, [18F]-ET-1 did not cross the blood–brain barrier and no binding was therefore detectable in brain following in vivo administration. Importantly, [18F]-ET-1 unexpectedly labelled lower levels of receptors in the heart in vivo than predicted by the in vitro binding. Consequently, binding of [18F]-ET-1 to heart could not be visualised by microPET imaging at any time during the time course of experiments (up to 2 h) in control animals. However, following pretreatment of the animals with the ETB antagonist BQ788, the heart could be delineated in the images. No significant difference in heart uptake between control and pretreated rats was observed ex vivo, in accordance with [18F]-ET-1 binding to ETA receptors, the predominant subtype in the heart (Peter & Davenport, 1996). In addition, the large decrease in lung uptake in the pretreated rats resulted in a reduction in intensity spillover from the lungs in the images, thus allowing delineation of the heart. In support of this hypothesis, we have previously synthesised an ETA selective PET ligand [11C]-PD156707 (Johnström et al., 2000) and successfully imaged the rat heart (unpublished results) and Aleksic et al. (2001), imaged receptors in the dog heart using [11C]L-753,037, a mixed ETA/ETB receptor antagonist. Our results suggest that binding of circulating endogenous ligand to ET receptors in the heart might be prevented by the fast removal of ET-1 from the circulation by organs such as the lung and kidney.

Previous studies have suggested that the lung is an important site for the clearance of ET-1 from the circulation, mainly via the ETB receptor (Fukuroda et al., 1994; Dupuis et al., 1996). We were able to follow this process dynamically in the rat using microPET. Our data show that [18F]-ET-1 is rapidly cleared from the circulation within 2 min with a corresponding rapid accumulation in the lungs, consistent with receptor binding. The structure of ET-1, containing 21 amino acids linked by two disulphide bridges, is unique among mammalian bioactive peptides. Metabolic degradation of this peptide will result in abolition of receptor binding, for example, ET-1 will lose affinity to ET receptors with three orders of magnitude if the C-terminal Trp21 is removed (Kimura et al., 1988). Metabolism of [18F]-ET-1 to shorter sequences would therefore result in radioactive fragments with little or no affinity for ET receptors. Furthermore, the absence of 18F accumulation in bone indicates that the label did not undergo any significant defluorination over the time studied, suggesting that our kinetic data reflects binding of [18F]-ET-1 to ET receptors in the lung.

In vitro studies have shown that the ET-1/receptor complex is rapidly internalised following agonist stimulation (Marsault et al., 1993; Chun et al., 1995; Bremnes et al., 2000; Oksche et al., 2000). The ET-1/ETB complex is transported to the lysosomes for degradation, suggesting a mechanism for the clearance of ET-1 via this subtype (Bremnes et al., 2000; Oksche et al., 2000). Our kinetic data in vivo support these findings: postinjection of the ETB antagonist did not displace binding in the lung whereas pretreatment significantly reduced uptake, with levels comparable to previous observations using [125I]-ET-1 (Fukuroda et al., 1994; Gibson et al., 1999). The ex vivo analysis of lung tissue from rats pretreated with BQ788 revealed a shift in the distribution of the radioactivity compared to the controls, with more prominent binding to the vasculature where the ETA subtype predominates. The corresponding microPET images of the lung also suggest a more heterogeneous distribution indicative of binding to blood vessels in the lung.

In kidney, there was an initial fast accumulation of radioactivity that rapidly reached equilibrium within 10 min similar to the time–activity curve in the lung; the distribution in vivo was comparable to the pattern visualised in vitro in this and previous studies (Davenport et al., 1991) consistent with receptor binding. Treatment with the antagonist caused a significant reduction of uptake, in agreement with the ETB receptor being the predominant subtype (Gellai et al., 1994), to levels comparable to those obtained previously with BQ788 (Fukuroda et al., 1994; Gibson et al., 1999). However, after ∼20 min, a slow increase in radioactivity was detected within the kidney. Although this could be the result of internalisation, since the time course is different to that of the lung and liver, an additional factor in the kidney may be accumulation of metabolites.

In control animals, the time–activity curves for liver showed a fast accumulation of radioactivity similar to that seen in the lung and kidney. However, under conditions of ETB receptor blockade uptake increased in this organ. Interestingly, early dynamic data revealed an increase in time to reach equilibrium after pretreatment, suggesting blockade of ETB receptor-mediated uptake. This is supported by the observation in isolated perfused liver that binding to ETB receptors is the major route of clearance for ET-1 in single pass experiments (Dupuis et al., 1999). We cannot at this point conclude whether the later dynamic data, suggesting increased levels of binding to liver tissue, reflect increased levels of binding to ETA receptors in lipocytes (Housset et al., 1993) or an increase in metabolic activity in liver cells (Gandhi et al., 1993). Further investigations are needed to completely elucidate the pharmacokinetics of [18F]-ET-1 uptake in the liver; however, our initial data demonstrate the power of using PET in this type of study.

In conclusion, we have for the first time dynamically followed binding of ET-1 to ET receptors in vivo in the rat using microPET. Clearance of ET-1 was mediated by the ETB receptor in the lung, kidney and to a certain extent by the liver. Furthermore, these results suggest that clearance by the ETB receptor prevents binding of ET-1 to the heart. We hypothesise that this mechanism may be important in limiting the detrimental vasoconstrictor effect caused by upregulation of ET-1 in the vascular system associated with disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Adrian Carpenter, Mrs Rhoda Kuc and Mr Paul Burke for technical support and Dr Janet Maguire for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation, the Medical Research Council Technology Foresight (U.K. Government) and for the microPET a JREI grant from HEFCE and Merck Sharp and Dohme, Ltd.

Abbreviations

- BQ3020

N-acetyl-Leu-Met-Asp-Lys-Glu-Ala-Val-Tyr-Phe-Ala-His-Leu-Asp-Ile-Ile-Trp

- BQ788

N-cis-2,6-dimethylpiperidinocarbonyl-L-γ-methylleucyl-D-1-methoxycarbonyltryptophanyl-D-norleucine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- FR139317

(R)-2-[(R)-2-[(S)-2-[[1-(hexahydro-1H-azepinyl)]carbonyl]amino-4-methylpentanoyl]amino-3-[3-(1-methyl-1H-indoyl)]propionyl]amino-3-(2-pyridyl)propionic acid

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ROI

regions-of-interest

References

- ALEKSIC S., SZABO Z., SCHEFFEL U., RAVERT H.T., MATHEWS W.B., KERENYI L., RAUSEO P.A., GIBSON R.E., BURNS H.D., DANNALS R.F. In vivo labeling of endothelin receptors with [11C]L-753,037: studies in mice and a dog. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;42:1274–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREMNES T., PAASCHE J.D., MEHLUM A., SANDBERG C., BREMNES B., ATTRAMADAL H. Regulation and intracellular trafficking pathways of the endothelin receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17596–17604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATZIIOANNOU A.F. Molecular imaging of small animals with dedicated PET tomographs. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2002;29:98–114. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUN M., LIN H.Y., HENIS Y.I., LODISH H.F. Endothelin-induced endocytosis of cell surface ETA receptors. Endothelin remains intact and bound to the ETA receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10855–10860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., KUC R.E. Radioligand binding assays and quantitative autoradiography of endothelin receptors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002;206:45–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-289-9:045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., MORTON A.J., BROWN M.J. Localization of endothelin-1 (ET-1), ET-2, and ET-3, mouse VIC, and sarafotoxin S6b binding sites in mammalian heart and kidney. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1991;17 Suppl 7:S152–S155. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199100177-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., RUSSELL F.D.Endothelin converting enzymes and endothelin receptor localisation in human tissues Endothelin and its Inhibitors 2001Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 209–237.ed. Warner, T.D., pp [Google Scholar]

- DE NUCCI G., THOMAS R., D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P., ANTUNES E., WALDER C., WARNER T.D., VANE J.R. Pressor effects of circulating endothelin are limited by its removal in the pulmonary circulation and by the release of prostacyclin and endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:9797–9800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUPUIS J. Endothelin receptor antagonists and their developing role in cardiovascular therapeutics. Can. J. Cardiol. 2000;16:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUPUIS J., GORESKY C.A., FOURNIER A. Pulmonary clearance of circulating endothelin-1 in dogs in vivo: exclusive role of ETB receptors. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;81:1510–1515. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUPUIS J., SCHWAB A.J., SIMARD A., CERNACEK P., STEWART D.J., GORESKY C.A. Kinetics of endothelin-1 binding in the dog liver microcirculation in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G905–G914. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.4.G905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERTL G., BAUERSACHS J. Endothelin receptor antagonists in heart failure: current status and future directions. Drugs. 2004;64:1029–1040. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKURODA T., FUJIKAWA T., OZAKI S., ISHIKAWA K., YANO M., NISHIKIBE M. Clearance of circulating endothelin-1 by ETB receptors in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;199:1461–1465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANDHI C.R., HARVEY S.A., OLSON M.S. Hepatic effects of endothelin: metabolism of [125I]endothelin-1 by liver-derived cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;305:38–46. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., BENNETT T. Regional haemodynamic responses to intravenous and intraarterial endothelin-1 and big endothelin-1 in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1532–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Effects of bosentan (Ro 47-0203), an ETA-, ETB-receptor antagonist, on regional haemodynamic responses to endothelins in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994a;112:823–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T., DAVENPORT A.P., EDVINSSON L. Effects of an ET1-receptor antagonist, FR139317, on regional haemodynamic responses to endothelin-1 and [Ala11,15]Ac-endothelin-1 (6–21) in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994b;112:477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GELLAI M., DEWOLF R., PULLEN M., NAMBI P. Distribution and functional role of renal ET receptor subtypes in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1287–1294. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON R.E., FIORAVANTI C., FRANCIS B., BURNS H.D. Radioiodinated endothelin-1: a radiotracer for imaging endothelin receptor distribution and occupancy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1999;26:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYNES W.G., WEBB D.J. Endothelin as a regulator of cardiovascular function in health and disease. J. Hypertens. 1998;16:1081–1098. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUSSET C., ROCKEY D.C., BISSELL D.M. Endothelin receptors in rat liver: lipocytes as a contractile target for endothelin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:9266–9270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA K., IHARA M., NOGUCHI K., MASE T., MINO N., SAEKI T., FUKURODA T., FUKAMI T., OZAKI S., NAGASE T., NISHIKIBE M., YANO M. Biochemical and pharmacological profile of a potent and selective endothelin B-receptor antagonist, BQ-788. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTRÖM P., AIGBIRHIO F.I., CLARK J.C., DOWNEY S.P.M.J., PICKARD J.D., DAVENPORT A.P. Syntheses of the first endothelin-A- and -B-selective radioligands for positron emission tomography. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000;36 Suppl 1:S58–S60. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200036001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTRÖM P., HARRIS N.G., FRYER T.D., BARRET O., CLARK J.C., PICKARD J.D., DAVENPORT A.P. 18F-Endothelin-1, a positron emission tomography (PET) radioligand for the endothelin receptor system: radiosynthesis and in vivo imaging using microPET. Clin. Sci. 2002;103 Suppl 48:4S–8S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S004S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALRA P.R., MOON J.C.C., COATS A.J.S. Do results of the ENABLE (endothelin antagonist bosentan for lowering cardiac events in heart failure) study spell the end for non-selective endothelin antagonism in heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002;85:195–197. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARET F.E., KUC R.E., DAVENPORT A.P. Novel ligands BQ123 and BQ3020 characterize endothelin receptor subtypes ETA and ETB in human kidney. Kidney Int. 1993;44:36–42. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEDZIERSKI R.M., YANAGISAWA M. Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:851–876. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA S., KASUYA Y., SAWAMURA T., SHINMI O., SUGITA Y., YANAGISAWA M., GOTO K., MASAKI T. Structure–activity relationships of endothelin: importance of the C-terminal moiety. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;156:1182–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINAHAN P.E., ROGERS J.G. Analytic 3D image-reconstruction using all detected events. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1989;36:964–968. [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS J.S., ACHILEFU S., GARBOW J.R., LAFOREST R., WELCH M.J. Small animal imaging. Current technology and perspectives for oncological imaging. Eur. J. Cancer. 2002;38:2173–2188. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÜSCHER T.F., BARTON M. Endothelins and endothelin receptor antagonists: therapeutic considerations for a novel class of cardiovascular drugs. Circulation. 2000;102:2434–2440. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSAULT R., FEOLDE E., FRELIN C. Receptor externalization determines sustained contractile responses to endothelin-1 in the rat aorta. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:C687–C693. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAUCHI T., MASAKI T. Pathophysiology of endothelin in the cardiovascular system. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1999;61:391–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLENAAR P., O'REILLY G., SHARKEY A., KUC R.E., HARDING D.P., PLUMPTON C., GRESHAM G.A., DAVENPORT A.P. Characterization and localization of endothelin receptor subtypes in the human atrioventricular conducting system and myocardium. Circ. Res. 1993;72:526–538. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKSCHE A., BOESE G., HORSTMEYER A., FURKERT J., BEYERMANN M., BIENERT M., ROSENTHAL W. Late endosomal/lysosomal targeting and lack of recycling of the ligand-occupied endothelin B receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:1104–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETER M.G., DAVENPORT A.P. Characterization of the endothelin receptor selective agonist, BQ3020 and antagonists BQ123, FR139317, BQ788, 50235, Ro462005 and bosentan in the heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:455–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBB R.A., HANSON D.P., KARWOSKI R.A., LARSON A.G., WORKMAN E.L., STACY M.C. Analyze: a comprehensive, operator-interactive software package for multidimensional medical image display and analysis. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 1989;13:433–454. doi: 10.1016/0895-6111(89)90285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL F.D., DAVENPORT A.P. Secretory pathways in endothelin synthesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:391–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFRIN E.L., INTENGAN H.D., THIBAULT G., TOUYZ R.M. Clinical significance of endothelin in cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 1997;12:354–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAI Y.C., CHATZIIOANNOU A., SIEGEL S., YOUNG J., NEWPORT D., GOBLE R.N., NUTT R.E., CHERRY S.R. Performance evaluation of the microPET P4: a PET system dedicated to animal imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2001;46:1845–1862. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/7/308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU-WONG J.R., OPGENORTH T.J.The roles of endothelins in proliferations, apoptosis and angiogenesis Endothelin and its Inhibitors 2001Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 299–322.ed. Warner, T.D., pp [Google Scholar]