Abstract

Proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR2), expressed in capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons, plays a protective role in gastric mucosa. The present study evaluated gastric mucosal cytoprotective effect of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, a novel highly potent PAR2 agonist, in ddY mice and in wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background.

Gastric mucosal injury was created by oral administration of HCl/ethanol solution in the mice. The native PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2, administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 0.3–1 μmol kg−1 in combination with amastatin, an aminopeptidase inhibitor, but not alone, revealed gastric mucosal protection in ddY mice, which was abolished by ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons.

I.p. administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.1 μmol kg−1, without combined treatment with amastatin, exhibited gastric mucosal cytoprotective activity in ddY mice, the potency being much greater than SLIGRL-NH2 in combination with amastatin. This effect was also inhibited by capsaicin pretreatment.

Oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.003–0.03 μmol kg−1 also protected against gastric mucosal lesion in a capsaicin-reversible manner in ddY mice.

I.p. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.1–0.3 μmol kg−1 caused prompt salivation in anesthetized mice, whereas its oral administration at 0.003–1 μmol kg−1 was incapable of eliciting salivation.

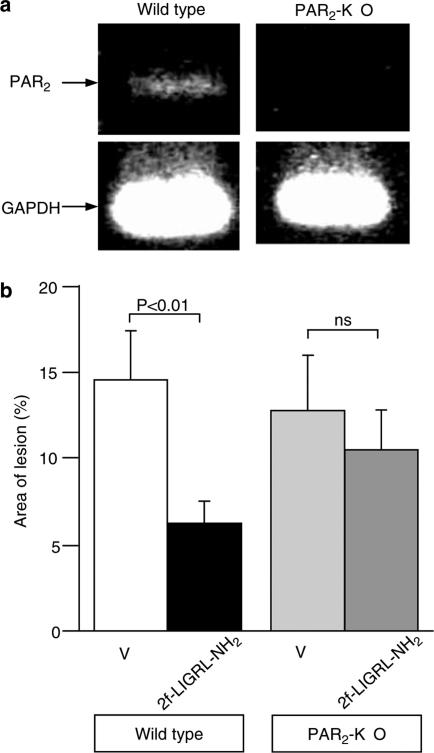

In wild-type, but not PAR2-knockout, mice of C57BL/6 background, i.p. administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 caused gastric mucosal protection.

Thus, 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is considered a potent and orally available gastric mucosal protective agent. Our data also substantiate a role for PAR2 in gastric mucosal protection and the selective nature of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2.

Keywords: Proteinase-activated receptor (PAR), a potent PAR2 agonist, gastric mucosal protection, salivation, PAR2-knockout mouse

Introduction

Proteinase-activated receptors (PARs) are a family of G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane domain receptors, consisting of four members, PARs 1–4 (Ossovskaya & Bunnett, 2004). Thrombin cleaves the N-terminal extracellular domain of PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4, but not PAR2, at the specific site and exposes the tethered ligand (‘SFLLRN—' for human PAR1, ‘TFRGAP—' for human PAR3 and ‘GYPGQV—' for human PAR4), which binds to the body of the receptor itself, resulting in receptor activation. Trypsin, tryptase and coagulation factors VIIa and Xa, but not thrombin, are capable of activating PAR2 by unmasking the N-terminal receptor-activating sequence (‘SLIGKV—' for human PAR2). PAR1, PAR2 and PAR4 can also be activated nonenzymatically by SFLLR, SLIGKV and GYPGQV, respectively, synthetic peptides based on the tethered ligand sequences (Ossovskaya & Bunnett, 2004). PARs, particularly PAR2 and PAR1, are distributed extensively in the mammalian body, participating in the modulation of various physiological functions (Hollenberg & Compton, 2002; Kawabata, 2002; 2003). In the gastrointestinal tract, both PAR2 and PAR1 modulates multiple gastric functions, being primarily protective in gastric mucosa (Kawabata et al., 2001a; 2003; 2004b; Kawabata, 2002; 2003; Kawao et al., 2002; 2003; Nishikawa et al., 2002). However, the mechanisms underlying the mucosal cytoprotective effects of PAR2 and PAR1 agonists appear to be greatly different. The mucosal cytoprotection by PAR2 agonists is mediated by activation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons but independent of endogenous prostanoids (Kawabata et al., 2001a), whereas PAR1 agonists cause prostanoid-dependent mucosal protection in a manner independent of sensory neurons (Kawabata et al., 2004b). Both PAR2 and PAR1 modulate gastrointestinal smooth muscle motility (Saifeddine et al., 1996; Corvera et al., 1997; Cocks et al., 1999; Kawabata et al., 2001b; Kawabata, 2003). PAR2, but not PAR1, is involved in the regulation of salivary and pancreatic exocrine secretion (Nguyen et al., 1999; Kawabata et al., 2000). There is also evidence that PAR2 plays a proinflammatory role in the colon (Cenac et al., 2002) and participates in visceral pain/hyperalgesia (Coelho et al., 2002; Kawao et al., 2004), although PAR2 is also anti-inflammatory under certain conditions (Fiorucci et al., 2001).

Both potent and selective agonists and antagonists for PAR2, if any, would be of therapeutic benefit and also useful as research tools. Although studies to screen peptide and/or nonpeptide antagonists for PAR2 have been performed, no appropriate PAR2 antagonists with satisfactory potency and selectivity are available so far. In contrast, some peptide agonists with improved potency and selectivity have been reported (Al-Ani et al., 1999), although nonpeptide agonists have yet to be developed. Strikingly, substitution of the N-terminal serine residue with a furoyl group in native PAR2-activating peptides causes dramatic enhancement of agonistic activity (Ferrell et al., 2003), leading to the development of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, the most potent nonenzyme agonist for PAR2 (Kawabata et al., 2004a). The potency of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 relative to the native peptide SLIGRL-NH2 is approximately 10, 20 and 100, as evaluated by the Ca2+ signaling assay in cultured cells, the vasorelaxation assay in rat superior mesenteric artery and the in vivo salivation assay in mice, respectively. The greatly different relative potency of these peptides in the in vitro and in vivo assay systems can be explained, in part, by the metabolic resistance of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 to aminopeptidase that rapidly degrades SLIGRL-NH2 (Kawabata et al., 2004a). McGuire et al. (2004) have independently reported the effectiveness of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-ornithine-NH2, which is almost equipotent to 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (Kawabata et al., 2004a). In the present study, we first examined whether parenteral administration of SLIGRL-NH2 could protect against gastric mucosal injury in ddY mice, as in Wistar rats (Kawabata et al., 2001a), and then evaluated and characterized the effectiveness of parenteral and oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 as a gastric mucosal cytoprotective agent, in comparison with the native peptide. Finally, we used wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background in order to obtain ultimate evidence for involvement of PAR2 in gastric mucosal protection and the selective nature of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2.

Methods

Animals

Male ddY mice weighing 20–25 g were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). Female wild-type (PAR2+/+) and PAR2-knockout (PAR2−/−) mice of C57BL/6 background were provided from Kowa Company (Tokyo, Japan) in the present experiments. The PAR2-knockout strain was prepared as described previously (Ferrell et al., 2003), and maintained by backcrossing heterozygous (PAR2+/−) males with C57BL/6 females at each generation. The genotype of the mice was confirmed by Southern blot analysis and PCR analysis of DNA obtained from tail biopsy. Homozygous (PAR2−/−) and wild-type (PAR2+/+) female mice generated from male and female PAR2+/− mice at backcross generation 8 were used at 8–12 weeks of age for the experiments. All animals were used with approval by the Kinki University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences' Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, on the basis of Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Approved by The Japanese Pharmacological Society.

Experimental gastric mucosal lesion in mice

After 18–24 h fast, conscious mice received oral administration of 150 mM HCl/60% ethanol in a volume of 0.3 ml, and were killed by cervical dislocation under ether anesthesia after 1 h. The stomach was then excised and fixed in 10% formalin solution. A digital photograph of the whole stomach was taken and analyzed for the size of the injured area by an image process program (Win Roof, Fukui, Japan) in a blinded evaluation. Lesion area is expressed as a percentage of the total area of the stomach except for the fundus. The test compounds including SLIGRL-NH2 and 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 5 min before or orally 1 h before challenge with oral administration of HCl/ethanol. Amastatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidase that degrades peptides, was administered i.p. immediately before i.p. injection with SLIGRL-NH2.

Salivation bioassay in mice

After 18–24 h fast, mice were anesthetized with i.p. administration of 1.5 g kg−1 urethane, and fixed in a supine position. According to the previously described method (Kawabata et al., 2004a), cotton was placed in the mouth of each mouse, and repeatedly replaced with new one every 5 min. The difference of the weight of cotton before and after the placement of the cotton in the mouth was defined as the amount of secreted and absorbed saliva for each 5-min interval. Salivation was monitored for 45 min after i.p. or oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2.

Ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons

Ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons was conducted by repeated administration of capsaicin. Briefly, the mice received subcutaneous administration of capsaicin in doses of 25, 50 and 50 mg kg−1 (125 mg kg−1 in total), three times, at 0, 6 and 32 h, respectively. Before each dose of capsaicin, the mice were anesthetized with i.p. pentobarbital at 45 mg kg−1. The mice were used for experiments 10 to 13 days after the last dose of capsaicin. In the preliminary experiments, the efficacy of capsaicin treatment was verified as described previously (Barrachina et al., 1997; Steinhoff et al., 2000).

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) for detection of PAR2 mRNA in mouse stomach

The wild-type and PAR2-knockout C57BL/6 background mice were killed by exsanguination under urethane anesthesia, and the stomach was excised. Total RNA, extracted from the tissue homogenate in the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, U.S.A.), was reverse-transcribed and then amplified by PCR using the RNA LA PCR kit (AMV) version 1.1 (Takara, Japan). The PCR primers were: 5′-CAACAGTAAAGGAAGAAGTCT-3′ and 5′-AGGCAGCACATCGTGGCAGGT-3′ for mouse PAR2; and 5′-TGCATCCTGCACCACCAACT-3′ and 5′-AACACGGAAGGCCATGCCAG-3′ for mouse GAPDH. The PCR reactions for PAR2 and GAPDH were allowed to proceed for 35 and 30 cycles, respectively (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 60 s). The PCR products (601 bp for PAR2 and 259 bp for GAPDH) were visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis followed by the ethidium bromide staining.

Drugs

SLIGRL-NH2 and 2-furol-LIGRL-NH2 were synthesized by a solid-phase method and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the composition and purity were determined by mass spectrometry. Amastatin and capsaicin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Capsaicin was dissolved in a solution containing 10% ethanol, 10% Tween-80 and 80% saline, and all other chemicals were dissolved in saline.

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test for two-group data and by Tukey's test for multiple-group data, and significance was accepted when P<0.05.

Results

Protective effect of i.p. administration of the native PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 on the gastric mucosal injury caused by HCl/ethanol in ddY mice

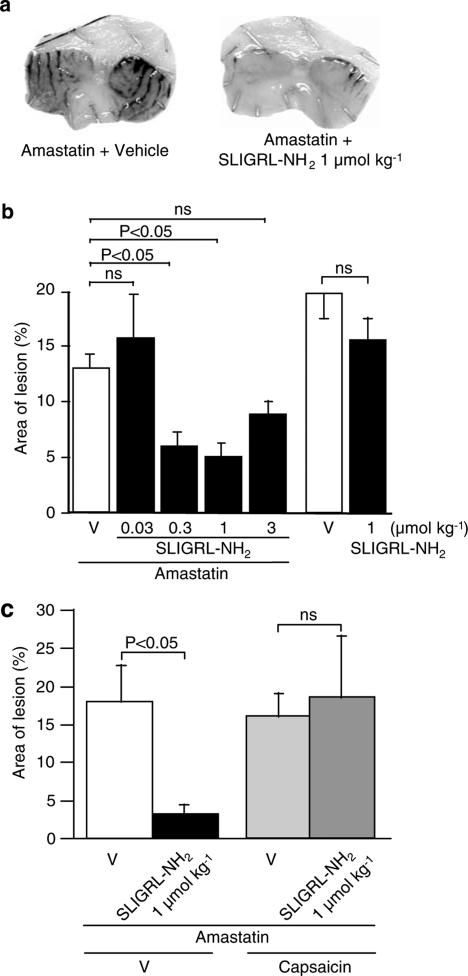

SLIGRL-NH2, when administered i.p. at 0.03–1 μmol kg−1 in combination with i.p. 2.5 mg kg−1 amastatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidase, protected against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal lesion in a dose-dependent manner in ddY mice, although the largest dose, 3 μmol kg−1, of SLIGRL-NH2 exhibited a relatively reduced protective activity (Figure 1a and b). In contrast, SLIGRL-NH2, given i.p. at 1 μmol kg−1 alone without combined administration of amastatin, produced no significant effects. These characteristics are in agreement with those shown in Wistar rats in the previous study (Kawabata et al., 2001a). The gastric mucosal cytoprotective effect of i.p. SLIGRL-NH2 at 1 μmol kg−1 in combination with amastatin disappeared when capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons were ablated by pretreatment with large doses of capsaicin (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Protective effects of parenteral administration of the native PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 on HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal injury in ddY mice. SLIGRL-NH2 at 0.03–3 μmol kg−1 in combination with amastatin at 2.5 μmol kg−1 was administered i.p. 5 min before oral administration of 150 mM HCl/60% ethanol in mice. (a) Typical photographs for the HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal injury in the mice pretreated with i.p. vehicle or SLIGRL-NH2 at 1 μmol kg−1 in combination with amastatin. (b) Dose-related gastric mucosal protective effect of i.p. SLIGRL-NH2 in combination with amastatin or alone in the mice. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 26 (vehicle+amastatin) or 10 to 15 (others) mice. (c) Effect of ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons on the gastric mucosal protection exerted by i.p. SLIGRL-NH2 at 1 μmol kg−1 in combination with amastatin. Ablation of the sensory neurons was achieved by pretreatment with repeated doses of capsaicin. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 4 to 5 mice. ns, not significant; V, vehicle.

Gastric mucosal cytoprotection caused by i.p. and oral administration of the potent PAR2-activating peptide 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 in ddY mice with HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury

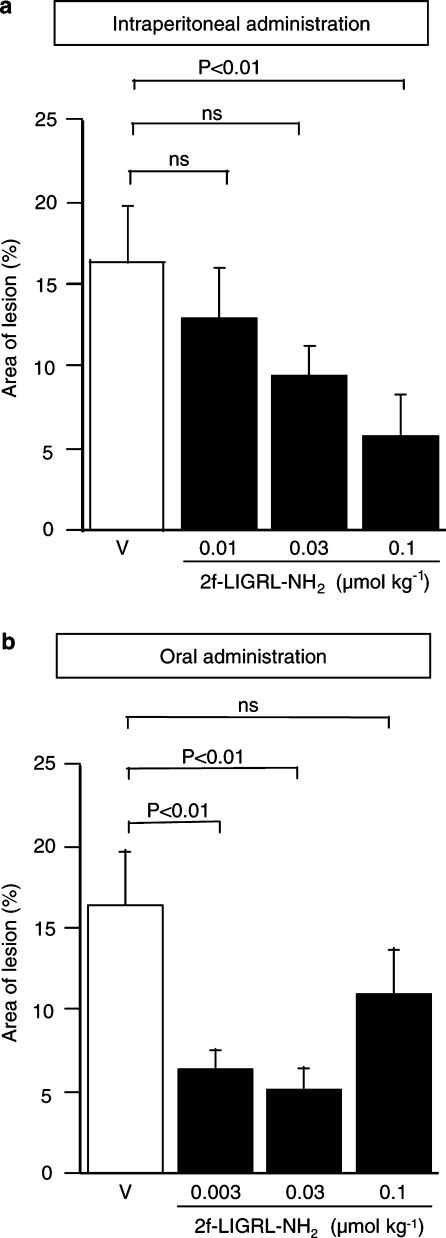

The potent PAR2-activating peptide 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, administered i.p. at 0.01–0.1 μmol kg−1, alone without combined administration with amastatin, exerted gastric mucosal protection in a dose-dependent manner in ddY mice with HCl/ethanol-induced mucosal lesion (Figure 2a). Of note is that, in our preliminary experiments, i.p. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 1 μmol kg−1 exhibited no significant protective activity (data not shown). Interestingly, 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.003–0.03 μmol kg−1, when administered orally 1 h before challenge with oral HCl/ethanol, revealed significant protective effects in the gastric injury model, although oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at the largest dose, 0.1 μmol kg−1, had no significant effect (Figure 2b). In our preliminary experiments, 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, when administered orally 15 or 30 min before oral HCl/ethanol, failed to exhibit protective effect (data not shown). Of note is that oral administration of SLIGRL-NH2 at 0.3–3 μmol kg−1 with or without combined administration of amastatin produced no significant gastric mucosal protection in ddY mice (data not shown). The gastric mucosal protective effect of either i.p. or oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (at 0.1 and 0.03 μmol kg−1 for i.p and oral doses, respectively) was inhibited by ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Dose-related protective effects of i.p. and oral administration of the potent PAR2-activating peptide 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 on HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal injury in ddY mice. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) at 0.01–0.1 μmol kg−1 and 0.003–0.1 μmol kg−1 was administered i.p. 5 min before (a) and orally 1 h before (b) oral administration of 150 mM HCl/60% ethanol, respectively, in the mice. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 10 to 18 mice. ns, not significant; V, vehicle.

Figure 3.

Effect of ablation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons on the mucosal protection caused by i.p. or oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) in the ddY mice with HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal injury. Ablation of the sensory neurons was achieved by pretreatment with repeated doses of capsaicin. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) at 0.1 and 0.03 μmol kg−1 was administered i.p. 5 min before (a) and orally 1 h before (b) oral administration of 150 mM HCl/60% ethanol, respectively, in the mice. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 8 to 10 mice. ns, not significant; V, vehicle.

Effects of i.p. or oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 on salivary exocrine secretion in mice

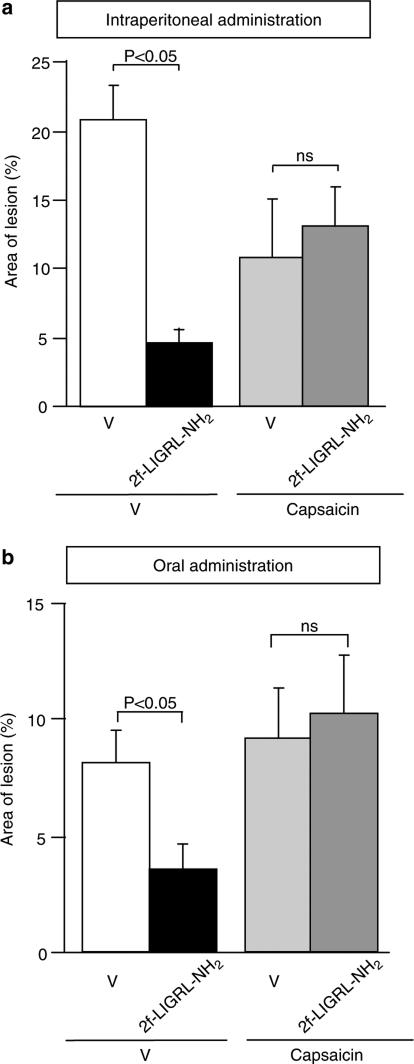

It is of importance to know if the gastric mucosal protection caused by orally administered 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is due to its local effect on the gastric mucosa or a consequence of its absorption and systemic distribution. Although 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 in blood stream is considered metabolically more stable than the native peptide SLIGRL-NH2 due to its resistance to aminopeptidase (Kawabata et al., 2004a), it is very difficult to determine and monitor the blood levels of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 because of its rapid clearance. In addition, problems to perform pharmacokinetic experiments include difficulty in repeated blood sampling in mice and insufficient sensitivity of usual HPLC analysis to detect blood levels of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 when given i.p. or orally at effective doses, 0.003–0.1 μmol kg−1. In this context, we monitored the time course of the effect of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 as a secretagogue for salivation in anesthetized mice. I.p. administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.1 μmol kg−1, the maximal dose in the gastric mucosal protection assay (see Figure 2a), caused prompt salivation, an effect peaking at 10 min and disappearing at 40 min (Figure 4a). The salivation caused by i.p. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is thus relatively delayed and persistent, compared to the effect of i.v. administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 in the previous study (Kawabata et al., 2004a). The dose-related experiments showed that 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 produced no additional effect at 0.3 μmol kg−1 and was inactive as a secretagogue at 0.03 μmol kg−1. On the other hand, oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 at 0.03 μmol kg−1 that was protective against gastric mucosal injury (see Figure 2b), produced no salivation for 45 min (Figure 4b). Lower and higher oral doses, 0.003, 0.3 and 1 μmol kg−1, of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 also failed to cause salivation (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Activity of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, administered i.p. or orally, as a secretagogue for saliva in ddY mice. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) was administered i.p. and orally, respectively, to the mouse under urethane anesthesia. (a and b) Time-related salivation activity of i.p. (a) and oral (b) administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) at 0.1 and 0.03 μmol kg−1, respectively, in the mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle. (c and d) Dose-related salivation activity of i.p. (c) and oral (d) administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) for 45 min in the mice. V, vehicle; ns, not significant. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 4 mice.

Protective effect of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 on HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury in wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background

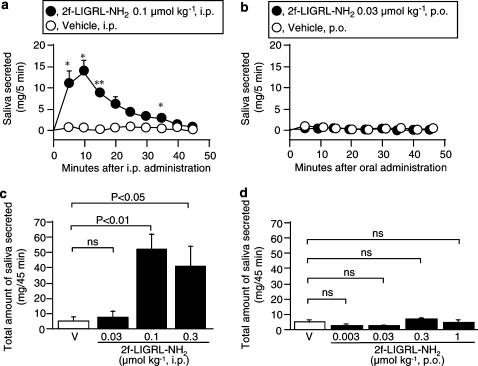

To obtain ultimate evidence for involvement of PAR2 in gastric mucosal protection and selective nature of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, we next employed wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background. The presence and absence of PAR2 mRNA in the stomach were confirmed in wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice, respectively (Figure 5a). In the wild-type mice, as in ddY mice, i.p. administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 significantly reduced the HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal lesion. In contrast, i.p. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 produced no significant gastric mucosal protection in PAR2-knockout mice.

Figure 5.

Protective effect of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 on the HCl/ethanol-evoked gastric mucosal injury in wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background. (a) Detection of mRNA for PAR2 in the stomach isolated from the wild-type, but not PAR2-knockout (PAR2-KO), mice. (b) 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 (2f-LIGRL-NH2) at 0.1 μmol kg−1 was administered i.p. 5 min before oral administration of 150 mM HCl/60% ethanol in the wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice. V, vehicle; ns, not significant. Data show the mean with s.e.m. from 14 to 18 mice.

Discussion

The present data show that the native PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 in combination with amastatin, administered i.p., exhibits gastric mucosal cytoprotective activity by activating capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons in mice, as in rats (Kawabata et al., 2001a), and that the novel potent PAR2 agonist 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, even without combined administration of amastatin, is much more potent as a gastric mucosal protective agent than SLIGRL-NH2. Of importance is that oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, but not SLIGRL-NH2, is also highly effective. It is clear from the data in the salivation assay that the gastric mucosal protection caused by oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is a result of its local effect on the gastric mucosa, but not its absorption followed by systemic distribution. Finally, the data obtained from the experiments employing wild-type and PAR2-knockout mice of C57BL/6 background provide ultimate evidence for involvement of PAR2 in gastric mucosal cytoprotection and selective nature of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2.

PAR2 plays multiple roles in gastric mucosa (Kawabata, 2002; 2003). Parenteral administration of PAR2-activating peptides causes prompt secretion of gastric mucus by activating capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons in rats, which is in agreement with their neurally mediated mucosal cytoprotective effect in rats and mice in the previous (Kawabata et al., 2001a) and present studies, respectively. The mechanisms underlying the evoked mucus secretion appear to involve activation of the CGRP-CGRP1 receptor pathway and the neurokinin-NK2 receptor pathway (Kawabata et al., 2001a). Nonetheless, PAR2 agonists exert various actions in the stomach that are independent of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons (Kawabata, 2002; 2003). Parenteral administration of PAR2 agonists suppresses carbachol-evoked gastric acid secretion by unknown mechanisms independent of sensory neurons (Nishikawa et al., 2002), and causes transient increase in gastric mucosal blood flow possibly by activating endothelial PAR2 in the gastric arterioles followed mainly by activation of the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) pathway (Kawabata et al., 2001a; 2003). These non-neuronal actions of PAR2 agonists might promote their neurally mediated gastric mucosal protective effect. In contrast, immunoreactive PAR2 is abundantly expressed in gastric mucosal chief cells, and PAR2 stimulation actually causes pepsinogen secretion (Kawao et al., 2002). Thus, the roles played by PAR2 in the gastric mucosa are complex, although PAR2 is considered primarily protective in the gastric mucosa (Kawabata, 2002; 2003). Since no appropriate PAR2 antagonist is available at present, our present evidence obtained from PAR2-knockout mice is critical to substantiate involvement of PAR2 in gastric mucosal cytoprotection.

The potent protective effect of i.p. 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 without combined administration of the aminopeptidase inhibitor amastatin, as shown in the present study, is considered to be due to the enhanced agonistic activity and improved metabolic resistance to aminopeptidase, compared with the native peptides (Kawabata et al., 2004a). The oral availability of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 as a gastric mucosal protective agent is particularly beneficial to consider its clinical application. In addition, the evidence that the protective effect of oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 may occur without its systemic distribution is also advantageous to avoid its side effects on organs other than the stomach. The finding that the oral effective dose range of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 was much lower than its i.p. effective doses also supports possible involvement of local protective effects of oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 in the stomach without systemic distribution, being preferable to consider therapeutic application. Of note is that oral administration of 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 itself in a dose range that was effective in the gastric mucosal protection assay, did not apparently cause any mucosal damage or inflammatory symptoms throughout the gastrointestinal tract (Kawabata et al., unpublished data), although intracolonic administration of PAR2 agonists may cause colonic inflammation and/or visceral hyperalgesia in mice or rats (Cenac et al., 2002; Coelho et al., 2002; Kawao et al., 2004).

The unusual present finding that both i.p. and/or oral administration of both the PAR2 agonists had no significant protective effect at high doses in mice is consistent to several previous reports concerning the gastric mucosal protective effect of agonists for PAR2 or PAR1 in rats and also the salivation by PAR2 agonists (Kawabata et al., 2000; 2001a; 2004b). Considering that PAR2 often plays a dual role, being pro- and anti-inflammatory, in other organs including the lung and colon (Cocks & Moffatt, 2001; Kawabata, 2002; 2003), it can be speculated that a possible proinflammatory effect of PAR2 agonists at high doses might overcome the protective effect in gastric mucosa. Another point to be addressed is that 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2, when administered i.p. 5 min before oral HCl/ethanol, produced protective effect, whereas it was effective when given orally 1 h, but not 15 or 30 min, before HCl/ethanol. Since the protective effect of oral 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is attributable to its local effect in gastric mucosa without systemic distribution, as mentioned above, it is likely that orally administered 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 might take more than 30 min to reach its possible effective sites through some barriers including mucus gel layers in the gastric mucosal surface before large dilution or washout with subsequent oral HCl/ethanol.

Based on our present findings, we conclude that PAR2 plays a protective role in gastric mucosa and propose that the novel PAR2 agonist 2-furoyl-LIGRL-NH2 is an orally available potent gastric mucosal protective agent.

Abbreviations

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- PAR2

proteinase-activated receptor-2

References

- AL-ANI B., SAIFEDDINE M., KAWABATA A., RENAUX B., MOKASHI S., HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2): development of a ligand-binding assay correlating with activation of PAR2 by PAR1- and PAR2-derived peptide ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;290:753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRACHINA M.D., MARTINEZ V., WANG L., WEI J.Y., TACHE Y. Synergistic interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin to reduce short-term food intake in lean mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:10455–10460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENAC N., COELHO A.M., NGUYEN C., COMPTON S., ANDRADE-GORDON P., MACNAUGHTON W.K., WALLACE J.L., HOLLENBERG M.D., BUNNETT N.W., GARCIA-VILLAR R., BUENO L., VERGNOLLE N. Induction of intestinal inflammation in mouse by activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:1903–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., MOFFATT J.D. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) in the airways. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;14:183–191. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., SOZZI V., MOFFATT J.D., SELEMIDIS S. Protease-activated receptors mediate apamin-sensitive relaxation of mouse and guinea pig gastrointestinal smooth muscle. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:586–592. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COELHO A.M., VERGNOLLE N., GUIARD B., FIORAMONTI J., BUENO L. Proteinases and proteinase-activated receptor 2: a possible role to promote visceral hyperalgesia in rats. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1035–1047. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORVERA C.U., DERY O., McCONALOGUE K., BOHM S.K., KHITIN L.M., CAUGHEY G.H., PAYAN D.G., BUNNETT N.W. Mast cell tryptase regulates rat colonic myocytes through proteinase-activated receptor 2. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1383–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI119658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRELL W.R., LOCKHART J.C., KELSO E.B., DUNNING L., PLEVIN R., MEEK S.E., SMITH A.J., HUNTER G.D., McLEAN J.S., MCGARRY F., RAMAGE R., JIANG L., KANKE T., KAWAGOE J. Essential role for proteinase-activated receptor-2 in arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:35–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI16913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIORUCCI S., MENCARELLI A., PALAZZETTI B., DISTRUTTI E., VERGNOLLE N., HOLLENBERG M.D., WALLACE J.L., MORELLI A., CIRINO G. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 is an anti-inflammatory signal for colonic lamina propria lymphocytes in a mouse model of colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13936–13941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241377298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., COMPTON S.J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVIII. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:203–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A. PAR-2: structure, function and relevance to human diseases of the gastric mucosa. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2002;4:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402004799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A. Gastrointestinal functions of proteinase-activated receptors. Life Sci. 2003;74:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KANKE T., YONEZAWA D., ISHIKI T., SAKA M., KABEYA M., SEKIGUCHI F., KUBO S., KURODA R., IWAKI M., KATSURA K., PLEVIN R. Potent and metabolically stable agonists for protease-activated receptor-2: evaluation of activity in multiple assay systems in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004a;309:1098–1107. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KINOSHITA M., NISHIKAWA H., KURODA R., NISHIDA M., ARAKI H., ARIZONO N., ODA Y., KAKEHI K. The protease-activated receptor-2 agonist induces gastric mucus secretion and mucosal cytoprotection. J. Clin. Invest. 2001a;107:1443–1450. doi: 10.1172/JCI10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., NAGATA N., KAWAO N., MASUKO T., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K. In vivo evidence that protease-activated receptors 1 and 2 modulate gastrointestinal transit in the mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001b;133:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., NAKAYA Y., KURODA R., WAKISAKA M., MASUKO T., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K. Involvement of EDHF in the hypotension and increased gastric mucosal blood flow caused by PAR-2 activation in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:247–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., NISHIKAWA H., KURODA R., KAWAI K., HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): regulation of salivary and pancreatic exocrine secretion in vivo in rats and mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:1808–1814. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., NISHIKAWA H., SAITOH H., NAKAYA Y., HIRAMATSU K., KUBO S., NISHIDA M., KAWAO N., KURODA R., SEKIGUCHI F., KINOSHITA M., KAKEHI K., ARIZONO N., YAMAGISHI H., KAWAI K. A protective role of protease-activated receptor 1 in rat gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2004b;126:208–219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAO N., HIRAMATSU K., INOI N., KURODA R., NISHIKAWA H., SEKIGUCHI F., KAWABATA A. The PAR-1-activating peptide facilitates pepsinogen secretion in rats. Peptides. 2003;24:1449–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAO N., IKEDA H., KITANO T., KURODA R., SEKIGUCHI F., KATAOKA K., KAMANAKA Y., KAWABATA A. Modulation of capsaicin-evoked visceral pain and referred hyperalgesia by protease-activated receptors 1 and 2. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;94:277–285. doi: 10.1254/jphs.94.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAO N., SAKAGUCHI Y., TAGOME A., KURODA R., NISHIDA S., IRIMAJIRI K., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K., HOLLENBERG M.D., KAWABATA A. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) in the rat gastric mucosa: immunolocalization and facilitation of pepsin/pepsinogen secretion. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1292–1296. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGUIRE J.J., SAIFEDDINE M., TRIGGLE C.R., SUN K., HOLLENBERG M.D. 2-furoyl-LIGRLO-amide: a potent and selective proteinase-activated receptor 2 agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;309:1124–1131. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGUYEN T.D., MOODY M.W., STEINHOFF M., OKOLO C., KOH D.S., BUNNETT N.W. Trypsin activates pancreatic duct epithelial cell ion channels through proteinase-activated receptor-2. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:261–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K., NISHIMURA S., TANAKA S., ARAKI H., AL-ANI B., HOLLENBERG M.D., KURODA R., KAWABATA A. Suppression by protease-activated receptor-2 activation of gastric acid secretion in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;447:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01892-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSSOVSKAYA V.S., BUNNETT N.W. Protease-activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:579–621. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIFEDDINE M., Al-ANI B., CHENG C.H., WANG L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Rat proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): cDNA sequence and activity of receptor-derived peptides in gastric and vascular tissue. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINHOFF M., VERGNOLLE N., YOUNG S.H., TOGNETTO M., AMADESI S., ENNES H.S., TREVISANI M., HOLLENBERG M.D., WALLACE J.L., CAUGHEY G.H., MITCHELL S.E., WILLIAMS L.M., GEPPETTI P., MAYER E.A., BUNNETT N.W. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat. Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]