Abstract

This study investigated whether the immediate and long-term effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) on monoamines in mouse brain are due to the parent compound and the possible contribution of a major reactive metabolite, 3,4-dihydroxymethamphetamine (HHMA), to these changes. The acute effect of each compound on rectal temperature was also determined.

MDMA given i.p. (30 mg kg−1, three times at 3-h intervals), but not into the striatum (1, 10 and 100 μg, three times at 3-h intervals), produced a reduction in striatal dopamine content and modest 5-HT reduction 1 h after the last dose. MDMA does not therefore appear to be responsible for the acute monoamine release that follows its peripheral injection.

HHMA does not contribute to the acute MDMA-induced dopamine depletion as the acute central effects of MDMA and HHMA differed following i.p. injection. Both compounds induced hyperthermia, confirming that the acute dopamine depletion is not responsible for the temperature changes.

Peripheral administration of MDMA produced dopamine depletion 7 days later. Intrastriatal MDMA administration only produced a long-term loss of dopamine at much higher concentrations than those reached after the i.p. dose and therefore bears little relevance to the neurotoxicity. This indicates that the long-term effect is not attributable to the parent compound. HHMA also appeared not to be responsible as i.p. administration failed to alter the striatal dopamine concentration 7 days later.

HHMA was detected in plasma, but not in brain, following MDMA (i.p.), but it can cross the blood–brain barrier as it was detected in the brain following its peripheral injection.

The fact that the acute changes induced by i.p. or intrastriatal HHMA administration differed indicates that HHMA is metabolised to other compounds which are responsible for changes observed after i.p. administration.

Keywords: MDMA, HHMA, 5-HT, dopamine, temperature, intrastriatal administration, mice, MDMA metabolism, neurotoxicity

Introduction

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy') is widely used as a recreational drug by young people, despite having been shown to be a potent neurotoxin in the brain of rodents and non-human primates (Green et al., 2003). MDMA administration produces two distinct actions in the brains of rats and mice: acute effects, which are reversible and consist of a major release of 5-HT and dopamine, and long-term effects which are persistent and are considered to reflect neurodegenerative changes. The long-lasting effects induced by MDMA are species-specific, in the sense that there are marked differences between the changes induced in rats and mice. When MDMA is administered to rats, it produces a pronounced selective long-term loss of 5-HT nerve terminals (Sharkey et al., 1991; Hewitt & Green, 1994; Colado et al., 1997; Sanchez et al., 2001; Schmued, 2003). In contrast, its administration to mice results in a marked long-term decrease of dopamine nerve terminals but little or no effect on 5-HT-containing neurones (Stone et al., 1987; Logan et al., 1988; O'Callaghan & Miller, 1994; Mann et al., 1997; Colado et al., 2001; O'Shea et al., 2001).

The acute effects of MDMA in rats appear to be produced by the action of the parent compound. However, there is good evidence to suggest that the long-term neurotoxicity results from the action of a metabolite, since MDMA administration directly into the brain at a similar or greater concentration than achieved by a neurotoxic dose given peripherally fails to induce damage (Esteban et al., 2001). This indicates that MDMA must be metabolised peripherally in order to produce compounds that induce free radical formation and neurotoxicity in the brain (Esteban et al., 2001).

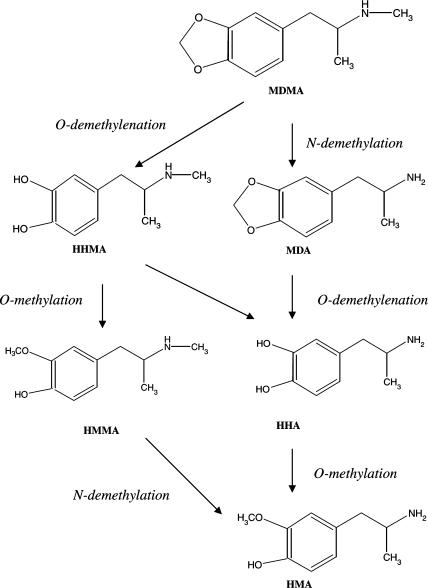

The identity of the neurotoxic metabolite or metabolites remains uncertain despite considerable research (see O'Shea et al., 2002; Green et al., 2003). Two major pathways seem to be involved in MDMA metabolism in humans and rats, O-demethylenation and N-demethylation (Figure 1). O-Demethylenation is catalysed by the cytochrome P450 mono-oxygenase system and leads to the formation of 3,4-dihydroxymethamphetamine (HHMA), an unstable reactive catechol derivative in both humans (Segura et al., 2001) and rats (Lim & Foltz, 1988; Cho et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Postulated pathways of MDMA metabolism (adapted from Green et al., 2003). Only structures considered in this paper are shown. MDMA: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; HHMA: 3,4-dihydroxymethamphetamine; MDA: 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine; HMMA: 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymethamphetamine; HMA: 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine.

The N-demethylation pathway gives rise to 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), which is a more potent serotonin neurotoxin than MDMA in rat brain. MDA is then further metabolised to compounds that are structurally similar to those formed by the O-demethylenation pathway of MDMA (Figure 1).

Since HHMA is an unstable, reactive compound (Segura et al., 2001), it seemed possible that it is either neurotoxic or a precursor of other neurotoxic metabolites in both rodents and humans.

In spite of the metabolism of MDMA in rats and humans being rather well documented, studies on the metabolic pathways of MDMA in mice are scarce, and to our knowledge there has been no study focused on determining whether either the acute or long-lasting changes in cerebral monoamine content following peripheral administration of MDMA are due to MDMA or a metabolite. This is particularly important given the fact that the neurotoxic action of MDMA appears to be different in mice to all other species examined, including rats (Sanchez et al., 2001; Schmued, 2003), guinea-pigs (Saadat et al., 2004) and possibly humans (McCann et al., 1998; Reneman et al., 2001; Buchert et al., 2003; Thomasius et al., 2003). We have, therefore, examined both the acute and long-term effects of MDMA on dopamine and 5-HT concentrations when injected either peripherally (i.p.) or into the striatum, and also examined the consequences of administering the major metabolite HHMA when given by either of these two routes.

The acute effect of each compound on rectal temperature was also determined because MDMA administration produces an acute hyperthermic effect in both rats and mice (Colado et al., 2001; Camarero et al., 2002; Orio et al., 2004), and while this action appears to be primarily due to cerebral dopamine release in the rat (Mechan et al., 2002) the mechanisms involved have never been examined in the mouse.

Methods

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Committee of the Universidad Complutense (following DC86/609/EU).

Animals, drug administration and experimental protocol

Adult male C57BL/6J mice (Harlan Iberica, Barcelona, Spain) weighing 25–30 g were used. They were housed in groups of 10, in conditions of constant temperature (21±2°C) and a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 h) and given free access to food and water.

The following drugs were used: (±) MDMA HCl (Ultrafine Chemicals Ltd, Manchester, U.K.) and (±) HHMA (Pizarro et al., 2002a). Mice were injected with MDMA or HHMA either intrastriatally (1, 10 and 100 μg) or i.p. (30 mg kg−1) at 3 h intervals for a total of three injections. Animals were killed 1 h (acute effect) or 7 days (long-term effect) after the last dose. The i.p. dose and the time course for killing the animals were based on previous studies where it was shown that MDMA induces acute and long-term changes in brain monoamine content at these times (O'Shea et al., 2001; Camarero et al., 2002). The same dose of HHMA was chosen since this is the maximum amount of HHMA that could be formed from MDMA. MDMA and HHMA were dissolved in 0.9% w v−1 NaCl (saline) and injected i.p. in a volume of 10 ml kg−1. When administered into the striatum, both MDMA and HHMA were dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). HHMA was provided dissolved in ethanol. An aliquot of this was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen and reconstituted in PBS. Control animals were injected with saline (i.p.) or PBS (intrastriatal). Doses are always quoted in terms of the base.

Measurement of rectal temperature

Temperature was measured using a digital readout thermocouple (Type K thermometer, Portec, U.K.) with a resolution of ±0.1°C and accuracy of ±0.2°C, which was attached to a CAC-005 Rodent Sensor inserted 2 cm into the rectum of the mouse, the animal being lightly restrained by holding in the hand. A steady readout was obtained within 10 s of probe insertion.

Implantation of a guide cannula in the striatum

Four days before the experiment, mice were anaesthetised with pentobarbitone (Euta-Lender, 40 mg kg−1) and secured in a Kopf stereotaxic frame with the tooth bar at 3.3 mm below the interaural zero. A guide cannula was implanted in the right side of the brain according to the following co-ordinates: +0.7 mm from the interaural line, −2.0 mm lateral to the midline and −2.3 mm below the skull for the striatum (König & Klippel, 1963). The cannula was secured to the skull as described by Baldwin et al. (1994). On the day of the experiment, a 28 G injector (Plastics One, U.S.A.) was inserted into the guide cannulae such that the tip of the injector protruded 1 mm from the end of the guide cannula.

Measurement of monoamines and their metabolites in cerebral tissue

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation and decapitation, the brains rapidly removed, and cortex, hippocampus and striatum dissected out on ice. Tissue was homogenised and 5-HT, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), dopamine, homovanillic acid (HVA) and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) measured by HPLC. Dopamine and metabolite concentrations were only determined in the striatum. Briefly, the mobile phase consisted of KH2PO4 (0.05 M), octanesulphonic acid (0.16 mM), EDTA (0.1 mM) and methanol (16%), and was adjusted to pH 3 with phosphoric acid, filtered and degassed. The flow rate was 1 ml min−1 and the working electrode potential was set at +0.4 V.

The HPLC system consisted of a pump (Waters 510) linked to an automatic sample injector (Loop 200 μl, Waters 717 plus Autosampler), a stainless steel reversed-phase column (Spherisorb ODS2, 5 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm2) fitted with a precolumn, and a coulometric detector (Coulochem II, Esa, U.S.A.). The current produced was monitored by using an integration software package (Unipoint, Gilson).

Measurement of MDMA and HHMA in plasma and striatum

Plasma samples (100 μl) and striatal homogenate samples (200 μl) were analysed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and HPLC with electrochemical detection. MDMA, MDA, HHMA, HMMA and HMA concentrations in plasma and striatal homogenate samples were determined following a previously described method based on an enzymatic hydrolysis of samples and a solid–liquid extraction with Bond Elut Certify® columns and analysis using GC-MS (Pizarro et al., 2002b).

The presence of HHMA in plasma and striatal homogenate was determined by using a standardised previously published method (Segura et al., 2001). An acidic hydrolysis was performed before a solid–liquid extraction using strong cation exchange (SCX®) columns followed by HPLC with electrochemical detection.

Statistics

Data from the monoamine studies were analysed using an unpaired Student's t-test and a one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test when a significant F-value was obtained. Statistical analyses of the temperature measurements were performed using the statistical computer package BMDP/386 Dynamic (BMDP Statistical Solutions, Cork, Eire). Data were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures (program 2 V) or, where missing values occurred, an unbalanced repeated-measure model (program 5 V) was used. Both used treatment as the between-subjects factor and time as the repeated measure. ANOVA were performed on both pre- and post-treatment data.

Results

Acute effect of MDMA on dopamine and 5-HT content after i.p. or intrastriatal administration

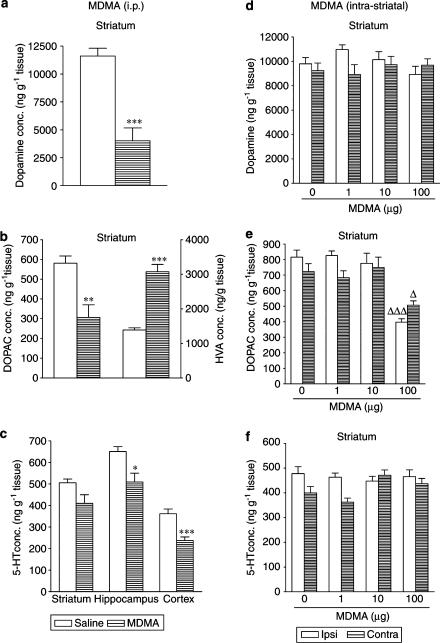

Administration of MDMA (30 mg kg−1 i.p.) three times, every 3 h, produced an acute reduction of dopamine (Figure 2a) and DOPAC (Figure 2b) content and an increase in the HVA (Figure 2b) concentration in the striatum 1 h after the final injection. There was also a modest reduction in 5-HT levels in the hippocampus and cortex (Figure 2c), but the 5-HIAA concentration was unaltered (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Immediate effects induced by repeated administration of MDMA, given intraperitoneally (30 mg kg−1) or intrastriatally (1, 10 and 100 μg) on the concentrations of dopamine (a, d) and DOPAC acid (b, e) in striatum and of 5-HT in striatum, hippocampus and cortex (c, f). Each dose was injected three times at 3-h intervals and mice killed 1 h after last injection. The results are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=5–9). Differences from saline: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Differences from the corresponding ipsi- and contralateral side of saline-treated animals: ΔP<0.05, ΔΔΔP<0.001.

In contrast, intrastriatal administration of MDMA (1, 10 and 100 μg) three times, every 3 h, produced no change in either the striatal dopamine (Figure 2d) or 5-HT content of the striatum (Figure 2f), hippocampus or cortex (data not shown) in either the ipsi- or contralateral side to the injection. This lack of effect was also observed on the brain concentration of 5-HIAA and HVA (data not shown), the only change seen being a decrease in DOPAC (Figure 2e) content in the ipsi- and contralateral striatum 1 h after the last administration of 100 μg MDMA.

Long-term effect of MDMA on dopamine and 5-HT content after i.p. or intrastriatal administration

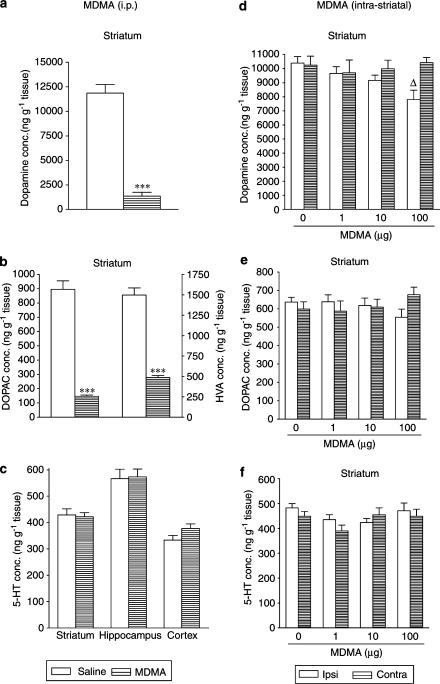

Administration of MDMA (30 mg kg−1 i.p.) three times, every 3 h, produced a long-term depletion of striatal concentration of dopamine (Figure 3a), DOPAC and HVA (Figure 3b). There was no change in 5-HT (Figure 3c) or 5-HIAA (data not shown) concentration in any of the areas studied.

Figure 3.

Long-term effects induced by repeated administration of MDMA, given intraperitoneally (30 mg kg−1) or intrastriatally (1, 10 and 100 μg) on the concentrations of dopamine (a, d) and DOPAC acid (b, e) in striatum and of 5-HT in striatum, hippocampus and cortex (c, f). Each dose was injected three times at 3-h intervals and mice killed 7 days after last injection. The results are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=6–9). Difference from saline: ***P<0.001. Difference from the corresponding ipsilateral side of saline-treated animals: ΔP<0.05.

Intrastriatal administration of MDMA (1, 10 and 100 μg) three times, every 3 h, produced no long-term effects in the 5-HT content in the striatum (Figure 3f), hippocampus or cortex (data not shown) in either the ipsi- or contralateral side to the injection. A lack of effect was also observed in the brain concentrations of 5-HIAA (data not shown), DOPAC (Figure 3e) and HVA (data not shown). The dopamine concentration was only reduced in the ipsilateral striatum 7 days after administration of the highest dose of MDMA (100 μg) (Figure 3d).

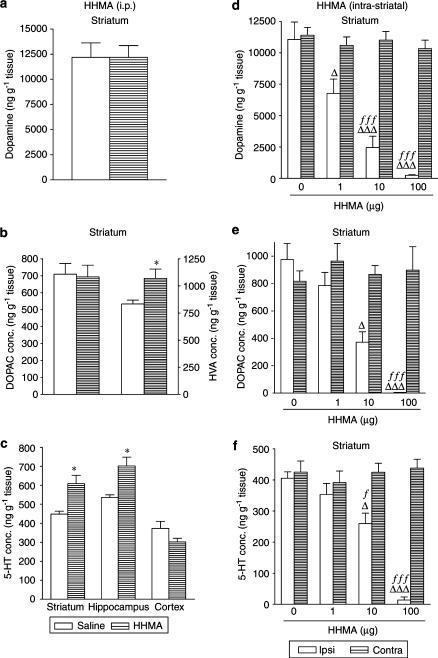

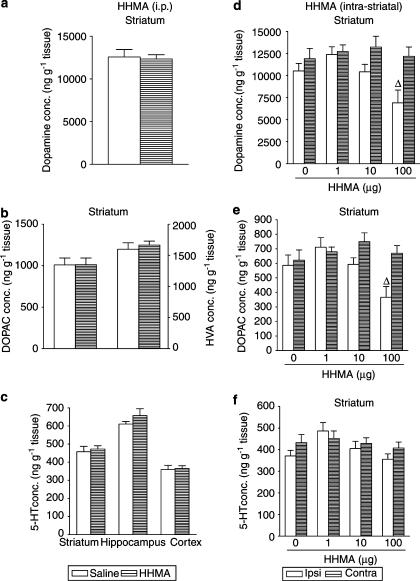

Acute effect of HHMA on dopamine and 5-HT content after i.p. or intrastriatal administration

Intraperitoneal administration of HHMA (30 mg kg−1) three times, every 3 h, produced no change in the striatal concentration of dopamine (Figure 4a) and DOPAC (Figure 4b) 1 h after the final dose, but did produce a rise in the content of HVA (Figure 4b). In addition, there was an increase in the content of 5-HT (Figure 4c) and 5-HIAA (data not shown) in both hippocampus and striatum.

Figure 4.

Immediate effects induced by repeated administration of HHMA, given intraperitoneally (30 mg kg−1) or intrastriatally (1, 10 and 100 μg) on the concentrations of dopamine (a, d) and DOPAC acid (b, e) in striatum and of 5-HT in striatum, hippocampus and cortex (c, f). Each dose was injected three times at 3-h intervals and mice killed 1 h after last injection. The results are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=5–9). Difference from saline: *P<0.05. Differences from the corresponding ipsilateral side of saline-treated animals: ΔP<0.05, ΔΔΔP<0.001. Differences from the corresponding contralateral side of HHMA-treated animals: fP<0.05, fffP<0.001.

In contrast, intrastriatal administration of HHMA (1, 10 and 100 μg) three times, every 3 h, resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in the striatal concentration of dopamine (Figure 4d) and its metabolites, DOPAC (Figure 4e) and HVA (data not shown). HHMA also decreased the 5-HT content in the striatum (Figure 4f) and cortex (data not shown) at the highest doses, but did not alter the 5-HIAA concentration in any of the regions examined (data not shown).

Long-term effect of HHMA after i.p. or intrastriatal administration

Intraperitoneal administration of HHMA (30 mg kg−1) three times, every 3 h, produced no change in the striatal content of dopamine (Figure 5a) or its metabolites (Figure 5b). The concentration of 5-HT (Figure 5c) and 5-HIAA (data not shown) in the striatum, hippocampus and cortex was also unchanged. However, when HHMA was injected into the striatum, it caused a reduction in dopamine (Figure 5d) and DOPAC (Figure 5e) concentration at the highest dose tested. Neither the striatal concentration of HVA (data not shown) nor the indole content of the striatum (Figure 5f), hippocampus and cortex (data not shown) were modified.

Figure 5.

Long-term effects induced by repeated administration of HHMA, given intraperitoneally (30 mg kg−1) or intrastriatally (1, 10 and 100 μg) on the concentrations of dopamine (a, d) and DOPAC acid (b, e) in striatum and of 5-HT in striatum, hippocampus and cortex (c, f). Each dose was injected three times at 3-h intervals and mice killed 7 days after last injection. The results are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=5–10). Difference from the corresponding ipsilateral side of saline-treated animals: ΔP<0.05.

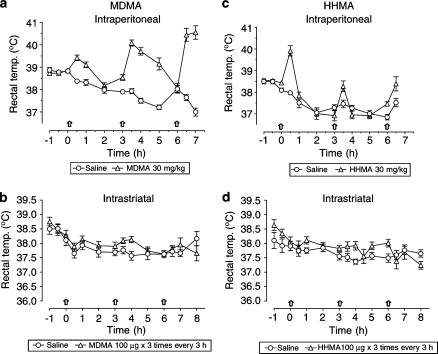

Effect of MDMA and HHMA on rectal temperature

Peripheral MDMA administration produced a modest hyperthermic response after the first dose, the effect being more pronounced after the second and third injections (Figure 6a). In contrast, MDMA administration into the striatum did not cause any change in rectal temperature (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Rectal temperature of animals injected with MDMA or HHMA, intraperitoneally (30 mg kg−1) or intrastriatally (100 μg) three times at 3-h intervals. Each value is the mean±s.e.m. of 12–18 mice. Intraperitoneal administration of MDMA or HHMA significantly increased the temperature compared to saline treatment (F(1,26)=218.8, P<0.001 and F(1,26)=11.16, P<0.001, respectively).

HHMA also produced hyperthermia after i.p. administration, the effect being more pronounced after the first dose (Figure 6c). No effect was observed when the compound was given intrastriatally (Figure 6d).

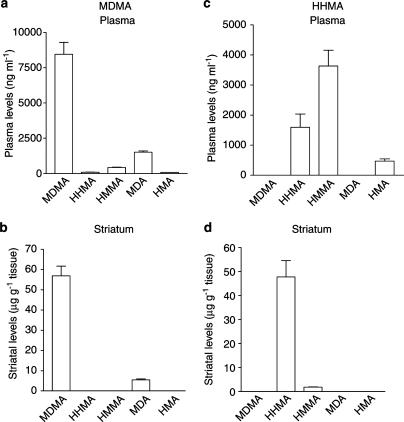

Plasma and striatal concentrations of MDMA and metabolites following i.p. injection of MDMA and HHMA

Mice were injected three times every 3 h with MDMA or HHMA and blood collected 60 min after the last injection for measurement of MDMA, HHMA, HMMA, MDA and HMA.

After i.p. injection of MDMA, the plasma levels of the parent compound were 450% higher than MDA and 1900% higher than those of HMMA. The levels of HHMA and HMA were very similar and represent 1 and 5% of MDMA and MDA, respectively (Figure 7a). In the striatum, only MDMA and MDA were detected, the levels of MDMA being 940% higher than those of MDA (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Plasma and striatal levels of MDMA and HHMA and metabolites 1 h after intraperitoneal injection of (a, b) MDMA (30 mg kg−1) or (c, d) HHMA (30 mg kg−1). The absence of bar for a given compound means that it was not detected.

After i.p. injection of HHMA, the plasma levels of the parent compound were approximately half those of HMMA. HMA was also detected but levels were only a small proportion of HMMA (Figure 7c). In the striatum, both HHMA and HMMA were detected, the levels of the former being substantially higher than the latter (Figure 7d).

Discussion

Acute and long-term effects of MDMA

This study is the first to suggest that the rapid release in dopamine and 5-HT, which has been found to occur in several areas of the mouse brain following the peripheral administration of MDMA (O'Shea et al., 2001; Camarero et al., 2002), may not to be due to the parent compound. No effect on either dopamine or 5-HT content was seen when MDMA was injected directly into the striatum, even at a high concentration. This lack of effect contrasts strongly with the action of MDMA in rat brain since its effects on monoamine release were qualitatively similar after both i.p. and intrahippocampal administration (Esteban et al., 2001; Mechan et al., 2002). Thus, when MDMA was given to rats by the intraperitoneal route, there is an increase in 5-HT release (Mechan et al., 2002) and, similarly, when given directly through a microdialysis probe, an increase in the extracellular content of 5-HT was observed (Esteban et al., 2001). In mice, i.p. MDMA produced an acute increase in extracellular dopamine (Camarero et al., 2002), which is presumably reflected by a reduction in tissue dopamine content (this paper); however, when given into the striatum, the tissue content of dopamine 1 h after the last MDMA injection was unaltered. These results appear to reflect a lack of effect on dopamine release, but further microdialysis studies should allow us to determine if short-lived release of dopamine is occurring after each of the three MDMA administrations.

Our study indicates that the long-term effects on brain monoamine concentrations observed in mice after repeated administration of MDMA are also unlikely to be due to the parent compound. This conclusion is based on the observation that the long-lasting depletion in the striatal dopamine concentration induced by repeated i.p. administration was not observed when the drug was injected into the striatum at a dose which produced a striatal MDMA concentration much higher than that reached after repeated i.p. administration of MDMA at 30 mg kg−1. The striatal concentration of MDMA 1 h after the last i.p. administration is 0.057 μg mg−1 tissue. Since the striatum weighs approximately 15 mg (and assuming that there is no distribution of the drug), the intrastriatal dose regimens of 3, 30 and 300 μg would have produced MDMA concentrations of, respectively, 0.2, 2 and 20 μg mg−1 tissue, concentrations that are 3.5, 35 and 350 times higher than that induced by an i.p. neurotoxic dose of MDMA. At 7 days after this dose regime, only the highest dose produced a small decrease in the striatal dopamine concentration, and this dose is much higher than that following i.p. administration. These results are similar to those previously observed in rats when it was also shown that the long-term loss of 5-HT nerve terminals induced by MDMA in the rat brain was not due to the original compound (Esteban et al., 2001), and indicate that in both species MDMA must be transformed peripherally to a metabolic compound which then crosses the blood–brain barrier and produces the neurotoxic damage.

Acute and long-term effects of HHMA

In an attempt to identify this neurotoxic metabolite, we examined the effects of injecting HHMA, a reactive metabolite formed by O-demethylenation. However, it appears unlikely that this compound is responsible for either the immediate or the long-term effects on brain monoamines in mice. Firstly, the i.p. administration of MDMA did not give rise to detectable levels of HHMA in the striatum 1 h after the last MDMA dose. However, since the compound is very reactive, but short lived (Segura et al., 2001), this observation does not preclude it having a crucial role in producing neurotoxic damage. Secondly, and significantly, the acute effects of MDMA and HHMA were different when the compounds were given i.p. Thus, 1 h after the last i.p. injection of HHMA, there was an increase in the striatal HVA content and indole concentration in the striatum and hippocampus, while the immediate effects produced by repeated MDMA injection consisted of a marked depletion of dopamine and DOPAC concentration in the striatum and a reduction in 5-HT content in hippocampus and cortex. The long-term effects of MDMA and HHMA also differed. HHMA given i.p. did not produce any change in the striatal dopamine concentration 7 days later, while MDMA produced substantial dopamine loss. There is some evidence in rats that this compound may also not be neurotoxic in that species (Johnson et al., 1992).

HHMA is formed in the periphery after MDMA administration, but the plasma concentrations are very low, possibly due to its rapid transformation to HMMA since plasma levels of HMMA are substantially higher than those of HHMA. Nevertheless, neither of these metabolites reached detectable levels in brain after i.p. administration of MDMA. Interestingly, HHMA does produce a long-lasting depletion of dopamine and DOPAC, but only when injected directly into the striatum at the highest tested concentration (300 μg total dose).

The immediate effects induced by HHMA also differed depending on the route of administration. After i.p. injection, HHMA produced no change in striatal dopamine concentration 1 h later, but it increased striatal and hippocampal 5-HT levels. However, when injected into the striatum, it caused an immediate, dose-dependent depletion of both striatal dopamine and 5-HT. Although HHMA is a highly polar compound, it crossed the blood–brain barrier and appeared in striatal tissue 1 h after the final injection. The fact that the acute changes induced by i.p. or intrastriatal HHMA administration are different indicates that HHMA when given peripherally is metabolised to another compound which may be responsible for both the acute changes in 5-HT and dopamine concentrations and probably for the changes in body temperature. The main metabolic pathway of HHMA in the periphery is O-methylation to form HMMA, whose levels exceeded 125% those of the parent compound 1 h after last HHMA i.p. injection. A similar observation has been made in rats, where HHMA appears to be totally converted to HMMA (Lim & Foltz, 1988). However, HMMA does not cross the blood–brain barrier as readily as HHMA, since the amount of this compound present in the striatum after HHMA i.p. administration is only 4% of HHMA.

Our data also reveal that a main metabolic pathway of MDMA in mice seems to be demethylation to form MDA, not demethylenation to form HHMA. After i.p. MDMA administration, the levels of MDA are 200% higher than those of HHMA+HMMA. As MDA crosses the blood–brain barrier, further studies are required to study the involvement of MDA in the acute and long-term changes induced by MDMA in mice.

Effect of MDMA and HHMA on rectal temperature

Both MDMA and HHMA induced a hyperthermic response immediately after each of the three doses. This effect was not observed when the drugs were given into the brain, which might indicate that the rise in rectal temperature is not due to the parent (original) compound. However, this may not be so, since MDMA and HHMA were administered into the striatum and, therefore, were unlikely to diffuse to the preoptic region of the hypothalamus, which is the major site of thermoregulation (Kluger, 1991) to cause hyperthermia. It is worthwhile mentioning that peripheral MDMA administration induces the activation of the hypothalamic axis reflected by increased c-fos expression in the supraoptic and median preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (Stephenson et al., 1999).

In rats, it has been proposed that the hyperthermia induced by MDMA could be due to the massive and acute dopamine release and subsequent activation of D1 receptors (Mechan et al., 2002). In mice, MDMA also induces an increase in dopamine release, but this change appears to be unconnected to the acute hyperthermia since pretreatment with the dopamine transporter blocker, GBR12909, enhanced the MDMA-induced extracellular dopamine concentration but did not alter the hyperthermic response (Camarero et al., 2002). In addition, HHMA also increased rectal temperature but did not alter brain dopamine concentration. These data indicate that MDMA induces an increase in the rectal temperature of the rats and mice through different mechanisms.

To our knowledge, mice do not provide a good model of the probable human neurotoxicity induced by MDMA as the primary mouse toxicity involves dopamine not 5-HT depletion. Therefore, this study of HHMA does not have any direct implications for our understanding of human MDMA neurotoxicity. However, they contribute to a greater understanding of why neurones are affected differently by the same amphetamines in different species.

Acknowledgments

M.I.C. thanks Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (Grant SAF2001-1437), Ministerio de Sanidad (Grant FIS02/1885, Grant G03/005), Plan Nacional sobre Drogas (Ministerio del Interior) and Fundacion Mapfre Medicina for financial support. V.S. thanks FIS for a studentship.

Abbreviations

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- HHA

3,4-dihydroxyamphetamine

- HHMA

3,4-dihydroxymethamphetamine

- 5-HIAA

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid

- HMA

4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine

- HMMA

4-hydroxy-3-methoxymethamphetamine

- HVA

homovanillic acid

- MDA

3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine

- MDMA

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

References

- BALDWIN H.A., WILLIAMS J.L., SNARES M., FERREIRA T., CROSS A.J., GREEN A.R. Attenuation by chlormethiazole administration of the rise in extracellular amino acids following focal ischaemia in the cerebral cortex of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:188–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCHERT R., THOMASIUS R., NEBELING B., PETERSEN K., OBROCKI J., JENICKE L., WILKE F., WARTBERG L., ZAPLETALOVA P., CLAUSEN M. Long-term effects of ‘ecstasy' use on serotonin transporters of the brain investigated by PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2003;44:375–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMARERO J., SANCHEZ V., O'SHEA E., GREEN A.R., COLADO M.I. Studies, using in vivo microdialysis, on the effect of the dopamine uptake inhibitor GBR 12909 on 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (‘ecstasy')-induced dopamine release and free radical formation in the mouse striatum. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:961–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHO A.K., HIRAMATSU M., DISTEFANO E.W., CHANG A.S., JENDEN D.J. Stereochemical differences in the metabolism of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in vitro and in vivo: a pharmacokinetic analysis. Drug Metab. Disposition. 1990;18:686–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLADO M.I., CAMARERO J., MECHAN A.O., SÁNCHEZ V., ESTEBAN B., ELLIOTT J.M., GREEN A.R. A study of the mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic action of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy') on dopamine neurones in mouse brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1711–1723. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLADO M.I., O'SHEA E., GRANADOS R., MURRAY T.K., GREEN A.R. In vivo evidence for free radical involvement in the degeneration of rat brain 5-HT following administration of MDMA (‘ecstasy') and p-chloroamphetamine but not the degeneration following fenfluramine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:889–900. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESTEBAN B., O'SHEA E., CAMARERO J., SANCHEZ V., GREEN A.R., COLADO M.I. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine induces monoamine release, but not toxicity, when administered centrally at a concentration occurring following a peripherally injected neurotoxic dose. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:251–260. doi: 10.1007/s002130000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN A.R., MECHAN A.O., ELLIOTT J.M., O'SHEA E., COLADO M.I. The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy') Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:463–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEWITT K.E., GREEN A.R. Chlormethiazole, dizocilpine and haloperidol prevent the degeneration of serotonergic nerve terminals induced by administration of MDMA (‘Ecstasy') to rats. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1589–1595. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON M., ELAYAN I., HANSON G.R., FOLTZ R.L., GIBB J.W., LIM H.K. Effects of 3,4-dihydroxymethamphetamine and 2,4,5-trihydroxymethamphetamine, two metabolites of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, on central serotonergic and dopaminergic systems. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:337–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLUGER M.J. Fever: role of pyrogens and cryogens. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:93–127. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KÖNIG J.F.R., KLIPPEL R.A. The Rat Brain. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Forebrain and Lower Parts of the Brain Stem. New York: Robert E Krieger Publishing Co. Inc; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- LIM H.K., FOLTZ R.L. In vivo and in vitro metabolism of 3,4-(methylenedioxy)methamphetamine in the rat: identification of metabolites using an ion trap detector. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1988;1:370–378. doi: 10.1021/tx00006a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOGAN B.J., LAVERTY R., SANDERSON W.D., YEE Y.B. Differences between rats and mice in MDMA (methylenedioxymethylamphetamine) neurotoxicity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;152:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANN H., LADENHEIM B., HIRATA H., MORAN T.H., CADET J.L. Differential toxic effects of methamphetamine (METH) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in multidrug-resistant (mdr1a) knockout mice. Brain Res. 1997;769:340–346. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00754-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCANN U.D., SZABO Z., SCHEFFEL U., DANNALS R.F., RICAURTE G.A. Positron emission tomographic evidence of toxic effect of MDMA (‘Ecstasy') on brain serotonin neurons in human beings. Lancet. 1998;352:1433–1437. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MECHAN A.O., ESTEBAN B., O'SHEA E., ELLIOTT J.M., COLADO M.I., GREEN A.R. The pharmacology of the acute hyperthermic response that follows administration of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy') to rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:170–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'CALLAGHAN J.P., MILLER D.B. Neurotoxicity profiles of substituted amphetamines in the C57BL/6J mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'SHEA E., EASTON N., FRY J.R., GREEN A.R., MARSDEN C.A. Protection against 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration produced by glutathione depletion in rats is mediated by attenuation of hyperthermia. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:686–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'SHEA E., ESTEBAN B., CAMARERO J., GREEN A.R., COLADO M.I. Effect of GBR 12909 and fluoxetine on the acute and long term changes induced by MDMA (‘ecstasy') on the 5-HT and dopamine concentrations in mouse brain. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORIO L., O'SHEA E., SANCHEZ V., PRADILLO J.M., ESCOBEDO I., CAMARERO J., MORO M.A., GREEN A.R., COLADO M.I. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine increases interleukin-1beta levels and activates microglia in rat brain: studies on the relationship with acute hyperthermia and 5-HT depletion. J. Neurochem. 2004;89:1445–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIZARRO N., DE LA TORRE R., FARRE M., SEGURA J., LLEBARIA A., JOGLAR J. Synthesis and capillary electrophoretic analysis of enantiomerically enriched reference standards of MDMA and its main metabolites. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002a;10:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIZARRO N., ORTUNO J., FARRE M., HERNANDEZ-LOPEZ C., PUJADAS M., LLEBARIA A., JOGLAR J., ROSET P.N., MAS M., SEGURA J., CAMI J., DE LA TORRE R. Determination of MDMA and its metabolites in blood and urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and analysis of enantiomers by capillary electrophoresis. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2002b;26:157–165. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENEMAN L., BOOIJ J., DE BRUIN K., REITSMA J.B., DE WOLFF F.A., GUNNING W.B., DEN HEETEN G.J., VAN DEN BRINK W. Effects of dose, sex, and long-term abstention from use on toxic effects of MDMA (ecstasy) on brain serotonin neurons. Lancet. 2001;358:1864–1869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06888-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAADAT K.S., ELLIOTT J.M., COLADO M.I., GREEN A.R. Hyperthermic and neurotoxic effect of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in guinea pigs. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:452–453. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1653-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANCHEZ V., CAMARERO J., ESTEBAN B., PETER M.J., GREEN A.R., COLADO M.I. The mechanisms involved in the long-lasting neuroprotective effect of fluoxetine against MDMA (‘ecstasy')-induced degeneration of 5-HT nerve endings in rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:46–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMUED L.C. Demonstration and localization of neuronal degeneration in the rat forebrain following a single exposure to MDMA. Brain Res. 2003;974:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGURA M., ORTUNO J., FARRE M., MCLURE J.A., PUJADAS M., PIZARRO N., LLEBARIA A., JOGLAR J., ROSET P.N., SEGURA J., DE LA TORRE R. 3,4-Dihydroxymethamphetamine (HHMA). A major in vivo 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) metabolite in humans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1203–1208. doi: 10.1021/tx010051p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARKEY J., MCBEAN D.E., KELLY P.A. Alterations in hippocampal function following repeated exposure to the amphetamine derivative methylenedioxymethamphetamine (‘Ecstasy') Psychopharmacology. 1991;105:113–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02316872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEPHENSON C.P., HUNT G.E., TOPPLE A.N., MCGREGOR I.S. The distribution of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ‘Ecstasy'-induced c-fos expression in rat brain. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STONE D.M., HANSON G.R., GIBB J.W. Differences in the central serotonergic effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in mice and rats. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMASIUS R., PETERSEN K., BUCHERT R., ANDRESEN B., ZAPLETALOVA P., WARTBERG L., NEBELING B., SCHMOLDT A. Mood, cognition and serotonin transporter availability in current and former ecstasy (MDMA) users. Psychopharmacology. 2003;167:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER G.T., LENNARD M.S., ELLIS S.W., WOODS H.F., CHO A.K., LIN L.Y., HIRATSUKA A., SCHMITZ D.A., CHU T.Y. The demethylenation of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (‘ecstasy') by debrisoquine hydroxylase (CYP2D6) Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]