Abstract

Pretreatment of anaesthetized guinea-pigs with either CHF 4226.01 (8-hydroxy-5-[(1R)-1-hydroxy-2-[N-[(1R)-2-(p-methoxyphenyl)-1-methylethyl]amino]ethyl] carbostyril hydrochloride), formoterol or budesonide reduced acetaldehyde (AcCHO)-evoked responses in the lungs with a rank order of potency CHF 4226.01 (ED50 values, from 1.88 to 3.31 pmol) > formoterol (ED50 values, from 3.03 to 5.51 pmol) ≫ budesonide (ED50 values, from 335 to 458 nmol). The duration of action of CHF 4226.01 in antagonizing the airway obstruction elicited by AcCHO was also substantially longer than formoterol (area under the curve) at 10 pmol, 763±58 and 480±34, respectively; P<0.01).

Continuous infusion of a subthreshold dose of AcCHO enhanced the intratracheal pressure (ITP) increases caused by subsequent challenges with substance P (from 9.7±0.8 to 27.5±1.6 cm H2O as a peak, P<0.001). Pretreatment with either CHF 4226.01 or formoterol prevented the sensitizing effect of AcCHO on substance P responses (ED50 values, 2.85 and 6.11 pmol, respectively; P<0.01).

The ED50 value of budesonide (396 nmol) in preventing AcCHO-evoked ITP increase was reduced when this glucocorticoid was combined with 0.1 pmol CHF 4226.01 (ED50 76 nmol; P<0.001). CHF 4226.01/budesonide was two-fold more effective (P<0.01) than the formoterol/budesonide combination.

These results suggest that CHF 4226.01/budesonide, by optimizing each other's beneficial potential in the control of pulmonary changes caused by AcCHO in the guinea-pigs, may represent a new fixed combination in asthma.

Keywords: Acetaldehyde, CHF 4226.01, formoterol, budesonide, β2-agonists, airway obstruction, guinea-pigs

Introduction

Acetaldehyde (AcCHO), a rapidly generated metabolite of ethanol via alcohol dehydrogenase, has been thought to be a main factor in alcohol-induced asthma (Geppert & Boushey, 1978; Gong et al., 1981) and the mechanism involved in this event has been the subject of intensive investigation: (1) blood AcCHO and histamine concentrations increase during alcohol-induced bronchoconstriction; (2) AcCHO induces histamine release from human airway mast cells to cause bronchoconstriction (Kawano et al., 2004); (3) AcCHO-induced bronchoconstriction occurs not only in subjects with so called alcohol-induced asthma, but in virtually all asthmatic individuals (Myou et al., 1993, 1994, 1995); (4) bronchial responsiveness to AcCHO, with a significant fall in the forced expiratory volume in 1 s, can be determined in man, since the patients affected by asthma are more responsive than normal subjects (Robuschi et al., 1992).

On preclinical ground, it has been reported that intravenous injection of AcCHO to guinea-pigs evokes a dose-dependent increase in intratracheal pressure (ITP). At least two mechanisms have been identified underlying the effect of AcCHO in guinea-pigs. Firstly, the airway obstruction caused by AcCHO is likely related to an increase in plasma histamine content, suggesting that AcCHO may activate subsets of mast cells or basophils, perhaps including those in the airways and lungs (Berti et al., 1993). Secondly, AcCHO challenge has been shown to activate tachykinin-containing airway sensory nerves, leading to axon reflex-evoked responses in the airways, including neurogenic plasma extravasation (Berti et al., 1994a, 1994b). In fact, H1-histamine receptor antagonists, such as pyrilamine and nimesulide, inhibited AcCHO-induced ITP increase, whereas endopeptidase inhibitors, like captopril or thiorphan, potentiated this occurrence. The inflammatory phenomenon, which is almost completely antagonized by the neurokinin-1 tachykinin receptor antagonist, CP-96345, is now considered neurogenic in nature (Berti et al., 1994b; Barnes, 1998). On this respect, it is also interesting to underline that the activation of β2-receptor on sensory nerves modulate neuropeptide release and attenuate plasma exudation in tracheobronchial tissues (Barnes, 1998). In fact, like β2-adrenergic agonists, several other compounds such as opioids (Belvisi et al., 1988), adenosine (Kamikawa & Shimo, 1989), acting on their prejunctional specific receptors and possibly through a common inhibitory mechanism, have been described to regulate tachykinins release from sensory nerves.

All these preclinical findings prompted us to compare the activity of CHF 4226.01 (previously named TA-2005), a potent and selective β2-adrenoceptor stimulant characterized by a long duration of action (Kikkawa et al., 1991, 1998; Voss et al., 1992; Waldeck, 1996), with that of formoterol in preventing pulmonary changes evoked in guinea-pigs by AcCHO. In combined studies, the interaction of CHF 4226.01/budesonide and formoterol/budesonide in the control AcCHO activity in the lungs were also compared.

Methods

Animals

About 400 male Dunkin Hartley guinea-pigs (Charles River Italia, Calco, Lecco, Italy), weighing 360–380 g were used. The animals were housed in a conditioned environment (22±1°C, 55±5% relative humidity, 12-h light and 12-h darkness cycle) and were given free access to food and tap water. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Whole animal preparation

Guinea-pigs were anaesthetized intraperitoneally with urethane (1.2–1.5 g kg−1) and prepared for simultaneous recording of both ITP and systemic blood pressure (BP), as originally described by Konzett & Rössler (1940). Briefly, the trachea was cannulated for mechanical ventilation performed by a pump operating on a partially closed circuit (10 ml kg−1, stroke volume; 70 cycles min−1). To avoid spontaneous breathing, the animals were treated with pancuronium bromide injected via the jugular vein at a dose of 2 mg kg−1 i.v. No addition of urethane was necessary, since the depth of anaesthesia was adequate for all the length of the experiment (∼300 min). BP was monitored via the left carotid artery. All changes in ITP (cmH2O) and BP (mmHg) were measured by two pressure transducers (models HP-270 and HP-1280 respectively; Hewlett Packard, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) and the signals were displayed on a Hewlett Packard multiple channel pen recorder (model HP-7754A).

Pharmacological activity of AcCHO

In this set of experiments, guinea-pigs were prepared for ITP and BP evaluation as described above. These animals were challenged intravenously with AcCHO, diluted in normal saline, administered at the doses of 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 mg kg−1 (n=6 for each dose). Each animal received only one dose. Changes in circulating histamine and vascular permeability caused by AcCHO were also determined.

Histamine assay in the blood

In order to determine the level of circulating histamine in the anaesthetized guinea-pigs, small aliquots of blood (0.5 ml). were collected from the carotid artery before and after AcCHO administration, at the peak of airway obstruction. Thereafter, the blood was processed according to the fluorometric method described by Shore et al. (1959). Briefly, this method involves extraction of histamine into n-butanol from alkalinized perchloric acid blood extract, return of the histamine to an aqueous solution and condensation with o-phthalaldehyde to yield a product with strong and stable fluorescence which is measured in a spectrofluorometer. In our experimental conditions, the recovery of histamine exceeded 95% and basal concentrations of the autacoid found in the different experimental sets (see Table 1) were within the range reported by other authors (Anton & Sayre, 1969).

Table 1.

AcCHO induces a dose-dependent increase in ITP, Evans blue exudation in the lower trachea and blood histamine in the anaesthetized guinea-pigs

| Treatment | ITP | Evans blue exudation | Histamine |

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg kg−1 i.v.) | (cm H2O) | (ng mg−1 w.t.) | (ng ml−1 of blood) |

| Saline | 3.9±0.4 | 32.6±2.5 | 49.4±5.1 |

| AcCHO 6.25 | 6.0±0.8* | 47.6±4.9* | 89.7±9.9** |

| AcCHO 12.5 | 9.8±1.5** | 81.7±8.4*** | 124.7±16.7*** |

| AcCHO 25 | 19.3±2.4*** | 149.6±18.6*** | 177.1±19.3*** |

| AcCHO 50 | 25.9±3.2*** | 224.9±17.2*** | 292.6±23.2*** |

| AcCHO 100 | 29.2±2.8*** | 329.1±28.7*** | 428.7±36.4*** |

Data are mean values±s.e.m. of six different animals for each dose of AcCHO. The ED50 value of AcCHO-induced ITP increase was 28.2 (conf. lim. 21.9–35.5) mg kg−1 i.v. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus saline.

Vascular permeability determination

The changes in vascular permeability to serum albumin caused by the i.v. administration of AcCHO were measured in guinea-pigs prepared for ITP recording (see above) using the Evans blue technique reported by Saria et al. (1983). Briefly, the Evans blue dye (30 mg kg−1) was injected into the jugular vein 1 min before the challenge with AcCHO. The guinea-pigs were killed 14 min after AcCHO administration and a tracheal piece (30–40 mg) was immediately removed about 1 cm above the carina, dried on filter paper to remove excess fluid, and weighted. Each tissue sample was placed in 4 ml formamide and incubated for 24 h in a shaking water bath at 60°C to extract Evans blue from the tissue. The amount of Evans blue in the liquid was determined by measuring the optical density at 620 nm in a Dynatech MR5000 microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, VA, U.S.A.) according to Lei et al. (1992). Three measurements were performed on each sample, and the mean value was used for calculations. The tissue content of the dye was expressed in ng mg−1 wet weight tissue (ng mg−1 w.t.) and was calculated from a standard curve of dye concentrations (0.125–5 μg ml−1).

Experimental protocol

The effect of different concentrations of CHF 4226.01. (0.1–10 pmol), formoterol (0.3–30 pmol), budesonide (31.25–500 nmol) and saline (control) was investigated in anaesthetized guinea-pigs (n=5 for each dose) by superfusing these compounds onto the tracheal mucosa (Erjefält et al., 1985; Erjefält & Persson, 1989) for 5 min before AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.) administration. The perfusing cannula (PE-10) has been positioned caudally ∼0.5 cm further the tracheal cannula (PE-350), which was surgically sutured approximately ∼1 cm before the larynx. The guinea-pigs were inclined 45° (head up), and the exact position of the perfusing cannula was controlled at the end of some experiments in order to be sure that the testing compounds have reached distal tracheobronchial tissues. The catheter was connected to a microdialysis pump (SP-101i; 2Biological Instruments, Besozzo, Varese, Italy) for 5-min mucosal superfusion at a constant flow rate of 0.01 ml min−1 (total volume, 0.05 ml).

Other experiments were also performed in order to compare the duration of action of CHF 4226.01 (1–10 pmol) and formoterol (1–30 pmol) against AcCHO-induced bronchoconstriction (n=7 for each dose). The two β2-agonists were administered onto the trachea for 5 min before AcCHO (25 mg kg−1) injected intravenously in the guinea-pigs at 20 min interval for 240 min.

In separate experiments, in order to establish a pharmacological interaction in protecting the animals from AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.)-induced airway changes, the two β2-agonists were administered into tracheal lumen in combination with the corticosteroid for 5 min before AcCHO-challenge (n=7 for each dose). In particular, budesonide (31.25–500 nmol) was associated with two low and equiactive concentrations of CHF 4226.01 (0.1 and 0.3 pmol) or formoterol (0.3 and 1 pmol).

Substance P (SP)-hyper-responsiveness

In these experiments, and as previously described (Berti et al., 1993), SP-hyper-reactivity was induced in anesthetized guinea-pigs by 60-min intravenous infusion of AcCHO (0.5% solution; flow rate, 0.05 ml kg−1 min−1). At this concentration, AcCHO does not modify basal ITP. Single doses of SP (5 μg kg−1 i.v.) were injected every 20 min and the development of hyper-reactivity to this peptide was followed for 120 min. CHF 4226.01 (1–10 pmol) and formoterol (3–30 pmol) were given intratracheally for 5 min before AcCHO-infusion (n=6 for each dose).

Drugs

Urethane, AcCHO (purity>99.5%),. SP, formamide and Evans blue were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich S.r.l., Milan, Italy. Pancuronium bromide (Pavulon) was obtained from Organon Teknika, Rome, Italy. CHF 4226.01, formoterol fumarate and budesonide were gift from Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Parma, Italy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism®, version 3.03,. GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). All results in figures and tables are expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n=5–7 different animals for each group). Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures, Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test were used for statistical analysis as appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The area under the curve (AUC) was estimated according to the trapezoid method (Purves, 1992) and was assessed using a computerized program Microcal Origin 3.5 (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, U.S.A.).

Results

Effect of CHF 4226.01, formoterol and budesonide on AcCHO-induced changes in ITP, blood histamine and plasma extravasation

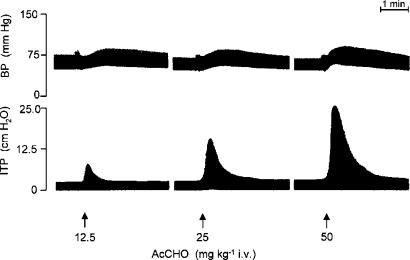

When AcCHO was injected intravenously (6.25–100 mg kg−1) in artificially ventilated anaesthetized guinea-pigs, an increase of both ITP and BP was recorded. The range of the doses used in our experiments represent a complete dose–response curve and the dose of 100 mg/kg−1 i.v. AcCHO was almost the maximal response obtainable. The airway obstruction, as well BP elevation, induced by AcCHO was proportional to the dose administered and distinguished by a rapid onset and decline (Figure 1). These events were also paralleled by a dose-dependent increase of blood histamine and Evans blue extravasation in the tracheal tissue, indicating alteration of vascular permeability (Table 1). We selected the dose of 25 mg/kg−1 i.v. AcCHO since it was very close to the ED50 value (28.2 mg/kg−1 i.v.) (Table 1). At 25 mg/kg−1 i.v. AcCHO, no tachyphylaxis was observed when this dose was given repeatedly at 20-min interval up to 240 min (data not shown). On that account, this selected dose was used in order to evaluate the protecting activity of CHF 4226.01 (0.1–10 pmol), formoterol (0.3–30 pmol) or budesonide (31.25–500 nmol), administered via intratracheal superfusion alone or in combination.

Figure 1.

Representative traces showing the effect of AcCHO on BP and ITP in three different anaesthetized guinea pigs.

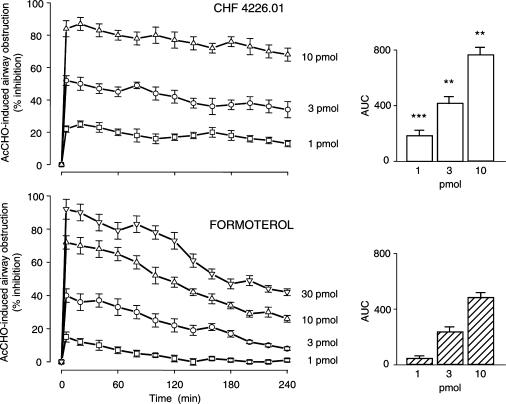

CHF 4226.01, formoterol or budesonide, instilled into the trachea at various concentrations, prevented, in a dose-related manner, the changes in ITP, blood histamine levels and Evans blue extravasation induced by AcCHO and the ED50 values obtained with the three compounds are reported in Table 2. CHF 4226.01 resulted more potent than both formoterol and budesonide in preventing AcCHO-induced ITP increase, being the dose ratio 1.8 (P<0.01) and 151720 (P<0.001), respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, when the duration of action of CHF 4226.01 against airway obstruction induced by AcCHO was compared with that of formoterol, CHF 4226.01 displayed a longer duration of action at all doses selected (Figure 2). For example, when the two β2-adrenoceptor agonists are compared at almost equieffective doses as a peak (10 and 30 pmol), the effect of CHF 4226.01 against the ITP increase was still fully present after 240 min, whereas the effect of formoterol declined approximately by 50% (Figure 2).

Table 2.

ED50 (conf. lim.=95%) and dose ratio (DR) values of CHF 4226.01, formoterol and budesonide against changes in ITP, Evans blue exudation in the lower trachea and blood histamine release induced by AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.) in the anaesthetized guinea-pigs

| Treatment | ITP | Evans blue exudation | Histamine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED50 | DR | ED50 | DR | ED50 | DR | |

| CHF 4226.01 | 2.61 (2.35–3.14) pmol | 1 | 1.88 (1.55–2.43) pmol | 1 | 3.31 (2.56–4.55) pmol | 1 |

| Formoterol | 4.69 (4.14–5.11) pmol** | 1.8 | 3.03 (2.66–3.48) pmol* | 1.6 | 5.51 (5.12–5.90)* pmol | 1.7 |

| Budesonide | 396 (351–440) nmol*** | 151,720 | 335 (278–397) nmol*** | 178,190 | 458 (392–504) nmol | 138,370 |

The ED50 values were calculated from the data obtained with five different animals for each dose of CHF 4226.01 (0.1–10 pmol), formoterol (0.3–30 pmol) or budesonide (31.2–500 nmol). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ****P<0.001 versus CHF 4226.01.

Figure 2.

CHF 4226.01 displays a longer duration of action than formoterol in antagonizing AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.)-induced airway obstruction in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. β2-Agonists were superfused onto the tracheal lumen 5 min before AcCHO challenge. This was repeated at 20-min interval for 240 min. Data are mean values±s.e.m. of seven different animals for each dose of CHF 4226.01 or formoterol. The right panels show the AUC (in abscissa, % inhibition; in ordinate, 240 min) for all concentrations of each drug used. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus the corresponding dose of formoterol.

Combination studies

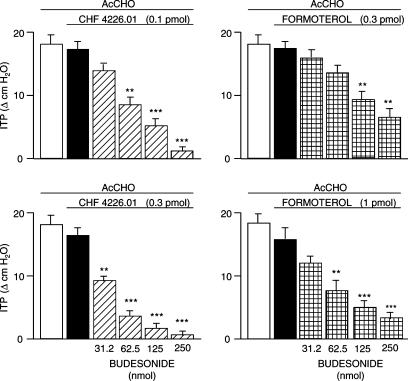

In this set of experiments, budesonide was given to the animals at various concentrations (31.25–250 nmol). in combination with low and equiactive concentrations of CHF 4226.01 (0.1 and 0.3 pmol) or formoterol (0.3 and 1 pmol) in order to assess the pharmacological interaction between the corticosteroid and the two β2-adrenergic receptor agonists in antagonizing the effect induced by AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.). Figure 3, which depicts the results obtained, clearly indicates that the interaction of budesonide with CHF 4226.01 is more potent than that obtained with formoterol. In fact, the ED50 value of budesonide given alone (396 nmol) for antagonizing AcCHO-induced airway obstruction is reduced 5.3-fold (P<0.001) and 14.3-fold (P<0.001) when the corticosteroid is given in the presence of 0.1 and 0.3 pmol of CHF 4226.01, respectively. The ED50 of budesonide was reduced 3.0-fold (P<0.01) and 5.9-fold (P<0.001) when it was associated with 0.3 and 1 pmol of formoterol, respectively. In Table 3, all these data are summarised including the values of blood histamine release and Evans blue extravasation.

Figure 3.

Protecting effect of CHF 4226.01 or formoterol in combination with graded concentrations of budesonide against changes in ITP induced by AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.) in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. CHF 4226.01/budesonide or CHF formoterol/budesonide fixed combinations were superfused onto the tracheal lumen 5 min before AcCHO. Columns represent mean values±s.e.m. of seven different animals per group. Black columns indicate the activity of the β2-agonists in the absence of budesonide (control). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus the corresponding control.

Table 3.

ED50 (conf. lim.= 95%) and dose ratio (DR) values of budesonide (BUDES; 31.2–500 nmol) alone and in combination with CHF 4226.01 or formoterol (FORM) against changes in ITP, Evans blue exudation in the lower trachea and blood histamine release induced by AcCHO (25 mg kg−1 i.v.) in the anaesthetized guinea-pigs

| Treatment | ITP | Evans blue exudation | Histamine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED50 in nmol | DR | ED50 in nmol | DR | ED50 in nmol | DR | |

| BUDES | 396 (351–440) | 1 | 335 (278–397) | 1 | 458 (392–504) | 1 |

| CHF 4226.01 (0.1 pmol)+BUDES | 76 (58–97)*** | 0.19 | 70 (45–93)*** | 0.21 | 105 (82–126)*** | 0.23 |

| CHF 4226.01 (0.3 pmol)+BUDES | 29 (21–35)*** | 0.07 | 35 (26–48)*** | 0.10 | 50 (39–61)*** | 0.11 |

| FORM (0.3 pmol)+BUDES | 132 (115–154)** | 0.33 | 101 (82–115)** | 0.30 | 161 (145–173)** | 0.35 |

| FORM (1 pmol)+BUDES | 67 (52–84)*** | 0.17 | 47 (33–62)*** | 0.14 | 82 (64–95)*** | 0.18 |

The ED50 values were calculated from the data obtained with seven different animals per group. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus BUDES alone.

SP-hyper-responsiveness

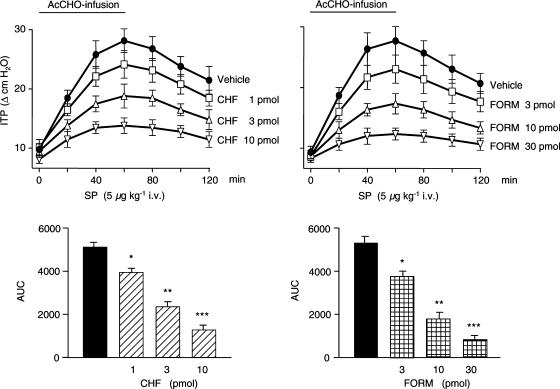

It is already known that an infusion with AcCHO at concentrations that are lower than those required for ITP increase can potentiate the effect of SP on guinea-pigs respiratory smooth muscles (Berti et al., 1993). As reported in Figure 4, the bronchoconstrictive effect of SP (5 μg kg−1 i.v.) increases with time, being 2.8-fold more potent (27.5±1.6 cm H2O, P<0.001) compared to control responses (9.7±0.8 cm H2O) at the end of 60-min AcCHO infusion. The increased responsiveness of airway smooth muscles to SP is a phenomenon declining slowly with time and 60 min after stopping the infusion with AcCHO, the effect of SP was still significantly increased (22.3±2.1 cmH2O, P<0.01).

Figure 4.

CHF 4226.01 (CHF) and formoterol (FORM) reduce in a dose-dependent manner the airway hyper-responsiveness to SP (5 μg kg−1 i.v.) induced by 60-min intravenous infusion of AcCHO (0.5% solution; flow rate, 0.05 ml kg−1 min−1) in anesthetized guinea-pigs. The lower panels show the AUC (in abscissa, cm H2O; in ordinate, 120 min) for all concentrations of each drug used. Points or columns represent mean values±s.e.m. of six different animals for each dose of CHF or FORM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus the corresponding control (vehicle) group (black column).

When CHF 4226.01 (1, 3 or 10 pmol) or formoterol (3, 10 or 30 pmol) was instilled onto the trachea 5 min before starting AcCHO infusion, the effect of SP was decreased according to the dose of the two β2-selective agonists administered. The kinetic profile of this inhibitory activity of CHF 4226.01 and formoterol is reported in Figure 4. When the data were expressed as AUC, it has been possible to calculate the ED50 for the inhibitory activity of the two compounds. CHF 4226.01 (ED50=2.85 pmol) resulted 2.1-fold more potent (P<0.01) than formoterol (ED50=6.11 pmol) in curtailing the hyper-responsiveness of SP (Figure 4). Furthermore, both CHF 4226.01 and formoterol were almost ineffective in antagonizing the airway obstruction induced by SP (5 μg kg−1 i.v.) in the absence of AcCHO infusion (data not shown).

Discussion

The results obtained in the present study in guinea-pigs clearly indicate that the tracheal instillation of long-acting β2-selective agonists CHF 4226.01 and formoterol in combination with budesonide bring about a synergic interaction in antagonizing the airway effects of AcCHO, which recognize some of the pathophysiological features of asthma.

The challenge with AcCHO has been selected for the peculiarity of its mode of action, since the airway obstruction caused by this compound is mostly mediated by histamine release and accompanied by plasma extravasation in tracheal tissues. The latter event has been shown to involve SP and other neuropeptides released from sensory nerve endings on airways (neurogenic inflammation) (Berti et al., 1993, 1994b). All the effects of AcCHO in guinea-pigs are potently antagonized by CHF 4226.01 and formoterol when given by caudal tracheal superfusion. CHF 4226.01 was almost two-fold as potent as formoterol not only in preventing ITP increase but also in reducing the release of histamine and plasma extravasation. Also, the duration of the inhibitory effect of CHF 4226.01, particularly against AcCHO-induced airway obstruction, resulted significantly superior to that of formoterol. In fact, at variance with the latter, the former compound was still fully active after 240 min. These findings are in good agreement with those reported by Kikkawa et al. (1994) in histamine-, serotonin- or antigen-induced bronchoconstriction in guinea-pigs and cats. They may be explained by the ability of CHF 4226.01 to tightly bind to the β2-receptor with subsequent sustained activation (Voss et al., 1992). The singular interaction of the compound with the tyrosine 308 residue in the seventh transmembrane region of the β2-receptor might play a role as well (Kikkawa et al., 1998). The corticosteroid budesonide was also able to lessen the effect of AcCHO in the guinea-pigs airways, but as expected, its efficacy was in the nmol range and notably inferior to that observed for both CHF 4226.01 and formoterol.

The ability of the two β2-selective agonists to antagonize the injurious effects of AcCHO in guinea-pigs airways is likely to follow the pathway of adenylate cyclase-activation with substantial accumulation of intracellular cAMP (Weston & Peachell, 1998) and stabilization of various subset of mast cells to reduce histamine release and to elicit bronchodilatation. The observed inhibition of plasma extravasation in the tracheobronchial tissues can be also explained by the well-known ability of β2-agonists to prevent separation of endothelial cells in postcapillary venules (Erjefält & Persson, 1991; Bolton et al., 1997) and by the activation of prejunctional β-receptors on sensory nerves with consequent reduction in sensory neuropeptide release (Barnes, 1998). This last hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that both CHF 4226.01 and formoterol do not directly affect the SP-induced ITP increase.

Another interesting result emerging from these studies is the hyper-responsiveness of guinea-pigs airways to SP induced by low dosage of AcCHO infusion. This event, which is reversible on stopping AcCHO administration, has been already characterized on pharmacological ground, but the mechanism/s involved has not been fully elucidated. The increased response of airway smooth muscles appears to be specific to SP, since the infusion with AcCHO does not increment either acetylcholine or histamine activity (Berti et al., 1993). In this respect, the results obtained indicate that CHF 4226.01 is about two-fold as potent as formoterol. The relevance of these findings is difficult to discuss in a proper framework. Physiopathological studies are still needed to better define the role of tachykinins from sensory nerves and their relationship with proinflammatory cells (neutrophils, eosinophils) in the airway. Recently, it has been reported that AcCHO induces granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in human bronchi through activation of nuclear factor-κB (Machida et al., 2003). The ability of AcCHO to generate GM-CSF could be an alternative explanation that may be relevant for the present findings. Study with GM-CSF have already demonstrated that in addition to being chemoattractant for eosinophils and neutrophils, this cytokine also potentiates the differentiation and survival of this proinflammatory cells (Owen et al., 1987). Formoterol and salmeterol, another long-acting β2-agonist, have been reported to reduce GM-CSF levels in tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated human bronchial epithelial cells (Korn et al., 2001) and in antigen-activated human blood mononuclear cells (Oddera et al., 1998), respectively. No data are available about the effects of CHF 4226.01 on GM-CSF production, but in human macrophage cell line it has been shown to suppress the lipopolysaccharide-induced release of tumor necrosis factor-α through a β2-receptor-mediated mechanism (Izeboud et al., 2000), confirming the findings of Bissonnette & Befus (1997) with salmeterol and salbutamol.

Even if the anti-inflammatory properties of long-acting β2-agonists are still a matter of debate, it is well accepted that these drugs exert additive effects on the anti-inflammatory activity of glucocorticoids. In this context, there are several studies demonstrating a positive interaction between these two classes of drugs (Greening et al., 1994; Chong et al., 1997; McGavin et al., 2001; Barnes, 2002). Corticosteroids increase the expression of β2-receptors by increasing gene transcription and this will protect against the loss of β2-receptors in response to long-term exposure to β2-agonists. On the other end, β2-agonists may potentiate the molecular mechanism of corticosteroid action with increased nuclear localization of glucocorticoid receptors and additive, sometimes synergistic, suppression of inflammatory mediator release (Chong et al., 1997; Johnson, 2002; Roth et al., 2002). On this regard, the tracheal superfusion of CHF 4226.01 in combination with budesonide gives rise to a synergistic interaction in the control of AcCHO-induced responses in guinea-pig airway. In fact, considering the increase in ITP caused by AcCHO, the ED50 value (396 nmol) obtained with budesonide alone was diminished 5.3-fold (P<0.001) and 14.3-fold (P<0.001) when it was combined with 0.1 and 0.3 pmol of CHF 4226.01, respectively. The formoterol/budesonide combination was less effective than that observed with CHF 4226.01/budesonide in preventing AcCHO-evoked responses. The more advantageous pharmacological interaction observed with CHF 4226.01/budesonide combination is not easy to explain, since the present experimental conditions deal with only a single treatment of the drugs in combination. It is likely that the potency of the β2-agonists in activating selectively the β2-receptors may have played an important role.

In conclusion, the results obtained with the present experiments indicate that CHF 4226.01 is more potent and long-lasting than formoterol in protecting guinea-pig airways from the AcCHO effects, which are primarily mediated by histamine release with a contribution of activated sensory nerve endings. Thus, CHF 4226.01 and budesonide, which may optimize each other's beneficial potential in the airway, may represent a new fixed combination of clinical interest in the control of asthma in most patients.

Abbreviations

- AcCHO

acetaldehyde

- AUC

area under the curve

- BP

blood pressure

- CHF 4226.01

(8-hydroxy-5-[(1R)-1-hydroxy-2-[N-[(1R)-2-(p-methoxyphenyl)-1-methylethyl]amino]ethyl] carbostyril hydrochloride)

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- ITP

intratracheal pressure

- SP

substance P

References

- ANTON A.H., SAYRE D.F. A modified fluorometric procedure for tissue histamine and its distribution in various animals. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1969;166:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J.NANC nerves and neuropeptides Asthma: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Management 1998London: Academic Press; 423–457.eds. Barnes, P.J., Rodger, I.W. & Thomson N.C. pp. [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Scientific rationale for inhaled combination therapy with long-acting β2-agonists and corticosteroids. Eur. Respir. J. 2002;19:182–191. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00283202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELVISI M.G., CHUNG K.F., JACKSON D.M., BARNES P.J. Opioid modulation of non-cholinergic neural bronchoconstriction in guinea-pig in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;95:413–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTI F., ROSSONI G., BUSCHI A., ROBUSCHI M., TRENTO F., DELLA BELLA D.Acetaldehyde induces a bronchoconstrictor response in guinea pigs New Developments in the Therapy of Allergic Disorders and Asthma. Int. Acad. Biomed. Drug Res 1993Basel: Karger; 33–43.eds. Langer, S.Z., Church, M.K., Vargaftig, B.B. & Nicosia S. pp. [Google Scholar]

- BERTI F., ROSSONI G., BUSCHI A., VILLA L.M., TRENTO F., DELLA BELLA D., BAGOLAN M. Influence of theophylline on both bronchoconstriction and plasma extravasation induced by acetaldehyde in guinea-pigs. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1994a;44:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTI F., ROSSONI G., DELLA BELLA D., TRENTO F., BERNAREGGI M., ROBUSCHI M. Influence of acetaldehyde on airway resistance and plasma exudation in the guinea-pig. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1994b;44:1342–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISSONNETTE E.Y., BEFUS A.D. Anti-inflammatory effects of β2-agonists: inhibition of TNF-α release from human mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1997;100:825–831. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOLTON P.B., LEFEVRE P., MCDONALD D.M. Salmeterol reduces early-and late-phase plasma leakage and leukocyte adhesion in rat airways. Am J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1997;155:1428–1435. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHONG L.K., DRURY D.E., DUMMER J.F., GHAHRAMANI P., SCHLEIMER R.P., PEACHELL P.T. Protection by dexamethasone of the functional desensitization to β2-adrenoceptor-mediated responses in human lung mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:717–722. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERJEFÄLT I.A., PERSSON C.G. Inflammatory passage of plasma macromolecules into airway wall and lumen. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1989;2:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(89)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERJEFÄLT I.A., PERSSON C.G. Long duration and high potency of antiexudative effects of formoterol in guinea-pig tracheobronchial airways. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1991;144:788–791. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERJEFÄLT I.A., WAGNER Z.G., STRAND S.E., PERSSON C.G. A method for studies of tracheobronchial microvascular permeability to macromolecules. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1985;14:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEPPERT E.F., BOUSHEY H.A. An investigation of the mechanism of ethanol-induced bronchoconstriction. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1978;118:135–139. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONG H., JR, TASHKIN D.P., CALVARESE B.M. Alcohol-induced bronchospasm in an asthmatic patient. Chest. 1981;80:167–173. doi: 10.1378/chest.80.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENING A.P., IND P.W., NORTHFIELD M., SHAW G. Added salmeterol versus higher-dose corticosteroid in asthma patients with symptoms on existing inhaled corticosteroid. Lancet. 1994;344:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZEBOUD C.A., VERMEULEN R.M., ZWART A., VOSS H.P., VAN MIERT A.S., WITKAMP R.F. Stereoselectivity at the β2-adrenoceptor on macrophages is a major determinant of the anti-inflammatory effects of β2-agonists. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:184–189. doi: 10.1007/s002100000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON M. Combination therapy for asthma: complementary effects of long-acting β2-agonists and corticosteroids. Curr. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002;15:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- KAMIKAWA Y., SHIMO Y. Adenosine selectively inhibits noncholinergic transmission in guinea pig bronchi. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;66:2084–2091. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWANO T., MATSUSE H., KONDO Y., MACHIDA I., SAEKI S., TOMARI S., MITSUTA K., OBASE Y., FUKUSHIMA C., SHIMODA T., KOHNO S. Acetaldehyde induces histamine release from human airway mast cells to cause bronchoconstriction. Int. Arch. Allergy. Immunol. 2004;134:233–239. doi: 10.1159/000078771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIKKAWA H., ISOGAYA M., NAGAO T., KUROSE H. The role of the seventh transmembrane region in high affinity binding of a β2-selective agonist TA-2005. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:128–134. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIKKAWA H., KANNO K., IKEZAWA K. TA-2005, a novel, long-acting, and selective β2-adrenoceptor agonist: characterization of its in vivo bronchodilating action in guinea pigs and cats in comparison with other β2-agonists Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1994;17:1047–1052. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIKKAWA H., NAITO K., IKEZAWA K. Tracheal relaxing effects and β2-selectivity of TA-2005, a newly developed bronchodilating agent, in isolated guinea pig tissues. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1991;57:175–185. doi: 10.1254/jjp.57.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONZETT H., RÖSSLER R. Versuchsanordnung zu untersuchunger an der bronchialmuskulatur. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1940;195:556–567. [Google Scholar]

- KORN S.H., JERRE A., BRATTSAND R. Effects of formoterol and budesonide on GM-CSF and IL-8 secretion by triggered human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 2001;17:1070–1077. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00073301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEI Y.H., BARNES P.J., ROGERS D.F. Inhibition of neurogenic plasma exudation in guinea-pig airways by CP-96,345, a new non-peptide NK1 receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:261–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACHIDA I., MATSURE H., KONDO Y., KAWANO T., SACKI S., TOMARI S., FUKUSHIMA C., SHIMODA T., KOHNO S. Acetaldehyde induces granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor production in human bronchi through activation of nuclear factor-kappa B. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGAVIN J.K., GOA K.L., JARVIS B. Inhaled budesonide/formoterol combination. Drugs. 2001;61:71–78. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYOU S., FUJIMURA M., BANDO T., SAITO M., MATSUDA T. Aerosolized acetaldehyde, but not ethanol, induces histamine-mediated bronchoconstriction in guinea-pigs. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1994;2:140–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1994.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYOU S., FUJIMURA M., KAMIO Y., BANDO T., NAKATSUMI Y., MATSUDA T. Repeated inhalation challenge with exogenous and endogenous histamine released by acetaldehyde inhalation in asthmatic patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:456–460. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7543344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYOU S., FUJIMURA M., NISHI K., OHKA T., MATSUDA T. Aerosolized acetaldehyde induces histamine-mediated bronchoconstriction in asthmatics. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;148:940–943. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ODDERA S., SIVESTRI M., TESTI R., ROSSI G.A. Salmeterol enhances the inhibitory activity of dexamethasone on allergen-induced blood mononuclear cell activation. Respiration. 1998;65:199–204. doi: 10.1159/000029260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWEN W.F., JR, ROTHENBERG M.E., SILBERSTEIN D.S., GASSON J.C., STEVENS R.L., AUSTEN K.F., SOBERMAN R.J. Regulation of human eosinophil viability, density, and function by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the presence of 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Exp. Med. 1987;166:129–141. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PURVES R. Optimum numerical integration methods for estimation of area-under-the-curve (AUC) and area-under-the-moment-curve (AUMC) J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1992;20:211–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01062525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBUSCHI M., SCURI M., GAMBARO G., SPAGNOTTO V., FAY V., FICHERA E., VAGHI A., ROSSONI G., BERTI F., BIANCO S. Acetaldehyde challenge test. Eur. Resp. J. 1992;5:511s. [Google Scholar]

- ROTH M., JOHNSON P.R., RUDIGER J.J., KING G.G., GE Q., BURGESS J.K., ANDERSON G., TAMM M., BLACK J.L. Interaction between glucocorticoids and β2 agonists on bronchial airway smooth muscle cells through synchronised cellular signalling. Lancet. 2002;360:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARIA A., LUNDBERG J.M., SKOFITSCH G., LEMBECK F. Vascular protein linkage in various tissue induced by substance P, capsaicin, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine and by antigen challenge. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1983;324:212–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00503897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE P.A., BURKHALTER A., COHN V.H., JR A method for the fluorometric assay of histamine in tissues. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1959;127:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOSS H.P., DONNELL D., BAST A. Atypical molecular pharmacology of a new long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist, TA-2005. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;227:403–409. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90158-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDECK B. Some pharmacodynamic aspects on long-acting β-adrenoceptor agonists. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:575–580. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESTON M.C., PEACHELL P.T. Regulation of human mast cell and basophil by cAMP. Gen. Pharmacol. 1998;31:715–719. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]