Abstract

T-cell proliferation is critical for mounting an effective adaptive immune response. It is regulated by signals through the T-cell receptor, through co-stimulation and through cytokines such as interleukin-2 (IL-2). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) lies downstream of each of these pathways and has been directly implicated in the regulation of lymphocyte proliferation.

In this study, we have shown that PI3K regulates cyclin D2 and cyclin D3, the first cell cycle proteins induced in T-cell proliferation, transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally. In T-lymphoblasts, LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor, prevents the induction of both D-type cyclin mRNA and protein, while rapamycin inhibits the induction of protein. Rapamycin inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which lies downstream of PI3K.

Furthermore, our data show that the combination of LY294002 and rapamycin results in a co-operative inhibition of T-cell proliferation. This co-operation occurs in Kit225 cells stimulated with IL-2, and also in resting peripheral blood lymphocytes stimulated with antibodies to the T-cell receptor in the presence and absence of antibodies to CD28.

These data indicate that PI3K regulates T-cell proliferation in response to diverse stimuli, and suggest that combinations of inhibitors, perhaps isoform-selective, may be useful as alternative immunosuppressive therapies.

Keywords: LY294002, rapamycin, cyclin D2, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), immunosuppression, T-cell proliferation, interleukin-2 (IL-2)

Introduction

T-cell proliferation is critical for mounting an effective adaptive immune response. Therapeutic strategies aimed at suppressing the immune system, in order to allow transplantation, target T-cells and prevent their proliferation (Kahan, 2003). T-cell proliferation is regulated by three types of cell surface molecules (Yusuf & Fruman, 2003). The key step is the recognition of peptide by the T-cell receptor. Co-stimulation, for example, through CD28, and cytokine stimulation are also required for maximal proliferation. The cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) can provide the signals necessary for T-cell cycle progression and differentiation. The IL-2 receptor can be targeted by blocking antibodies in order to aid in transplantation and prevent rejection of the allograft. Mutation of the common gamma chain utilized by IL-2 and other cytokines leads to immunodeficiency (Leonard, 2001). Thus, IL-2 signalling through the IL-2 receptor is an important step in mounting an effective T-cell proliferative response.

IL-2 signals through at least three cellular pathways (Nelson & Willerford, 1998). These include signals to signal transducer and activator of transcription-5 (STAT5) and STAT3, the Ras-MAP kinase pathway and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. We have previously shown that PI3K is important for IL-2-induced cell proliferation (Brennan et al., 1997; 1999). Work using pharmacological inhibitors and analysis from mice deficient in subunits of the kinase (Brennan et al., 1997; 1999; Okkenhaug et al., 2002) has contributed to the substantial body of evidence demonstrating the importance of PI-3 kinase to the regulation of T-cell proliferation. PI3K also lies downstream of the T-cell receptor and the co-stimulatory molecule CD28 (Ward & Cantrell, 2001). Thus, links between PI3K and the cell cycle are likely to be critical for T-cell proliferation.

IL-2 induces the progression of T-cells through G1 to S phase of the cell cycle (Nelson & Willerford, 1998). This cell cycle progression is mediated through an increase in D-type cyclins. The cyclins are a group of proteins made and destroyed in a cyclical manner in the cell. When present at sufficient levels, the D-type cyclins activate cyclin-dependent kinases (cdk) 4 and 6. Cdk4 and cdk6 activity is critical to G1- to S-phase progress. The key substrates of cdk4 and cdk6 are members of the pocket protein family, typified by the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product, pRb. The phosphorylation of pRb results in an increase in E2F transcriptional activity, which is required for the induction of genes involved in DNA synthesis (Sherr, 1996). Cdk4 and cdk6 activity can also be modulated by the levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, particularly p27kip1. Both cyclin D3 and p27kip 1 have been shown to be regulated by PI3K in T-cells (Brennan et al., 1997). There have been a range of studies focused on p27kip1, but there are little data about how PI3K regulates the D-type cyclins in T-cells.

Two pharmacological agents are available to study PI3K and downstream pathways. The first is a widely used inhibitor, LY294002. This is a competitive ATP inhibitor of PI3K that is stable in aqueous solution (Vlahos et al., 1994). Rapamycin, an immunosuppressant, inhibits a subset of PI3K pathways by inhibiting the molecule mTOR (Abraham & Wiederrecht, 1996). This study was performed to investigate the pathway leading from PI3K to the D-type cyclins and utilized both of these pharmacological inhibitors. We have shown that LY294002 inhibits cyclin D2 and cyclin D3 transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally, while rapamycin regulates cyclins on a post-transcriptional level. The different effects of the inhibitors prompted us to investigate the effect of a combination of the agents. Combining LY294002 and rapamycin resulted in significantly more inhibition of T-cell proliferation at doses that had little effect alone. They inhibited T-cell proliferation in response to IL-2, in response to activation of CD3, a component of the T-cell receptor, and in response to activation of CD3 in the presence of an antibody to CD28. This work suggests that inhibition of T-cell proliferation using a combination of a PI3K inhibitor, perhaps an isoform-selective one, and rapamycin could be beneficial as an alternative immunosuppressive regime.

Methods

Cell culture

Kit225 cells are an IL-2-dependent T-cell line derived from a patient with T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (Hori et al., 1987). The cell line was cultured in RPMI media supplemented with 20 ng ml−1 IL-2 (Chiron, U.K.), 10% foetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, antibiotics (200 U ml−1 penicillin and 200 μg ml−1 streptomycin), and was maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator. In the absence of IL-2, these cells accumulate in G1 phase of the cell cycle. The cells were deprived of IL-2 for 72 h prior to use in experiments by washing the cells twice in RPMI 1640 media, before resuspending in RPMI 1640 without IL-2. IL-2 receptor-expressing human peripheral blood-derived T-lymphoblasts were generated and maintained as described previously (Beadling et al., 1994). The cells were quiesced by washing three times in RPMI 1640, and replaced in RPMI 1640 with 10% serum in the absence of IL-2 for 48–72 h.

Total lysate preparation, Western blotting and antibody detection

Cell samples were lysed in 2 × gel sample buffer (0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 6.8, 0.2 M dithiothreitol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 20% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue). DNA was sheared by sonication and the samples were boiled for 5 min. The solubilized proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and transferred to PVDF membranes for immunoblotting using an alkaline phosphatase chemiluminescent detection protocol (Mehl et al., 2001). Typically, the lysates from 4 × 105 cells were applied to each track of the gel. The cyclin E antibody (Cat. no. 554182) was from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Antibodies to cyclin D2 (M-20) (Cat. no. sc-593), cyclin D3 (C-16) (Cat. no. sc-182) and p27 kip1(Cat. no. sc-1641) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.) and were used at a concentration of 200 ng ml−1. Antibodies to phospho S6 (Ser 235/236) (Cat no. 2211), pan S6 (Cat no. 9611), phospho pRb amino acids (Ser 795) (Cat no. 9301) were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) and were used at a 1/1000 dilution of the stock supplied. The antibody to pan pRb (Cat no. 554136) was from BD Transduction Laboratories and was used at a 1/1000 dilution. The antibody to actin (Cat. no. A-2066) was from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, U.K.) and was used at a 1/1000 dilution of the stock supplied.

Cell counting and viability analysis

Cells were seeded at concentrations of 2.5 × 105 cells ml−1 in a 24-well plate. Following a 30-min incubation with the pharmacological inhibitor, and stimulation with IL-2, cells were incubated at 37°C for the course of the experiment. Aliquots of 250 μl were removed for analysis at appropriate times. A volume of 10 μl propidium iodide solution (50 μg ml−1) was added in order to determine the levels of cell death in the samples. Cells in the live gate only were counted for a defined time on the flow cytometer. The PI data to determine the percentage of cell death were analyzed in the FL-3 channel, acquiring data on all cells, not just those in the live gate.

RNA extraction and RNase protection

Total RNA was extracted from human T-cells using the lithium chloride method. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in urea/lithium chloride buffer (500 mM urea, 300 mM LiCl2 with 100 U ml−1 of heparin and 10 U ml−1 of RNAsin). The cells were lysed by passing the solution through a 19 G needle 10 times. The cells were then placed on ice overnight. The solution was spun for 20 min at 4°C and the pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5% SDS. The protein was removed using phenol/chloroform. Sodium acetate was added to a final concentration of 300 mM and RNA was precipitated by the addition of 2.2 v of ethanol. The suspension was placed at −20°C for 2 h and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet of total RNA was washed with 70% ethanol and dried. The quality of the RNA was checked visually on a gel and by optical density measurements at 260 and 280 nm. The RNase protection was performed using the Multi-Probe RNase protection assays system from Pharmingen. The human cell cycle regulator multiprobe template set (hCYC-1) and T7 RNA polymerase were used to synthesize 32P-labelled antisense riboprobes, which were hybridized to the RNA sample in solution at 54°C for 16 h. After digestion of free probe and other single-stranded RNA with RNases A and T1, the labelled ‘RNase-protected' fragments were phenol : chloroform : isoamyl alcohol-extracted and ethanol-precipitated. The fragments were then resolved on 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and detected by autoradiography. Approximately 5000 c.p.m. of ‘unprotected' labelled probe served as a reference to identify the fragments.

Analysis of cell proliferation with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)

Quiesced cells were washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 1 ml PBS for each 107 cells. CFSE (Kurts et al., 1997; Oehen & Brduscha-riem, 1999) was added to give a final concentration of 2.5 μM. The cell suspension was mixed thoroughly and placed at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 ml of RPMI with 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were washed twice and resuspended in RPMI at 2 × 106 cells ml−1, in six-well plates, prior to stimulation. The fluorescence of the cells was determined by flow cytometry, acquiring data in the FL-1 channel. Cells in the viable gate were analyzed. The cell proliferation was determined by a decrease in cell fluorescence from day 0 to the final time point of day 4 in the Kit225 experiments, and day 6 in the experiments analysing primary human T-cells. CFSE profiles were analyzed using the proliferation platform of the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., CA, U.S.A.).

Analysis of cell proliferation by tritiated thymidine incorporation

Human lymphocytes were isolated from whole blood using a Ficoll gradient. The PBLs isolated were plated out (105 cells in 180 μl of complete medium) in triplicate, in a 96-well round-bottomed plate and pretreated with LY294002 and rapamycin at a range of doses alone or in combination for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3 2.5 ng ml−1, CRUK) or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody (5 μg ml−1, BD Biosciences) for 4 days and pulsed with tritiated thymidine (0.5 μCi per well; Amersham Life Sciences, U.K.) for the last 16 h of the experiment; incorporation of 3[H]thymidine was assessed by liquid scintillation counting.

Results

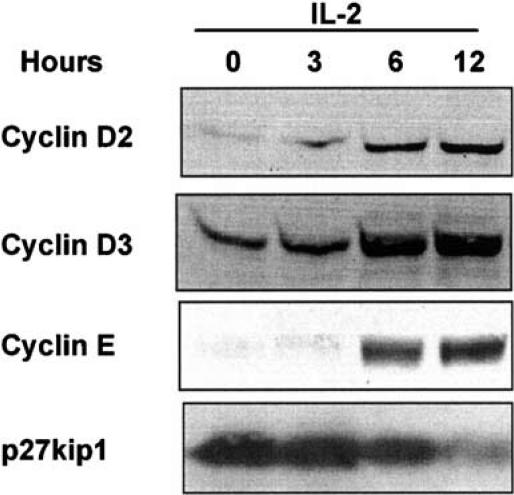

Kinetics of changes of D-type cyclins in response to IL-2 in human peripheral T-cells

As our first step, we characterized the induction of D-type cyclins in response to IL-2 in human peripheral T-cells in order to examine the kinetics of the changes in the cell-cycle proteins. Lymphocytes were isolated from whole blood using a Ficoll gradient and T-lymphoblasts were prepared by activating with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) and IL-2 for 4 days and then stimulating in IL-2 for a further 2 days. These cells were then removed from IL-2 for 2 days prior to beginning the experiment to allow them to accumulate in G1 phase of the cell cycle. The cells were then stimulated by the addition of IL-2 to induce cell cycle entry. Protein extracts were generated at the defined intervals and run on a polyacrylamide gel. Changes in the levels of cell cycle proteins were investigated using specific antibodies. Figure 1 shows that both D-type cyclins are induced. Cyclin D2 is induced quickly with an increase in the corresponding protein band observed at 3 h. No change in the level of p27kip1, a cdk inhibitor, is obvious at this point, while the loss of p27kip1 parallels the induction of the D-type cyclins at later times. Cyclin E induction is a later event with the induction obvious at 6 h rather than 3. All these events happen prior to cell cycle entry, which occurs after approximately 12 h.

Figure 1.

IL-2 induces D-type cyclins in primary human T-cells. Human T-cells were activated and grown in PHA (1 μg ml−1) and IL-2 (20 ng ml−1) for 1 week. They were removed from IL-2 (20 ng ml−1) for 2 days and stimulated with IL-2 (20 ng ml−1) for the times indicated. Cells were lysed and protein extracts generated. Protein extracts were resolved by SDS–PAGE and Western blotted. Cell cycle proteins were assayed by antibody detection. Each blot is representative of five or more experiments. A typical time course of cyclin induction is illustrated.

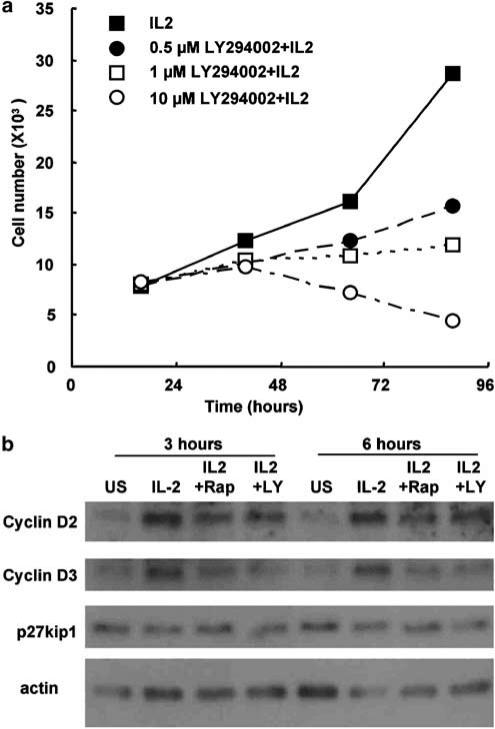

LY294002 and rapamycin inhibit proliferation and D-type cyclin induction in human T-cells

In order to explore the role of PI3K in IL-2-mediated T-cell proliferation, we used the inhibitor LY294002. Previously activated human T-lymphoblasts were incubated with three different doses of LY294002 in the presence of IL-2. Cell number and cell viability was assessed by flow cytometry. Figure 2a shows that LY294002 inhibits cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Flow-cytometric analysis demonstrated that this was not due to an increase in cell death (data not shown).

Figure 2.

LY294002 inhibits IL-2-mediated T-cell proliferation and IL-2-induced cell cycle protein changes. (a) Human T-cells were generated as described for Figure 1. They were incubated with three concentrations of LY294002 for 30 min prior to stimulation with IL-2. The concentrations of LY294002 were 0 μM (solid squares), 0.5 μM (solid circles), 1 μM (open squares) and 10 μM (open circles). After the defined times (as indicated), cells were counted by flow cytometry. Only the live cells were counted. The graph is from a single experiment and is representative of observations from more than 10 experiments. (b) Human T-cells generated as for Figure 1 were preincubated with either rapamycin (20 nM) or LY294002 (10 μM), a PI3K inhibitor, for 30 min. They were then stimulated with IL-2 (20 ng ml−1). Protein samples were taken at defined times, and the level of cell cycle proteins was determined following SDS–PAGE and Western blotting.

To elucidate the role of PI3K on cell cycle events, we treated cells with LY294002 and rapamycin, which inhibits a subset of PI3K pathways. Human T-cells were prepared as before, and pretreated with LY294002 or rapamycin before stimulation with IL-2 for the times indicated. Protein extracts were generated at the defined intervals and run on a polyacrylamide gel. Changes in the levels of cell cycle proteins were investigated using specific antibodies. Figure 2b shows the effects of pretreatment of T-cells with either LY294002 or rapamycin. Both LY294002 and rapamycin inhibited the induction of cyclin D2 and D3.

Regulation of cyclin RNA by IL-2

Changes in protein levels observed in the cell can be a result of altering transcription or translation. In order to determine if LY294002 or rapamycin could alter cyclin RNA levels, we performed an RNase protection assay with probes for cyclin D2. Total RNA extracts were generated from human T-cells, treated as before. Figure 3 shows a graph of normalized data from three different experiments. The RNA levels were normalized to housekeeping genes GAPDH and L32. LY294002 (10 μM) caused a 50% decrease in cyclin D2 mRNA, while the effect of rapamycin was not significant. This study showed that that LY294002 inhibited the induction of cyclin D2 and D3 (not shown) mRNA by IL-2. Other studies from our laboratory indicate that PI3K can directly transactivate both D-type cyclin promoters (data not shown). Rapamycin did not substantially affect the levels of D-type cyclin mRNA. This indicates that LY294002 regulated cyclin D2 transcription but rapamycin only affected cyclin D2 post-transcriptionally.

Figure 3.

Regulation of cyclin RNA by IL-2. Human T-cell samples generated in parallel with those in Figure 1 were treated with LY294002 and rapamycin (20 nM) for 30 min and stimulated with IL-2 for 3 h. Total RNA was extracted from the cells and the presence of cyclin mRNA levels was determined by RNase protection. The levels were quantified and normalized to the housekeeping gene L32 and expressed as percentage signal seen in cells treated with IL-2 alone. This graph represents cyclin data accumulated from three experiments. Student's t-test was used to ascertain the statistical significance of the results. The effects of the LY294002 on cyclin D2 RNA expression were significant (P<0.05). The effects of rapamycin were not significant.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin inhibit proliferation of the Kit225 T-cell line

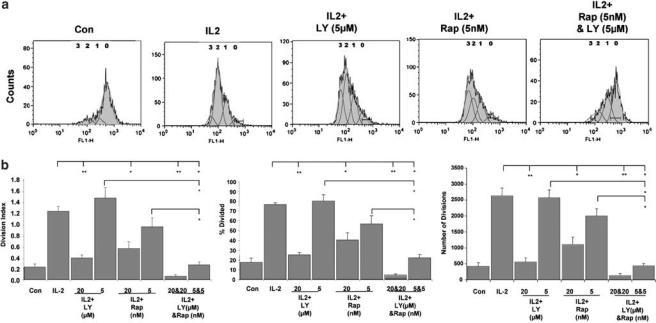

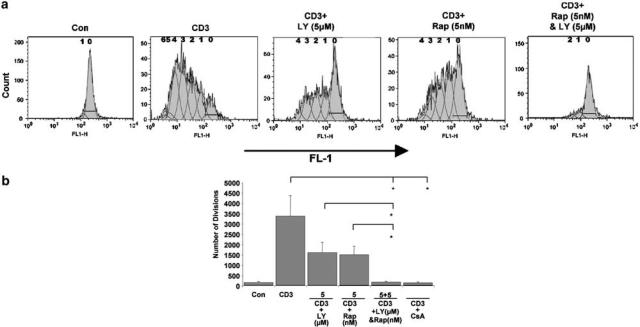

The effects of LY294002 and rapamycin on cyclin D2, coupled with the information regarding the regulation of p27kip1 (Medema et al., 2000; Kops et al., 2002; Stahl et al., 2002), prompted us to investigate the effect of combinations of the two agents on T-cell proliferation. We hypothesized that the effects of these two inhibitors may co-operate to cause enhanced inhibition of proliferation. This hypothesis was first investigated using quiesced Kit225 cells, an IL-2-dependent leukemic T-cell line (Brennan et al., 1997; 1999). They accumulate in G1 phase of the cell cycle following the removal of IL-2. The Kit225 cells were stained with the protein dye CFSE, which allows the analysis of cell division by flow cytometry (Kurts et al., 1997; Oehen & Brduscha-riem, 1999). Cell proliferation was determined within the live gate only, excluding an effect on cell survival. Figure 4a shows a typical flow cytometry profile from this experiment. The numbers on the histograms denote the proposed number of population divisions the cells have undergone. Stimulation of Kit225 cells with IL-2 caused proliferation and a decrease in fluorescence, illustrated by a shift to the left on the histogram.

Figure 4.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to inhibit IL-2-induced proliferation. Quiesced Kit225 cells were stained with a cell protein dye, CFSE. They were then treated with LY294002 or rapamycin at the concentrations shown and stimulated as indicated. (a) Representative flow cytometry histograms, measured after 4 days, are illustrated. The numbers on the histograms denote the proposed number of population divisions the cells have undergone. (b) The curves generated by the CFSE profile were analysed using the proliferation platform of the FlowJo software. The three measurements calculated (Division Index, % Divided and Number of Divisions) are indicated as histograms. The graphs were generated from three different experiments. The numbers under the axis represent inhibitor concentrations. The error bars represent the standard error from three experiments. Student's t-tests were used to ascertain if the results were significant, with * indicating a significance level of P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01.

The curves generated by the CFSE profile were analysed using the proliferation platform of the FlowJo software. This analysis allocates cells to populations that have divided, based on a best-fit root mean square function. FlowJo also returns various values that provide a measure of proliferation. Two of these measurements are Division Index and % Divided. Division Index is the average number of divisions that a cell (that was present in the starting population) has undergone. % Divided is the percentage of cells of the original sample, which divided (assuming that no cells died during the culture). The allocation of cells to populations also allows a calculation of the number of cell divisions. Each cell in population 1 has divided once, while each cell in population 2 has divided twice, and so on. We have calculated these three measurements for Kit225 cells treated with LY294002 and rapamycin to allow the best quantitation of the effects of these inhibitors on the CFSE profiles. Each of these is indicated as histograms (Figure 4b). All of the measurements show similar patterns. Paired T-tests were performed to determine if the samples are significantly different from those that have been treated with IL-2 alone, with P<0.05 indicated by * and P<0.01 indicated by **.

All the three histograms show that 20 μM LY294002 and 20 nM rapamycin significantly inhibit Kit225 cell proliferation. The lower doses, 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin, did not significantly affect cell division. However, the combination of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin together caused a significant inhibition of cell division, as indicated by all three of the measurements generated from the CFSE profiles.

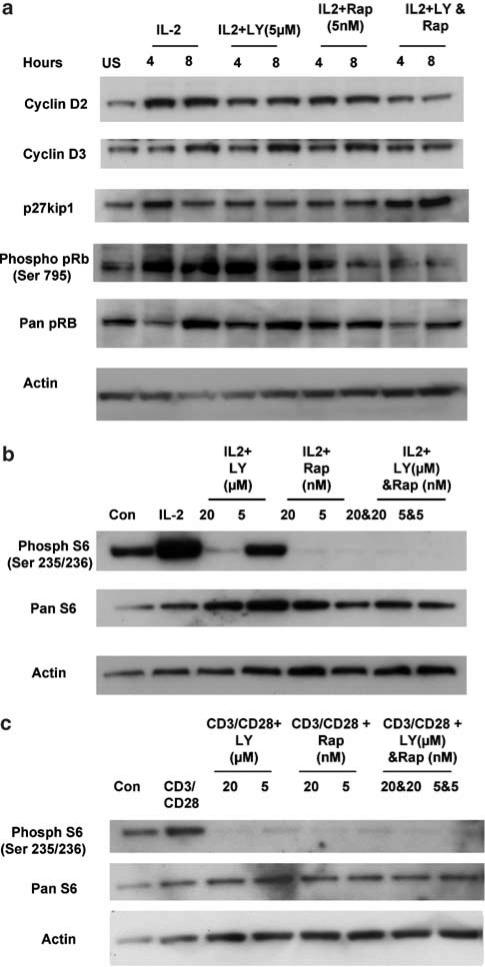

Combined LY294002 and rapamycin treatment alters cell cycle proteins through parallel pathways

Changes in the levels of cell cycle proteins were investigated using specific antibodies. Kit225 cells were quiesced. They were pretreated with LY294002 and rapamycin for 30 min as before and then treated with IL-2 for the times indicated. Total cell lysates were generated and analyzed for a range of cell cyclin proteins. Figure 5 shows that both cyclin D2 and D3 expression is inhibited by the combination of LY294002 and rapamycin. While 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin when used alone reduced the levels of cyclin D2, they did not affect cyclin D3. The levels of p27kip1 showed no consistent change across the experiment, probably because longer treatment with IL-2 is required to alter p27kip1. An increase in phospho pRb is observed in cells treated with IL-2 and is lost in cells treated with the combination of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin. Total pRb levels also change during T-cell proliferation, as it is a cell cycle-regulated gene. The results for the actin blot suggest that changes observed in the protein extracts from cells treated with LY294002 and rapamycin could not be due to protein loading as the actin level is comparable to that seen in the control sample. These data indicate that the inhibition of proliferation is likely to be due to a loss of cdk activity, due in part to reduced D-type cyclin induction.

Figure 5.

Combinations of LY294002 and Rapamycin co-operate to inhibit T-cell cycle proteins. (a) In experiments parallel to Figure 4, Kit225 total lysate protein samples were taken at defined times and the levels of cell cycle proteins were determined following SDS–PAGE and Western blotting. An antibody to the actin protein was used as a loading control. (b) Kit225 cells, washed out for 4 days, were pretreated with LY294002 and rapamycin alone and in combination for 30 min at the doses indicated, and then stimulated with IL-2 for 30 min. Cytosolic extracts were generated and the phosphorylation status of S6 was monitored following SDS–PAGE and Western blotting. (c) T-cell blasts were generated as described for Figure 1. They were pretreated with LY294002 and rapamycin alone, and in combination for 30 min at the doses indicated, and then stimulated with anti-CD3 (OKT3, 2.5 ng ml−1, CRUK) and CD28 (5 μg ml−1, BD Biosciences) for 30 min. Protein extracts were generated, and the phosphorylation status of S6 was monitored following SDS–PAGE and Western blotting.

We analyzed the effects of combined LY294002 and rapamycin treatment on a pathway that lies downstream of the molecules affected by these inhibitors. Using SDS–PAGE, the phosphorylation status of S6 was monitored. S6 is the substrate of S6 kinase. S6 kinase activity is regulated by the PI3K pathway through PDK-1 and is also regulated by mTOR, placing it downstream of both inhibitors. Figure 5b shows that Kit225 cells have some constitutive S6 phosphorylation. This is increased by treatment with IL-2. LY294002 (20 μM) is sufficient to completely ablate this phosphorylation, while 5 μM LY294002 causes a reduction of S6 phosphorylation to control levels. Both concentrations of rapamycin, 20 and 5 nM, completely inhibited S6 phosphorylation and so S6 phosphorylation was also completely ablated in cells treated with LY294002 and rapamycin. These results parallel the phosphorylation of S6kinase (data not shown). This suggests that LY294002 must be having an effect on pathways other than S6, as it cannot cause any further inhibition of the pathway and thus that LY294002 and rapamycin are likely to be altering parallel pathways. We also analyzed the effects of combined LY294002 and rapamycin on the phosphorylation of S6 in previously activated primary T-cell blasts. Figure 5c shows that T-cell blasts also have some constitutive S6 phosphorylation. This is increased by the addition of antibodies to CD3 and CD28. When used separately, LY294002 and rapamycin caused a dramatic, and indistinguishable, inhibition of S6 phosphorylation.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin are effective at inhibiting CD3-induced proliferation

Having observed co-operation between LY294002 and rapamycin in Kit225 cells and that these inhibitions could also decrease S6 phosphorylation in T-cell blasts, we investigated the effects of the two inhibitors on proliferation in resting PBLs. Human lymphocytes were isolated from whole blood using a Ficoll gradient, labelled with CFSE and stimulated with antibody to the CD3 chain of the T-cell receptor. Cell division was measured at various times, up to 6 days. The cell division was determined within the live gate only, excluding an effect on cell survival. Figure 6a shows a typical flow cytometry profile from this experiment and illustrates the effects of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin alone and when combined. The numbers on the histograms denote the proposed number of population divisions the cells have undergone. The combined treatment of both LY294002 and rapamycin more strongly inhibited resting PBL division when compared to treatment of cells with inhibitors independently.

Figure 6.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to inhibit cell division of primary human T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3. Primary human T-cells were stained with CFSE, pretreated with LY294002 or rapamycin, or a combination of the two inhibitors at the doses indicated for 30 min and stimulated with anti CD3 antibody (Okt3, 2.5 ng ml−1). The cells were analysed by flow cytometry after 6 days. (a) Representative flow cytometry histograms for the 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin treatments, measured after 6 days, are illustrated. The numbers on the histograms denote the proposed number of population divisions the cells have undergone (b). The curves generated by the CFSE profile were analyzed using the proliferation platform of the FlowJo software as for the Kit225 experiments of Figure 4. (b) illustrates the graph generated using Number of Divisions as a measure of proliferation. The graph was generated from four different experiments. The numbers under the axis represent inhibitor concentrations. CsA at a standard dose of 0.5 μg ml−1 is used as a comparison. The error bars represent the standard error. Student's t-tests were used to ascertain the statistical significance of the results. (b) indicates a significance level of P<0.05 (*).

Data from four separate experiments were analyzed using the FlowJo proliferation platform and the number of divisions undergone in each population of cells was calculated. These were combined to generate the mean and standard error of the mean as shown in Figure 6b. Paired Student T-tests were performed to test if the differences between the combined treatments of LY294002 and rapamycin were significant when compared to the effects of the inhibitors used alone. The asterisk in Figure 6b indicates a significance level of P<0.05. Both inhibitors alone at doses of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin reduced CD3-induced cell division, although the changes were not significant (P=0.16, 0.13, respectively), but the combined treatment of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin caused a significant reduction of CD3-induced cell division (P<0.05, column 5 compared to columns 3 or 4). The graph also shows that the effects of the combined treatment of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin causes significantly more inhibition than 5 nM rapamycin used alone (P<0.05). This combination is comparable with treatment of the CD3-stimulated cells with Cyclosporin A (CsA) at the standard dose of 0.5 μg ml−1.

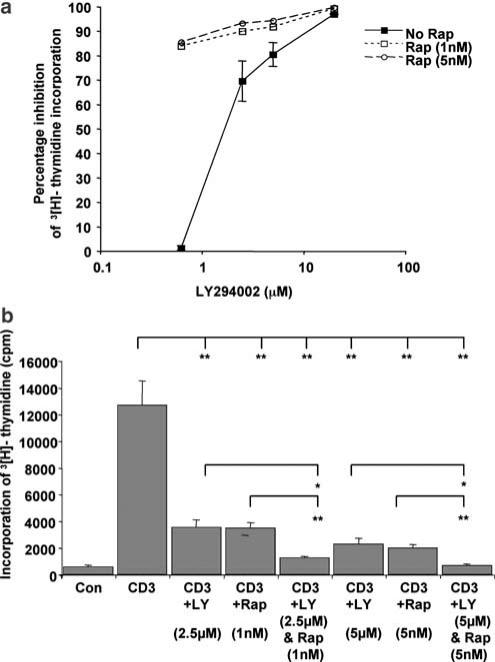

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin inhibit tritiated thymidine incorporation

Tritiated thymidine is another method of measuring cell proliferation. It is also an indirect measure of cell survival, as dead cells cannot incorporate thymidine. We used four different combinations of LY294002 and two concentrations of rapamycin to further investigate the effects of combining these inhibitors. Resting PBLs were isolated from blood and pretreated with various doses and combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin for 30 min prior to stimulation with an antibody to the CD3 chain of the T-cell receptor. Cells were left for 4 days and then 0.5 μCi of tritiated thymidine was added to each well of a 96-well plate. The plate was harvested after 16 h and incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation counting of tritium. Figure 7a illustrates the percentage inhibition following pretreatment with a range of doses of LY294002 in the absence and presence of rapamycin, from one experiment performed in triplicate. The same pattern of inhibition was seen in two further experiments. Both LY294002 and rapamycin, independently and combined, cause a reduction of incorporation of tritiated thymidine. Figure 7b illustrates the results as a histogram and allows the visualization of CD3 alone and CD3 in the presence of rapamycin. Student's t-tests were performed to determine if the effects of the combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin were significantly different from the inhibitors used alone. The combination of 2.5 μM LY294002 and 1 nM rapamycin causes significantly more inhibition of CD3-induced thymidine incorporation than either inhibitor alone. Furthermore, the combination of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin also caused significantly more inhibition than the two inhibitors alone. Together, these data suggest that combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin are more powerful for inhibiting CD3-induced lymphocyte proliferation.

Figure 7.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to inhibit thymidine incorporation into primary human T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3. Resting PBLs isolated from whole blood were pretreated with various doses and combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin for 30 min prior to stimulation with an antibody to the CD3 chain of the T-cell receptor for 4 days (OKT3, 2.5 ng ml−1, CRUK). Cells were pulsed with 0.5 μCi of tritiated thymidine for the last 16 h of the experiment and the incorporation measured by liquid scintillation counting of tritium. (a) Illustrates the range of doses of LY294002 in the absence and presence of rapamycin. Both LY294002 and rapamycin, independently and combined, cause a reduction of incorporation of tritiated thymidine. (b) Illustrates the results as a histogram, indicating the percentage inhibition of 3[H]thymidine incorporation, compared to anti-CD3-stimulated cells alone. A Student's t-test determined any significant levels of inhibition.

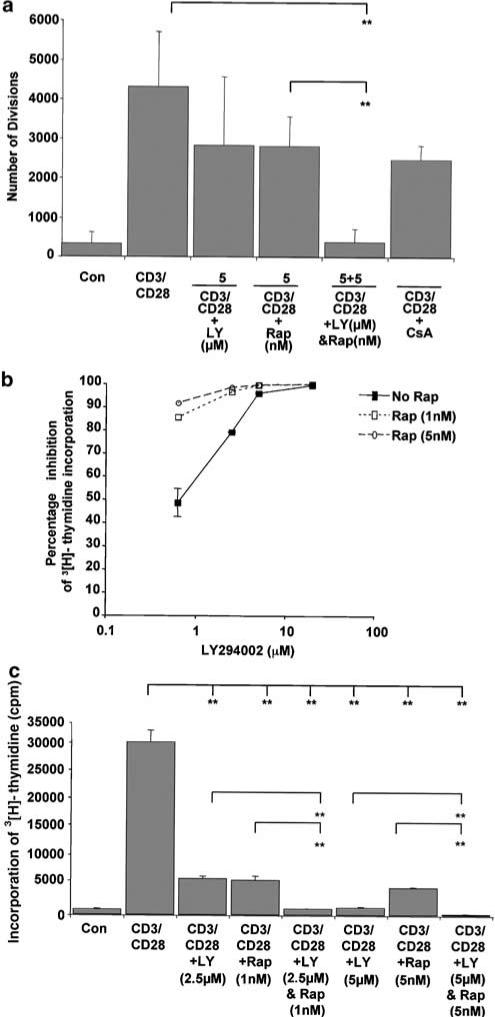

LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to inhibit proliferation induced by antibodies to CD3 and CD28

CD28 is the primary T-cell co-stimulatory receptor. Binding of its specific ligands enhances T-cell proliferation and IL-2 synthesis. We examined the effects of combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin on resting PBLs stimulated with both an antibody to CD28 and antibody to CD3 using both CFSE analysis of cell division and tritiated thymidine incorporation. It has been reported that CD28 antibody clones vary in their ability to stimulated T-cells to produce IL-2 and increase intracellular calcium concentration. The CD28 antibody clone (CD28.2, BD Biosciences) used in these experiments is a strong co-stimulator for human T-lymphocytes. Similar to experiments described for CD3, resting PBLs were freshly isolated from human blood. For CFSE experiments, they were labelled for 5 min. The cells were pretreated with the inhibitors for 30 min. They were then stimulated with an antibody to CD3 and an antibody to CD28.

The CFSE analysis was performed after 6 days. Figure 8a shows the results from the CFSE analysis and incorporates data from four independent experiments. The addition of co-stimulation results in an increased number of cell divisions than observed in cells stimulated with anti-CD3 alone (Figure 6b). This is consistent with previous studies. LY294002 (5 μM) and 5 nM rapamycin have less effect alone than those observed in cells treated with anti-CD3 only (Figure 6b). However, the inhibitors combine to cause a significant increase in the inhibition of cell division (P<0.01). The effect of the combined treatment of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin is also significantly different from inhibition observed with rapamycin 5 nM used alone (P<0.01).

Figure 8.

Combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to inhibit proliferation in primary human T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. We examined the effects of combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin on resting PBLs stimulated with both an antibody to CD28 (5 μg ml−1, BD Biosciences) and antibody to CD3 (OKT3, 2.5 ng ml−1, CRUK), using both CFSE analysis of cell division and tritiated thymidine incorporation similar to experiments described for CD3 in Figures 6 and 7. (a) Shows the results from CFSE analysis and incorporates data from four independent experiments. (b) Illustrates the range of doses of LY294002 in the absence and presence of rapamycin and indicates the percentage inhibition of 3[H]thymidine incorporation, compared to anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated cells alone. Both LY294002 and rapamycin, independently and combined, cause a reduction of incorporation of tritiated thymidine. (c) Illustrates the results as a histogram. A Student's t-test determined any significant levels of inhibition.

The effect of LY294002 and rapamycin was also investigated on tritiated thymidine incorporation stimulated by antibodies to CD3 and CD28. Figure 8b and c illustrate the data from one experiment performed in triplicate and the same pattern of inhibition was seen in two other experiments. The combination of CD3 and CD28 caused a higher incorporation of tritiated thymidine than CD3 alone (compare Figure 8c with Figure 7b). Both LY294002 and rapamycin alone caused a significant inhibition of tritiated thymidine incorporation. Interestingly, cells treated with antibodies to CD3 and CD28 were more sensitive to LY294002 (IC50=0.625 μM) than cells treated with anti-CD3 alone (IC50=2 μM). Similar to data observed in cells treated with anti-CD3 alone, the combination of 2.5 μM LY294002 and 1 nM rapamycin inhibited anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 treatment significantly more than either inhibitor alone (P<0.01). This is also the case for the combination of 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin. The doses used in Kit225 cells and resting PBLs treated with anti-CD3, 5 μM LY294002 and 5 nM rapamycin, also inhibited proliferation more significantly when combined than when used alone. Thus, combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin can combine to more effectively inhibit proliferation of lymphocytes stimulated through CD3 and CD28.

Discussion

This study was performed to investigate the pathway leading from PI3K to the D-type cyclins. We have shown that PI3K regulates cyclin D2 and D3 transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally, perhaps by regulating mRNA stability. Furthermore, our results indicate that combinations of LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3K, and rapamycin can give a stronger inhibition of cell proliferation than when the inhibitors are used alone. The data show that there is a difference in the susceptibility of Kit225 and primary T-cells, be they T-lymphoblasts or freshly isolated resting PBL, to LY294002. LY294002 (5 μM) had very little effect on the proliferation of Kit225 cells, while 1 μM LY294002 inhibits the proliferation of T-lymphoblasts (Figure 2) and 2.5 μM LY294002 inhibits the proliferation of resting PBL stimulated with anti-CD3 (Figure 7) or anti-CD3 with anti-CD28 (Figure 8). This is also the case for rapamycin, where resting PBLs are more sensitive than Kit225 cells. Our data also show that combinations of lower doses of both inhibitors are more effective in primary T-cells than Kit225 cells. These differences are likely to be due to the difference between primary cells and immortalized cell lines.

There are parallels in the effects of LY294002 and rapamycin on the p27kip1 pathway and the cyclin D pathway. LY294002 promotes p27kip1 transcription (Burgering & Kops, 2002) and rapamycin promotes the stability of the p27 protein (Nourse et al., 1994). Thus, the PI3K pathway also regulates p27kip1 both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally. The role for another target for rapamycin within the cell cycle is supported by the data showing that p27kip1-deficient mice are still susceptible to rapamycin (Luo et al., 1996). It is likely that the inhibition of D-type cyclin expression by rapamycin can, in part, explain that data. Hashemolhosseini et al. (1998) showed that, in fibroblasts, both cyclin D1 mRNA and cyclin D1 protein levels are affected by rapamycin. T-cells do not express cyclin D1, but some conservation of mechanisms is likely.

Our data suggest that LY294002 and rapamycin are targeting both overlapping and parallel pathways. We have shown that S6 phosphorylation is altered by both LY294002 and rapamycin in Kit225 cells and T-cell blasts. In both cell types, LY294002 can co-operate with rapamycin at doses where rapamycin completely ablates S6 phosphorylation, suggesting that LY294002 is affecting other pathways. Rapamycin inhibits a subset of PI3K pathways, but TOR may be integrating other pathways too. There is evidence that TOR responds to nutrient levels in yeast (Barbet et al., 1996). In mammalian cells, proliferation is stimulated by a combination of nutrients and growth factors. Accumulating evidence indicates that TOR might mediate signalling in response to both stimuli. In the presence of raptor, the newly identified TOR interacting protein, mTOR kinase activity is increased when stimulated with leucine (Kim et al., 2002). TOR is also thought to respond to a mitochondrial signal, but this signal may be as a result of amino acids synthesized in the mitochondria (Crespo et al., 2002). Thus, there are many distinct possibilities for the parallel pathways LY294002 and rapamycin are inhibiting.

Our results show that combinations of LY294002 and rapamycin co-operate to give effective inhibition of proliferation in response to antibodies to both CD3 and CD28. CD28, through PI3K, has been shown to directly alter cyclin D3 and p27kip1 (Boonen et al., 1999; Appleman et al., 2000; 2002) similar to our data with IL-2. Hsueh et al. (1997) have reported that CD28 activates rapamycin-insensitive signalling pathways and Boonen et al. (1999) have shown that rapamycin did not affect cyclin D3 levels. CD28 has also been shown to alter glucose metabolism in lymphocytes (Frauwirth et al., 2002). Thus, the effects of LY294002 and rapamycin on CD28 signalling may be due to different signalling targets to that of IL-2. Tritiated thymidine incorporation into T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 were more sensitive to LY294002 (IC50=0.625 μM) than tritiated thymidine incorporation into T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3 alone (IC50=2 μM). Results from similar systems have reported an IC50 for LY294002 inhibition of CD3-induced mouse T-cell proliferation as approximately 0.5 μM (Haeryfar & Hoskin, 2001) and for IL-7-induced human T-cell proliferation as less than 5 μM (Lali et al., 2004). These different IC50 values reflect alternative cell types and stimuli, but may also reflect varied dependencies on PI3K for cell survival and proliferation.

This work suggests that inhibition of T-cell proliferation using a combination of a PI3K inhibitor and rapamycin could be beneficial as an alternative immunosuppressive regime. The therapeutic use of PI3K inhibitors is controversial. There are several different but closely related PI3Ks, which are known to have distinct biological roles. However, the first isoform-selective PI3K inhibitor, for p110δ, has been described by the ICOS corporation (Sadhu et al., 2003a; 2003b). Our data, which show that inhibition of PI3K and TOR can co-operate, suggest that these isoform-selective agents may be useful for combination therapies. Such combination therapies may allow lower doses to be administered and as such may avoid the serious side effects of immunosuppressive agents, such as nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and hyperlipidaemia. However, it must be stressed that, because of the potential toxicity of broad-spectrum PI3-kinase inhibitors such as LY294002, the use of PI3-kinase inhibitors in the clinic will not be feasible until these highly isoform-specific compounds are developed for clinical use. Recent data we have generated suggest that PI3K inhibitors may also be useful as combination therapies for lymphoma. Thus, our observations should inform the use of inhibitors of PI3K, possibly in conjunction with rapamycin, in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

E.M.B. is supported by a studentship from the Welsh Office for Research and Development. P.C.W. and P.B. are supported by the Leukaemia Research Fund (U.K.). A.M.S. and M.C. are supported by Tenovus, the Cancer Charity. We thank Professor Martin Rowe for advice and critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr Reginald James Matthews' group, especially Dr Jean Sathish for technical advice.

Abbreviations

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PBLs

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- PHA

phytohaemagglutinin

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase

- pRb

retinoblastoma protein

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

References

- ABRAHAM R.T., WIEDERRECHT G.J. Immunopharmacology of rapamycin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPLEMAN L.J., BEREZOVSKAYA A., GRASS I., BOUSSIOTIS V.A. CD28 costimulation mediates T cell expansion via IL-2-independent and IL-2-dependent regulation of cell cycle progression. J. Immunol. 2000;164:144–151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPLEMAN L.J., VAN PUIJENBROEK A.A., SHU K.M., NADLER L.M., BOUSSIOTIS V.A. CD28 costimulation mediates down-regulation of p27kip1 and cell cycle progression by activation of the PI3K/PKB signaling pathway in primary human T cells. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2729–2736. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARBET N.C., SCHNEIDER U., HELLIWELL S.B., STANSFIELD I., TUITE M.F., HALL M.N. TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:25–42. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEADLING C., GUSCHIN D., WITTHUHN B.A., ZIEMIECKI A., IHLE J.N., KERR I.M., CANTRELL D.A. Activation of JAK kinases and STAT proteins by interleukin-2 and interferon alpha, but not the T cell antigen receptor, in human T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5605–5615. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOONEN G.J., VAN DIJK A.M., VERDONCK L.F., VAN LIER R.A., RIJKSEN G., MEDEMA R.H. CD28 induces cell cycle progression by IL-2-independent down-regulation of p27kip1 expression in human peripheral T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:789–798. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<789::AID-IMMU789>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN P., BABBAGE J.W., BURGERING B.M., GRONER B., REIF K., CANTRELL D.A. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase couples the interleukin-2 receptor to the cell cycle regulator E2F. Immunity. 1997;7:679–689. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN P., BABBAGE J.W., THOMAS G., CANTRELL D. p70(s6k) integrates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and rapamycin-regulated signals for E2F regulation in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4729–4738. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURGERING B.M., KOPS G.J. Cell cycle and death control: long live Forkheads. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:352–360. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRESPO J.L., POWERS T., FOWLER B., HALL M.N. The TOR-controlled transcription activators GLN3, RTG1, and RTG3 are regulated in response to intracellular levels of glutamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:6784–6789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102687599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRAUWIRTH K.A., RILEY J.L., HARRIS M.H., PARRY R.V., RATHMELL J.C., PLAS D.R., ELSTROM R.L., JUNE C.H., THOMPSON C.B. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16:769–777. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAERYFAR S.M., HOSKIN D.W. Selective pharmacological inhibitors reveal differences between Thy-1- and T cell receptor-mediated signal transduction in mouse T lymphocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHEMOLHOSSEINI S., NAGAMINE Y., MORLEY S.J., DESRIVIERES S., MERCEP L., FERRARI S. Rapamycin inhibition of the G1 to S transition is mediated by effects on cyclin D1 mRNA and protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14424–14429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORI T., UCHIYAMA T., TSUDO M., UMADOME H., OHNO H., FUKUHARA S., KITA K., UCHINO H. Establishment of an interleukin 2-dependent human T cell line from a patient with T cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia who is not infected with human T cell leukemia/lymphoma virus. Blood. 1987;70:1069–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSUEH Y.P., LIANG H.E., NG S.Y., LAI M.Z. CD28-costimulation activates cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein in T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1997;158:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHAN B.D. Individuality: the barrier to optimal immunosuppression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nri1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM D.H., SARBASSOV D.D., ALI S.M., KING J.E., LATEK R.R., ERDJUMENT-BROMAGE H., TEMPST P., SABATINI D.M. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOPS G.J., MEDEMA R.H., GLASSFORD J., ESSERS M.A., DIJKERS P.F., COFFER P.J., LAM E.W., BURGERING B.M. Control of cell cycle exit and entry by protein kinase B-regulated forkhead transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2025–2036. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2025-2036.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURTS C., KOSAKA H., CARBONE F.R., MILLER J.F., HEATH W.R. Class I-restricted cross-presentation of exogenous self-antigens leads to deletion of autoreactive CD8(+) T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:239–245. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LALI F.V., CRAWLEY J., MCCULLOCH D.A., FOXWELL B.M. A late, prolonged activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway is required for T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 2004;172:3527–3534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONARD W.J. Cytokines and immunodeficiency diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001;1:200–208. doi: 10.1038/35105066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUO Y., MARX S.O., KIYOKAWA H., KOFF A., MASSAGUE J., MARKS A.R. Rapamycin resistance tied to defective regulation of p27Kip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6744–6751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDEMA R.H., KOPS G.J., BOS J.L., BURGERING B.M. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEHL A.M., FLOETTMANN J.E., JONES M., BRENNAN P., ROWE M. Characterization of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 regulation by Epstein–Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein-1 identifies pathways that cooperate with nuclear factor kappa B to activate transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:984–992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON B.H., WILLERFORD D.M. Biology of the interleukin-2 receptor. Adv. Immunol. 1998;70:1–81. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOURSE J., FIRPO E., FLANAGAN W.M., COATS S., POLYAK K., LEE M.H., MASSAGUE J., CRABTREE G.R., ROBERTS J.M. Interleukin-2-mediated elimination of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor prevented by rapamycin. Nature. 1994;372:570–573. doi: 10.1038/372570a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OEHEN S., BRDUSCHA-RIEM K. Naive cytotoxic T lymphocytes spontaneously acquire effector function in lymphocytopenic recipients: a pitfall for T cell memory studies. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:608–614. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<608::AID-IMMU608>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKKENHAUG K., BILANCIO A., FARJOT G., PRIDDLE H., SANCHO S., PESKETT E., PEARCE W., MEEK S.E., SALPEKAR A., WATERFIELD M.D., SMITH A.J., VANHAESEBROECK B. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110delta PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002;297:1031–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SADHU C., DICK K., TINO W.T., STAUNTON D.E. Selective role of PI3K delta in neutrophil inflammatory responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003a;308:764–769. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SADHU C., MASINOVSKY B., DICK K., SOWELL C.G., STAUNTON D.E. Essential role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta in neutrophil directional movement. J. Immunol. 2003b;170:2647–2654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHERR C.J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAHL M., DIJKERS P.F., KOPS G.J., LENS S.M., COFFER P.J., BURGERING B.M., MEDEMA R.H. The forkhead transcription factor FoxO regulates transcription of p27Kip1 and Bim in response to IL-2. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5024–5031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VLAHOS C.J., MATTER W.F., HUI K.Y., BROWN R.F. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARD S.G., CANTRELL D.A. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases in T lymphocyte activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2001;13:332–338. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YUSUF I., FRUMAN D.A. Regulation of quiescence in lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:380–386. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]